Intention to e-collaborate: propagation of research propositions

Ballot Propositions and Information Costs: Direct Democracy and the Fatigued Voter"

-

Upload

ucriverside -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of Ballot Propositions and Information Costs: Direct Democracy and the Fatigued Voter"

http://prq.sagepub.com/Political Research Quarterly

http://prq.sagepub.com/content/45/2/559The online version of this article can be found at:

DOI: 10.1177/106591299204500216

1992 45: 559Political Research QuarterlyShaun Bowler, Todd Donovan and Trudi Happ

Fatigued VoterBallot Propositions and Information Costs: Direct Democracy and the

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

On behalf of:

The University of Utah

Western Political Science Association

can be found at:Political Research QuarterlyAdditional services and information for

http://prq.sagepub.com/cgi/alertsEmail Alerts:

http://prq.sagepub.com/subscriptionsSubscriptions:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.navReprints:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.navPermissions:

http://prq.sagepub.com/content/45/2/559.refs.htmlCitations: at UNIV OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE on April 21, 2014prq.sagepub.comDownloaded from at UNIV OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE on April 21, 2014prq.sagepub.comDownloaded from

What is This?

- Jun 1, 1992Version of Record >>

at UNIV OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE on April 21, 2014prq.sagepub.comDownloaded from at UNIV OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE on April 21, 2014prq.sagepub.comDownloaded from

BALLOT PROPOSITIONS AND INFORMATIONCOSTS: DIRECT DEMOCRACY AND THE

FATIGUED VOTER

SHAUN BOWLER, TODD DONOVAN, AND TRUDI HAPP

University of California, Riverside

any studies have considered the voter’s decision to turn out

m ~ / in terms of a cost benefit analysis:

( 1 ) decision to vote = p(b)-cHere b denotes the benefit from having your .candidate win, p theprobability of your vote deciding the outcome, and c the costs of vot-ing (Downs 1957). By and large this formulation has considered b andc at the systemic level; ease of registration, competitiveness of the elec-tion, literacy requirements and many similar factors have all been

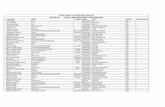

used to assess levels of turnout (Rosenstone and Wolfinger 1978; Powell1980). In terms of this literature, then, c refers to a set of costs imposedon all voters within a given political jurisdiction. Once a voter hasarrived at the voting booth the costs of actually marking a ballotwould seem to be trivial relative to the costs of actually turning out tovote. This last point, however, is not true for all types of ballot. Manyballots require much more of voters than simply turning out andmarking a single preference for one office. Under preferential systemsor where a large number of elective offices and/or propositions are onthe ballot, the decisions facing voters are quite complex. Between1974 and 1988, for example, in addition to a wide range of electiveoffices, Californians faced an average of 13 propositions at each elec-tion. As can be seen from Figure 1, California’s voters express somedissatisfaction with this process. Nearly one-third of voters gave responseswhich suggested that propositions made too many demands upon them.Responses which noted that there were too many propositions or thatthey were too confusing (i.e., that too many demands were beingmade) far outweighed responses which expressed a lack of faith in theefficacy of the proposition process (e.g. that special interests dominatethe process). The question here is whether we can represent such

Received: August 23, 1990Revision Received: February 19, 1991Accepted for Publication: February 20, 1991

at UNIV OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE on April 21, 2014prq.sagepub.comDownloaded from

560

responses more formally. Our answer is that we can, and we begin byconsidering the decision costs facing voters after they have turned outto vote.

FIGURE 1 z

WHAT Is BAD ABOUT STATEWIDE BALLOT PROPOSITION ELECTIONS?

Ballot propositions and information costsWe can recast (1) in order to consider more clearly the costs involved

in completing a ballot:

(2) Number of preferences marked = p(b)-cThis formulation readily lends itself to an expectation of ballot posi-tion effects. Other things being equal, the longer the ballot the moreinformation required for a voter to make all the decisions necessary tocomplete the ballot. Marginal increases in the length of the ballottranslate into additional decisions which increase costs. Voters, then,face an increasing information cost curve as they look down the ballotsorting out which candidate to vote for (or against) and then movingon to examine a list of propositions.

There are a number of ways in which voters may try to minimizethese costs. They could simply not vote on some propositions, espe-cially those further down the ballot. Alternatively voters wishing toreduce information costs might decide to vote &dquo;no&dquo; on every proposi-tion if they prefer the (known) status quo to an (unknown) future. Onepossibility here is that the functional form of the cost curve may not

at UNIV OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE on April 21, 2014prq.sagepub.comDownloaded from

561

simply be linear, but rise much more sharply as the number of prop-ositions mounts (Bain and Hecock 1957: 72-75). In addition to non-linearity, we may also expect a sign change. Research on voting underIreland’s preferential electoral system suggests that the lowest ballotpositions, as well as the highest, may be advantaged. Voters will beginmarking the ballot but tire easily, perhaps skipping several positionsin the middle of the order (Robson and Walsh 1974).

On preferential ballots party labels help reduce costs facing voters.Where ballot propositions are concerned, such labels are not presentand so the decision problem facing voters is that much more difficult,and hence, ballot position effects are more likely (Magleby 1989: 113;Darcy and McAllister 1990: 15). Magleby suggests that the degree ofcontroversy surrounding a given proposition does help voters to sortthrough a ballot and cast a vote for or against a selected list of propo-sitions (Magleby 1989, 1984; Bone 1974; Hahn and Kamieniecki 1987).While this search behavior may not contradict the hypotheses of ballotposition effects it can, at an extreme, be taken to suggest that thereshould be little or no evidence of ballot position effects as voters scanthe ballot for the most controversial propositions. Unless such propo-sitions occupy a similar place in each ballot, it seems unlikely to resultin any general pattern of ballot position effects.

Obviously this argument turns on how one defines &dquo;controversial.&dquo;We will return to this issue below. For the moment, Magleby’s argu-ment highlights the important point that there will be factors associ-ated with individual propositions which will raise or lower the costsassociated with voting.

One factor beyond the ballot itself which should affect voters’ reluc-tance to express a preference is that they simply know nothing aboutthe issues involved. Voters, then, could simply mark the ballot for oragainst propositions that they have heard about (Magleby 1989). Apriori, we can, therefore, expect voters to know more about proposi-tions which have been advertised more fully. While campaign adver-tising may not sway voters to vote for or against a particular proposi-tion, the expenditures themselves may raise the general level of voterawareness. Alternatively spending may reflect the especially controver-sial or divisive nature of an issue. Whatever the case, the end resultshould be similar. Advertising will lower the cost of obtaining infor-mation and so lower the cost of finishing the ballot by exposing votersto an issue prior to their entering the booth. Expenditure should,therefore, increase the vote on a given proposition.

at UNIV OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE on April 21, 2014prq.sagepub.comDownloaded from

562

One of the disadvantages to studying these effects for elective officesis that voters may simply not care who fills some offices. Drop-off forelective ofhces, then, may relate more to the fact that it may be an

election for dog catcher rather than the fact that the dog catcher’sofBce appears low on the ballot. Separating out these two effects is, ofcourse, very difficult. While one may argue that propositions do notcarry with them the same sort of inherent inequality as elective officesit is possible to argue that we should see voters pay more attention tocertain types of propositions (Bone 1974; Cronin 1989). There areseveral possible kinds of effects we might see.

General levels of information may be raised by the manner inwhich the proposition reached the ballot. Initiative propositions demandgreat and sustained attention on the part of activists. For an initiativemeasure to reach the California ballot it must be signed by a numberof registered voters equal to, or greater than, 5 percent of the vote castfor Governor in the previous election. Clearly, a sizable number ofvoters have come in contact with the initiative prior to seeing the prop-osition on the ballot. Perhaps the voter worked for a campaign, hadfriends or co-workers involved in a campaign, or simply signed (orrefused to sign) the petition at the store. In any event, the voter’s gen-eral level of awareness should be raised, especially relative to thoseissues placed on the ballot by the legislature.

While there are exceptions, it is generally the case in Californiathat bond propositions appear first followed by constitutional amend-ments and then initiative measures (Section 10218 of the ElectionCode of California). Despite their position lower down the ballot weexpect initiative measures to experience less drop-off for the reasonsjust outlined. Bond issues are also unlikely to see much drop-off. Notonly do they appear at the top of the ballot they also concern pocket-book issues. The large literature on popularity functions and econom-ics readily lends itself to the idea that voters should be more sensitiveto issues of money than many other kinds of issues (e.g., Lanoue1988; Alt and Chrystal 1985). In controlling for proposition type,then, we also control for systematic differences in ballot position.

Constitutional issues offer two competing expectations. While manycontroversial issues appear via initiatives some may appear as consti-

tutional debates. By and large constitutional issues would seem to

involve fairly remote or obscure issues such as government reorgani-zation and hence most likely to see drop-off. We can take Proposition109 from the June 1990 ballot as an example:

at UNIV OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE on April 21, 2014prq.sagepub.comDownloaded from

563

Governor’s Review of Legislation, Legislative Deadlines. Extends Governor’stime to review bills in Governor’s possession after adjournment infirst year of legislative session, except reapportionment measures,from 12 up to an additional 29 days. Statutes subject to referendapetitions filed prior to January 1 take effect January 1 or 91 days fromenactment, whichever is later. Extends, to next working day, 12-dayperiod for Governor to consider bills if 12th day falls on Saturday,Sunday or holiday. Changes in legislative deadline for considerationof bills introduced in first year of legislative session to January 31 ofsecond year.

As a more direct measure of the inherent difficulty of propositionswe can also consider the simple length of the proposition as it appearson the ballot. In line with our discussion of the number of propositions,longer, wordier propositions should - other things being equal - makegreater demands on individual voters than short ones (Magleby 1984).

Finally, we should also consider that the composition of the elec-torate differs according to election and general levels of turnout. Whilepresidential elections may lead more people to vote, they may as awhole comprise a less well-informed electorate than is the case for

primary elections (Campbell et al. 1960). Less interested and less

well-informed voters may well be unwilling to bear the costs of makinga series of decisions. Drop-off may well be generally higher, then, inpresidential elections and/or when turnout is high.

DATA AND METHODS

We test the hypotheses above using voting results on all Californiaballot propositions 1974-1988 (dates set by the availability of spend-ing data). Our dependent variable is the difference between total num-ber of votes cast on a given proposition and the turnout for that elec-tion (expressed as a percentage of turnout). This measure will increaseas drop-off increases to a maximum of 100 when no one who turnedout voted for a given proposition. We test our hypotheses by estimat-ing the following regression equation with a specification that followsequation (2) above (see Appendix A coding of the variables).

(3) Drop-off = -B* Total campaign spending-B* Citizen initiative proposition-B* Bond issue

-B* * Primary election+B * Prop alters the Constitution+B* Location on ballot

at UNIV OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE on April 21, 2014prq.sagepub.comDownloaded from

564

%~

+B * Prolixity of proposition &dquo; ’

+B* Large number of propositions on ballot+B* Presidential election (long ballot)+B* Turnout

+/-B* Time

In order to address the possibility of non-linearity in the relation-ship between ballot position and drop-off we squared the proposition’slocation on the ballot. One slight problem in estimating (3) was thatconstitutional measures are more prolix than others. We therefore esti-mated the effects of prolixity on each proposition type by means ofinteractive variables.

We also consider as a second dependent variable the proportion of&dquo;no&dquo; votes on a given proposition. Above we suggested that simplyvoting down propositions might be taken as one reaction to having tomake a decision. In a very loose sense this is an incumbency effect forpropositions. The incumbent here being the alternative &dquo;no change tothe status quo&dquo; or, in terms of actual voting, a &dquo;no&dquo; vote. We mightexpect, then, to find a positive relationship between ballot positionand the percent of voters marking a &dquo;no&dquo; vote. While this leaves

unchanged most of our independent variables we do have to alter ourconception of spending to take account of the (hypothesized) directioneffects (see Appendix A).

Table 1 presents our results. In column 1 the dependent variableis drop-off, in column 2 it is percent &dquo;no&dquo; vote. Both equations showthat there are ballot position effects in the predicted direction. Whilevoters may mark the very last propositions in greater numbers theyare also likely to mark these propositions &dquo;no&dquo; (column 2). Thus, evenafter controlling for a series of proposition-and election-specific factors,we see significant drop-off effects due to ballot position and, given thequadratic form estimated, this drop-off is especially pronounced towardsthe middle of the ballot. Ballot positions effects, then, are non-linearas voters seem to skip over the middle portion of the ballot.

There are also significant proposition-specific effects. While con-stitutional measures generate higher levels of drop-off, initiative mea-sures generally see significantly less drop-off. Similarly, we find thatcampaign spending (for and against a proposition) also reduces drop-off. Campaign spending against a proposition also increases the &dquo;no&dquo;

vote. As expected from Campbell, we also find that as turnout increasesso does drop-off. In primary elections we should not expect this since,

at UNIV OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE on April 21, 2014prq.sagepub.comDownloaded from

565

at UNIV OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE on April 21, 2014prq.sagepub.comDownloaded from

566

following Campbell, the electorate should be more motivated and

interested in politics.The parameter for the time trend shows that general levels of

drop-off are decreasing over time. Whether we should take this as atestament to the value of direct democracy, or a reflection of generallylower turnout rates, is uncertain.

We have somewhat mixed evidence on a number of our other

hypotheses. Bond issues do not significantly affect drop-off rates. Fur-ther, there does not seem to be any election specific (primary versuspresidential) effect over and above general turnout levels. More puz-zling than these results is that the indicator for prolixity does not per-form consistently. In the first equation, two of the relevant coefficientsare positive and one is significant. The longer initiative measures inparticular see greater drop-off. Curiously, longer constitutional prop-ositions attract more voters than do shorter ones. This is a perverseresult, especially so in the light of the fact that our other hypotheseshave been substantiated.

In general the equation estimating the percent &dquo;no&dquo; vote does not

perform as well in terms of R2. Our measures of complexity are all inthe predicted direction but none is significant. Nevertheless, we do seeevidence here of both ballot position and spending effects...

DISCUSSION: DIRECT DEMOCRACY AND THE FATIGUED VOTER ..

In this paper we have attempted to examine the process by whichvoters approach complex ballots. We have presented a test of the

importance of ballot position from within an explicitly theoretical frame-work and one, moreover, which takes account of election-specific andproposition-specific factors in addition to ballot location. Here we usedas our example voting on propositions in California and our resultsshow that we can account for drop-off and, to a lesser extent, directionof voter choice by using an approach which emphasizes the cost tovoters of making decisions. In voting on propositions, individual voterrationality may not be in the interests of the process as a whole. In theface of a complex ballot, voters will either not mark a preference orvote &dquo;no&dquo; on propositions lower on the ballot. This behavior, whileindividually rational, undermines the idea of giving voters a direct sayin policymaking through the use of ballot propositions. While thesepatterns do not invalidate the idea of using propositions as a means toexercise direct democracy, they do suggest that there are problemswith over use of this process.

at UNIV OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE on April 21, 2014prq.sagepub.comDownloaded from

567

APPENDIX A

The coding of the variables and a note on estimation

ID on ballot = location of prop on ballot ( 1 = first, 2 = second

etc.)ID squared = ID on ballot squared ’

On year = (0,1 ) 1 = Presidential election ’

,

Primary = (0,1 ) 1 = primary election ~

,_ ,

’

..

Bond = (0,1 ) 1 = bond proposition &dquo; ’ : ;

Initiative = (0,1 ) 1 = initiative measure -

Constitutional = (0,1) 1 =constitutional measureLENGTH x ... = length of the ballot proposition as it appears on

ballot in number of lines multiplied by each of therelevant variables

Spending = amount spent in favor of a prop+amount spentagainst it (in $100,000’s)

Spending against = amount spent against a proposition minus amountspent for expressed as a % of total spending.

Bounded by -100 to 100-100 = all the spending was in favour of a prop+ 100 = all the spending was against a proposition

Turnout = % turnouttime = year

Estimation

Here we address two questions of estimation. First the use of OLSin this pooled data set and second the functional form of the relation-ship between ballot position and our dependent variables.

The data set is stacked (sorted) by time and proposition id number(location on the ballot, first on the ballot = 1, second on the ballot =2 and so on). Although this may bring into question the use of OLSwe did not find problems which required an alternative estimationprocedure (Stimson 1985). The OLS results, then, are the appropriateones to report.

Whether or not the relationship between ballot position and &dquo;no&dquo;vote is linear or non-linear is an empirical question. The form reportedhere is the best fit. Only using ID (i.e., a linear relationship) produceda significant relationship in terms of drop-off but not in terms of &dquo;no&dquo;vote. Using ID squared (as a review suggested a &dquo;j&dquo; curve) produced asignificant relationship in neither case.

at UNIV OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE on April 21, 2014prq.sagepub.comDownloaded from

568

REFERENCES

Alt, J., and A. Chrystal. 1985. Political Economics. Berkeley: University ofCalifornia Press.

Bain, H. M., Jr., and D. S. Hecock. 1957. Ballot Position and Voter’s Choice.

Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.Bone, H. A. 1974. "The Initiative in Washington." Washington Public Policy

Notes 2 (October): 257-61.Campbell, A., P. Converse, W. E. Miller, and D. Stokes. 1960. The American

Voter. New York: Wiley.Cronin, T. 1989. Direct Democracy: The Politics of Initiative, Referendum and

Recall. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.Darcy, R., and R. McAllister. 1990. "Ballot Position Effects." Electoral Studies

9 (April): 5-17.Downs, Anthony. 1957. An Economic Theory of Democracy. New York: Harper.Hahn, H., and S. Kamieniecki. 1987. Referendum Voting: Social Status and

Policy Preferences. New York: Greenwood Press.Lanoue, D. J. 1988. From Camelot to the Teflon President: Economics and Presiden-

tial Popularity Since 1960. New York: Greenwood Press.Magleby, D. B. 1984. Direct Legislation: Voting on Ballot Propositions in the United

States. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.—. 1989. "Opinion Formation and Opinion Change in Ballot Proposition

Campaigns." In M. Margolis and G. Mauser, eds., Manipulating PublicOpinion. Belmont, CA: Brooks Cole.

Powell, G. B. 1980. "Voting Participation in Thirty Democracies: Effects ofSocioeconomic, Legal and Partisan Environments." In R. Rose, ed.,Party and Electoral Systems. London: Sage.

Robson, C., and B. Walsh. 1974. "The Importance of Positional Voting Biasin the Irish General Election of 1973." Political Studies.

Rosenstone, S., and R. Wolfinger. 1978. "The Effect of Registration Laws onVoter Turnout." American Political Science Review 72: 22-45.

Stimson, J. A. 1985. "Regression in Space and Time: A Statistical Essay."American Journal of Political Science 29 (4): 914-47.