Changing principals’ leadership through feedback and coaching

Transcript of Changing principals’ leadership through feedback and coaching

Changing principals’ leadershipthrough feedback and coaching

Peter GoffEducational Leadership and Policy Analysis, University of Wisconsin-Madison,

Madison, Wisconsin, USA

Ellen Goldring and J. Edward GuthrieLeadership, Policy, & Organizations, Vanderbilt University,

Nashville, Tennessee, USA, and

Leonard BickmanPsychological Sciences, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee, USA

Abstract

Purpose – In this study the authors use longitudinal data from a randomized experiment toinvestigate the impact of a feedback and coaching intervention on principals’ leadership behaviors.The paper aims to discuss these issues.Design/methodology/approach – In total, 52 elementary and middle school principals (26 receivingteacher feedback, 26 receiving feedback and coaching) were randomized into a year-long feedback andcoaching study. Measures of leadership actions were collected from principals and teachers during thefall, winter, and spring. The authors use instrumental variables approach to examine the impact oftreatment.Findings – Behavioral change may take longer than is presented in this study, which implies thatthese findings represent a lower-bound. As an intervention leadership coaching is costly and thisresearch does not explore alternatives to help principals make feedback data actionable.Practical implications – It is unlikely that providing school leaders with feedback alone will inducebehavioral change. Other systems and supports – such as leadership coaching – are needed to helpprincipals make sense of feedback data and translate data into actionable behaviors.Originality/value – Few leadership studies use exogenous variation in treatment conditions toexamine leadership outcomes. This study builds upon our causal knowledge of leadership behaviorsand presents a viable intervention to improve school leadership.

Keywords Coaching, School leadership, Instrumental variables, Learning-centered leadership,Randomized design, Teacher feedback

Paper type Research paper

IntroductionAs the focus of educational reform increasingly centers on school-level performance,research and policy attention have turned to the quality of principals as a potentialpivot point for school improvement (Robinson, 2007). Belief in the primacy of effectiveschool leadership has been expressed by, among others, US Education Secretary ArneDuncan, who states “there’s no such thing as a high-performing school without a greatprincipal [y] You simply can’t overstate their importance in driving student

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available atwww.emeraldinsight.com/0957-8234.htm

Received 19 October 2013Revised 17 February 20141 May 20142 May 2014Accepted 6 May 2014

Journal of EducationalAdministrationVol. 52 No. 5, 2014pp. 682-704r Emerald Group Publishing Limited0957-8234DOI 10.1108/JEA-10-2013-0113

This paper is supported by grant R305A070298 to Leonard Bickman from the US Department ofEducation’s Institute of Education Sciences. Funding for Peter Goff was provided by an IESgrant through Vanderbilt’s Expert program for doctoral training (R305B040110). All opinionsexpressed in this paper represent those of the authors and not necessarily the institutions withwhich they are affiliated or the US Department of Education. The authors thank Se Woong Leefor assistance in preparing this manuscript.

682

JEA52,5

Dow

nloa

ded

by C

opyr

ight

Cle

aran

ce C

ente

r A

t 13:

28 2

1 A

ugus

t 201

4 (P

T)

achievement, in attracting and retaining great talent to the school” (Connelly, 2010, p.35). Yet there is a perceived lack of well-qualified leaders who are equipped with theknowledge and skills to improve student performance (Darling-Hammond et al., 2009).There are two mechanisms by which we might improve the quality of school leaders:first, selection, consisting of a combination of dismissing low-performers andimproving the quality of individuals applying for and hired to administrative positionsand second, development, of the capacity of existing principals. This paper focusseson the latter option: improving schools by building the leadership skills of currentschool leaders.

In order to improve within their complex roles, principals need a valid and reliablesystem of feedback from which to understand and enhance their leadership (Goldringet al., 2009b). However, few principals find feedback from their existing evaluationprocesses helpful or inspiring, arguably because performance feedback is seldommore than ritualistic and perfunctory evaluation (Thomas et al., 2000). Even whenprovided with valid and detailed feedback, such information may not be enough tochange principal behavior in meaningful ways. Many principals fall into a pattern offocusing on positive elements of feedback to strengthen their existing self-conceptwhile denying or rationalizing negative feedback (Hattie and Timperley, 2007; Thomaset al., 2000).

The challenges of translating leadership feedback into practice are not uniqueto education. In the private sector, coaching has been coupled with feedback to helpgive business leaders a better understanding of subordinate feedback (Thach andHeinselman, 2000). In these cases, coaches are able to help leaders receive criticismand to understand how to make their employees’ feedback actionable. Such successfulcoaching models in the private sector offer hope for similar results in educationalsettings (Kombarakaran et al., 2008; Bowles et al., 2007; Thach, 2002). Showersand Joyce (1996) found that without coaching only 5-15 percent of learning hasbeen transferred from staff development programs into classroom teaching.Darling-Hammond (2010), found that principals’ most preferred form of professionaldevelopment is coaching, despite little experience with it. Although surprisinglylittle empirical support for the efficacy of coaching yet exists, many practitionersand scholars recommend coaching as a viable tool for improving principals’ leadership(Wise and Jacobo, 2010).

Few studies are able to document how school leadership changes in responseto various developmental efforts (Darling-Hammond et al., 2007; Marzano et al., 2005;Huber, 2004). While cross-sectional studies can provide insights into how principalsengage developmental programs (Patten, 2006), to examine how leadershipbehaviors and perspectives change as a result of intervention requires more scarcelongitudinal data.

This study uses a multiyear, randomized experiment to investigate the impact offeedback and coaching intervention on urban principals’ leadership behavior andperspectives. This study is based on a theoretical framework suggesting that behavioris enhanced when feedback is combined with coaching. For this study, we developedand implemented an approach to principal development that combines both feedbackto principals from their teachers with coaching sessions specifically tailored todevelop learning-centered leadership (LCL) skills. The question we address in thispaper is: does the amount of coaching, when combined with feedback from teachers,change principals’ leadership practices, relative to those principals who receivefeedback alone?

683

Changingprincipals’leadership

Dow

nloa

ded

by C

opyr

ight

Cle

aran

ce C

ente

r A

t 13:

28 2

1 A

ugus

t 201

4 (P

T)

The role of feedback in leadership developmentOver several decades, the term feedback has been articulated in many different ways.Hattie and Timperley (2007, p. 102) define feedback as “information provided by anagent (e.g. teacher, peer, book, parent, self, or experience) regarding aspects of one’sperformance or understanding [y] feedback is thus a consequence of performance.”In order to inform goal setting and to direct behavioral change, feedback must containmeaningful information that leaders perceive to be both valid and reliable (Portin et al.,2009). Multisource feedback, a feedback approach popularized in the private sector, iscomposed of a leader’s self-assessment as well as assessments from subordinates,peers, and/or superiors (Moore, 2009). The integration of subordinate feedback in themulti-source process facilitates communication (Tornow and London, 1998) and servesas a validity check (Smither et al., 2005). Furthermore, by using subordinate feedback,leaders can acknowledge their practices (e.g. Hesketh et al., 2005) and improve overallperformance (Walker and Smither, 1999; Kluger and DeNisi, 1996).

While the majority of extant research on feedback between employees andemployers comes from business settings, several studies have dealt with the useof feedback to support principals in education. Through a meta-analysis Hattie(1999) found that feedback (from teachers to leaders, from leaders to teachers, or fromstudents to teachers) was one of the top five factors influencing student achievement.Among the limited research that has focused on feedback in the education field, mosthas focussed on the teacher-student feedback loop, not teacher feedback as a means toenhance principals’ leadership. This is mainly because, in practice, principals rarelyreceive systematic feedback regarding their performance and, therefore, remain blindabout their practice (St. Martin, 2010). Considering that principals drive schoolimprovement (Bryk et al., 2010), providing systematic and valid feedback to principalsis a cornerstone of leadership development (Marks and Printy, 2003). Receptivityto critical feedback, meaningful interpretation of feedback data, and setting actionablegoals based on feedback are attributes and skills that mediate the utility of a leadershipfeedback system (Bickman et al., 2006). To develop these attributes and skills thatmaximize the potential of leadership feedback, additional systems, such as coaching,may be needed.

CoachingEven though feedback is essential in improving leadership, it alone may be insufficientto change one’s behavior (Cannon and Witherspoon, 2005). Leaders need adequatesupport in order to interpret feedback correctly and change their behavior (Alickeand Sedikides, 2009). Coaching can help leaders reflect adequately on their particularexperience, which few leaders find easy (Bloom, 2004). Peterson and Hicks (1996)define coaching as a “process of equipping people with the tools, knowledge, andopportunities they need to develop themselves and become more effective” (as citedby Feldman and Lankau, 2005, p. 841). Also, researchers noted that “[c]oaching is nowemerging as one of the most significant approaches to the professional developmentof senior management and executives” (Gray, 2006, p. 475). That is in part why at least59 percent of major companies currently offer coaching (London, 2001) and 70 percentof organizations prefer coaching as a major leadership development (Zenger andStinnett, 2006). These promising findings not withstanding, the empirical literatureprovides little evidence as to the duration and dose of coaching required to be effective.Since leadership coaching in the private sector tends to be focussed on thoseindividuals with substantial motivation and promise, it is unclear how the returns to

684

JEA52,5

Dow

nloa

ded

by C

opyr

ight

Cle

aran

ce C

ente

r A

t 13:

28 2

1 A

ugus

t 201

4 (P

T)

coaching may differ when coaching is available to all leaders or assigned to strugglingor novice leaders.

As compared to consulting, coaching has emerged fairly recently in leadershipdevelopment (Schein, 2010). However, unlike consulting, coaching facilitates the client’sactive engagement, learning, and internal commitment to a course of action (Bacon andSpear, 2003). A coach is a highly skilled professional who help leaders to be awareof the problem or situation and help leaders to set goals to resolve the problem.There is no rule of thumb on how coaches engage but there are steps and phasescoaches follow. The basic phases in a coaching engagement are: groundwork, whichinvolves building relationships base on trust; assessment and feedback, whichinvolves helping principals to understand feedback and explore its meaning;goal-setting, which involves assisting principals to select a meaningful target forchange; action planning, in which, designing a specific path or set of concrete stepsthat, if followed, will lead to achievement of the goal; and ongoing assessment andsupport, which involves measuring progress over time, addressing any challengesthat emerge, providing encouragement and support to build motivation, and keepingthe principal on track (Goldring et al., 2010; Whitmore, 2004) The key goals of thesesteps are to monitor how progress is being made and maintained and to sustainchange, building on positive changes over time in a process of continual improvement.

Coaching requires directed focus and has shown more promising effects whencoupled with feedback. Leaders who worked with coaches following feedbackimproved more than those who did not work with coaches (Smither et al., 2006). Aboveall, coaching helps individuals to deal with negative feedback more constructively(Brett and Atwater, 2001). Thach (2002) found that the combination of feedback andcoaching increased leadership effectiveness by up to 60 percent. This is one reasonthat the combination of feedback with coaching has become one of the fastestgrowing leadership development strategies in private sector (American ManagementAssociation, 2008; Luthans and Peterson, 2004).

Many scholars in education believe that coaching can also help school leaders toenhance their leadership in order to improve schools and elevate districts to higherlevels of achievement (Thach, 2002). In the past several years, there has been a growinginterest in principal coaching as a significant component of principal professionaldevelopment (Hobson, 2003; Reiss, 2006). Unlike other professional developmentprograms, coaching can respond to the needs of the principal directly and enhancetheir ability to solve the complex problems they face every day (Neufeld and Roper,2003). Despite increased interest in principal coaching there remains little empiricalevidence to support the use of leadership coaching in school settings. Thus, Grant(2003) concluded that more research is needed to demonstrate the effectivenessof leadership coaching. One example of this need is that the dose of coaching canimpact the effectiveness (Reeves, 2009). Wise (2008) found that principals receive anaverage of two to four hours of coaching per month, which is o2 percent of theaverage principal’s time at work. In order for coaching to be a catalyst of changesufficient time with coaches has to be guaranteed (Wise and Jacobo, 2010).

To date there have been few rigorous research endeavors to identify the efficacy ofleadership feedback and coaching in education. Primarily owing to the highimplementation costs associated with leadership coaching, we contrast the effect ofleadership feedback in combination with coaching to the effect of feedback alone.In this paper, we use a randomized experiment with data collected at three points overthe school year to explore changes in teachers’ perceptions of principals’ actions as well

685

Changingprincipals’leadership

Dow

nloa

ded

by C

opyr

ight

Cle

aran

ce C

ente

r A

t 13:

28 2

1 A

ugus

t 201

4 (P

T)

as principals’ perceptions of their own actions as a result of feedback and coaching.The central question addressed by this study is: does coaching, together with feedbackfrom teachers, change principals’ leadership practices relative to those who onlyreceive feedback? We explore the extent to which coaching changes the specific actionsprincipals take with their teachers in regard to instructional leadership tasks, and theextent to which principals share and use the feedback in their own leadership work.

The content and mechanism of feedback and coachingThere is substantial evidence that instructional leadership correlates with effectiveteacher practices and student achievement. Research reports that school leadershipis mediated by school operations and classroom activities through teachers (seeLeithwood et al., 2003). A meta-analysis of 70 empirical studies found the average effectsize of the perception of school leadership on student achievement to be approximately0.25 (Waters et al., 2003). In a review of 30 years of studies using surveys ofinstructional management, Hallinger (2010) found consistent positive relationshipsbetween leadership behaviors and teacher practices. Similarly, Robinson et al. (2008)use the results of 22 studies to compare the relationship between instructionaland transformational leadership and student outcomes and conclude the averageeffect of instructional leadership is three to four times greater than the effect oftransformational leadership on student outcomes.

More recently the term LCL has expanded upon the notion of instructionalleadership. LCL includes aspects of school leadership that go beyond theinstructional program of the school and highlight the importance of the focus ofprincipals’ actions on supporting teachers to improve instruction, focusing schoolsgoals’ on high standards and a rigorous curriculum, allocating resources alignedwith teaching and learning, and developing commitment to shape the organizationalculture (Goldring et al., 2008; Leithwood, 1994). LCL, can be summarized as follows:“the more leaders focus their relationships, their work, and their learning on the corebusiness of teaching and learning, the greater their influence on student outcomes”(Robinson et al., 2008, p. 636). Given the research base on instructional and LCL,feedback and coaching aligned to these leadership tasks is most likely to improveschool leadership. We focus on tasks that are the instructional leadership work ofleaders such as reviewing student achievement data with teachers, and helpingteachers choose professional development to support their improvement.

But how might feedback and coaching in the areas of instructional leadershipimprove principal leadership? There are three plausible mechanisms that can helpexplain how and why feedback and coaching can influence leadership behavior. Thefirst, logistic effects, suggests that feedback that pertains to a group of employees, suchas group of teachers, may be more easily acted upon by the leader for logisticalreasons, and therefore principals may act upon feedback that is more general to theorganization than specific. From a distributed leadership perspective we may expectprincipals to work with teams of teachers rather than engaging in one-on-onedialogues with each teacher in the school (Spillane et al., 2001). Principals that canwork with work groups of teachers may feel they have more opportunities and time toinfluence the outcome; leaders can coordinate the work more efficiently in engagingwith small groups. A second mechanism is a focus effect. This explanation is directlyrelated to coaching, namely that coaches may help principals focus their strategicefforts based on feedback to specific areas or domains of need, or to particular groupsof teachers. Simply put, feedback and coaching may provide actionable information for

686

JEA52,5

Dow

nloa

ded

by C

opyr

ight

Cle

aran

ce C

ente

r A

t 13:

28 2

1 A

ugus

t 201

4 (P

T)

strategic, focussed action. Lastly, the literature suggests a dissonance factor inunderstanding the effects of feedback and coaching. The fundamental premise behinda dissonance explanation is that a discrepancy or dissonance between behavior anda standard increases motivation to reduce the dissonance by bringing evaluationsfrom others in line with self-view. The comparison between self-ratings and feedbackfrom others can challenge behavioral patterns and provide motivation to rethinkbehavior and its impact on others (McCauley and Moxley, 1996). Festinger (1957)argues that dissonant cognitions induce a psychologically uncomfortable state ofarousal that provides the motivation to seek to reduce the dissonance. Thus we alsofocus on the extent to which principals generally engage with the feedback for goalsetting and development.

Given the paucity of research on feedback and coaching in general and in schoolsin particular, this study explores the plausibility of each of the three explanatorymechanisms in light of the empirical results in the discussion.

InterventionThis section describes the study design, participants of the study, feedback collectionand reporting, and the leadership-coaching model. This study uses a randomizedexperiment to investigate the impact of feedback and coaching intervention on urbanprincipals’ leadership behavior. The research presented here is part of a larger studythat was constructed using a delayed treatment design, where principals receivefeedback only for one year and the next year principals receive both feedback andcoaching. This design allowed all participants to engage with one year of feedbackand one year of feedback coupled with leadership coaching.

As noted above, the literature distinguishes between two different types ofcoaching: performance-based coaching that focuses on specific practices and/orattainment of benchmarks, and in-depth coaching that focusses on a client’s deepercognitive or psychoanalytical issues (Koonce, 1994; Thach and Heinselman, 2000). Inthis research we focus on performance-based coaching and we implementeda five-phase model of coaching to capture the key paths that principals follow withtheir coaches to understand feedback and make meaningful changes in their leadershippractices (Mavrogordato and Cannon, 2009). The basic phases in this model are:groundwork, assessment and feedback, goal-setting, action planning, and ongoingassessment and support (Whitmore, 2004). Topics discussed included more generalareas such as developing trust and communicating with teachers to discuss thefeedback, to specific areas, such as helping teachers set goals for individual studentsand monitor improvement (see Huff et al., 2013).

After agreeing to participate in the study and prior to receiving any leadershipfeedback or coaching, participating schools were matched into most-similardyads based on factors such as school demographics, achievement, and principalcharacteristics as determined by baseline survey measures. Each school in the dyadwas then randomly assigned to control or treatment. Randomization was conductedusing a pseudo-random number generator as the basis for randomization.Post-randomization checks using the above matching variables confirmed that therewere no significant differences between groups across measures.

During year 1 all participants completed LCL surveys as the basis for feedback,with only the treatment group receiving feedback reports based on these surveys. Inyear 2 all participants completed the LCL surveys, and responded to a set of actionitems, and all participants received feedback reports, with the treatment group now

687

Changingprincipals’leadership

Dow

nloa

ded

by C

opyr

ight

Cle

aran

ce C

ente

r A

t 13:

28 2

1 A

ugus

t 201

4 (P

T)

receiving leadership coaching. In this paper we examine how specific leadershipactions of the treatment and control conditions differ during year 2 of the above study.Principals in the treatment group received feedback with coaching while the controlgroup received only feedback.

ParticipantsOur experiment was implemented in a large urban school district in the SoutheasternUSA. We excluded high schools as well as schools for specific student populations(e.g. alternative schools, special education, charter schools) due to the organizationalcomplexities or unique contexts of these institutions. All of the remaining 108 regularelementary or middle schools were invited to participate; 76 principals agreed toparticipate. Over the course of the summer, five principals were relocated into schoolsthat were ineligible to participate in the study, such as special education schools;the remaining 71 principals were randomly assigned to the treatment and controlgroups. Of these 71 schools, 19 were dropped in the second year due to principals whoretired, changed schools, or declined to participate further in the project for personalreasons[1].

We draw from data collected during the second year of the project in which atreatment group of 26 principals received both coaching and feedback while the 26principals in the control group received only teacher feedback. It is in this secondyear of the study that a set of action items (described in the following section) wasadded to the survey instrument. Teacher response rates were comparable for controland treatment groups (85.49 and 85.85, respectively).

In our sample principals had been leaders at their current schools an average of 2.4years and had been principals in the same school district an average of 5.6 years. In all,77 percent of school principals were female and 42 percent were white. In all, 50 percentof teachers had less than five years of teaching experience in the school and less thanten years of experience as a teacher; 42 percent of teachers currently hold or have helda leadership position within the school, such as department chair. Similar to nationaltrends in elementary schools, teachers were predominantly female (86 percent) andwhite (73 percent).

The average percentage of students in the free and reduced price lunch programwas 68 percent. Furthermore, 88 and 85 percent of students were proficient oradvanced on their standardized test in reading and math, respectively.

FeedbackFor this study, the project team developed and implemented a new approach toprincipal development that entails feedback to principals from their teachers. Data forthe feedback were collected through surveys taken in the fall, winter, and spring of theacademic year. In these surveys teachers reported principals’ leadership effectivenessacross a number of measures, including a modified 36-item LCL scale, which wasadapted from the Vanderbilt Assessment of Leadership in Education (VAL-ED)(Goldring et al., 2009a; Murphy et al., 2011), and the effective leadership action items,from which we develop the dependent variables of this study. Principals, in turn,completed parallel surveys reporting their own leadership practices. The surveys werecompiled into feedback reports and sent to principals and their coaches. These actionitems were anchored by and aligned with the Interstate School Leaders LicensureConsortium (ISLLC) standards and VAL-ED assessments. The VAL-ED measures theperceived effectiveness of leadership behaviors that have been shown to influence

688

JEA52,5

Dow

nloa

ded

by C

opyr

ight

Cle

aran

ce C

ente

r A

t 13:

28 2

1 A

ugus

t 201

4 (P

T)

teachers’ performance and their students’ learning (Porter et al., 2010; Goldring et al.,2009a). The instrument focusses on instructional leadership behaviors such asimproving the quality of instruction, holding the school to rigorous standards,implementing data use and accountability, and engaging parents on a five-point scalefrom ineffective to outstandingly effective. The instrument was modified to shortenit for the purposes of this study. The items measured are based on the instructionalleadership literature and are aligned with the ISLLC (Goldring et al., 2009a; Porter et al.,2010). The VAL-ED has undergone psychometric development and testing (see Porteret al., 2010) and is in use in thousands of schools across the USA.

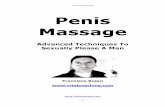

The instrument relies on multisource feedback, a self-assessment of the principal aswell as parallel ratings from teachers in the school. The motivation behind multisourcefeedback is that more information regarding leadership efficacy resides within theshared experiences of these individuals than from any one source alone, and it can thenfacilitate communication and strategic focus (Atwater et al., 1998; Goldring et al., 2013).Feedback reports provided to principals summarized data collected from their facultyand contrasted these measures against principals’ self-perceptions, responses fromother principals, and responses from other teachers in the study. Figure 1 presentsan excerpt from a feedback report. The report conveys feedback to principals usinggraphs, tables, and textual narratives.

Action-items were a primary component of the feedback principals received fromteachers in the intervention in year 2, as well as discussion and data points for thecoaching sessions. Principals received feedback reports after every wave of data

Ineffective

Lear

ning

-Cen

tere

dLe

ader

ship

Effe

ctiv

enes

s -

Dis

tric

t Com

paris

on

Lear

ning

-Cen

tere

dLe

ader

ship

Effe

ctiv

enes

s -

You

r S

choo

l

% S

choo

ls

Ineffective1

10

0

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

10

0

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

2 3 4 5

1 2 3 4 5

Your RatingTeacher Avg

Overall Teacher Avgacross Schools

Overall Principal Avg

OutstandinglyEffective

OutstandinglyEffective

Figure 1.Sample feedback

689

Changingprincipals’leadership

Dow

nloa

ded

by C

opyr

ight

Cle

aran

ce C

ente

r A

t 13:

28 2

1 A

ugus

t 201

4 (P

T)

collection; three times over the academic year corresponding to year 2 of the study.Teacher surveys were completed by 1,779 teachers within 52 schools. On average,34 teachers per school provided feedback data with a response rate of 86 percent.

CoachingThe leadership coaches selected for this study were former educational administratorsand instructional leaders specifically trained for school leadership coaching.Principals selected for treatment (coaching and feedback) met two to four timesbetween each wave of survey collection. Each session focussed on feedback fromteacher surveys and ranged from 40 to 90 minutes in duration. Coaches were notlimited to a set of procedures or protocols for each session but rather focused ondeveloping goals, interpreting feedback, and motivating principals to take action,Coaches were assigned based on geographic location in order to encourage frequentcoaching sessions.

MeasuresIt was during year 2 that “action items” were added to the LCL feedback surveys tocollect data regarding the dependent variable in this study. In contrast with the globalLCL items, these action items were designed to represent specific, concrete behaviorsthat leaders may engage as a result of receiving feedback and/or coaching thatare aligned with instructional leadership tasks. For example, for the ratings ofeffectiveness of LCL concepts of the VALED, such as data-based decision making, theaction items asked about more pointed specific leadership actions or behaviors inresponse to a particular area of instructional leadership (see Table I). Some of the actionitems referred to overall use of the feedback, such as setting goals. The psychometricproperties associated with their scaling were developed using factor analyses.

We rely on multilevel exploratory factor analysis (EFA) to identify the underlyingfactor structure of the action-item data in order to reduce the relatively large scale intoempirically supported subscales representing latent domains of leadership behavior.By modeling a multilevel factor structure we are able to separate the systematicdifferences between principals (between-level) while accounting for the clustering ofresponses by teachers providing feedback on the same principal (within-level). In ourlater analyses, we test the effects of principal coaching on teacher responses. It istherefore the covariance of teacher responses represented by the within-level EFAresults, which we use to develop our dependent variables.

We conducted our factor analysis on the action-items responses of the second-yearteacher survey from the fall data collection, shown in Table I. Supplemental analysesshowed similar factor loadings and factor structure at subsequent waves of datacollection. The action-items were binary response items wherein teachers indicatedwhether they did or did not observe the principal engaging each action since the prior

Year 1 Year 2 Year 3

Cohort 1(treatment)

Feedback Feedback and coaching (Participants exited thestudy)

Cohort 2 (control) (Participants tooksurveys, but receivedno feedback)

Feedback Feedback and coachingTable I.Research design

690

JEA52,5

Dow

nloa

ded

by C

opyr

ight

Cle

aran

ce C

ente

r A

t 13:

28 2

1 A

ugus

t 201

4 (P

T)

round of data collection. Factor loadings, reported in Table II, reflect the strength ofassociation between positive item responses and each underlying latent factor.

We conducted a multilevel EFA with Geomin rotation on 17 action items usingMplus version 6.11. Decisions regarding the number of factors to retain in each casewere made based on a combination of empirical considerations and the need fordomains that would be substantively meaningful and informative. In order todetermine the best-tting model the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA;Steiger, 1990), and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) were used. Theuse of these two descriptive t indices is consistent with recent measurement research(see Millsap and Kwok, 2004).

Among the 17 items included on teacher surveys, multilevel EFA identified twolatent domains of leadership behavior. Based on the goodness of fit indices, this two-factor model showed a relatively good fit (w2(df¼ 206, n¼ 4,385)¼ 1,110.713*, po0.01,RMSEA¼ 0.050, and SRMR 0.089) according to both descriptive fit indices andtheoretical background. Factor scores were created by aggregating the product offactor loadings and response values across all 17 items for each teacher[2].

Although we rely on factor analysis to identify domains of leadership behaviorsposteriori (in contrast to drawing from theory to select domains a priori), conceptualsimilarities among items with high factor loadings within each factor lead us to attachdescriptive labels the “Principal Leadership Development” (PLD) and “TeacherInstructional Development” (TID) to factors 1 and 2, respectively.

Because its highest factor loadings are on actions a principal may take as they workto develop their own leadership practice, we identify our first factor as PLD. The PLDfactor includes seven items with factor loadings above 0.50. These items reflectleadership-developing actions such as sharing feedback results, planning action based

Action items PLD TID

1. Shared feedback from Peabody’s previous leadership surveys withteachers 1.005 �0.259

2. Discussed specific actions planned to take as result of feedback fromsurveys 0.926 �0.160

3. Discussed my goals for enhancing my leadership with teachers 0.841 0.0114. Asked teachers for their support in reaching leadership goals 0.849 �0.0075. Asked teachers to suggest actions that I could take to enhance my

leadership 0.895 0.0506. Asked teachers how well I am progressing toward leadership goals 0.810 0.1297. Discussed a teacher’s student achievement data in a team meeting setting 0.484 0.2038. Visited a teacher’s classroom to observe his or her teaching 0.062 0.7379. Paired a teacher with another teacher for mentoring and support �0.100 0.836

10. Reviewed a teacher’s IEPs and goal attainment for ELL and SPEDstudents 0.136 0.475

11. Discussed with a teacher his or her students’ achievement data 0.176 0.53212. Suggested possible actions to teachers based on student achievement data 0.492 0.27513. Discussed with a teacher the quality of his or her students’ work �0.005 0.82814. Discussed a teacher’s progress towards professional development goals 0.603 0.18715. Gave a teacher feedback on the quality of his or her teaching 0.201 0.67916. Reviewed teaching plans to assure plans aligned with curriculum

standards 0.245 0.57117. Discussed approaches a teacher can take to engage students’ families �0.003 0.855

Table II.Action items for

factor analysis

691

Changingprincipals’leadership

Dow

nloa

ded

by C

opyr

ight

Cle

aran

ce C

ente

r A

t 13:

28 2

1 A

ugus

t 201

4 (P

T)

on teacher feedback, and discussing their leadership and goals with teachers. Treatingas a scale the seven items with factor loadings above 0.50 for factor one, reliability(Cronbach’s a) for the PLD scale is 0.855 at the teacher level and 0.924 when aggregatedto the school level.

We label the second factor TID, reflecting high factor loading values on actions aprincipal may take to develop teachers’ instructional practices. The TID factor hashigh factor loadings on seven instruction-developing action items such as observingteachers’ instruction, giving meaningful feedback regarding teaching, discussingstudents work, and how teachers can engage with parents more effectively. Consideredas a scale, the seven items with factor loadings above 0.50 for factor two have areliability of 0.781 at the teacher-level and 0.850 when aggregated to the school-level. Ofthe 17 action-items, three items with factor loadings o0.50 indicated they did not tointegrate strongly onto either factor (Stevens, 1996). These three items (items 7, 10, and12) conceptually coincide with TID as they focus on the principals’ communicationwith teachers regarding student achievement data. Though we did not include them incalculation of scale reliabilities, their factor loadings do contribute to factor scores.

We generated factor scores for these two domains by weighting each binaryresponse by its corresponding factor loading, shown in Table II. Factors were thenaggregated to the school level to represent the average factor value for teacherresponses within each principal by wave. Values for Factor 1, PLD, ranged from 1.2 to6.9; values for Factor 2, TID, ranged from 1.5 to 4.4. Table III provides a summary of themean factor values over the three waves of data collection. Figure 2 shows thedistribution of the two factors for treatment and control groups, with a Lowess curve toprovide a sense of change over time. The clustering of data points around October,January, and May reflect the three waves of data collection (fall, winter, spring). A t-testshows no significant pretreatment difference between treatment and control groups oneither of the action item factors at the fall data collection.

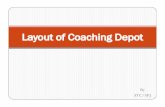

Coaching sessionsPrincipals’ freedom in scheduling coaching sessions resulted in notable variation in thenumber of coaching sessions each principal received[3] (see Figure 3). In the secondyear of the project, from which our data are drawn, treatment principals averaged eightcoaching sessions, though this number ranges from a minimum of five to a maximumof 14. To account for this variation in dose, we define treatment in our analysis as thenumber of coaching sessions each principal received rather than as a binary variablerepresenting assignment to the treatment group.

Analytical strategyIn this paper we have set out to identify the impact of a feedback and coachingintervention on principal action. We rely on multilevel factor analysis of teacher surveyresponses to both identify and measure latent domains of principal action: one wedescriptively label PLD, and the other TID. Barring any outside threats, a simpleregression correcting for multiple observations on each principal would be an

Factor Fall Winter Spring

Principal Leadership Development 3.98 (1.10) 4.41 (1.20) 4.26 (1.15)Teacher Instructional Development 3.41 (0.57) 3.64 (0.53) 3.56 (0.62)

Table III.Factor means(standard deviation)

692

JEA52,5

Dow

nloa

ded

by C

opyr

ight

Cle

aran

ce C

ente

r A

t 13:

28 2

1 A

ugus

t 201

4 (P

T)

0

2

4

6

8

01 O

ct 09

01 D

ec 0

9

01 F

eb 1

0

01 A

pr 1

0

01 Ju

n 10

Date

1

2

3

4

5

01 O

ct 09

01 D

ec 0

9

01 F

eb 1

0

01 A

pr 1

0

01 Ju

n 10

Date

Control Treatment

Control Treatment

Prin

cipa

l Lea

ders

hip

Dev

elop

men

t

Tea

cher

Inst

ruct

iona

l Dev

elop

men

t

Figure 2.Principal behaviors

over the fall, winter andspring data collections

Fre

quen

cyF

requ

ency

Fre

quen

cy

Spring

Winter

Fall

0

5

10

0

5

10

0

5

10

0 5 10 15

0 5 10 15

0

37

76 5

5 55

11

3

3

1 1

1

1 14

1 222

2

5 10 15cumulative coaching sessions

cumulative coaching sessions

cumulative coaching sessions

Figure 3.Frequency of

coaching sessions

693

Changingprincipals’leadership

Dow

nloa

ded

by C

opyr

ight

Cle

aran

ce C

ente

r A

t 13:

28 2

1 A

ugus

t 201

4 (P

T)

adequate analytic approach. However, two validity threats preclude using thisapproach. First, treatment consisted of coaching sessions that were arranged, in part,by principals. Therefore, while assignment to treatment was randomly determined, theactual treatment dose may be partially endogenous. When principals have influenceregarding the treatment dose, an endogenous relationship is introduced betweentreatment and outcomes. It is easy to imagine a scenario where ineffectiveprincipals may also be less likely to meet with coaches; such a scenario wouldinduce an upwards bias on the treatment effect. To mitigate this threat we use aninstrumental variables (IV) approach where assignment to treatment (which wasrandomly assigned two years prior, at the start of the project) is the excludedinstrument. The logic of this approach is that variation in assignment is uncorrelatedwith the number of coaching sessions undertaken by treatment principals (Angristand Pischke, 2008; Murnane and Willett, 2010). The two-stage least squares models areshown below:

Coachingit ¼ a0 þ a1 Txð Þitþ uit

Actionit ¼ b0 þ b1dCoaching

� �itþ eit

In these models Coaching represents the cumulative number of coaching sessions byprincipal i at time t; Tx is a dummy variable indicating assignment to treatment;Action represents either the PLD or the TID; Coaching (hat) is the predicted number ofcoaching sessions based on the first-stage estimate; and u and e are stochastic errorterms. Owing to anonymity agreements with the district, our data lack teacheridentifiers that would permit a multilevel modeling approach with teachers nestedwithin schools over time. An analysis with teacher data over time would havesubstantially greater analytical power than the model we employ. The silver lining toimplementing an analysis restricted to repeated observations on principals is that theresults will then represent a conservative estimate of treatment effects. In other words,any findings manifest here would be more easily detected with teacher level data.

The second threat to a simplistic approach pertains to differential attrition beforethe second year of the study. As mentioned previously, this analysis pertains to thesecond year of the intervention and uses measures that were not available duringthe first year. Differential attrition between years 1 and 2 would invalidate therandomization and negate the assumption of strong ignorability of treatmentassignment (Rosenbaum and Rubin, 1983). Again, it is not difficult to imagine ascenario wherein less effective principals are more likely to view coaching asthreatening and leave the program. Under this scenario a differential exit of principalsfrom the control group would induce an upward bias in the treatment effect.

In our study there was notable attrition between years one and two. However, thereis little evidence of differential attrition between the treatment and control principals.Of the 71 year-1 principals, 19 left the study between the first and second year. Nine ofthese 19 principals were from the treatment group. Of these 19 principals, 11 wereremoved from the study by the authors because they accepted a position in a school notparticipating in the study. Two principals retired. The remaining six principalsdeclined to participate in the second year of the study (four control, two treatment). Anattrition analysis where all 19 exiting principals were included is shown in Table IV.The coefficients represent odds-ratios from a logistic regression where one indicated aprincipal who left the sample.

694

JEA52,5

Dow

nloa

ded

by C

opyr

ight

Cle

aran

ce C

ente

r A

t 13:

28 2

1 A

ugus

t 201

4 (P

T)

The measures used in the attrition analysis include several measures of school climateand leadership, including teachers’ perceptions of academic press, teacher-teachertrust, teacher perceptions of LCL within the school, principal’s self-perceptions ofLCL, principal self-efficacy, and principal’s trust of teachers[4]. These are the baselinemeasures, taken in the first year of the study before any feedback or coaching wasprovided. Of these, the only measure that appears related to attrition is teachers’perceptions of leadership effectiveness (0.039*, p¼ 0.048), indicating that principalswho left the study have significantly lower measures of leadership effectiveness(mean teacher ratings of 3.53 vs 3.33). However, the interaction term between teachers’perception of leadership effectiveness and treatment is not significant, suggesting thatthere is not a discernable difference on this measure between those who left the studyfrom the treatment group as compared to those from the control group. This analysisprovides evidence that the initial randomization held through the second year.Nonetheless, to further insulate against this threat we have included a model in eachanalysis that also includes the above six baseline measures of school climate andleadership in addition to dummy variables for whether the data were collected duringthe fall, winter, or spring (models 3, 4, 7, and 8 in Tables II and III). These base-linevariables and wave dummy variables were included as excluded instruments in the IVmodel as well. In all models standard errors are cluster-adjusted for repeatedobservations on principals over time.

ResultsThe analytical results pertaining to the effect of treatment on actions related to PLD arepresented in Table V. Model 1 presents naı̈ve OLS results, model 2 presents thetwo-stage least squares IV approach, model 3 is a naı̈ve OLS model that includes schoolclimate, leadership measures, and dummy variables for the wave of data collection,and model 4 replicates model 3 with the addition of the IV.

In each of the four parameterizations we see that coaching has a significant positiveeffect on principals’ activities surrounding leadership development. The mostconstrained model reports an increase of 0.103 on the PLD factor for every additionalcoaching session. This corresponds to an effect size of 0.15[5]. Said differently,

Coefficient SE

Treatment 0.002 (0.019)Academic press 5.083 (13.986)Teacher-teacher trust 1.311 (2.449)Teachers’ perceptions of learning-centered leadership 0.039* (0.064)Principal’s perceptions of learning-centered leadership 0.559 (0.536)Principal self-efficacy 0.420 (0.550)Principal’s trust of teachers 4.651 (7.059)Treatment � academic press 0.079 (0.360)Treatment � teacher-teacher trust 0.648 (1.621)Treatment � teachers’ perceptions of leadership effectiveness 15.260 (28.954)Treatment � principal’s perceptions of leadership effectiveness 3.291 (4.026)Treatment � principal self-efficacy 7.209 (11.882)Treatment � principal’s trust of teachers 0.199 (0.377)Constant 67.097 (492.405)

Note: *Significant at the 0.05 levelTable IV.

Attrition analysis

695

Changingprincipals’leadership

Dow

nloa

ded

by C

opyr

ight

Cle

aran

ce C

ente

r A

t 13:

28 2

1 A

ugus

t 201

4 (P

T)

principals who attended more coaching sessions showed more growth in theirleadership development skills, even after adjusting for endogenity bias. It is plausiblethat principals who chose to schedule more coaching sessions may also be moremotivated and engaged in development activities broadly, thus artificially inflatingnaı̈ve estimates of treatment. If this were the case, IV estimation, which corrects forendogenity of dose, would yield attenuated treatment effects. Contrary to thishypothesis, the greater magnitude of the IV estimates of treatment as compared to theOLS treatment estimates (model 1omodel 2, model 3omodel 4) implies that the naı̈vemodels were under-estimating rather than overestimating the treatment effect. Thissuggests that principals may be strategically engaging in more coaching sessionsbased on their need for coaching.

Our second line of inquiry pertains to the impact of treatment on the ways in whichprincipals’ influence TID (factor 2). Table VI provides consistent evidence through all

Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 Model 4

Coaching and feedback 0.117** (0.038) 0.128** (0.052) 0.086* (0.033) 0.103* (0.040)Winter 0.297 (0.150) �0.007 (0.175)Spring 0.052 (0.156) 0.270* (0.124)Academic press (T) �1.121 (0.887) �1.144 (0.847)Teacher-teacher trust (T) �0.100 (0.465) �0.092 (0.440)Teacher LCL 1.212*** (0.310) 1.216*** (0.296)Principal LCL �0.720** (0.240) �0.723** (0.231)Self-efficacy (P) 0.255 (0.261) 0.271 (0.252)Principals’ trust ofteachers (P) 0.891* (0.361) 0.849* (0.353)Intercept 3.931*** (0.188) 3.901*** (0.214) 2.022 (2.224) 2.132 (2.127)IV No Yes No Yesn 156 156 156 156Variance explained 0.098 0.098 0.428 0.426

Notes: *,**,***Significant at the 0.05, 0.01, and 0.001 levels, respectively

Table V.The effect of treatment onPrincipal’s LeadershipDevelopment

Model 5 Model 6 Model 7 Model 8

Coaching and Feedback 0.001 (0.019) �0.013 (0.027) �0.014 (0.018) �0.010 (0.024)Winter 0.268*** (0.071) �0.263** (0.088)Spring 0.274*** (0.085) 0.000 (0.064)Academic press (T) �0.987 (0.481) �0.993* (0.465)Teacher-teacher trust (T) 0.079 (0.273) 0.081 (0.228)Teacher LCL 0.798*** (0.177) 0.799*** (0.170)Principal LCL 0.004 (0.145) 0.004 (0.140)Self-efficacy (P) 0.088 (0.161) 0.092 (0.157)Principals’ trust ofteachers (P) 0.048 (0.171) 0.037 (0.161)Intercept 3.223*** (0.018) 3.26*** (0.094) 2.774* (1.148) 3.063** (1.110)n 156 156 156 156IV No Yes No YesVariance explained 0.001 0.001 0.266 0.266

Notes: *,**,***Significant at the 0.05, 0.01 and 0.001 levels, respectively

Table VI.The effect of treatment onTeachers’ InstructionalDevelopment

696

JEA52,5

Dow

nloa

ded

by C

opyr

ight

Cle

aran

ce C

ente

r A

t 13:

28 2

1 A

ugus

t 201

4 (P

T)

four modeling approaches that treatment made no discernible impact on principalactions in this domain.

DiscussionThis study has been motivated by a need to provide school leaders with an iterative,sustainable, and efficient mechanism to integrate formative feedback with changes inleadership practices. Feedback reports serve as a discrepant event that in turnstimulates cognitive dissonance in the principal (Sapyta et al., 2005). Under thisframework the actions taken by the principal are initiated in order to resolve thedissonance. Coaching serves two functions in this process: to facilitate dissonance andto direct/motivate subsequent actions.

Through an EFA we have identified two factors that capture potential principalactions in response to teacher feedback: PLD and TID. The findings from an analysisof PLD, presented above, suggest that coaching and feedback together facilitateprincipals’ ability to engage with their faculty regarding their own leadershipdevelopment. Based on teachers’ feedback, coaches facilitate principals’ self-reflectionin order to initiate leadership change. This is promoted by helping principals clarifyand prioritize issues in their schools, interpret feedback that they could addressthrough their leadership practices, and provide skills which principals need to enhancetheir overall leadership. This finding is consistent with existing research, whichidentified strong effectiveness of combination of coaching and feedback in otherfields (Hobson, 2003; Smither et al., 2006). However, our second analysis suggeststhat the feedback and coaching approach does not noticeably impact principals’ effortstoward TID.

To better understand these findings, we consider three mechanisms that may havecontributed to these results: logistic effects, focus effects, and dissonance augmentingeffects. Logistic effects may be the result of information being conveyed moreefficiently to groups rather than to individual teachers. The specific actions thatcontribute most to the PLD factor include “Sharing feedback with teachers,”“Discussing specific actions planned to take as a result of feedback,” and “Discussinggoals of leadership with teachers.” These are actions that may lend themselves to largegroup settings where principals can address the entire faculty in one sitting. In suchcases, a single instance of a given action performed by the principal would be visibleand salient to a large number of teachers.

In contrast to items most associated with the PLD factor, actions that contributemost to the TID factor include “Discussed with a teacher the quality of student work”and “Gave a teacher feedback on the quality of his or her teaching.” These actionsalmost certainly require principals to engage with teachers one-on-one. Thus actionscontributing to high values on the TID factor require substantially more time and maypresent logistic challenges to school leaders.

From a measurement standpoint, the differing logistical constraints of these actionssuggests that, when aggregated to the school level, we are likely to observe a strongsignal from changes in the PLD factor than we are from TID factor.

These results may also speak to a focus effect: an effort on the part of coaches topush principals to be more strategic in their interactions with teachers. High qualityLCL is a time-consuming venture. Indeed, LCL is an area toward which principalswould like to devote more time (Hallinger and Murphy, 2013), and yet it tends to be onethe first domains to be curtailed under the press of external demands. Based on teacherfeedback coaches may encourage principals to target their interactions on a focussed

697

Changingprincipals’leadership

Dow

nloa

ded

by C

opyr

ight

Cle

aran

ce C

ente

r A

t 13:

28 2

1 A

ugus

t 201

4 (P

T)

group of teachers (e.g. new teachers or a grade-level team) rather than across the entireschool. If principals change from a diffuse manner of instructional support to focussedinstructional support, we may observe a null (or perhaps even negative) effect at theschool level. As a result of concessions made with the district, teacher responseswere anonymous and we cannot track teachers over time to determine if principals areusing such an approach to effectively target marginal teachers.

We can also interpret these results as evidence for the dissonance augmentingfunction of coaching. In keeping with prior work on feedback and dissonance(Bickman et al., 2006), qualitative work on this project suggests that some principalsare apt to dismiss the feedback. Coaches report that principals’ initial response to thefeedback is frequently defensive, where principals claim, “I know it’s just a fewteachers who are dissatisfied and I know who they are” or “I’m doing all I can – whatmore can they expect me to do?” We have also found that coaches are instrumental inhelping principals engage the dissonance process by overcoming their resistance tothe feedback. The positive results on the PLD factor provide evidence in favor thedissonance augmenting function of the coaching intervention. Principals are unlikelyto share feedback regarding their leadership if they feel that the feedback itself isinvalid. Thus, the act of sharing feedback becomes an active acknowledgement of thefeedback validity. Soliciting additional input from teachers on their leadership isanother mechanism to legitimate the validity of teacher perspectives. One of the goalsof coaching is to facilitate the dissonance process, which begins when resistantprincipals come to see the feedback as valid. This legitimating process allows cognitivedissonance to take place and only then can principals begin altering their behavior tobring their leadership views in line with those of their faculty. In this light, we cansee that the above results to be evidence for the dissonance augmenting aspect of thecoaching intervention.

Given the paucity of research in this area, and the exploratory nature of this study,we cannot test the specific mechanism and explanations but these results suggest theneed to design further studies that directly test each of these within the framework of ahypothesis testing study. Furthermore, we note possible methodological limitations ofthis study, such as attrition, bias introduced by unobservable factors, and imprecisemeasurements. Lastly, one year of coaching may not have been enough for principalsto change their leadership practice, or not enough time to alter teachers’ perceptionof principals’ instructional support. In order for coaches to bring desired andongoing change in principals, an adequate amount of time has to be devoted for a planof action. Principals in this study received an average of eight coaching sessions perwave; however, each session was less than two hours, which might not have beenenough time to sustain desirable leadership behavior with respect to teacher-focussedactions.

ConclusionAs there are very few random experiments studying interventions with schoolprincipals, this paper provides initial insights into the study of feedback and coaching.Providing meaningful feedback through principal assessment, and helping principalsto adequately interpret feedback through coaching, are viable tools to improveleadership practice. This study addresses the gap in the literature by both measuringthe quantitative impact of feedback and coaching and providing preliminary evidenceto support their combined efficacy. Where the coaching literature provides littleevidence regarding the dose of coaching, this analysis shows that eight to ten coaching

698

JEA52,5

Dow

nloa

ded

by C

opyr

ight

Cle

aran

ce C

ente

r A

t 13:

28 2

1 A

ugus

t 201

4 (P

T)

sessions (roughly once per month) may be adequate to induce behavioral change.We have also provided evidence that principals who voluntarily engage in morecoaching sessions are more likely to change their behaviors.

Leadership coaching for school leaders is a costly intervention, both in terms offinancial costs and opportunity costs, expressed as alternative ways a principal mayspend their time. This research has examined a coaching intervention that wasprovided to all principals and future research may wish to consider the impact ofsuch interventions targeted toward specific groups of principals. New principals,principals leading “turn-around” schools, and under-performing principals may showgreater returns to coaching.

To inform practitioners and policy makers, research in this area must go further anddirectly examine the impact of coaching and feedback on leadership, and equallyimportant explore the mechanisms of how feedback and coaching can influenceprincipal leadership. First, there is a need for more random experiments with largersamples, to replicate this study and ascertain the effects of feedback and coaching.In addition, research should vary the focus of coaching, where some coaches arehelping principals work with individual teacher – principal interactions, and othercoaching addresses distributed leadership actions to better understand themechanisms of how coaching might be most impactful. Qualitative studies canprobe as to the role of dissonance and gaps between principal self and teacher ratingsas a factor in motivating principals toward change (see Goldring et al., 2013). Similarly,more randomized control experiments can compare the effects of coaching to othertypes of professional development to ascertain the efficacy of each type of principalsupport. There is much needed work to be done in understanding the frequency andintensity of coaching and how this compares to the intensity of the typical groupprofessional development experience. Furthermore, prior theoretical explanationscan help identify important mediators for future studies on coaching, such as self-efficacy, which has been shown to influence leadership outcomes in other types ofprofessional development (Leithwood and Jantzi, 2008). Investigating how feedbackfrom teachers helps principal to improve their leadership and whether coachingpromotes the conversion of awareness into new leadership practices are importantavenues for future inquiry.

Notes

1. Analyses regarding attrition between years 1 and 2 are discussed in the Analysis section.

2. Supplemental analyses showed that factor loadings and factor structure were similar foreach wave of data collection.

3. How threat of validity was handled will be discussed in the Analysis section.

4. Six scales were used. Teachers’ perceptions of academic press consists of four items, and isconsistent with the work of Lee and Smith (1999); a¼ 0.84. Each of our three trust measureswas adapted from the work of the Tschannen-Moran and Hoy (1998). Teachers’ trust ofother teachers consists of five items; a¼ 0.90. Teachers’ trust of principals consists of fiveitems; a¼ 0.90. Principals trust of teachers consists of seven items; a¼ 0.76. Both measuresof LCL were derived from the VALED (Porter et al., 2010). Teachers’ perceptions of LCLconsists of 36 items with an a of 0.99; principals’ perceptions of LCL consists of 36 items withan a of 0.96. Principal self-efficacy was adapted from the work of Tschannen-Moran andGareis (2004), consists of six items and has a reliability of 0.85.

5. As calculated using the partial Z2 method.

699

Changingprincipals’leadership

Dow

nloa

ded

by C

opyr

ight

Cle

aran

ce C

ente

r A

t 13:

28 2

1 A

ugus

t 201

4 (P

T)

References

Alicke, M.D. and Sedikides, C. (2009), “Self-enhancement and self-protection: what they are andwhat they do”, European Review of Social Psychology, Vol. 20 No. 1, pp. 1-48.

American Management Association (2008), Coaching: A Global Study of Successful Practices,American Management Association, New York City, NY.

Angrist, J.D. and Pischke, J.S. (2008), Mostly Harmless Econometrics: An Empiricist’s Companion,Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

Atwater, L.E., Ostroff, C., Yammarino, F.J. and Fleenor, J.W. (1998), “Self-other agreement: does itreally matter?”, Personnel Psychology, Vol. 51 No. 3, pp. 577-598.

Bacon, T.R. and Spear, K.I. (2003), Adaptive Coaching: The Art and Practice of a Client-centeredApproach to Performance Improvement, Davis-Black, Palo Alto, CA.

Bickman, L., Riemer, M., Breda, C. and Kelley, S.D. (2006), “CFIT: a system to providea continuous quality improvement infrastructure through organizational responsiveness,measurement, training, and feedback”, Report on Emotional and Behavioral Disorders inYouth, Vol. 6 No. 4, pp. 86-94.

Bloom, G.S. (2004), “Emotionally intelligent principals”, School Administrator, Vol. 61 No. 6,pp. 14-17.

Bowles, S., Cunningham, C.J.L., Rosa, G.M.D.L. and Picano, J. (2007), “Coaching leaders in middleand executive management: goals, performance, buy-in”, Leadership and OrganizationDevelopment Journal, Vol. 28 No. 5, pp. 388-408.

Brett, J.F.J. and Atwater, L.E.L. (2001), “360 degree feedback: accuracy, reactions, and perceptionsof usefulness”, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 86 No. 5, pp. 930-942.

Bryk, A.S., Sebring, P.B., Allensworth, E., Easton, J.Q. and Luppescu, S. (2010), OrganizingSchools for Improvement: Lessons from Chicago, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL.

Cannon, M.D. and Witherspoon, R. (2005), “Actionable feedback: unlocking the power of learningand performance improvement”, The Academy of Management Executive, Vol. 19 No. 2,pp. 120-134.

Connelly, G. (2010), “A conversation with secretary of education Arne Duncan”, Principal, Vol. 90No. 2, pp. 34-38.

Darling-Hammond, L. (2010), The Flat World and Education: How America’s Commitment toEquity will Determine Our Future, Teachers College Press, New York, NY.

Darling-Hammond, L., LaPointe, M., Meyerson, D. and Orr, M.T. (2007), Preparing School Leadersfor a Changing World: Lessons from Exemplary Leadership Development Programs,Stanford Educational Leadership Institute, Stanford University, Stanford, CA.

Darling-Hammond, L., Meyerson, D., LaPointe, M. and Orr, T. (2009), Preparing Principals for aChanging World: Lessons from Effective School Leadership Programs, Jossey-Bass,San Francisco, CA.

Feldman, D.C. and Lankau, M.J. (2005), “Executive coaching: a review and agenda for futureresearch”, Journal of Management, Vol. 31 No. 6, pp. 829-848.

Festinger, L. (1957), A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance, Row Peterson, Evanston, IL.

Goldring, E., Mavrogordato, M.C. and Haynes, K.T. (2013), “Multi-source principal evaluationdata: how principals approach, interpret and use teacher feedback regarding theirleadership effectiveness”, paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the AmericanEducation Research Association, San Francisco, CA, April.

Goldring, E., Huff, J., May, H. and Camburn, E. (2008), “School context and individualcharacteristics: what influences principal practice?”, Journal of EducationalAdministration, Vol. 46 No. 3, pp. 332-352.

700

JEA52,5

Dow

nloa

ded

by C

opyr

ight

Cle

aran

ce C

ente

r A

t 13:

28 2

1 A

ugus

t 201

4 (P

T)

Goldring, E., Porter, A., Murphy, J., Elliot, S. and Cravens, X. (2009a), “Assessing learning-centered leadership: connections to research, standards and practice”, Leadership andPolicy in Schools, Vol. 8 No. 1, pp. 1-36.

Goldring, E., Cravens, X.C., Murphy, J., Porter, A.C., Elliott, S.N. and Carson, B. (2009b), “Theevaluation of principals: what and how do states and urban districts assess leadership?”,The Elementary School Journal, Vol. 110 No. 1, pp. 19-39.

Goldring, E., Bickman, L., Cannon, M., Mavrogordato, M., Breda, C., Goff, P., Huff, J. and Preston, C.(2010), “The next generation of principal professional development: feedback and coachingas a tool for leadership development”, paper presented at the Conference of the Challengesand Prospects of School Improvement in the New Era, Taipei.

Grant, A.M. (2003), “The impact of life coaching on goal attainment, metacognition andmental health”, Social Behavior & Personality: An International Journal, Vol. 31 No. 3,pp. 253-264.

Gray, D.E. (2006), “Executive coaching: towards a dynamic alliance of psychotherapy andtransformative learning processes”, Management Learning, Vol. 37 No. 4, pp. 475-497.

Hallinger, P. (2010), “A Review of three decades of doctoral studies using the principalinstructional management rating scale: a lens on methodological progress in educationalleadership”, Educational Administration Quarterly, Vol. 47 No. 2, pp. 271-306.

Hallinger, P. and Murphy, J.F. (2013), “Running on empty? Finding the time and capacity to leadlearning”, NASSP Bulletin, Vol. 97 No. 1, pp. 5-21.

Hattie, J. (1999), “Influences on student learning”, inaugural professorial address, University ofAuckland, Auckland.

Hattie, J. and Timperley, H. (2007), “The power of feedback”, Review of Educational Research,Vol. 77 No. 1, pp. 81-112.

Hesketh, E.A., Anderson, F., Bagnall, G.M., Driver, C.P., Johnston, D.A., Marshall, D., Needham, G.,Orr, G. and Walker, K. (2005), “Using a 360 degree diagnostic screening tool to providean evidence trail of junior doctor performance throughout their first postgraduate year”,Medical Teacher, Vol. 27 No. 3, pp. 219-233.

Hobson, A. (2003), Mentoring and Coaching for New Leaders, National College for SchoolLeadership, Nottingham.

Huber, S.G. (2004), “School leadership and leadership development: adjusting leadership theoriesand development programs to values and the core purpose of school”, Journal ofEducational Administration, Vol. 42 No. 6, pp. 669-684.

Huff, J., Preston, C. and Goldring, E. (2013), “Implementation of a coaching program for schoolprincipals: evaluating coaches’ strategies and the results”, Educational Management,Administration, and Leadership, Vol. 41 No. 4, pp. 504-526.

Kluger, A.N. and DeNisi, A. (1996), “The effects of feedback interventions on performance:a historical review, a meta-analysis, and a preliminary feedback intervention theory”,Psychological Bulletin, Vol. 119 No. 2, pp. 254-284.

Kombarakaran, F.A., Yang, J.A., Baker, M.N. and Fernandes, P.B. (2008), “Executive coaching: itworks!”, Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, Vol. 60 No. 1, pp. 78-90.

Koonce, R. (1994), “One on one: executive coaching for underperforming top-level managers”,Training and Development, Vol. 48 No. 2, pp. 34-40.

Lee, V.E. and Smith, J.B. (1999), “Social support and achievement for young adolescents inChicago: the role of school academic press”, American Educational Research Journal,Vol. 36 No. 4, pp. 907-945.

Leithwood, K. (1994), “Leadership for school restructuring”, Educational AdministrationQuarterly, Vol. 30 No. 4, pp. 498-518.

701

Changingprincipals’leadership

Dow

nloa

ded

by C

opyr

ight

Cle

aran

ce C

ente

r A

t 13:

28 2

1 A

ugus

t 201

4 (P

T)

Leithwood, K. and Jantzi, D. (2008), “Linking leadership to student learning: the contributions ofleader efficacy”, Educational Administration Quarterly, Vol. 44 No. 4, pp. 496-528.

Leithwood, K., Riedlinger, B., Bauer, S. and Jantzi, D. (2003), “Leadership program effects onstudent learning: the case of the greater New Orleans school leadership center”, Journal ofSchool Leadership, Vol. 13 No. 6, pp. 707-738.

London, M. (2001), Leadership Development: Paths to Self-insight and Professional Growth,Erlbaum, Mahwah, NJ.

Luthans, F. and Peterson, S.J. (2004), “360-degree feedback with systematic coaching: empiricalanalysis suggests a winning combination”, Human Resource Management, Vol. 42 No. 3,pp. 243-256.

McCauley, C.D. and Moxley, R.S. (1996), “Developmental 360: how feedback can make managersmore effective”, Career Development International, Vol. 1 No. 3, pp. 15-19.

Marks, H.M. and Printy, S.M. (2003), “Principal leadership and school performance: anintegration of transformational and instructional leadership”, Educational AdministrationQuarterly, Vol. 39 No. 3, pp. 370-397.

Marzano, R.J., Waters, T. and McNulty, B.A. (2005), School Leadership that Works: From Researchto Results, Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, Alexandria, VA.

Mavrogordato, M. and Cannon, M. (2009), “Coaching principals: a model for leadershipdevelopment”, paper presented at the University Counsel For Educational AdministrationConvention, Anaheim, CA, November.

Millsap, R.E. and Kwok, O.M. (2004), “Evaluating the impact of partial factorial invariance onselection in two populations”, Psychological Methods, Vol. 9 No. 1, pp. 93-115.

Moore, B. (2009), “Improving the evaluation and feedback process for principals”, Principals,Vol. 88 No. 3, pp. 38-41.

Murnane, R.J. and Willett, J.B. (2010), Methods Matter: Improving Causal Inference in Educationaland Social Science Research, Oxford University Press, New York, NY.

Murphy, J.F., Goldring, E.B., Cravens, X.C., Elliott, S.N. and Porter, A.C. (2011), “The Vanderbiltassessment of leadership in education: measuring learning-centered leadership”, Journal ofEast China Normal University, Vol. 29 No. 1, pp. 1-10.

Neufeld, B. and Roper, D. (2003), Coaching: A Strategy for Developing Instructional Capacity:Promises and Practicalities, Aspen Institute Program on Education, Washington, DC.

Patten, T.D. (2006), “Principals’ perceptions of their professional development implementationfor sustained change”, unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Florida,Gainesville, FL.

Peterson, D.B. and Hicks, M.D. (1996), Leader as Coach: Strategies for Coaching and DevelopingOthers, Personnel Decisions International, Minneapolis, MN.

Porter, A.C., Polikoff, M.S., Goldring, E., Murphy, J., Elliott, S.N. and May, H. (2010), “Developing apsychometrically sound assessment of school leadership: the VAL-ED as a case study”,Educational Administration Quarterly, Vol. 46 No. 2, pp. 135-173.

Portin, B.S., Knapp, M.S., Dareff, S., Feldman, S., Russell, F.A., Samuelson, C. and Yeh, T.L. (2009),Leadership for Learning Improvement in Urban Schools, Center for the Study of Teaching& Policy, University of Washington, Seattle, WA.

Reeves, D.B. (2009), Leading Change in Your School: How to Conquer Myths, Build Commitment,and get Results, Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, Alexandria, VA.

Reiss, K. (2006), Leadership Coaching for Educators: Bringing Out the Best in SchoolAdministrators, Corwin Press, Thousand Oaks, CA.

Robinson, V.M. (2007), School Leadership and Student Outcomes: Identifying What Works andWhy, Australian Council for Educational Leaders, Melbourne, Australia.

702

JEA52,5

Dow

nloa

ded

by C

opyr

ight

Cle

aran

ce C

ente

r A

t 13:

28 2

1 A

ugus

t 201

4 (P

T)

Robinson, V.M., Lloyd, C.A. and Rowe, K.J. (2008), “The impact of leadership on studentoutcomes: an analysis of the differential effects of leadership types”, EducationalAdministration Quarterly, Vol. 44 No. 5, pp. 635-674.

Rosenbaum, P.R. and Rubin, D.B. (1983), “The central role of the propensity score inobservational studies for causal effects”, Biometrika, Vol. 70 No. 1, pp. 41-55.

Sapyta, J., Riemer, M. and Bickman, L. (2005), “Feedback to clinicians: theory, research andpractice”, Journal of Clinical Psychology, Vol. 61 No. 2, pp. 145-153.

Schein, E.H. (2010), Organizational Culture and Leadership, 4th ed., Jossey-Bass,San Francisco, CA.

Showers, B. and Joyce, B. (1996), “The evolution of peer coaching”, Educational Leadership,Vol. 53 No. 6, pp. 12-16.

Smither, J.W., London, M. and Reilly, R.R. (2005), “Does performance improve followingmultisource feedback? A theoretical model, meta-analysis, and review of empiricalfindings”, Personnel Psychology, Vol. 58 No. 1, pp. 33-66.

Smither, J.W., London, M., Flautt, R., Vargas, Y. and Kucine, I. (2006), “Can working with anexecutive coach improve multisource feedback ratings over time? A quasi-experimentalfield study”, Personnel Psychology, Vol. 56 No. 1, pp. 23-44.

Spillane, J.P., Halverson, R. and Diamond, J.B. (2001), “Investigating school leadership practice: adistributed perspective”, Educational Researcher, Vol. 30 No. 3, pp. 23-28.

St. Martin, K. (2010), “The knowing-doing gap: the influence of teacher feedback in changingprincipal behavior – a mixed methods study”, unpublished doctoral dissertation, WesternMichigan University, Kalamazoo, MI.

Steiger, J.H. (1990), “Structural model evaluation and modification: an interval estimationapproach”, Multivariate Behavioral Research, Vol. 25 No. 2, pp. 173-180.

Stevens, J. (1996), Applied Multivariate Statistics for the Social Sciences, 3rd ed., LawrenceErlbaum, Mahwah, NJ.

Thach, E.C. (2002), “The impact of executive coaching and 360 feedback on leadershipeffectiveness”, Leadership and Organization Development Journal, Vol. 23 No. 4,pp. 205-214.

Thach, L. and Heinselman, T. (2000), “Continuous improvement in place of training”, inGoldsmith, M., Lyons, L. and Freas, A. (Eds), Coaching for Leadership: How the World’sGreatest Coaches Help Leaders Learn, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA, pp. 219-230.

Thomas, D.W., Holdaway, E.A. and Ward, K.L. (2000), “Policies and practices involved in theevaluation of school principals”, Journal of Personnel Evaluation in Education, Vol. 14No. 3, pp. 215-240.

Tornow, W.W. and London, M. (1998), Maximizing the Value of 360-Degree Feedback: A Processfor Successful Individual and Organizational Development, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA.

Tschannen-Moran, M. and Gareis, C.R. (2004), “Principals’ sense of efficacy: assessing apromising construct”, Journal of Educational Administration, Vol. 42 No. 5, pp. 573-585.

Tschannen-Moran, M. and Hoy, W. (1998), “Trust in schools: a conceptual and empiricalanalysis”, Journal of Educational Administration, Vol. 36 No. 4, pp. 334-352.

Walker, A.G. and Smither, J.W. (1999), “A five-year study of upward feedback: what managers dowith their results matters”, Personnel Psychology, Vol. 52 No. 2, pp. 393-423.

Waters, T., Marzano, R.J. and McNulty, B. (2003), Balanced Leadership: What 30 years of ResearchTells us about the Effect of Leadership on Student Achievement, Mid-continentResearch for Education and Learning, Aurora, CO.