DON LANE - BRAZILIAN CINEMA ALIEN - PRISONER - UOW ...

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of DON LANE - BRAZILIAN CINEMA ALIEN - PRISONER - UOW ...

Registered for posting as a Publication — Category B

incorporating television

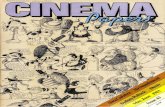

SPECIAL HOLIDAY ISSUE HARLEQUIN - DON LANE - BRAZILIAN CINEMA

ALIEN - PRISONER - LIFE OF BRIAN

D e c e m b e r - J a n u a r y 1 9 7 9 - 8 0

ithaefinitivep i v n e w

•answers to professional needsIntroducing the new Fujicolor Negative Film, crowning long y e a r s ^ M g i

of development by meeting today’s needs with tomorrow’s technology. W /

• Living, natural skin tones and greens. ! \• Ultrafine-grain high-definition images. v \• A reliable performer under difficult conditions. tW

Data: Fujicolor Negative Film 35mm type 8517,16 mm type 8527 JMf • Tungsten Type 3200K

• Exposure IndexTungsten Lamps 100 (ASA equiv.)Daylight 64 (ASA equiv.) (with Fuji Light Balancing

1 Filter LBA-12 or Kodak DaylightFilter No. 85)

• Perforation Types35mm N-4.740mm (BH-1866)16mm 1 R-7.605mm (1R-2994) and 2R-7.605mm (2R-2994)

• Packaging35mm 200ft (61m), Type 35P2 core 400ft (122m), Type 35P2 core

1000ft (305m), Type 35P2 core 16mm 100ft (30.5m), Camera spool for daylight loading

(B winding for single perforation film)200ft (61m), Camera spool for daylight loading (B winding for single perforation film)400ft (122m), Type 16P2 core (B winding for single perforation film)

122 m ¿100

H H A IM IM E X Industrial DivisionN A M E : ................................................................................................................................................... .

O ld P ittw a te r R d ., B rookvale, N .S .W . 2 1 0 0 . Ph: 9 3 8 -0 2 4 0 .2 8 2 N o rm a n b y R d., Port M elbourne, V IC , 3 2 0 7 . Ph: 6 4 -1 1 1 1 . A D D R E S S - 4 9 Angas S treet, A de la ide , S .A . 5 0 0 0 . Ph: 2 1 2 -3 6 0 1 .22 N o rth w o o d S t., Leederville , W .A ., 6 0 0 7 . Ph: 3 8 1 -4 6 2 2 .169 C am pbell S treet, H o b a rt, T A S , 7 0 0 0 . Ph: 3 4 -4 2 9 6 . .................................................................................. Postcode: .................................. Te leph one:

Please send me m ore in fo rm a tio n on D F u jic o lo r N egative F ilm

¡fc I will take a 1 □ 2 □ 3 □ year subscriptionPlease □ START □ RENEW my subscription with the next issue

Find cheque/money order enclosed for $made out to Cinema Papers Pty. Ltd.,

644 Victoria Street,North Melbourne,Victoria, Australia, 3051

The above listed offer is post free and applies to Australia only. For overseas rates see form inside back cover.Please allow up to four weeks for processing.Offer expires 31/3/1980

has joined 7 the ranks of the illustrious readers of

SUBSCRIBE NOW AND SAVE3 YEARS $40.50 (SAVE $4.50)

2 YEARS $30 1 YEAR $15

Delivered to your door FREE

Name....

Address

Postcode

Office Use only

NP OK ISSU E No.

¿& CL iO A tctLC f, âCCpt

a^ectiott...

Please send a special gift subscription for 6/12/18* issues of Cinema Papers

t o ........................................................................................................

Address.............................................................................................

.....................................................................Postcode......................

Please enclose a card from

Message

Please make your cheque or money order payable to:Cinema Papers Pty. Ltd.,644 Victoria St, North Melbourne,Victoria, 3051, Australia. ‘ Cross out whichever is inapplicable.See subscription form for current rates overleaf. For overseas rates see form inside back cover.

The New South Wales Film Corporation congratulates the makers of My Brilliant Career

Margaret Fink, producer Gill Armstrong, director

Don McAlpine, director of photography Eleanor Witcombe, screenplay writer Luciana Arrighi, production designer

Anna Senior, costume designer for their six awards, including Best Film,, in the 1979

Australian Film Awards.As major investors with GUO Film Distributors, creative and technical skills of Australian

we alsothankthe Australian National Catholic Film film-makers.Off ice for awarding “ My Brilliant Career’ ’ its t We are also proud to have been investors ininauguraltrophyfortheAustralianfeaturefiim “Tim”, which won three Australian Film Awards,which “ best promotes positive human values”. and “ Cathy’s Child” , which won the Best Actress

As official Australian entry in the 1979 Cannes Award.Film Festival, with high critical praise after its We thankthe producers, Michael Pate andscreening in the New York Film Festival this month Pom Oliver and Errol Sullivan, and the Australian and with major sales in North America and Europe, Film Commission for having given usthe “ My Brilliant Career’ ’ has proved internationally the opportunity to invest in ‘ Tim” and “ Cathy’s Child ’

~all Australians for backing Australian films

Communication without visualsis like putting on a play with all the actors

behind the curtains...For millions of people it is an

indispensable part of their daily lives. Whether at the cinema. On television. Or in their home projectors.

Agfa-Gevaert is a film pioneer. We grew up with it and we know its possibilities. We also know that while it may have matured

.. . and for your visuals by far the best and most flexible medium is film. Film is the medium capable of capturing a unique moment in time in all its richness and colour, In full action. In pulsating reality. Because whatever the eye can see, film can record.

But that’s not all.It can capture moments that exist only

in the imagination. Science fiction, mystery, fantasy, horror. Film has become one

it has not aged. Film will be as vibrant tomorrow as it is today.

All this, because communication without film just isn’t on.

AGFA-GEVAERT LIMITED Melbourne 878 8000. Sydney 8881444 Brisbane 391 6833. Adelaide 42 5703 Perth 361 5399

SYSTEMS FOR PHOTOGRAPHY • MOTION PICTURES • GRAPHIC ARTS • RADIOGRAPHY • VISUAL ARTS • REPROGRAPHY • MAGNETIC RECORDING

\

NOTICE to all applicants to the Project Development BranchCommencing from the month of October the following “ CLOSING D ATES” are advised for SCRIPT D EVELO PM EN T AND PRO JECT D EVELO PM EN T (Project Development was previously known as Pre-production). Because of the NEW ST Y L E PAN EL ASSESSM ENT for script development it is now necessary to restrict applications to a BI-M O N TH LY schedule. Applications will only be considered if they are lodged at the Commission’s office at 8 West Street, North Sydney, N.S.W., 2060 or the Commission’s Melbourne office at 409 King Street, Melbourne, Victoria, 3003 prior to 5.00 p.m. on the following dates: —

SCRIPT DEVELOPMENT4 January, 1980 (for consideration at the February Commission Meeting)7 March, 1980 (for consideration at the April Commission Meeting)9 May, 1980 (for consideration at the June Commission Meeting)

The below listed closing dates are advised for applications for PRODUCTION FUNDING (i.e. investment or loan applications). Applications will only be considered if they are lodged at the Commission’s office at 8 West Street, North Sydney, N.S.W., 2060 or the Commission’s Melbourne office at 409 King Street, Melbourne, Victoria, 3003 prior to 5.00 p.m. on the following dates : —

PRODUCTION FUNDING22 February, 1980 (for consideration at the March Commission Meeting)2$ April, 1980 (for consideration at the May Commission Meeting)20 June, 1980 (for consideration at the July Commission Meeting)

Further information may be obtained from the following officers of the Commission.

Sydney

(02) 922 6855

Melbourne

Shirley Wyndham (Script Development) Geof Gardiner (Production Funding)

Anne Pidcock (General Enquiries) John Daniell (Director of Projects)

(03) 328 2809 Murray Brown (Script Development & Production Funding)

When making an application to the Project Branch please read the ‘Requirements Check List9 on the back of the application forms.

And now for a special announcement

The Vincent Film Library’scontemporary and classic catalogue supplements

are available from:The Australian Film Institute,

81 Cardigan Street,Carlton South, Vic. 3053 Telephone: (03) 347 6888

A ll enquiries are welcome.

Now to complement a fine tradition in professional matching Marilyn and Ron Delaney proudly introduce a computer programmed system designed to update the entire

pre-matching procedure for documentaries, commercials, telemovies, specials, features, series and shorts. Negative Cutting Services Pty Limited is the service that

produces fast, clean and accurate professional matching every time and at a competitive price. NCS maintains the high standard that others have tried to copy with

little success. Some, even now, have similar sounding names to ours. Our service is fully accredited by the processing laboratories. In fact, at times the

laboratories are among our best customers.Select the matching service the major laboratories regularly use!

Call Marilyn or Ron Delaney on (02) 922-3607.

NEGATIVE CUTTING SERVICES 200 Pacific Highway, Crows Nest. N.S.W. 2065

HARDY*

HARDYS

HARDYS

H E R M IT A fif; C L A R E T w \IW A iight fed s me made fa®

E S « » '- HARDYS

O h i n m r ja b e r i'*

CABINET CLARET¿Pi '•« J-fe? i$i WciixinSieuis os <T ;

: :*;e<J. - S*«v>so«h. « W P Îfe S J £0's!:«iWii oa fc ç a i i j «nd boni« >9*® »

■W-. 'TîKJMaS MARIA A »*“ !jLt» l-VHEJ, VM.E ; s M I H Ü j i

' ?5i1P NKurïV^ 1Turn/. ^"ao py tt-t viA>.-ïRi v ,fp‘«OMAS HARDY & SONS PTY- W

■ Of 50UTH ÀÜSTftALtA f3* .

^^XiCE OF AÜSJRÀPA * T ® \

Hardy's reds weren't bom

yesterday.Before our red table wines see the light of day, they spend a full two

years in French oak casks. Down in the dark and cool of our cellars.

So that when you come to see them in your wine shop, you know they’ve

gained a fine balance of maturity, bouquet and flavour. Which means you can drink them as soon as you

like, or you can put them down and savour an even finer wine a

year or two from now.

I .A family tradition$ in fine winemaking

since 1853

HARDYS red wines area good part o f living.

Articles and Interview sBrian Trenchard Smith: Interview

Richard BrennanDon Lane’s Electronic Side-show

John Langer, John Goldlust Brazilian Cinema

Dasha Ross Ian Holmes: Interview

Liz Jacka, Ann Game Arthur Hiller: Interview

David Teitelbaum Community Television

Brian WalshJerzy Toeplitz: Interview

Peter Gerdes

598

604

608

612

618

622

630

The Don Lane Show Examined: 604 Features Brian Trenchard Smith

Interviewed: 598The Quarter 596Edinburgh International Film Festival 1979

Jan Dawson 616Adelaide International Film Festival 1979

Noel Purdon, Peter Page 626International Production Round-up

Terry Bourke 634Film Censorship Listings 635Production Survey 649Box-office Grosses 657

Production ReportHarlequin: Simon Wincer 638

Jane Scott 643Bernard Hides 646

Film ReviewsBrazilian Cinema

Surveyed: 608

AlienReviewed: 667

Life of BrianDennis Altman 659

Palm BeachNoel Purdon 660

Blood RelativesTom Ryan 660

Just Out of Reach, Morris Loves Jack, andConman Harry and The OthersBarbara Alysen 662

Rapunzel, Let Down Your HairMeaghan Morris 663

Escape from AlcatrazJack Clancy 665

AlienBrian McFarlane 667

Book ReviewsNo Bed of Roses, By Myself, and

Mommie DearestBrian McFarlane 669

Recent ReleasesMervyn R. Binns 671

Adelaide Film Festival Reviewed: 626

HarlequinProduction Report: 637

Managing editors: Peter Beilby, Scott Murray. Editorial Board: Peter Beiiby, Scott Murraiy. Contributing Editors: Antony I. Qinnane, Tom Ryan, Basil Gilbert, Ian Balllieu. Design and Layout: Keith Robertson, Andrew Pecze. Business Consultant: Robert Le Tet. Office Administration: Nimity James. Secretary: Lisa Matthews. London Correspondent: Jan Dawson.Advertising: Sue Adler, Sydney (02)31 1221; Peggy Nicholls, Melbourne (03)8201097 or (03)329 5983. Printing: Progress Press Pty Ltd, 2 Keys Rd, Moorabbln, 3189. Telephone: (03)95 9600. Typesetting: Affairs Computer Typesetting, 7-17 Geddes St, Mulgrave, 3170. Telephone: (03) 561 2111. Distributors: NSW, Vic., Qld., WA., SA. — Consolidated Press Pty Ltd, 168 Castlereagh St, Sydney, 2000. Telephone: (02) 2 0666. ACT, Tas. — Cinema Papers Pty Ltd. Britain — Motion Picture Bookshop, National Film Theatre, South Bank, London, SE1, 8XT.

‘ Recommenced price only.

Cinema Papers is produced with financial assistance from the Australian Film Commission. Articles represent the views of their authors and not necessarily those of the editors. While every care is taken with manuscripts and materials supplied for this magazine, neither the Editors nor the Publishers accept any liability for loss or damage which may arise. This magazine may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the permission of the copyright owner. Cinema Papers is published every two months by Cinema Papers Pty Ltd, Head Office, 644 Victoria St, North Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, 3051. Telephone (03) 329 5983.© Copyright Cinema Papers Pty Ltd, Number 24, December 1979-January 1980.

Front cover: Robert Powell and Mark Spain in Simon Wincer’s Harlequin.

Cinema Papers, December-January — 595

AUSTRALIAN FILM AWARDS

- %

A national strike by television technicians disrupted the presentation of this year’s Australian Film Awards.

The Awards were to be telecast live from a specially-constructed set at the Hoyts Entertainment Centre in Sydney. The strike by technicians, however, forced the Nine Network to cancel the scheduled broadcast.

The strike also prevented the organizers from completing the construction of the set and videotaping the Awards for broadcast at a later date.

Following the strike, negotiations were held with commercial networks In an attempt to re-schedule the event, but a suitable time could not be arranged at short notice.

The Awards were later held at a luncheon at the Sebel Town House in Sydney.

Producer Margaret Fink accepts one of the seven Australian Film Awards for My Brilliant

Career.

Best Film of the Year: My Brilliant CareerBest Performance by an Actor in a Leading Role: Mel Gibson In TimBest Performance by an Actress in a Leading Role: Michele Fawdon in Cathy’s ChildBest Performance by an Actor in a Supporting Role: Alwyn Kurts in TimBest Performance by an Actress in a Supporting Role: Patricia Evison in TimBest Achievement in Directing: Gillian Armstrong for My Brilliant CareerBest Achievement in Cinematography: Don McAlpine for My Brilliant CareerBest Original Screenplay: Esben Storm for In Search of AnnaBest Screenplay Adapted from Other Material: Eleanor Wltcombe for My Brilliant Career, based on the novel by Miles FranklinBest Achievement in Film Editing: Tony Patterson and Clifford Hayes for Mad MaxBest Original Music Score: Brian May for Mad MaxBest Soundtrack: Gary Wilkins, Byron Kennedy, Roger Savage, Ned Dawson for Mad MaxBest Achievement in Art Direction: Luciana Arrighi for My Brilliant CareerBest Achievement in Costume Design: Anna Senior for My Brilliant CareerJury Awards Jury PrizeGeorge Miller and Byron Kennedy for Mad Max

Documentary CategoryBronze Award: Island Shunters (Tim Wool- mer)Honourable Mentions:I See I See (Mike Pearce)Margaret Barr (Ross R. Campbell)The Russians: People of the Cities (Arch Nicholson)Short Fiction Category Silver Award:Goodbye, Johnny Ray (Mike Harvey) Bronze Awards:Just Out of Reach (Linda Blagg)Morris Loves Jack (Sonia Hofmann)Experim ental Category Gold Award:Sydney Harbour Bridge (Paul Winkler)Silver Award:Bondi (Paul Winkler)Honourable Mention:Feyers (Dirk De Bruyn)Animation Category Honourable Mention:Letter to a Friend (Sonia Hofmann)Awards for Cinem atography Silver Award:Russell Boyd for Just Out of Reach Bronze Award:Dean Semler for The Russians: People of the CitiesRaymond Longford AwardProfessor Jerzy Toeplitz An Australian Film Institute Citation for a Significant Contribution to Australian Film- makingSpecial AwardAn Australian Film Institute award to Grant Page in recognition of his stunt achievements over the years, culminating in his work on Mad MaxOCIC /Australian AwardThe Australian National Catholic Film Office, a member of the Organisation Catholique Internationale du Cinema, has awarded its inaugural trophy for the Australian feature film which ‘best promotes positive human values’ to Gillian Armstrong’s My Brilliant Career

FIRST FILMS FOR CORPS

The first films to be backed by the recently-formed Queensland Film Corporation and the Western Australian Film Council will soon be finished.

Harlequin, the first film the West Australian Film Council has invested in, was shot in

Perth in September. Produced by Antony I. Ginnane for FG Film Productions, and directed by Simon Wincer, Harlequin is a contemporary version of the Rasputin story. The cast includes Broderick Crawford, David Hemmings, Robert Powell, and Carmen Duncan.

Harlequin has also been backed by the Australian Film Commission, Ace Theatres (Perth) and the Greater Union Organization.

Final Cut is the title of the first film to be supported by the Queensland Film Corporation. Originally conceived as a tele-feature, Final Cut was developed by producer Mike Williams into a "glossy thriller about a show- business tycoon who is suspected of making ‘snuff’ film s ” , set against spectacular Queensland locations.

The film is being directed by Ross Dimsey for Wilgard Productions, a company set up by Williams with Frank Gardiner, an ex-part- time commissioner of the AFC,

The QFC have put up half of the budget for Final Cut, and the balance has come from the AFC and private investors. It will be distributed by GUO.

The cast of Final Cut includes David Glen- dinning, Louis Brown, Jennifer Cluff, and Narelle Johnston. The crew are all Queenslanders.

(A production report on Harlequin appears on page 637 of this issue.)

QUESTIONS IN PARLIAMENT

On August 22, a number of questions were raised in the New South Wales parliament by Bruce McDonald, the member for Kirribllli, over the financing of The Journalist by the New South Wales Film Corporation.

The full text of McDonald’s questions, and the answers given by the Premier of NSW, Mr Neville Wran, have been reproduced below from Hansard:

McDonald: Did the Premier provide, through the New South Wales Film Corporation, approximately $200,000 for the making of the film The Journalist? Was this a grant or a loan? What was the basis of the Government’s financial arrangements with Michael Thornhill, a director of the corporation and director of the film The Journalist in relation to that film?

As the film has received consistently bad rev iew s in p ro fe s s io n a l f ilm magazines and as the distributors, Roadshow, have no definite plans to release it, will Mr Thornhill pick up the tab for his share of the loss In this extravagant exercise, or will it be the taxpayers who have to foot the bill.

Wran: I would not be certain how much was provided by the Film Corporation to

the producers and makers of the film The Journalist, of whom one was certainly Mr Michael Thornhill, a director of the Film Corporation. In due course I shall advise the honourable gentleman of the actual amount.

It is equally correct that so far the film has not enjoyed any great success either at the hands of the critics or at the box- office. The suggestion that Mr Thornhill, by virtue of his being a member of the Film Corporation, is disqualified from participating In any grants or assistance from the Film 'Corporation is entirely a misconceived concept. Mr Thornhill is a member of the Film Corporation because he is one of Australia's most distinguished film directors.

There is ample evidence of various film commissions and corporations in other States — and indeed of the Australian Film Commission — actually making grants or providing loans or funds in order that a member of the commission or corporation who is involved in the making of films can participate in their making.

I know that the minds of the opposition members in this Parliament are not concerned with constructive positive matters, such as that raised earlier by the honourable member for Maitland. There is a rumour that the honourable member Is making a run for the leadership.

Morris: There is nothing like trying on a new suit.

Wran: We on this side of the House thought the honourable member looked even more distinguished than usual. Because we know their minds do not run in terms of positive and constructive things, but rather down those narrow veins that find their way Into the gutters, this question asked by the Deputy Leader of the Opposition was anticipated.

We have taken out some details of similar occurrences in other film commissions and corporations, and I now provide the House and the honourable gentlemen with this information. Anthony Buckley, when he was a member of the Australian Film Commission, received funds from that commission for the production of Caddie and The Irishman. Both those films were a success. That was the good fortune of Australia, the Australian Film Commission and Mr Buckley.

As the late Sam Goldwyn said, only one film in seven will be a success. We all know that. It Is pointless and irrelevant to look at the ultimate success or failure of a film. Mr Graham Burke, when he was a member of the Australian Film Commission, received funds from the body for the films Eliza Fraser, High Rolling and The Last of the Knucklemen.

[Interruption]Wran: I know that the Deputy Leader of

the Opposition does not go to films except of a certain kind. Generally speaking, all those films were successful. Pat Lovell, a member of the Australian Film Commission, has received funds for a development package.

I refer now to the position in Victoria, which I remind the House has had a

Mike Thornhill, director of The Journalist, and a director of the New South Wales Film

Corporation.

596 — Cinema Papers, December-January

THE QUARTER

Liberal governm ent for some time. Honourable members opposite might take a leaf out of the Victorian Liberals’ book as they just scraped home by the skin of their teeth at the last elections.

The following people, members of the Victorian Film Corporation, received funds in the following manner: Natalie Miller for In Search of Anna, Fred Schepisi for The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith; Tim Burstall for Last of the Knucklemen; and Nigel Dick, consultant to Crawford Productions, for Young Ramsey and The Sullivans.

Let us not think there was anything strange about the fact that the New South Wales Film Corporation made funds available and was involved in The Journalist. Just let us think it strange that that is one of the new films in which our corporation has invested and has not been a success at the box-office.

The new Chief Commonwealth Censor, Janet Strickland.

NEW CHIEF CENSOR

The Federal Attorney-General, Senator Peter Durack, recently announced the appointment of Janet Strickland as the new Chief Commonwealth Film Censor.

Strickland, 38, a former Deputy Chief Censor and a foundation member of the Australian Broadcasting Tribunal, succeeds Dick Prowse who resigned last month.

Senator Durack said the position of Chief Commonwealth Film Censor “ required exceptional skills, first of all to be able to assess community attitudes and then to be able to take this into account when examining films.

“As the Film Censorship Board applied uniform classifications on behalf of the State Governments there was a need to interpret the views of the States in formulating censorship standards.”

The Attorney-General said Strickland had admirable qualifications for the position of Chief Film Censor. She held an Arts degree from the University of Sydney and an honours degree in Anthropology from the University of Witwatersrand in South Africa, and taught for several years before her appointment as a member of the Film Censorship Board in 1971.

In 1974, she was appointed Deputy Chief Censor, and acted as Chief Censor on several occasions until she was appointed to the Australian Broadcasting Tribunal in 1976. She resigned from the Tribunal earlier this year.

NEW ASSESSMENT PROCEDURES FOR AFC

Following widespread criticism from filmmakers, the Australian Film Commission has changed the procedures for assessing projects to receive development funds from its Projects Branch.

The Commission's assessments are now bi-monthly, and a special panel will meet applicants to discuss their projects.

According to Rea Francis, the AFC’s publicity officer, the panel comprises “ producers, directors, film journalists and/or marketing experts, writers, a senior project officer, the director of the Projects Branch, and a full-time commissioner.”

On completion of each meeting, the panel forms recommendations to present to the next Commission meeting.

This new method of assessment will not extend to production funding.

Applications for loans and/or investments from the Project Branch for production funding will continue to be assessed by the Commission and outside assessors without the participation of the applicants.

AFI BOARD ELECTED

Following the take-over of the National Film Theatre of Australia by the Australian Film Institute, an election was held to appoint a new board of directors.

The new members are:Ina Bertrand (a lecturer at La Trobe

University;John Flaus (a tutor in film at Caulfield In

stitute of Technology);Pat Gordon (a long-standing committee-

member of the NFTA, and a committee member of the Melbourne Film Festival);

Barry Jones (a member of Federal Parliament who has been actively Involved in the development of the Australian film industry, including the establishment of the Australian Film and Television School and Victorian Film Corporation);

Ian Macrae (a film director);Scott Murray (a filmmaker, and an editor

of Cinema Papers)-, andDavid Roe (head of marketing of the New

South Wales Film Corporation).Ina Bertrand, John Flaus, Barry Jones and

Ian Macrae were previously members of the board, while Scott Murray, Pat Gordon and David Roe are new appointments. The previous chairman of the AFI, Barry Jones, was re-elected to that position.

NEW PERSONNEL

The Minister for Home Affairs, Mr Bob Ellicott, has announced the appointment of Henry Crawford to the Australian Film Commission as a part-time commissioner. The other members are: David Block (a merchant banker), David Williams (a film distributor), and Patricia Lovell (a film producer).

Crawford is a successful television producer. He has worked with Crawford Productions, and was responsible for the award-winning series Against the Wind. He is working on a new series with writer/direc- tor David Stevens, based on Nevii Shute's A Town Like Alice.

The Victorian Film Corporation has recommended the appointment of writer and director, Ross Dimsey, to replace Jill Robb as Chief Executive Officer. Dimsey’s appointment has yet to be ratified by the Victorian Government’s Executive Council.

Since Robb’s resignation earlier this year, the VFC has virtually ground to a halt. Very few new productions have been funded.

Dimsey has made one feature film, Blue Fire Lady, and written two others, Fantasm, and Fantasm Comes Again. He is directing his second feature, Final Cut, for producer Mike Williams.

The director of the National Library’s Film Section, Ray Edmondson, and archive librarian Julie Harders, examine one of the

publications in the Leab collection.

LIBRARY ACQUIRES FILM LITERATURE

The National Library of Australia has acquired the extensive film literature collection of New York film lecturer, author and historian Dr Daniel Leab.

The collection, built over 20 years, comprises 3100 books on aspects of the American and international film industries; sets of 128 cinematic periodicals dating" from 1903; 2000 film stills; and eight shelf metres of scripts, catalogues, pamphlets and other film documentation.

The director of the National Library’s film section, Ray Edmondson, said the breadth of the collection gave it considerable value in Australia:

"There could be dozens of collections of comparable importance in the U.S., but there are none to our knowledge in Australia” , Edmondson said. “Added to the material we have already, it will give the National L ibrary Austra lia ’s largest holdings of film literature and documentation.”The books — 1200 of which are by or

about screen personalities — include 30 autographed by the personalities concerned. One of these bears the signatures of Thomas Edison, Mary Pickford, Cecil B. de Mille, Carl Laemmle, Adolf Zukor and 20 other film stars and producers.

Six hundred of the books deal with film histories in different countries, with more than 30 relating to Nazi cinema and the development of German silent film up to 1931. The German publications are regarded as important contemporary records.

Among the periodicals are substantial sets of four key American trade papers: Metro- Goldwyn-Mayer's in-house paper The Lion’s Roar and sets of two famous German program magazines, lllustrier Film Kurier and Film Buhne, which reproduced stills and the story-line of a popular film in each weekly issue.

Peter Faiman.

FAIMAN QUITS

Peter Faiman, the force behind the Nine Network's successful The Don Lane Show has resigned to set up a film production company in Sydney.

Faiman, the executive producer of the show since its inception five years ago, is leaving at a time when the program’s ratings are at an all-time low.

Faiman’s new company, however, has signed a deal with the Nine Network to develop and produce special variety, documentary, and drama projects.

"Although I will be based in Sydney, GTV-9 will still see a lot of me” , Faiman said. “ In the production of major television specials, there is nowhere else in the country with such a wealth of production talent, and such a history of success.”

(The Don Lane Show is the subject of an article in this issue on page 604.)

LITTLE BOY LITIGATION

Sydney producer-director Terry Bourke (Night of Fear, Inn of the Damned) has been given assent in the Supreme Court of New South Wales to further contest a screenplay copyright claim against the film Little Boy Lost.

Mr Justice Powell ruled that Bourke’s claim should be referred to the Equity Court, but at the same time lifted a six-week injunction against the film secured by Bourke in an initial hearing before Mr Justice Rath. Bourke sued the Little Boy Lost producer Alan Spires, the film’s production company John Powell Productions Pty Ltd, and the film’s Melbourne-based distributors, Film- ways Australia.

Bourke is claiming $6310 in unpaid monies for his work as writer-director of Little Boy Lost between April and December last year.

The film has had extensive release in Victoria and the New England Ranges of NSW, but will not be seen in other cities until December.

HOYTS TO BE DELISTED

One of Australia’s leading film exhibitors, Hoyts Theatres Ltd, will be delisted from the Stock Exchange.

At a shareholders’ meeting in Sydney in mid-October, 90 per cent of preferential shareholders voted to sell their shares for $2 million to 20th Century-Fox.

Fox, the U.S. parent company of Hoyts, already controls the subsidiary. It has 100

• per cent ownership of ordinary shares.The move to delist Hoyts has been

criticized by James Mitchell, the director of the Film and Television Production Association of Australia.

Mitchell claimed that two of the three distribution companies monopolizing the industry would now be private. He said the delisting would mean Hoyts could not be forced to issue box-office statistics, which would be to the detriment of Australian filmmakers.

He said his association had been lobbying the Australian Film Commission for three years to sponsor a change in the Bureau of Statistics so that box-office figures would be available to the industry.

Hoyts, however, denied that the delisting would affect the industry, and that there was no reason to suppose that the attitude of 20th Century-Fox to the Australian film Industry would change.

FVAA ESTABLISHED

A new professional group, Film and Video Association of Australia, was recently established in Victoria.

According to the president of the new association, Rob Copping, the main function of the FVAA is to "promote and maintain the highest professional standards within all sections of the film and television industries, and to unify and provide a forum for all its members.

“The Association has been initiated by technicians working within the industry Who acknowledge that expanded communication with television and videotape exponents is essential in order to keep pace with burgeoning technological developments, and who accept the need to concern themselves with the increasing demands upon individuals in their industries.”

There are 126 members in the new association grouped into 12 categories and represented by an expert in each field. These are:

Animation and Graphics — Maggie Ged- des and Ray Strong

Art Department, props and wardrobe — Ray Wilkinson, Jo Ford

Camera — Ernie Clarke, Bob Kohler Direction — Mai Bryning, Mike Browing Editing — Mike Reed, Evelyn Cronk Grips — Paul Holford Makeup and hairdressing — Joan Petch,

Marg ArchmanProducers (production house) — Rob

Copping, Andy WayProducers (independent) — Bruce Mc-

Naughton, Eric Lomas Production and continuity — Tony

Sprague, Robert KewleySound — Ned Dawson, Ian Jenkinson Lighting and electrics — so far unrepre

sented.

FEGA

The Melbourne branch of the Film Editors Guild of Australia has initiated a series of forums on aspects of the Australian film industry.

At the first of these, held in October, the marketing and distribution manager of the Victorian Film Corporation, Colin James, spoke on marketing in the Australian film industry.

For further information about FEGA, contact Tim Lewis (03) 699 6666.

ADDENDA AND CORRIGENDA

In the paragraph beginning “The lack of media . . . ” (bottom, middle column, p. 515), the sentence starting “The recommendations for funding . . . ” should read as follows, and not as printed:

The recommendations for funding the film industry and breaking up distribution and exhibition monopolies led to growing pressure from filmmakers which resulted in a Unesco seminar in 1968 on film and television training, and the film committee of the Australian Council for the Arts which recom m ended an A u s tra lia n Film Development Corporation, an Experimental Film Fund and a Film and Television School.

Cinema Papers, December-January — 597

Early Days

A bout the age of 12, one becomes aware that one’s father goes off for eight or 10 hours a day, and comes home at the end of the week with money in his pocket: this is called working for a living, and men have to do this when they grow up. I was wondering, as one does at tha,t age, what I was going to do when I grew up, when I suddenly realized I loved films. Presumably people got paid money for making films, so I decided to become a filmmaker.

My first film was called The Chase, which I made on 8 mm when I was 15. It was not a critical or financial success, and was about a lunatic escaping from the Broadmoor Institution for the Criminally Insane, and chasing me around the countryside with a 1918 bayonet, before disposing of me messily at the top of a quarry.

One unfortunate documentary filmmaker — I think it was Alan King — was asked by the school film society to give a lecture and look at a school product. When he saw my film he said, with great difficulty and courage, “Yes, that does have a feeling for locatiqns.” So, my career was obviously launched.

After that I was commissioned to make a film about the school (Wellington College, England) for prospective parents. They financed the 40-minute film, which I made on 8mm with a synchronized, tape- recorder soundtrack. I was 17 or 18 at the time, and the film put me on the path, because when I showed it to some people after I left school, they gave me the job of sweeping the cutting room floor, which is where I started to learn editing.

After that, I worked as,a camera assistant for Reflex films, who said I was the worst they had ever employed. I think I was kept on because I was rather entertaining in my ineptitude. Anyway, they gave me a wonderful reference and I took it with me to Australia where I became a film editor at Channel 10. This was in 1955 when I was turning 20.

Television

At Channel 10, I cut news and documentaries by day, and expressed an interest in doing the station’s promotions by night. I had always been interested in trailers, and when I went to the films, which during my teens was three times a week, I would always look at the “Coming

Attractions” , as they were called, for next week’s goodies. They were of particular interest if I had already seen the films, because it was intriguing to see what bits had been selected to entice the public.

Anyway, I volunteered to do some promos at Channel 10, and made 73 film trailers during the night shift.

Eventually, Channel 9 noticed my promotions, and Bruce Gyngell and Pat Condon asked me to become their promotions director. There I launched the last season of programs Bruce Gyngell did before he left to start the Channel 7 revolution. These programs were launched very aggressively, with lots of action cut to music, then a new style of promotion.

Channel 9 was also kind enough to give me a reel of my stuff to take away with me if ever I toured the world. When I finally did go overseas, I visited Japan, the U.S. and Canada, where I barged into every television station I could find. One person I met worked for the National Screen Service, the largest trailer-making company in the world; they have studios in H ollyw ood, New Y ork and London. He suggested I look up their London office. I did, and was engaged in 1958 as a junior writer-

producer of feature film trailers. At National Screen, I made 21 feature trailers.1

This took me through to 1970 when Clyde Packer asked me to come back to Channel 9 as network promotions director. Part of the deal was that I could make television specials, thereby taking the jump into production I had always wanted. So, back I came.

I produced promotions which involved an increasing number of special effects, and I did a lot of work with the newly-formed Video Tape Corporation. I even made the first color presentation to be shown to advertisers of the new season’s program. This was at the time the station was still running in black and white. Then came my first directing assignment, and they really dropped it on me. “This kid wants to direct,” they said. “Well, we’ll teach him a lesson.” So they gave me a thing called Noel en Aus- tralie (Christmas in Australia).

Channel 9 had a reciprocal deal with French television, whereby the French had provided them with some services and they now wanted something in return. So, their top interviewer — I think his name was Jacques Chapard — came across to do a one-hour special on how Christmas was celebrated in Aus-

598 — Cinema Papers, December-January

BrianTrenchard

Smith

Australia’s top action director, Brian Trenchard Smith, reflects on his career to this point, and the directions he might take

f in the future, in an amusing encounter * with producer Richard Brennan.

tralia — live, via satellite, in French, in color, and before Channel 9 had officially converted to color. Channel 9 did have some basic equipment, however, such as a converted rent-a-truck for the outside broadcast van.

The show was to happen on Christmas day at 8.45 a.m., when Father Christmas would be rowed ashore by the Manly lifesavers on the stroke of nine (midnight in France). We lost one of the three cameras at the 20th minute, and it was probably the most adrenalinpumping situation I have experienced. A true baptism by fire, and no doubt deserved by someone foolish enough to say he wanted to direct, and that he could speak French.

Moving into Film

After I had spent two very happy years working for Clyde — who, whatever anyone else feels about him, was very supportive of me — I decided that I was bigger and better than all this and formed my own company. I borrowed $16,000 and made a one-hour, color television special called The Stuntmen, which featured various local stuntmen,

particularly Bob Woodham, an extraordinary and talented man, and Grant Page, a former commando and trawler fisherman, who was a rope specialist.

The Stuntmen was a success. It sold to Channel 9 for its negative cost, and has made a few sales overseas. I have paid off the backers and made a little bit of money on top. Most importantly, however, it started the ball rolling.

The Stuntmen is one of the best documentaries I have done. It displayed a pretty good analysis of what stuntmen are about, and the techniques they use. I have, of course, recycled the basic concept in a four-part television series called Danger Freaks, which basically featured Grant’s work, and expanded the concept by going onto international locations to make it more saleable for the international market. This has proved to be the case, as 12 countries have bought it so far, and more are doing so.

I continued to make television specials, like The World of Rung Fu and Rung Fu Rillers, which was a 75-minute, dramatized documentary. Roadshow-Village then asked me if I would like to make a dramatized documentary feature on venereal disease called The Love

Epidemic. This I did for the princely sum of $33,000, excluding blow up to 35mm. It did okay for them, getting its money back and making a small profit.

What was the basis of the legal problem regarding some of the actors?

I’d rather not talk about it. To defend myself as accurately as I deserve — which the newspapers never bothered to do — would probably invite new legal problems from some disenchanted loser.

The Love E pidem ic was interesting, insofar as it taught me a great deal about venereal disease, and I always like to learn something out of each new film. While I am not inviting people to come to me as a diagnostician, I can tell you that I know a great deal about it now.

The Man From Hong Hong

By the stage I had finished The Love Epidemic, I had more or less packaged The Man From Hong Rong as a co-production between a consortium of Australian partners and Golden Harvest of Hong Kong.

Golden Harvest is Raymond Chow’s company, and Chow was the man who discovered Bruce Lee. I first met Raymond when I went to Hong Kong to do a television special on Bruce Lee called The World of Rung Fu. On an earlier trip, I happened to see some of Lee’s work and realized that if this man’s films were put on the American market they would go through the roof.

This was early summer, and Golden Harvest were planning to put a film out mid-summer. I decided to get in quick and raised $8000 to do a documentary. But on the day I arrived Lee died. It was a blow. Of course, it was a blow for him too, but particularly for me because I had committed my full resources to the documentary. The air fares were spent, the cameraman was hired and so was the equipment.

So, I made a tribute to Bruce, as opposed to a documentary about him, and that played quite well on Australian television, where it got its money back.

Anyway, th a t’s how I met Raymond Chow, and later we came to an arrangement on The Man From Hong Rong. But the film was thwart with all kinds of production dramas, and was really too big for

Cinema Papers, December-January — 599

BRIAN TRENCHARD SMITH

600 — Cinema Papers, December-January

it at a negative cost of $2 million, and they were prepared to put up the $200,000 advance for the U.S. rights. The film was sold in addition for $500,000 worth of minimum guarantees at Cannes before it was shown. It was, theoretically, already in profit.

How much did it cost?

A bout $550 ,000 . I t was originally costed at $450,000, but went $40,000 over when our

Inspector Bob Taylor (Roger Ward), of the Federal Narcotics Bureau, arrests drug carrier Win Chan (Hung Kane Po) at the base of Ayers Rock. TheMan From Hong Kong.

someone of my experience to handle. But I learnt a lot and walked away a wiser and more experienced man. It certainly stretched and improved me.

Why was the film so problematic?

Co-productions are always more difficult than straight productions, particularly when you and the investors are not of the same nationality. What we were trying to do with The Man From Hong Kong was make a film that would be viewed as a serious, action drama in Asia, and elsewhere as a spoof of the indestructible ‘hero’ of the James Bond, Charles Bronson, or Bruce Lee type: the indestructible pseudo-fascist superhero who causes an appalling amount of destruction in the course of propagating the cause of justice. He may get punched, kicked, stabbed or run over, but his bruises heal within seconds and he takes a deep breath before killing someone else.

In our film, he gets the bad guy in the end, but he wrecks most of Sydney in the process. I think Mike Harris, then at The Australian, referred to our hero as the “Kung Führer” , and I think that is an appropriate piece of imagery.

Anyway, the Kung Fuhrer, Jimmy Wang Yu, had already directed eight films, though on lower budgets than we had for Man From Hong Kong. He was less than happy that this raw kid (me) was getting so much money to make his

first film. There was a great clash of personalities, coupled with the inevitable mutual distrust that occurs in a co-production where both sides think the other is trying to rip them off. (There was also a person who at one stage tried to have me replaced, but he shall remain nameless.)

In the end, all of this was too much for me to handle. It was also my first taste of politics, as all my past productions had been totally controlled and owned by me; people did as I asked, whether they liked it or not. Here, there were all sorts of political animals trying to second- guess and make capital out of any mistakes I made, and some I didn’t.

There were times when one felt suicidal, and I must thank John Fraser of Greater Union (the official co-producer) for the nightly support he gave me at the rushes. He would have dinner with me afterwards and, while everyone else was telling me what I was doing wrong, he was telling me what I was doing right. He kept my confidence together, and this was very important.

In situations where there is an unhappy crew, a rebellious actor or interfering investors, it is very

. difficult for a director to keep going. He is out there fighting on the front line, and he doesn’t need to be hit by stones in the back.

Still, we fought our way through, and I made as good a film as I could under the circumstances. When Fox saw the film they valued

Chinese partners . decided there weren’t enough crashes and bangs in the car chase, and we duly wrecked a few more cars. Then we decided, very wisely as it turned out, to put a hit song on it. We were guaranteed a hit by Leeds Music through the group Jigsaw in London, and Leeds lived up to their word. Jigsaw was as good as we were told, and Sky High was a No. 1 hit in Britain, Japan, the U.S. and Australia, to name a few.

The film sold very well, and broke box-office records at the London Pavilion, taking the highest opening week since Midnight Cowboy six years earlier. We’ve had some difficulty collecting the money, but the film has been in profit for some time, and I received my first percentage cheque the other day. More is on the way.

One of the things that tickles me particularly about Hong Kong is that it is the all time box-office champion of Pakistan. I had read this in the papers, but one day I met the man responsible in Los Angeles. As it happened, he had been working at 20th Century-Fox, when he quit his jo b , sold everything and went back to Pakistan, from where he had come, to start his own distribution company. And the only film he had was mine. He had paid $8000 outright for it, which, if you can get in American dollars, is quite good money.

He sank everything he had into launching the film. Western films sometimes run a month at the most, but mine ran six months and out- grossed all the previous record holders: Cleopatra, Where Eagles Dare, and The Guns of Navarone. The Pakistanis loved it; went bananas over it. Then he rested it for two years before bringing it back on re-issue. It broke box- office records again, despite the fact it was against the first release of The Spy Who Loved Me, which it took to the cleaners.

i Rebecca Gilling and Jimmy Wang Yu (the “ Kung Fuhrer” ) in The Man From Hong Kong.

BRIAN TRENCHARD SMITH

I think I will do a film in Pakistan one day. It is quite an exciting country, and it’s good to know I have a friend there who believes in me.

The Movie Company

At the time I was trying to finance The Man From Hong Kong, I approached some people at Greater Union, which had helped bankroll The World of Kung Fu and Kung Fu Killers. As both films had received their money back, Greater Union suggested we set up a joint production company, each of us owning 50 per cent. And the two projects we agreed to do were The Man From Hong Kong and Danger Freaks.

After we did those, however, Greater Union had a change of policy; they felt it would be better to invest in films and not support an on-going company. While I was not overjoyed at the news, I understood their reason: namely, that they could more effectively spread their money throughout the industry. As a result, they were able to back people as diverse as Hal and Jim McElroy, Michael Pate and Pat Lovell. This, on reflection, was good for the industry.

Deathcheaters

After the collapse of The Movie Company, I had to look around for new partners. Fortunately, I managed to get the Australian Film Commission, Channel 9 and D. L. Taffner to put up some money to make a pilot for a television series that could be shown theatrically in Australia and sold to television outside; that was Deathcheaters.

We made the pilot fox $157,000, which was $7000 over budget — I had forgotten to put in the defer

ments. This time the film was valued by Disney for $750,000, and they said a studio would have paid more. That was quite gratifying, and it was Deathcheaters and Hong Kong that ultimately got me the Disney connection. What was disappointing was that Deathcheaters failed theatrically in Australia. It got lost in the Christmas shuffle of 1976/77.

We had planned a premiere night for the cast and crew, but Hoyts decided against it — they didn’t even put on any ice-cream girls, and no one had anything to drink. But I really can’t blame Hoyts because Christmas is a hectic time, and they had other priorities, such as the Entertainment Complex that had opened the same week.

My film was against such heavy- - weight product as a Bond film, Eliza Fraser, The Return of a Man Called Horse and The Pink Panther, and a $150,000 film is rather weak ammunition against that kind of line-up.

Where we did do tremendous business was at matinees, particularly at the Athenaeum in Melbourne. In its last week we took $12,000, an amazing figure under the circumstances. In all, we got $30,000 out of Australian theatrical. We had a pre-sale to Channel 9 for $50,000, and the money we actually got back from overseas sales was $40,000, so we picked up $120,000.

We are still chasing the difference, but there is no doubt the . film will be profitable as world television is yet to be sold. A sale has just been made in Japan for $20,000, and, if Japan sells, the whole of South-east Asia usually sells.

The Taffner Company, which is in charge of television distribution, has a considerable track record in selling to television, and I have faith that Deathcheaters will return more than the amount it owes the investors.

Keeping it Together

After Deathcheaters, I tried to float a project called The Siege of Sydney. Michael Cove wrote a good screenplay from a story I had written, but the film became uncommercial due to changing market trends. It was about a gang of CIA agents who were tossed out of their covert operations cover when the Carter administration decided to clean up the American image.

Now, what do people, who have been trained for 20 years in killing people, blowing things up, subverting democracies, and generally having a good fascist time, do? Can they collect the dole? I reasoned they would become criminals, because a great deal of their activity had been criminal.

I proposed the situation where a gang of former CIA agents pose as radical terrorists and attempt to extort $5 million in industrial diamonds from the state of New South Wales by seizing Pinchgut Island and planting an alleged nuclear device on it. They would deal with a Neville Wran-type figure, who would have been charismatically played by Jack1 Thompson. He would have won in the end, and so he should; I am a fan of Neville Wran.

All this I was going to do on the lavish budget of $450,000. I had an offer of $200,000 from CIC, but they then lost a bundle on a terrorist film called Black Sunday. Their opinion was that terrorists frightened people too much, so all of a sudden half of my investment package fell out.

So, nine months of work and expenditure, including an overseas trip, was wasted. “Such is life” , as Ned Kelly said before they hanged him. Such is life for the independent Australian film producer.

The Siege of Sydney situation

was an object lesson in market research; namely, I should have done some before investing so much time and energy in the project. If at all possible, one should engage in market research to determine whether a project is viable.

Another example of the need for market research is the case of a state film corporation, which shall remain nameless, which sent me a script and asked me to write some action scenes for it. At that stage, it was a terrorist film, with the Israeli-Palestinian Liberation Front situation involved. The Palestinians were the heroes, and the Israelis the bad guys.

I wrote back asking them whether they realized that there were strong Jewish holdings in most of the television stations around the world, and that the stations might not feel inclined to buy a film in which the “wrong” people were the heroes. My point was apparently taken, and the script was subsequently changed.

After Siege fell through, I kept body and soul together by making trailers. With a theatrically “soft” film like Deathcheaters behind me, I was not on the top of anyone’s list of directors to hire. Happily, Film Australia decided that I was the person they needed to do a much- delayed project called Hospitals Don’t Burn Down. It details what happens in the first 20 minutes of a fire in a multi-storey hospital in the middle of the night.

It was intended as a fire safety film, and when they asked me to do it I said it should be done as a horror show. If you want to impress people to be careful about fire, the best way is to show the consequences in most unpleasant terms, and, in particular, bereavement. If somebody dies, a lot of people are rather sad about it, particularly the nearest and dearest, and if you want to get that through to people, you show the' misery that bereavement causes.

Cinema Papers, December-January — 601

BRIAN TRENCHARD SMITH

So, in addition to the visual horrors, I had a scene where the senior sister (wonderfully played by Jeanie Drynan) finds that her lover has been burned to death while trying to save a child; she just breaks down and sobs. I knew the way to finish the film with impact was to hold the camera on her and let her sob; not let the audience off the hook.

Film Australia, in the shape of Peter Johnson, who is a delightful producer to work with, gave me a pretty free hand, and so did the Veteran Affairs Department, which provided a lot of help, not to mention the money. The film turned out quite nicely, and it has won six international awards, including the Golden Camera at the Chicago Film Festival, and the best documentary award at the Cork Film Festival. It also picked up a couple of Australian awards, including best c inem atog raphy (Ross Nichols). I am very pleased for Ross, who is a cameraman I look forward to working with again.

The film has sold more than 300 prints, which is more I believe than any Film Australia production has done. Also, I understand from Ray Atkinson (AFC London representative) that it has generated $12,000 worth of royalties in Britain, and is about to sweep through Europe. Pyramid Films of the U.S. has picked it up, and Film Australia should see substantial money from that.

It was a short film (24 minutes), and I didn’t receive the kudos that goes with making a feature. But It is a film of which I am intensely proud. It set out to do some good, and I think it has done some.

In England, for example, the head of the Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents said that it was the greatest fire safety film he had seen. That’s a nice compliment, and I know that it is doing its job.

Each of your features has led out of something you have previously done, but “Hospitals Don’t Burn Down” hasn’t as yet . . .

It is about to do so, insofar as the New South Wales Film Corporation wants to do a Panavision documentary about the next set of Blue Mountains bushfires. These fires are about the only disaster in the world you can actually predict. T hey shou ld b reak ou t a t Christmas, and if they do I will be asked to come back from the U.S. to do a documentary on them.

Jim McElroy is the producer. He is also trying to do a feature on the fires, and if my name is acceptable to the investors, and to the imported star, tfien I will direct it.

Stunt Rock

After The Man From Hong Kong, I felt I was falling slightly behind the other directors who had come along, so I decided to make a film which would launch Grant Page on the international market. Deathcheaters, to a certain extent, was meant to have done that, but didn’t. So, I created Stunt Rock and took it to the Dutch distributors who had bought Death- cheaters. They had told me to come to them with any bright and cheap ideas I had.

Together, we managed to finance a $450,000 film which was made in a non-union situation in Los Angeles. “Non-union” is a rather emotive term, but it is not as bad as it sounds. It just means that one is using people who are not in the number one union, or union members who are working out of their grade to get experience in some other department.

We shot the film in Hollywood and it has sold very well, though it

Scene from Hospitals Don’t Burn, which Trenchard-Smith directed for Film Australia.

is probably the worst film I have made. Such is life. All I can say to other filmmakers is never let yourself be pressured into making a deal, rather than a film, which is what happened to me. Again, it was a great learning experience. I jumped in the deep end and found I was not protected by the things that protect filmmakers in Australia.

People may bitch about the investors here and other problems, but there is a great deal of goodwill towards the film industry, and one is quite well protected. The political assassinations that befell me on The Man From Hong Kong were 10 times worse on Stunt Rock. The budget was nearly withdrawn several times due to fights within the investing company — nothing to do with me. In the international film scene, they think nothing of suddenly cutting off funds for no reason. What I should have done was be a man of greater courage and principle and said, “No, I will not do this. It’s either done my way or not at all.”

Anyway, the film got made, but it was a film that went from six- page treatment to stereo answer print in 4’/2 months. That is no way to make a feature and, when you see the film, you will see why.

It is an entertaining film, though, simply because my style is to keep things happening. As soon as something gets dull, tedious or unconvincing, I move on to something else, which in turn might

become dull, tedious, or unconvincing. But it moves like an express train, and in that respect it is value for money for the undertwenties. The over-twenties start to notice a slight lack of story, and a few other problems.

Such as the music . . .

Well, that is a good point since the music was an essential 50 per cent of the commercial package. I was in the shower at the time the concept came to me. God, I think I should have stayed unwashed that day! Something clicked in my commercial mind which said, “Famous Australian stuntman meets famous

• rock group. They interrelate; much stunt and much rock takes place.Kids will tear up the seats.” Great idea in principle, but turning it into practicality proved impossible with too little money and too much interference.

Three weeks before we were scheduled to shoot, a famous rock group was still not signed. I had Foreigner interested, but they

' wanted to finish their world tour, and my investors wanted the film completed by a certain date. Exit Foreigner. At that time, I was also told the script had to be re-written to incorporate a Dutch actress to strengthen the Dutch market. This, and having to find a-rock group within four days, was-difficult. *

I went out and found Sorcery. Now Sorcery is visually very

602 — Cinema Papers, December-January

BRIAN TRENCHARD SMITH

Deep down, I know I was trying to prove I was courageous; that I had balls. But there was also the intellectual desire to study a stunt from the inside. I know now the precise angles from which to cover that stunt, and I think my hit-and- run car stuff is as good, if not better, than most you see on the screen.

Filming Action

Head stuntman, Grant Page, scrambles out of a burning car wreck. Stunt Rock.

exciting, but its music is frankly four year-old Led Zeppelin and doesn’t really provide what the young audience is looking for. In th a t respect, the film is a disappointment.

Time Warp

Happily, during shooting my agent rang me and asked me if I could direct a Walt Disney telefeature to be made in London. My Stunt Rock contract unfortunately overlapped that date, and I had to say, grinding my teeth, that I couldn’t do it. Disney asked me to see them anyway. They had gone to the trouble of seeing Hong Kong and Deathcheaters, and had decided I was a young talent worth exploring.

When I saw them they asked if I had any bright ideas, and I suggested this great science-fiction film I want to make called Time Warp. I gave them an eight-page outline, and they gave me a development contract. They had an option to cut me off at treatment stage, and then at screenplay stage. We have passed through those stages now, and they own the rights. I am contracted to direct the film and, if I don’t, they have to pay me a penalty fee.

The film is on the 1982 production schedule, with a budget of $20 million. But if The Black

Hole, their current science-fiction film, is not successful, though I believe it will be, they may be reluctant to initiate the same kind of expenditure for another science- fiction film, even though mine is not a deep space film.

Disney are relatively pleased with it at this stage, though they want to do certa in th ings with the characterization, probably to suit casting at the time.

Action

Many people regard your interest in action as a fixation. How do you respond to that charge?

It is an interesting point. At school, I was a 6ft and half inch devout coward. My sporting interests lay with fencing, which was considered to be the activity of fairies. A real macho guy was one who liked grabbing people round the balls on the rugger field, thereby proving his manhood. I think I suffered some slight physical inferiority complex as a result, and when I left school I had this affinity for physical action in films, if not in person.

I have always been interested in men of courage, and when I was at Channel 9 I made a one-hour special re-enacting the exploits of four Australian winners of the Victoria Cross in Vietnam. I

received some criticism for not having a left-wing point of view —i.e., for presenting these characters as heroes. But they were heroes: regardless of the moral turpitude of the war, the poor bastards had to do what they were told. Anyway, these men won their VCs for saving the lives of wounded people, not for killing hordes of the enemy.

I suppose stuntment have appealed to me because they put their lives on the line. Sure, they work out the variables, but there is still a risk. They are men of great courage, and they are paid proportionately little for the risks they take.

As a result of this fascination, I began to do stunts myself — not for use in film, but as publicity stunts. I have been set on, fire eight times, and knocked down by a car three times.

Roger Ward drove a car at me at 40km an hour in Perth, scooping me up on the bonnet and sending me rolling off to the side; that was for the opening of The Man From Hong Kong. I was also skittled in Soho Square by an obliging member of the film distribution office there, and that appeared all over m agazines in B rita in : “Director takes the plunge” — really imaginative copy.

. Anyway, three car knock-downs is enough. I went through the windshield of the one in Soho Square, and I stuck a photograph of it in my lavatory to remind me of my foolishness.

When you start an action sequence you are putting your foot down on the accelerator and hyping the pace. The succession of shots becomes quicker and quicker, and you employ explosive little climaxes. As a result, each image has to tell the audience the essential information very rapidly, and often quite close up in the frame. There is no point in filming a dramatic punch in wide-shot.

I am speaking in generalities, of course. Take for example a fight scene where person A throws a chair across a room at person B. You start with a wide shot of A picking up a chair and throwing it from one side of the frame. The moment the chair leaves character A on left, you cut to a wide-shot so you can see the chair fly across the screen. You then cut to a close-up of B ducking, with the chair passing over his head and shattering on the wall behind.

In short, you play the wide-shot when the audience has something that they can readily grasp: i.e., a chair flying from one side of the frame to the other. The impact then comes with the chair shattering in close-up.

This is one way of doing it, and there are many alternate ways. Every director does things differently, and I don’t always do things the same way.

Another important lesson is to dress your frame. In a battle scene, for instance, you must dress your background, foreground and middleground. For example, consider a mediaeval battle sequence. You might have in wide-shot the cavalry charging forward from the background, while men run from behind the camera into the foreground and proceed to meet the cavalry in the middleground. People in your background then start firing arrows, and a body is hit by an arrow, falling with a thud from above frame into immediate bottom frame close-up.

In this case, a way of initially engaging the audience’s attention is the activity in the background of the wide-shot. When they have had a couple of seconds to absorb that, and before they get tired and lose the sense of timing and momentum you have been building, people rush into the foreground and engage in battle in middleground. Then, just when that has used up the necessary

Concluded on P. 674

Cinema Papers, December-January — 603

ELECTRONICSIDE-SHOW

John Langer and John Goldlust

Since the early days of Australian television, the Nine Network has been producing a regular ‘live’ night-time talk/variety program. Graham Kennedy’s In Melbourne Tonight was the starting point, and since then there have been numerous changes in format and personnel. The Don Lane Show is the latest offering. A twice- weekly, 90-minute program compered by American Don Lane, the show has been proclaimed as the most successful venture to date.

The television industry and its publicity machine point to the program’s consistently high ratings, its ability to transcend localism to appeal to a national audience, its production values (primarily instituted by producer Peter Faiman) and its potential saleability in an overseas market as indicators of its achievements and popularity.

But the conventional wisdom, from which this praise emanates, tends to ignore, and even conceal, some of the program’s major motifs: its relationship to consumerism, salesmanship and advertising; its saturation with commodities; its incipient provincialism; and its overwhelming commitment to fostering the cult of the celebrity.

Author Raymond Williams points out that forms of television are the adaptations of earlier forms of cultural and social activity within new technological modes of presentation and reception.1 Cultural forms, such as the newspaper, novel, music hall, sports stadium, cinema, advertising columns and billboards, have their modern equivalents within the contemporary forms of television production. It is in this sense that The Don Lane Show can be described as an electronic side-show. More than any other cultural form, this kind of program seems to derive its structure and content from the ways in which the travelling medicine show or carnival side-show once functioned.

Like its predecessors, The Don Lane Show operates through the fluid and skilful interplay of salesmanship and spectacle which combine to create an evening’s entertainment. The program has its front men — Don Lane and his colorful side-kick, Bert Newton — who, like buskers standing in front of the side-show tent, excitedly regale the viewers/customers with anticipated delights and pleasures derived from the exotic or unusual exhibits and performances that await them.

During any particular week audiences might see Hugh Hefner’s playboy mansion, a million dollars worth of gold bars, a Paris fashion show, old and new Hollywood Film stars, tribal dancers

I. Television, Technology and Cultural Form, 1974

The opening patter between Don Lane and Bert Newton.

from the New Hebrides and even an at-home interview with that famous Australian television family, the Sullivans. Later in the show they are given the chance to participate, albeit vicariously, in one of the most recognizable of all sideshow institutions: the wheel of fortune.

In keeping with the side-show tradition, the opening segment of The Don Lane Show performs a crucial function. Similar to the patter and exhibits in front of the side-show tent, the first minutes of the program articulate its style and pace, hold out promises o f ‘things to come’, and establish the co-presence and personae of Don and Bert. Within seconds, several aural and visual elements are mixed together to create a sense of action and anticipation.

The viewer enters the program in the midst of tremendous applause, while the studio band plays an up-beat number. The camera reveals the band leader conducting his musicians as the applause continues in time to the music and the program’s logo is flashed onto the screen. This is followed by a shot of the audience facing the

The frontmen: Don Lane and Bert Newton.

stage, still applauding. In this way, the show as ‘live’ performance is marked visually.

Invariably, the next shots are of Bert standing at a microphone as he introduces the ‘host’, then of Don Lane sweeping out from behind closed curtains onto the stage. Apart from its obvious theatricality, this gesture sets into play one of the key structures of the,program: the dynamic between that which is concealed and that which is revealed.

Concealment is the promise of things to come; revelation is the fulfilment of that promise. At the outset it is the curtain which mediates the structure of presence and absence. Once Don appears, he takes control of his function by virtue of his role as principal host/compere/front man. He becomes the mediator who holds out the promises, opens up the absences and in turn shapes the process by which these absences are Filled. One of his major contributions as front man is to keep reiterating future occurrences — itemizing, enthusing over and ordering the spectacles to be seen.

During the first segment, he previews and hierarchially arranges the evening’s exhibits — those that are special, such as an exclusive satellite interview with an overseas celebrity, and those that are routine, like the performances of singers or the wheel. Throughout the program, before each commercial break, Don again describes what the audience can expect if it stays tuned. This constant reference to future happenings works on the one hand to keep the viewer interested in the entire show — there will always be something more that will have appeal — and on the other hand to allow entry into the program at any point without having missed anything.

The next shot is taken so that the viewers see Don’s back as he faces the studio audience. His Figure in the foreground is carefully framed by the proverbial sea of smiling faces as the audience looks at him looking at them. Awareness of the studio audience is marked from the start, but it is in this shot that an interactive link between performer and a live audience is made. This shot specifically signals the relationship that Don enters into with the studio audience. Consequently, what happens for their benefit also demands their participation and involvement. Just like the performers on stage they too must play their part. They are being entertained to be entertaining, and as a result they are implicated in the construction of the television event.

This shot also links the viewing/external audience with the live/internal audience. Through the internal audience the viewer is given a secure place from which to watch the program unfold. The responses and involvement of the studio audience set up the necessary cues for the external audience to participate in a live

Cinema Papers, December-January — 605

performance situation. In this sense, The Don Lane Show and its cast perform for two audiences simultaneously.

At this point the action on stage between the front men begins. Routinely Don starts with a joke or humorous personal anecdote, which just as routinely, judging from the studio audience response, fails to amuse. This serves as the cue for Bert to enter into a spontaneous, seemingly unscripted repartee with Don in which much of the humor derives from Bert’s irreverent comments on another of Don^s attempts to be funny.

Although this interchange is a brief one, it situates the relationship of the front men within a particular comic mode which is repeated whenever they are together on stage. What emerges from this verbal encounter is the fact that whereas Don may or may not have success in the comic arena, Bert nearly always does, and often as a result of Don’s failures. In this respect Don and Bert work within the comedy team tradition of the jester and his straight man.

In an important sense, Bert’s persona, manifested through his quick wit and satirical skills, represents a particular kind of Australian sensibility which may prove to be much of the show’s appeal for local audiences. Bert basically operates as a subversive, undermining element. Back-handed remarks about Don’s talents as an entertainer, tongue-in-cheek digs at product promotions, and outrageously unflattering impersonations of the evening’s major guest celebrity during the wheel segment are regular parts of his satirical repertoire. In this way Bert incorporates and personifies the stance of the ‘knocker’ — the ability to debunk and to remain publicly cynical — which has been developed as a characteristically Australian response to pretension, slickness, seriousness and self- importance, particularly if these are imported from overseas. This aspect of Bert’s persona has a direct historical link with the style of performance cultivated and nurtured through his lengthy apprenticeship with Graham Kennedy.

If Bert monopolizes the show’s humor, leaving Don with little for himself, Don appropriates the show’s glamour and sexuality. Just as Bert extracts comedy out of Don as a straight man, Don extracts glamour out of Bert as a funny but unsexual, unavailable male. Throughout the show, constant references are made by Don about Bert’s weight problems, loss of hair or the creeping domesticity of his married life.

The visual contrast in their physical stature helps to punctuate this difference. Bert’s appearance is one of shortness and roundness, stereotypically the ‘cuddly’ male as homebody (also the physical characteristics often associated with the comic), while Don’s is one of slenderness, a feature commonly packaged and presented to define the ‘sexy man’.

Don’s sexuality and eligibility culminate at the end of each show when he leaves the stage to give away a gold pendant on a chain to a female member of the studio audience, usually someone young and attractive.

The ritualized presentation of the gift further serves to distinguish the sexual from the comic domain. Using a technique which looks very similar to the way an embrace might be choreographed, Don faces the girl and carefully places his arms around her neck to join the clasp of the chain. He then gives her a kiss on the cheek. Although it is a distinctly innocent act, this kind of pseudo-sexual public behaviour is acceptable for the eligible bachelors that populate the world of television, but not for its married men.