Valence bond solid state induced by impurity frustration in Cr8Ni

Animated Frustration, or, the Ambivalence of Player Agency (2016)

Transcript of Animated Frustration, or, the Ambivalence of Player Agency (2016)

Article

Animated Frustrationor the Ambivalenceof Player Agency

Daniel Johnson1

AbstractFrustration is an everyday experience for many users of game media. Distinct fromrelated sensations such as difficulty, frustration is perhaps best characterized aswhen the agency of the player becomes obstructed. This can lead to the feeling of anambivalent, uncooperative relationship with the game machine. This article will focuson two examples to demonstrate some of the possible manifestations of frustrationin game media. The first, ‘‘Steel Battalion: Heavy Armor,’’ will deal with motioncontrol gestures that are misinterpreted by the game in a way that obstructs theplayer’s ability to interact with the game. The second, ‘‘Papers, Please,’’ will considerrepetitive gameplay that limits the player’s actions. Drawing on recent scholarship inanimation studies, both cases will be approached as a form of what Sianne Ngaidescribes as ‘‘animatedness,’’ the feeling of becoming an automaton and of havingone’s agency frustrated by technology.

Keywordsfrustration, agency, ambivalence, animatedness, repetition, affect

Frustration is something that many users will experience while playing game media.

The feeling that a game doesn’t work or doesn’t work as we might want or expect it

to is one that can disrupt the pleasures of play and even thwart a player’s chances for

success within a game. But these feelings of frustration also raise more general

1 University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA

Corresponding Author:

Daniel Johnson, University of Chicago, 1115 East 58th Street, Chicago, IL 60637, USA.

Email: [email protected]

Games and Culture2015, Vol. 10(6) 593-612

ª The Author(s) 2015Reprints and permission:

sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.navDOI: 10.1177/1555412014567229

gac.sagepub.com

at UNIV OF CHICAGO LIBRARY on October 25, 2015gac.sagepub.comDownloaded from

questions about how user agency can be obstructed by the game machine that a per-

son is interacting with. Frustration with game media can occur through faulty hard-

ware such as buttons on a controller that stick and do not respond properly, glitches

that disrupt a player’s actions within a game, or even design elements that upset the

player’s ability to pursue his or her goals. The range of experiences that can be

described as emotionally or affectively frustrating while operating game media are

thus quite diverse.

How, then, should we attend to feelings of frustration that arise while playing

game media? Rather than approaching this experience from the perspective of eva-

luation, this article will instead characterize frustration as part of the dynamic of how

game media respond to and represent player agency. Frustration is perhaps best

understood as something that intersects with but is distinct from related experiences

such as difficulty. Both contain subjective elements that can vary from one individ-

ual experience to another, but difficulty is perhaps more readily grasped as some-

thing which can be rewarding and part of a game’s way of motivating a player to

continue playing. In this sense, difficulty is integral to game media in that it provides

a way of balancing challenge, effort, and reward. It is part of the logic through which

we evaluate success. Frustration is conversely what is felt at those moments when

the desire for the game to execute the player’s agency in clear and precise ways

is disrupted in a manner that draws out an ambivalence of interaction between the

player and the game machine. It is felt at moments when we lose control or feel like

we are beginning to lose control, such as when an in-game camera moves without

our command to avoid elements of the game-world environment.1 With that distinc-

tion in mind, this article will approach frustration in game media from this perspec-

tive of confounded agency and its connection to the ambivalent affect between

players and game media.2

The Ugly Affect of Animatedness

This sense of frustration can be characterized as what Sianne Ngai has termed an

‘‘ugly feeling.’’ What Ngai finds distinctive in ugly feelings—emotions such as

envy, irritation, and paranoia— is their relationship with agency. She describes the

agency of ugly feelings as ‘‘suspended’’ due to the way they do not motivate those

who experience them to action but rather induce and intersect with inaction and deny

catharsis or a sense of virtue (Ngai, 2005, pp. 1–6). This is where we might distin-

guish frustration from difficulty in gaming, which Juul (2013) has described as hav-

ing the potential to spur the player on to trying again and overcoming the challenge

at hand. This is not to say that frustration and motivation are mutually exclusive but

rather that what is specific about frustration in game media is the way that it reso-

nates with feeling helpless and even wanting to stop playing. What is ‘‘ugly’’ about

frustration in gaming is the ways that it brings forth the material qualities of game

media in disruptive ways and how it obstructs or restricts the feeling of agency a

player has while playing. The immersive forms of feedback we normally experience

594 Games and Culture 10(6)

at UNIV OF CHICAGO LIBRARY on October 25, 2015gac.sagepub.comDownloaded from

while playing a game are what give pleasure (and are often connected to the way that

games represent success), but when feedback begins to signal a gap between player

and game, the experience becomes negative and frustrating. In this sense, frustration

is not received as part of the intended challenge that the game offers us but rather

something we perceive as unfavorable about the game’s design or presentation and,

at least sometimes, a reason to stop playing.

This sense of obstructed agency during play and of a loss of control is tied to what

Ngai describes as ‘‘animatedness.’’ For Ngai (2005, pp. 91–99), this is when our

sense of agency has entered into an ambiguous relationship with technology, when

our bodily movements begin to feel involuntary, and when we feel that we are

becoming automatized in some way. Automatization is a familiar concept in regard

to the way critics and scholars have described mechanization of human bodies and

labor under modernity in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. But, in analyzing

contemporary game media, we might also consider the relationship between the

‘‘gamification’’ of work with related sentiments of repetition and the ambivalent

affects of human–machine interfaces. In developing her concept of animatedness,

Ngai turns to stop motion animation and its dynamic of ‘‘agitated things’’ that have

been rendered in jerky movements and the ‘‘deactivated persons’’ of production, the

unseen animators bringing these figures to life onscreen.3 The tension of animated-

ness is therefore tied to movement, the figuration of human agency in visual media,

and the relationship of a human actor with the production of those sensations. As this

article will discuss, these are also key qualities to understanding frustration in game

media.

One example that might demonstrate how this dynamic of ‘‘agitated things’’ and

‘‘deactivated persons’’ resonates with game media is Dragon’s Lair, an arcade game

first released in 1983. Dragon’s Lair was a laserdisc game that featured full motion

hand-drawn animation by Don Bluth, a former animator for Walt Disney Studios.

The game used prerecorded video footage that the player could interact with in lim-

ited ways, essentially moving from chapter to chapter on the disk, as they success-

fully navigated their character Dirk the Daring through the game’s content. When

the game presented the player with a visual prompt to act in a certain way (such

as moving in one direction or executing actions such as swinging their sword), a suc-

cessfully timed input to execute the command would show Dirk defeat the challenge

and then progress to the next video sequence (Figure 1). However, although the

visual presentation for the game was quite spectacular, the controls for the game

were rather minimal, namely, a simple joystick and button. The only actions the

player could perform would be to move in a single direction or perform a general

‘‘action’’ that would fulfill a variety of tasks dependent on the situation. Choosing

the wrong direction or moving the joystick instead of pressing the button at the

prompt would produce a failed action, resulting in a character death animation and

returning the player to the start of the game to begin again. The timing given to suc-

cessfully execute these commands was also quite limited and could easily result in

failure and again sending the player back to the beginning of the game.4

Johnson 595

at UNIV OF CHICAGO LIBRARY on October 25, 2015gac.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Given this limited mode of interaction, in what ways is the player of a game like

Dragon’s Lair a ‘‘deactivated person’’ in relation to the game’s figuration of their

agency? There are a couple of perspectives from which we might approach this ques-

tion and how it relates to broader issues of frustration. The gap of experience

between the restricted form of interaction the game employs and the spectacle of its

audio and visual presentation (which were all the more impressive in 1983) gesture

toward an ambivalence between player agency and machine interface, an ambiva-

lence we might perceive as resonating with Ngai’s concept of animatedness. To ela-

borate further, the impressive visuals of Dragon’s Lair and its foundation in laserdisc

technology exaggerate this quality by transforming player agency into simply being

able to progress forward in a determined sequence of visual content, something that

we might compare to the ‘‘quick time events’’ of more recent game media that simi-

larly appear to reduce player action to moving an already set sequence forward.

There is an affective gap between player action and the way it is expressed and rep-

resented within the game.5 This restricted form of play and frustrating controls are

where we can locate a sense of ambivalence in the interaction between player and

game.

The Ambivalence of Disobedient Machines

With this sense of ambivalence in use and experience in mind, a frustrating game

might therefore be characterized as a ‘‘disobedient machine.’’ This is when the inte-

gration of human agency into technology begins to diverge in materially experienced

Figure 1. A successfully timed input command in Dragon’s Lair results in an animatedsequence showing the player character Dirk the Daring defeat a dungeon monster.

596 Games and Culture 10(6)

at UNIV OF CHICAGO LIBRARY on October 25, 2015gac.sagepub.comDownloaded from

ways, or, in a more extreme sense, when the relationship between the human user

and game begins to feel incomplete or even adversarial. Following Ngai’s notion

of animatedness, Bukatman (2012, p. 135–136, 146) has used the idea of a disobe-

dient machine to describe traditionally drawn animation by identifying the ways that

animated figures can appear to turn on their creators and pursue their own desires

and agendas. Drawing on examples such as Winsor McCay’s Gertie the Dinosaur

(1914), Bukatman notes the tension between the vitality of the animated figure—

which appears to come to life before our eyes—and the mechanization of human

labor in producing this sense of movement. The expression of agency and life in the

animated figure seems to exceed that of the human agency that produced it even as

that agency begins to feel mechanical or automated.

To return to the metaphor of animation once more, the logic of executing player

agency in a game is one of figuration. This refers to the process of transforming one

action into a visual representation of another. The player pressing a button or moving

a joystick to cause their character to perform an action is not the same thing as that

action itself (as Dragon’s Lair demonstrates), but figuration is what links these two

actions together in a way that normally feels immersive and approaches a sense of

transparency.6 A frustrated notion of figuration can characterize the dynamic of

restricted gameplay and full-motion images of Dragon’s Lair, but it also brings us

back to Ngai’s notion of animatedness and the complicated interplay between

motion, human agency, and technology. It is through the process of figuration that

this dynamic becomes most problematic and material in its expression.

By seemingly interfering with the agency of the player, do ‘‘disobedient’’ game

media that present experiences of frustration emerge as agents of their own in these

situations? The negotiation of agency between the player and the game might feel

more contested that in media such as animation, but this confrontation is not neces-

sarily so much the machine exerting agency of its own so much as the player losing

control over his or her means of expressing his or her control within the operational

logic of the game and its protocols. Actions begin to feel involuntary in motion con-

trol games that have poor (or extreme) sensitivity to user gestures, and player actions

feel meaningless in scripted sequences such as quick time events that have predeter-

mined conclusions that ignore player-made decisions. This is especially pronounced

in games that require the repetition of similar actions over and over. There is a mis-

alignment between the intended actions of the player and the way that the game

machine represents those actions. Control seems to shift away from the player,

although rather than being transferred to the game machine itself, perhaps into a state

of ambivalence that cannot be located in either the player or the game. It becomes

part of the realm of figuration.

In approaching this intersection between frustration, player agency, and

machine–user relationships, this article will focus on two examples of contemporary

game media that can serve as case studies for thinking about some of the ways that

frustration might be experienced. Focusing on a small number of case studies will

limit the amount of work this article can do toward developing frustration as a

Johnson 597

at UNIV OF CHICAGO LIBRARY on October 25, 2015gac.sagepub.comDownloaded from

general concept for thinking about game media, but it is hoped that a greater sense of

precision in analyzing the relationship between agency, figuration, and player–

machine relationships can be achieved this way. The first of these is Steel Battalion:

Heavy Armor (From Software, 2012, Xbox 360), a science fiction vehicle combat

simulator that incorporates both the traditional Xbox 360 controller and the Kinect

motion control system into its player interface. However, similar gestures being used

for multiple motion input commands renders the game’s control schema unstable,

with the player’s actions often being misread by the game in ways that makes it

almost impossible to control the game. The second example is Papers, Please (Lucas

Pope, 2013). In this game, the player assumes the role of an immigration agent in a

fictional, Eastern bloc country during the Cold War. Gameplay consists of repetitive

tasks that mimic the bureaucratic tasks that the character is assigned. This mode of

play emerges a kind of affect labor in which decisions feel serialized and often

appear to have little immediate consequence, a dynamic which can also be experi-

enced as a restriction of the player’s ability to interact with the game.

These case studies will demonstrate different forms of frustration and ambiva-

lence in gaming but will be loosely united through the ways they trouble the act

of play through disruptions of player agency. They, in disparate ways, gesture

toward the ambivalent gap between human players and game machines, which can

often appear to be working in harmony but are frequently interrupted by problems

such as input commands that fail to align player action with character action and

scripted events that negate the significance of player choice. Frustration will there-

fore be approached as the material, experiential quality of this ambivalence. These

two examples are not meant to exhaust frustration as a concept for thinking about

game media and the act of play but rather introduce a set of tools and perspectives

for thinking about issues such as player agency in playing games, repetitive play

forms, and the ambivalent affect of game media.7

Unseen Gestures

Steel Battalion: Heavy Armor (hereafter Steel Battalion) is a first-person perspective

science fiction vehicle simulation game. The player is placed in charge of piloting a

‘‘vertical tank’’ that walks on two legs rather than moving on treads and leading a

crew of ammunition loaders and communications officers. The game divides player

control between the traditional Xbox 360 controller—which is used to manipulate

the controls for the tank such as steering and firing weapons—and the Kinect motion

control device—which is used to facilitate the player character’s interactions with

the inside of the tank, such as turning to face other crew members so that they can

be communicated with, opening hatches, and raising and lowering the viewfinder for

the artillery. Gameplay consists of fighting enemy infantry, vehicles, and other ver-

tical tanks within short missions that are connected by narrative interludes. Mixing

the conventional controller with the Kinect sensor is an innovative approach to this

type of game—and one which built off of the conceit of the elaborate physical

598 Games and Culture 10(6)

at UNIV OF CHICAGO LIBRARY on October 25, 2015gac.sagepub.comDownloaded from

controller its predecessor (2002) was packaged with. However, despite this innova-

tive use of the Kinect, the game was poorly received due to issues with the input sys-

tem received by the infrared sensor.

There are multiple complications with the Kinect-based commands a player

might wish to use within the game. These include more general issues with the

Kinect, such as an unpredictable sensitivity to a player’s distance from the device,

the height of the sensor in comparison to the player, and even ambient qualities such

as lighting that might interfere with the sensor’s ability to accurately read the play-

er’s motions. But more specific to Steel Battalion is an overlapping of similar ges-

tures that are used to activate different in-game actions (Figure 2). As a result, when

the player intends to input one command he or she will often find the game interpret-

ing that action as another. Furthermore, because the visual feedback the player

receives from the Kinect is limited and unreliable, learning how to navigate its see-

mingly illegible sensitivity to different elements takes more time and patience than

many gamers were willing to give. This frustrating element of the game’s control

systems results in errors that force the player to replay a stage over and over again.8

For example, if a player wishes to have his or her in-game character turn his head

to face another member of the mech-tank’s crew, he or she is supposed to raise his or

her right or left hand and make a waving motion, signifying the desire to turn or

rotate the optical perspective of the camera/character. However, this motion is very

Figure 2. Example of Kinect motion controls in Steel Battalion: Heavy Armor. The playerextending a hand upward can lower and raise the periscope to get a better view for aiming orchanging between view modes. The window-in-window image in the upper left is part of theKinect’s infrared display to show the player how his or her actions are being read by thesensor.

Johnson 599

at UNIV OF CHICAGO LIBRARY on October 25, 2015gac.sagepub.comDownloaded from

similar to those used for other actions, such as accessing a control panel within the

tank, pulling the activation level to start the tank’s engine, or opening the protective

shutter at the front of the tank’s chassis. This shutter frequently needs to be opened

or closed to offer a better view of the surroundings and offer protection against

incoming enemy fire. But because of the similarity between the gestures used for

these two different commands and the Kinect’s confusing range of sensitivity to

player movements, a player cannot reliably expect the game to understand what

he or she is trying to perform with any sense of regularity. Even an experienced

player will still face bad input results that thwart his or her intended commands.9

This is also true for gestures that are less similar, such as the command gesture for

instructing your character to lean forward and look out of the viewfinder space

revealed when the front shutter plate is open (pushing toward the Kinect with both

hands) being misinterpreted as opening or closing the front shutter plate (which only

requires one hand).

The result of this confusion between gesture commands is an experience where

the player feels almost as if he or she was losing control of his or her own body.

Many reviewers focused their criticisms of the game on this part of its control sys-

tem, with some going so far as to claim these problems rendered the game unplay-

able. Cork (2012), for example, describes the way that ‘‘nearly every gesture is either

ignored or misinterpreted—often with game-ending repercussions.’’ Shoemaker

(2012) notes that the game itself is not particularly difficult, observing how the

Artificial intelligence (AI) scripts that operate enemy infantry, artillery, and tanks

are unimaginative and predictable, typically remaining stationary while taking the

occasional ‘‘pot shot’’ at the player’s own tank. It is rather the combination of slow

movements of the player’s tank and the faulty Kinect controls that renders the game

frustrating, producing a sense of difficulty that is not rewarding to overcome but

simply an exercise in wrestling with the game’s interface. Online video content sur-

rounding the game also focused heavily on the control set up and its myriad prob-

lems, with let’s play video makers and related forms of YouTube content trying

to incorporate images of frustration into their coverage. This includes simply turning

the camera away from the game and onto the player (so as to show the gestures and

lack of response from the game) or even using picture-in-picture images of them-

selves playing with the Kinect’s infrared projector view that could highlight the ges-

tures they were using during play.

Stupefying Animatedness

To refer back to an idea introduced previously, these moments of miscommunication

between the player and the Kinect device can be taken as an instance of the game

machine becoming ‘‘disobedient.’’ Indeed, the experience of playing the game can

feel like a battle with the control schema, which constantly appears to refuse to coop-

erate with even simple commands. However, if we are to approach this suspending

of player agency as a sign of the ambivalence of control shared between the human

600 Games and Culture 10(6)

at UNIV OF CHICAGO LIBRARY on October 25, 2015gac.sagepub.comDownloaded from

user and the machine, we might consider an alternative suggested by David

Auerbach who has described computers as ‘‘stupid’’ due to their lack of sophis-

tication in interpreting human commands. By this Auerbach means that although

computers often appear to be capable of performing almost any type of function,

they often do not know what type of function they should perform in a given situa-

tion.10 He uses the semantic understanding of search engines as an example for

thinking about how computers (which he uses as shorthand to refer to a variety of

software systems) interpret user input in narrow ways that often fail to understand

the real intention behind a given command or request—semantic understanding is

often advanced, but holistic understanding is comparatively lacking, leading to a gap

between how the user understands his or her input commands and how the computer

or program understands them.11 Crowdsourcing of interpretive labor (Wikipedia)

and relying on meta-data to streamline results in more reliable ways (Google, Ama-

zon.com) have emerged as ways of side stepping some of the problems of computer

stupidity in many mundane tasks, but in many other activities—such as gaming—

computers continue to fail to cooperate as we might expect. Steel Battalion and its

problematic control system is one case for approaching this issue of uncooperative

game media that feels stupid and, perhaps more importantly, stupefying.

For Auerbach, the stupidity of computers is found in the way they understand (or

fail to understand) human language. Hence his focus on tasks such as search engine

queries. However, if we extend this to considering things like gesture that have been

assigned a game-command function, Steel Battalion is a stupid game. But we should

not understand that as merely a pejorative in evaluating this title. Rather, what is stu-

pid about the Kinect functionality in this game is its inability to successfully resolve

the ambiguity of physical gestures that resemble one another. This is compounded

by the way the game requires the player to sit during most moments of gameplay.

Centering so much of the player’s body in a limited amount of space restricts the

Kinect sensor’s ability to differentiate between gestures even further. As a result, the

game loses its ability to interpret with precision or discern overlapping commands,

producing mistranslations of human action that lead to a sense of animatedness in

which the player’s attempts to control the game are misfigurated by the game

machine. This can even be seen in how the game tried to render the arms and hands

of the player character in relation to those of the player, with the character’s limbs

frequently twitching and flickering as it tries to decide what position they should be

held in based on information collected by the Kinect sensor.

To return to the question of user agency in a broader sense, what this quality of

stupidity in the game results in is that the user’s actions begin to feel involuntary.

Not in the sense that their body is acting without their control but that through the

game’s frustrating way of misinterpreting those actions, the player has to constantly

correct his or her own bodily movements through repetitions of the same gestures.

Those actions begin to lose their intended meaning and become part of some other

kind of performance activity in which the player is no longer ‘‘in control.’’ Although

we might joke that this results in a reversal in which the player is no longer

Johnson 601

at UNIV OF CHICAGO LIBRARY on October 25, 2015gac.sagepub.comDownloaded from

controlling the game but the game is actually controlling the player, there is a sense

in which the human user is figuratively mechanized or even automatized by the way

the human–machine interface dismantles the logic of subordination and reciprocity

that informs how game controls are organized. To put it in other words, the form of

embodiment that the human–machine interface would normally suggest is trans-

formed in a way that obstructs the agency of the human in favor of the

machine—the ensemble of human and technological actions.12 If we think of the act

of play as a kind of animation— or animatedness—in which the player performs a

certain kind of life or vitality into the game world or sprite characters, the contested

agency of the frustrating game experience is one in which the animation is being per-

formed by and upon the player in an entwined, ambivalent way that, rather than giv-

ing life to the figures within the game, mechanizes the player through acts of

repetition and misfiguration.13

To extend this affinity between animation and gameplay further, we can turn to

how Crafton (2013, pp. 58, 59) has described the multiple registers of agency that

can be perceived in traditional animation. He observes how animated figures appear

to possess a ‘‘free agency’’ of their own through the way that they move but that this

is also a figuration of the animators’ control and even the perceptual agency of the

viewer. Game media can sometimes behave in a similar way, in that while most in-

game actions by the player character are performed by the player (and essentially

reperformed by the avatar or character), the in-game representations of physics are

often slightly ‘‘off’’ in a way that makes in-game, player-operated actions slightly

excessive of what the player expected or intended; hence the inherent ambivalence

of such machines. This is also true for the Kinect, which does not perform a literal

one-to-one mapping of the player’s gestures. But to return to animation, for Crafton

(2013, p. 70), the complicated distribution of agency between animated figure, ani-

mator, and audience means that both the animated figures and the animators them-

selves can each claim a kind of ‘‘autonomous agency.’’ Autonomy seems to recede

in the case of a game like Steel Battalion, which simultaneously relies on player ges-

tures to direct in-game actions but also mistranslates those gestures in a way that pro-

duces something different. The game appears as both subordinate to the human

user’s actions and approaches a horizon of autonomy through its frustration of the

agency of the player.

The frustration of Steel Battalion’s Kinect controls comes through this seeming refu-

sal to perform as expected—we try to tell the game to do one thing, but it does something

else. Through these ambivalent, affect gaps between our actions and the way the game

figuratively represents them, we are reminded of the limitations of our ability to control

a game and our ability to interface with its control schema. This ambivalence in inter-

facing with the game can also be found in scenarios where the decisions that players

make begin to lose a sense of significance and in which the act of play becomes repe-

titive and work like. The frustration of becoming automatized again seeps through,

but perhaps in a more mundane, irritating way than the spectacular aggravation of

Steel Battalion. This dynamic will be the focus of the next section.

602 Games and Culture 10(6)

at UNIV OF CHICAGO LIBRARY on October 25, 2015gac.sagepub.comDownloaded from

‘‘Glory to Arstotzka’’

Lucas Pope’s Papers, Please is an independently produced computer game that was

released for Windows and Apple OS in 2013 and Linux in 2014. Rather than being

an action-oriented game in which the player is able to move a character or vehicle

through a three-dimensional game world, the majority of Papers, Please restricts the

player to a single, cramped space—that of an immigration booth at the border of an

imaginary Eastern European country during the Cold War. Interlude sequences will

show the player newspaper headlines, short narrative sequences, and explain the

effect of their daily earnings on their household’s well-being. Interactive elements

of the game, however, are generally limited to what happens within the confines

of the immigration booth and the player character’s encounters with those trying

to enter the fictional country of Arstotzka.

In comparison to Steel Battalion, the game mechanics and controller interface of

Papers, Please appear quite simple. Most actions—such as selecting documents that

have been passed to the player character, opening and closing the booth gate, and

operating the stamps used on passports—are handled through moving the mouse cur-

sor and clicking on the desired object. Additions to the player character’s booth that

allow some of these functions to be ‘‘hot-keyed’’ to the keyboard can be unlocked

and purchased through the course of playing the game, but the mechanical elements

of play remain quite limited.14 As such, although the game does not have issues of

frustration arising from controller complexity as a game like Steel Battalion can,

restrictions on the player’s ability to interact with the game world introduces new

ways of considering how obstructions to player agency can be felt. That being said,

an important distinction to be made between Papers, Please and a game such as Steel

Battalion is that the experience of frustration is one that is deliberately woven into

the act of play as part of the game’s mixing of work and play activities.

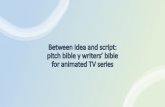

The narrative premise of the game puts the player in the position of performing

repetitive, tedious tasks as an immigration agent. Gameplay consists of checking

passports, work visas, and other documents for their authenticity. This includes con-

sidering elements such as expired dates of issue, accuracy of the issuing city, and for

inconsistencies between the documents and the individual presenting them (Figure

3). Based on this information, the player must then decide to either accept the indi-

vidual for entry or deny them passage. Mistakes in judging a document’s veracity

will result in warnings, and beginning with the third mistake made on a single day,

the player character’s take home wages will be docked for each individual wrongly

admitted or denied. Nonplayer characters such as would-be immigrants and guards

will attempt to bribe the player to gain entry, earn extra income from detaining

suspicious-looking entrants, or even plot a conspiracy to overthrow the government

of Arstotska. Getting caught taking bribes or passing materials for nongovernment

factions can result in fines and even lead to a premature ‘‘game over’’ ending. Many

nonplayer characters that appear in the game are procedurally generated and have no

long-term impact as individuals (save any penalty that may come from wrongly

Johnson 603

at UNIV OF CHICAGO LIBRARY on October 25, 2015gac.sagepub.comDownloaded from

admitting or denying them entry), but there are many who are scripted and have

recurring roles that play into the larger narrative concerns of the game. These are not,

however, always obvious when first encountered.

Papers, Please can be a frustrating game, but perhaps in a way that is more obvi-

ously allegorical or even critically engaged than Steel Battalion. Reviews of the

game and its general reception account for this and take its frustrating elements into

consideration.15 The content of the game is, in one sense, a simulation of bureau-

cratic work, so many of the tasks that the player will be asked to do to progress

through the game will be tedious and unrewarding. Many encounters with nonplayer

characters will be very similar, with the character appearing and offering his or her

documents, which must then be checked against an ever increasingly complex sys-

tem of contingencies. These must all be handled manually by the player by operating

stamps, filing away reference materials, and taking and returning documents. The

presentation of the game amplifies this experience, due in large to the affinity

between the limited aesthetics of the game and its restricted mode of gameplay. Text

appears pixilated and can be difficult to read, causing even simple tasks such as con-

firming the accuracy of an issuing city for a passport more time consuming that they

feel like they should. And unless the player has a good memory or takes notes, refer-

ring to in-game documents that must be retrieved, opened, and searched for the right

Figure 3. A procedurally generated interaction with a nonplayer character in Papers, Please.At the top of the screen we see a bird’s eye view of the outside of the booth and surroundingarea, while the lower area shows both the booth window (left) and desk with documents(right). In this case, the nonplayer character is attempting to pass through the booth with anexpired entry ticket.

604 Games and Culture 10(6)

at UNIV OF CHICAGO LIBRARY on October 25, 2015gac.sagepub.comDownloaded from

information will be necessary, using up more time and leading to more strained

reading.

The player is also given limited space to arrange his or her desk, so as documents

begin to pile up, finding places to keep distinct pieces of information can become a

source of irritation—all compounded by the fact that all documents of a given type

have the same cover when they are not being examined. The management of space

and discrete files thus approaches becoming overwhelming at times, which is again

exaggerated by the pressure to accomplish tasks as quickly as possible so as to bring

home a livable wage. Working in tension against the pressure to complete tasks as

quickly as possible is the consequence of decisions the player will make. Long-term

elements such as choosing an option that will punish the player further down the nar-

rative tree—such keeping a stash of money rather than burning it—can result in

game over screens that force the player to go back to the beginning of a previous day

and replay until they find the point at which they can begin anew.

What kind of game is Papers, Please? It shares many elements with simulation

games, such as the use of allegorical scenarios for its content, the emphasis on man-

agement of in-game objects, and a ‘‘real-time’’ system of dealing out costs and

rewards to the player. But we can also think of it as a type of affect labor game, one

that inhabits the overlapping space between work and play and intersects with the

trend toward gamification of work and the extraction of labor from leisure activities.

It is particularly through the conflation of play with low-wage, low-skill work that

relies on repetitive and routine heavy activities centered around human interaction

that Papers, Please resonates with this notion of affect labor and, more generally,

contemporary develops within service industry economies.16 There is a resonance

between the repetitive tasks this type of game employs with the scripted interactions

common in fields such as customer service that rely on sequencing of actions that

Deborah Cameron has described as ‘‘top down’’ in their organization (Cameron,

2008). In the call centers that Cameron analyzes, this sequencing of speech is one

that is designed by managers and other superordinate agents who then direct workers

to perform these routines in their day-to-day interactions with customers. As with

Papers, Please and its ambivalent player–machine relationship or repetition, this ges-

tures toward a transference of agency away from the individual and toward the insti-

tutionalized structure of command and routinized actions that must be performed

over and over.

Affective Agency

David Auerbach has written on Papers, Please in comparison to games such as The

Walking Dead (Telltale Games, 2012a), which he analyzes within the logic of quick

time events. Quick time events are narrative sequences in games—often rendered

with the game’s normal graphics engine rather than as a cut scene using fully ren-

dered images—that allow for a limited amount of player interaction, typically in the

form of prompts to press a button at a certain point to trigger the next part of the

Johnson 605

at UNIV OF CHICAGO LIBRARY on October 25, 2015gac.sagepub.comDownloaded from

narrative sequence. Dragon’s Lair might serve as a precursor to this trend in more

recent titles, such as the opening sequence of Uncharted 3: Drake’s Deception

(Naughty Dog, 2011). This sequence features a bar fight in which the player is told

to press certain buttons to initiate dodges, punches, and other actions within the

fight, although they are not controlling the character’s movements or more general

responses. This type of gameplay is, as Auerbach (2013) describes, not one that

allows for an expression of player choice but rather provides a way of advancing the

story based on limited types of player action. You can press the correct button at the

right time, which will advance the sequence, or fail to match things up, which will

usually result in a repetition of a similar segment that leads the player to the same

prompt. Auerbach notes that quick time events introduce player agency into narra-

tive sequences of games but qualifies this by noting the type of agency they allow for

is not the one based around player choice or player-initiated decision making. It is

rather part of a logic of scripted forms that can be advanced but not changed or at

least not changed in significant ways. The inevitability of events such as character

death at the conclusion of The Walking Dead—which uses the vibration function

of the controller to make the player ‘‘feel’’ the emotional trauma of pulling the trig-

ger—is taken as a model for thinking of how quick time events can initiate narrative

immersion and the feeling of player agency even when the game is limiting the type

of experience the player can have.17

This can be contrasted with the way that Papers, Please integrates a limited form

of player agency into its narrative conceit of bureaucratic labor. Although The Walk-

ing Dead presents an intricate narrative with far-reaching emotional consequences

for the player, the narrative of Papers, Please is one that generally happens around

the player character and even sometimes without the player’s immediate knowledge.

The player has many choices to make, and some of these affect the larger stakes of

the game’s narrative universe. These decisions, however, often appear inconsequen-

tial at the time they are made due to their obscurity within the behind the scenes

game of political chess being waged by government agents and terrorist spies. On

one hand, this means that while The Walking Dead and games like it that rely on

quick time events attach emotional stakes on what are essentially inconsequential

decisions (i.e. you get the same ending no matter what you do), Papers, Please offers

a far more restricted form of emotional payoff, despite the potentially meaningful

choices the player might be deciding between.

Papers, Please uses a restricted framework to organize how the player can interact

with the game world they inhabit. In contrast to the ‘‘open world’’ games of the

Grand Theft Auto series and similar titles, Papers, Please offers no horizon of

play—the world is dully colored, with nothing available to the player beyond the

inside of the booth and the surrounding area. It mechanizes the act of play through

repetitive acts that, by playing out roughly the same, instill the feeling of seriality of

anonymous segments that blend together. Take documents. Check for errors. Deploy

stamp arm. Reject or accept. Retract stamp arm. Return documents. Call next in line.

Repeat. This repetition is frustrating not only because of its seemingly laborious

606 Games and Culture 10(6)

at UNIV OF CHICAGO LIBRARY on October 25, 2015gac.sagepub.comDownloaded from

nature of mixing work with play, but because it mechanizes the player’s ability to

act. The act of play becomes an act of administration, of laboring.

This too presents a form of animatedness for us to consider. However, unlike

Steel Battalion’s more explicit misfiguration of player control through the faulty

gesture commands of the Kinect, Papers, Please relies more on the automatization

of player action, the mixing of work and play, and the dynamic through which those

qualities trouble the feeling of user agency. In other words, rather than spectacular-

izing the ‘‘agitated things’’ that inhabit stop animation for Ngai and which we can

perceive in the stupidfying controls of Steel Battalion, Papers, Please focuses on the

‘‘deactivated persons’’ of those who live with repetitive work and obstructed agency.

The seriality of each instance of player choice contrasts with the more obvious

drama of Steel Battalion and contributes to a different way of understanding fru-

strated agency and ambivalence in human–machine interfaces. The perspectives

from which these two games evoke affects of frustration are thus quite different even

as they share qualities of thwarted player agency, repetition, and a figurative

mechanization of the player.

Animating Agency

As we have seen, each of these games produce affects of animated frustration in par-

ticular ways. Frustration can arise from faulty controls that obstruct the player’s abil-

ity to control the game while minimalist gameplay that limits what the player can

accomplish. The temporality of frustration that players might feel is also quite dif-

ferent. In Steel Battalion, frustration is felt in sudden, punctuated moments when the

nonalignment between player action and figurative representation within the game

interfere with our ability to interact with the game as desired. Papers, Please is frus-

trating in a constant way—perhaps similar to what Ngai would describe as irritation

due to the repetitive elements of playing, the tedium of navigating its limited control

scheme, and its opaque system of narration. It is something we might feel as a con-

stant, continuous state that envelops us rather than momentary interruptions. As

such, not only is the type of frustration that players will experience differ between

these titles, but also the way that players will experience it also varies significantly.

There are, however, similarities that should be recognized. Repetition is some-

thing that haunts each game and contributes to its production of frustration, whether

it be forcing the player to repeat similar gestures in Steel Battalion until the game

recognizes what the player is trying to do or the bureaucratic working play of Papers,

Please. This sense of repetition is also how frustration has been reclaimed as humor

in online communities, such as in ‘‘let’s play’’ videos that edit together strings of

failed gameplay in rapid succession or live broadcasts on Twitch.tv and Hitbox.tv

that feature players trying over and over to complete the same level or goal within

a game. We can even see this type of laughing at frustration in televisual media such

as the Japanese variety show GameCenter CX (Fuji, 2003) or YouTube series like

‘‘The Angry Video Game Nerd,’’ which focus on characters being flustered by

Johnson 607

at UNIV OF CHICAGO LIBRARY on October 25, 2015gac.sagepub.comDownloaded from

difficult games and frustrating, uncooperative game technologies like faulty control-

lers and tangled wires needed to hook an obscure console up to a cathode ray tube

television set. These types of visual entertainment are—despite their humor—

perhaps also frustrating in an abstract sense in that they blur the line between

play and labor in a way that is increasingly tied to online leisure activities. This

is not to diminish the ways in which these types of media recover frustration as

laughter, but we can also consider this as an extrapolation of the relationship

between frustration and suspended agency in the sense that their producers

transform their own playing of games into a kind of work or job but also in their

translation of the audience’s attention into revenue based on viewcounts and

advertising returns. That the very act of viewing through online media players

such as YouTube can be appropriated as labor might signal another way in

which agency becomes obscure or frustrated in contemporary media culture.

This transformation of play or vision into labor follows a similar logic to an

increasing reobjectification of the player. A game like Steel Battalion transforms the

player’s body into an almost reverse puppet, both being commanded by the player’s

gestures but also approaching a feeling of animating the player through the need to

continuously reperform key gestures. The repetitive, bureaucratic work play of

Papers, Please also envelops the player in rigid, mechanical, and limiting forms of

play that figurate the player as a cog in a machine, anonymous and insignificant.

Schaffer (2007) has claimed that animation can function as a ‘‘profound allegory

of the relationship between humans and machines’’ due to the dynamic between the

controlled labor of production and the wild, almost rebellious forms of movement

and life that animated figures possess.18 This article hopes to pose a similar way

of thinking about games as machines, which intersect with, overwhelm, and expand

the experience of human agency in disparate ways that might also show us some-

thing about the relationship between humans and machines. Through these moments

of obstructed or suspended agency of players, games become ‘‘ugly’’—or even ‘‘stu-

pidifying’’—through their ambivalent qualities that interface human users with tech-

nological forms in ways that do not align as expected.

What should be isolated in the analysis of frustration in game media is this

ambivalence between the player and the game, the space where agency becomes

thwarted, and how the figuration of the game runs wild in spite of the player’s best

efforts, leading to a sense of animatedness. This sense of animatedness is indicative

of the feeling that we are losing control—not just over the games we play, but over

other parts of our social and technologically mediated lives. Frustration is therefore

not just a sign of games functioning in uncooperative ways that can annoy and dis-

courage a player but of the affective dynamic produced through the interfacing of

human agency with the logic of the game machine.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research,

authorship, and/or publication of this article.

608 Games and Culture 10(6)

at UNIV OF CHICAGO LIBRARY on October 25, 2015gac.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of

this article.

Notes

1. In some cases, these sorts of involuntary game machine events can actually be exploited

by players. The slowdown that occurs at certain points of the Super Nintendo console title

Super Ghouls ‘n Ghosts (Capcom, 1991) is one such example which, while interfering

with the player’s ability to interact with the game for most, actually allowed skilled play-

ers to avoid enemy attacks and time their own attacks more reliably.

2. Loading screens, being forced to wait in matching-making lobbies during online play, and

issues of latency and disconnection in online games are other areas for considering frus-

tration in game media. Those are unfortunately beyond the scope of this article, which is

focusing on experiences of frustration within ordinary states of gameplay.

3. In Ngai’s argument, this is also tied to racially or ethically marked characters in literature and

visual media. This article’s use of her concept will shift the way the term can be deployed to

think about human–machine relationships. Bukatman invokes this concept in regard to ani-

mation in Poetics of Slumberland, which also informs how this article is repurposing Ngai’s

scholarship for thinking about game media (Bukatman, 2012, pp. 20–21).

4. The conversion of some arcade games to home console has complicated this quality of

games such as Dragon’s Lair. On one hand, home consoles often allowed for save files

or featured passwords that would allow a player to skip ahead in the game. This relieved

the player of the need to constantly replay the same early stages over and over to pick up

where they last left off. On the other hand, games that were designed with an arcade con-

troller in mind did not always feel intuitive on a home console, which did not always have

the same number of buttons, frequently used a directional pad instead of a joystick

(although joystick controllers were often available), and sometimes had less computa-

tional power to render game sprites and environments.

5. Galloway (2012) describes what he calls ‘‘interface effects’’ in a similar way, noting how

social life often feels increasingly incompatible with its own expression in contemporary

visual media. Ngai and Galloway are writing about similar concerns in visual and narra-

tive materials but from different perspectives. That begin said, Galloway’s conceptuali-

zation of the interface as a process rather than a thing and as a threshold between different

realities offers a provocative model for considering how user–machine interfaces in game

media shape player agency in particular ways.

6. Crafton (2013, pp. 22–36) uses figuration to describe animated performance and the dra-

matic irony of an animated figure’s composited performance that has been brought

together by the labor of the animator, the voice of the actor, and the vitalizing mode of

watching assumed by the audience.

7. An earlier version of this article also included a discussion of genre expectation in games

and how the frustration of player agency could be felt through moments when games

diverge from or betray player expectations. This was centered on ‘‘sandbox’’-style games

Johnson 609

at UNIV OF CHICAGO LIBRARY on October 25, 2015gac.sagepub.comDownloaded from

such as the Elder Scroll series that, through elements such as ‘‘side quest’’ diversions and

exploration of the game world, granted players the ability to interact with the game space

in what feels like an unfettered way. The imposition of time limits in missions in Dead

Rising 2 (Capcom, 2010) was used as a model to consider how player agency could feel

restricted by diverging from genre conventions, creating a tension between offering the

player the experience of an open-world environment while also denying them the ability

to actively enjoy it (lest they risk running out the mission clock). Tulloch (2010, 2014)

has discussed the relationship between player agency and rules in games and interactivity

in game media.

8. This is compounded by the load times a player must sit through while waiting to restart

and the generally short amount of time one actually plays a single mission. Missions

rarely last more than a few minutes when successfully completed (failure also happens

quickly), but the game will still take dozens of hours to complete for most players due

to being forced to replay failed missions, the near-constant quick-time events and cut

scenes that break up the action, and the numerous loading and menu screens.

9. Especially difficult to control is the game’s use of the viewport screen, which is accessed by

having your character lean forward to look at the armored shutter at the front the tank. The

game is played with the player sitting down for most actions, but the Kinect is unable to

distinguish between different sitting postures and will continuously move the player in and

out of viewport mode even when the player is not making hand gestures and sitting still.

10. Auerbach (2012a). Ian Bogost (2012, p. 15) also describes machines as ‘‘dumb’’ and

‘‘insentient’’ in the way to human interaction.

11. In a separate piece Auerbach describes a similar effect with text-based adventure games,

which he characterizes as appearing to understand English in a restricted way. However,

he also notes that this appearance of understanding is essentially a ‘‘ruse’’ in that the

grammatical forms the game could make sense of were quite limited (Auerbach, 2012b).

12. Here I am glossing on Felix Guattari and Giles Deleuze’s concept of the ensemble in

Chaosmosis (1995, p. 33) and A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia

(1987, p. 327–329).

13. Jones discusses the defamiliarization of avatar/player relation in recent slapstick games,

focusing on ‘‘motor tactics’’ and a hyperbolic control over avatar bodies in games such as

Octodad: Dadliest Catch (2014). These games gesture toward a similar difficulty in con-

tro, but invite reactions of humor rather than frustration due to their presentation (Jones,

2014).

14. Within the game these are explained as ‘‘upgrades’’ to the player character’s booth. How-

ever, because the keys that are used to operate them are placed so far away from one

another they are not immediately—or intuitively—useful. This is part of the game’s

humorous take on bureaucracy, which even in its ‘‘improved’’ forms feels awkward and

obstructive.

15. See, for example, Hornshaw (2013) and Hoggins (2013). Hornshaw notes the way respon-

sibility is expressed through the game’s method of punishing and rewarding the player,

while Hoggins notes the ways it flirts with failure while juggling its moral dilemmas and

dramatic stakes through the player’s actions.

610 Games and Culture 10(6)

at UNIV OF CHICAGO LIBRARY on October 25, 2015gac.sagepub.comDownloaded from

16. For more on affect labor see Hardt (1999)

17. Auerbach (2013) compares the ‘‘emotional intensity’’ of quick time events such as the

one found in The Walking Dead with a general decline in the emotional involvement

in other realms of technologically mediated life such as warfare. Considering technolo-

gies such as drones, he observes that ‘‘while the armed forces seek to remove soldiers

from realities in which sudden bursts of empathy and humanity might interfere with the

strict differentiation of friend and foe, using technology to vastly increase geographical

distance between friend and foe, QTEs seek to plant a greater immediacy into an artificial

situation and thus manipulate the player’s emotions in the opposite direction. Fiction is

becoming more emotionally loaded even as reality is becoming less so.’’

18. Schaffer, W. (2007). Animation 1: The Control Image. In A. Cholodenko (Ed.), The illu-

sion of life II: More essays on animation (p. 463). Sydney, Australia: Power Books.

Quoted in Bukatman (2012, p. 136).

References

Auerbach, D. (2012a). The stupidity of computers. Nþ1, Machine Politics, (13). Retrieved

August 1, 2014, from https://nplusonemag.com/issue-13/essays/stupidity-of-computers/

Auerbach, D. (2012b). Choose your own formalism. The White Review. Retrieved August 3,

2014, from http://www.thewhitereview.org/features/choose-your-own-formalism/

Auerbach, D. (2013). The quick time event. The White Review. Retrieved August 5, 2014,

from http://www.thewhitereview.org/features/the-quick-time-event/

Bogost, I. (2012). Alien phenomenology, or, what it’s like to be a thing. Minneapolis: The

University of Minnesota Press.

Bukatman, S. (2012). The poetics of slumberland: Animated spirits and the animating spirit.

Berkeley: The University of California Press.

Cameron, D. (2008). Talk from the top down. Language and Communication, 28, 143–155.

Cork, J. (2012, June 19). Gameplay goes AWOL in mech-combat revival – Steel Battalion:

Heavy armor.’’ Game Informer. Retrieved July 31, 2014, from http://www.gameinfor-

mer.com/games/steel_battalion_heavy_armor/b/xbox360/archive/2012/06/19/gameplay-

goes-awol-in-mech-combat-revival.aspx

Crafton, D. (2013). Shadow of a mouse: Performance, belief, and world-making in animation.

Berkeley: The University of California Press.

Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1987). A thousand plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia

(B. Massumi, Trans.). Minneapolis: The University of Minnesota Press.

Galloway, A. (2012). The interface effect. Cambridge, MA: Polity.

GameCenter CX [Television series]. (2003). Tokyo, Japan: Fuji Television.

Guattari, F. (1995). Chaosmosis: An ethico-aesthetic paradigm (P. Bains & J. Pefanis, Trans.).

Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

Hardt, M. (1999). Affective labor. Boundary 2, 26, 89–100.

Hoggins, T. (2013, August 28). Papers, please review. The Telegraph. Retrieved August 18,

2014, from http://www.telegraph.co.uk/technology/video-games/10271115/Papers-Please-

review.html

Johnson 611

at UNIV OF CHICAGO LIBRARY on October 25, 2015gac.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Hornshaw, P. (2013, October 14). Border (double) crossing. Gamefront. Retrieved August 18,

2014, from http://www.gamefront.com/papers-please-review-i-am-the-law/2/

Jones, I. (2014, March 22). The obstinate avatar: On (the lack of) bodily intelligence in recent

slapstick videogames. Paper presented at the Society for Cinema and Media Studies

Annual Conference, Seattle, WA.

Juul, J. (2013). The art of failure: An essay on the pain of playing video games. Cambridge:

The MIT Press.

McCay, W (Director). (1914). Gertie the Dinosaur [Film]. Brooklyn, New York.

Ngai, S. (2005). Ugly feelings. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Pope, L. (2013). Papers, Please [Steam].

Schaffer, W. (2007). Animation 1: The control image. In A. Cholodenko (Ed.), The illusion of

life II: More essays on animation (pp. 456–485). Sydney, Australia: Power Books.

Shoemaker, B. (2012, June 19). Giant bomb review: Steel Battalion – Heavy armor. Giant

Bomb. Retrieved July 31, 2014, from http://www.giantbomb.com/reviews/steel-batta-

lion-heavy-armor-review/1900-502/

Steel Battalion [Xbox]. (2010). Tokyo, Japan: Capcom.

Super Ghouls ‘n Ghosts [Super Nintendo Entertainment System]. (1991). Tokyo, Japan:

Capcom.

The Walking Dead [Steam]. (2012). San Rafael, California: Telltale Games.

Tulloch, Rowan. (2010). A man chooses, a slave obeys: Agency, interactivity, and freedom in

video gaming. Journal of Gaming and Virtual Worlds, 2, 27–38.

Tulloch, Rowan. (2014). The construction of play: Rules, restrictions, and the repressive

hypothesis. Games and Culture, 9, 335–350.

Uncharted 3: Drake’s Deception [Playstation 3]. (2011). Santa Monica, California: Naughty

Dog Inc.

Author Biography

Daniel Johnson is a PhD candidate at the University of Chicago in the departments of Cinema

and Media Studies and East Asian Languages and Civilizations. His article ‘‘Polyphonic/

Pseudo-synchronic: Animated Writing in the Comment Feed of Nicovideo’’ was published

in Japanese Studies.

612 Games and Culture 10(6)

at UNIV OF CHICAGO LIBRARY on October 25, 2015gac.sagepub.comDownloaded from