DEIR EL-GEBRAWI Volume III THE SOUTHERN CLIFF The Tomb of Djau/Shemai and Djau

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of DEIR EL-GEBRAWI Volume III THE SOUTHERN CLIFF The Tomb of Djau/Shemai and Djau

The Australian Centre for Egyptology

Report 32A Division of the Macquarie University Ancient Cultures Research Centre

DEIR EL-GEBRAWI

Volume III

THE SOUTHERN CLIFF

The Tomb of Djau/Shemai and Djau

N. Kanawati

With contributions by E. Alexakis, S. Ikram, A. McFarlane, M. Schultz, S. Shafi k, E. Thompson, N. Victor and R. Walker

© N. Kanawati 2013. All rights reserved

ISBN: 978-0-85668-855-3

Published in England by: Aris and Phillips Ltd.Park End Place, Oxford OX1 1HN

CONTENTS LIST OF PLATES PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ABBREVIATIONS TOMB S12 I THE TOMB OWNERS, THEIR FAMILIES AND

DEPENDENTS II DATES, IDENTITIES AND CAREERS OF THE TOMB

OWNERS III ARCHITECTURAL FEATURES IV BURIAL APARTMENTS V SCENES AND INSCRIPTIONS VI FINDS VII HUMAN REMAINS

The Mummification of Djau S. Ikram Report on the Mummy of Djau M. Schultz and R. Walker TOMB S10 I ARCHITECTURAL FEATURES II BURIAL APARTMENTS III OBJECTS INDEX PLATES

6

8

9

11

19

26

27

29

56

60

64

79

79

80

81

83

6

LIST OF PLATES

1. (a) The tomb of Djau and others (b) Djau, chapel, looking east

2. Chapel (a) Looking west (b) Looking north

3. Chapel, south wall (a) East section (b) East section, detail

4. Chapel, south wall, east section (c) Detail (d) Detail

5. Chapel, south wall (a) East section, detail (b) West section

6. Chapel, south wall, west section (a) Detail (b) Detail

7. Chapel (a) South wall, west section, detail (b) West wall

8. Chapel, west wall (a) South (b) South, detail

9. Chapel, west wall, south (a) Detail (b) Detail

10. Chapel, west wall, south (a) Detail (b) Detail

11. Chapel, west wall, south (a) Detail (b) Detail

12. Chapel, west wall, south (a) Detail (b) Detail

13. Chapel, west wall, centre 14. Chapel, west wall, north 15. Chapel, west wall, north

(a) Detail (b) Detail

16. Chapel (a) West wall, north, detail (b) North wall, west section

17. Chapel, north wall, west section (a) Detail (b) Detail

18. Chapel, north wall, west section (a) Detail (b) Detail

19. Chapel, north wall, east section 20. Chapel, north wall, east section

(a) Detail (b) Detail

21. Chapel, north wall, east section (a) Detail

(b) Detail 22. Chapel, north wall, east section

(a) Detail (b) Detail

23. Chapel (a) East wall (b) East wall, detail

24. Chapel, east wall, detail 25. Chapel, east wall, detail 26. Chapel, east wall

(a) Detail (b) Detail

27. Offering recess (a) General view (b) West wall

28. Offering recess, west wall (a) Detail (b) Detail

29. Offering recess, north wall 30. Offering recess, north wall

(a) Detail (b) Detail

31. Offering recess, north wall (a) Detail (b) Detail

32. Offering recess, north wall, detail 33. Offering recess

(a) East wall (b) East wall, detail

34. Offering recess, east wall, detail 35. Finds, inscribed schist tablet (DGS06:1)

(a) Front view (b) Side view

36. Finds (a) Inscribed schist tablet (DGS06:1) (b) Base of model limestone ritual set (DGS06:2)

37. Finds (a) Side view of base of model limestone ritual

set (DGS06:2) (b) Model jar of alabaster (DGS06:3)

38. Finds, wooden objects (a) Handle of miniature stp-adze (DGS06:4) (b) Headrest (DGS06:5) (c) Staff (DGS06:6)

39. Finds, pottery (a) DGS06:7 (b) DGS06:8 (c) DGS06:9

40. Burial chamber (a) At time of discovery (b) Djau’s remains in situ

41. Mummy of Djau (a) Detail (b) Detail

LIST OF PLATES

7

42. (a) The mummy of Djau before the investigation was carried out

(b) Right femur still wrapped in linen bandages (c) The right eye of Djau 43. (a) View at the scalp and skull vault of the right

parietal region (b) Dorsal view of the metatarsus of the right

foot. Remaining muscles are very brittle (c) Lateral view of the right foot. Well-preserved

ligaments and joint capsule 44. (a) Large fragment of the abdominal wall. White

crystals on external surface. Note wrinkles of external abdominal wall

(b) Small piece of soft tissue covered by white fungus

(c) Left shoulder region stuffed with multi-layered pad-like linen bandages

45. (a) Detail of the left shoulder region presenting the multi-layered wrappings

(b) X-ray image (anterior-posterior) of the left shoulder region presenting the multi-layered wrappings, beads within the linen layers and some osteoporotic changes in the proximal humerus

(c) X-ray image (posterior-anterior) of the left femur presenting the multi-layered bandages

(d) Detail out of (b). X-ray image of beads within the linen layers

46. (a) Head of Djau (b) Right hipbone (c) X-ray image of the right hipbone (lateral) 47. (a) Right external view of the mandible.

Periodontal disease. Large abscess in region of first molar.

(b) Face of Djau. Three upper incisors are damaged postmortem

48. (a) X-ray image of the proximal end of the right humerus (anterior-posterior). Bone loss in the compact and spongy tissue

(b) X-ray image of the distal end of left tibia (anterior-posterior). Bone loss in the compact spongy tissue. No HARRIS’s lines developed

(c) Dorsal view of right little toe. Osteophytic changes in the proximal interphalangeal joint after trauma. Distal interphalangeal joint fused (Symphalangism)

(d) Distortion of the right inferior tibiofibular joint. Overstretching of the ligaments provoked bony changes

49. (a) Ventral view of right patella. Small exostoses due to insertion of quadriceps muscle

(b) X-ray image of the right heel bone (lateral). Small inferior heel spur at the plantar face of the bone. The arch-like structure of the spongy bone trabeculae tells us that Djau did not suffer from a flat foot

(c) Dorsal view of tarsal-metatarsal joints of the right foot. Supernumerary foot bone (arrow)

50. (a) X-ray image (anterior-posterior) of the sacrum. Sacralization of the fifth lumbar vertebra

(b) X-ray image (lateral) of the skull

(c) X-ray image (anterior-posterior) of the proximal end of the right femur

51. (a) Condyles of the right femur. Pronounced changes of degenerative joint disease

(b) Condyles of the right tibia including the two menisci. Pronounced changes of degenerative joint disease

(c) X-ray image (axial) of the seventh thoracic vertebra. Rotation of vertebra and pronounced changes of degenerative joint disease

52. Objects in tomb S10 (a) Fragment of base of model limestone ritual set

(DGS05:1) (b) Wooden comb (DGS05:2)

53. Architecture (a) Plan (b) Section B-B

54. Section A-A and shafts with section plans 55. East entrance thickness 56. West entrance thickness 57. Chapel, south wall, east section 58. Chapel, south wall, west section 59. Chapel, west wall, south 60. Chapel, west wall, north 61. Chapel, north wall, west section 62. Chapel, north wall, east section 63. Chapel, east wall, north 64. Chapel, east wall, south 65. Offering recess, entrance frame 66. Offering recess, west wall 67. Offering recess, north wall 68. Offering recess, east wall 69. Chapel, south wall, east section, after Davies,

Deir el-Gebrâwi 2, pl. 5 70. Chapel, south wall, west section, after Davies,

Deir el-Gebrâwi 2, pl. 3 71. Chapel, south wall, west section, after Davies,

Deir el-Gebrâwi 2, pl. 4 72. Chapel, west wall, north, after Davies, Deir el-

Gebrâwi 2, pl. 6 73. Chapel, west wall, south, after Davies, Deir el-

Gebrâwi 2, pl. 7 74. Chapel, north wall, west section, after Davies,

Deir el-Gebrâwi 2, pl. 9 75. Chapel, north wall, east section, after Davies,

Deir el-Gebrâwi 2, pl. 10 76. Chapel, east wall, after Davies, Deir el-

Gebrâwi 2, pl. 8 77. Offering recess, west wall, after Davies, Deir

el-Gebrâwi 2, pl. 11 78. Offering recess, north wall, after Davies, Deir

el-Gebrâwi 2, pl. 12 79. Offering recess, east wall, after Davies, Deir el-

Gebrâwi 2, pl. 13 80. Finds, fragments 81. Finds, objects 82. Finds, pottery 83. Tomb S10, architecture

(a) Plan (b) Section A-A (c) Section B-B

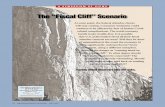

DJAU/SHEMAI AND DJAU

64

Report on the Mummy of Djau, Governor of Upper Egyptian Provinces 8 and 12 (6th Dynasty)

M. Schultz, Department of Anatomy, University of Göttingen, Germany

R. Walker, Institute of Bioarchaeology, London, U.K. Pls. 42-51

Following an invitation from Prof. Naguib Kanawati in February 2007, the authors

had the opportunity to study the damaged mummy of Djau who lived during the reign of King Pepy II, more than 4,000 years ago. As Djau was the governor in Upper Egypt of nomes 8 and 12, he was one of the most influential and powerful persons of his time.

The results of anthropological and paleopathological examinations of archaeological

skeletons, mummies and bog bodies allow, as a rule, the reconstruction of the personal status (e.g., sex, age, body height, physical constitution), as well as the health/disease status (e.g., diseases an individual suffered during a lifetime or a possible cause of death). Also, within certain limits, the biography of a deceased individual (Schultz 2011) and, roughly estimated, the ancient living conditions (e.g., the nature of everyday life, including nutrition and certain housing and working conditions, cf. Schultz 1982) can be assessed. The routine arsenal of modern paleopathology comprises macroscopic and low-power microscopic, endoscopic, radiological, as well as light and scanning-electron microscopic techniques. Additional techniques, for example, using physical (e.g., stable isotopes), chemical (e.g., drugs, such as nicotine, cocaine), biochemical (e.g., extracellular bone matrix proteins), and molecular biological (e.g., aDNA, proteins) techniques complete the traditional spectrum used in physical anthropology and paleopathology (Schultz et al. 2003). These very useful, however admittedly invasive, techniques could not be employed for the investigation of Djau’s mummy, as permission to take samples for these examinations was not granted. Thus, for instance, the age of Djau could only be estimated by the traditional macroscopic techniques, without the use of the histomorphometric (e.g., Kerley and Ubelaker 1978) or the histomorphological age determination (e.g., Nováček et al. 2008, Schultz and Nováček 2012, Wolf 1999). Diseases could only be diagnosed using macro-morphological features which render diagnoses less reliable than those deduced from microscopic and radiological examinations.

The aim of this investigation was to describe Djau’s biological identity, his possible

living conditions and the diseases he had survived from the biological findings. This means at least to establish, of course within limits, the biography of Djau at the biological level (cf. Schultz 2011). Additionally, some new aspects of a rare kind of mummification apparently practiced, although only for a short time, during the Old Kingdom are briefly mentioned from the medical point of view.

DJAU/SHEMAI AND DJAU

65

Materials and Methods

The mummy of Djau was discovered in his burial chamber at Deir el-Gebrawi near Assiut in 2006 by Prof. Kanawati and his team from Macquarie University, Sydney. During the field season of 2007, the mummy was investigated by the authors using anthropological and paleopathological methods and techniques. One year later, in 2008, the second author of this paper X-rayed parts of the mummy of Djau with a portable X-ray machine (Institute of Bioarchaeology, British Museum, London, UK). As the mummy was severely damaged, the bones of many parts of the body could be studied directly (Pl. 42a). These bones were relatively well preserved, which is not always the rule in Egyptian mummies. Additionally, large portions of mummified remains as well as parts of the wrappings could be examined. The following determinations were carried out: sex (Buikstra and Ubelaker 1994; Ferembach et al. 1979; Krogman and Işcan 1986; Loth and Henneberg 1996; Sjøvold 1988), age (Buikstra and Ubelaker 1994; Ferembach et al. 1979; Kerley and Ubelaker 1978; Krogman and Işcan 1986; Szilvássy 1988; Uytterschaut 1985; Wolf 1999), measurements (Bräuer 1988; Buikstra and Ubelaker 1994), body height (Breitinger 1937; Černý and Komenda 1982; Pearson 1899; Stloukal and Hanáková 1978), dental attrition (Brothwell 1981; Perizonius and Pot 1981), and pathological changes (Brothwell 1981; Schultz 1988). Techniques used for macroscopic reconstruction and conservation were suggested by Kunter (1988). Preservation of the mummy and some remarks on the mummification procedure

Immediately after his death, Djau was carefully mummified. However, because his mummy was apparently disturbed soon after his funeral, his corpse was severely damaged (see S. Ikram, above) This would explain why, when our investigation was carried out, many parts of the mummy already had been skeletonized and disarticulated already before the body was found by the excavator (Pl. 42a). This can be seen at the broken edges of soft tissue structures and of a few bones which were covered with old patina. Not all of the bone surfaces could be studied because many parts of the skeleton were still mantled by remnants of soft tissue or linen bandages (Pl. 42b). The consistency of the bony tissues was relatively strong to crumbly. Thin soft tissue structures, particularly of the face as, for instance, the eyelids (Pl. 42c), are excellently preserved although they were not protected by linen bandages when the investigators started their work. However, these structures were so brittle that they almost fell to dust when they were touched. Thus, some morphological features could not be preserved in the field. Also other parts of the body, particularly, the skin (Pl. 43a) and parts of the musculature (Pl. 43b) were very brittle and fell to pieces.

In spite of the ancient damage to Djau’s mummy, many small anatomical details could

still be studied because the morphological structures of the mummified tissues are well-preserved. Thus, ligaments in the joint areas and articular capsules, for instance in the region of the feet (Pl. 43c), are wonderfully well preserved.

As remnants of the brain which had sagged during the process of decomposition, and

probably also of the meninges (!), were still to be found in the neurocranium and the ethmoid bone was also intact as well as the margins of the great occipital foramen, the

DJAU/SHEMAI AND DJAU

66

brain had not been removed during the mummification process. This is not unusual for a mummy dating from the Old Kingdom (cf. Schultz 1996). Inside the thorax and the abdomen, a large amount of a white pulverulent substance was found which was observed with magnifying glasses using various magnifications (5-15x). Apparently, this substance consists of small short-needled crystals of unknown origin. These crystals were also observed in the form of relatively thin layers at the external surface of the abdominal wall (Pl. 44a) which still expressed the wrinkles of the abdominal skin and had been broken by intentional demolition during the desecration of Djau’s mummy. Perhaps, these crystals are a transformation of sodium bicarbonate. Additionally, many external and internal surfaces of the preserved soft tissues were covered by a white fungus of flaky or flawed consistence (Pl. 44b).

The phenomenon of the wrinkles on Djau’s abdominal wall (Pl. 44a) tells us that Djau

at the time of his death suffered from a considerable girth which probably was the result of an opulent way of life. As during the mummification process water is extracted from the body by the natron, wrinkles will develop during the shrinking process.

Finally, another interesting phenomenon could be observed. In several regions of the

mummy, particularly in the left shoulder region (Pl. 44c) between the external layers of linen bandages, which are in this area relatively well-preserved, and the external limb surface, which is represented by a thin zone of dried mummified soft tissue and the adherent bone surface, there is a relatively dense, homogeneous, pad-like fill (Pl. 45a). This fill looks, at first sight, as though it had a herbal origin (e.g., sand couch Eltrygia juncea). However, because there is no distinct border between the external linen layers and this fill, it might only represent the rotted multilayered structure of linen bandages, decomposed by bacterial activity (due to the field situation, there was no opportunity to use laboratory equipment to clarify the real character of this material). If this is the case, we have evidence that no embalming resins had soaked the bandages of this region. Thus, this is another indication (see above, brain still in place) that this kind of mummification is different from that practiced in New Kingdom times. However, in other topographic regions, for example directly at the surface of the sternum and also at the surfaces of soft tissue structures, we have evidence of embalming resins.

In 2008, parts of the mummy of Djau were X-rayed by one of the authors (R.W.). In

the investigation of the X-ray image of the left shoulder-arm region, the multi-layered linen pad is clearly visible (Pl. 45b). According to multi-layered linen wrappings, similar results of this mummification procedure can be observed in the left thigh region (Pls. 42b, 45c). Additionally, in the external part of these linen wrappings in the left shoulder region, several small beads are still detectable (Pl. 45d), apparently missed by the tomb raiders.

At the time of his death, Djau was an old man with all the disabilities characteristic of

old age and the embalmers attempted to give his body a strong and muscular appearance. Thus, they chose this kind of mummification using a special fill for pad-like structures to stuff the body externally (independent of the question as to whether the fill might have been herbal, for example, of sand couch, or of linen in origin).

DJAU/SHEMAI AND DJAU

67

Physical anthropology We know that Djau was the governor in Upper Egypt of nomes 8 and 12 and lived

during the reign of King Pepy II. About his sex, there is no doubt: all relevant features of the skull (Pl. 46a), such as the glabellar region, the frontal slope and the supraorbital ridge (although both are relatively slightly expressed), the mastoid processes, the muscle attachments of the nuchal area at the occipital (not especially very well-developed), the chin area (there are no real tubercles, however, a very well-pronounced ridge) and the lower mandibular margin are characteristic of a male. The pelvis, which is the most reliable region of the skeleton to determine the sex (Pl. 46b), shows in all morphological features, such as greater sciatic notch, auricular surface, preauricular sulcus, Arc composé, pubic symphysis, lower pubic rami with the sub-pubic concavity, sub-pubic angle, obturator foramen and the alae of the sacrum, typical masculine characteristics. It can also be noted, that the external genitals (penis) of Djau were still preserved and also wrapped with remnants of linen bandages. The radiological examination of the right hipbone (Pl. 46c) confirmed the analysis of the external morphological appearance and detected an anatomical variation: in the iliac bone, the upper part of the hipbone, there is the canal of a large blood vessel which is situated, very probably, inside the bone within the spongy bone substance (Pl. 46c).

At first sight, Djau’s age is not easy to determine. This might be surprising because

not only the skeleton but also some soft tissue parts of the corpse were available for investigation. However, there apparently is a certain discrepancy in the attrition of his teeth which, as a rule, provides reliable information about the age of an individual. While Djau’s molars and premolars exhibit in the mandible an abrasion degree (Brothwell 1981; Perizonius and Pot 1981) of 3 or 3+ and in the maxillae of 3+ and 4 (5) (Pl. 47a), the canines and the incisors present in the mandible the degrees of 3 and 4 and in the maxillae degrees of 4 and 5 (Pl. 47b). This discrepancy between the abrasion of the teeth of the lower and the upper jaws has probably something to do with habitual chewing. Thus, we obtain for the abrasion of the teeth of the lower and the upper jaws an average age of approximately 30–45 (50) years (cf. Brothwell 1981). However, the obliteration of the skull sutures suggests an age of between 40 and 60 (65) years and the condition of the face of the pubic symphysis indicates an age of more than 50 or even more than 60 years. This result is supported by the findings of the advanced osteophytic ossification of bony rib ends and the mineralization of rib cartilages and the thyroid cartilage as well as in the synostosis of the parts of the hyoid which give us altogether an age of more than 60.

Now, back to the teeth. It is well-known that the teeth of elderly Egyptians were

severely worn down due to the coarse flour which was used to bake bread and which was mixed with small sand particles from the stone mills and the desert. Thus, as a rule, ancient Egyptians aged 30–40 years presented a degree of tooth abrasion which was found in other past populations of agriculturalists at a considerably greater age. Therefore, the abrasion of Djau’s teeth should point, indeed, to an even lower age than 30–45 (50) years. As an explanation for this irritating little conclusion about the state of abrasion of Djau’s teeth, we have to consider the fact that Djau was a member of the absolute elite of his time. Thus, it is very probable that his food was not the same as that at the disposal of the average Egyptian, which means that very probably his bread was of a better and softer quality and so contributed less to dental attrition. In addition, as a high

DJAU/SHEMAI AND DJAU

68

status individual, Djau would have had access to more and better quality protein foods such as meat, fish and poultry, as well as vegetables and fruits, and therefore would possibly have consumed less bread

If we include all aforementioned facts, we can estimate the age at death of Djau to

have been between (50) 55-60 (65). The external morphology of the skull and cranial measurements (carried out on the

bones without removing remnants of soft tissue) tell us that Djau was apparently on the whole a typical representative of the indigenous population of the Nile Valley during the time of the Old Kingdom (Table 1 and Table 2). Although Djau had a relatively long head (190mm) he also had a relatively wide one (145mm), altogether a relatively large one (Pl. 46a). Thus, his cranial index is 76.3 (mesocran). Regarding the non-metric traits, Djau does not present noteworthy characteristics (Table 3). However, many of the landmarks necessary for observation of metric measurements (see Pl. 42b) and non-metric traits remained inaccessible because of the presence of the soft tissue and, even via radiographs, not all morphological features were detectable.

ELEMENT Left Right

Maximal Cranial Length 190 Maximal Cranial Breadth 145 Bizygomatic Diameter 126.5 Cranial Base Length 103.4 Basion-Prosthion Length 94.5 Maxillo-Alveolar Breadth 39.7 Maxillo-Alvolar Length 50.6 Biauricular Breadth 92.9 Upper Facial Height 74.5 Minimum Frontal Breadth 95.2 Upper Facial Breadth 106.6 Nasal Height 49.2 Nasal Breadth 25.6 Orbital Breadth 40.1 40.1 Orbital Height 35.8 35.8 Biorbital Breadth 94.2 Interorbital Breadth 22.8 Foramen Magnum Length 36.5 Foramen Magnum Breadth 26.4 Mastoid length 29.4 27.7 Chin Height 32.2 Mandibular Body Height 30.4 30.36 Mandibular Body Breadth 12.17 Bigonial Width 148.4 Bicondylar Breadth 119.7 Minimum Ramus Breadth 29.4 Maximum Ramus Breadth 37.6 35.3 Maximum Ramus Height 28.2 Mandibular Length 76.9 Mandibular Angle 120 est. 120

Table 1. Djau, cranial metrics (in mm.)

DJAU/SHEMAI AND DJAU

69

ELEMENT Metric Left Side Right Side Midline

Scapula Height 160 Breadth 107 Glenoid Fossa Length 40

Humerus Max. Length 343 Vertical Head Diam. est. 47.1 Midshaft Max. Diam. 20.5 Midshaft Min. Diam. 17.1 Epicondyle Breadth 64.8

Radius Max. Length 263 Midshaft A/P Diam. 12.8 Midshaft M/L Diam. 12.3

Ulna Max. Length 278 280 Physiological Length est. 253 est. 254 A/PDiam. 18.9 M/L Diam. 11.9 Min. Circum. 36 35

Sacrum Anterior Length est. 130 A/S Breadth 106.5 Max. Trans. Base Diam. 51.5

Femur Max. Length 474 473 Bicondylar Length 470 471.5 Max. Head Dia. 43.9 44.9 Epicondylar Breadth 76.9

Tibia Max. Length 408 410 Max. Prox. Epi. Breadth 76 75 Max. Dia. at Nut. For. 34.6 M/L Dia. at Nut. For 24.1 Midshaft A/P Dia. 27.6 Midshaft M/L Dia. 22 Max. Dis.Epi. Breadth est. 49.6 Circum. at Nut. For. 95 Midshaft Circum. 88

Fibula Max. Length 399 Midshaft Max. Diam. 21

Calcaneus Max. Length 86 Middle Breadth 41.1

Table 2. Djau, postcranial metrics (in mm.)

TRAIT Left Side Midline Right Side Metopic Suture 0 Supraorbital Notch Bridging 0 0

Brematic Ossicle 0 Sagittal Stture Ossicle(s) 0 Parietal Foramen + + Epipteric/Pterionic Bone 0 Accessory Mental Foramen 0 0 Mylohyoid Bridge Mandibular Torus 0 0

Table 3. Djau, cranial nonmetrics 0 = Absent + = Present Blank = Not observed

DJAU/SHEMAI AND DJAU

70

Djau’s stature was calculated from measurements based on humerus, radius, femur and tibiae (Table 2) which give us values of 172 and 180 cm (Pearson, 1899: 172.1cm; Breitinger, 1937: 179.5 cm; Černý and Komenda,1982: 177cm). Thus, the average value is about 176cm which is relatively tall for ancient Egyptians.

The postcranial skeleton of Djau, particularly his long bones, were not very robust (Pl.

45b-c). He had relatively long tubular bones, his sternum was relatively narrow (manubrium: height 50mm, width 54mm; corpus: length including xiphoid 96mm, greatest width 27mm) and his clavicles relatively short. Thus, his constitutional type possibly might have tended towards the asthenic type rather than the normosome/athletic type.

His musculoskeletal system was seemingly not very strong (listed here are only those

attachments which were observable because they were not covered with mummified soft tissue remains): deltoid tuberosity of the right humerus for the insertion of the deltoid muscle (Pl. 48a) very slightly pronounced; crest of the greater tubercle of the right humerus for the insertion of the greater pectoral muscle (Pl. 48a) only moderately developed; crest of the smaller tubercle of the right humerus for the insertion of the latissimus dorsi muscle and the teres major muscle (Pl. 48a) only very slightly pronounced; medial epicondyle of the right humerus, a part of the origin of the flexor muscles of the hand, relatively strongly developed; the lateral epicondyle, a part of the origin of the extensor muscles of the hand only moderately pronounced; radial tuberosity of the left radius for the insertion of the biceps muscle weakly developed; ulnar tuberosity of the left ulna for the insertion of the brachial muscle relatively weakly developed; attachments of the muscles for the left lower arm and the left hand (ulna) relatively slightly to moderately pronounced. Apparently, only the abdominal trunk muscles were extremely well-pronounced: at both iliac crests (Pl. 46b-c); the attachment of the external oblique abdominal muscles shows exostotic enlargements (length of exostoses: right and left 3-4mm).

It is difficult to determine whether Djau was right or left-handed. Probably, he was

right-handed because the joints of his right arm are slightly more affected by degenerative joint disease (elbow joints and right radio-ulnar joint.). Unfortunately, neither all joints and muscle attachments nor the length of the long arm bones could be studied because soft tissue structures covered the bone surfaces. The radiological investigations provide some clues. It seems that the bone structure of the humerus, according to the compact and the spongy bone substance, was at the left side less dense (Pls. 45b, 48a). Additionally, the spongy bone substance in the proximal end of the left humerus is slightly reduced (Pl. 45b). Thus, the question of handedness does indeed show only a very slight tendency towards the right hand. Paleopathology

The results of the paleopathological investigation carried out in 2007 are described below. As one of the authors (M.S.) was unable to participate in the second field season, the investigation could not be completely finished.

DJAU/SHEMAI AND DJAU

71

Diseases in infancy and childhood Not very much can be said about the health situation of Djau in infancy and childhood.

However, there are slight transverse linear enamel hypoplasias in the teeth (degree I-II, or even only 0-I, cf. Schultz 1988). It is well known that transverse linear enamel hypoplasias and HARRIS's lines (radio-dense transverse lines in the metaphyses of the shafts of the long bones due to arrested growth) are reliable stress indicators for subadults. Fortunately, the long bones of Djau could be X-rayed in the field at Deir el-Gebrawi in 2008 by one of the authors (R.W.). Still, no information could be obtained about this kind of stress marker because HARRIS's lines were not detected in Djau’s bones (Pl. 48b). The absence of these radio-dense lines might be due to the fact that they are sometimes remodelled during a lifetime. Additionally, the enamel hypoplasias were examined and their locations at the tooth crowns document the age at which the lines originated (cf. Ubelaker 1978). Thus, for Djau, we can say that he suffered twice from longer-lasting or severe diseases in his childhood (or from starvation which is, however, not very likely because Djau was a person of the elite of his time) and this must have happened once when he was about one and a half (18 months + 6 months) and once at about three (3 years + 12 months). From an examination of transverse linear enamel hypoplasias or HARRIS’s lines only the quantity but not the quality of stress can be investigated. In accordance with the fact that his skeleton was not very robust but more gracile, Djau, as a young adult, did not develop strong musculature in the upper and the lower extremities. Evidence of trauma

We have only one slight indication of bone fracture. In his right foot, the middle and the

distal phalanges of the little toe show a bony fusion (Pl. 48c). As this fusion is very regular, this morphology was very probably caused genetically (here, we speak about symphalangism). However, in the same toe, there is evidence of a traumatic event which probably was associated with a luxation of the proximal interphalangeal joint (Pl. 48c). A small exostosis in the shape of an osseous spur (length 6mm, width 4.5mm) had developed after trauma on the plantar surface at the proximal edge of the middle phalanx (Pl. 48c). Normally, the distal articular surface of the basic phalange is built up as a trochlea. In this case, however, the trochlea is deformed and slightly rolled out as an osteophytic formation which articulates with the aforementioned spur. Thus, a traumatic disturbance is very feasible. The most probable cause of the lesion was, therefore, the luxation of this interphalangeal joint which was associated with a fracture of the edge of the articular surface. The lesion healed under limited function by ossification of parts of the capsule. Because of this traumatic event, secondary degenerative joint disease developed in this joint (Pl. 48c).

There is more evidence of physical stress in the musculoskeletal system of Djau. At

the interosseous margin of the right radius, a 19mm long and 5mm high exostosis had developed just in the transition area from the proximal to the middle third of the shaft. This exostosis is the product of a traumatic event, a distraction of the long abductor muscle of the right thumb which has its origin at this position. The cause of this muscle-tendon damage (Myotendopathia) might have been, for example, a serious accidental fall and, probably, was associated with longer lasting pain. We cannot exclude the possibility that this event might have happened when Djau also suffered from the painful distortion of his right inferior tibiofibular joint (Syndesmosis tibiofibularis distalis) accompanied by

DJAU/SHEMAI AND DJAU

72

overstretching of the ligaments which also must have produced severe changes. After healing, characteristic bony features in the form of newly built formations remained at the attachments of the ligaments (Pl. 48d). Based on the stage of healing and the remodelling of the bony structures in both cases, it seems possible that one and the same traumatic event (e.g., accidental fall) might have been responsible for these changes. Possibly, the changes observed in the interphalangeal joint of the little toe of the right foot described above, could have been associated with this event.

Vestiges of constant physical load of the quadriceps muscle which is the most

important muscle for the extension in the knee joint, can be observed at the upper edge of the right patella (Pl. 49a). Here, micro-trauma led to the kind of very small hemorrhages which, in the course of healing, provoked an ossification of the fibers of the attaching tendon. Frequently, the same phenomenon can be observed in the inferior heel spur, and indeed, Djau also suffered from this affliction as the X-ray image shows (Pl. 49b). This morphological feature is located at the plantar face of the calcaneus, causes pain in the spur region and is found in flat-footed and obese individuals. Anatomical variations

In the right foot, Djau had developed a supernumerary bone which measures 7mm in

diameter and is situated at the dorsal face of the proximal metatarsus exactly in the angle between the first cuneiform bone and the first and the second metatarsals (Pl. 49c). This variation does not provoke pain, as a rule.

In the lumbar vertebral column, there are only four vertebrae. The 5th lumbar vertebra

is expressed as a lumbo-sacral transitional vertebra (sacralization), which means that it was changed during its development to the first element of the sacrum (Pl. 50a). Additionally, the 1st vertebra of the coccyx, ossified with the sacrum, broke away during the investigation due to its brittleness. There is deviation of the coccyx which is probably not an anatomical variation but the result of an accidental fall. Diseases manifested in skull bones

The macroscopic and radiological examinations of Djau’s skull (Pls. 46a, 50b) did not

provide vestiges of diseases localized at the skull surfaces (e.g., skull vault), in the pneumatic spaces (e.g., paranasal sinuses) nor the skull cavities (e.g., endocranial cavity). This is astonishing because, as a rule, many diseases diagnosed in paleopathology in archaeological skeletons or mummies cause vestiges in the skull. Of course, due to the fact that the corpse of Djau is still a mummy, many topographic features could not be investigated macroscopically (e.g., the venous blood sinuses of the brain, the cranial cavities of the skull base, the tympanic cavity of the middle ear region). Thus, we can only state that some morphological variations were developed, such as symmetrical, relatively narrow external auditory canals. Interestingly, Djau had a straight nasal septum (Pl. 47b and probably had no difficulties with breathing while sleeping.

In the lateral X-ray image of the skull (Pl. 50b), the cavity of the pituitary gland seems

to be relatively large. This (in Djau’s case) borderline morphology does not necessarily

DJAU/SHEMAI AND DJAU

73

have to do with a beginning pathological process (e.g. acromegaly), since a slight enlargement of the pituitary gland is relatively frequently seen in elderly people. Diseases of the teeth and the jaws

The condition of Djau’s teeth was, in comparison with the average Egyptian of his

time and even with other members of the absolute elite (cf. Schultz et al. 2003), excellent. Djau did not lose teeth during his lifetime; however, other than his right upper third molar, none of his wisdom teeth were developed (aplasia).

The tooth sockets and their external regions in the alveolar bone show only slight

vestiges of periodontal processes (periodontosis and periodontitis) in both maxillae and the mandibula. No dental abscesses were found in the maxillae and the mandibula. Dental pockets were only present around three mandibular molars. The attrition of the tooth crowns was moderately to highly advanced (degree: 3-5; Brothwell 1981). Dental caries could not be observed. Thus, Djau seemingly practiced a relatively sufficiently good oral hygiene. The mandibular joints show only slight vestiges of early osteoarthritis. Diseases manifested in long bones

An interesting morphological feature which is relatively frequently seen in senile

people (cf. Schultz 1996; Schultz et al. 2001) can be observed in Djau’s right tibia. At the lateral face of the shaft, the external bone surface is not, as is usual, relatively smooth, but irregularly bulky and stringy and gives the bone a relatively coarse character. Such changes are frequently associated with inflammatory processes of the deep veins (varicosis) which also might affect the periosteum of long bones which, in turn; is then responsible for such proliferative alterations.

The question comes up, whether Djau suffered from osteoporosis (e.g., old age

osteoporosis). Indeed, in the radiological record, there is evidence of osteoporotic changes. However, apparently, the upper extremities (Pls. 45b, 48a) are more severely affected than the lower extremities (Pls. 45c, 48b, 50c). Thus, presumably, we have here a case of inactivity atrophy which is not a systemic age dependent disturbance, such as senile osteoporosis. Degenerative diseases of the extremity joints

Of course, Djau suffered from degenerative joint disease (arthrosis, i.e. non-

inflammatory changes). However, all large joints of the extremities and all of the preserved small joints of the hands and the feet which were not covered by mummified soft tissue, and therefore accessible for such an investigation, only show vestiges of slight degenerative joint disease (intensity ranges between degrees I-II, cf. Schultz 1988). This is very unusual because Djau was an old man when he died. There is only one exception: both hip joints and the right knee joint (the left joint could not be examined because of the presence of soft tissue) presented the characteristic vestiges of advanced degenerative disease (here, the intensity is expressed as degrees IV, cf. Schultz 1988). A comparison between right and left sides with regard to the disease intensity of the extremity joints could not be established because of the presence of the soft tissue (the

DJAU/SHEMAI AND DJAU

74

investigators had no desire to deflesh the mummy of Djau which was already severely damaged by the tomb raider in ancient times).

The degree of the disease’s state (e.g., degrees between I-VI, cf. Schultz 1988) of each

joint surface allows the calculation of a rating index for each joint (cf. Schultz 1988). Here, these rating indices are presented: right shoulder joint 1.5; elbow joint right 1.8 / left 1.5 (incomplete); radio-ulnar joint right 1.5 / left 1.0; proximal hand joint right / left 1.5; hip joint (only acetabulum available, therefore, no rating index possible) right and left degree IV; right knee joint (only condyles of femur available (Pl. 51a), tibial condyles still partly covered by menisci (Pl. 51b), no rating index possible) medial condyle degree IV, lateral condyle degree II; proximal foot joint (Articulatio talocruralis) right 1.0 / left (incomplete) degree I; and right distal foot joint (Articulatio talocalcaneonavicularis) 1.5.

Also the smaller joints only present slight vestiges of degenerative joint disease. The

sacroiliac joints have an rating index of 0.5 (!), the small hand and finger joints, as well as the small foot and toe joints, an index of 1.0. Only the joints of the right big toe were slightly more afflicted by arthrosis: tarso-metatarsal joint 1.0; metatarso-phalangeal joint 1.5; proximal interphalangeal joint 1.5; and distal interphalangeal joint 2.0. Thus, except for the hip and the knee joints, Djau had a joint status more like a young man. Probably, this has something to do with his high position in the ancient Egyptian society which kept him far away from physical strain and overload. The slight predominance of the rating index in the right elbow and radio-ulnar joint might support the suspicion that Djau was right handed. Diseases of the vertebral column

Djau’s vertebral column including the joints of the skull is completely afflicted by

degenerative joint disease. The cervical, thoracic and lumbar regions of the spine are more or less affected with the same frequency and intensity. However, the joints of the vertebral bodies (spondylosis or osteophytosis) are affected with higher intensity than the small joints of the vertebral arches (spondylarthrosis or degenerative spondylarthritis). Interestingly, there is no reliable difference between the degenerative changes in the small joints of the vertebral arches of the right and the left sides. Thus, Djau was never forced in his life to carry heavy loads only on one side as, for example, a manual labourer. It is striking that the slight rotation of the thoracic vertebral column to the right side, between the 6th and the 9th thoracic vertebrae (Pl. 51c), does not fit the arthrosis pattern described which shows a symmetric affliction. The intensity of the degenerative changes in the joints of the vertebral arches ranges in the cervical vertebrae, as a rule, between rating indices 1.5 and 2.0, in the thoracic vertebrae between 1.0 and 2.0, and in the lumbar vertebrae between 2.0 and 2.5. It is striking that no eburnated faces of the small joints of the vertebral arches were found.

The intensity of the degenerative changes in the joints of the vertebral bodies ranges in

the cervical vertebrae between rating indices 2.0 and 3.0, in the thoracic vertebrae between 2.0 and 4.0, and in the lumbar vertebrae between 3.5 and 4.0.

DJAU/SHEMAI AND DJAU

75

All these degenerative changes in the vertebral column of Djau have to be described as age-based. It is important to know that in ancient Egypt, as a rule, much younger people suffered from more severe degenerative changes than Djau exhibited. This characterizes him as a member of the upper class.

The ossification of parts of the articular soft tissue apparatus, while not very

advanced, stretches along the whole thoracic vertebral column right down to the 3rd lumbar vertebra. Ossification of the supraspinal ligament was only found between the 4th and the 5th thoracic vertebrae. Conclusions and Summary The life and suffering of Djau – “An attempt at a biographical sketch”

Ultimately, this study should add up to a biological “biography” of Djau (cf. Schultz 2011). Skeletal remains and mummies represent primary sources which conserve many different individual data from human lives, departed long ago. Therefore, they should be regarded as bio-historic documents which tell us about ancient living conditions and the individual fate of a person from the past (cf. Kunter 1989; Schultz 1996, 2011; Schultz and Kunter 1999; Schultz and Schmidt-Schultz 1991; Schultz et al. 2001).

In this contribution, the mummy of Djau, the governor in Upper Egypt of provinces 8

and 12, was studied using macroscopic, low-power microscopic and conventional radiological techniques. Djau who represented the elite of the Sixth Dynasty in Old Kingdom Egypt, lived during the reign of King Pepy II. A relatively reliable health record from his childhood to his death at the age of (50) 55-60 (65) years has been established. The fact that Djau was able to grow relatively old is not surprising because he was a high-ranking person who had all social and economic care at his disposal.

At birth, Djau possessed some anatomical variations which were positioned at his

sacrum in the form of a transitional vertebra and a small supernumerary bone in the metatarsus of his right foot. However, these changes are unimportant and without consequences for his further life.

In detail, when he was a young child of about 1½ years and a second time, when he

was about three years old, he suffered from two episodes of arrested growth which were probably caused by infectious diseases of unknown origin. Like other members of the elite of the Old Kingdom (cf. Schultz et al. 2001, 2003) – and here we should not forget that these were rough times – he suffered from some traumatic events which, however, were only of marginal importance for his further life because the lesions represented only minor damage and healed relatively well. From his time as an adolescent we do not have any information. However, because this is the phase in one’s life where the basis is laid for intense physical exercise which is responsible for a well-trained musculoskeletal system, Djau, as his skeleton tells us, was probably not very highly engaged in such sportive, not to mention, athletic activities. This, apparently, is the reason for his gracile skeleton and his relatively under-developed muscle attachments at the bones.

DJAU/SHEMAI AND DJAU

76

Presumably he underwent the traumatic events described at a young adult age, as far as the stage of healing tells us. The three singular incidents, the luxation of the proximal interphalangeal joint of the little toe of his right foot, distraction of the long abductor muscle of the right thumb, and the distortion of his right inferior tibiofibular joint, might be related to one traumatic, probably accidental event. The development of the exostosis at the patellar attachment of the quadriceps muscle as well as the growth of the inferior heel spur at the calcaneus might have something to do with the assumption that Djau was not very well-trained in sports and was overweight. We know that these morphological changes are more frequently seen in individuals who were never very well trained physically, but exposed to a certain physical overload, such as being overweight. In the case of Djau, this might have happened in the latter phase of his adult life because these changes (inferior heel spur, exostoses at patella), as a rule, are not found in young adult individuals.

In contrast to many ancient Egyptians, Djau apparently did not suffer from chronic

infections of the paranasal sinuses, such as sinusitis maxillaris. One reason might be that the conditions of his teeth and jaws were excellent compared with the health status of the average ancient Egyptian. As is generally known, dental abscesses and periodontal diseases provoke maxillary sinusitis. Thus, Djau was again at an advantage in his living conditions as a member of the upper class. Another reason might be that Djau did not suffer from nutritional stress, such as deficiency diseases. This made his immune system strong and, therefore he was probably better protected against banal infections such as infections of the upper respiratory system (e.g., paranasal sinusitis).

During his final years, it appears Djau had problems with the deep veins of his legs

(varicosis). This affliction might also be provoked by obesity (see Pl. 44a). Furthermore, he suffered for many years from considerable changes caused by degenerative joint diseases of the vertebral column. Interestingly, only the joints of the vertebral bodies were severely affected (spondylosis), while the joints of the vertebral arches which are dorsally situated, show relatively slight degenerative changes (spondylarthrosis). As the whole musculature of the backbone (M. erector spinae) is situated dorsally of the vertebral column, a weak musculature will not be able to extend the vertebral column in the necessary way. Thus, the joints of the vertebral bodies are overloaded, but not in the same way as the joints of the vertebral arches. This phenomenon is increased in the case of an overweight individual. Thus, we have another argument that Djau might have been overweight in his older age.

The degenerative changes in the joints of the extremities were only slight, however,

with the exception of his hip and knee joint. As these two joints which are the largest of the body, are placed in line with each other in the lower extremity, they represent a functional chain. In the situation of physical overload, particularly, when the muscles which are responsible for the proper function and the coordination of these joints are weakened or not well-trained, they will be severely damaged. Apparently this was the case for Djau because these two joints were severely damaged by degenerative destruction. We know from patients these days that overweight individuals, in particular, have such problems. Thus, we cannot exclude that for many years before his death Djau was overweight, which might be an attribute not only of an ancient elite.

The cause of Djau’s death could not be discovered.

DJAU/SHEMAI AND DJAU

77

Acknowledgements The authors thank very much Prof. Dr. N. Kanawati for the invitation to work on this

skeleton and for his help in the project. Furthermore, we thank Dipl.-Biol. Susan Klingner and Dipl.-Biol. Edith Oplesch for computer work and, last but not least, very cordially, Cyrilla Cole-Maelicke, B.Sc. (Göttingen, Germany) for reading the English text as a native speaker. Literature Bräuer G (1988). Osteometrie. In: R Knussmann (ed) Anthropologie. Handbuch der vergleichenden Biologie des Menschen, Vol. 1, 1. Stuttgart: Fischer Verlag, pp. 160-232.

Breitinger E (1937). Zur Berechnung der Körperhöhe aus den langen Gliedmaßenknochen. Anthropologischer Anzeiger 14:249-274.

Brothwell DR (1981). Digging up Bones. Oxford: British Museum of Natural History, Oxford University Press.

Buikstra JE and Ubelaker DH (1994). Standards for data Collection from Human Skeletal Remains. Proceedings of a Seminar at The Field Museum of Natural History. Arkansas Archeological Survey Research Series No. 44. Fayetteville, Arkansas: Arkansas Archeological Survey.

Černý, M.; Komenda, S. (1982): Reconstruction of body height based on humerus and femur lengths (material from Czech lands). IInd Anthropological congress of Aleš Hrdlička.

Ferembach D, Schwidetzky I and Stloukal M (1979). Empfehlungen für die Alters- und Geschlechtsdiagnose am Skelett. Homo 30:1-32.

Kerley ER and Ubelaker DH (1978). Revision in the microscopic method of estimating age at death in human cortical bone . American Journal of Physical Anthropology 49:545-546.

Krogman WM and Işcan MY (1986). The Human Skeleton in Forensic Medicine. Springfield (Illinois): CC Thomas Publisher.

Kunter M (1988). Methoden der Rekonstruktion, Konservierung und Reproduktion. In: Knussmann R (ed) Anthropologie. Handbuch der vergleichenden Biologie des Menschen, Vol. 1, 1. Stuttgart: Fischer Verlag, pp. 551-615.

Kunter M (1989). Menschliche Überreste aus frühmittelalterlichen Grabfunden in Nordhessen (6.-9. Jh.). In: Sippel K (ed) Die frühmittelalterlichen Grabfunde in Nordhessen. Wiesbaden: Landesamt für Denkmalpflege in Hessen, pp. 235-277.

Loth SR and Henneberg M (1996). Mandibular ramus flexure: A new morphologic indicator of sexual dimorphism in the human skeleton. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 99:473-485.

Novaček J, Scheelen K, Drozdova E, Schultz M (2008). Ergebnisse der anthropologischen und paläopathologischen Untersuchungen an den Skelettresten der Leichenbrande vom Fundort Haiger “Kalteiche.” In: Verse F (ed) Archäologie auf Waldeshohen. Eisenzeit, Mittelalter und Neuzeit auf der “Kalteiche” bei Haiger, Lahn-Dill-Kreis. Münsterische Beiträge zur ur- und frühgeschichtlichen Archäologie, Vol. 4, Jockenhövel A (ed). Rahden/Westfalen: Verlag Marie Leidorf, 137–163.

Pearson, K. (1899): On the reconstruction of stature of prehistoric races. Mathematical contribution to the theory of evolution. V. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society A., 192:169-244.

DJAU/SHEMAI AND DJAU

78

Perizonius WRK and Pot T (1981). Diachronic dental research on human skeletal remains excavated in the Netherlands, I: Dorestad´s cemetery on „the Heul“. Berichten van de Rijksdienst voor het Oudheidkundig Bodemonderzoek 31:369-413.

Schultz M (1982). Umwelt und Krankheit des vor- und frühgeschichtlichen Menschen. In: Wendt H and Loacker N (eds) Kindlers Enzyklopädie - Der Mensch, Vol. 2., München/Zürich: Kindler-Verlag, pp. 259-312.

Schultz M (1988). Paläopathologische Diagnostik. In: Knussmann R (ed) Anthropologie. Handbuch der vergleichenden Biologie des Menschen, Vol. 1, 1. Stuttgart: Fischer Verlag, pp. 480-496.

Schultz M (1996). Paläopathologische Untersuchung der Mumie des Herrn Idu. In: Schmitz B (ed) Untersuchungen zu Idu II, Giza. Ein interdisziplinäres Projekt. Hildesheim: Gerstenberg Verlag, pp. 59-85.

Schultz M (2011). Paläobiographik. In: Jüttemann G (ed) Biographische Diagnostik. Lengerich/Berlin/Bremen: Pabst Science Publishers, pp. 222-236.

Schultz M and Kunter M (1999). Erste Ergebnisse der Anthropologischen und paläopathologischen Untersuchungen an den menschlichen Skeletfunden aus den neuassyrischen Königinnengräbern von Nimrud. Jahrbuch des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums Mainz 45 (Jahrgang 1998):85-128.

Schultz M and Nováček J (2012). Ergebnisse der lichtmikroskopischen Untersuchung an den menschlichen Skeletresten aus dem Tumulus auf dem İlyastepe. In: Pirson F, Japp S, Kelp U, Nováček J, Schultz M, Stappmann V, Teegen W-R and Wirsching A: Der Tumulus auf dem İlyastepe und die pergamenischen Grabhügel. Istanbuler Mitteilungen 61:165-181.

Schultz M and Schmidt-Schultz TH (1991). Ergebnisse osteologischer Untersuchungen an menschlichen Skeletfunden aus Milet. Istanbuler Mitteilungen 41:163-186.

Schultz M, Walker R, Strouhal E and Schmidt-Schultz TH (2001). Skeletal remains of Merinebti, Hefi and Iries. In: Kanawati N (ed) The Teti cemetery at Saqqara: the tombs of Shepsipuptah, Mereri (Merinebti), Hefi and others. Warminster: Aries and Philipps, pp. 18-34.

Schultz M, Walker R, Strouhal E and Schmidt-Schultz TH (2003). Report of the skeleton Jj-nrft excavated from his mastaba of Uni’s Pyramid (5th Dynasty). In: Kanawati N and Abder-Raziq M (eds) The Unis cemetery at Saqqara. Oxford: Aries and Philipps, pp. 75-86.

Sjøvold TH (1988). Geschlechtsdiagnose am Skelett. In: Knussmann R (ed) Anthropologie. Handbuch der vergleichenden Biologie des Menschen, Vol. 1, 1. Stuttgart: Fischer Verlag, pp. 444-480.

Stloukal M and Hanáková H (1978). Die Länge der Längsknochen altslawischer Bevölkerungen, unter besonderer Berücksichtigung von Wachstumsfragen. Homo 29:53-69.

Szilvássy J (1988). Altersdiagnose am Skelett. In: Knussmann R (ed) Anthropologie. Handbuch der vergleichenden Biologie des Menschen, Vol. 1, 1. Stuttgart: Fischer Verlag, pp. 421-443.

Ubelaker DH (1978). Human Skeletal Remains. Excavation, Analysis, Interpretation. Chicago: Aldine.

Uytterschaut HT (1985). Determination of skeletal age by histological methods. Zeitschrift für Morphologie und Anthropologie 75:331-340.

Wolf M (1999). Ergebnisse makro- und mikroskopischer Untersuchungen an den römischen Brandgräbern von Rheinzabern (Rheinland-Pfalz). In: Schultz M (ed): Beiträge zur Paläopathologie 3. Göttingen: Cuvillier Verlag.

Pl. 42.

(a) The mummy of Djau before the investigation was carried out. (b) Right femur still wrapped in linen bandages.

(c) The right eye of Djau.

Pl. 43.

(a) View at the scalp and skull vault of the right parietal region.

(b) Dorsal view of the metatarsus of the right foot. Remaining muscles are very brittle.

(c) Lateral view of the right foot. Well-preserved ligaments and joint capsule.

Pl. 44.

(a) Large fragment of the abdominal wall. White crystals on external surface. Note wrinkles of external abdominal wall.

(b) Small piece of soft tissue covered by white fungus.

(c) Left shoulder region stuffed with multi-layered pad-like linen bandages.

Pl. 45.

(a) Detail of the left shoulder region presenting the multi-layered wrappings.

(b) X-ray image (anterior-posterior) of the left shoulder region presenting the multi-layered wrappings, beads within the linen layers and some osteoporotic changes in the proximal humerus.

(c) X-ray image (posterior-anterior) of the left femur presenting the multi-layered bandages.

(d) Detail out of (b). X-ray image of beads within the linen layers.

Pl. 47.

(a) Right external view of the mandible. Periodontal disease. Large abscess in region of fi rst molar.

(b) Face of Djau. Three upper incisors are damaged postmortem.

Pl. 48.

(a) X-ray image of the proximal end of the right humerus (anterior-posterior). Bone loss in the compact and spongy tissue.

(b) X-ray image of the distal end of left tibia (anterior-posterior). Bone loss in the compact spongy tissue. No HARRIS’s lines developed.

(c) Dorsal view of right little toe. Osteophytic changes in the proximal

interphalangeal joint after trauma. Distal interphalangeal joint fused (Symphalangism).

(d) Distortion of the right inferior tibiofi bular joint. Overstretching of the ligaments provoked bony changes.

Pl. 49.

(a) Ventral view of right patella. Small exostoses due to insertion of quadriceps muscle.

(b) X-ray image of the right heel bone (lateral). Small inferior heel spur at the plantar face of the bone. The arch-like structure of the spongy bone trabeculae tells us that Djau did not suffer from a fl at foot.

(c) Dorsal view of tarsal-metatarsal joints of the right foot. Supernumerary foot bone (arrow).

Pl. 50.

(a) X-ray image (anterior-posterior) of the sacrum. Sacralization of the fi fth lumbar vertebra.

(b) X-ray image (lateral) of the skull.

(c) X-ray image (anterior-posterior) of the proximal end of the right femur.

Pl. 51.

(a) Condyles of the right femur. Pronounced changes of degenerative joint disease.

(b) Condyles of the right tibia including the two menisci. Pronounced changes of degenerative joint disease.

(c) X-ray image (axial) of the seventh thoracic vertebra. Rotation of vertebra and pronounced changes of degenerative joint disease.