Crianza indiferente, estres parental, desarrollo neural y problemas de conducta

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of Crianza indiferente, estres parental, desarrollo neural y problemas de conducta

A R T I C L E

DETACHED PARENTING AND TODDLER PROBLEM BEHAVIOR IN EARLY HEAD

START FAMILIES

BRENDA JONES HARDEN AND NICOLE DENMARKUniversity of Maryland

ALLISON HOLMESOptimal Solutions Group

MELISSA DUCHENEUniversity of Maryland

ABSTRACT: This study examined detached parenting among Early Head Start mothers, and associated maternal characteristics and child behavior.Participants included 81 mother–child dyads. Data were collected in participants’ homes during two visits. Mothers reported on demographic factors,parenting stress, and children’s problem behaviors. Children’s neurodevelopment was assessed, and videotaped parent–child play interactions werecoded. Path analyses indicated that demographic risk factors and parenting stress were associated with higher levels of detached parenting. As amediator, detached parenting significantly predicted children’s later problem behavior. There was a direct effect of parenting stress on children’sbehavior problems, but no direct effect of children’s neurodevelopmental risk. Detached parenting partially mediated the influence of parenting stresson children’s problem behavior. The final model moderately accounted for the variance in detached parenting and children’s problem behaviors. Theresults suggest that parents who experience multiple risks and high levels of parenting stress are more likely to demonstrate detached parenting. Inaddition, detached parenting leads to higher levels of toddler problem behavior, and may increase the problem behavior displayed by toddlers of parentsexperiencing multiple risks and parenting stress. These findings are discussed in the context of infant mental health practice.

RESUMEN: Este estudio examino la crianza indiferente o desconectada en madres del programa Early Head Start, y las caracterısticas maternalesasociadas y la conducta del nino. Participantes 81 dıadas madre-nino. La informacion se obtuvo en casa de los participantes durante dos visitas. Lasmadres reportaron acerca de factores demograficos, estres de crianza y conductas problematicas de los ninos. Se evaluo el desarrollo neural de los ninosy se codificaron las interacciones de juego madre-nino que habıan sido videograbadas. Los analisis crıticos indicaron que los factores demograficosde riesgo y el estres de crianza estaban asociados con mas altos niveles de crianza indiferente o desconectada. Como mediador, la crianza indiferentesignificativamente predijo la posterior conducta problematica del nino. El estres de la crianza produjo un efecto directo en los problemas de conductade los ninos, pero no se dio ningun efecto directo del riesgo de desarrollo neural de los ninos. La crianza indiferente o desconectada medio parcialmentela influencia del estres de crianza sobre la conducta problematica de los ninos. El modelo final moderadamente fue responsable de la variacion enla crianza indiferente y las conductas problematicas de los ninos. Los resultados sugieren que las madres que experimentan multiples riesgos y altosniveles de estres en la crianza estan mas propensas a mostrar una crianza indiferente o desconectada. Adicionalmente, la crianza indiferente lleva amas altos niveles de conducta problematica de los infantes, y pudiera aumentar la conducta problematica que muestran los infantes de madres queexperimentan multiples riesgos y estres en la crianza. Estos resultados se discuten dentro del contexto de la practica de salud mental infantil.

RESUME: Cette etude a examine le parentage detache chez les meres participant au programme americain de Early Head Start (programme d’aideaux familles de milieux defavorises), ainsi que le comportement de l’enfant et les caracteristiques maternelles qui y sont lies. Les participants ontcompte 81 dyades mere-enfant. Les donnees ont ete recueillies aux domiciles des participantes durant deux visites. Les meres ont rendu comptedes facteurs demographiques, du stress parental et des problemes de comportement des enfants. Le neurodeveloppement des enfants a ete evalue, etdes interactions parent-enfant filmees a la video ont ete codees. Les analyses causales ont indique que les facteurs demographiques de risque et le

This project was funded by a grant from the Administration on Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Direct correspondence to: Brenda Jones Harden, Department of Human Development, Benjamin Building, Room 3304, University of Maryland, College Park,MD 20742; e-mail: [email protected].

INFANT MENTAL HEALTH JOURNAL, Vol. 35(6), 529–543 (2014)C© 2014 Michigan Association for Infant Mental HealthView this article online at wileyonlinelibrary.com.DOI: 10.1002/imhj.21476

529

530 • B. Jones Harden et al.

stress parental etaient lies a de plus hauts niveaux de parentage detache. En tant que mediateur, le parentage detache predisait de facon importante lecomportement problematique ulterieur des enfants. On a note un effet direct du stress parental sur les problemes de comportement des enfants, sanscependant noter d’effet direct du risque neurodeveloppemental des enfants. Le parentage detache a partiellement servi d’intermediaire a l’influencedu stress de parentage sur comportement problematique des enfants. Le modele final a modere explique la variance dans le parentage detache et lescomportements problematiques des enfants. Les resultats suggerent que les parents qui font l’experience de plusieurs risques et de niveaux eleves destress sont plus a meme de presenter un parentage detache. De plus, le parentage detache mene a des niveaux plus eleves de probleme de comportementchez la petite enfance, et pourrait accentuer le comportement problematique dont font etat les petits enfants de parents faisant l’experience de plusieursrisques et de stress de parentage. Ces resultats sont discutes dans le contexte de la pratique de sante mentale du nourrisson et de la petite enfance.

ZUSAMMENFASSUNG: Diese Studie untersuchte distanziertes Elternverhalten bei Muttern, die an einem Early-Head-Start-Programm teilnahmen, unddie damit verbundenen mutterlichen Eigenschaften sowie das Verhalten der Kinder. Zu den Teilnehmern gehorten 81 Mutter-Kind-Dyaden. DieDaten wurden im Zuhause der Teilnehmer wahrend zwei Hausbesuchen gesammelt. Die Mutter berichteten uber demografische Faktoren, elterlichesStresserleben und das Problemverhalten der Kinder. Die neurologische Entwicklung der Kinder wurde bewertet und Eltern-Kind-Interaktionen, diewahrend des Spielens auf Video aufgezeichnet wurden, wurden kodiert. Pfad-Analysen zeigten, dass demografische Risikofaktoren und elterlichesStresserleben mit einem hoheren Grad an distanziertem Elternverhalten assoziiert wurden. Distanziertes Elternverhalten sagte als Mediator das spatereProblemverhalten der Kinder signifikant vorher. Elterliches Stresserleben hatte einen direkten Effekt auf das Problemverhalten der Kinder, jedoch keinendirekten Effekt auf das neurologische Entwicklungsrisiko der Kinder. Distanziertes Elternverhalten mediierte partiell den Einfluss von elterlichemStresserleben auf das Problemverhalten der Kinder. Das endgultige Modell erklarte maßig die Varianz hinsichtlich distanziertem Elternverhalten unddem Problemverhalten der Kinder. Die Ergebnisse deuten darauf hin, dass Eltern, die mehrere Risiken und einen hohen Grad an elterlichem Stresserleben eher distanziertes Elternverhalten zeigen. Zusatzlich fuhrt distanziertes Elternverhalten zu mehr Problemverhalten bei Kleinkindern und kanndas Problemverhalten, das Kleinkinder von Eltern mit mehreren Risiken und elterlichem Stresserleben zeigen, erhohen. Diese Ergebnisse werden imRahmen der Praxis zur psychischen Gesundheit von Kindern diskutiert.

ABSTRACT: ��:������������� ����������������detached parenting���������������������������������������81��������� ��!����2�����������������"#����������������� $�����������������������������%��&��

'!(��&�����)$*�����%+��&���,��-#��������./����� $������

���������������0��%�&���1!23���������������������������4����

������ $������������������%5 �%����������./��������6- ���

����������� $%����������70��4������������68!9������������

����������variance4����������-#����./4����������� $4�������������4�:�;<=���%���&�0�&#��������������������������6%:����./

��� $4�����0������ ��&�0����4���&;0�>����#��������������+

?@/ ���&�0�

��: �������������������������,��������������������������������������������������������,��������������������������,�����������������,�����������������������������������,���������������������������������,����������������������������������������������������������������������,���������������������������������������������,����������������������������������������������

* * *

Infant Mental Health Journal DOI 10.1002/imhj. Published on behalf of the Michigan Association for Infant Mental Health.

Detached Parenting • 531

Parenting, specifically in the context of parent–child rela-tionships, is the cornerstone of an infant mental health approach(Jones Harden & Duchene, 2011). The contribution of parent-ing to children’s development has been extensively documented(e.g., Collins, Maccoby, Steinberg, Heatherington, & Bornstein,2000). Specifically, the parenting that infants experience greatlyinfluences their concurrent as well as long-term socioemotionalfunctioning and mental health (Bornstein, 2002). Building on thefamily stress model (Conger et al., 2002), parenting is an importantpathway through which the stressors that families experience as aresult of circumstances of poverty and other risks affect children’soutcomes.

Much of the literature has dichotomized parenting processesas either positive or negative. Positive parenting is typically definedas warmth, responsiveness, involvement, and stimulation, con-structs that have been found to cohere in multiple studies (Burke,Pardini, & Loeber, 2008; Davidov & Grusec, 2006; Serbin & Karp,2004; Smith, 2010). There is abundant and robust evidence of pos-itive parenting among lower risk families and its strong link toa variety of positive child outcomes (Bocknek, Brophy-Herb, &Banerjee, 2009; Chang, Park, Singh, & Sung, 2009; Whiteside-Mansell, Bradley, & McKelvey, 2009). This relationship also isevident for children being reared in higher risk environments,including children from impoverished and disadvantaged minor-ity groups (Leidey, Guerrra, & Toro, 2010; Raviv, Kesernich, &Morrison, 2004). For example, many studies have documentedthat positive parenting (i.e., parental warmth, sensitivity, proactiveteaching, inductive discipline, and positive involvement) can actas a buffer against early family adversity, and promote school-age children’s positive adjustment across developmental domains(Chang et al., 2009; Coolahan, McWayne, Fantuzzo, & Grim, 2002;Parke et al., 2004; Pettit, Bates, & Dodge, 1997).

In contrast, negative parenting has been defined by such con-structs as intrusiveness, harshness, punitiveness, and detachment,which do not show a large overlap in empirical studies (Arnold,O’Leary, Wolff, & Acker, 1993; Ispa et al., 2004). There is a grow-ing literature base on negative parenting and its relation to adversechild outcomes (Karass & Walden, 2005). However, these find-ings are often based on studies which combine different aspects ofnegative parenting despite the potentially distinct processes whichcharacterize these types of parenting (Lipscomb et al., 2011; Steele,Nesbitt-Daly, Daniel, & Forehand, 2005).

Recently, researchers have attempted to disentangle distincttypes of negative parenting and their antecedents and consequences(Berlin, Brady-Smith, & Brooks-Gunn, 2002; Suchman & Luthar,2001). For example, harsh or punitive parenting has been examinedin multiple studies, and has been linked to a variety of compromisedchild outcomes such as developmental delay, poorer social skills,lack of emotion knowledge, emotion dysregulation, and increasedbehavior problems (Kim, Pears, Fisher, Connelly, & Landsverk,2010; Rhoades et al., 2011). Research on intrusive parenting hasrevealed that children experiencing this type of caregiving exhibitmore interpersonal negativity, less autonomy, and a higher level ofbehavior problems (Barber, 2002; Ispa et al., 2004).

Despite preliminary suggestion that detached parenting maybe distinct from other aspects of negative parenting (e.g., Tamis-LeMonda, Shannon, Cabrera, & Lamb, 2004), and may have dif-ferent antecedents (Smith, 2010) and potentially more negativeconsequences for children (Diego, Field, Jones, & Hernandez-Reif, 2006; Ryan, Martin, & Brooks-Gunn, 2006) than may haveother forms of negative parenting, detached parenting has receivedless attention in the parenting literature. Clearly, the construct ofdetached parenting deserves more research, and should includestudies which address how detached parenting is conceptualizedand operationalized as well as its antecedents and consequences.Although parental detachment cannot be equated with child ne-glect, examining the processes that are associated with parents’detachment and disengagement from their children also may con-tribute to our understanding of parents’ neglect of their children(Knutson, DeGarmo, Reid, & Koeppl, 2005). Further, an exam-ination of detachment can inform infant mental health servicesprovided to parents who may exhibit this form of compromisedinteraction with their young children.

In the current study, we explored detached parenting in EarlyHead Start (EHS) mother–child dyads, along with associatedchild/parent characteristics and child outcomes. Specifically, weexamined whether detached parenting was directly related to tod-dler problem behaviors in this group of high-risk families andwhether detached parenting mediated the relation of infant neu-rodevelopmental risk (i.e., infants’ risk for compromised neuro-logical and developmental outcomes), parenting stress, and demo-graphic risk to these problem behaviors.

Detached Parenting

Theory and research on attachment and emotion regulation under-score the importance of responsive, warm interactions betweenparents and their young children for a variety of positive de-velopmental outcomes (Lipscomb et al., 2011; Out, Bakersman-Kranenburg, & van IJzendoorn, 2009). As Cicchetti and Valentino(2006) suggested, parents who are not responsive and engagedmay be defying toddlers’ expectations that they will experiencea nurturing environment. Further, core developmental processesthat are linked to behavior problems may be affected by these de-tached parenting behaviors. Specifically, young children who donot experience active, engaged parenting, whether positive or neg-ative, do not have parents who can be models and scaffolds for thedevelopment of children’s self-regulatory skills (Cole, Michel, &Teti, 1994; Grolnik & Farkas, 2002; Shipman, Edwards, Brown,Swisher, & Jennings, 2005). These theoretical conceptualizationsargue for empirical examination of detached parenting as well asits antecedents and consequences.

Parenting scholars have defined detached parenting as parent-ing that is uninvolved and disengaged (Ryan et al., 2006), and lax(Brown, Arnold, Dobbs, & Doctoroff, 2007). It is not just reflectiveof the absence of positive parenting such as warmth and nurturancebut is characterized by the lack of any interaction with the child, in-cluding negative processes such as punitiveness and intrusiveness

Infant Mental Health Journal DOI 10.1002/imhj. Published on behalf of the Michigan Association for Infant Mental Health.

532 • B. Jones Harden et al.

(Levendosky & Graham-Berman, 2000; Out et al., 2009; Sosinsky,Carter, & Marakovitz, 2004). Some scholars have defined detachedparenting as neglectful (Kim, 2009; Wilson, Rack, Shi, &Norris, 2008). Although it can be argued that detached parent-ing is not tantamount to child neglect, it may be a precursor tothis extreme form of parenting. Scholars who study child neglecthave underscored the importance of examining distinct parentingprocesses and their relation to child outcomes (Knutson et al.,2005).

In Baumrind’s (1989) early conceptualizations of parent-ing processes, she described a group of parents who were lowon both of her major parenting dimensions—responsiveness anddemandingness—and exhibited parenting behaviors that could becharacterized as unengaged, neglectful, or both. More recently,scholars have suggested that detached parenting is a unique cat-egory of parenting, based on both self-report and observationalassessments. For example, Steele et al. (2005), using confirmatoryfactor analysis, documented that parental “laxness” was one oftwo parenting factors in the Parenting Scale (Arnold et al., 1993),a measure based on Baumrind’s two parenting dimensions (i.e.,warmth, control). In addition, Ryan et al. (2006) employed a clus-ter analytic approach, yielding data indicating that detachment is aspecific parenting pattern distinct from positive and other negativeparenting processes. Similarly, using a person-centered approach,Brady-Smith et al. (2013) identified supportive, directive, harsh,and detached parenting clusters among low-income families ofmultiple races/ethnicities, providing further data on detachment asa unique parenting process.

Although the extant literature has offered multiple definitionsand conceptualizations of this construct, a common strand acrossstudies is that detached parenting entails lower levels of parentalengagement with their children, which became the foundation ofour definition of detachment. Therefore, in the current study, weexamined parents’ physical and emotional disengagement fromtheir children, as measured via an observational paradigm, and theantecedents and consequences of this disengagement.

The limited literature on detached parenting has only begunto examine the antecedents and consequences of this type of par-enting. In a study examining parent gender, among other factors,Ryan et al. (2006) documented that mothers show higher levelsof detached parenting than do fathers. There also is some evi-dence that detached parenting is more likely displayed by parentsat high demographic and psychological risk. For example, in re-search addressing Baumrind’s three main styles of parenting (i.e.,authoritarian, authoritative, permissive), parents who were singleand had low education levels were found to display more pas-sive/permissive parenting (Coolahan et al., 2002). Tamis-LeMondaet al. (2004) also documented that detached parenting was morelikely to be demonstrated by mothers who had lower educationlevels. In their study examining the predictors of four key par-enting behaviors (i.e., supportiveness, detachment, intrusiveness,and negative regard/hostility), Berlin et al. (2002) documented thatadolescent mothers were more likely to display detached parentingthan were older mothers.

The literature linking broader conceptualizations of ecologi-cal risk, such as cumulative risk, and detached parenting is evenmore limited. Many studies have employed the cumulative risk ap-proach to examine outcomes among children from high-risk back-grounds (Burchinal, Roberts, Zeisel, Hennon, & Hooper, 2006;Yumoto, Jacobson, & Jacobson, 2008). However, only a few havefocused on demographic risk factors such as household size(Jenkins, Rasbash, & O’Connor, 2003; Pinderhughes, Nix, Foster,& Jones, 2001), residential instability (Gewirtz, DeGarmo,Plowman, August, & Realmuto, 2009; Pinderhughes et al., 2001),and family income source (Maupin, Brophy-Herb, Schiffman, &Bocknek, 2010).

Further, there is an established link between the accumula-tion of such risk factors and other aspects of negative parenting(Burchinal et al., 2013), including hostile and intrusive parenting.Parents’ experiences of stressors such as household crowding, mul-tiple moves, and reliance on public assistance (i.e., lacking incomefrom employment and family sources) could potentially lead tolower levels of engagement with their children. However, to ourknowledge, no studies have examined the link between detachedparenting and these risk factors, whether singly or as part of acumulative risk model. Thus, there is a need for research whichexamines detached parenting in the context of a broader range ofdemographic risk factors.

Although scant, there is some evidence of a link betweendetached parenting and parents’ psychological risk. For example,Burstein, Stanger, Kamon, and Dumenci (2006) documented thatparents who had internalizing problems were more likely to exhibitnegative parenting, including low levels of involvement and en-gagement. Further, depressed mothers have been found to be moredisengaged with their children than have nondepressed mothers(Pelaez, Field, Pickens, & Hart, 2008) and to provide lower levelsof stimulation for their children (Kohen, Leventhal, Dahinten, &McIntosh, 2008). A major gap in the literature exists regardingthe influence of other aspects of parental psychological function-ing on detached parenting. For example, parenting stress, whichhas been documented in numerous studies to have an impact onparenting behaviors and resultant child outcomes (Gershoff, Aber,Raver, & Lennon, 2007; Mistry, Vandewater, Huston, & McLoyd,2002; Whittaker, Jones Harden, See, Meisch, & Westbrook, 2011),may diminish parents’ motivation for and capacity to interact andengage with their children. Therefore, we examined whether par-enting stress does indeed contribute to detached parenting in thecurrent study.

There is a large literature on the child-specific influences onparenting. For example, children who have perinatal complica-tions (e.g., prematurity, low birth weight), neurological and de-velopmental challenges, and difficult temperament are more likelyto elicit negative interactions and caregiving behaviors from theirparents (Goldberg & DiVitto, 2002; Putnam, Sanson, & Rothbart,2002). Given these findings, it may be that some parents of in-fants with neurodevelopmental challenges disengage from theirchildren rather than engage in a negative manner with them. How-ever, the influence of neurodevelopmental risk factors on detached

Infant Mental Health Journal DOI 10.1002/imhj. Published on behalf of the Michigan Association for Infant Mental Health.

Detached Parenting • 533

parenting, in particular, has not received empirical attention. Thereis evidence that children with early neurodevelopmental risk areprone to later behavior problems (Campbell, 2006; Magill-Evans& Harrison, 2002). It is possible that the early behaviors exhibitedby such children may lead to parental disengagement, as parentsfeel ill-equipped to manage the demands that these children placeon the caregiving relationship (Kochanska, Friesenborg, Lange, &Mantel, 2004; Neitzel & Stright, 2004).

Although the data are limited, the association between de-tached parenting and adverse child outcomes has been documented(Chang et al., 2009). Specifically, Ryan et al. (2006) found a re-lation between negative parenting and lower infant Bayley mentalscores, with infants experiencing detached parenting having thelowest scores. In a study of infant attachment, infants who experi-enced disconnected parental behavior were more likely to displayattachment disorganization (Out et al., 2009). Research that exam-ined child physiological correlates of their parenting experiencehas documented that lower maternal engagement in infancy wasassociated with greater cortisol reactivity during infancy and witha reduced overall cortisol level during toddlerhood (Blair et al.,2008). In another study of parental engagement and child physi-ologic outcomes, Murray, Halligan, Goodyer, and Herbert (2010)found that observed parental “withdrawal” or disengagement dur-ing infancy (as opposed to age 5 years) was related to highercortisol production at age 13 years.

Bocknek, Brophy-Herb, Fitzgerald, Burns-Jager, and Carolan(2012) explored the concept of “psychological absence,” a latentconstruct comprised of self-reported parental distress, self-reportedlack of empathy for the child, and observed detachment. Theyfound that psychological absence was related to less supportiveand engaged parent–child interaction, which was associated withlower child engagement, attention, and regulation. Based on clusteranalyses, Brady-Smith et al. (2013) also found lower engagementand emotion regulation among children of mothers exhibiting de-tached parenting, when compared with those in other parentingclusters.

Using an experimental paradigm, Karrass and Walden (2005)documented that children who were exposed to unresponsive andnonnurturing caregiving displayed less positive emotion and fewersocial initiatives with another adult, when compared to childrenexposed to nurturing caregivers (i.e., those who were warm, sensi-tive, and responsive). Studies of older children have yielded find-ings of an association between detached or uninvolved parentingand childhood depression (Mahoney, Schweder, & Stattin, 2002;Simons et al., 2002). Finally, in one study of children in early el-ementary school, lower levels of parental warm involvement wererelated to children’s oppositional behavior (Stormshak, Bierman,McMahon, Lengue, & Conduct Problems Research Group, 2000).

Whereas there is a large body of research which has docu-mented the association between negative parenting processes andchild behavior problems (see Campbell, 2006), there has been lim-ited research on the link between detached parenting and youngchildren’s behavior problems. Early behavior problems are a re-flection of young children’s inability to perform age-appropriate

socioemotional tasks such as emotion expression, delay of gratifi-cation, and self-regulation (Baillargeon et al., 2007). Because earlybehavior problems are such an important predictor of subsequentchild functioning (Campbell, Shaw, & Gilliom, 2000), it is im-portant to examine the factors that contribute to young children’sproblem behavior, including child characteristics, environmentalrisks, and specific aspects of parenting.

Current Study

In sum, the available literature has pointed to an increased likeli-hood of negative parenting among high-risk families with youngchildren. Given the data documenting distinct types of negativeparenting, it is important to disentangle these processes and ex-amine the unique contributions of specific types of parenting tochild outcomes. Unlike other negative parenting processes (i.e.,intrusiveness, punitiveness), there has been limited research on de-tached parenting and its antecedents and consequences for youngchildren. Further, studies on detached parenting have not fullyaddressed the risk factors that may contribute to this type of par-enting. Building on the research documenting the relation betweenother forms of negative parenting (e.g., intrusiveness, hostility)and demographic risks and neurodevelopmental risks (Goldberg &DiVitto, 2002), the parenting literature would benefit from stud-ies that examine the contribution of these risk factors to detachedparenting.

To address this gap in the literature, the current study exploredthe phenomenon of detached parenting through an observationalparadigm. Based on the available literature, we defined and oper-ationalized detached parenting as parents’ physical and emotionaldisengagement from their children. Further, using the family stressmodel (Conger et al., 2002) as a foundation, we conceptualized thatparents who experienced many stressors may demonstrate nega-tive parenting, specifically detachment, which would lead to com-promised child outcomes. Thus, we examined the contribution ofstressors at multiple levels (i.e., demographic risk, parent psycho-logical risk, and child risk) to detached parenting, and subsequentchild behavior problems.

We hypothesized that maternal detached parenting at Time 1would predict toddler problem behavior at Time 2. Further, we hy-pothesized that increased demographic risk, higher levels of parent-ing stress, and infant neurodevelopmental risk would be related todetached parenting and toddler problem behavior. Finally, we wereinterested in examining the mediating role of maternal detachedparenting, and hypothesized that it would at least partially mediatethe relation of demographic risk, parenting stress, and infant neu-rodevelopmental risk (i.e., at risk for compromised neurologicaland developmental outcomes) to toddler problem behavior.

METHOD

Participants

This study is part of a larger study of the risk factors for toddlerbehavior problems in a low-income sample of mother–child dyads.

Infant Mental Health Journal DOI 10.1002/imhj. Published on behalf of the Michigan Association for Infant Mental Health.

534 • B. Jones Harden et al.

TABLE 1. Participant Characteristics (N = 81)

Characteristic M (SD)/%

Mother Age 25.25 (6.73)Mother Education (years) 11.74 (1.99)Mother Race/Ethnicity

African American 80.2Hispanic American 4.9European American 1.2

Mother EmploymentNo Work Outside Home 21.0Full-Time 27.2Part-Time 21.0Unemployed; Looking for Job 30.9

Mother Live With PartnerYes 34.6No 65.4

Child Age Time 1 (months) 16.68 (5.69)Child Gender

Male 48.1Female 51.9

Participants included 81 mother–child dyads who were recruitedfrom EHS centers. Children (48.1% male) were between the agesof 4 and 25 months (M = 16.68, SD = 5.69) at Time 1, and12 and 35 months (M = 25.92, SD = 6.01) at Time 2. Motherswere primarily African American (80.2%), with a mean age of25.25 years (SD = 6.73) and mean education of 11.74 years (SD =1.99). Most mothers had never been married (65.4%). Regardingemployment, almost half (48.2%) had some form of employment(for further information regarding study participants, see Table 1).

The current sample was restricted to cases in which therewere Time 1 videotapes of parent–child interaction and maternalreports of Time 2 behavior problems. A post hoc analysis of vari-ance showed that there were no significant differences in Time 1demographic characteristics between those participants who par-ticipated in the Time 2 visit and those who did not, on the followingcharacteristics: mother’s age, t(112) = .99, p > .05; mother’s race,t(112) = .57, p > .05; number of years of school completed, t(112)= .57, p > .05; total monthly income, t(92) = .22, p > .05; andchild’s gender, t(112) = .25, p > .05. Therefore, Time 2 data forchild socioemotional functioning did not appear to be missing as aresult of a particular parent or child demographic variable, at leastof those measured in the current study.

Procedures

Two visits to the mothers’ homes were conducted approximately6 months apart, during which data were collected by trainedmembers of the research team. If the mother was unwilling orunable to complete the visit in her home, the visit was conductedat her EHS center. Informed consent was obtained at the begin-ning of each visit. At the end of each visit, mothers were given$50 for their participation in the study. Researchers were trained

in standardized interviewing procedures and specialized observa-tional procedures, as described later.

During the Time 1 visit, we administered self-report question-naires to mothers on a variety of background and risk variables, andwe assessed infants’ neurodevelopment. In addition, mother–childdyads participated in a videotaped, free-play interaction with toysprovided by the research team. During the Time 2 visit, mothersreported on their toddler’s socioemotional functioning, includingproblem behavior.

Measures

Observation, direct test, and self-report measures were used in thecurrent study. Measures were selected that had been used withfamilies from high-risk backgrounds. Many of the measures wereselected because they had been used and validated in the EarlyHead Start Research and Evaluation Project, a large-scale study(n = 3,001 families) designed to assess the impact of EHS on childand family outcomes (Administration for Children and Families,2002).

Infant development was measured using the Bayley InfantNeurobehavioral Screener (BINS; Aylward, 1995). The BINS isa 10-min screening tool used to determine 3- to 24-month-oldchildren’s risk for neurodevelopmental and other developmentaldelays. Graduate students were trained to administer the BINS bythe first author, who has clinical training and experience in theadministration of the full Bayley Scales of Infant Development.Students were trained during the pilot phase, and needed to bewithin 90% agreement with the trainer on 3 children in the pilotgroup before doing assessments for the formal study. Booster train-ing sessions occurred throughout the course of the data-collectionphase of this project.

The BINS is comprised of a subset of items from the BayleyScales of Infant Development plus items that address infant neu-rologic status. Four domains are assessed: neurological function,expressive function, receptive function, and cognitive processes.Scores are used to create classifications of low, moderate, or highrisk. Good psychometric properties for the BINS have been re-ported, including test-retest reliabilities ranging from .71 to .81,interrater reliabilities ranging from .79 to .96, and internal consis-tency reliabilities ranging from .73 to .85 (Aylward, 1995). TheBINS also has been found to be a valid predictor of developmentaldelay (Aylward, 1995). The continuous BINS scores were used inthe current analysis, with higher levels indicating lower risk fordevelopmental delay.

The Brief Infant–Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment(BITSEA; Briggs-Gowan & Carter, 2006) was used to measure tod-dler’s problem behaviors. The total scale consists of 42 items andmeasures socioemotional problems and competencies in infantsand toddlers from 12 to 36 months. All children in our samplewere 12 months or older by the second home visit, so the BITSEAwas developmentally appropriate for them. Examples of statementsfor the problem domain include: “Is restless and can’t sit still” and“Breaks or ruins things on purpose.” Responses range on a Likert-

Infant Mental Health Journal DOI 10.1002/imhj. Published on behalf of the Michigan Association for Infant Mental Health.

Detached Parenting • 535

type scale of (not true/rarely) to (very true/often). Briggs-Gowan,Carter, Irwin, Wachtel, and Cicchetti (2004) reported acceptableinternal consistency (α = .79) for the problem domain. For oursample, the internal reliability also was good (α = .76) for theproblem domain. Criterion-related validity for both subscales ofthe BITSEA has been established with the Child Behavior Check-list 11/

2 – 5 (CBCL 11/2 – 5; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000).

Both subscales of the BITSEA also have been shown to have goodpredictive validity in an ethnically and socioeconomically diversesample of infants and toddlers (Briggs-Gowan & Carter, 2008).

Parenting stress was measured using the Parenting Stress In-dex Short Form (PSI/SF; Abidin, 1990). This 38-item measurecontains three subscales: Parental Distress, Parent–Child Dysfunc-tional Interaction, and Difficult Child, as well as a Total Stressscore. Using a 5-point Likert-scale ranging from (strongly dis-agree) to (strongly agree), parents indicated how much they agreedwith statements such as: “I sometimes feel like I cannot handlethings very well,” and “My child does not smile as much as otherchildren.” We used the Total Stress score on the PSI.SF, whichhas a high correlation (.94) with the Total Stress score of the full-length PSI (Abidin, 1990). This measure also has been found tohave test-retest reliability of .84 and good internal consistency(α = .91; Abidin, 1990). The internal reliability for our samplealso was good (α = .87).

Detached parenting was assessed at Time 1 via videotapedparent–child play interactions which were coded using the Parent-Child Interaction Rating Scale (PCIRS; Sosinsky et al., 2004).The videotaping consisted of a 20-min, free-play episode with themother and baby using standardized toys provided by the graduatestudents. Toys were selected to be age-appropriate for both infantsand toddlers, and included soft books, pop-up toys, shape sorters,soft balls, Sesame Street puppets, plastic cars and people, toy keys,and toy telephones. Prior to taping, graduate students laid the toyson a clean blanket on the floor. Mothers were asked to engagewith the child the way that they normally would, but also to facethe camera as much as possible. When the 20 min were complete,graduate students informed the mother and then transitioned to theinterview portion of the visit. Mothers received a copy of theirinteractions on a DVD as an incentive for their participation.

The PCIRS coding scheme used in this study was designed forsemistructured observations of mothers and their children in teach-ing tasks or free-play tasks. It was adapted from the Mother-ChildInteraction Rating Scales (Vandell & Owen, 1999), the Caregiver-Child Affect, Responsiveness, and Engagement Scales (Tamis-LeMonda, Ahuja, Hannibal, Shannon, & Spellman, 2002) whichwere used in the National Institue of Child Health and Human De-velopment Early Child Care Research Network Study and the EarlyHead Start Evaluation (Administration for Children and Families,2002), respectively, as well as from the Parent-Child Early Rela-tional Assessment (Clark, 1985). The codes for maternal behav-iors included sensitivity/responsivity, supportive presence, intru-siveness, respect for autonomy, detachment, cognitive stimulation,positive regard, negative regard, flatness, language amount, andlanguage quality. For each rating, mothers are scored between 1

(behavior not at all characteristic of the mother) and 7 (behaviorhighly characteristic of the mother). In the validation study forthis measure, trained coders maintained above 90% agreement ondoubly coded tapes, and the weighted kappas for pairs of codeddata were .61 (“substantial agreement”). In terms of predictive va-lidity, the positive parenting behaviors (sensitivity, supportiveness,positive regard) predicted less child dysregulation and higher lev-els of social competence longitudinally as measured by the ITSEAwhereas maternal detachment was negatively related to child socialcompetence scores, r = −.30 (Sosinsky, Carter, & Briggs-Gowan,2007).

Two doctoral student coders were trained by the first author ofthe coding scheme, using master videotapes displaying the variouscoded behaviors. The senior coder reached reliability (exact agree-ment within 1 point) to a criterion of 90% with the author/trainerof the PCIRS using these master tapes. The senior coder and sec-ond doctoral student coder used pilot tapes to reach reliability andachieved 80% overall agreement on codes. Similar criterion levelsfor interrater reliability were set for the Early Head Start NationalResearch and Evaluation Study (85% agreement criterion) (Berlinet al. 2002) and for the Family Life Project (intraclass correlation of.80) (Pungello, Iruka, Dotterer, Mills-Koonce, & Reznick, 2009).Twenty percent of the tapes were randomly doubly assigned anddrawn biweekly to assess interrater reliability. The coders main-tained the minimum average of 80% agreement for all codes, and86% overall agreement on the maternal detachment codes (Thisis averaging 95% agreement for detachment and 76% agreementwith flatness.) For cases in which there was a discrepancy in codesof 2 or more points, the two codes were discussed, coders reachedconsensus, and the consensus score was used.

Sosinsky et al. (2004) created the PCIRS by adapting cod-ing schemes that had been developed for other studies examiningparent–infant interaction. This was done to allow for items thatcrossed the developmental spectrum from early infancy to toddler-hood, and that broadened the number and type of parent and dyadconstructs that could be examined. In the current study, scoresfor maternal detachment/disengagement and maternal flatness ofaffect were combined to create a maternal detachment compos-ite score. Because “flatness” has been found to be an indicator ofdisengagement in research on high-risk parents and their youngchildren (e.g., Field et al., 1991; Field, Diego, Hernandez-Reif,Schanberg, & Kuhn, 2003), we elected to combine those scoreswith those of the detached parenting behaviors. We also felt it im-portant to incorporate affective disengagement, which was a salientbehavior within the “flatness” code.

Markers of the parental detachment/disengagement code inthe PCIRS include rare involvement with the child in play; failureto respond to the child’s social bids; failure to respond to behaviorand situations that call for adult regulation of child experience; dis-ciplinary responses which are half-hearted and inconsistent; longstretches of unoccupied time or wandering without directing thechild to an activity; ignoring the child’s difficulties with the physi-cal environment, especially where such difficulties are emotionallystressful for the child; preoccupation with their own activities; and

Infant Mental Health Journal DOI 10.1002/imhj. Published on behalf of the Michigan Association for Infant Mental Health.

536 • B. Jones Harden et al.

conveying any message that implies “don’t bother me” or “you’reunimportant.” Detachment/disengagement was rated on a Likertscale of 1 (very low detachment) to 7 (very high detachment). Theflatness of affect code assessed mothers’ animation with her child.Markers of flatness include blank, impassive facial expressions,an inexpressive voice, and lack of animation in body movements.Mothers’ flatness was rated on a scale of 1 (very low flatness) to 7(very high flatness). Mothers’ detachment/ disengagement and flat-ness scores were correlated at r = .51. As noted, these codes weresummed, and the resulting detachment composite score, whichtheoretically could have ranged from 2 to 14, had a mean of 4.2,SD = 2.1, range = 1–9.

Demographic information at baseline was derived froma questionnaire created for the purposes of the current study.Specifically, we created a cumulative risk index based on thefollowing indicators: (a) household overcrowding (i.e., six or morepeople), (b) household size (i.e., total number of persons residingin home), (c) residential instability (i.e., two or more moves in thelast year), (d) single mother in the home, (e) mother has less than ahigh-school degree, (f) receipt of public assistance, and (g) motheris unemployed. Mothers were given a score of 1 or 0 for eachindicator based on its presence (for descriptive statistics on the riskindicators, see Table 1). A cumulative (i.e., summative) risk vari-able was constructed from the dichotomized risk scores for eachindicator. In this sample, cumulative risk ranged from zero riskfactors to six risks (i.e., all of them). Cumulative risk indices havebeen used in multiple studies of the development of children fromhigh-risk backgrounds, and have been found to predict negativeoutcomes in these groups of children (e.g., Burchinal et al., 2006).The cumulative risk variable was used in subsequent analyses.

RESULTS

Path analysis was used to test the research questions for this study.Because the sample was relatively homogenous and because wewere including important demographic variables that are typicallyused as controls in our measure of demographic risk, we did notinclude covariates in the model. Preliminary analysis included de-scriptives for each variable, which are summarized in Table 2. Asis delineated in Table 3, detached parenting was significantly cor-related with parenting stress, r = .36, p < .001, demographic risk,r = .24, p = .03, and toddler problem behavior, r = .38, p < .001. Asignificant correlation was not found between detached parentingand child developmental risk. Toddler problem behavior also wassignificantly associated with parenting stress, r = .44, p < .001,and demographic risk, r = .26, p = .02.

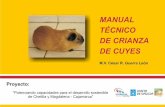

Path analyses were estimated using Mplus 5.0 (Muthen &Muthen, 2008). The full hypothesized model was overfit; the finalmodel after trimming is presented in Figure 1. Fit indices indicatedthat the final model adequately represented patterns within thedata. The chi-square test statistics were not significant, χ2 = 2.62,p = .27. The comparative fit indices (CFI; CFI = .98) and Tucker–Lewis indices (TLI; TLI = .94) also suggested that the proposedmodel provided a reasonably good fit to the data. Further, the joint

TABLE 2. Descriptives for Mother/Child Factors and DetachedParenting (n = 81)

M SD Range

BITSEA 13.5 5.8 2–28PSI 70.6 17.4 37–110Detachment 4.2 2.1 1–9Risk 3.7 1.5 1–6

Distribution of Risk for Developmental Delays (N = 81)

Frequency %

Low 37 45.7Moderate 40 49.4High 4 4.9

BITSEA = Brief Infant–Toddler Social & Emotional Assessment; PSI = ParentingStress Index Short Form.

TABLE 3. Bivariate Correlations Among Mother/Child Factors andDetached Parenting

PSI BITSEA BINS Detachment Risk

PSIBITSEA 0.439∗∗

BINS −0.241∗ −0.189Detachment 0.361∗∗ 0.375∗∗ −0.142RISK 0.113 0.262∗ −0.071 0.242∗

PSI = Parenting Stress Index Short Form; BITSEA = Brief Infant–Toddler Social& Emotional Assessment; BINS = Bayley Infant Neurobehavioral Screener.∗p < .05. ∗∗p < .01.

fit criterion for root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA)of .06 and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) of .03also were less than or equal to the recommended level for close fit(RMSEA = .06, SRMR = .09). Similarly, the CFI and the SRMRmet joint fit criterion (CFI � .96, SRMR � .09). Given evidenceof reasonable model fit, associations among model indicators wereexamined.

Results indicate that higher levels of demographic risk,β = .21, p = .041, and parenting stress, β = .34, p < .001,were associated with detached parenting. The mediator detachedparenting significantly predicted toddlers’ later problem behavior,β = .24, p = .016. There was a direct effect of parenting stress,β = .33, p < .001, on toddlers’ problem behavior. Detached par-enting partially mediated the relation of parenting stress to toddlerproblem behavior, β = .08, p = .026. Contrary to our hypothesis,infant neurodevelopmental risk was not related to toddler problembehavior.

Also note that removal of direct paths from demographic riskto toddlers’ problem behavior resulted in the best fitting model,suggesting that demographic risk was fully mediated by detachedparenting. Parenting stress was partially mediated by detached par-enting, such that a standard deviation increase in parenting stress

Infant Mental Health Journal DOI 10.1002/imhj. Published on behalf of the Michigan Association for Infant Mental Health.

Detached Parenting • 537

Demographic Risk(# people in house, educa�on,

cohabita�on, public aid,employment, moves)

Stress(PSI)

ProblemBehaviors(BITSEA)

Detachment(Detachment and

FlatnessComposite)

Child Risk(BINS)

0.24*

R2 = 0.25**

R2 = 0.17*

0.21*

0.10

-0.23*

-0.07

0.33***

0.34***

FIGURE 1. Path analysis estimation of the theoretical model predicting parent detachment and toddlers’ later behavior problems, with parent detachment as mediator,standardized path coefficients (N = 81), χ2= 2.62, p = .27; CFI = .98; TLI = .94; RMSEA = .06; SRMR = .03. ∗p < .05. ∗∗p < .01. ∗∗∗p < .001. PSI = ParentingStress Index Short Form; BINS = Bayley Infant Neurobehavioral Screener; BITSEA = Brief Infant–Toddler Social & Emotional Assessment.

resulted in an .08 increase in the effect of maternal detached parent-ing on toddlers’ problem behavior. The final model moderately ac-counted for the variance in detached parenting and toddlers’ prob-lem behavior: Demographic risk and parenting stress explained17% of the variance in mothers’ concurrent detached parenting,and parenting stress and detached parenting explained 25% of thevariance in toddlers’ later problem behaviors.

DISCUSSION

The goal of this study was to further our understanding of de-tached parenting, one form of negative parenting, and its potentialconsequences for young children’s development. Findings fromthe current study provide further evidence of the link between de-tached parenting and toddler problem behavior. The combinationof the demographic risk and parenting stress variables explaineddetached parenting to some extent. In addition, detached parent-ing partially mediated the relation between parenting stress andtoddlers’ problem behaviors. Contrary to our expectations, infantneurodevelopmental risk was not related to detached parenting orto toddlers’ problem behaviors.

Detached parenting emerged in the current study as a salientcontributor to child outcomes. Thus, the results of this study un-derscore the importance of examining this specific type of parent-ing behavior in high-risk families, separate from other forms ofnegative parenting. Although we did not examine other forms ofparenting processes in the current study, the absence of or limitedexpression of any parenting interaction, both positive and neg-ative (Levendosky & Graham-Berman, 2000; Out et al., 2009),seems to be important for toddlers’ outcomes. In the observa-

tional coding scheme used for the current study, detached behav-iors were defined as the lack of awareness of the child, of respon-siveness to the child, and of interaction with the child (Sosinskyet al., 2004). Such behaviors also have been described in researchon neglectful parents, whose disengaged behaviors are so severethat they lead to child harm (Kim, 2009; Wilson et al., 2008;Zuravin, 1999).

The link between negative parenting behaviors and adversechild outcomes has been well-documented (e.g., Karass & Walden,2002; Pelaez et al., 2000; Rhoades et al., 2011). Parent behaviorsthat involve negative interactions with the child such as intrusive-ness and punitiveness precipitate negative child behaviors such asoppositionality and defiance (Hipwell et al., 2008; Ispa et al., 2004).However, this study filled a gap in the literature by specificallyexamining the contribution of detached and disengaged parentalbehaviors to toddlers’ problem behaviors. Thus, we found thatthe lack of maternal interaction and expression is detrimental toyoung children’s socioemotional functioning. Consistent with thetheory and research on attachment and emotional regulation in in-fancy and toddlerhood (Cicchetti & Valentino, 2006; Cole et al.,1994; Grolnik & Farkas, 2002; Vando, Rhule-Louie, McMahon, &Spieker, 2008), the toddlers who did not experience involved andengaged parenting were more likely to have regulatory challenges,as evidenced by their increased problem behavior.

Beyond the role of detached parenting in the developmentof adverse child outcomes, parenting stress emerged as a salientpredictor of toddler problem behavior in the current study. It iswell-known that parent psychological status can affect parentingbehaviors (Zahn-Waxler, Dugal, & Gruber, 2002). For example,there is a wealth of data on the compromised parenting of depressed

Infant Mental Health Journal DOI 10.1002/imhj. Published on behalf of the Michigan Association for Infant Mental Health.

538 • B. Jones Harden et al.

parents and resultant negative child outcomes (e.g., Goodman &Brand, 2009; Gravener et al., 2012). Although not as vast, the lit-erature pointing to the strong relation between parenting stress andadverse child outcomes has been growing rapidly (Crnic, Gaze, &Goodman, 2005; Neece, Green, & Baker, 2012). Parenting stressalso was a strong predictor of detached parenting in the currentstudy. These findings extend research that has underscored therelation between parenting stress and lower levels of positive par-enting, such as sensitivity and warmth (e.g., Whittaker et al., 2011)and higher levels of hostile, punitive parenting behaviors (e.g.,Suchman & Luthar, 2001). Mothers who experience elevated lev-els of parenting stress may be so overwhelmed with the parentingexperience that they cannot engage or interact with their children atall, even in a negative manner. This “blunted” affect and behaviorhave been reported in individuals who experience other types ofstress, such as the “emotional numbness” found in individuals withposttraumatic stress disorder (Forbes et al., 2011).

In addition, cumulative demographic risk was related to ma-ternal detached parenting in the current study. This finding is con-sistent with research suggesting that cumulative demographic riskleads to compromised parenting in low-income families (Burchinalet al., 2006). Specifically in regard to detached parenting, the cur-rent findings corroborate data from other studies on the relation ofthis form of parenting to specific maternal characteristics such asmarital status and educational level (Coolahan et al., 2002). Thisstudy extends extant research by also documenting the relation be-tween maternal detached parenting and demographic risk factorssuch as large household size and residential instability, which aretypically not examined in studies of parenting processes. How-ever, there is a documented link between such demographic riskfactors and poor child outcomes (Evans & Wach, 2010), whichcould be exacerbated by negative parental behaviors. Specifically,overcrowded households, particularly with large numbers of chil-dren, and the stress of having to make multiple moves could leadto parents’ lack of involvement with and disengagement fromtheir children, and ultimately worse developmental outcomes forchildren.

Multiple studies have documented the link between cumu-lative risk and child outcomes (Burchinal et al., 2006; Yumotoet al., 2008). Consistent with this large literature, cumulative de-mographic risk was initially correlated with toddler problem be-havior. However, in the path analysis, it appeared that parentingstress was a more salient predictor of child outcomes than was cu-mulative demographic risk. This finding can be interpreted throughthe lens of family stress theory and the empirical literature that haspointed to parental functioning and behaviors as having a more po-tent influence on children’s outcomes than do other environmentalfactors, even if they exist in the immediate caregiving environment(Conger et al., 2002; McGrath & Sullivan, 2003). There is evidencethat how parents cope with stressors emanating from demographicrisk factors and how they parent their children have more primacyfor child development than do the stressors themselves (Mistryet al., 2002; Taylor, Larsen-Rife, Conger, Widaman, & Cutrona,2010).

In contrast to our expectations, children’s neurodevelopmen-tal status was not related to detached parenting or to child problembehavior. There is ambiguity in the research about the relationbetween developmental status of the child and the quality of par-enting a child experiences (Baker, Blacher, Crnic, & Edelbrock,2002; Van Bakel & Riksen-Walraven, 2002; Verhoeven, Junger,Van Aken, Dekovic, & Van Aken, 2007). No link between neurode-velopmental status and parenting emerged herein, findings whichsupport the evidence that developmental status does not influenceparenting processes.

Because the majority of the children in the current study werenot found to be at high risk for developmental delay, the lack ofa link between neurodevelopmental status and detached parentingmay be an artifact of this sample. Note that the measure used in thecurrent study is a screener, and places children in gross categories ofrisk (i.e., high, medium, low) (Aylward, 1995). Thus, the use of thismeasure may have obscured more refined differences in children’sdevelopment, and may have led to an imprecise identification ofchildren who are most at risk for developmental delay. In addition,one study found low predictive value of this measure with childrenwhose developmental delay may be due to environmental, ratherthan biological, risk (Hess, Papas, & Black, 2004).

Finally, our hypotheses about the mediating role of detachedparenting were partially supported. Parenting stress was a potentpredictor of toddler problem behavior in and of itself, and wasmediated somewhat by detached parenting. Although few re-searchers have examined the mediating role of detached parentingin the relation between parent psychological functioning and childoutcomes, there is evidence that other parenting processes can en-hance or attenuate the effect of parental psychological functioningon child outcomes. Specifically, Mistry et al. (2008) documentedthe mediating role of parenting between parental psychologicalrisk and child socioemotional outcomes. Results from the currentstudy extend such findings by documenting the link between lev-els of parenting stress, detached parenting, and toddler problembehavior. Therefore, it appears that mothers’ perception of parent-ing stress compromises the quality of their interactions with theirchildren in a play situation (i.e., increased detachment) and thusincreases toddlers’ problem behaviors. This finding underscoresthe vulnerability of children who live with parents who experiencehigh levels of stress with respect to their parenting role and thuspotentially disengage from their children.

Limitations and Research Directions

Although this study has addressed a significant gap in the liter-ature on parenting processes in low-income families with youngchildren, there are several limitations that warrant discussion. First,this study has limited generalizability due to the homogeneity of thesample on specific demographic variables and the relatively smallnumber of participants. Future research should include larger sam-ple sizes with more representation of other racial/ethnic groupsand a broader range relative to socioeconomic status. A largersample would allow for the examination of a wider range of risk

Infant Mental Health Journal DOI 10.1002/imhj. Published on behalf of the Michigan Association for Infant Mental Health.

Detached Parenting • 539

factors and child outcomes, and a more explicit investigation ofthe relation of specific risk factors to detached parenting and childoutcomes. In adition, there was a wide age range for the infantparticipants. Given the rapid changes that occur during infancy, anarrower age range would have allowed for clearer interpretationof infant outcomes, such as behavior problems.

Beyond the self-report of child outcomes used in this study(i.e., parent perceptions of problem behavior), future studies couldemploy observational and direct assessment approaches for exam-ining child outcomes. Further, research on this phenomenon shouldinclude additional time points (i.e., �three) so that the stability ofdetached parenting could be examined, as well as the trajectory ofchild outcomes that result from this type of caregiving experience.

The phenomenon of detached parenting is ripe for further em-pirical investigation. First, there is a need for a more refined exam-ination of this construct, both conceptually and methodologically.For example, further exploration of the distinction between de-tached parenting and the lack of positive parenting (e.g., warmth)and of negative parenting (e.g., punitiveness) is important, as isthe overlap or distinction between detached parenting and otheraspects of negative parenting. More careful identification of thebehaviors that reflect detached parenting also is critical to improveassessments of this construct. Examination of extreme detachedbehaviors, as in child neglect, would contribute to such efforts.There also is a need to address the influence of culture on theconceptualization, operationalization, and assessment of detachedparenting because parenting behaviors may have different mean-ings across cultures (Wang, Wiley, & Zhou, 2007).

Finally, the study of parental detachment would benefit fromincreasing the types of predictors and outcomes examined beyondwhat was available to us in the current study. In particular, it seemsimportant to conduct research on factors related to parental func-tioning that may be associated with detachment, such as depressionand chaos in the home environment. Child-specific factors, suchas difficult temperament, that might lead parents to disengage andultimately demonstrate detached parenting should be examined.In addition, studies should move beyond global child outcomessuch as problem behavior and examine the effect of detached par-enting on specific core developmental processes such as emotionexpression and emotion regulation.

Implications for Practice

Findings from the current study have important implications forpractice with young children and their families from low-incomebackgrounds. There is a critical need for early childhood programsto provide more than child-directed services and employ strategiesto enhance parental functioning. Specifically, programs could ad-dress parenting stress by offering interventions to improve parentalcoping as well as services that mitigate the stressors that parentsexperience. Moreover, parenting interventions could facilitate par-ents’ skills in sustaining their involvement and engagement as wellas supportiveness and stimulation in the context of their day-to-dayinteractions with their children. Such explicit interventions, with

a focus on reducing parenting stress and detachment as well aspromoting positive parenting behaviors, have the potential to de-crease early problem behavior and ultimately enhance children’slong-term development.

Similarly, this study has important implications for infantmental health practice. The overarching goal of infant mental healthintervention is to enhance parents’ capacity to interact with theirchildren in a positive, nurturing, sensitive, and stimulating manner(e.g., Leiberman & Van Horn, 2008). This approach to practice isgrounded in knowledge about if, when, and how parents respondto their young children, and what factors need to be addressedto improve their responsiveness. Typically, infant mental healthinterventionists assess parents’ engagement with their children inthe context of the parent–child relationship early in the therapeuticprocess, and work to increase the quantity and quality of parents’interactions with their children. Through this focus on parent–childinteraction within the parent–child relationship, early childhoodmental health programs have been found to enhance parental psy-chological functioning (e.g., Chaffin, Funderburk, Bard, Valle, &Gurwitch, 2011; Cicchetti, Rogosch, & Toth, 2006; Shaw, 2006).Thus, a priority should be placed on linking parents who have beenidentified as manifesting detachment with infant mental health ser-vices.

CONCLUSIONS

The current study suggests that detached parenting represents animportant parenting process to examine in its own right, whichshould be disentangled from other negative parenting processes.The evidence presented herein confirms findings from other stud-ies that demographic risk, including “household instability” fac-tors such as the number of moves and people residing in thehome, is related to detached parenting and adverse child out-comes. Contrary to expectations, infant neurodevelopmental riskstatus was not related to detached parenting or child outcomes.A particular contribution of the current study is that parent-ing stress has a more potent influence on detached parentingthan do specific demographic and infant developmental risk fac-tors. However, both parenting stress and detached parenting ledto toddler problem behavior. Early childhood and infant men-tal health programs targeted at high-risk families should includecareful attention to the factors that may contribute to detachedparenting, including parenting stress, as well as provide interven-tions designed to enhance parents’ engagement with their youngchildren.

REFERENCES

Achenbach, T., & Rescorla, L. (2000). Manual for the ASEBA preschoolforms and profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont.

Administration for Children and Families. (2002). Making a differencein the lives of infants and toddlers and their families: The impactsof Early Head Start. Washington, DC: Department of Health andHuman Services.

Infant Mental Health Journal DOI 10.1002/imhj. Published on behalf of the Michigan Association for Infant Mental Health.

540 • B. Jones Harden et al.

Arnold, D., O’Leary, S., Wolff, L., & Acker, M. (1993). The parentingscale: A measure of dysfunctional parenting in discipline situations.Psychological Assessment, 5, 137–144.

Aylward, G. (1995). The Bayley infant neurodevelopmental screener. SanAntonio, TX: Psychological Corporation.

Baillargeon, R., Normand, C., Seguin, J., Zoccolillo, M., Japel, C.,Perusse, D. et al. (2007). The evolution of problem and social com-petence behaviors during toddlerhood: A prospective population-based cohort survey. Infant Mental Health Journal, 28(1), 12–38.doi:10.1002/imhj.20120

Baker, B., Blacher, J., Crnic, K., & Edelbrock, C. (2002). Behavior prob-lems and parenting stress in families of three-year-old children withand without developmental delays. American Journal on Mental Re-tardation, 107(6), 433–444.

Barber, B. (Ed.). (2002). Intrusive parenting: How psychological controlaffects children and adolescents. Washington, DC: American Psy-chological Association.

Baumrind, D. (1989). Rearing competent children. In W. Damon (Ed.),Child development today and tomorrow (pp. 349–378). San Fran-cisco: Jossey-Bass.

Berlin, L., Brady-Smith, C., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2002). Links betweenchildbearing age and observed maternal behaviors with 14-month-olds in the Early Head Start Research and Evaluation Project. InfantMental Health Journal, 23(1–2), 104–129.

Blair, C., Granger, D., Kivlighan, K., Mills-Koonce, R., Willoughby, M.,Greenberg, M. et al. (2008). Maternal and child contributions to corti-sol response to emotional arousal in young children from low-income,rural communities. Developmental Psychology, 44(4), 1095–1109.

Bocknek, E., Brophy-Herb, H., & Banerjee, M. (2009). Effects of parentalsupportiveness on toddlers’ emotion regulation over the first threeyears of life in a low-income African American sample. Infant MentalHealth Journal, 30(5), 452–476.

Bocknek, E., Brophy-Herb, H., Fitzgerald, H., Burns-Jager, K., &Carolan, M. (2012). Maternal psychological absence and tod-dlers’ social-emotional development: Interpretations from the per-spective of boundary ambiguity theory. Family Process, 51(4),527–541.

Bornstein, M. (2002). Parenting infants. In M. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbookof parenting: Vol. 1. Children and parenting (pp. 3–43). Hillsdale,NJ: Erlbaum.

Brady-Smith, C., Brooks-Gunn, J., Tamis-LeMonda, C., Ispa, J., Fuligni,A., Chazan-Cohen, R., & Fine, M. (2013). Mother–infant interactionsin Early Head Start: A person-oriented within-ethnic group approach.Parenting: Science and Practice, 13(1), 27–43.

Briggs-Gowan, M., & Carter, A. (2006). The Brief Infant–Toddler Socialand Emotional Assessment (BITSEA). San Antonio, TX: Psycho-logical Corporation, Harcourt Assessment.

Briggs-Gowan, M., & Carter, A. (2008). Social-emotional screening statusin early childhood predicts elementary school outcomes. Pediatrics,121(5), 957–962.

Brown, S., Arnold, D., Dobbs, J., & Doctoroff, G. (2007). Parenting pre-dictors of relational aggression among Puerto Rican and European

American school-age children. Early Childhood Research Quarterly,22(1), 147–159.

Burchinal, M., Roberts, J., Zeisel, S., Hennon, E., & Hooper, S. (2006).Social risk and protective child, parenting, and child care factors inearly elementary school years. Parenting, 6, 79–113.

Burke, J., Pardini, D., & Loeber, R. (2008). Reciprocal relationshipsbetween parenting behavior and disruptive psychopathology fromchildhood through adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychol-ogy, 36, 679–692.

Burstein, M., Stanger, C., Kamon, J., & Dumenci, L. (2006). Par-ent psychopathology, parenting, and child internalizing problemsin substance-abusing families. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors,20(2), 97–106.

Campbell, S. (2006). Maladjustment in preschool children: A develop-mental psychopathology perspective. In K. McCartney & D. Phillips(Eds.), Blackwell handbook of early childhood development (pp.358–377). Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Campbell, S., Shaw, D., & Gilliom, M. (2000). Early externalizing be-havior problems: Toddlers and preschoolers at risk for later mal-adjustment. Development and Psychopathology, 12(3), 467–488.doi:10.1017/S0954579400003114

Chaffin, M., Funderburk, B., Bard, D., Valle, L., & Gurwitch, R. (2011). Acombined motivation and parent–child interaction therapy packagereduces child welfare recidivism in a randomized dismantling fieldtrial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79(1), 84–95.

Chang, M., Park, B., Singh, K., & Sung, Y. (2009). Parental involvement,parenting behaviors, and children’s cognitive development in low-income and minority families. Journal of Research in ChildhoodEducation, 23(3), 309–324.

Cicchetti, D., Rogosch, F.A., & Toth, S.L. (2006). Fostering secure attach-ment in infants in maltreating families through preventive interven-tions. Development and Psychopathology, 18(3), 623–649.

Cicchetti, D., & Valentino, K. (2006). An ecological transactional per-spective on child maltreatment: Failure of the average expectableenvironment and its influence upon child development. In D. Cic-chetti & D.J. Cohen (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology: Vol.3. Risk, disorder, and adaptation (2nd ed., pp. 129–201). New York:Wiley.

Clark, R. (1985). The Parent-Child Early Relational Assessment. Instru-ment and manual. Madison, WI: Department of Psychiatry, Univer-sity of Wisconsin.

Cole, P., Michel, M., & Teti, L. (1994). The development of emotionregulation and dysregulation: A clinical perspective. Monographs ofthe Society for Research in Child Development, 59, 2–3.

Collins, W.A., Maccoby, E., Steinberg, L., Heatherington, E.M., & Born-stein, M. (2000). Contemporary research on parenting: The case fornature and nurture. American Psychologist, 55(3), 218–232.

Conger, R., Wallace, L., Sun, Y., Simons, R., McLoyd, V., & Brody, G.(2002). Economic pressure in African American families: A replica-tion and extension of the family stress model. Developmental Psy-chology, 38(2), 179–193.

Coolahan, K., McWayne, C., Fantuzzo, J., & Grim, S. (2002). Validationof multidimensional assessment of parenting styles for low-income

Infant Mental Health Journal DOI 10.1002/imhj. Published on behalf of the Michigan Association for Infant Mental Health.

Detached Parenting • 541

African-American families with preschool children. Early ChildhoodResearch Quarterly, 17(3), 356–373.

Crnic, K., Gaze, C., & Goodman, C. (2005). Cumulative parenting stressacross the preschool period: Relations to maternal parenting andchild behavior at age 5. Infant and Child Development, 14(2), 117–132.

Dallaire, D.H., & Weinraub, M. (2005). The stability of parenting behav-iors over the first 6 years of life. Early Childhood Research Quarterly,20, 201–219.

Davidov, M., & Grusec, J. (2006). Untangling the links of parental re-sponsiveness to distress and warmth to child outcomes. Child Devel-opment, 77, 44–58.

Diego, M., Field, T., Jones, N., & Hernandez-Reif, M. (2006). Withdrawnand intrusive maternal interaction style and infant frontal EEG asym-metry shifts in infants of depressed and non-depressed mothers. InfantBehavior & Development, 29(2), 220–229.

Evans, G., & Wachs, T. (Eds.). (2010). Chaos and its influence on chil-dren’s development: An ecological perspective. Washington, DC:American Psychological Association.

Field, T., Diego, M., Hernandez-Reif, M., Schanberg, S., &, Kuhn, C.(2003). Depressed mothers who are “good interaction” partners ver-sus those who are withdrawn or intrusive. Infant Behavior & Devel-opment, 26, 238–252.

Field, T., Morrow, C., Healy, B., Foster, T., Adlestein, D., & Gold-stein, S. (1991). Mothers with zero Beck depression scores act more“depressed” with their infants. Development and Psychopathology,3(3), 253–262.

Forbes, D., Fletcher, S., Lockwood, E., O’Donnell, M., Creamer, M.,Bryant, R. et al. (2011). Requiring both avoidance and emotionalnumbing in DSM-V PTSD: Will it help? Journal of Affective Disor-ders, 130(3), 483–486.

Gershoff, E., Aber, J., Raver, C., & Lennon, M. (2007). Income is notenough: Incorporating material hardship into models of income asso-ciations with parenting and child development. Child Development,78(1), 70–95.

Gewirtz, A., DeGarmo, D., Plowman, E., August, G., & Realmuto, G.(2009). Parenting, parental mental health, and child functioning infamilies residing in supportive housing. American Journal of Or-thopsychiatry, 79(3), 336–347.

Goldberg, S., & DiVitto, B. (2002). Parenting children born preterm. InM. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting: Vol. 1. Children andparenting (2nd ed., pp. 329–354). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Goodman, S., & Brand, S. (2009). Infants of depressed mothers: Vulnera-bilities, risk factors, and protective factors for the later developmentof psychopathology. In C. Zeanah (Ed.), Handbook of infant mentalhealth (3rd ed., pp. 153–170). New York: Guilford Press.

Gravener, J., Rogosch, F., Oshri, A., Narayan, A., Cicchetti, D., & Toth, S.(2012). The relations among maternal depressive disorder, maternalexpressed emotion, and toddler behavior problems and attachment.Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40(5), 803–813.

Grolnik, W., & Farkas, M. (2002). Parenting and the development of chil-dren’s self-regulation. In M. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting:

Vol. 5. Practical issues in parenting (2nd ed., pp. 89–110). Mahwah,NJ: Erlbaum.

Hess, C., Papas, M., & Black, M. (2004). Use of the Bayley infant neu-rodevelopmental screener with an environmental risk group. Journalof Pediatric Psychology, 29(5), 321–330.

Hipwell, A., Keenan, K., Kasza, K., Loeber, R., Stouthamer-Loeber, M.,& Bean, T. (2008). Reciprocal influences between girls’ conductproblems and depression, and parental punishment and warmth: Asix year prospective analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology,36(5), 663–677.

Ispa, J., Fine, M., Halgunseth, L., Harper, S., Robinson, J., Boyce, L.et al. (2004). Maternal intrusiveness, maternal warmth, and mother–toddler relationship outcomes: Variations across low-income ethnicand acculturation groups. Child Development, 75(6), 1613–1631.

Jenkins, J., Rasbash, J., & O’Connor, T. (2003). The role of the sharedfamily context in differential parenting. Developmental Psychology,39(1), 99–113.

Jones Harden, B., & Duchene, M. (2011). Promoting infant mental healthin early childhood programs: Intervening with the parent-child dyad.In S. Summers & R. Chazan-Cohen (Eds.), Understanding earlychildhood mental health: A practical guide for professionals. Balti-more, MD: Brookes.

Karrass, J., & Walden, T. (2005). Effects of nurturing and non-nurturingcaregiving on child social initiatives: An experimental investigationof emotion as a mediator of social behavior. Social Development,14(4), 685–700.

Kim, H., Pears, K., Fisher, P., Connelly, C., & Landsverk, J. (2010).Trajectories of maternal harsh parenting in the first 3 years of life.Child Abuse & Neglect, 34(12), 897–906.

Kim, J. (2009). Type-specific intergenerational transmission of neglectfuland physically abusive parenting behaviors among young parents.Children and Youth Services Review, 31(7), 761–767.

Knutson, J.F., DeGarmo, D.S., Reid, J.B., & Koeppl, G. (2005). Care ne-glect, supervisory neglect and harsh parenting in the development ofchildren’s aggression: A replication and extension. Child Maltreat-ment, 10(2), 92–107.

Kochanska, G., Friesenborg, A E., Lange, L.A., & Martel, M.M. (2004).Personality processes and individual differences—Parents’ person-ality and infants’ temperament as contributors to their emerging rela-tionship. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86, 744–759.

Kohen, D., Leventhal, T., Dahinten, V.S., & McIntosh, C. (2008). Neigh-borhood disadvantage: Pathways of effects for young children. ChildDevelopment, 79(1), 156–169.

Leidy, M., Guerra, N., & Toro, R. (2010). Positive parenting, family cohe-sion, and child social competence among immigrant Latino families.Journal of Family Psychology, 24(3), 252–260.

Levendosky, A., & Graham-Bermann, S. (2000). Behavioral observationsof parenting in battered women. Journal of Family Psychology, 14(1),80–94.

Lieberman, A.F., & Van Horn, P. (2008). Psychotherapy with infants andyoung children: Repairing the effects of stress and trauma on earlyattachment. New York: Guilford Press.

Infant Mental Health Journal DOI 10.1002/imhj. Published on behalf of the Michigan Association for Infant Mental Health.

542 • B. Jones Harden et al.

Lipscomb, S., Leve, L., Harold, G., Neiderhiser, J., Shaw, D., Ge, X., &Reiss, D. (2011). Trajectories of parenting and child negative emo-tionality during infancy and toddlerhood: A longitudinal analysis.Child Development, 82(5), 1661–1675.

Magill-Evans, J., & Harrison, M. (2001). Parent–child interactions, par-enting stress, and developmental outcomes at 4 years. Children’sHealth Care, 30(2), 135–150.

Mahoney, J., Schweder, A., & Stattin, H. (2002). Structured after-schoolactivities as a moderator of depressed mood for adolescents with de-tached relations to their parents. Journal of Community Psychology,30(1), 69–86.

Malphurs, J.E., Raag, T., Field, T., Pickens, J., & Pelaez-Nogueras, M.(1996). Touch by intrusive and withdrawn mothers with depressivesymptoms. Early Development and Parenting, 5, 111–115.

Martin, C., Fisher, P., & Kim, H. (2012). Risk for maternal harsh parentingin high-risk families from birth to age three: Does ethnicity matter?Prevention Science, 13(1), 64–74.

Maupin, A., Brophy-Herb, H., Schiffman, R., & Bocknek, E. (2010). Low-income parental profiles of coping, resource adequacy, and publicassistance receipt: Links to parenting. Family Relations: An Interdis-ciplinary Journal of Applied Family Studies, 59(2), 180–194.

McGrath, M., & Sullivan, M. (2003). Testing proximal and distal protec-tive processes in preterm high-risk children. Issues in ComprehensivePediatric Nursing, 26, 59–76.

Mistry, R., Vandewater, E., Huston, A., & McLoyd, V. (2002). Eco-nomic well-being and children’s social adjustment: The role of familyprocess in an ethnically diverse low-income sample. Child Develop-ment, 73(3), 935–951.

Murray, L., Halligan, S., Goodyer, I., & Herbert, J. (2010). Disturbancesin early parenting of depressed mothers and cortisol secretion inoffspring: A preliminary study. Journal of Affective Disorders,122(3), 218–223.

Muthen, L., & Muthen, B. (2008). Mplus user’s guide (5th ed.). LosAngeles: Author.