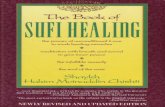

EARLY SUFI WOMEN (BOOK REVIEW)

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of EARLY SUFI WOMEN (BOOK REVIEW)

EARLY SUFI WOMEN Dhikr an-niswa al-muta ‘abbidāt as sūfiyyāt

Abū ‘Abd ar-Rahmān ās-SulamīEdited and Translated by Rkia E. Cornell From the Riyadh

Manuscript With Introduction and Notes by Rkia Elaroui Cornell

“This earliest known work in Islam devoted entirely towomen's spirituality was written by the Persian SufiAbu 'Abd ar-Rahman as-Sulami. The long-lost textprovides portraits of 80 Sufi women who lived in thecentral Islamic lands between the 8th and 11thcenturies C.E. As spiritual masters and exemplars ofIslamic piety, they served as respected teachers andguides in the same way as did Muslim men, oftensurpassing men in their understanding of Sufi doctrine,the Qur'an, and Islamic spirituality. This bilingualedition includes pages from 10th-century manuscript.”1

As accurate as this description is, it does not

begin to convey the beauty and scholarship within this

volume, primarily because it does not include a

reference to Rkia E. Cornell’s2 elegant, fifty-two page

1 Amazon.com description of Early Sufi Women.

2 Assistant Professor of the Practice of Arabic at Duke University, 1991-2000; Research Associate Professor of Arabic Studies, University of Arkansas, 200-2006; Faculty of Theology Dissertation (forthcoming) at the Free University of Amsterdam. She publishedEarly Sufi Women in 1999 and is currently writing a book on Rabi’a al-Adawiyya, an advanced reder in pre-modern Arabic literature and an Arabic edition of Abu ‘Abd al-Rahman al-Sulami’s haqa’iq al-tafsir. Vincent J. Cornell is her husband.

1

Introduction in which, “she explains how to read its

laconic style and teases considerable information from

it with the aid of historical context and comparative

observations.”3 Without the richness and sensitivity of

Cornell’s introduction, A Memorial of Female Sufi Devotees by

Abu ‘Abd ar-Rahmān Muhammad ibn al-Husayn b. Muhammad

as-Sulamī (365/976-412/1021) would be a well translated

example of the genre that, remarkably, focuses on Sufi

women, but would lack the scholarly insight into the

lives, locations and times that bring to life the

spirituality of the eighty four women4 as-Sulamī

presents and his extraordinary perspective in doing so.

For this reason, this review focuses on the invaluable

contextual insights contained in Cornell’s

Introduction. The structure of her introduction is

noteworthy, in that it consists of chapters and sub

chapters in which she reveals a broad scope of Islamic

historical and theological knowledge, as well as3 Carl Ernst, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Foreward4 Actually, two of the women are presented twice.

2

impressive scholarly research. While this essay

reviews information gleaned from all of the chapters of

the Introduction, special attention is given to the

chapter entitled, ”As-Sulamī’s Book of Sufi Women” in

which the sub chapters, “Recovering the Text,”

“Organizing the Text,” and “A Hermeneutic of

Remembrance” are found, and the chapter entitled, “As-

Sulamī’s View of Women’s Sufism” containing the “A

Theology of Servitude” and “Institutions of Women’s

Sufism” sub chapters.

The chapter entitled, “As-Sulamī and His Sufi

Women” begins with the sub chapter, “A Veiled

Tradition,” in which Cornell identifies one of the

earliest and most influential treatments of the origins

of Sufism and the nature and practice of its doctrines

as, Kitāb at-tararruf li-madhab ahl at-taṣawwuf (Introduction to

the Methodology of the Sufis) by Abū Bakr l-Kalābadhī

of Bukhara (d.308/990).5 After an extensive discussion

5 p. 15

3

of the word “Sufi”, Kalābadhi ends the chapter with the

following encounter between the Egyptian Sufi, Dhū an-

Nun al Misri (d.246/861) and an unnamed Sufi woman.6

“Dhū an-Nun said, ‘I saw a woman on the coast of Syria

and asked her, “Where are you coming from? (May God

have Mercy on you)” She replied, “From a people who are

moved to rise from their bed at night (calling on their

Lord in fear and hope).” Then I asked, “And where are

you going?” She said, “To men whom neither worldly

commerce nor striving after gain can divert them from

the remembrance of God.” Cornell comments, “Dhū an-

Nun, who created the Sufi doctrine of spiritual states

(aḥwal) and stations (maqāmāt) is reminded by this woman

that the essence of Sufism is not to be found in

paranormal states, but in spiritual practice…”.7 When

he asked her to describe them, the unidentified woman

recited the following poem:

6 pp. 15-16

7 p. 16

4

“A people who have staked their aspirations onGod,

And whose ambitions aspire to nothing else.

The goal of this folk is their Lord and MasterO what a noble goal is theirs, for the One beyond

compare!

They do not compete for the world and its honors,Whether it be for food, luxury or children.

Nor for fine and costly clothesNor for the ease and comfort that is found in

towns.

Instead, they hasten toward the promise of anexalted station,

Knowing that each step brings them closer to thefarthest horizon

They are the hostages of washes and gulliesAnd you will find them gathered on mountain-

tops.”8

Cornell points out that despite the literary quality of

the poem and the level of Sufi knowledge it reflects,

Kalābādhī did not include the name of the woman who had

so thoroughly impressed Dhū an-Nur al-Misrī. This

“veiling of women’s voices,” states Cornell, “is

typical of al-Kalābādhī’s approach to Sufi history,”

noting that, “the only Sufi woman cited by name in Kitāb8 pp. 15-16

5

at-ta’ affuf is Rābi’a al-‘Adawiyya (d.185/801), and even

then she is named as a rhetorical device rather than as

a real person.”9 Cornell asserts that, in Kalābādhī’s

opinion, “most women are deficient in their knowledge

and practice of Islam” and, as such, “they cannot speak

authoritatively for either Islam or Sufism.”10 He

sites the prohibition of praying and fasting during

menstruation as the cause of their religious deficiency

and states, “Anyone who is deficient in religion is

deficient in faith.”11 Cornell uses al-Kalābādhī’s

opinion and exclusion of women’s voices as an “example

of male authorities on Sufism during the Middle Period”

who “hid the teachings and even the existence of Sufi

women behind a veil of obscurity…”12 Cornell argues

that their inclusion of Rābi’a al ‘Adawiyya “serves as

9 p. 17

10 ibid.

11 ibid.

12 ibid.

6

an exception to the norm of female inadequacy.”13 It

is this “continued mistrust of women and their

spirituality among many Sufis” that ‘is a major reason

why As-Sulamī’s book of Sufi women is so important to

the study of both Sufism and Islam today.” 14

Cornell’s Introduction consists of a broad

landscape of biographical information about as-Sulamī,

the time in which he lived, the tabaqāt genre and as-

Sulamī’s major works. He was born of the Banu-Sulaym

tribe in the Persian city of Nishapur in an eastern

region of Persia that is present day Turkmenistan,

Uzbekistan and Afghanistan. His father was al-Husayn

ibn Muhammad al-Azdī, an ascetic of tariq – al-malāma, the

Sufi “path of blame,” who was trained by the leader of

the malāmatiyya in Nishapur.15 As-Sulamī lived most of

his life in the 4th/10th century, a time Cornell

13 ibid.

14 p. 19

15 p. 31

7

describes as “a period of political, religious and

intellectual ferment.”16 Referring to it as “this

Shi’ite century”, Cornell describes it as having

witnessed at least three competing caliphs claiming the

right to authority over Islam.17 “Less than ten years

before as-Sulamī’s birth, ‘Abd ar-Rahman III18

proclaimed himself Caliph in Cordoba, Spain. The

Fatamid Caliph, ‘Ubayd Allah proclaimed himself the

Mahdī and governed from al-Mahdiyya for 60 years in

what is present day Tunisia. The Fatamid Caliphat was

then moved to Cairo, where the mosque-university of al-

Azhar, “was created as the intellectual center of the

Ismā’ili Shi’ism. The third Caliphate was that of the

‘Abbasids, who defeated the Umayyad Caliphs in

137/750.”19

16 p.21

17 ibid.

18 ibid. The Umayyads of Spain were Sunni Muslims following the Maliki School of Law. 19 p. 22

8

As-Sulamī is known for his important systemization

of Sufi doctrine, but is not as well regarded as his

immediate predecessors or successors, or his student,

Abū al-Qāsim al Quhayri (d. 465/1072-3).20

Nevertheless, his efforts to systemize Sufi doctrines

took the form of bringing Sufism into agreement with

the Sunnah of the Prophet as defined by the methodology

of ‘usul’.21 Cornell divides his work into three types:

1) sacred biographies or works on the lives and

teachings of famous Sufis; 2) treatises on Sufi

institutions and practices; 3) commentaries on the

Qur’an.22 As- Sulamī wrote Dhikr an-niswa al-muta ‘abbidat as

sūfiyyāt as a supplement to his famous Ṭabaqāt aṣ-sūfiyya

(Generations of Sufis).23 Cornell adds, “ Most scholars

believe that Ṭabaqāt aṣ-sūfiyya was itself an abridgement

of a much larger work entitled, Ta’rikh aṣ-sūfiyya (History20 p. 37

21 pp. 37-8

22 p. 38

23 p. 399

of the Sufis), which has been lost. It is said to have

contained one thousand biographical entries.”24 By the

time of his death in 412/1041, as-Sulamī had written

nearly seven hundred works on Sufism.25 Cornell asserts

that in his treatises on Sufi practices and

institutions, as-Sulamī was more concerned with ‘amal’

than with ‘ilm and notes that all of as-Sulamī’s

biographical works contributed to the “program of

uṣūlization” by tracing the origins of Sufi practices

to examples set by the Prophet, the Companions, and

other major first century Islamic personalities.26 The

most extensive work as-Sulamī produced other than Ta’rikh

aṣ-ṣūfiyya is his exegesis of the Qur’an, Ḥaqa’iq at-tafsir

(Realities of Exigesis).27 Because as-Sulamī frequently

cites Ja’far as Ṣadiq (d.148/765), the sixth Shi’ite

24 ibid.

25 p. 38 26 op.cit.

27 p.42

10

Imam who is the source of traditions of the Ismā’ili

Shi’a, his tafsir was harshly criticized by ibn Taymiyya

and other Hanbali scholars.28

It is important to look at the sacred biography

genre as a prelude to the discussion of as-Sulamī’s

Dhikr an-niswa al-muta ‘abiddāt as ṣūfiyyāt. Tabaqāt literature is

one of the oldest styles of Muslim historical

writing.29 According to Cornell, “The tabaqāt genre

originated as part of the field of hadith criticism and

arose out of the need to assess the backgrounds of the

hadith transmitters and the bearers of the

tradition.”30 This origin resulted in tabaqāt literature

following a hadith-style format and employing hadith

type chains of authority (sing. isnad).31 Cornell points

out that as-Sulamī was not the first Sufi author to use

the tabaqāt genre, which had become common by his time28 ibid. 29 p. 49

30 p.49-50

31 p. 4911

and allowed him to rely on written sources in lieu of

the oral tradition.32 The earliest writers of tabaqāt

works grouped the rijal al-‘ilm into three chronological

categories known as “The Righteous Predecessors (as-Salaf

as-Sālih), the Companions of the Prophet (as-Saḥaba) and the

Followers of the Followers (Tābi’at-Tābi’īn).33 Later, works

were organized by region and chronology and expanded to

include contemporary scholars and pious individuals.

Cornell asserts that this expanded form constitutes

“the model for Sufi sacred biography,”34 and identifies

at-Tabaqāt al-Kubrā (The Greatest Generations) by Muhammad

ibn Sa’d (d.230/845) as the likely prototype for the

first Sufi tabaqāt works.35 The only tabaqāt work that

as-Sulamī cites by name is Tabaqāt an-nussāk (Categories

of the Ascetics) by Abū Sa’id ibn al-A’rabi (d.341-952-

3), the Imam of the Sacred Mosque in Mecca, who was a

32 33 ibid.

34 ibid.

35 p.5012

respected Sufi master and one of the most significant

authorities to be cited in as-Sulamī’s book of Sufi

women.36 Returning to a discussion of the utilization

of chains of authority in the tabaqāt genre, Cornell

notes that, “’for as-Sulamī,….the chain of authority

acted in a way that was analogous to the modern

footnote”37 and says that the ‘footnoting’ as-Sulamī

employs by citing chains of authoritative evidence is

particularly significant for his book of Sufi women,

which contradicts cultural expectations and attitudes

regarding women.38 Expanding upon Sulamī’s

consciousness of the way women had traditionally been

portrayed if mentioned at all, Cornell notes, “

Although his book on Sufi women is not, strictly

speaking, a hagiography and as-Sulamī seldom portrays

his subjects as miracle workers, he does attempt to

36 p. 53

37 p. 50

38 ibid.

13

demonstrate that Sufi women possess levels of intellect

(‘aql) and wisdom (hikma) that are equivalent to those of

Sufi men.39

Cornell describes the discovery of the manuscript:

“In 1991, Maḥmud Muhammad al-Ṭanāhai came across this

long-lost work in a collection of treatises by as-

Sulamī in the library of Muhammad ibn Saud Islamic

University in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. It may be the

oldest as-Sulamī manuscript in existence and is a rare

eleventh century example of Arabic calligraphy.”40

Cornell notes three failures in at-Ṭanāhi’s

introduction and footnotes to the Arabic edition:41

1. There are several transcription errorsincluding missingportions of text.

2. Neither his introduction nor his footnotescontextualize as-Sulamī’s book of Sufiwomen as part of either Sufism or Sufiliterature.

39 ibid. 40 p. 44

41 p. 45

14

3. His unfamiliarity with the Sufi traditionof sacred biography resulted in hismisunderstanding or overlooking importantaspects of the text, for example,dismissing reference to Fātima of Nishapuras “ustadt” (male teacher) as a “linguisticanomaly” and missing the significance ofas-Sulamī’s gendered technical terms.

In addition to the recovery of the manuscript, the

Chapter entitled,”As-Salami’s Book of Sufi Women”

contains a sub chapter in which Cornell discusses the

organization of as-Salamī’s text.42 First explaining

that the eighty-two entries on Sufi woman are more

collages than biographies, Cornell states that as-

Sulamī organizes his portraits in regional clusters,

rather than in strictly chronological groupings.

Chronologically, the order of the regional cluster is:

Basra and Syria, Baghdad, 2) Damaghan and Egypt, and 3)

Nishapur and Khurasan.43

The most significant portion of Cornell’s

Introduction occurs in the chapter entitled, “As-42 p. 47

43 p,48

15

Sulamī’’s View of Women’s Sufism”. In the sub chapter,

“A Theology of Servitude,” Cornell identifies the most

prominent theme in as-Sulamī’s book of Sufi women as

servitude.44

“In fact, servitude is so central to as-Sulamī’sunderstanding of women’s spirituality that heenshrines the concept in the title of his work:Dhikr an-niswa al-muta ‘abbidāt aṣ-ṣūfiyyāt. This title tellsthe reader that as-Sulamī’s subjects are adistinct group of women (designated by thecollective term niswa) who are to be included amongthe Sufis because they practice ta’abbud, literally,making oneself a slave (‘abd) – the disciplinedpractice of servitude. For as-Sulamī, ta’abbud isthe essence of women’s Sufism. For Sufi women, itis their means of divine inspiration and thespiritual method that distinguishes them fromtheir male colleagues.” 45

Cornell points out that the Arabic term for worship (‘ibāda)

that applies to all Muslims regardless of gender, Sufi or

not, means “servitude”.46 Cornell argues that for as-

Sulamī, “the spiritual path of servitude freed Sufi women

from the constraints imposed on them by their physical44 p. 54

45 ibid.

46 ibid.

16

natures.”47 Cornell refers to them as “career women of the

spirit,” who, as slaves of God, have separated themselves

from women who did not share “the same spiritual

vocation.”48 The practice of servitude works on both the

outward and inward natures of a person simultaneously.

“Outwardly, it cultivates the Sufi attribute of scrupulous

abstinence (wara’), patience (ṣabr), poverty (faqr), and

humility (tawādu). Inwardly, the practice of servitude

cultivates the attributes of fear (khawf), worshipfulness

(‘’ibāda), gratitude (shukr) and reliance on God (tawwakul). These

are the attributes that lead to perfection in religion

(iḥsan).49

Cornell notes that as-Sulamī uses the masculine term

ustadt when referring to the teaching roles of Sufi women,

revealing their transcendence of the social limitations of

47 p, 57

48 ibid.

49 ibid. (prophetic hadith: Ihsan: To worship God as if you see Him, for if you see him not, surely He is seeing you).

17

their gender at the time.50 She contrasts this with Sufyan

ath-Thwarī’s reference to Rābi’a al-‘Adawiyya as a mu’adiba

because “an ustadt was a specialist in matters of Islamic

doctrine and the formal Islamic sciences.”51 Cornell

compares this kind of knowledge with that of the mu’addib,

which was of a practical nature and involved personal

training. Since Rābi’a al-Adawiyya did not receive her

knowledge through formal education, she was referred to as

“mu’addiba,” a term that reflects her gender.52 By referring

to Fatima of Nishapur and Hukyma of Damascus as ustadt, as-

Sulumī informs us that these women were formally educated

masters of both practice and doctrine, and were, “equal in

knowledge to the male Sufi masters with whom they

interacted.”53

Within the sub chapter entitled, “Institutions of

50 p.59

51 ibid.

52 ibid.

53 p. 60

18

Women’s Sufism”, Cornell reveals that as-Sulamī’s portraits

of Sufi women are arranged regionally and that Basra was the

site of more than one school of women’s asceticism.54 She

explains that many female ascetics flourished in Basra and

the surrounding regions during the late Umayyad and early

‘Abbasid periods (between 700 C.E. and 800 C.E.,55 noting,

“Many of these women were from non-Arab families that had

recently converted to Islam and were bound to Arab tribes by

formal ties of servitude (muwālat).” 56 Rābi’a al-Adawiyya,

who Cornell notes was possibly a convert to Islam, was a

client (maula) of Arab patrons of the tribe of Banū ‘Adī.

Cornell adds that, although she was the most prominent, “she

was by no means the earliest of them. Although Rābi’a has

often been identified as the first Sufi woman, as-Sulamī’s

text, read in conjunction with that of Ibn al-Jawzī, reveals

that she represented the culmination, and not the beginning

54 p.60

55 ibid.

56 ibid.

19

of the Basran tradition of women’s spirituality.” As-

Sulamī provides a portrait of Rābi’a at the beginning of his

book in keeping with his view of her as the quintessential

Sufi woman and so significant to the paradigm of female

spirituality he wanted to convey. But Cornell observes that

he, “uncritically assigned most of the other Sufi women of

Basra to Rābi’a’s generation, ignoring the fact that many of

them actually preceded her.”57 Cornell identifies the first

school of female asceticism in Basra as having been founded

by Mu’adha al-‘Aawiyya, “who was neither a contemporary nor

a ‘close companion’ of Rābi’a al-‘Adawiyya as as-Sulamī

claims, but actually lived a hundred years before her.58 In

actuality, Mu’ādha al-‘Adawiyya, “was responsible for

founding the way of disciplined servitude that epitomizes

as-Sulamī’s view of women’s Sufism. Her spiritual method

was highly ascetic and stressed prayer, fasting and the

performance of night vigils. Reliance on God was also a

57 ibid.58 p.61

20

central part of her doctrine.59 Two of the women in As-

Sulamī’s book of Sufi women were described as either

Mu’ādha’s disciple or student, giving credence to Mu’ādha’s

circle of female ascetics constituting a school.60 Cornell

refers to several women ascetics from Basra who lived

between Mu’ādha and Rābi’a al-‘Adawiyya who may have headed

other schools. One was Shabaka, who required her disciples

to perform their devotions in underground cells.61 Another

was Hafsa bint Sīrin, who was known for her tafsir of Quran,

for having a lamp that continued to give light even after it

ran out of oil and for lecturing in front of young men

(shabāb).62 Cornell argues that as-Sulamī has conflated,

“the asceticism and devotion to certitude that characterized

the school of Mu’ādha al-‘Adawiyya, the divine grace and

intellectual skills that characterized Hafsa bint Sīrin” in

his portrait of Rābi’a al-‘Adawiyya.59 ibid.

60 ibid.

61 p. 62

62 ibid. 21

From a chronological perspective, Cornell identifies

the next significant group of Sufi women as being from

Syria. According to Cornell, as-Sulamī’s source of

information about Syrian Sufi women was Ahmad ibn Abi al-

Ḥawārī (d. 230/845), the husband of Rābi’a bin Ismā’il of

Damascus, “a woman who was so similar in her spirituality to

Rābi’a al-‘Adawiyya that the two have often been mistaken

for one another by later authors of sacred biography.”63

Rābi’a bint Ismā’il was the disciple of Hukayma of Damascus,

the only Sufi woman other than Fātima of Nishapur to be

called ustadt by As-Sulamī.64 Cornell argues that as-Sulamī’s

portraits of the Sufi women of Syria, “are clearly meant to

contradict the notion that women are deficient in religion

and intellect.” These terms are specifically mentioned in

his portraits of the sisters of al-Dāranī, ‘Abda and Amina,

who As-Sulamī describes as having, “attained an exalted

level of intellect (‘aql) and religious observance (din).65

63 p.63

64 ibid.

65 ibid.22

Other portraits reflect, ”an intellectual approach to the

Sufi way,”66 in which as-Sulamī highlights Lubāba al-Muta

‘Abbida of Jerusalem, a specialist in fiqh al-‘ibbāddat. Cornell

writes that, according to As-Sulāmi, “love for God

(maḥabba), intimacy with God (uns) and fear of God (khauf) were

the main doctrinal elements of Syrian women’s Sufism.67 Two

interesting distinctions existed between the Sufi women of

Syria and those of Basra, according to Cornell. “The women

of Syria were known for spiritual practices that have

commonly been associated with early Christian ascetics” and,

“in terms of social class, they were more like to have been

of free Arab origin than the Sufi women of Basra, and at

least three of them –

Athama, Hukayma of Damascus and Rābi’a bint Ismāi’l – were

independently wealthy.”68 Cornell notes that philanthropy

was an important aspect of their practice, “as it had been

66 ibid.

67 p. 64

68 Ibid.

23

for wealthy Christian women before them.69 She identifies

the practice of Syrian Sufi women that is most suggestive of

Christian practice as that of an unrelated male and female

living together in a spiritual union that is free from

sexual relations. Such a relationship was attributed to

Rābi’a bint Ismā’il and her husband.70

Cornell notes an important shift that occurs in as-

Sulamī’ portraits of Sufi women who flourished after the

second half of the ninth century C.E., i.e., previously,

Sufi women were the disciples of other Sufi women.71 She

argues that in the two major centers of women’s Sufism,

i.e., Baghdad and Khurasan, during the hundred and fifty

years that preceded as-Sulamī’s time, “Sufi women mixed

freely with men, traveled long distances in order to study

and occupied positions of authority and respect among their

male Sufi colleagues, but they did not appear to have been

69 Ibid.

70 p. 65

71 Ibid.

24

spiritual masters themselves.”72 Cornell asserts that this

absence from positions of spiritual leadership is indicative

of a demotion in their social status. Nevertheless, Cornell

identifies the creation of a female ethic of chivalry as the

most significant development in the later period.73

Providing a grammatical explanation of the ways in which

‘niswa’ the dimunitive form of ‘nisa’, can be used as an

expression of endearment, enhancement or even contempt,

Cornell argues that as-Sulamī uses it to signify dual

enhancements.74 The first signifies women who are

distinguished by their vocation of servitude; the second

signifies the practitioners of female chivalry.75 Cornell

notes that a distinctive form of chivalry appears to have

been acknowledge by Sufi masters at least a century before

as-Sulamī. There were also women who are not described as

niswan, but as fityān ,i.e., female practitioners of male72 Ibid.73 Ibid.

74 Ibid

75 page 66

25

chivalry. Cornell explains that, “These women earned this

paradoxical designation by making a formal vow (muta’ahhida)

to serve male fityān.”76 She identifies both Fāṭima al-

Khānaqahiyya and Amina al-Marjiyya as women who served

organized groups of fityān, either as part of a female

auxiliary or individually, and asserts that As-Sulamī’s book

includes numerous examples of women who were the personal

servants (khādimāt)77 of Sufi shuyūkh.78

Cornell’s Introduction ends with an even greater

paradox. After asserting that as-Sulamī demonstrated that,

“women were fully the equals of men in their intellect and

religion, and could be full partners with men in most

aspects of religious and intellectual life,”79 and “after

unveiling no less than eighty Sufi women before the world at

large, he uses one of the last traditions in his book to

76 Ibid. 77 page 67

78 Ibid.

79 p.70

26

reestablish the sense of the mysterious by stressing the

inwardness of women’s spirituality: ‘I was informed that a

professional invoker said to ‘Āisha bint Aḥmad of Merv: “Do

this and that and an unveiling of divine secrets will be

granted to you.” She said, ‘Concealment is more appropriate

for women than unveiling, for women are not to be

exposed.”80

This book is a treasure trove of information and

insight into the lives of Sufi women, the scholar who

honored them, the genre in which he presented them, and the

times in which he and they lived. Rkia Cornell’s scholarly,

beautifully written Introduction, (e.g., “ Like the scent of

perfume in an abandoned place, as-Sulamiī’s book of Sufi

women has left its traces in Islamic sacred biography since

it was first written around the turn of the eleventh century

C.E.)81 should be required reading for any course on Sufism,

women’s spirituality, or Islamic literature. It has been

80 Ibid.

81 p.43.

27

one of the most enjoyable, revelatory and validating books

this writer has read in the past two years at the Hartford

Seminary.82

A note about appendices: The book itself contains an

Appendix consisting of ‘Entries on As-Sulamiī’s Early Sufi

Women Found in Ṣifat Aṣ-Ṣafwa by ibn al-Jawzī (d. 597/1201).

This review article contains an Appendix consisting of the

Chapters in “Dhikr an-niswa al-muta ‘abidat aṣ-ṣūfiyyāt, under which

this author has extracted and included a quote attributed to

the women profiled therein, whenever possible.

82 The other one is, Speaking in God’s Name:Islamic Law, Authority and Women by Khaled Abou El Fadl.

28