Berlin Remembers 13 August 1961

Transcript of Berlin Remembers 13 August 1961

This article was downloaded by: [University of Michigan]On: 06 May 2012, At: 07:31Publisher: RoutledgeInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registeredoffice: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

The Germanic Review: Literature,Culture, TheoryPublication details, including instructions for authors andsubscription information:http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vger20

Berlin Remembers 13 August 1961Mila Ganeva aa Miami University of Ohio

Available online: 29 Mar 2012

To cite this article: Mila Ganeva (2012): Berlin Remembers 13 August 1961, The Germanic Review:Literature, Culture, Theory, 87:1, 91-102

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00168890.2012.654441

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Anysubstantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing,systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representationthat the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of anyinstructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primarysources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings,demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly orindirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

The Germanic Review, 87: 91–102, 2012Copyright c! Taylor & Francis Group, LLCISSN: 0016-8890 print / 1930-6962 onlineDOI: 10.1080/00168890.2012.654441

Briefly Noted

Berlin Remembers 13 August 1961

Mila Ganeva

This article reviews some of the public events in the summer 2011 surrounding thefiftieth anniversary of the building of the Berlin Wall: various photographic exhibitionsin galleries and public spaces and the film documentary, Bis and die Genze. Der privateBlick auf die Mauer (2011), made up entirely of privately filmed home movies. The styleof this year’s commemoration lacked the mixture of euphoria, playfulness, and politicalpomp that marked the anniversary of the fall of the wall two years ago. Although thecommemorations were surrounded by inevitable media buzz, they nevertheless managedto reveal a level of thoughtfulness that defies cynicism and was meaningful to many ofthe Berliners who have lived with the wall.

Keywords: Berlin, Berlin Wall (1961–89), cold war, documentary film, memory,photography

T he Berlin Wall has been gone for more than twenty years now. All eighty-seven milesof it that encircled West Berlin disappeared very soon after unification, as regular urban

infrastructure—parks, roads, and community garden plots—replaced the insurmountablefortifications and covered up the scars of the past. For the most part, the wall was gonesymbolically, too, as the cold war confrontations that it represented by its very existencehave lost their geopolitical relevance in today’s world. It receded gradually from everydaypublic awareness and into abstractness; it moved to the indexes of Berlin travel guides, theitineraries of popular biking tours, and the pages of German grade-school history books. Eventhe elation caused by the unexpected fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 has slipped into the dullrhythm of normality. What remains of it now, physically, are small individual sections thathave been carefully preserved here and there as monuments. Other, less palpable, remnantsare found in Berliners’ private stories and personal recollections of the time before and duringthe wall, accounts that are usually of little interest to the wide public, unless there is a majoranniversary coming up.

91

Dow

nloa

ded

by [U

nive

rsity

of M

ichi

gan]

at 0

7:31

06

May

201

2

92 THE GERMANIC REVIEW ! VOLUME 87, NUMBER 1 / 2012

The year 2011 marks the fiftieth anniversary of 13 August 1961, the day when thepostwar division between East Berlin and West Berlin was sealed, irrevocably as it seemed, foralmost three decades. In the early morning hours, following Walter Ulbricht’s secret orders,East German special forces started operation “Rose”: A barbed wire fence was erected alongthe sector border, and roads and railway crossings were closed to stem the stream of EastGermans fleeing to the West (between 2.8 and 3.2 million in the preceding decade, accordingto different sources). Soon thereafter, bricks and mortar were used to reinforce the closure ofthe border; residential buildings in the vicinity were evacuated and later leveled. Eventually,a concrete twelve-foot-high double wall, complete with a death strip and guard towers, cameto be known as the “Berlin Wall” and stood until 1989.

For a few weeks in the summer of 2011 the wall was back and ubiquitous. “Back” in thebest possible fashion: as a haunting black-and-white image in numerous publicly displayedphotographs, as the subject of documentary films shown on different TV channels, and as theghost summoned up by eyewitness accounts and story-telling workshops. The initial, slightlycynical, reaction of Berliners and visitors alike might have been a sense of deja vu mixedwith blase: Wasn’t it less than two years ago that the fall of the wall was celebrated by theGerman government with guests from all over Europe? Back then a ceremonious topplingof giant dominos in front of the Brandenburg Gate was meant to represent the collapse ofcommunism in Eastern Europe. And isn’t this, again, a media-driven event targeting largeraudiences and attracting even more tourists to the city? It seems that the media, especially thenewspaper Der Tagesspiegel, have played a significant role in publicizing this most recentanniversary, saturating the public space with images and organizing various events. Couldit be that Germans have become professional “rememberers” who, directed by “memorypoliticians,” have perfected the art of putting on carefully coordinated, well-publicized, andmultifaceted commemorations of the wall, even while the public at large, especially beyondBerlin, remains indifferent?1

Many observers, weary of public acts of recollection and skeptical of their effec-tiveness, may have been tempted to ignore all of last year’s commemorative events. Therewere also those who opposed the official ceremonies for ideological and political reasons.According to a survey of the Berliner Zeitung, some 30 percent of Berliners today deemthe construction of the wall justified or partly justified to stop the exodus of East Germans.During a convention in Rostock, members of the party Die Linke refused to stand up andkeep a minute of silence at noon on 13 August in remembrance of the victims of the wall.Some of their leaders such as Gesine Lotzsch stood firmly behind a position paper of theparty that qualified the building of the Berlin Wall as a logical consequence of World WarII and a necessary development, since it had kept the peace in Europe. On the day of theanniversary, the left-radical newspaper, Die junge Welt, published a full-page “thank you” tothose who kept the Berlin Wall in place for twenty-eight years, an attention-grabbing movethat triggered loud protests even within Die Linke.

Yet, apart from these scandals and on closer inspection, the variety of events surround-ing the anniversary reveals a level a thoughtfulness that defies cynicism and is meaningfulto many of the Berliners who have lived with the wall. None of the mixture of euphoria,

1See Klaus Hartung, “Der blinde Fleck,” Der Tagesspiegel 17 July 2011. www.tagesspiegel.de

Dow

nloa

ded

by [U

nive

rsity

of M

ichi

gan]

at 0

7:31

06

May

201

2

GANEVA ! BRIEFLY NOTED 93

playfulness, and political pomp that marked the fall of the wall anniversary could be seenin this year’s events. Ultimately, all the media buzz served as a catalyst of shared acts ofremembrance in various places in Berlin that were much more low key, less flashy, and lesspolitical than the festivities two years ago.

It was impressive to see how people would stop in their tracks near former significantsites of the wall now marked by big photographic panels with archival images. Particu-larly popular were two installations in two of the busiest train stations. The first one, “Dergeteilte Bahnhof” at Friedrichstraße, documents how this train station served as the onlyrailroad checkpoint over the inner-city border and where the iron curtain was not meantonly metaphorically but formed, literally, as a Stahlwand, the physical division between twoplatforms (a real iron curtain), the one for the trains from the East that ended there, and theone that formed a West Berlin enclave for the trains heading to the West. For twenty-eightyears, the Friedrichstraße station was transformed into a complicated labyrinth of passages,bridges, fences, and fortifications.

The second exhibit, “Border Stations and Ghost Stations in the Divided City” atNordbahnhof S-Bahn Station, with its spectacular photographs, shows how the urban mass-transit system was affected by the wall. Two lines of the subway and one line of the city traincrossed underneath East Berlin territory; the stations they passed through without stoppingwere closed and heavily guarded, thus becoming effectively “ghost stations.” At the exhibit,passersby crowded around the exhibition panels, studying the curious photographic material,many explaining the pictures to their children. Others spontaneously started exchangingpersonal stories with strangers who would listen. It seems that Berliners who fifty yearsago became, against their will, powerless pawns within the cold war’s game of chess finallyreclaimed their ownership of that painful past and their desire to share the experiencessurrounding the wall in their own voices, with their own pictures.

Most significantly, the central locations of 2011’s subdued commemorations of 13August 1961 shifted from the Brandenburg Gate and Checkpoint Charlie—two huge touristhubs with Disney-park allure that served also as focal points of the celebrations in 2009—toBernauer Street. A quiet residential street until that day in August, Bernauer Street becamethe site of painful division and dramatic escapes when the people in the buildings foundthemselves in the East while the sidewalk under their windows remained in the West. Sincethe late 1990s, the area along Bernauer Street has been transformed into an open-air memorialcomplete with a documentation center, the Chapel of Reconciliation, and one of longestsections of the wall preserved. In recent years the park has been enlarged and redesigned, andshortly before the 2011 summer festivities an expanded memorial site was unveiled.2 Recenturban archeological discoveries are framed as “windows” that offer insight into the everydaylife of the city that was partly shaped, partly destroyed by the wall. Scattered in the parkare information stands that explain the site and provide historical context, primarily throughaudio witness accounts and many personal photographs. The “Window of Remembrance,”completed in 2010, is a central element on the grounds of the former Sophien cemetery,serving as memorial to the more than 130 people who lost their lives at the Berlin Wall. At

2When it is completed in 2012, it will stretch for almost a mile along the former border strip and coveralmost eleven acres of park.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [U

nive

rsity

of M

ichi

gan]

at 0

7:31

06

May

201

2

94 THE GERMANIC REVIEW ! VOLUME 87, NUMBER 1 / 2012

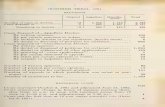

FIGURE 1. “Gedenkstatte Berliner Mauer” at Bernauer Street. Photo by the author. (Color figure available online.)

the edge of the park, a formation of red-rusted steel poles, approximately the same height asthe wall, twelve feet, mark the exact run of the former border strip that drew a sharp line ofseparation between the East and West. (See figure 1.) The rust covering the poles underscoresthe transient nature of all walls, despite the political intentions of their builders: No divisionsare destined to last forever. At the same time, the poles are spaced irregularly but alwaysat a distance that allows a free passage in-between, from one side to the other. Thus, whileevoking memories of the historic Berlin Wall, both the material chosen for the new wall-likememorial and the design of the pole formation present a subtle visual counterpoint to theconcrete monster that once sundered this street.

Even a quick look at the roster of commemorative events during the month of Augustreveals that the visual medium was the chosen vehicle for conveying authenticity and pro-voking reflection. Berlin was inundated with all kinds of visual reminders of the past: fromphotographic panels in public places, streets, and train stations, to photographic exhibits inprivate art galleries, new memorials, film series, and film premieres. In their entirety, thevisual displays shifted the vantage point away from the political grand narratives and thepropaganda posters that many people of certain generations are well familiar with. The visualextravaganza accompanying the 2011 anniversary tended to focus exclusively on the humanand specifically local dimensions of history and everyday life in the shadow of the wall.Glimpses through the camera lenses at daily routines in the divided city—the humiliations,

Dow

nloa

ded

by [U

nive

rsity

of M

ichi

gan]

at 0

7:31

06

May

201

2

GANEVA ! BRIEFLY NOTED 95

the absurdities, the family separations, and the tragedies of the people who lost their livesattempting to cross the inner-city border—proved a powerful mnemonic device for this year’scommemorations. Although there were virtually no ground-shaking historical studies on theoccasion of the anniversary to shed new light on the events of fifty years ago,3 artists andwriters did capture attention with spectacular projects involving original research and thecreative use of rare archival material.

One would think that privileging the visual medium within the array of commemorativeevents would create somewhat of a representational misbalance—after all, the Berlin Wallwas photographed and filmed mostly from the West because private citizens in the East wereprohibited by law to come near it and take pictures of it. Whatever official photographs of thewall were taken, they were subject to the highest secrecy until the end of the regime. But thearray of shows reviewed below demonstrates that this “other view,” the view from the Eastand the view from below, is very much there, well preserved in private and public archives,and promising surprising discoveries.

One of the exhibits that is more conventional in format, but fascinating with thetreasure trove of previously unseen photographic material on display, is dedicated to everydaylife in the little-known community of Klein-Glienicke (“Hinter der Mauer: Glienicke. Ortder deutschen Teilung”). A village with less than five hundred residents, Klein-Glieneckepresented a tiny piece of East Germany wedged in West Berlin territory between Wannseeand Potsdam, completely surrounded by the wall and condemned to depressing isolationfor twenty-eight years. Yet, the photographic images retrieved from private sources for theexhibit bring out in sharp relief the aspects of daily life in the shadow of the wall. The thingabout this place is that in whatever direction people turned, they couldn’t help but see thewall: whether they were watering the garden, hanging the laundry, attending a funeral, orwatching their children ride bikes, the wall was always in the background and unavoidable.And although it was strictly forbidden, people in this Eastern enclave did inadvertently breakthe law and photograph it as a constant background to their family activities. Some of themeven managed to develop the films when they were away, on vacation in a different part ofthe German Democratic Republic (GDR)—where the photography labs would not recognizethe image of the wall—and kept the pictures in their family albums.

“The Other View: The Early Berlin Wall” is the title of an exhibit with about threehundred panoramic photographs following the course of the wall through Berlin from theperspective of those who built it. Searching on another occasion in Potsdam’s military archivesome time ago, author Annett Groschner came across a box full of rolled up 35-mm filmnegatives. Shot by soldiers of the East German border patrol in late 1965 and early 1966,

3At the center of many discussions during historical conferences and in the press was well-knownwork, for example, Hope M. Harrison’s 2003 groundbreaking study Driving the Soviets up the Wall:Soviet-East German Relations, 1953–1961 (Princeton: Princeton University Press). It came out inGerman in the summer of 2011 under the title Ulbrichts Mauer: Wie die SED Moskaus Widerstandgegen den Mauerbau brach and stirred some fresh debate. Otherwise new and gripping, but not quiteas groundbreaking, was Frederick Kempe’s book, Berlin 1961: Kennedy, Khrushchev and the MostDangerous Place on Earth (New York: Putnam, 2011), which appeared simultaneously in German andEnglish.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [U

nive

rsity

of M

ichi

gan]

at 0

7:31

06

May

201

2

96 THE GERMANIC REVIEW ! VOLUME 87, NUMBER 1 / 2012

these over one thousand horizontal photographs provided in their entirety a nearly completevisual documentation of the twenty-seven miles of the inner-city border between Pankow inthe north and Treptow in the south. One could speculate that the soldiers were assigned todocument the poor state of the border to West Berlin, which in places consisted of a hodge-podge of materials. This was done in preparation for the “renovation” and reinforcement workcarried out in the late 1960s. The negatives, however, were never enlarged and never used forthe envisioned purpose. They were forgotten for over forty years until photographer ArwedMessmer combined the photos digitally to produce the three hundred panoramas shown in theexhibit. Annett Groschner supplied the panoramas with captions that were excerpted fromborder patrol reports of sentences shouted over from the West to the East. Particularly in theearly years after the building of the wall, there was frequent, often odd, and very one-sidedcommunication taking place across the border. Many West Berlin residents, police officers,students, members of the occupying allied forces, and former East German citizens camenear the wall to voice their views or protest the division. The East German guards, in turn,diligently recorded what they heard and reported it officially. What was heard over the wallranged from the bizarre to the political, to the provocative and humorous (“Kommt dochruber, wir haben schone Frauen fur euch. Einen Wagen bekommt ihr auch” or “Erschießt denHund dahinten, ich kann nicht schlafen!”). Some sentences were simply attempts at havingan innocent human interaction across the border (“Ist es bei euch so kalt wie bei uns?”).Others hinted at personal tragedies, as in the case with the East German officer in charge ofclearing and leveling the building at 48 Bernauer Street. He spots a woman walking on theWestern side of the street and shouts repeatedly, “Mama!” When ordered by his superior tostop and leave the site immediately, he replies in tears, “Can’t you see this is my mother?”

These “photo-text-panoramas” provide an overview of the everyday occurrences alongthe border. Shot to be viewed by few officials only, without any propagandistic goal in mind,these amazing “landscapes with a wall” document a grim reality, devoid of people, andoverwhelming in their motionless, lifeless status quo. They not only offer an unusual viewfrom the East, but also present a rare perspective on West Berlin, which in these photographsappears grey, desolate, and lacking any glamour whatsoever. Taking these pictures for thespecific assignment, the anonymous photographers were definitely not seeking atmosphericeffects, but a mood of sterile bleakness cutting amidst the living body of the city couldn’thave been conveyed more effectively than that. (See figures 2 and 3.)

Berlin-based artist Simon Menner, too, found material for his exhibit while researchingthe official records of the former GDR. And he, too, has been working with photographsthat were not intended for the eyes of the public. In the exhibit “Images from the SecretStasi Archives,” we find other examples of the artistic power that a picture yields when itis detached from its original intentions and its archival home and is being presented to acontemporary viewer. Sifting through the immense photo documentation completed by oneof the largest secret services organizations in history, Menner had selected and reproducedfor the show a few dozen photographs that unmask the process of surveillance from theperspective of those doing the surveillance. Whenever Stasi agents clandestinely searchedpeople’s homes, they took pictures of the entire apartment, in part to make sure they wouldbe able to put everything back where it belonged before they left. We see snapshots ofunmade beds, desk tops, unfinished breakfasts, coffeemakers, open books, and mugs left on

Dow

nloa

ded

by [U

nive

rsity

of M

ichi

gan]

at 0

7:31

06

May

201

2

GANEVA ! BRIEFLY NOTED 97

FIG

UR

E2.

“Aus

ande

rer

Sich

t.D

iefr

uhe

Ber

liner

Mau

er”:

Ber

naue

rSt

raße

/Ver

sohn

ungs

kirc

he.[

Stre

litze

rSt

rass

e,13

.40

Uhr

]E

inM

ann

tritt

mit

selb

stge

fert

igte

mPl

akat

auf:

“Vol

kska

mm

erab

geor

dnet

e—eh

emal

ige

Nat

iona

lsoz

ialis

ten.

”So

urce

:B

Arc

h-D

VH

60B

ild-G

R33

-06-

031

bis

039,

o.A

ngab

e,R

ekon

stru

ktio

nun

dIn

terp

reta

tion

Arw

edM

essm

er.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [U

nive

rsity

of M

ichi

gan]

at 0

7:31

06

May

201

2

98 THE GERMANIC REVIEW ! VOLUME 87, NUMBER 1 / 2012

FIG

UR

E3.

“Aus

ande

rer

Sich

t.D

iefr

uhe

Ber

liner

Mau

er”:

Cla

ra-Z

etki

n-St

raße

/Ebe

rtst

raße

.[C

lara

-Zet

kin-

Stra

ße,9

.00

Uhr

]E

inW

estb

erlin

erPo

lizis

t:“I

stes

bei

euch

soka

ltw

iebe

iuns

?”So

urce

:B

Arc

h-D

VH

60B

ild-G

R35

-10-

020

bis

026,

BA

rch-

DV

H60

Bild

-GR

35-0

9-06

9bi

s07

3,o.

Ang

abe,

Rek

onst

rukt

ion

und

Inte

rpre

tatio

nA

rwed

Mes

smer

.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [U

nive

rsity

of M

ichi

gan]

at 0

7:31

06

May

201

2

GANEVA ! BRIEFLY NOTED 99

the window sill, and these pictures were all carefully stored in the Stasi archives. At firstsight, these snapshots seem ludicrous or even amusing. At the same time, they are troubling,because they document the repressive measures taken by a totalitarian state in order to reignin terror over its people. The banality of these images makes the horror even more poignant.They seem to be open to just about any interpretation and, thus, could be easily exploitedas tools for repression by agents, if they decided to do so. Take, for example, the photo ofa Siemens coffeemaker. The brand name itself may serve as evidence of contacts to WestGerman agents, although it may simply have been a gift from a relative. A simple photo ofan object, depending on the interpretation it was given, could land someone in prison.

Perhaps the most symbolic for the simultaneous power and absurdity of surveillancein the divided city are some photos Menner found that Stasi spies made of other spiesphotographing them. Small units among the Allied powers were allowed to cross the borderfreely between East and West Berlin; these were called Military Liaison Missions (MLM).Both sides considered these missions an ideal opportunity to spy on each other. Wheneversuch a unit visited the East, the Stasi did their best to observe them while the MLM itselfwas observing and photographing. That’s exactly what we see in these photos: an endlesscircle of reciprocal awareness and mutual surveillance—in the artist’s view, an image thatperfectly captures the spirit of the cold war. (See figure 4.)

The visual allure of the West symbolized by Anglo-American–produced newsreelsand Hollywood movies was captured in a small, but fascinating show, “Berliner Grenzkinos1950–1961.” This is yet another intriguing project involving archival research and visualdocumentation of the emerging split between the East and the West in the course of the 1950s.

FIGURE 4. Simon Menner, “Spione fotografieren Spione fotografieren Spione” (MfS-HA-VIII-Fo-0423-23).Printed by permission from Simon Menner.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [U

nive

rsity

of M

ichi

gan]

at 0

7:31

06

May

201

2

100 THE GERMANIC REVIEW ! VOLUME 87, NUMBER 1 / 2012

It encompassed a month-long film series in the only still-standing, former border cinema inKreuzberg, Lido, and an accompanying exhibit of photos, posters, and documentary materialin a small nearby gallery called Zero. A group of enthusiastic cultural historians uncovereda relatively unknown chapter of German film history as they researched the sites of aboutthirty border cinemas on the Western side near the sector border that were offering almostaround-the-clock Hollywood movies to visitors from East Berlin at a subsidized price (before13 August 1961, Berliners still moved freely across the sectors’ border). The idea for such aninstitution, which could exist only in a divided city such as Berlin, came from the Americanofficer Oscar Martay, who was associated with the HICOG (Office of the High Commissionerfor Germany) and in charge of all film-related issues in West Berlin, and the entrepreneurialowner of two movie theaters, Wilhelm Foss. Although the films shown in the border theatersare hardly of memorable quality, the practices surrounding moviegoing in West Berlin andthe fierce discussions in the press from that period sketch out a little known chapter in Berlinfilm history in which political and aesthetic dimensions, specific modes of public exhibition,and intimate private experiences interconnect in a unique way.

The most intriguing piece of visual remembrance, in my view, was presented by thedocumentary film Bis an die Grenze. Der private Blick auf die Mauer, which premiered to asold-out audience in Urania on the eve of the official commemorative event and then playeda few times at public events during the weekend of festivities. A year ago, two Kiel-basedfilmmakers, Gerald Grote and Claus Oppermann, set out to collect home movies that had todo with the Berlin Wall filmed on 8 mm or Super 8 cameras. Usually, such type of film stockis used to document primarily private events—weddings and birthdays—but the filmmakerswere curious to find out whether and how it had been employed in the filming of “sociallyrelevant” events. They announced their intention in Der Tagesspiegel about a year earlier, in2010, and received about one hundred responses from eyewitnesses, both in the West and theEast, in some cases even from representatives of the occupying forces, a total of fifty hoursof film. The resulting documentary consists entirely of privately filmed material that had notbeen screened publicly before the film’s premier. Not that the scenes filmed contain motifsthat are entirely unfamiliar. We know already of people waving handkerchiefs at relativesacross the wall and others sliding down on ropes from windows to jump into the nets ofthe West Berlin firefighters. But these scenes convey a certain freshness and immediacy asthey are accompanied by the commentaries of the people who actually filmed them, regularBerliners, who recall their experiences of both witnessing historic events as parts of theireveryday life and filming it on a Super 8 camera.4 (See figure 5.)

Bis an die Grenze weaves together three themes. One is concerned with the “bigpicture” and spans the wide arch of postwar history in Berlin from the end of the battle forBerlin in May 1945 to the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. That story is told by a voice-overnarrator and proceeds in a strict chronological order. The other two intertwined themes areactually the more exciting ones. Although its presentation of the history of the Berlin Wall isinteresting, this documentary dwells with some delight on the thrill of filmmaking as a hobby

4I am grateful to the filmmakers Gerald Grote and Claus Oppermann for their interview and for providingme with the background information.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [U

nive

rsity

of M

ichi

gan]

at 0

7:31

06

May

201

2

GANEVA ! BRIEFLY NOTED 101

FIGURE 5. Still from Bis an die Grenze. Printed by permission from Gerald Grote and Claus Oppermann.

and the sheer adventurousness and guts of Berliners to show up at the most dangerous places,to trick interrogating policemen and border guards, and to point their cameras at what theydeemed important. These men and women, now in their seventies and eighties, who providethe commentary to what they had filmed, were no professional reporters dispatched by newsorganizations, but regular Berliners driven by curiosity and an experimentation spirit; mostof them were from the West, with regular professions such as teachers and car mechanics,but there were some from the East, working for the border forces, who obtained permissionto carry a camera along their shifts so that they could practice their hobby. In the end, Bisand die Grenze tells not so much the story of the Berlin Wall but a Berlin story, capturedprimarily in the ordinary human experiences, conveyed through the lens of the private camera,and commented on in unadorned and unpretentious language, mostly in Berlin dialect. Toa certain extent, this can be said of the entire spirit of 2011’s commemorations. Framingmost of the events was an intent to uncover what the Berlin Wall, its prehistory, building,existence, and fall meant mainly in human terms, viewed, for a change, from below, bothfrom the East and West, through the eyes not of politicians and historians, but regularBerliners.

Miami University of Ohio

Dow

nloa

ded

by [U

nive

rsity

of M

ichi

gan]

at 0

7:31

06

May

201

2

102 THE GERMANIC REVIEW ! VOLUME 87, NUMBER 1 / 2012

EXHIBITS AND EVENTS REVIEWED

Aus anderer Sicht. Die fruhe Berliner Mauer (“The Other View: The Early Berlin Wall”).Exhibition, Unter den Linden 40, 6 August to 3 October 2011.

Bis an die Grenze. Der private Blick auf die Mauer. (“To the Border. The Private View ofthe Wall”). Dir. Gergard Grote and Claus Oppermann, 75 min., 2011.

Flimmern auf dem Eisernen Vorhang. Berliner Grenzkinos 1950–1961 (“The Iron Curtainas a Silver Screen: Berlin’s Border Cinemas 1950–1961”). Exhibition and film series,Gallery Zero und Kino Arsenal, 12 August to 12 September 2011.

Der geteilte Bahnhof 1961–1989. Exhibition in the Friedrichstraße train station, 5 to 15August 2011.

Grenz- und Geisterbahnhofe im geteilten Berlin (“Border Stations and Ghost Stations inDivided Berlin”). Exhibition in the Nordbahnhof S-Bahn Station (permanent).

Hinter der Mauer. Glienicke, Ort der deutschen Teilung (“Behind the Wall. Glienicke, aPlace of the German Division”). Exhibition, Schloss Glienicke, Orangerie, 19 June to3 October 2011.

Simon Menner – Bilder aus den geheimen Archiven der Stasi (“Simon Menner – Imagesfrom the Secret STASI Archives”). Exhibition, Morgen Contemporary Gallery, 23June to 31 August 2011.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [U

nive

rsity

of M

ichi

gan]

at 0

7:31

06

May

201

2