Commemorative Surrogation and the American South's Changing Heritage Landscape

-

Upload

southernmiss -

Category

Documents

-

view

4 -

download

0

Transcript of Commemorative Surrogation and the American South's Changing Heritage Landscape

Tourism GeographiesiFirst 2012, 1–20

Commemorative Surrogation and theAmerican South’s Changing HeritageLandscape

OWEN DWYER*, DAVID BUTLER** & PERRY CARTER†*Department of Geography, Indiana University-Purdue University, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA**Department of Political Science, International Development and International Affairs, University ofSouthern Mississippi, Hattiesburg, Mississippi, USA†Department of Geosciences, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas, USA

Abstract The past two decades have witnessed momentous changes on the American South’sheritage landscape. First, and most dramatically, ascendant civil rights museums have es-tablished themselves as bona fide heritage attractions. Second, and more subtly, a nascentmovement on the part of plantation house museums is afoot to engage with the lives and labourof enslaved African Americans. The two trends are interrelated and the result is a regionalheritage landscape that is more attuned to the dynamics of racial oppression than at any timein the past. Geographers and other tourism researchers have begun to document and analysethese changes, seeking to better understand the motives and implications that are reworking theregion’s heritage scene. The task remains, however, to develop a more nuanced understandingof audience reactions to the evolving content of southern heritage tourism. Drawn from twoextent surveys of visitors to civil rights museums and a plantation museum, this article uses theconcept of commemorative surrogation to interpret audience evaluations in order to better un-derstand visitors’ assessment of the changing landscape of southern heritage tourism. Resultsof the analysis suggest that whereas concerns over deficient surrogation are held by visitors atboth civil rights and plantation museums, charges of excessive surrogation are limited to civilrights museums. The implication for the cultural landscape is a potentially revived, searchingassessment of the region’s past.

Key Words: African American, American South, civil rights, commemoration, heritagetourism, landscape, monument, museum, plantation, surrogation

Introduction

In the wake of the Civil Rights Movement, the American South’s landscape of col-lective memory has been radically reworked to include a distinctly African Americanperspective on the region’s past (Romano & Raiford 2006; Dwyer & Alderman2008a; Algeo 2012). Led by the renaming of streets for Martin Luther King, Jr., the

Correspondence Address: Dr Owen Dwyer, Department of Geography, Indiana University-Purdue Univer-sity, Indianapolis, IN 46202, USA. Fax: +317-278-5220; Tel.: +317-274-8877; Email: [email protected]

ISSN 1461-6688 Print/1470-1340 Online /12/000/00001–20 C© 2012 Taylor & Francishttp://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2012.699091

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ow

en D

wye

r] a

t 04:

19 2

9 Ju

ne 2

012

2 O. Dwyer et al.

designation of the King National holiday in 1986, and the installation of Maya Lin’scivil rights memorial in 1989 in Montgomery, Alabama, African American-themedheritage sites and events have steadily grown in both number and popularity. In re-sponse, a major niche in the region’s tourism industry has arisen to simultaneouslyprime and sate demand for African American heritage (Armada 1998; Dwyer 2002;Dann & Seaton 2002; Hanna 2008).

African American-themed heritage sites join an already well-established landscapeof southern heritage attractions. Among these sites, the plantation ‘Big House’ standsas the archetypical symbol of the Antebellum South as well as the region’s originalheritage attraction (Brundage 2000; Eichstedt & Small 2002; Hoelscher 2003). Theregion boasts hundreds of plantation sites open to the public and state support inthe form of promotional materials and advertising. As witnessed by the enduringpopularity of Gone with the Wind and similar media, the audience for a distinctlynostalgic representation of the plantation is large, geographically extensive, andenduring (Butler 2001; Alderman & Modlin 2008; Buzinde & Santos 2009; Modlinet al. 2011).

That said, there is a growing body of evidence that in some instances the regionalpresentation of the plantation departs from the traditional marginalisation and erasureof the lives and labours of the enslaved (Alderman & Campbell 2008; Butler et al.2008; Modlin 2008). This nascent re-working of the memorial landscape to be moreinclusive and affirming of the region’s African American heritage suggests the CivilRights Movement’s widespread effect on the demographics and ethos associatedwith heritage tourism. Taken together, civil rights- and these evolving plantation-themed sites confirm the American South’s reputation as a region where place andheritage are thoroughly intertwined as well as suggesting that the region’s heritageprofile is undergoing potentially far-reaching changes (Savage 1997; Brundage 2000;Brundage 2005).

Geographers and other social scientists have completed important work regardinglandscape representations of slavery and civil rights (Hoelscher 2006; Dwyer &Alderman 2008a; Inwood & Martin 2008). In the context of the cultural turn incritical scholarship, extant studies have concentrated on the political economy andsymbolic-discursive production of these sites. As a result, those interested in theSouth’s memorial landscape have placed considerable emphasis on understandingthe production and representation of these landscapes-cum-tourist attractions. Tothis swelling literature on landscapes of slavery and civil rights, our study adds acomparative perspective that for the first time specifically examines these twinnedsites in the context of southern heritage. Moreover, this article offers a complementto the field’s burgeoning literature regarding the production of memorial landscapesby explicitly seeking a fuller understanding of the audience for southern heritageand their evaluation of it. Basic questions related to the audience for this changingversion of southern heritage have not received a systematic examination. Specifically,how do visitors react to and evaluate the changing narratives on display? This focus

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ow

en D

wye

r] a

t 04:

19 2

9 Ju

ne 2

012

Commemorative Surrogation 3

on evaluation responds to calls by geographers to address a gap in the scholarlyliterature on landscape and memory regarding the role of visitors in the performativeand interpretive aspects of commemoration (Schein 2006; Wiley 2007).

At the core of our study are visitor surveys and interviews conducted separatelyby the authors at two popular heritage attractions: Laura Plantation in Vacherie,Louisiana, in 2001 and the National Civil Rights Museum (NCRM) in Memphis,Tennessee in 1998 (Dwyer 2000; Butler 2002). We returned to this data set – whichalthough dated remains to our knowledge the most complete body of demographicand site evaluation data on the subject – in response to a growing awareness of theneed for a robust comparison of these twinned sites and visitors’ evaluation of them.While portions of the data set are no longer accurate, e.g. income figures, and thenational political content in the United States has changed, e.g. the election of BarakObama, site visits in 2009 and 2010 confirmed our impression that both the contentand visitor demographics of these attractions remain largely unchanged. As describedbelow, we analysed unpublished portions of the survey and interview data in order toestablish a baseline for future study of who visits these attractions and their reactionsto them. Moreover, the two sites are linked by the Mississippi River – Memphisat its head and Vacherie four hundred miles south at its foot – and this sharedgeographic situation renders them emblematic of the region’s twinned legacies ofenslavement and resistance. Despite the complications of comparing two separatedata sets and the obvious time–lag since their collection, the present analysis offersa first, albeit awkward, contribution from tourism studies towards understanding theinfluence of landscape’s more-than-representational aspects on visitors. In line withthis contemporary interest in the affective experience of landscape, our study ofvisitor evaluations emphasises expressions of respondents’ sense of identity and siteexperience in reaction to the commemorative surrogates put forward by memorialentrepreneurs to represent African American history at these sites.

The Racialized Political Economy of Southern Heritage Tourism

The efforts of memorial entrepreneurs and the practice of reputational politics arecentral to understanding the political-economic evolution of southern heritage tourism(Radford 1992; Brundage 2005; Alderman 2006; Post 2009). The terms ‘memorialentrepreneur’ and ‘reputational politics’ derive from work conducted in the studyof collective memory that stresses the role of purposive agents, working alone or inleague with like-minded collaborators, to produce historical reputations and traditions(Fine 2001; Dwyer & Alderman 2008b). In the context of the South, the ranks ofthese memory producers were drawn from several sources: the owners of plantationsseeking a livelihood; civic boosters in the mould of a chamber of commerce; and,more recently, state officials associated with tourism promotion. Here, the figure of theentrepreneur is distinct from both communitarian-oriented oral traditions associatedwith griots and the managerial ethos of the civic archivist and historian.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ow

en D

wye

r] a

t 04:

19 2

9 Ju

ne 2

012

4 O. Dwyer et al.

The impetus for the memorial entrepreneur arose in the South amid the desola-tion of the post-Civil War Reconstruction-period. Confronted by military occupation,exhausted ecosystems, exploitative labour strategies and vigorous international com-petition in commodity production, elements of the defunct planter class and urbanboosters sought out new capital accumulation strategies beyond the traditional re-liance on cash crops. The transformation of select plantation sites from primary sectorproduction to tertiary sector attraction presaged the current era’s shift from Fordistmanagerialism to entrepreneurial urbanism across the United States (e.g. the produc-tion of festival markets and other heritage place-based attractions). The strenuousefforts of late 19th and early 20th century regional elite to promote the South as abastion of ‘business friendly’ employment laws, inexpensive labour and salubriousclimate, are most famously attested to by the migration of textile mills from NewEngland to the Piedmont. Less heralded were elite efforts to render the South anattractive destination for disaffected northerners seeking respite from the perceivedevils and compromises of industrial society. In this sense, the region’s cultivationof heritage tourism as a place-based growth strategy presages present-day efforts atcommercial place-making associated with festival markets and the like.

In so doing, memorial entrepreneurs literally capitalized the nascent plantationmythos by producing a landscape of nostalgic heritage. The audience for this mythos-cum-marketing plan was simultaneously wealthy northern tourists and game huntersbut also those southerners seeking to re-establish the discursive moorings of whitesupremacy in the face of African Americans exercising their new-won rights. Centralto this discourse of regional romanticism was the paternalistic rendering of enslavedand newly free African Americans as of the land, in need of care, simultaneouslyindispensable yet threatening to the social order. These twinned themes of placepromotion and white-dominated racial order would eventually coagulate to form themoonlight-and-magnolias, Lost Cause mythology on display at so many plantationheritage sites.

Marginalised or outright ignored in this white version of the past, AfricanAmericans produced an alternative rendering of the region. For instance, the civicinfrastructure of streets and schools named for black luminaries dates from the mostrepressive period of Jim Crow segregation. These efforts continued longstanding oraland folk traditions of insurgent collective memory (e.g. songs, stories and sermonsthat commemorated resistance and transgression of the region’s racial order). Out ofthese efforts grew the narratives through which African Americans laid claim to theright of full participation in American society. The Civil Rights Movement’s combi-nation of successful efforts to dismantle legal separation and the persistent failure toovercome the country’s racialised political economy and enduring white racial iden-tity, led many activists to favour cultural politics as a likely front on which to progress.Faced with disparaging representations or outright invisibility on the heritage land-scape, civil rights activists pursued their agenda as memorial entrepreneurs. Theypromoted a cultural identity that resonated with themes of heritage and place. The

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ow

en D

wye

r] a

t 04:

19 2

9 Ju

ne 2

012

Commemorative Surrogation 5

result was an efflorescence of public and commercial heritage activity that extendedthe Civil Rights Movement’s ethos into art galleries, storytelling and music festivalsand independent bookstores. At the head of this tradition is the growing number ofmuseums and memorials dedicated to the Movement.

Politically, both civil rights memorials and plantation sites materialize discoursesassociated with the meaning of race and racism. In the case of civil rights memorials,they host Movement anniversaries and on-going political action. In addition, theyare vibrant public spaces that invite visitors to consider the place of civil rights,radicalism, and racial identity in American society (Dwyer & Alderman 2008a). Fortheir part, most plantation heritage sites offer a thoroughly nostalgic presentationof genteel living, commonly rendering African Americans marginal or invisible(Eichstedt & Small 2002). That said, some plantation sites are responding to the post-Movement era. The result is a contemporary memorial landscape that simultaneouslymarks a point of continuity and change with past practices of (mis)representingSouthern heritage. The implicit tensions and relative proximity between these twoapparently antithetical commemorative landscapes inspire questions regarding theiraudiences and attendant reactions to the sites.

Commemorative Surrogates

The on-going recasting of southern history by memorial entrepreneurs to include arobust, authentic African American presence – in contrast to a legacy of marginalinclusion and outright erasure – may be understood through the theoretical lens ofcommemorative surrogates. Grounded in Civil Rights-era agitation in pursuit of acultural politics of affirmative representations, memorial entrepreneurs have soughtout appropriate commemorative surrogates over the past four decades (Dwyer &Alderman 2008a). Put forward by Roach (1996) and Lambert (2007) and recentlyapplied to Savannah, Georgia’s memorial landscape by Alderman (2010), the con-cept of a commemorative surrogate describes heritage representations that addressthe historical-cultural void resulting from symbolic annihilation (Eichstedt & Small2002). Memorial surrogates assume the burden of conveying a history pockmarkedwith notorious gaps or outright obliteration in the extant record of material-cultural re-mains, oral traditions and archival sources. As such, memorial surrogates commonlyprovoke responses – often strong – related to the extent to which their audiencebelieves they correctly represent the past.

In the context of African American heritage tourism, surrogates provide a tangibleexperience of the otherwise ineffable past for visitors whose interest motivates themto shun passive media and seek out a visceral connection with the past. These heritagesurrogates – which range from surviving elements of material culture to ‘authenticreproductions’ and re-enactments of the past – stand in for a history perceivedto be lost or nearly so. In the case of the history of African American slavery,commemorative surrogates include mytho-historic characters like Alex Haley’s Kinte

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ow

en D

wye

r] a

t 04:

19 2

9 Ju

ne 2

012

6 O. Dwyer et al.

Kunte, specific figures such as Harriet Tubman and a growing number of heritagesites that interpret the lives and labour of the enslaved.

Stemming from their scarcity and the gravity of responding to the symbolic an-nihilation of African American histories, commemorative surrogates are susceptibleto intense scrutiny from their audience. In some cases, commemorative surrogatesare judged to have transgressed sensitive norms and emotions, a situation describedas excessive surrogation (Alderman 2010). In these instances, the surrogate is inter-preted as irritating an already difficult situation and intensifying the pain associatedwith the sense of loss accompanying an obscured or debased past. For example, re-enactments of slave marts have been criticized for being too explicit while exhibitsof photographic and narrative accounts of lynching commonly generate concern overtheir violent content (Handler & Gable 1997; Horton & Horton 2006).

In direct contrast, the charge of insufficient content and inarticulate delivery maybe lodged when the commemorative surrogate’s message is perceived as lackingauthenticity and failing to establish a robust emotional connection with contemporaryaudiences (Alderman 2010). An example of this kind of deficient surrogation is thepractice at plantation-house sites of referring to the enslaved as ‘servants’, in theprocess obscuring the structural constraints of their condition as chattel. Criticismthat levels the complaint of deficient surrogation indicates an imperative to learn moreabout a subject – in contrast to simple curiosity – in response to a heritage narrative thatfails to provide sufficient detail or excludes important subjects. Deficient surrogationalso entails comments suggesting that the site is not as effective and engaging as itmight be. These concerns inform complaints about a lack of interactivity associatedwith passive, text-heavy exhibits that require extensive reading and come across asremote and mediated.

Prominent among the sites that provide surrogates to help visitors engage withAfrican American history are civil rights museums. In addition, a small number ofplantation museums invite visitors to investigate both the profound and mundanecondition of enslavement. A content analysis of the results of visitor surveys andinterviews at two representative museums suggests that surrogate-related criticismsinform respondents’ reactions to these Southern heritage sites.

The Study Sites and Surveys

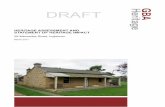

The first study site, Laura Plantation (‘Laura’), is located in southern Louisianaand noted for its ‘Big House’ and slave quarters (Figures 1 and 2). Constructedin 1805, Laura is commemorated as a Creole plantation – Creoles are Louisiananswhose language and genealogies have French, Spanish, and West African roots. Laurawas chosen as a study site because from the perspective of plantation tourism andrepresentations of slavery, it subtly challenges many of the dominant narratives thatanimate discourses of Southern heritage. Drawing from the memoirs of Laura LocoulGore, the plantation’s namesake, the current owners present visitors with tours of the

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ow

en D

wye

r] a

t 04:

19 2

9 Ju

ne 2

012

Commemorative Surrogation 7

Figure 1. Main house at Laura Plantation (photo by P. Carter).

plantation that represent the intimate social history of the house, its owners, as well asthe enslaved African Americans who staffed it. Unlike the vast majority of plantationheritage sites – southern Louisiana alone is home to more than 25 of them – slaveryis portrayed at Laura alongside artefacts of gracious, genteel living. The result forour study is a site that combines elements that both confirm and challenge the normalrendering of plantation heritage.

The second study site is the NCRM in Memphis, Tennessee (Figure 3). The museumencompasses the remains of the former Lorraine Motel where Dr Martin Luther King,Jr. was gunned down on 4 April 1968. As both a shrine and museum, the NCRMis representative of sites across the region that challenge the nostalgic trappingsof traditional Southern history. Placed in the context of the history of racism andcommemoration in the United States, a deep sense of cultural change accompaniesthe NCRM. In terms of the size of the facility and audience, the NCRM joins theKing National Historic Site in Atlanta and the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute asamong the most significant museums dedicated to the Civil Rights Movement andAfrican American history more generally.

At the time of King’s assassination, the Lorraine motel was one of the few thatprovided accommodations for Black travellers during segregation. In the wake of the

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ow

en D

wye

r] a

t 04:

19 2

9 Ju

ne 2

012

8 O. Dwyer et al.

Figure 2. Slave quarters at Laura Plantation (photo by P. Carter).

assassination, the site attracted thousands of visitors each year, many of whom cameaway from the site with a sense that more should be done to preserve it. In 1986, abill was introduced into the Tennessee state legislature to support the construction ofa museum on the site of King’s death. Since its opening in 1991, the museum hasconsistently attracted 80,000 annual visitors. A new wing of the museum – largelyfunded with private donations – incorporates the boarding house from which theassassin, James Earl Ray, stalked King and presents information regarding varioustheories associated with his murder.

The initial surveys and interviews were conducted at Laura in April 2002 and atthe NCRM from June to August 1998. Two challenges to our present project areimmediately obvious. First, the original survey instruments and interview questionsused at these sites were developed and executed independently of one another, i.e.before our present collaboration was initiated. In response, we have re-analysed thedata in an attempt to control for the limitations and complications resulting from subtledifferences in specific questions and categories. For instance, one survey categorisedincome by three steps and the other by five. While these differences complicate thecomparison of the data sets, both surveys were designed to achieve similar ends –document visitor demographics and elicit their evaluation of these sites – and followed

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ow

en D

wye

r] a

t 04:

19 2

9 Ju

ne 2

012

Commemorative Surrogation 9

Figure 3. Main entrance, National Civil Rights Museum (photo by P. Carter).

established procedures for social scientific survey and interview methods. The broadoverlap of each survey’s methods and their results allowed us to compare and contrastdata from each site.

The second challenge is equally apparent: the surveys and interviews are over adecade old. As a result, time-sensitive data, e.g. income, is no longer current. Wesought to rectify this deficiency via site visits and informal interviews in 2009 and2010. These visits confirmed our impression that the bulk of the demographic data,the original verbatim comments and the nominal, Likert-scale evaluations remainrelevant albeit in the changed context of the election of an African American aspresident and arrival of the King Memorial on the National Mall in Washington,D.C. Thus, our analysis is compromised by uncoordinated methods and the age ofthe data. The benefits of establishing the only extant data set of its kind and layingthe foundation for subsequent comparisons between these Southern heritage sites,however, augured for conducting our analysis.

Our present analysis is based on 1,132 randomised surveys collected at Laura and223 at the NCRM (see Table 1). The data was collected with grants from the Universityof Southern Mississippi and the National Science Foundation (SBR-9811145). Surveydistribution and collection at the NCRM was undertaken for 60 non-consecutive

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ow

en D

wye

r] a

t 04:

19 2

9 Ju

ne 2

012

10 O. Dwyer et al.

Table 1. Demographic data from Laura and NCRM

Laura NCRM

Total respondents 1,132 223Average age 46.4 40Percentage of respondents older than 25 97.2% 71.3%More than a high school education 91.4% 73.1%Income greater than $30,000 92.4% 82.0%Percentage of respondents female 62.3% 68.7%Race of visitors

White 85.0% 35.0%African American 3.5% 60.0%Other 11.5% 5.0%

hours, 1 June–1 August, on weekends and weekdays, mornings and afternoons. Asvisitors left the NCRM’s exhibit hall, adults were asked to participate in the survey.The number of visitors who declined to participate was low (n = 12). At Laura,surveys were distributed and collected, 8–20 April, and represent approximately oneout of every three visitors to the Laura site (or 31.47%) during the thirteen days ofthe survey.

In both cases, survey instruments were created prior to the data collection effortsand composed of nominal, ordinal and categorical questions. Some of the quotespresented below come from the open-ended responses of the surveys. Parallel to thesurvey a random selection of people were asked to sit for a recorded interview as timeallowed during the survey process. These interviews were transcribed. At Laura, theinterviews asked the following questions ‘What did you like best about the tour’?‘What did you like least about the tour’? When you hear the word ‘plantation’ whatimages does that word bring to mind? If the people did not mention slavery to thispoint then a final question was asked ‘Do you associate plantations with slavery’?At the NCRM, visitors were asked to evaluate their museum experience in terms ofwhat if anything they would change about its presentation of the Movement.

Demographically, visitors to Laura and the NCRM conform to established normsassociated with the audience for Southern heritage (Butler et al. 2008). While ac-knowledging the impossibility of encapsulating an ‘average’ visitor, we have com-piled composite portraits of visitors to each site to augment the data table presentedabove. The composite visitor to Laura is a white female with a bachelor’s degreeand possibly an advanced graduate degree. She is a member of a household whoseannual income was near or above $100,000 and is 50 years old. She learned about theLaura Plantation through a brochure or travel guide and is staying in New Orleanson a personal vacation. She hales from the Northeast or West Coast. Not surprisinglygiven the self-selecting nature of museum visitation, she was pleased with the tour

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ow

en D

wye

r] a

t 04:

19 2

9 Ju

ne 2

012

Commemorative Surrogation 11

and is mostly interested in local history and culture, the original owners, architecture,and, significantly, slavery at plantations.

Her counterpart at the NCRM is also a college graduate but younger – 39-years oldon average – and African American. Her annual household income of $38,000 wasconsiderably lower. She travelled approximately the same distance to visit Memphis –over 500 miles – with friends or family members from the East or West coast forwhat will be her first visit to this museum, or any other civil rights museum for thatmatter. In contrast to the visitor to Laura who learned of the site via industry literature,the composite visitor to the NCRM reported learning about the site primarily fromfriends or family with limited input from guide and tour books. Like other tourists,she visited multiple cultural or historical attractions while in town.

In both cases, visitors to Laura and the NCRM confirm and subtly challengeexpectations associated with Southern heritage attractions. That the bulk of visitorsto these sites are well-educated women visiting from outside the region fits with theprofile of the heritage tourist more generally. Two facets of the experience howeverchallenge past trends. First, the presence of an attraction like the NCRM – establishedwith state support at the site of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination – marks asignificant departure from the South’s traditional array of heritage sites. Second,those visitors to Laura indicated ‘slavery’ as a topic of interest suggests a newwillingness among this segment of the touring public to learn about a subject thatremains largely unacknowledged at the majority of antebellum tourist attractions.

In addition to collecting quantitative data via questionnaire, respondents at bothmuseums were invited to participate in semi-structured interviews regarding whatthey would have changed about the site’s presentation. Not surprisingly nearly allrespondents reported a high degree of satisfaction with Laura or the NCRM. Open-ended follow-up questions related to the amount of attention given to particular topicsat the museums as well as verbatim comments disclosed a more critical perspectiveon the part of approximately a third of all respondents. Central to our interpretationof visitors’ evaluation of site content is the concept of surrogation.

Analysis

Excessive Surrogation

Among those respondents expressing a critical perspective, objections related to ex-cessive surrogation were muted in comparison to concerns over deficient surrogation(see below). Comments indicative of excessive surrogation expressed the perspectivethat the site’s representation of the subject was too literal or portrayed the subjectmatter in a negative manner. In select cases, respondents went so far as to expressfeelings of fear, loathing and disgust. These comments suggest that for some re-spondents the surrogate representation did more harm than good by engendering anegative reaction to what is already a sensitive subject.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ow

en D

wye

r] a

t 04:

19 2

9 Ju

ne 2

012

12 O. Dwyer et al.

Importantly, the analysis of the survey and interview data did not disclose anyreactions from visitors to Laura that could be classed as representative of excessivesurrogation. That few visitors to Laura found the site’s representation of slavery to beexcessive is not particularly surprising. Not only is it unlikely that Laura’s managerswould alienate the site’s largely white audience but whites – even those interestedin the plantation South – may be less discerning of representations of slavery thanAfrican Americans and thus less likely to express concerns over representationalnuance and implication. Given the small number of African Americans among ourLaura respondents we can only speculate that the same representations – or lackthereof – may well inspire complaints of excessive surrogation from audiences forwhom slavery is more personal and intimate. Despite the fact that Laura devotesmore attention to slavery than other plantations, it is unlikely that the site’s managerswould explicitly explore, for instance, the underlying violence that permeated theexperience of enslavement. Complaints of excessive surrogation would presumablyemerge, for instance, if the more authoritarian aspects of extracting surplus valuefrom the enslaved were portrayed.

Charges of excessive surrogation were more pronounced at the NCRM. Whereasthe museum’s subtext is characterised by the twinned themes of tragedy and tran-scendence, some respondents reacted strongly to the museum’s treatment of past andongoing racial oppression. In terms of charges of excessive surrogation at the NCRM,physical artefacts related to the Ku Klux Klan were of special concern among AfricanAmerican respondents. In particular the presence of Ku Klux Klan robes and hoodsinstalled in a display cabinet nearby the museum’s main exhibit generated comment.Representative of this reaction, one respondent wrote: ‘I would remove the KKKdress attire’. This comment and others similar to it suggest discomfort regarding themanner in which the infamous terrorist group was included in the exhibit. Informalcomments from respondents lead us to believe that some visitors objected to givingthe Klan any recognition.

Also singled out for comment was the role of Jacqueline Smith, an AfricanAmerican protester at the site. Smith’s protest at the museum is based in the chargeof excessive surrogation. Specifically, she seeks to persuade visitors to not enter themuseum on the grounds that it sensationalises violence. Further, she charges that themuseum could better serve the black freedom movement’s ideals by promoting eco-nomic and educational empowerment, not a passive history museum (Jones 2000). Atits core, Smith’s criticises the museum for what she believes is an insensitive repre-sentation of the Movement’s goals and meaning. Several respondents noted Smith’sprotest, one of them sharing that she ‘almost didn’t come in after talking to the womanwho lives across the street. While I certainly believe she has a right to have her say, itwould be nice to have someone out there to give the opposing view for the city’. Thecomment suggests that Smith’s charge of excessive surrogation, while not successfulin its goal of denying the museum its audience, has made an impression with somevisitors.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ow

en D

wye

r] a

t 04:

19 2

9 Ju

ne 2

012

Commemorative Surrogation 13

In a related vein the emotional intensity of the museum drew comment fromrespondents, many of them describing the museum as ‘too much’ and ‘overwhelming’.For instance, a question that asked respondents to judge the amount of attentiondevoted to positive contributions from whites to the Movement’s success drew thiscomment from an African American visitor: ‘Too emotional to answer this questionat present time’! The comment of another respondent summed up the impressionsof many others: ‘It (the exhibit) has again been overwhelmingly emotional for me’.Given the shrine-like setting of the museum’s final exhibit – King’s room has beenrendered as a replica of what it may have looked like at the time of his murder –such comments reflect the NCRM’s goal of registering an emotional impact amongvisitors.

Deficient Surrogation

In contrast to the relative paucity of concern over excessive surrogation, respondentsat both the NCRM and Laura lodged numerous comments related to deficient surroga-tion. Primary among them were assessments of the accuracy of each site’s narrative.These criticisms were typically expressed as a palpable desire for exact details andfactual accuracy. For instance, a question on the NCRM survey asked respondentsto comment on what topics deserved additional attention at the museum. A primaryconcern emerged that the NCRM’s main exhibit did not adequately address the fullspectrum of the Movement-era protest.

Add information regarding the Birmingham church burnings, the fate of theBlack Panthers, the riots of 1968 and their aftermath.

Black Panthers, Malcolm X and Nation of Islam only mentioned as sideline.Seemed somewhat obligatory.

More information on women, less ‘mainstream’ activists.

These comments express a desire to address what some respondents interpret asdeficiencies in the mainstream rendition of the Movement, in particular the mannerin which its retelling relegates radical elements to the fringe or ignores them alto-gether. The NCRM’s narration of the Movement is consonant with the ‘Great Man’paradigm of representing the past. This representational trope relies on biographyand consensus-oriented historiography (Dwyer and Alderman 2008a). In this vein,Martin Luther King Jr.’s life and death project a powerful surrogate for a generationof identity politics and anti-racist agitation. In lodging the complaint of deficientsurrogation, i.e. calling for different kind of Movement retelling, these respondentsare challenging the dominant Movement narrative. That visitors to the site of King’smurder seek out perspectives on the Movement that challenge its traditional mooringssuggests the extent to which perceptions of deficient surrogation are present.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ow

en D

wye

r] a

t 04:

19 2

9 Ju

ne 2

012

14 O. Dwyer et al.

At Laura, similar concerns over deficient surrogation were expressed by respon-dents as a desire to learn more about slavery.

I wanted to learn more about the slaves. I don’t think necessarily it was an equalmixture about the slave owners and the slaves themselves and their life on theplantation. We don’t know much about their life on the plantation because ofhow it was reported. But I really would like to know more about that. And takento and explained the slave quarters and how their life was in the slave quarters.

We didn’t get back into the slave quarters or any of that. I realize that theyare going to be developing that more and stuff like that. But other than a shortdescription about where they were at and a little about the fact that the slaveswere raised here and born here we really didn’t get much description. I wouldhave wanted more of that to get an aspect of what plantation life was like fromthe slave aspect of things.

In these cases, the desire for additional information about the experience of slav-ery directly implicates the landscape and material culture inasmuch as respondentsspecifically wish to view the housing and environs of the enslaved. Moreover, com-ments like these seeking a fuller surrogate contradict established patterns of marginalinclusion and outright erasure of African American experiences.

Other expressions of deficient surrogation at the NCRM and Laura suggest a desireon the part of respondents to acknowledge the site’s narrative in terms of its politicalimplications. In these cases, the surrogate was judged insufficient on the groundsthat it failed to make manifest the connections between the past and present. Theserespondents couched their comments in terms of the extent to which a site was relevantnow and would be in the future. For instance, at the NCRM respondents commented:

The video’s exhortation ‘every man, woman, and child . . . ’ is not enough –what are people’s political options now? More information on concurrent socialmovements and their interaction with the Civil Rights Movement.

I would like to see more information about hate crimes and intolerance today.I think that many people are not believing that still occurs today – and itdoes. I would also like to see more information about what people could dotoday against hate crimes and intolerance in the United States, especially inthe South, but throughout the world. I would also like to see more informationabout encouraging people to vote. I see a great deal of apathy in today’s worldparticularly in the United States but, in terms of voting, women and AfricanAmericans have not always had the right to vote and now that we do have thatright I think we need to exercise that right because that is our voice.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ow

en D

wye

r] a

t 04:

19 2

9 Ju

ne 2

012

Commemorative Surrogation 15

In an oblique manner, a respondent at Laura commented on the contemporarypolitics of remembering the colonial past, in particular the manner in which suchaspects are not thoroughly examined at Laura.

History has always been an awkward subject and I think every society, espe-cially the Western ones, have to admit that our own histories have nasty aspectsof it. Some of the main Bristol ports, Liverpool and Bristol, paired their busi-ness with slavery. The same with the Southern states as a whole. And it’s beenvery slightly, how should we put it, sanitized. What happened was nasty but ithappens. I think if we admit to it everybody is much happier. So, again back inthe U.K. we have finally admitted that Bristol and Liverpool were built on thisproduct, and you learn to accept it, make the best of a very bad job and get onwith things. I think like was said that is probably what happened here and thatmeans all the gory details and some might be salacious or something like that,but the fact it did happen can’t be mentioned.

Likewise, a single African American respondent at Laura noted the absence ofslavery related information.

It was very good. We had a really good time, but I would recommend maybesome African–American perspectives concerning more about our culture onthe plantation, the life of the slaves.

From the perspective of surrogation, these comments suggest an attitude on thepart of visitors that sites like Laura and the NCRM are not so much repositories fora past that is settled and known but rather vantage points from which to assess anactive, involved and on-going exploration of history. The respondents’ call for payingadditional attention to the implications of slavery may be interpreted as a search forcues to action that address contemporary situations and concerns.

Among the most voluminous expressions of deficient surrogation, respondentsexpressed concerns about a perceived lack of immediacy and interactivity in theexhibits, e.g. too much passive text and required reading. For instance, a respondentto the NCRM wrote:

The exhibit requires a lot of reading which makes it less accessible to thosewho cannot read well or not at all, as well as to children. Can be overwhelmingeven for a masters prepared person!

Other commented on the ‘overwhelming’ condition of the exhibit, raising a concernthat the exhibit falls short of presenting a sufficiently engaging surrogate.

It is important to make the exhibits more interactive. Presentation is importantand the extensive amount of written exhibits only can seem overwhelming.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ow

en D

wye

r] a

t 04:

19 2

9 Ju

ne 2

012

16 O. Dwyer et al.

More interactive exhibits. Although the museum was extremely interesting andeducational, the amount of required reading was almost cumbersome.

At Laura, a respondent suggested a similar level of disengagement, this time inrelation to the perceived shortcomings of the slave cabins.

I wasn’t interested in going out and looking around the slaves quarters sinceI didn’t feel there would be anything there at this time. Not that I wasn’tinterested, but I’m from Florida and I’ve seen similar plantations.

Finally, in several cases, visitors suggested that some of the representations weredeficient because they lacked accuracy or did not conform to their impression of thehistorical past. In the case of the NCRM, several respondents suggested changing thelife-sized diorama of the sanitation workers’ strike:

Garbage Strike – The truck was too ‘looming’ visually that it detracted fromthe seriousness.

Change mannequins in the exhibit to Brown or Black!!

The black statues should be portrayed as black rather than white.

Make black people instead of white mannequins.

These evaluations suggest that for some visitors, the visual sophistication andaccuracy of dramatic media, in this case a life-sized reproduction of striking workersand a garbage truck, is a matter of great concern.

At Laura, one respondent echoed the concern for accuracy in her comments aboutthe one-dimensional representation of the elite family detracted from the overalleffect.

It would have been nice to hear more about the slaves and that part of it. Thatconnection was made just at the end. It was a very pristine story of the family.

In this case, the charge of deficient surrogation is levelled against a representationjudged to be excessively tidy and redemptive.

Conclusion

The traditional absence and marginalisation of African Americans from the South’sheritage landscape is being challenged. Not only have Civil Rights-era museums andmemorials emerged but some plantation sites are also responding to criticism andmarket signals for a richer, more complex and ultimately more just representation ofthe region’s heritage. In keeping with the self-selecting nature of heritage tourism,audiences at these sites report an overall satisfactory experience. That said, inter-views and verbatim comments disclose a more critical perspective. Central to thesecriticisms is the concept of surrogation and the judgment that a heritage surrogate is

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ow

en D

wye

r] a

t 04:

19 2

9 Ju

ne 2

012

Commemorative Surrogation 17

either excessive or deficient. In the case of Laura, no comments were recorded thatsuggested visitor evaluations of excessive surrogation. Instead, respondents expresseddesires to learn more about the experience of enslavement, comments indicative ofdeficient surrogation. At the NCRM, respondents voiced opinions that resonated withboth excessive and deficient surrogation. These comments ranged from calls for moreaccurate dioramas to less emphasis on the KKK. These criticisms express concernsabout the condition of the site’s narrative and its political implications. Thus, the con-cept of surrogation provides a powerful lens for evaluating respondents’ comments,one that highlights the extent to which these sites serve as arenas for jostling over thepolitical implications of memorial narratives. In effect, surrogation provides a cipherfor analysing audience reactions to racialised narratives, one that acknowledges themanner in which audiences write and re-write heritage venues via their interpretations.

The impressions that emerge from this comparison of visitors and their reactionsto the NCRM and Laura simultaneously challenge and confirm established norms inSouthern heritage tourism. In both cases, the majority of visitors are well-educatedwomen. Both groups seek out these sites, typically travelling from well outside theregion. The relative youth of visitors to the NCRM, however, suggests a differentkind of attraction. African Americans visit civil rights museums with families andchildren in tow, presumably seeking out lessons from the past. For them, the NCRMfunctions as a heritage site, i.e. a place of instruction and guidance. In contrast,plantation museums attract an older white audience with almost no children in atten-dance. This demographic profile conforms to established norms associated with theclassic aesthetic tourist in search of good taste and experience. In the case of Laura,however, there is a significant twist: respondents here offered comments seeking amore frank exploration of race, racism and slavery. The difference suggests that siteslike Laura are tapping into an audience ready to engage sophisticated surrogatesassociated with slavery. It may be the case that Laura is evolving, however haltingly,into a site that bridges the gap between entertainment attraction and heritage site.

Given the age of these results presented here and the uncoordinated nature of theircollection, it is important not to claim too much. Since their collection, the UnitedStates has elected its first African American president and a memorial to MartinLuther King, Jr., has been dedicated on the national Mall. That said, these results –however modest – represent the only extant data and analysis of their kind on thesubject. They testify to the contingent transformation of Southern heritage tourism.In addition, these results advance the shared interest on the part of cultural geographyand tourism studies in the more-than-representational experience of landscape andcollective memory.

Finally, this article’s application of the concept of surrogation to the consumption ofheritage representations, responds to calls by those interested in cultural landscapes toattend to both the production and consumption of the experience of landscape (Wiley2007). In the past, critical studies of heritage tourism have carefully examined theindustry’s production and site representation. The publication of studies of audience

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ow

en D

wye

r] a

t 04:

19 2

9 Ju

ne 2

012

18 O. Dwyer et al.

reaction and evaluation – studies that add to the routine collection of visitor originationcoordinates – signal the robust quality of work being undertaken by geographers andtourism researchers. Visitor reaction studies that consider variation among era, theme,and geography associated with different heritage sites mark an important step in thefield’s maturation.

The concept of surrogation provides a valuable way of conceptualising and eval-uating the evaluations of tourists as they react to the perceived excesses and deficitsof heritage representations. It appears that audience criticisms of excessive and de-ficient surrogation can be grouped into three types: specific concerns about a site’snarrative, its political implications, and the physical experience of interacting withthe site. Whereas the initial focus of surrogation studies has been the text associatedwith a memorial (Alderman 2010), the concept of the surrogate is nuanced enoughto inform an analysis of the manner in which a heritage site is an arena for politicaljostling and the performative aspects of collective memory. These additional aspectsof surrogation correspond to the predominant metaphors identified among the workof geographers studying heritage places (Dwyer & Alderman 2008b). This overlapbetween visitor reactions and geographers’ analogical frames suggests rich potentialfor cultural landscape studies to enhance its traditional study of heritage sites: the fo-cus on ‘author’ and ‘text’ may be enhanced by a careful examination of the ‘readers’of the past.

References

Alderman, D. H. (2006) Street names as memorial arenas: The reputational politics of commemoratingMartin Luther King in a Georgia county, in: R. Romano & L. Raiford (Eds) The Civil RightsMovement in American Memory, pp. 67–95 (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press).

Alderman, D. H. (2010) Surrogation and the politics of remembering slavery in Savannah, Georgia (USA),Journal of Historical Geography, 35(1), pp. 1–12.

Alderman, D. H. & Campbell, R. M. (2008) Symbolic excavation and the artifact politics of remember-ing slavery in the American South: Observations from Walterboro, South Carolina, SoutheasternGeographer, 48(3), pp. 338–355.

Alderman, D. H. & Modlin, E. A., Jr. (2008) (In)visibility of the enslaved within online plantation tourismmarketing: A textual analysis of North Carolina websites, Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing,25(3/4), pp. 265–281.

Algeo, K. (2012) Underground tourists/tourists underground: African American tourism to Mam-moth Cave. Tourism Geographies, DOI: 10.1080/14616688.2012.675514, Available at http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/14616688.2012.675514 (accessed 13 April 2012).

Armada, B. J. (1998) Memorial agon: An interpretive tour of the national civil rights museum, SouthernCommunication Journal, 63(3), pp. 235–243.

Butler, D. L. (2001) Whitewashing plantations: The commodification of a slave-free antebellum South,International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration, 2(3/4), pp. 163–175.

Butler, D.L. (2002) The Laura Creole plantation tourist survey: A preliminary report, unpublished demo-graphic market survey.

Butler, D. L., Carter, P., & Dwyer, O. J. (2008) Imagining plantations: Slavery, dominant narratives, andthe foreign born, Southeastern Geographer, 48(3), pp. 288–302.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ow

en D

wye

r] a

t 04:

19 2

9 Ju

ne 2

012

Commemorative Surrogation 19

Brundage, W. F. (Ed) (2000) Where These Memories Grow: History, Memory, and Southern Identity(Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press).

Brundage, W. F. (2005) The Southern Past: A Clash of Race and Memory (Cambridge, MA: BelknapPress).

Buzinde, C. N. & Santos, C. A. (2009) Interpreting slavery tourism representations, Annals of TourismResearch, 36(3), pp. 439–458.

Dann, G. M. S. & Seaton, A. V. (2002) Slavery, Contested Heritage, and Thanatourism (London:Routledge).

Dwyer, O. J. (2000) “A Survey of Visitors to Four Civil Museums,” unpublished demographic marketsurvey undertaken for the Martin Luther King, Jr., National Historic Site in Atlanta; the BirminghamCivil Rights Institute; the National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis; and the National Voting RightsMuseum in Selma.

Dwyer, O. J. (2002) Location, politics, and the production of civil rights memorial landscapes, UrbanGeography, 23(1), pp. 31–56.

Dwyer, O. J. & Alderman, D. H. (2008a) Civil Rights Memorials and the Geography of Memory (Athens:University of Georgia).

Dwyer, O. J. & Alderman, D. H. (2008b) Memorial landscapes: Analytic questions and metaphors,GeoJournal, 73(3), pp. 165–178.

Eichstedt, J. L. & Small, S. (2002) Representations of Slavery: Race and Ideology in Southern PlantationMuseums (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press).

Fine, G. (2001) Difficult Reputations: Collective Memories of the Evil, Inept, and Controversial (Chicago,IL: University of Chicago Press).

Handler, R. & Gable, E. (1997) The New History in an Old Museum: Creating the Past at ColonialWilliamsburg (Durham, NC: Duke University Press).

Hanna, S. (2008) A slavery museum? Race, memory, and landscape in Fredericksburg, Virginia, South-eastern Geographer, 48(3), pp. 316–337.

Hoelscher, S. (2003) Making place, making race: Performances of whiteness in the Jim Crow South,Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 93(3), pp. 657–686.

Hoelscher, S. (2006) The white-pillared past: Landscapes of memory and race in the American South, in:R. Schein (Ed) Race and Landscape in America, pp. 39–72 (New York: Routledge).

Horton, J. & Horton, L. (Eds) (2006) Slavery and Public History: The Tough Stuff of American Memory(New York: The New Press).

Inwood, J. & Martin, D. G. (2008) Whitewash: White privilege and racialized landscapes at the Universityof Georgia, Social and Cultural Geography, 9(4), pp. 373–395.

Jones, J. P., III (2000) The street politics of Jackie Smith, in: G. Bridge & S. Watson (Eds) The BlackwellCompanion to the City, pp. 127–135 (Oxford: Blackwell Publishers).

Lambert, D. (2007) ‘Part of the blood and dream’: Surrogation, memory, and the national hero in thepostcolonial Caribbean, Patterns of Prejudice, 41(3/4), pp. 345–371.

Modlin, E. A., Jr. (2008) Tales told on the tour: Mythic representations of slavery by docents at NorthCarolina plantation museums. Southeastern Geographer, 48(3), pp. 265–287.

Modlin, E. A., Jr., Alderman, D. H., & Gentry, G. W. (2011) Tour guides as creators of empathy: The roleof affective inequality in marginalizing the enslaved at plantation house museums, Tourist Studies,12(1), pp. 1–17.

Post, C. (2009) Reputational politics and the symbolic accretion of John Brown in Kansas, HistoricalGeography, 37, pp. 92–113.

Radford, J. (1992) Identity and tradition in the post-Civil War South, Journal of Historical Geography,18(1), pp. 91–103.

Roach, J. (1996) Cities of the Dead: Circum-Atlantic Performance (New York: Columbia University Press).Romano, R. C. & Raiford, L. (2006) The Civil Rights Movement in American Memory (Athens: University

of Georgia).

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ow

en D

wye

r] a

t 04:

19 2

9 Ju

ne 2

012

20 O. Dwyer et al.

Savage, K. (1997) Standing Soldiers, Kneeling Slaves: Race, War, and Monument in Nineteenth-CenturyAmerica (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press).

Schein, R. (2006) Landscape and Race in the United States (New York: Routledge).Schein, R. (2009) Belonging though land/scape. Environment and Planning A, 41(4), pp. 811–826.Wiley, J. (2007) Landscape (New York: Routledge).

Notes on Contributors

Owen Dwyer is an associate professor at Indiana University’s urban campus inIndianapolis. He studies cultural geographies of landscape, cartography, and memory.

David Butler is an associate professor in the Department of Political Science, In-ternational Development, and International Affairs at The University of SouthernMississippi. His interests are in representations of the enslaved at tourism plantationmuseums within the narrative and the expectations of tourists.

Perry Carter is an associate professor in the Geosciences Department at Texas Tech.His general interests include human, social, urban and economic geography. Specificinterests include geographies of consumption, travel, and tourism, space and its rolein the construction of racial identity, and geographic methodologies.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ow

en D

wye

r] a

t 04:

19 2

9 Ju

ne 2

012