Beyond Ideal Types of Municipal Structure: Adapted Cities in Michigan

Transcript of Beyond Ideal Types of Municipal Structure: Adapted Cities in Michigan

Beyond Ideal Types of Municipal Structure:

Adapted Cities in Michigan

Jered B. Carr Wayne State University, Department of Political Science 2017 Faculty/Administration Building, Detroit, MI 48202 E-mail: [email protected] Shanthi Karuppusamy Wayne State University, Department of Political Science 2004 Faculty/Administration Building, Detroit, MI 48202 E-mail: [email protected] Forthcoming in the American Review of Public Administration Authors’ Note: We thank Susan Hannah for providing the data on municipal charters in Michigan used in this analysis. A version of this article was presented at the 2007 meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association. Please address correspondence to Jered B. Carr, Department of Political Science, Wayne State University, 2017 Faculty/Administration Building, Detroit, MI 48202; e-mail: [email protected].

Abstract Increasingly, scholars of local governments are calling attention to a new era of municipal reform and to the convergence of the mayor-council and council-manager forms of governments. A major conclusion of this literature is that these two familiar ideal types no longer adequately describe the structure of most American cities. This paper contributes to this question by examining the charters of 263 Michigan cities. We use the adapted cities framework advanced by H. George Frederickson, Gary Johnson, and Curtis Wood to examine the patterns of adaptation to Michigan’s mayor-council and council-manager cities. We find that the governance structure in most Michigan cities is not accurately described by either of the ideal types. Mayor-council cities are especially likely to use charter provisions that deviate significantly from conventional depictions of the form. Keywords: mayor-council; council-manager; adapted cities; city charter; CAO; Michigan;

reform

Ideal types describe the elements of a given topic, but they are not meant to capture all of

the elements common to cases of the type. Instead, ideal types rely on abstractions to

convey broad insights about its subject. In the case of municipal structure, the ideal types

of mayor-council and council-manager have been used to convey broad insights about

two distinct approaches to the distribution of powers among elected officials, the political

and management leadership exercised by these officials, and the role played by

professional managers at the highest levels of the city government.

These two ideal types have been useful in contrasting very different approaches to

how responsibility and authority are divided among elected and administrative officials,

but their use to convey an understanding of municipal structure has significant

limitations. As James Svara has commented, our ideas about council-manager

governments are based on overly simplistic notions about the absence of conflict and the

dominance of professional managers in these governments (Svara, 1990). Others have

observed that our ideas about the absence of professional managers at the highest levels

in mayor-council cities are seriously at odds with the practice in these cities (Adrian,

1988; Renner & DeSantis, 1993; 1998). This large gap between theory and practice no

doubt results from an excessive reliance on these ideal types to describe how these

governments work.

Over the years, refinements to these two types have been proposed to describe the

significant variation in government structures seen in cities within each category. The

terms strong and weak have long been used to indicate important differences in the

mayoral powers across cities with mayor-council governments, but recent proposals have

sought to highlight the contributions of chief administrative officers (CAOs) to these

1

cities. For example, DeSantis and Renner (2002) combine these two dimensions of

mayoral power to propose four distinct types of mayor-council governments.1 Similar

efforts have been made to categorize the wide variations in mayoral powers within these

governments and to understand differences in mayor-manager relations in council-

manager governments (Morgan & Watson, 1992; Zang & Feiock, 2007). William Hansell

(1998, 1999) suggests four categories of council-manager government that depend on the

powers the charter provides to the mayor.2

However, the most significant effort in this regard is the adapted cities framework

developed by H. George Frederickson, Gary Johnson, and Curtis Wood (Frederickson &

Johnson, 2001; Frederickson, Logan, & Wood, 2003; Frederickson, Johnson, & Wood,

2002; 2004a; 2004b). Their framework builds on the distinctions noted in pervious

efforts, but it is more comprehensive and substantially more ambitious. The adapted cities

framework identifies a wide array of changes locals commonly make to city charters and

provides an explanation for the direction and extent of these changes. The authors

[hereafter FJW] propose that local demands for mayoral leadership, political

responsiveness, and administrative efficiencies are driving American cities toward a

convergence in these two forms.

City governments are still largely designated as council-manager or mayor-

council in practice because many state laws recognize only the two forms. However,

Frederickson and his colleagues suggest that many council-manager cities have been

adapted to function more like mayor-council cities and vice versa. Have the adaptations

they identify so reduced the descriptive power of the two forms that a third category is

necessary? Frederickson and his coauthors clearly think so. “There are more and more

2

American cities with relatively similar structural characteristics and fewer and fewer

classic type I and type II cities” (Frederickson, Johnson, & Wood, 2004a: 329). We are

less sure, but recognize they have raised a very important question. Given the common

use of form of government as an independent variable in empirical research, the question

of how to measure municipal structure is extremely important.

In this paper, we set aside the larger question of the adapted city as a new form of

municipal government and focus on the more immediate task of accurately describing

and categorizing the structure of American city governments. We see this as an important

first step toward answering questions about the number of distinct municipal forms and

how these different forms affect what cities do. Beyond the project FJW used to develop

the adapted cities framework, we know of no other effort to use this framework to

classify municipal governments.3 To this end, we present a process for coding cities into

the adapted cities framework that is transparent and replicable.4 We utilize the

terminology of this framework but adapt it in several ways for our purposes here. Our

focus is on understanding changes in the structure of cities grouped in terms of their

mayor-council and council-manager statutory platforms. This requires modifying the

framework as developed by Frederickson and his colleagues to make these two platforms

the starting point for the purposes of coding the cities.

We use the adapted cities framework to examine the nature and extent of the

variation in the structures used by city governments in Michigan from the ideal type

depictions of mayor-council and council-manager governments. Analyzing municipal

structure within a single state permits us to examine the governance structures used by a

single type of municipal government across a wide range of population levels. Studies

3

relying on national samples often exclude cities under 25,000 people, yet in a state such

as Michigan, more than half of the cities have fewer than 10,000 people. Also, by

limiting the analysis to a single state, we can be sure that these city governments are

subject to the same state statutory environment and share a common state culture and

development history.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: We begin with a brief

overview of the adapted cities framework. We then examine the patterns of structural

adaptation seen in 263 Michigan cities.5 We are primarily concerned with understanding

the nature and extent of the within-platform variation in Michigan cities. Do the mayor-

council and council-manager categories mask substantial variations in the charter

provisions used in these cities? Is this variation, if present, large enough to suggest the

need for multiple categories of cities for each statutory platform? Is there evidence of a

convergence in the structures of mayor-council and council-manager governments? As

noted earlier, others have addressed the question of multiple categories within these two

forms of municipal governments, but never with a conceptual framework as

comprehensive and powerful as the adapted cities framework. We conclude with several

observations about the implications of these findings for our understanding of municipal

government structure.

Insert Table 1 about here

4

The Adapted Cities Framework

FJW are not the first to suggest modifications to our classification of municipal

governments, but their approach is the most comprehensive. Whereas other approaches

have focused on one or two features of these governments, the adapted cities framework

places cities into categories based on the use of nearly twenty different charter provisions.

Importantly, the framework provides an explanation for the direction and extent of these

adaptations by anchoring the analysis in terms of a “political-administrative” dimension

of municipal structure. Cities on the political end of this dimension rest on mayor-council

platforms said to emphasize political leadership and an inclusive, competitive decision-

making process. Cities on the administrative end rest on a council-manager platform said

to emphasize administrative leadership and an insulated decision-making process based

on the application of nonpolitical, expert knowledge to the city’s problems.

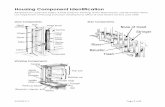

Table 1 displays the charter elements examined by the adapted cities framework.

FJW propose that adapted cities be classified as adapted political, adapted administrative,

or conciliated based on how far the adaptations move a city from the endpoints of the

political-administrative dimension. The story of adapting cities on mayor-council

platforms told by FJW is a movement away from a divided powers structure toward more

professional management and less political conflict. In contrast, the story of adapting

cities on council-manager platforms is about the development of the mayor as an

independent political leader in city government. This change involves a movement away

from a unified powers structure to a separation of the mayor from the city council and

into an autonomous political leader with executive powers.

5

As Table 1 indicates, the framework incorporates three groups of provisions

beyond a city’s statutory platform. The provisions governing the basic characteristics of

the major political offices, such as tenure and professional status, and the size of the city

council comprise the first set. The second set includes the procedures for electing the

mayor and council members. This set highlights how electoral systems affect mayoral

leadership, political conflict, and patterns of representation in the city. The third and final

set includes provisions capturing how the city charter structures the allocation of

administrative authority among the mayor, council, and chief administrative officer

(CAO). This last set of provisions is critical to understanding the extent of the

convergence of the mayor-council and council-manager structures.

Much of the discussion in this section is based on the adaptation process

described in Frederickson, Johnson, and Wood (2004b). The process outlined in this

paper, however, modifies their approach to focus attention on adaptations within cities

grouped by the two statutory platforms of mayor-council and council-manager. We

utilize the terminology of the adapted cities framework but alter it in an important way.

The adapted cities framework employs five categories of cities (political, adapted

political, conciliated, adapted administrative, and administrative), with none restricted to

a specific platform.6 Our approach is to divide the cities into two groups based on their

platform, which creates three potential categories for the cities on each platform. Cities

resting on a mayor-council platform will fall into the political, adapted political, or

conciliated political categories. Cities with a council-manager platform will fall into the

administrative, adapted administrative, or conciliated administrative categories.

6

Adaptations to the Mayor-Council Platform

Political cities utilize the classic mayor-council form; they have a directly elected

mayor and a council elected from districts. City officials are elected on partisan ballots.

The mayor functions as the CAO and wields broad authority over the city’s

administrative departments.

According to FJW, adaptations to mayor-council cities enhance the professional

management capacity of the city in a couple of different ways. First, and most obvious, is

the creation of an appointed CAO position.7 Detection of this provision alone is often

enough to indicate that a political city is adapted. A second element of adapted status in

mayor-council cities is the use of charter provisions that move the city away from a

pattern of administrative decision making by elected officials and toward decisions by

nonelected staff. In adapted political cities, this is mostly achieved by the addition of a

CAO, but other procedures also play a role. These cities are more likely than political

cities to limit mayoral discretion by empowering the council to set the amounts triggering

formal bid processes and maximums for expenditures without council approval. These

cities are also less likely to rely on the direct election of officials leading key

administrative functions, such as the clerk, treasurer, and property assessor. Instead,

adapted political cities are more likely to empower the mayor or council to select these

officials. A final aspect involves the impact of electoral procedures on responsiveness.

FJW find that adapted political cities often move from total reliance on district elections

to a system where one or more council members are elected at-large.

Central to the adaptations cited by the authors as indicating conciliated status are

those that further weaken the mayor as a political leader in the city. Most important are

7

provisions establishing a mayor who functions as part of the city council and who is not

elected by the public. These two provisions strongly affect the mayor’s status as an

independent political actor, and their use in a mayor-council city is sufficient to indicate

conciliated status. The mayor may also not have veto power over council decisions. A

second group of indicators of political conciliated status are charter provisions that

further weaken the role of the mayor in administrative matters. Conciliated cities are

more likely than political or adapted political cities to use provisions that authorize the

council to approve the mayor’s choices for key administrative positions. Other provisions

may strengthen the CAO relative to the mayor. For example, the CAO may be authorized

to prepare the budget and to nominate or appoint key administrators in these cities.

Finally, conciliated political cities also are characterized by changes to the

electoral procedures and the characteristics of major political offices. The authors find

that conciliated cities are more likely than political or adapted political cities to use terms

of less than four years for the mayor and to have smaller councils.

Adaptations to the Council-Manager Platform

Administrative cities reflect the classic council-manager depiction of the city

manager as CAO and at-large elections for city council. The mayor serves on the city

council and is appointed by the other council members. City officials are elected on

nonpartisan ballots. Administrative authority is centralized in an appointed city manager

selected by the city council. In these cities, virtually all administrators are nonelected and

appointed by the city manager.

8

FJW argue that council-manager cities are primarily adapted to enhance the

responsiveness of elected leaders. These enhancements typically focus on strengthening

the political leadership of elected officials, increasing their administrative role, or both.

Efforts to strengthen political responsiveness through adaptations to the council-manager

platform take two forms. First, these cities enhance the ability of the mayor to provide

political leadership to the community. The most common is the direct election of the

mayor. This provision alone may be sufficient to indicate adapted administrative status.

The mayor remains a member of the council, but is now directly accountable to the public

rather than his or her colleagues on the city council. A second avenue to improved

political responsiveness is to encourage the city council to be more responsive to

neighborhoods and other geographic-based interests. A common approach is to use

districts to elect one or more council members. Other adaptations expand the role of the

council in the selection of administrators beyond the CAO. Adapted administrative cities

are more likely to authorize the council to appoint and/or fire a wider range of city

officials than do administrative cities. These cities are also more likely than

administrative cities to empower council to determine the amounts triggering formal bid

processes and council approval of individual expenditures.

The adaptations that suggest conciliated status in council-manager cities are those

that further empower the mayor as a political leader. Conciliated city status is achieved

when the charter defines the mayor as independent of the city council and provides this

position with a meaningful level of executive authority. In practice, this means the charter

separates the position of mayor from the city council. In conciliated administrative cities

the mayor does not vote with council except to break a tie. Other provisions that confirm

9

conciliated status empower the mayor to prepare the city’s budget and appoint key

administrative officials.

Finally, terms for the mayor and city council in excess of two years may indicate

a council-manager city is conciliated. Also, city councils usually meet more often than

the frequency typical for administrative and adapted administrative cities.

Insert Figure 1 about here

Adapted Cities in Michigan

Michigan provides an excellent context to examine how city charters in practice

deviate from the two ideal types. The state has a long history with home rule and its cities

were early adopters of many of the reform structures that comprise the ideal depiction of

council-manager government (Hannah, 1987, 1998). Michigan had a significant urban

population by early in the 20th Century and thus also has a strong tradition of mayor-

council governments. A third of the cities in the state were incorporated before 1910 and

many have retained their mayor-council platforms. By limiting the analysis to

governments in a single state, we examine a more broad range of city populations than is

typical in studies relying on national samples. Little is known about the governance

structure in small cities because analyses regularly exclude these jurisdictions (French &

Folz, 2004).8 Also, a single state analysis permits us to examine how locals have adapted

city government structure to deal with the problems facing their communities while

10

holding a wide range of factors (e.g., state fiscal rules, powers and service responsibilities

of different types of local units, regional development patterns, etc.) constant.

Figure 1 and 2 utilize the charter elements identified by the adapted cities

framework to create a process for coding Michigan’s cities into the six categories.9 The

process illustrated in the two figures is based on how each charter provision is expected

to affect the city’s location on this political-administrative dimension.10 The charter

provisions in each figure are presented in terms of their importance in placing cities along

this dimension. The provisions in the first tier deal with the assignment of basic powers,

such as how the charter defines the autonomy of the mayor and council and the

assignment of authority over the city’s departments. Generally, the provisions in this

group are sufficient to determine if a city belongs in the platform’s base category

(political or administrative) or an adapted category. The second tier provisions reveal

important details about key appointment and budgetary powers, the length of political

offices, and the staff available to elected officials. These provisions permit a deeper

understanding of a city’s structure, and can be particularly useful in deciding where a city

fits between the two adapted categories for each platform.

Insert Figure 2 about here

Figures 3-5 display the Michigan cities classified according to the adapted city

framework.11 A complete list of the cities in each category is provided in the Appendix.

Each of these cities adopted a charter under the procedures set out in the state’s Home

Rule Cities Act of 1909. The cities included in this analysis accounted for 96 percent of

11

the state’s cities in 1998.12 Sixty-nine percent of the cities are on council-manager

platforms and 31 percent are mayor-council cities.13

Figure 3 displays all 263 cities in terms of three categories: political,

administrative, and adapted. The distribution of the cities shown in this figure confirms

FJW’s fundamental point about the evolution of government structure: most cities in

Michigan have adapted structures. Nearly 70 percent of Michigan’s Home Rule cities

have a structure that fits into the adapted category. Only 29 percent of the cities are

classified as administrative and just 3 percent are political cities. We note the proportion

of adapted cities in Michigan (68 percent) is roughly equal to the proportion of FJW’s

national sample (69 percent) reported as adapted.

Insert Figure 3 about here.

Figures 4 and 5 illustrate the patterns of adaptation in terms of each statutory

platform. Figure 4 shows the distribution of the 82 mayor-council cities across the three

categories for this platform. Ninety percent of these cities are classified as adapted

political or conciliated political cities. Thus, few of the cities retain the characteristics of

the mayor-council ideal type, the political city. This pattern confirms another basic

contention of FJW: political cities are increasingly rare. We add to this conclusion that in

Michigan adapted political cities are also rare. One finding revealed by Figure 4 is

striking: the vast majority of mayor-council cities in Michigan are conciliated. It is by far

the modal category for cities on mayor-council platforms, with 83 percent of the mayor-

council cities revealed to be conciliated. In contrast, only 13 percent of FJW’s entire

12

sample was classified as conciliated and less than five of the mayor-council cities in the

sample were found to have a conciliated structure.14

This finding is important. The large difference in the proportion of Michigan

cities that are conciliated from what FJW found nationally is partly due to the coding

process used in this paper and described in the previous section. FJW were far more

restrictive in their interpretation of conciliated structures.15 However, a more important

basis for why so many Michigan mayor-council cities display such extensive adaptations

is that Michigan is a state of small cities.16 FJW’s sample includes no cities under 10,000

people, yet over half (61 percent) of the mayor-council cities we examined had fewer

than 10,000 residents in 2000. In Michigan, small cities on mayor-council platforms often

have conciliated political structures, and the cities in this category are likely to be smaller

than those in the other two mayor-council categories. (See the appendix). This finding is

consistent with FJW’s general arguments about the direction of structural change in

mayor-council governments. Cities with small populations are very likely to benefit from

adaptations that unify political power and enhance administrative capability.

Insert Figure 4 about here.

Figure 5 displays the patterns of adaptation seen in Michigan’s 181 council-

manager cities. Fifty-eight percent of these cities are adapted administrative or

conciliated administrative. The figure also shows that adapted administrative is the modal

category for cities on council-manager platforms. This finding is consistent with what

FJW reported for the council-manager cities in their study. A slight difference from their

13

findings is that administrative cities make up a larger proportion of these cities in

Michigan. Nearly half (42 percent) retain the characteristics of the council-manager ideal

type, the administrative city. By comparison, only 23 percent of the council-manager

cities in FJW’s sample were classified as administrative.

The distribution of council-manager cities in Michigan shown in Figure 5 reveals

that the proportion of cities retaining the characteristics of administrative cities is nearly

double what FJW reported for the council-manager cities in their study of cities

nationally. In this instance, the disparity is not due to differences in the approaches used

by the two studies to code the cities. With the exception of stipulating a council-manager

platform, our requirements for coding administrative cities do not differ from those used

by FJW.17 We conclude that, once again, the difference in the range of city populations

included in the two samples accounts for the variation in the two distributions. Roughly

two-thirds (68 percent) of the council-manager cities we examined had fewer than 10,000

residents. Like their mayor-council counterparts, small council-manager cities are likely

to benefit greatly from the unified political structure and professional management

offered by the administrative city.

Insert Figure 5 about here.

Discussion

The preceding analysis reveals important insights about how the governance

structures in Michigan cities depart from the depictions offered by the two ideal types.

First, substantial majorities of the cities on both platforms have clearly moved away from

14

the structures depicted by the two ideal types. Many mayor-council cities use charter

provisions that reduce the separation of powers between the mayor and council and

authorize nonelected administrators to manage city operations. Similarly, many council-

manager cities utilize charters that provide autonomy for the mayor from the city council

and a meaningful role in running the city’s operations. We cannot conclude from this

finding that a convergence of the two forms is occurring, but we think this analysis shows

a convergence in the values Frederickson, Johnson, and Wood assert are served by

municipal structure has taken place. Viewed from the perspective of how city charters in

Michigan strike a balance between political and administrative values, the adaptations

clearly indicate a move toward the middle of this dimension.

A second insight is that both statutory platforms reveal large within-group

variation in the provisions that comprise the charters of these governments. We take this

finding as an indication that the mayor-council and council-manager structures used by

Michigan cities have undergone significant change. This conclusion does not refer to

adaptations in the governance structure in individual cities, but to an evolution in the

“package” of charter provisions that mayor-council and council-manager cities in

Michigan are likely to adopt.18 The logic of the adapted cities framework describes the

evolution of individual cities, but this framework has much to contribute to our

understanding of the evolution of the two statutory platforms themselves.

A third finding is that the patterns of adaptation within the two platforms differ

substantially. Michigan’s mayor-council cities are remarkable in that nearly all of the

cities examined are in the conciliated category. However, the patterns of adaptation in the

council-manager group are far more modest. Very few of these cities have conciliated

15

structures and nearly half retain the administrative ideal type structure. It underscores the

idea that conceiving of cities simply as council-manager or mayor-council likely masks

significant variation within these two categories. And in this case it highlights that the

adaptations need not be equal across the two platforms. In Michigan, the most extensive

adaptations have been to the cities using the mayor-council form of government.

Suggestions for Future Research

We think the adapted cities framework deserves serious attention from local

government scholars. This framework has the potential to move the field past its tendency

toward excessive simplification on this topic. Many, perhaps most, American cities have

governmental structures that attenuate the values typically ascribed to their mayor-

council or council-manager statutory platforms. The adapted cities framework reflects a

growing recognition of this phenomenon and the increasing gulf between the depictions

provided by the two ideal types and the structures actually used by American cities.

We suggest four directions for future research that we believe may substantially

improve our understanding of this topic. First, we invite others to build upon and refine

our approach to coding municipal governments as adapted cities. We think the adapted

cities framework is an important contribution to the literature on municipal governance.

However, we view the existing framework as merely a starting point, and encourage

others to continue our effort to modify this framework for use in empirical research. We

have modified, and in our view, significantly improved upon FJW’s original framework

by making the boundaries separating the groups within the adapted cities category

clearer. Throughout this study, we have sought to reveal the logic underlying the coding

16

process make the coding decisions completely transparent. We believe the lack of

transparency in the process used by FJW is a reason why this framework has not been

used in previous studies. Like FJW, our logic is based on movements along a political-

administrative dimension. However, we recognize that other values are relevant and the

framework may be improved through efforts to incorporate additional values into the

coding process.

Second, we hope future efforts will apply this framework to cities in other states.

Our findings show that the mayor-council and council-manager nomenclature does not

accurately describe Michigan cities. In this sense, our findings confirm the arguments of

Frederickson, Johnson, and Wood. However, Michigan cities reveal a pattern of

adaptation that suggests the convergence in forms is far from equal. The extent of

structural adaptation seen in Michigan cities differs enormously across the two statutory

platforms. We suspect this finding is due to the large number of mayor-council cities in

Michigan with relatively small populations, but other factors may explain this outcome. It

is entirely plausible that these patterns will vary from one state to the next. Analyses

conducted in states with different statutory environments and histories are necessary to

reveal the patterns of convergence in different state systems.

Third, we hope that future efforts will address the question of the adapted city as a

new form of municipal government. Svara (2005) has expressed strong doubts about this

proposition. Addressing this question will require studies using structural measures based

on the adapted cities framework. The coding process described here and in (Carr &

Karuppusamy, 2008a) permits others to recode cities from the ideal types into the adapted

cities categories. We think the evidence indicates American cities, both large and small,

17

have adapted their structures in ways that make the longstanding dichotomous

classification of mayor-council and council-manager cities no longer descriptively

accurate. FJW contend that these changes have led to the creation of a new form of

government, but evidence beyond describing the extensive variation in charter provisions

is necessary to substantiate this claim. At a minimum, studies demonstrating that the

behavior of elected and administrative officials actually differ across all three “forms” are

needed to address this important question. We encourage other scholars to build upon our

efforts with studies that examine this claim.

Finally, we encourage others to utilize the adapted cities framework to reexamine

the link between government structure and municipal policy. The idea that structure

matters is deeply rooted in the study of urban and local politics. As such, the proposition

that local government structure has important implications for spending and taxation

decisions has been widely embraced by practitioners and academics alike. However,

empirical analyses of this question in terms of council-manager and mayor-council

governments have produced weak and often conflicting findings (Carr & Karuppusamy,

2008b). We think the adapted cities framework has the potential to make a significant

contribution to this literature. It may be that the weak findings from these studies stem

from a measurement problem common to this literature. These studies usually rely on the

two statutory platforms, council-manager and mayor-council, to measure city government

structure. We think that studies using measures based on the adapted cities framework

may reveal that structure does indeed matter in explaining local fiscal policy. And if not,

the use of measures based on the adapted cities framework will greatly strengthen the

case for a null finding for municipal structure and fiscal policy.

18

Notes

1. DeSantis and Renner propose these four categories: strong mayor with CAO, strong

mayor without CAO, weak mayor with CAO, and weak mayor without CAO.

2. Hansell’s suggestions are: classic council-manager, mayor (at-large) council-manager,

mayor (empowered) council-manager, and mayor (separation of powers) council-

manager.

3. The single exception is a study by Wood (2002) using a measure of form of

government developed from the larger dataset created by Frederickson, Johnson, and

Wood. We are not aware of any other effort to apply the adapted cities framework to a

group of cities not in the original set examined by FJW.

4. It is our belief that the lack of a transparent and replicable process for coding cities into

this framework has discouraged the use of this potentially important framework in

empirical research. For additional elaboration on this point, see Carr and Karuppusamy

(2008a).

5. This group is 96 percent of the city governments in Michigan.

6. Political cities are extremely likely to be on mayor-council platforms and

administrative cities are usually on council-manager platforms, but the framework does

not prohibit cities from these two categories from resting on the other platform.

7. This position has several different titles, including chief administrative officer, chief

executive officer, deputy mayor, and chief business officer (Frederickson, Johnson, &

Wood, 2004b: 67).

8. For example, Frederickson, Johnson, and Wood (2004b) exclude cities under 10,000

and over 1 million people.

19

9. The coding process used in this analysis is described in detail in Carr and

Karuppusamy (2008a).

10. Within the two tiers, the provisions are presented in order of their importance to the

coding decisions.

11. Information on the charter for each city was assembled in 1998 by Susan Hannah

based on a “review of each charter, supplemented by interviews with city clerks. The

database was constructed in collaboration with research staff from the Michigan

Municipal League and with financial support from the Earhart Foundation” (Hannah,

1998: 12).

12. By 1998, 263 of Michigan’s 273 cities had adopted charters (CRC, 1999). At present,

all 273 cities have adopted home rule charters.

13. Hannah (1998: 13) notes: “[c]ouncil manager cities so define themselves in their

charters and establish the manager’s position in a specific charter provision. The

International City/County Management Association (ICMA) designates any city that has

a general manager position such as a CAO, whether created by charter or ordinance, as

council manager. The Michigan Home Rule Cities Act, however, requires that cities

wishing to change their form of government must elect a charter commission and

adopting [sic] a revised charter through a referendum. In keeping with the intent of the

Act, we defined cities as council manager only if the manager’s position was provided for

in the charter.”

14. The numbers of cities with each statutory platform in the different categories is

estimated from Figure 7.2 in Frederickson, Johnson, and Wood (2004b).

20

15. Their conception of the category required a merging of the characteristics of political

and administrative cities to the point that they “entirely mix the logic and key structural

characteristics of American city government” (Frederickson, Johnson, & Wood, 2004b:

139). In contrast, our coding for this category focused on a key change in the allocation

of powers in mayor-council cities: the use of charter provisions that make the mayor part

of the city council.

16. Over 90 percent of the state’s 273 cities had populations under 50,000 in 2000, and

one-third had fewer than 2,500 residents. The population of each city used in the analysis

is reported in the appendix.

17. Consistent with FJW, direct election of the mayor is key to adapted administrative

status. Fifty-seven percent of Michigan council-manager cities directly elect the mayor.

18. The charter data used in this analysis do not indicate when individual charter

provisions are adopted by the city. Thus we cannot identify which provisions were

included in the original city charter and which were added through amendment.

21

References

Adrian, C. (1988). Forms of city government in American history. In Municipal yearbook

1988 (pp. 3-11). Washington, DC: International City/County Management

Association.

Carr, J. B., & Karuppusamy, S. (2008a). The adapted cities framework: On enhancing its

use in empirical research Urban Affairs Review 43(5), In-press.

Carr, J. B., & Karuppusamy, S. (2008b). City structure and spending: A reassessment and

extension. Paper presented at the annual meetings of the American Society for

Public Administration, Dallas, TX, March 8-11.

Citizens Research Council of Michigan [CRC]. (1999). A bird’s eye view of Michigan

local government at the end of the Twentieth Century. Report No. 326. Livonia,

MI: Citizens Research Council of Michigan.

DeSantis, V., & Renner, T. (2002). City government structures: An attempt at

clarification. In H. George Frederickson and John Nalbandian (Eds.), The future

of local government administration: The Hansell symposium (pp. 71-80).

Washington, DC: International City/County Management Association.

Frederickson, H. G., & Johnson, G. (2001). The adapted American city: A research note.

Urban Affairs Review 36(6), 872-84.

Frederickson, H. G., Logan, B., & Wood, C. (2003). Municipal reform in mayor-council

cities: A well-kept secret. State and Local Government Review 35(1), 7-14.

Frederickson, H. G., Johnson, G., & Wood, C. (2002). Type III cities. In H. George

Frederickson and John Nalbandian (Eds.), The future of local government

22

administration: The Hansell symposium (pp. 85-87). Washington, DC:

International City/County Management Association.

Frederickson, H. G., Johnson, G., & Wood, C. (2004a). The changing structure of

American cities: A study of the diffusion of innovation. Public Administration

Review 64(3), 320-30.

Frederickson, H. G. Johnson, G., & Wood, C. (2004b). The adapted city: Institutional

dynamics and structural change. Armonk, NY: ME Sharpe.

French, P. E., & Folz, D. (2004). Executive behavior and decision making in small US

cities. The American Review of Public Administration 34(1), 52-66.

Hannah, S. B. (1987). Checks and balances in local government: City charter

amendments and revisions in Michigan 1960-1985. Journal of Urban Affairs 9(4),

337-53.

Hannah, S. B. (1998). Form and function in Michigan local government. Paper presented

at the Midwest Political Science Association, Chicago, IL, April 23-25.

Hansell, B. (1998). Is it time to “reform” the reform? Changes in the council-manager

form of government. Public Management 80(12), 15-16.

Hansell, B. (1999). Reforming the reform: Variations on mayor-council form of

government, part 2. Public Management 81(1), 28.

Morgan, D., & Watson, S. (1992). Policy leadership in council-manager cities:

Comparing mayor and manager. Public Administration Review 52(5), 438-45.

Renner, T., & DeSantis, V. (1993). Contemporary patterns and trends in municipal

government structures. In Municipal yearbook 1993 (pp. 57-69). Washington:

International City/County Management Association.

23

Renner, T., & DeSantis, V. (1998). Municipal forms of government: Issues and trends. In

Municipal yearbook 1998 (pp. 30-41). Washington: International City/County

Management Association.

Svara, J. (1990). Official leadership in the city: Patterns of conflict and cooperation.

New York: Oxford University Press.

Svara, J. (2005). Exploring structures and institutions in city government. Public

Administration Review 65(4): 500-06.

Wood, C. (2002). Voter turnout in city elections. Urban Affairs Review 38(2): 209-31.

Zang, Y., & Feiock, R. (2007). City manager policy leadership: Patterns and mechanisms

of power in council-manager cities. Paper presented at the 9th Public Management

Research Conference, Tucson, AZ, October 25-27.

Jered B. Carr is associate professor of political science and director of the Graduate

Program in Public Administration at Wayne State University. His current research

focuses on local government structure, municipal services cooperation, and metropolitan

governance. He is co-editor of City-County Consolidation and its Alternatives:

Reshaping the Local Government Landscape (ME Sharpe, 2004).

Shanthi Karuppusamy is a doctoral student in political science at Wayne State

University. Her research and teaching interests are in local government and urban

politics. Her research has been published in Urban Affairs Review.

24

Appendix Michigan Cities by Adapted Cities Category

Political (N=8) (Median Pop, 66,002) (Median Year of Incorp, 1929) Coleman (1,296) Dearborn Heights (58,264) Detroit (951,270) Highland Park (16,746) Livonia (100,545) Pontiac (66,337) Warren (138,247) Whitehall (2,884) Adapted Political (N=6) (Median Pop, 68,747) (Median Year of Incorp, 1960) Dearborn (97,775) Gladwin (3,001) Rochester Hills (68,825) Romulus (22,979) Southfield (78,296) Westland (86,602) Conciliated Political (N=68) (Median Pop, 4,689) (Median Year of Incorp, 1949) Allen Park (29,376) Bridgman (2,428) Burton (30,308) Carson City (1,190) Cedar Springs (3,112) Center Line (8,531) Clio (2,483) Coloma (1,595) De Witt (4,702) Ecorse (11,229) Fennville (1,459) Ferrysburg (3,040) Flat Rock (8,488) Flint (124,943) Fraser (15,297) Gaastra (339) Galesburg (1,988) Gibraltar (4,264) Gobles (815) Grand Blanc (8,242) Grand Ledge (7,813) Grant (881) Grosse Pointe (5,670) Grosse Pointe Park (12,443) Hamtramck (22,976) Harbor Beach (1,837) Harrison (2,108) Hillsdale (8,233)

Kentwood (45,255) Kingsford (5,549) Laingsburg (1,223) Lake Angelus (326) Lake City (923) Lansing (119,128) Lincoln Park (40,008) Litchfield (1,458) Luna Pier (1,483) Manton (1,221) Mason (6,714) Melvindale (10,735) Memphis (1,129) Milan (4,775) Monroe (22,076) Morenci (2,398) Muskegon Heights (12,049) New Baltimore (7,405) Norton Shores (22,527) Olivet (1,758) Orchard Lake Village (2,215) Perry (2,065) Petersburg (1,157) Reading (1,134) River Rouge (9,917) Rockwood (3,442) Saline (8,034) Southgate (30,136) Stanton (1,504) Stephenson (875) Taylor (65,868) Trenton (19,584) Utica (4,577) Walker (21,842) Walled Lake (6,713) Watervliet (1,843) White Cloud (1,420) Woodhaven (12,530) Wyandotte (28,006) Zeeland (5,805) Conciliated Administrative (N=13) (Median Pop, 8,507) (Median Year of Incorp, 1883) Auburn Hills (19,837) Bay City (36,817) Charlevoix (2,994) Corunna (3,381) Dowagiac (6,147) Grandville (16,263) Kalamazoo (77,145) Lapeer (9,072)

Ludington (8,357) Marlette (2,104) Newaygo (1,670) Niles (12,204) Royal Oak (60,062) Adapted Administrative (N=92) (Median Pop, 6,720) (Median Year of Incorp, 1927) Adrian (21,574) Albion (9,144) Alpena (11,304) Ann Arbor (114,024) Auburn (2,011) Bad Axe (3,462) Bangor (1,933) Belleville (3,997) Benton Harbor (11,182) Berkley (15,531) Big Rapids (10,849) Cadillac (10,000) Charlotte (8,389) Village of Clarkston (962) Clawson (12,732) Coldwater (12,697) Coopersville (3,910) Crystal Falls (1,791) Davison (5,536) East Grand Rapids (10,764) East Tawas (2,951) Eastpointe (34,077) Eaton Rapids (5,330) Evart (1,738) Fenton (10,582) Ferndale (22,105) Flushing (8,348) Frankenmuth (4,838) Frankfort (1,513) Fremont (4,224) Garden City (30,047) Gaylord (3,681) Grand Haven (11,168) Grand Rapids (197,800) Grosse Pointe Woods (17,080) Harbor Springs (1,567) Hart (1,950) Hartford (2,476) Hastings (7,095) Hazel Park (18,963) Holland (35,048) Howell (9,232) Hudsonville (7,160) Huntington Woods (6,151)

25

Adapted Administrative (Continued) Inkster (30,115) Ionia (10,569) Ishpeming (6,686) Ithaca (3,098) Jackson (36,316) Leslie (2,044) Linden (2,861) Madison Heights (31,101) Marine City (4,652) Marshall (7,459) Marysville (9,684) Menominee (9,131) Montague (2,407) Montrose (1,619) Mount Clemens (17,312) Mount Morris (3,194) Muskegon (40,105) North Muskegon (4,031) Northville (6,459) Novi (47,386) Oak Park (29,793) Onaway (993) Petoskey (6,080) Pinconning (1,386) Pleasant Ridge (2,594) Portage (44,897) Riverview (13,272) Rogers City (3,322) Roseville (48,129) Sault Ste. Marie (16,542) South Haven (5,021) South Lyon (10,036) Springfield (5,189) St. Clair (5,802) St. Clair Shores (63,096) St. Ignace (2,678) St. Louis (4,494) Standish (1,581) Sterling Heights (124,471) Sturgis (11,285) Tawas City (2,005) Three Rivers (7,328) Troy (80,959) Wayland (3,939) West Branch (1,926) Wixom (13,263) Wyoming (69,368) Ypsilanti (22,362)

Administrative (N=76) (Median Pop, 4,308) (Median Year of Incorp, 1926) Algonac (4,613) Allegan (4,838) Alma (9,275) Au Gres (1,028) Battle Creek (53,364) Belding (5,877) Bessemer (2,148) Birmingham (19,291) Bloomfield Hills (3,940) Boyne City (3,503) Brighton (6,701) Bronson (2,421) Buchanan (4,681) Caspian (997) Cheboygan (5,295) Clare (3,173) Croswell (2,467) Durand (3,933) East Jordan (2,507) East Lansing (46,525) Escanaba (13,140) Essexville (3,766) Farmington (10,423) Farmington Hills (82,111) Gladstone (5,032) Grayling (1,952) Greenville (7,935) Grosse Pointe Farms (9,764) Hancock (4,323) Harper Woods (14,254) Houghton (7,010) Hudson (2,499) Imlay City (3,869) Iron Mountain (8,154) Iron River (1,929) Ironwood (6,293) Keego Harbor (2,769) Lathrup Village (4,236) Lowell (4,013) Manistee (6,586) Manistique (3,583) Marquette (19,661) Midland (41,685) Mount Pleasant (25,946) Munising (2,539) Negaunee (4,576) New Buffalo (2,200)

Norway (2,959) Otsego (3,933) Owosso (15,713) Parchment (1,936) Plainwell (3,933) Plymouth (9,022) Port Huron (32,338) Portland (3,789) Potterville (2,168) Reed City (2,430) Richmond (4,897) Rochester (10,467) Rockford (4,626) Roosevelt Park (3,890) Saginaw (61,799) Saugatuck (1,065) Scottville (1,266) St. Joseph (8,789) St. Johns (7,485) Stambaugh (1,243) Swartz Creek (5,102) Sylvan Lake (1,735) Tecumseh (8,574) Traverse City (14,532) Vassar (2,823) Wakefield (2,085) Wayne (19,051) Williamston (3,441) Zilwaukee (1,799)

NOTES: Classification based on charter provisions in 263 Michigan Home Rule cities in 1998. The city’s population in 2000 is included in parentheses. Political, Adapted Political, and Conciliated Political cities rest on mayor-council statutory platforms. Administrative, Adapted Administrative, and Conciliated Administrative cities rest on council-manager statutory platforms.

26

Table 1: Charter Elements Captured by the Adapted Cities Framework Statutory Platform Legal Platform (Mayor-Council or Council-Manager) Used by City Characteristics of Major Political Offices Length of Mayor’s Term Mayor’s Status as Full- or Part-Time Official Length of Terms for Members of City Council Status of Council Members as Full- or Part-Time Officials Number of Seats on City Council Election Procedures Use of Party Affiliation in City Elections Process Used to Elect/Select the Mayor Process Used to Elect Council Members Allocation of Administrative Authority among the Mayor, Council, and CAO Formal Participation of Mayor in Decisions of City Council Powers of the Mayor to Veto Council Decisions Provision of Staff for Mayor Provision of Staff for Members of City Council Assignment of Power to Determine Contracting and Purchasing Policies Assignment of Power to Determine Staffing Policies Authorization by Charter of Appointment of a CAO Assignment of Power to Nominate/Appoint CAO Assignment of Power to Nominate/Appoint Charter Officers Assignment of Power to Appoint/Supervise Department Managers

Source: Based on Table 1 (Frederickson, Johnson, and Wood, 2002, page 87), Table 1 (Frederickson, Johnson, and Wood, 2004a, page 324) and, Figure 1.3 (Frederickson, Johnson, and Wood, 2004b, page 9)

Figure 1: Charter Provisions in Michigan Home Rule Cities on Mayor-Council Platforms

ADAPTATIONS TO THE MAYOR-COUNCIL PLATFORM

ADMINISTRATIVE ADAPTED POLITICAL

POLITICAL

ADMINISTRATIVE CONCILIATED

POLITICAL

POLITICAL

CITY

POLITICAL

First Tier Provisions 1. Charter does not authorize a nonelected CAO position. Mayor is CAO. 2. Mayor is directly elected by the public. 3. Council members are usually elected at-large. 4. Mayor does not serve on council.

First Tier Provisions 1. Charter authorizes CAO position. 2. Mayor is directly elected by the public. 3. Council members are usually elected at-large, but sometimes by district or mixed system. 4. Mayor does not serve on council.

First Tier Provisions 1. Charter usually authorizes CAO position. 2. Mayor is directly elected or selected from council.3. Council members are usually elected at-large. 4. Mayor usually serves on council.

Second Tier Provisions 1. Mayor and council serve a term of 4 years. 2. Mayor has veto power. 3. Council is large (7 or more members). 4. Mayor prepares the budget. 5. 6. Council meets twice per month. 7. Charter likely silent on standing committees. 8. Bid/purchase limits are either specified by charter or set by council.

Second Tier Provisions 1. Mayor often serves term of 2 years or less; councilsometimes less than 4 years. 2. Mayor does not have veto power. 3. Council is small (7 or less members). 4. Mayor/CAO/Clerk prepares the budget. 5. 6. Council meets once/twice per month. 7. Charter likely silent on standing committees. 8. Bid/purchase limits are usually specified by charter and at times set by council.

Clerk Treasurer City Assessor Usually Direct Direct Appt. by election election mayor At times Appt. by Appt. by Joint appt. by council council or mayor & or mayor mayor council

Second Tier Provisions 1. Mayor and council serve a term of 4 years. 2. Mayor has veto power. 3. Council is large (7 or more members). 4. Generally the mayor prepares the budget. 5. 6. Council usually meets twice per month. 7. Charter likely silent on standing committees. 8. Bid/purchase limits are usually specified by charter and at times set by council.

Clerk Treasurer City Assessor Usually Direct Direct Appt. by election election mayor At times Appt. by Joint appt. Joint appt. by council by mayor mayor & & council council

Clerk Treasurer City Assessor Usually Appt. by Appt. by Appt. by council council council At times Direct Direct Joint appt. by election election mayor & council

Figure 2: Charter Provisions in Michigan Home Rule Cities on Council-Manager Platforms

ADAPTATIONS TO THE COUNCIL-MANAGER PLATFORM

POLITICAL ADAPTED

ADMINISTRATIVE

ADMINISTRATIVE

ADMINISTRATIVE CITY

POLITICAL CONCILIATED

ADMINISTRATIVE

ADMINISTRATIVE

First Tier Provisions 1. Charter authorizes the appointment of a CAO (usually called “city manager”). 2. Mayor is selected by council. 3. Council members are elected at-large. 4. Mayor serves on council.

First Tier Provisions 1. Charter authorizes the appointment of a CAO (usually called “city manager”). 2. Mayor is directly elected by the public. 3. Council members are elected at-large and at times by district/mixed system. 4. Mayor serves on council.

First Tier Provisions 1. Charter authorizes the appointment of a CAO (usually called “city manager”). 2. Mayor is directly elected or selected by council. 3. Council members are usually elected at-large and at times by district. 4. Mayor usually does not serve on council.

Second Tier Provisions 1. Mayor often serves term of 2 yrs. or less; council sometimes less than 4 yrs. 2. Mayor does not have veto power. 3. Council is small (7 or less members). 4. City manager prepares the budget. 5. 6. Council meets once/twice per month. 7. Standing committees prohibited or charter silent. 8. Usually charter specifies bid/purchase limits.

Second Tier Provisions 1. Mayor often serves term of 2 yrs. or less; council sometimes less than 4 yrs. 2. Mayor does not have veto power. 3. Council is small (7 or less members). 4. City manager prepares the budget. 5. 6. Council meets once/twice per month. 7. Charter likely silent on standing committees. 8. Bid/purchase limits are specified by charter or set by council.

Second Tier Provisions 1. Mayor and council serve terms of 4 yrs. or less. 2. Mayor does not have veto power. 3. Council is large (7 or more members). 4. City manager usually prepares the budget. 5. 6. Council usually meets twice per month. 7. Charter likely silent on standing committees. 8. Bid/purchase limits are specified by charter or set by council.

Clerk Treasurer City Assessor Joint app Joint appt Appt. by mngr. Usually by mngr. by mngr. & council & council At Appt. by Appt. by Joint appt. by times council mngr. mngr. & council

Clerk Treasurer City Assessor Usually Appt. by Appt.by Appt. by council council council Joint appt Joint appt. Joint appt. by At by mngr. by mngr. mngr. & times & council & council council

Clerk Treasurer City Assessor Usually Joint appt. Joint appt Appt. by council by mngr. by mngr. & council & council At Direct Appt. by Joint appt. by times election council mngr. & council

Figure 3: 263 Michigan Cities Classified by Adapted Cities Framework

250

200

150

100

50

0

76

179

8

Political City Adapted City Administrative City

Cou

nt

City Category

Figure 4: 82 Michigan Mayor-Council Cities Classified by Adapted Cities Framework

60

40

20

0

68

68

Cou

nt

Political Adapted Political Conciliated Political

City Category