Evaluation and Treatment of Chagas Disease in the United States

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of Evaluation and Treatment of Chagas Disease in the United States

CLINICIAN’S CORNERCLINICAL REVIEW

Evaluation and Treatment of Chagas Diseasein the United StatesA Systematic ReviewCaryn Bern, MD, MPHSusan P. Montgomery, DVM, MPHBarbara L. Herwaldt, MD, MPHAnis Rassi Jr, MD, PhDJose Antonio Marin-Neto, MD, PhDRoberto O. Dantas, MDJames H. Maguire, MD, MPHHarry Acquatella, MDCarlos Morillo, MDLouis V. Kirchhoff, MD, MPHRobert H. Gilman, MD, DTM&HPedro A. Reyes, MDRoberto Salvatella, MDAnne C. Moore, MD, PhD

CHAGAS DISEASE IS CAUSED BY

Trypanosoma cruzi, a proto-zoan parasite usually trans-mit ted by infected tr i -

atomine bugs. Transmission also occursthrough transfusion or organ trans-plantation, from mother to infant, andrarely by ingestion of contaminatedfood or drink.1-3 Vector-borne trans-mission occurs exclusively in theAmericas, where an estimated 8 mil-lion to 10 million people have Chagasdisease.4,5 Historically, transmission hasoccurred predominantly in rural areasof Latin America, where poor housingconditions have promoted contact withinfected vectors. Successful programs

See also Patient Page.

CME available online atwww.jama.com

Author Affiliations: Parasitic Diseases Branch, DivisionofParasiticDiseases,NationalCenterforZoonotic,Vector-Borne and Enteric Diseases, Centers for Disease Controland Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia (Drs Bern, Montgom-ery,Herwaldt, andMoore);AnisRassiHospital,Goiania,Brazil (Dr Rassi); Medical School of Ribeirao Preto, Uni-versityofSaoPaulo,RibeiraoPreto,SaoPaolo,Brazil (DrsMarin-Neto and Dantas); University of Maryland, Bal-timore (DrMaguire);UniversidadCentraldeVenezuela,Caracas, Venezuela (Dr Acquatella); McMaster Univer-sity, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada (Dr Morillo); Universityof Iowa, Iowa City (Dr Kirchhoff ); Johns Hopkins Uni-versity, Baltimore, Maryland (Dr Gilman); I. Chavez

National Institute of Cardiology, Mexico City, Mexico(DrReyes);andPanAmericanHealthOrganization,Mon-tevideo, Uruguay (Dr Salvatella).Corresponding Author: Caryn Bern, MD, MPH, Para-sitic Diseases Branch, Division of Parasitic Diseases, Na-tional Center for Zoonotic, Vector-Borne and EntericDiseases, Centers for Disease Control and Preven-tion, 4770 Buford Hwy NE, MS F-22, Atlanta, GA30341 ([email protected]).Clinical Review Section Editor: Michael S. Lauer, MD.We encourage authors to submit papers for consid-eration as a Clinical Review. Please contact MichaelS. Lauer, MD, at [email protected].

Context Because of population migration from endemic areas and newly institutedblood bank screening, US clinicians are likely to see an increasing number of patientswith suspected or confirmed chronic Trypanosoma cruzi infection (Chagas disease).

Objective To examine the evidence base and provide practical recommendations forevaluation, counseling, and etiologic treatment of patients with chronic T cruzi infection.

Evidence Acquisition Literature review conducted based on a systematic MEDLINEsearch for all available years through 2007; review of additional articles, reports, andbook chapters; and input from experts in the field.

Evidence Synthesis The patient newly diagnosed with Chagas disease should un-dergo a medical history, physical examination, and resting 12-lead electrocardiogram(ECG) with a 30-second lead II rhythm strip. If this evaluation is normal, no furthertesting is indicated; history, physical examination, and ECG should be repeated an-nually. If findings suggest Chagas heart disease, a comprehensive cardiac evaluation,including 24-hour ambulatory ECG monitoring, echocardiography, and exercise test-ing, is recommended. If gastrointestinal tract symptoms are present, barium contraststudies should be performed. Antitrypanosomal treatment is recommended for all casesof acute and congenital Chagas disease, reactivated infection, and chronic T cruzi in-fection in individuals 18 years or younger. In adults aged 19 to 50 years without ad-vanced heart disease, etiologic treatment may slow development and progression ofcardiomyopathy and should generally be offered; treatment is considered optional forthose older than 50 years. Individualized treatment decisions for adults should bal-ance the potential benefit, prolonged course, and frequent adverse effects of the drugs.Strong consideration should be given to treatment of previously untreated patientswith human immunodeficiency virus infection or those expecting to undergo organtransplantation.

Conclusions Chagas disease presents an increasing challenge for clinicians in theUnited States. Despite gaps in the evidence base, current knowledge is sufficient tomake practical recommendations to guide appropriate evaluation, management, andetiologic treatment of Chagas disease.JAMA. 2007;298(18):2171-2181 www.jama.com

©2007 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. (Reprinted) JAMA, November 14, 2007—Vol 298, No. 18 2171

Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ on 02/25/2013

to reduce vector- and blood-bornetransmission, as well as migrationwithin and beyond endemic coun-tries, have changed the epidemiologyof the disease.4,6,7

In endemic settings, T cruzi infectionisusuallyacquiredinchildhood.Thevec-torsdefecateduringor immediatelyafterfeeding; the parasite is present in largenumbers inthe fecesof infectedbugsandenters the human body through the bitewound, conjunctiva, or other mucousmembrane.Anestimated100 000infectedpersons live intheUnitedStates;mostac-quired the disease while residing in en-demicareas.8 However,T cruzi–infectedvectors and animals are found in manypartsoftheUnitedStates,9,10andrarecasesofautochthonoustransmissionhavebeendocumented.11,12 Better housing condi-tionsandlessefficientvectorsmayexplainthe low risk of vectorial transmission;transfusion, organ transplantation, andmother-to-infant transmission are morelikelyinfectionroutesintheUnitedStates.

On December 13, 2006, the US Foodand Drug Administration approved aChagas disease screening assay for do-nated blood.13 As of September 6, 2007,193 donations confirmed positive hadbeen reported.14 Blood donor screen-ing is also likely to lead to heightenedawareness and increased requests for di-agnostic testing in the wider commu-nity. Nearly all T cruzi infections in

newly diagnosed patients will be in thechronic phase, and most will be asymp-tomatic. Appropriate management ofpatients with Chagas disease requiresspecialized clinical expertise, labora-tory diagnostic support, and access toantitrypanosomal drugs, all of which arelimited in the United States.

This article aims to provide clini-cians with practical guidance for theevaluation, management, and etio-logic treatment of Chagas disease, witha primary focus on the chronic phase.The detailed management of Chagascardiac15-17 and gastrointestinal tract18

disease is beyond the scope of this ar-ticle; primary care clinicians shouldconsult with experienced subspecial-ists. This article is based on a compre-hensive systematic literature reviewsupplemented by extensive input fromexperts and the experience of the USCenters for Disease Control and Pre-vention (CDC) and takes into accountthe drugs and medical technology avail-able in the United States.

EVIDENCE ACQUISITIONThe literature was reviewed based onMEDLINE searches using the term Cha-gas disease with the subheadings evalu-ation, diagnosis, prognosis, treatment,congenital, gastrointestinal, transplant,HIV, nifurtimox, benznidazole, clinicaltrials, adverse effects, and the limiter hu-

man. Articles published from 1966through July 1, 2007, in English, Span-ish, and Portuguese were included.These searches yielded 3820 poten-tially relevant articles (FIGURE 1). Otherpertinent articles, reports, mono-graphs, and book chapters were lo-cated through citations in the litera-ture or suggested by experts. Recentguidelines by expert committees in Bra-zil, Argentina, and Spain were also con-sulted.19-21 We reviewed titles, ab-stracts, or both to determine relevanceto this article. Observational studieswere cited if the design and outcomemeasures were clearly described and ap-propriate. Prospective drug treatmenttrials were included if criteria for pa-tient inclusion and group allocationwere clearly described and unbiased andif outcome measures were well de-fined and appropriate. Trials of drugsother than benznidazole and nifurti-mox were excluded, because no otherdrugs have been demonstrated to haveefficacy in human T cruzi infection.

EVIDENCE SYNTHESISClinical Aspects of Chagas Disease

Most T cruzi–infected persons passthrough the acute phase with mildsymptoms or a nonspecific febrile ill-ness; most acute infections are unrec-ognized.1 Severe manifestations, suchas acute myocarditis or meningoen-cephalitis, are rarely detected.1 Theacute phase lasts 4 to 8 weeks.Infected individuals then enter thechronic phase and, in the absence ofsuccessful treatment, remain infectedfor life. Persons with chronic infectionbut without signs or symptoms areconsidered to have the indeterminateform of Chagas disease. The strict defi-nition of the indeterminate formrequires positive anti–T cruzi serologyresults, no symptoms or physicalexamination abnormalities, normal12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG)findings, and normal findings onradiological examination of the chest,esophagus, and colon.20

Approximately 70% to 80% ofinfected individuals remain in the inde-terminate form throughout their

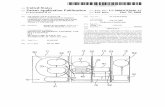

Figure 1. Study Selection

6 Monographs and reports7 Book chapters2 Electronic references

4 Clinical treatment trials excluded1 Unclear entry criteria

1 Not a trial of benznidazoleor nifurtimox

2 Biased or unclear groupassignment

8 Clinical treatment trials for chronicChagas disease identified

3820 References identified inMEDLINE search

Relevant articles from review of titleor abstract reviewed in depth

4 Clinical treatment trials for chronicChagas disease included

91 References included inbackground sections

EVALUATION AND TREATMENT OF CHAGAS DISEASE IN THE UNITED STATES

2172 JAMA, November 14, 2007—Vol 298, No. 18 (Reprinted) ©2007 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ on 02/25/2013

lives, whereas as many as 20% to 30%of those who initially have the indeter-minate form progress over a period ofyears to decades to clinically evident dis-ease, most commonly affecting theheart.22,23 Affected patients have a chronicinflammatory process that involves allheart chambers, conduction system dam-age, and often an apical aneurysm. Thepathogenesis is hypothesized to in-volve parasite persistence in cardiac tis-sue and immune-mediated myocardialinjury.24 The earliest manifestations areusually conduction system abnormali-ties, most frequently right bundle-branch block or left anterior fascicularblock and segmental left ventricular wallmotion abnormalities.23 Later manifes-tations include (1) complex ventricularextrasystoles and nonsustained and sus-tained ventricular tachycardia; (2) si-nus node dysfunction, usually leading tosinus bradycardia; (3) high-degree heartblock; (4) pulmonary and systemicthromboembolic phenomena due tothrombus formation in the dilated leftventricle or aneurysm; and (5) progres-sive dilated cardiomyopathy with con-gestive heart failure.17 These abnormali-ties lead to palpitations, presyncope,syncope, and a high risk of suddendeath.15 Often there are both bradyar-rhythmias and tachyarrhythmias. A sub-stantial proportion of patients have atypi-cal chest pain, hypothesized to be relatedto microvascular perfusion defects.24 Sev-eral classification schemes for Chagasheart disease are used in Latin America(BOX).20,25-28 The most important dis-criminating factors are ECG status andpresence or absence of congestive heartfailure. One system incorporates the re-cently updated American College ofCardiology/American Heart Associa-tion staging of congestive heartfailure.27,28

Chagas gastrointestinal tract dis-ease results from damage to intramu-ral neurons and predominantly affectsthe esophagus, colon, or both.18,29,30 Theesophageal effects comprise a spec-trum ranging from asymptomatic mo-tility disorders through mild achalasiato severe megaesophagus.31 Manifesta-tions include dysphagia, odynopha-

gia, esophageal reflux, weight loss, as-piration, cough, and regurgitation. Asin idiopathic achalasia, the risk ofesophageal carcinoma is increased.32,33

Colonic involvement leads to pro-longed constipation, abdominal pain,and fecaloma. Patients with megaco-lon have an increased risk of volvulusand consequent bowel ischemia. Gas-trointestinal tract involvement is lesscommon than Chagas heart disease, isseen almost exclusively in patients in-fected in the Southern Cone (Argen-tina, Bolivia, Chile, Paraguay, south-ern Peru, Uruguay, and parts of Brazil),and is rare in northern South America,Central America, and Mexico. This geo-graphical pattern is thought to be linkedto differences in parasite strains.34,35

In approximately 1% to 10% of preg-nancies in women with chronic T cruziinfection, the infant is born with con-genital infection.1,36,37 Most infected new-borns are asymptomatic or have non-specific findings suchas lowbirthweight,prematurity, or low Apgar scores. Othersigns include hepatosplenomegaly, ane-mia, and thrombocytopenia. Seriousmanifestations, including myocarditis,meningoencephalitis, andrespiratorydis-tress, are uncommon but carry ahighriskof mortality.37

Trypanosomacruzi infectioninpatientswhobecomeimmunocompromisedmayreactivate, leading to increases in intra-cellular parasite replication and parasit-emia detectable by microscopy. Reacti-vation occurs in a minority of patients

Box. Classification Schemes to Grade Presence and Severityof Chagas Cardiomyopathy

Modified Kuschnir Classification25

0: Normal ECG findings and normal heart size (usually based on chest radiography)

I: Abnormal ECG findings and normal heart size (usually based on chest radiography)

II: Left ventricular enlargement

III: Congestive heart failure

Brazilian Consensus Classification20

A: Abnormal ECG findings, normal echocardiogram findings, no signs of CHF

B1: Abnormal ECG findings, abnormal echocardiogram findings with LVEF �45%,no signs of CHF

B2: Abnormal ECG findings, abnormal echocardiogram findings with LVEF �45%,no signs of CHF

C: Abnormal ECG findings, abnormal echocardiogram findings, compensated CHF

D: Abnormal ECG findings, abnormal echocardiogram findings, refractory CHF

Modified Los Andes Classification26

IA: Normal ECG findings, normal echocardiogram findings, no signs of CHF

IB: Normal ECG findings, abnormal echocardiogram findings, no signs of CHF

II: Abnormal ECG findings, abnormal echocardiogram findings, no signs of CHF

III: Abnormal ECG findings, abnormal echocardiogram findings, CHF

Classification Incorporating American College of Cardiology/American HeartAssociation Staging27,28

A: Normal ECG findings, normal heart size, normal LVEF, NYHA class I

B: Abnormal ECG findings, normal heart size, normal LVEF, NYHA class I

C: Abnormal ECG findings, increased heart size, decreased LVEF, NYHA class II-III

D: Abnormal ECG findings, increased heart size, decreased LVEF, NYHA class IV

Abbreviations: CHF, congestive heart failure; ECG, electrocardiogram; LVEF, left ventricularejection fraction; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

EVALUATION AND TREATMENT OF CHAGAS DISEASE IN THE UNITED STATES

©2007 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. (Reprinted) JAMA, November 14, 2007—Vol 298, No. 18 2173

Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ on 02/25/2013

withchronicChagasdiseasewhoarecoin-fectedwithhumanimmunodeficiencyvi-rusorare receiving immunosuppressivedrugs.Althoughtheincidenceinpatientsundergoingtransplantationisnotwellde-fined,reactivationismorecommoninpa-tients treated with highly immunosup-pressiveregimens.38Reactivatedinfectionhasfeaturesthatdiffer fromthoseofacuteinfection,andpatientswithdrug-inducedimmunosuppression have a clinical pic-turedistinctfromthatofthosewithAIDS.In recipents of solid organ or bone mar-rowtransplants,reactivationisassociatedwith subcutaneous parasite-containingnodules, panniculitis, and myocarditis;centralnervous systeminvolvementhasrarely been reported.39-42 By contrast, inpatients with AIDS, the most commonmanifestationsaremeningoencephalitisandspace-occupyingcentralnervoussys-tem lesions that can be confused withtoxoplasmosis.43,44 Acute myocarditis,sometimessuperimposedonpreexistingcardiomyopathy due to chronic Chagasdisease, can lead to rapid-onset conges-tive heart failure.43,44

Diagnostic Considerations

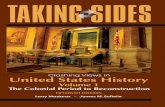

In the acute phase, the level of parasit-emia is high, and motile trypomasti-gotes are often detected by microscopyof fresh preparations of anticoagulated

blood or buffy coat (FIGURE 2).1 Theparasitemia decreases within 90 days ofinfection, even without treatment,45 andis undetectable by microscopy in thechronic phase. Nevertheless, low-level parasitemias account for trans-mission from chronically infected in-dividuals through blood transfusions,organ transplants, mother-to-infanttransmission, or via the vector. Diag-nosis of chronic Chagas disease relieson serologic methods, most com-monly enzyme-linked immunosor-bent assay and immunofluorescent an-tibody test. No single assay hassufficient sensitivity and specificity tobe relied on alone; 2 tests based on dif-ferent antigens or techniques are usedin parallel to increase the accuracy ofthe diagnosis.46,47 When results are dis-cordant, a third assay may be used toconfirm or refute the diagnosis, or re-peat sampling may be required.

Identification of the parasite by mi-croscopy, hemoculture, or polymer-ase chain reaction (PCR)-based meth-ods provides definitive diagnosis ofChagas disease. However, the sensitiv-ity of these methods is limited by thelevel of parasitemia, and a negative re-sult does not exclude the diagnosis.PCR-based methods have high sensi-tivity in acute T cruzi infection, but their

performance in chronic Chagas dis-ease is variable and currently they areprimarily research tools.48 Because posi-tive PCR results can occur in chronicinfection in the absence of reactiva-tion, laboratory monitoring for reacti-vated infection relies primarily on mi-croscopic examination of fresh bloodor buffy coat.

Programs to identify congenital infec-tion rely on serologic diagnosis of in-fected mothers, followed by micro-scopic and PCR-based examination ofcord blood, peripheral blood speci-mens, or both from their infants duringthe first 1 to 2 months of life.36,49 If re-sults of parasitological testing are nega-tive or if testing is not performed earlyin life, the infant should be tested by en-zyme-linked immunosorbent assay andimmunofluorescent antibody test at ages9 to 12 months, after the level of trans-ferred maternal antibody has de-creased.50 All other children of infectedmothers should also be tested.

Prognosis

The most important determinant ofprognosis for T cruzi–infected per-sons is the likelihood of progression toheart disease. Most reviews estimatethat 20% to 30% of infected persons willdevelop clinically apparent disease dur-ing their lifetimes, but estimates varyacross published studies.1,2,47,51 Thisvariability reflects, in part, method-ological differences such as study popu-lation, definitions of progression, andlength and completeness of follow-up. Animal models suggest that T cruzistrain is an important determinant ofclinical manifestations and severity52;other possible factors include the se-verity of the acute infection and age atwhich it occurred, host immune re-sponse, and human genetic fac-tors.2,35,53,54 Community-based studiesdemonstrate that survival of individu-als whose disease remains in the inde-terminate form is equivalent to that ofthe general population.23,55,56 Echocar-diography, radionuclide angiography,or autonomic testing may reveal mi-nor abnormalities in as many as one-third of T cruzi–infected individuals

Figure 2. Trypanosoma cruzi

A B

A, The trypomastigote forms of Trypanosoma cruzi in a peripheral blood smear from a patient with acuteChagas disease. Arrowhead indicates the kinetoplast (Giemsa stain, original magnification �1000). B, Nest ofT cruzi amastigotes within a cardiac myocyte in a patient with chronic Chagas disease. Arrowhead indicatesthe kinetoplast (hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification �1000). Courtesy of the Division of Parasitic Dis-eases, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

EVALUATION AND TREATMENT OF CHAGAS DISEASE IN THE UNITED STATES

2174 JAMA, November 14, 2007—Vol 298, No. 18 (Reprinted) ©2007 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ on 02/25/2013

with normal ECG and chest radiogra-phy results,57-59 but these findings havenot been shown to indicate a worseprognosis.

Ventricular conduction defects pre-cede onset of symptoms by years to de-cades.23 During 6.7 years of follow-upin one community-based study, rightbundle-branch block alone was asso-ciated with a 7-fold increase, and rightbundle-branch block with at least 1 ven-tricular extrasystole on resting ECGwith a 12-fold increase, in the risk ofmortality compared with seropositivepersons having normal ECG find-ings.23 Later manifestations associatedwith poor prognosis include ventricu-lar tachycardia or complex ventricu-lar arrhythmias, increased left ventricu-lar systolic diameter, and segmental orglobal left ventricular wall motion ab-normalities.15,59-62 A rigorous analysisidentified congestive heart failure (NewYork Heart Association class III or IV),cardiomegaly, left ventricular systolicdysfunction on echocardiography, non-sustained ventricular tachycardia on 24-hour ambulatory monitoring, low QRSvoltage, and male sex as the strongestpredictors of mortality.63 This study andothers confirm that congestive heartfailure and left ventricular ejection frac-tion less than 30% identify a group ofpatients with less than 30% survival at2 to 4 years.15,55,56,64 Patients with Cha-gas cardiomyopathy have sudden deathdue to ventricular arrhythmias or com-plete heart block, or die from intrac-table congestive heart failure or em-bolic phenomena.56,63,65 The presence ofan apical aneurysm is associated witha high risk of stroke.66

In selected patients with Chagas heartdisease, empirical use of amiodarone orangiotensin-converting enzyme inhibi-tors, or implantation of a pacemaker orintracardiac defibrillator, may improvesurvival.15,16,67 However, few controlledclinical trials have been conducted toevaluate the efficacy of specific pharma-cological treatment or devices in Cha-gas cardiomyopathy. Experience in Bra-zil demonstrates that survival after hearttransplantation for Chagas cardiomyo-pathy is equal to or better than that

among patients receiving transplants foridiopathic or ischemic dilated cardio-myopathy; careful management of im-munosuppressive therapy is essential.38,68

Longitudinal data to address theprognosis of Chagas gastrointestinaltract disease are sparse. Once diseaseis clinically apparent, progression isusually slow.18,69,70 There are no data tosuggest that antitrypanosomal therapyalters the course of the disease. Man-agement focuses on symptom amelio-ration through dietary, medical, andsurgical interventions.18

Evaluation of the Patient NewlyDiagnosed With Chagas Disease

Theinitialevaluationconsistsofthemedi-calhistory, includingevidenceofpoten-tialTcruziexposure inendemicareasviablood transfusion or other routes; com-plete physical examination; and resting12-lead ECG with a 30-second lead IIrhythm strip (FIGURE 3).23,71,72 The his-tory should include a thorough reviewof systems, with an emphasis on symp-toms suggestive of cardiac arrhythmias,early congestive heart failure, and gas-trointestinal tract disease. Infected per-sons should be counseled not to donateblood. Diagnostic screening should beofferedforchildrenofseropositivewom-en,familymembersofpatients,andotherindividuals with a history of potentialexposure to the parasite in endemicsettings.

For practical purposes, a seroposi-tive patient with no evidence of cardiacor gastrointestinal tract alterations evi-dent on this evaluation is considered tohave the indeterminate form, even ifchest radiography and barium examina-tion of the colon and esophagus are notperformed. Because the prognosis ofasymptomatic patients with normal ECGfindings is good, the predominant viewof the authors is that further initial evalu-ation is unnecessary and that subse-quent follow-up should rely on annualhistory, physical examination, and ECGfindings (Figure 3).

Forpatientswith symptoms, signs,orabnormal ECG findings, further evalu-ationshouldbetailoredtotheclinicalpic-ture. Patients with symptoms or ECG

changesconsistentwithChagasheartdis-ease23,71,73,74shouldundergoacomprehen-sivecardiacevaluation, includingambu-latory24-hourECGmonitoringtodetectarrhythmias; exercise testing to identifyexercise-inducedarrhythmiasandassessfunctionalcapacityandchronotropic re-sponse;and2-dimensionalechocardiog-raphytoassessbiventricularfunction,wallmotion, and structure. For asymptom-atic patients with nonspecific ECGchanges(eg, rsR�notmeetingcriteria forrightbundle-branchblockoraminor in-crease in PR interval), the need for fur-ther evaluation should be judged on anindividual basis.

Certain signs and symptoms raise im-mediate concern. Syncope, indicators ofventricular dysfunction, nonsustained orsustained ventricular tachycardia on rest-ing ECG or ambulatory monitoring, se-vere sinus node dysfunction, and high-degree heart block are major predictorsof sudden death.67 These findings shouldtrigger an intensive search for arrhyth-mias and conduction system abnormali-ties, proceeding to electrophysiologicstudies if indicated by the results of non-invasive testing. Chest pain warrantsevaluation for ischemia and noncardiaccauses, such as esophagitis.24,75,76 In pa-tients with chest pain, cardiac scintigra-phy scans may reveal perfusion defectsthought to reflect microvascular ische-mia or fibrosis, but angiography usu-ally shows normal coronary arteries.24

In patients without gastrointestinaltract symptoms, no barium studies arerecommended. Patients with symp-toms suggestive of esophageal or co-lonic involvement should undergo abarium swallow or enema, respec-tively. Following barium swallow, ra-diographs should be taken at 10 sec-onds and at 5 and 10 minutes.77

Esophageal manometry may detectmore subtle changes and may be indi-cated if results of the barium study areinconclusive.78,79 Endoscopy is not in-dicated for the diagnosis of mega-esophagus; however, patients with im-paired esophageal motility are atincreased risk of reflux esophagitis andesophageal carcinoma, and screeningfor these conditions may be indicated,

EVALUATION AND TREATMENT OF CHAGAS DISEASE IN THE UNITED STATES

©2007 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. (Reprinted) JAMA, November 14, 2007—Vol 298, No. 18 2175

Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ on 02/25/2013

especially if a change in symptoms hasoccurred. Patients with Chagas gastro-intestinal tract disease should be evalu-ated for heart disease following the al-gorithm outlined above.

Antitrypanosomal Drug Therapy

Benznidazole and nifurtimox are theonly drugs with proven efficacy againstChagas disease.2,80 Because benznida-zole is better tolerated, this drug isviewed by most experts as the first-

line treatment. Nevertheless, indi-vidual tolerance varies; if one drug mustbe discontinued, the other can be usedas an alternative. Neither drug is ap-proved in the United States; both canbe obtained from the CDC and used un-der investigational protocols. Adultsshould be treated with benznidazole(5-7 mg/kg per day) in 2 divided dosesfor 60 days or with nifurtimox (8-10mg/kg per day) in 3 divided doses for90 days. Consultations about diagnos-

tic testing, management, drug re-quests, and dosage regimens for spe-cial circumstances (eg, pediatric orimmunocompromised patients) shouldbe addressed to the CDC Division ofParasitic Diseases Public Inquiries line(770-488-7775; e-mail: [email protected]); the CDC Drug Service (404-639-3670); or, for emergencies after busi-ness hours, on weekends, and on federalholidays, the CDC Emergency Opera-tions Center (770-488-7100).

Figure 3. Baseline Evaluation of the Patient Newly Diagnosed With Chronic Trypanosoma cruzi Infection

Patient with new diagnosis of chronic Chagas disease

Confirm T cruzi infection with ≥2 serologic tests

Normal medical history, physical examination, and ECG Symptoms

Palpitations, syncope, presyncope Symptoms of congestive heart failure Thromboembolic phenomena Atypical chest pain

ECG findings Common Right bundle-branch block Incomplete right bundle-branch blocka

Left anterior fascicular block 1° AV block 2° AV block, Mobitz type I or II Complete AV block Bradycardia, sinus node dysfunction Ventricular extrasystoles, often frequent, multifocal, or paired Ventricular tachycardia, nonsustained or sustained Less common but clinically significant when present Atrial fibrillation or flutter Left bundle-branch block Low QRS voltage Q waves

Dysphagia for both liquids and solidsRegurgitation, aspirationOdynophagiaWeight lossProlonged constipation

Repeat history, physical examination, and ECG yearly

Perform complete cardiac evaluation Echocardiogram Ambulatory ECG monitoring Exercise test Other evaluation as indicated

Barium studies, other gastrointestinal evaluation as indicated

Perform complete medical history, physical examination, and 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) with 30-s rhythm strip

Advise patients not to donate blood

Test all children and subsequent newborns of infected women

Immediate evaluation if any of the following are present

Cardiac alterations Presyncope or syncope Transient ischemic attack Atypical chest pain Ventricular tachycardia High-grade atrioventricular (AV) block Marked bradyarrhythmia

Gastrointestinal symptoms Acute abdominal pain Rebound tenderness Other symptoms suggestive of bowel ischemia or volvulus

Cardiac symptoms or signs, or ECG findings suggestive of chronic Chagas disease

Gastrointestinal symptoms

aQRS interval 0.10 to 0.11 seconds in adults. Criteria based on the Minnesota Code Manual of Electrocardiographic Findings,74 with modifications from Maguireet al.71 Different criteria may be required for ECGs in children.

EVALUATION AND TREATMENT OF CHAGAS DISEASE IN THE UNITED STATES

2176 JAMA, November 14, 2007—Vol 298, No. 18 (Reprinted) ©2007 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ on 02/25/2013

Benznidazole (Radanil, Rochagan,Roche 7-1051), introduced in 1971, is anitroimidazole derivative active againstboth the trypomastigote and amastigoteforms.Thedrug is rapidlyabsorbed fromthegastrointestinal tract; theaveragebio-logical half-life is 12 hours. Eliminationis predominantly renal; 22% of excre-tion is fecal.Childrenhave feweradverseeffects than adults and tolerate higherdoses.Dermatologicadverseeffectsoccurin approximately 30% of patients andconsist of rashes due to photosensitiza-tion, rarelyprogressing toexfoliativeder-matitis. The dermatitis is usually mild tomoderate and manageable with topicalor low-dose systemic corticosteroids.However, the drug should be discontin-uedimmediately incaseofsevereorexfo-liative dermatitis or of dermatitis asso-ciated with fever and lymphadenopathy.Approximately 30% of patients experi-ence a dose-dependent peripheral neu-ropathy. It occurs most commonly latein the treatment course and should trig-ger cessation of treatment; it is nearlyalways reversible but may take monthsto resolve. Bone marrow suppression israreandshouldprompt immediate treat-ment interruption. Additional reportedadverse effects include anorexia andweight loss, nausea and/or vomiting,insomnia,anddysgeusia.Laboratorytest-ing (complete blood cell count and lev-els of hepatic enzymes, bilirubin, serumcreatinine, and blood urea nitrogen)should be performed before beginningtreatment; the complete blood cell countshould be repeated every 2 to 3 weeksduring the treatment course. Patientsshouldbemonitoredfordermatitisbegin-ning 9 to 10 days after initiation of treat-ment. Concurrent alcohol use can leadto disulfiram-like effects (abdominalcramps,nausea,vomiting, flushing,head-ache) and should be avoided.

Nifurtimox (Lampit, Bayer 2502), in-troduced in 1965, is a nitrofuran com-pound, also with activity against trypo-mastigotes and amastigotes.80 The drugis rapidly absorbed from the gastroin-testinal tract and extensively metabo-lized in the liver, where nitroreductionoccurs through cytochrome P450 reduc-tase. Elimination of metabolites is pre-

dominantly renal. In humans, plasmalevels peak at 1 hour after a single oraldose and have an elimination half-life of3 hours. Like benznidazole, nifurtimoxis better tolerated by children,51 and dos-age recommendations differ by age.

Adverse effects are frequent but usu-ally resolve when treatment is stopped.Gastrointestinal tract complaints occurin 30% to 70% of patients and includeanorexia leading to weight loss, nausea,vomiting, and abdominal discomfort.Symptomsofcentralnervoussystemtox-icity include irritability, insomnia, dis-orientation,and, lessoften, tremors.Moreserious but less common adverse effectsinclude paresthesias, polyneuropathy,and peripheral neuritis. The peripheralneuropathy is dose-dependent, appearslate in the treatment course, and shouldprompt interruption. Additional adverseeffects include dizziness or vertigo, ner-vous excitation, mood changes, andmyalgias. Laboratory testing (completeblood cell count and levels of hepaticenzymes,bilirubin,serumcreatinine,andblood urea nitrogen) should be per-formed before beginning treatment, 4 to6 weeks into the course, and at the endof treatment.Patients shouldbeweighedand monitored for symptoms and signsof peripheral neuropathy every 2 weeks,especially during the second and thirdmonths of treatment. Concurrent alco-holuseincreasestheriskofadverseeffectsand should be avoided.

Benznidazole and nifurtimox are bothmutagenic81,82 and have been reportedto increase risk of lymphomas in experi-mental animals.83,84 Although a higherincidence of neoplasms was reported ina small series of T cruzi–infected hearttransplant recipients,85 no increase in in-cidence of human lymphoma has beenreported among the larger population oftreated patients in countries where the2 drugs have been in use for decades.86

Nevertheless, definitive data on this is-sue are lacking.

Efficacy of Drug Treatmentfor Chagas Disease

Despite the public health importance ofChagas disease, few rigorous clinicaltrials have been conducted (TABLE 1).87-90

The complex natural history of the in-fection and inadequate tools to assesscure have made it difficult to define ap-propriate end points and follow-up in-tervals. The published randomized, pla-cebo-controlled trials assessed primarilyparasite-related outcomes, antibody-related outcomes, or both rather thanclinical outcomes.

Treatment of Acuteand Congenital Infection

Based on several early trials and sub-sequent clinical experience in acuteand early congenital Chagas disease,both drugs are known to reducesymptom severity and to shorten theclinical course and duration of detect-able parasitemia.2,45,86,91 Parasitologicalcure is thought to occur in 60% to85% of patients in the acute phase andin more than 90% of congenitallyinfected infants treated in the firstyear of life.45,80,91,92 Geographic vari-ability in efficacy has been reportedfor acute93 and chronic94 infection andin animal models.95,96 Treatment ofinfected infants should begin as soonas the diagnosis is made; the drugs arewell tolerated in infancy.45,97 Neitherdrug is available in a pediatric formu-lation; for infants and young children,the tablets should be prepared in acompounding pharmacy to providethe appropriate dose.

Treatment in the Chronic Phase

In the 1990s, 2 randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trials ofbenznidazole for children aged 6 to 12years with asymptomatic T cruzi infec-tion demonstrated approximately 60%efficacy, as assessed by conversion frompositive to negative serology results 3to 4 years posttreatment (Table 1).87,88

In 1 trial, treated children also showeda marked reduction in positive xeno-diagnoses compared with the placebogroup.88 Benznidazole was well toler-ated in these pediatric trials (Table 1).Together with growing clinical expe-rience across Latin America, these stud-ies prompted recommendations forearly diagnosis and antitrypanosomaltherapy for all infected children.20,47 In

EVALUATION AND TREATMENT OF CHAGAS DISEASE IN THE UNITED STATES

©2007 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. (Reprinted) JAMA, November 14, 2007—Vol 298, No. 18 2177

Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ on 02/25/2013

a recently published, nonrandomized,nonblinded trial, benznidazole treat-ment appeared to slow the develop-ment and progression of Chagas car-diomyopathy in adults.90 Based on theseand other data, a number of expertsnow recommend treatment of adultswith chronic T cruzi infection in the ab-sence of advanced Chagas cardiomyo-pathy.90,98 A multicenter, randomized,double-blinded, placebo-controlled trialof benznidazole for patients with mildto moderate Chagas cardiomyopathy iscurrently under way.99 Data from thisstudy should help clarify treatment de-cisions for this group of patients.

Reactivated T cruzi Infection

Data from series of patients who under-went transplantation with reactivated in-fection showed that standard doses ofbenznidazole given for 30 to 180 days ledto resolution of signs and symptoms andreduced intensity of parasitemia.39-42 A

standard 60-day benznidazole regimendecreased parasitemia and resulted inclinical improvement in a small series ofpatients coinfected with human immu-nodeficiency virus and T cruzi.43 The op-timal duration of therapy in immuno-compromised patients and the usefulnessof secondary prophylaxis have not beenestablished.

Indications forAntitrypanosomal Therapy

Based on the literature reviewed above,recommendations forantitrypanosomaltherapy vary by phase and form of Cha-gas disease and by patient age and aregraded based on Infectious Diseases So-cietyofAmericaquality-of-evidencestan-dards.100 Drug therapy is recommendedinall casesof acuteandcongenital infec-tion,reactivatedinfection,andinchildren18yearsoryoungerwithchronicT cruziinfection(TABLE2).45,49,87,88,101 Foradultsaged19to50yearswithoutadvancedCha-

gas cardiomyopathy, antitrypanosomaldrug treatment should generally be of-fered.47,90,101,102 For those older than 50years, the risk of drug toxicity may behigherthaninyoungeradults,45 andtreat-ment is considered optional. The ratio-nale for treatment in adults rests on datathataresuggestive,butnotyetconclusive,that treatment may prevent or slow pro-gressionof cardiomyopathy.90 Individu-alized treatment decisions for adultsshouldtake intoaccount thecurrent lackofcertaintyofbenefit,prolongedcourse,andfrequentadverseeffects.Becausedrugtreatmentmightbeexpectedtoreducetheprobability of congenital transmission,strongerconsiderationmaybewarrantedforreproductive-agedwomen;neverthe-less, data are lacking on this issue.

Similarly, antitrypanosomal treat-ment should be given stronger consid-eration in situations in which future im-munosuppression is anticipated, forexample, among previously untreated

Table 1. Prospective Controlled Trials of Benznidazole or Nifurtimox for Chronic Chagas Disease in the Published Literature

Source Chagas Form Study Design Age, yLength of

Treatment, dComparison

GroupsSample

Size, No.Primary Outcome

of Interest, %Major Adverse Events or

Adverse Effects �5%

de Andradeet al,87

1996a

Indeterminate(n = 120)

Early Chagasheart disease

(n = 9)b

Randomized,double-blinded

7-12 60

Benznidazole,7.5 mg/kg per d

Placebo6465

Negativeseroconversion at

36 mo by AT-ELISA585

Maculopapular rashand pruritus

12.53.1

Sosa Estaniet al,88

1998

Indeterminate Randomized,double-blinded

6-12 60

Benznidazole,5 mg/kg per d

Placebo

Benznidazole,5 mg/kg per d

Placebo

5551

5551

Negativeseroconversion at 48

mo by F29-ELISA620

Xenodiagnosis-positive at

48 mo5

51

Intestinal colic

NRNR

NRNR

Couraet al,89

1997c

Indeterminatewith �2 of 3pretreatment

xeno-diagnosespositived

Randomized butapparently notdouble-blinded

Adultsd 30 Benznidazole,5 mg/kg

per dNifurtimox,

5 mg/kg per dPlacebo

26

2724

Posttreatment xeno-diagnosis positive

1.8

9.634.3

NR

NRNR

Viottiet al,90

2006d

Indeterminateand nonsevere

determinate

Alternateassignment

to benznidazoleor no

treatment;nonrandomized,

unblinded

Mean,39.4

30Benznidazole,5 mg/kg per dNo treatmentBenznidazole,5 mg/kg per dNo treatment

283283

283283

Progression

4.214.1

Mortality1.14.2

Severe allergic dermatitisprompting discontinuation

13.0NR

NRNR

Abbreviations: AT-ELISA, Antigen trypomastigote chemoluminescent enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; CI, confidence interval; ECG, electrocardiogram; HR, hazard ratio (mortalityadjusted for ejection fraction); F29-ELISA, flagellar calcium binding protein F29-antigen–based enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; IFA, indirect immunofluorescence assay; IHA,indirect hemagglutination; NR, not reported.

aEfficacy, 55.8% (95% confidence interval, 40.8%-67.0%) by intention-to-treat analysis based on AT-ELISA results.bAll children were asymptomatic but 9 had right bundle-branch block on ECG; no difference in distribution in treatment vs placebo groups.cNeither age nor clinical findings reported in article; presumed to have the indeterminate form.dChagas cardiac disease Kuschnir grades I or II; those with grade III, defined by presence of heart failure, were excluded. Distribution at study entry: 63.6% Kuschnir 0, 26.1% grade I,

10.2% grade II. See Box for definition of Kuschnir grades. Median follow-up, 9.8 years.

EVALUATION AND TREATMENT OF CHAGAS DISEASE IN THE UNITED STATES

2178 JAMA, November 14, 2007—Vol 298, No. 18 (Reprinted) ©2007 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ on 02/25/2013

T cruzi–infected patients awaiting or-gan transplantation, or patients coin-fected with human immunodeficency vi-rus. However, many experts recommendclose posttransplantation monitoring forreactivation through periodic micro-scopic examination of the buffy coat andclinical evaluations for signs and symp-toms such as fever and skin lesions, withtreatment only if reactivation is demon-strated. Reactivation risk varies consid-erably, depending primarily on the de-gree of immunosuppression.41,42

For patients with advanced Chagascardiomyopathy, antiparasitic treat-ment is not recommended, because ex-isting pathology will not be affected; thefocus is on supportive therapy. For pa-tients with Chagas gastrointestinal tractdisease, treatment decisions should bebased on the potential to decrease riskof development or progression of car-diomyopathy; the same factors, such asage and the possibility of congenitaltransmission, should be considered asfor other patients without advancedheart disease. In patients with mega-esophagus, drug absorption may be im-paired; treatment should be delayed un-til after corrective surgery. Benznidazoleand nifurtimox are contraindicated inpregnancy and in patients with severerenal or hepatic dysfunction.

Documentation of ResponseAfter Treatment

For monitoring response to treat-ment, hemoculture and direct exami-nation of blood or the buffy coat havehigh sensitivity in acute, early congen-ital, or reactivated T cruzi infection. Inthe chronic phase, there is no assay ofproven value for documentation of re-sponse. The 2 key placebo-controlledtrials each used a different experimen-tal serologic assay, neither of which iswidely available.87,88 Negative serocon-version by conventional assays occursafter successful treatment but takesyears to decades.102 PCR-based tech-niques are useful in monitoring fortreatment failure in persons with acuteT cruzi infection, but their variable sen-sitivity limits their usefulness in thosewith chronic Chagas disease.

COMMENTBecause of newly instituted blood bankscreening, increased community aware-ness, and demographic changes, UnitedStates–based clinicians are likely to en-counter more patients with Chagas dis-ease in the future. Baseline evaluationshould include complete history, physi-cal examination, and resting ECG witha 30-second lead II rhythm strip. Per-sons infected with T cruzi should becounseled not to donate blood, andscreening should be offered for familymembers with a similar exposure his-tory and for children of infected women.For patients with negative baseline

evaluation results, follow-up shouldconsist of yearly history, physical ex-amination, and ECG. Antitrypano-somal treatment should always be of-fered for T cruzi–infected children agedup to 18 years and for patients withacute or reactivated disease and shouldgenerally be offered to patients aged 19to 50 years without advanced heart dis-ease. For patients older than 50 yearswithout advanced cardiomyopathy, an-tiparasitic treatment is considered op-tional. Currently available drugs re-quire a prolonged course, pose asignificant risk of adverse effects, andrequire careful monitoring.

Table 2. Recommendations for Antitrypanosomal Drug Treatment According to ChagasDisease Phase and Form, Patient Age, and Clinical Status

Antitrypanosomal Drug Treatment by Chagas Disease Phase,Form, and Demographic Group

Strength ofRecommendation

and Qualityof Supporting

Evidencea

Should always be offeredAcute Trypanosoma cruzi infection AII

Early congenital T cruzi infection AII

Children aged �12 y with chronic T cruzi infection AI

Children aged 13-18 y with chronic T cruzi infection AIII

Reactivated T cruzi infection in patient with HIV/AIDS or otherimmunosuppression

AII

Should generally be offeredReproductive-age women BIII

Adults aged 19-50 y with indeterminate form, or mild to moderatecardiomyopathy (Kuschnir grades 0, I, or II)

BII

Impending immunosuppressionb BII

OptionalAdults aged �50 y without advanced cardiomyopathy

(Kuschnir grades 0, I, or II)CIII

Patients with Chagas gastrointestinal tract disease but withoutadvanced cardiomyopathyc

CIII

Should generally not be offeredAdvanced chagasic cardiomyopathy with congestive heart failure

(Kuschnir grade III)DIII

Megaesophagus with significant impairment of swallowing DIII

Should never be offeredDuring pregnancy EIII

Severe renal or hepatic insufficiency EIIIAbbreviation: HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.a Infectious Diseases Society of America quality of evidence standards for treatment recommendations.100 Strength

of recommendation graded A to E. A: Both strong evidence for efficacy and substantial clinical benefit supportrecommendation for use; should always be offered. B: Moderate evidence for efficacy, or strong evidence forefficacy but only limited benefit, support recommendation for use. Should generally be offered. C: Evidence forefficacy is insufficient to support a recommendation for or against use; or evidence for efficacy might not outweighadverse consequences or cost of treatment under consideration. Optional. D: Moderate evidence for lack ofefficacy or for adverse outcome supports recommendation against use. Should generally not be offered. E: Goodevidence for lack of efficacy or for adverse outcome supports recommendation against use. Should never beoffered. Quality of evidence supporting the recommendation graded as I to III. I: Evidence from at least 1 properlydesigned, randomized clinical trial. II: Evidence from at least 1 well-designed clinical trial without randomization,from cohort or case-controlled analytic studies (preferably from more than 1 center), or from multiple time-seriesstudies; or dramatic results from uncontrolled experiments. III: Evidence from opinions of respected authoritiesbased on clinical experience, descriptive studies, or reports of expert committees.

bFor example, previously untreated patients with HIV infection or awaiting organ transplant.cThere are no data to suggest that treatment affects progression of gastrointestinal tract disease. Decisions should

be based on the potential to decrease risk of development or progression of heart disease.

EVALUATION AND TREATMENT OF CHAGAS DISEASE IN THE UNITED STATES

©2007 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. (Reprinted) JAMA, November 14, 2007—Vol 298, No. 18 2179

Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ on 02/25/2013

Author Contributions: Drs Bern, Montgomery, andMoore had full access to all of the data in the studyand take responsibility for the integrity of the data andthe accuracy of the data analysis.Study concept and design: Bern, Montgomery,Herwaldt, Marin-Neto, Moore.Acquisition of data: Bern, Montgomery, Herwaldt,Rassi, Marin-Neto, Dantas, Maguire, Morillo, Moore.Analysis and interpretation of data: Bern, Montgomery,Herwaldt, Rassi, Marin-Neto, Dantas, Maguire,Acquatella, Kirchhoff, Gilman, Reyes, Salvatella, Moore.Drafting of the manuscript: Bern, Montgomery, Moore.Critical revision of the manuscript for important in-tellectual content: Bern, Montgomery, Herwaldt, Rassi,Marin-Neto, Dantas, Maguire, Acquatella, Morillo,Kirchhoff, Gilman, Reyes, Salvatella, Moore.Obtained funding: Herwaldt, Moore.Administrative, technical, or material support: Bern,Montgomery, Moore.Study supervision: Bern, Montgomery, Moore.Financial Disclosures: Dr Kirchhoff reported receiv-ing funding from a National Institutes of Health grantthrough a subcontract with InBios International Inc;having consultancy relationships with Abbott Labo-ratories and Ortho-Clinical Diagnostics Inc; receivingpayments through licensing agreements with AbbottLaboratories, Ortho-Clinical Diagnostics Inc, and QuestDiagnostics Inc; and owning an equity interest in Gold-finch Diagnostics Inc. All other authors declare no con-flicts of interest.Funding/Support: This study was supported by intra-mural funding from the US Centers for Disease Con-trol and Prevention (CDC).Role of the Sponsor: Employees of the CDC were in-volved in the design and conduct of the study; the col-lection, management, analysis, and interpretation ofthe data; and the preparation, review, and approvalof the manuscript.Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this re-port are those of the authors and do not necessarilyrepresent the views of the CDC.Additional Contributions: We thank Sergio Sosa Es-tani, MD, PhD (Tulane University, New Orleans, Loui-siana, and Centro National de Diagnostico e Investiga-cion de Endemo-epidemias, ANLIS “Dr Carlos G.Malbran,” Ministerio de Salud y Ambiente, Buenos Aires,Argentina), Monica Parise, MD, Mark Eberhard, PhD,and Matt Kuehnert, MD (CDC, Atlanta, Georgia), DanColley, PhD, and Rick Tarleton, PhD (University of Geor-gia, Athens), and Dennis Juranek, DVM (retired, CDC,Atlanta), for scientific review and helpful comments;Henry S. Bishop (CDC, Atlanta) for providing parasiteimages; and Carolyn Erling (CDC, Atlanta) for admin-istrative support. None of these individuals received com-pensation for their contributions.

REFERENCES

1. Maguire JH. Trypanosoma. In: Gorbach SL, Bart-lett JG, Blacklow NR, eds. Infectious Diseases. 3rd ed.Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004:2327-2334.2. Magill AJ, Reed SG. American trypanosomiasis. In:Strickland GT, ed. Hunter’s Tropical Medicine andEmerging Diseases. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saun-ders Co; 2000:653-664.3. Benchimol Barbosa PR. The oral transmission of Cha-gas’ disease: an acute form of infection responsiblefor regional outbreaks. Int J Cardiol. 2006;112(1):132-133.4. Organizacion Panamericana de la Salud. Estima-cion cuantitativa de la enfermedad de Chagas en lasAmericas. Montevideo, Uruguay: Organizacion Pana-mericana de la Salud; 2006.5. Remme JHF, Feenstra P, Lever PR, et al. Tropicaldiseases targeted for elimination: Chagas disease, lym-phatic filariasis, onchocerciasis, and leprosy. In: JamisonDT, Breman JG, Measham AR, et al, eds. Disease Con-

trol Priorities in Developing Countries. New York, NY:The World Bank and Oxford University Press; 2006:433-449.6. Regional PAHO Regional Program on ChagasDisease. Pan American Health Organization Web site.h t tp : //www.paho .o rg/eng l i sh/ad/dpc/cd/dch-program-page.htm. Accessed July 1, 2007.7. Kirchhoff LV. Changing epidemiology and ap-proaches to therapy for Chagas disease. Curr InfectDis Rep. 2003;5(1):59-65.8. Leiby DA, Herron RM Jr, Read EJ, Lenes BA, StumpfRJ. Trypanosoma cruzi in Los Angeles and Miami blooddonors: impact of evolving donor demographicson seroprevalence and implications for transfusiontransmission. Transfusion. 2002;42(5):549-555.9. Bradley KK, Bergman DK, Woods JP, Crutcher JM,Kirchhoff LV. Prevalence of American trypanosomia-sis (Chagas disease) among dogs in Oklahoma. J AmVet Med Assoc. 2000;217(12):1853-1857.10. Pung OJ, Banks CW, Jones DN, Krissinger MW.Trypanosoma cruzi in wild raccoons, opossums, andtriatomine bugs in southeast Georgia, U.S.A. J Parasitol.1995;81(2):324-326.11. Herwaldt BL, Grijalva MJ, Newsome AL, et al. Useof polymerase chain reaction to diagnose the fifth re-ported US case of autochthonous transmission of Try-panosoma cruzi, in Tennessee, 1998. J Infect Dis. 2000;181(1):395-399.12. Dorn PL, Perniciaro L, Yabsley MJ, et al. Autoch-thonous transmission of Trypanosoma cruzi, Louisiana.Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13(4):605-607.13. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Blooddonor screening for Chagas disease—United States,2006-2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56(7):141-143.14. Chagas’ Biovigilance Network. AABB Web site.http://www.aabb.org/Content/Programs_and_Ser-vices/Data_Center/Chagas/. Accessed September 12,2007.15. Rassi A Jr, Rassi A, Rassi SG. Predictors of mor-tality in chronic Chagas disease: a systematic reviewof observational studies. Circulation. 2007;115(9):1101-1108.16. Rassi A Jr, Rassi A, Little WC. Chagas’ heart disease.Clin Cardiol. 2000;23(12):883-889.17. Hagar JM, Rahimtoola SH. Chagas’ heart disease.Curr Probl Cardiol. 1995;20(12):825-924.18. de Oliveira RB, Troncon LE, Dantas RO, Meng-helli UG. Gastrointestinal manifestations of Chagas’disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93(6):884-889.19. Gascon J, Albajar P, Canas E, et al. Diagnosis, man-agement and treatment of chronic Chagas’ heart dis-ease in areas where Trypanosoma cruzi infection is notendemic [in Spanish]. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2007;60(3):285-293.20. Ministerio da Saude Brasil. Brazilian Consensus onChagas disease [in Portuguese]. Rev Soc Bras MedTrop. 2005;38(suppl 3):7-29.21. Sociedad Argentina de Cardiologıa. Consejo deEnfermedad de Chagas. Rev Argent Cardiol. 2002;70(suppl 1):1-87.22. Pinto Dias JC. Natural history of Chagas’ disease.Arq Bras Cardiol. 1995;65(4):359-366.23. Maguire JH, Hoff R, Sherlock I, et al. Cardiac mor-bidity and mortality due to Chagas’ disease: prospec-tive electrocardiographic study of a Braziliancommunity. Circulation . 1987;75(6):1140-1145.24. Marin-Neto JA, Cunha-Neto E, Maciel BC, Si-moes MV. Pathogenesis of chronic Chagas heartdisease. Circulation. 2007;115(9):1109-1123.25. Kuschnir E, Sgammini H, Castro R, Evequoz C,Ledesma R, Brunetto J. Evaluation of cardiac func-tion by radioisotopic angiography, in patients withchronic Chagas cardiopathy [in Spanish]. Arq BrasCardiol. 1985;45(4):249-256.

26. Carrasco HA, Barboza JS, Inglessis G, Fuen-mayor A, Molina C. Left ventricular cineangiographyin Chagas’ disease: detection of early myocardialdamage. Am Heart J. 1982;104(3):595-602.27. Acquatella H. Echocardiography in Chagas heartdisease. Circulation. 2007;115(9):1124-1131.28. Hunt SA. ACC/AHA 2005 guideline update forthe diagnosis and management of chronic heart fail-ure in the adult: a report of the American College ofCardiology/American Heart Association Task Force onPractice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46(6):e1-e82.29. de Rezende JM, Moreira H. Chagasic mega-esophagus and megacolon: historical review and pres-ent concepts. Arq Gastroenterol. 1988;25(special is-sue):32-43.30. Mota E, Todd CW, Maguire JH, et al. Mega-esophagus and seroreactivity to Trypanosoma cruziin a rural community in northeast Brazil. Am J TropMed Hyg. 1984;33(5):820-826.31. de Oliveira RB, Rezende Filho J, Dantas RO, IazigiN. The spectrum of esophageal motor disorders in Cha-gas’ disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90(7):1119-1124.32. Atıas A. A case of congenital chagasic mega-esophagus: evolution until death caused by esopha-geal neoplasm, at 27 years of age [in Spanish]. RevMed Chil. 1994;122(3):319-322.33. Brucher BL, Stein HJ, Bartels H, Feussner H, Siew-ert JR. Achalasia and esophageal cancer: incidence,prevalence, and prognosis. World J Surg. 2001;25(6):745-749.34. Miles MA, Feliciangeli MD, de Arias AR. Ameri-can trypanosomiasis (Chagas’ disease) and the role ofmolecular epidemiology in guiding control strategies.BMJ. 2003;326(7404):1444-1448.35. Campbell DA, Westenberger SJ, Sturm NR. Thedeterminants of Chagas disease: connecting parasiteand host genetics. Curr Mol Med. 2004;4(6):549-562.36. Bittencourt AL. Congenital Chagas disease. AmJ Dis Child. 1976;130(1):97-103.37. Torrico F, Alonso-Vega C, Suarez E, et al. Mater-nal Trypanosoma cruzi infection, pregnancy out-come, morbidity, and mortality of congenitally in-fected and non-infected newborns in Bolivia. Am J TropMed Hyg. 2004;70(2):201-209.38. Bocchi EA, Bellotti G, Mocelin AO, et al. Hearttransplantation for chronic Chagas’ heart disease. AnnThorac Surg. 1996;61(6):1727-1733.39. Fiorelli AI, Stolf NA, Honorato R, et al. Later evo-lution after cardiac transplantation in Chagas’ disease.Transplant Proc. 2005;37(6):2793-2798.40. Maldonado C, Albano S, Vettorazzi L, et al. Usingpolymerase chain reaction in early diagnosis of re-activated Trypanosoma cruzi infection after hearttransplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2004;23(12):1345-1348.41. Riarte A, Luna C, Sabatiello R, et al. Chagas’ dis-ease in patients with kidney transplants: 7 years of ex-perience 1989-1996. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29(3):561-567.42. Altclas J, Sinagra A, Dictar M, et al. Chagas dis-ease in bone marrow transplantation: an approach topreemptive therapy. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2005;36(2):123-129.43. Sartori AM, Ibrahim KY, Nunes Westphalen EV,et al. Manifestations of Chagas disease (American try-panosomiasis) in patients with HIV/AIDS. Ann TropMed Parasitol. 2007;101(1):31-50.44. Vaidian AK, Weiss LM, Tanowitz HB. Chagas’disease and AIDS. Kinetoplastid Biol Dis. 2004;3(1):2.45. Wegner DH, Rohwedder RW. The effect ofn i fu r t imox in acu te Chagas ’ in fec t ion .Arzneimittelforschung. 1972;22(9):1624-1635.46. Kirchhoff LV. American trypanosomiasis (Cha-gas disease). In: Guerrant RL, Walker DH, Weller PF,

EVALUATION AND TREATMENT OF CHAGAS DISEASE IN THE UNITED STATES

2180 JAMA, November 14, 2007—Vol 298, No. 18 (Reprinted) ©2007 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ on 02/25/2013

eds. Tropical Infectious Diseases: Principles, Patho-gens and Practice. 2nd ed. New York, NY: ChurchillLivingstone; 2006:1082-1094.47. WHO Expert Committee. Control of ChagasDisease. Brasilia, Brazil: World Health Organization;2002. WHO technical report series 905.48. Castro AM, Luquetti AO, Rassi A, Rassi GG, Chi-ari E, Galvao LM. Blood culture and polymerase chainreaction for the diagnosis of the chronic phase of hu-man infection with Trypanosoma cruzi. Parasitol Res.2002;88(10):894-900.49. Freilij H, Altcheh J. Congenital Chagas’ disease:diagnostic and clinical aspects. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21(3):551-555.50. Congenital infection with Trypanosoma cruzi: frommechanisms of transmission to strategies for diagno-sis and control. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2003;36(6):767-771.51. Miles MA. American trypanosomiasis (Chagasdisease). In: Cook GC, Zumla AI, eds. Manson’s Tropi-cal Disease. London, England: Elsevier Science Lim-ited; 2003:1325-1335.52. Andersson J, Orn A, Sunnemark D. Chronic mu-rine Chagas’ disease: the impact of host and parasitegenotypes. Immunol Lett. 2003;86(2):207-212.53. Bustamante JM, Rivarola HW, Fernandez AR, et al.Indeterminate Chagas’ disease: Trypanosoma cruzistrain and re-infection are factors involved in the pro-gression of cardiopathy. Clin Sci (Lond). 2003;104(4):415-420.54. Laucella SA, Postan M, Martin D, et al. Fre-quency of interferon-gamma-producing T cells spe-cific for Trypanosoma cruzi inversely correlates withdisease severity in chronic human Chagas disease.J Infect Dis. 2004;189(5):909-918.55. Acquatella H, Catalioti F, Gomez-Mancebo JR,Davalos V, Villalobos L. Long-term control of Chagasdisease in Venezuela: effects on serologic findings, elec-trocardiographic abnormalities, and clinical outcome.Circulation. 1987;76(3):556-562.56. Carrasco HA, Parada H, Guerrero L, Duque M,Duran D, Molina C. Prognostic implications of clini-cal, electrocardiographic and hemodynamic findingsin chronic Chagas’ disease. Int J Cardiol. 1994;43(1):27-38.57. Acquatella H, Schiller NB, Puigbo JJ, et al. M-mode and two-dimensional echocardiography inchronic Chagas heart disease: a clinical and patho-logic study. Circulation. 1980;62(4):787-799.58. Marin-Neto JA, Bromberg-Marin G, Pazin-FilhoA, Simoes MV, Maciel BC. Cardiac autonomic impair-ment and early myocardial damage involving the rightventricle are independent phenomena in Chagas’disease. Int J Cardiol. 1998;65(3):261-269.59. Pazin-Filho A, Romano MM, Almeida-Filho OC,et al. Minor segmental wall motion abnormalities de-tected in patients with Chagas’ disease have adverseprognostic implications. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2006;39(4):483-487.60. Viotti R, Vigliano C, Lococo B, et al. Clinical pre-dictors of chronic chagasic myocarditis progression [inSpanish]. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2005;58(9):1037-1044.61. Viotti R, Vigliano C, Lococo B, et al. Exercise stresstesting as a predictor of progression of early chronicChagas heart disease. Heart. 2006;92(3):403-404.62. Viotti RJ, Vigliano C, Laucella S, et al. Value ofechocardiography for diagnosis and prognosis ofchronic Chagas disease cardiomyopathy without heartfailure. Heart. 2004;90(6):655-660.63. Rassi A Jr, Rassi A, Little WC, et al. Develop-ment and validation of a risk score for predicting deathin Chagas’ heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(8):799-808.64. Mady C, Cardoso RH, Barretto AC, da Luz PL, Bel-lotti G, Pileggi F. Survival and predictors of survival inpatients with congestive heart failure due to Chagas’cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1994;90(6):3098-3102.

65. Salles G, Xavier S, Sousa A, Hasslocher-MorenoA, Cardoso C. Prognostic value of QT interval para-meters for mortality risk stratification in Chagas’ dis-ease: results of a long-term follow-up study.Circulation. 2003;108(3):305-312.66. Carod-Artal FJ. Chagas cardiomyopathy and is-chemic stroke. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2006;4(1):119-130.67. Rassi A Jr, Rassi SG, Rassi A. Sudden death in Cha-gas’ disease. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2001;76(1):75-96.68. Bocchi EA, Fiorelli A; First Guidelines Group for HeartTransplantation of the Brazilian Society of Cardiology.The paradox of survival results after heart transplanta-tion for cardiomyopathy caused by Trypanosoma cruzi.Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;71(6):1833-1838.69. Castro C. Longitudinal radiological study of theesophagus in Chagas disease. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz.1999;94(suppl 1):329-330.70. Castro C, Macedo V, Rezende JM, Prata A. Lon-gitudinal radiologic study of the esophagus, in an en-demic area of Chagas disease, in a period of 13 years[in Portuguese]. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 1994;27(4):227-233.71. Maguire JH, Mott KE, Souza JA, Almeida EC, Ra-mos NB, Guimaraes AC. Electrocardiographic classi-fication and abbreviated lead system for population-based studies of Chagas’ disease. Bull Pan Am HealthOrgan. 1982;16(1):47-58.72. Lazzari JO, Pereira M, Antunes CM, et al. Diag-nostic electrocardiography in epidemiological studiesof Chagas’ disease: multicenter evaluation of a stan-dardized method. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 1998;4(5):317-330.73. Maguire JH, Mott KE, Lehman JS, et al. Relation-ship of electrocardiographic abnormalities and sero-positivity to Trypanosoma cruzi within a rural com-munity in northeast Brazil. Am Heart J. 1983;105(2):287-294.74. Prineas RJ, Crowe RS, Blackburn H. The Minne-sota Code Manual of Electrocardiographic Findings.Boston, MA: John Wright; 1982.75. Marin-Neto JA, Marzullo P, Marcassa C, et al. Myo-cardial perfusion abnormalities in chronic Chagas’ dis-ease as detected by thallium-201 scintigraphy. Am JCardiol. 1992;69(8):780-784.76. Simoes MV, Dantas RO, Ejima FH, MeneghelliUG, Maciel BC, Marin-Neto JA. Esophageal origin ofprecordial pain in chagasic patients with normal sub-epicardial coronary arteries [in Portuguese]. Arq BrasCardiol. 1995;64(2):103-108.77. Meneghelli UG, Peria FM, Darezzo FM, et al. Clini-cal, radiographic, and manometric evolution of esoph-ageal involvement by Chagas’ disease. Dysphagia.2005;20(1):40-45.78. Dantas RO. Dysphagia in patients with Chagas’disease. Dysphagia. 1998;13(1):53-57.79. Dantas RO, Deghaide NH, Donadi EA. Esopha-geal manometric and radiologic findings in asymp-tomatic subjects with Chagas’ disease. J ClinGastroenterol. 1999;28(3):245-248.80. Rodriques Coura J, deCastro SL. A critical reviewon Chagas disease chemotherapy. Mem Inst Os-waldo Cruz. 2002;97(1):3-24.81. Ferreira RCC, Ferreira LCS. Mutagenicity of nifur-timox and benznidazole in the Salmonella microsomaassay. Braz J Med Biol Res. 1986;19(1):19-25.82. Gorla NB, Ledesma OS, Barbieri GP, Larripa IB.Thirteenfold increase of chromosomal aberrations non-randomly distributed in chagasic children treated withnifurtimox. Mutat Res. 1989;224(2):263-267.83. Teixeira AR, Cordoba JC, Souto Maior I, Solor-zano E. Chagas’ disease: lymphoma growth in rab-bits treated with benznidazole. Am J Trop Med Hyg.1990;43(2):146-158.84. Teixeira AR, Silva R, Cunha Neto E, Santana JM,Rizzo LV. Malignant, non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas in Try-panosoma cruzi-infected rabbits treated withnitroarenes. J Comp Pathol. 1990;103(1):37-48.

85. Bocchi EA, Higuchi ML, Vieira ML, et al. Higher in-cidence of malignant neoplasms after heart transplan-tation for treatment of chronic Chagas’ heart disease.J Heart Lung Transplant. 1998;17(4):399-405.86. Kirchhoff LV. Chagas disease: Americantrypanosomiasis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1993;7(3):487-502.87. de Andrade AL, Zicker F, de Oliveira RM, et al.Randomised trial of efficacy of benznidazole in treat-ment of early Trypanosoma cruzi infection. Lancet.1996;348(9039):1407-1413.88. Sosa Estani S, Segura EL, Ruiz AM, Velazquez E,Porcel BM, Yampotis C. Efficacy of chemotherapy withbenznidazole in children in the indeterminate phaseof Chagas’ disease. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;59(4):526-529.89. Coura JR, de Abreu LL, Willcox HP, Petana W.Comparative controlled study on the use of benzni-dazole, nifurtimox and placebo, in the chronic formof Chagas’ disease, in a field area with interruptedtransmission, I: preliminary evaluation [in Portuguese].Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 1997;30(2):139-144.90. Viotti R, Vigliano C, Lococo B, et al. Long-term car-diac outcomes of treating chronic Chagas disease withbenznidazole versus no treatment: a nonrandomized trial.Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(10):724-734.91. Cancado JR, Brener Z. Terapeutica. In: Brener Z,Andrade Z, eds. Trypanosoma cruzi e doenca de Cha-gas. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Guanabara Koogan; 1979:362-424.92. Altcheh J, Biancardi M, Lapena A, Ballering G, FreilijH. Congenital Chagas disease: experience in the Hos-pital de Ninos, Ricardo Gutıerrez, Buenos Aires, Ar-gentina [in Spanish]. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2005;38(suppl 2):41-45.93. Rassi A, Ferreira HO. Tentativas de tratmento es-pecifico da fase aguda da doenca de Chagas com nifur-timox em esquema de duracao prolongada. Rev SocBras Med Trop. 1971;5:235-262.94. Boainain E. Tratamento etiologico da doenca deChagas na fase cronica. Rev Goiania Med. 1979;25:1-60.95. Camandaroba EL, Reis EA, Goncalves MS, ReisMG, Andrade SG. Trypanosoma cruzi: susceptibilityto chemotherapy with benznidazole of clones iso-lated from the highly resistant Colombian strain. RevSoc Bras Med Trop. 2003;36(2):201-209.96. Veloso VM, Carneiro CM, Toledo MJ, et al. Varia-tion in susceptibility to benznidazole in isolates de-rived from Trypanosoma cruzi parental strains. MemInst Oswaldo Cruz. 2001;96(7):1005-1011.97. Russomando G, de Tomassone MM, de GuillenI, et al. Treatment of congenital Chagas’ disease di-agnosed and followed up by the polymerase chainreaction. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;59(3):487-491.98. Sosa-Estani S, Segura EL. Etiological treatment inpatients infected by Trypanosoma cruzi: experiencesin Argentina. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2006;19(6):583-587.99. The BENEFIT trial: evaluation of the use of an an-tiparasital drug (benznidazole) in the treatment ofchronic Chagas’ disease. http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT00123916. Accessibility verified October 11,2007.100. Gross PA, Barrett TL, Dellinger EP, et al; Infec-tious Diseases Society of America. Purpose of qualitystandards for infectious diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;18(3):421.101. Estani SS, Segura EL. Treatment of Trypano-soma cruzi infection in the undetermined phase: ex-perience and current guidelines of treatment inArgentina. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1999;94(suppl1):363-365.102. Rassi A, Luquetti AO. Specific treatment for Try-panosoma cruzi infection (Chagas disease). In: TylerKM, Miles MA, eds. American Trypanosomiasis. Bos-ton, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2003:117-125.

EVALUATION AND TREATMENT OF CHAGAS DISEASE IN THE UNITED STATES

©2007 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. (Reprinted) JAMA, November 14, 2007—Vol 298, No. 18 2181

Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ on 02/25/2013