An Analysis of the Socio-Technical Gap in Social Networking Sites

Transcript of An Analysis of the Socio-Technical Gap in Social Networking Sites

619

Copyright © 2009, IGI Global, distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of IGI Global is prohibited.

Chapter XLIAn Analysis of the

Socio-Technical Gap in Social Networking Sites

Tanguy CoenenVrije Universiteit Brussel, Belgium

Wouter Van den BoschKatholieke Hogeschool Mechelen, Belgium

Veerle Van der SluysIndependent Scholar, Belgium

ABSTRACT

This chapter views social networking sites as supporting social capital and the advantages which derive from it, namely emotional support, information exchange, and a capacity for concerted action. Social capi-tal is subdivided in three types: relational, cognitive, and structural. The authors derive a number of social needs from these types of social capital and discuss how the social networking sites considered in this study support or fail to support these needs with technical features. The contributions of this chapter include the dimensionalisation of the socio-technical gap in social networking systems and a discussion of elements that reside in the gap.

It is hardly possible to overrate the value… of placing human beings in contact with persons dissimilar to themselves, and with the modes of thought and action unlike those with which they are familiar… Such com-munication has always been, and is peculiarly in the present age, one of the primary sources of progress.

—John Stuart Mill (1848)

620

An Analysis of the Socio-Technical Gap in Social Networking Sites

INTRODUCTION

This paper investigates socio-technical systems. The constituents of these socio-technical systems are people and technology. More precisely, users pursue a certain goal and must therefore interact with others through technology. This introduces a social dimension in the system1. As the social interaction takes place through the technology, the technical dimension mediates the social dimension. The social dimension also influences the technical dimension, as the interactions between the users of the system create a number of social needs which the technical dimension must meet. If the social needs are not met, we refer to this discrepancy between social and technical dimensions as the socio-techni-cal gap or, as Ackermann defines it:

The social-technical gap is the divide between what we know we must support socially and what we can support technically. (Ackerman 2000, p179)

As, in our perspective, the influence runs in both directions, between the social and the technical di-mensions of the system, it can be said that the social and the technical component co-evolves.

We therefore propose to expand the definition offered by Ackermann of the socio-technical gap by stating that there are also social practices which emerge, based on the opportunities proposed by the technology. In the type of socio-technical system under study—internet technology and the interac-tion it supports—new technologies are appearing every day. Still, it is not always clear how social practices can adapt to the technical possibilities in order to better realize the social goals of the system’s participants. Whereas this constitutes an interesting research theme in itself, this chapter only investigates the socio-technical gap regarding the way the technology meets the needs of the social component.

SOCIAL NETWORKING SITES AS SOCIO-TECHNICAL SYSTEMS

In the last decade, social networking sites (e.g. Facebook, mySpace, linkedIn, Orkut, Xing, etc…) have become among the most popular internet ap-plications. In a recent overview, Boyd & Ellison (2007) define them as:

web-based services that allow individuals to (1) construct a public or semi-public profile within a bounded system, (2) articulate a list of other users with whom they share a connection, and (3) view and traverse their list of connections and those made by others within the system. (Boyd & Ellison 2007, p 2)

This is a very basic definition, which to our knowledge is applicable to all existing social net-working sites. Still, most sites provide much more than these 3 basic functions. Also, the definition does not point to the socio-technical nature of social networking sites, as there is no mention of the interaction which commonly takes place on these sites. We therefore propose to apply another definition:

Social networking systems are web-based systems that aim to create and support specific types of relation-ships between people. (Coenen 2006, p 75)

This definition alludes to social interactions, as this is necessary to create and maintain social rela-tionships. While this definition seems more general than the one mentioned before, it more reflects the interactive nature of social networking systems.

In previous work, three functional subsystems have been distinguished that apply to social net-working sites: the individual subsystem, the dyadic subsystem and the group subsystem (Coenen 2006, Coenen et al 2006). The individual subsystem contains the functionalities which pertain to the individual. This includes the way she presents herself to others and settings which the individual

621

An Analysis of the Socio-Technical Gap in Social Networking Sites

can make with regards to the way she wants to use the system. Thus, the socio-technical system is composed of the individual as she interacts with the system and with herself.

The dyadic subsystem contains the functionalities through which a person can manage the attributes of his relationship with another person. Among many features, this includes the ability to add a person as a friend, to label another person as “sexy” or to send a message to someone else. Here, the socio-technical subsystem is composed of 2 people and the technol-ogy over which and with which they interact. The whole of the dyadic spaces can be traversed, creating the ubiquitous social network representation. Social networks in social networking sites are represented as egocentric networks, in which the user is at the center of his own community. This reflects a trend coined by Wellman (2003), who claims that social life is moving away from community-based life towards networked individualism.

Finally, the group subsystem includes the tech-nical means to interact with groups of people. This subsystem contains e.g. public blogs and forums. This socio-technical subsystem is composed of a group of people and the technology over which and with which they interact.

The above definition by Boyd & Ellison (2007) only describes the individual and dyadic subsys-tems. Granted, these are the areas in which social networking sites distinguish themselves from prior groupware or computer-supported collaborative work systems. Still, most social networking sites also provide heavily-used group subsystems. Providing a picture of social networking sites that neglects the group as a socio-technical system seems to be an impoverished version of the facts, especially as the group level has an influence on the other subsystems in the whole.

PURPOSE OF THE SOCIO-TECHNICAL SYSTEMS

In order to better understand the nature of the socio-technical components of social networking

sites, it is necessary to discuss the purpose of the constituents in the three above mentioned subsys-tems. It was explained before that the systems as we see them have technical and social components. The subsystems are in fact created by the technical system components and the number of people that can interact with each other and with the technical system component. The nature of the subsystems thus derives from the technical component. It can therefore be said that the purpose of the technical components of each subsystem is to generate the subsystem in itself. For example, the purpose of the user profile in the individual space is to provide the functionality of the identity space.

This is different for the human components of the socio-technical subsystems. Social networking systems create and maintain relationships between people. These relationships, together with the ad-vantages that derive from social relationships are currently being studied under the label of social capital, defined as

the sum of the resources, actual or virtual, that accrue to an individual or group by virtue of possessing a durable network of more or less institutionalized relationships of mutual acquaintance and relation-ship. (Bourdieu & Wacquant 1992, p119)

In the light of the previously proposed definition, which sees social networking systems as creators of social relationships, it follows that the core pur-pose of social networking systems is to create and maintain social capital.

But why would one want to do this? Resnick (2001) categorizes the resources which accrue from relationships over an information system as emotional wellbeing, information and an improved capacity for concerted action. We will assume that these are the prizes that can be gained by interacting in the offline social mode and that they in part consti-tute the motive for interacting on social networking sites. Indeed, maintaining the social relationships from which social capital ensues is one of the most obvious added values of social networking sites.

622

An Analysis of the Socio-Technical Gap in Social Networking Sites

Therefore, we believe social networking sites should be discussed in relation to social capital.

The degree to which the social capital related functionalities on offer in social networking sys-tems meet the identified needs, will determine the socio-technical gap in the context of this paper. Combining these purposes with the presented subsystem approach to social networking sites will allow us to provide a more fine-grained approach to the social needs in social networking systems. In the remainder of this section, we discuss various purposes and the social needs which derive from these purposes.

Deriving Emotional Wellbeing from Interaction with Other People

One of the main reasons why social networking sites are currently being used is to derive a sense of wellbeing from interacting with others. A large part if not the majority of current social networking site users are aged under 20, a populating group well known for having special needs in terms of emotional wellbeing. The success of systems like Facebook is sometimes attributed to the fact that many students in the United States need to leave the geographic area in which they grew up to go and study at uni-versity. This is not always an easy process, as the youth need to leave behind the social networks on which they relied in earlier years. Social networking sites make it easier to keep in touch with a larger and more dispersed social network, from which people can derive emotional wellbeing, attenuat-ing the “friendsickness” effect (Ellison, Steinfield & Lampe 2007).

Exchanging Information with Other People

Another reason why people use the networking features of social networking sites is to exchange information. The information benefits that can be derived from social capital have been widely studied (e.g. Granovetter 1973, Hansen 1999, Burt 2000). This is one of the elements driving the networking

practices of people in various industries, as they come together to meet others at fairs, receptions, club meetings, etc…

For example, Ellison, Steinfield & Lampe 2007 report that people are using Facebook to “crystallize relationships that might otherwise remain ephem-eral”. They suggest that through Facebook, it is easier to leverage the informational advantages of having weak tie conduits into social clusters, other than the ones a person belongs to. In other words, they propose that using a social network site makes it easier to ask things to people you don’t know well and would otherwise not ask anything of.

An Improved Capacity for Concerted Action

Many complicated activities require contributions by a number of people. It will be easier to complete such activities if social capital exists, prior to start-ing the executing of complex group actions. Social capital can allow groups to overcome some costs of cooperation, like a lack of trust or common understanding.

An example is a software development project. Imagine two cases: one with pre-existing social capital and one without. In both cases, a team of people is assembled to work on the software develop-ment project. In the case where social capital does not pre-exist, issues may occur regarding trust. For example, people may not reveal their own ideas to others, from fear that others in the team will steal their idea. Also, communication between the dif-ferent members of the team may be hindered due to a lack of common understanding of concepts. This is often the case when people have no history of interaction and results in a situation where they find it hard to understand exactly what the other is saying, which can lead to frustration and harmful misunderstandings. In the case where common un-derstanding pre-exists, the odds are better that the communication will run smoothly.

623

An Analysis of the Socio-Technical Gap in Social Networking Sites

THE COMPONENTS OF SOCIAL CAPITAL

Before starting the discussion of the social needs which derive from the social-capital related purposes discussed above, we must briefly introduce the components of social capital. What are the elements that are bundled under the label social capital and allow people to accomplish the purposes described in the previous section?

Nahapiet & Goshal (1998) discern three differ-ent components: relational, cognitive and structural social capital.

Relational Social Capital

The relational component of social capital covers parameters influencing relationships, like trust, norm and values, obligations, expectation and identity. These elements influence what will flow over social relationships. People will for example only be willing to share certain knowledge with people they trust.

Cognitive Social Capital

Cognitive social capital refers to the development of cognitive elements that allow communication to occur between actors. This includes shared mean-ing, representations and interpretations. Routing information and performing a concerted action, two of the advantages of social capital described above, can be facilitated if people are able to explicate their own cognitive perspectives and interpret the cognitive perspectives of others (Boland & Tenkasi 1995). This is also the case for situations where there is a pre-established division of cognitive labor that allows people to specialize in certain domains (Wegner 1986), as we will explain in more detail later in this paper.

Structural Social Capital

The structural component of social capital addresses the network structure of people’s interactions. It

covers the creation and dissolution of social rela-tionships and the overall structure of the networks that are formed by these relationships. All the social relationships taken together produce a social network that spans our planet by interconnecting people.

A person’s social network can be thought of as communication paths, over which information is acquired from different parts of the social realm. Structural social capital is a general category un-der which different social network theories can be classified, like the strength of weak ties (Granovet-ter 1973), structural holes (Burt 1992) or network closure (Coleman 1990).

SOCIAL NEEDS IN SOCIAL NETWORKING SITES

In this section, we describe a number of needs of users on social networking sites. These needs have been identified through literature study and our own insight resulting from designing and using social networking sites. Categorization of the needs is done based on the type of social capital they represent.

Social Needs Related to Relational Social Capital

Generalized Reciprocity

Norms describe the accepted behavior within a group of people. The following quote is revealing as it describes how norms play a role in the evolution of loose social relationships into more community-based interactions.

When people are thrown together, and before com-mon norms or goals or role expectations have crystal-lized among them, the advantages to be gained from entering into exchange relations furnish incentives for social interaction, and the exchange processes serve as mechanisms for regulating social interac-tion, thus fostering the development of a network of social relations and a rudimentary group structure. Eventually, group norms to regulate and limit the

624

An Analysis of the Socio-Technical Gap in Social Networking Sites

exchange transactions emerge, including the fun-damental and ubiquitous norm of reciprocity, which makes failure to discharge obligations subject to group sanctions. (Blau 1964, p 90)

Without norms, it can be hard to know how to behave and what to expect from others. A norm that is particularly influential to the construction of social capital is the norm of reciprocity, accord-ing to which a person who provides something to a person in the group can expect something back from this particular person (direct reciprocity) or from another, non-particular person in the collec-tive (generalized reciprocity) (Gouldner 1960). Especially the generalized reciprocity norm is powerful in eliciting behavior which can facilitate information routing and concerted activities in social collectives. To summarize this section, we formulate the following social need:

Social Need 1: Stimulate generalized reciprocity

Trust Building

Trust is an expectation that others will act in a way favorable to one’s interest, even if they have an op-portunity to do otherwise. (Resnick 2001, p9)

Trust is an important component of relational social capital and a prerequisite of many of the interactions in which social networking site users are involved. Trust is built on past interactions and influences future interactions. Still, it can be trans-ferred over social networks. Trusting people who are being trusted by the people you trust yourself is a common way in which initial trust is established. The same is true with distrusting people who are being distrusted by the people you trust. Such initial trust can be an important facilitator to the creation of new social relationships, which alter the structure of one’s social network.

Social need 2: Stimulate the establishment of trust

Social Needs Related to Cognitive Social Capital

Individual and Collective Meaning Negotiation

Constructivist epistemology (Fosnot 1996) teaches us that there is no singular way of perceiving the world. Every person has a different path through life and therefore accumulates different knowledge. This heterogeneity leads to problems in communication, which is essential in allowing social capital to yield its benefits (Boland & Tenkasi 1998, Ackerman 2000). Meaning can be negotiated through com-munication, but not all means of communication are effective ways to negotiate meaning.

Social need 3: Support meaning negotiation

Nuanced Social Activity

Ackerman (2000) remarks that people are very nu-anced in the way they interact with different social partners. The manner in which they interact with one person may not be suitable for interactions with another person. The difference between the two interaction modes can be very small, but very significant. People change the way they interact with each other based on their perception of the people with whom they interact.

Social need 4: Support nuanced social activity

Transactive Memory

People who build social capital by closely working together under prolonged periods of time create an understanding of who holds what knowledge (Wenger 1986). When a certain bit of knowledge is needed, people can engage in a transaction with other people in their social network, to obtain the specific knowledge. In this way, a kind of distributed group memory is created, which people can access by engaging in transactions, hence the name transactive memory. If a transactive memory system is present in the environment in which a person functions, the

625

An Analysis of the Socio-Technical Gap in Social Networking Sites

individual can be freed from accumulating a very broad array of knowledge types and can focus more on specializing in other knowledge types.

Social need 5: Support transactive memory

Awareness

In online environments, people prefer to be aware of who is also present in the virtual space (Acker-man 2000). In this way, they can adapt their social behavior, for example by doing things that attract the attention of certain other people.

Social need 6: support awareness

Social Needs Related to Structural Social Capital

Identity Building

Being able to evaluate another person’s identity is essential if any communication is to ensue. As Simmel (1906, p 441) put it: “That we shall know with whom we have to do, is the first precondition of having anything to do with another.”

Social need 7: support identity building

Creating Social Relationships

Creating new relationships greatly impacts the shape of the social network and therefore the structural social capital of the individual. Initially, hopes where high that social networking sites would be able to expand the social network of its participants. This would hold great promise in a whole number of areas of human activity, ranging from breaking social isolation to the improvement of human creativity.

Recently, however, data collected in social net-working sites has started to suggest that the current generation of social networking sites is not very effective in creating such new relationships. Strong online social relationships seem to reflect relation-ships which have been forged offline (Coenen 2006, Ellison, Steinfield & Lampe 2007).

Social need 8: support the creation of new social relationships

Maintaining Social Relationships

Many social relationships are created as people share a focus, defined as

a social, psychological, legal or physical entity around which joint activities are organized. […] Foci can be many different things, including persons, places, social positions, activities and groups. (Feld 1981, p1016 & 1018)

Indeed, people often build relationships in e.g. a geographic area or around a certain job. As they move away to another area or change jobs, social relationships can become inactive. This atrophy of social network ties is detrimental to the structure of the social network, but keeping up many social relationships can be very costly in terms of time and effort.

Social need 9: maintain social relationships in a time and cost efficient way

TECHNICAL FEATURES IN SOCIAL NETWORKING SITES

The previous section has described some impor-tant social needs, related to the different types of social capital. In this section, we present a model of common technical features in 5 different social networking sites. The sites in our analysis (Face-book, mySpace, Orkut, Xing and linkedIn) where selected on the basis of their popularity at the time of writing.

Method

To identify the socio-technical gap we deduced the needs of the users starting from the assumption that expanding social capital is something people want to do because it is essential to human kind. As much of the insight in social sciences can be seen

626

An Analysis of the Socio-Technical Gap in Social Networking Sites

as a reflection on people trying to manage their social capital, we believe there is some support for this assumption.

Still, it can be argued that this deduction does not completely reflect the needs of the user and that a better way to gather user needs would be to measure them through for example a survey or an analysis of user behavior. However, it is a long standing insight in systems design that users are very often unable to identify their own needs, especially concerning new technological paradigms. For instance, who would have thought ten years ago that people would feel the need to use social networking systems and use them on a massive scale? Therefore, we believe the use of deduction instead of user requirements measurements is a valid way to discuss the socio-technical gap until better ways of predicting user needs have been identified.

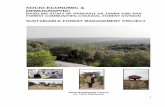

The following method was adopted to analyze the technical components of social networking sites. The technical components where synthesized in a common use case diagram2.

1. Each author created a separate use case dia-gram of 1 or 2 social networking sites. Com-munication on the nature of these use case diagrams was kept minimal, to ensure that each researcher was minimally influenced by the perspectives of the other researchers.

2. The different use case diagrams where dis-cussed by the authors, and it was decided of each use case if it was common to all social networking sites, or specific to just one site.

3. The different use case diagrams where combined into one diagram, representing the features that are common to most social networking sites.

The use cases, represented as ovals in figure 1, are implemented in different ways in the various sites that where analyzed. The numbers in the use cases indicate the number of sites in which a given feature was encountered. Figure 1 shows features which where found in 3 sites or more, in order to support our claim that the presented features are

common in the majority of the analyzed social networking sites.

THE SOCIO-TECHNICAL GAP

In this section, we explain the exact nature of the various use cases in Figure 1 and the social needs which they meet.

Social Need 1: Stimulate Generalized Reciprocity

In order for generalized reciprocity to become wide-spread in the system, a signaling function is neces-sary, telling other people in the system to what degree another user has been carrying out activities to the benefit of third parties. Such a signaling function is particularly useful when obtaining information from others and when carrying out concerted activities. This can be done through a reputation management system (Kollock 1999), in which a feedback signal is coupled to the user’s profile when a certain task is performed for one or more other people. This is a transaction-based way of building reputation. Points can be attributed automatically, or by the recipient of the service. These systems have the potential of being very productive, but were not a part of major social networking sites at the time of our analysis. One exception is Facebook, for which a number of reputation applications have been written that can be plugged into the platform. Still, very few of these applications feature a transaction-based augmenta-tion or diminishing of reputation. Furthermore, no single reputation mechanism seems to have gained wide-spread acceptance.

Social Need 2: Stimulate the Establishment of Trust

Currently, trust is mainly created offline (Matzat 2005), through repeated interactions. This does not mean that trust cannot be created through online interaction. Instead, it points to the fact that in social networking systems, most social relations have been created offline, during face-to-face encounters.

627

An Analysis of the Socio-Technical Gap in Social Networking Sites

At the time of writing, very few features existed in social networking sites that aim to increase trust. As was explained before, trust can be passed on in a transitive way, by trusting the opinion of people you trust yourself. However, few systems feature ways of expressing trust towards others. This could for example be done by labeling a relationship in the dyadic subsystem with a label indicating that a user trusts another user, which amounts to adding semantics to social relationships.

One feature found in linkedIn, but by no means common to other sites3, is the recommendation feature. With this technical function, it is possible to attest to certain aspects of a person’s character or previous work experience. If a person you trust writes a recommendation to a person you don’t

know well, it is likely that your trust towards the latter will increase.

Another example of a feature that can increase trust was found in Orkut, where users are able to write testimonials about users in their network. These testimonials are displayed on the user’s profile page. The value of testimonials is increased by a rating feature that enables Orkut’s users to evaluate people in their network on a number of values, one of which is ‘trust’. When a person with a high trust score writes a testimonial about someone else, the perceived credibility of the testimonial is increased.

Another technical function which is found in figure 1 is the group management function. Consider an interaction between person 1 and person 2, both members of the same group in which a norm exists and is enforced by the members of the group. The

Figure 1. use case diagram representing the common technical features in the social networking sites Facebook, mySpace, Orkut, Xing and linkedIn. (I = individual subsystem, D = dyadic subsystem, G=group subsystem). Numbers in round braces refer to the number of sites in which the technical feature was encountered.

628

An Analysis of the Socio-Technical Gap in Social Networking Sites

Table 1. the socio-technical gap regarding social capital in social networking sites

Social need Component of social capital

Type of social capital

Subsystem Supported technical feature

Missing technical feature part of so-cio-technical gap

1. Stimulate gener-alized reciprocity

Relational • Concerted action• Information

exchange

• Group • Create group (G1.2)

• Manage group (G1.3)

Transaction-based reputation man-agement

2. Stimulate the establishment of trust

Relational • Concerted action• Information

exchange

• Group• Dyadic

• Create group (G1.2)

• Manage group (G1.4)

Trust increasing features at dyadic and group level

3. Support meaning negotiation

Cognitive • Concerted action• Information

exchange

• Group• Dyadic

• Perform private messaging (D1)

Complex mean-ing negotiation through boundary object creation

4. Support nuanced social activity

Cognitive • Concerted action• Information

exchange• Emotional support

• Dyadic• Individual

• Set profile vis-ibility (I1.2)

5. Support transac-tive memory

Cognitive • Concerted action• Information

exchange

• Individual • Edit profile (I1.1) Dynamic, bottom up ways of represent-ing user expertise

6. Support aware-ness

Cognitive • Information exchange

• Emotional support

• Group• Dyadic

• Get updates on contacts activities (D2)

7. Support identity building

Structural • Information exchange

• Emotional support

• Identity • Edit profile (I1.1)

8. Support the creation of new relationships

Structural • Concerted action• Information

exchange• Emotional support

• Dyadic • Perform social network functions (D1)

Integrate collabora-tive technologies in order to support collective action

9. Maintain social relationships in a cheap way

Structural • Concerted action• Information

exchange• Emotional support

• Dyadic • Perform private messaging (D3)

• Get updates on contact’s activities (D2)

norm is very broad and states that group members should always act in each other’s interest. An interac-tion between person 1 and person 2 can be facilitated by this norm, as person 1 will be more disposed to believe that person 2 will act in his interest, thereby increasing trust (cf. the above definition of trust). Thus, group norms can foster trust and features which support norm building can therefore also support the creation of trust.

Still, the number of social network site features which increase trust is limited. As trust is crucial to the creation of social capital, we find this to be an important area of future improvement. This can

be done both at the dyadic and group level. Trust-related features hold most promise for improving the information access and concerted action benefits of social capital.

Social Need 3: Support Meaning Negotiation

Meaning negotiation can occur through commu-nication. Therefore, the communication features that exist in the different social networking sites contribute to the meaning negotiation process. But if

629

An Analysis of the Socio-Technical Gap in Social Networking Sites

the topics around which meaning negotiation should take place are complex, email-like or forum-like functionalities are inefficient.

In such cases, meaning negotiation can take place by explicating and re-combining the perspectives of a number of people. This can be done through called boundary objects, which exist on the boundaries of different cognitive perspectives. Boundary objects represent the concepts in one’s perspective and the relations that exist between these concepts (Boland & Tenkasi 1998).

We have found no support in current social networking sites for complex meaning negotiation through boundary object creation and therefore commit it to the socio-technical gap. If such features where to be included in social networking sites, they would most benefit the information access and concerted action benefits of social capital.

Social Need 4: Support Nuanced Social Activity

The way one interacts varies greatly according to the interaction partner(s), which is currently supported in social networking sites by means of mechanisms for the setting of profile visibility options (use case I1.2 in figure 1). This use case represents the ability of the user to define which parts of one’s profile are accessible to whom. In this way, the different parts of a user’s profile can be made visible to different audiences. The specific implementation varies a lot between sites, ranging from a binary mode where either everything is accessible to anyone or to no one (linkedIn), to a very fine grained mode where the visibility of different profile fields can be made accessible to specific contacts (Xing). Such features are common to the way people communicate their identity, which contributes to all the purposes of social capital, discussed above.

A relevant feature we found in Facebook permits a high degree of control of which people in one’s network are provided with awareness of one’s activi-ties on the site. Activities that can be reported are e.g. which people are added to their network, which messages they have posted and which scores they

have received on a variety of third-party applica-tions. The user is able to define which people in the user’s network are kept up to date of what sorts of actions. This is related to the support of awareness, as described later.

Social Need 5: Support Transactive Memory

The profiles in social networking sites provide a certain amount of information on expertise. In ad-dition, many sites provide full text search options for the content on the site. Both the search option and the profile information can be used to determine who to approach with a certain question. Still, the transaction, necessary to have the person who owns a certain bit of knowledge contribute the knowledge to the person who is looking for it, requires trust and a history of interaction. This type of trust is related to the reciprocation norm discussed before. Therefore, the functioning of a transactive memory system in a social networking site will depend on social needs 1 and 2 concerning reciprocity and trust. Features belonging to this category have the potential of impacting information access and concerted actions.

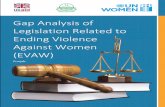

The creation of expertise indexes could be automated by e.g. the collection of web-based folksonomy4 information. Both “tag clouds”, which are relatively unstructured, and more structured network visualizations, can provide interesting clues regarding the expertise and perspective of social networking site users. Examples, developed for our own social networking site prototype called Knosos5 are shown in figure 2. These examples illustrate a bottom-up and dynamic way of creating expertise overviews which can represent expertise for users of social networking sites6.

Social Need 6: Support Awareness

MySpace and Facebook are examples of sites where it is indicated which of a person’s contacts are cur-rently logged in on the site. However, in general, support of awareness in social networking sites is

630

An Analysis of the Socio-Technical Gap in Social Networking Sites

currently poor. This could be due to the fact that they constitute environments in which communication is mainly asynchronous, making it is less important to know who is also using a certain part of the system at the same time.

The situation is somewhat different for periph-eral awareness. Many social networking sites are already featuring elements allowing users to get a peripheral view of the activities undertaken by their contacts in the system. This is important to social capital, as it presents a low cost way of staying in touch with the lives of your contacts. Examples of activities reported in this way in Facebook include the posting of photos, adding new people as contacts or changing profile information. Another feature found in Facebook is the publication of one’s status, allowing other’s to see what a particular person is currently doing.

Awareness-related features are most likely to benefit the information exchange and emotional support dimensions of social capital.

Social Need 7: Support Identity Building

Profiles in social networking sites provide a basic but essential way of getting to know others. This facilitates communication in general and therefore impacts all benefits of social capital, as they all rely on communication. For years, people have gone by without a profile on the web. Either they did not have a place to host their profile or content or they lacked the skill to create web-pages. Social net-working sites have changed this by providing both a hosting solution and a way to create web-pages without needing to learn languages like html. These

Figure 2. Unstructured tagclouds (left) and a more structured tag visualization (right)

631

An Analysis of the Socio-Technical Gap in Social Networking Sites

profiles can be very complex, containing different types of information, like professional information, educational background, but also tastes in books, music, movies, etc.

Profile information can be provided either explicitly or implicitly. Explicit methods allow the user to manually provide information by filling out a form with a number of text fields. Implicit methods gather information automatically from a variety of sources. This can for example be done through a collection of tags on del.icio.us7, which might give an indication of a person’s interests. Another example is the representation of musical tastes through tools like audioscrobbler8, which gather statistics on the music one listens to and al-lows its users to publish this information on other platforms. Implicit methods hold much promise, as they do not require continuous attention from the user in order to stay up-to-date.

Whereas one could think that tastes in types of entertainment would not have its place in more professionally oriented sites like linkedIn or Xing, we would argue that this type of identity building can be instrumental in creating new relationships. Indeed, the more informal aspects of identity are important to the creation of structural social capital, both online and offline.

Social Need 8: Support the Creation of New Relationships

All functions under use case D1 “perform social network functions” in figure 1 are aimed at browsing social networks and adding new contacts to one’s own network. Still, social networking sites are quite bad at creating strong ties (Coenen 2006), character-ized by frequent communication, emotional contacts and a history of reciprocal services

People do create new relationships on social networking sites, but these remain weak. A small number of users are very prolific at extending their social networks, but do this as a kind of contact collectors, aiming for relationship quantity instead of quality.

Another possible reason why few strong ties are forged on social networking sites is the fact that these sites do not foster much repeated collective action. Repeated collective action, like working on a common project, is the type of focus (Feld 1981) around which strong ties can take form.

Many tools are now present on the internet to enable collective activities to be undertaken in a distributed and synchronous or asynchronous way (e.g. synchronous collaborative document writing, voip, group polling for meeting schedules). These tools could be integrated into social networking sites in order to support collective action.

In creating new relationships, social networking sites could support all purposes related to social capital.

Social Need 9: Maintain Social Relationships in a Cheap Way

What is probably the greatest success of social networking sites as they existed at the time of writ-ing is their ability to keep in touch in a relatively cheap way, which also impacts all purposes of social capital. Technical features like the ones support-ing peripheral awareness, and identity building, discussed in an earlier section, are instrumental in allowing users to react to events in other people’s lives. In addition, the communication features provided in social networking sites are a good way of maintaining social relationships. These internal communication channels are increasingly being used by youth, partially replacing email.

LIMITATIONS

The current nature of the internet is such that complete systems or new system functionalities are constantly being added to the collection of available internet-based tools. This is especially true in the light of the recent emergence of social networking system applications developed by users, as is the case on Facebook. This constant emergence re-quires a methodology that is able to track changes

632

An Analysis of the Socio-Technical Gap in Social Networking Sites

on the emergent social web. The method that was used in this paper represents a first attempt to cre-ate a research design capable of dealing with the increased functionality dynamism. Still, the adopted method has as a fundamental limitation that it does not produce statistics indicating the validity of the produced results. In addition, it does not formalize interpersonal subjectivity. The methodology could benefit by accounting for meaning negotiation processes and by producing statistics on intercoder agreement.

To tackle these concerns, we propose to further elaborate the approach used in this paper by using techniques from ontology design. This field has developed a number of methods that allow the de-velopment of ontological artifacts representing com-monly agreed-upon meaning (e.g. MESS (de Moor et al 2006)). Combining these methods with statistics indicating validity, the evolution of the concepts in the ontology and the intercoder agreement would allow a more rigorous approach to the analysis of emergent functionality on the social web.

FUTURE RESEARCH

We see a number of challenges in the future of social networking sites. The first one is to meet the social needs that have been identified as being part of the socio-technical gap with regards to the support of social capital. Still, the way in which these needs can best be met is not necessarily by following the same development tradition as was done in the last 10 years in the social networking site business. New ways of developing applications have begun to emerge, using a plugin approach on an open API9.

In 2007, Facebook was the first site to propose this way of extending its features and it is very prob-able that this approach has greatly contributed to the success of this site. The number of contributed applications that is currently available is large, meeting user needs which the Facebook developers could never have envisaged themselves. Open social, the Google-led initiative to standardize the API’s of

many different social networking sites, holds even greater promise. Indeed, it should allow applications, developed for the Open social API, to be useable on all social networking sites that conform to the API. This will warrant the investments required to develop more social networking site applications, which will consequently be deployable on different systems, thereby possibly spawning a whole new commercial sector.

Such a decentralized plugin architecture will allow new possibilities, like the assembly of a set of applications to meet the needs of a group with a certain objective. In addition, we expect social networking sites to become popular in organizations, e.g. to support knowledge management processes. It will then be relevant to be able to assemble a social networking site configuration which can quickly and cheaply be deployed in the organization, while making use of a social networking platform that is already popular among the employees of the organisation.

In such a constellation, an interesting role would be reserved for open source social network contain-ers. These are information systems offering the basic social networking site features and data storage facilities. Especially the latter could be important to social networking sites in large organizations or organizational clusters, as these entities typically want their data to be protected from prying eyes and stored safely.

In the last 2 years, we have been involved in the development and deployment of such an open source social networking container, Knosos, based on the Drupal content management system. Such open-source content management systems are interesting vehicles on which to develop custom-made social networking systems that leverage open-social like applications.

CONCLUSION

In this chapter we analyzed social networking sites from a social capital perspective. Social needs were discussed and we have indicated which needs are

633

An Analysis of the Socio-Technical Gap in Social Networking Sites

met through which technical features. The features in the socio-technical gap which were identified, are related to the stimulation of generalized reciprocity, the support of meaning negotiation, the support of transactive memory systems, and the creation of new social relationships. We suggest that these are promising areas in which to conduct research and for which to develop new technical features.

REFERENCES

Ackerman, M. S. (2000). The intellectual challenge of CSCW : The gap between social requirements and technical feasibility. Human-Computer Interaction, 15(2), 179-203.

Blau, P. (1964). Exchange and Power in Social Life. New York: Wiley

Bourdieu, P., & Wacquant, L. J. D. (1992). An in-vitation to reflexive sociology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Boyd, D. M., & Ellison, N. B. (2007). Social Network Sites: Definition, History, and Scholarship. Journal of Computer mediated Communication, 13(1).

Burt, R. S. (1992). Structural holes: The social structure of competition. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Burt, R. S. (2000). The Network structure of social capital. Research in Organisational Behaviour, 22, 345-423.

Coenen, T. (2006). Knowledge sharing over social networking systems. PhD thesis, Vrije Universiteit Brussel

Coenen, T., Kenis, D., Van Damme, C., & Mat-thys, E. (2006). Knowledge Sharing over Social Networking Systems: Architecture, Usage Patterns and Their Application. In R. Meersman, Z. Tari, P. Herrero, et al. (Eds.), OTM Workshops 2006, LNCS 4277, 189-198. Springer-Verlag

Coleman, J. S. (1990). Foundations of social theory. Cambridge MA: The Belknap Press.

Ellison, N. B., Steinfield, C., & Lampe, C. (2007). The Benefits of Facebook “Friends:” Social Capital and College Students’ Use of Online Social Network Sites. Journal of Computer mediated Communica-tion, 12(4)

Feld, S. L. (1981). The focused organisation of social ties. American journal of sociology, 86(5), 1015-1035

Fosnot, C. T. (1996). Constructivism: A psycho-logical theory of learning. In C.T. Fosnot (Ed.), Constructivism – Theory, perspectives and practice. New York: Teachers Press College

Granovetter, M. (1973). The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78, 1368- 1380.

Gouldner, A. W. (1960). The Norm of Reciprocity: A Preliminary Statement. American Sociological Review, 25, 161-178.

Hansen, M T. (1999). The search-transfer problem: The role of weak ties in sharing knowledge across organization subunits. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(1).

Kollock, P. (1999). The economies of online co-operation. In M. A. Smith & P. Kollock (Eds.), Communities in cyberspace. London: Routledge, (pp. 220-239).

Matzat, U. (2005). Kennisdeling in online groepen: De sociale inbedding van online interactie in offline relaties. In J. De Haan & L. Van der Laan (Eds.), Jaarboek ICT en Samenleving 2005. Kennis in Netwerken. Boom, Amsterdam

Nahapiet, J., & Goshal, S. (1998). Social capital, intellectual capital and the organizational advantage. Academy of Management review, 23, 242-266.

Resnick, P. (2001). Beyond Bowling Together: Socio-Technical Capital. In J. M. Carroll (Ed.), HCI in the new millennium. Addison-Wesley Professional

Scott, J. (2004). Social network analysis: A hand-book. London: Sage

634

An Analysis of the Socio-Technical Gap in Social Networking Sites

Simmel, G. (1906). The Sociology of Secrecy and of Secret Societies. American Journal of Sociology, 11, 441-498.

Wellman, B., Quan-Haase A., & Chen, W. (2003). The Social Affordances of the Internet for Net-worked Individualism. Journal of computer medi-ated communication, 8(3).

Wegner, D. M. (1986). Transactive memory: A con-temporary analysis of the group mind. In B. Mullen & G. R. Goethals (Eds.), Theories of group behavior (pp. 185-208). New York: Springer-Verlag.

KEY TERMS

Socio-technical gap: “The social-technical gap is the divide between what we know we must sup-port socially and what we can support technically” (Ackerman 2000, p179).

Social networking system: “Social networking systems are web-based systems that aim to create and support specific types of relationships between people.” (Coenen 2006, p 75)

Social capital: “The sum of the resources, actual or virtual, that accrue to an individual or group by virtue of possessing a durable network of more or less institutionalized relationships of mutual acquaintance and relationship.” (Bourdieu & Wacquant 1992, p119)

Relational social capital: The relational compo-nent of social capital covers parameters influencing relationships, like trust, norm and values, obliga-tions, expectation and identity. These elements influence what will flow over social relationships.

Cognitive social capital: Cognitive social capi-tal refers to the development of cognitive elements that allow communication to occur between actors. This includes shared meaning, representations and interpretations.

Structural social capital: The structural component of social capital addresses the network

structure of people’s interactions. It covers the cre-ation and dissolution of social relationships and the overall structure of the networks that are formed by these relationships.

Norm of reciprocity: according to this norm, a person who provides something to a person in the group can expect something back from this par-ticular person (direct reciprocity) or from another, non-particular person in the collective (generalized reciprocity) (Gouldner 1960)

ENDNOTES

1 Note that the meaning of the term “systems” does not only refer to the technical components alone, but includes the people who interact with each other and with the technical com-ponent. This is derived from the way systems are described in systems theory, i.e. as a set of definable components, between which certain relationships exist.

2 Use case diagrams are a part of the UML software modeling language. Each diagram contains actors and the units of interaction which they carry out on the software, repre-sented as use cases.

3 And therefore not listed in figure 14 A web-based folksonomy is a very loose and

bottom-up set of keywords that are attributed to web-based resources

5 The Knosos prototype is accessible at http://www.knosos.be

6 For all their dynamics, the presented examples are less accurate ways of gathering information on people’s expertise than other practices like competence management, which mainly rely on gathering qualitative data.

7 http://del.icio.us8 http://www.audioscrobbler.org9 An API (application programming interface) is

a way for third parties to access the features of a software platform. It allows other programs to work with its functions and variables in a clearly documented way.