What predicts healthy lifestyle habits? Demographics, health ...

Diary-based survey of lifestyle habits in everyday activities ...

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of Diary-based survey of lifestyle habits in everyday activities ...

Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found athttps://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=iocc20

Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy

ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/iocc20

Diary-based survey of lifestyle habits in everydayactivities and support for the process of change – autility study

Ida Kåhlin & Lena Haglund

To cite this article: Ida Kåhlin & Lena Haglund (2022): Diary-based survey of lifestyle habits ineveryday activities and support for the process of change – a utility study, Scandinavian Journal ofOccupational Therapy, DOI: 10.1080/11038128.2022.2034942

To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/11038128.2022.2034942

© 2022 The Author(s). Published by InformaUK Limited, trading as Taylor & FrancisGroup.

Published online: 08 Feb 2022.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 238

View related articles

View Crossmark data

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Diary-based survey of lifestyle habits in everyday activities and support forthe process of change – a utility study

Ida Kåhlin and Lena Haglund

Department of Health, Medicine and Caring Sciences (HMV), Division of Prevention, Rehabilitation and Community Medicine (PRNV),Link€oping University, Link€oping, Sweden

ABSTRACTBackground: The need to support a healthy lifestyle among the population has becomeincreasingly apparent in recent years. The National Board of Health and Welfare in Sweden haspublished national guidelines regarding unhealthy lifestyle habits since 2011. An instrumentbased on the practical and theoretical foundations of occupational therapy was developed tosupport the profession’s unique contribution to implementing these guidelines.Aims: The aim was to examine the utility of the instrument by investigating its implementationpotential and clinical relevance.Material and Method: Sixteen occupational therapists used the instrument in practice togetherwith 60 clients. Afterwards, they completed a questionnaire covering questions of utility.Result: The instrument demonstrated mostly positive dimensions of utility. The results showthat the instrument seems to have a high implementation potential and is clinically relevant. Itseems, for example, to support implementation of the national guidelines and to capture how aperson’s lifestyle habits are expressed in everyday occupations. The instrument further seems topromote people’s participation in treatment.Conclusion: The instrument ‘Diary-based survey of lifestyle habits in everyday activities and sup-port for the process of change’ seems promising in terms of utility. However, the scientific meritof the instrument will need to be further established.

ARTICLE HISTORYReceived 30 April 2021Revised 11 January 2022Accepted 22 January 2022

KEYWORDSHealth promotion;occupational therapy;prevention of unhealthylifestyles; self-assessment

Introduction

Unhealthy lifestyles, which increase the risk of devel-oping noncommunicable diseases (NCD) and prema-ture death, are today one of the biggest threats toglobal health. NCDs, such as cardiovascular diseases,cancers, chronic respiratory diseases, and diabetes kill41 million people each year, equivalent to more than70% of all deaths globally [1]. The importance ofhealthy lifestyles has been further emphasised duringthe COVID-19 pandemic. Several risk factors forCOVID-19 can be influenced by an unhealthy life-style. Experts have highlighted the importance ofgood habits of daily living to reduce the likelihood ofbecoming seriously ill [2].

Supporting healthy lifestyles is also an importantpart of the realization of Goal 3 of the UnitedNations Agenda 2030, particularly goal 3.4: ‘By 2030,reduce by one-third premature mortality from non-

communicable diseases through prevention and treat-ment and promote mental health and well-being’ [3].According to The Shanghai Declaration on HealthPromotion [4], societies must support healthy life-styles by, for example, facilitating people to makehealthy consumer choices and promotingsocial inclusion.

Since 2011 the National Board of Health andWelfare in Sweden has published national guidelinesregarding the prevention of unhealthy lifestyle habits.The guidelines are based on current research and les-sons of experience and include methods to counteractthe four unhealthy lifestyle habits that contributemost to the overall disease burden in Sweden: tobaccouse, hazardous use of alcohol, unhealthy eating habitsand insufficient physical activity. In 2018, the nationalguidelines were updated, and their official titlebecame: ‘Prevention and treatment of unhealthy

CONTACT Ida Kåhlin [email protected] Department of Health, Medicine and Caring Sciences (HMV), Division of Prevention, Rehabilitation andCommunity Medicine (PRNV), Link€oping University, Campus Norrk€oping, Link€oping, S-581 83, Sweden� 2022 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group.This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits non-commercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited, and is not altered, transformed,or built upon in any way.

SCANDINAVIAN JOURNAL OF OCCUPATIONAL THERAPYhttps://doi.org/10.1080/11038128.2022.2034942

lifestyles’ [5], hereafter referred to as the ‘NG life-style’, where NG stands for national guidelines.

The two recommended methods in the NG lifestyleto decrease tobacco use, the hazardous use of alcohol,unhealthy eating habits and insufficient physical activ-ity are: a) counselling and b) advanced counselling.All healthcare professionals in Sweden are consideredto have the knowledge to be able to work with thesetwo methods, but advanced counselling requires in-depth knowledge. It is a method that is theory-based;for example, Social learning theory, Cognitive behav-iour theory, or Social cognitive theory according tothe NG lifestyle.

In the long term, application of these methods isexpected to reduce the number of people withunhealthy lifestyles, which in turn will reduce the riskof future illness and premature death.

Occupational therapy has a unique role in the pre-vention and treatment of unhealthy lifestyles due toits focus on the health effects of purposeful andmeaningful occupations in everyday life [6,7]. It is ineveryday occupations that unhealthy lifestyle habitsare concretised. Occupational therapists use occupa-tion-based interventions in which the dynamic rela-tionships among humans, their occupations and theenvironment are central to supporting people inachieving a change in their everyday occupations [8].The overarching aim of occupational therapy is tochange occupational performance and support occu-pational engagement to promote health and well-being [9].

In terms of occupational therapy interventionsaimed at changing any of the four lifestyle habits tar-geted in the NG lifestyle, there seems to be a lack ofsuch interventions supported by reasonable levels ofevidence. For example, we have not been able to findany articles describing how occupation-based inter-ventions support decreased tobacco use. This is alsoconfirmed by Ramafikeng, Galvaan and Amesun [10],who found in 2019 that tobacco use has not been welldocumented in occupational therapy literature.Andersson et al. [11], who studied women’s everydayoccupations and alcohol consumption call for newpreventive approaches in the treatment of alcoholoverconsumption, including investigating the import-ance of having engaging leisure. No articles describingthis could be found. Furthermore, Johannessen,Engedal and Helvik [12] and Chippendale, Gentileand James [13] draw attention to elderly people’s useof alcohol and how it affects, for example, the risk offalls. These authors argue that consumption should beinvestigated more, but no tools for this are described.

In 2018, Nielsen and Christensen [14] published areview article showing that there is insufficientexplanation of the role and contribution of occupa-tional therapy to the outcomes in the treatment ofadults who are overweight or obese. Conn et al. [15]also point out the same shortcoming in their 2019review. There are several articles describing studieswhere unhealthy eating habits are taken into account,because this is a common problem faced by occupa-tional therapists, but the descriptions of interventionsare often insufficient, and it is often not possible todistinguish the efforts that are only aimed at eat-ing habits.

Finally, regarding insufficient physical activity,there is a large body of articles describing exercise orphysical activity, often for different diagnostic groups:for example, Marik and Roll [16] who show thatstrengthening exercises are an effective occupationaltherapy intervention in musculoskeletal shoulder con-ditions, and Siegel [17], who shows that aerobic exer-cise is appropriate in the treatment of peoplesuffering from rheumatoid arthritis. But, the authorsconclude that few efforts are occupation-based.Programmes that include exercise or physical activ-ities are also described as NEW-R, Nutrition andExercise for Wellness and Recovery [18] and HEALS,Healthy Eating and Lifestyle after Stroke [19], but nostudies describing their effect can be found.Pettersson and Iwarsson [20] report in a review articleregarding everyday rehabilitation for the elderly thatphysical activity does have a certain effect on the abil-ity to be active, but that the result has a low degree ofevidence and further research is needed.

To sum up, to our knowledge, there are no cohortstudies or randomized controlled trials focussing onspecified occupational therapy interventions forchanging any of the four lifestyle habits defined inthe NG lifestyle, with reasonable levels of evidence.As all health care professionals in Sweden shouldwork to improve healthy lifestyles [5], it is importantto clarify the role of occupational therapists in healthpromotion and the prevention of diseases/disabilitiesthat are presented in the NG lifestyle. If the profes-sion wants to be a recognized part of health promo-tion work in society, it must take responsibility forpromoting methods for implementing change in thelifestyle habits described in the national guidelines,but from an occupational therapy perspective. Thismeans focussing on the client’s motivation, daily hab-its, and doing of occupations such as work, recre-ation, and activities of daily living in his or herunique environment [21].

2 I. KÅHLIN AND L. HAGLUND

Working to improve healthy lifestyles as an occu-pational therapist assumes the use of a process forproviding service to the client. According to theAmerican Occupational Therapy Association, thisprocess includes the following three steps: (a) individ-ualized evaluation, (b) customised intervention, and(c) outcomes evaluation [22]. Undertaking these stepsprovides a systematic approach to the daily worktogether with clients. It is important to emphasizethat the process is not linear. The occupational ther-apist may need to move back and forth between thedifferent steps of the process. Collection of new infor-mation may, for example, need to be undertakenwhen interventions are planned, and goals are concre-tized. Individualized evaluation means to gather infor-mation. It is the initial step in the process, and it iscrucial because it influences all the other steps thatfollows, such as goal setting, planning, choice of inter-vention, etc. The evaluation can be achieved by usingdifferent standardized procedures, such as interviews,observations, and self-assessments. A diary-basedinstrument, a self-assessment, capturing what a persondoes during the day at different times, can help habitsand routines to become visible to the person, whichin turn can clarify the need for change. Such aninstrument facilitates reflections on how patterns ofdaily occupations influence well-being [23,24].

To support the implementation of the NG lifestylein occupational therapy, a diary-based instrument formapping lifestyles and supporting the process ofchange has been developed: ‘Diary-based survey oflifestyle habits in everyday activities and supportfor the process of change’ (DSL), (Kartl€aggningav levnadsvanor under aktivitet och st€od if€or€andringsprocessen) [25]. The purpose of theinstrument is to gather information about what a per-son does during the day by using a diary, how thefour lifestyle habits in the NG lifestyle are concretized,and how the person perceives that his/her lifestylehabits contribute to health. The instrument has a per-son-centred approach [26] and also provides supportin clarifying any need for change.

Since DSL is a new instrument, it is important toevaluate its utilization potential. According to Politand Beck [27,28], the benefits of an innovation,such as testing a new instrument in practice, can beevaluated by studying three aspects of utilization:implementation potential, clinical relevance, and sci-entific merit.

The aspect of implementation potential includesthe feasibility, transferability, and costs and benefitsof the innovation. Feasibility testing addresses

practical issues such as requirements for equipment,materials, and knowledge and whether the instrumentis compatible with the occupational therapist’s mis-sion and function in practice. Feasibility also refers tothe necessary skills to use the instrument. The termtransferability means, for example, that the instru-ment is useful for the client and the occupationaltherapist, and that the instrument is suitable in thecurrent environment. In addition, administrative andfinancial aspects as well as time required for its useare factors related to transferability. Costs and bene-fits of the innovation include the material and non-material costs of implementing the innovation andany conceivable risks relating to the implementation.In addition, it is also urgent to evaluate the potentialbenefits regarding change or retaining the status quo,including staff, clients, and the organization.

The second aspect, clinical relevance, considerswhether, among other things, the instrument providessupport for solving problems in practice, supportsdecision-making, and assists in choosing appropriateinterventions. The practical relevance of the instru-ment and the support it can offer interprofessionalcollaborations are also included.

The last aspect is the scientific merit of the innov-ation. This focuses on evaluating the quality of theavailable research in the actual area, including the val-idity, reliability, and generalizability of the results ofthe studies in relation to the innovation.

The aim of this study was to examine the utility ofthe instrument ‘Diary-based survey of lifestyle habitsin everyday activities and support for the process ofchange’. The study focuses on the following aspects ofutility: implementation potential – i.e. feasibility,transferability, and costs/benefits, and clin-ical relevance.

Material and methods

Description of the instrument

The DSL is designed to support the implementationand application of the NG lifestyle in occupationaltherapy practice. It has been developed by the secondauthor (LH) in collaboration with 18 professionaloccupational therapists, at the request of the SwedishAssociation of Occupational Therapists, with financialsupport from the Swedish National Board of Healthand Welfare. The aim of the instrument is to eluci-date what a person does during a day and how thelifestyle habits – tobacco use, hazardous use of alco-hol, unhealthy eating habits and insufficient physicalactivity – are concretized in the doing of everyday

SCANDINAVIAN JOURNAL OF OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY 3

activities. The aim is also to provide support in iden-tifying what changes a person can envisage and howthat change could be made.

The person-centred approach used in this instru-ment highlights the need for individual evaluationsand interventions and emphasizes that the responsi-bility for designing the individual change plan isshared between the client and the occupational ther-apist. The client must be given the opportunity toexpress his/her views about his/her lifestyle and occu-pational patterns as well as what activities are import-ant for to him/her. The role of the occupationaltherapist is to support the client’s participation. Ashared understanding of the client’s situation enablesa strong alliance and promotes the his/her engagement.

The instrument highlights the client’s doing andhas taken inspiration from the theoretical foundationsof occupational therapy described by, for example,Reilly [29] and Wilcock and Hocking [30]. The theoryof doing is based on the assumption that people havean innate need to engage in occupations becausehealth depend on it. Doing takes place within a per-son’s physical and socio-cultural environment and isbased on what the person needs to do, wants to do, isexpected to do, or is forced to do.

The DSL is a self-assessment instrument and wasdeveloped to be used together with adults. It is notfocussed on any special disability and/or impairment.The DSL manual covers areas such as (a) theoreticalfoundations, (b) general instructions to the occupa-tional therapist when using the instrument togetherwith the client, (c) how to support change by meansof an occupation-based approach, and d) three differ-ent forms (A, B and C) for self-assessment. Form Aincludes all four lifestyle habits described in the NGlifestyle (tobacco use, hazardous use of alcohol,unhealthy eating habits and insufficient physical activ-ity), Form B includes two lifestyle habits: unhealthyeating habits and insufficient physical activity andForm C:1–C:4 comprises separate forms for each ofthe four NG lifestyle habits.

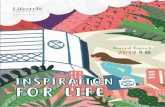

The instrument consists of three parts. In the ini-tial self-assessment section, Part 1: Indicate youractivities, each half hour during the day is docu-mented by the client. For this purpose, the client,together with the occupational therapist, chooses oneof the forms (A, B or C) and uses it to state whatactivities are being undertaken and then indicatingwhether he/she smoked, drank alcohol, ate something,and/or was physically active during the activity. If anyof the four lifestyle habits are applicable a statement‘Little’, ‘Just right’ or ‘Too much’ is noted in Part 2:Value your lifestyle habits (Figure 1).

The client can choose to fill in a ‘Typical day’ or a‘Specific day’. If the client chooses a ‘typical day’, heor she can fill in the form once and enter the activ-ities that are normally performed during a day. If theclient chooses a ‘specific day’, he or she reports every30min on what has been done. Choosing a ‘specificday’ means that it takes longer to fill in the form.Based on the client’s condition, adaptations can bemade; for example, perhaps only the morning will beexamined, or only one of the four lifestyle hab-its elucidated.

In the last part of the instrument, Part 3: Changingyour lifestyle habits, the client identifies which life-style habits he/she would like to change, what goalscan be seen, and which of these to priorities. Afterthis, the client specifies during which activity he/shebelieves that a change would be possible and writes adescription in more detail of how the change can bemade. Finally, the date for follow-up is determined.

As shown, the instrument represents two essentialpoints of view: the client’s perception of their lifestylehabits and need for change, and the partnershipsbetween the client and the occupational therapist,where goals and change strategies are formulated.

The questionnaire

To determine the utility of the instrument, a ques-tionnaire was developed and sent out to occupationaltherapists using the instrument in practice. The

Time Activity During the activity

I smoked I drank alcohol I ate something I was physically active

No Little Just

right

Too

much

No Little Just

right

Too

much

No Little Just

right

Too

much

No Little Just

right

Too

much 05.0005.3006.0006.3007.0007.3008.0008.30Tocon�nue

Figure 1. Form A. Including Part 1: Indicate your activities and Part 2: Value your lifestyle habits.

4 I. KÅHLIN AND L. HAGLUND

questionnaire contained questions related to two ofthe aspects of utility described by Polit and Beck:implementation potential and clinical relevance[27,28]. The questionnaire contained 54 questions andused different answer alternatives: yes/no alternatives,answer scales and short written notes. Initially, demo-graphic information was requested.

The implementation potential included an examin-ation of the instrument’s feasibility, transferability,and costs/benefits. Examples of questions that focuson feasibility in the questionnaire are: Is there any-thing that should be changed in the manual? How doyou perceive your knowledge of the NG lifestyle hab-its? Does the instrument fit into your practice? Doyou think the instrument is useful for occupationaltherapists? Does it reflect the theoretical and practicalfoundations of the profession?

Examples of questions about transferability in thequestionnaire are: How long did it take for the clientto fill in the different parts of the instrument? Couldthe client work independently with the instrument?Did the client use all the parts of the instrument? Byasking whether the occupational therapists consideredthat the instrument was cost-effective or not, thecost–benefit perspective was examined.

Examples of questions related to clinical relevanceare: Has the instrument supported you in your prob-lem-solving process regarding elucidating the client’slifestyle habits and need for intervention? Do youthink you will use the instrument in the future?Would you recommend that colleagues usethe instrument?

Procedure

The data collection was conducted during September– November 2020. The questionnaire was distributedvia the survey tool ‘Survey Generator’. The SwedishAssociation of Occupational Therapists’ website andsocial media were used to advertise for participants.Nineteen occupational therapists registered theirinterest in participating in the study via email to thesecond author (LH). For introduction to the studyLH made contact by email and/or telephone witheach participating occupational therapist. This intro-duction included information about the instrument,how to use it in practice, the aim of the study, and achecklist. The idea of the checklist was to make it eas-ier to answer the study-specific questionnaire that wasdistributed at the end of the study period. The partici-pants were recommended to fill it in as they met eachclient with whom they used the instrument. The

checklist contained question areas that occurred inthe questionnaire. Only information about clients’gender, age, and care unit was requested.

One reminder was sent out. Once the results werecompiled, contact could be made with participants ifany answers were difficult to clarify. However, allanswers in the results section are reportedanonymously.

Participants

Occupational therapistsThree of the nineteen occupational therapists, whoregistered their interest in participating in the studywere unable to use the instrument in practice due tothe prevailing COVID-19 situation during autumn2020. Consequently, sixteen occupational therapistsworking in mental health, primary care, and out-patient specialist care participated in the study. Allparticipants except one were female. Fifteen had abachelor’s degree in occupational therapy, and twoalso had a master’s degree. Time as a professionaloccupational therapist varied between three and35 years, with an average of 14.6 years. The number ofapplications of the instrument by each occupationaltherapist with their clients varied from one to eight(Table 1).

ClientsThe instrument was used together with 60 adults, ofwhom 32 were female and 28 male. Approximately

Table 1. Descriptions of participants: occupational therapists.Demographic characteristics Number (total n¼ 16)

GenderMale 1Female 15

EducationDiploma 1Bachelor’s Degree 15Master’s Degree 2

Years of Experience1–5 26–10 411� 15 416� 20 3>21 3

Number of applications1 63 35 26 27 18 2

Main area of workMental health 9Primary care 6Outpatient specialist care 1

SCANDINAVIAN JOURNAL OF OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY 5

63% of the clients were aged 30–49 years, and themost common form of care was primary care(Table 2).

Data analyses

Demographic and quantitative data collected via thequestionnaire were analysed using descriptive statistics(frequency, percentage, median and range). The short-written notes were compiled and notes with thesame intention were clustered. Quotes are used toillustrate response content.

Ethical concerns

This study was not associated with ethical risk criteriain Sweden. The study was performed according to theethical guidelines and recommendations for goodresearch practice published by the Swedish ResearchCouncil [31].

Results

Implementation potential

FeasibilityOf the occupational therapists, 13 (81%) consideredthat they had fairly good or very good knowledge ofthe NG lifestyle before the study started, and allexcept one stated that they include lifestyle habits intheir practice. Various forms of screening toolsdirected by the regional health and medical careauthority were given as examples of how lifestyleaspects were included. Three occupational therapistsstated that they had chosen to deepen their know-ledge of NG lifestyle habits by retrieving knowledgefrom the web service offered by the National Board ofHealth and Welfare and/or the Swedish Association

of Occupational Therapists which is referred to in themanual (theoretical foundations).

Fourteen (88%) occupational therapists stated thatthey consider the manual for the instrument to beeasy to understand and to get started with when sur-veying a client’s lifestyle habits; one thought it was‘very easy’ and one thought it was ‘difficult’. Oneoccupational therapist pointed out that the manualneeds to be modified with respect to the forms, asthey are too long and detailed.

More than two-thirds of the occupational thera-pists (69%, n¼ 11) perceived that the information theclient needed before they could fill in Parts 1 and 2of the instrument was reasonable and more than 75%(n¼ 12) perceived that the client could most oftenuse the scale steps’ Little’, ‘Just right’ or ‘Too much’.Difficulties arose with the scale steps if the client hadproblems with the use of the Swedish language. Thefinal question in the questionnaire allowed occupa-tional therapists to make additional comments; inthese comments it also emerged that clients may havedifficulty understanding the scale steps. The conceptsneed to be clarified better in the manual. Of the occu-pational therapists, 75% (n¼ 12) reported that theinformation the clients needed before they could fillin Part 3 was reasonable, and one occupational ther-apist reported that the clients needed an unreasonableamount of information.

To deepen their knowledge of various strategies forchange using an occupation-based approach, one-third of occupational therapists have used the infor-mation and recommended literature given inthe manual.

Two occupational therapists stated that there weretimes when it could be unethical to use the instru-ment. For example, the reason why the client hasrequested care may in some instances mean that it isinappropriate to ask about lifestyle habits. The instru-ment was also perceived as being confusing if the cli-ent had reading and writing difficulties or impairedcognitive ability due, for example, to depression orstroke. Furthermore, discussion of the interpretationof the scale steps can be experienced as being emo-tionally charged, for example, when patients have eat-ing disorders.

The strengths of the instrument indicated by theoccupational therapists are shown in Figure 2.

Strengths that are most appreciated by the occupa-tional therapists are that the instrument promotes cli-ents’ participation, focuses on doing and not diseasesymptoms, is person-centred, promotes partnershipsbetween the client and the occupational therapist and

Table 2. Descriptions of participants: clients.Demographic characteristics Number (total n¼ 60)

GenderMale 28Female 32

Age (years)>20 020–29 1130–39 1940–49 1950� 59 560 < 6

Care unitMental health 19Primary care 24Outpatient specialist care 8Other 9

6 I. KÅHLIN AND L. HAGLUND

is easy to implement. However, the instrument doesnot seem to promote collaboration within the team.Everyone, except one occupational therapist, statedthat the instrument fills a gap in their professionaltoolbox and that it fits into their practice. When itdoes not fit, it is explained by the fact that it is toolong and detailed.

Finally, regarding feasibility, occupational therapistsindicate that the instrument helps them to pay atten-tion to unhealthy lifestyle habits in their daily workas an occupational therapist, and all, except one occu-pational therapist considered that it reflects the theor-etical and practical foundations of the profession to a‘moderate’ or ‘high’ degree.

TransferabilityIt took on average 27min for the clients to fill inParts 1 and 2 of the instrument, with a range of10–45min. The time required was considered reason-able by 88% (n¼ 14) of the occupational therapists.

Forty-five clients chose to fill in a ‘Typical day’.Form A was used by 20 clients, form B by 22, and 18clients chose one of the C forms. Furthermore, 48 cli-ents filled in the instrument for ‘most all times’ of a

day and 28 clients filled in Parts 1 and 2 independ-ently without the participation of the occupationaltherapist. If the client chose to fill in the instrumentduring a visit to the occupational therapist, they filledit in together in 26 cases.

Forty-nine clients chose to work with Part 3:Change your lifestyle habits. Table 3 shows how inde-pendently the clients worked with the different sec-tions in Part 3: identification of which lifestyle habitsthe client wants to change, goal formulations, priori-tization of goals, in what activity the change might bepossible, and how the change would be madepractically.

As can be seen from the table, the degree of inter-action between the client and the occupational therapistincreased as the formulation of the change process pro-gressed. They had more interaction when it came to for-mulating change strategies than in identifying whichlifestyle habits the clients felt they wanted to change.

According to the occupational therapists, the cli-ents experienced use of the instrument as ratherrewarding. The use of the instrument seems to havegiven clients new ways of managing their lifestylehabits (Figure 3).

Table 3. Procedure in Part 3 of the instrument: change your lifestyle habits (n¼ 49).

ProcedureIndependently

at homeIndependently at

the OT� departmentIn collaboration between

the client and OT

Identification of lifestyle habit to change 17 6 26Goal formulation 17 6 26Prioritization of goals 17 7 25Identification of activity where change can possible 14 8 27Formulating strategies for change 11 7 31�OT: Occupational therapy.

Figure 2. Instrument strengths according to occupational therapists.

SCANDINAVIAN JOURNAL OF OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY 7

The instrument provides certain options, and howimportant these options were perceived to be by theoccupational therapists is shown in Table 4.

All the options that the instrument allows seem tobe ‘important’ or ‘very important’ for the occupa-tional therapists when applying the instrument. Theopportunity to choose between different forms and touse different methods for collaboration with the cli-ents seem to be perceived as most valuable.

Costs/benefitsTwo occupational therapists stated that the instru-ment is not cost-effective. They reported that theeffort required to gather information about how thefour lifestyle habits are concretized in client’s every-day life, and how the client perceives that his/her life-style habits contribute to health, do not correspondwith the benefit the occupational therapist derivesfrom the instrument. The remaining occupationaltherapists (n¼ 14) stated that they considered theinstrument to be cost-effective.

Clinical relevance

As reported above, 49 clients worked with Part 3 ofthe instrument. Within the timetable of the study, thechanges were completed for seven clients, and theirgoals had been achieved. For the remaining clients,the follow-up had not yet been carries out (n¼ 14),or showed need for further change (n¼ 28).

All the occupational therapists, except one, indi-cated that the instrument helped them to take a

person-centred approach and all, except one, alsostated that it captured how the lifestyle, as presentedin the NG lifestyle, are concretized in everyday occu-pations and how clients perceive that their lifestylehabits contribute to their health.

All the occupational therapists considered theinstrument to provide support in identifying anychange needs and when to formulate goals.Furthermore, 75% (n¼ 12) stated that the instrumentprovides support for choosing how the change shouldbe made in an activity if the need for change hasbeen identified. The instrument further facilitatesdocumentation, according to 88% (n¼ 14) of occupa-tional therapists.

The various parts (Parts 1, 2, and 3) were con-sidered to have ‘moderate’ to ‘high’ practical rele-vance by most occupational therapists. Oneoccupational therapist considered that all three partslacked practical relevance and one occupationaltherapist considered that Part 2 had little prac-tical relevance.

Interactions with the client were not affected bythe application of the instrument according to 50%(n¼ 8) of the occupational therapists. Those whostated that the interaction had been affected providednotes such as:

“The patient is made more involved.”

“A smooth way to enter a very important area.”

“Not just yes and no questions.”

“Further conversations about the clients’ activities wasfacilitated.”

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80

They re-organized their daily ac�vi�es

They found the instrument s�mula�ng and interes�ng

They paid a�en�on to their lifestyle habits in a new way

They found new ways to deal with lifestyle habits

They were bored

They were bothered

They believed that it was a must to par�cipate

Percent

Figure 3. Occupational therapists’ views about clients’ experiences. More than one option could be chosen.

Table 4. The importance of options in the instrument�.Option Very important Important Somewhat important Not important

Selection of ‘typical day’ or ‘specific day’ 17% 67% 16%If one or more days are to be mapped 9% 50% 33% 8%If all hours of the day are to be mapped 25% 50% 17% 8%Choice of form (A, B or any of C) 59% 25% 8% 8%Method for implementation (independent or in collaboration) 50% 42% 8%�More then one options could be indicated.

8 I. KÅHLIN AND L. HAGLUND

“It clarifies for the patient what to work with.”

All 16 occupational therapists would recommendthat colleagues use the instrument, and they believethat they will use the instrument in the future.

Discussion

This study shows that DSL seems to be a usefulinstrument in occupational therapy practice. It sup-ports the implementation of the NG lifestyle. It cap-tures what a person does during a day and how thelifestyle habits – tobacco use, hazardous use of alco-hol, unhealthy eating habits and insufficient physicalactivity – are concretized in the doing of everydayactivities. It also illustrates how people perceive thattheir lifestyle habits contribute to their health. Thestudy shows that the instrument seems to have a highimplementation potential and is clinically relevant.

The instrument helps occupational therapists topay attention to the NG lifestyle in their daily workand it reflects the theoretical and practical founda-tions of the profession. Consequently, the instrumentseems to clarify the contribution of occupational ther-apy, and the efforts of an occupation-based interven-tion to support the changes in lifestyle habitsdescribed in the NG lifestyle. In previous literature,there were no support for occupational therapy inter-ventions targeting any of the four lifestyles habitsfound [10–20]. The findings of this utility study indi-cate that the instrument DSL has the potential to fillthe gap in the occupational therapists’ toolbox of pre-vention and treatment of unhealthy lifestyles thatwere described in the background.

Occupational therapists seem to have the skillsrequired to use the instrument, but if there is a needfor additional knowledge, it was stated that the man-ual provides guidance on where such knowledge canbe obtained. The manual is a support for applicationof the DSL. It was easy to understand and to startusing the instrument.

The time required to work with the DSL is gener-ally perceived as reasonable, although a few occupa-tional therapists stated that it takes too long. Abouthalf of the clients who participated filled in Parts 1and 2 independently. Part 3 was also filled in bymany of the clients and many also worked with Part3 independently.

The results indicate that, in the occupational thera-pists’ view, the clients consider the instrument to beapplicable. Collaboration increased between clientsand their occupational therapists when formulatingchanges in more detail in Part 3. Formulating changes

to daily activities that are detailed enough to supportmore healthy lifestyle habits can be a challenge formany clients. Occupational therapists have the com-petence, for example, to break down activities intosteps or actions [32], and this can support the clientin identifying strategies for change.

The various forms that the instrument containsseem to support the application of the DSL as well.All three versions, A, B, and C variants were used toabout the same extent.

The results indicate that the instrument can helpclients to pay attention to their lifestyle habits in anew way. It gives them new ways of dealing withproblems with their lifestyle and they saw the surveyas stimulating and as giving them ideas about howthey could reorganize their activities. Most of theoccupational therapist also found the instrument tobe cost effective. Only two occupational therapistswere of a different opinion.

The instrument seems to support the occupationaltherapist to solve problem in practice. It has a clearperson-centredness, it promotes clients’ participationin the treatment process, e.g. everything from statedlifestyle habits during everyday activities, to indicatingchanges in lifestyle habits, identifying change strat-egies, and to clarifying follow-up. Additionally,recording the treatment is also facilitated.

All the participating occupational therapists believethat they will use the instrument in the future, andthey are willing to recommend it to colleagues, eventhough some stated on other questions that theyexperienced some weaknesses in the instrument.

A weakness of the instrument is that some clientshad difficulty in understanding the scale steps ‘Little’,‘Just right’ and ‘Too much’. The manual thereforeneeds to be developed. It is suggested that a clearerdescription should be given of the fact that it is theclient’s perception that is sought and that the occupa-tional therapist must spend time examining and creat-ing an understanding of how the client perceives thescale steps.

Another weakness to emerge is that the instrumentis too extensive. One thing that may contribute tothis statement is whether it is activities during a‘Typical day’ or a ‘Specific day’ that are reported. Thereason why this is highlighted is that the approachesto filling in Part 1 and Part 2 differ. If choosing a‘Typical day’, Part 1 ‘Indicate your activities’, is car-ried out first, and then Part 2 ‘Value your lifestylehabits’. If, on the other hand, a ‘Specific day’ ischosen, the recommendation is to fill in the formretrospectively during the day; for example, once at

SCANDINAVIAN JOURNAL OF OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY 9

lunchtime, once in the afternoon and once in theevening, and to fill in both Part 1 and Part 2 at thesame time. The specification and choice of day alsoaffects the approach, which can further affect thetrustworthiness of the response. If a ‘Typical day’ isreported, the person may not remember exactly whatwas done during every half-hour, compared to fillingin the form three to four times during a day and thenat the same time value their lifestyle habits. Thechoice of day may also affect validity. Is it a typicalday for the person’s everyday occupations that isbeing reported? Although the choice of day can beperceived as rather cumbersome, it is important tokeep in mind that it is the client’s opinion that isbeing sought. There are no right or wrong answers.

Bias due to self-reporting could be present, and theclient may provide unreliable responses for a widevariety of reasons [33,34]. However, the manualclearly states that the instrument is intended to beused as a basis for dialogue between the occupationaltherapist and the client in order to clarify any needfor change. In any case, the occupational therapistmust judge whether the client’s values, choice tochange, and goal formulations are likely to support ahealthier lifestyle. If the goals, are unreasonable, forexample, or perhaps risky, this must of course beraised and discussed with the client. A person-centredapproach does not mean that the occupational therap-ist must remain silent about his or her opinion, but itmust be conveyed with respect for the client and theclient has the right to say no to the occupationaltherapist’s suggestions. One way to deal with disagree-ment can be to start working with more detailedobjectives or to jointly decide to ‘pause’ the aspectsupon which the disagreement touches and return tothem later.

The reporting of activities in 30-minutes segmentsduring the day can also contribute to the experiencethat the instrument is too extensive. Studies haveshown that a diary method may enable an under-standing of the complexity of daily occupation, butthat it is gives ‘… limited information regarding theaction sequences that compose an occupation andhow these are distributed in time’ [35]. By reportingthe activities in short time periods, the hope is thatthe instrument will provide a more detailed picture ofthe complexity of everyday activities for the clientthan reporting each hour.

Adding more examples to the manual and illustrat-ing the adaptation potential of the instrument willhopefully reduce these limitations. Assessing the cli-ent’s ability to participate in using the instrument is a

process that must be undertaken with great profes-sional consideration. ‘How should the instrument beapplied together with this unique client?’ is oneimportant question the occupational therapist mustconsider. For example, if working with all four life-style habits at all hours of the day, Form A, might betoo extensive for the client, and maybe it is better tochoose to map and work with only one lifestyle habitduring the morning. The possibility of making differ-ent choices in the application of the instrument wasappreciated by the occupational therapists. This pro-vides good conditions for adapting the application ofthe instrument to each unique client.

This study indicates that application of the instru-ment may be perceived as unethical on certain occa-sions. It was mentioned, for example, that theinstrument could be perceived as challenging for cli-ents with eating disorders. As with all other interven-tions, the occupational therapist must chooseinterventions based on what the client wants to do,needs to do, and is expected to do. As mentionedabove, application of the DSL must be undertakenwith great professional awareness. This means thatinterventions should be designed and implemented inpartnership with the client, and always be related tohis/her unique everyday life and the unique experien-ces this provides [36].

The manual contains several examples of literaturethat shed light on how to promote changes in every-day occupations. For example, the occupation-basedValMO-model [37] (The Value and Meaning inOccupations Model), highlights three different valuetriads: the occupation triad, the value triad, and theperspective triad. These triads are interconnected andclarify and deepen occupation as a phenomenon.Activities that are perceived to have value and to bemeaningful can give an increased feeling of health,while activities that people feel they are forced to docan lead to a negative feeling of health. Another refer-ence is to the Model of Human Occupation [21],which is an evidence-based model that explains howand why humans choose to be active in their ownunique way. The model provides an understanding ofwhy a person is motivated to participate in occupa-tions, how habits and roles support occupations, andhow ability enables occupations. The impact of theenvironment also has a large explanatory role in thismodel. There are a few interventions described con-cerning engagement in occupations that can beapplied to support change. It is stated, for example inthe Model of Human Occupation, that advising,structuring, and encouraging can be useful strategies

10 I. KÅHLIN AND L. HAGLUND

for enabling occupational change. The modelsdescribed above show how occupation-based interven-tions can be used to support changes in lifestyle hab-its. This may well be directed towards one of thelifestyle habits that are addressed in the NG lifestyle.Interventions based on these models should be con-sidered equivalent to the recommended method ofadvanced counselling in the NG lifestyle. As can beseen from our study, the occupational therapists per-ceive that the DSL supports clients in changing theirlifestyle habits and finding strategies for change. Inaddition, the occupational therapist can give the clientguidance in this change, through partnership andapplying their professional knowledge. Here, differentmodels of occupational therapy are significant.

Methodological considerations

This was a small study with just 16 participants. Thismay seem like a small number, but we argue that ourresults are nevertheless credible. One indicator forthis statement is the feedback from the 18 occupa-tional therapists who participated in the developmentprocess, as mentioned in the section Material andmethods. The development process of the DSLresulted in a similar version of the instrument thatwas examined in this study. The 18 occupationaltherapists applied the instrument in their daily workand answered what was to a large extent the samequestionnaire as used in this study in the develop-ment process. Their feedback on the utility of theinstrument was fully in line with the results of thisstudy. Therefore, we suggest that our study has anacceptable degree of credibility despite the small num-ber of participants. However, further studies must beconducted; for example, to investigate the clients whouse the instrument in order to capture their percep-tions of its value. Furthermore, the scientific merit ofthe instrument also needs to be established, referringto Polit and Beck [27,28], in order to determine eachpart of utility. For example, one alternative could beto use a longitudinal study, focussing on intra-indi-vidual change [38] to determine how lasting thechange is over time with the occupation-based inter-ventions provided by the instrument compared withinterventions according to the recommendations inthe NG lifestyle.

Conclusion

The instrument ‘Diary-based survey of lifestyle habitsin everyday activities and support for the process of

change’ demonstrated mostly positive dimensions ofutility. The instrument seems to have a high imple-mentation potential and is clinically relevant. It seemsto provide a contribution to clarifying the role ofoccupational therapy in the work to reduce unhealthylifestyles according to the NG lifestyle.

The instrument seems promising in terms of util-ity. However, the scientific merit of the instrumentwill need to be further established.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to acknowledge all the occupationaltherapists who participated in the study.

Disclosure statement

A swedish version of the instrument can be downloadedfree of charge from the Swedish Association ofOccupational Therapist’s website.

References

[1] WHO. Noncommunicable diseases. Key Facts. Juni2018. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases.

[2] Hamer M, Kivimaki M, Gale CR, et al. Lifestyle riskfactors, inflammatory mechanisms, and COVID-19hospitalization: a community-based cohort study of387,109 adults in UK. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:184–187.

[3] United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals.Goal 3: Ensure healthy lives and promote well-beingfor all at all ages. n.d. https://www.un.org/sustaina-bledevelopment/health/.

[4] WHO. The Shanghai Declaration on HealthPromotion. 2016. https://www.who.int/news/item/21-11-2016-9th-global-conference-on-health-promotion-global-leaders-agree-to-promote-health-in-order-to-achieve-sustainable-development-goals.

[5] Socialstyrelsen. Nationella riktlinjer f€or preventionoch behandling vid oh€alsosamma levnadsvanor. St€odf€or styrning och ledning [Prevention and treatmentof unhealthy lifestyles] Swedish National Board ofHealth and Welfare; 2018. Swedish.

[6] Jaffe E. The role of occupational therapy in diseaseprevention and health promotion. Am J OccupTher. 1986;40:749–752.

[7] Wilcock AA. An occupational perspective of health.Thorofare (NJ): SLACK; 2006.

[8] Fischer AG. Occupation-centred, occupational-focused: same, same or different? Scan J OccupTher. 2014;21:96–107.

[9] Word federation of occupational therapist (WFOT).About occupational therapy. https://www.wfot.org/about/about-occupational-therapy.

[10] Ramafikeng MC, Roshan G, Amesun SL. Tobaccouse and concurrent engagement in other risk behav-iours: a public health challenge for occupational

SCANDINAVIAN JOURNAL OF OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY 11

therapists. S Afr j Occup Ther. 2019;49:26–35.http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2310-3833/2019/vol49n1a5

[11] Andersson C, Eklund M, Sundh V, et al. Women’spatterns of everyday occupations and alcohol con-sumption. Scand J Occup Ther. 2012;19:225–238.

[12] Johannessen A, Engedal K, Helvik AS. Use and mis-use of alcohol and psychotropic drugs among olderpeople: is that an issue when services are plannedfor and implemented? Scand J Caring Sci. 2015;29:325–332.

[13] Chippendale T, Gentile PA, James MK.Characteristics and consequences of falls amongolder adult trauma patients: considerations for injuryprevention program. Aust Occup Ther J. 2017;64:350–357.

[14] Nielsen S, Christensen J. Occupational therapy foradults with overweight and obesity: mapping inter-ventions involving occupational therapists. OccupTher Int. 2018;2018:7412686.

[15] Conn A, Bourke N, James C, et al. Occupationaltherapy intervention addressing weight gain andobesity in people with severe mental illness: a scop-ing review. Aust Occup Ther J. 2019;66:446–457.

[16] Marik TL, Roll SC. Effectiveness of occupationaltherapy interventions for musculoskeletal shoulderconditions: a systematic review. Am J Occup Ther.2017;71:1–11.

[17] Siegel P, Tencza M, Apodaca B, et al. Effectivenessof occupational therapy intervention for adults withrheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Am JourOccup Ther. 2017;2017:71–71.

[18] Brown C, Read H, Stanton M, et al. A pilot study ofthe nutrition and exercise for wellness and recovery(NEW-R): a weight loss program for individualswith serious mental illnesses. Psychiatr Rehabil J.2015;38:371–337.

[19] Hill A, Vickrey B, Cheng E, et al. A pilot trial of alifestyle intervention for stroke survivors: design ofhealthy eating and lifestyle after stroke (HEALS). JStroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2017;26:2806–2813.

[20] Pettersson C, Iwarsson S. Evidence-based interven-tions involving occupational therapists are needed inRe-Ablement for older Community-Living people: asystematic review. Br J Occup Ther. 2017;80:273–285.

[21] Taylor RR. (ed). Kielhofner’s model of human occu-pation, 5th ed, Philadelpia (PA): Wolters KluwerHealth/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2017.

[22] The American Occupational Therapy Association.Acc Aug 2021. https://www.aota.org/About-Occupational-Therapy/Professionals.aspx.

[23] Orban K, Edberg A-K, Erlandsson L-K. Using atime-geographical diary method in order to facilitate

reflections on changes in patterns of daily occupa-tions. Scand J Occup Ther. 2012;19:249–259.

[24] Kennedy-Behr A, Hatchett M. Wellbeing andengagement in occupation for people withParkinson’s disease. Br J Occup Ther. 2017;80:745–751.

[25] Haglund L. Kartl€aggning av levnadsvanor underaktivitet och st€od i f€or€andringsprocessen [Diary-based survey of lifestyle habits in everyday activitiesand support for the process of change]. Nacka: TheSwedish Association of Occupational Therapists;2020. Swedish.

[26] Karstensen JK, Kristensen HK. Client-centred prac-tice in Scandinavian contexts: a critical discourseanalysis. Scand J Occup Ther. 2021;28:46–62.

[27] Polit DF. Beck Ct Nursing research: principles andmethods. 7th ed. Philadelphia (PA): Lippincott;2004.

[28] Polit D, Beck CT. Nursing research: generating andassessing evidence for nursing practice. 8th ed.Philadelphia (PA): Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;2008.

[29] Reilly M. Occupational therapy can be one of thegreat ideas of 20th century medicine. Am J OccupTher. 1962;16:1–9.

[30] Wilcock AA, Hocking C. An occupational perspec-tive of health. 3rd ed., Thorefare (NJ): Slack; 2015.

[31] Swedish Research Council. Good research practice.2017. https://www.vr.se/english/analysis/reports/our-reports/2017-08-31-good-research-practice.html.

[32] Haglund L, Henriksson C. Activity-from action toactivity. Scand J Caring Sci. 1995;9:227–234.

[33] Hill NL, Mogle J, Whitaker EB, et al. Sources ofresponse bias in cognitive self-report items: Whichmemory are you talking about? Gerontologist. 2019;59:912–924. Geront.

[34] Althubaiti A. Information bias in health research:definition, pitfalls, and adjustment methods. JMultidiscip Healthc. 2016;9:211–217.

[35] Erlandsson L-K, Eklund M. Describing patterns ofdaily occupations – a methodological study compar-ing data from four different methods. Scand JOccup Ther. 2001;8:31–39.

[36] Arbetsterapeuter S. Etisk kod f€or arbetsterapeuter[Code of ethics for occupational therapists]. Nacka:The Swedish Association of Occupational Therapists;2020. Swedish

[37] Erlandsson L-K, Persson D. ValMO model – occu-pational therapy for a healthy life by doing. Lund:Studentlitteratur; 2020.

[38] Grimm KJ, Davoudzadeh P, Ram N. IV develop-ments in the analysis of longitudinal data. MonogrSoc Res Child Dev. 2017;82:46–66.

12 I. KÅHLIN AND L. HAGLUND