Disengagement in work-role transitions

-

Upload

uni-muenster -

Category

Documents

-

view

4 -

download

0

Transcript of Disengagement in work-role transitions

Disengagement in work-role transitions

Cornelia Niessen1*, Carmen Binnewies2 and Johannes Rank11Work and Organizational Psychology Unit, Department of Psychology,University of Konstanz, Germany

2Work and Organizational Psychology Unit, Johannes Gutenberg-University ofMainz, Germany

The present study examines whether disengagement from previous work-rolespositively predicts adaptation to a new work-role (here, becoming self-employed) byreducing negative consequences of psychological attachment to these previous roles.Disengagement involves an individual’s effort to release attention from thoughts andbehaviours related to the previous work-role. A three-wave longitudinal studyinvestigated the relationship between psychological attachment (measured as affectivecommitment) to a prior work-role, disengagement from the prior work-role, andadaptation to a new work-role [pursuit of learning, fit perceptions with self-employment, task performance over time]. Participants included 131 persons whorecently founded a small business. Results indicated that psychological attachment tothe past work-role was negatively related to pursuit of learning and fit with the newwork-role. Disengagement from the past work-role was positively related to pursuit oflearning in the new work-role, and buffered the negative relationship betweenpsychological attachment and fit as well as task performance.

Today’s work environment is dynamic and rapidly changing, accompanied by

fundamental changes in the nature of careers (e.g., Donohue, 2007; Hall & Mirvis,

1995). Many individuals change their jobs at least once in their lifetime – because of

personal choice or because of organizational changes. Job changes typically involve

individuals having to adapt to the requirements of the new work-role (e.g., Allen & van

de Vliert, 1984; Meyer, Allen, & Topolnytsky, 1998; Nicholson, 1984; Nicholson & West,1989), defined by the total set of work responsibilities associated with a person

(cf. Ilgen, 1994). Some researchers argue that the transition from the previous job to a

new job also requires disengagement from the prior work-role (Allen & van de Vliert,

1984; Nystrom & Starbuck, 1984), especially when psychological attachment to the

prior work-role has persisted for some time (Meyer et al., 1998). It seems likely

that emotional ties to the prior work-role hinder the adjustment to the new work-role.

* Correspondence should be addressed to Dr Cornelia Niessen, Work and Organizational Psychology Unit; Department ofPsychology, University of Konstanz, Postbox D42, D-78457 Konstanz, Germany (e-mail: [email protected]).

TheBritishPsychologicalSociety

695

Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology (2010), 83, 695–715

q 2010 The British Psychological Society

www.bpsjournals.co.uk

DOI:10.1348/096317909X470717

For example, individuals with a strong psychological attachment to their prior job

may often think back and reference their prior job, which in turn distracts them

from exploring their new work-role, solving problems, and coping with stress in

the new work-role. Therefore, the main objectives of the present study were

to examine (1) whether psychological attachment to a previous work-role relates to

adjustment to a new work-role and (2) whether disengagement buffers the negativeconsequences of psychological attachment to the previous role on adjustment to a new

work-role.

In recent years, research has increasingly recognized that adjustment to new work

requirements is an important component of work performance (Allworth & Hesketh,

1999; Dawis, 2005; Dawis & Lofquist, 1984; Griffin, Neal, & Parker, 2007; Pulakos,

Donovan, & Plamondon, 2000; Pulakos et al., 2001). Research on adjustment is

mainly directed towards the question of how individuals deal with the new work-role

demands (Ployhart & Bliese, 2006; Pulakos et al., 2000, 2001). However, howpersons disengage from ties that bind them to their previous work-roles has been

largely ignored. Generally, disengagement from an old work-role refers to mechanisms

that dissolve and uncouple cognitive and emotional attachment to a work-role

(Allen & van de Vliert, 1984; Kahn, 1990). More specifically, in the present study we

concentrate on active disengagement as a self-regulatory behaviour. Active

disengagement involves an individual’s effort to release attention from thoughts

and behaviours related to the previous work-role. Understanding disengagement as an

important adaptive process is both of theoretical and of practical interest. Becausemost research examines how individuals cope with new work-roles (e.g., Allworth &

Hesketh, 1999; Dawis, 2005; Pulakos et al., 2000, 2001), it is of theoretical interest

whether adjustment can be more fully understood if we additionally consider

disengagement processes. From a practical perspective, individuals must be able to

overcome negative influences of their past experiences that may distract them from

concentrating fully on their new role demands in order to perform successfully in the

new work-role.

Research on work-role transitions has focused mainly on transitions to new jobswithin the same company (e.g., Nicholson, 1984; West, 1987), transitions to a new

organization (e.g., Bauer, Morrison, & Callister, 1998; Fisher, 1986; Louis, 1980;

Schein, 1971; Van Maanen & Schein, 1979), or on cross-cultural work changes (e.g.,

Harrison, Chadwick, & Scales, 1996; Ward & Chang, 1997; Ying, 2002). Little

attention has been devoted to the transition from being an employee to becoming

self-employed. Creating a new business often requires orientation, knowledge, skills,

and abilities (KSAs) which are different from those required by an employee in an

organization (Baum, Frese, & Baron, 2007). For example, Krauss, Frese, Friedrich, andUnger (2005) showed that the work-role of a self-employed person requires high

levels of personal initiative, achievement orientation, and risk taking orientation

compared to employment in an organization (see also, Covin & Slevin, 1991;

Schumpeter, 1934). Thus, moving into self-employment often implies a salient work-

role change.

The present paper is organized as follows. First, we briefly present our theoretical

framework of adjustment to a new work-role. Second, we propose a direct negative

relationship between psychological attachment to the past work-role and adaptation tothe new work-role. Finally, we argue that actively releasing attention from thoughts and

behaviours related to the previous work-role (i.e., disengaging) buffers the negative

consequences of being attached to the previous work-role.

696 Cornelia Niessen et al.

Adjustment to a new work-roleGenerally, adjustment reflects the degree to which individuals cope with, respond to,

and/or support changes that affect their roles (Griffin et al., 2007; see also Chan, 2000;

Dawis, 2005; Yeatts, Folts, & Knapp, 2000). When examining adjustment, our study

draws on a person–environment (P–E) fit theory named the Minnesota theory of work

adjustment (TWA; Dawis, 2005; Dawis & Lofquist, 1984), which specifies a variety ofindicators of adjustment. The TWA proposes that individuals initiate adaptation when

they recognize a misfit of their KSAs, needs, and values with the requirements and

supplies of the work context. Two modes of adaptive behaviour are distinguished. First,

the reactive mode refers to the individual changing him- or herself to achieve fit with

the work environment (e.g., learning). Second, the active mode involves changing the

environment to reduce the misfit between the individual and environment (e.g., role

innovation; West, 1987). A good fit between person and environment results in an

individual’s increased satisfaction and performance, and in organizational tenure as along-term consequence (Dawis, 2005; Dawis & Lofquist, 1984).

To investigate adjustment to a new work-role, we followed the TWA and measured

three indicators of adaptation evolving over time, namely pursuit of learning, fit, and

task performance. In particular, we used a longitudinal study design and considered

changes in pursuit of learning, fit, and task performance which occurred over 1 month

as the main dependent variables. In concordance with the TWA, these changes in the

outcome variables should indicate successful adaptation. We expected pursuit of

learning, fit, and performance to changeover the period of 1 month because in the start-up phase of founding a new business, individuals have to deal with several new work

demands (e.g., developing marketing plans) and consequently have to learn new things

while also improving their performance (Baum et al., 2007). Thus, during this phase

there is a high need for adaptation to the new work-role.

Pursuit of learningThe TWA proposes that individuals initiate adaptive behaviours when they recognize a

misfit with the newwork requirements. Several studies have shown that learning is a key

adaptive behaviour (e.g., Allworth & Hesketh, 1999; Pulakos et al., 2000, 2001; West,

1987). For example, when a motor-car mechanic becomes self-employed by working inhis or her own garage, then he or she is faced with new tasks such as advertising, billing

customers, and restocking. Active engagement in learning the new tasks should help

this individual to perform well in the new work-role. In the present study, we examine

one’s search for learning opportunities and one’s engagement in learning activities,

namely pursuit of learning (Frese, Kring, Soose, & Zempel, 1996; London &Mone, 1999;

Niessen, 2006; Sonnentag, 2003), as one indicator of adaptation.

FitGenerally, fit refers to the compatibility between a person (e.g., abilities, needs, values)

and the environment (e.g., job demands, supplies; Cable & Parsons, 2001). Research on

P–E fit has focused mainly on the organizational socialization of employees (e.g., Cable &Parsons, 2001; Kristof-Brown, 2000). Here, studies have shown that achieving a match

with the work-role is positively related to important work outcomes such as job

satisfaction (Lauver & Kristof-Brown, 2001), organizational commitment (Cable &

Judge, 1996), and low intentions to quit (Saks & Ashforth, 1997). One important aspect

Disengagement in work-role adjustment 697

of fit is the fit between a person’s work values and the work environment’s values

(Kristof, 1996). In the present study, we focused on value congruence between

the preference of a person and the role of self-employment. For many individuals,

creating a new business often means a change from comfort-related values as an

employee in an organization to change-related values associated with proactivity,

autonomy, achievement orientation, etc. (e.g., Covin & Slevin, 1991; Krauss et al.,2005; Schumpeter, 1934). Therefore, we assume that change in the fit between the

person and self-employment over time is an important indicator of adaptation to self-

employment.

Task performanceAccording to Motowidlo and Van Scotter (1994) task performance includes two aspects

of behaviours. One consists of the proficient execution of the technical core processes

of an organization such as repairing a car or cutting hair. The other aspect refers to

activities that support the technical requirements (e.g., replenishing supplies of raw

materials, planning, supervising, and staff functions) that enable the organization tofunction effectively and efficiently; p. 476). We argue that when individuals become self-

employed they might experience an increase in responsibilities such as replenishing

supplies, supervising, and coordinating. Thus, an improvement in task performance

after transition is an important indicator of successful adaptation.

Psychological attachment to the prior work-role, disengagement, and adaptationWe propose that attachment to the prior work-role is negatively related to adaptation to

the new work-role (pursuit of learning, fit, and task performance in the new work-role

over time). In addition, we argue that disengagement from the previous work-role

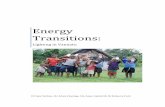

moderates these negative relationships by buffering the negative effect of psychologicalattachment to the prior work-role on adaptation. The model underlying the study is

illustrated in Figure 1.

Psychological attachment to the prior work-roleMeyer et al. (1998) suggested that when a work-role is left, psychological attachment to

this prior work-role may persist for some time. In line with other research (e.g., Burris,

Detert, & Chiaburu, 2008), we conceptualize psychological attachment as affective

commitment, which refers to the emotional attachment to, identification with, and

involvement in a target (Solinger, van Olffen, & Roe, 2008) such as an organization,

Psychologicalattachment

Pursuit of learning

Fit

Task performance

Disengagement

Figure 1. Main concepts and the hypothesized relationships between the study variables.

698 Cornelia Niessen et al.

work-group, or work-role (Meyer, Allen, & Smith, 1993). Feelings of affective

commitment are developed by the experience of support, fair treatment, appreciation,

personal importance, and competence (Solinger et al., 2008). In contrast to past

research on psychological attachment and affective commitment that assessed bonds to

the present work-role, we focused on psychological attachment to the prior work-role

and its potentially negative relationship with adjustment to the new role.We propose that psychological attachment to the prior work-role is negatively

related to pursuit of learning for two reasons. First, psychological attachment may

consume resources which are needed to pursue learning. Psychological attachment to

the prior work-role may invoke in individuals thoughts of the prior work-role, and

tendencies to compare and evaluate the new work-role accordingly. This, in turn, may

harness resources which are needed to search for learning opportunities and to engage

in learning activities. There is evidence that pursuit of learning requires additional effort

(Sonnentag, 2003).Second, when persons are psychologically attached to their prior work they may still

identify with their prior work-role’s goals and values (Porter, Steers, Mowday, & Boulian,

1974), feel a sense of pride towards the prior work-role, and think positively about it

(Meyer & Allen, 1997). Thinking about the prior work-role may also involve negative

emotions such as regret. Emotions tend to redirect behaviour from ongoing goal pursuit

to immediate requirements of the emotional situation (Beal, Weiss, Barrios, &

MacDermid, 2005; Brown, Westbrook, & Challagalla, 2005; Weiss & Cropanzano, 1996).

Thus, individuals may be distracted from enhancing their pursuit of learning. Based onthese assumptions, we propose the first hypothesis.

Hypothesis 1: Psychological attachment to the prior work-role will be negatively related topursuit of learning in the new work-role over time.

Further, we propose that fit with self-employment will be negatively affected when

individuals have a strong psychological attachment to the prior work-role because

individuals experience changes in values when they become self-employed. Researchhas shown that individuals are more attached to their workplaces when they experience

a comfort-related work environment which permits regularities in time and place of

work, provides job security, clear-cut rules and procedures, role clarity, and non-stressful

working conditions (Meyer, Irving, & Allen, 1998). However, self-employment provides

less prescribed procedures suggesting how to handle the new tasks. Consequently,

persons with a strong psychological attachment to their prior work-role may experience

lower value congruence, which in turn may lower their motivation to achieve an

increasing fit with the new work-role.

Hypothesis 2: Psychological attachment to the prior work-role will be negatively related to fitwith the new work-role over time.

We also assume a negative relationship between psychological attachment to the

prior work-role and task performance in the new work-role. Specifically, we argue that

psychological attachment to the prior work-role fosters active memory recall

(i.e., thinking back on the prior role), which, in turn, distracts from task

accomplishment. Moreover, there is evidence that distractions such as active memory

recall to the prior work-role can generate additional distracting thoughts (Klinger, 1996;

Yee & Vaughan, 1996), which require attentional resources that would normally be

needed for fulfilling requirements of the new work-role (e.g., Martin & Tesser, 1996;

Disengagement in work-role adjustment 699

Thompson, Webber, & Montgomery, 2002). Active memory recall can also be

accompanied by emotions, which, in turn, negatively influence task performance.

Research on emotions revealed that emotions can interrupt goal-directed behaviour,

which is associated with lower performance (Beal et al., 2005; Brown et al., 2005; Weiss

& Cropanzano, 1996). Thus, psychological attachment to the prior work-role should

distract from and interrupt the focus on the new work-role, which may impair taskperformance in the new work-role. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: Psychological attachment to the prior work-role will be negatively related to taskperformance in the new work-role over time.

The role of disengagement in the adaptation processDisengagement is a broad concept that is studied in different research areas. Kahn

(1990) stated that persons uncouple themselves from work-roles when certain

psychological conditions (e.g., psychological safety) are insufficient. Research on goal-

striving emphasizes disengagement as dissolving commitment to a goal according to

personal or situational constraints (Brandtstadter & Rothermund, 2002; Heckhausen &

Schulz, 1995; Wrosch, Scheier, Carver, & Schulz, 2003). Research on stress management

examines disengagement as one strategy for coping with stress. Here, suppression of

competing activities as an active coping strategy helps one to concentrate fully on thechallenge or threat at hand (Brown et al., 2005; Carver, Scheier, &Weintraub, 1989). In a

similar vein, cognitive psychological research has revealed that actively ignoring and

forgetting previously learned material supports learning of new items (Hasher, Zacks, &

May, 1999; Zacks & Hasher, 1994).The present study concentrates on active disengagement as a self-regulatory

process. Active disengagement refers to an individual’s effort to release attention from

and to suppress thoughts and behaviours related to the previous work-role. This self-

regulatory process is different from being attached to a work-role. Attachment refers tothe emotional ties to the work-role, whereas disengagement aims at regulating thoughts

and behaviours that relate to the previous work-role. We propose that disengagement

attenuates the negative relationship between psychological attachment to the previous

work-role and adaptation to the new work-role.

Disengagement should buffer the negative impact of emotional ties to the prior

work-role and pursuit of learning, fit as well as task performance for two reasons. First,

by releasing attention from the prior work-role, individuals prevent themselves from

dwelling on potential loss, thus becoming more ‘free’ and open to the new role. Forexample, Brown et al. (2005) showed that inhibition of irrelevant thoughts and

behaviours (self control) buffered the negative relationship between negative emotions

and performance. We assume that repressing thoughts and behaviours related to the

prior role should help to reduce the spillover of emotions to the new work-role.

Second, suppression of thoughts and behaviours should help individuals to remain

focused on the new work-role because restraining emotions related to the previous

work-role helps persons to fully concentrate on the new role without redirecting and

binding attention (e.g., Beal et al., 2005). Then, persons may maintain concentration onthe tasks needed to fulfil job requirements (Hirst & Kalmar, 1987; Weiss & Cropanzano,

1996), and may find new ways to overcome and solve problems at hand. Thus, to the

extent that individuals disengage from the previous role, the negative effects of still

being attached to the prior role should be reduced, and individuals should remain

700 Cornelia Niessen et al.

focused on the new work-role. Among individuals high in disengagement, psychological

attachment to the prior work-role should be less detrimental to enhancements in

learning, fit and performance than among individuals low in disengagement.

Consequently, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 4: Disengagement will attenuate the negative relationship between psychologicalattachment to the prior work-role and pursuit of learning in the new work-role over time.

Hypothesis 5: Disengagement will attenuate the negative relationship between psychologicalattachment to the prior work-role and fit with the new work-role over time.

Hypothesis 6: Disengagement will attenuate the negative relationship between psychologicalattachment to the prior work-role and task performance in the new work-role over time.

Method

Participants and procedureParticipants of this study were founders of new, small businesses in southern Germany.

Participants were randomly chosen from lists provided by the local Chamber of

Commerce. The registration of enterprises at the Chamber of Commerce is mandatory

in Germany. Participants had to meet four criteria. First, participants had to be first-timefounders and owners of the business. Second, they had to work at least 20 h a week. By

using these criteria, we included only those individuals who built up their business on

their own. Third, in order to examine individuals in the transition process, the business

had to be in operation for a maximum of 2 years. In general, the first 2 years are seen as

the starting phase in which persons have to learn to function as effective managers of

their own businesses (Baron, 2007). Finally, the business had to be an independent

business and not a branch of an existing business.

Founders were contacted by phone. When they fulfilled the study’s criteria andagreed to participate, three questionnaires at time intervals of 1 month were sent out by

mail to 333 entrepreneurs. By request, 53 of 333 persons received the questionnaires via

e-mail. A lottery prize (200 Euro) was offered to participants who completed all three

surveys. The first survey included questions about affective commitment to the previous

workplace and demographic data. A total of 246 usable surveys were returned (response

rate ¼ 73:80%), including 37 questionnaires which were returned by e-mail. To examineadjustment, participants had to fill in two further questionnaires within a time lag

of 1 month. A total of 191 founders returned the questionnaire at Time 2 (78% ofTime 1 participants), and 164 founders completed the questionnaire at Time 3 (67%

of Time 1 participants). Thirty-three questionnaires could not be matched to the Time 1

questionnaires. In sum, analyses were based on complete sets of data from 131 persons.

Average age of participants was 38.8 years (SD ¼ 9:8 years) ranging from 18 to

66 years. Forty-nine persons (37.7%) were female. On average, participants had 13.1

years of work experience at their previous job (SD ¼ 9:8 years). Three persons had noformal education (2.3%), 59.5% had finished vocational training, 14.5% were technicians

with a diploma or similar degree, and 22.3% had a university degree. The average age ofthe newly founded businesses was 6.7 months (SD ¼ 3:4 months).

Seventy-four (57%) of all founders had no employees. The sample included a variety

of industries: agricultural, fishing and mining (3.8%), technical (18.5%), manufacturing

(5.4%), and service (72.3%).

Disengagement in work-role adjustment 701

MeasuresAt Time 1, affective commitment to the previous role and demographics were measured.

At Time 2, disengagement, work engagement, pursuit of learning, fit, and performance

were assessed. Pursuit of learning, fit, and performance were measured again 1 month

later (Time 3).

Psychological attachment to the prior work-roleAt Time 1, the respondents provided a current rating of their psychological attachment

in their last workplace. Similar to Burris et al. (2008), we assessed psychological

attachment with seven items from Allen and Meyer’s (1990) measure of affective

commitment. Using this scale, participants provided an assessment of their

psychological attachment in their prior work. Because we focused on affective

commitment to the prior work-role rather than to the prior organization, items were

slightly altered. Sample items were ‘I do not feel emotionally attached to my prior work’(originally: to this organization); (reversed scored), ‘My previous work (originally: this

organization) had a great deal of personal meaning for me’, and ‘I did not feel a strong

sense of belonging to my previous work’ (originally: my organization) (reverse coded).

The scale ranged from 1 ¼ not at all to 5 ¼ a great deal. Cronbach’s alpha was .76.

Disengagement from prior work-roleDisengagement was assessed by four items based on the suppression of competing

activities scale of Carver et al. (1989). Items were slightly adapted for use in the presentstudy. Items were ‘I keep myself from getting distracted by thoughts of my previous

work’ (original: ‘thoughts and activities’); ‘I put aside all memories to my previous work

in order to concentrate on my self-employment’ (originally: ‘I put aside other activities

in order to concentrate on this’), and ‘I try hard to prevent thoughts about my previous

work interfering with my efforts at dealing with problems related to my self-

employment’ (originally: ‘I try hard to prevent other things from interfering with my

efforts at dealing with this’). The scale ranged from 1 ¼ not at all to 5 ¼ a great deal.

The reliability of the scale was .78 at Time 2.An exploratory factor analysis was conducted on items of the psychological

attachment and disengagement scales using a principle components analysis with

varimax rotation. Results revealed a two-factor solution. The two factors explained over

53% of the variance. Factor loadings ranged from .62 to .82 for psychological attachment

and from .69 to .78 for disengagement.

Pursuit of learningPursuit of learning was assessed with five items adopted from VandeWalle’s (1997)learning goal orientation scale (cf. Sonnentag, 2003). Participants were instructed to

answer the items with respect to the last month. Five-point rating scales were used

ranging from 1 ¼ not true at all to 5 ¼ very true (sample item: ‘I looked for

opportunities to develop new skills and knowledge’). Cronbach’s alpha was .90

(Time 2), and .91 (Time 3).

702 Cornelia Niessen et al.

FitRespondents were asked to indicate on five-point scales, ranging from 1 ¼ not at all to

5 ¼ a great deal, how well they perceived their fit with the values and culture of self-

employment. The scale included three items based on the person–organization fit

measure of Cable and DeRue (2002). Items were adapted to measure value congruence

with self-employment. The items were: ‘The things that I value in life are very similar tothe things that self-employment provides’ (originally: ‘The things that I value in life are

very similar to the things that my organization values’), ‘My personal values match self-

employment’s (originally my organization’s) values and culture’, and ‘Self-employment’s

(originally: my organization’s) values and culture of self-employment provide a good fit

with the things that I value in life’. Participants were instructed to answer the items with

respect to the last month. The reliability of the scale was .85 at Time 2 and .88 at Time 3.

Task performanceTask performance was assessed with six items based on the in-role performance

measure by Williams and Anderson (1991). Again, items were adapted for the study’scontext, and participants were instructed to answer the items with respect to the last

month. A sample item is: ‘I meet the new requirements and duties very quickly’. Five-

point scales ranged from 1 ¼ not at all to 5 ¼ a great deal. Cronbach’s alpha was .85

at Time 2 and .81 at Time 3.

For pursuit of learning, fit, and task performance at Time 2 and Time 3 exploratory

factor analyses were conducted using principle components analyses with varimax

rotation. At both times, results revealed a three-factor solution explaining at Time 2

67.32% and at Time 3 69.62% of the variance. At Time 2, factor loadings ranged from .78to .92 for pursuit of learning, from .76 to .90 for fit, and from .72 to .80 for task

performance. At Time 3, factor loadings ranged from .79 to .89 for pursuit of learning,

from .85 to .86 for fit, and from .71 to .81 for task performance.

Control variablesAge of business, work engagement in the new role, prior employment status, gender,

and length of job experience were included as control variables. We assumed that,

particularly in the beginning of starting a new business, founders compare their new

work with their experiences at their previous work, and subsequently have to disengage

from them. The longer a person works and creates experiences in a new business, the

less salient their experiences with any previous job will be. Thus, we controlled for ageof business.

Second, we controlled for tenure in the last job because psychological attachment to

a prior work-role probably differs with length of job experience. Individuals who stayed

only a short time in their prior job might feel less psychologically attached to it than

individuals who remained for years at their previous jobs before becoming self-

employed. In line with this reasoning, Beck and Wilson (2000) showed that affective

commitment is related to job experience.

The third control variable was previous employment status, which might point todifferent motivational orientations when founding a new venture. It was coded as

follows: (0) ¼ employed and (1) ¼ unemployed. Starting a business after unemploy-

ment may indicate a reaction to an individual crisis (the loss of a job) and a dominance of

push factors. Starting a business generally is regarded as proactive in areas such as

Disengagement in work-role adjustment 703

gaining personal independence and obtaining better income opportunities. Thus,

founders who were previously in a role as an employee should be more motivated by

these pull factors (e.g., Hinz & Jungbauer-Gans, 1999) compared to individuals who

were unemployed before funding their own business.

We controlled for gender because research has shown that women entrepreneurs

have similar resources as male entrepreneurs but that their levels of success differ(Runyan, Huddleston, & Swinney, 2006). Moreover, studies have shown that male

entrepreneurs report a higher career and achievement orientation than women

(e.g., DeMartino, Barbato, & Jacques, 2006). Thus, in the present study we controlled for

potential motivational differences between men and women, which might influence the

relationships with pursuit of learning, fit, and task performance. Gender was coded as

follows: (1) ¼ women and (2) ¼ men.

Finally, we controlled for work engagement in the new work-role (cf. Schaufeli,

Salanova, & Gonzalez-Roma, 2002). Here, work engagement reflects how stronglyindividuals were already involved with their new work-role. By including work

engagement as a control variable, we preclude that negative relationships between

psychological attachment and adaptation are simply due to low levels of engagement in

the new work-role. Work engagement was assessed by nine items of the work

engagement scale of Schaufeli et al. (2002). The scale ranges from 1 ¼ not at all to

5 ¼ a great deal. Sample items were: ‘I am enthusiastic about my work’, and ‘I feel

happy when I am working intensely’. Cronbach’s alpha was .83 at Time 2.

Results

Table 1 shows the means, standard deviations, correlations, and coefficient alphas of the

main study variables. Hypotheses were tested by multiple hierarchical regression

analyses. Predictor and moderator were z-standardized. In the first step, we controlled

for the potential effects of the age of the business, work engagement in the new role,prior employment status, gender, length of job experience, and the outcome variable at

Time 2. In the next steps, the predictor variables and the moderator variable were

included. The interaction effects were examined in the last step.

Hypothesis 1 stated that psychological attachment to the prior work-role (Time 1)

would be negatively related to pursuit of learning over time (change from Time 2 to

Time 3). As expected, a high degree of psychological attachment to the prior work-role

was negatively associated with an increase in pursuit of learning (see Step 2, Table 2).

Hypothesis 2 predicted a negative relationship between psychological attachment tothe prior work-role and fit over time. As can be seen in Step 2 of Table 3, psychological

attachment negatively and significantly predicted fit over time. Hypothesis 3 stated that

psychological attachment to the prior role would be negatively associated with task

performance in the new work-role over time. Analysis revealed that psychological

attachment to the former work-role was not related to performance at Time 3,

controlling for performance at Time 2 (see Step 2 in Table 4). Thus, Hypotheses 1 and 2

were supported, but Hypothesis 3 was not.

We tested whether disengagement buffered the negative relationship betweenpsychological attachment and pursuit of learning (Hypothesis 4). There was no

significant interaction between psychological attachment and disengagement in

predicting pursuit of learning in the new work-role (Step 3, Table 4). Thus, Hypothesis 4

was not supported. However, we found a direct positive relationship between

704 Cornelia Niessen et al.

Table

1.Intercorrelationsbetweenvariables,theirmeans,standarddeviations,andalphacoefficients

MSD

12

34

56

78

910

11

12

13

14

15

16

1.Age

ofbusiness

6.75

3.41

–

2.Engagement

3.88

0.63

.17*

(.83)

3.Employm

entstatus

0.47

0.50

.03

2.07

–

4.Gender

––

2.08

2.05

.13

–

5.Lengthofprevious

jobtenure

5.04

4.90

.17*

2.11

2.13

2.15

–

6.Psychological

attachment

(priorwork-role)

3.10

0.82

2.23**

.08

2.09

2.01

.29**

(.76)

7.Disengagement

3.52

0.96

2.05

.01

2.03

.18*

2.03

.25*

(.78)

8.PursuitoflearningT2

3.70

0.71

2.05

.34**

2.08

.15

2.17

.01

.26**

(.90)

9.FitT2

3.98

0.68

.20*

.33**

2.08

2.01

.07

2.02

.11

.30**

(.85)

10.Task

perform

ance

T2

4.18

0.53

.16

.44**

2.08

2.03

.03

.03

.11

.18*

.38**

(.85)

11.PursuitoflearningT3

3.65

0.78

2.01

.42**

2.01

.20*

2.14

2.19*

.36**

.67***

.38**

.30**

(.91)

12.FitT3

3.76

0.71

.23**

.35**

2.11

.08

.04

2.09

.08

.26**

.59**

.30**

.41**

(.88)

13.Task

perform

ance

T3

4.13

0.57

.21*

.38**

.02

2.06

.02

2.04

.15

.20*

.17

.68**

.34**

.29**

(.81)

14.Pursuitoflearning

(T3–T2)

0.032

0.61

2.50

2.14

2.10

2.09

.02

.24*

2.17*

.33**

2.17*

2.18*

.49**

2.23*

2.18*

–

15.Fit(T3–T2)

0.010

0.67

2.04

2.06

.05

2.09

.02

.09

.03

.03

.43**

2.07

2.05

2.48**

2.15

.08

2

16.Task

perform

ance

(T3–T2)

0.034

0.44

2.08

2.05

2.15

2.06

.02

.07

2.06

2.05

.22*

.34**

2.06

2.03

2.46**

.01

.27**

2

Note.Allscales

wereansw

ered

onfive-pointscales.[Ingeneral,a

higher

score

indicates

ahigher

value];N

,131;employm

entstatuswas

coded:ð0

Þ¼em

ployed

and

ð1Þ¼

unem

ployed,gender

was

coded:ð1Þ

¼wom

enandð2Þ

¼men.*p

,:05;**p,

:01;***p

,:001.

Disengagement in work-role adjustment 705

disengagement and pursuit of learning: when disengagement was high, individuals

reported an increase in pursuit of learning.

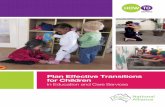

In line with Hypothesis 5, we found a highly significant interaction between

psychological attachment to the prior work-role and disengagement on fit with the new

work-role (see Step 3, Table 3). To examine the pattern of this interaction, we calculated

simple slopes of the psychological attachment – fit relationship for a low (21 SD) and

Table 2. Results from hierarchical regression analysis predicting pursuit of learning from Time 2 to

Time 3

Pursuit of Learning

Step and variables entered 1 2 3 4

1. Age of business 2 .01 .03 .03 .03Engagement .23*** .24*** .25*** .26***Employment status .04 .03 .04 .03Gender .10 .11 .09 .10Length of previous job tenure 2 .02 .04 .03 .03Pursuit of learning T2 .56*** .57*** .53*** .53***

2. Psychological attachment (prior work-role) 2 .22*** 2 .18** 2 .18**3. Disengagement T2 .17* .17*4. Psychological attachment £ disengagement T2 .01R2 .49*** .54*** .56*** .56***F (R2) 20.02 20.30 19.43 17.14DR2 .04*** .02** .001F (DR2) 11.63 6.73 .05

Note. The displayed coefficients are standardized beta weights at each step; *p , :05; **p , :01;

***p , :001.

Table 3. Results from hierarchical regression analysis predicting fit from Time 2 to Time 3

Fit

Step and variables entered 1 2 3 4

1. Age of business .09 .12 .12 .16*Engagement .19* .21** .21* .27***Employment status 2 .06 2 .07 2 .07 2 .11Gender .08 .08 .08 .15*Length of previous job tenure .09 .13 .13 .15*Fit T2 .47*** .45*** .45*** .43***

2. Psychological attachment (prior work-role) 2 .17* 2 .17* 2 .21**3. Disengagement T2 2 .01 2 .054. Psychological attachment £ disengagement T2 .20**R2 .39*** .42*** .42*** .45***F (R2) 13.48 12.72 11.05 11.10DR2 .025* .001 .030**F (D R2) 5.33 .02 7.10

Note. The displayed coefficients are standardized beta weights at each step; *p , :05; **p , :01;

***p , :001.

706 Cornelia Niessen et al.

a high (þ1 SD) level of disengagement (Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, 2003). The

interaction is plotted in Figure 2. Analyses of simple slopes revealed that the relationship

between psychological attachment to the prior work-role and fit with the new role over

time was negative when disengagement was low (b ¼ 20:30, SE ¼ 0:089, t ¼ 3:353,p ¼ :001). There was no relationship between psychological attachment and fit when

Table 4. Results from hierarchical regression analysis predicting task performance from Time 2 to

Time 3

Task performance

Step and variables entered 1 2 3 4

1. Age of business .06 .08 .08 .11Engagement .03 .03 .03 .08Employment status .08 .07 .07 .04Gender 2 .001 .002 2 .01 .04Length of previous job tenure .03 .06 .06 .08Task performance T2 .72*** .72*** .71*** .69***

2. Psychological attachment (prior work-role) 2 .11 2 .08 2 .123. Disengagement T2 .08 .064. Psychological attachment £ disengagement T2 .15*R2 .55*** .56*** .56*** .58***F (R2) 21.68 19.09 16.93 15.90DR2 .01 .01 .016*F (DR2) 2.24 1.38 3.80

Note. The displayed coefficients are standardized beta weights at each step; *p , :05; **p , :01;

***p , :001.

1

1.5

2

2.5

3

3.5

4

4.5

5

Low psychologicalattachment

High psychologicalattachment

Fit

Low disengagement

High disengagement

Figure 2. Two-way interaction between psychological attachment and disengagement predicting fit

over time (Hypothesis 5).

Disengagement in work-role adjustment 707

disengagement was high (b ¼ 20:012, SE ¼ 0:062, t ¼ 0:192, p ¼ :848). Thus,

Hypothesis 5 was supported.

As expected in Hypothesis 6, disengagement from the previous work-role

significantly moderated the relationship between psychological attachment and task

performance over time (see Table 4, Step 4). Figure 3 displays the pattern of this

interaction. Simple slope analysis revealed that the relationship between psychologicalattachment and fit over time was negative when disengagement was low (b ¼ 20:126,SE ¼ 0:05, t ¼ 2:52, p ¼ :013), but there was no relationship when disengagement washigh (b ¼ 0:008, SE ¼ 0:05, t ¼ 0:16, p ¼ 0:873). Thus, Hypothesis 6 was supported.

We also tested the six hypotheses without controlling for the T2 outcome and found

the same results as in prior analyses. Thus, results from hierarchical regression analyses

are in line with the results of the analyses predicting the change in the outcome

variables. The tables are available on request.

Discussion

The present study examined (1) whether psychological attachment to a previous work-

role related to adjustment to a new work-role, and (2) whether disengagement buffered

the negative effect of psychological attachment to a prior work-role on adjustment to

the new work-role. Overall, the results supported the idea that both attachment to the

prior work-role and disengagement as a self-regulatory behaviour play important roles in

work adjustment.

As expected, psychological attachment to the prior work-role was negatively related

to pursuit of learning and fit with the new work-role over time. This result is in line withour reasoning that individuals who are still highly attached to their prior work-role are

1

1.5

2

2.5

3

3.5

4

4.5

5

Low psychologicalattachment

High psychologicalattachment

Low disengagement

High disengagement

Per

form

ance

Figure 3. Two-way interaction between psychological attachment and disengagement predicting

performance over time (Hypothesis 6).

708 Cornelia Niessen et al.

distracted by thinking about the previous work-role and less motivated to learn and to

achieve a fit with their new work-role. However, we found no relationship between

attachment and task performance. It might be that distraction has more subtle

consequences such as lowering motivation for contextual performance rather than for

task performance and that it does not impact performance of core tasks (e.g., Hockey,

1997). Studies have shown that task performance remains remarkably stable across awide range of other work conditions like stress or high workload because of several

compensatory processes such as increasing effort (e.g., Hockey, 1997).

The present study supported the assumption that disengagement from the prior

work-role moderates the relationship between psychological attachment and fit as well

as performance over time. When persons actively avoid thinking back to the prior work-

role, it is more likely that maladaptive thoughts and behaviours are interrupted.

Consequently, individuals may concentrate more fully on the accomplishment of the

new tasks and prevent themselves from dwelling on the loss, thus becoming more ‘free’and open to the new role.

Our results suggest that the adaptation process can be more fully understood if we

consider disengagement processes in the analysis. Previously, the TWA and other

theoretical frameworks (e.g., Nicholson, 1984) as well as empirical approaches (e.g.,

Pulakos et al., 2000) mainly focused on coping with new work-role requirements.

However, according to our results, emotional detachment from the past work-role

fosters individuals’ adaptation to the new role.

Future research should also investigate whether disengagement buffers potentialnegative effects of obsolete behaviours on task performance in the new work-role.

Interestingly, our data showed a positive direct relationship between disengagement

and pursuit of learning, but disengagement did not buffer the negative relationship

between psychological attachment of the prior work-role and pursuit of learning. It may

be that with regard to learning, high attachment to the prior work-role is associated with

a resistance to learn things required for the newwork-role and that disengagement is not

sufficient to overcome this resistance. However, disengagement itself fosters learning

behaviour as individuals become more open to the new work-role. This is in line withresearch in cognitive psychology showing that inhibition of irrelevant information

supports learning of new information by preventing interferences and by providing

more cognitive capacity (e.g., Shapiro, Lindsey, & Krishnan, 2006; for an overview see

Golding & MacLeod, 1998). Individuals are then able to fully concentrate on the new

role without redirecting and binding attention. It is interesting to note that we found the

direct relationship between disengagement and pursuit of learning and the moderating

role of disengagement even when we controlled for how strongly individuals were

already involved with their new work-role.Another moderator which should be included in further studies of work-role

adjustment is self efficacy. It might be that depending on pre-transition experiences

individuals with high self-efficacy adapt more easily to the new demands of self-

employment. Then, psychological attachment to the prior role might play a minor role

in adaptation.

Strengths, limitations, and avenues for future researchThe present study showed that disengagement from previous work-roles helps to adapt

to the new work requirements by reducing negative consequences of being emotionally

stuck in prior work-roles. We examined adaptation to the new work-role with three

Disengagement in work-role adjustment 709

indicators (pursuit of learning, fit, and task performance) using a longitudinal design

over a period of 2 months. This design allowed us to examine changes in pursuit of

learning, fit perceptions, and task performance over 1 month (i.e., from Time 2 to Time 3).

Although our data were exclusively based on self-reports, the three-wave longitudinal

design should have reduced common method bias (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, & Lee, 2003).

With regard to the generalization of the results, one strength of the present study is thatthe data were gathered from small business owners with different educational and

occupational backgrounds who were self-employed in various industries.

However, this study is not without limitations. As mentioned above, the results were

based on self-reports. Consequently, common method bias, memory effects, and similar

processes cannot completely be ruled out (Podsakoff et al., 2003). However, due to the

longitudinal design, the self-report nature of the data may not cause a major problem

with regard to drawing meaningful conclusions for several reasons. First, predictor and

dependent variables showed considerable variations. Second, there was large variationin the correlations between variables (from2 .01 to .44 excluding stability effects); thus,

it seems common method bias did not systematically cause all variables to be related.

Third, the study focused on longitudinal relationships, and it seems unlikely that

recalling previous answers influenced answers in the subsequent waves. Fourth, as we

included outcome measures (pursuit, fit, and performance) at Time 2 as control

variables in the analyses, the influence of extraneous variables (e.g., social desirability)

should be ruled out. By controlling for the respective outcome at Time 2, we did not

predict the absolute level of fit and performance at Time 3, but instead we predicted achangeover time. Finally, common-method variance makes it unlikely to find interaction

effects (Wall, Jackson, Mullarkey, & Parker, 1996). Given that we found support for two

out of three hypothesized interaction effects, common-source bias might be less of an

issue in the present study.

Some results of the present study rely on self-ratings of task performance. As self-

ratings of performance might be inflated, future research should also include other

performance data. This is because objective outcomes such as growth in sales, earnings,

number of employees, rate of internal return on investment, or success in raisingadditional funds (Baron, 2007) do not change monthly and reflect business success in

later phases of self-employment rather than in the very first month. Particularly in the

beginning of self-employment, these objective outcomes are strongly affected by one-

time orders (e.g., of the past employer) and extraordinary benefits. Instead, future

studies should include subjective ratings of other persons such as partners or

consultants. These persons might have insight into the performance of the small

business owner.

In the present study, we explained only modest amounts of variance whenpredicting pursuit of learning and fit by psychological attachment. This might be due to

our rather heterogeneous sample including founders with different motivations of

becoming self-employed. As outcomes variables showed relatively high stabilities over

time (stability coefficients ranged between .59 and .68) one would not expect our

predictor variables to explain a great amount of variance in our outcomes (cf. Zapf,

Dormann, & Frese, 1996).

In addition, the incremental variance in the criteria explained by the two significant

interaction terms ranged from 2% for task performance to 3% for fit with the new work-role. Because of the substantial statistical difficulties in detecting significant interactions

in field survey studies (McClelland & Judd, 1993), these results may still be considered

meaningful.

710 Cornelia Niessen et al.

Another limitation is that the study examined only one mechanism of

disengagement; namely, the effort to release attention from thoughts and behaviours

related to the previous work-role in order to concentrate more fully on the new

requirements. There might be additional mechanisms underlying disengagement. For

example, disengagement may also include positive or negative reflection and

devaluation of past orientations and behaviours (cf. Wrosch et al., 2003). Furtherresearch is required to extend the study’s findings to different mechanisms and to

examine their potential impact upon adaptation to changes.

Practical implications and conclusionSome implications for practice are apparent from these results, given the evidence that

transitions from one work-role to another are not always successful (Dawis & Lofquist,

1984) and that more than 50% of new ventures fail within 5 years in the USA and other

countries (Aldrich, 1999; Bruederl, Preisendoerfer, & Ziegler, 1992). Thus, there isconsiderable room for improving the effectiveness of transition efforts into self-

employment. The results of this study suggest that one way of making transitions more

successful lies in the active disengagement from prior work-roles. If persons have to

perform successfully in the new work-role, they must be able to overcome the negative

influence of their past experiences that distract them from concentrating fully on their

new role demands. They should protect themselves from unwanted and distracting

thoughts and behaviours. Because developing new psychological attachment in the new

work-role that replaces prior affective commitment may probably take some time,disengagement is an important mechanism to facilitate adaptation to the new work-role,

as it buffers negative consequences of prior affective attachment on fit and on task

performance. Counsellors that give new founders a realistic job preview can emphasize

disengagement frompriorwork-roles, which enable founders to open their mind in order

to explore their new work-role, to solve problems, and to cope with emotional distress.

In addition, interventions could be developed to actively foster disengagement from

the prior work-role. For example, social psychological research on self-regulation and

goal striving (e.g., Gollwitzer & Brandstaetter, 1997) has demonstrated that intentionsare more likely to be effectively implemented when individuals develop implementation

intentions (i.e., specific plans linking certain situational cues to the execution of goal-

directed action). Implementation intentions are thought to enable individuals to focus

on goal-directed behaviour and to ignore potential distractions from current goal pursuit

(Gollwitzer, 1999). Future research should examine whether interventions involving the

use of implementation intentions effectively enhance individuals’ capability to

disengage from their prior work-role, thus alleviating negative effects of psychological

attachment to the previous work-role on adaptation in the new work-role.In conclusion, our study demonstrated that individuals who were high in

psychological attachment to the previous work-role exhibited poorer adjustment to

the new work-role over time. Disengagement can help them to overcome the negative

consequences of psychological attachment to the previous work-role. Then, individuals

could better adjust to their new work-role and avoid to get stuck in the past.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their deep appreciation to Sabine Sonnentag, Sandra Ohly, and two

anonymous reviewers for their substantial and constructive comments on earlier versions of this

manuscript.

Disengagement in work-role adjustment 711

References

Aldrich, H. E. (1999). Organizations evolving. London: Sage Publications.

Allen, N. J., & Meyer, J. P. (1990). The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and

normative commitment to the organization. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 63, 1–18.

Allen, V. L., & van de Vliert, E. (1984). Role transitions: Explorations and explanations.

New York: Plenum Press.

Allworth, E., & Hesketh, B. (1999). Construct-oriented biodata: Capturing change-related

and contextually relevant future performance. International Journal of Selection and

Assessment, 7, 97–111.

Baron, R. A. (2007). Entrepreneurship: A process perspective. In J. R. Baum, M. Frese, &

R. A. Baron (Eds.), The psychology of entrepreneurship (pp. 19–39). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Bauer, T. N., Morrison, E., & Callister, R. R. (1998). Organizational socialization: A review and

directions for future research. In G. R. Ferris (Ed.), Research in personnel and human

resources management (pp. 149–214). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Baum, J. R., Frese, M., & Baron, R. A. (2007). The psychology of entrepreneurship. Mahwah, NJ:

Erlbaum.

Beal, D. J., Weiss, H. M., Barrios, E., & MacDermid, S. M. (2005). An episodic process model of

affective influences on performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 1054–1068.

Beck, K., & Wilson, C. (2000). Development of affective organizational commitment: A cross-

sequential examination of change with tenure. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 56(1),

114–136.

Brandtstadter, J., & Rothermund, K. (2002). The life-course dynamics of goal pursuit and goal

adjustment: A two-process framework. Developmental Review, 22, 117–150.

Brown, S. P., Westbrook, R. A., & Challagalla, G. (2005). Good cope, bad cope: Adaptive and

maladaptive coping strategies following a critical negative work event. Journal of Applied

Psychology, 90(4), 792–798.

Bruederl, J., Preisendoerfer, P., & Ziegler, R. (1992). Survival chances of newly created founded

business organizations. American Sociological Review, 57, 222–242.

Burris, E. R., Detert, J. R., & Chiaburu, D. S. (2008). Quitting before leaving: The mediating effects

of psychological attachment and detachment on voice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93,

912–922.

Cable, D. M., & DeRue, D. S. (2002). The convergent and discriminant validity of subjective fit

perceptions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 875–884.

Cable, D. M., & Parsons, C. K. (2001). Socialization tactics and person-organization fit. Personnel

Psychology, 54, 1–23.

Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F., & Weintraub, J. K. (1989). Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically

based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(2), 267–283.

Chan, D. (2000). Conceptual and empirical gaps in research on individual adaptation at work. In

C. L. Cooper & I. T. Robertson (Eds.), International review of industrial and organizational

psychology (pp. 143–164). London: Wiley.

Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S., & Aiken, L. S. (2003). Applied multiple regression/correlation

analysis for the behavioral sciences (3rd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Covin, J. G., & Slevin, D. P. (1991). A conceptual model of entrepreneurship as firm behaviour.

Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 16, 7–25.

Dawis, R. V. (2005). The Minnesota theory of work adjustment. In S. D. Brown & R. W. Lent (Eds.),

Career development and counseling (pp. 3–23). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Dawis, R. V., & Lofquist, L. H. (1984). A psychological model of work adjustment. Minneapolis,

MN: University of Minnesota Press.

DeMartino, R., Barbato, R., & Jacques, P. H. (2006). Exploring the career/achievement and

personal life orientation differences between entrepreneurs and nonentrepreneurs: The

impact of sex and dependents. Journal of Small Business Management, 44, 350–368.

Donohue, R. (2007). Examining career persistence and career change intent using the career

attitudes and strategies inventory. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 70, 259–276.

712 Cornelia Niessen et al.

Fisher, C. D. (1986). Organizational socialization: An integrative review. In K. M. Rowland &

G. R. Ferris (Eds.), Research in personnel and human resource management (Vol. 4,

pp. 101–145). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Frese, M., Kring, W., Soose, A., & Zempel, J. (1996). Personal initiative at work: Differences

between east and west Germany. Academy of Management Journal, 39, 37–63.

Golding, J. M., & MacLeod, C. M. (1998). Intentional forgetting: Interdisciplinary approaches.

Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Gollwitzer, P. M. (1999). Implementation intentions: Strong effects of simple plans. American

Psychologist, 54, 493–503.

Gollwitzer, P. M., & Brandstaetter, V. (1997). Implementation intentions and effective goal pursuit.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73, 186–199.

Griffin, M. A., Neal, A., & Parker, S. K. (2007). A new model of work role performance: Positive

behavior in uncertain and interdependent contexts. Academyof Management Journal, 50(2),

327–347.

Hall, T. H., & Mirvis, P. H. (1995). Careers as lifelong learning. In A. Howard (Ed.), The changing

nature of work (pp. 323–361). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Harrison, J. K., Chadwick, M., & Scales, M. (1996). The relationship between cross-cultural

adjustment and the personality variables of self-efficacy and self-monitoring. International

Journal of Intercultural Relations, 20(2), 167–188.

Hasher, L., Zacks, R. T., & May, C. P. (1999). Inhibitory control, circadian arousal, and age.

In D. Gopher & A. Koriat (Eds.), Attention and performance XVII: Cognitive regulation of

performance: Interaction of theory and application (pp. 653–676). Cambridge, MA:

MIT Press.

Heckhausen, J., & Schulz, R. (1995). A life-span theory of control. Psychological Review, 102(2),

284–304.

Hinz, T., & Jungbauer-Gans, M. (1999). Starting a business after unemployment: Characteristics

and chances of success (empirical evidence from a regional German labour market).

Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 11, 317–333.

Hirst, W., & Kalmar, D. (1987). Characterizing attentional resources. Journal of Experimental

Psychology: General, 116, 68–81.

Hockey, G. R. L. (1997). Compensatory control in the regulation of human performance under

stress and high workload: A cognitive-energetical framework. Biological Psychology, 45,

73–93.

Ilgen, D. R. (1994). Jobs and roles: Accepting and coping with the changing structure of

organizations. In M. G. Rumsey & C. B. Walker (Eds.), Personnel selection and classification

(pp. 13–22). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at

work. Academy of Management Journal, 33(4), 692–724.

Klinger, E. (1996). Emotional influences on cognitive processing, with implications for theories of

both. In P. M. Gollwitzer & J. A. Bargh (Eds.), The psychology of action: Linking cognition and

motivation to behavior (pp. 168–189). New York: Guilford Press.

Krauss, S., Frese, M., Friedrich, C., & Unger, J. M. (2005). Entrepreneurial orientation: A

psychological model of success among southern African small business owners. European

Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 14, 315–344.

Kristof, A. L. (1996). Person–organization fit: An integrative review of its conceptualizations,

measurement, and implications. Personnel Psychology, 49, 1–49.

Kristof-Brown, A. L. (2000). Perceived applicant fit: Distinguishing between recruiters’

perceptions of person-job and person-organization fit. Personnel Psychology, 53, 643–671.

Lauver, K. J., & Kristof-Brown, A. (2001). Distinguishing between employees’ perceptions of

person-job and person-organization fit. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 59, 454–470.

London, M., & Mone, E. M. (1999). Continuous learning. In D. R. Ilgen & E. D. Pulakos (Eds.), The

changing nature of performance. Implications for staffing, motivation, and development

(pp. 119–153). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Disengagement in work-role adjustment 713

Louis, M. R. (1980). Surprise and sense making: What newcomers experience in entering

unfamiliar organizational settings. Administrative Science Quarterly, 25, 226–251.

Martin, L. L., & Tesser, A. (1996). Some ruminative thoughts. In R. S. J. Wyer (Ed.), Ruminative

thoughts (pp. 1–47). Hillsdale, NJ/Hove: Erlbaum.

McClelland, G. H., & Judd, C. M. (1993). Statistical difficulties of detecting interactions and

moderator effects. Psychological Bulletin, 114, 376–390.

Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J. (1997). Commitment in the workplace: Theory, research, and

application. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Meyer, J. P., Allen, N. J., & Smith, C. A. (1993). Commitment to organizations and occupations:

Extension and test of a three component conceptualization. Journal of Applied Psychology,

78(4), 538–551.

Meyer, J. P., Allen, N. J., & Topolnytsky, L. (1998). Commitment in a changing world of work.

Canadian Psychology, 39(1–2), 83–93.

Meyer, J. P., Irving, P. G., & Allen, N. J. (1998). Examination of the combined effects of work

values and early work experiences on organizational commitment. Journal of

Organizational Behavior, 19, 29–52.

Motowidlo, S. J., & Van Scotter, J. R. (1994). Evidence that task performance should be

distinguished from extrarole performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 79, 475–480.

Nicholson, N. (1984). A theory of work role transitions. Administrative Science Quarterly, 29,

172–191.

Nicholson, N., & West, M. A. (1989). Transitions, work histories, and careers. In M. B. Arthur,

D. T. Hall, & B. S. Lawrence (Eds.), Handbook of career theory (pp. 181–197). Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Niessen, C. (2006). Age and learning during unemployment. Journal of Organizational Behavior,

27, 771–792.

Nystrom, P. C., & Starbuck, W. H. (1984). To avoid organizational crises, unlearn. Organizational

Dynamics, 12, 53–65.

Ployhart, R. E., & Bliese, P. D. (2006). Individual adaptability (I-ADAPT) theory: Conceptualizing

the antecedents, consequences, and measurement of individual differences in adaptability.

In C. S. Burke, L. G. Pierce, & E. Salas (Eds.), Understanding adaptability: A prerequisite for

effective performance within complex environments (pp. 3–39). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Lee, J.-Y. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral

research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied

Psychology, 88(5), 879–903.

Porter, L. W., Steers, R. M., Mowday, R. T., & Boulian, P. V. (1974). Organizational commitment, job

satisfaction, and turnover among psychiatric technicians. Journal of Applied Psychology, 59,

603–609.

Pulakos, D. R., Schmitt, N., Dorsey, D. W., Arad, S., Hedge, J. W., & Borman, W. C. (2001). Predicting

adaptive performance: Further tests of a model of adaptability. Human Performance, 15(4),

299–323.

Pulakos, E. D., Donovan, M. A., & Plamondon, K. E. (2000). Adaptability in the workplace:

Development of a taxonomy of adaptive performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(4),

612–624.

Runyan, R. C., Huddleston, P., & Swinney, J. (2006). Entrepreneurial orientation and social capital

as small firm strategies: A study of gender differences from a resource-based view.

International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 2, 455–477.

Saks, A. M., & Ashforth, B. E. (1997). A longitudinal investigation of the relationships between job

information sources, applicant perceptions of fit, and work outcomes. Personnel Psychology,

50, 395–426.

Schaufeli, W. B., Salanova, M., & Gonzalez-Roma, V. (2002). The measurement of engagement and

burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies,

3(1), 71–92.

714 Cornelia Niessen et al.

Schein, E. (1971). The individual, the organization, and the career: A conceptual scheme. Journal

of Applied Behavioral Science, 7, 401–426.

Schumpeter, J. A. (1934). Theorie der wirtschaftlichen Entwicklung [Theory of economic

development] (4th ed.). Berlin: Duncker & Humblot.

Shapiro, S., Lindsey, C., & Krishnan, H. S. (2006). Intentional forgetting as a facilitator for recalling

new product attributes. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 12(4), 251–263.

Solinger, O. N., van Olffen, W., & Roe, R. A. (2008). Beyond the three-component model of

organizational commitment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93, 70–83.

Sonnentag, S. (2003). Recovery, work engagement, and proactive behavior: A new look at the

interface between nonwork and work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(3), 518–528.

Thompson, T., Webber, K., & Montgomery, I. (2002). Performance and persistence of worriers and

non-worriers following success and failure feedback. Personality and Individual Differences,

33, 837–848.

VandeWalle, D. (1997). Development and validation of awork domain goal orientation instrument.

Educational and Psychological Measurement, 57, 995–1015.

Van Maanen, J., & Schein, E. (1979). Toward a theory of organizational socialization. Research in

Organizational Behavior, 1, 209–264.

Wall, T. D., Jackson, P. R., Mullarkey, S., & Parker, S. K. (1996). The DC-model of job strain: A more

specific test. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 69, 153–166.

Ward, C., & Chang, W. C. (1997). ‘Cultural fit’: A new perspective on personality and sojourner

adjustment. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 21(4), 525–533.

Weiss, H. M., & Cropanzano, R. (1996). Affective events theory: A theoretical discussion of

the structure, causes and consequences of affective experiences at work. In B. M. Staw &

L. L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior (Vol. 18, pp. 1–74). Greenwich,

CT: JAI Press.

West, M. A. (1987). Role innovation in the world of work. British Journal of Social Psychology,

26, 305–315.

Williams, L. J., & Anderson, S. E. (1991). Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as

predictors of organizational citizenship and in-role behaviors. Journal of Management, 17(3),

601–617.

Wrosch, C., Scheier, M. F., Carver, C. S., & Schulz, R. (2003). The importance of goal

disengagement in adaptive self-regulation: When giving up is beneficial. Self and Identity,

2, 1–20.

Yeatts, D. E., Folts, W. E., & Knapp, J. (2000). Older workers’ adaptation to a changing workplace:

Employment issues for the 21st century. Educational Gerontology, 26, 565–582.

Yee, P. L., & Vaughan, J. (1996). Integrating cognitive, personality, and social approaches to

cognitive interference and distractibility. In I. G. Sarason, G. R. Pierce, & B. Sarason (Eds.),

Cognitive interference: Theories, methods, and findings (pp. 77–97). Hillsdale, NJ/Hove:

Erlbaum.

Ying, Y.-W. (2002). The effect of cross-cultural living on personality: Assimilation and

accommodation among Taiwanese young adults in the United States. American Journal of

Orthopsychiatry, 72(3), 362–371.

Zacks, R. T., & Hasher, L. (1994). Directed ignoring. Inhibitory regulation of working memory.

In D. Dagenbach & T. H. Casr (Eds.), Inhibitory processes in attention, memory, and

language (pp. 241–264). London: Academic Press.

Zapf, D., Dormann, C., & Frese, M. (1996). Longitudinal studies in organizational stress research:

A review of the literature with reference to methodological issues. Journal of Occupational

Health Psychology, 1, 145–169.

Received 17 December 2008; revised version received 20 July 2009

Disengagement in work-role adjustment 715