Final Report — Towards optimal allied health and nursing service provision in VACS funded...

Transcript of Final Report — Towards optimal allied health and nursing service provision in VACS funded...

Final Report — Towards optimal allied health and nursing

service provision in VACS funded specialist clinics

MARCH , 2010

FOR THE

DEPARTMENT OF

HEALTH , VICTORIA

H u m a n C a p i t a l A l l i a n c e

2

Towards Optimal Allied Health and Nursing Service Provision in VACS Funded Specialist Clinics

This report was prepared by:

Human Capital Alliance (International) Pty Ltd PO Box 2014, Normanhurst NSW 2076 Australia

Suite 2, 2a Pioneer Ave, Thornleigh NSW 2120 Ph: +61 2 9484 9745 Fax: +61 2 9484 9746

The Final Report was written by: Rosalie Boyce, Sharon Kendall, Mark Mattiussi, Meredith McIntyre, Lee Ridoutt, Joanne Bagnulo and Adrian Schoo.

Disclaimer

This report has been prepared by Human Capital Alliance (International) for the Department of Health, Victoria. Human Capital Alliance (International) prepares its reports with diligence and care and has made every effort to ensure that evidence on which this report has relied was obtained from proper sources and was accurately and

faithfully assembled. It cannot, however, be held responsible for errors and omissions or for its inappropriate use.

H u m a n C a p i t a l A l l i a n c e

3

Contents

1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................. 6

OVERVIEW ............................................................................................................... 6

METHODOLOGY ...................................................................................................... 7

DISCHARGE PERFORMANCE .................................................................................... 8

BETTER USE OF ALLIED HEALTH SKILLS ................................................................ 8

OTHER ALLIED HEALTH CLINICS ........................................................................... 9

GROUP CLINICS ...................................................................................................... 10

CONCLUSION .......................................................................................................... 11

LIST OF RECOMMENDATIONS ................................................................................ 12

2. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... 16

PURPOSE OF THE REVIEW ...................................................................................... 16

BACKGROUND ........................................................................................................ 16

PAST REVIEWS AND REPORTS ................................................................................ 20

METHODOLOGY ..................................................................................................... 21

ABOUT THIS REPORT ............................................................................................. 22

3. IMPROVING THE RATE OF DISCHARGE ............................................................................. 23

BACKGROUND ....................................................................................................... 23

POSSIBLE WAYS FORWARD ..................................................................................... 27

FUNDING SYSTEM CHANGES ................................................................................. 27

NON FUNDING SYSTEM APPROACHES ................................................................... 29

SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDED APPROACH............................................................ 32

4. BETTER USE OF ALLIED HEALTH / NURSING SKILLS .............................................................. 34

BACKGROUND ....................................................................................................... 34

CURRENT SITUATION ............................................................................................ 35

BROAD OPPORTUNITIES ........................................................................................ 37

PRIORITY OPPORTUNITIES ................................................................................... 40

POSSIBLE WAYS FORWARD ..................................................................................... 43

FUNDING SYSTEM CHANGES ................................................................................. 44

NON FUNDING SYSTEM APPROACHES ................................................................... 46

5. RATIONALISATION OF ‘OTHER’ CODED CLINICS ................................................................. 50

BACKGROUND SITUATION ..................................................................................... 50

PATTERNS OF ‘OTHER’ SERVICE DELIVERY .......................................................... 53

POSSIBLE WAYS FORWARD ..................................................................................... 57

6. GROUP CLINICS ......................................................................................................... 61

BACKGROUND ........................................................................................................ 61

CURRENT SITUATION ............................................................................................ 62

A WAY FORWARD .................................................................................................... 64

ANOTHER WAY FORWARD ..................................................................................... 64

H u m a n C a p i t a l A l l i a n c e

4

NON FUNDING APPROACHES ................................................................................ 68

7. DISCUSSION ............................................................................................................. 70

BACKGROUND ....................................................................................................... 70

OVERVIEW OF RECOMMENDATIONS ...................................................................... 71

ALTERNATIVE PATHWAYS ..................................................................................... 73

COST IMPLICATIONS OF RECOMMENDATIONS...................................................... 75

8. REFERENCES ............................................................................................................. 77

APPENDIX A: METHODOLOGY DETAILS .............................................................................. 79

THE QUESTIONNAIRE SURVEY .............................................................................. 79

SITE VISIT INTERVIEW CONSULTATIONS .............................................................. 80

FOCUS GROUP DISCUSSIONS ................................................................................... 81

LITERATURE REVIEW ............................................................................................ 82

APPENDIX B: GROWTH IN MEDICAL SPECIALIST TRAINEES ....................................................... 83

APPENDIX C: ALLIED HEALTH OUTPATIENT OOS TARGETS ..................................................... 84

APPENDIX D: SURVEY RESPONDENTS ................................................................................. 85

APPENDIX E: SURVEY INSTRUMENT .................................................................................. 86

APPENDIX F: STAKEHOLDER CONSULTATIONS .................................................................... 103

APPENDIX G: INTERVIEW SCHEDULE FOR KEY HEALTH SERVICE CONTACTS .............................. 105

APPENDIX H: INTERVIEW SCHEDULE FOR KEY INTEREST GROUPS ........................................... 107

H u m a n C a p i t a l A l l i a n c e

5

Table of Abbreviations BSBC Better Skills, Best Care

CAHE Centre for Allied Health Evidence COAG Council of Australian Government DHS Department of Human Services, Victoria

DRG Diagnostic related group EAL Early Assessment and Linkage EPC Enhanced Primary Care FEES fibre optic endoscopic evaluation of the swallow

FTE Fulltime equivalent HACC Home and Community Care MDC Multidisciplinary care MDS Minimum Dataset

OAHKS Osteoarthritis Hip and Knee Service OIIS Outpatient Innovation and Improvement Strategy OOS occasions of service OWL Orthopaedic Waiting List SVR Surgical Voice Restoration VACS Victorian Ambulatory Classification and Funding System VINAH Victorian Integrated Non-Admitted Health

H u m a n C a p i t a l A l l i a n c e

6

1. Executive Summary

Overview

Since its inception in 1997 the Victorian Ambulatory Classification and Funding System (VACS) has been continually evolving. Recent reviews have focused attention on areas of

possible change. This Review builds on previous internal and external change efforts and was initiated under the Victorian Government’s Outpatient Innovation and Improvement Strategy

(OIIS) in 2006-07. The aim is to improve access to public hospital outpatient services and to address some of the issues identified in the Auditor General’s report (June 2006) Access to specialist medical outpatient care. The purpose of this review was to:

� determine and map the current allied health and advanced nursing practice service provision in acute hospital settings;

� identify opportunities and barriers for further advancement of scope of practice and to provide advice on the required changes to the VACS funding model to support the implementation of extended and advanced allied health roles;

� explore the potential for provision of current specialist clinic allied health services

in alternate settings;

� improve current discharge performance; and

� analyse the possibility of delivering more outpatient services through group rather than individual patient encounters without any loss of efficiency.

The review focuses on allied health and nursing elements of total outpatient services. In

terms of the VACS funding arrangements, this means the scope of the review is limited to funding codes 601 to 611 which include 601, Audiology; 602, Nutrition; 603, Optometry; 604, Occupational Therapy; 605, Physiotherapy; 606, Podiatry; 607, Speech

Pathology; 608, Social Work; 609, Other Allied Health Services; 610, Cardiac Rehabilitation; and 611, Hydrotherapy. The proportion of total outpatient service activity in the VACS allied health coded areas

can vary from as low as 17% to as high as 51% in different health services and overall is just under 30%.

Between the financial years 2001/02 and 2007/08, overall growth in occasion of service activity in the allied health VACS code categories increased by only 9%, but certain VACS code activity grew by almost half while others shrank by almost as much. In absolute terms the largest growth areas were ‘Other Allied Health Services’ (609) and ‘Optometry’

(603), although the latter was off a low base. The largest areas of reduction were ‘Audiology’ (601), ‘Social Work’ (608) and ‘Speech Pathology’ (607). The ‘Other Allied Health Services’ category has grown 13% and over 20,000 occasions of service since 2001 to now account for almost one third of all VACS allied health occasions of service. As a general rule, an ‘other’ category within any taxonomy should not exceed 5% of the total count. Many of the 609 category services are new nursing models of

practice, including advanced practice. Target allied health activity levels are set each year for each health service and funded accordingly. Many of the health services report that there are significant discrepancies

H u m a n C a p i t a l A l l i a n c e

7

between the activity targets budgeted under the VACS and the actual demand for these services. In the 2007/08 financial year more than half of the health services exceeded their targets for allied health coded VACS activity. Overall in that year though, the VACS

funded services activity in the 600 series codes for all health services was 588,3821 outpatients which fell short of the total target set by 6,543, or just over 1% of the

funded target2. In the 2008 / 2009 financial year the total actual activity in the 600 series VACS code area was 556,970 outpatients, again marginally short (approximately 6%) of the set total target activity of 594,248. Total allied health activity has varied considerably from year to year over the last eight years.

Methodology

The methodology employed for this Review to meet the objectives of this report included four main forms of data collection as follows:

� a survey questionnaire completed by all VACS funded services;

� interviews and focus group meetings with representatives from health services, outpatient services and clinic managers;

� focus group meetings with nurse and allied health leaders from outpatient

settings; and

� an extensive literature review of speciality allied health and nursing services currently in use or being trialled in Australia or overseas (i.e. the United

Kingdom, Canada).

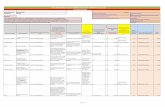

Table 1.1: Review objectives and required research method

Review objectives Survey Interviews Focus

groups

Literature

review Mapping of current allied health and

advanced practice nurse service provision across the selected VACS

funded health services

Understand the potential for provision of

current specialist clinic allied health services in alternate settings

Identification of opportunities for allied health enhanced practitioners and

advanced practice nurses to provide

specialist clinic services

Analysis of ‘group’ encounters for allied health services

Analysis of new and ongoing treatment

sessions and discharge destinations

Identification of potential for

reclassification of 609 VACS clinics

Source: Project Plan

Ongoing open discussion with the Department and the project steering group led to some adjustment and refinement of the method during the project.

1 Victorian-Public hospitals and mental health services: policy and funding guidelines 2007-08 2 Figures based on a count of all patients including the majority categorised as ‘Public’ and a much smaller but still significant number categorised as ‘DVA’ or Department of Veterans Affairs.

H u m a n C a p i t a l A l l i a n c e

8

Discharge performance

The ratio of ‘new’ patients to ‘review’ patients varies considerably between VACS codes

and also between different health services. The proportion of new patients at the average clinic could range from as low as 14% (hydrotherapy) to as high as 70% (audiology). At least 20%, or one fifth of current allied health patient consultations, are estimated by outpatient service providers to be able to be diverted to alternative care settings. There

is much interest in realising this movement of patients and thus significantly increasing the capacity of Victorian specialist outpatient clinics. Funding system changes and educational or administrative changes could facilitate this shift through a ‘package’ of measures to influence change. This package of funding, administrative and educational

measures should drive clinics into the desired direction, help them self-assess when they are not performing as they could, and help them to develop and implement clinic specific initiatives to optimise performance. Recommended interventions include:

� introduction of a differential VACS payment for ‘new’ and ‘review’ patient occasions of service which favours ‘new’ patient services;

� development of a generic discharge protocol that prohibits ongoing patient review in the absence of a re-referral process generated by a community-based service provider;

� introduction of a ‘discharge activity’ payment that supports a more active

referral process from the outpatient environment to community care;

� development of a basic benchmarking system within VACS health services

allowing comparison of like clinics within health service categories, with at least two discharge performance indicators; and

� creation of a separate fund within the Department to support an internal (to VACS funded health services) peer consultancy program for at least 3-5 years.

These measures have been designed to improve the rate of discharge from allied health outpatient clinics without encouraging inappropriate discharge of patients who should be in specialist outpatient services or for whom there are no realistic referral options available in the short term. The objective is to facilitate appropriate discharge of patients who no longer need hospital-based care.

Better use of allied health skills

The current deployment of allied health professionals and nurses into advanced practice activity is characterised by:

� significant variation between VACS code areas of activity and within codes between health services in the types and levels of advanced practice undertaken

by allied health professionals and nurses;

� with the exception of some centrally organised projects (for instance the ‘Better Skills Best Care’ Program), an ad hoc (rather than strategic) approach to

expansion of allied health or nurse activity that has prevailed; and

� a clinician led expansion of allied health and nursing roles at a local level based on the skill, knowledge, experience and expertise of the individual clinicians in

response to patient demand and local contextual pressures.

Much currently labelled ‘extended’ scope of practice is on closer analysis ‘advanced’ practice and, as such, within accepted scope of practice. Depending on the complexity of

the caseload practice may require operating in novel settings and with greater independence, although in consultation with other professionals. The introduction of

H u m a n C a p i t a l A l l i a n c e

9

‘advanced’ practice requires: (1) proving the competence exists to undertake the advanced practice work (this may or may not require credentialed evidence); and (2) obtaining the support of medical specialists if advanced practice involves performing

work which was previously the exclusive domain of medical specialists. Many examples of advanced practice already in VACS funded health services provide proof that this can be achieved.

In terms of the health professional resources devoted to delivering advanced activities as a proportion of total specialist allied health outpatient clinic services there is variation between the VACS code activities. In some areas of VACS activity the contribution of

advanced practice to total activity is minor (for example hydrotherapy, cardiac rehabilitation, audiology) while in some other areas of activity ‘advanced’ practice accounts for just under half of total activity (podiatry, speech pathology, physiotherapy).

The Review recommends a range of measures aimed at increasing the level and pace of the introduction of advanced nursing and allied health practice innovation into Victorian outpatient clinics. The measures would help support innovation, and assist individual

clinicians and clinical teams and their management infrastructure to become informed about innovations. Specific recommendations include the following interventions:

� new innovative clinics that are clinically validated by the Clinical Panel and

satisfy other key criteria (a well argued business case, well developed clinical pathways, strong local support from medical practice and health service executive, and proven competence of nurse and allied health practitioners)

should be supported by temporary supplements to the relevant health service’s VACS targets;

� weighted VACS allied health clinic payments should be progressed;

� introduction of multidisciplinary care (MDC) payment codes would support developments in advanced practice in areas where it has the best chance of flourishing and providing benefit;

� development of generic protocols and clinical pathway guidelines for those

advanced practice developments at one health service that have proven valuable and worthy of broader implementation; and

� a program of meetings of health service based teams of nurse and allied health

clinic practitioners, along with key and relevant medical practitioners and outpatient service managers, where advanced practice innovations can continually be showcased in an environment of collegiate discourse.

Other allied health clinics

The ‘Other Allied Health’ coded activity (609) area last year accounted for just over one

third of total VACS allied health activity (601 to 611 including 609). Analysis of available clinic survey and Clinics Schedule data allows several major clinic sub-groupings to be discerned including:

� specialist nurse – led clinics that tend to run parallel with or otherwise in support of specialist medical or surgical clinics. Some of these clinics are specifically to prepare patients for an operation or support patients post-operatively;

� allied health clinics of disciplines not covered under other 600 codes. The main discipline / service area categories are psychologists, orthoptists, orthotists / prosthetists;

� procedural clinics where a particular set service is provided and the clinics essentially help prepare patients for the procedure which can be a single

H u m a n C a p i t a l A l l i a n c e

10

occasion of service (e.g. a scope procedure) or a longer term course of treatment (e.g. to treat cancer); and

� multidisciplinary clinics (involving only allied health and/or nursing professionals

but no medical specialists). The case for separating these categories from the broader ‘Other’ code can be waged on

the following possible grounds:

� more information about actual outpatient services activity is able to be elicited

for planning and policy development purposes;

� inappropriate outpatient activity can be more easily identified; and

� opportunities for advanced practice within a multidisciplinary care setting (for

instance within a medical or surgical VACS code area) are lost. On the basis of available evidence of the prevalence of current clinic types reported within 609 coded activity a reasonable case could be mounted to introduce the following

new VACS clinic classifications:

� Stomal Therapy;

� Diabetes Education;

� Psychological Services;

� Orthotics and Prosthetics;

� Post-operative wound management;

� Urology services (post-operative); and

� Nurse-led Oncology care. The creation of new codes in the VACS classification has no implications to cost. Health service activity targets will not change; rather existing activity will simply be re-labelled. This might change if recommendations to introduce cost weightings for allied health services were adopted. It is difficult to know how the identified new clinic categories might be weighted and if they will fall on average above or below the current unweighted

rate of payment ($61 per occasion of service).

Group clinics

Several of the health services (20%) claim not to conduct group outpatient activities at all, while many of the others restrict group activities to a narrow band of VACS funded areas. None of the surveyed health services for instance offered group activities for 601 (Audiology), 606 (Podiatry) and 607 (Speech Pathology). Within the VACS codes, group

processes were relatively prominent only for nutrition, physiotherapy and ‘Other Allied Health’ categories.

Group clinics are not well perceived because stakeholders argue group sessions are not cost effective as funding does not take into account the actual time and resources required for the proper organisation, set up and conduct of group sessions. Moreover, many group clinics are claimed to have a ‘group’ and ‘individual’ component (generally an

assessment or monitoring of a care plan) and so services find it easier and more financial to count group participants as individual occasions of service.

Despite the general negative attitude, most outpatient clinicians acknowledge there are some circumstances in which the evidence supports the efficacy of group processes. It seems there are genuine clinical advantages for group sessions where they include elements of peer support and shared learning. Some examples of these are cardiac rehabilitation groups which provide peer support and child health groups where new

H u m a n C a p i t a l A l l i a n c e

11

parents learn from, and support, each other. The Review recommends developing criteria for decision making to aid service providers in identifying circumstances that are appropriate for group processes and for individual occasions of service encounters and

promoting these criteria to health services. Shifting behaviour towards more appropriate use of group clinical processes requires an overhaul to the VACS payment methodology. The current VACS group clinic payment that

is the same as an individual occasion of service infers that group processes have a single purpose only, to increase efficiency of resource (labour) use. This approach is placing group clinics on a pathway to eventual extinction.

To support the use of group clinics where clinically indicated, group activity payment needs to be determined such that the payment is higher than an individual occasion of service, but not so high as to encourage inappropriate use of group processes. The most attractive approach is to set payment levels for group activity within each VACS allied health code developed through cost weight methodology. This would be in keeping with recommendations made for other areas of proposed change.

An alternative would be to define and develop a new set of codes for group activity within VACS. A taxonomy based on purpose appears the most useful way to classify group activity. It is most consistent with an understanding of the worth of group processes.

Different group purposes could include:

� information provision / preparation for treatment;

� education / shared learning;

� peer support;

� assessment; and

� combined or similar courses of treatment / therapy / exercise.

There are several ways purposes can be combined to create different group activity types, each of which would have a different cost implication. A possible classification and payment approach based on a limited number of most feasible group activity types and input cost estimates developed by an expert panel is discussed in Chapter 6.

Whatever changes are implemented, the challenge will be to shift health services from claiming the individual Allied Health VACS codes to the new group codes and specific clinical group activity target setting. Auditing may be required to facilitate this shift in

behaviour.

Conclusion

The introduction of the VACS classification and funding arrangements has achieved some of its architects’ expectations, especially improved fairness in funding allocation, a better description of services provided (which supports better planning and service management) and some efficiencies. However VACS needs to continue to evolve to

provide the right types of incentives for service improvement and efficient delivery. In the area of the Allied Health VACS Codes growth in nursing led clinics under the ‘Other

Allied Health’ code, the flat payment for all occasions of service, and issues around group activities and discharge of patients from services have resulted in diminished value of service data and growing inefficiencies in service planning and decision making.

H u m a n C a p i t a l A l l i a n c e

12

This Review has provided a series of suggestions for improvement that are detailed above under each of the main areas of proposed change viz. clinic discharge; growth in the area of new and advanced nursing and allied health practice including support for

multidisciplinary teams; reduction in the number and proportion of clinics covered under the 609 ‘Other Allied Health’ code; and group clinic services. In total there are 18 separate recommendations which are listed in the following section.

This rather daunting list can be grouped into several broad categories of proposed action as follows:

� introduction of new VACS classification codes by splitting existing 600 series code categories into subunits as a matrix and / or by creating specifically targeted new code categories;

� changing basic elements of the VACS funding arrangement to encourage certain types of health service behaviour;

� development of protocols and guidelines to better inform clinic practitioners

and managers of desired, evidence based practice approaches; and

� building of infrastructure to support the desire for, and the capacity for, dissemination of innovative models of outpatient service delivery.

The cost of implementing the recommendations is qualitatively assessed but this will depend on the pathways adopted, especially whether the preferred pathway to establish cost weighted payments for Allied Health VACS codes is adopted.

List of recommendations

Recommendation 1:

� To require all VACS funded health services to collect and report data on ‘new’ and ‘review’ patients at each clinic from financial year 2010/11.

� To complete data definitions for the outpatient component of VINAH in respect

to patient status (‘new’ or ‘review’, probably by using episode start and other date comparisons).

� To introduce a differential VACS payment in financial year 2011 /12 for ‘new’

and ‘review’ patient occasions of service which favours ‘new’ patient services, where ‘new’ is defined as the occasion when an assessment and treatment plan is developed.

Recommendation 2:

� To develop guidelines that limit the number of allied health occasions of

service for any one patient for all patients referred to outpatient specialist services from a general practitioner. The rules pertaining in the primary care setting under Medicare funding arrangements could easily be copied. These guidelines would place limits on the maximum number of occasions of service but not preclude earlier discharge. After reaching the limit a further referral must be sought from the general practitioner.

� To develop guidelines for all other types of patient journey (for instance those

from inpatient care) that limit the number of initial patient occasions of service to an agreed and appropriate number based on available evidence. Continued treatment beyond this limit would be contingent on gaining a general practitioner (or specialist) referral.

H u m a n C a p i t a l A l l i a n c e

13

� To develop and formally establish service entry protocols will not allow acceptance of referrals (and VACS payments not be honoured) unless the approved patient journey pathway has been followed.

Recommendation 3:

� Following the more universal implementation of data collection requirements, to introduce a benchmarking ‘service’ that provided at least six monthly data at the individual clinic level on the ‘new’ to ‘review’ patient ratio and the average number of occasions of service of patients visiting each clinic on a

nominated ‘census’ week. The scope of this service will depend on the extent to which data collection is limited (for instance it may be constrained to review of Allied Health VACS Codes activity).

� To establish agreed sub-classes within the VACS classification system, to allow meaningful comparison within and between health services. For instance, a distinction may need to be drawn between ‘specialist’ allied health clinics and the more routine ‘treatment’ type clinics.

� To publish benchmark results such that clinics can identify their performance within their health service and within same class clinic categories across all health services (for instance all hydrotherapy treatment clinics).

� To annually audit a selection of clinics that have below average indicators, initially through processes internal to health services but later through external processes if performance issues persist for more than 12 months.

Recommendation 4:

� To establish a budget to be administered by a relevant branch within the

Department of Health that would support the operation of a ‘peer consultant’ workforce, that properly supported identifying the right consultants and administering arrangements for their consultancy activity with relevant clinics, and reimbursed health service employers sufficiently to ‘back fill’

temporary vacancies when peer consultants are engaged in consultancy activities.

Recommendation 5:

� To implement within the next two years advanced practice service models that optimally utilise higher order skills of nurses and allied health professionals.

Recommendation 6:

� To allocate separate occasions of service targets for advanced practice clinics

newly approved by the Clinical Panel which the Panel itself could determine (or approve on application). The target approval would apply for two financial years only, after which it would need to be supported through an allocation

from the total target amount.

Recommendation 7:

� To renew efforts to find appropriate cost weightings for allied health clinics.

Most likely this research work will need to be done collaboratively at a national level and therefore borrow concepts from existing funding models (for instance in South Australia) and be undertaken through Council of

Australian Government (COAG) arrangements.

H u m a n C a p i t a l A l l i a n c e

14

Recommendation 8:

� To examine the examination a multidisciplinary clinic code and payment

where allied health contributes to a medically driven clinic.

� To investigate a new VACS code that covers multidisciplinary care provided only by allied health practitioners and nurses in the absence of any medical practitioner input.

Recommendation 9:

� To develop centrally, through an appropriate forum of relevant Departmental officers and innovative health service providers, a strategic investment plan in worthy (promising) advanced practice models in a similar way to the current

BSBC model. In priority order these can be supported from a separate fund to become operational.

Recommendation 10:

� To increase the number and quality of current collaborative activities in a way that enhances regular interaction between health service and clinic level decision makers and practitioners.

Recommendation 11:

� To develop a state outpatient services training plan that (1) identifies skill

needs for support of implementation of desired advanced practice innovations (2) prioritises investment in those skills where a deficit is perceived to be a barrier to implementation.

� To ascertain the need for skills to be certified.

� To negotiate with appropriate professional associations and / or training and education institutions to undertake skills assessment, recognition and

certification where it is considered necessary or prudent.

Recommendation 12:

� To introduce a number of new VACS codes within the 600 ‘Allied Health’ series. This would include at least codes for:

− Stomal Therapy

− Diabetes Education − Psychological Services − Orthotics and Prosthetics − Post-operative wound management

− Urology services (post-operative) − Nurse-led Oncology care

Recommendation 13:

� To develop criteria for assessing the suitability of clinics on the basis of stated

aims and models of care for an outpatient services setting.

� To conduct an audit of all 609 VACS coded clinics and assess them against the prescribed criteria.

H u m a n C a p i t a l A l l i a n c e

15

� To seek an explanation from health services where clinics do not appear to satisfy the criteria for suitability.

� To install the prescribed criteria to ensure future applications for new clinics

are subjected to a structured assessment of validity to belong within an outpatients services environment.

Recommendation 14:

� To use group coding (and funding) only in cases where evidence-based practice suggests group interaction to be appropriate and to confer clinical

advantages.

Recommendation 15 (preferred option):

� To introduce a funding arrangement based on cost weightings for group activity in each of the allied health VACS code areas if appropriate. Cost weightings to be developed using a similar methodology to that required for

individual occasions of service.

Recommendation 16 (contingency option):

� To increase the payment for group clinics according to payment on the primary purpose/s of the clinic. A limited number of payment options to be developed (say no more than 10) based on the most common types of group clinic purpose or purpose combinations.

� To develop an agreement on the payment levels associated with each group activity type from a reasonable assessment of the inputs required. An expert panel of experienced outpatient clinic allied health and nursing clinicians to be

convened to create this consensus.

Recommendation 17:

� To introduce any new group activity payment first as a shadow funding

arrangement while changes to the VACS funding model are settled.

Recommendation 18:

� To develop criteria for decision making to aid service providers in identifying circumstances which are appropriate for group processes and those which are better suited to individual OOS encounters.

� To provide examples and descriptions of successful group clinics and group activity best practice.

� To initiate a broad promotion and education campaign in regard to group

clinic processes targeting health service outpatient administrators and clinic leaders.

H u m a n C a p i t a l A l l i a n c e

16

2. Introduction Purpose of the Review

This review was initiated under the Victorian Government’s OIIS, which commenced in 2006-07 with the aim of improving access to public hospital outpatient services and

addressing some of the issues identified in the Auditor General’s report (June 2006) Access to specialist medical outpatient care. The purpose of this review was to determine and map the current allied health and advanced nursing practice service provision in acute hospital settings, to identify opportunities and barriers for further advancement of

this scope of practice and to provide advice on the required changes to the VACS funding model to support the implementation of extended and advanced allied health roles, group encounters and multidisciplinary teams.

This Review has provided the following reports prior to this Final Report:

� A description of current and allied health service provision in specialist clinics at selected VACS funded Victorian public hospitals — this report attempted primarily to gain a better understanding of the current activity and the role of allied health and nurse labour in VACS funded hospital outpatient

services with a particular focus on the 600 series VACS funded clinics.

� Identification of opportunities for enhanced practitioners in specialty clinics and the requisite qualifications and scope of practice — this report

focused on the Review objective requiring the identification of opportunities for allied health enhanced practitioners and advanced practice nurses to provide specialist clinic services. The report is mostly based on a review of the literature although qualitative data from consultations in VACS funded health services and

broader stakeholder groups were also drawn upon where appropriate.

The review focuses on allied health and nursing elements of total outpatient services. In

terms of the VACS funding arrangements, this means the scope of the review is limited to funding codes 601 to 611 which include 601, Audiology; 602, Nutrition; 603, Optometry; 604, Occupational Therapy; 605, Physiotherapy; 606, Podiatry; 607, Speech Pathology; 608, Social Work; 609, Other; 610, Cardiac Rehabilitation; and 611,

Hydrotherapy. During the course of the Review a strong interest in the 609 VACS category “Other allied health services” emerged, partly because it was thought that this code might include clinics that should be in alternate care delivery settings and partly because it covered too much of total activity for an ‘other’ category.

Background

Funding arrangements

VACS was introduced in 1997 with the aim of providing a case mix model for outpatient services. The VACS arrangement is used to fund the outpatient services in 19 Victorian public health services.

H u m a n C a p i t a l A l l i a n c e

17

Typically outpatient services include (DHS, 2008):

“ … a number of visits within a short time frame and may overlap with other public

and private inpatient and community-based services. These services essentially

provide specialised consultations, pre and post-hospital care, and other general

medical and allied health services. Hospital outpatient services are important for

teaching and training, and the development of innovative service models. They play

a special role in particular areas and for particular population groups, for example

persons from non-English speaking backgrounds.”

VACS hospitals report patient attendances as either bundled encounters or occasions of service. Encounters refer to visits within one of the 35 VACS weighted medical and surgical clinics and include allowances for the costs of ancillary services such as pathology, radiology and pharmacy which occur in the 30 days either side of the clinic visit. Occasions of service refer to visits within one of the eleven VACS allied health unweighted categories (the 600 series) and the VACS Code 550 for Emergency Medicine. The current VACS Categories and Weights 2009-10 can be found in Appendix 4 of the

Victorian Health Services Policy and Funding Guidelines 2009-10, Part 2 Policy and

Funding Details – Technical Guidelines. For the 2009-10 fiscal year the payments for VACS are $173 per weighted encounter and $61 per allied health occasion of service. The Department of Health routinely calculates the VACS weights for the 35 different bundled

encounter categories provided by the participating VACS Hospitals (that have been able to provide robust and timely data) and this is then used to review the base weighted encounter payment and the relative clinic code weightings.

Activity targets are provided each year for health services with VACS Weighted Encounters and Allied Health Occasions of Service being provided as separate targets for each service. Budgets can then be modelled on the revenue associated with these targets

in conjunction with other revenue target and funding sources for the health services. Targets for all clinics are not set on costing data alone but rather the activity history of a health service with adjustments to take into account service demand and capability.

Outpatient activity Many of the health services report that there are significant discrepancies between the outpatient activity targets budgeted for under the VACS and the actual demand for these

services. In the 2007 / 08 financial year slightly more than half the health services exceeded their targets (see Appendix C) for allied health coded VACS activity. Overall in that year though, the VACS funded services activity in the 600 series codes for all health services was 588,382 outpatients which fell short of the total target set by 6,543, or just

over 1% of the funded target. In the 2008 / 2009 financial year the total actual activity in the 600 series VACS code area was 556,970 outpatients, again marginally short (approximately 6%) of the set total target activity of 594,248. Total activity has varied

considerably from year to year over the last eight years as shown in Figure 2.1 on page 15 making any effort to assess observations on the balance between actual and target patient totals difficult. Indeed in five of the last eight years for which data is available actual patient numbers have exceeded the target for which funding was available

although in three of the last four years actual patient numbers have been below targets. When considering the implementation of new models of allied health and nursing care in ambulatory settings and how incentives in the funding system can assist in uptake of the

new models the nuances of the current model must be considered. If health services are exceeding their activity (revenue) targets and no new activity or revenue is being proposed then there is no incentive in the current system to support the implementation

of new clinics (under new models of care) unless they substitute for presently funded activity. Under this arrangement there will also be the requirement to reduce the FTE

H u m a n C a p i t a l A l l i a n c e

18

establishment of one type of clinician when substituting with another to support the new model of care.

Figure 2.1: Total occasions of service (OOS) activity in the VACS 600 series

(Allied Health) codes Financial Years 2001/02 to 2008/09 with percentage

change from previous year

500000

510000

520000

530000

540000

550000

560000

570000

580000

590000

600000

610000

2001/02 2002/03 2003/04 2004/05 2005/06 2006/07 2007/08 2008/09

-8

-6

-4

-2

0

2

4

6

8

10

OOS % change

Source: Victorian Public hospitals and mental health services: policy and funding

guidelines 2001/02 -2008/09

To some extent substitution of activity between VACS codes appears to have already been the norm. Between the financial years 2001/02 and 2007/08, overall growth in OOS activity in the allied health VACS code categories was only 9.3%, yet certain VACS code activity grew by almost half while others shrank by almost as much. In absolute terms

the biggest growth areas were ‘Other Allied Health Services’ (609) and ‘Optometry’ (603) although the latter was off a low base, and the biggest areas of reduction were ‘Audiology’ (601), ‘Social Work’ (608) and ‘Speech Pathology’ (607). This is

demonstrated in Table 2.1. Apart from the apparent dynamism in service activity between VACS categories, another feature of Table 2.1 is the growth in the ‘Other Allied Health Services’ category. It has

grown 13% and over 20,000 OOS, to now account for just over one third of all VACS allied health occasions of service. Total outpatient encounters vary considerably between health services ranging from

under 40,000 per year to larger services with over 130,000 encounters per year. All health services have medical (101-115) and surgical (201-209) outpatient clinics but some health services have only limited (or no) clinics in the VACS codes of 300 (Dental,

Orthopaedics, Orthopaedic applications, Psychiatry and Behavioural Disorders), 400 (Family Planning, Obstetrics / Gynaecology) or 500 (Paediatric) codes. All health services have outpatient clinic activity in the VACS codes 601 to 611, but not for all codes.

H u m a n C a p i t a l A l l i a n c e

19

Table 2.1: Trends in OOS activity by VACS allied health codes, 2001/02 to 2007/08

Code Category 2001/2002 2007/2008 % Change

between

time

periods

601 Audiology 16,184 10,034 -38%

602 Nutrition 35,270 44,600 +26%

603 Optometry 895 7,830 +774%

604 Occupational Therapy 62,363 70,051 +12%

605 Physiotherapy 142,197 150,052 +6%

606 Podiatry 12,110 11,985 -1%

607 Speech Pathology 19,589 14,530 -26%

608 Social Work 88,350 65,721 -26%

609 Other Allied Health Services 152,715 204,286 +34%

610 Cardiac Rehabilitation 4,415 3,262 -27%

611 Hydrotherapy 4,096 6,031 +47%

TOTAL 538,184 588,382 +9.3%

Source: AIMS data (2009)

In Figure 2.2 below the proportion of total outpatient encounters (again gathered through the VACS AIMS data collection process) able to be attributed to codes 601 to 611 (allied health) for all VACS funded health services is shown.

Figure 2.2: VACS funded outpatient service codes 601 to 611 as a proportion of

total outpatient services in selected health services, 2008 and 2009 financial

years

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

%

o

f

t

o

t

a

l

s

e

r

v

i

c

e

s

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S

Health services

2007-08 2008-09

Source: AIMS data (2009)

As shown in Figure 2.2, the allied health (and other) proportion of total outpatient services can vary from as low as 17% to as high as 51% in different services. There does

not seem to be an obvious pattern in this variation, other than that, the smaller and less

H u m a n C a p i t a l A l l i a n c e

20

specialised hospitals have a lower proportion. This could be a reflection of available allied health staffing resources.

New clinics In the event that a new clinic is proposed by participating health services or the expansion of current clinics is required then there is an established pathway to be followed. This pathway involves the use of the Clinical Panel which is a panel of eminent clinicians from a range of specialties, representatives from the field and Departmental representatives whose role it is to preside over decisions regarding the classification and

use of the VACS eligible clinics3. The role only concerns the clinical verification of clinics as appropriate for inclusion in the VACS model, (e.g. whether a clinic is appropriate for

the category for which it has been submitted or should be in another category). Where there has been a request for additional funding for a new clinic, the Panel's decision will inform its consideration.

The Clinical Panel meets and advises if there is sufficient clinical evidence to support the new clinic, if an expanded clinic meets the relevant guidelines and also whether the clinic is best provided as ambulatory care or alternatively in the community.

Past reviews and reports

Significant intellectual capital has been invested through work that has already been undertaken in the area of VACS funding and allied health clinics: this Review seeks to

build on selected themes from this past work. The past efforts which this Review has most considered are:

� Auditor General Victoria (2006) Access to specialist medical outpatient care,

Auditor Generals Office, Victoria

� Healthcare Management Advisors (2006) VACS clinical verification and activity audit. Department of Human Services, Victoria

� Victorian Government Department of Human Services (2006) Care in your community: A Planning Framework for Integrated Ambulatory Health Care, Melbourne, Victoria

� SANO Consulting (2008) Development and Pilot of a Generic Outpatient Care

Pathway Template Department of Human Services, Victoria

� Aspex Consulting (2008) Review of the Victorian Ambulatory Classification &

Funding System. Final Report and Implementation Plan. Department of Human Services, Victoria

� Victorian Government Department of Human Services (2008) Review of the

Victorian Ambulatory Classification & Funding System and the DHS response to

Aspex Consulting Review, Melbourne, Victoria

� Victorian Government Department of Human Services (2008) Victorian

Ambulatory and Classification System (VACS) and Funding Model A profile for

1997/98 – 2008/09, Funding Health & Information Policy Branch, (Funding Policy) of the Metropolitan Health and Aged Care Services, Melbourne Victoria

� Victorian Government Department of Human Services (2009) Victorian health

services policy and funding guidelines 2009–10 Part 1: Highlights, Melbourne, Victoria

� Victorian Government Department of Human Services (2009) Victorian health

services policy and funding guidelines 2009–10 Part 2: Policy and funding details Policy and program initiatives, Melbourne, Victoria

3 The Panel has no responsibility for the approval of VACS targets or funding requests related to those clinics, but does inform the process.

H u m a n C a p i t a l A l l i a n c e

21

� Victorian Government Department of Human Services (2009) Victorian Public Hospital Specialist Clinics: Strategic Framework, Melbourne Victoria

There are many common themes within these reports pertinent to improving on the current allied health VACS classification and funding arrangements. These include:

� the absence of high quality, detailed patient level data;

� that there is no agreed international, national or local classification system for outpatients that is comparable to the current inpatient classification system;

� reinforcing our finding of the increasing use of the VACS Clinic Code 609 “Other Allied Health”, which has grown to be a very heterogeneous group of clinics;

� that any proposed change to the classification system for the VACS Clinic Code

609 will need to be cognisant of AHCA/National Health Care Agreement reporting requirements;

� specialist nurse clinics should be allocated to a new VACS category that

distinguishes them (professionally) from Allied Health Professionals;

� there are currently accepted practices where endorsed nurse practitioners and midwives are eligible to claim medical VACS for their clinic consultations as they

are viewed as substitution;

� the potential for telephone screening including Early Assessment and Linkage (EAL) clinics should be trialled though it was considered prudent that the

payment for these should be captured as a part of the bundled VACS encounter;

� that the application of weights should be considered for those non weighted OOS (Allied Health VACS codes 601 to 611 including group clinics), Multidisciplinary

Care (MDC) Services and Care Planning Conferencing (CPC);

� any sudden change to Allied Health Cost Weights may have significant funding implications within and between health services and it would be prudent to implement a shadow funding arrangement in the first instance; and

� that funding for group clinics consider the different types of group clinics in light of the number of providers per group; a group with individual treatment plans for participants; and classes where all participants receive identical attention

from one provider.

Methodology

The methodology employed for this Review, in so far as the main tasks and activities are

concerned, included four main forms of data collection viz.:

� a survey questionnaire completed by all VACS funded services;

� interviews and focus group discussions with health service, outpatient service and clinic managers;

� focus group discussions with nurse and allied health leaders from outpatient

settings; and

� an extensive literature review of speciality allied health and nursing services currently in use or being trialled in Australia or overseas (i.e. the UK, Canada,

etc.).

The methodology was fixed after initial consultations with the Department set the parameters for the Review and was laid out in the Project Plan. Ongoing open discussion

with the Department and the project steering group led to appropriate adjustment and refinement of the method. Descriptions of each of the above processes of data collection are provided in Appendix A. Table 2.2 below summarises the relationship between

methods of data collection and analysis and the objectives of the Review.

H u m a n C a p i t a l A l l i a n c e

22

Table 2.2: Relationship between methods of inquiry and review objectives

Review objectives Survey Interviews Focus

groups

Literature

review Mapping of current allied health and

advanced practice nurse service

provision across the selected VACS

funded health services

Understand the potential for provision of

current specialist clinic allied health services in alternate settings

Identification of opportunities for allied

health enhanced practitioners and advanced practice nurses to provide

specialist clinic services

Analysis of ‘group’ encounters for allied

health services

Analysis of new and ongoing treatment

sessions and discharge destinations

Identification of potential for

reclassification of 609 VACS clinics

Source: Project Plan

About this report

This report provides a consolidated view of the current allied health service provision in

VACS funded specialist clinics and identifies opportunities for more efficient and effective utilisation of outpatient clinics. In terms of the VACS funding arrangements, this means the scope of the Review is limited to funding codes 601 to 611 which include 601, Audiology; 602, Nutrition; 603, Optometry; 604, Occupational Therapy; 605,

Physiotherapy; 606, Podiatry; 607, Speech Pathology; 608, Social Work; 609, Other; 610, Cardiac Rehabilitation; and 611, Hydrotherapy. In Chapter 3 the report addresses ways to improve efficiency within the current clinics through improved discharge. Chapter 4 builds on improving capacity of the current workforce with extension of the current roles of allied health and nursing practitioners into advanced and extended roles. Chapter 5 looks at the provision of outpatient services

provided under the 609 or ‘other’ funding category. Chapter 6 expands on Group sessions and describes possible methodologies for enhancing the uptake of groups including VACS funding system changes and the report concludes with the discussions in Chapter 7 that attempt to overview the broad intent of recommendations throughout the

report.

H u m a n C a p i t a l A l l i a n c e

23

3. Improving the rate of discharge Background

In an earlier report for this project (HCA, 2009a) based on survey data it was noted that the ratio of ‘new’ patients to ‘review’ patients varied considerably between VACS code areas of activity and also within codes between different health services. The proportion

of new patients at the average clinic could range from as low as 14% (hydrotherapy) to as high as 70% (audiology). In Table 3.1 below, the ‘average’ proportion of new patients at each clinic is provided, calculated by adding all viable responses and dividing by the total number of valid respondents. In some cases extreme outlier values were excluded

from the analysis. A median statistic was examined, but after outlier values were excluded there was little difference between mean and median statistics. The range of

values for new patient proportions is also provided in Table 3.14.

Table 3.1: Average the number of reviews per patient within the 601-611 VACS

codes

VACS

Code VACS descriptor Average % New

Patients per clinic

Range of new patient

clinic ratios

601 Audiology 70.1%* 1:2 to 10:1

602 Nutrition 47.1% 1:5 to 4.5:1

603 Optometry 33%% 1:5 to 1.1

604 Occupational Therapy 36.5% 1:8 to 1:0 (only new)

605 Physiotherapy 30.5% 1:18 to 12:1

606 Podiatry 11.1% 1:12 to 1:4

607 Speech Pathology 37.1%* 1:8 to 4:1

608 Social Work 52.7% 1:8 to 6:1

610 Cardiac Rehabilitation 22.7% 1:10 to 2:1

611 Hydrotherapy 13.6% 1:10 to 1:4

Source: Survey of health services * One outlier value removed from the analysis since it was distorting the figures

Several stakeholders noted that an average statistic in regard to the proportion of new

patients per clinic was potentially meaningless if allied health clinics were distributed bi-modally. They argued this could be the case with clinics falling into two distinct groups:

A. specialist clinics that largely undertook assessment and referral tasks such as a

health service physiotherapy clinic described as a “… Screening clinic for patients on waiting list for Orthopaedic and Neurosurgical outpatient clinic

consultation” (AIMS Clinics Schedule) these clinics would predominantly only

see new patients; and

B. regular treatment clinics that would be providing ongoing support and would

have a very high proportion of review patients.

4 Note, the statistics for the ‘Other Allied Health’ category 609 have not been included because the variation within this category is too great rendering a mean or median figure somewhat irrelevant.

H u m a n C a p i t a l A l l i a n c e

24

The survey data does not allow realistic examination and validation of this position; however the significant range in new to review patient ratios for some allied health codes noted in Table 3.1 suggests this might be a possibility. Selected VACS code areas of

activity taken from the AIMS data, suggest that the bulk of health services have only one clinic per allied health VACS code.

Clearly though, some health services, mostly the teaching hospitals, have greater

differentiation of clinic type within selected allied health areas, and have some genuinely specialist clinics. Examples, again using descriptions extracted from the AIMS Clinic Schedule, of such clinics are:

Orthopaedic Education Clinic - Limb Review Clinic - Education (OREDCL) This

clinic provides pre-operative education to every elective limb reconstruction patient.

Each session lasts 2 - 3 hours and is conducted by nursing and allied health staff.

The purpose of the service is to improve pre-operative planning, increase patient

knowledge of the procedure and facilitate timely discharge.

Orthopaedic Assessment Clinic (ORTALL) This clinic provides an assessment and

triaging service for new patients referred to the Orthopaedic Department's

outpatient clinics with lower acuity conditions who would otherwise wait an

indefinite amount of time for a clinic appointment. The clinic is held five times per

week and is serviced predominantly by an orthopaedic physiotherapist however

there is some level of orthopaedic registrar involvement.

Clinical Nutrition (456C) For clients with a number of complex metabolic

problems. Each week there is a different focus such as eating disorders, body

composition, osteoporosis and nutritional support. Clients are seen by

endocrinologists, clinical nutrition physician, dietician a nurse and psychologist.

Generally, the pattern in new to review patient ratios reflects the number of times

patients are called back for review or to maintain their treatment process (see Figure 3.1 below). In most cases, review patients need to be discharged before new patients can be accepted.

Figure 3.1: Average the number of reviews per patient within the 601-611 VACS

codes

Source: Survey of health services * One outlier value removed from the analysis since it was distorting the figures

The issue of poor discharge rates has been a concern for many years (for instance see

the Aspex Consulting report, 2005), especially from those clinics that provide more

H u m a n C a p i t a l A l l i a n c e

25

routine treatment to patients with chronic illness or which provide a service to the more general patient population.

There is a strong consensus that a better patient throughput could be achieved. The survey results showed that health services could identify a number of opportunities to shift the patient workload (of existing review patients) to alternative service providers. Respondents estimated that between 3% and 90% of current patient consultations,

depending on the VACS area of activity could in theory be provided by alternative sectors of the health system (especially primary health care providers and community health). Overall, an estimated average of at least 20% or one fifth of current patient

consultations are believed by outpatient service providers to be able to be moved to alternative care settings. The proportion of outpatient consultations that participants thought could be offered in alternative settings by VACS code is shown in Table 3.2 below.

Table 3.2: Potential for moving current patient load to alternative care settings

VACS descriptor Range of clinic opinions on % of current

consultations that could be offered by

alternate providers

Audiology (601) 3 – 30%

Nutrition (602) 5 – 50%

Optometry (603) 0 – 40%

Occupational Therapy (604) 0 – 30%

Physiotherapy (605) 5 – 90%

Podiatry(606) 10 – 30%

Speech Pathology (607) 10 – 80%

Social Work(608) 10 – 20%

Cardiac Rehabilitation (610) 5%

Hydrotherapy(611) 15 – 20%

Source: Survey of health services

If there is so much potential for improvement in patient throughput the obvious question is why is greater referral to alternative settings (sub-acute and community) not

happening? Why is discharge of patients being delayed?

Some health services stakeholders consulted argued that some reluctance to discharge could be attributed to the attitude of certain outpatient service providers. Hesitation on

the part of the hospital-based services to refer to community service settings could be due to concern that some patients would experience an inferior service. This is reflected in the observations of one health service interview subject, who noted:

“There is an insufficient critical mass of appropriate expertise available in

community settings particularly for patients requiring specialised management for

acute conditions.”

Of course, there are times when this reason for non referral is appropriate; there are clearly a range of services delivered through outpatients clinics that are sufficiently specialised that they cannot feasibly be delivered in more generalist community services.

Such services include those that target complex or rare conditions requiring high levels of practitioner expertise, specialised equipment and / or immediate access to diagnostic support facilities. For allied health clinics, close access to specialist medical practitioner consultation can also be a factor.

H u m a n C a p i t a l A l l i a n c e

26

Some of the examples provided by health services in the survey responses that would satisfy these conditions were:

� most patients require review and maintenance of their prosthetic or orthotic device for a long period of time. Once the device needs to be replaced or their condition changes a new prosthesis or orthosis may need to be provided.

Therefore the majority of these patients will require long term service provision;

� if the patient is not stable from a wound management perspective and requires multidisciplinary specialist management. Patient may be discharged after a

single visit. Wounds with a longer healing time will be assessed at six weeks and if not healed then ten weeks;

� UV light therapy equipments costs for purchasing UV light machine are prohibitive for the community. Discharged upon completion of treatment; and

� because of chronic complications a prostatectomy for benign hypertrophy is only done when the patient’s urine stream is at a certain decreased level. A single visit may be all that is necessary, but many visits may be required if the

appropriate conditions for the procedure are not satisfied. Separating out legitimate reasons for retaining patients in the outpatient clinic

environment from less valid ‘attitude-based’ concerns about the quality of community services is not easy. It is further complicated because at times, the result of staff and other limitations, the quality of community services is compromised. Some evidence of this cited in the survey responses were:

� Long waiting lists at community services because of a paucity of appropriate allied health or nursing resources. These waiting lists could require a discharged

patient to potentially have a significant ‘gap’ in service continuity with likely poor health outcomes. One health service interview subject consulted noted:

“... there is a three month and longer waiting list to access community

services [in my area] due to the insufficient number of specialist services

available, a situation that is further complicated by low staff retention due

to feelings of isolation and lack of support.”

� A corollary of long waiting lists is tight admissions criteria. Several clinic stakeholders consulted complained that attempts to discharge to an alternative service in the community are often blocked by the tight criteria set down by the service provider for admission.

� The cost of alternative services to the patient is also perceived as a main barrier

to discharge from VACS clinics. The outpatient clinic population is typically drawn from the lower socioeconomic levels of the community and these patients need access to bulk billing services. Outpatient clinic stakeholders argue in such cases

discharge needs to be facilitated by the service as patients are unable to navigate the system without help. In some cases, for instance especially in rural regions, discharge to community services will require a significant co-payment on the part of the patient, which is often likely to lead to a cessation of

treatment altogether. As one health service interview subject observed:

“There is a lack of funding for public patients to access private services. For

example EPC [enhanced primary care Medicare Item numbers] funded

under Medicare does not cover acute conditions and five visits for all allied

health per year does not meet the needs of patients with chronic

conditions.”

H u m a n C a p i t a l A l l i a n c e

27

Sometimes it is clear that patients, as consumers of the health care system, prefer to access their services from specialist outpatient clinics, and this has nothing to do with cost but rather a perception of quality. They perceive the human resources, equipment

and facilities at an acute care centre to be superior to those they might obtain closer to where they live.

Possible ways forward

The Victorian Public Hospital Specialists Clinics Strategic Framework (2009) strongly advocates providing health care in the setting that best matches patient needs:

“To ensure people receive care in the most effective setting and ensure timely

access, comprehensive protocols should be in place for triage, assessment and

discharge of patients, and patients should be discharged to community-based

settings when clinically appropriate, or where there is capacity for a primary or

community provider to more appropriately provide care” (p. 9)

While the use of protocols is important, these must be sensitive to the needs of different

patient groups. There are some patients who will need to be retained by the outpatient clinic because it has the most appropriate resources to manage their care. Measures designed to influence or improve the rate of discharge from allied health outpatient

clinics must ensure that they do not encourage inappropriate discharge of these patients or other patients for whom there are no realistic referral options available in the short-term. Rather, the objective should be to facilitate appropriate discharge of patients who no longer need hospital-based care and who are being retained for reasons such as

patient or clinician preference. The options open to influence change fall into two broad categories:

� funding system changes; and

� educational or administrative changes.

Funding system changes

Qualitative data collected through the consultation process for this Review, along with opinion from past reviews (e.g. HMA, 2006), does not suggest the design of the funding

arrangements particularly affects the behaviour of clinics at the operational level. Rather the more common view is that behaviour is generally historically underpinned (that is clinics do what they have always done) and motivated in the best interests of the patient or at least in maintaining some degree of service delivery status quo. This is testimony of

the sort of willingness, at least based on anecdotal and self-reported survey evidence, of outpatient clinics to put the interests of patients above financial considerations. Nevertheless, this report supports the view that while an imperfect relationship exists

between financial signals and service behaviour, some influence does still prevail. All other funding models, including case mix models for inpatient services, have been designed for and are considered to contribute to influencing clinical practice and

administration. Why should funding of outpatient services be different? Accordingly, a number of changes to the VACS funding arrangements are considered. The idea of creating a separate payment schedule for ‘new’ and ‘review’ occasions

of service is not new. To incentivise an increase in the willingness of clinics to take on more new patients (and by implication discharge review patients earlier), the payment for ‘new’ patient occasions of service would naturally be larger than for review patients.

H u m a n C a p i t a l A l l i a n c e

28

A larger payment they hypothesised could be supported on cost and clinical grounds, since it was (and according to our consultations still is) widely considered that new patient consultations take longer and generally require more higher order assessment

and diagnosis competencies.

They also mooted a separate VACS payment for a successful discharge, again higher than would be the case for an ordinary allied health occasion of service. This approach

would be to incentivise the discharge process rather than as above, incentivise the taking on of new patients. A related approach would be to provide a disincentive to keep review patients by progressively discounting the payment made for review patient

occasions of service, essentially making each successive review occasion of service more of a revenue loss. Alternatively an arbitrary cap on the number of funded visits could be applied, and after reaching the cap the VACS payment reduces to zero (or at least the clinic is requested to justify retaining a patient beyond what is considered to be acceptable practice).

An alternative to trying to incentivise earlier discharge, or at least de-incentivise delayed

discharge, would be to provide funding support to the discharge process itself. A separate payment for ‘discharge’ activity might be provided which would cover the cost of a conferencing clinic (possibly in the absence of the patient), the development of a care plan and administration of the referral to an appropriate alternative service. If there were

a moderate incentive to refer patients and this was buttressed by funding support for a considered discharge process or plan, then higher levels of appropriate discharge might be achieved.

A final option would be to bundle up a number of occasions of service for a particular patient and fund a single ‘episode’ of treatment associated with a coherent patient

diagnosis5. In this option, the funding arrangement would provide a ‘lump sum’ payment along the lines of a WEIS payment for a particular DRG related inpatient service. This

approach effectively caps total payment encouraging discharge when costs begin to drag on (with diminishing reimbursement outcomes). However, if the cost weights for an episode are developed reasonably, the impact on behaviour should be more subtle than with the blunter discharge incentives noted above which would still have unweighted

occasion of service payments associated with a real or de facto capping mechanism. The problem though with this approach is that there could be difficulties collecting the degree of linked patient level data to be able develop the ‘price’ estimates and subsequently to

fund the model.

For different reasons, none of the above suggested changes to the current VACS funding arrangements are entirely satisfactory. Indeed, according to the Aspex Consulting report,

all changes aimed at influencing discharge behaviour run the risk of encouraging inappropriate discharge.

The suggestion that shows most promise though is one based on a revised payment structure for ‘new’ and ‘review’ patients. Of course proper costing of the ‘new’ versus ‘review’ patient population occasions of service would need to be undertaken, but it seems counter-intuitive that review occasions of service could be more costly on average

than new patient occasions of service unless the first visit is not when a thorough assessment, triage and treatment plan is undertaken — a situation that may pertain in

some clinics and health services6. While detractors of this suggestion will note the

5 This would require a definition of the episode based on pathways and can’t be substantiated without good patient level data 6 This is most likely to be the case in some medical and surgical clinics where patients are referred, especially from general practitioners, for specialist consultation but without the necessary ‘work up’ of required pathology and medical imaging tests. In such cases the ‘new’ or initial occasion of service may simply be to order requisite tests, and the follow up or second visit is when the true assessment, diagnosis and treatment plan development occurs. This circumstance is less likely to present in allied health clinics.

H u m a n C a p i t a l A l l i a n c e

29

absence of comprehensive quality patient level reporting across the health services, our own survey efforts were able to elicit data on this issue from health services. Of course, as with all survey data, it can be subjective and difficult to validate. There appears to be