Captured (and disturbing for some): A last look at the abortionist

Transcript of Captured (and disturbing for some): A last look at the abortionist

(This is a sample cover image for this issue. The actual cover is not yet available at this time.)

This article appeared in a journal published by Elsevier. The attachedcopy is furnished to the author for internal non-commercial researchand education use, including for instruction at the authors institution

and sharing with colleagues.

Other uses, including reproduction and distribution, or selling orlicensing copies, or posting to personal, institutional or third party

websites are prohibited.

In most cases authors are permitted to post their version of thearticle (e.g. in Word or Tex form) to their personal website orinstitutional repository. Authors requiring further information

regarding Elsevier’s archiving and manuscript policies areencouraged to visit:

http://www.elsevier.com/copyright

Author's personal copy

Captured (and disturbing for some): A last look at the abortionist☆

Kate GleesonPolitics, Macquarie University, NSW, Australia

a r t i c l e i n f o s y n o p s i s

Available online xxxx This article reflects on a recent exhibition hosted at the Sydney Justice and Police Museum. TheFemme Fatale exhibition aimed to highlight the way “society has interpreted and contained thecriminality of women”, through the depiction of women convicted of various crimes, includingabortion related offences. This article discusses the abortion display of the exhibition to explorethe longstanding political anxiety provoked by abortion imagery. It focuses on the ongoingpower of the image of abortion, and the female abortionist in particular, and questions thepotential for the deployment of such imagery in a feminist context. The article argues that byfocusing on the female abortionist as she was targeted by the police, and not on catastrophicoutcomes for her patients, the Femme Fatale exhibition highlights the historical, mundanerealities of women's reproductive lives, and the centrality of women's networks to this world. Itchallenges hegemonic medical authority that has claimed women's reproductive praxis as itsown, and importantly, alludes to the power historically deployed by midwives before thismedical colonisation.

© 2011 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

There are few subjects on which bourgeois society displaysgreater hypocrisy; abortion is considered a revolting crime towhich it is indecent even to refer. For an author to describe thejoy and suffering of a woman in childbirth is quite all right;but if he depicts a case of abortion, he is accused of wallowingin filth and presenting humanity in a sordid light.Simone de Beauvoir (1949 [1997], p. 502), The Second Sex.

The Femme Fatale exhibition

Recently the Historic Houses Trust hosted the Femme Fataleexhibition at the Sydney Justice and Police Museum from 7March 2009 to 18 April 2010. Informed by the observation that

“women's crimes simultaneously appal and entice us, excitingan interest not generated by male felons” the feministexhibition aimed to highlight the way “society has interpretedand contained the criminality of women” (Historic HousesTrust [HHT], 2008, p. 1). It did this by juxtaposing popularcultural images of the “seductive femmes fatale of pulp fictionand film noir” with images of the “reality of criminal women'slives” (HHT, 2008, p. 1). The curator, Nerida Campbell, collated59 objects from the museum's collection relating to “women'sexperience of the justice system” in themuseum's 79 m2 space,including cut-throat razors used by gangs of the 1920s, astraitjacket hand sewn by inmates of Darlinghurst gaol in the1840s, and letters from women prisoners of the 19th century(personal communication, 18 May 2011). On entering theexhibition the visitor was first confronted with the notoriouswitch burner's bible, the 1486 Malleus Maleficarum, whichserved as a manual for the “trial” and persecution of suspectedwitches throughout Europe. One of the most influential of allthe early books, the “hammer against the witches”, isappreciated today as a fantastic work of misogyny due to itsbase, undisguised attack of women, and its fundamentalpathologising thesis, that “the lust of women leads them intoall sins; for the root of all woman's vice is avarice” (HHT, 2008,p. 3). This early modern Catholic “linkage of [women's] lust,

Women's Studies International Forum 34 (2011) 520–529

☆ Dr Kate Gleeson is an Australian Research Council Fellow in thediscipline of Politics at Macquarie University. Research for this article wasundertaken with the support of an Australian Postdoctoral Fellowship(DP0986934 2009–2013). Many thanks to Marg Kirkby for encouraging meto attend the Femme Fatale exhibition, to the anonymous reviewers of thisjournal for helpful advice, and to Nerida Campbell and Jim Staples for theirtime and wonderful interviews. Thanks also to the Historic Houses Trust forprovision of the photographs that illustrate this article. An earlier version ofthis paper was presented to the Sydney Feminist History Group August 262010.

0277-5395/$ – see front matter © 2011 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.doi:10.1016/j.wsif.2011.07.007

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Women's Studies International Forum

j ou rna l homepage: www.e lsev ie r.com/ locate /ws i f

Author's personal copy

greed and vice” and its influence on “later western thinkingabout female criminality” formed a core focus of the FemmeFatale exhibition (HHT, 2008, p. 3).

One of the most compelling components of the FemmeFatale exhibition involved the display of a series of intakephotographs of female inmates of the State Reformatory atSydney's Long Bay from 1915 to 1930. The portraits stood incold contrast to the terrific heat and passion driving the ofthysterical diatribe against witches. The blank stares of thesepia-stained Edwardian criminals projected a ghostly, ratherthan occult, ennui: each woman convicted variously of violent,property, or vice crimes, “captured” not only transiently by thestate, but alsopermanently by the cellular technology recordingher undignified entrance into formal “reformation”. Of all thewomen prisoners represented in the exhibition, one class wasprovided its own separate space. The images of those convictedof a crime that has indeed been policed as though it werepeculiarly and perniciously female, were secluded in a privatewomen's sphere. Literally in the back room of the exhibitionstood a display reserved for images of State Reformatoryinmates convicted of abortion related offences, along withimages of the paraphernalia and evidence used to indictabortionists in New South Wales before the state's abortionlandscape changed in 1971, and their legal persecution was allbut ceased.

Included in the exhibition because abortion is a crime “thatalways involves a woman” (Campbell, personal communica-tion, 11 August 2010), this separate display was introduced(and divided) with the normative warning that “this roomcontains objects and images relating to abortion that maydisturb some visitors”. The images were not graphic, orsensational, and Campbell was “careful with everything fromthe colours that were used in that room, even the way that wewere printing and using photographic material” (personalcommunication, 11 August 2010). The decision to separate theabortion display from the rest of the exhibitionwas “a practical”one: made by Campbell based on the reasoning that schoolgroups are frequent visitors to themuseum, and teachersmightnot feel comfortable introducing their students to abortion.Anecdotal feedback suggests that older women, who couldrecall the time before 1971, were most appreciative of thedisplay; and it was men, more than women, who “tended towalk away” and not view it (Campbell, personal communica-tion, 11 August 2010).

The Justice and Police Museum regularly hosts exhibitionsaddressing crime and the underworld, including murder andmayhem: themes that perhaps should disturb us, and whichvisitors ought to anticipate at such a museum. But it was illicitabortion imagery only that was demarcated as especially,potentially disturbing to visitors. What lies at the heart of thisdisturbance? Is it a simple bourgeois hypocrisy, of the kindidentified by de Beauvoir? What does it mean for a feministexhibition to propagate the idea that abortion is especiallydisturbing? Rather than embodying hypocrisy, I argue that theexhibition's treatment of abortion provokes a radically feministimagining of abortion, focused not on the woman patient asvictim, but on the midwife as a longstanding threat to theinstitutions of the church, the state, the law, and medicine.Feminist authors agree that women need to be “kept in thepicture” of abortion discourse, and many have relied oncatastrophic abortion imagery and truths about women as

victims of illicit regimes, in attempts to focus abortion debatesonwomen. In contrast, the FemmeFatale exhibitionputswomenas abortionists in the picture.

This article examines the longstanding political anxietyprovoked by abortion imagery. It focuses on the ongoingpower of the image of abortion, and the female abortionist inparticular, and questions the potential for the deployment ofsuch imagery in a feminist context. As with so much abortiondiscourse, these insights arising within the Femme Fataleexhibition remained largely unarticulated within themuseum's display. In this article I want to tease them out.By focusing on the female abortionist as she was targeted bythe police, and not on catastrophic outcomes for her patients,the exhibition highlights the historical, mundane realities ofwomen's reproductive lives, and the centrality of women'snetworks to this world. In its evocation of the MalleusMaleficarum, and in its seclusion of “disturbing” women'sbusiness in a private realm from whence it historically came,the exhibition helps to illuminate longstanding cultural andpolitical anxieties about abortion, by capturing the specialpathological aversion to it and women's reproductive agencymore generally. It challenges hegemonic medical authoritythat has claimed women's reproductive praxis as its own, andalludes to the power historically deployed by midwivesbefore this medical colonisation. This article is structured asfollows. First I introduce theMalleus Maleficarum and explainthe early Catholic fear of midwives that was exploited by thenascent male medical profession of the middle ages. Next Ibriefly explain the history of abortion in Australia before lawreform, and the 1971 NSW trial that brought an end to the layabortion trade in that state. I then outline feminist theories toexplain the ongoing fear of abortion and women's sexual andreproductive knowledge, and I discuss the associated powerof abortion imagery for both feminists and anti abortionists. Iconclude by noting the radical nature of the types of imagerypresented in the Femme Fatale exhibition focused on theabortionist as practitioner.

The Malleus Maleficarum

The Malleus Maleficarum has been described as the “singlemost horrendous expression” of misogyny in early modernEurope (Kelly in Clarke, 1997, p. 112). Included in itspublication was the 1484 papal bull of Pope Innocent VIIIwhich gave papal approval for the Inquisition to prosecutewitchcraft. It identified the key components ofwitchcraft as the“renunciation of the Catholic faith; the devotion of body andsoul to the service of evil; offering upunbaptised children to thedevil; and engaging in orgies that included intercoursewith theDevil” (Russell &Alexander, 2007, p. 115). Although theMalleusMaleficarum decreed that all witches, both men and women,“must be accused, arrested and convicted”, it reasoned thatmost witches were female, because “all witchcraft comes fromcarnal lust, which is in the woman insatiable”. Because womenwere naturally less able to “grasp spiritual matters”, and were“credulous and impressionable” and “intellectually like chil-dren” (Clarke, 1997,p. 122), theywere also seducedmoreeasilythan men by the pacts of the devil.

Feminist scholars have noted how the association of womenwithwitchcraft at this time reflected long standingphilosophicaland religious associations of women with nature and polluted

521K. Gleeson / Women's Studies International Forum 34 (2011) 520–529

Author's personal copy

natural forces which ought to be feared and subdued, inopposition to men who are defined by their “natural strengthof reason” and their sexed associationwith Christ (who chose tobe bornmale) (Clarke, 1997, p. 129). This tradition incorporatedclassical Aristotelian precepts about women as inherently“deformed”, and Platonic doubts about their humanity, both ofwhich informed Aquinas's views of women as possessing alower form of soul than men (Clarke, 1997, pp. 118–121). TheMalleus Maleficarum thus consolidated philosophies built onbiblical mythology of women as more carnal than men, as is“clear from her many carnal abominations”, and identified thiscarnality as probably having stemmed from Eve's formation“from a bent rib, that is, the rib of the breast, which is bent as itwere in a contrary direction to a man” (Institoris & Sprenger,2006, p. 44).

Beyond the philosophical and spiritual realms, theassociation of women and witchcraft also reflected women'sintimate associations with the mysterious rhythms of life anddeath. As Ehrenreich and English (1973, p. 3) have docu-mented “witches” were often, in fact, “healers” who posed athreat to nascent European medical science. In their relation-ships to pregnancy and childbirth in particular, women ofearly modern societies participated in mortal experiences ofphysicality beyond the possible knowings and practical reachof the patriarchal church, and it was this intimate femaleexperience that provoked the greatest rancour amongst witchhunters. Despite identifying all women as aberrations of men(therefore Christ), the Malleus Maleficarum warned thatmidwives, “surpass[ed] all others in wickedness”, for “witcheswho are midwives in various ways kill the child conceived inthe womb, and procure an abortion; or if they do not do this,offer new-born children to devils”. It continued,

we must add that in all these matters witch midwivescause yet greater injuries, as penitent witches have oftentold us and to others, saying: No one does more harm tothe Catholic faith than do midwives, for when they do notkill children, then, as if for some other purpose, they takethem out of the room, and raising them up in the air, offerthem to devils (Institoris & Sprenger, 2006, p. 66).

The sacrifice of an unbaptised soul was recognised as onehallmark of witchcraft. Abortion, spontaneous or induced,and the death (or even deformity) of a baby in birth wastypically “laid at [the] door” of the attending midwife, whowas often charged with negligence, or with sorcery, if nophysical explanation for the death could be found (Russell &Alexander, 2007, p. 115). Along with concerns for mortalsouls, the hatred of midwives was also fuelled by populationand replenishment fears. The Malleus Maleficarum implicatedmidwives in preventing births by way of magically causingimpotence in men and, by “preventing the flow of vitalessences to the members, in which resides the motive force,closing up the seminal ducts so that it does not reach thegenerative vessels, or so that it cannot be ejaculated, or isfruitlessly spilled”. The text also warned of one “mostnotorious witch who could at all times and by a mere touchbewitch women and cause an abortion” (Institoris &Sprenger, 2006, p. 118). The misogyny of the hammer of thewitches must thus be understood not only in the context of a

terror of the female control of reproduction, in both thespiritual and earthly realms, but also as part of a campaign bywhich “new male medical profession, under the protectionand patronage of the ruling class” aimed to eliminate womenhealers and midwives from the thirteenth century onwards(Ehrenreich & English, 1973, pp. 6 and 15).

Abortion in Australia before law reform

A fear of midwives and abortion survived in the modernera, and has been implicated in the 19th century criminalisa-tion of abortion beyond the ecclesiastical courts. In the UnitedKingdom, and therefore Australia, all legal developmentsconcerning abortion moved to consolidate medical control ofthe procedure. In 1803 the British parliament made it a crimeto unlawfully procure of a miscarriage, but therapeuticabortion performed by doctors was generally understood tobe lawful. Influenced by the nascent doctors' lobby and itscampaigns against “irregulars” (midwives and homoeo-paths), abortion law evolved to become less discretionary tomake it easier to secure convictions, and abortion came to begoverned by the Offences Against the Person Act 1861(Gleeson, 2011, p. 217), which the Australian coloniesreplicated. Legal prohibitions failed to stem abortion, and bythe time of the Royal Commission into the Decline of the BirthRate in 1904, abortion was implicated in Australia's dismalwhite birth rate, and formed in Judith Allen's terms, “theguilty secret at the heart of the Commission”, with policetestimonies indicating that it was “very difficult to get a juryto convict, even in the case of clear evidence” (Allen, 1990,p. 68). Despite women's testimonies of economic hardship, inpassages reminiscent of the Malleus Maleficarum's fears forreplenishment, the Commissioners blamed the birth declinelargely on the “selfishness and pleasure seeking” of women(Gregory, 2007, p. 63).

Until the inter-war period, for those women who did notself-abort (and it is apparent that very many did), midwivesand other traditional female abortionists, with both informaland formal medical training (Finch & Stratton, 1988, p. 57),performed the bulk of the abortion services. Hera Cook hasshown that in this period Australian working class womenhad access to abortion networks that resulted in “betterquality” abortion services, than both their rural Australian,and urban English, counterparts (Cook, 2000, p. 133). Thiscontributed to a “moral panic” about birth control amongstthe Australian working class (Finch, 1993, p. 107), whosewomen (and men) tended to view pregnancy as a “woman'scondition” concerned with “regularity”, that men took littleresponsibility for (Allen in Finch, 1993, p. 111). Accordingly,abortion was understood as women's business. Amongst theruling class, male doctors “positioned themselves as experts,or the natural guardians of the foetus and the child” (Finch,1993, p. 112). From the 1880s, gynaecology emerged as aspecialty and more doctors began to practise abortion andconsolidated their “competitive move” against midwives andtraditional abortionists (Finch, 1993, p. 120) by servingwomen of the middle and upper classes. Working classwomen continued to rely on traditional female abortionistsincludingmidwives, who operatedwith “skill and experience,with a low rate of complications” andwho, in their capacity towork “independently of medical men”, posed the greatest

522 K. Gleeson / Women's Studies International Forum 34 (2011) 520–529

Author's personal copy

competition to medical practitioners (Gregory, 2004, pp. 76and 88).

In 1938, the English case of Bourne clarified the criminaldefence of abortions performed by doctors to save a woman'slife, broadly interpreted to include psychological factors (Kingv Bourne [1939]). The judgement confirmed the authority ofthe medical establishment over abortion and came to beunderstood as persuasive authority in Australian jurisdic-tions. Following this, and with the onset of penicillin, moremale doctors moved into the potentially lucrative sector, andby the 1950s some (on the east coast) had engaged in corruptrelationships with police who exploited the lack of legalclarity on this issue (Gleeson, 2009, p. 73). At this time,members of the NSW police force held “all kinds of varyingattitudes” to abortion. “Everybody agrees that it washappening and there were some dreadful things that didhappen. There were police who were very staunchly againstabortion and heavily pursued it. And there are others whowould only take it up if something happened, or theirattention was drawn to it — women who became ill or haddied” (Campbell, personal correspondence, 11 August 2010).In Australia, as elsewhere, when the law was enforced,women abortionists were targeted. Most defendants wereacquitted, unless there was serious injury or death of thewoman. Doctors and chemists apparently were alwaysacquitted. Doctors were so untouchable they escaped man-slaughter convictions despite, in one case, the woman havingbeen found dead in the doctor's flat. From 1959 to 1969 inNSW, not one of the 22 persons convicted of abortion relatedoffences was a medical practitioner (Gleeson, 2009, p. 73).

The medicalisation of abortion: the Heatherbrae trial of1971

In the 20th century the sum experiences of pregnancyand birth were shifted towards doctors and hospitals, awayfrom the home and local midwives, as part of a moderncampaign of “staking of professional terrain, particularly forthe developing medical specialisation of obstetrics andgynaecology where midwife and nurse abortionists werethe doctors most serious professional competitors” (Baird,1996, p. 9). This shift also formed part of a process of“rearticulating” pregnancy as the “nurturing of a humanbeing”: an “intervention into working class social practises”by which the woman within her family was “truly beingconstructed, not as wife, but as mother” (Finch, 1993,p. 123). By the late 1960s in Australia, when law reformmovements were led by doctors, the iconic image of theunhygienic, dangerous “backyard” operation was ubiqui-tously deployed in lobbying, and consequently, as a given incommon and political parlance. Although there were somemen (often chemists) who performed backyard abortions(Gregory, 2004, p. 106), it was women who were demo-nised. Dr Bertraim Wainer, who advanced himself as thepublic face of abortion law reform campaigns, dramaticallypropagated the mythology of the dangerous midwife whenhe warned of the “incompetent, barbarous old lady roundthe corner” performing abortions (Baird, 1996, p. 16). Illicitabortion could of course be dangerous and deadly, and in the1940s, de Beauvoir (1997, p. 147) wrote that “it is difficult toimagine abandonment more frightful than that in which the

menace of death is combined with that of crime and shame”.Nonetheless, Baird (1996, p. 8) argues that “the rhetoricaluse of the suffering women in this context” of the barbaricmidwife “intersects far too readily with various moves by themedical and nursing professions to discredit and replacemidwives and other local women's health practitioners whoprovided a significant number of all abortions in this countrybefore law reform”.

In 1968 Wainer exposed corruption in Victoria and tried toexpose it in NSW(Riseman, 2005, pp. 14–15). Police raidswerecommenced inMelbourne to “prove” the policewere not beingbribed by abortionists. These culminated in the Davidson trialof 1969 that produced the Menhennitt ruling on lawfulabortion and saw almost all other outstanding chargesdropped (R v Davidson [1969]). In 1970 the NSW policeperformed a purge of many premises and launched numerousprosecutions that also culminated in one trial, the Heatherbraeor Wald trial. On 11 May 1970 the Heatherbrae clinic atCurlewis Street Bondi was raided “almost simultaneously”with the announcement of the formation of the police's 31manabortion squad (Sydney Morning Herald, 12 May 1970, p. 1).The surgery had been operating as an abortion clinic since the1940s. In the 1950s it became the Heatherbrae clinic — a wellknown, professional surgery that was notable for refusing tobribe the police, despite being regularly harassed to do so(Gleeson, 2009, p. 73). The police were brutal in their raid,including removing and detaining a woman who wasanaesthetised on the operating table and who went on tocontinue her pregnancy after having been denied thatabortion. Three doctors, one nurse and the two owners of theclinic were charged with 54 abortion related offences. At trial,the women called as witnesses were those who had hadabortions on the day of the raid. They included a youngwomanwhose fiancéwas serving in Vietnam; a NewAustralian (as shewas called) who was separated from her violent husband; amatron at a home for illegitimate children; and a marriedwoman who had become pregnant after having had an IUD inplace. They were “mainly middle class, and well to do” (JimStaples, personal communication, 9 Dec 2009). All had beensubjected to forced internal examinations by the police.

After hearing six weeks of evidence, Judge Levine echoedboth the Menhennitt ruling and the Bourne judgement whenhe directed the jury that “the termination of pregnancy bycompetent use of instruments in the hands of medicalpractitioners is not an offence in this state — the offence isto do it unlawfully. What the Crown must prove is that theoperation is unlawful” (Sydney Morning Herald, 28 Oct 1971,p. 9). The test, he said, was “whether there existed in the caseof each woman any economic, social or medical ground orreason which in their view could constitute reasonablegrounds upon which the doctors could honestly andreasonably believe there would result a serious danger toher physical or mental health” (R v Wald (1972)). The juryfound that all of the women who appeared as witnesses mayhave presented the doctors with reasonable grounds tobelieve an abortion was warranted to preserve their physicalor mental health, and all were acquitted. With medicalabortion once again having been affirmed by the courts, thestate's abortion squad was disbanded; medical abortionclinics came to be advertised in the Yellow Pages; and thebackyard trade was soon to be ceased.1

523K. Gleeson / Women's Studies International Forum 34 (2011) 520–529

Author's personal copy

The captured women

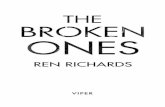

The women prisoners represented in the ReformatoryInmate photographs of the Femme Fatale exhibition werethose who had been detected and “captured” by the state priorto 1971. They represented a range of women includingmidwives, ex nurses and “women with medical knowledge ofsome kind, who may have worked with dentists'; as well as“women who were helping friends, who didn't seem to havebeen professional abortionists” (Campbell, personal correspon-dence, 11 August 2010). Their fleeting public appearances, incourt and in the intake portraits, represent only the failings andmisadventures of abortion: manslaughter; sepsis; criminalrackets gone wrong. The Justice and Police Museum draws itsartefacts from police records, and of course, most depictions ofcrime are concerned with those detained for performing it. Theabortion display felt bleak and yet not bleak: images of women,older and younger, gazing into the distance, focused apparentlybeyond the camera lens, dressed in their tatty Edwardian bestfor their day in court. Included alongside the portraits wereimages of crime scenes takenbypolicephotographers at the siteof alleged abortion crimes from the1920s to the1950s: “strangebedroom scenes [that] kept coming up” in the archived images,from dank hotel rooms to spartan medical surgeries. Theexhibition “wanted to show that yes abortionhappened indirty,dark nasty places, but it also happened in places where therewas a greater level of care and expertise; where instrumentswere being used that had been cleaned and sterilised”. Oneimage showed “quite a feminine space…. flowers and cut glass

bowls next to her disinfecting instruments”, suggesting anevocative degree of “feminine care” about the operation(Campbell, personal communication, 11 August 2010) (Fig. 1).

An exhibition of this sort may allude to the ultimateagonies associated with the crime, but this crime, arguablyunlike most others, was also associated with profound privateappreciation for deliverance amongst the women (and men)who commissioned it. Historically, the very low incidence ofpolice investigation and conviction by jury in Australia forabortion offences in the absence of a gravely harmed patient,suggest that the general public has never conclusivelyunderstood or appreciated the legally demarcated victims ofthe crime. However, this appreciation of the abortionist andher work is not palpable within the display “that may disturbsome visitors”, and in its absencewhat remains in depiction ismerely a shadow of a sophisticated world of women's affairs,of life and death decision-making. All the images in theabortion display provided a glimpse of a world not only ofhidden women's business, but also of women's mortal andmoral authority, which had prevailed in various forms untilthe patriarchal medical appropriation of reproduction andbirth was completed by the middle of the 20th century.

The women abortionists photographed as inmates of theState Reformatory constituted perhaps the last (or second last)generation of women who had worked as custodians of life inways that had for centuries perturbed and threatened theestablished regimes of the churches and the medical pro-fessions. She decreed to be of “most harm” to the earlymodernCatholic faithwas reconfigured to be of “most harm” towomen

Fig. 1. Surgical equipment beside vase of flowers and a mirror inside a room used to conduct abortions, 14 December 1964, photographer unknown. NSW PoliceForensic Photography Archive, Justice and Police Museum, Historic Houses Trust.

524 K. Gleeson / Women's Studies International Forum 34 (2011) 520–529

Author's personal copy

by the 1960s; and feminist historians argue that what was(also) at risk of most harm throughout the 19th and 20thcenturies (and perhaps the middle ages) was the maledominated medical profession, dependent for legitimacy onits absolute authority over the body and reproduction. At a timewhen the Church was relinquishing and losing its absoluteauthority over some, post Vatican II, the medical professionconsolidated its own. This foe, armed with medical andscientific advancement proved formidable for midwifery inthis arena. The power of women that the church had failed tosuppress, the medical establishment, working in concert withthe secular law, ultimately did. The captured abortionistsappeared weak and despondent; their authority in theircommunities and within their professions had been under-mined and sullied by their verdicts. They may have given up. Isthis what may be disturbing to some visitors? Or is it, perhaps,the sexual and mortal knowledge of the abortionist (Fig. 2)?

The threat of women's sexual knowledge

Along with statements made about their carnality andintellectual childishness, the Malleus Maleficarum also identi-fied women as the preferred targets of the Devil because “theyhave slippery tongues, and are unable to conceal from thefellow women those things which by evil arts they know”

(Institoris & Sprenger, 2006, p. 44). We are but gossips. In this

view, bewitched women would seduce more women to thecraft by sharing their knowledge of it. It is correct thatwomen'sabortion networks work by word of mouth, and the fear of thepower of sexual knowledge lies at the heart ofmuch oppositionto its deployment. But does the very imagery of archaic, illicitabortion continue to pose a danger to the social order? Howmay it continue to disturb? Long before Foucault observed that“knowledge is power”, Abrahamic religiousmythology decreedthat woman's knowledge, indeed her sexual knowledge,wrought man's destruction, in the fall from grace. Theconnections made between carnality, sexual knowledge, andwomen's sorcery were understood as absolute by the earlymodern witch hunters, and almost “without exception” thosewho wrote about witchcraft in this era “reminded readers thatit was Eve who had first been seduced into sin, and Adamwhoin turnwas temptedbyEve”; someauthors identifiedEve as thefirstwitch (Clarke, 1997, p. 121).Women's sexual knowledge ismagically dangerous to men, and feminist psychoanalytic andphilosophical theories help to explain some of the threat ofabortion (its associated knowledge, its practise and itsrepresentation) to patriarchal regimes built on the myth ofmale power. Creation mythology strives desperately to denywomen's designof life. Evewasbornnot only ofman, but of andas a defectofman: fromabent rib. Christwas carried, but hardlycreated, by a virgin. God the Father directed the whole show.Was Eve's catastrophic sexual knowledge nothing other than

Fig. 2. Janet Wright, convicted of using an instrument to procure a miscarriage. Criminal record number 737LB, 16 February 1922. State Reformatory for Women,Long Bay, NSW photographer unknown. NSW Police Forensic Photography Archive, Justice and Police Museum, Historic Houses Trust. Wright was a former nursewho performed abortions from her house in Kippax Street, Surry Hills. One of her teenage patients almost died after a procedure and Wright was prosecuted andsentenced to 12 months hard labour. Aged 68.

525K. Gleeson / Women's Studies International Forum 34 (2011) 520–529

Author's personal copy

her acknowledgement of her ideologically and spirituallytreacherous feminine creative capacities?

Rosalind Pollack Petchesky summarises feminist analyseswhich have explained masculine appropriation of theconditions and products of reproduction in psychoanalyticor psychological terms,

associating it with men's fears of the body, their ownmortality, and the mother who bore them. According toone interpretation ‘the domination of women by the malegaze part of men's strategy to contain the threat that themother embodies [of infantile dependence and maleimpotence]’. Nancy Harstock in a passage reminiscent ofSimone de Beauvoir's earlier insights, links patriarchalcontrol over reproduction to the masculine quest forimmortality through immortal works: ‘Because to be bornmeans that one will die, reproduction and generation areeither understood in terms of death or are appropriatedby men in disembodied form’ (Petchesky, 1987, p. 278).

More so than conception or birth imagery, abortion imageryperforms an undeniable reminder that it is a woman's body, ifnot always a woman's consciousness, which determines lifeand not-life, from the commencement of existence. Theunconscious nature of conception – that fact that we cannotchoose to conceive at a given moment, nor may we choose the“particular child who grows inside [us]” – may lead to thecategorisation of woman as an agent “less virile” than man, ofan existence “overtaken by nature, condemned to repeat itselffor the sake of the species” (Guenther, 2006, pp. 16–19). In deBeauvoir's analysis, for example, women's creative empower-ment through gestation and birth is illusory (Guenther, 2006,p. 19). But the nature of induced abortion undeniably situateswoman as the moral arbiter and rational agent emboldenedwith decision-making about conception and creation: decisionsdetermining a welcomed or denied existence; and/or thegraceful acceptance of another into one's body, life and psyche.Whilst Nancy Harstock and others are correct to note thepsychoanalytic realisation of mortality provoked by the con-frontationof female reproduction, there arepolitical concerns atstake in the control of reproductive choices, and their portrayal,which impact on the structure and ordering of society as well.

Lisa Guenther (2006, p. 75) reminds us that

the fact remains that in the history of the West, womenhave long been expected to exist for-the-Other, and oftenprevented from ever existing in-and-for-themselves. Onlyin recent decades have women been able to approach the‘virile’ possibilities that have been the prerogative – andthe ethical pitfall – of European men for centuries.Women have for too long been expected to give selflesslywithout reciprocation and as the seemingly naturalconsequence of social or biological imperatives.

Induced abortion defies this sexed expectation of selfdenigrating altruism; of women's agency self non-regarding.When performed by women, and of women ascribing toindividual private moralities, obscured from the gaze of thestate and the medical establishment, abortion is power: therejection of “enforced maternity” (de Beauvoir, 1997, p. 502).

The disempowered, disengaged gaze of the captured abor-tionist is a red herring. This no doubt is confronting, and maydisturb some visitors.

The power of abortion imagery

The power of abortion imagery is understood by thosewho oppose the practise of pregnancy termination. KarynSandlos (2000, p. 77) argues that it “would be difficult tolocate a political struggle in which images have played amorecentral role than they have in debates over reproductivechoices”. A conservative fear of sexual knowledge andwomen's networks that might have deterred the use ofsuch imagery in the past, was overcome in welcome responseto ultrasound foetal imaging technologies, which have beendeployed in what (Petchesky, 1987, p. 263) identifies as theuse of imagery by the “political attack on abortion rights”.This strategy, aimed to distance abortion from connotationsof women's bodies and/or reproductive decision making, wasinspired first by Look magazine's 1965 publication ofembryonic/foetal development photographs, which depictedpregnancy as wholly separated fromwomen, by focusing on adisembodied embryonic sac and its contents. Through suchimages, anti abortionists strive to represent the foetus in a“culture war over the social meaning of abortion” (Weitz,2010, p. 162) “as primary and autonomous; the woman asabsent or peripheral” (Petchesky, 1987, p. 268) in pregnancy.This aims to “humanise the foetus” (Weitz, 2010, p. 162) andmake “foetal personhood a self fulfilling prophecy by makingthe foetus a public presence” in a visually oriented culture(Petchesky, 1987, p. 263).

Conveniently, this imaginingof the foetus goeshand inhandwith the ideology of the medical colonisation of abortion, andPetchesky (1987, p. 263) notes the “conscious strategic shiftmade by anti abortionists away from religious discourses andauthorities tomedico technical ones, in its effort towinover thecourt, the legislatures and popular hearts and minds”. Theimageof a solitary foetus,which “effaceswomen's reproductivebodies” is a crucial component of this strategy in which the“pregnant woman is increasingly put in the position ofadversary to her own pregnancy/foetus” (Newman, 1996,p. 8) and medicine and science are positioned as the rightfulchampions of the foetus. For Petchesky (1987, p. 264), suchphotographs and images epitomise the

distortion inherent in all photographic images: theirtendency to slice up reality into tiny bits wrenched outof real space and time. The origins of photography can betraced to late nineteenth century Europe's cult of science,itself a by-product of industrial capitalism. Its rise isinextricably linked with positivism, that flawed episte-mology that sees ‘reality’ as discrete bits of empirical datadivorced from historical process of social relationships.Similarly, foetal imagery replicates the essential paradoxof photographs whether moving or still, the ‘constitutivedeception’ as noted by postmodernist critics the appear-ance of objectivity of capturing ‘literal reality’.

Petchesky (1987, p. 264) urges that to combat such antiabortion strategies, “first we have to restore women to a

526 K. Gleeson / Women's Studies International Forum 34 (2011) 520–529

Author's personal copy

central place in the pregnancy scene”, from where they havebeen displaced. This displacement was in part facilitated bythe development of medical technical imaging which first“captured” the foetus, a development that coincided in timewith the medical profession's conclusive “capturing” ofabortion (and reproduction) throughout the western world.The medical colonisation of reproduction was facilitated byboth the displacing of the pregnant woman from the centre ofpregnancy (in Petchesky's analysis), and the displacement ofwomen from the moral and technical authority overchildbirth and abortion. In both instances, medical abortionimagery has been crucial to this process. In fact, medicalisedabortion imagery, invoking sterility and surgery, and sepa-rated from the body and women's lives, was arguablyinstrumental in securing the legal protection of medicalabortion services that followed the 1971 Heatherbrae Clinicabortion trial.

Jim Staples was a solicitor at the trial, representing theowners of the clinic. Staples recalls that the public prosecutorof the case opened his address by affirming medical authorityover abortion, clarifying that the Crown did not deny thepossibility of lawful abortions performed by doctors. Theprosecutor recognised and conceded immediately that“Heatherbrae was better equipped than any other publichospital to do this work.…The three doctors we've chargedare doctors who have the highest repute professionally inMacquarie Street. So don't lets have any talk that this was agrubby little hovel where this was going on, or a back room,or an attic” (Staples, personal communication, 9 December2009). But still he alleged the doctors had performedterminations unlawfully. Photographs of the crime scenewere tended in evidence to help the jury “get someunderstanding of the where the procedures took place”, andStaples was simply “stunned”when he saw the photographs:

Everything about abortion was more or less grubby in mysocial experience. And what am I presented with in thesephotographs, but photographs of what [the prosecutor]had already conceded was the best hospital in Sydney.There was stainless steel everywhere. There werepolished floors; there were clean beds and linen; light-ness and brightness and windows. It was stunning. Ilooked and I thought, ‘my God. Where's the crime?’Looking at this stuff, and knowing who the people werewho were charged over it….How could the criminal lawpossibly provide against this situation? (personal com-munication, 9 December 2009).

Staples believed that the jury also could not see the crime,in the images, or in the testimonies of the witnesses, or evenin the prosecution's address, which conceded there was “nocomplaint from the women. No harm done. Nothing tawdryabout the affair. And [done in] good premises” (personalcommunication, 9 December 2009). This sterile imagery,when presented to an all male jury, apparently did not disturbthese twelve purveyors of the world of women's reproductivedecision making in Sydney in 1971.

The Heatherbrae trial affirmed the rationale of themedical safety and authority of the abortion procedure. Itprovided for the ending of private (hidden), illicit and

extortive abortion practises in NSW. Importantly, in notstipulating that abortion must be performed in a hospital,or that two doctors must agree on the need for theprocedure, the Levine ruling paved the way for the state'sfunding of openly feminist (medical) abortion servicessuch as Leichhardt Women's Health Centre and thePreterm Clinic: progressive developments that were lea-gues ahead of the revolutionary South Australian reformstwo years prior, and which also benefited from theWhitlam government's scheduling of abortion proceduresin Medibank in 1974. But at the same time, the ruling alsoconfirmed that legally, and in terms of common percep-tions, abortion is sensibly the preserve of the medicalprofession.

The safety and dignity of state subsidised professionalmedical abortion is a critical component of women's humanrights, but the wholesale medicalisation of reproduction,pregnancy and birth is not without criticism. At the time ofthe ruling, women's liberation activists were agitating for therepeal of all abortion laws (Coleman, 1988, p. 79), not for themedical subscribing of its authority. As Guenther (2006,p. 41) notes,

The displacement of reproduction from the private to thepublic sphere does not automatically ‘liberate’ birthingwomen, but can actually subject them to increasedmedical and social surveillance and decreased authorityover the legal and political significance of their ownpregnant bodies.

Medicalisation undoubtedly appeared to be a morepolitically palatable abortion regime than a world of privatewomen's business, which had carried with it the undesirabletrappings of the clandestine: physical dangers, politicalscandals and organised criminal elements. But its effectshave been more widespread and meaningful than a simpleneutralisation of criminality and morbidity. The relocation ofthis private female activity in the public patriarchal arena ofmedical authority has also shifted the moral agency of thedecision-making process about life and not-life, birth andnot-birth, to one of medical necessity, or more likely, medicalpermission. It has neutralised women's perceived and actua-lised individual power in this existential realm, whilstelevating medicine's totality. Like the anti abortion imagerycentred on the disembodied foetus, the medical imagining ofabortion, all sterility and stainless steel, removes the womanfrom the picture.

Putting women back in the picture: sharing the secret ofabortion

Women write about abortion in many ways, just as theyexperience it in many ways. This includes, as an issue ofreproductive health, and medicine, of sexual activity andhuman rights. de Beauvoir (1997, p. 502) famously described itas an “especially desperate remedy”. But women also describethe experience of pregnancy and abortion in terms of uniquelyfeminine “intimacy” (Little, 1999) and questions of a femininewelcoming of another (Guenther, 2006). For Margaret Little(1999, p. 295), “to be pregnant is to be inhabited. It is to

527K. Gleeson / Women's Studies International Forum 34 (2011) 520–529

Author's personal copy

be occupied. It is to be in a state of physical intimacy of aparticularly thorough-going nature”. For feminist philosopherCatriona Mackenzie (1992, p. 136), “questions of women'sautonomy lie at the heart of the abortion issue”. In most formaldiscussions of abortion, however, be they legalistic, medical,philosophical or political, “the central figures in the abortiondrama – foetus, gestating woman, and their relationship – areleft out of the conceptual paradigm” (Little, 1999, p. 296.Emphasis added). Many feminist arguments for the continuedlegal protection of abortion therefore rely on the iconographyof the horror for women of abortion before legalisation, inorder to put women “back in the picture”, or the debate, aboutabortion.

For example, Drucilla Cornell (1995, p. 38) argues that“the denial of the right to abortion should be understood as aserious symbolic assault on a woman's sense of self”. Centralto Cornell's (1995, p. 44) rationale is her characterisation ofillicit abortion as “a full horror” of “self betrayal” whenperformed not by the lawfully empowered, but by oneoneself on one's own body. In a similar tactic, catastrophicabortion imagery has been deployed by feminists combatingfoetal focused imagery. In 1973 (and again in 1995 and 1997)Ms Magazine published the now iconic photograph of GerriSantoro's dead body, after it was found “abandoned on ahotel room floor after an illegal and subsequently fatalabortion” (Sandlos, 2000, p. 77). The justification for thepublication of the image was that “in the context of thepowerful and outrage-eliciting images of dead foetusesemerging from the pro-life movement of the early 1970s, aphotograph of a woman dead from an illegal abortionprocedure presented a timely and important opportunityfor pro-choice activists to make visible the material violenceof women's restricted access to reproductive choice” (Sandlos,2000, p. 83). At the time it was felt that “an image of a deadwoman responds to this construction in a striking fashion, byinserting women's bodies back into the image repertoire”. Theimage was “plastered on placards” and displayed at pro-choicerallies across the United States, and elsewhere, for two decades(Sandlos, 2000, p. 83).

Do these types of images and descriptions confrontbourgeois hypocrisy about abortion? Arguably, feminist strat-egies evoking deadly, dangerous and desperate scenarios, havebeen effective in puttingwomen back in the picture of abortionrhetoric (and perhaps policy considerations), by suggestingthat the life and death question of abortion concerns womenforemost (not the foetus). But as Sandlos (2000, p. 83) notes,such a “reiteration of the foetus/woman dichotomy” does notcentre abortion debates on the woman herself. It serves toconstruct the “coherence and boundedness of competing sidesof abortion debates in which both pro-choice and anti-choicesubjects are produced through their alignmentwith clearmoralpositionson thecomplicated reproductive issues atplay”. It alsoserves to reinforce the idea that medicalisation of abortion isinherently linked to women's human rights, and therefore,their empowerment.

In contrast to these types of representations, the FemmeFatale exhibition did not show female victims of malpractice,or the female patients who commissioned the crimes ofabortion. Campbell, the curator, was more concerned with“the ways we in society portray women as criminals….andsome of the realities faced by the female criminals”: those

who were captured and “contained” by the state for theircriminality. Rather than provoke a heightened or shockingemotional response, she aimed to

strip the emotion from it. Because it's already such anemotional topic. We wanted to present it as a crime, asthe police saw it. And also highlight the fact that its legalstatus was still in dispute [before 1971]. And that wassomething I think people were unaware of, particularlyyounger women. They had grown up with friends whohad abortions, and Medicare paid for it. They justassumed that it was a right (Campbell, personal commu-nication, 11 August 2010).

The exhibition was not confronting and harrowing in theways the image fromMs Magazinemight be experienced. The“emotional” and religious aspects of abortion perceptionsperhaps accounts for the abortion display being sectionedfrom the rest of the exhibition, but the imagery deployed didnot invoke terror in the ways that Gerri Santoro's dead bodyshould. The seclusion of abortion imagery is not only aboutwhat is disturbing in this sense. This seclusion also evokes thespecial secretness of abortion crimes, the open secrets of pastprivate lives, and the power contained in this hiddenwomen's business: a power that has perturbed society sinceat least the middle ages. The display in fact facilitated thesharing of this secret. In response to the abortion display, theJustice and Police Museum received

a lot of the feedback from women in their 60s onwards.They would actually talk about abortion. They weretalking amongst themselves because this was very muchof their experience — illegal abortion was. They allseemed to know of someone who had had an illegalabortion. They'd know of people who had had horrendousoutcomes from illegal abortions. And they were quitehappy to talk about it. You know, it was just part of theirhistory. ‘Do you remember so-and-so? That's whathappened to her’ (Campbell, personal communication,11 August 2010).

According to Campbell, the feedback was “quite positive”from women who “wanted to share their experiences… Somereally difficult experiences. It was quite cathartic, I think”(personal communication, 11August 2010). In 2010 the FemmeFatale exhibition received Commonwealth Vision funding toallow it to travel for 18 months to regional and rural areasacross Australia, where it continues to provoke the sharing ofsecrets.

The medicalisation of abortion (and reproduction) hasapparently closed a chapter on women's history in thewestern world. Abortion, when criminalised, was a specialcrime, overlayed with gratitude and individualistic, oftencircumstantial and contextualised experiences of its moralityand right or wrongdoing. As the fears of the witch huntersmake clear, women's control of reproductive decisionmakingis threatening to patriarchal orders in ways that other“crimes” or transgressions simply are not. Whilst it isundoubtedly proven that illicit abortion regimes harmwomen, Baird (1996, p. 22) argues that although the image

528 K. Gleeson / Women's Studies International Forum 34 (2011) 520–529

Author's personal copy

of the deadly unskilled “backyarder has served the law reformand pro-choice movements well, this has been at the cost of amore nuanced history of the pre law reform period, andconsequently at the cost of an unquestioned monopoly of themedical profession over the actual provision of abortionservices that is, the flesh and blood of the matter”. A rejectionof bourgeois hypocrisy about abortion would involve therecognition of this nuanced history, in which women not onlywere victims of illicit regimes, but in which very manyabortionists were treasured, or valued, members of their(female) communities; and in which they were targeted bythe medical, religious and legal establishment for their power.

End Note

1 After Heatherbrae prosecutions for abortion continued in NSW butwhere they concerned medical practitioners charges related to conspiracy,and none were upheld. Only “backyarders” were convicted of procuring. In1972 notorious Macquarie Street doctor, George Smart, was sent to trial on54 counts of unlawfully performing abortions. Smart was an institution inthe Sydney abortion sector throughout the 1960s and 1970s but increas-ingly, as he aged, he was considered to be reckless and perhaps deadly whenperforming abortions. Justice Levine was to hear the case, but suffered aheart attack that eventually killed him. At the new trial, charges werereduced to 24, the jury could not agree and Smart was acquitted on allcounts (Coleman, 1991, p. 220). The failure to convict in the case of Smart in1972 is thought to have discouraged the Askin-era police from pursuingdoctors after the initial purge of 1970. Whilst the Heatherbrae service wasfaultless, Smart was not, and still the jury did not convict. By 1974 and theopening of Preterm clinic, the backyard trade was increasingly irrelevant.There have been two convictions of doctors since this time — George Smartagain in 1984 and Dr Suman Sood in 2006. Both were found guilty ofperforming an abortion unlawfully, because they failed to question thewoman about the circumstances of her pregnancy and need for an abortion(Gleeson, 2009).

References

Allen, Judith (1990). Sex and secrets: Crimes involving Australian women since1880. Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

Baird, Barbara (1996). “The incompetent, barbarous old lady round thecorner”: The image of the backyard abortionist in pro-abortion politics.Hecate, 22(1), 9–11.

Clarke, Stuart (1997). Thinking with demons. The idea of witchcraft in earlymodern Europe. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Coleman, Karen (1988). The politics of abortion in Australia: Freedom,church and state. Feminist Review, 29, 75–97.

Coleman, Karen (1991). Discourses on sexuality: The modern abortiondebates. Phd Thesis, Macquarie University.

Cook, Hera (2000). Unseemly and unwomanly behaviour: Comparingwomen's control of their fertility in Britain and Australia. Journal ofPopulation Research, 17(2), 125–141.

Cornell, Drucilla (1995). The imaginary domain. Abortion, pornography andsexual harassment. New York: Routledge.

de Beauvoir, Simone (1997). The second sex. Translated and edited by HMParshley. London: Vintage.

Ehrenreich, Barbara, & English, Deidre (1973). Witches, midwives and nurses.A history of women healers.. New York: The Feminist Press.

Finch, Lynette (1993). The classing gaze. Sydney: Allen & Unwin.Finch, Lynette, & Stratton, Jon (1988). The Australian working class and the

practice of Abortion 1880–1939. Journal of Australian Studies, 12(23),45–64.

Gleeson, Kate (2009). The other abortion myth: The failure of the commonlaw. Journal of Bioethical Inquiry, 6(1), 69–81.

Gleeson, Kate (2011). The strange case of the invisible woman in abortionlaw reform. In Jackie Jones, Anna Grear, Kim Stevenson, & Rachel Fenton(Eds.), Gender, sexualities and law (pp. 215–226). London: Routledge.

Gregory, Robyn (2004). Corrupt cops, crooked docs, prevaricating pollies and“mad radicals”: A history of abortion law reform in Victoria, 1959–1974.PhD Thesis. Melbourne: RMIT University.

Gregory, Robyn (2007). Hardly her choice: A history of abortion law reformin Victoria. Women Against Violence, 19, 62–71.

Guenther, Lisa (2006). The gift of the other: Levinas and the politics ofreproduction. New York: State University Of New York Press.

Historic Houses Trust (2008). Femme fatale: The female criminal. Sydney:Historic Houses Trust.

Institoris, Henricus, & Sprenger, Jacobus (2006).Malleusmaleficarum, Edited andTranslated by Christopher Mackay. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

King v Bourne [1939] 1 KB 687.Little, Margaret Olivia (1999). Intimacy and the duty to gestate. Ethical Theory

and Moral Practice, 2(3), 295–312.Mackenzie, Catriona (1992). Abortion and embodiment. Australasian Journal

of Philosophy, 70((2), 136–155.Newman, Karen (1996). Fetal positions: Individualism, science, visuality.

California: Stanford University Press.Petchesky, Rosalind Pollack (1987). Fetal images: The power of visual culture

in the politics of reproduction. Feminist Studies, 13(2), 263–292.R v Davidson [1969] VR 667.R v Wald (1972) 3 DCR (NSW) 25.Riseman, Noah (2005). Medical choice: The Australian movement to legalise

abortion 1967–80. Lilith, 14, 92–104.Russell, Jeffrey, & Alexander, Brooks (2007). A new history of witchcraft:

Sorcerers, heretics & pagans. London: Thames & Hudson.Sandlos, Karyn (2000). Unifying forces: Rhetorical reflections on a pro-choice

image. In Sarah Ahmed, Jane Kilby, Sylvia Lury, Maureen McNeil, &Beverly Skeggs (Eds.), Transformations: Thinking through feminism(pp. 77–91). New York: Routledge.

Sydney Morning Herald, 12 May 1970, 1.Sydney Morning Herald, 28 Oct 1971, 9.Weitz, Tracy A. (2010). Rethinking the mantra that abortion should be “safe,

legal and rare”. Journal of Women's History, 22(3), 161–172.

529K. Gleeson / Women's Studies International Forum 34 (2011) 520–529