Do regulable features of child-care homes affect children’s development?

Transcript of Do regulable features of child-care homes affect children’s development?

Early Childhood Research Quarterly 17 (2002) 52–86

Do regulable features of child-care homes affectchildren’s development?

K. Alison Clarke-Stewarta,∗, Deborah Lowe Vandellb, Margaret Burchinalc,Marion O’Brienc, Kathleen McCartneyd

a Psychology and Social Behavior, 3340 Social Ecology II, University of California-Irvine,Irvine, CA 92697-7085, USA

b University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI, USAc University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, USA

d Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA

Abstract

Data from the NICHD Study of Early Child Care were used to assess whether regulable features ofchild-care homes affect children’s development. Child-care homes selected were those in which therewere at least two children and the care provider received payment for child care (ns = 164 when thestudy children were 15 months old, 172 at 24 months, and 146 at 36 months). Caregivers who werebetter educated and had received more recent and higher levels of training provided richer learningenvironments and warmer and more sensitive caregiving. Caregivers who had more child-centered be-liefs about how to handle children also provided higher quality caregiving and more stimulating homes.In addition, when settings were in compliance with recommended age-weighted group size cut-offs,caregivers provided more positive caregiving. Quality of care was not related to caregivers’ age, expe-rience, professionalism, or mental health, or to the number of children enrolled in the child-care homeor whether the caregivers’ children were present. Children with more educated and trained caregiversperformed better on tests of cognitive and language development. Children who received higher qual-ity care, in homes that were more stimulating, with caregivers who were more attentive, responsive,and emotionally supportive, did better on tests of language and cognitive development and also wererated as being more cooperative. These findings make a case for regulating caregivers’ education andtraining and for requiring that child-care homes not exceed the recommended age-weighted group size.© 2002 Elsevier Science Inc. All rights reserved.

Keywords:Child care; Child-care homes; Caregivers

∗ Corresponding author.E-mail address:[email protected] (K.A. Clarke-Stewart).

0885-2006/02/$ – see front matter © 2002 Elsevier Science Inc. All rights reserved.PII: S0885-2006(02)00133-3

K.A. Clarke-Stewart et al. / Early Childhood Research Quarterly 17 (2002) 52–86 53

1. Introduction

Today, in the United States, the majority of infants and toddlers have mothers who workoutside the home, and the most common child-care arrangement for them, if dad or anotherrelative is not available, is care in a child-care home (National Center for Education Statistics,1998). Because this form of child care is so common, concern has been voiced about thequality of attention children receive in these settings (Kontos, Howes, Shinn, & Galinsky,1995). Child-care homes are enormously varied and largely invisible. They range from informaldrop-off sites in the neighborhood to organized facilities run by child-care professionals. Theymay be licensed or operate “underground,” provide care for one or two children or groups ofsix or more. The children in the home may be infants or toddlers or older children, includingschool-age children in the late afternoon; they may or may not include the care provider’s ownchildren. It is hard to know what goes on in these diverse settings. Media reports of neglect orabuse in some child-care homes (e.g., Healy, 1998; MacGregor, 1998) fuel efforts to regulatehome-based child care. But not only do we not know what goes on in these homes, we do notknow which features should be regulated, or if regulating them would improve the quality ofcare children receive.

In centers, the features of care that are most commonly regulated include the child–staffratio, group size, and teacher preparation. Regulating these features in center care makes sense,because research indicates that when center classes have fewer children, a better child–staffratio, and more educated teachers, children receive more positive caregiving and do betteron assessments of their behavior and development (Lamb, 1997; NICHD Early Child CareResearch Network, 1999b). Would regulating these same dimensions be likely to promotehigher quality care and better child outcomes in child-care homes, or are there other di-mensions of child-care home settings that outweigh the significance of these factors, suchas whether the caregiver’s own children are present or whether the caregiver suffers fromdepression?

In the present study, we used data from the NICHD Study of Early Child Care to considerthese issues. In particular, we posed three questions:

1. Do regulable features such as caregiver education and training and group size predict thequality of children’s experiences observed in child-care homes?

2. Do nonregulable factors such as caregivers’ beliefs predict the quality of care childrenexperiences in child-care homes or mediate the effects of regulable variables?

3. Do these regulable and nonregulable features and observed quality of care predictchildren’s cognitive and social development?

The data set provided by the NICHD Study of Early Child Care allowed us a unique oppor-tunity to address these questions. Data were collected at 10 research sites in nine states thatvaried widely in their regulation of child-care homes. Children were enrolled in the study atbirth, and were followed through their first 3 years, with observations in their primary child-carearrangements at 15, 24, and 36 months. Standardized cognitive and language assessments wereobtained at these same ages, along with mother and caregiver reports of children’s social skillsand behavior problems. Family factors associated with child-care features were also assessed.Thus, it was possible to examine the contributions of regulable features, nonregulable factors,

54 K.A. Clarke-Stewart et al. / Early Childhood Research Quarterly 17 (2002) 52–86

and observed quality of care to a broad array of child developmental outcomes measured atthree different ages, while controlling for selection factors like family income and maternaleducation. Analyses of this complexity and breadth have not been possible in previous stud-ies of child-care homes. In addition, because families were recruited at the child’s birth, thelikelihood that the sample was composed only of families who were satisfied with their carearrangements or who used licensed settings was reduced. Prior research has not included suchmethodological control. The NICHD Study has its limitations: the number of children whowere cared for in child-care homes was modest; the sample was not a nationally representativeone; and certain exclusion criteria were applied in recruiting the sample in the first place. Nev-ertheless, the strengths of the study make it an important source of information for answeringquestions about the quality of care in child-care homes.

In the study, we observed quality of care in two different ways. In previous work, researchershave defined child-care quality in terms of the caregiver’s behavior (e.g., Arnett, 1989), or interms of more global measures of the physical and social environment (e.g., Abbott-Shim &Sibley, 1987; Harms & Clifford, 1989)—or both (Kontos et al., 1995). In the current study,we followed both approaches. Ratings of caregivers’ behavior with individual children werebased on minute-to-minute observations of study children’s experiences. These ratings, whichincluded dimension such as the caregiver’s sensitivity and positive regard for the child, werebased on Ainsworth’s well-known ratings of maternal behavior (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, &Wall, 1978). A second measure of child-care quality was a more global assessment that includedaspects of both the physical and the social environment. The Child-care HOME (CC-HOME)was adapted from Caldwell and Bradley’s HOME inventory (Caldwell & Bradley, 1984), aninstrument that has been widely used to measure the quality of care provided by parents (e.g.,Bradley et al., 1989). The HOME was modified by Bradley and Caldwell for the NICHD Studyof Early Child Care to assess the quality of home child care.

1.1. Regulable features and the quality of care

The first question on which the present study was based was whether regulable featuresof child-care homes predict the observed quality of care in terms of both caregivers’ behav-ior and overall quality assessed with the CC-HOME. Based on research conducted over thepast two decades, we identified the following regulable features as likely to be related toobserved quality of care and, therefore, as being worthy of investigation: (a) caregiver ed-ucation and specialized training, (b) number of children in the home, and (c) governmentlicensing.

1.1.1. Caregivers’ education and trainingSeveral researchers have previously reported that more highly educated providers offer

higher quality care as assessed by indices of positive caregiver behavior (Clarke-Stewart,Gruber, & Fitzgerald, 1994; Kontos et al., 1995; Rosenthal, 1994; Stallings, 1980) and globalquality scores (Burchinal, Howes, & Kontos, 2002; Goelman, 1988). These differences have notalways been observed, however (Kontos, 1994). Similarly, in a substantial number of studies, ithas been reported that care providers with specialized training in child care or child developmentprovide better quality care on global scales (Burchinal et al., 2002) and are more sensitive

K.A. Clarke-Stewart et al. / Early Childhood Research Quarterly 17 (2002) 52–86 55

and do more teaching (Bollin, 1990; Clarke-Stewart et al., 1994; Fischer & Eheart, 1991;Fosburg, 1981; Kontos et al., 1995; Kontos, Howes, & Galinsky, 1996; Howes, 1983; Howes,Keeling, & Sale, 1988), but these findings have not been replicated in all studies (Kontos, 1994;Rosenthal, 1994).

A limitation of many of these studies is that investigators have focused on bivariate asso-ciations between caregiver education and training and observed quality of care; they have notdetermined the independent contributions of general education and specialized training. Norhave other caregiver characteristics such as professionalism or mental health been controlledin the analyses in order to investigate the unique contributions of education and training. Afurther limitation of earlier research is that these relations between caregiver education andtraining and observed quality of care have not typically been examined for children of varyingages. In the present study, we examined the independent links between caregivers’ education,training, and observed quality of care for children at three ages, while controlling for othercaregiver characteristics and features of the child-care home. We expected to find significantlinks with both caregiver education and caregiver training with these statistical controls inplace.

1.1.2. Number of childrenEvidence concerning relations between the number of children in the child-care home and ob-

served care quality is extensive but somewhat inconsistent. In a number of studies, researchershave found that caregivers were more positive and responsive to children when fewer childrenwere present (Clarke-Stewart et al., 1994; Elicker, Fortner-Wood, & Noppe, 1999; Howes,1983; Stallings, 1980). In the study by Clarke-Stewart et al. (1994) and in the National DayCare Home Study (Fosburg, 1981), in fact, group size was the strongest predictor of home careproviders’ behavior. The same was true for infants in the NICHD Study of Early Child Care(NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 1996); the number of children for whom thecaregiver was responsible was the strongest contributor to observed positive caregiving whenthe infants were 6 months of age.

This link with group size has not been observed in every study, however (e.g., Burchinalet al., 2002; Kontos, 1994). Moreover, in the Family and Relative Care Study (Kontos et al.,1995), family child-care homes with more children received higher ratings on the Family DayCare Rating Scale (FDCRS; Harms & Clifford, 1989) than homes with fewer children. Thereason for the apparent discrepancy appeared to be the caregivers’ training and reasons forproviding care, which were not controlled in the group size analyses. Caregivers caring foronly one or two children tended to have less specialized training and to be more likely toview their role as temporary; caregivers who cared for more children were more professionallycommitted. In the Vancouver Project, Pence and Goelman (1991) reported similar relationsbetween group size, caregiver training, and professional commitment. Caregivers who cared formore children were likely to have specialized training, to be committed to family child care asa career, and to provide higher quality care. In present study, we explored the relation betweenthe number of children in the child-care home and the quality of care, while controlling forcaregiver background variables such as training and professional commitment. We predictedthat, with caregiver background controlled, better quality care would occur in homes withfewer children.

56 K.A. Clarke-Stewart et al. / Early Childhood Research Quarterly 17 (2002) 52–86

Another factor considered in the current investigation was the number of children of variousages. The National Association for Family Child Care has devised a “point system” that takesinto account the number of children of different ages in a child-care home. A child-care homeis given “points” that represent a weighted sum of the number of children in different agecategories. Each child under age 2 is given 33 points; each 2-year-old gets 25 points; childrenaged 3–6 get 16 points each; and children over age 6 each receive 10 points (Modigliani &Bromer, 1997). The National Association proposed that child-care homes with one caregivershould total fewer than 100 points, whereas those with two paid caregivers present at least halfthe time should total fewer than 175 points. The link between “points” and quality of care hasbeen tested empirically in only one study that we are aware of. Burchinal et al. (2002) found noreliable linear relation between group size points and the quality of care as measured by a globalrating (FDCRS). The present study allowed us to examine the effect of “point sizes” on thetwo measures of child-care home quality, the CC-HOME and the positive caregiving ratings,and to determine if better quality care was offered when points did not exceed recommendedlevels. We predicted that compliance with group size point cut-offs would be related to betterquality care.

1.1.3. Government licenseAlthough it is often assumed that the quality of care in licensed child-care homes is su-

perior to that in unlicensed homes, the research documenting positive effects of licensing isnot extensive. Study of this issue is complicated by the fact that states vary in whether theyissue licenses and what they require of the licensee. Despite this variability, there is someevidence that licensed homes provide higher quality care than unlicensed homes. Specif-ically, in the three-state Family and Relative Care Study and in the California LicensingStudy, licensed caregivers were observed to provide higher quality care and to be moresensitive to the children in their care (Burchinal et al., 2002). Goelman and Pence (1987)also reported that licensed programs in Canada obtained higher scores on the FDCRS thandid nonlicensed child-care homes. The NICHD data set provided an opportunity to furtherexamine the effect of licensing on the quality of care, across the broader variability repre-sented by nine different states. We predicted that quality of care would be higher in licensedhomes.

1.2. Nonregulable features and the quality of care

In our second question in the present study, we asked how quality of care was related tononregulable features of child-care homes. The nonregulable factors we selected for investiga-tion were the following: (a) the caregiver’s professional attitude toward being a care provider,(b) the length of her experience in the child-care field, (c) her age, (d) her beliefs about childrearing, (e) her mental health, and (f) the presence of her own children in the child-care home.It is unlikely that states can regulate these factors, but they may be important markers of qual-ity of care nonetheless. Parents might, for example, consider these factors in their interviewswith prospective caregivers. Moreover, these factors might mediate the effects of the regulablefactors. For example, if caregivers’ education predicts the quality of care, this may be be-cause education forms the basis for the caregiver’s beliefs about how to discipline and manage

K.A. Clarke-Stewart et al. / Early Childhood Research Quarterly 17 (2002) 52–86 57

children. These nonregulable factors were selected on the basis of known links with caregivers’or parents’ behavior.

1.2.1. Caregivers’ professionalismAn association between caregivers’ professional attitudes toward providing care and the

quality of care they provide has been reported in several studies. Fosburg (1981) and Penceand Goelman (1991) found that caregivers who participated in a family child-care network—anindication of their professionalism—provided higher quality care. In the Family Child Care andRelative Care study (Kontos et al., 1995), “intentional” care providers were more committed tocaring for children and offered higher quality, warmer, and more attentive care. Stallings (1980)observed that child-care home providers who considered themselves professionals were morelikely to talk, help, teach, and play with the children and provided better physical environments;caregivers who provided family care only because no better job was available or as an informalagreement with friends, neighbors, or relatives were less interactive and stimulating and spentmore time on housework. Therefore, we predicted that caregivers with more professionalattitudes would provide better care.

1.2.2. Caregivers’ experienceFindings from previous research related to caregiver experience and quality of care are not

so straightforward. In some studies, more experienced home care providers have been observedto provide warmer and more responsive care (e.g., Howes, 1983), but these results have notbeen replicated in other studies (Kontos, 1994; Rosenthal, 1994). In other studies, the oppositerelation has been found: Burchinal et al. (2002) observed lower FDCRS scores and more detach-ment when caregivers had more experience. In the National Day Care Home Study (Fosburg,1981), caregivers whose interactions with the children were most educational had a moderateamount of experience, 7–11 years in the field, showing yet another relation between caregiverexperience and care quality. Finally, in analyses of care for 6-month-olds in the NICHD Studyof Early Child Care (NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 1996), significant but smallnegative correlations between caregivers’ experience and positive caregiving appeared to bethe result of more experienced caregivers working in child-care homes with more children.When group size, child–adult ratio, and caregivers’ child-rearing beliefs were statistically con-trolled, experience, per se, was not associated with positive caregiving. In the present study, weexamined the contribution of caregiver experience, while controlling for other nonregulableand regulable factors. We expected that if there was an effect of experience, when other factorswere controlled, a moderate amount of experience would predict higher quality care.

1.2.3. Caregivers’ ageIn previous research, caregivers’ age has not been found to be a significant predictor of

observed caregiving quality (Kontos, 1994; Pence & Goelman, 1991; Rosenthal, 1994), al-though it has certainly been related to more positive maternal behavior (e.g., Ragozin et al.,1982). Nevertheless, it was included as a variable in the present study because it is a sim-ple demographic factor that might be related to quality when other caregiver characteristicsare controlled. We made no specific prediction that age would be related to higher quality ofcaregivers’ behavior, but explored this possibility.

58 K.A. Clarke-Stewart et al. / Early Childhood Research Quarterly 17 (2002) 52–86

1.2.4. Caregivers’ child-rearing beliefsWe did predict that quality of care would be related to having more child-centered beliefs

about child rearing. This prediction was based on research by Rosenthal (1994) showing thatcaregivers who believed in less authoritarian control initiated more frequent educational activ-ities and provided better physical environments for the children in their care. It also followsfrom research showing that such child-rearing beliefs predict more positive and responsivebehavior in mothers (e.g., NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 1999a) and higherscores on the HOME (Palacios, Gonzalez, & Moreno, 1992).

1.2.5. Caregivers’ mental healthAnother nonregulable variable that we expected would be related to the quality of care,

although it has not been considered in previous research on child care, is the care provider’smental health. This factor, too, has been studied in research on parents. Mothers who are lessdepressed behave in more positive and involved ways with their children (e.g., NICHD EarlyChild Care Research Network, 1999c). It seemed reasonable to expect that mental health wouldoperate similarly for paid caregivers, and this was explored in the present study.

1.2.6. Presence of Caregivers’ childrenFinally, the last nonregulable feature we investigated was the presence of the caregivers’

own children in the child-care home. Kontos (1994) observed that care providers who werelooking after their own children at the same time as they were caring for other children scoredhigher on global quality of care assessed with the FDCRS, but there was no difference in thefrequency of their high-level involvement with individual children. Fosburg (1981) found thatcaregivers did less teaching, talking, and playing with individual children when their own childwas present. Based on these studies, we expected that caregivers whose children were presentin the child-care home would provide higher overall quality care on the CC-HOME but wouldnot be rated higher on the quality of behavior with individual study children.

1.3. Effects of regulable features, nonregulable features, and observed quality of careon child development outcomes

Our third question in this study was whether children would perform better on assessmentsof their cognitive, social, and behavioral development when they were cared for in child-carehomes characterized by higher levels of regulable features, more positive nonregulable char-acteristics, and better observed quality. Previous research examining these relations betweenchild-care home quality and children’s developmental outcomes has been limited, especiallywith respect to research focused specifically on child-care home settings and standardizedmeasures of developmental outcomes.

1.3.1. Regulable featuresClarke-Stewart et al. (1994) reported relations between regulable features (caregiver edu-

cation and number of children) and child outcomes (cognitive development) for children inall types of home care, including child-care homes, but these investigators did not specifi-cally ask if regulable features predicted outcomes for the subsample of children who were in

K.A. Clarke-Stewart et al. / Early Childhood Research Quarterly 17 (2002) 52–86 59

child-care homes. In a study that focused exclusively on child-care homes, Howes and Stewart(1987) reported that children engaged in higher levels of play in the child-care home settingwhen there were fewer children in that setting. However, Kontos (1994), in a relatively smallstudy, found no relation between caregivers’ education and specialized training or number ofchildren in the child-care home and children’s scores on standardized cognitive and languagetests. Blau (1997), similarly, analyzing data from a much larger study, the National Longitudi-nal Study of Youth, found that relations between child outcomes and caregivers’ educationalbackground and the number of children in the child-care home were small and inconsistent.By investigating associations between regulable features and child development outcomes forchildren in child-care homes, the present study offered important information to shed light onthe inconsistent results in these previous studies.

1.3.2. Nonregulable featuresEvidence in the published literature regarding relations between nonregulable aspects of

child-care homes and child development outcomes is scarce and warrants more attention. Sev-eral investigators have reported negative relations between maternal depression and children’sdevelopmental outcomes (Beardslee, Bemporad, Keller, & Klerman, 1983; Gelfand & Teti,1990; NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 1999c). It is not clear, however, whethersuch associations would also appear in child care, which lacks the genetic connection of motherand child. To investigate this issue, in the present study, we examined children’s cognitive andsocial development in relation to their caregivers’ depressive symptoms. Previous researchersalso have reported relations between mothers’ beliefs about child rearing and children’s devel-opment (see Sigel, McGillicuddy-DeLisi, & Goodnow, 1992; Smetana, 1994), suggesting thatcaregivers’ beliefs may also be predictive of children’s development. However, this link, too,has seldom been explored in child-care research. Kontos (1994) assessed home care providers’child-rearing beliefs, but she did not report whether they were related to child outcomes. OnlyRosenthal (1994) reported that children whose caregivers had more authoritarian beliefs wereless socially competent. Thus, there is some reason to expect that caregiver beliefs will predictchild outcomes, but limited empirical support for this prediction. The regulable features ofcaregivers’ age, experience, and the presence of the caregiver’s child in care were also inves-tigated in Kontos’s (1994) study. She found that caregivers’ age was unrelated to children’scognitive, language, and social outcomes, but children whose caregivers had more professionalexperience in the child-care field performed better on cognitive tests, and children in homesin which the caregiver’s own child was present were rated as less sociable. Because previousresearch on the prediction of child outcomes from nonregulable variables was so scarce, wedid not make specific predictions about links between children’s developmental outcomes andcaregivers’ mental health, child-rearing beliefs, experience, professionalism, and the presenceof the caregiver’s children in the home. However, because this is an important and understudiedaspect of home care, we explored the possibility that such associations might exist.

1.3.3. Observed quality of careWe also investigated whether children’s developmental outcomes would be predicted by

the observed quality of care in the child-care home. In an early, unpublished study, Goldenet al. (1978) showed that children did better on assessments of cognitive ability and social

60 K.A. Clarke-Stewart et al. / Early Childhood Research Quarterly 17 (2002) 52–86

competence when caregivers offered them more cognitive and social-emotional stimulation.Similarly, both Goelman (1988) and Kontos (1994) reported positive correlations betweenglobal quality (FDCRS scores) and children’s scores on the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test.Other investigators found relations between observed quality and children’s functioning withinthe child-care home setting: higher quality care was associated with more competent play withcaregivers, peers, and objects (Howes & Stewart, 1987), higher social competence with peers(Rosenthal, 1994), and higher cognitive competence and more secure attachment relationshipswith the caregiver (Elicker et al., 1999; Kontos et al., 1995). In the present study, we predictedthat the quality of observed care, assessed in terms of caregivers’ behavior with individual chil-dren and with the more global inventory, the CC-HOME, would be significantly and positivelyrelated to children’s cognitive, social, and behavioral development.

We also investigated whether observed quality of care mediated the associations betweenchild outcomes and regulable and nonregulable factors. The reason to conduct such analyseswas to determine whether the process by which these factors influence children’s behaviorand development—if the factors indeed turned out to be associated with child outcomes—wasthrough the caregiver’s behavior and the environment in the home. This would lend credenceto the argument that regulable or nonregulable features “cause” differences in children’s per-formance, rather than just being statistically associated with those differences. This step hasnot been taken in previous research on child-care homes, even when researchers have assessedboth regulable and nonregulable features and observed quality of care (Kontos et al., 1995). Ithas proven to be an important and informative step in investigating the significance of qualityin child-care centers (NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, in press), and we expectedthat it would prove informative in research on child-care homes as well.

1.4. Study predictions

In summary, we expected that both regulable and nonregulable factors would be related toobserved quality of care. Higher quality care was anticipated when the caregiver had receivedmore education and training, there were fewer children in the child-care home, and the homewas licensed. Higher quality care was also expected when the caregiver had a more profes-sional attitude toward care, a moderate amount of experience in the child-care field, morechild-centered beliefs about how to rear children, better mental health, and her own childrenin the child-care home. In addition, we predicted that child outcomes would be positivelyrelated to observed quality of care. We did not predict direct associations between regulableand nonregulable factors and child outcomes, because previous research on these relations waslimited and observed links, weak or inconsistent. We did not make specific predictions abouthow nonregulable factors would mediate the effects of regulable factors, because there was noresearch basis for such predictions.

In order to investigate our predictions and answer the three overarching research questionsposed in the study, we analyzed associations between regulable features, non regulable features,observed care, and child outcomes in the context of family variation. It was essential to rule outthe possibility that observed associations were the result of family factors that covaried withchild-care and child factors. Because parents select the care arrangements for their children, itis possible that they introduce a confound between the quality of care in the child-care home

K.A. Clarke-Stewart et al. / Early Childhood Research Quarterly 17 (2002) 52–86 61

and the quality of care the child experiences in the family. Therefore, in the present study, wecontrolled for a range of family factors (family income, mother’s education, partner status, andchild’s ethnicity).

Our final prediction was that child outcomes would be linked to observed quality of care forchildren from both lower and higher socio–economic levels. In previous studies of child-carehomes, it has been observed that quality of care was related to children’s cognitive and so-cial development across different levels of parental education (Rosenthal, 1994) and ethnicity(Kontos et al., 1995). In these studies, family factors did not significantly moderate the effectsof child-care quality in child-care homes, as has sometimes been observed in child-care centers(Clarke-Stewart et al., 1994; Peisner-Feinberg & Burchinal, 1997). This issue was investigatedin the present study.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Participants in the study were recruited during the first 11 months of 1991 from hospitalslocated in or near Little Rock, AK; Irvine, CA; Lawrence, KS; Boston; Philadelphia; Pittsburgh;Charlottesville, VA; Morganton, NC; Seattle; and Madison, WI. During selected samplingperiods, all women giving birth in each hospital were screened. Mothers were excluded if theywere giving the baby up for adoption, had medical complications, were under 18 years of age,did not speak English, planned to move within the next year, lived outside the area or in aneighborhood considered unsafe for visits, or if the baby was a multiple birth or had medicalcomplications. A total of 8,986 women were screened in the hospital; 5,416 were eligibleand agreed to be called in 2 weeks. A conditionally random sample of 3,015 was selectedfrom the eligible list. The conditioning assured representation of at least 10% of single-parenthouseholds, mothers with less than a high school education, and ethnic minority mothers.Additional screening was conducted at the 2-week phone call to exclude families planning tomove within the next 3 years and infants who had stayed in the hospital for more than one weekafter birth. A total of 1,526 mothers were eligible and agreed to the 1-month interview; 1,384 ofthese mothers completed the 1-month interview and were enrolled in the study. The resultingsample was diverse, including 24% ethnic minority children, 10% mothers without a highschool education, 14% single mothers, and 34% poor or near poor families (income-to-needsratio < 2). The recruited families were similar to the eligible families in the catchment hospitalson all these demographic variables. Of the 1,364 families who began the study, 1,216 (89%)continued through 36 months.

The total number of children in the sample who were in child-care homes with an unrelatedcaregiver was 242 at 15 months, 248 at 24 months, and 201 at 36 months. For the presentreport, we selected for analysis only those children who were observed in child-care homeswhere the care provider received payment for child care and there were at least two children,including the study child. The number of children who met these criteria and for whom relevantfamily and child outcome data were available was 164 at 15 months, 172 at 24 months, and146 at 36 months. (It was not possible to observe the child in 26% of the eligible homes, either

62 K.A. Clarke-Stewart et al. / Early Childhood Research Quarterly 17 (2002) 52–86

because the child-care home provider did not give permission or because the visit could not bescheduled within the assessment window.) Families included in the analyzed sample were ofhigher socio–economic status than those who were excluded (higher family income at 15 and36 months,M = 4.48 versus 3.18,t (242) = −2.66;M = 3.81 versus 2.83,t (248) = −2.97,p < .01, higher mother education at 24 months,M = 15.1 versus 13.9,t (242) = −2.99,p < .01, mother more likely to be partnered at 15 months,M = 83.8 versus 65.7%, Chi-square(1) = 6.10,p < .05).

2.2. Overview of procedures

Basic demographic information was collected by interviewing mothers at home when theinfant was 1-month-old. At 15, 24, and 36 months, families were visited at home and broughttheir children to the research facility; during these visits, children were observed in structuredand unstructured assessments and mothers completed questionnaires. At the same ages, chil-dren who attended any form of child care for at least 10 hours a week were observed in thechild-care setting in which they spent the most time. Observers rated the caregiver’s behaviorusing qualitative scales, and caregivers filled out questionnaires and were interviewed abouttheir background and attitudes.

2.3. Observed quality of child care

2.3.1. Positive caregiving ratingObservations in the child-care home settings were conducted on two half-day visits sched-

uled within a 2-week interval at each assessment age. At each visit, observers completed two44-minute cycles of the Observational Record of the Caregiving Environment (ORCE; NICHDEarly Child Care Research Network, 1996), an instrument developed for the NICHD Studyof Early Child Care to assess the characteristics of child care experienced by an individualchild. Each observation cycle consisted of three 10-minute observation periods during whichthe occurrence of specific child and caregiver behaviors was scored at 1-minute intervals. Ob-servers took brief notes for qualitative ratings after each of the first two 10-minute periods,kept lengthier notes as they observed for 14 minutes at the end of the cycle, and then madequalitative ratings. The rating categories included at 15 and 24 months were caregiver’s sensi-tivity and responsiveness to the child’s nondistress vocalizations, positive regard for the child,stimulation of the child’s cognitive development, detachment from the child (reversed), andflat affect (reversed). At 36 months, the categories of fostering exploration and intrusiveness(reversed) were added. A positive caregiving composite score was calculated as the averageof qualitative ratings made at the conclusion of each of the four observation cycles. Alphas onthis scale ranged from .82 to .89.

Observers from all 10 sites were trained at a central location, conducted practice visits attheir sites, and then coded videotapes and compared their records with master codes on threeoccasions, once prior to and twice during the period of data collection. Within-site reliabilitywas also established using live observations. Interobserver agreement (Pearson correlationcoefficients) on the videotapes at 15, 24, and 36 months, respectively, were .86, .81, .80; liveinterobserver agreement averaged .89, .89, and .90.

K.A. Clarke-Stewart et al. / Early Childhood Research Quarterly 17 (2002) 52–86 63

2.3.2. Child-care HOMEThe second measure of child-care quality in the study focused more broadly on the quality

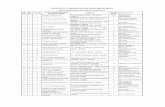

of the caregiving environment. Based on observation of the caregiver’s behavior with the studychild, observation of the physical environment, and an informal conversation with the caregiver,the CC-HOME includes 45 items in six categories at 15 and 24 months (Learning Materials,Variety, Responsivity, Acceptance, Organization, Involvement) and 58 items in eight categoriesat 36 months (Learning Materials, Variety; Responsivity, Acceptance, Language Stimulation,Physical Environment, Academic Stimulation, Modeling; see Table 1 for illustrative items).

Table 1Illustrative items from the CC-HOME at 36 months

Learning materials Two or more toys that teach colors, sizes and shapes are available to childThree or more puzzles are available to childTwo or more toys or games that help teach numbers are available to the child10 or more children’s books are available to the child

Language stimulation Child is encouraged to learn the alphabetCaregiver encourages child to talk and takes time to listenCaregiver uses correct grammar and pronunciationTwo or more toys that help teach the names of animals are available to child

Physical environment Building appears safe and free of hazardsOutside play environment appears safeInterior of home is not dark or perceptually monotonousRooms used by children are not overcrowded with furniture

Responsivity Caregiver converses with child two or more times during visitCaregiver answer child’s questions or request verballyCaregiver praises children’s qualities twice during visitCaregiver caresses, kisses, or cuddles child during visit

Academic stimulation Child is encouraged to learn colorsChild is encouraged to learn spatial relationsChild is encouraged to learn numbersChild is encouraged to learn to read a few words

Modeling Caregiver introduces observer to childChild can express negative feelings without harsh reprisalChild is permitted some choice in TV viewingTV is used judiciously

Variety Child is taken on field trip by caregiver at least every other weekChild is taken outside for play every day the child is in care (except in bad weather)Child has been involved in art/craft activity during the past weekCaregiver arranges for child to have vigorous physical activity three or moretimes a week

Acceptance Caregiver does not scold or derogate or yell at child more than once during the visitCaregiver does not use physical restraint during visitCaregiver neither slaps nor spanks child during visitNo more than one instance of physical punishment has occurred during the past week

64 K.A. Clarke-Stewart et al. / Early Childhood Research Quarterly 17 (2002) 52–86

The total number of items checked was used as an indicator of overall quality of the caregivingenvironment (α = .84 at 15 months, .82 at 24 months, .87 at 36 months). Interobserveragreement (Pearson correlations) on the CC-HOME was above .90 at all ages.

Although these two measures, positive caregiving ratings and CC-HOME, were signifi-cantly correlated at each of the assessment ages,r = .69, .56, .62,p < .001, at 15, 24,and 36 months, they are methodologically and conceptually distinct. The CC-HOME scaleincludes items assessing the physical environment, materials, and caregiver behavior, whereasthe positive caregiving ratings focus exclusively on the caregiver’s behavior with the studychild.

2.4. Regulable features of child care

Three categories of regulable features of child care were included in the study, as follows:

2.4.1. Caregiver’s education and trainingInformation about the caregiver’s education and training was obtained from interviews with

the child-care providers and used to create the following variables. Caregiver education wasscored as a 6-level variable, with 1= less than high school, 2= high school graduate, 3=some college/AA degree, 4= college degree, 5= some graduate work/MA, 6= advanceddegree. The amount of specialized training the caregiver had received was defined as the level oftraining in child development, child care, or early childhood education, categorized as 0= notraining, 1= high school level training, 2= certification, vocational/adult education training,or degree in related field, 3= some college training, and 4= college or graduate degreein child development, child care, or early childhood education. Recent training was definedas specific training in a child-care related area within the past year, scored as 0= no recenttraining, 1= some recent training.

2.4.2. Number of childrenA variable reflecting the number of children in the child-care home was collected from

the caregiver interview. This variable indicated how many children were served regularly orenrolled in the home; it was quite highly correlated with the number of children observedat the end of each ORCE cycle:r = .73 at 15 months, .79 at 24 months, and .68 at 36months,p < .0001. A second variable was derived from the number of enrolled childrenweighted by their ages. Based on the system devised by Modigliani and Bromer (1997) forthe National Association for Family Child Care, each child-care home was assigned “points”that represented a weighted sum of the number of children cared for in various age categories(each child under age 2 was given 33 points; each 2-year-old was given 25 points; childrenaged 3–6 were given 16 points each; and children over age 6 received 10 points). This scorewas used to determine whether the home was in compliance with recommended points cut-offs(≤100 points for child-care homes with one caregiver,≤175 points for homes with two paidcaregivers). A dichotomous variable reflecting noncompliance versus compliance with theappropriate points cut-off was created for each child care home. The two measures, numberof children enrolled and noncompliance with group size points, were included among theregulable variables.

K.A. Clarke-Stewart et al. / Early Childhood Research Quarterly 17 (2002) 52–86 65

2.4.3. Government licenseThis dichotomous variable indicated whether or not the child-care home was licensed by a

government agency—state, county, or community.

2.5. Nonregulable characteristics of child care

The six nonregulable features of child care included in the study were the following:

2.5.1. Caregiver’s professionalismA composite variable for professionalism was created to reflect the caregiver’s involvement

in professional activities, computed as the sum of the following items: membership in a pro-fessional child-care organization, satisfaction with work in child care, expectation that childcare will be a relatively lengthy career, and professional reasons for being a child-care provider(e.g., “to use my experience and/or education in child development”). Cronbach’s alphas forthis composite measure were .84 at 15 months, .81 at 24 months, and .82 at 36 months.

2.5.2. Caregiver’s experienceThe number of years the caregiver had been providing child care was used as a measure of

experience.

2.5.3. Caregiver’s ageAge in years.

2.5.4. Caregiver’s beliefs about childrenCaregivers’ beliefs were measured with the Modernity Scale (Schaefer & Edgerton, 1985), a

questionnaire that discriminates between “traditional,” or relatively authoritarian approaches tochild rearing, and more “modern,” positive, or child-centered approaches. Caregivers holdinga more traditional view agreed with statements such as “Children must be carefully trainedearly in life or their natural impulses will make them unmanageable.” “Children should alwaysobey the teacher.” “The major goal of education is to put basic information into the mindsof the children.” Caregivers with more child-centered beliefs agreed with statements such as“Children should be allowed to disagree with their parents if they feel their own ideas are better.”“Children learn best by doing things themselves rather than listening to others.” Cronbach’salpha for this scale for caregivers in the NICHD Study was .89; reliability in Schaefer andEdgerton’s sample was .84.

2.5.5. Caregiver’s depressive symptomsThe level of depression experienced by the caregiver was measured with the Center for

Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977), a 20-item questionnairethat identifies depressive symptomatology in the general population (alpha for caregivers inthe NICHD Study= .82; test-retest reliability in Radloff’s sample= .57).

2.5.6. Own child presentWhether the care provider had her own child or children present in the home during the time

the study child was in care was coded dichotomously.

66 K.A. Clarke-Stewart et al. / Early Childhood Research Quarterly 17 (2002) 52–86

2.6. Family variables

A set of four, standard family demographic variables were used as control variables inthe study, in addition to the child’s gender and age at the time of observation, and the site(geographic location) of the child-care home.

2.6.1. Ethnicity of childEthnicity was coded as White, African-American, Latina/Latino, or other.

2.6.2. Mother’s educationMother’s education was a 6-level variable, with 1= less than high school, 2= high school

graduate, 3= some college/AA degree, 4= college degree, 5= some graduate work/MA,6 = advanced degree.

2.6.3. Mother’s partnered statusWhether the mother lived with a partner (husband or live-in partner) at the time of the

assessment.

2.6.4. Family incomeThe index of family income was the ratio of income to needs, calculated as the total family

income divided by the poverty threshold for their family size, averaged over assessments(mean= 3.75; SD = 2.50; range= 0–19) This variable was log transformed in analyses,because it was not normally distributed.

2.7. Child outcome variables

Cognitive and social outcomes for children were assessed at 15, 24, and 36 months. At 15and 24 months, the Bayley Mental Development Index (MDI, Bayley, 1969, 1993) was usedto assess children’s overall cognitive development. The original version of the Bayley wasadministered at 15 months, and the revised Bayley (BSID-II) at 24 months. The Bayley MDIis the most widely used measure of developmental status for children in the first 2 years of life.At 36 months, the 67-item scale for language comprehension from the Reynell DevelopmentalLanguage Scales (Reynell, 1991) was used to assess the child’s cognitive ability. This measurewas chosen because prior research has demonstrated that language is one area of overallcognitive functioning that is associated with child care and intervention effects. The ReynellVerbal Comprehension Scale is internally reliable (split-half coefficient, corrected throughthe Spearman–Brown procedure= .93) and is correlated with the Wechsler Preschool andPrimary Scale of Intelligence administered at the same age (r = .70) and with the WISCadministered at age 7(r = .71). Research assistants who administered all standardized tests ofcognitive development were trained to criterion at a central location prior to the beginning ofdata collection.

Mothers’ and caregivers’ reports of the children’s problem behavior and positive social be-havior were obtained at 24 and 36 months using the Child Behavior Checklist-2/3 (CBCL-2/3,Achenbach, Edelbrock, & Howell, 1987) and the Adaptive Social Behavior Inventory (ASBI,

K.A. Clarke-Stewart et al. / Early Childhood Research Quarterly 17 (2002) 52–86 67

Hogan, Scott, & Bauer, 1992). The CBCL lists 99 behaviors and respondents indicate how char-acteristic each has been of the child over the last 2 months (0= not true, 1= sometimes true,2 = very true). The CBCL-2/3 is reported to show good test-retest reliability and concurrentand predictive validity; it discriminates between clinically referred and nonreferred toddlersand predicts problem scores over a 3-year period (Achenbach et al., 1987). The ASBI consistsof three subscales, one of which assesses negative behavior and two of which assess prosocialbehavior. Scale reliabilities were .71 for the negative scale (Disruptive behavior) and .82 and.84 for the prosocial scales (Expressive behavior and Compliant behavior). The 30 items inthe instrument are simply and positively worded, and mothers or caregivers indicate for eachwhether it is true of the child rarely, sometimes, or almost always. For the present study, the twobroad-band factors (Externalizing and Internalizing) and the two narrow-band factors (SleepProblems and Somatic Problems) from the CBCL-2/3 and the Disruptive behavior subscalefrom the ASBI were standardized and summed as an index of child behavior problems. Thetwo other ASBI subscales, Expressive behavior and Compliant behavior, were standardizedand summed to indicate positive social behavior or cooperation.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of child-care homes in the sample

On average, there were 6.7 children enrolled in the child-care homes in the study, accordingto caregivers’ reports. The maximum number enrolled was 30. The number of children presentduring our observations, averaged 4.9 (maximum= 14). The average number of group sizepoints was 145 (range= 16–492) in homes with a single caregiver (93% of the homes) and300 (range= 159–532) in homes with two caregivers. Just over half of the care providers hadtheir own child present at the time we observed (58%). In terms of education and training, 19%of the caregivers had bachelor’s degrees or higher, 39% had attended college but not receiveda degree, and 32% had graduated from high school; 48% had no specialized training; 6% hadhigh school training; 17% had a certificate or vocational training in early childhood educationor child care or had a degree in a related field such as nursing or elementary education; 25%had some college training, and 4% had a college degree in child development, child care,or early childhood education; 39% had received training in the last year; 23% belonged to aprofessional organization. Caregivers had been working in child care for periods ranging from1 to 40 years; on average, 6 years. They ranged in age from 13 to 68 years (mean= 37); 7%were African-American, 5% were Latina, and 2% were from other ethnic-minority groups.About one third of the homes (35%) were licensed.

3.2. Prediction of child-care quality

To determine how regulable and nonregulable child-care variables were related to the qualityof care observed in these child-care homes, we conducted Hierarchical Linear Modeling (HLM)analyses. These are regression analyses that combine data across the three assessments (15, 24,and 36 months) and the three sets of predictor variables (family, regulable, and nonregulable

68 K.A. Clarke-Stewart et al. / Early Childhood Research Quarterly 17 (2002) 52–86

factors). They indicate the strength and significance of associations between these predictorvariables-treated both as separate variables and as blocks of variables—and observed child-carequality (positive caregiving ratings and CC-HOME), while controlling for site and child’s age.The analyses involved first fitting a model that tested whether the association between eachpredictor variable and quality varied across the three assessment ages. Block tests were thenused determine whether the set of regulable and nonregulable predictors showed differentpatterns of association with observed care quality over time. The block was dropped from theanalysis model if that block test was not significant. The results are presented in Table 2.

The first finding revealed by these HLM analyses was that the observed quality of care inchild-care homes was significantly and consistently related to the family variables. Analysesof the specific family variables indicated that children receiving high quality caregiving weremore likely to be girls and that children in higher quality child-care homes had parents withhigher incomes.

3.2.1. Regulable features and observed qualityThe block of regulable variables—caregivers’ education, training, recent training, number

of children in the home, noncompliance with group size points, and license status—predictedboth the positive caregiving rating and the CC-HOME (see Model 1, Table 2). Specifically,caregivers with higher levels of education and with specialized training within the last yearreceived higher scores on the CC-HOME. Caregivers with higher levels of specialized trainingreceived higher scores on both the positive caregiving rating and the CC-HOME. Caregivers inhomes that were not in compliance with the group size points cut-offs received lower positivecaregiving ratings. The number of children enrolled was not related to the quality of care,either linearly or curvilinearly, as tested by the number enrolled×number enrolled interactionterm in the HLM analysis. Nor was quality of care related to whether or not the home waslicensed. Associations with the rating of observed caregiving were not different at the threeages (interactions with age were nonsignificant for the block and for each regulable variable).However, CC-HOME quality was more strongly related to caregiver education and compliancewith group size points at 36 months than at younger ages.

To refine the analysis of caregiver education, analyses of covariance were conducted (con-trolling for mothers’ education), in which we contrasted levels of caregiver education that arepotentially regulable. In the first analysis we contrasted caregivers who had not graduated fromhigh school with caregivers who had a high school diploma. As expected, caregiving qualitywas lower in the group that had not graduated from high school (positive caregiving ratingfor low education,n = 46,M = 2.62, SD = 0.08, for high education,n = 422,M = 2.85,SD= 0.03,F = 7.92,p < .01; CC-HOME for low education,n = 46,M = 31.4,SD= 0.88,for high education,n = 421,M = 38.4, SD = 0.29, F = 55.2, p < .001). In the secondanalysis, we contrasted caregivers who had not attended college with caregivers who had at-tended college. Again, the two groups were significantly different (positive caregiving ratingfor low education,n = 196,M = 2.74,SD= 0.04, for high education,n = 272,M = 2.89,SD = 0.03, F = 9.39, p < .001; CC-HOME for low education,n = 195, M = 35.5,SD= 0.43, for high education,n = 272,M = 39.2, SD= 0.37,F = 42.2, p < .001).

Although licensing was not a significant predictor in the multivariate analysis, we suspectedthat an effect of licensing might be masked by some degree of collinearity between license status

K.A. Clarke-Stewart et al. / Early Childhood Research Quarterly 17 (2002) 52–86 71

and other regulable factors. Therefore, we examined bivariate relations between licensing andthe regulable factors and observed quality (see Table 3). These analyses indicated that licensedhomes served a large number of children and were less likely to be in compliance with thegroup size points cut-off and that licensed caregivers were more likely to have received trainingin the last year. There was also a significant bivariate association between licensing and theCC-HOME when these other regulable variables were not included in the analysis. Thus,collinearity between licensing and these three regulable variables appears to have reduced theassociation between licensing and care quality to nonsignificance when they were included inthe multivariate analyses.

3.2.2. Nonregulable factors and observed qualityThe block of nonregulable variables-caregivers’ professionalism, experience, age, child-

centered beliefs, depression, and own child present—significantly predicted scores on theCC-HOME (see Model 2, Table 2). Specifically, caregivers with more child-centered beliefsreceived higher scores on the CC-HOME. They also received higher ratings on positive care-giving, although the block of nonregulable variables as a whole was not significantly relatedto this measure of quality. Neither measure of observed quality was related to caregivers’ pro-fessionalism, experience (either linearly or curvilinearly), age, or depressive symptoms, or towhether the caregiver’s own child was present in the child-care home. Associations with themeasures of observed caregiving were not different at the three ages (interactions with agewere nonsignificant).

3.2.3. Regulable factors, nonregulable factors, and observed qualityThe next HLM analyses included family variables and both regulable and nonregulable

variables (see Model 3, Table 2). When both regulable and nonregulable factors are includedin analyses as predictors of observed quality of care, it is possible to investigate whethernonregulable processes mediate relations between regulable features and observed quality(Baron & Kenny, 1986). With caregivers’ beliefs about child rearing included in the analysis,relations between caregiving training and observed quality of care were no longer significantfor either positive caregiving ratings or CC-HOME scores. In other words, caregivers’ beliefsmediated the effects of caregivers’ training on child care quality. Nonregulable variables didnot, however, mediate the effect of caregiver education or recent training on the CC-HOME.In addition, the Model 3 analyses indicate that caregivers with more child-centered beliefsreceived higher ratings of positive caregiving and higher scores on the CC-HOME, even withthe regulable variables controlled. There was only one significant interaction with age, for thenumber of children enrolled with the positive caregiving rating. (There was a stronger negativeassociation at 24 months.)

3.3. Prediction of child outcomes

HLM analyses relating family and child-care variables to child performance measures, acrossthe three ages, were conducted next. These analyses were used to investigate the predictionof child outcomes from four sets of variables: family variables, regulable child-care vari-ables, nonregulable child-care variables, and observed quality of care variables. The effects of

K.A. Clarke-Stewart et al. / Early Childhood Research Quarterly 17 (2002) 52–86 73

family and regulable variables were examined in Model 1, family and nonregulable variables inModel 2, family, regulable, and nonregulable variables in Model 3, and the full set of variablesin Model 4. Site and age were controlled in these analyses as well, and as before, we fitted thefull model and then removed the nonsignificant interaction blocks. Analyses of interactionswith child age and family income were included in the analyses to examine the possibility thateffects were different at the three different ages or for children who came from more or lessaffluent families. Results of all these analyses are in Table 4.

These analyses indicate, first, that family variables were related to three of the five child out-come measures: cognitive ability and caregivers’ reports of cooperation and behavior problems.Specifically, girls, children who were not African-American, and children whose mothers weremore educated did better on cognitive tests. According to their caregivers, Hispanic childrenand boys were less cooperative and Hispanic children had more behavior problems. Familyvariables were not related to mother-reported measures of children’s cooperation and behaviorproblems.

3.3.1. Regulable features and child outcomesWith family variables controlled, the block of regulable variables-caregivers’ education,

training, recent training, number of children enrolled, noncompliance with group size points,and license status—was significantly related to children’s cognitive performance (Model 1,Table 4); specifically, caregivers with higher levels of education and training within the pastyear had children who scored higher on cognitive tests. The associations between cognitiveability and the block of regulable variables and, specifically, caregiver education, were stillsignificant when the nonregulable variables were controlled (Model 3). There were no signif-icant associations between the regulable variables and the other child outcomes (mother- orcaregiver-reported cooperation or behavior problems), nor did the associations between regu-lable variables and child outcomes differ according to the child’s age (all interactions with agewere nonsignificant). Child outcomes were not significantly related to whether or not the homewas licensed, to how much specialized training the caregiver had, to the number of childrenenrolled in the child-care home (either linearly or curvilinearly), or to whether the home wasin compliance with recommended group size cut-offs.

When caregiver education was dichotomized and an analysis of covariance (controlling formothers’ education) was conducted, it was revealed that children whose caregivers had beento college scored higher on cognitive tests at 24 and 36 months than children whose caregivershad not attended college (at 24 months,M = 97.0, SD = 1.28, n = 93, versusM = 92.7,SD= 1.49,n = 69,F = 4.66,p < .05; at 36 months,M = 101.3,SD= 1.64,n = 80, versusM = 94.5,SD= 1.93,n = 58,F = 7.09,p < .01). It was not possible to compare caregiverswith and without a high school diploma, because then for these groups were too small.

3.3.2. Nonregulable factors and child outcomesThe block of nonregulable child-care variables—caregivers’ professionalism, experience,

age, beliefs, depression, and presence of own child—was related to two child outcomes, co-operation and behavior problems reported by the caregiver (Model 2). Specifically, more de-pressed caregivers rated the children in their care as being less cooperative and having morebehavior problems. These associations were significant at all ages assessed (no significant

K.A. Clarke-Stewart et al. / Early Childhood Research Quarterly 17 (2002) 52–86 79

interactions with age) and remained significant even when the regulable variables (Model 3)and the observed quality of care (Model 4) were controlled. Child outcomes were not signifi-cantly related to the caregiver’s age, experience (either linearly or curvilinearly), profession-alism, child-rearing beliefs, or whether the caregiver’s child was in the child-care home whilethe study child was there.

3.3.3. Regulable factors, nonregulable factors, observed care, and child outcomesIn the fourth model analyzed in the HLM analyses, associations between child outcomes and

observed quality of care were tested, controlling for all the other variables of site, child’s age,family variables, regulable and nonregulable child-care variables. Associations with observedquality of care were significant for all five of the child outcomes. Specifically, children whosecare providers offered more positive caregiving were more cooperative according to theircaregivers and mothers and had fewer behavior problems according to their mothers; childrenwho were in higher quality care assessed with the CC-HOME performed better on tests ofcognitive abilities and were more cooperative and had fewer behavior problems accordingto their caregivers. An anomalous finding was that children in homes with higher scores onthe CC-HOME exhibited more behavior problems according to their mothers. A significantinteraction with age indicated that this positive association between mother-reported behaviorproblems and the CC-HOME was significant only at 36 months.

The final set of analyses in the HLM analyses was the analysis of whether the associationsbetween child outcomes and family and child-care variables were different depending onthe income level of the family. Interactions with family income were computed for all theassociations in the HLM analyses. Of the 35 interactions computed, only two were significant:one for caregivers’ age and children’s cognitive performance, and the other for noncompliancewith group size points and mother-reported child behavior problems. Thus, family income didnot moderate the associations indicated as significant in the main HLM analyses.

4. Discussion

To investigate the quality of care in the child-care homes in the NICHD Study, we posedthree overarching questions: are regulable factors, such as caregivers’ formal education andspecialized training and the number of children in the home, related to the quality of care inchild-care homes? Are nonregulable factors, such as the caregivers’ beliefs and the presence ofthe caregiver’s own children, related to quality of care in child-care homes? Are measures ofchildren’s development associated with the overall quality of observed care and with specificregulable and nonregulable features? We discuss our findings related to each of these questionsin turn.

4.1. Are regulable factors related to the quality of care in child-care homes?

Six regulable factors were considered in the study. Three were related to the caregivers’educational background (level of formal education, level of specialized training pertaining tochildren, and child-related training during the preceding year); two were related to the number

80 K.A. Clarke-Stewart et al. / Early Childhood Research Quarterly 17 (2002) 52–86

of children in the setting (the number of children enrolled and whether the number of childrenenrolled weighted by their ages was in compliance with recommended group size “points”);and the final factor was whether the setting was licensed by a government agency (state, county,or community).

In multivariate longitudinal analyses, controlling for family and child variation, these reg-ulable factors predicted both positive caregiving ratings, which focused exclusively on thecaregiver’s behavior with the study child, and the CC-HOME, which assessed the physical en-vironment, activities, and learning materials, as well as caregiver–child interaction. CC-HOMEscores were higher when caregivers were more educated, had higher levels of specialized train-ing, and had received child-related training during the previous year. Caregivers provided morepositive caregiving when they had higher levels of specialized training. These relations did notvary with children’s age, suggesting that these factors are equally important for toddlers andyoung preschoolers. These findings were predicted in the present study and are consistent withother research (Clarke-Stewart et al., 1994; Howes, 1983; Kontos et al., 1995). Taken together,the findings suggest that regulating caregivers’ training in child development could lead to im-proved quality of care. This suggestion was tested empirically in the Family-to-Family trainingprogram (Kontos et al., 1996). In that program, global quality scores in child-care homes im-proved after caregivers had participated in the training program. However, training did notaffect the observed emotional and sensitive quality of caregivers’ behavior. Not surprisingly, itappears that it is easier for caregivers to add stimulating materials, schedule interesting activ-ities, and organize the environment, than it is to change the nature of their behavior. Becauseof the consistency of the link between quality and training across these different studies, ef-forts to regulate caregiver training are likely to be worthwhile. Regulating caregiver educationby requiring that caregivers have at least a high school diploma could also be valuable. Thedifference on the CC-HOME between caregivers with and without a high school diploma wasslightly larger than one standard deviation (6 points at 15 and 24 months,SD = 5; 10 pointsat 36 months,SD= 8). The regulation of caregiver education might be particularly importantas children get older; the association between observed quality and caregiver education wasstronger at 36 months than at the younger ages.

Compliance with recommended standards for group size “points” was also, as predicted,significantly related to observed quality in the multivariate analyses. Although this approachhas been recommended by professionals in the area (Modigliani & Bromer, 1997) and makesintuitive sense, because younger children presumably require more attention than older ones,this weighted sum has been investigated in only one other study (Burchinal et al., 2002). Inthat study, group size points was not significantly associated with quality as assessed using theglobal FDCRS. We, too, failed to find a relation between compliance with recommended pointsand the global measure of quality, the CC-HOME. However, we did find that compliance withrecommended group size points was related to higher ratings of the caregiver’s positive care-giving. These findings are consistent with research showing that group size affects caregivers’interactions with individual children more strongly than it affects other aspects of the child-caresetting such as learning materials and activities (Clarke-Stewart et al., 1994; NICHD EarlyChild Care Research Network, 1996). Regulating compliance with an age-weighted groupsize cut-off may be more promising for ensuring quality care than is regulating the numberof children enrolled in the child-care home. The number of children attending or enrolled in

K.A. Clarke-Stewart et al. / Early Childhood Research Quarterly 17 (2002) 52–86 81

the child-care home did not uniquely predict observed quality; neither fewer children nor amoderate number of children was significantly related to observed quality of care when otherregulable factors were controlled.

Licensing was the final regulable feature considered in the present study. There has been adebate among policy makers and child-care professionals about whether licensing child-carehomes will result in higher quality care (Kontos, 1991). Although a link between licensingand child-care quality has been observed in some research (Burchinal et al., 2002; Goelman &Pence, 1987; Kontos et al., 1995), some investigators (Blau, 1999) have argued that licensingand regulations raise costs and do not substantially improve quality. In the present study,contrary to our prediction, we did not find that licensing was a unique predictor of observedquality when other regulable factors were controlled. Univariate analyses, however, revealedthat licensed settings received higher CC-HOME scores than unlicensed homes when thisfactor was analyzed separately. Moreover, caregivers in licensed settings were more likely tohave received training in the previous year, which also predicted higher CC-HOME scores. Itwould not be unreasonable to recommend or to require licensing of child-care homes or forparents to use licensing as one marker of better quality. However, the size of the differencein the CC-HOME scores related to licensing, although statistically significant, was small inabsolute terms (1.5 points at 15 months, 0.4 points at 24 months, and 3.2 points at 36 months).

In summary, the results pertaining to regulable factors and observed quality of care suggesta number of strategies that might be systematically tested as potential ways of improvingthe quality of child-care homes. Particularly promising avenues for regulation are educationand training standards for caregivers and group size cut-offs that take into account both thenumber and age of the children enrolled in the child-care home. To unequivocally determinethe effect of licensing, the next step should be to investigate, experimentally, the effects ofspecific licensing standards.

4.2. Are nonregulable factors related to the quality of care in child-care homes?

The second question posed in the present study was whether nonregulable features were re-lated to observed quality of the child-care homes. Six nonregulable features were considered—caregivers’ age, experience in the child-care field, professional orientation, beliefs about chil-dren, depressive symptoms, and own children present. Only one of these factors was related tochild-care quality: caregivers with more child-centered or nonauthoritarian beliefs about childrearing scored higher on the CC-HOME and received higher ratings of positive caregiving. Wehad predicted this association, based on prior research in child-care homes (Rosenthal, 1994)and families (NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 1999a; Palacios et al., 1992). Andit is particularly interesting that this was the single nonregulable factor that predicted higherquality care, because this variable was significantly related to caregivers’ education and train-ing (r = .34 and .40,p < .001). Thus, the finding supports our previous suggestion thatregulating caregiver education and training could help improve child-care quality. It suggeststhat caregivers develop their beliefs about children in large part through training and education,and that, therefore, requiring higher levels of education and training would most probably leadto more child-centered beliefs and, as a consequence, higher quality care as well. It is notsurprising that both caregivers and researchers who have relatively high levels of training and

82 K.A. Clarke-Stewart et al. / Early Childhood Research Quarterly 17 (2002) 52–86

education believe that it is better to let children express their initiative and individuality ratherthan imposing strict rules and repressive limits on their behavior. This is the “modern” way.

The results of mediational analyses (Baron & Kenny, 1986), in which we included bothregulable and nonregulable factors as predictors of observed quality of care, showed thatrelations between caregiving training and quality of care were no longer significant whencaregivers’ beliefs about child rearing were controlled. This suggests that caregivers’ beliefsmediate the effects of their training. This finding is consistent with the argument that specializedtraining influences child-care home providers’ beliefs, which, in turn, influence their behavioras caregivers. A promising direction for future research is the development of caregiver trainingprograms to test the effectiveness of this mediational model.

4.3. Does quality of care predict children’s development?

Our third research question was whether quality of care in child-care homes—measured byregulable features, nonregulable features, and observed quality—was related to children’s cog-nitive/language performance and cooperation and behavior problems as reported by caregiverand by mother, at three ages.

Results indicated that regulable features were associated with children’s cognitive devel-opment, but not with their social and behavioral development. Children whose caregivers hadhigher levels of education and had received specialized training during the past year scoredhigher on standardized cognitive and language assessments. The association with caregiver ed-ucation was significant even with nonregulable factors controlled. Follow-up analyses indicatedthat children’s cognitive performance was higher when their caregivers had attended college.Children with college-educated caregivers scored 4 points higher on the cognitive test at 24months and 7 points higher on the language test at 36 months. Extrapolating from the resultslinking caregiver education and quality of observed care, we expect that differences in childperformance would likely have been even greater if we had been able to compare caregiverswith and without a high school diploma. (We were not able to make this comparison becausethe sample size in analyses involving child outcomes was reduced to a point that these groupswere too small to compare statistically.) These findings are consistent with previous researchpublished by the NICHD Early Child Care Research Network (1999b), which focused onchild-care centers rather than child-care homes. In that work, children in centers in which care-givers had attended college displayed better preacademic skills and language comprehension.Children whose caregivers had specialized training at the college level also displayed betterpreacademic skills and language skills. These results, we believe, underscore the importanceof education and specialized training for child-care providers in all types of care settings.

Because of the limited amount of research relating nonregulable features to children’s de-velopmental outcomes, we did not pose specific hypotheses about these factors, and resultsof the study showed that child outcomes were not related to most of nonregulable factors wemeasured. Caregivers’ age, experience, professionalism, beliefs, and own child present in thechild-care home were not related to child outcomes. There was just one significant link: Care-givers who were more depressed reported that the children in their care were less cooperativeand had more behavior problems. These caregiver ratings may reflect several processes. Care-givers who are depressed may view children through more negative eyes. A child who is rated

K.A. Clarke-Stewart et al. / Early Childhood Research Quarterly 17 (2002) 52–86 83