Comparing voice-therapy and vocal-hygiene treatments in dysphonia using a limited multidimensional...

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

4 -

download

0

Transcript of Comparing voice-therapy and vocal-hygiene treatments in dysphonia using a limited multidimensional...

This article appeared in a journal published by Elsevier. The attachedcopy is furnished to the author for internal non-commercial researchand education use, including for instruction at the authors institution

and sharing with colleagues.

Other uses, including reproduction and distribution, or selling orlicensing copies, or posting to personal, institutional or third party

websites are prohibited.

In most cases authors are permitted to post their version of thearticle (e.g. in Word or Tex form) to their personal website orinstitutional repository. Authors requiring further information

regarding Elsevier’s archiving and manuscript policies areencouraged to visit:

http://www.elsevier.com/copyright

Author's personal copy

Comparing voice-therapy and vocal-hygiene treatments in dysphoniausing a limited multidimensional evaluation protocol

Marıa J. Rodrıguez-Parra a,*, Jose A. Adrian b, Juan C. Casado c

a Department of Personality, Psychological Evaluation and Treatment, University of Granada, Granada, Spainb Department of Personality, Psychological Evaluation and Treatment, University of Malaga, Malaga, Spainc Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Costa del Sol Hospital, Marbella, Malaga, Spain

1. Introduction

In recent years there have been several advances in the study of the physiopathology and diagnosis of voice disorders.Nonetheless, some forms of treatment have progressed somewhat less rapidly than might be desired. Important differencescan be observed in the evaluation (different protocols) and treatment (different therapeutic methods) for these disorders(Rodrıguez-Parra, Casado, Adrian, & Buiza, 2006; Speyer, 2008). Professionals use diverse (often lengthy) protocols,methodologies, instruments, techniques and criteria which complicate the follow-up of the participants, the reliability ofcriteria and the interchange of data.

Journal of Communication Disorders 44 (2011) 615–630

A R T I C L E I N F O

Article history:

Received 16 December 2010

Received in revised form 30 June 2011

Accepted 28 July 2011

Keywords:

Voice-therapy

Vocal-hygiene

Dysphonia

Effectiveness

Multidimensional protocol

A B S T R A C T

Purpose: This study evaluates the effectiveness of two different programs of voice-

treatment on a heterogeneous group of dysphonic speakers and the stability of therapeutic

progress for longterm follow-up post-treatment period, using a limited multidimensional

protocol of evaluation.

Method: Forty-two participants with voice disorders were randomly assigned to one of

two groups. Participants in group 1 received voice-therapy and participants in group 2

received a vocal-hygiene program. Vocal function was assessed before and after treatment.

Results: MANOVA analysis Pillai’s trace test shows significant pre–post immediate

differences between treatments in favor of direct-intervention. Repeated-measures

ANOVAs display significant within subjects main effect for follow-up period in the 8

measures considered. Interaction effects of group � time are also found in five out of the

eight continuous variables analyzed (3 aerodynamics-acoustic and 2 self-rating),

indicating differences between both treatments. Qualitative dimensions (perceptual,

laryngoscopic and spectrographic assessments) also support voice-therapy superiority.

Conclusions: Results of this study suggest superiority of a voice-therapy (direct treatment)

approach over a vocal-hygiene program (indirect treatment). This advantage is on the

majority of the 8 continuous variables analyzed (aerodynamics, acoustic, and self-rating),

including qualitative perceptual, laryngoscopic and spectrographic voice-dimensions. The

stability of changes is extended during a post-treatment follow-up period.

Learning outcomes: (1) The reader should distinguish the advantage using one type of

treatment or another in clinical contexts. (2) The reader must know the most important

direct techniques used in clinical treatment of voice disorders.

� 2011 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

* Corresponding author at: Departamento de Personalidad, Evaluacion y Tratamiento Psicologico, Facultad de Educacion y Humanidades, Calle El Greco,

10 (51002), Ceuta, Spain, Tel.: +34 639943192.

E-mail address: [email protected] (M.J. Rodrıguez-Parra).

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Journal of Communication Disorders

0021-9924/$ – see front matter � 2011 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.jcomdis.2011.07.003

Author's personal copy

Several studies have carried out survey-based research to determine just what procedures are used in routine clinicalpractice for the treatment of dysphonia with reference to duration, modality (group or individual) or assessment (Behrman,2004; Dunnet, MacKenzie, Sellars, Robinson, & Wilson, 1997; Larson & Mueller, 1991; Mueller & Larson, 1992; Rodrıguez-Parra et al., 2006). These studies highlight the lack of systematic criteria used in the application of distinct therapeutictechniques. This methodological shortfall is due to the absence of standardized evaluation, the absence of significantvariables to detect change, the lack of standard terminology and differences in the perception and description of the qualityof the voice and the assessment of severity (Kempster, Gerratt, Verdolini, Barkmeier-Kraemer, & Hillman, 2009). This is whyproposals for multidimensional evaluation (see Adrian, Casado, Rodrıguez-Parra, & Gonzalez, 2003; Dejonckere et al., 2001;Kotby, 2006; Ortiz, Costa, Spina, & Crespo, 2004; Ricci & Lucchini, 2002) have arisen in an attempt to standardize objectiveprocedures and provide diagnostic uniformity. We agree that voice evaluation is necessarily multidimensional because voiceproduction itself is a multidimensional construct. Thus, to assess whether a treatment is effective or not, demands amultidimensional approach.

Methodological problems encompass correct evaluation of the voice therapy effectiveness in clinical practice. Manystudies lack reliability, validity and sensitivity due to the research designs used or due to inadequate indicators oftherapeutic change (Biddle, Watson, Hooper, Lohr, & Sutton, 2002). Some key variables, such as course, duration andintensity of therapy, the number of individual versus group sessions, baseline assessment levels and the adaptation oftechniques and factors which evaluate its efficacy over follow-up are often neglected in voice research (Dunnet et al., 1997;Roy et al., 2001; Speyer, 2008).

The same heterogeneity in evaluation procedures is also observed in the treatment of voice disorders. Numerous studiessupport the positive effect of voice-therapy programs in the treatment of dysphonia (Adrian et al., 2003; Casper & Murry,2000; Gillivan-Murphy, Drinnan, O’Dwyer, Ridha, & Carding, 2006; Niebudek-Bogusz, Sznurowska-Przygocka, Fiszer, Kotyło,& Sinkiewicz, 2008; Speyer, 2008). By contrast, others studies report success by using exclusively indirect (vocal-hygiene)techniques (Bovo, Galceran, Petruccelli, & Hatzopoulos, 2007; Chan, 1994; Pasa, Oates, & Dacakis, 2007; Yun, Kim, & Son,2007), while several other studies point out the relative inadequacy of vocal-hygiene as an independent, stand-alone voicetreatment program, and promote the effectiveness of other alternative behavioral voice therapy programs (Niebudek-Bogusz et al., 2008; Roy et al., 2001, 2003). On the other hand, many papers on voice-therapy suggest a combination of directand indirect techniques for the treatment of dysphonias (Carding, Horsley, & Docherty, 1998; Holmberg, Hillman,Hammarberg, Sodersten, & Doyle, 2001; Morrison & Ramaje, 1996). There is a definitive lack of systemization in the criteriaused for the application of determined therapeutic techniques. At the same time, the opinions of many experts in this fieldtend to focus on reporting the benefits of the application of voice-therapy, although these reports tend also to use only one-dimensional assessment and do not provide necessary detailed description of the therapy itself (Pannbacker, 1998).

In summary, the current situation is characterized by a paucity of data necessary for the comparison of therapeutic resultsacross institutions (Dejonckere, 2002) which could determine the effectiveness of a clinical program in voice disorders.

In a previous study, Rodrıguez-Parra, Adrian, and Casado (2009) showed that a multidimensional voice-evaluation called‘‘Teatinos Protocol’’, consisting of a combination of quantitative measurements (acoustics, aerodynamics and a set of self-rating questionnaires) and qualitative measurements (laryngoscopic, spectrographic and perceptual measures) wassensitive in the diagnostic of dysphonia in clinical and speech-language-therapy contexts. Eight indicators were found toreflect alterations in vocal function. Three of them were aerodynamics: Maximum Phonation Time (MPT) /a/, Maximum

Exhalation Time (MET) /s/, Maximum Phonation Time during Connected Speech (MPTS), one was acoustics: Jitter percentage andother four were obtained from a self-rating clinical questionnaire: Vocal well being (WB), Self assessment of voice (SELF), Vocal-

hygiene (HYGIENE), Anxiety (ANX). Also Perceptual, Laryngoscopic and Spectrographic explorations were considered asvaluable dimensions in voice diagnosis. This set of basic measures made it possible to detect significant differences betweendysphonic participants and the control group. These data are congruent with other studies using samples in differentlanguages, which search for effective methodology in diagnosis, prognosis and post-treatment evaluation of voice pathology,by using a reduced number of tests and measures (i.e. Dejonckere et al., 2001; Ricci, 2003; Ricci & Lucchini, 2002; Wuytset al., 2000).

The aim of this study is to use a multidimensional, limited set of voice measures from the Teatinos Protocol (Rodrıguez-Parra et al., 2009) to analyze the effects of two treatments (direct vs. indirect techniques) on a group of dysphonicparticipants, including a post-treatment assessment follow-up period.

2. Method

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Hospital Costa del Sol of Marbella (Malaga, Spain).

2.1. Participants: exclusion–inclusion criteria

Candidates were excluded from this study if they:

� Had paralysis or cancer of the vocal folds.� Showed no interest in participating in therapy.� Were unable to attend regular sessions.

M.J. Rodrıguez-Parra et al. / Journal of Communication Disorders 44 (2011) 615–630616

Author's personal copy

� Were prescribed psychoactive medications.� Presented with some degree of hearing loss.

Forty-two people with dysphonia (39 women and three men) were enrolled in this study, all of whom completed all testsfrom the design protocol. No participant dropped out of therapy (100% level of adherence). The participants were aged between16 and 65 years, with a mean of 33.1 years (SD: 10.9). All the participants had attended the Otorhinolaryngology Unit at theHospital ‘Costa del Sol’ in Marbella (Spain), presenting with voice problems. A functional alteration or lesion in the larynx wasconsidered a requirement for participation in the program. In the present study, all of the participants (except one) presentedsome type of pathology in the vocal folds. An inadequate use of the voice combined with a series of triggering factors (stress,allergies and anxiety) or risk factors (professional voice use, alcohol, tobacco, defective respiration, exposure to dust or airconditioning, etc.) which can alter the quality of the voice thus exacerbating the voice problems. The types of pathologyconsidered in the current study were vocal nodules, polyps, angiomatous polyps, Reinke’s edema, and hypotonic dysphonia.

At a socio-professional level, nine subjects were employed in sales and customer service, eight worked in sanitation, eightwere homemakers, five were administrative assistants, three teachers, two professional singers, one a television announcer andone a beautician. Additionally, there were three students, one pensioner and one subject who had had various temporary jobs.

During the voice treatment period and the follow up-assessments, all the participants continued working and attendingto other daily obligations. The participants were informed that they were free to leave the study if they chose to do so,whenever they liked and they could receive the same voice treatment outside of the research context. The participantsattended the Ear, Nose and Throat (ENT) specialist service and were referred to the Voice Laboratory for evaluation andtreatment in order of arrival. The purpose of this first medical evaluation was the categorization and diagnosis of the lesion.All of the participants signed an informed consent form before taking part in this study.

2.2. Treatment groups

On their arrival at the Voice Laboratory, the participants were assigned randomly to one of two treatment-groups bymeans of a computer-generated list of random numbers. Depending on whether their number was even or odd, they wereassigned to the vocal therapy group or the vocal hygiene group. Randomization was carried out individually by thecoordinator of the study. He was blind to each participant’s clinical status prior to their voice assessment. The characteristicsof the voice-therapy and vocal-hygiene groups are summarized in Table 1.

� Voice-therapy group: 21 participants (18 women and 3 men), with an average age of 34.6 years (SD: 11.8; range: 16–65years) were given treatment based on voice-therapy (direct techniques).� Vocal-hygiene group: 21 participants (21 women), with an average age of 31.6 years (SD: 9.9; range: 17–62 years) were

given treatment based on a vocal-hygiene program (indirect techniques).

2.3. Treatment design and procedure

An ABAAA design was selected to compare two treatments (Voice-therapy vs. Vocal hygiene), which included threefollow-up post-treatment evaluations. All participants were initially evaluated with the shortened multidimensional

Table 1

Characteristics of the participants by group.

n Pathology Sex Age range Smokers Reflux

disease

Hormone

disorders

Voice-therapy group

17 Vocal nodules (2 patients with

fibrous nodules on VF)

, 16–53 2 smokers < 10 d

2 smokers >10 d

2 exsmokers > 3 y

1 exsmokers < 3 y

9 5

2 Angiomatous polyp < 37–43 1 smoker > 10 d 2 No

1 Angiomatous polyp + Reinke’s edema , 36 Exsmokers > 3 y Yes No

1 Hypotonic dysphonia < 65 Exsmokers > 3 y Yes No

Vocal-hygiene group

15 Vocal nodules (2 patients with

fibrous nodules on VF)

, 17–43 3 smokers > 10 d

2 smokers < 10 d

1 exsmoker > 3 y

5 4

1 Vocal nodule LVF , 27 No No No

2 Bilateral micronodules , 27–62 No No No

1 Hypotonic dysphonia , 29 No No No

1 Angiomatous polyp , 29 Smoker > 10 d No No

1 Polyp + nodule , 40 Smoker < 10 d No Yes

VF, vocal folds.

M.J. Rodrıguez-Parra et al. / Journal of Communication Disorders 44 (2011) 615–630 617

Author's personal copy

protocol ‘‘Teatinos’’ (Rodrıguez-Parra et al., 2009) to establish baseline measures. The protocol included differentdimensions: acoustics, spectrographic evaluation, aerodynamics, perceptual and laryngostroboscopic assessments and self-rating questionnaires.

The acoustic parameter (jitter %) was obtained through a sustained phonation of the vowel /a/, after a normal breath, formore or less 3 s at a comfortable pitch and loudness. The microphone was situated at a standard distance of 12–15 cm fromthe lips and was directed towards the mouth at an angle of approximately 30–458. The voice signal was directly entered,recorded and digitized (sampling rate 22 kHz) using a 600-V AIWA microphone, a Pentium-class computer and specificsoftware (Multi-Speech 3700, KAY Elemetrics Corp., Lincoln Park, NJ). Each subject was recorded individually, in astandardized way, always in the morning, in a suitable room isolated from potential variables which might interfere with theassessment session, such that all the samples obtained were comparable. The spectrographic evaluation was undertaken onthe same vocal sample as that used in the acoustic analysis. A narrow-band spectrogram (1.024 points, 15.77 Hz filterbandwidth) was used. The rating system was based on Titze’s theory (Titze, 1995) cited elsewhere by other authors(Behrman, 2004; Shrivastav, 2005). Titze classifies the acoustic parameters into three types. We have considered sixsubtypes to facilitate visual evaluations of spectrograms. Thus, the resulting spectrogram was classified into one of sevenestablished categories: normal; type 1: low-intensity harmonics; type 2: noise; type 3: harmonics and noise both with lowintensity; type 4: subharmonics; type 5: subharmonics with low-intensity harmonics; type 6: subharmonics, noise withlow-intensity harmonics.

The aerodynamics measurements were:

(1) MPT /a/: the participant was placed in a standing position with their arms dangling loosely by the side of the body. He orshe was asked to take a deep breath and then hold the vowel /a/for as long as possible with a comfortable and natural toneand intensity. Three measures were taken with an interval of 2–3 min between them and the measure of the greatestduration was annotated.

(2) MET /s/: in the same posture as the previous test, the participant was asked to maintain the mute fricative consonant /s/for as long as possible after a deep breath, such that the air is expelled slowly and softly.

(3) MPTS: standing with their arms loosely held the side of the body, the participant was asked to take a deep breath andthen count out loud for as long as possible.

The perceptual exploration was completed with GRBAS scale (Hirano, 1981); each scale item was rated from 0 (normal)up to 3 (severe deviance in voice quality). In the Laryngostroboscopic exploration, the parameters and categories were:amplitude: normal (1)/inadequate (2); glottal closure: complete (1)/incomplete (2); mucosal wave: normal (1)/shaking (2);periodicity: yes (1)/no (2); symmetry: yes (1)/no (2) and ventricular folds: yes (2)/no (1). The instruments used in this type ofassessment were Wolf Telescopic laryngoscope of 708 (RichardWolf, Germany), Camera CCD in color CD5131 (FiegertEndotech, Germany), Stroboscopic with cool light source (Richard Wolf 5012, Germany) and a Sony Trinitron Stereo 1300color TV monitor, model KV 1380R. The self-rating questionnaires consisted of 37 questions, each question requiring one ofthree possible responses (Not at all, A little, A lot): (a) WB: this considers the functional impact of the voice disorder on theindividual who suffers with it; (b) SELF: the participant rates their own voice quality; (c) HYGIENE: about the participant’svocals habits; (d) ANX: degree of anxiety and stress experienced by the participant in daily life. Additionally, history andclinical backgrounds, hormonal factors, oral contraceptives and smoking habits were assessed.

The intervention programs were initiated after the first assessment (stage A) was completed. After finishing thetreatment (stage B), each participant was again assessed with the same protocol (post-1). Four weeks following post-1, allthe participants were reviewed and re-assessed (post-2), under the same conditions as the initial assessment. Finally, twelveweeks after post-2 (four months after finishing the treatment), all participants were given a final follow-up assessment(post-3).

The laryngostroboscopic, perceptual, acoustic and spectrographic assessments were completed by an ENT specialist(blinded to the type of treatment received by each participant) and by the speech-language pathologist (who did not knowthe assessment results of the participants). A psychologist and the speech-language pathologist (blinded to theotorhinolaryngological diagnosis) treating the participant administered the self-rating questionnaires and the aerodynamic/acoustic assessments.

2.4. Voice clinician training

The therapeutic staff was formed of five specialists in Malaga (Spain) who volunteered to apply the treatment in thestudy. All held a degree in Speech-Language pathology from the University of Malaga and had experience in the treatment ofvoice disorders. The criterion to be established in training the clinicians was to achieve a uniform implementation of vocaltreatments (direct and indirect) to ensure consistency in the clinical performance. All therapists took part in a trainingsession which consisted of a complete explanation of the objectives of the study and instruction on the principle aspects ofvocal therapy. The session lasted no more than 2 h and it was conducted by the speech-language pathologist.

The protocol used in the voice-therapy was based on the principle components from existing programs for vocaltreatment found in the current scientific literature (Colton & Casper, 1996; Holmberg et al., 2001; Morrison & Ramaje, 1996).Each speech-language pathologist was presented with examples of the voice production and projection exercises and

M.J. Rodrıguez-Parra et al. / Journal of Communication Disorders 44 (2011) 615–630618

Author's personal copy

descriptions of the most important characteristics of the therapeutic protocol. The rest of the meetings with the speech-language pathologist group consisted of clinical supervision sessions about applying the methods to the participants in thesample. In total, each therapist received 6 clinical supervision sessions during the course the treatment, in addition to thetraining session.

2.5. Description of therapy programs

2.5.1. Voice-therapy

Voice-therapy consisted of the five phases traditionally considered to be necessary to modify defective vocal technique(Andrews & Summers, 2002; Colton & Casper, 1996; Morrison & Ramaje, 1996). The exercises used in the treatment designhave their origins in behavioral approximation and are commonly applied in current clinical practice (Casper, 2001;Holmberg, Doyle, Perkell, Hammarberg, & Hillman, 2003; Holmberg et al., 2001). They consisted of five phases: basicinformation and counseling, relaxation, breathing, production and placement and carryover. An example of the prototypicvoice rehabilitation in clinical speech-language therapy can be seen in some reports (e.g. Holmberg et al., 2001, 2003;Rodrıguez-Parra et al., 2009). The duration of each phase and the selection of exercises for the vocal emission section variedas a function of the needs of each subject, their response to treatment and the type of dysphonia.

The rehabilitation sessions took place in the Speech-therapy Room at the Hospital Costa del Sol (Marbella, Spain), in themorning. The total number of sessions per participant was 24, conducted over a period of 12 weeks. In general, eachparticipant received two sessions per week. If, due to illness, scheduling difficulties or other commitments the participantreceived only one session in any one week, the treatment period was extended in order to complete the total of 24sessions. Each session lasted approximately 45 min. At the beginning of each session, the previous session was brieflyreviewed. At the close of the session, the speech-language pathologist and participant summarized all the newinformation given.

The participants were instructed to practise the techniques and exercises at home (15 min, twice daily). All treatmentsessions consisted of 5 target parameters: basic information and counseling, relaxation, breathing, emission and placement,and carryover. All participants completed all aspects of the treatment. No participants dropped out of therapy.

Basic information and counseling: Each participant was given a series of recommendations for vocal hygiene, which theywere instructed to follow over the course of the treatment.

Relaxation (5–15 m, depending on participant characteristics): Techniques included massages of affected areas, theelimination of rigid postures or cervical muscular tension and/or a brief adaptation of Jacobson’s progressive relaxation,generalized (whole body) or localized (laryngeal and adjacent areas). Relaxation work was done both on foot and seated.

Breathing (5–10 m, depending on stage of therapy): Training in breathing was directed at two specific areas: (1)facilitation of relaxed breathing, eliminating muscular rigidity, and (2) identification and subsequent elimination ofbehaviors which reflect the inadequate management of air in verbal production. To start, the participant was trained indiaphragmatic breathing, beginning with breathing exercises in a supine position and in silence. Progressively more complexvocal tasks (e.g., conversation) were incorporated in different positions (e.g., seated, on foot, walking). The management ofthe phonic air supply was modified by exercises developing respiratory-phonic coordination, avoiding the excessive use ofair which might produce a choking sensation.

Emission and placement (15–25 m, depending on stage of therapy): This phase was made up of direct techniques whichactively incorporated the muscles of the phonic apparatus and other muscles, with the objective of correctly using thephonic-articulatory organs to produce clear and projected speech. It aimed to reduce the rhythm of speech (in cases wherethis was deemed necessary) and to locate the voice at the most adequate points in the voice box, such that the ideal tensionbetween the oropharyngeal and laryngeal musculature would project effective and fluid sound with minimal effort. In linewith the current clinical practices (Boone & McFarlane, 2000; Branski, Murry, & Rosen 2000; Colton & Casper, 1996; Wilson,1987) six basic direct techniques were used: Yawn-sigh method; chewing technique, pitch variation and control;elimination and reduction of loudness; elimination of glottal attack and voice ‘‘placing’’. The choice, duration and order ofapplication of these techniques depended on the severity of the problem, the degree of understanding on the part of theparticipant and response to the applied techniques (Colton & Casper, 1996; Mathieson, 2001). In order to ensure that theobjectives of the therapy were achieved, the clinician explained and demonstrated the techniques repeatedly (at least twice)until the participant was able to perform them correctly.

Carryover (5–10 m, depending on stage of therapy): This phase consisted of transferring new learning of vocal behavior toreal-life situations. The participants practiced vocal exercises which varied according to the requirements of their jobs andtheir daily life (for example: singing or talking for an extended period).

2.5.2. Vocal hygiene

The voice hygiene program followed guidelines for a program previously described as successful in interventions withteachers described by Chan (1994). Session lasted approximately 60 min, took place in the speech pathology room in theHospital Costa del Sol, and was structured in the following way (see Appendix A):

(1) Explanation of normal voice mechanisms and laryngeal pathologies.(2) Vocal abuse and its consequences were explained.

M.J. Rodrıguez-Parra et al. / Journal of Communication Disorders 44 (2011) 615–630 619

Author's personal copy

(3) Correct (healthy) use of the voice.(4) Personalized strategies.

The participants were to agree to and to commit to making the discussed changes. After 6 weeks, the participantsreturned and commented on their ability to carry out the changes and on the progress observed. Each participant was given adocument describing the basic principles of vocal-hygiene as a reminder.

2.6. Statistics

The acoustic (jitter), aerodynamic (MPT, MET, MPTS) and self-rating questionnaires (WB, SELF, HYGIENE and ANX)measures were quantitative (continuous) and were analyzed via parametric tests. The perceptual, laryngoscopic andspectrographic dimensions were qualitative and were analyzed in terms of the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U-test andpercentages. The means and standard deviations of the raw data or scores obtained for each of the subjects were used foranalysis of the continuous variables in the parametric tests.

Two MANOVAs for correlated data were used to compare the two groups at pre- and post-treatment stages. One Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare qualitative variables at pre-treatment baseline stage. Repeated measures ANOVAs andANCOVA were used to analyze the potential effects and the interaction effects of the therapies at different stages of theevaluation (while taking into account the variance of the treatment groups).

The statistical package SPSS-15 was used on a Microsoft Windows XP Professional platform for the organization,administration and treatment of data. The analysis of the qualitative variables in this study was completed by examiningfrequencies of subject behaviors, expressed as percentages of the total sample.

3. Results

3.1. Differences between the voice-therapy and the vocal-hygiene groups at pre-treatment-baseline

3.1.1. Pre-treatment analysis of the continuous variables

A MANOVA analyses Pillai’s trace test (F(8,33) = 1.07, p > .40) did not find significant group differences in continuousvariables at the pre-treatment stage. Between groups comparisons did not show any significant differences either. Thisindicates that all participants began the intervention sessions with similar levels of performance on the continuous variablesassessed.

3.1.2. Pre-treatment analyses of qualitative variables

The dysphonic subjects assigned to voice-therapy (100%) were evenly distributed between values 1 and 2 (mild andmoderate) for the variables Dysphonia Grade and Rough. For the variable asthenic voice, more than half of the subjects in voice-therapy and vocal-hygiene (66.7% and 52.4%, respectively) obtained a value of 1. The majority of the voice-therapy group wasfound at level 2 of the variable breathy voice (38%) and at level 1 of the variable strained voice (42.9%). The majority of the vocal-hygiene group (57.1%) sat at level 1 of the variable breathy voice and at level 2 of the variable strained voice (52.4%).

Analysis of the spectrographic results at baseline showed that most subjects in voice-therapy (42.8%) fell within aspectrogram type characterized as Harmonics and Noise both with low intensity (type 3). The same proportion of subjects inthe vocal-hygiene group fell within a spectrogram characterized as Low-Intensity Harmonics (type 1). The two groups weresimilar in terms of perceptual, laryngostroboscopic and spectrographic characteristics (Tables 2–6).

The Mann–Whitney U test on pre-treatment qualitative variables showed no-differences between groups in perceptualvariables: Grade (U = 183.500, p = .28), Rough (U = 215.500, p = .89), Asthenic (U = 210.500, p = .77), Breathy (U = 209.500,p = .77), and Strained (U = 168.500, p = .16), and in Laryngograph-Spectrographic evaluation: Amplitude (U = 199.500, p = .15),Glottic Closure (U = 199.500, p = .15), Mucosal wave (U = 210.000, p = .68), Periodicity (U = 220.500, p = 1.00), Symmetry

(U = 210.000, p = .64), and Spectrographic characteristics (U = 189.000, p = .38).

3.2. Differences between the voice-therapy and vocal-hygiene groups at post-treatment (pre vs. post-1, post-2 and post-3)

3.2.1. Post-treatment analyses of the continuous variables

A MANOVA analysis Pillai’s trace test (F(8,33) = 6.45, p < .000) showed significant group differences in continuousvariables at post-1 stage. Between groups comparisons showed significant differences pre vs. post-1 on 5 of the 8 parametersassessed at baseline (see Table 7). These results indicated a significant effect of treatment on some of the parametersassessed at post-1 stage.

Repeated-measures ANOVAs were applied to all the variance of group (voice-therapy and vocal hygiene) for testing longterm intra-subjects effects, during a post-treatment follow-up period and the interaction effect (group of treatment vs. timeof treatment), considering group main effect (vocal-hygiene vs. voice-therapy) and time main effects (pre, post-1, post-2, andpost-3).

The results showed a significant within-subjects principle effect for time of treatment in 8/8 variables analyzed:Maximum Phonation Time F(3,37) = 4.2, p = .012, h2 = .25, Maximum Exhalation Time F(3,37) = 5.52, p < .004, h2 = .31, Maximum

M.J. Rodrıguez-Parra et al. / Journal of Communication Disorders 44 (2011) 615–630620

Author's personal copy

Ta

ble

2

Vo

ice

-th

era

py

gro

up

resu

lts

inp

erc

ep

tua

lv

ari

ab

les

for

ea

chst

ag

eo

ftr

ea

tme

nt.

Nu

mb

er

of

pa

rtic

ipa

nts

(%)

PR

EP

OS

T-1

PO

ST

-2P

OS

T-3

01

23

01

23

01

23

01

23

Gra

de

–1

0(4

7.6

)1

1(5

2.4

)–

7(3

3.4

)1

2(5

7.1

)2

(9.5

)–

8(3

8)

9(4

2.9

)4

(19

.1)

–1

3(6

1.9

5)

6(2

8.5

5)

2(9

.5)

–

Ro

ug

h–

11

(52

.4)

10

(47

.6)

–9

(42

.9)

11

(52

.4)

1(4

.7)

–7

(33

.4)

12

(57

.1)

2(9

.5)

–1

4(6

6.7

)5

(23

.8)

2(9

.5)

–

Bre

ath

y7

(33

.4)

6(2

8.6

)8

(38

)–

17

(80

.9)

4(1

9.1

)–

–1

9(9

0.5

)2

(9.5

)–

–1

6(7

6)

3(1

4.5

)2

(9.5

)–

Ast

he

nic

5(2

3.8

)1

4(6

6.7

)2

(9.5

)–

18

(85

.6)

2(9

.5)

1(4

.7)

–1

9(9

0.5

)2

(9.5

)–

–1

8(8

5.5

)3

(14

.5)

––

Str

ain

ed

6(2

8.5

5)

9(4

2.9

)6

(28

.55

)–

11

(52

.4)

9(4

2.9

)1

(4.7

)–

12

(57

.1)

5(2

3.8

)4

(19

.1)

–1

4(6

6.7

)5

(23

.8)

2(9

.5)

–

M.J. Rodrıguez-Parra et al. / Journal of Communication Disorders 44 (2011) 615–630 621

Author's personal copy

Ta

ble

3

Vo

cal

hy

gie

ne

gro

up

resu

lts

inp

erc

ep

tua

lv

ari

ab

les

for

ea

chst

ag

eo

ftr

ea

tme

nt.

Nu

mb

er

of

pa

rtic

ipa

nts

(%)

PR

EP

OS

T-1

PO

ST

-2P

OS

T-3

01

23

01

23

01

23

01

23

Gra

de

–7

(33

.4)

13

(61

.9)

1(4

.7)

1(4

.7)

12

(57

.15

)7

(33

.45

)1

(4.7

)2

(9.5

)1

4(6

6.7

)5

(23

.8)

–8

(40

)7

(35

)4

(20

)1

(5)

Ro

ug

h1

(4.7

)9

(42

.9)

11

(52

.4)

–1

(4.7

)1

3(6

1.9

)7

(33

.4)

–2

(9.5

)1

6(7

6)

3(1

4.5

)–

8(4

0)

10

(50

)2

(10

)–

Bre

ath

y5

(23

.8)

12

(57

.1)

3(1

4.4

)1

(4.7

)1

3(6

1.9

5)

5(2

3.8

5)

2(9

.5)

1(4

.7)

14

(66

.7)

5(2

3.8

)2

(9.5

)–

14

(70

)2

(10

)3

(15

)1

(5)

Ast

he

nic

7(3

3.4

)1

1(5

2.4

)2

(9.5

)1

(4.7

)1

5(7

1.5

)4

(19

.1)

1(4

.7)

1(4

.7)

17

(80

.9)

2(9

.55

)2

(9.5

5)

–1

5(7

5)

1(5

)3

(15

)1

(5)

Str

ain

ed

4(1

9.1

)6

(28

.5)

11

(52

.4)

–6

(28

.55

)1

0(4

7.6

)5

(23

.85

)–

9(4

2.9

)1

1(5

2.4

)1

(4.7

)–

9(4

5)

9(4

5)

2(1

0)

–

M.J. Rodrıguez-Parra et al. / Journal of Communication Disorders 44 (2011) 615–630622

Author's personal copy

Phonation Time during Connect Speech F(3,37) = 6.84, p = .001, h2 = .36, Jitter F(3,37) = 4.27, p = .011, h2 = .26, Self-voice

Assessment F(3,37) = 40.24, p = .000, h2 = .76, Vocal Well-Being F(3,37) = 28.57, p = .000, h2 = .7, Vocal-hygiene F(3,37) = 30.22,p = .000, h2 = .71, and Anxiety F(3,37) = 12.43, p = .000, h2 = .50.

The interaction effects were also significant in five out of the eight variables analyzed: Maximum Phonation Time

F(3,37) = 10.73, p = .000, h2 = .46, Maximum Exhalation Time F(3,37) = 5.18, p < .005, h2 = .30, Maximum Phonation Time during

Connect Speech F(3,37) = 4.85, p = .006, h2 = .32, F(3,37) = 5.9, p = .002, h2 = .28, Self-voice Assessment F(3,37) = 5.9, p = .002,h2 = .32, and Vocal Well-Being F(3,37) = 6.49, p = .001, h2 = .34. Moreover, the variable Anxiety also showed a tendency towardssignificance: F(3,37) = 2.80, p = .053, h2 = .18.

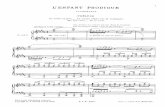

Fig. 1 outlines the differences between voice-therapy and vocal-hygiene groups in aerodynamic and acoustic variablesalong to the stages of this study, showing interactions group � time of treatment to Maximum Phonation Time, Maximum

Table 4

Voice-therapy group results in laryngograph ratings for each stage of treatment.

Number of participants (%)

PRE POST-1 POST-2 POST-3

Amplitude Normal Inadequate Normal Inadequate Normal Inadequate Normal Inadequate

0 21(100) 12(57) 9(43) 12(57) 9(43) 13(62) 8(38)

Glottal closure Complete Incomplete Complete Incomplete Complete Incomplete Complete Incomplete

0 21(100) 10(48) 11(52) 11(52) 10(48) 13(62) 8(38)

Mucosal wave Normal Shaking Normal Shaking Normal Shaking Normal Shaking

17(81) 4(19) 18(86) 3(14) 18(86) 3(14) 18(86) 3(14)

Periodicity YES NO YES NO YES NO YES NO

19(91) 2(9) 20(95) 1(5) 20(95) 1(5) 20(95) 1(5)

Symmetry YES NO YES NO YES NO YES NO

18(86) 3(14) 20(95) 1(5) 20(95) 1(5) 20(95) 1(5)

Ventricular folds YES NO YES NO YES NO YES NO

5(24) 16(76) 0 21(100) 0 21(100) 1(5) 20(95)

Table 5

Vocal-hygiene group results in Laryngograph ratings for each stage of treatment.

Number of participants (%)

PRE POST-1 POST-2 POST-3

Amplitude Normal Inadequate Normal Inadequate Normal Inadequate Normal Inadequate

2(9) 19(91) 4(19) 17(81) 4(19) 17(81) 4(20) 16(80)

Glottal closure Complete Incomplete Complete Incomplete Complete Incomplete Complete Incomplete

0 21(100) 2(9) 19(91) 2(9) 19(91) 2(10) 18(90)

Mucosal wave Normal Shaking Normal Shaking Normal Shaking Normal Shaking

18(86) 3(14) 18(86) 3(14) 18(86) 3(14) 17(85) 3(15)

Periodicity YES NO YES NO YES NO YES NO

19(91) 2(9) 20(95) 1(5) 20(95) 1(5) 20(100) 0

Symmetry YES NO YES NO YES NO YES NO

19(91) 2(9) 20(95) 1(5) 20(95) 1(5) 19(95) 1(5)

Ventricular folds YES NO YES NO YES NO YES NO

0 21(100) 0 21(100) 0 21(100) 1(5) 19(95)

Table 6

Spectrographic characteristics of voice-therapy group and vocal-hygiene group for each stage of treatment.

Number of participants in spectrographic evaluation with vowel /a/ (%)

PRE POST-1 POST-2 POST-3

V.T. V.H. V.T. V.H. V.T. V.H. V.T. V.H.

Normal – 3 (14.3) 8 (38.1) 5 (23.8) 10 (47.6) 9 (42.8) 12 (57.1) 9 (45)

Type 1 3 (14.3) 9 (42.8) 9 (42.8) 12 (57.1) 9 (42.8) 9 (42.8) 6 (28.5) 6 (30)

Type 2 8 (38.1) 2 (9.5) 3 (14.3) 1 (4.8) 1 (4.8) 1 (4.8) 1 (4.8) 2 (10)

Type 3 9 (42.8) 3 (14.3) 1 (4.8) 2 (9.5) 1 (4.8) 1 (4.8) 2 (9.5) 1 (5)

Type 4 – – – – – – – 1 (5)

Type 5 1 (4.8) 1 (4.8) – – – – – –

Type 6 – 3(14.3) – 1 (4.8) – 1 (4.8) – 1 (5)

Total 21 (100) 21 (100) 21 (100) 21 (100) 21 (100) 21 (100) 21 (100) 20 (100)

Normal: without alterations (no noise and no subharmonics); Type 1: low intensity harmonics; Type 2: noise; Type 3: harmonics and noise both with low

intensity; Type 4: subharmonics; Type 5: subharmonics with low intensity harmonic; Type 6: subharmonic, noise with low intensity harmonics.

M.J. Rodrıguez-Parra et al. / Journal of Communication Disorders 44 (2011) 615–630 623

Author's personal copy

Exhalation Time, and Maximum Phonation Time during Connect Speech on post-treatment follow-up data. The effect of voice-therapy group differed depending on the vocal-hygiene group performance. It was found that those participants whofollowed voice-therapy treatment achieved an improvement on the performance in these variables. Conversely, hygienegroup tended to decrease or show no change their performance in respect to pre-treatment stage.

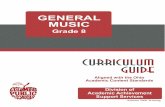

Fig. 2 represents the differences between voice-therapy and vocal-hygiene groups on self-rating variables. Significantinteraction for Self-voice Assessment showed that participants in voice-therapy group reported better improvement aftertreatment than participants from vocal-hygiene group (see Fig. 2, a low score is better). The interaction for Vocal Well-Being

also supported greater positive effects of voice-therapy over vocal-hygiene in the post-treatment follow-up period (see Fig. 2upper-right, a high score is better).

A focused ANCOVA using the baseline as the co-variable and post-3 (review-assessment four-months followingtreatment) as the dependent measure was used to better understand and refine the reach of these data. The result showed asignificant effect on 4/8 variables analyzed (two aerodynamics, and 2 self-rating variables): Maximum Time Phonation,t = 3.26, p = .002, h2 = .22; estimated mean at post-3 is M = 14.31, SD = .85 for voice-therapy group and M = 10.27, SD = .87 for

Table 7

Mean, multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) results comparing the voice therapy group and the vocal hygiene group in post-treatment stage.

Parameter Voice therapy group Vocal hygiene group MANOVA

M (SD) M (SD) F p

MPT 12.76 (4.25) 10.62 (3.95) 2.86 0.099

MET 23.67 (9.41) 18.42 (5.52) 4.84 0.034*

MPTS 12.86 (3.42) 10.67 (3.21) 4.57 0.039*

JITTER 1.07 (0.69) 2.79 (4.16) 3.45 0.071

WELL-BEING 6.48 (1.40) 4.09 (1.92) 20.37 0.000*

SELF-VOICE 2.62 (2.08) 6.57 (3.43) 21.06 0.000*

HYGIENE 18.05 (2.11) 15.38(3.56) 8.73 0.005*

ANXIETY 2.76 (1.81) 3.48 (1.99) 1.48 0.231* p < 0.04.

* Control group data from Rodríguez-Parra et al. (2009)

Post-3Post-2Post-1Pre-treatment0

10

20

30

Voice therapyHygiene vocalControl Group*

Maximum Phonation Time (MPT)

Stages

seco

nd

s

Post-3Post-2Post-1Pre-treatment0

10

20

30

Voice therapy Vocal HygieneControl Group*

Maximum phonation time during connect speech (MPTS)

Stages

seco

nd

s

Post-3Post-2Post-1Pre-treatment10

20

30

40

Voice therapyVocal Hygiene Control Group*

Maximum Exhalation Time (MET)

Stages

seco

nd

s

Post-3Post-2Post-1Pre-treatment0

1

2

3

Voice therapy Vocal HygieneControl Group*

Jitter

Stages

%

Fig. 1. Voice-therapy group, vocal-hygiene group and control group results for each stage of treatment in the aerodynamic and acoustic variables.

M.J. Rodrıguez-Parra et al. / Journal of Communication Disorders 44 (2011) 615–630624

Author's personal copy

vocal-hygiene group, Maximum Exhalation Time, t = 2.66, p = .011, h2 = .16, M = 25.82, SD = 1.5 for voice-therapy group andM = 20.04 SD = 1.53 for vocal-hygiene group, Vocal Well-Being, t = 4.12, p = .000, h2 = .31, M = 6.07, SD = .38 for voice-therapygroup and M = 3.83, SD = .39 for vocal-hygiene group; and Self-voice Assessment, t = �4.12, p = .000, h2 = .31, M = 2.22, SD = .65for voice-therapy group and M = 6.06, SD = .66 for vocal-hygiene group.

3.2.2. Post-treatment analyses of qualitative variables

An analysis of the results obtained in the perceptual evaluation following voice-therapy treatment shows an increase ofthe number of subjects with a score of 0 (normal voice) on the five assessed perceptual variables (Grade, Rough, Asthenic,Breathy and Strained). There were no participants with the characteristics of a normal voice at the pre-treatment assessment,on two of the five perceptual variables (Grade and Rough) as is shown in Table 2; yet, following voice-therapy (post-1), 7subjects (33.4%) presented a score of 0 on Dysphonia Grade and 9 subjects (42.9%) scored 0 on Rough voice. On the remainingperceptual variables (Asthenic, Breathy and Strained), there was a decrease of the number of participants who presented withvoices that were considered moderately Asthenic, Breathy and Strained (score 2), progressing towards scores indicatingdecreased severity (score 1).

The results obtained by the voice-therapy group in assessments carried out at one month (post-2) and four months afterthe end of treatment (post-3) were analyzed in the same way. Participants not only maintained the improvement achievedwith respect to baseline but actually improved over time on most of the studied variables such that, at the final follow-upassessment (post-3), more than 60% of the group achieved scores of 0 on several measures of voice quality, indicating anormal voice. When compared to their baseline condition, some participants in the vocal hygiene group maintained theimprovements that had been observed at the post-treatment stage while other participants continued to progress towards aqualitatively normal voice from a perceptual perspective. This progress, however, was less than the progress registered byparticipants in the voice-therapy group. Tables 2 and 3 show that in post-2, the percentage of participants with score of 1 and2 is superior on all variables in the voice hygiene group. Nonetheless, the percentage of participants established as having a

* Control group data from Rodríguez-Parra et al. (2009)

Post-3Post-2Post-1Pre-treatment2

3

4

5

6

7

Voice therapy

Vocal Hygiene

Control Group*

Vocal well-being

Stages

Vo

cal w

ell-

bei

ng

leve

l

Post-3Post-2Post-1Pre-treatment0

2

4

6

8

10

12

Voice therapy

Vocal Hygiene

Control Group*

Self-voice assessment

Stages

Sel

f-vo

ice

asse

ssm

ent

leve

l

Post-3Post-2Post-1Pre-treatment2

3

4

5

Voice therapy

Vocal Hygiene

Control Group*

Anxiety

Stages

An

xiet

y &

str

ess

leve

l

Post-3Post-2Post-1Pre-treatment10

12

14

16

18

20

Voice therapy grouVocal HygieneControl Group*

Vocal hygiene

Stages

Vo

cal h

ygie

ne

leve

l

Fig. 2. Voice-therapy group, vocal-hygiene group and control group results for each stage of treatment in self-rating variables (questionnaires).

M.J. Rodrıguez-Parra et al. / Journal of Communication Disorders 44 (2011) 615–630 625

Author's personal copy

normal voice (score of 0) was superior in the voice-therapy group on all variables. The final review-assessment (post-3) alsoshowed greater percentages of scores of 1, 2 and 3 in the vocal-hygiene group and more than 70% of the subjects in that groupwere shown to have a normal voice (score of 0) on asthenic voice (n = 15) and breathy voice (n = 14). It must be noted that evenat baseline some participants were given scores of 0 on asthenic voice (n = 7) and breathy voice (n = 5).

The data presented in Tables 4 and 5 show how the laryngostroboscopic assessments, which had been shown to bedisturbed at pre-treatment stage, had improved following treatment. This improvement is much more notable in the voice-therapy group. At follow-up assessments post-2 and post-3, the vocal-treatment group maintained the improvement theyhad achieved compared to baseline measures in 6 of the studied variables as well as in Amplitude and Glottal Closure. Thesetwo continued to show improvement over time until the post-3 assessment. Only one subject demonstrated a relapse uponfinal assessment of the parameter Ventricular folds. An analysis of the follow-up assessments of the vocal-hygiene group alsoshowed stability (not a further increase) of the scarce changes produced by the treatment on the parameters shown to bedisturbed at the initial assessment.

From the data extracted by laryngostroboscopic exploration, 10 of the 21 participants treated with voice-therapyobtained a final diagnosis of normal, and the remaining 11 experienced an important clinical improvement, albeit notcomplete. In the vocal-hygiene group, the 21 participants showed persisting laryngeal lesions.

At post-1, 8 participants (38.1%) from the voice-therapy group obtained a normal spectrogram (no Noise and no Sub-harmonics). Two participants in the vocal-hygiene group (3 of the 5 participants had a normal spectrogram at baseline)obtained a normal spectrogram at follow-up (see Table 6). The increase in the number of participants with a normal

spectrogram from review-assessment 1 (10 subjects) to review-assessment 2 (12 subjects) is interesting to highlight. In thevocal-hygiene group an improvement was also shown at review-assessment 1 immediately after treatment (4 more subjectsimproved), but this increase did not continue over time. The final result suggests that more than half of the voice-therapygroup (57.1%) eventually achieved a normal voice from a spectrographic point of view (bearing in mind that no subjectobtained a normal spectrogram at pre-treatment), while 45% of the participants in the vocal-hygiene group were assessed asnormal (of whom only 14% presented with a normal spectrograph at baseline).

Of the 5 participants in the voice-therapy group who were habitual tobacco smokers, 3 quit smoking altogether(pathology: 1 angiomatous polyp and 2 bilateral vocal nodules) and 2 reduced the daily quantity of tobacco smoked. In thevocal-hygiene group, 7 participants were smokers. Following the vocal-hygiene sessions, one participant had quit smokingsince beginning treatment (pathology: angiomatous polyp + nodule) and 3 reduced the daily quantity of tobacco smoked.The remaining 3 subjects continued to smoke as they had before treatment.

4. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to compare the treatment effects of two interventions (direct vs. indirect) at pre/post-treatment on a heterogeneous group of participants with dysphonia, using reduced multiple measures from the TeatinosProtocol (Rodrıguez-Parra et al., 2009).

Between-group analysis shows that both groups initially presented no significant differences in aerodynamics, acoustics,self-rating questionnaires, most of the laryngoscopic ratings, perceptual and spectrographic characteristics at pre-treatmentstage. Nevertheless, after treatment (post-1) the results showed significant differences between the types of treatment infavor of direct-intervention (voice-therapy) on 5 out of 8 of the continuous variables considered. These were maximum

exhalation time (MET), maximum phonation time during connected speech (MPTS), vocal well being, self-voice assessment andvocal-hygiene habits (as it shown in Table 7).

Further, there was a significant within-subjects, main effect for time of treatment (pre vs. post-1, post-2 and post-3) onthe 8 continuous outcomes analyzed which helped to confirm the effectiveness of treatment over time.

The results on the qualitative variables also supported pre–post advantages for voice-therapy group over vocal-hygienealone. The perceptual, spectrographic and morphofunctional explorations showed that direct treatment was more effectivethan indirect intervention for voice-disorders improvement, which was either maintained or increased over follow-upassessments (post-2 and post-3). The perceptual component grade and voice with an asthenic timbre are the most sensitiveones to the application of both treatments, although this is more notable in the application of voice-therapy. In terms ofvideo-laryngo-stroboscopic evaluation, the most disrupted assessments at pre-treatment were Glottal Closure and Amplitude.

Nevertheless, these indicators were also the one which most benefited from voice-therapy and continued to improve overthe repeated follow-up assessment sessions. At the final evaluation, 10 participants in the voice-therapy group received alaryngo-stroboscopic diagnosis of normal. No participants in the vocal-hygiene group received a normal diagnosis. From alaryngoscopic point of view, vocal therapy is just as effective in cases of angiomatous polyps (which requires surgicalintervention) as in cases of bilateral nodules (not requiring surgery). Even cases of fibrous nodules showed someimprovement with voice therapy (but not with vocal hygiene).

The vocal-hygiene group also showed a clear disadvantage with respect to the voice-therapy group on the spectrographicevaluation. At post-treatment, 8 participants in the voice-therapy group reached a normal spectrographic assessment versus2 participants in the vocal-hygiene group. It is worthwhile to highlight the increase of the number of participants in thevoice-therapy group who received a normal spectrogram at post-2 one month follow-up (10 participants) and at post-3 fourmonths follow-up (12 participants). The vocal-hygiene group showed a similar but lesser improvement from pre-treatmentto post-treatment (6 participants), which later did not increase.

M.J. Rodrıguez-Parra et al. / Journal of Communication Disorders 44 (2011) 615–630626

Author's personal copy

Smoking was also influenced by the type of treatment applied. Of the 5 smokers in the voice-therapy group, 3 quitsmoking and 2 considerably reduced the number of cigarettes they smoked each day. Of the 7 smokers in the vocal-hygienegroup, 1 quit, 3 reduced their consumption and 3 continued to smoke as usual. A greater involvement by the participant inthe recovery process is evident, as is a clearer insight into the importance of the care of the voice. This reduction in smokingcould be explained by a greater number of sessions and more contact between clinician and participant in the vocal therapygroup. Unfortunately, this is only speculation as we have not assessed motivation for giving up smoking and we have no dataon it.

However, an important result of this study is probably the interaction effect of treatment groups (voice-therapy vs. vocalhygiene) and the time of treatment (pre vs. post-treatment follow-up period), using continuous variables. According to thesedata, 3 aerodynamic-acoustic parameters (Maximum Phonation Time, Maximum Exhalation Time, Maximum Phonation Time

during Connect Speech) and 2 self-rating questionnaires (Self-voice Assessment, and Vocal Well-Being) show how both types oftreatment interact over time. Nevertheless, some statisticians believe that interactions diminish the main effects. Webelieve, however, that in this study the principle effects remain and, in fact, can be taken at face value. Our interpretation isthat the Time factor involved in a general tendency for improvement is mainly due to the effect of the vocal trainingtreatment condition and the interactions generally depend on the vocal-hygiene group performance, which tends to stay thesame or to decrease in relation to the pre-treatment stage. Meanwhile, the voice-therapy group achieves a performanceimprovement in these variables, as is clearly shown in Figs. 1 and 2.

Further, an ANCOVA analysis showed only 4 aerodynamics parameters and self-rating questionnaires as significantvariables (Maximum Phonation Time, Maximum Exhalation Time, Vocal Well-Being, Self-voice Assessment). These appeared to bethe most effective continuous variables to indicate differences between the two types of treatments studied (direct vs.indirect).

Thus, in the current study, the voice-therapy treatment is shown to have more positive effects than hygiene-therapytreatment in 4 to 5 of the 8 continuous measures of voice disorder analyzed, comparing the pre-treatment and the four-month follow-up period. These data are consistent with the results obtained by others studies which compared both types oftreatment (direct and indirect) in dysphonic samples (Behrman, Rutledge, Hembree, & Sheridan, 2008; Carding, Horsley, &Docherty, 1999; Gordon, Pearson, Paton, & Montgomery, 1997; Niebudek-Bogusz et al., 2007; Roy et al., 2001; Speyer, 2008).However, to our knowledge, there are practically no clinical voice research studies showing the effectiveness of voice therapyusing direct versus indirect multidimensional outcomes at long-term follow-up, as the present study carries out. In ouropinion, this provides new relevant data about treatment in voice-recovery programs.

Therefore, it can be concluded that the multidimensional ‘‘Teatinos’’ protocol (Rodrıguez-Parra et al., 2009) shortenedversion: at least 4 of the 8 continuous indicators, as well as perceptual, laryngoscopic and spectrographic dimensions, can beconsidered a useful tool in the diagnostics of dysphonia and in the tracking of therapeutic progress in direct as well asindirect treatment. In fact, these results are congruent with other studies, which also found perceptual, laryngoscopic,spectrographic, aerodynamic and psychological self-rating dimensions of voice among the most important with which toselectively differentiate pre–post changes across different etiologies of voice disorders and types of treatment (seeDejonckere, 2000a, 2000b; Friedrich & Dejonckere, 2005).

4.1. Limitations, caveats and areas for future research

Although the results shown here suggest that direct vocal therapy is more effective than a vocal-hygiene program, amore profound analysis of the treatment modalities is required. Firstly, the vocal-hygiene program published by Chan(1994), and similar subsequent versions (Broaddus-Lawrence, Treole, McCaabe, Allen, & Toppin, 2000; Wong, 1997) arebrief interventions (Roy et al., 2001). In consequence, the contact between the participant and therapist is limited, in clearcontrast to vocal-therapy programs where participant–therapist contact is essential, as for example, Carding et al. (1998)have pointed out. The indirect treatments, such as vocal hygiene, try to achieve, in clinical practice, positive effects andchanges in the participants with limited number of sessions, generally with the purpose of optimizing the clinicalresources which are frequently very scarce at busy hospitals and other clinical institutions. However, this procedure canoften be counter-productive when trying achieving the main goal of participant recovery. Conversely, it might be that anincrease in the number of sessions, the intensity and the frequency of the indirect treatment-programs (e.g. advice onvocal hygiene) is needed, but there is currently no information about the success and the effectiveness of this strategy andthis suggestion needs to be set against the need to ensure such an increase is not overwhelming for the participants.Therefore, further study is needed to evaluate how the duration and procedure of a vocal-hygiene program could influencethe results.

Future research should also resolve the limitations shown for some measures, such as those that demand perceptualjudgments (visual or auditory); for instance, perceptual, spectrograms, and laryngoscopic dimensions. This study did not setout to use blinded evaluators. This extra method of ensuring that the results were not biased by the researcher might be auseful consideration for future studies. However, typically, in small scale studies, in clinical settings, it is not feasible toachieve evaluators who are distinct from the therapy providers and thus this study reflects the clinical reality whereproviders and evaluators of this type of treatment are one and the same person. It is also necessary to underline that, inindividual analyses (within subjects/within group comparisons), the changes are not homogenous across all voiceparameters (Dejonckere, 2000b; Dejonckere et al., 2001; Speyer, 2008) neither do all participants progress in the same way.

M.J. Rodrıguez-Parra et al. / Journal of Communication Disorders 44 (2011) 615–630 627

Author's personal copy

An objective of future research would be to consider whether or not those voice-dimensions which have proved to besensitive to the diagnosis and treatment for groups of participants, are also significant in subject-to-subject analysis. Thistype of study might determine the characteristics of those participants that would best benefit from voice-therapy.

In conclusion:

1. The results of this study suggest superiority of a voice-therapy (direct treatment) approach over a vocal-hygiene aloneapproach (indirect treatment).

2. The voice-therapy treatment shows positive effects in 4–6 of the 8 continuous dimensions analyzed (aerodynamics,acoustics, and self-rating questionnaires).

3. This advantage extended to qualitative perceptual, laryngoscopic and spectrographic voice-dimensions.4. These data are similar to others, who also used coincident multidimensional voice measures for evaluating voice disorders

and therapy effectiveness in different clinical settings (for instance, Dejonckere, 2000a; Friedrich & Dejonckere, 2005).5. Furthermore, this study shows the effectiveness using multidimensional measures for showing long-term effects at

follow-up of voice-therapy (direct) versus vocal-hygiene (indirect). These are not currently reported in clinical practice.Multidimensional measures used over longer time periods would also help shed light on the effectiveness of currentvoice-therapy research.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Professor Dario Paez from Basque Country University (Spain) for insightful discussions about thestatistics methodology and Faustino Nunez, MD from the Hospital ‘‘Carmen y Severo Ochoa’’ of Asturias (Spain), for hishelpful comments regarding spectrographic analysis issues.

Appendix A. Vocal Hygiene Program

1. Explanation of normal voice mechanisms and laryngeal pathologies.� Images and models of normal larynges are presented� Images of pathological larynges are shown, describing different diagnoses (polyps, nodules, etc.)� Possible organic trauma of the vocal cords is described in terms of vocal abuse� The alteration of the voice due to disruption of normal vocal cord function leading to pathological changes

2. Vocal abuse and its consequences are explained.� Excessive speech or singing outside of work� Speaking quickly� Speaking loudly or raising the voice in noisy places (in class, bars, noisy streets)� Speaking or singing in an excessively high or low tone� Speaking or singing with excessive or insufficient force� Forced whispering� Forced clearing of the throat� Vigorous coughing� Emotional speech� Screaming� Producing strange noises or tense vocalizations� Tobacco smoking� Food and drinks which irritate the voice (very hot or very cold food or drink, fried, spicy or concentrated food, alcohol,

coffee, tea, etc.)� Eating too much before bedtime� High risk leisure activities (karaoke singing, shouting along with televised sport, etc.)� Exposure to external conditions which may irritate the voice (tobacco smoke, dust, heat, cold)

3. Correct (healthy) use of the voice.� Limited speech and singing outside of work� Slow speech� Avoidance of raised voice in noisy places, using alternative strategies to increase vocal force� Avoidance of tense vocal production (speaking at extreme tones and intensities, make strange noises, harsh vocal attack)� Drinking more water� Avoiding exposure to adverse external conditions� Reducing consumption of irritating food and drink� Maintaining emotional stability� Avoiding eating before bedtime� Reducing vocal abuse

M.J. Rodrıguez-Parra et al. / Journal of Communication Disorders 44 (2011) 615–630628

Author's personal copy

4. Using personalized strategies.

The speech-language pathologist and participant identified specific moments of vocal abuse in everyday situations anddiscussed strategies to limit or eliminate them altogether.

Appendix B. Continuing education questions

1. According to this study, the vocal-therapy is more effective than vocal hygiene in voice recovery:True/False

2. What were the types of voice-disorders of the participants in this study?a. Vocal nodules, polyps, angiomatous polyps, Reinke’s edema, and hypotonic dysphoniab. Vocal nodules, polyps, angiomatous polyps, Reinke’s edema, and spasmodic dysphoniac. Vocal fold paralysis with severe glottal incompetenced. Vocal fold scar/sulcus vocalis and Reinke’s edema

3. The acoustic parameter used in the current study was:a. Shimmerb. Harmonic–noise relationc. Jitterd. F0

4. The voice-therapy program of treatment was structured in the following way:a. Basic information and counseling, breathing, relaxation, production and placement, and carryoverb. Basic information and counseling, relaxation, breathing, laryngeal manipulation, production and placement, and

carryoverc. Basic information and counseling, relaxation, breathing, production and placement, and carryoverd. None of the above

5. The voice hygiene program involved educating the patient about how his or her laryngeal mechanism functions,identifying what might damage these functions, and establishing personalized strategies to deal their problems:

True/False

References

Adrian, J. A., Casado, J. C., Rodrıguez-Parra, M. J., & Gonzalez, M. (2003). Functional assessment and voice-therapy treatment of dysphonic patients: Results of aninterdisciplinary intervention of voice in hospital outpatient settings. Revista de Logopedia, Foniatrıa y Audiologıa, 23, 9–19.

Andrews, M., & Summers, A. (2002). Voice treatment for children and adolescents. San Diego, CA: Singular, Thompson Learning.Behrman, A. (2004). Common practices of voice therapist in the evaluation of patients. Journal of Voice, 19, 454–469.Behrman, A., Rutledge, J., Hembree, A., & Sheridan, S. (2008). Vocal hygiene education, voice production therapy, and the role of patient adherence: A treatment

effectiveness study in women with phonotrauma. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 5, 350–366.Biddle, A. K., Watson, L. R., Hooper, C. R., Lohr, K. N., & Sutton, S. F. (2002). Criteria for determining disability in speech-language disorders. Evidence Report/

Technology Assessment, 52, 1–4.Boone, D., & McFarlane, S. (2000). The voice and voice-therapy. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.Bovo, R., Galceran, M., Petruccelli, J., & Hatzopoulos, S. (2007). Vocal problems among teachers: Evaluation of a preventive voice program. Journal of Voice, 21, 705–

722.Branski, R., Murry, T., & Rosen, C. (2000). Voice therapy. Otolaryngology and facial plastic surgery. Available at: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/866712-

overview.Broaddus-Lawrence, P., Treole, K., McCaabe, R., Allen, R., & Toppin, L. (2000). The effects of preventative vocal-hygiene education on the vocal-hygiene habits and

perceptual voice characteristics of training singers. Journal of Voice, 14, 58–71.Carding, P., Horsley, I., & Docherty, G. (1999). A study of the effectiveness of voice-therapy in the treatment of 45 patients with nonorganic dysphonia. Journal of

Voice, 13, 72–104.Carding, P., Horsley, I., & Docherty, G. (1998). The effectiveness of voice-therapy for patients with non-organic dysphonia. Clinical Otolaryngology, 23, 310–318.Casper, J. (2001). Treatment outcomes in occupational voice disorders. In P. H. Dejonckere (Ed.), Occupational voice: Care F cure (pp. 187–199). Kugler Publications:

Hague.Casper, J., & Murry, T. (2000). Voice-therapy methods in dysphonia. Otolaryngologic Clinics of North America, 33, 983–1001.Chan, R. W. (1994). Does the voice improve with vocal-hygiene education? A study of some instrumental voice measures in a group of kindergarten teachers.

Journal of Voice, 8, 279–291.Colton, R., & Casper, J. (1996). Understanding voice problems: A physiological perspective for diagnosis and treatment. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins.Dejonckere, P. H. (2000a). Assessing efficacy of voice treatments: A guideline. Revue de Laryngologie, Otologie et Rhinologie, 121(5), 307–310.Dejonckere, P. H. (2000b). Clinical implementation of a multidimensional basic protocol for assessing functional results of voice-therapy. A preliminary study.

Revue de Laryngologie, Otologie et Rhinologie, 121(5), 311–313.Dejonckere, P. H. (2002). Clinical and instrumental examination. Relationship between laboratory, perceptual and stroboscopic results. In Proceedings of the

Congreso Internacional de Foniatrıa, Audiologıa, Logopedia y Psicologıa del Lenguaje.Dejonckere, P. H., Bradley, P., Clemente, P., Cornut, G., Crevier-Buchman, L., Friedrich, G., et al. (2001). A basic protocol for functional assessment of voice

pathology, especially for investigating the efficacy of (phonosurgical) treatments and evaluating new assessment techniques. Laryngology, 258, 77–82.Dunnet, C., MacKenzie, K., Sellars, G., Robinson, K., & Wilson, J. (1997). Voice-therapy for dysphonia. Still more art than science? European Journal of Disorders

Communication, 32, 333–343.Friedrich, G., & Dejonckere, P. H. (2005). The voice evaluation protocol of the European Laryngological Society (ELS)—First results of a multicenter study. Laryngo-

Rhino-Otologie, 84(10), 744–752.Gillivan-Murphy, P., Drinnan, M. J., O’Dwyer, T. P., Ridha, H., & Carding, P. (2006). The effectiveness of a voice treatment approach for teachers with self-rating voice

problems. Journal of Voice, 20, 423–431.

M.J. Rodrıguez-Parra et al. / Journal of Communication Disorders 44 (2011) 615–630 629

Author's personal copy

Gordon, M., Pearson, L., Paton, F., & Montgomery, A. (1997). Predictive assessment of vocal efficiency (PAVE). A method for voice-therapy outcome measurement.Journal of Laryngology and Otology, 111, 129–133.

Hirano, M. (1981). Psycho-acoustic evaluation of voice: GRBAS scale for evaluating the hoarse voice. Clinical examination of voice, Wien: Springer-Verlag.Holmberg, E., Doyle, P., Perkell, J., Hammarberg, B., & Hillman, R. (2003). Aerodynamic and acoustic voice measurements of patients with vocal nodules: Variation

in baseline and changes across voice-therapy. Journal of Voice, 17, 269–282.Holmberg, E., Hillman, R., Hammarberg, B., Sodersten, M., & Doyle, P. (2001). Efficacy of a behaviorally based voice-therapy protocol for vocal nodules. Journal of

Voice, 15, 395–412.Kempster, G., Gerratt, B., Verdolini, K., Barkmeier-Kraemer, J., & Hillman, R. (2009). Consensus auditory-perceptual evaluation of voice: Development of a

standardized clinical protocol. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 18, 124–132.Kotby, M. (2006). Egypt: Four decades of voice research. The ASHA Leader, 11, 30–32.Larson, G., & Mueller, P. (1991). The efficacy of voice-therapy: A national survey. Presented at Annual Convention of the American Speech-Language-Hearing

Association.Mathieson, L. (2001). Greene and Mathieson’s the voice and its disorders (6th ed.). London: Whurr.Morrison, M., & Ramaje, L. (1996). Tratamiento de los trastornos de la voz. Barcelona: Masson.Mueller, P. B., & Larson, G. W. (1992). Voice-therapy practices and techniques: A survey of voice clinicians. Journal Communication Disorders, 25, 251–260.Niebudek-Bogusz, E., Kuzanska, A., Błoch, P., Domanska, M., Woznicka, E., Politanski, P., et al. (2007). Applicability of Voice Handicap Index to the evaluation of

voice-therapy effectiveness in teachers. Medycyna Pracy, 58, 501–509.Niebudek-Bogusz, E., Sznurowska-Przygocka, B., Fiszer, M., Kotyło, P., & Sinkiewicz, A. (2008). The effectiveness of voice-therapy for teachers with dysphonia. Folia

Phoniatrica et Logopaedica, 60, 134–141.Ortiz, E., Costa, E., Spina, A., & Crespo, A. (2004). Multidisciplinary protocol proposal for professional dysphonia: Preliminary study. Revista Brasileira de

Otorrinolaringologia, 70, 590–596.Pannbacker, M. (1998). Voice treatment techniques: A review and recommendations for outcome studies. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 7, 49–

64.Pasa, G., Oates, J., & Dacakis, G. (2007). The relative effectiveness of vocal-hygiene training and vocal function exercises in preventing voice disorders in primary

school teachers. Logopedics, Phoniatrics, Vocology, 32, 128–140.Ricci, A. (2003). The clinical and instrumental evaluation of voice disorders. In Proceedings of the V Simposium Nacional de Logopedia.Ricci, A., & Lucchini, E. (2002). La valutazione soggettiva ed oggettiva della disfonıa. Il protocolo SIFEL. In Proceedings of the XXXVI Congreso Nazionale della Societa

Italiana di Foniatria e Logopedia.Rodrıguez-Parra, M. J., Adrian, J. A., & Casado, J. C. (2009). Voice-therapy used to test a basic protocol for multidimensional assessment of dysphonia. Journal of

Voice, 23, 304–318.Rodrıguez-Parra, M. J., Casado, J. C., Adrian, J. A., & Buiza, J. J. (2006). Present situation of the otorhinolaryngology departments in the Spanish hospitals.

Heterogeneity in handling voice disorders. Acta Otorrinolaringologica espanola, 57, 109–114.Roy, N., Gray, S., Simon, M., Dove, H., Corbin-Lewis, K., & Stemple, J. (2001). An evaluation of the effects of two treatment approaches for teachers with voice

disorders: A prospective randomized clinical trial. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 44, 286–296.Roy, N., Weinrich, B., Gray, S. D., Tanner, K., Stemple, J., & Sapienza, C. (2003). Three treatments for voice-disordered teachers: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of

Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 46(3), 670–688.Shrivastav, R. (2005). Multidimensional scaling of breathy voice quality: Individual differences in perception. Journal of Voice, 20, 211–222.Speyer, R. (2008). Effects of voice-therapy: A systematic review. Journal of Voice, 22, 565–580.Titze, I. (1995). Workshop on acoustic voice analysis—Summary statement. Iowa: National Center for Voice and Speech.Wilson, D. (1987). Voice problems in children (3rd ed.). Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins.Wong, E. (1997). Efficacy of a vocal-hygiene program in hyperfunctional laryngeal disorders. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. University of Hong Kong.Wuyts, F., De Bodt, M., Molenberghs, G., Remacle, M., Heylen, L., Millet, B., et al. (2000). The Dysphonia Severity Index: An objective measure of vocal quality based

on a multiparameter approach. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research, 43, 796–809.Yun, Y., Kim, M., & Son, Y. (2007). The effect of vocal hygiene education for patients with vocal polyp. Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, 137, 569–575.

M.J. Rodrıguez-Parra et al. / Journal of Communication Disorders 44 (2011) 615–630630