Baldvin’s Tear. The Materiality of the Past

Transcript of Baldvin’s Tear. The Materiality of the Past

Making Sense, Cra!ing History : Practices of Producing Historical Meaning / edited by Izabella Agárdi, Berteke Waaldijk, Carla Salvaterra. - Pisa : Plus-Pisa University Press, c2010("ematic Work Group. 4. Work, Gender and Society ; 5)

907.2 (21.)1. Storiogra#a - Metodo I. Agárdi, Izabella II. Waaldijk, Berteke III. Salvaterra, Carla

CIP a cura del Sistema bibliotecario dell’Università di Pisa

"is volume is published thanks to the support of the Directorate General for Research of the European Commission, by the Sixth Framework Network of Excellence CLIOHRES.net under the contract CIT3-CT-2005-006164."e volume is solely the responsibility of the Network and the authors; the European Community cannot be held responsible for its contents or for any use which may be made of it.

Co!er: Federico di Montefeltro’s Study, Open Cabinet with books (1473-1474), inlaid wood, Ducal Palace, Urbino.© 1990 PhotoScala, Florence. Courtesy of the Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali.

© 2010 CLIOHRES.net"e materials published as part of the CLIOHRES Project are the property of the CLIOHRES.net Consortium. "ey are available for study and use, provided that the source is clearly [email protected] - www.cliohres.net

Published by Edizioni Plus – Pisa University PressLungarno Pacinotti, 4356126 PisaTel. 050 2212056 – Fax 050 [email protected] - Section “Biblioteca”

Member of

ISBN: 978-88-8492-736-1

Linguistic revisionRalph Nisbet

Informatic editingR$zvan Adrian Marinescu

Editing assistanceViktoriya Kolp

Baldvin’s Tear. The Materiality of the Past

E!"# H$"%# H#""%&!'%&(()!University of Iceland

ABSTRACT

*is chapter deals with the emotional e+ects a tearstain on a letter had upon the author, how she copes with the tear that in a way materialized the past in her hands. *e tear evokes re,ections about scholarly work and how intimate a scholar can/should be to her subject. Furthermore how a scholar deals with emotions from the past as well as her own feelings. In this way the emotional turmoil the tear brought to the surface, which the author compares with Barthes’s punctum in photographs, was turned into scholarly discussion where it is argued that becoming too intimate with your subject does not necessarily mean that your research has come to an end. On the contrary it can be the basis for new questions, new methodology.

Hér er rætt um !au til"nningalegu áhrif sem tár í bré" haf#i á höfund greinarinnar, hvernig hún tekst á vi# tári# sem seg ja má a# ha" hlutgert fortí#ina í höndum hennar. Tári# kveikir vangaveltur um $æ#i og nánd $æ#imannsins vi# vi#fangsefni sitt, hvernig $æ#ima#ur tekst á vi# til"nningar úr fortí#inni og eigin til"nningar. %annig er !eim áhrifum sem tári# haf#i, og höfundur líkir vi# punctum Roland Barthes, snúi# upp í $æ#ilega umræ#u !ar sem !ví er haldi# $am a# !a# a# nálgast vi#fangsefni sitt um of til"nningalega !ur" ekki a# lei#a til skipbrots rannsóknar heldur geti !vert á móti or#i# hvati og undirsta#a n&rra kre'andi spurninga og a#fer#a.

Our point of departure is Copenhagen in May 1829 where a man sits at his desk, writ-ing a letter that will be sent to a vicarage in Iceland via one of the ships that sail to this island in the far north along with goods, passengers and other correspondence every spring and autumn. Its addressee will read it, possibly other persons in the household as well. Some parts may be read aloud even though its subject is a delicate matter. It will be kept in private possession well into the 20th century but eventually -nd its way to an archive where, in the 21st century, I will be among its readers, when trying to con-textualize a woman’s life and a tragic love story in which the signatory is the main actor. *e letter proves to be quite informative, but in the midst of my scholarly work – tak-ing notes, evaluating what is being written, hinted at (or not mentioned at all) – a few words and ink blots bring up unexpected emotions that force me to think about and theorize how to deal with my own emotions towards my subject(s) and the emotions of those long gone. More precisely, how to react when the past seems to materialize in our

Erla Hulda Halldórsdóttir208

hands; when words in an old letter pierce their way into our mind as though they had been written yesterday, or at this very moment. *is chapter illustrates a personal, albeit academic, re,ection on our disposition in pur-suing historical research and writing, how we explore, interpret and represent particu-lar sources, subjects – the past.

THE COMPLICATED PAST

Since the early 1990s I have used private letters in my research on women’s lives and ex-periences in 19th-century Iceland and been concerned with how we read and interpret private letters from people past, how to read and write about their lives1. *is is certain-ly not restricted to private letters but has to do with the nature of the discipline itself, how the past becomes history. To some extent, this has been a personal struggle with the claims of objective history (or should we call them truth-claims?) and an attempt to work out the emotions that are inevitably evoked when one uses personal sources, when a life that was lived in the past becomes a part of one’s own emotional life. *us I have asked myself when exploring the lives of 19th-century women in Iceland if I am transferring my perspective and feelings onto my subjects and I have been worried that the line between the scholar (me) and the past (‘my’ women) has become blurred2. Most historians acknowledge that history “does not, of course, present itself to us in ready-made narrative forms complete with explanations for social change” as the Brit-ish historian Sue Morgan has formulated so nicely3. History is interpretation and rep-resentation by us historians, “a corpus of narrative discourses about the once reality” to quote Alun Munslow; the past however “is what once was, is no more and has gone for good”4. Munslow thus emphasises the interpretational factor in historical research and writing. What we have in our hands is not “reality” but traces of past lives with di+erent experiences, diverse perspectives that we try to contextualise in order to make sense of the past – and consequently the now.Historian Klaartje Schrijvers writes in her chapter on some striking photos of executed Second World War French maquis: “just as the presumed existence of pure objectivity in history is a myth, so is history without emotions as well”5. I could not agree more. In history itself there are emotions and history evokes emotions. I doubt whether there is a historian who can sincerely deny having felt emotional every now and then when exploring his or her sources, when visiting historical sites or just gazing at a landscape where there seems to be nothing to see except landscape – but in the landscape itself, and beneath its surface, there is also history6. Private letters and correspondence of times past do readily evoke emotions, whether it is compassion, disgust, surprise or pleasure. It is easy to be deceived by those personal accounts and “take [them] for granted” as D.A. Gerber has pointed out7. We may even imagine that we have reached the heart and soul of our subject – seeing things with his

Baldvin’s Tear. The Materiality of the Past 209

Of Sources

or her perspective, understanding their thoughts. *is would be a delusion as private letters are seldom if ever the innocent source we might be tempted to think they are. Private letters do always re,ect the context of the relationship of the signatory and the addressee; there are gaps in correspondence; o.en only one side of it has been pre-served; there are lies, secrets and silences. I have touched upon those issues in my earlier writing motivated by, say, Liz Stanley’s theorizing on correspondence, interpretation and scholarly work that has helped me work out and contextualize the complications of past lives and di+erent levels of self-representation in private letters8. What I am stressing here is the fact that I have considered myself quite well prepared for facing the challenges of private letters and the emotional e+ects they might possibly have.Now, let us turn back to Copenhagen in May 1829, to the letter that kindled those re,ections.

SETTING THE SCENE

*e exact day was 18 May and the man’s name was Baldvin Einarsson (b. 1801), one of Iceland’s most prominent intellectuals and political -gures in the late 1820s and early 1830s. Einarsson had le. Iceland for Copenhagen in 1826 in order to study law at the University of Copenhagen. When he le. Iceland he was engaged to marry Kristrún Jónsdóttir (b. 1806) and both had, without success, sought for permission for her to sail with him to Copenhagen. *at was, needless to say, considered inappropriate. Icelan-dic women rarely travelled abroad at this time (and their mobility in general was very limited). Engaged women could only wait at home, write letters to their -ancés, express their love, and hope that one day they would return home9. *is is what Jónsdóttir did.Copenhagen was the capital of Iceland, which at that time was a province in the Danish monarchy, and it was there that Icelandic university students (male) sought education, wisdom and culture which they mediated (usually) back home to Iceland. Some of the students got drunk and drowned in the canals of Copenhagen. Some went deliberately into the canals, others slipped. Einarsson himself died tragically. In December 1832 his bed linen caught -re from a candle, he managed to put out the -re but his hands and feet were so badly injured that he died in February 1833, only 32 years old, then considered one of Iceland’s most talented “sons”. “Everything becomes a weapon for Iceland’s mis-ery…”, uttered one of his friends in a desperate attempt to compose a eulogy10. *ese words are frequently quoted when the country and its people seem to be in a dire situation.What happened between Einarsson’s departure from Iceland in 1826 to his death in 1833 is a long and complicated story. *e main facts are that Einarsson cheated on his -ancée in Iceland; became enchanted by the beauty of a Danish woman, had a child by her and eventually married. *is he concealed from Jónsdóttir and her family as long as he could. However, both before and a.er his marriage, a.er his deception became known and he admitted his wrongdoings, he continued to write Jónsdóttir a+ectionate

Erla Hulda Halldórsdóttir210

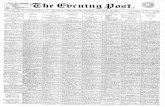

Fig. 1This portrait of Baldvin Einarsson was made in 1829-1831. Apart from his being untiring spokesman for reforms in Iceland, many of his letters reflect a sensitive and romantic man who was easily charmed by the beauty of nature – and women.Source: National and University Library, Reykjavík.Photo: Helgi Bragason.

Baldvin’s Tear. The Materiality of the Past 211

Of Sources

love letters, in which he sent kisses, embraces and promises of eternal love. Jónsdóttir seems to have played along, to some degree at least, but as her letters have not been preserved her voice is only heard as an echo, re,ected and represented in Einarsson’s letters, as I have discussed elsewhere11.Einarsson had crossed my path before I read his letters, not only as a well known -g-ure in Icelandic history but also, and more importantly, as a vulnerable person whose betrayal and tragic death seems to have caused his -ancée’s lifelong illness (probably depression) that in turn a+ected the life and prospects of one 19th-century woman I was researching12. With my mind set on women of the past I wrote and produced historical radio programmes on women, in collaboration with the literary scholar Erna Sverrisdóttir several years ago. Our -rst series was on 19th-century women who waited (for years) in Iceland engaged to marry while their -ancés studied abroad13. Jónsdót-tir was one of the women “waiting” and her story de-nitely the most impressive. *is was my -rst serious reading of Einarsson’s love letters. Since then I have nurtured the dream of publishing the letters with an epilogue where I would “-ll in the gaps” of their correspondence and re,ect on how to interpret and represent the past – history. *is has meant reading the letters again, other correspondences and individual letters, and writings about the life and death of Einarsson as well as Jónsdóttir. I have discussed their correspondence and relationship in lectures, and a chapter in the -rst issue of “Life Writing” (2010), is concerned with textual analysis and the silences in the corre-spondence14. *e present chapter, as already stated, is my personal re,ection on sources, emotions and the scholar in her research.When -rst reading Einarsson’s love letters, written before and a.er his betrayal, I could not help but feel anger towards him – my heart beating with the betrayed -ancée. At the same time I felt empathy; the beauty of his words, his rhetoric and his love enchant-ed me. Should a historian allow herself to feel emotions like this? Can I take sides with one person (and against another one)?

THE TEARS THAT HAVE STAINED THE INK

*e letter Einarsson wrote that day in May 1829 is not addressed to his -ancée but to her father, who was Einarsson’s benefactor and a second father15. Its rhetoric is the discourse of a desperate man who sees no way out of the di/culties he has got himself into. Having read all his preserved letters to Jónsdóttir, knowing how things turned out in the end, having contextualized their correspondence, their relationship, and be-ing aware of the complications of correspondences and letter writing, I had positioned myself as sceptical of his rhetoric and was even ready to believe that his desperation was a lie, a deception16.Einarsson did indeed reveal di+erent identities and rhetorical strategies in his letters. He had for instance written another letter to Jónsdóttir’s father the day before, on 17 May,

Erla Hulda Halldórsdóttir212

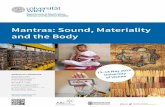

Fig. 2Are those tears? Just above the middle of this sheet Einarsson points out “the tears that have stained the ink” and the spots are clear, both before and after his declaration. In fact there are spots, that might be tears, on all the four sheets of his letter.Source: Manuscript Department, National and University Library, Reykjavík.Photo: Helgi Bragason

Baldvin’s Tear. The Materiality of the Past 213

Of Sources

where he mentioned his dishonesty in passing, before going into the issues the two men usually discussed: the publication of journals, reforms in Iceland, the kings of Europe, wars and sometimes some amusing inventions. *is businesslike (or manly!) writing did not -t with the repetitive sorrowful tone in the second letter, the exalted words on death and eternal love beyond this earthly life, not to mention Einarsson’s remark that he and his -ancée were better dead and buried together under the cover of green grass where they would embrace and kiss with their cold lips in timeless love and eternity. *is was surely a literary experiment in,uenced by Romanticism rather than sincere regret or ex-pression of love to his -ancée. I could not help but feel cynical towards his words and wrote some notes on romantic expression and exalted despair, and remarked that Einars-son was clearly calling for empathy. But then, suddenly, my thinking was disrupted:

Oh! Beloved father! Why should I talk at length about this any more, you might think this is fraud, yet no you are not so cruel, the tears that have stained the ink in the letter, the tears that have not dried while I have been writing you …

Is that a tearstain? *e letter is creased since it was written 180 years ago, but the blot-ted ink is clearly visible as are other spots that might be tears as well. My heart beat faster as I put my -nger on the tear. *e past seemed almost tangible, the tear promi-nent on this old paper, a kind of materialized Einarsson. All of a sudden I did not know how to deal with the letter or with Einarsson, who with his unruly hair, high forehead, in tailored jacket with white neckwear, had become too present.

READING A TEAR AND STUDIES

As I regained my composure and wondered why this tear (or alleged tear) a+ected me in such a way, Roland Barthes’s theories on the studium and punctum of photographs came to my mind. According to Barthes, Studium is grounded in cultural and historical interest and knowledge but Punctum has emotional impact. Reading a photo out of cul-tural and historical interest is done with knowledge or skill the spectator has acquired, “polite interest” Barthes calls it, but the photo itself does not touch the observer in any particular way. Emotional e+ects are di+erent; something evokes interest; disturbs, interrupts; grabs the spectator who becomes emotionally moved17. I had already used Barthes’s theories to read and analyse a photo of Iceland’s most famous couple engaged to be married18 and that, as well as my being in,uenced by Liz Stanley’s writing on the resemblance between a photo and a letter, may well be the reason why I experienced Ei-narsson’s tear like a punctum in a photo. *e tear a+ected me emotionally; it disrupted my analysis, the cultural and personal context I was reading this letter in. *e tear dis-concerted me, ruptured my thoughts as a source that would not be controlled or reveal what I expected to see or even wanted to see.Liz Stanley has argued that letters “share some of the temporal complexities of photo-graphs”. Letters are always in the present tense, Stanley points out; their content and

Erla Hulda Halldórsdóttir214

how it is represented is coherent with the here and now of the signatory. Letters thus have a “‘,ies in amber’ quality” and will never be anything else than a slice from time, a snapshot of that precise moment19. Einarsson’s letter is no exception. It is written at a speci-c moment in a certain context and portrays -rst and foremost his feelings at that moment. It goes without saying that the letter and its content was also intended to a+ect the addressee and as I have discussed elsewhere, one may argue that Einars-son’s intention was to construct Jónsdóttir’s identity (as well as strengthening his own) through their correspondence. She was his “signi-cant other”, as Gerber has argued was o.en the case in immigrant correspondences. Jónsdóttir was the person to whom Einarsson turned in order to con-rm and re-establish his old self-understanding and identity in his new Copenhagen life20.What, then, is the meaning of an old letter, once wet with tears, that upsets the proc-ess, the coherence the scholar has already set down before her? Why did the tear have such an impact when the letter itself might actually be thought of as the embodiment of the signatory, in addition to the fact that I had already read quite a lot of Einarsson’s letters, many of which were full of tearful narration? *ere is no simple answer, only a few suggestions.First of all, it seems clear that I was so busy contextualising Einarsson’s writing and try-ing to see through his words (and not being swept away by his smooth tongue) that it made me too focused on holding his emotions at bay, and mine as well. I did not want to become sentimental or subjective in my analysis and writing and therefore directed all my thinking on the wider context of the letter instead of its inner rhetoric and the “here and now” it re,ected (or “then and there” seen from my space and place).While mulling over “the tear” I came across Jill Lepore’s excellent article on the risk of becoming too involved with the person you are investigating. Lepore, a historian and biographer, describes sarcastically the sensation she felt when -nding a lock of hair of her 19th-century subject and how, there in the archives, she stroked the hair, feeling awkward yet in “an eerie intimacy with Noah [Webster]”. And she did not even like him21. Lepore set out seeking an answer to the question if micro-historians could o+er new solutions for biographers who, according to Lepore, are “notorious for falling in and out of love with the people they write about”22. I will not enter the vast -eld of bio-graphical literature but draw attention to Lepore’s discussion on the di/culty of -nd-ing the balance between “intimacy” and “being inquisitive to the point of invasiveness” when exploring a private life. Lepore argues that there is “a major danger” of becoming too close to our subject but also points out that we might equally not come to “know her well enough”23. What we need to ask then is how to -nd the balance, the line be-tween being too intimate and the ideal of an objective scholar. I want to argue that it is impossible to know where the line is drawn until we have already crossed it. And that it may even be necessary to cross the line to understand the possibilities and limits of both our interpretation and the material we are working with.

Baldvin’s Tear. The Materiality of the Past 215

Of Sources

*ere are more questions to ask. For instance, what do we mean exactly when we talk about being too close to or too intimate with our subject? To me it seems that there are at least two (but related and sometimes overlapping) levels here. First, it is the question of identifying with our subject (speaking for myself I might easily identify with some of ‘my’ 19th-century women, especially women concerned with women’s education and women’s rights). Second is the kind of intimacy that follows the very personal informa-tion we o.en -nd in private letters. Information that gives us the feeling of knowing too much, even things that we do not want to know. Years ago I heard a historian describe the inner con,icts she experienced when trying to decide how deep into the most in-timate sphere of her subject’s life (a remarkable 19th-century woman) she should go. In the end, she said that she had peeped through the keyhole of the bedroom door but not under the duvet. And then of course it is entirely up to us historians how we use the information, the little secrets and lies we may -nd. We might add the third level; the one where we fall so blindly in love with our subject that we are unable to read, think and analyse critically and end up with biased narrative. Crossing the line does not necessarily mean there is no turning back. It can simply mean that we have been challenged with something unexpected and even uncomfortable: an unexpected document or feelings such as empathy or dislike that force us to revise our analytical tools and ask new questions. And this is how it should be. Dominick LaC-apra wrote in 1985 that historians were too o.en preoccupied with looking for new material instead of re-interpreting the old, reading it from a new perspective and engag-ing in dialogue with the past24. Crossing the line (if we realize we have crossed the line, which I assume we do!) calls for new perspective and can therefore be stimulating and constructive (not always easy though). It is also important to remember that “crossing the line” has, in my view, not only to do with being too intimate. Historians can go in the other direction, blinded by the delusion that the more distance between them and their subject, the better the history they are writing. *e danger of too much distance and coldness towards our subject(s) is that it leaves limited space for emotions (neither ours nor our subject’s) or di+erent perspectives. All historians know the problems that arise when reading, analysing and interpreting their material. And most historians acknowledge that our interpretation not only de-pends on what we see and read in documents, letters or photographs, what we think we see or do not see, but also on what we know already, the knowledge that is embed-ded in our culture and history, in addition to our personal disposition and perspective. Writing about where we are epistemologically situated has however not been the core of most historians’ work and the o.en dramatic process of our research and writing too seldom -nds its way into our writing. *e sociologist Liz Stanley has theorised on this and argued that the “noise” of producing knowledge, the heavy work in the archive, should be within the frame of history writing25. I totally agree and argue that it is inspir-ing to face our interpretational problems openly by writing about them and to re,ect

Erla Hulda Halldórsdóttir216

on our research process, how we produce knowledge (history). Hence we are better able to sort out our sources, how we relate to our subject.

IN DIALOGUE WITH THE PAST

If I try, then, to theorise the meaning of Baldvin’s tear I would argue that the tear re-minds us that the past is not as it seems; that the image we have intentionally or unin-tentionally constructed in our minds beforehand, and our research questions, are con-stantly changing since unexpected sources or knowledge gets in our way. And even if we do not believe in -xed historical “truth”, we are inclined to represent our -ndings as a kind of “truth-claim” about this particular past or person. *e tear that unbalanced my mind, when I was perhaps trying too hard not to be carried away by discourse and emo-tions of the past, might well be considered a shout from the past, a reminder of talking with the past, or, to refer to Natalie Zemon Davis’s vision in History’s Two Bodies, that History may have “at least two bodies in it, at least two persons talking, arguing, always listening to the other”26. *e tear is Barthes’s punctum in the middle of my studium. I was not listening to Einarsson, not talking to him, but positioning him according to all the knowledge I had gathered about him, the society he lived in, the literature that might in,uence his writing in correspondences.*e tear reminds me that there were real human beings in the past, individuals made of ,esh and blood, whom we need to respect and study in their right temporal context. *ey were persons who experienced pleasure and sadness, and were full of paradoxes just as we are today. *e tear is corporal, it is a vessel, it is something alive (no matter if it dried long ago!) And no matter if the tear might be a lie and even though crying is one of the characteristics of the romantic man (as Einarsson surely was), the tear did materialize the past in my hands. It brought forward this feeling of the heartbeat of history; that the past has become one with the present and is thus somehow tangible. Or perhaps it was I that had gone into the past and will thus be a part of the history it eventually becomes.

Baldvin’s Tear. The Materiality of the Past 217

Of Sources

NOTES1 E.g. E.H. Halldórsdóttir, Fragments of Lives – (e Use of Private Letters in Historical Research, in

“NORA. Nordic Journal of Women’s Studies”, 2007, 15, 1, pp. 35-49.2 *is was partly addressed in Halldórsdóttir, Fragments of Lives cit., pp. 35-49, at pp. 44-47. *e article

has its origin in a lecture given at the VIII Nordic Women’s and the Gender History Conference in Turku 12-14 August 2005 under the title “Am I she?” which is more accurate for the problems ad-dressed.

3 S. Morgan, (eorising Feminist History: A thirty-year retrospective, in the “Women’s History Review”, 2009, 18, 3, p. 382.

4 A. Munslow, Narrative and History, Basingstoke 2007, p. 9.5 K. Schrijvers, La Douleur est Physique, in A. Petö, K. Schrijvers (eds.), Faces of Death, Pisa 2009, p. 1.6 S.L. Gilman, Alan chohen’s surfaces of history, in I.A. Cohen, On European Ground, Chicago 2001, pp.

1-10. 7 D.A. Gerber, Acts of Deceiving and Withholding in Immigrant Letters: Personal Identity and Self-Presen-

tation in Personal Correspondence, in “*e Journal of Social History”, 2005, 39, 2, p. 315.8 Halldórsdóttir, Fragments of Lives cit.; Id., (e Narrative of Silence, in “Life Writing”, vol. 1, April 2010

(forthcoming); among Stanley’s work see L. Stanley, (e Epistolarium: on theorizing letters and cor-respondences, in “Auto/Biography”, 2004, 12, pp. 201-35; Id., Mimesis, metaphor and representation: holding out an Olive branch to the emergent Schreiner canon, in the “Women’s History Review”, 2001, 10, 1, pp. 27-50; D.A. Gerber, Acts of Deceiving and Withholding in Immigrant Letters, and Id., Epis-tolary Ethics: Personal Correspondence and the Culture of Emigration in the Nineteenth Century, in the “Journal of American Ethnic History”, (2000), 19, 4, pp. 3-23.

9 E.H. Halldórsdóttir, E. Sverrisdóttir, Hjarta# mitt besta. Af tveimur ástarbréfum, in “Ársrit Sögufélags Ís-r0inga”, 2002, 42, pp. 81-101.

10 *is is my literal translation. *e poet, Bjarni *orarensen was unable to compose anything but the -rst verse: “Ísalands / óhaming ju/ ver#ur allt a# )opni! / eldur úr i#rum !ess, / ár úr 'öllum / brei#um byg-g#um ey#a!”. Literally in English: “Everything becomes a weapon for Iceland’s misery! Fire from within, rivers from mountains, destroy populated areas”.

11 For English writing on this topic see E.H. Halldórsdóttir, (e Narrative of Silence, in “Life Writing”, 2010, 7, 1, pp. 1-14. *e article deals with Jónsdóttir’s silence, as her letters to Einarsson have not been preserved.

12 Halldórsdóttir, Fragments of Lives cit.; Id., Private letters, in A. Petö, B. Waaldijk (eds.), Teaching with memories: European Women’s Histories in International and Interdisciplinary Classrooms, Galway 2006, pp. 66-74.

13 *e series “Í festum” [“Promised in Marriage”] was produced in collaboration with literary scholar Erna Sverrisdóttir and broadcast on National Broadcasting, Channel 1 in February 2002.

14 *e article in question: E.H. Halldórsdóttir, (e Narrative of Silence. *is particular article is the result of a lecture given at a seminar at the University of Edinburgh in 2007 (Centre for Narrative & Auto / Biographical Studies (NABS)). *e same topic was discussed in a lecture in Iceland in 2008. Lectures on Einarsson’s and Jónsdóttir’s relationship were also given in Iceland 2005 and 2006.

15 *e National Library, Department of Manuscripts: Lbs 4728 4to. A letter from Baldvin Einarsson to Jón Jónsson, 18 May 1829.

16 See Gerber, Acts of Deceiving and Withholding in Immigrant Letters cit., pp. 316-318; Also D. Barton, N. Hall (eds.), Letter Writing as a Social Practice, Amsterdam 2000.

Erla Hulda Halldórsdóttir218

17 R. Barthes, Camera Lucida. Re*ections on Photography, transl. from French by Richard Howard, New York 1982, pp. 26-27.

18 *ese were the national hero Jón Sigur0sson and his -ancée, Ingibjörg Einarsdóttir, who waited (engaged) in Iceland for 12 years while Sigur0sson studied and worked in Copenhagen. A photo of them newly wed in 1845 was my focus of attention. See E.H. Halldórsdóttir, Myndin af Ingibjörgu, in Spunavél handa G.H. 1. febrúar 2006, Reykjavík 2006, pp. 39-46.

19 Stanley, (e Epistolarium cit., p. 208.20 Halldórsdóttir, (e Narrative of Silence cit.; Gerber, Acts of Deceiving and Withholding in Immigrant

Letters cit., pp. 316-318. 21 J. Lepore, Historians Who Lo)e Too Much: Re*ections on Microhistory and Biography, in the “Journal of

American History”, June 2001, p. 129.22 Ibid., p. 133.23 Ibid., p. 129.24 D. LaCapra, History and Criticism, Ithaca - London 1985, pp. 15-44.25 L. Stanley, “Svo sem í skuggsjá, í óljósri mynd”. Túlkunarmöguleikar í lestri á fortí#inni, in “Riti0”, 2006,

3, at pp. 32-33. Also Lesi# í fortí#ina, in “Lesbók Morgunbla0sins”, 13 May 2006, p. 16. [An interview with Liz Stanley].

26 N.Z. Davis, History’s Two Bodies, in “*e American Historical Review”, 1988, 93, 1, p. 30.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Barthes R., Camera Lucida. Re*ections on Photography, transl. from French by Richard Howard, New York, 1982.Barton D., Hall N. (eds.), Letter Writing as a Social Practice, Amsterdam 2000. Davis N.Z., History’s Two Bodies, in “*e American Historical Review”, 1988, 93, 1, p. 15.Gerber D.A., Epistolary Ethics: Personal Correspondence and the Culture of Emigration in the Nineteenth Century, in the “Journal of American Ethnic History”, 19, 4, 2000, pp. 3-23.Id., Acts of Deceiving and Withholding in Immigrant Letters: Personal Identity and Self-Presentation in Per-sonal Correspondence, in the “Journal of Social History”, 2005, 39, 2, pp. 315-330.Gilman S.L., Alan Chohen’s surfaces of history, in Cohen A., On European Ground, Chicago 2001, pp. 1-10. Halldórsdóttir E.H., (e Narrative of Silence, in “Life Writing”, 2010, 7, 1, pp. 1-14. Id., Fragments of Lives – (e Use of Private Letters in Historical Research, in “NORA. Nordic Journal of Women’s Studies”, 2007, 15, 1, pp. 35-49. Id., Private letters, in Petö A., Waaldijk B. (eds.), Teaching with memories: European Women’s Histories in International and Interdisciplinary Classrooms, Galway 2006, pp. 66-74.Id., Myndin af Ingibjörgu [(e Image of Ingibjörg], in Spunavél handa G.H. 1. febrúar 2006, Reykjavík 2006, pp. 39-46.Halldórsdóttir E.H., Sverrisdóttir E., Hjarta# mitt besta. Af tveimur ástarbréfum, in “Ársrit Sögufélags Ís--r0inga”, 2002, 42, pp. 81-101. [My dearest heart. Of two lo)e letters, in “*e Isa1ords Historical Society Yearly”].LaCapra D., History and Criticism, Ithaca - London 1985.Lepore J., Historians Who Lo)e Too Much: Re*ections on Microhistory and Biography, in “*e Journal of American History”, 2001, 88, 1 pp. 129-144.

Baldvin’s Tear. The Materiality of the Past 219

Of Sources

Lesi# í fortí#ina [Reading the Past], in “Morgunbla0i0”, 13 May 2006. [An interview with Prof. Liz Stanley by Erla Hulda Halldórsdóttir].Morgan S., (eorising Feminist History: A thirty-year retrospective, in the “Women’s History Review”, 2009, 18, 3, pp. 381-407.Munslow A., Narrative and History, Basingstoke 2007.Schrijvers K., La Douleur est Physique, in Petö A., Schrijvers K. (eds.), Faces of Death, Pisa 2009, pp. 1-37.Stanley L., “Svo sem í skuggsjá, í óljósri mynd”. Túlkunarmöguleikar í lestri á fortí#inni [‘(rough a glass, darkly’: Interpretational possibilities for reading the past], in “Riti0”, 2006, 3, pp. 7-37. Id., (e Epistolarium: on theorizing letters and correspondences, in “Auto/Biography”, 2004, 12, pp. 201-235.Id., Mimesis, metaphor and representation: holding out an Olive branch to the emergent Schreiner canon, in the “Women’s History Review”, 2001, 10, 1, pp. 27-50.*e Manuscript Department, National and University Library (Lbs), Reykjavík:Lbs 4728 4to. Kristrún Jónsdóttir’s collection of private letters. A letter from Baldvin Einarsson to Jón Jónsson, 18 May 1829.Lbs. 1642 4to. Kristrún Jónsdóttir’s collection of private letters.