Brazil 2014: elections and intercultural issues

Transcript of Brazil 2014: elections and intercultural issues

Jucinara Schena Máster en Comunicación Social

Universitat Pompeu Fabra Comunicación e Interculturalidad

March, 2015

Brazil 2014: elec/ons and intercultural issues

Abstract:

In October 26th 2014 Brazilian people voted on the second round elec<on, choosing between Aécio Neves (PSDB) and Dilma Rousseff (PT). By the end of that Sunday the official announcement gave the victory -‐ and the load of one heavy country -‐ to Rousseff, her second chance of four years governing. The country and the people debate got divided between pro each party, almost half-‐half country arguing his poli<cal view and aQacking others because of a different choice. Far from a civilized and respecTul discussion, it all went as wildfire to a hate speech and intolerance pointed to Brazil’s Northeast popula<on, because Rousseff won in majority of the ci<es in region, against Neves’ Southeast wining. Said this, the present ar<cle intend to allocate the event in the intercultural studies and theories. From works about iden<ty and modernity as Hall and Giddens, intercultural issues in socie<es as Erikson, intercultural and communica<on as Alsina, globaliza<on and interculture facts as MaQhews, and poli<cal behavior as Anderson (2010), and hate speech as Rosenfeld we try to translate the scenery of that <me by an intercultural gaze.

Keywords: Brazil, elec4ons, iden4ty, intercultural issues, intolerance, hate speech, separa4sm

- � -1

26th of October 2014, Brazil. Almost a regular spring Sunday night for the Brazilian

people. If wasn’t the tension wai<ng for the official results announcement of the elected to

govern the country for the next four years. It is supposed to be, since we are in a so called

democracy, a result of the majority. In consequence that more of 50% of the popula<on have

clear and agreed who is the right -‐ the best or less worst -‐ to command one of the biggest

countries in the world -‐ fi`h in territory just behind Russia, Canada, China and USA -‐ and one of

the one of the countries biggest economic development in recent years.

It was the second round of the dispute and just with the two most voted candidates on the

first round. The op<ons for 142.822.026 Brazilian voters where Dilma Rousseff (PT, Par<do dos 1

Trabalhadores, workers party and le` wing) and Aécio Neves (PSDB, Par<do da Social

Democracia Brasileira and right wing party).

Before to talk about what happen a`er the disclosure about the winner it is important to

say that the campaign period was intense and full of debates between the candidates which in

consequence, mo<vated heated discussions on popula<ons agenda. Since the popula<on knew

the main candidates even before the Tribunal Superior Eleitoral announcements -‐ made in July 2

7th 2014 with the beginning of the authorized campaign period -‐, the discussions where 3

already the main menu of the popula<on talky-‐talk. So in Brazil out of 12 months basically 7

where in around poli<cs maQers as first topic in 2014.

The then president Dilma Rousseff started in front, reaching 41.6% of the vote in the first

round, while Aécio surprised to reach 33.6%, against 21.3% of Marina. In the second round,

Dilma confirmed the favori<sm, although by a narrow margin. PT secured the new mandate in

the most disputed presiden<al elec<on of the country's history, obtaining 51.64% of the vote,

against 48.36% of Aécio. 54,499,01 voters gave to Dilma Rousseff (PT) the vote of confidence.

Aécio Neves (PSBD) where behind with 51,041,010 votes. Or just behind, because the difference

was one of the liQlest in the Brazilian elec<ons history.

Official numbers released by Superior Tribunal Eleitoral in May 9th 2014. [hQp://www.tse.jus.br/no<cias-‐tse/1

2014/Maio/jus<ca-‐eleitoral-‐registra-‐aumento-‐do-‐numero-‐de-‐eleitores-‐em-‐2014]

Brazilian Superior Electoral Court [hQp://www.tse.jus.br]2

Announced in the official calendar [hQp://www.tse.jus.br/eleicoes/eleicoes-‐2014/calendario-‐eleitoral#1_1_2014]3

- � -2

So this 2014 <ght compe<<on was the missing element to set fire in the discussion

between ‘winners and losers’. And we may ask, what about all the discussion a`er knowing the

winner of this poli<cian baQle?

In one hand, memes playing with the "whimper" of the Aécio Neves voters. On the 4

other, the game is much heavier. A`er confirming the victory of Dilma Rousseff, numerous

tweets, Facebook posts and prejudiced memes began to be shared across networks. The target

is already known: the Northeast, PT voters and even Bolsa Família beneficiaries (Brazilian social

program to help poor families given a monthly money help), which are called "floaters" and

"lazy". Despite the misconcep<on of anonymity and impunity, prejudice against the Northeast

can be seen in the crime of xenophobia -‐ which is the aversion to different cultures and

na<onali<es.

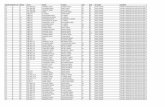

Media vehicles gave its help turning into drawing the votes difference between country

regions as the infographic published by Folha, for example, see map Annex 1. The visualiza<on

of the votes distribu<ons and the colors aQributed to it characterized by each candidate color,

red for Dilma and blue for Aécio, add up to at the same <me simplifying the discourse. As

explained by Santana (2000) the use of infographics by the media, giving preference to the icon

as both diagramma<c metaphorical, seem to fit more properly to the lifestyle of today's

popula<on, since they can be read in a short <me, being predominantly visual, and presen<ng it

in a way a liQle easier to be understood by a larger por<on of the popula<on, although it is

necessary to consider that not all people know "read" the image due to the absence of a

focused educa<onal policy for this purpose.

“It can be consider including that the absence of visual literacy is the determining factor for the success of manipula<ve media, since the readers, remaining without a cri<cal reading of the image, remains alienated from all ideological values, needs and dreams that visual informa<on conveyed by the media imposes and con<nues to believe that is aware what you see.” (Santana, 2000, pp. 80)

Soon the map appeared with extremist ‘retouches’, planning the division of the country

by Dilma voters and non-‐Dilma voters, see map Annex 2. This maneuver was conducted by pro-‐

An Internet meme is a concept que spreads rapidly from person to person via the Internet, largely through 4

Internet-‐based e-‐mailing, blogging, forums, imageboards like 4chan, social networking sites like Facebook or TwiQer, instant messaging, and video hos<ng services like YouTube.” From: hQp://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Meme#Internet_culture

- � -3

Aécio side and widely shared in social media, in less than two hours a`er the disclosure of the

results.

As a reac<on voters reject the <tle of Brazilian and advocate crea<ng a new country on

social networks: "Republic of São Paulo". The result of the second round of elec<ons dominated

social networks with new aQacks on northeastern, but also gave strength to separa<st

movements, which reject the re-‐elec<on of Dilma Rousseff (PT) and fight for a new geographical

division of Brazil. The strongest speech was observed in São Paulo, where the elected Colonel

Tiled (PSDB) declared support for the South and Southeast independence process, except Minas

Gerais and Rio de Janeiro, which had a majority vote to PT. "We must submit to this government

chosen by the North and Northeast? They alone must pay the price", said the poli<cian on his

Facebook profile. This ‘independence’ ideas and this model of speech spread to the millions of

mouths in Brazil and the result was people preaching the extermina<on of people in the

Northeast and North -‐ see annex 3. Exactly, the death of all jus<fied by their vo<ng op<on.

Inspired by the cons<tu<onal revolu<on of 1932 and by European separa<st movements,

such as the Northern League (Italy) and Iden<tarian Catalan (Spain), the group officially

established as ‘MSPI -‐ Movimento São Paulo Independente’ got impulse from the conflic<ve

situa<on and took strong posi<on in placing the separa<on of São Paulo in debate again. As an

example, soon a`er the results MSPI Facebook page went from 8,000 followers to 20,000 in just

hours.

The thrill of that moment to most of Brazilians -‐ didn’t maQer the side one could be -‐ was

really high. Thousands of people wri<ng, making videos giving and uploading it to the web,

blaming one person or a group based on these group iden<<es and characteris<cs filled a hate

speech. An online and live Tower of Babel of intercultural issues inside one huge and so mul<ple

country.

Having in mind that since the democra<za<on of the country, Brazilians, divided, forced

the second round in five of the seven elec<ons for president, it is important to mark that the

polariza<on between the PT and the PSDB has marked the history of these disputes for two

decades: the two par<es have met, as the main protagonists of the race in six direct elec<ons

- � -4

a`er the dictatorship (1964-‐1985). Also, important to men<on that Brazil is a stable democracy

and two par<es have dominated presiden<al elec<ons since 1994. However, its party system -‐

the number and compe<<ve dynamic between exis<ng poli<cal par<es -‐ differs markedly from

what we observe in the US. Brazil's party system also exhibits some of the highest degree of

fragmenta<on in the world (Clark, Gilligan and Golder, 2006). The prolifera<on of par<es not

only makes it hard for voters to understand which, if any, party stands for what they believe in,

but also to iden<fy par<es that stand for a different posi<on. Adding to this confusion, Brazil's

main par<es have converged on the poli<cal center and grown less ideologically dis<nct in

recent years (Power & Zucco, 2009), and all have entered a confusing array of electoral and

governing coali<ons.

Some <me ago, there was a concern to relate the issue of iden<ty to the individual

na<onality. It was important to impose a bond of belonging to the territory where the subject

was. To one there was no need because he knew that he belonged there, there were their

origins and their social rela<ons that were concentrated in the area of proximity. There was no

doubt about the veracity of their na<onality. Basically as Erikson (1972) says that iden<ty is

made up of a “conscious striving for con<nuity, a solidarity with a group’s ideals”. But with the

birth of the modern state, changes and the individual who once enjoyed a close rela<onship

begins to be moved from that place to which he belonged. A good example of the changes

occurred are in the transport revolu<on, which provided a rapid expansion of territories. Thus,

with the development of regions and the consequent legi<macy of the na<on, the problem of

iden<ty would be viewed posi<vely and people just admit their na<onality/iden<ty.

According to Bauman (2005, p. 26):

[...] o nascente Estado moderno fez o necessário para tornar esse dever obrigatório a todas as pessoas que se encontravam no interior de sua soberania nacional. Nascida como ficção, a iden4dade precisava de muita coerção e convencimento para se consolidar e se concre4zar numa realidade […] 5

In this sense, we can see that from the beginning, na<onal iden<ty was seen as a milestone

of state sovereignty. Many <mes, to keep it, even if incomplete, was a huge effort and there

used to be a small amount of force to that na<onality was protected. It is noteworthy that the

Free transla<on: [the rising of the modern state did the necessary to make this mandatory duty to all the people 5

who were inside its na<onal sovereignty. Born as fic<on, iden<ty needed a lot of persuasion and coercion to consolidate and materialize into reality]

- � -5

iden<<es considered “minor” would only be accepted if they do not violate na<onal allegiance,

because the state had the power and nothing could trembles it.

Also according to Bauman (2005), the "iden<fica<on" becomes increasingly important for

individuals who desperately seek a "we" that they may request access. The "new" rela<ons

begin to interfere in our everyday buildings, our social prac<ces as a way of understanding the

world. Thus, iden<<es, previously considered safe and stable, begin to fragment.

And, as explains Alsina (2001), the communica<on vehicles play their role in this scene:

“..paralelamente, los medios de comunicación, por medio de su producción simbólica, van creando representaciones que nos inculcan valores, normas de comportamiento; llevan a cabo procesos de creación iden4taria. Todo 4po de información ins4tuye un "espacio mental" y un "espacio sen4mental", que son el anverso y el reverso de una misma construcción cultural: la que nos une y la que nos separa de los demás. El avance del pensamiento patrimonial pasa por un cambio de mentalidad en la sociedad. ” (Alsina, 2001: 181) 6

We assume, to undertake this discussion, the concept of iden<ty and it is necessary to take

it un<l the postmodern <me. This theore<cal construct is characterized by the break with the

unified subject of vision, cohesive, stable throughout life. Hall (1992/2011) argues that the post-‐

modern subject has become a viable construc<on through various social processes that

occurred in modernity, and would be the result of the reconstruc<on of the modes of economic

expansion and the new understanding of this by various aspects of the academic field. Among

the processes listed by Hall stands globaliza<on, a phenomenon that helped the opening of

cultural boundaries that once seemed unshakable rela<onship by <me and space. The new

rela<onships that have emerged with the decline of these borders allow the occupa<on of other

iden<ty posi<ons, which previously would hardly be accessed.

As Hall (1992/2011) points out, this transi<on from modernity to postmodernity that at the

same <me provides other cultural iden<fica<ons also dismisses the stable anchorage we had

before. These were mainly based on categories of class, ethnicity, gender, sexuality and

na<onality, iden<ty markers described as cons<tuents, not hallmarks of our defini<ons of

ourselves. All that we are and we think comes from our contact with the world. In this sense, an

Free transla<on: […meanwhile, the media, through its symbolic produc<on, they create representa<ons that 6

teach us values, norms of behavior; conduct processes of iden<ty crea<on. Any informa<on establishes a "mental space" and "sen<mental space" which are the verse and reverse of the same cultural construc<on: the one that unites us and what separates us from others. The advance of heritage thought goes through a change of mentality in society.]

- � -6

"I" true, a singular subject is not in the context of postmodernity, as would be determined by a

number of situa<ons, it would be a simula<on of a real subject. And having this in mind

Anderson (2010), who studies iden<ty and its connec<on to poli<cal behaviors, explains that

“the environment in which we operate can influence poli<cal behavior and a}tudes among

individuals, such that experiences resul<ng from interac<ons with others can lead some

individuals to become more or less poli<cally engaged”.

In this ar<cle, the assump<on is that human groups are immersed in a deep process of

cultural change, as Barth (1969) defines as border culture where dialogue (not without conflict)

dis<nct voices, coming from a cultural tradi<on, the other models of the dominant social group

and its ins<tu<ons, and other new hybrid voices arising from new forms of subjec<vity and

meaning produc<on at the interface between visual narra<ves and other cultural narra<ves of

their contexts.

According to Woodward (2000), the complexity of modern life requires that we assume

different iden<<es, which can cause conflicts. We can live in our personal lives, tensions

between our different iden<<es when what is required for an iden<ty interfere with the

requirements of another. Many conflicts arise from the tensions of the rules governing a society.

We live, for example, a heterosexual matrix in which, in the social world, genders must desire

the opposite sex. We know that does not always happen and that if the individual does not

follow the norm is considered an outsider.

As marked by Ribeiro (1995) Brazil, like other countries in American con<nent, received

between mid-‐nineteenth and mid-‐twen<eth century, a huge number of immigrants from

Europe, Asia and the Middle East. The different groups of new immigrants were living in conflict

processes, assimila<on and integra<on, both among themselves and in rela<on to ethnic groups

descendants of Indians, Portuguese and huge majority Africans. Such inter-‐ethnic rela<ons have

le` deep marks on the sociocultural rela<onships that give today in our territory.

In Brazil, the intercultural dimension skins specific meanings. Also Ribeiro (1995)

remembers that colonialism and migra<on, domina<ons and cohabita<on have induced deep

accultura<on processes: syncre<c and violent mergers and cultural iden<ty loss are in the very

forma<on of Brazilian society and were objects of analysis by numerous researchers who sought

to reconstruct a historical-‐anthropological key the developments and mul<form contact results -‐

spontaneous or forced -‐ that took place between the various groups. Intercultural and

- � -7

interethnic rela<ons in Brazil consisted therefore from conflicts inherent to economic cycles of

colonial expansion, which began in the sixteenth century, as well as from the industrial

revolu<ons of the eighteenth-‐nineteenth century, which led to the migra<on towards North-‐

South.

Inherent part of the coexistence of these different groups in constant contact is the hate

speech. The incitement of hatred speeches -‐ hate speeches-‐ are symbolic representa<ons that

express hatred, contempt or disrespect the other person or group. The use of pejora<ve terms

for ethnic groups is a clear example and more widely, it can even include the views that are

extremely offensive to others.

Legally hate speeches, by its name, are quite recent in Brazil, since the debate about

hate speech gained strength with the judgment of the HC 82,424/RS by the Supreme Court in

2003. Siegfried Ellwanger, gaucho writer, pleading the annulment of damning judgment of the

Court of Jus<ce of Rio Grande do Sul, who considered guilty the crime of racism, for wri<ng

books in which he denied the Holocaust, among other events considered an<semi<c. By

majority, the Supreme Court upheld the convic<on.

Michel Rosenfeld (2001) defines hate speeches as those speeches prepared for the purpose

of promo<ng hate and are based on differences of race, religion, ethnicity or na<onality. This is

a restric<on on freedom of expression which regula<on was later phenomenon to the second

great world war and was born by the clear link between the racist propaganda of Nazi Germany

and the Holocaust. Expanding the example, hate speeches are present -‐ before not know by this

exactly name but the phenomena is the same -‐ in human history, probably since the first men

group where formed because essen<ally its all about the acceptance of the others.

As in the theme of the present ar<cle, is important to explain that Northeast of Brazil is

characterized by high levels of poverty, caused by the dry climate, poor farming condi<ons,

manpower explora<on, and fewer government social programs for beQer educa<on and

equality. This scenery composed one extreme scene of Brazil’s reality and it changes to the

opposite moving toward South direc<on. So also, against all North’s characteris<cs, the hate

glance pointed to North and specially Northeast people is connected deeply to economic

maQers.

- � -8

The acceptance of the other’s right to live and make different choices -‐ the basic of a so

called democracy -‐ were le` waving behind by in the context of Brazilian last electoral period.

The media gave some figura<ve elements and from there people, guided pre made opinion

leaders discourse, walked themselves to higher levels of hate speech. This effect poten<ated by

the power of social media that connect all of us in milliseconds.

The geographic and historical forma<on of Brazil helps to explain the characteris<c of

each different cultural group we can define living under the same na<on state actually. The

intercultural studies help to understand the conflicts. Nevertheless its impossible, even we so

far comprehend all the theore<cal background for the intercultural conflicts, that its jus<fies

the hate speech, as saying ‘all the owners of different opinion must die’.

Six months a`er the fact, le` and right, red and blue, PT and PSDB, keep -‐ though a not

so intensive -‐ the conflict. The poli<cal scenery is s<ll unstable and marked by the half-‐half

elec<on results. The hate speech against Northeast people is just in stand by just wai<ng a new

-‐ and some<mes in rou<ne liQle details -‐ opportunity to startle again.

Bibliography Alsina, M. R., & Morla, C. G. (2001). Medios de comunicación e interculturalidad. Cuadernos de información, (14), 8.

Anderson, Mary R. (2010). “Community iden<ty and poli<cal behavior”. United States: Palgrave McMillan.

Bauman, Zygmunt (2005). Iden<dade: entrevista a BenedeQo Vecchi. Trad. Carlos Alberto Medeiros. Rio de Janeiro: Jorge Zahar Ed.

Barth, F. (1969). “Ethnic Groups and Boundaries”. Oslo: Bergen.

BenneQ, M. (1998). “Basic concepts of intercultural communica<on: Selected readings”. Intercultural Press, Inc., PO Box 700, Yarmouth, ME 04096.

Bourdieu, Pierre (1991). “Language and Symbolic Power”. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Brubaker, R.; Cooper, F. (2000). “Beyond 'Iden<ty'”. Theory and Society 29: 1–47

Clark, William Roberts, Michael J. Gilligan and MaQ Golder (2006). “A Simple Mul<variate Test Asymmetric Hypotheses.” Poli<cal Analysis 14(3):311{331.

- � -9

Cohen, A. (1998). “Boundaries and Boundary-‐Consciousness: Poli<cizing Cultural Iden<ty" in M. Anderson and E. Bort (Eds.), The Fron<ers of Europe. London: Printer Press.

Erikson, E. H. (1968). “Iden<ty: Youth and crisis (No. 7)”. WW Norton & Company.

Holliday, A., Hyde, M. and Kullman, J. (2010). “Intercultural Communica<ons”. 2nd ed. London: Routledge.

Giddens, A. (1991). “Modernity and Self-‐Iden<ty: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age”. Cambridge: Polity.

Mathews, G. (2000). “Global Culture/Individual Iden<ty: searching for home in the cultural supermarket”. London: Routledge.

Mead, George H. (1934). “Mind, Self, and Society”. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Power, Timothy and Cesar Zucco (2009). “Es<ma<ng Ideology of Brazilian Legisla<ve Par<es, 1990-‐2005: A Research Communica<on”. La<n American Research Review 44(1):219-‐246.

Ribeiro, D. (1995). “O povo brasileiro -‐ A formação e o sen<do do Brasil”. 2nd Ed. São Paulo: Cia das Letras.

Santana, F. A. (2000) "O ciclo evolu4vo da imagem na comunicação. Master Disserta<on. Faculdade de Arquitetura, Artes e Comunicação. São Paulo: Universidade Estadual Paulista Júlio de Mesquita Filho.

Woodward, K. (2004). “Ques<oning Iden<ty: Gender, Class, Ethnicity”. London: Routledge.

Woodward, K. (2000) “Iden<dade e diferença: uma introdução teórica e conceitual”. In: SILVA, T. T. da (Org.). Iden<dade e diferença: a perspec<va dos estudos culturais. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2000.

- � -10

Annexes: 1. Infographic showed by Folha de São Paulo in the night of the disclosure of elec<on results.

- � -11