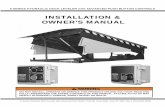

Cyberspace, Y2K: Giant Robots, Asian Punks

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

4 -

download

0

Transcript of Cyberspace, Y2K: Giant Robots, Asian Punks

University of Massachusetts BostonScholarWorks at UMass Boston

Institute for Asian American Studies Publications Institute for Asian American Studies

3-1-2003

Cyberspace, Y2K: Giant Robots, Asian PunksRachel RubinUniversity of Massachusetts Boston, [email protected]

Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/iaas_pubsPart of the American Popular Culture Commons, Asian American Studies Commons, and the

Race and Ethnicity Commons

This Occasional Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Institute for Asian American Studies at ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. It hasbeen accepted for inclusion in Institute for Asian American Studies Publications by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. Formore information, please contact [email protected].

Recommended CitationRubin, Rachel, "Cyberspace, Y2K: Giant Robots, Asian Punks" (2003). Institute for Asian American Studies Publications. Paper 20.http://scholarworks.umb.edu/iaas_pubs/20

Cyberspace, Y2K:

Giant Robots, Asian Punks

RACHEL RUBIN

An Occasional Paper

INSTITUTE FOR ASIAN AMERICAN STUDIES

March 2003

ABOUT THE INSTITUTE FOR ASIAN AMERICAN STUDIES

The Institute for Asian American Studies was established in 1993 with support from AsianAmerican communities and direction from the state legislature. The Institute bringstogether resources and expertise within both the university and the community to conductcommunity-based research on Asian American issues; to provide resources to the AsianAmerican communities, and to support Asian American students at UMass Boston.

TO ORDER copies of this or any other publication of the Institute, please contact:

Institute for Asian American StudiesUniversity of Massachusetts Boston100 Morrissey BoulevardBoston, MA 02125-3393Tel: (617) 287-5650Fax: (617) 287-5656E-mail: [email protected]: www.iaas.umb.edu

RECENT OCCASIONAL PAPERS PUBLISHED BY THE INSTITUTE FORASIAN AMERICAN STUDIES

Shehong Chen. Reconstructing the Chinese American Experience in Lowell, Massachusetts,1870s–1970s.

Dr. Yuegang Zuo, Hao Chen, and Yiwei Deng. Simultaneous determination of catechins, caffeineand gallic acids in green, Oolong, Black and pu-erh teas using HPLC with a photodiodearray detector.

Nan Zhang Hampton and Vickie Chang. Quality of Life as Defined by Chinese Americans withDisabilities: Implications for Rehabilitation Services.

Maya Shinohara. Here and Now: Contemporary Asian American Artists in New England.

John Wiecha. Differences in Knowledge of Hepatitis B Among Vietnamese, African-American,Hispanic, and White Adolescents in Worcester, Massachusetts.

Paul Watanabe and Carol Hardy-Fanta. Conflict and Convergence: Race, Public Opinion andPolitical Behavior in Massachusetts.

The views contained in this paper are those of the author and not necessarily ofthe Institute for Asian American Studies.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Rachel Rubin is Associate Professor of American Studies at the Universityof Massachusetts Boston. She is author of Jewish Gangsters of ModernLiterature and co-editor of American Popular Music: New Approaches to theTwentieth Century.

On the eve of the 21st century, a groupof young Asian American writersbravely announced—tongue partially

in cheek, in keeping with the aesthetic of sin-cere irony that characterizes the so-calledGeneration X—their recreation of “a mon-ster.” This announcement, posted on theinternet (at www.gidra.net), was drafted by the“editorial recollective” of Gidra, a samizdat(self-published) monthly newsletter launchedthirty years earlier by a group of UCLA stu-dents who wanted a forum where they couldaddress the particular concerns and issues fac-ing Asian Pacific Americans in the VietnamWar era. Writers and editors of a new Gidradeclared in 1999 with a flourish their inten-tion to create a publication that would providea way to “get off our collective asses, lookahead and define the world of tomorrow.”

The circumstances of Gidra’s moment ofrebirth—from the idealism and bravadodemonstrated by its writers, to its relativelylow profile on an internet positively clutteredwith volunteer-produced websites—encapsu-lates a number of important directions inwhich popular culture (especially popularprint culture) had developed since the originalGidra ceased publication after five years. Non-commercial “amateur” publications like thenew Gidra, known as “zines,” are the result ofconsequential international, national, andlocal processes that have radically altered theentertainment industry (as well as the rela-tionship of audiences to that industry). AndAsian American young people (women in par-ticular) have found in zines a remarkably con-genial venue for self-expression and self-defin-ition: scores of zines are devoted to the tal-

Cyberspace Y2K: Giant Robots, Asian Punks

1

Cyberspace Y2K: Giant Robots, Asian Punks1

RACHEL RUBIN

1The following essay has been written as a chapter for a forthcoming book, Immigrants and American Popular Culture[NYU Press]. The book, which is geared toward undergraduate classroom use, uses six case studies over the span of the twenti-eth century to show how immigrants have used popular culture, and how popular culture has used immigrants, to identify,define, and respond to both conflicts and alliances among different groups marked off by race/ethnicity, region, linguistic iden-tity, and so forth. Each chapter will include glossary, maps, and illustrations. “Cyberspace, Y2K” is the book’s final chapter.

ents, cultural needs, and political realities ofAsian Americans. An understanding of theimport of these zines takes us from militaryhistory through the history of its offspring,technological innovation: the Internet hastraveled from its origins inside the warmachine all the way to the sex lives (and otherpersonal spaces) of its users.

Who is Asian American on theInternet?

Amy Ling defines “Asian America” in a poemas “Asian ancestry/American struggle” (Ling1). This couplet captures the duality of experi-ence, the divided heart, that Ling feels charac-terizes the lived lives of Americans with Asianancestry. She continues in this vein to describea “tug in the gut” and “a dream in theheart”—definitions that are wonderfullyevocative, but elusively (and purposefully)non-concrete. Indeed, the feeling of beingAsian American, the varied and internalprocesses by which that name acquires partic-ular meaning, for all its ineffability, is actuallymuch easier to pin down than it is to formu-late an answer that refers to a map. Becausewhile Asia is the world’s largest continent,accounting for more than a third of theworld’s land mass and two-thirds of theworld’s population—including some 140 dif-ferent nationalities—the term “AsianAmerican” has been mostly used to refer onlyto American immigrants from certain Asiannations, but not others. Furthermore, theterm’s application has not been entirely con-sistent, so that “Asian American” can includeone list of ethnic groups in the federal census,another list of ethnic groups in a college’sAsian American Studies curriculum, yetanother list in the political rhetoric of an

activist organization or an elected official, andso on. And when it comes to individualschoosing how to identify themselves, there is asimilar range of usage: some consider them-selves to be Asian American while others donot, even though they or their parents haveimmigrated to the United States from a coun-try on the continent of Asia. Finally, themeaning of the term has changed over time tosuit the rhetorical needs of different times.

Asian American zine publishing reflectsthis complexity. A majority of the zines do usethe word “Asian” or “Asian American”(instead of exclusively using narrower cate-gories such as “Korean American”). But whenmore specific identifiers are added, or when“guest books” (open forums some web cre-ators place on their website, so that peoplewho have “visited” the site can comment) areexamined, it becomes plain that “AsianAmerican” has been embraced as a way to self-identify by Americans of certain backgrounds,while other Americans with Asian ancestrychoose different ways to identify themselves.On the pages (web and print) under consider-ation here, “Asian American” seems to includebackgrounds that are Japanese, Chinese,Korean, Vietnamese, Cambodian, Laotian,Filipina/o, and sometimes South Asian(Indian, Pakistani, Nepalese, Bangladeshi). Incontrast, writing by Arab Americans orArmenian Americans, for example, does notsurface when Asian American search enginesare used to navigate the Internet, and does nottend to use “Asian American” and related lan-guage as descriptors of its content or creators.

In addition to being constituted by a largenumber of nationalities, the term “AsianAmerican” is further complicated by the factthat it can refer to immigrants, their children,their grandchildren, or even subsequent gen-

Rachel Rubin

2

erations. Since the mid-1800s, when Chineseworkers came to build the cross-continentalrailroad, multiple generations of Asian immi-grants have made their way to the UnitedStates; and from the very beginning, Asianimmigration was linked to restriction andracial anxiety. In fact, the notion of control-ling immigration based on ethnic and nationalfactors was born in xenophobic fear ofChinese immigrants: welcomed at first as asource of cheap labor, Asian immigrants weresoon the subject of pressures to stop the influxof workers. The Chinese Exclusion Act,passed in 1882, denied admission to Chineselaborers, and subsequent laws in the next twodecades further extended the act. The ChineseExclusion Act also made explicit a provisionthat had been invoked vaguely since the firstAmerican naturalization law of 1790announced that only “free whites” could natu-ralize: Chinese immigrants were “aliens ineli-gible for citizenship.”

The rhetoric surrounding this legislationidentified the Chinese and Japanese as foreveralien, as “heathens,” as so immutably differentfrom white Americans that they could neverassimilate into American society and adopt“American” ways. It was here that the prece-dent was set that immigration to the UnitedStates was something that could and should beregulated by the government based on groupdefinitions. This approach to controlling whoentered the United States represented a sig-nificant departure from earlier notions ofimmigrant desirability based on individualqualifications. The exclusion of Asian immi-grants from American citizenship culminatedin 1924 with the Quota Act that declared that“no alien ineligible for citizenship” could beadmitted to the United States.

Restrictions against Asian immigrationbegan to loosen somewhat following WorldWar II. The Chinese Exclusion Act wasrepealed, and the 1952 McCarran-Walter Act,while restrictionist in nature, nonetheless gavetoken quotas to all Asian countries. A bit earli-er, in 1945, the War Brides Act allowed wivesand children of members of the Americanarmed services to enter the United States,without being subjected to evaluation by racialor national criteria. These moves are generallyconsidered to represent a progressive wedge inanti-Asian exclusion; however, historianRachel Buff has recently pointed out that suchmeasures actually opened up systematicopportunities for a kind of sexual imperialism,in which United States military men createdpersonal circles of influence, which they thenclaimed as “American” and incorporated intothe United States (personal discussion withauthor about ongoing research). Buff’s quiteground-breaking analysis reveals a powerdynamic within Asian immigration, acted outon a sexual and domestic plane, that AsianAmerican zine creators took up in force a half-century later.

Asian mass immigration did not returnuntil 1965, when the so-called “new Asianimmigration” followed the liberalization ofthe quota system under the Hart-Celler Act.By 1970, Asians were the fastest growinggroup of immigrants to the United States. By1980, nearly half of all immigrants to theUnited States came from Asia.

The “new” immigration would complete-ly change the nature of Asian American com-munities, which previously had been made uplargely of Chinese- and Japanese-Americans.Now, the variety of Asian groups expanded;soon, the fastest-growing Asian ethnic groupsin the United States were those previously not

Cyberspace Y2K: Giant Robots, Asian Punks

3

represented. The “new” Asian immigrantscame from South Korea, the Philippines,Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, India, Pakistan,Bangladesh, Singapore and Malaysia.

The “new immigration” was marked bytwo visible groups of immigrants. First, incontrast to the earlier generations, came whathistorian Reed Ueda has called “a human cap-ital migration” of highly educated profession-als and technical workers (65). These elitesfrom India, the Philippines, China and Koreaworked in health care, technical industries,and managerial positions.

The “new” immigration also broughtwaves of low-skilled and poor immigrantsfrom Asia. One million refugees fromNortheast and Southeast Asia came to theUnited States from the end of World War IIto 1990. Chinese refugees fled to the UnitedStates following World War II. The devasta-tion of the Vietnam War brought refugeesfrom Cambodia, Vietnam and Laos (includingminority subgroups such as the ethnicChinese from Vietnam and the ethnic Hmongfrom Laos and elsewhere). Unlike the Chineserailroad workers of a century earlier, these“new” immigrants were planning to stay per-manently in the United States. They thereforenaturalized in large numbers, brought overextended families, and formed new Asiancommunities as well as transforming and revi-talizing older ones.

The history of Asian immigration givessome sense of how complicated and fraughtthe definition of “Asian American” can be.The idea of a pan-Asian identity, implied bythe term “Asian American,” dates back to thepolitical activism of the 1960s; the term wasfirst used as an organizing tool to facilitatediscussions around issues of racism in theUnited States and issues of global politics in

Asian countries, such as the recognition ofChina, the Vietnam War, the presence ofAmerican military rule in South Korea, and soforth. (Indeed, the original Gidra also wasborn out of anti-Vietnam war movement, andstressed the movement’s particular importancefor Asian Americans; articles such “GIs andAsian Women” and “The Nature of GIRacism,” for instance, addressed the implica-tions for race relations in the United States ofthe United States Army’s tactic of dehumaniz-ing Asians—particularly Asian women—as away to create psychological conditions thatwould allow the killing of Vietnamese.)

The geopolitics of Asian immigration tothe United States is, therefore, responsible forthe very notion that there is such a thing as“Asian American” identity. In the variouscountries of origin, an “Asian” identity wouldnot be primary; people might identify as“Korean” or “Chinese” or “Indian”—or, evenmore likely, according to even more specificcategories of religion, caste, region, and soforth. While there are certainly cultural aswell as environmental similarities among vari-ous Asian nations, lumping together thedozens of ethnicities of the huge continent canobscure much more than it explains. But aspart of the compound “Asian American,”“Asian” gains relevance and specificity as asocial or cultural identifier. In large part, thisis because of the way that “mainstream”American vision has categorized Asians fromwithout, and speaks to the status of “other”conferred upon them; after all, “Asian” stillhas not fully replaced the word “Oriental,”formerly the general term and rejected duringthe 1960s and 1970s as reflecting a colonialistmentality. (“Oriental” means “Eastern” orhaving to do with the East. Since directionsare relative, the word “Oriental” betrays

Rachel Rubin

4

Eurocentrism; in other words, Asia is east ofwhat?) In short, while there is a big differ-ence—not to mention many miles—between,say, a Buddhist from Tibet and a JapaneseHawaiian, or between someone from theIndonesian islands and someone fromKazakhstan, that distance has tended to becollapsed in the public imagination once theseimmigrants arrive in the United States. (Thisconflation has at times occurred against theefforts of Asian immigrants themselves, asduring World War II, when some Chineseand Koreans wore buttons claiming “I’mChinese, not Japanese,” and still faced abuseor ostracization.)

But immigrants from the various Asiancountries also have had their own reasons forembracing an Asian American identity. Astrategic essentialism can facilitate the culturalempowerment that permits Americans like theeditors of Gidra (in both incarnations) tospeak of an “Asian” experience in the firstplace—not to mention building the solidaritythat could allow for Asian representation inelected bodies of government. Thus, whileindividual Asian countries and cultures areoften singled out in Asian American zine cul-ture (Bamboo Girl targets the Filipina/o com-munity, for instance, while Half Korean speaksto Korean intermarriage), more often zinewriters bolster the symbolic ethnicity of“Asian American”—symbolic, because of itsrhetorical and deliberate nature, but nonethe-less possessed of real-world implications.Singer/songwriter Chris Iijima explains thisdynamic:

We were able to construct an APA [AsianPacific American] identity preciselybecause our shared experience as Asiansin America—always cast as foreigners and

marginalized as outsiders—allowed us tobridge ethnic lines and allowed a plat-form and commonality engage andunderstand other people and their strug-gles... You ask whether there is an“authentic” Asian American sensibility.Asian American identity was originallyconceived to allow one to “identify” withthe experiences and struggles of othersubordinated people—not just with one’sown background. (Ling 320-321)

Iijima’s words emphasize that Asian Americanidentity is a deliberate and motivated thing:experiential rather than biological, groundedin the present as much as or more than in thepast. For Asian American cyberzine writers,whose numbers include immigrants, the chil-dren of immigrants, or the grandchildren ofimmigrants, the constructedness of “AsianAmerican,” coupled with the definitively de-centered nature of virtual reality, creates awide-open, compelling cultural opportunity.

Where did cyberculture comefrom?

The technological innovation upon whichcyberculture is built was, as is often the casewith new technologies, an outgrowth of mili-tary research. In other words, the wars andinternational conflicts that were responsiblefor the mass migration of Asians to the UnitedStates after 1965 also provided the impetus forthe research that led to the creation of theInternet. The germinal idea of the Internetwas first conceived some thirty years ago bythe RAND Corporation. RAND, the UnitedStates’s foremost Cold War think-tank, wastrying to answer a particular strategic ques-tion: How could United States authoritiescommunicate with each other following a

Cyberspace Y2K: Giant Robots, Asian Punks

5

nuclear war? The problem was that any net-work would be shattered by a nuclear bomb,and furthermore, the network’s central com-mand station would be an obvious target forattack. So RAND’s scientists came up with anetwork that was assumed to be vulnerable atall times—but would work anyway, since therewould be no central station, and no singlepath of communication. If part of the networkshould be inoperable, the information wouldsimply travel via an alternative route.

In 1968, the Pentagon’s AdvanceResearch Projects Agency funded a large,ambitious project to explore the concept of adecentralized network. High-speed computerswere to be the stations in this network (called“nodes”); the first station was installed at theUniversity of California-Los Angeles in 1969.In the next few years, more stations wereadded. These stations were able to transferlarge amounts of data very quickly, and couldbe programmed remotely from the other sta-tions. Although this feature was a boon forresearchers, it did not take long for it tobecome clear that the most of the computertime on the network was being used not forresearch or collaboration among scientists, butfor personal messages.

The computer mailing list was inventedearly on, allowing the same message to be sentto large numbers of network subscribers.Thus, almost from its inception, creation of amass audience was key to the Internet’s appealto huge numbers of users. This was an impor-tant step toward the proliferation of cyberzinewriting, for it contains the seeds of the tech-nology that provides e-zine writers with analmost unlimited readership.

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, moreand more social groups acquired powerfulcomputers. It became increasingly easy to

connect these computers to the growing net-work, turning them into new “nodes” in thesystem that would come to be called theInternet. The software belonged to the publicdomain (no one owned the rights and it waswidely available), and the leadership was fullydecentralized as originally planned by RAND.Connecting cost little or nothing, since eachstation was independently maintained.Quickly, anarchically, and unevenly, theInternet network mushroomed, and by the1990s, Internet connection was a necessity formany businesses, “computer literacy” becamea requirement for college education, and “per-sonal computers” found their way into moreand more homes, in the United States andelsewhere.

The decade of the 1990s saw the fastestgrowth of the Internet, which was expandingat a rate of twenty percent per month. Movingoutward from its original base in military andscientific arenas, the Internet established itselfin educational institutions of all levels (includ-ing preschool), libraries, businesses of allkinds, and, of course, personal residences.Since any computer with enough memoryneeds only a modem and phone line to beadded to the network, the Internet continuesto spread more and more rapidly, on anincreasingly global scale.

The chaotic nature of the Internet’sspread has gifted it with a uniquely democraticnature. By comparing the Internet to theEnglish language, Internet historian BruceSterling stresses the very basic cultural signifi-cance of the Internet’s easy access:

The Internet’s “anarchy” may seemstrange or even unnatural, but it makes acertain deep and basic sense. It’s ratherlike the “anarchy” of the English lan-

Rachel Rubin

6

guage. Nobody rents English, and nobodyowns English. As an English-speakingperson, it’s up to you to learn how tospeak English properly, and make whatev-er use you please of it (though the govern-ment previous certain subsidies to helpyou learn to read and write a bit).Otherwise, everybody just sort to pitchesin, and somehow the thing evolves on itsown, and somehow turns out workable.And interesting. Fascinating, even.Though lots of people earn their livingfrom using and exploiting and teachingEnglish, “English” as an institution ispublic property, a public good. WouldEnglish be improved if “The EnglishLanguage, Inc.” had a board of directorsand a chief executive officer, or aPresident and a Congress? There’d prob-ably be a lot fewer new words in English,and a lot fewer new ideas. (Sterling 4)

Indeed, it is not uncommon for zine writers toclaim that they began their zine because theycould not find publications that suited theirown cultural needs. According to SabrinaMargarita of Bamboo Girl, now 31, shelaunched her zine several years ago for thisreason:

It started in 1995, and I pretty muchstarted launching it because I could notfind anything reading material-wise that Icould relate to. Because most of the itemsthat dealt with feminism or queer identityweren’t really geared toward women ofcolor. So I had to search for items thatdealt with women of color. However,when I did, I did not find anything thatwas very supportive of the feminist or

queer communities. In particular, I waslooking for Asian American publications,and most of these only addressed upward-ly-mobile professionals. Which totallydid not include me. (Margarita interview)

Because of her needs as a reader, SabrinaMargarita started handing out copies of herzine—which is paper, with an informationalwebsite that serves to publicize it—to herfriends, making up about a hundred photo-copies of each issue. A few years later, in 2001,she has a circulation of 3,000, works withabout five or six contributors in each issue,and sells the journals by mail but also in somebookstores. As Sabrina Margarita’s experiencewith Bamboo Girl shows, in Internet publish-ing, the lines become thoroughly blurredbetween consumption (or audience), and pro-duction (or writer)—with the democraticaccess to the Net acting as conduit from oneto the other. Another example can be drawnfrom Kristina Wong’s e-zine Big Bad ChineseMama. The site features parodic biographiesand photos of fake mail order brides. At first,the 23-year-old Wong used her own photo-graph and ones she collected from her friends.Now, she says, she receives and posts picturesmailed to her from women around the coun-try and beyond (Wong interview).

That the Internet is, as Sterling puts it,“headless, anarchic, million-limbed” (Sterling5) also has concrete and particular influenceon what webzines look like. There are mil-lions of public files that can be accessed anddownloaded (transferred to the computer oneis using) easily and in a matter of moments. Inother words, zine writers can look around theInternet and find a seemingly endless supplyof elements they can add to their zines: pho-

Cyberspace Y2K: Giant Robots, Asian Punks

7

tographs, artwork, language, music, and morecan be included with a simple cut-and-paste.And zine writers with just a little more hard-ware and a few more computer skills can easilyscan into the computer images or sounds oftheir choosing (which other people, after visit-ing the site, can in turn download to their owncomputers).

A result of this cut-and-paste smorgas-bord is that many cyberzines take their shapeand their energy from the contrasts and juxta-positions of the collage. The vast world of theInternet has encouraged zinesters to developthe style of pastiche, already important inprint zines. But using the Internet, the collagecan include many more forms (animation,music, etc.). Cyberzines can also make theirpastiche multi-layered through the use ofhypertexting, by which a highlighted word orimage, “clicked” with a computer mouse,jumps the reader to another screen from with-in the first one. Readers can jump back andforth among hypertexted pages, potentiallycreating endless combinations of pages,images, and sounds. In addition, highlightedlinks can also take readers to other users’ sites,which might be similar or relevant to the orig-inal zine (as in Mimi Nguyen’s list of feministand Asian American web sites, linked to herzine Exoticize This), or might simply be a sitethe original web writer likes (as in KristinaWong’s list of other sites that happen to tickleher fancy, linked to her site Big Bad ChineseMama).

As an artistic strategy, pastiche finds itspower in juxtaposition and constant re-con-textualization. Words, sounds, and images cir-culate hypothetically endlessly, acquiring newlayers of meaning, as they carry the associa-tions and meanings from previous usages withthem into their new contexts. One of the rich-

est expressions of this cut-and-past is the artof sampling in hip hop music, wherein musi-cal, spoken or other sounds previously record-ed are included within the rap song. Theresult is a wholly new frame of reference forthe sample—and also an affirmation of sharedcultural experience, because in order to under-stand the new song fully, a listener mustremember and recognize the sample.

Because the artistic mandates of pasticheinspire its practitioners to seek new elementsto borrow or include in all sorts of places, pas-tiche also expresses and enacts the web ofprocesses that constitute globalization. TheInternet has connected up different parts ofthe world in a powerful new way: images,words, etc. can flow across borders in moredirections and faster than ever before. (Amongother things, this makes policing speech that isunprotected in the United States, such as childpornography, much harder to do, as Internetusers can simply visit web sites generated inother countries.) The process of importingand exporting cultural bits from all around theglobe can lead to a web zine which containscontent that originated almost anywhere.

The aesthetics of pastiche, in which origi-nality and newness are not primary values, butrecirculation, reproduction and reinterpreta-tion are, is a hallmark of an economic andartistic system called postmodernism.Economically speaking, “postmodern” refersto a system that does not depend chiefly uponindustry and production (as did the “modern”economy) but rather on information technolo-gies and service-based jobs: work in officesrather than factories, marketing of experiencesrather than goods, and relying upon the rapidtransfer of information made possible by faxmachines, cellular phones, photocopiers,overnight mail services, and above all, the

Rachel Rubin

8

Internet. When used in reference to culture,“postmodern” generally refers to a constella-tion of aesthetic concerns and practices,including a lack of certainty about meaning(privileging the reader’s ability to decodemeaning based on his or her interest andexperience); an elevation of the popular; and acontinuous re-contextualization of pre-exist-ing texts or fragments of texts. Thus, theInternet—with its rapid processing of infor-mation—is both product of, and medium for,the postmodern sensibility—-which, in turn,speaks for and to an increasingly global econ-omy.

Another hallmark of the postmodern sen-sibility is a fascination with the body aschangeable and socially constructed. This fas-cination has manifested itself in a variety ofways, including a ferocious surge in popularityof plastic surgery, body piercing, tattooing,and the like, especially on the part of youngpeople who grew up in the postmodern era.(In the case of body piercing and tattooing,the popularity points not only to a notion ofthe body as shapeable, but also to the processof globalized culture, as these practices havebeen widely practiced for a long time in other,“developing” countries.) In this regard, theInternet inserts a fascinating twist: what canwe say about the idea of the body (as a placewhere cultural texts may be inscribed) in a cir-cumstance where it is essentially removed?How do bodies function at all, and what dothey mean, in cyberspace?

In the world of the Internet, ethnic pub-lishing, such as Asian American e-zines, pre-sents a fascinating contradiction. In the firstplace, bodies are a major way in which ethnic-ity or race get written and read, and therefore,a certain amount of exploration of what makesan Asian American body is unavoidable.

Zinester Mimi Nguyen, in her online zineslander, meditates at some length about therange of ways her Asian body can “mean”depending upon what sort of hairstyle she iswearing:

All through high school I had “natural”long black hair. A white man approachedme in the park one day, told me he musthave been an “Oriental” man in a formerlife, because he loves the food, the cul-ture, and the women. At the mall a blackMarine looked me up and down andinformed me he had just returned fromthe Philippines, and could he have myphone number?... I cut off all my hair anddamaged it with fucked-up chemicalsbecause I was sick of the orientalist gazebeing directed at/on me.(http://www.worsethanqueer.com/slander/hair.html)

Nguyen continues to explore the complexitiesof hair in a racialized setting: can bleachingblack hair imply self-hatred? What does itmean to dye your hair green? Does hairstylehave anything to do with politics?

But despite the urgency of Nguyen’sdescriptions of how her body has looked atvarious times, and what physical changes shehas made to her appearance, there is no realcorporality to the medium in which she regis-ters her complaint. One thing that makes theInternet possible is that place has no literalmeaning, and that neither users nor informa-tion need be located in a fixed position.Furthermore, it is an Internet tradition ofsorts to use that lack of physicality to create,and re-create, various identities according towhim, so that “a central utopian discoursearound computer technology is the potential

Cyberspace Y2K: Giant Robots, Asian Punks

9

offered by computers for humans to escapethe body” (Lupton 479). In chat rooms, forinstance, men regularly log on as women orwomen as men, users invent entire personasfor themselves including made-up physicaldescriptions, and people have “virtual sex”:

Role-playing sites on the Internet…offertheir participants programming featuressuch as the ability to physically ‘set’ one’sgender, race and physical appearance,through which they can, indeed arerequired to, project a version of the selfwhich is inherently theatrical. Since the‘real’ identities of the interlocutors…areunverifiable…it can be said that everyonewho participates is ‘passing,’ as it isimpossible to tell if a character’s descrip-tion matches a player’s physical charac-teristics. (Nakamura 712)

For some Asian American zinesters, bod-ies are an obsession because sex and sexualityhave been so central in the process of margin-alizing and commodifying Asian Americans.On the Internet, pornographic images aboundthat hawk the stereotype of the physicallysmall, submissive Asian woman, or the emas-culated Asian man. Several zinesters expressedto me a kind of annoyed weariness at still hav-ing to harp on the “I’m not a geisha” protest,while web sites like the one maintained by theAsian porn star Annabel Chong—who causeda stir by filming “the biggest gang-bang in his-tory,” in which she had sex with 251 men inten hours—strive to emphasize agency andhumor in the sexualized Asian body.Nonetheless, the zinesters admit, thesenotions remain ubiquitous. Sabrina Margaritahas received drawings sent without apparentmalice to Bamboo Girl of Asian men having sex

with white straight men; Holly Tse, editor ofAsiaZine, points out that even a purportedlyAsian-oriented web site, Click2Asia.com, reg-isters under its umbrella literally hundreds ofporn-swapping and sex-oriented clubs thatadvertise young Asian women (Margaritainterview and Tse interview). To further com-plicate matters, according to cultural criticLisa Nakamura, when white people createInternet personas that are non-white, Asianpersonae are by far the most common—andthe way these personae are drawn tends toreiterate and reinforce a handful of very rec-ognizable racial and ethnic stereotypes, suchas the submissive woman or de-sexed manmentioned above (Nakamura 714).

In this light, the most daring andoppositional aspect of Kristina Wong’s BigBad Chinese Mama might be the fact that shepublishes photographs of Asian women—alllooking ugly on purpose (see illustration A).This completely flies in the face of what Asianwomen are “supposed” to do with theirbodies—or what any women are supposed todo with their bodies, as the multi-milliondollar cosmetics industry attests. The captionsaccompanying the photos of young womenmaking absurd faces, picking their noises,sitting on the toilet, or sticking out theirtongues refer to the cultural expectations theyare working to thwart: “Not quite a lotusblossom, but the next best thing,” one reads.Another, cleverly, offers a haiku: “I know mypurpose/my life is but to serve ME/get yourown damn beer (http://www.bigbadchinesemama.com/meredith.html).

Where did zines come from?

The world of zines is incredibly varied, so thatmost definitions will tend to be inadequate.Until fairly recently, zines were part of a cul-

Cyberspace Y2K: Giant Robots, Asian Punks

11

Rachel Rubin

12

tural underground; self-produced and haphaz-ardly distributed, they were driven by passionrather than profit, and, although their focusescould literally be on any subject, they general-ly shared a contempt for big-business publish-ing, a celebration of the quirky and the con-fessional, and a respect for the open expres-sion of unpopular tastes and ideas.

At the present, zines can be divided intotwo basic categories: print zines andcyberzines (also called e-zines). By now, paperzines range from handwritten sheets, stapled,photocopied, and mailed to friends, to elabo-rately produced publications created by edi-tors with skills in desktop publishing and soldin alternative bookstores and even some bigchain stores (such as Tower Records).Cyberzines run a similar gamut: some of thedesigns are visually spectacular, and make useof video clips, digital photographs, links toother sites, and so forth, while others areessentially text-only rants. While there arestill hundreds of paper zines being published,cyberzines are proliferating even faster,because they are even cheaper to produce,there is no need to worry about distribution atall, and the potential audience is practicallylimitless.

The name “zine” is not directly descend-ed from the more common “magazine,” asmight be supposed. Instead, the antecedentfor “zine” is “fanzine,” a term that originatedin the 1930s to describe cheap periodicals thatpublished science fiction stories. The growthof the popularity of science fiction coincided

with the surge in popularity of the mimeo-graph machine, with the result that the 1930s,1940s and 1950s saw a boom in self-publish-ing of these fanzines, which began to containnot only science fiction but also comics, fanta-sy stories, mysteries, and other popular formsof writing. These fanzines left an indeliblemark on the popular cultural landscape. Forinstance, in the third issue of Science Fiction,published in 1932 by Jerome Siegel and JoeSchuster, a character named Superman wasintroduced.

The tradition of self-publishing was fur-ther developed during the 1960s, whenactivists in a number of grass-roots organiza-tions began publishing their own newslettersand alternative newspapers across the UnitedStates. In addition to Gidra, some of the moreprominent alternative papers of this eraincluded the Berkeley Barb, the Los Angeles FreePress, and the Detroit’s Fifth Estate. The era ofthe 1960s also added underground comix(most famously represented by cartoonist R.Crumb) and music fanzines to the mix.2

The late 1970s and 1980s saw the birth ofpunk subculture as a reaction against theincorporation of rock and roll music into bigbusiness, at the expense of its rebellious natureand musical frisson. As Greil Marcus put it,with the introduction of punk,

Very quickly, pop music changed—and sodid public discourse. A NIGHT OFTREASON, promised a poster for a con-cert by the Clash in London in 1976, and

2 The word “comix” (as opposed to the more common “comics”) generally refers to a body of work associated with the1960s counterculture and comprising the “scene” of underground/independent art, while “comics” refers mostly to newspaperstrips and comic books produced by the major publishing companies such as Marvel and D.C. It must be noted, though, thatthese categories are extremely permeable and at this point the two spelling variants indicate a difference in emphasis, ratherthan discrete groupings.

Cyberspace Y2K: Giant Robots, Asian Punks

13

that might have summed it up: a newmusic, called “punk” for lack of anythingbetter, as treason against superstar musicyou were supposed to love but which youcould view only from a distance; againstthe future society had planned for you;against your own impulse to say yes, tobuy whatever others had put on the mar-ket, never wondering why what you reallywanted was not on sale at all. (Marcus 2)

Hundreds of publications such as Punk took aphilosophical and aesthetic stand against thebland seamlessness of corporate popular cul-ture by developing a publishing style that fitthe punk credo of D.I.Y. (or Do It Yourself).In this light, it is important to emphasize thatthe unpolished, non-professional style of zinesis a positive statement, rather than simply acondition of not being able to do a “better”job. The style of D.I.Y. (and its successor,“indie” or independent) continues to repre-sent a multi-layered critique of the popularculture industry: its motivations, its methods,and its material.

This outspokenly oppositional stance, inthe words of R. Seth Friedman (the first com-piler and reviewer of zine writing), gavefanzines in the 1980s “the heart of a musicfanzine but the character of an undergroundcomic” (Friedman 12). The lessons of punk,coupled with the proliferation during that eraof cheap copy-shop chains such as Kinko’s andthe introduction of personal computers andprinters into a mass number of homes andworkplaces, led thousands of people to createtheir own idiosyncratic zines. And the distrib-ution of the zines also dovetailed with the phi-

losophy of D.I.Y.: authors generally handedthem out, or mailed them out themselves afterreceiving a request and money to coverpostage. Even more notably, zine writers oftenoffered a trade instead of a price tag: you sendme a copy of your zine, and I’ll send you acopy of mine. The result is a kind of culturalswap-meet that undeniably has its utopianqualities in its ability to create a community ofzine producers and consumers without beingruled by the marketplace.

Of course, producing a D.I.Y. zinerequires a large amount to commitment onthe part of the authors. Holly Tse, who isthirty years old and works full-time, spendsfrom forty to sixty hours producing each issueof AsiaZine, which comes out every threemonths (Tse interview). AsiaZine is an extra-ordinarily attractive and elaborate zine, andsticks to its quarterly production schedulewith unusual success, but Tse’s dedication isnot unusual.3 Sabrina Margarita of BambooGirl, for instance, not only makes time to pub-lish her zine but also maintains an e-mailmailing list for “updates” that she sends outbetween issues.

Why Asian Americans? Why zines?

“Zines have been very good for youngAsians,” declares a female college student whohelped to organize a zine conference at herMassachusetts college. Lorial Crowder ofBagong Pinay, an e-zine with the stated goal ofproducing a “positive representation forFilipinas on the Internet,” agrees: “It [the zinemovement] been really important, a majorvoice for us” (conversations with the author,

3 In 2002, AsiaZine’s production schedule was reduced to three issues per year.

Rachel Rubin

14

25 July 2001 and October 17 2001). Given thepower and frequency of such personal testi-monials, it is worth considering concretelywhat it is, exactly, about the form that hasproven to be such a congenial media ofexpression for Asian American youth. Theaesthetic mandates of zine publishing haveturned out to serve some particular needs ofyoung Asian Americans.

Asian American zines—paper and elec-tronic—flowered at a time when Asian culturereached the American mainstream in a bigway. At the turn of the twenty-first century,Hong Kong action movie hero Jackie Chanbecame an American star with his crossoverhit Rumble in the Bronx (1995), which grossed$28 million during its first release. Americansspent millions of dollars on products fromlunchboxes to trading cards to t-shirts toutingfigures from Japanese animation (most notablyPokemon). Karaoke became a popular pastimefor white Americans across the United Statesand grew into a multi-billion dollar industry.“Japanimation” on television and at themovies broke from its cult status and gainedwidespread appeal. Girls of all ages begansporting clothing and makeup emblazonedwith the resoundingly cute cartoon portrait ofthe Japanese project trademark “Hello Kitty.”

It is no coincidence that zine production,with its anti-professional stance and its edgyaesthetic, would snowball at precisely this cul-tural moment of crossover and cooptation, orthat its writers and webmasters would voice anearly continuous appeal to “keep it real” byresisting commercial polish and by definingand describing Asian culture from within.Gidra, for instance, refers directly in its inau-gural issue to the plethora of “slick, full-color,high-fructose eye syrup publications” aboutAsian culture that fill the newsstands.

(http://www.gidra.net/Spring_99/bring_it_back.hmtl.) Similarly, the two young writersof “Hi-Yaa!”, June and Phung, refer to theplethora of elaborate websites that exoticizeAsian culture as a motivation for starting theirown zine (http://www.hi-yaa.com/index2.html). The relatively democratic nature ofzine publishing (see above) has facilitated toan unprecedented degree for this kind of self-expression.

An important touchstone in AsianAmerican zine publishing reveals unusuallyclearly this tension between commercial andD.I.Y., between mainstream and marginal.This is the case of Giant Robot, launched in1994 by Martin Wong and David Nakamura.GR, a quarterly zine of Asian American popculture that comes out of Los Angeles, beganas a photocopied affair with a run of 450copies. GR quickly came to exemplify whatwould be known as “GenerAsian X,” growingso rapidly that the editors claimed a circula-tion of 12,000 by the ninth issue. Over theyears of its production, GR has taken on awide range of subjects, including Asian squat-ters in New York City, Margaret Cho’s stand-up comedy, the Asian American PowerMovement of the 1960s and 1970s, Asian hair-cuts, Asian junk food, and a skateboarding tripby the editors through an abandoned WorldWar II internment camp.

With Giant Robot firmly established as acritical and commercial success, a fascinatingkind of self-backlash occurred. Issue 17 cameout on time in 1999. A photograph of comicMargaret Cho, the first Asian-American starof a TV sitcom (All-American Girl), graces thecover, along with a bar code for scanning bylarge retailers. The perforated subscriptionblank offers a credit card payment option.Advertisers tout products ranging from books,

Cyberspace Y2K: Giant Robots, Asian Punks

15

videos and CDs to toys and skateboard gear.In many important ways, the zine maintainsits in-your-face stance: headlines scream “milkfarts,” “sluts and bolts,” and “eat bugs.” Evenso, this is a journal with high production val-ues, a big budget, and wide distribution.

But Wong and Nakamura, it seems,missed something about the indie aesthetic towhich self-produced zines generally hew.They created a second zine, which they called“Robot Power,” a raggedy spin-off of GiantRobot billed as “Issue 17.5.” (This inauguralissue was followed by subsequent releases,which are released after each issue of GiantRobot). Robot Power looks very different fromits parent: no glossy paper, no color graphics,staples instead of glued binding, and much lessadvertising (especially by bigger companies).In short, the homemade quality of zines isclearly part of the point, and Wong andNakamura’s ambivalence about leaving itbehind speaks to a central dynamic betweenthe commercial and the “authentic” in theelectronic era.

According to R. Seth Friedman of theFactsheet Five, the first popular review of zines,the centrality of this dynamic has made thesinger Kurt Cobain an icon of zine publishing.Sub Pop, Cobain’s record label with Nirvana,had started as a music fanzine calledSubterranean Pop. When Nirvana achievednational success, zine culture also grew inprominence. And zine writers elevated Cobainas a figure from the underground music scenewho finally got recognition—but who contin-ued to critique the star system and the huge-profit music industry into which he hadentered (Friedman 102).

Zines, then, have proved to be an espe-cially congenial forum for the cultural needsof Asian American youth because of the waythey allow young people to “talk back” to acultural industry turning huge profits by sell-ing things Asian. It has also been importantthat zines, and the punk aesthetic generally,tend to be organized in gleeful opposition todecorum and propriety. In other words, zinepublishing has “worked” so well for Asian

Illustration B

Angry Little Asian Girl and friends.

Rachel Rubin

16

Illustration C

The secret life of Hello Kitty.

American youth because it is uniquely success-ful at providing a means of expression thatflies directly in the face of the “polite Asian”stereotype. For young people chafing underthe label of “model minority,” the slaphappyworld of zine culture is a significant opportu-nity for opposition. An example is “Dead FishOnline Magazine: An Asian Online Zine.” Inaddition to the disgusting title (and the illus-tration that accompanies it), the zine has abanner across the bottom of its home pagethat declares, “Warning: we are not experts onanything, so complain to someone who cares”(www.deadfish.com).

Similarly, Lela Lee’s character AngryLittle Asian Girl (first presented online in1998) refuses in various comic strip adventuresto be anyone’s nice girl—and found a surpris-ing large and loyal audience along the way(see illustration B). This intentional refusal tobe polite can be quite emphatic, as illustratedby the many, many references to shit, farts,and comic sex that crop up in the zines. Muchartwork by Kristina Wong, of Big Bad ChineseMama, for instance, pivots on the rejection of

being a silent “good girl.” Wong redraws theJapanese cartoon character “Hello Kitty,” anextremely cute kitten drawn with no mouthwho appears on a huge number of products,with a caption reading “What Hello Kittywould say if she had a mouth.” Word balloonsshow the dainty feline saying, “Who’s up for athreesome?” or “Who are you calling apussy?” (see illustration C).

As these young Asian Americans have it,the notion of “model minority” is both limit-ing and condescending in the way it seeks tocongratulate Asians for knowing their placeand buying into the American dream. Byfocusing on well-off young people who makeit to Ivy League colleges, the “model minori-ty” myth leaves out or penalizes Asian immi-grants who are struggling against great chal-lenges—language barriers, poverty, racism—and whose future is not assured. A new stereo-type emerges of a driven, studious, hyper-competent and above all, conventionally suc-cessful Asian American, one that encouragesanti-Asian backlash as well as misrepresentingthe diversity and complexity of Asian America.

Cyberspace Y2K: Giant Robots, Asian Punks

17

The “model minority” myth also praises(if backhandedly) Asian Americans at theexpense of other so-called minority groups,most notably African Americans, therebymaking Asian American social mobility com-plicit in racism—a bitter stance indeed for themany zine writers who clearly identify them-selves with African American cultural prac-tices, especially hip hop culture. This dynamichas led Mia Tuan, in her book on the Asianethnic experience, to frame the fate of Asiansin the United States as stretched between twopoles: “forever foreigners or honorarywhites.”4

Thus, although not all zines are explicitlypolitical (as are Gidra or Asian AmericanRevolutionary Movement Ezine, among others),the zines overwhelmingly share an emphasison what I’ll call attitude, revealed throughdirect and belligerent addresses to the reader,use of slang and sarcasm, pugilistic graphics(frequently featuring a person punching orkicking directly at the reader’s face), and soforth. This quality of “attitude” is hard todefine or pin down, but it is nonetheless cen-tral to the rich world of Asian American zinewriting. “Attitude” is the means by whichAsian American zine writers give their publi-cations what Michael Denning would call“accent”—a symbolic and rhetorical device bywhich they mark themselves as immigrants,children of immigrants, or grandchildren ofimmigrants struggling toward a nuancedunderstanding of American identity (Denning3-5). “Attitude” includes a range of tactics bywhich zine writers loosen themselves frominadequate categories such as conformist“American” or traditional “Asian.”

The Asian-American youth “attitude” istransmitted across a variety of styles or formsof zine production. Gidra makes use of wordsand expressions associated with hip hop cul-ture, quoting rapper KRS-ONE and announc-ing, “Gidra’s back. Spread the word, yo”(http://www.gidra.net/Spring_99/bring_it_back.html). AsiaZine uses sly wordplay; its slogan“Get oriented!” is at least a triple pun, whicheach meaning mocking an aspect of the(nonetheless) urgent construction of AsianAmerican identity, which is an organizingprinciple for the zine (see illustration D). Thetitle of Hi-Yaa! also reminds us of the multi-plicity of identity: the authors expand “Hi-Yaa” into “Hi, Young Asian Americans!” whilethe name simultaneously reiterates the stereo-typical sound made in kung fu movies—or bysmall children playing at kung fu (see illustra-tion E).

Many zines by and about Asian Americanwomen use zine “attitude” to confront domi-nant images in popular culture of Asianwomen: the submissive geisha-girl, the China-doll, the Indian princess. Zinester MimiNguyen writes, “Now I will be what they leastexpect. I will be scary. I will be other than thestereotype of the model minority, the passiveAsian female” (http://www.worsethanqueer.com/slander/hair.html). Nguyen sets out toconfront notions of what an Asian Americanwoman should be, and makes clear in variousmission statements that this is her intent. “Goahead,” dares a self-portrait on the website, inpugilistic pose. “Exoticize my fist” (see illus-tration F). Likewise, Lela Lee’s Angry LittleAsian Girl turns cuteness inside out—and inthe process, has attracted a lot of attention,

4 This binary, posed as a question, forms the title of Tuan’s book.

Rachel Rubin

18

Angry Asian Asian in Denial Banana/Coconut Asian FOBPolitically CorrectAsian

Very angry abouthow Asians areviewed by Westernsociety. Has big chipon shoulder andgoes on and onabout "Asian pride"and "elevating ourrace".

Usually grew up in apredominantly Whiteneighbourhood.Pretends to beWhite. Does notacknowledge thatthey are Asian.

Yellow/brown on theoutside, white onthe inside. Generallyraised in a Westernsociety, but hasexperienced thequirks of beingraised Asian. Doesnot deny heritage.

Fresh Off the Boat.Usually spentformative years inan Asian society.Holds onto Asianvalues andattitudes. Limitedinfluence byWestern at titudes(except forshopping).

General ly raised in aWestern society andas such, is highlyinfluenced byWestern ideals ofpolitical correctness.Quick to judgeothers about judgingothers based on skincolour.

Personal Mantra:"If you don't seethings my way, youare anti-Asian, youf**king a**hole!"

Personal Mantra:"I am White. I amWhite. I am White."

Personal Mantra:"I used to wish Iwas White, but I'mmature and grownup now. I have thebest of both worlds."

Personal Mantra:"Everything Asian isfar superior toeverythingWestern."

Personal Mantra:"I do not makedistinct ionsregarding race. Thisis a bad thing todo."

Buzzwords/Phrases: "Asianpride", "f**k you","you dumb sh*t",(any grammatical lyincorrect expletives)

Buzzwords/Phrases: "If theylive here, theyshould speak thelanguage." "Myfriends think I'mmore White thanthey are."

Buzzwords/Phrases: "It 's okwhen I make (insertnationality here)jokes because I'm(insert nationalityhere)."

Buzzwords/Phrases: "Are you(insert national ityhere)?" "How comeyou don't speak(insert Asianlanguage here)?"

Buzzwords/Phrases: "eracism","we all bleed thesame colour", "let 'sall get along","perpetuatingstereotypes"

SocialInteractions:Hangs out only withother Asians in a biggroup. Has aconfrontationalattitude and looksfor racism in everygesture.

SocialInteractions: Willonly hang out withWhite people.Avoids other Asianslike the plague. Maytalk to other Asiansin Denial, but willnever be caughtdead in a group ofAsians.

SocialInteractions: Hasfriends who areAsian and friendswho are not.However, is alwaysaware of the racialdynamics of thegroup.

SocialInteractions:Friends are all Asian.Has a "stick-together" mentality.Will hang out withsomeone solelybecause they'reAsian even if theydon't really likethem

SocialInteractions:Hangs out mostlywith other PoliticallyCorrect Asians. Hasa few token Whitefriends. Makes apoint to not noticerace.

Thoughts on LucyLiu: "She's a sell-out."

Thoughts on LucyLiu: "I think shesucks. I preferCalista Flockheart."

Thoughts on LucyLiu: "I heard she's abitch." OR "Way togo! Another Asian inmainstream media."

Thoughts on LucyLiu: "I secretlyadmire her, butpublicly look downon her because sheis not truly Asian."

Thoughts on LucyLiu: "Sheperpetuates thedragon ladystereotype."

Thoughts onASIA'ZINE: "Your'zine sucks. Youdon't know anythingabout Asian pride."

Thoughts onASIA'ZINE: None,as an Asian in Denialwould never readthis 'zine.

Thoughts onASIA'ZINE: "Ilaughed my ass off."

Thoughts onASIA'ZINE: "This isnot true."

Thoughts onASIA'ZINE: "Peopleare ridiculedeveryday because ofthei r skin color orethic back ground.This is shit, and youshouldn't publish it."(Actual quote,spell ing errors andall)

Illustration D

Multiplicity of identity as parody.

Cyberspace Y2K: Giant Robots, Asian Punks

19

Illustration E

In your face (literally) attitude.

Illustration F

“I will be what they fear most,” says zinester Mimi Nguyen.

just try it. go ahead.

exoticize my fist.

inspiring Lee to create more defiant charac-ters (other Angry Little Girls). And some-times, when zine writers begin to take theirthoughts to the public, the confrontation hap-pens automatically, as when Holly Tse ofAsiaZine’s found that her first choice of titlesfor her zine, InvAsian, was taken already—bya porn site. (Tellingly, if one performs anInternet search with the keywords “Asian +women,” the results will include zines likeWong’s and Nguyen’s—and an enormousnumber of pornography sites.)5

Conclusion: Where will zines go?

The many and varied print and cyber-zinesthat have been produced and distributed inthe last few decades provide a goldmine ofvaluable materials for cultural observers. Inthe case of Asian American youth, web writingrepresents a place where they are prominentand visible as cultural producers. As notedabove, scholars, editors, book publishers andthe like have started to take note of the zines’significance in American cultural history.

But zine publishing brings challenges aswell as opportunity to those who would studythem. Their guiding aesthetic, as well as theconditions of their production, make themhard to study. In the first place, there are somany, both on-line and in print, that systemicapproach to the material is practically impos-sible. Furthermore, the zines often have irreg-ular production schedules (frequently tied tothe amount of free time the producer has) and

short lives: it’s impossible to know evenapproximately how many are in existence at agiven time, and a particular title might disap-pear altogether entirely without warning.Finally, zines can change their names fre-quently, at the whim of the author(s) or toconvey a new message; for instance, Sky Ryanchanged the name and focus of her zine withevery issue.6

The challenges posed by zines extendbeyond the practical: they call into questionsome fundamental tenets of the American cul-tural hierarchy while upending practices of thepopular culture industry. Perhaps the mostfundamental challenge is to the system of cul-tural value. There is still a dominant ideal thatwhat’s valuable must be lasting, as indicatedby the word “classic.” (Although the market-ing of the “instant classic” in our consumerage could be seen as making the notion of“lasting culture” irrelevant.) In order to evalu-ate zines, “disposability” must replace “last-ing” as a key concept. Disposable culture haspractical implications for scholars as well, asmost of the zines are not archived, particularlyin ways that are accessible to the public. Thecreator of Bamboo Girl, for instance, maintainsthe zine’s entire run—in her apartment(Margarita inteview). This means, simply put,that it can be hard to get your hands on a par-ticular run. While there are now some collec-tions that excerpt zine writing, these are, ofcourse, partial and biased. And because of thesheer volume of zines, it’s hard to make a casefor the importance of any particular one;

Rachel Rubin

20

5 Mark Kalesniko’s graphic novel Mail Order Bride (2001) works similar ground in its story of Kyung Seo, who turns outto be much stronger and more complex than her Canadian husband expects. This kinship points to the relationship betweenzine culture and the culture of underground comix.

6 Some of Ryan’s titles were Fuck Off and Die, Schmooze, 1985, Cryptic Crap, and How Perfectly Goddamn Delightful It All Is,To Be Sure. Factsheet Five Zine Reader, ed. R. Seth Friedman (1997), 90.

rather, analysts must read a large enoughnumber of that to get a sense of general cur-rents in a manner not unlike scholars whowrite about romance novels, or televisionshows.

The grassroots nature of zine productionand distribution also resists the academicframe. The “indie” aesthetic flies in the face ofthe “great artist” vision of literature—although many of the zines themselves areintensely personal. Distribution of the zineshas also attempted to remain outside of theculture industries; early zine writers describehanding out copies to strangers who caughttheir attention on the bus; while some zinesare carried by some bookstores, the majorityof them change hands much more informally.And with cyberzines, individual sites can belinked to other sites at will, and do not requirean apparatus of distribution beyond the tech-nology to access the internet. Therefore,incorporation of this body of work into thestory of American culture will necessitate arevised value system. Finally, since manyzinesters use computers or copy machines atwork to produce their zines, the inter-rela-tionships among culture, work and leisuremust be reevaluated.

To shed some light on the dramatic waysin which zine writing has transformed popularculture, this chapter has focused largely on aparticular hallmark of cyber-publishing: whatI have referred to variously as de-centered,anarchic, independent, outsider and democra-tic. The final, key question about the future ofcyberzines will be whether this productivechaos continues to characterize Internet rela-tionships. Will the possibility of “empower-ment through connectivity” (Weinstein andWeinstein 213) cede to the demands of anincreasingly regulated and centralized techno-

logical marketplace? Will the Internet as a(relatively) free and playful space for expres-sion give way to the Internet as ultimateachievement and perpetuator of cyber-capital-ism? Which will ultimately reveal itself aswhat the Internet has facilitated most: peer-to-peer communication—or business to cus-tomer? The number of creative and heartfeltzines on the Internet continues to grow every-day—but so does the number of pop-up ads,spam e-mail messages, and on-line megas-tores. In short, what opportunities theInternet offers to individuals and groups insearch of a workable identity, it can also takeaway, with its ability to co-opt, to commodify,to package and re-sell.

Cyberspace Y2K: Giant Robots, Asian Punks

21

WORKS CITED/FURTHER READING

Bell, David and Barbara M. Kennedy, eds. TheCybercultures Reader. New York:Routledge, 2000.

Denning, Michael. Mechanic Accents. NewYork: Verso, 1987.

Friedman, R. Seth. The Factsheet Five ZineReader: The Best Writing from theUnderground World of Zines. New York:Three Rivers Press, 1999.

Green, Karen and Tristan Taormino, eds. AGirl’s Guide to Taking Over the World:Writings from the Girl Zine Revolution.New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 1997.

Kalesniko, Mark. Mail Order Bride. Seattle,Fantagraphics Books, 2001.

Ling, Amy, ed. Yellow Light: The Flowering ofAsian American Arts. Philadelphia:Temple University Press, 1999.

Liu, Jeff. Interview with Rachel Rubin, 12August 2001.

Lupton, Deborah. “The Embodied ComputerUser.” Cybercultures Reader 477-488.

Marcus, Greil. Ranters & Crowd Pleasers: Punkin Pop Music, 1977-92.

New York: Doubleday, 1993.Margarita, Sabrina. Interview with Rachel

Rubin, 23 July 2001.Nakamura, Lisa. “Race in/for Cyberspace.”

Cybercultures Reader 712-720.Okihiro, Gary Y. Margins and Mainstreams:

Asians in American History and Culture.Seattle: University of Washington Press,1994.

Sterling, Bruce. “Short History of theInternet.” Magazine of Fantasy and ScienceFiction. February, 1993.

Tse, Holly. Interview with Rachel Rubin, 19July 2001.

Tuan, Mia. Forever Foreigners or Honorary

Whites?: the Asian Ethnic Experience Today.New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers UniversityPress, 1998.

Ueda, Reed. Postwar Immigrant America: ASocial History. New York: Bedford/St.Martin’s, 1994.

V. Vale, ed. Zines! San Francisco: Re/Search,1996.

Wei, William. The Asian American Movement.Philidelphia: Temple University Press,1993.

Weinstein, Deena and Michael A. Weinstein.“Net Game Cameo.” Cybercultures Reader210-215.

Wong, Kristina. Interview with Rachel Rubin,18 July 2001.

SELECTED ZINES

(Note: In the following list of particularlyinteresting zines with an Asian Americanfocus, I have done my best to include thezines’ Internet addresses. However, as I men-tion above, the nature of both zine publishingand Internet publishing is fairly ephermal. Insome cases, the address will have changed orthe zine may no longer exist.)

Angry Little Asian Girl (e-zine; www.angrylit-tleasiangirl.com)

Asian American Revolutionary Movement E-Zine(e-zine; www.aamovement.net)

AsiaZine (e-zine; www.asiazine.com)Bagong Pinay(e-zine; www.newfilipina.com)Bamboo Girl (paper zine)Banana Café (e-zine, http://www.bananacafe.

ca/0203/0203-16.htm)Big Bad Chinese Mama (e-zine; http://

www.bigbadchinesemama.com)[email protected] (e-zine; blast@explode.

com)

22

Dead Fish (e-zine; www.deadfish.com)Exoticize This! (Also called Exoticize My Fist!)

(e-zine; http://members.aol.com/Critchicks/)

Gas ‘n’ Go (paper zine)Geek the Girl (e-zine; www.nodeadtrees.

com/ezines/geekgirl)Giant Robot (paper zine)Gidra (e-zine; www.gidra.net)Half-Korean (e-zine; www.halfkorean.net)Hi-Yaa! (e-zine; http://www.hi-yaa.com/

index2.html)Koe (paper zine)Moons in June (paper zine)Evolution of a Race Riot (paper zine)Riot Grrrl Review (paper zine)Robot Power (paper zine)Shoyu (e-zine; http://shoyuzine.tripod.com/

shoyu2010/)slander (e-zine; www.worsethanqueer.com)Slant (paper zine)Tennis and Violins (paper zine)

23