The impact of age and shopping experiences art-3A10 1007-2Fs10257-010-0156-y

Art-3A10 1007-2Fs10902-015-9635-7

Transcript of Art-3A10 1007-2Fs10902-015-9635-7

RESEARCH PAPER

When Are People Unhappy? Corruption Experience,Environment, and Life Satisfaction in Mainland China

Yiping Wu1 • Jiangnan Zhu2

� Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 2015

Abstract Previous research on corruption and happiness has typically considered cor-

ruption perception as an indicator of government quality; however, the impact of direct

personal experience of corruption has been largely overlooked. The current research, using

the Asian Barometer Survey I data set on China, fills this gap. We found that the negative

effects of personal experience of corruption on happiness are moderated by the general

corruption environment, as measured by the corruption–victimization rate of a province.

Corruption experience reduces life satisfaction significantly only when the external envi-

ronment has a low level of corruption. We applied concepts from the broken windows

theory to provide theoretical explanations for this phenomenon and used a series of models

to test the robustness of our findings.

Keywords Happiness � Life satisfaction � Corruption experience � Corruptionenvironment � Moderating effect � China

1 Introduction

Scholars have found that government actions can have a major impact on people’s life

satisfaction. In particular, control of corruption, a crucial indicator of the quality of gov-

ernment, has a substantial effect on subjective well-being (Helliwell and Huang 2008;

Samanni and Holmberg 2010). However, how exactly corruption affects people’s

& Jiangnan [email protected]; [email protected]

Yiping [email protected]

1 School of Public Economics and Administration, Shanghai University of Finance and Economics,Shanghai, China

2 Room 933, 9/F, Department of Politics and Public Administration, Faculty of Social Sciences,Centennial Campus, The University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong, Hong Kong

123

J Happiness StudDOI 10.1007/s10902-015-9635-7

happiness remains unclear. Although emphasizing the general corruption environment,

existing literature has largely overlooked the varied effects of corruption experience on

individual happiness in different environments.

To fill this gap, we examined the impact of corruption experience on happiness and the

moderating role of the corruption environment. We used the case of mainland China

because it has achieved impressive improvements in many standard measures of well-

being, such as health, literacy, and poverty reduction, while also experiencing a high level

of corruption. Thus, our findings contribute to the literature on corruption and happiness in

developing and undemocratic countries (Di Tella et al. 2008; Ott 2010; Powdthavee 2005);

by contrast, most related research has focused on the effects of socioeconomic factors on

happiness in advanced and democratic countries (e.g., Alesina et al. 2004; Dehejia et al.

2007; Di Tella et al. 2001; Graafland and Compen 2014; Vendrik and Woltjer 2007). Our

findings will be useful to governments in controlling corruption and improving people’s

subjective well-being.

2 Linking Corruption to Life Satisfaction: Literature Review

Because of the complex and secretive nature of corrupt behavior, no definition of cor-

ruption is completely satisfactory. This research used the popular and legal definition of

corruption, the abuse of public office for private gain in violation of formal rules (Manion

1996; Nye 1967). Research linking corruption to satisfaction is limited because life sat-

isfaction was traditionally not considered a political outcome or politically important. Only

recently have scholars begun examining the impacts of political factors, such as regime

type, government welfare policies, and representation in politics, on happiness (Bok 2010;

Alvarez-Diaz et al. 2010; Di Tella and MacCulloch 2005; Haller and Hadler 2006; Pacek

and Radcliff 2008a, b; Radcliff 2001, 2005).

Following this line of research, more studies have tied corruption to happiness. Most of

them have performed cross-national comparisons by using national-level corruption indi-

ces, such as the Corruption Perception Index and Control of Corruption Index. The studies

treated corruption as a measure of low institutional quality and identified a negative

relationship between corruption and happiness (e.g., Bjørnskov et al. 2008; Helliwell 2006;

Rothstein 2010). For instance, corruption can reduce subjective well-being by generating

physical and economic insecurity through inefficient economic policies, increased crime

rates, and inequality (Montinola and Jackman 2002). It can also undercut aspects of the

democratic process, such as accountability, equality, and government transparency (Tavits

2008). These outcomes may breed feelings of exclusion and alienation, undermining life

satisfaction (Ryan and Deci 2001; Warren 2004).

Thus, relevant literature has mainly explained how the overall corruption environment

can impact indirectly the general life satisfaction of citizens, but has paid scant attention to

how personal experience of corruption can affect directly an individual’s happiness. More

critically, while some research has studied corruption as an economic and political evil

(Doig et al. 2006; Morris 1991; Rose-Ackerman 1999; Seligson 2002), dissenting voices

have argued that, in some cases, corruption may grease the wheels of commerce and

bureaucracy. Corruption may enable individuals to circumvent cumbersome regulations

and correct preexisting government failures, particularly in developing countries, where

institutions are often distorted (Egger and Winner 2005; Huntington 1968; Leff 1964).

These conflicting views suggest that although a corrupt environment may reduce general

Y. Wu, J. Zhu

123

life satisfaction at the macro level, the impact of personal experience of corruption on

happiness at the individual level may be moderated by the preexisting institutional envi-

ronment. Using the case of China, we develop our argument by exploring the channels

through which personal experience of corruption affects happiness and how the corruption

environment may intervene in the process.

3 Corruption Experience, the Corruption Environment, and LifeSatisfaction in China

Despite China’s phenomenal economic performance since economic reform began, several

studies on the country’s subjective well-being have shown a declining or flat line of life

satisfaction in recent decades (Brockmann et al. 2009; Burkholder 2005; Crabtree and Wu

2011; Easterlin et al. 2012; Kahneman and Krueger 2006; Knight and Guantilaka 2011).

Various complaints about social unfairness have arisen in China. Recent surveys show that

40 % of the country’s population is unhappy; 70 % of farmers are dissatisfied; and 60 % of

wealthy people are emigrating or considering doing so (The Wall Street Journal 2011). In

addition, corruption in China has intensified, spreading through the ruling party and

government to every part of society. The forms of corruption have changed over time and

vary among regions (Gong 2006, 2009; Sun 2004). The corruption of officials has also

become a major cause of public dissatisfaction and unhappiness (Brockmann et al. 2009).

3.1 The Negative Effect of Corruption Experience on Life Satisfaction

Corruption experience may undermine happiness in several ways. When people are ex-

torted, they are likely to be unhappy because they lack independence in pursuing their

goals (Chrikov and Ryan 2001). People who lack access to government officials are also

likely to be unhappy when they observe that public goods are available only to those with

personal connections and money (Tavits 2008). Furthermore, we propose that in complex

situations such as bribery, through which interests are exchanged, personal experience with

corruption may also negatively influence people’s happiness through the following two

channels.

First, experience of corruption can reduce happiness because people may feel guilty

when paying or accepting bribes. In most countries, both the corruptor and the corruptee

are guilty according to law (de Sardan 1999). Our data showed that 96 % of the respon-

dents in our survey believe that the government should follow the law in solving problems

regardless of circumstances, indicating that the average Chinese citizen understands that

engaging in corruption violates the law. Recent research on countries such as India and

South Africa, where people are commonly thought to have a high tolerance for corruption,

has also demonstrated that people do not conceptualize corruption in a culturally bounded

relativistic way (Persson et al. 2012; Widmalm 2005). In general, people are frustrated by

corruption, do not accept corruption, and favor ‘‘a rule governed bureaucracy within a

democratic setting’’ (Widmalm 2008, p. 166). Therefore, being involved in corruption can

involve the displeasure of violating the law.

Second, when corruption is common, people are often forced to bribe officials to obtain

what they are legally entitled to and are indeed victims of corruption. Di Tella et al. (2008)

showed that victimization in incidences of corruption may have similar negative impacts

When Are People Unhappy? Corruption Experience, Environment…

123

on people’s happiness, belief systems, and emotions as more direct crimes or threats do.

Thus, we hypothesize that personal experience of corruption tends to generate a negative

impact on happiness.

3.2 Corruption Environment as a Moderator

There are reasons for expecting that the negative effects of corruption experiences are

moderated by the corruption environment and are stronger in a less corrupt environment.

Kelling and Wilson (1982) introduced the broken windows theory by arguing that a broken

office window may be viewed by passersby as a sign that no one cares about the neigh-

borhood; vandals might throw rocks to break more windows, resulting in social disorder

and more severe crimes. This theory argues that people’s perception of appropriateness

largely depends on their expectations of an environment. When people are in an envi-

ronment in which they sense that no one is in charge or no one cares, they feel less social

pressure or perceive fewer constraints against participating in disorderly behavior, and

probably anticipate a smaller psychological cost for doing so. Corruption, which is a crime

in the legal sense, may affect people’s subjective well-being differently depending on the

external environment. When corruption is common in an environment, people are more

likely to engage in bribery to solve problems; bribery becomes a social norm that defines a

person’s choice set and experienced utility in social activities (North 1991). This moder-

ating effect is particularly evident when the two channels proposed in Sect. 3.1 are

considered.

First, a higher level of corruption in the external environment may mark corruption

practices as normal behavior and allow those engaging in it to feel less guilty. Similarly to

the passersby who experience less guilt when breaking the windows of an office that they

believe no one cares about, both the briber and bribee may experience less guilt in a corrupt

environment. People can neutralize feelings of unease or guilt with excuses such as

‘‘everyone else does it’’ (Johnston 1986). Accordingly, corruption experience may reduce

individual happiness less severely in corrupt environments than they do in ethical envi-

ronments. Manion (1996) observed this phenomenon in the case of enterprise licensing in

China. When corruption is common, entrepreneurs believe that the likelihood of encoun-

tering reputable licensing officials is much lower than that of encountering corrupt offi-

cials. Thus, they attempt to bribe officials for licenses, regardless of whether they have

credentials. They believe that almost every applicant resorts to some form of bribery or

exploitation of personal connections to obtain licenses. The popularity of informal ex-

pectations nourished by the environment fuels corruption and justifies the bribing of li-

censing officials, making bribery acceptable subjectively.

Second, a corrupt environment may mitigate the sense of victimization of those being

exploited and thus undermine happiness less. Similarly to the victimization effects of other

crimes, the stigmatizing effect of being victimized by corruption may be smaller in areas

where victimization rates of corruption are high and social disapproval of corruption

victims is low (Powdthavee 2005). This is similar to how relative standpoints affect

people’s happiness in economics (Easterlin 1974, 1995). A generally deteriorating envi-

ronment for an entire society may offset the negative effects of corruption experience on

subjective well-being. Therefore, in societies with rampant corruption, paying bribes for

services that a person is entitled to, such as telephone repair, is common (de Sardan 1999).

People justify engaging in corruption by presenting themselves as victims of a system that

binds them to such practices. As long as people receive what they want through corruption,

they can view themselves as beneficiaries of corruption; this view substantially reduces

Y. Wu, J. Zhu

123

their sense of victimization. In other words, a corrupt environment can blur the line

between being a beneficiary or victim of corruption and make corruption experience less

destructive to happiness.

By contrast, in an environment with relatively low level of corruption, experiencing

corruption personally strikes a heavier blow to morale. When people perceive the gov-

ernment as generally honest, they are likely to follow the rules, hold ideals of equality, and

have an idealized perspective of government. Thus, when people encounter corrupt offi-

cials or witness others gaining status in illegitimate manners, they can become angered and

disillusioned and may adopt extreme conclusions, such as the belief that most of those who

succeed do so through corrupt means (Johnston 1986). Furthermore, when an environment

is less corrupt, the excuse that ‘‘everyone else does it’’ is less valid, and people may feel

more ashamed or victimized when engaging in corruption. In general, the negative effects

of corruption experience on happiness are moderated by the corruption environment. A

legally inappropriate behavior may become appropriate practically when the overall en-

vironment is corrupt. In summary, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 1 Negative effects of corruption experience on happiness: People tend to be

less happy in general when they have personal experience of corruption.

Hypothesis 2 The corruption environment moderates the association described in Hy-

pothesis 1: The negative relationship between corruption experience and happiness is

stronger in environments with lower levels of corruption than it is in environments with

higher levels of corruption.

4 Data and Methods

The data set used to test our hypotheses is mainly constructed using the nationwide Asian

Barometer Survey (ABS) I conducted in China in 2002.1 The data in the survey were

collected by the ABS research team (headquartered at National Taiwan University and

Academia Sinica) in cooperation with the Sociological Institute of the Chinese Social

Science Academy (SICSSA). The sample of the mass survey represents the adult

population over 18 years of age residing in family households at the time of the survey,

excluding those living in the Tibet Autonomous Region. A stratified multistage area

sampling procedure with probability proportional to size measures was used to select the

sample. In total, 3183 people in 28 Chinese provincial units were sampled randomly and

surveyed through face-to-face interviews (see Appendix 1 for details on the ABS). Half of

the participants were male and 90 % of the respondents were married. The participants had

a mean age of 44 years (SD = 14.241), and 16.76 % of the participants had received

tertiary education, 47.55 % had received secondary education or vocational training, and

26.07 % had received only a primary or lower level of education.

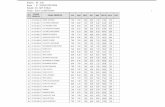

Our dependent variable life satisfaction was at the ordinal level; this variable is a direct

measure of Chinese citizens’ subjective well-being, namely, respondents’ answers to how

satisfied they were with their lives overall on a scale from 0 (least satisfied) to 9 (most

satisfied). Prior research has demonstrated that this measure is the most accepted and can

provide sufficient information on validity and reliability (Ott 2010; Pacek and Radcliff

2008a; Schyns 2003). The average happiness of Chinese citizens in the current data set was

approximately 5.42 out of 9. Figure 1 illustrates the general distribution of Chinese

1 The 2008 and 2013 ABS do not include questions on life satisfaction.

When Are People Unhappy? Corruption Experience, Environment…

123

citizens’ life satisfaction. The distribution shape is similar to that of previous research, such

as that of Knight and Guantilaka (2010a), confirming the general reliability of our data.

Our three major independent variables were respondents’ corruption experience, the

corruption environment of the locality, and these two variables’ interaction. For corruption

experience, we used respondents’ answers to the question, ‘‘Have you or anyone you know

(your family members or friends) personally experienced official corruption in the recent

few years?’’ (with responses ‘‘yes,’’ ‘‘no,’’ and ‘‘don’t know’’). Although this question may

seem sensitive, only 76 respondents marked ‘‘Don’t know.’’ Overall, 22 % of the respon-

dents reported that they or a close family member or friend had experienced corruption

personally. This number is close to the estimate of the 2010 Transparency International (TI)

survey, in which one in four people reported paying bribes in 2009 (TI 2010).

The corruption environment variable is often the most controversial and challenging to

measure. An external aggregated corruption measure would be an ideal means for mea-

suring the objective corruption environment. However, many official data on corruption,

such as the numbers of corruption cases and officials involved, are ambiguous indicators

because they are influenced by both levels of corruption and government anticorruption

efforts. Among the few existing proxies of corruption, such as the Investment Climate

survey created by the World Bank in 2005, most have focused on gauging corruption in

only certain sectors or cities in China, rather than the overall corruption environment in

each province. Thus, we followed Seligson (2006) in using the corruption–victimization

rate as a proxy by calculating the percentage of respondents who reported experiencing

corruption in each province. This rate has been demonstrated to reflect the objective

corruption level and the objective quality of government in a locality more reliably than

corruption perceptions can. The higher this percentage, the higher the level of corruption in

a province is. To consider the moderating effect of the corruption environment, we created

an interaction term between the two independent variables (corruption experience and

corruption environment).

We controlled for other variables on the basis of previous research. For individual

characteristics, a crucial control variable is household economic status. In our survey, this

variable was primarily measured using two items according to respondents’ self-judgment:

the economic situation of the respondent’s family and the respondent’s relative family

income. Responses were rated using a 5-point scale (1 = very bad/far below average;

2 = not very good/a little below average; 3 = so so/average; 4 = OK/a little above av-

erage; 5 = very good/far above average). The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.74, demonstrating

that the measures are reliable. Because both economic status items are subjective measures,

we used only family relative income in the regression models. We also used real values of

family expenditure (by LnExpenditure) provided by respondents to measure the objective

household economic status. Other control variables included respondents’ employment

(unemployment), age (and age2), education, marriage, sex, and economy evaluation (e.g.,

Appleton and Song 2008; Graham and Pettinato 2006). In addition, we controlled for

respondents’ residential status (urban resident, i.e., urban vs. rural) and party membership,

because prior research has shown that Chinese people’s happiness is linked to their social

identity, political affiliations, and social status (Appleton and Song 2008; Jiang et al. 2012;

Liu 2003).2 At the macro level, we controlled for general socioeconomic determinants such

2 Recent research has investigated the happiness of subgroups of the Chinese population; for example,Zhang and Tsang (2013) examined urban Chinese women’s marital happiness and Chyi and Mao (2012)examined Chinese elderly people’s happiness. Because our survey data set does not include detailed data onthese subgroups, we did not include these control variables.

Y. Wu, J. Zhu

123

as provincial per capita gross domestic product (GDP per capita), total population, and

unemployment rate. We obtained these data from the China Statistical Yearbooks. We

further controlled for the large differences among regions in China by following Wang and

Fan (2004) in using a region dummy (i.e., east China = 1, otherwise = 0). Using a re-

gional dummy, rather than provincial dummies, also facilitated avoiding multicollinearity

with other macro variables. Appendix 2 summarizes the details of the statistical data.

Because our dependent variable is ordinal, we used ordered probit (Oprobit) as our basic

analytic model. However, Oprobit coefficients do not measure marginal effects. To ease

interpretation of the results, we also applied the MEOprobit method (Cornelissen 2006),

which reestimates Oprobit results by providing marginal probability estimates similar to

least squares coefficients. MEOprobit estimates represent the amount of mean change in

the dependent variable with a one-unit increase in the independent variable (Moynihan and

Pandey 2010).

5 Empirical Results

5.1 Results of the Basic Models

Table 1 presents the results of the three basic regressions. Regardless of the regression

model used, corruption experience exerted a statistically significant and negative impact on

happiness. In particular, Model 1 was used to test Hypothesis 1 on the basis of complete

observations. The results were significant, showing that both experiencing corruption and

living in a corrupt environment can reduce people’s happiness. Experiencing corruption

can result in, without adjustments for the moderating effect of corruption environment, a

mean reduction of happiness of 0.264.

Models 2 and 3 were used to test Hypothesis 2 by using Oprobit and MEOprobit,

respectively. The interaction term of the two models was statistically significant,

demonstrating the moderating effect of the corruption environment on the negative rela-

tionship between corruption experience and happiness. To further interpret the coefficient

of the interaction term in Models 2 and 3, we drew Fig. 2, which illustrates the changes in

05

1015

20

Per

cent

0 2 4 6 8 10Life Satisfaction

Fig. 1 Distribution of lifesatisfaction in China (based onanswers to ‘‘How satisfied areyou with your lives overall, on ascale from 0 to 9?’’)

When Are People Unhappy? Corruption Experience, Environment…

123

Table 1 Estimation results

Dependent variable: lifesatisfaction

Model 1 Model 2 Model 3MEOprobit without theinteraction term

Oprobit with theinteraction term

MEOprobit with theinteraction term

Impacts of corruption

Corruption experience -0.264*** -0.349*** -0.658***

(0.087) (0.127) (0.241)

Corruption environments -2.526*** -1.578*** -2.951***

(0.462) (0.287) (0.532)

Corruptionexperience 9 corruptionenvironments

0.839* 1.57*

(0.477) (0.893)

Individual characteristics

Family income bylnExpenditure

0.031 0.018 0.034

(0.039) (0.021) (0.039)

Family relative income 2 1.098*** 0.598*** 1.101***

(0.13) (0.073) (0.13)

Family relative income 3 2.166*** 1.166*** 2.173***

(0.13) (0.074) (0.13)

Family relative income 4 2.801*** 1.717*** 2.81***

(0.117) (0.097) (0.12)

Family relative income 5 3.227*** 2.341*** 3.23***

(0.218) (0.366) (0.217)

Economy evaluation 0.447*** 0.239*** 0.448***

(0.042) (0.023) (0.042)

Age -0.047** -0.025** -0.047**

(0.019) (0.01) (0.019)

Age2 0.058*** 0.031*** 0.058***

(0.019) (0.01) (0.019)

Sex -0.066 -0.034 -0.064

(0.078) (0.042) (0.078)

Marriage 0.296* 0.157* 0.295*

(0.16) (0.084) (0.16)

Education 1 -0.396 -0.21 -0.395

(0.396) (0.21) (0.396)

Education 2 -0.506 -0.269 -0.507

(0.395) (0.208) (0.395)

Education 3 -0.311 -0.168 -0.316

(0.378) (0.201) (0.378)

Education 4 -0.561 -0.3 -0.564

(0.376) (0.199) (0.376)

Education 5 -0.367 -0.195 -0.366

(0.397) (0.209) (0.397)

Education 6 -0.502 -0.269 -0.508

(0.386) (0.203) (0.385)

Y. Wu, J. Zhu

123

the marginal effect of experiencing corruption on happiness in different corruption envi-

ronments according to Model 2.

Each of the ten lines in Fig. 2 represents the change in probability (i.e., the y-axis) of

respective happiness groups when the corruption experience value ranges from 0 to 1

among different environments (i.e., x-axis), holding all other variables constant. The figure

shows that experiencing corruption mainly reduced the happiness of those with high levels

of happiness (i.e., happiness scores of 6 and above). When the corruption–victimization

rate was relatively low (when the environment had little corruption), the marginal changes

in probability of these groups were negative and sharp. This means that many people who

previously reported high levels of happiness may have felt significantly less happy, in-

creasing the number of people with low levels of happiness (i.e., happiness scores of 5 and

below). Conversely, people with low levels of happiness showed positive marginal changes

in probabilities when their environment was not highly corrupt. However, when corruption

was exacerbated, the negative impact of corruption experience diminished. Accordingly,

people with high levels of happiness had positive slopes, and people with low levels of

Table 1 continued

Dependent variable: lifesatisfaction

Model 1 Model 2 Model 3MEOprobit without theinteraction term

Oprobit with theinteraction term

MEOprobit with theinteraction term

Party membership 0.192* 0.102* 0.19*

(0.107) (0.058) (0.107)

Unemployment -0.562*** -0.299*** -0.563***

(0.117) (0.062) (0.117)

Urban resident -0.068 -0.035 -0.065

(0.104) (0.056) (0.104)

Macro economy

Ln (GDP per capita) -0.024 -0.01 -0.018

(0.152) (0.081) (0.152)

Ln population 0.086 0.045 0.084

(0.08) (0.043) (0.08)

Unemployment rate -0.041 -0.021 -0.04

(0.033) (0.018) (0.034)

Constant

Region dummy Yes Yes Yes

Wald v2 866.38 874.84 874.84

Prob[v2 0.000 0.000 0.000

Log pseudo-likelihood -5327.164 -5325.809 -5325.809

Log likelihood

Pseudo R2 0.084 0.084 0.084

F

Obs. 2706 2706 2706

Robust standard errors are in parentheses

* Coefficient is statistically significant at 10 % level

** Coefficient is statistically significant at 5 % level

*** Coefficient is statistically significant at 1 % level

When Are People Unhappy? Corruption Experience, Environment…

123

happiness had negative slopes. In rare cases in our sample, when the corruption–victim-

ization rate exceeded 0.398 (which, in our sample, was the case for fewer than 10 % of the

respondents), experiencing corruption even increased happiness slightly, probably because

not engaging in corruption may deprive people of things that they deserve and make them

unhappier. In highly corrupt environments, more people reported higher levels of happi-

ness after experiencing corruption, and those with high levels of happiness began having

positive marginal changes in probabilities; similarly, those with low levels of happiness

began having negative marginal changes in probabilities. In summary, Fig. 2 supports

Hypothesis 2 by demonstrating that the negative impact of corruption experience is

stronger in less corrupt environments and becomes negligible in more corrupt environ-

ments. In addition, Model 3 indicated that corruption experience undermines happiness the

most when the environment has little corruption; conversely, when the corruption–vic-

timization rate increases, corruption experience undermines happiness less.

Regarding the control variables, the coefficients in our study are generally consistent

with the findings of previous studies (Jiang et al. 2012; Knight and Guantilaka 2010a, b;

Knight et al. 2009). Many individual characteristics were significantly associated with

happiness. Among the variables, relative family income exerted the largest positive impact

on life satisfaction. Model 3 showed that a higher relative income increased mean hap-

piness by at least 1.101. Other variables, such as evaluation of the economy, being married,

and party membership were also positively correlated with happiness, as expected. Being

unemployed was negatively correlated with happiness. Similarly to Guriev and Zhu-

ravskaya (2009), who used the World Values Survey data from 1994 to 2003, we dis-

covered that middle-aged people are less happy than younger and older people. In a

departure from existing research, education was not determined to be positively associated

with happiness. Education probably did not exert an influence because of the problems

experienced by China’s higher education system and that a college education has not

Fig. 2 Marginal change in probabilities of different happiness groups, based on Model 2 in Table 1

Y. Wu, J. Zhu

123

Table

2Robustnesstest

Dependentvariable:life

satisfaction

Model

4Model

5Model

6Model

7Model

8Model

9OProbit

withMIs

Hierarchal

linear(H

L)

HLwith2measuresof

corruptionexperience

Model

6with

interactions

OProbitofsystem

-insiders

Oprobitofsystem

-outsiders

Impactsofcorruption

Corruptionexperience

a-0.332***

-0.602***

-0.264**

-0.387

-0.441***

-0.202

(0.123)

(0.25)

(0.121)

(0.34)

(0.152)

(0.125)

Corruptionexperience

b-0.267*

-0.918**

(0.137)

(0.365)

Corruptionenvironments

-1.488***

-2.839***

-2.448***

-2.818***

-1.853***

(0.27)

(0.538)

(0.577)

(0.741)

(0.334)

Corruption

experience

a9

corruption

environments

0.787*

1.357

0.531

1.165***

(0.462)

(0.939)

(1.258)

(0.571)

Corruption

experience

b9

corruption

environments

2.539*

(1.413)

Individual

characteristics

Fam

ilyincomebylnExpenditure

0.037*

0.033

0.03

0.034

0.015

0.079

(0.019)

(0.041)

(0.039)

(0.039)

(0.029)

(0.061)

Fam

ilyrelativeincome2

0.555***

1.189***

1.178***

1.177***

0.612***

0.809

(0.069)

(0.121)

(0.162)

(0.161)

(0.078)

(0.579)

Fam

ilyrelativeincome3

1.121***

2.238***

2.241***

2.244***

1.153***

1.403

(0.068)

(0.11)

(0.143)

(0.143)

(0.078)

(0.567)

Fam

ilyrelativeincome4

1.654***

3.19***

3.192***

3.196***

1.683***

2.174***

(0.092)

(0.159)

(0.178)

(0.177)

(0.109)

(0.579)

Fam

ilyrelativeincome5

2.337***

3.872***

3.873***

3.875***

2.353***

2.752***

(0.32)

(0.406)

(0.427)

(0.428)

(0.425)

(0.968)

When Are People Unhappy? Corruption Experience, Environment…

123

Table

2continued

Dependentvariable:life

satisfaction

Model

4Model

5Model

6Model

7Model

8Model

9OProbit

withMIs

Hierarchal

linear(H

L)

HLwith2measuresof

corruptionexperience

Model

6with

interactions

OProbitofsystem

-insiders

Oprobitofsystem

-outsiders

Economyevaluation

0.239***

0.443***

0.435***

0.435***

0.236***

0.153**

(0.022)

(0.039)

(0.049)

(0.049)

(0.025)

(0.077)

Age

-0.024**

-0.045**

-0.041*

-0.04*

-0.015

-0.06**

(0.009)

(0.018)

(0.021)

(0.021)

(0.012)

(0.031)

Age2

0.03***

0.056***

0.051**

0.05**

0.02

0.069**

(0.01)

(0.118)

(0.022)

(0.022)

(0.012)

(0.031)

Sex

-0.014

-0.062

-0.058

-0.055

-0.002

-0.083

(0.038)

(0.076)

(0.104)

(0.104)

(0.047)

(0.128)

Marriage

0.204*

0.298*

0.292*

0.291*

0.176*

0.285

(0.08)

(0.16)

(0.157)

(0.158)

(0.099)

(0.238)

Education1

-0.105

-0.379

-0.374

-0.383

0.172

-0.509

(0.198)

(0.612)

(0.359)

(0.35)

(0.119)

(0.403)

Education2

-0.166

-0.495

-0.472

-0.483

0.1

-0.127

(0.196)

(0.61)

(0.327)

(0.322)

(0.115)

(0.412)

Education3

-0.095

-0.306

-0.299

-0.307

0.185*

0.006

(0.19)

(0.604)

(0.317)

(0.306)

(0.101)

(0.311)

Education4

-0.183

-0.526

-0.538*

-0.546*

0.081

-0.165

(0.188)

(0.602)

(0.3)

(0.292)

(0.098)

(0.261)

Education5

-0.095

-0.319

-0.293

-0.293

-0.077

0.119

(0.199)

(0.622)

(0.343)

(0.33)

(0.137)

(0.285)

Education6

-0.191

-0.447

-0.459

-0.479

Omitted

-0.157

(0.192)

(0.613)

(0.301)

(0.292)

(0.26)

Party

mem

bership

0.112**

0.185

0.192**

0.195**

0.11

0.123

(0.055)

(0.116)

(0.092)

(0.091)

(0.072)

(0.13)

Y. Wu, J. Zhu

123

Table

2continued

Dependentvariable:life

satisfaction

Model

4Model

5Model

6Model

7Model

8Model

9OProbit

withMIs

Hierarchal

linear(H

L)

HLwith2measuresof

corruptionexperience

Model

6with

interactions

OProbitofsystem

-insiders

Oprobitofsystem

-outsiders

Unem

ployment

-0.291***

-0.57***

-0.565***

-0.57***

-0.341***

-0.064

(0.058)

(0.115)

(0.103)

(0.101)

(0.073)

(0.652)

Urban

resident

-0.014

-0.053

-0.06

-0.059

-0.041

Omitted

(0.05)

(0.097)

(0.163)

(0.163)

(0.06)

Macro

economy

Ln(G

DPper

capita)

-0.031

-0.02

-0.013

0.002

0.059

-0.38

(0.077)

(0.166)

(0.147)

(0.147)

(0.098)

(0.249)

Lnpopulation

-0.013

-0.084

0.078

0.079

0.069

-0.125

(0.04)

(0.079)

(0.075)

(0.075)

(0.049)

(0.138)

Unem

ploymentrate

-0.016

-0.041

-0.042

-0.039

-0.022

-0.055

(0.16)

(0.034)

(0.026)

(0.026)

(0.024)

(0.038)

Constant

2.883

2.759

2.649

(2.102)

(2.08)

(2.057)

Regiondummy

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Waldv2

1221.39

18,531.16

693.9

80.61

Prob[

v20.000

0.000

0.000

0.000

Logpseudo-likelihood

-4174.938

-318.66

Loglikelihood

-5540.962

-5413.592

-5411.765

PseudoR2

0.083

0.092

F33.07

(0.000)

When Are People Unhappy? Corruption Experience, Environment…

123

Table

2continued

Dependentvariable:life

satisfaction

Model

4Model

5Model

6Model

7Model

8Model

9OProbit

withMIs

Hierarchal

linear(H

L)

HLwith2measuresof

corruptionexperience

Model

6with

interactions

OProbitofsystem

-insiders

Oprobitofsystem

-outsiders

Obs.

3183

2706

2644

2644

2104

344

Robuststandarderrors

arein

parentheses

*Coefficientisstatisticallysignificantat

10%

level

**Coefficientisstatisticallysignificantat

5%

level

***Coefficientisstatisticallysignificantat

1%

level

aRefersto

respondents’owncorruptionexperience

inModels6and7,andstayssameas

inTable

1forallother

regressionmodels

bRefersto

corruptionexperience

ofrespondents’familymem

bersandfriends

Y. Wu, J. Zhu

123

appreciably helped young Chinese people find jobs recently. In another departure from

previous research, we did not identify a significant correlation between happiness and

urban residency. Moreover, the coefficients of the provincial GDP per capita, population

size, and unemployment rate were not significant.

5.2 Robustness Tests

We used a series of alternative regressions to test the robustness of our findings. Table 2

shows the results of these tests in sequence. First, Model 4 addressed the influence of

missing data on the results. The number of observations with complete information in the

basic models was 2706; therefore, the problem of missing values was not a major concern.

However, for robustness analysis, we followed the best practices for accounting for

missing values and generated multiple complete data sets by using model-based imputa-

tions (Penn 2007). By adopting this strategy, we adopted an agnostic view of missing

values and used observable associations between missing observations and other revealed

information of the same subjects to determine the possible values of missing observations

(King et al. 2001; Rubin 1987). We discovered that the scale of the estimates was largely

similar in Model 2 and Model 4, and the standard errors of many variables in Model 4 were

smaller than those in Model 2; this observation is consistent with those of other studies on

multiple imputations (MIs) (e.g., Penn 2007). This comparison demonstrated that estimates

based only on complete cases are not severely biased.

Second, because our models included variables at both the provincial and individual

levels, we performed a hierarchical linear analysis in Model 5. Model 5 was based on the

complete observations, enabling us to draw Fig. 3 to illustrate the moderating effect.

Figure 3 shows the marginal effect of corruption experience on happiness throughout the

observed range of corruption–victimization rates. The 95 % confidence intervals around

the line indicate the conditions under which corruption experience has a significant effect

on happiness. Corruption experience exerts a significant effect on life satisfaction when the

upper and lower bounds of the confidence interval are both above (or below) the zero line

(Brambor et al. 2006; Fredrikssona and Svensson 2003).

Figure 3 shows that corruption experience had a significant, negative effect on happi-

ness only when the corruption–victimization rate in a province was at or less than 0.278, or

-1-.5

0.5

Effe

cts

on H

appi

ness

.078 .118 .158 .198 .238 .278 .318 .358 .398 .438Corruption Environments

Fig. 3 Average marginal effectsof corruption experience onhappiness with 95 % CIs, basedon Model 5 in Table 2

When Are People Unhappy? Corruption Experience, Environment…

123

27.8 %. Approximately 80 % of the observations fell within this range, and among them,

319 respondents reported experiencing corruption personally. The graph also shows that

the lower the corruption–victimization rate, the larger the negative impact of corruption

experience on happiness was. For example, when the corruption–victimization rate was

0.278, experiencing corruption reduced happiness by 0.225. However, when the corrup-

tion–victimization rate decreased to 0.078, corruption experience reduced happiness by

0.496. By contrast, as the other end of the spectrum in Fig. 3 shows, when the corruption–

victimization rate was 0.438, or 43.8 %, the marginal effect of corruption experience

became almost zero (-0.008) and nonsignificant. This means that when the environment is

extremely corrupt, corruption experience may not significantly undermine happiness; this

pattern is similar to that shown in Fig. 2.

Third, Models 6 and 7 addressed a potential measurement error in the basic models. In

the basic regressions, we measured corruption experience according to answers to the

question ‘‘Have you or anyone you know (your family members or friends) personally

experienced official corruption in the recent few years?’’ The advantage of using this

question is that it encouraged respondents to report various experiences of corruption;

Seligson (2006) argued that people might report their own corruption experience as the

experience of their family members and friends to avoid trouble. Indeed, many respondents

in our survey who reported having corruption experience refused to disclose whether the

experience was their own or their family members’ or friends’. Only 11 % of respondents

reported experiencing corruption personally. This low report rate likely supports Seligson’s

warning. Furthermore, in a collectivist society such as China, it is reasonable to assume

that a respondent’s happiness can be influenced by the corruption experience of family

members and friends. The drawback of this measure is that it may mix respondents’ own

corruption experience with those of family members and friends, leading to inflated

measures of corruption experience. Thus, we separated respondents’ corruption experience

from those of their close family members and friends to assess the robustness of our

findings.

We also used hierarchical linear regressions in Models 6 and 7 to more straightfor-

wardly illustrate the moderating effect. The results of Model 6 confirmed Hypothesis 1 by

demonstrating that personal corruption experience and those of a friend or family member

both significantly reduce the respondents’ life satisfaction. Model 7 was used to test

-1

-.5

0

.5

.078 .118 .158 .198 .238 .278 .318 .358 .398 .438Corruption Environments

Effec

ts o

n H

appi

ness

Fig. 4 Average marginal effectsof respondents’ self-reported owncorruption experience onhappiness with 95 % CIs, basedon Model 7 in Table 2

Y. Wu, J. Zhu

123

Hypothesis 2 by adding two respective interaction terms between the corruption experience

and corruption environment measures. We discovered that the second interaction term was

statistically significant and positive, indicating that the moderating effect of the corruption

environment acted as predicted in Hypothesis 2 regarding the association between hap-

piness and the corruption experience of family members and friends. Because the inter-

action term between respondents’ corruption experience and the corruption environment

was not significant, we used Fig. 4 to detect the moderating effect. The general trend in

Fig. 4 is still consistent with Hypothesis 2. In an extremely corrupt environment (above

0.278, as shown in Fig. 3), corruption experience did not significantly reduce happiness.

Figure 4 also shows that in low-corruption environments (below 0.158), the negative

impact of corruption experience on happiness was not significant, with a wide 95 %

confidence interval oriented toward the area below zero. Only 5 % of respondents reported

having personally experienced corruption in these low-corruption environments; the sparse

distribution of personal corruption experience is likely the main reason for the non-

significant result in these environments.

Finally, our current measure of respondents’ corruption experience does not provide

information on the role of the respondents in their corruption experience, rendering us

unable to test Hypotheses 1 and 2 separately for bribers and bribees. Because no questions

in the survey directly differentiated bribees from bribers, we used respondents’ occupation

as a proxy and categorized them as ‘‘system insiders’’ (tizhinei), referring to those who are

employed by the government, such as civil servants and staff of state organizations, and

‘‘system outsiders’’ (tizhiwai), referring to all other respondents. Research on corruption in

China shows that system outsiders are more often the bribers, seeking protection or crucial

state-controlled materials from system insiders, who are more likely to be the bribees.

Models 8 and 9 were used to test our hypotheses separately among system outsiders and

system insiders by using the complete data and original measure of corruption experience.

The results of Model 8 indicated that Hypotheses 1 and 2 still hold for system outsiders.

The low number of system insiders surveyed caused testing the moderating effect of the

corruption environment using the interaction term for system outsiders to be difficult.

However, the nonsignificant negative coefficient of corruption experience in Model 9

implied a slight negative impact of corruption experience on happiness for system insiders,

probably because the environment surrounding system insiders generally tends to have a

higher level of corruption. System insiders are more likely to experience or observe cor-

ruption than system outsiders, and their major reference points are their peers within the

state system. Hence, as predicted in Hypothesis 2, the external corruption environment of

system insiders reduces the negative impact of corruption experience on their happiness. In

general, the regression results and robustness tests confirmed Hypotheses 1 and 2.

6 Discussion and Conclusion

In this research, we examined the impact of corruption on the subjective well-being of

Chinese citizens by using the 2002 ABS I on China. We specifically focused on the effects

of corruption experience on happiness and the moderating effect of the corruption envi-

ronment; these effects have rarely been studied. We discovered that corruption experience

undermines individual life satisfaction in general. More importantly, consistent with the

broken windows theory prediction and the reference standard theory in economics, the

negative effect of corruption experience is moderated by the external corruption

When Are People Unhappy? Corruption Experience, Environment…

123

environment. Corruption experience tends to reduce happiness more severely when the

external environment has a lower level of corruption. This decrease is because a corrupt

environment may reduce the psychological cost of shame, guilt, or victimization for those

involved in corruption, regardless of whether the participant is a briber or bribee or is

participating willingly or forcibly. We tested our hypotheses by using Oprobit, with and

without MIs, a hierarchical linear model, and several other robustness tests and found

overall support.

In addition to enriching the current literature on corruption and happiness, our research

potentially complements the economic and psychological findings indicating that material

income and luxury do not necessarily secure happiness (Easterlin 1974; Ryan and Deci

2001) by showing that using illegal means to obtain material benefits may actually un-

dermine happiness. Our findings also contribute to the literature on government trust and

regime legitimacy because citizens’ subjective well-being forms the basis for winning

electoral competitions in modern democracies and political support in authoritarian

regimes. Research has shown that authoritarian regimes can still shape public perceptions

of government corruption and forge support by manipulating government-controlled media

(Stockmann and Gallagher 2011). The current research indicates that if governments do not

prevent corruption in accordance with propaganda, then direct personal encounters with

official corruption only disappoint and disillusion people and, in turn, damage the gov-

ernment’s legitimacy and image.

This research also reveals the resilient side of corrupt regimes. When the environment is

already highly corrupt, public experience of corruption does not further undermine life

satisfaction, because people tend to accept corruption as a common practice and high levels

of corruption fall into equilibrium (Manion 2004). This situation partially explains why

some corrupt regimes can survive growing public complaints. When people are used to

corruption, experience of corruption or exposure to corruption cases may not generate

enough shock and reduction of people’s life satisfaction to motivate wide-scale public

protests requiring substantial government reforms, much less regime change. Thus,

although overall happiness in a society might be low, people’s motivation to change the

status quo is also low. This means that to control corruption, it is vital to change the overall

beliefs regarding the popularity of corruption; otherwise, corruption can intensify because

people tend to ‘‘numbly’’ follow corruption practices shamelessly and without feeling

victimized, while complaining about corruption nominally.

We are aware of the possible limitations of the current research. Our first concern lies in

the victimization data. We must be cautious regarding the extent to which people are

willing to report their corruption experience in surveys, especially in a nondemocratic

society such as China. We attempted to accommodate this problem by considering dif-

ferent measurements of corruption experience. The large gap between our major measure

of corruption experience and respondents’ self-reported corruption experience suggests

that respondents may have underreported their personal corruption experience. We also

noticed that further differentiating respondents’ corruption experience from others’ expe-

rience caused more values of corruption experience to be missing in the survey, as shown

by the number of observations in Models 6 and 7. This further strengthens our suspicion

that some respondents did not want to directly report their own corruption experience.

Future research may explore more effective means for measuring corruption experience.

Another limitation is that our current data set does not reveal respondents’ role in their

corruption experience. Although grouping respondents according to their occupations

solves the problem to an extent, this categorization is still an approximate mapping of the

groups of bribers and bribees. Reality is certainly far more complex; sometimes, system

Y. Wu, J. Zhu

123

outsiders may be bribees and system insiders may be bribers. Future research may attempt

to detect more accurately respondents’ role in corruption and test our proposed causal

mechanism between corruption experience and happiness through either detailed surveys

or psychological experiments. Future research can also examine other potential mod-

erators, such as people’s attitudes toward corruption, which are not included in the current

data set.

Overall, our research confirms the negative effects of corruption experience on happi-

ness. Moreover, it demonstrates that the corruption level of the general environment, or the

objective quality of government, is crucial for people’s life satisfaction because it influ-

ences the magnitude of the negative impact of corruption experience on happiness.

Acknowledgments The authors’ special thank goes to editor-in-chief Prof. Antonella Delle Fave, co-editor of Economics Prof. Stephanie Rossouw, and two anonymous reviewers, as well as Jennifer Bussell,Ting Gong, Lianjiang Li, Jie Lu, Xin Sun, Sandra Kit Man Tsang, Dong Zhang, and Huiping Zhang, fortheir valuable comments and tremendous help. This project is partially funded by the Seed Funding of theUniversity of Hong Kong (Project Code: 201209159003).

Appendix 1: A Brief Introduction of ABS I

The ABS is a comparative survey of democratization and value change in East Asia. The

ABS I mainland China survey is part of the larger ABS project. It is a nationwide survey

that was conducted in China in 2002 by the ABS research team in cooperation with the

SICSSA. As a partner of Global Barometer Surveys (GBS), ABS uses the GBS reporting

method as its model and requires all country teams to comply with GBS network research

protocols to ensure that the data are reliable and valid. The ABS mainland China survey

has been conducted every 5 years since 2002 and is widely used by researchers. According

to the research protocol, the method for selecting sampling units in China is randomized.

To ensure that coverage of Chinese rural areas and minority populations in their correct

proportions, a stratified multistage area sampling procedure with probabilities proportional

to size measures was employed to select the sample. The primary sampling units employed

in the rural domain were counties (xian). Before selection, counties were stratified ac-

cording to region and geographical characteristics. In total, 129 counties were selected as

the primary sampling units for the entire project. The secondary sampling units were

townships in rural areas (xiang) or subdistricts in urban areas (jiedao). The tertiary stage of

selection was geared toward neighborhoods in urban areas and administrative villages in

rural areas. In total, 249 administrative villages and 247 neighborhoods were selected in

this sampling stage. ABS I involved scheduling face-to-face interviews with 3752 people,

3183 of whom provided valid responses, yielding a response rate of 84.1 %. In this

research, we used the poststratification technique to ensure that the distribution of our

sampled respondents among age cohorts, sex, and rural/urban areas was compatible with

that for the population. Furthermore, to ensure that data are comparable at the micro level

among countries, the ABS requires questionnaires to have a core module of identical or

functionally equivalent questions for use in various East Asian countries. The question-

naire used in China is available on the ABS website. All ABS team members received

intensive, weeklong training before going into the field. Codified guidelines were provided

to every interviewer. All of the interview teams were directed by field supervisors, who

also performed random back-checks with respondents to ensure that sampling and inter-

views were conducted correctly. Quality checks were enforced at every stage of data

When Are People Unhappy? Corruption Experience, Environment…

123

conversion. For further information on ABS I data, visit the official ABS website at www.

asianbarometer.org.

Appendix 2

See Table 3.

Table 3 Statistical summary of relevant variables

Categoricalvariable

Obs 0a 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

Life satisfaction 3138 3.49 3.12 4.65 7.78 12.33 20.36 15.04 13.45 8.67 12.36

Family relativeincome

3168 16.35 22.51 52.05 8.30 0.79

Sex 3183 49.48 50.52

Marital status 3181 9.12 90.88

Education 3180 26.07 16.76 27.74 19.81 3.62 5.66 0.35

Party membership 3183 86.90 13.10

Urban resident 3182 45.03 54.97

Unemployment 3031 13.43 83.93

Economyevaluation

3044 0.92 10.35 5.55 47.01 36.17

Corruptionexperience

3107 77.70 22.30

Region dummyb 3183 56.93 43.07

Numerical variable Obs Mean Min Max SD

Family income by LnExpenditure 3031 31,127.6 200 1,399,986 171,389.8

Age 3183 44.26 18 90 14.241

Age2 3183 21.617 3.24 81 13.696

GDP per capita 3183 8562.143 2791 29,690 4924.391

Population 3183 5363.384 523 9555 2397.003

Unemployment rate 3183 3.674 1.2 11.1 1.236

Corruption environment 3183 0.224 0.078 0.474 0.088

We separate the information for numerical and categorical variables into two tables. For numerical vari-ables, we provide the typical statistical details. For categorical variables, we provide the percentage ofrespondents for each categorical value and the total number of observations for each variable, becauseinformation such as the mean, maximum, and standard errors of categorical variables is not particularlymeaningfula In this row, 0–9 are different values taken by each categorical variableb Region dummy is 1, if a respondent is in east China; and 0 otherwise. East China includes Beijing,Tianjin, Shanghai, Zhejiang, Jiangsu, Fujian, Liaoning, Shandong and Hebei (Wang and Fan 2004)

Y. Wu, J. Zhu

123

References

Alesina, A., Tellab, R. D., & MacCulloch, R. (2004). Inequality and happiness: Are Europeans andAmericans different? Journal of Public Economics, 88, 2009–2042.

Alvarez-Diaz, A., Gonzalez, L., & Radcliff, B. (2010). The politics of happiness: On the political deter-minants of quality of life in the American states. Journal of Politics, 72, 894–905.

Appleton, S., & Song, L. (2008). Life satisfaction in urban China: Components and determinants. WorldDevelopment, 36(11), 2325–2340.

Bjørnskov, C., Dreher, A., & Fischer, J. A. V. (2008). Formal institutions and subjective well-being:Revisiting the cross-country evidence. KOF working papers No. 192.

Bok, D. (2010). The politics of happiness: What government can learn from the new research on well-being.Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Brambor, T., Clark, W. R., & Golder, M. (2006). Understanding interaction models: Improving empiricalanalyses. Political Analysis, 14, 63–82.

Brockmann, H., Delhey, J., Welzel, C., & Yuan, H. (2009). The China puzzle: Falling happiness in a risingeconomy. Journal of Happiness Studies, 10, 387–405.

Burkholder, R. (2005). Chinese far wealthier than a decade ago—But are they happier? The Gallup Or-ganization. http://sww.gallup.com/poll/content/longin.aspx?ci=14548. Accessed June 29, 2012.

Chrikov, V. I., & Ryan, R. M. (2001). Parent and teacher autonomy-support in Russia and the U.S.adolescents: Common effects on well-being and academic motivation. Journal of Cross-CulturalPsychology, 32, 618–632.

Chyi, H., & Mao, S. (2012). The determinants of happiness of China’s elderly population. Journal ofHappiness Studies, 13(1), 167–185.

Cornelissen, T. (2006). MEOPROBIT: Stata module to compute marginal effects after estimation of orderedprobit. http://ideas.repec.org/c/boc/bocode/s456788.html. Accessed March 24, 2013.

Crabtree, S., & Wu, T. (2011). China’s puzzling flat line. Gallup Management Journal. http://gmj.gallup.com/content/148853/china-puzzling-flat-line.aspx#1. Accessed June 29, 2012.

de Sardan, J. P. O. (1999). A moral economy of corruption in Africa? Journal of Modern African Studies,37(1), 25–52.

Dehejia, R., DeLeire, T., & Luttmer, E. F. P. (2007). Insuring consumption and happiness through religiousorganizations. Journal of Public Economics, 91, 259–270.

Di Tella, R., & MacCulloch, R. J. (2005). Partisan social happiness. Review of Economic Studies, 72,367–393.

Di Tella, R., MacCulloch, R. J., & Nopo, H. (2008). Happiness and beliefs in criminal environments. Inter-American Development Bank working paper No. 662. https://www.econstor.eu/dspace/bitstream/10419/51503/1/589979612.pdf. Accessed March 24, 2013.

Di Tella, R., MacCulloch, R. J., & Oswald, A. (2001). Preference over inflation and unemployment:Evidence from surveys of happiness. American Economic Review, 91(1), 335–341.

Doig, A., McIvor, S., & Theobald, R. (2006). Numbers, nuances and moving targets: Converging the use ofcorruption indicators or descriptors in assessing state development. International Review of Admin-istrative Sciences, 72(2), 239–252.

Easterlin, R. (1974). Does economic growth improve the human lot? In P. A. David & M. W. Reder (Eds.),Nations and households in economic growth (pp. 89–125). New York: Academic Press.

Easterlin, R. (1995). Will raising the incomes of all increase the happiness of all? Journal of EconomicBehavior and Organization, 27(June), 35–48.

Easterlin, R., Morgan, R., Switek, M., & Fei, W. (2012). China’s life satisfaction 1990–2010. In Pro-ceedings of national academy of sciences of the United States of America. http://www.pnas.org/content/early/2012/05/09/1205672109.abstract

Egger, P., & Winner, H. (2005). Evidence on corruption as an incentive for foreign direct investment.European Journal of Political Economy, 21, 932–952.

Fredrikssona, P. G., & Svensson, J. (2003). Political instability, corruption and policy formation: The case ofenvironmental policy. Journal of Public Economics, 87, 1383–1405.

Gong, T. (2006). Corruption and local governance: The double identity of Chinese local governments inmarket reform. The Pacfic Review, 19(1), 85–102.

Gong, T. (2009). Institutional learning and adaptation: Developing state audit capacity in China. PublicAdminstration and Development, 29(1), 33–41.

Graafland, J., & Compen, B. (2014). Economic freedom and life satisfaction: Mediation by income percapita and generalized trust. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15(3), 1–22.

When Are People Unhappy? Corruption Experience, Environment…

123

Graham, C., & Pettinato, S. (2006). Frustrated achievers: Winners, losers, and subjective well-being inPeru’s emerging economy. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 606,128–153.

Guriev, S., & Zhuravskaya, E. (2009). (Un)happiness in transition. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 23(2),143–168.

Haller, M., & Hadler, M. (2006). How social relations and structures can produce happiness and unhap-piness: An international comparative analysis. Social Indicators Research, 75, 169–216.

Helliwell, J. F. (2006). Well-being, social capital and public policy: What’s new? Economic Journal,116(510), C34–C45.

Helliwell, J. F., & Huang, H. (2008). How’s your government? International evidence linking good gov-ernment and well-being. British Journal of Political Science, 38, 595–619.

Huntington, S. P. (1968). Political order in changing societies. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.Jiang, S., Lu, M., & Sato, H. (2012). Identity, inequality, and happiness: Evidence from urban China. World

Development, 40(6), 1190–1200.Johnston, M. (1986). Right and wrong in American politics: Popular conceptions of corruption. Polity,

18(3), 367–391.Kahneman, D., & Krueger, A. B. (2006). Developments in the measurement of subjective well-being.

Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20, 3–24.Kelling, G. L., & Wilson, J. Q. (1982). Broken windows: The police and neighborhood safety. The Atlantic,

249(3), 29–38.King, G., Honaker, J., Joseph, A., & Scheve, K. (2001). Analyzing incomplete political science data: An

alternative algorithm for multiple imputation. American Political Science Review, 95(1), 49–69.Knight, J., & Guantilaka, R. (2011). Does economic growth raise happiness in China? Oxford Development

Studies, 39(1), 1–24.Knight, J., & Gunatilaka, R. (2010a). Great expectations? The subjective well-being of rural–urban migrants

in China. World Development, 38(1), 113–124.Knight, J., & Gunatilaka, R. (2010b). The rural–urban divide in China: Income but not happiness? Journal of

Development Studies, 46(3), 506–534.Knight, J., Song, L., & Gunatilaka, R. (2009). Subjective well-being and its determinants in rural China.

China Economic Review, 20(4), 635–649.Leff, N. (1964). Economic development through bureaucratic corruption. American Behavioral Scientist,

8(3), 8–14.Liu, Z. (2003). The economic impact and determinants of investment in human and political capital in

China. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 51(4), 823–850.Manion, M. (1996). Corruption by design: Bribery in Chinese enterprise licensing. Journal of Law Eco-

nomics and Organization, 12(1), 167–195.Manion, M. (2004). Corruption by design: Building clean government in mainland China and Hong Kong.

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.Montinola, G., & Jackman, R. W. (2002). Sources of corruption: A cross-country study. British Journal of

Political Science, 32, 147–170.Morris, S. D. (1991). Corruption and politics in contemporary Mexico. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama

Press.Moynihan, D. P., & Pandey, S. K. (2010). The big question for performance management: Why do managers

use performance information? Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 20(4), 849–866.North, D. C. (1991). Institutions. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 5(1), 97–112.Nye, J. S. J. (1967). Corruption and political development: A cost-benefit analysis. American Political

Science Review, 61(2), 417–427.Ott, J. C. (2010). Good governance and happiness in nations: Technical quality precedes democracy and

quality beats size. Journal of Happiness Studies, 11, 353–368.Pacek, A. C., & Radcliff, B. (2008a). Assessing the welfare state: The politics of happiness. Perspectives on

Politics, 6, 267–277.Pacek, A. C., & Radcliff, B. (2008b). Welfare policy and subjective well-being across nations: An indi-

vidual-level assessment. Social Indicators Research, 89, 179–191.Penn, D. A. (2007). Estimating missing values from the general social survey: An application of multiple

imputation. In Department of economics and finance working paper series, Middle Tennessee StateUniversity.

Persson, A., Rothstein, B., & Teorell, J. (2012). Why anti-corruption reforms fail: Systemic corruption as acollective action problem. Governance: An International Journal of Policy, Administration and In-stitutions, 25(4), 1–23.

Powdthavee, N. (2005). Unhappiness and crime: Evidence from South Africa. Economica, 72, 531–547.

Y. Wu, J. Zhu

123

Radcliff, B. (2001). Politics, markets, and life satisfaction: The political economy of human happiness.American Political Science Review, 95(4), 939–952.

Radcliff, B. (2005). Class organization and subjective well-being: A cross-national analysis. Social Forces,84(1), 509–526.

Rose-Ackerman, S. (1999). Corruption and government: Causes, consequences, and reform. Cambridge,UK: Cambridge University Press.

Rothstein, B. (2010). Happiness and the welfare state. Social Research, 77, 441–468.Rubin, D. (1987). Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. New York: Wiley.Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and

eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 141–166.Samanni, M., & Holmberg, S. (2010). Quality of government makes people happy. In Quality of Govern-

ment working paper series 2010:1. GOTEBORG: The Quality of Government Institute Department ofPolitical Science, University of Gothenburg.

Schyns, P. (2003). Income and life satisfaction: Chapter 2: Life satisfaction: The concept, its measurabilityand cross-national comparability. Netherlands: Eburon Delft.

Seligson, M. A. (2002). The impact of corruption on regime legitimacy: A comparative study of four LatinAmerican countries. Journal of Politics, 64(2), 408–433.

Seligson, M. A. (2006). The measurement and impact of corruption victimization: Survey evidence fromLatin America. World Development, 34(2), 381–404.

Stockmann, D., & Gallagher, M. E. (2011). Remote control: How the media sustains authoritarian rule inChina. Comparative Political Studies, 44(4), 436–467.

Sun, Y. (2004). Corruption and market in contemporary China. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.Tavits, M. (2008). Representation, corruption, and subjective well-being. Comparative Political Studies,

41(12), 1607–1630.TI. (2010). Global corruption barometer. http://www.transparency.org/research/gcb/gcb_2009. Accessed

June 29, 2012.Vendrik, M. C. M., & Woltjer, G. B. (2007). Happiness and loss aversion: Is utility concave or convex in

relative income? Journal of Public Economics, 91, 1423–1448.Wall Street Journal. (2011). Why China is unhappy? Rising discontent is challenging communist party rule.

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052970204224604577029550570114554.html. Accessed June29, 2010.

Wang, X., & Fan, G. (2004). Zhongguo diqu chaju de biandong qushi he yingxiang yinsu (The changingtrends and causes of Chinese regional inequality). Jingji Yanjiu (Economic Studies), 1, 33–44.

Warren, M. (2004). What does corruption mean in a democracy? American Journal of Political Science,48(2), 328–343.

Widmalm, S. (2005). Explaining corruption at the village level and individual level in India. Asian Survey,XLV(5), 756–776.

Widmalm, S. (2008). Decentralisation, corruption and social capital: From India to the West. ThousandOaks, CA: Sage.

Zhang, H., & Tsang, S. (2013). Relative income and marital happiness among urban Chinese women: Themoderating role of personal commitment. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14(5), 1575–1584.

When Are People Unhappy? Corruption Experience, Environment…

123