Can parental monitoring and peer management reduce the selection or influence of delinquent peers?...

Transcript of Can parental monitoring and peer management reduce the selection or influence of delinquent peers?...

Developmental Psychology

Can Parental Monitoring and Peer Management Reducethe Selection or Influence of Delinquent Peers? Testingthe Question Using a Dynamic Social Network ApproachLauree C. Tilton-Weaver, William J. Burk, Margaret Kerr, and Håkan StattinOnline First Publication, February 18, 2013. doi: 10.1037/a0031854

CITATIONTilton-Weaver, L. C., Burk, W. J., Kerr, M., & Stattin, H. (2013, February 18). Can ParentalMonitoring and Peer Management Reduce the Selection or Influence of Delinquent Peers?Testing the Question Using a Dynamic Social Network Approach. Developmental Psychology.Advance online publication. doi: 10.1037/a0031854

Can Parental Monitoring and Peer Management Reduce the Selection orInfluence of Delinquent Peers? Testing the Question Using a Dynamic

Social Network Approach

Lauree C. Tilton-WeaverÖrebro University

William J. BurkRadboud University Nijmegen

Margaret Kerr and Håkan StattinÖrebro University

We tested whether parents can reduce affiliation with delinquent peers through 3 forms of peermanagement: soliciting information, monitoring rules, and communicating disapproval of peers. Weexamined whether peer management interrupted 2 peer processes: selection and influence of delinquentpeers. Adolescents’ feelings of being overcontrolled by parents were examined as an additional moder-ator of delinquent selection and influence. Using network data from a community sample (N � 1,730),we tested whether selection and influence processes varied across early, middle, and late adolescentcohorts. Selection and influence of delinquent peers were evident in all 3 cohorts and did not differ instrength. Parental monitoring rules reduced the selection of delinquent peers in the oldest cohort. Asimilar effect was found in the early adolescent cohort, but only for adolescents who did not feelovercontrolled by parents. Monitoring rules increased the likelihood of selecting a delinquent friendamong those who felt overcontrolled. The effectiveness of communicating disapproval was also mixed:in the middle adolescent network, communicating disapproval increased the likelihood of an adolescentselecting a delinquent friend. Among late adolescents, high levels of communicating disapproval wereeffective, reducing the influence of delinquent peers for adolescents reporting higher rates of delin-quency. For those who reported lower levels of delinquency, high levels of communicating disapprovalincreased the influence of delinquent peers. The results of this study suggest that the effectiveness ofmonitoring and peer management depend on the type of behavior, the timing of its use, and whetheradolescents feel overcontrolled by parents.

Keywords: parental monitoring, peer management, adolescence, delinquency, peer influence

During adolescence, rates of delinquent behaviors increase, pos-ing considerable costs to individuals and society alike. The delin-quent behaviors of an adolescent’s friends are one of the mostrobust predictors of an adolescent’s own delinquency (e.g., Ag-new, 1991). Thus, one of the more common ideas for reducingadolescents’ delinquent behavior is to interrupt contact with de-

linquent peers (Fletcher, Darling, & Steinberg, 1995). In thisarticle, we describe our test of whether the parenting behaviorsthought to reduce contact and influence of delinquent peers—monitoring and communicating disapproval—are effective.

Parental Monitoring and Peer Management DuringAdolescence

The idea that parents can reduce negative peer influences isfound in both the parental monitoring and peer management liter-atures. Specifically, it has been suggested that parents shouldmonitor or seek information about their adolescents’ activities andassociates and, when peers are sources of delinquent influence,limit contact with delinquent peers (Fletcher et al., 1995). In themonitoring literature, these parenting behaviors have been studiedas two constructs: solicitation and control (or monitoring rules;e.g., Kerr & Stattin, 2000; Kiesner, Poulin, & Dishion, 2010). Inpeer management research, they have been studied as (a) moni-toring or seeking information and (b) prohibiting or communicat-ing disapproval (Mounts, 2000; Tilton-Weaver & Galambos,2003). Essentially, the idea is that parents should first attempt tofind out what their adolescents are doing and whom they are with.That is, they should monitor, seek information, solicit, or make

Lauree C. Tilton-Weaver, Center for Developmental Research, Instituteof Law, Psychology, and Social Work, Örebro University, Örebro, Swe-den; William J. Burk, Behavioural Science Institute, Radboud UniversityNijmegen, Nijmegen, the Netherlands; Margaret Kerr and Håkan Stattin,Center for Developmental Research, Institute of Law, Psychology, andSocial Work, Örebro University.

Margaret Kerr died prior to the completion of this article. We gratefullyacknowledge her contributions to the research.

Support for this research was provided by the Swedish Research Council(Vetenskapsrådet), the Swedish Council for Working Life and SocialResearch (FAS), and Örebro University.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Lauree C.Tilton-Weaver, Center for Developmental Research, School of Law, Psy-chology, and Social Work, Örebro University, Örebro 701 82, Sweden.E-mail: [email protected]

Developmental Psychology © 2013 American Psychological Association2013, Vol. 49, No. 4, 000 0012-1649/13/$12.00 DOI: 10.1037/a0031854

1

rules about their adolescents disclosing this information to them.When parents are aware of problematic peers, they should limitadolescents’ involvement with these peers by prohibiting contactor communicating disapproval of these peers. For the sake ofsimplicity, we refer to these behaviors as monitoring (includingsolicitation and monitoring rules) and communicating disapproval.In the literatures, then, there is a clear idea that parents can limitcontact with or influence of delinquent peers by soliciting infor-mation, making rules about providing information, and communi-cating disapproval of adolescents’ peers.

Despite clear ideas about how monitoring and communicatingdisapproval should work, the evidence supporting the idea hasbeen challenged in several ways. First, scholars have questionedconclusions about the effectiveness of monitoring because themost widely used measures of monitoring assess parental knowl-edge of adolescents’ activities (Kerr & Stattin, 2000). Studies haveshown that parents gain knowledge primarily from adolescents’disclosure, rather than from monitoring (Keijsers, Branje, Van derValk, & Meeus, 2010; Kerr, Stattin, & Burk, 2010; Marshall,Tilton-Weaver, & Bosdet, 2005),1 suggesting that monitoringmight not be as straightforward as previously thought.

Second, much of the research used to conclude that the moni-toring idea is effective has used cross-sectional data. Certainly,solicitation, monitoring rules, and communicating disapprovalhave been linked to adolescent and peer delinquency cross-sectionally (e.g., Bank, Burrastan, & Snyder, 2004; Kiesner et al.,2010; Mounts, 2000, 2002; Soenens, Vansteenkiste, Smits, Lowet,& Goossens, 2007; Tilton-Weaver & Galambos, 2003). However,longitudinal data are needed to examine change in behaviors.Moreover, research needs to focus on how monitoring and peermanagement relate to change in peer processes associated withdelinquency.

Adolescents who engage in delinquent activities associate withdelinquent peers (Agnew, 1991). This robust finding reflects aform of homophily, or the tendency for friends to exhibit similarlevels of behavior. Like other forms of homophily, the tendencyfor adolescents to have friends with similar levels of delinquencyhas two potential sources: (a) peer selection, where adolescentsbefriend individuals who are similarly delinquent prior to theformation of the relationship and (b) peer influence, where ado-lescents become more similar to their friends over time, engagingin more delinquency when friends are delinquent (Kandel, 1996).Peer selection involving delinquent behaviors is thought to emergein early adolescence and remain a predictor of friendship through-out adolescence (Dishion & Owen, 2002). Conversely, delinquentpeer influence is thought to increase until middle adolescence anddecline thereafter (Berndt, 1979). Most researchers agree that theseprocesses operate in a complementary manner to predict similaritybetween friends’ delinquency throughout adolescence. For re-searchers to understand how parenting affects affiliation withdelinquent peers, then, these processes need to be studied simul-taneously.

Most of the longitudinal research meant to shed light on howmonitoring or peer management is related to delinquent peers hasnot focused on selection and influence. Some researchers haveexamined how solicitation is associated with having problematicpeers (e.g., Rodgers-Farmer, 2001) but have failed to account forbaseline levels. Others have examined change, controlling forbaseline levels or examining trajectories of change in peers’ de-

linquency but have used measures such as alcohol co-use (Kiesneret al., 2010) that preclude the separation of selection and influenceeffects. In only a handful of studies have researchers modeledchange in adolescents’ behavior while controlling for their friends’behavior or vice versa. The results of studies using these strategieshave produced a mixed picture. In the only study on solicitation,there was no evidence that this form of monitoring affected theinfluence of delinquent peers (i.e., substance-using peers; Fairlie,Wood, & Laird, 2012). Studies of monitoring rules paint a similarpicture, as having such rules has not been significantly related tohaving delinquent friends (Keijsers et al., 2012). However, in astudy using a measure including both solicitation and rules,changes in monitoring were negatively related to changes infriends’ smoking (Simons-Morton, Chen, Abroms, & Haynie,2004), suggesting that monitoring reduces the influence of smok-ing friends. Despite assertions that monitoring reduces affiliationwith delinquent peers, the evidence is not so clear.

Regarding communicating disapproval, several studies suggestthat both selection and influence may be affected. In a recent studyof 12- to 18-year-olds, prohibiting contact was associated withincreased contact with delinquent peers (controlling for adoles-cents’ own delinquency) and, indirectly, to increases in adoles-cents’ own delinquency (Keijsers et al., 2012). This finding sug-gests that prohibiting contact increases the influence of delinquentpeers during adolescence, effects that are inconsistent with themonitoring perspective. Other studies both support and contradictthese findings. In several different samples of seventh graders,Mounts found different relations between communicating disap-proval and the influence of delinquent or substance-using peers,including decreased influence of drug-using peers (2001), in-creased influence of delinquent (2001) and drug-using (2002, forthose with uninvolved parents) peers, and no significant relationsbetween communicating disapproval and changes in substance use(2001). Results of studies using these strategies, then, do notprovide a clear picture either.

The lack of clarity in the empirical record may be due to the useof analytic strategies that only indirectly assess peer selection andinfluence and do not account for the social processes operatingwhen delinquents meet, become friends, and influence each other.Newer methods, developed to address the complexity of socialnetwork processes, reduce the bias introduced by using adoles-cents’ reports of their friends’ behaviors (Kandel, 1996), by esti-mating selection and influence in separate analyses, and by treatingrelationships of different lengths as similarly influential. Socialnetwork analysis also allows researchers to control for structuralaspects of social networks that might inflate estimates of selectionand influence. For example, when adolescents choose their friends,they are more likely to select from among people they alreadyknow, and these might be friends of their own friends. The ten-dency to befriend the friend of a friend must be controlled to knowwhether an adolescent is selected as a friend because of his or herdelinquency or because of a friend in common. In the end, networkanalysis yields a clearer picture of selection and influence pro-

1 Given that research suggests that parental knowledge is largely pre-dicted by adolescents’ disclosure, we have not included it as a construct ofinterest and do not review the literature on knowledge as a moderator ofdelinquent peer processes.

2 TILTON-WEAVER, BURK, KERR, AND STATTIN

cesses, allowing researchers to directly test if parenting alterswhom adolescents select as friends and by whom they are influ-enced.

Most of the studies that have used network analysis to examinedelinquency-based selection and influence have found evidencefor the importance of both mechanisms (Baerveldt, Völker, & VanRossem, 2008; Burk, Kerr, & Stattin, 2008). However, the net-works in these studies consisted of a single cohort of similarlyaged adolescents attending the same class or grade within individ-ual schools (see Burk et al., 2008, for an exception). To ourknowledge, only one study exists in which multiple cohorts acrossadolescence were examined. In that study, researchers found evi-dence for selection related to problematic drinking behaviors insamples of early, middle, and late adolescents, with somewhatstronger effects in early adolescence than middle and late adoles-cence (Burk, Van der Vorst, Kerr, & Stattin, 2012). Although theinfluence of drinking peers did not reach significance until middleadolescence, the degree of influence did not differ across the threeage groups. Given that studies investigating more generalizedmeasures of delinquency reflect patterns that are most similar todrinking behaviors, the results of Burk et al. (2012) suggested thatselection of delinquent peers might differ in strength across ado-lescence. Unlike previous research, however, their results suggestthat delinquent peer influence does not differ across adolescence.Determining the strength of selection and influence is importantbecause peer management may be most effective when theseprocesses are weakest.

From this review, it can be seen that the question of whethermonitoring and communicating disapproval can reduce the selec-tion or influence of delinquent peers has not been fully addressed.To do so, research is needed that (a) disentangles selection andinfluence processes, (b) systematically determines whether thesepeer processes differ across adolescence, and (c) tests whethermonitoring or communicating disapproval moderates adolescents’friendship choices or the deviant influence of already-selectedfriends.

How might monitoring or communicating disapproval moderateadolescents’ selection of delinquent peers or the tendency to beinfluenced by them? One possibility is that monitoring and peermanagement reduce both peer processes. This might be true ifparents are viewed as legitimate authorities over friendships. Earlyadolescents are more accepting of parental authority over friend-ship than middle or late adolescents (Smetana & Asquith, 1994).Thus, one hypothesis is that peer management is effective butmainly in early adolescence. In contrast to this hypothesis, there isgood reason to expect that monitoring and peer management mightactually backfire. When parents attempt to control friendships,particularly when they communicate disapproval, adolescents tendto interpret the parenting as intrusive and their delinquent behav-iors increase, in part because they feel overcontrolled (Kakihara,Tilton-Weaver, Kerr, & Stattin, 2010). Adolescents can also feelthat their parents make too many rules and feel overly controlled,increasing their orientation toward problematic peers (Goldstein,Davis-Kean, & Eccles, 2005). This evidence suggests that someadolescents might be experiencing psychological reactance(Brehm, 1966), strong negative feelings evoked by having one’schoice threatened. As reactance leads to valuing the threatenedchoice even more, parents’ attempts to limit contact mightstrengthen the selection and influence of delinquent peers.

In short, there are two possible but competing hypotheses: (a)parental monitoring of adolescents and communicating disap-proval buffer against their selecting and being influenced by de-linquent peers and (b) parental monitoring of adolescents andcommunicating disapproval exacerbate the selection and influenceof delinquent peers. Whether monitoring and communicating dis-approval buffer or exacerbate the selection and influence of delin-quent peers may depend on whether adolescents feel overly con-trolled. If adolescents feel overly controlled, it is reasonable tothink that these parenting practices exacerbate the selection orinfluence of delinquent peers, whereas buffering effects of moni-toring and peer management might be expected when adolescentsfeel less controlled. Thus, adolescents’ feelings of being controlledby parents may further moderate the effectiveness of monitoringand peer management. In addition, effectiveness may differ acrossadolescence.

This Study

To determine which of these hypothesized relations were sup-ported, we investigated whether parental monitoring or peer man-agement moderated the likelihood of adolescents’ selecting delin-quent peers as friends or adopting their friends’ delinquency.Further, we examined whether the relative importance of thesemechanisms differed across adolescence. We used a cross-sequentialdesign that includes three annual measurements of sociometric andbehavioral data collected from three cohorts of students (early,middle, and late adolescents) all attending public schools in asingle community. Sociometric nominations were not restricted tosame-age friends, so adolescents’ peer networks consisted ofsame-age, older, and younger peer affiliates. Sociometric nomina-tions were also not restricted to peers attending the same classroomor school, but included peers that adolescents spent time with inand outside school. The use of less restrictive sociometric proce-dures is an important advance over previous studies, because thepeers who may be most influential are those found in leisurecontexts (Persson, Kerr, & Stattin, 2007). Thus, their inclusion inthe networks is vital for obtaining more realistic estimates ofdelinquency-based selection and influence. To ascertain the rela-tive importance of selection and influence in each cohort and totest the moderation hypotheses, we used longitudinal social net-work analyses capable of simultaneously estimating the effects ofselection and socialization while accounting for known statisticaland structural interdependencies in dyadic and group-level data(Snijders, van de Bunt, & Steglich, 2010).

Three questions were addressed. To set the stage for questionsabout peer management, we initially asked if the selection orinfluence of delinquent peers differs across early, middle, and lateadolescent peer networks. It was important to establish whetherpeer selection or peer influence differed in strength, as this mightplay a role in the effectiveness of monitoring and peer manage-ment. On the basis of recent work (Burk et al., 2012), we predictedselection based on delinquency would be strongest in early andmiddle adolescence and that the influence of delinquent peerswould not differ across adolescence. Our second and third ques-tions dealt with moderation: Does peer management affect adoles-cents’ selection of delinquent peers or the influence of delinquentpeers in any of the three cohorts? And does this moderation by

3PEER MANAGEMENT AND FRIENDS’ DELINQUENT BEHAVIOR

peer management depend on whether adolescents feel overly con-trolled by their parents?

Method

Participants

The sample consisted of 1,730 adolescents (922 boys and 808girls) ranging in age from 9 to 18 years old. They were drawn froma cohort-sequential study of all students attending public schools ina small city in Sweden (see Kerr, Stattin, & Kiesner, 2007) andwere assessed annually for 3 years. Inclusion in the sample wasbased on the following criteria: (a) being targeted when in fourth,seventh, and 10th grades at Time 1 (T1), (b) being a friend oraffiliate of a target participant, and (c) providing information for atleast two of the three waves of data collection. Thus, the targetsample was composed of 950 adolescents, including early adoles-cents initially attending fourth grade (n � 314, ages 9–11 years,M � 10.1 years); middle adolescents attending seventh grade (n �335, ages 12–14 years, M � 13.1 years), and late adolescentsattending 10th grade (n � 301, ages 15–18 years, M � 16.2 years).An additional 780 adolescents, nominated as friends and affiliates,brought the analytic sample total to 1,730 adolescents. Roughly90% of all participants were born in Sweden and had at least oneparent born in Sweden. At the first wave, approximately 80% ofadolescents in each cohort lived in households with both biologicalparents, 15% lived with one biological parent and one step-parent(or significant other), and 5% lived in single-parent households.

Measures

Peer nominations. Each year all participants completed so-ciometric items that asked them to identify up to three mostimportant peers (defined as “someone you talk with, hang out with,and do things with”), as well as up to 10 peers with whom theyspent time in school and up to 10 peers with whom they spent timeout of school. Participants could nominate any peer; the onlyrestriction was the nominee could not be an adult. All peer nom-inations (except the nominations of romantic partners and siblings)were used to delineate peer networks at each measurement for eachcohort. So, peer networks of the early, middle, and late adolescentcohorts included same-age peers, as well as older and younger peeraffiliates.

Adolescents’ delinquency. Adolescents self-reported on theirdelinquent behaviors, including theft, alcohol use, fighting, andskipping school (Magnusson, Dunér, & Zetterblom, 1975; updatedin Kerr & Stattin, 2003). Responses were recorded on a scale of1–3 for the fifth through sixth graders (1 � no, it has not hap-pened, 2 � one time, 3 � several times) and on a scale of 1–5 forseventh through 12th graders (1 � no, it has not happened, 2 �one time, 3 � two or three times, 4 � between four and 10 times,5 � more than 10 times). To equate the scales, we truncated theitems for older adolescents, recoding values equal to 3 or above to3. Nine items were used to calculate a mean level of delinquency,where an average of 3 meant the adolescent had engaged in allbehaviors several times. Cronbach’s alphas for delinquency acrossthe three waves were (respectively) .74, .72, and .72. To use thesescores in the network analysis, we had to recode the scores into anordinal format. The following criteria were used to create the

categories of the delinquency scores: 1 � 0; 1.001–1.25 � 1;1.2501–1.50 � 2; 1.5001–1.75 � 3; 1.7501–2.00 � 4; and2.001–3 � 5.

Adolescents’ reports on parents’ peer management.Solicitation, monitoring rules, and communicating disapprovalwere measured using reports from adolescents. The items used area subset of the items used by Stattin and Kerr (2000). We elimi-nated one item from each of the scales because the wording andcontent differed for the younger cohorts. We also eliminated anadditional item from the solicitation scale because our analysis andothers (Hawk, Hale, Raajmakers, & Meeus, 2008) suggested thatthe item referring to monitoring through other adults (throughtalking to parents of friends) does not operate well with othersolicitation items. Thus, three items were used to measure solici-tation: “How often do your parents talk to your friends when theycome to your house (ask what they do, how they think and feelabout different things)?”; “How often do your parents ask you totell them about things that have happened during a regular day atschool?”; and “Do your parents usually ask you to tell them whathas happened during your free time? (whom you saw in town, freetime activities, and so forth)?” Responses were given on Likert-like scales ranging from 1 (almost never) to 5 (very often). Esti-mates of reliability suggested that the solicitation scale is margin-ally acceptable (Cronbach’s �s � .64, .64, and .61 for the threewaves). Due to the importance of the construct, we retained thescales. Four items were used to measure monitoring rules: “Do youhave to tell your parents where you are at night, whom you arewith, and what you do together?” “If you go out on a Saturdaynight, do you have to inform your parents in advance about whomyou will be with and what you will be doing?”; “If you have beenout very late one night, do your parents require that you explainwhat you did and whom you were with?”; and “Do you need tohave your parents’ permission to stay out late on a weekdayevening?” The response format for these items ranged from 1 (no,never) to 5 (yes, always). Cronbach’s alphas were .81 across allthree waves. Across the three waves, correlations between thereduced and the original scales (all five items) ranged from .90 to.91 for solicitation and were all .99 for monitoring rules, suggest-ing the reduced and original scales were comparable.

For communicating disapproval, we used four items created forthis study: “If your parents don’t like your friends, they will tellyou”; “Your parents tell you who they think you should have asfriends”; “Your parents tell you if there are some friends they don’tthink you should be with”; and “If your parents don’t like whatyour friends are doing, they will tell you.” The response format forthese items was a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (don’t agree at all)to 4 (agree totally). Cronbach’s alphas for the three waves were.78, .77, and .72. Confirmatory factor analyses were conductedseparately for each age group, with all three waves included in thesame model. The model fit statistics supported using the four itemsas a single measure and provided evidence of congeneric equiva-lence across time and networks, �2(39) � 76.37, p � .001,comparative fit index (CFI) � .98; root mean square error ofapproximation (RMSEA) � .04, standardized root mean squareresidual (SRMR) � .03 for the fourth grade network; �2(39) �105.17, p � .001, CFI � .96; RMSEA � .05, SRMR � .03 for theseventh grade network; and �2(39) � 148.53, p � .001, CFI � .90;RMSEA � .07, SRMR � .05 for the 10th grade network, with allloadings less than or equal to .49.

4 TILTON-WEAVER, BURK, KERR, AND STATTIN

All three scales were significantly and positively correlated:higher levels on one type of peer management were associatedwith higher levels of the other types. Over the three waves,correlations between the same parenting scales ranged from .36 to.50 for solicitation, from .51 to .61 for monitoring rules, and from.35 to .44 for communicating disapproval. Correlations betweendifferent parenting measures ranged from .12, p � .01 (solicitationT1 and communicating disapproval T2) to .36 (solicitation T1 tomonitoring rules T1). These correlations suggest that when parentsuse one type of parenting behavior, they also use the others, andthese results are consistent with the results of others studies, wheresimilar scales were used (e.g., Mounts, 2001; Tilton-Weaver &Galambos, 2003).

Adolescents’ feelings of being overcontrolled. Feeling over-controlled by parents was the mean of five items (Kerr & Stattin,2000). Each item (e.g., “Does it feel like your parents controleverything in your life?”) was rated on a 5-point scale (1 � yes,always; 5 � no, never). Cronbach’s alphas at Waves 1, 2, and 3(respectively) were .71, .77, and .77.

Procedure

Each year, trained research assistants recruited students fromclassrooms during regular school hours. Students were informedthat participation was voluntary and were assured that their an-swers would be kept confidential. Parents were informed about thestudy in community and school meetings and through the mail andcould end their child’s participation by returning a postage-paidcard. The regional ethics review board approved the study.

All youth attending classrooms in Grades 4, 7, and 10 wereinitially targeted for this investigation. Of these students, 98% offourth graders, 92% of seventh graders, and 82% of 10th graderscompleted surveys during at least two of the three measurements,a precondition for inclusion in the study. All older and youngerpeer affiliates nominated by these targeted adolescents who par-ticipated in at least two of the three measurements were alsoincluded in this study. Specifically, the early adolescent networkconsisted of 314 targeted fourth graders (49%), 220 older peers(34%), and 111 younger peers (17%). The middle adolescentnetwork consisted of 335 targeted seventh graders (48%), 176older peers (25%), and 188 younger peers (27%). The late adoles-cent network consisted of 306 targeted 10th graders (59%), 77older peers (15%), and 132 younger peers (26%). So, each networkconsisted of all relationships between same-age targets, as well asall relationships between targeted adolescents and their older andyounger peer affiliates. Using logistic regression analyses, wetested differences between participants in the network samples andthose who did not meet the selection criterion (i.e., were not one ofthe targeted adolescents in fourth, seventh, or 10th grade at T1;were not nominated by a target adolescent as an affiliate; or did notprovide data for two of the three waves). These analyses did notreveal significant differences between study participants and thosewho did not meet the selection criterion on any demographiccharacteristics or behavioral measures used in the study.

Statistical Analyses

Structural features of the peer networks, individual attributes,and delinquent behaviors of the network participants for each age

cohort are initially described. The primary analyses consisted ofactor-based models of network-behavioral dynamics, which wereimplemented with the RSiena software program (Ripley, Snijders,& Preciado, 2013). These models include parameters describingchanges in friendship ties (network dynamics) and parametersdescribing changes in individual delinquent behaviors (behavioraldynamics). The total amount of change in peer networks andindividual delinquent behaviors observed between measurementsis modeled with a continuous-time Markov chain Monte Carloapproach, which models the most probabilistic sequence of indi-vidual events explaining the total amount of observed changes(Snijders, 2005; Snijders et al., 2010). In the present study, threeannual observations were collected, so the iterations were based ontwo periods of observed change (i.e., from T1 to T2 and from T2to T3). These models simultaneously estimate parameter values forchanges in both categorical outcomes (friendship and delin-quency), with friendship dynamics allowed to depend on behaviorsand changes in behaviors and with behavioral dynamics allowed todepend on peer relationships and changes in those relationships.

To aid readers unfamiliar with Siena software, we includeddescriptions of all parameters used in this investigation in Table 1.When looking at this table, readers may note that we tested threetypes of network effects associated with covariates: alter, ego, andsame or similar effects. The term alter refers to the person receiv-ing a nomination (incoming tie), whereas the term ego refers to thesender (outgoing ties). Hence, these effects are linked to nomina-tions received (covariate alter), nominations made (covariate ego),and same or similar effects that are joint functions of alters(receivers) and egos (senders). For example, estimates for genderego, gender alter, and gender same indicate the tendency for onegender to nominate more (or fewer) friends than the other gender,the tendency for one gender to receive more (fewer) nominationsthan the other gender, and the tendency to nominate same-gender(or opposite-gender) peers, respectively. It is important to note thathomophilic selection on the basis of delinquency (delinquencysimilar) is a joint function of the delinquency of the nominator(delinquency ego) and the delinquency of the nominee (delin-quency alter). Readers looking at Table 1 will also note that thereare estimates of behavioral functions linked to covariates. In thisstudy, the outcome was delinquency. Hence, the estimates of theseeffects are the predictions of changes in delinquency (e.g., delin-quency effect from gender refers to changes in delinquency pre-dicted by adolescents’ gender).

We performed three models for each age cohort. In each, net-work dynamics were estimated with parameters that representedthe effect of peer selection based on delinquent behavior (i.e.,delinquency similar or changes in peer affiliations based on pre-existing behavioral similarity). These selection effects were ad-justed for several parameters that account for dyadic and triadicinterdependencies in network structure (e.g., reciprocity, transitivetriplets, and three cycles); contextual constraints due to school andclassroom membership; homophilic selection based on gender andage; and differences in the number of alter (incoming) and ego(outgoing) nominations as a function of age, gender, and delin-quency. In addition, differences in the number of alter (incoming)and ego (outgoing) ties between targets and nontargets were alsoincluded as control measures due to the fact that the peer networksrepresented all peer relationships for the targeted adolescents (i.e.,those initially in fourth, seventh, or 10th grade) but only a portion

5PEER MANAGEMENT AND FRIENDS’ DELINQUENT BEHAVIOR

of the relationships of nontargets (i.e., their younger and olderpeers, some of whom may have nominated targets). Behavioraldynamics were estimated with parameters representing the effectof peer influence (i.e., delinquency average alter or friends’ delin-quent behaviors predicting changes in adolescent delinquency),adjusted for individual behavioral trajectories (i.e., linear andquadratic tendencies), and differences on delinquency as a functionof gender, age, and parents’ peer management. Readers interestedin more detailed descriptions of SIENA and statistical formula-tions of parameters are referred to the work of Snijders andcolleagues (Snijders, Steglich, Schweinberger, & Huisman, 2007;Snijders et al., 2010) and Steglich, Snijders, and Pearson (2010).So, the first set of models was used to examine the relativeimportance of selection and influence during early, middle, andlate adolescence, using z tests to detect differences in the magni-tudes of effects between age groups (Ripley et al., 2013).

In addition to these parameters, the second set of models alsoincluded the main effects of peer management and interactionswith peer selection and socialization. Six interactions weretested in each cohort. Each of the interactions combines theparenting of the nominator (solicitation ego, monitoring rulesego, or communicate disapproval ego) with either the selectionof delinquent peers (delinquency alter) or the influence ofdelinquent nominees (delinquency average alter). Note that wecreated the interaction by combining parenting with the selec-tion of a delinquent peer (delinquency alter) rather than with

homophilic selection based on delinquency (i.e., delinquencysimilar). Hence, three interactions—solicitation ego by delin-quency alter, monitoring rules ego by delinquency alter, andcommunicating disapproval ego by delinquency alter—testedthe question: Are adolescents whose parents solicit information,set monitoring rules, or communicate disapproval more likelyto select delinquent peers than adolescents whose parents solicitless information, set fewer rules, or communicate less disap-proval? The other three interactions—solicitation ego by delin-quency average alter, monitoring rules ego by delinquencyaverage alter, and communicating disapproval ego by delin-quency average alter—tested if adolescents whose parents so-licit information, set monitoring rules, or communicate disap-proval are more likely to adopt the delinquent behaviors ofpeers than adolescents whose parents monitor or manage less.All six interactions were tested simultaneously. To summarize,although these models control for homophilic selection andinfluence, the interactions test whether any selection (delin-quency alter) or influence (delinquency average alter) of delin-quent peers is dependent on parents’ peer management.

The final set of models examined whether the two-way interac-tions were further moderated by adolescent feelings of beingovercontrolled. That is, adolescents’ feelings of being overcon-trolled were included in these final analyses, as well as the two-and three-way interactions.

Table 1Labels and Descriptions of Parameters Estimated in the Stochastic Actor-Oriented Models

Estimate label Interpretation

Network effectsDensity Tendency for arbitrary (�) or selective (�) tiesReciprocity Tendency for ties to be reciprocatedTransitive triplets Tendency for adolescents’ friends to become friendsThree cycles Tendency for triadic relations to demonstrate local hierarchy

(�)Covariate altera Incoming ties on covariate (� � Nominees report high values

on covariate)Covariate egob Outgoing ties on covariate (� � Nominators report high values

on covariate)Covariate same/similara Actors nominate others with same/similar value on covariate

(� � Homophilic selection)Two-way interactions: Covariate Ego � Delinquency Alter

(selection)cTests whether nomination (selection) of delinquent peers differs

as a function of nominator’s behaviorThree-way interactions: Feeling Overcontrolled � Covariate �

Delinquency Alter (selection)cTest moderation of previous interactions by adolescents’ feeling

overcontrolledBehavioral effects

Delinquency linear shape Tendency to engage in delinquency (0 � Midpoint in the scaleor moderately low)

Delinquency quadratic shape Tendency for changes in delinquency to depend on initial levelsDelinquency effect from covariated Covariate associated with changes in delinquency (� � Higher

values on covariate positively related to more delinquency)Delinquency average alter (influence) Tendency of adolescents to become more delinquent when

friends report higher levels of delinquencyTwo-way interactions: Covariate Ego � Delinquency Average Alter

(influence)cTest whether delinquent peer influence differs as a function of

covariate valuesThree-way interactions: Feeling Overcontrolled � Covariate Ego �

Delinquency Average Alter (influence)cTest moderation of previous interactions by adolescents’ feeling

overcontrolled

a Covariates included target status, class, school, age, gender, and delinquency; these effects include delinquency similar, which estimates homophilicselection. b Covariates included target status, age, gender, delinquency, solicitation, monitoring rules, and communicating disapproval. c Includedinteractions with solicitation, monitoring rules, and communicating disapproval. d Covariates included age, gender, solicitation, monitoring rules,and communicating disapproval.

6 TILTON-WEAVER, BURK, KERR, AND STATTIN

Results

Descriptive Analyses

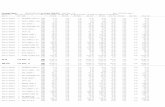

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics of the three peer networks,with network sample sizes provided first. The following rowsshow that the average number of peer associates (average numberof ties) ranged from three to more than four across the threenetworks. Middle adolescents nominated an average of more thanfour friends; early and late adolescents averaged slightly fewerthan four friendship nominations. The number and proportion ofdyadic and triadic ties are also reported. Approximately 60% of allnominations in the early and middle adolescent networks werereciprocated, with slightly fewer (about 50%) reciprocated in thelate adolescent network. About 35% of nominations formed triadicrelations (i.e., network relations involving three adolescents) dem-onstrating transitive network closure (i.e., friends of friends be-coming friends) in each network at each measurement. So, thestructural features of the early, middle, and late adolescent net-works were more similar than different. Jaccard indices indicatedthat the peer networks did not change too rapidly or abruptly (allvalues � .20). Descriptives for behaviors are presented in thelower half of Table 2 (means and standard deviations for thecontinuous variables, frequencies for delinquency). These showthat the parenting variables and delinquency have adequate vari-ability and that the means of parenting and feeling overcontrolledvariables were close to the middle ranges of their respective scales.The distributions also indicate that delinquent behaviors weremore prevalent in middle adolescence than in early or late adoles-cence. Moran’s I autocorrelation statistic (provided in the last line;Moran, 1950; Steglich et al., 2010), describing the degree ofsimilarity between friends’ delinquent behaviors, increased lin-early in the early adolescent networks and exhibited somewhatcurvilinear patterns in the middle adolescent and late adolescentnetworks. These statistics indicate a moderate degree of similaritybetween friends, with the strongest linear increase occurring in theearly adolescent network and then dissipating in late adolescence.

Peer Network and Behavioral Dynamics

In each of the actor-based models, we estimated selection andinfluence, adjusting for several predictors of network and behav-ioral dynamics. Unstandardized estimates, standard errors, and ttest values from the final models are reported in Tables 3 and 4,including estimates predicting changes in peer relationships (net-work dynamics) and estimates predicting changes in adolescentdelinquency (behavioral dynamics).

Regarding effects of network structure (see Table 3), friendshipswere selective rather than random, as indicated by significantnegative values for network density. Adolescents in all networkstended to reciprocate nominations (reciprocity) and befriend thefriends of their friends (transitive triplets and three cycles). Asindicated by the significant positive estimates for the covariatesimilar and same estimates, adolescents tended to select peerssimilar in age, in the same class, of the same gender, and with thesame target status (except in the early adolescent network). In theearly and middle adolescent networks, adolescents tended to selectindividuals in the same school, whereas in the late adolescentnetwork, adolescents choose peers from outside the same school(as indicated by a negative school same estimate).

Adolescents who were more active in the networks (i.e., nom-inated more peers, as indicated by the covariate ego estimates)tended to be younger adolescents (except in the late adolescentnetwork) and female (except in the early adolescent network). Inthe early adolescent network, adolescents who were more activealso tended to be more delinquent and had parents who solicitedinformation more than those who were less active. In the middleadolescent network, adolescents whose parents who communi-cated more disapproval were more active than those whose parentscommunicated less disapproval. Adolescents who were more pop-ular (i.e., were nominated more by others, indicated by a signifi-cant covariate alter estimate) tended to be nontargets, male (in themiddle and late adolescent networks), and older adolescents (onlyin the early adolescent network). In the middle adolescent network,delinquent adolescents received more nominations than less delin-quent adolescents. These results suggest these structural, contex-tual, and individual characteristics are important predictors offriendship dynamics and should be accounted for when examininghomophilic selection based on delinquency.

Regarding behavioral effects (see Table 4), linear shape effectswere significant in all but the late adolescent network, indicatingthat most of the adolescents reported having engaged, on average,in less than one delinquent act in the year proceeding data collec-tion. For the early and late adolescent networks, there were alsosignificant quadratic shapes. Combined with a negative linearshape in the early adolescent network, the positive quadratic shapeindicates that those who initially reported lower levels of delin-quency were more likely to increase in delinquent behaviors (i.e.,a positive feedback for the lowest initial levels). In the late ado-lescent network, the significant negative quadratic suggests a neg-ative feedback or self-correcting tendency, indicating that thosewith the highest levels of delinquency tended to decrease delin-quent behaviors. In the younger cohort only, older adolescentswere more likely than younger adolescents to increase in delin-quent behavior (indicated by the significant effect from age).Adolescents whose parents had monitoring rules were less likely toincrease in delinquency (significant effect from monitoring rules inthe early and middle adolescent networks). Controlling these ef-fects increased the validity of attributing changes in delinquency topeer influence.

Does Delinquency-Based Selection or Influence DifferAcross Early, Middle, or Late Adolescent Networks?

Our first question was whether the selection and influence ofdelinquent peers varied across the three cohorts. We answered thisby examining the parameter estimates for homophilic selectionbased on delinquent behaviors (delinquency similar, Table 3) anddelinquency-based influence (delinquency average alter, Table 4).In all three networks, adolescents selected friends with similarlevels of delinquent behaviors. Z tests, however, did not revealsignificant differences between the early and middle adolescent net-works (z � 1.51, p � .13), the early and late adolescent networks(z � 0.93, p � .35), or middle and late adolescent networks(z � –0.11, p � .91). Adolescents also increased their delinquentbehaviors when their friends reported relatively high levels ofdelinquency (delinquency average alter). Influence effects did notdiffer significantly between early and middle adolescent networks(z � 1.67, p � .09), early and late adolescent networks (z � 0.84,

7PEER MANAGEMENT AND FRIENDS’ DELINQUENT BEHAVIOR

Tab

le2

Net

wor

kan

dB

ehav

iora

lD

escr

ipti

veSt

atis

tics

ofE

arly

,M

iddl

e,an

dL

ate

Ado

lesc

ent

Pee

rN

etw

orks

Ear

ly(4

thgr

ade)

Mid

dle

(7th

grad

e)L

ate

(10t

hgr

ade)

Stat

istic

sW

1W

2W

3W

1W

2W

3W

1W

2W

3

Net

wor

kde

scri

ptiv

esPa

rtic

ipan

ts48

762

460

464

865

764

744

148

040

3T

otal

no.

oftie

s1,

281

1,93

71,

975

2,20

72,

661

2,64

81,

150

1,37

91,

203

Ave

rage

no.

oftie

s3.

513.

223.

513.

674.

314.

423.

103.

103.

89N

o.of

reci

proc

ated

dyad

s39

961

459

466

181

477

929

737

832

8Pr

opor

tion

ofre

cipr

ocat

eddy

ads

.62

.63

.60

.60

.61

.59

.52

.55

.55

No.

oftr

ansi

tive

tria

ds1,

527

2,76

62,

788

3,51

25,

289

5,41

11,

152

1,58

92,

010

Prop

ortio

nof

tran

sitiv

etr

iads

.39

.37

.35

.37

.37

.38

.33

.33

.41

Jacc

ard

inde

xa.3

3.3

1.3

2.3

5.2

9.3

7C

ovar

iate

mea

ns(S

D)

Solic

itatio

n2.

41(0

.86)

2.43

(0.8

6)2.

46(0

.85)

2.44

(0.8

4)2.

49(0

.84)

2.56

(0.8

4)2.

38(0

.85)

2.33

(0.8

6)2.

31(0

.77)

Mon

itori

ngru

les

2.45

(0.8

4)2.

49(0

.83)

2.53

(0.8

4)2.

51(0

.79)

2.44

(0.7

6)2.

33(0

.77)

2.05

(0.7

3)1.

93(0

.73)

1.92

(0.7

7)C

omm

unic

ate

disa

ppro

val

2.69

(0.7

6)2.

69(0

.75)

2.65

(0.7

2)3.

77(0

.73)

2.68

(0.7

2)2.

62(0

.66)

2.58

(0.7

4)2.

54(0

.73)

2.53

(0.6

5)Fe

elin

gov

erco

ntro

lled

2.41

(0.8

4)2.

41(0

.86)

2.30

(0.8

9)2.

54(0

.84)

2.63

(0.9

2)2.

48(0

.93)

2.40

(0.8

3)2.

26(0

.82)

2.16

(0.9

2)D

elin

quen

tbe

havi

orfr

eque

ncie

sN

one

(0)

372

415

357

357

259

194

111

6649

Ver

ylo

w(1

)10

012

514

015

016

816

214

813

297

Low

(2)

2659

5680

9613

910

713

612

9M

oder

ate

low

(3)

921

2534

6864

2765

57M

oder

ate

high

(4)

510

1827

4439

2541

19H

igh

(5)

46

1522

2632

2424

19M

issi

ng13

010

3529

3869

7351

145

Mor

an’s

I.1

2.2

6.4

3.2

8.3

9.2

9.2

5.2

8.2

0

Not

e.A

dditi

onal

deta

ils(d

escr

iptiv

esbr

oken

dow

nby

targ

et,

olde

ran

dyo

unge

rpe

ers)

can

beob

tain

edby

cont

actin

gth

efi

rst

auth

or.

W�

Wav

e.a

Est

imat

esch

ange

duri

ngth

epe

riod

sbe

twee

nw

aves

.

8 TILTON-WEAVER, BURK, KERR, AND STATTIN

p � .40), or middle and late adolescent networks (z � –0.93, p �.35). These results suggest that selection and influence of delin-quent peers are present and do not significantly differ in relativestrength across adolescence.

Does Peer Management Affect the Selection orInfluence of Delinquent Peers?

To answer the question of whether peer management moderatedthe selection or influence of delinquent peers, we examined sixinteractions in each cohort. Three were interactions of peer manage-ment with selection of delinquent peers (i.e., Solicitation Ego �Delinquency Alter, Monitoring Rules Ego � Delinquency Alter, andCommunicating Disapproval Ego � Delinquency Alter, where egorefers to the person selecting others and alter refers to the peer beingselected). These interactions test the question, Do adolescents (egos)whose parents monitor or communicate disapproval tend to selectmore delinquent friends (alters) than adolescents whose parents mon-itor less or communicate less disapproval? The other three interactionswere combinations of peer management and the influence of delin-quent peers (i.e., Solicitation Ego � Delinquency Average Alter,Monitoring Rules Ego � Delinquency Average Alter, and Commu-nicating Disapproval Ego � Delinquency Average Alter). Theseinteractions tested the question, Are adolescents (egos) whose parents

monitor or communicate disapproval more likely to adopt the delin-quent behaviors of their friends (alters) than adolescents whose par-ents monitor less or communicate less disapproval?

Concerning the interactions involving selection of delinquentpeers (in Table 3), two of the nine interactions emerged as statis-tically significant. A significant Communicating DisapprovalEgo � Delinquency Alter interaction in the middle adolescentnetwork indicated that adolescents differentially selected delin-quent peers as a function of their parents’ communicating disap-proval. We probed the interactions by plotting the simple slopesat –1, 0, and 1 standard deviations of the peer managementbehaviors. In Figure 1 the lines, depicting the log odds of selectinga delinquent peer, show that middle adolescents tended to selectmore delinquent peers, regardless of their own delinquency levels(i.e., the slopes are positive at all three levels communicatingdisapproval). This tendency was progressively accentuated as lev-els of communicating disapproval increased, so the more parentscommunicated disapproval of adolescents’ friends, the greater thetendency for middle adolescents to select delinquent friends. Plotsfor the second significant interaction, Monitoring Rules Ego �Delinquency Alter in the late adolescent network, are shown inFigure 2. The dotted line shows that at low levels of monitoringrules, adolescents were more likely to select delinquent peers. This

Table 3Unstandardized Parameter Estimates of Structural Dynamics in Early, Middle, and Late Adolescent Peer Networks

Variable

Early (n � 646) Middle (n � 699) Late (n � 515)

Est SE t p Est SE t p Est SE t p

Structural effectsDensity �4.67 0.06 �77.00 ��� �4.15 0.04 �99.21 ��� �4.02 0.08 �50.43 ���

Reciprocity 3.03 0.06 49.60 ��� 2.70 0.05 54.82 ��� 2.84 0.08 37.31 ���

Transitive triplets 0.75 0.03 22.38 ��� 0.62 0.02 30.65 ��� 0.98 0.04 23.07 ���

Three cycles �0.91 0.06 �16.44 ��� �0.10 0.04 �18.15 ��� �1.07 0.08 �12.95 ���

Target alter (target � 1) �0.21 0.04 �5.11 ��� �0.22 0.03 �6.96 ��� �0.23 0.05 �4.62 ���

Target ego 0.10 0.05 1.95 �0.04 0.03 �1.08 �0.03 0.06 �0.50Target same 0.08 0.04 1.91 0.08 0.03 2.77 �� 0.23 0.05 4.92 ���

School same 0.63 0.03 19.00 ��� 0.42 0.03 14.54 ��� �0.45 0.05 �8.31 ���

Classroom same 0.25 0.05 5.50 ��� 0.61 0.04 16.95 ��� 0.79 0.06 13.96 ���

Characteristics of ego and alterAge alter 0.18 0.03 6.88 ��� 0.00 0.02 0.11 0.03 0.03 0.94Age ego �0.16 0.03 �4.72 ��� �0.06 0.02 �3.21 �� �0.02 0.04 �0.51Age similar 2.42 0.22 11.15 ��� 1.65 0.16 10.53 ��� 2.53 0.31 8.17 ���

Gender alter (female � 1) �0.13 0.05 �2.54 �0.10 0.04 �2.71 �� �0.24 0.06 �3.97 ���

Gender ego 0.17 0.06 3.02 0.22 0.04 5.31 ��� 0.20 0.07 2.92 ��

Gender same 1.02 0.05 20.91 ��� 0.65 0.03 19.43 ��� 0.85 0.07 13.52 ���

Delinquency alter 0.01 0.03 0.43 0.08 0.02 4.36 ��� 0.00 0.03 0.11Delinquency ego 0.19 0.04 5.40 ��� 0.01 0.02 0.79 �0.01 0.03 �0.40Delinquency similar (selection) 0.94 0.20 4.61 ��� 0.59 0.12 5.04 ��� 0.62 0.28 2.21 �

Solicitation ego 0.05 0.02 2.47 �� 0.03 0.02 1.28 �0.02 0.03 �0.80Monitoring rules ego �0.03 0.03 �1.01 �0.02 0.02 �0.94 0.04 0.03 1.13Communicating disapproval ego �0.01 0.02 �0.48 0.05 0.02 2.45 �� �0.01 0.04 �0.28

Two-way interactionsSolicitation Ego � Delinquency Alter (selection) 0.01 0.03 0.25 0.00 0.02 0.31 0.03 0.03 1.23Monitoring Rules Ego � Delinquency Alter (selection) �0.01 0.03 �0.22 �0.02 0.02 �1.30 �0.07 0.03 �2.15 �

Communicating Disapproval � Delinquency Alter (selection) 0.06 0.03 1.93 0.05 0.02 2.52 �� �0.02 0.04 �0.44Three-way interactions: Overcontrolled Ego �

Solicitation Ego � Delinquency Alter (selection) �0.03 0.31 �0.10 0.15 0.16 0.88 0.03 0.13 0.23Monitoring Rules Ego � Delinquency Alter (selection) 0.12 0.04 3.26 �� �0.01 0.12 �0.04 0.07 0.10 0.70Communicate Disapproval Ego � Delinquency Alter (selection) 0.01 0.02 0.61 �0.02 0.01 �1.29 �0.05 0.03 �1.79

Note. Network rate function parameters are included in all models but omitted from the table. Est � estimate; SE � standard error.� p � .05. �� p � .01. ��� p � .001.

9PEER MANAGEMENT AND FRIENDS’ DELINQUENT BEHAVIOR

tendency was reversed at high levels of monitoring rules, suggest-ing that the higher the monitoring rules, the less likely adolescentswere to select delinquent peers. These results suggest that howmonitoring and peer management change selection depends on theparenting behavior and the timing.

For the interactions of parenting with peer influence (see Table4), one interaction was significant: communicating disapprovalaltered the influence of delinquent peers (Communicating Disap-proval � Delinquency Average Alter) in the late adolescent net-work. Figure 3 shows the tendency to be influenced by delinquentpeers, using values based on ego–alter influence tables. The gray

lines, depicting the influence of peers’ delinquency at low levels ofcommunicating disapproval, have the typical pattern of peer influ-ence: adolescents who were more delinquent tended to be influ-enced by delinquent peers, and adolescents who were not delin-quent tended to be influenced by less delinquent peers. In otherwords, those higher in delinquency tended to become more delin-quent. At high levels of communicating disapproval (indicated bythe black lines), the pattern was reversed: nondelinquents weremost influenced by peers exhibiting more delinquency, and ado-lescents with higher levels of delinquency were most influenced bythose lowest in delinquency. Thus, communicating disapproval

Table 4Unstandardized Parameter Estimates of Delinquent Behavioral Dynamics for Early, Middle, and Late Adolescents

Variable

Early (n � 646) Middle (n � 699) Late (n � 515)

Est SE t p Est SE t p Est SE t p

Behavioral effectsDelinquency linear shape �0.82 0.06 �14.33 ��� �0.18 0.04 �4.86 ��� 0.06 0.04 1.34Delinquency quadratic shape 0.13 0.03 3.95 ��� 0.02 0.02 1.07 �0.18 0.04 �5.08 ���

Delinquency effect from age 0.13 0.04 3.04 �� �0.03 0.03 �1.19 0.08 0.05 1.82Delinquency effect from gender �0.12 0.08 �1.47 �0.04 0.06 �0.70 �0.09 0.07 �1.22Delinquency average alter (influence) 0.54 0.18 3.09 �� 0.23 0.07 3.07 �� 0.36 0.13 2.84 ��

Delinquency effect from solicitation �0.04 0.06 �0.65 0.02 0.04 0.42 0.03 0.05 0.64Delinquency effect from monitoring rules �0.17 0.06 �2.76 �� �0.13 0.04 �2.89 �� �0.05 0.15 �0.31Delinquency effect from communicate disapproval 0.07 0.06 1.12 0.09 0.05 1.94 0.04 0.06 0.64

Two-wav interactionsSolicitation Ego � Delinquency Average Alter (influence) �0.14 0.23 �0.60 �0.13 0.10 �1.40 �0.08 0.15 �0.52Monitoring Rules Ego � Delinquency Average Alter (influence) 0.34 0.21 1.57 0.17 0.10 1.81 0.04 0.15 0.26Communicate Disapproval Ego � Delinquency Average Alter

(influence) �0.04 0.21 �0.19 �0.13 0.10 �1.30 �0.39 0.20 �1.98 �

Three-way interactions: Over-Controlled Ego �Solicitation Ego � Delinquency Average Alter (influence) �3.06 2.98 �1.03 �10.34 18.20 �0.57 �2.52 6.27 �0.40Monitoring Rules Ego � Delinquency Average Alter (influence) �0.32 0.29 �1.10 8.92 18.40 0.48 �0.66 2.89 �0.23Communicating Disapproval Ego � Delinquency Average Alter

(influence) �0.22 0.23 �0.94 0.07 0.10 0.64 �0.05 0.17 �0.28

Note. Behavioral rate function parameters are included in all models but omitted from the table. All effects in this table are those associated withdelinquency as the outcome. Est � estimate; SE � standard error.� p � .05. �� p � .01. ��� p � .001.

Figure 1. Selection of delinquent peers as a function of parents’ com-municating disapproval in the middle adolescent network. Dotted line �low level of communicating disapproval; dashed line � mean level; solidline � high level.

Figure 2. Selection of delinquent peers as a function of parents’ moni-toring rules in the late adolescent network. Dotted line � low level ofmonitoring rules; dashed line � mean level; solid line � high level.

10 TILTON-WEAVER, BURK, KERR, AND STATTIN

may protect adolescents who are delinquent, but it has unintendedeffects on those who are not.

Overall, these results provide mixed support for the monitoringidea. No evidence was found that solicitation buffered or exacer-bated the selection of delinquent peers. Monitoring rules wererelated to less selection of delinquent peers but only in the lateadolescent network. In the middle adolescent network, communi-cating disapproval backfired, increasing the tendency to select

delinquent peers. Further, in the late adolescent network, there wasevidence that while communicating disapproval acted to protectagainst the influence of delinquent peers for those higher in de-linquency, it operated to increase the influence of delinquent peersfor those low in delinquency. There are times, then, that monitor-ing rules are protective, but communicating disapproval can acteither way, protecting under some conditions and increasing theselection and influence of delinquent peers under other conditions.

Does Feeling Overcontrolled Modify How Monitoringand Peer Management Are Related to Selection andInfluence Processes?

In an additional set of models, we tested whether the relationsbetween monitoring or communicating disapproval and selectionor influence of delinquent peers were moderated by adolescents’feeling overly controlled by their parents. Specifically, these mod-els included all parameters in the previous models as well as themain effects of feeling overcontrolled, and the two- and three-wayinteractions involving monitoring or peer management and delin-quent peer selection (see Table 3) or influence (see Table 4). Thethree-way interactions were of particular interest, in that theyprovided a comprehensive test of whether peer management mod-erated selection and influence of delinquent peers for adolescentswho were more or less likely to accept peer management. Onethree-way interaction with selection, reported in Table 3, wassignificant: feeling overcontrolled by parents altered the modera-tion of monitoring rules on selecting delinquent peers in the earlyadolescent network. This interaction was probed by plotting valuesof delinquent peer selection at low and high values of feelingovercontrolled and monitoring rules. As can be seen in Figure 4,when adolescents do not feel overcontrolled, the selection ofdelinquent peers is greater when parents have fewer monitoringrules (solid gray line) than when parents have more rules (dottedgray line). By contrast, the pattern is reversed when adolescentsfeel overcontrolled, such that the selection of delinquent peers isgreater when parents have more monitoring rules (solid black line)than when they have fewer rules (dotted black line). This suggeststhat although parents can reduce the selection of delinquent friendsby establishing rules for monitoring adolescents’ leisure time, itwill work only when adolescents do not already feel overly con-trolled. When adolescents feel overly controlled, monitoring rulesaccentuate the selection of delinquent peers.

Discussion

A major idea in the literature on parenting and adolescentdelinquency is that parents should keep a close eye on theiradolescents’ activities and peer associations when they are awayfrom home. If associations with problematic peers begin to de-velop, parents will find out and be able to steer their adolescentsaway from those peers—processes described as monitoring andpeer management. We tested this idea against an alternative sce-nario based on theory and empirical findings about the roles ofparent and peer relationships in adolescent development: Peers areimportant sources of support throughout adolescence, and adoles-cents often believe that parents should not interfere in their friend-ships. Likewise, adolescents who view leisure activities as issuesof personal choice may resist parental attempts to regulate them.

Figure 4. Selection of delinquent peers as a function of adolescents’feeling overcontrolled and parents’ monitoring rules in the early ado-lescent network. Gray dotted line � low level of overcontrol/low levelof monitoring rules; gray solid line � low level of overcontrol/highlevel of monitoring rules; dark dotted line � high level of overcontrol/low level of monitoring rules; dark solid line � high level of overcon-trol/high level of monitoring rules.

Figure 3. Influence of delinquent peers as a function of parents’ com-municating disapproval in the late adolescent network. Gray dotted line �low level of communicating disapproval/no delinquency ego; gray solidline � low level of communicating disapproval/high delinquency ego; darkdotted line � high level of communicating disapproval/no delinquencyego; dark solid line � high level of communicating disapproval/highdelinquency ego.

11PEER MANAGEMENT AND FRIENDS’ DELINQUENT BEHAVIOR

According to this view, monitoring and peer management effortsare unlikely to be effective and might even backfire, increasing thevery sources of influence that parents are trying to impede. Ourstudy provided support for both of these views, suggesting thathow monitoring and peer management are related to peers’ delin-quency is complex and theoretically nuanced.

In all three age groups, we found evidence that similarity indelinquency is a function of both homophilic selection and influ-ence. The relative strength of these processes did not differ acrossthe three networks, so it is clear that concerns about delinquentpeers are valid, even for adolescents in elementary school. Ad-dressing the conditions under which monitoring and peer manage-ment might be effective in reducing these peer processes is apressing issue.

Our results suggest that monitoring and peer management werenot uniformly effective or ineffective. Under some conditions, theparenting behaviors were protective. For late adolescents, selectionof delinquent peers was reduced when parents established highlevels of monitoring rules, and influence was curbed when parentscommunicated disapproval of friends. These results are consistentwith socialization theories, which posit that parental monitoringand peer management can protect against rises in delinquent be-haviors (Fletcher et al., 1995). Under other conditions, our resultssupport theoretical arguments that adolescents view some forms ofmonitoring and peer management as intrusive (e.g., Kakihara et al.,2010; Mounts, 2001; Tilton-Weaver & Galambos, 2003). Amongmiddle adolescents, higher levels of communicating disapprovalincreased the selection of delinquent peers. For late adolescentswho were not already delinquent, communicating disapproval in-creased the influence of delinquent peers. These results are lessconsistent with social learning models and more consistent withtheoretical models suggesting that parents can fail to accommodateto adolescents’ needs for autonomy and personal choice (e.g.,Eccles et al., 1991). The results of this study suggest caution andcall for understanding why the same behaviors are sometimeseffective and sometimes ineffective.

One way of understanding when monitoring and peer manage-ment are effective is to examine when they are used. In our study,age grouping was an important qualifying dimension. Althoughthese differences could represent cohort effects, an equally validinterpretation is that timing matters. Some early adolescents appearto be more reactive to feeling overcontrolled by parents, alteringthe effectiveness of monitoring rules. When parents enforced morerules, the likelihood of selecting delinquent peers decreased for thosewho did not feel overcontrolled by parents but increased for thosewho felt overcontrolled. There are two ways of interpreting thisfinding that bear further study: adolescents who feel overcon-trolled could be experiencing more reactance, or they could be lesswilling to accept parental authority over their friendships andleisure activities than those who feel less controlled by theirparents. As early adolescence is a period in which many adoles-cents reject parental authority over such multifaceted issues(Smetana & Asquith, 1994), feeling overcontrolled could indicaterejection of parental authority.

It is also reasonable to assume that changing views aboutparental authority lie behind the findings for middle adolescents,for whom communicating disapproval progressively increased theselection of delinquent peers. Research suggests that strugglessurrounding autonomy and parental authority may be more pro-

nounced in middle adolescence than earlier or later, as conflictover such issues appears to be greater (Smetana & Asquith, 1994).Given that communicating disapproval, in particular, may beviewed as abrogating personal choice, the fact that its negativeeffect was not limited to those who felt overcontrolled is notsurprising.

The results for the late adolescent network are less straightfor-ward. Monitoring rules, which should be more problematic for lateadolescents than for early or middle adolescents (Smetana &Asquith, 1994), acted in a protective manner, reducing the selec-tion of delinquent peers. One way of understanding these counter-intuitive results is that in late adolescence, levels of delinquencyare already dropping, and adolescents are better at regulatingthemselves. Even though late adolescents feel they should haveauthority over their friendships and leisure activities, they may beable to understand their parents’ concerns. Alternatively, it ispossible that parents shift the manner in which they communicatedisapproval and set rules, negotiating rather than being directive.Such a scenario would be consistent with research suggesting thatthe frequency of parent–adolescent conflict decreases from mid tolate adolescence (Laursen, Coy, & Collins, 1998) and wouldexplain why rules are protective. Another puzzling finding wasthat the effectiveness of communicating disapproval in the lateadolescent network depended on the delinquency of the adoles-cent, exacerbating influence when adolescents were not alreadydelinquent, but curbing it when they were. Again, if adolescentsare becoming better regulated and starting to see good reasons todesist delinquent activities, they may better understand their par-ents’ attempts to intervene with problematic peers. For those whoare not delinquent, such prohibitions may engender reactance.These interpretations, however, are post hoc. Our results, then,await confirmation or elaboration with similar data spanning ad-olescence. Nonetheless, the results suggest a more nuanced under-standing of parental monitoring and peer management.

We assert that this more nuanced view of monitoring and peermanagement was born out of our study’s unique design features.To our knowledge, this is the first study in which monitoring andpeer management have been tested as moderators of the selectionand influence of delinquent peers using adolescents’ own ratingsof their delinquency for peers both inside and outside the school orclassroom. These design features are not trivial. Using adolescentreports of their peers’ behavior and limiting peer nominations tothe school or classroom have both been shown to produced biasedviews of homophily and peer influence, because adolescents seetheir peers as more like them than they actually are (Kandel, 1996)and because older peers outside of the classroom and school areimportant influences for delinquency (Persson et al., 2007). Test-ing whether monitoring or peer management moderated adoles-cents’ tendencies to select or be influenced by their delinquentpeers was made possible by the use of stochastic actor-orientedmodels, the only method currently available for simultaneouslyestimating selection and influence while controlling for effectssuch as the tendency to reciprocate friendships or to select peerssimilar in age. What these network effects show is that the chancesof selecting an individual peer as a friend are not equal for alladolescents, and thus, network and behavioral influences on ado-lescent friendship choices should be controlled when examiningselection and influence. Finally, this study is unique in applyingquestions about monitoring and peer management across adoles-

12 TILTON-WEAVER, BURK, KERR, AND STATTIN

cence. Although theory suggests that effects should differ as afunction of adolescents’ age, research has not dealt with thesedifferences. In several ways, then, this study offers an expandedview of monitoring and peer management in adolescence.

This study has some limitations worth considering. First, ado-lescents reported on the peer management strategies of their par-ents, potentially introducing common method variance. Second,adolescents reported on parents collectively, rather than on moth-ers and fathers separately. Prior research has shown that motherstend to seek more information than fathers, but parents’ reports arealso substantially correlated (Tilton-Weaver & Galambos, 2003).Even so, their impact on adolescents’ peers may differ. Theseissues still need to be addressed. These limitations, however, arerather minor in comparison to the strengths of this study. Theuniqueness of these data provided an opportunity to test questionsabout selection and influence in the most ecologically valid waypossible.

There is still important work to be done. We tested whether peermanagement affected peer processes and whether peer manage-ment was further moderated by adolescents feeling overly con-trolled. Feeling overly controlled may be a proxy for adolescents’authority beliefs, and proxies rarely match the measurement qual-ities of direct assessment. It is possible that by not directly assess-ing authority beliefs, moderation was underestimated. In addition,others have argued that parental warmth may be a condition underwhich adolescents perceive peer management as more acceptable.These and other moderators should be directly tested before clos-ing the chapter on the effectiveness of peer management.

Another direction for future work is to delve deeper into howpeer processes of selection and influence work, going beyondestimating selection and influence to understand more clearly howthey operate. It is possible that adolescents differentially select andare influenced to the same degree across adolescence, but fordifferent reasons. For example, early adolescents might be influ-enced by delinquent peers because of a need to elevate their status(as described by Moffitt, 1993), whereas middle adolescents mightfeel a greater pressure to conform to peers. Understanding themechanisms by which peer selection and influence operate willgive researchers a better idea of the role parenting plays and howparents might intervene.

Our research suggests that alternative strategies for reducing theselection and influence of delinquent peers should be considered.These strategies may involve other ways parents shape friendships,including talking about friendship choices, supporting friendships,and giving advice when requested. Described as guiding, support-ing, and coaching, these practices are part of the peer managementrepertoire (Mounts, 2000; Tilton-Weaver & Galambos, 2003).Although we were unable to test these strategies in this study, theymay be even more effective because they are not particularlyintrusive. Through these practices, parents might be able to steeradolescents toward peers with more desirable characteristics andbehaviors, and through these relationships promote their adoles-cents’ well-being. Coleman (1988) suggested another route, argu-ing that social control is reinforced when parents share informationabout what their children do. According to Coleman, when parentsof friends are networked, the behavior of one parent reinforces thebehavior of the friend’s parent. The possibility of these behaviorsbeing effective awaits further research. Whatever parents do, our

results suggest that they should start early, because selection ofdelinquent peers is already operating in early adolescence.

Parents generally want to steer their adolescents away fromdelinquent peers. This idea is intuitively appealing and logical.However, parents and researchers are cognizant of the importanceof peers and most know adolescents do not welcome parents’criticisms of their friends. Our results revise the question from“What can parents do?” to “How should parents try to regulateadolescents’ peer relationships?” and “When should they changetactics?” Our results suggest that there are times, primarily duringearly and middle adolescence, that parents should tread carefully.Still, comprehensive answers have yet to be discovered, and an-swers will surely differ depending on the problem-behavior historyof the adolescent. For some, though, the answers will not lie inbetter or more effective control but will likely involve findingways to respect and accommodate to adolescents’ changing per-ceptions of authority and autonomy.

References

Agnew, R. (1991). The interactive effects of peer variables on delinquency.Criminology, 29, 47–72. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.1991.tb01058.x

Baerveldt, C., Völker, B., & Van Rossem, R. (2008). Revisiting selectionand influence: An inquiry into the friendship networks of high schoolstudents and their association with delinquency. Canadian Journal ofCriminology and Criminal Justice, 50, 559–587. doi:10.3138/cjccj.50.5.559

Bank, L., Burrastan, B., & Snyder, J. (2004). Sibling conflict and ineffec-tive parenting as predictors of adolescent antisocial behavior and peerdifficulties: Additive and interactional effects. Journal of Research onAdolescence, 14, 99–125. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2004.01401005.x

Berndt, T. J. (1979). Developmental changes in conformity to peers andparents. Developmental Psychology, 15, 606–616. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.15.6.608

Brehm, J. W. (1966). A theory of psychological reactance. New York, NY:Academic Press.

Burk, W. J., Kerr, M., & Stattin, H. (2008). The co-evolution of earlyadolescent friendship networks, school involvement, and delinquentbehaviors. Revue Français de Sociologie, 49, 499–522.

Burk, W. J., Van der Vorst, H., Kerr, M., & Stattin, H. (2012). Alcohol useand friendship dynamics: Selection and socialization in early, middleand late adolescent peer networks. Journal of Studies on Alcohol andDrugs, 73, 89–98.

Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital.American Journal of Sociology, 94(Suppl.), S95–S20 doi:10.1086/228943

Dishion, T. J., & Owens, L. D. (2002). A longitudinal analysis of friend-ship and substance use: Bidirectional influence from adolescence toadulthood. Developmental Psychology, 38, 480–491. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.38.4.480