Simon Bolivar's Medical Labyrinth: An Infectious Diseases ...

Agrotourism in Crete: lost in a labyrinth. A critical analysis

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of Agrotourism in Crete: lost in a labyrinth. A critical analysis

Agrotourism in Crete: lost in a labyrinth?

Dissertation submitted to the University of Leicester in partial fulfilment of the

Masters in Business Administration

School of Management

Agrotourism in Crete: lost in a labyrinth?

A critical analysis

Stylianos Alexakis

129042043

February 2014

Dissertation submitted to the University of Leicester in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of

Masters in Business Administration

School of Management

Agrotourism in Crete: lost in a labyrinth?

Dissertation submitted to the University of Leicester requirements for the degree of

1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................. 4

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................. 5

CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................... 6

1.1. Statement of the research aims and objectives .......................................... 6

1.2. The Greek island of Crete ........................................................................... 7

1.3. Structure of the dissertation....................................................................... 9

CHAPTER 2. LITERATURE REVIEW AND THEORY .......................................................... 10

2.1. Rural tourism............................................................................................ 10

2.2. Defining agrotourism................................................................................ 11

2.2.1. The definition of agrotourism in the international literature ...... 11

2.2.2. The definition of agrotourism in the Greek literature................. 13

2.3. The product of agrotourism...................................................................... 14

2.4. The benefits of agrotourism ..................................................................... 18

2.5. The profile and expectations of agrotourists............................................. 19

2.6. Examination of agrotourism in various countries ...................................... 20

2.6.1. Agrotourism in England and Wales............................................. 20

2.6.2. Agrotourism in Denmark ............................................................ 21

2.6.3. Spain .......................................................................................... 21

2.6.4. Cyprus........................................................................................ 22

2.7. Agrotourism in Greece.............................................................................. 23

2.7.1. Overview of the agrotourism development in Greece ................ 23

2.7.2. Agrotourism in the Greek island of Lesvos.................................. 26

2.8. Theoretical framework ............................................................................. 28

CHAPTER 3. RESEARCH DATA AND METHODOLOGY.................................................... 30

3.1. Methodology............................................................................................ 30

2

3.2. Data collection.......................................................................................... 32

3.3. Data analysis ............................................................................................ 35

CHAPTER 4. ANALYSIS AND RESULTS........................................................................... 37

4.1. Overview of the agrotourism entrepreneurs ............................................ 37

4.2. The participants’ perception of agrotourism and its key features ............. 37

4.3. The participants’ perception of the benefits of agrotourism ..................... 39

4.4. The profile of agrotourists in Crete ........................................................... 40

4.5. The nature of the agrotourism product offered by local entrepreneurs.... 42

4.6. The participants’ perception of the application of agrotourism in Crete ... 44

4.7. The promotion of agrotourism services .................................................... 45

4.8. The level of synergies among agrotourism entrepreneurs ........................ 47

4.9. Support from public authorities................................................................ 48

4.10. Occupancy and seasonality..................................................................... 50

CHAPTER 5. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS ............................................................. 52

5.1. Summary .................................................................................................. 52

5.2. Theoretical implications............................................................................ 56

5.3. Practical implications................................................................................ 57

5.4. Limitations................................................................................................ 59

5.5. Directions for future research................................................................... 60

5.6. Reflections................................................................................................ 60

5.6.1. Fulfilment of objectives.............................................................. 60

5.6.2. Evaluation of the research process............................................. 61

5.6.3. Self-assessment and personal development gain ....................... 62

REFERENCES ............................................................................................................... 63

APPENDIX A: FRAMEWORK OF INTERVIEW QUESTIONS ............................................. 69

APPENDIX B: DATA ANALYSIS TABLE – PARTICIPANTS A, B, C ...................................... 70

APPENDIX C: DATA ANALYSIS TABLE – PARTICIPANTS D, E, F....................................... 75

3

APPENDIX D: DATA ANALYSIS TABLE – PARTICIPANTS G, H ......................................... 79

APPENDIX E: DATA ANALYSIS TABLE – PARTICIPANTS I, J............................................. 83

APPENDIX F: DATA ANALYSIS TABLE – PARTICIPANTS K, L ........................................... 86

APPENDIX G: SELECTIVE INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPT ....................................................... 89

APPENDIX H: PARTICIPANT INFORMATION SHEET....................................................... 98

APPENDIX I: PARTICIPANT INFORMED CONSENT FORM ............................................ 100

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1: Overview of definitions used in the literature of agrotourism

and related labels ....................................................................................................... 12

Table 2: Agrotourism elements according to Clarke (1996) ......................................... 15

Table 3: Stakeholders of agrotourism industry in Crete............................................... 33

Table 4: Coding of the participants and their profile ................................................... 36

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1: Map of Greece and Crete ............................................................................... 8

Figure 2: Typology of agrotourism............................................................................... 16

Figure 3: Revised typology of agrotourism .................................................................. 17

Figure 4: Map of Greece and Lesvos............................................................................ 27

4

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to take this opportunity to express my deepest gratitude to the following

people:

My supervisor, Dr Olga Suhomlinova, for her valuable assistance and guidance during

the writing of this dissertation.

My personal tutor and MBA Programme Leader, Dr Martin Corbett, for his support and

understanding throughout the MBA course.

The lecturers of the University of Leicester, Dr Andrea Moro and Dr Georgios

Patsiaouras, as well as the doctoral student Ms Yue Fei, for their consultation and

concern.

My friends Kyoko Yumigeta, Sherrill Channer, Pavlos Tatsis, Charilaos Chouliaras and

Marianna Chartzoulaki for their companionship and emotional support.

Brendan Keegan and Aasia Bora for proofreading this paper as well as previous work of

mine.

The staff of the library of the University of Crete, in Rethymno, for their friendly and

encouraging attitude.

All the participants of this study for their valuable contribution to my research.

Last but not least, my parents Nikos and Mary, as well as my brother Alkis, for their

love and constant support.

5

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Agrotourism (also referred to as agritourism, farm-based tourism or farm tourism) has

been greatly promoted in Europe as a sustainable form of rural tourism. In Greece, it

was introduced in the early 1980s, mainly through EU and national subsidies and

gained considerable growth. Yet, results were not as anticipated, and agrotourism

entrepreneurs seem to be lost in a labyrinth of constraints.

This exploratory study examines the case of agrotourism in the Greek island of Crete.

Using face-to-face, semi-structured interviews conducted with a sample of twelve local

agrotourism entrepreneurs, the author attempts to shed light upon the main issues

governing agrotourism in the island, and to reveal the key problems encountered in its

implementation.

Findings reveal that agrotourism in Crete involves mainly the provision of

accommodation, and seldomely the participation in staged farm tasks. Moreover, the

study confirms the importance of agrotourism for the preservation and the promotion

of the traditions and cultural heritage of Crete. Yet, contrary to initial expectations,

there is no evidence that agrotourism contributes to the preservation of the

architectural heritage of Crete. What is more, the study reveals a series of problems

encountered by local agrotourism entrepreneurs, such as the absence of a legislative

framework, limited support from national and public authorities, lack of synergies,

dependency on tour operators and seasonality.

Based on the findings, the author attempts to show the way out of the dead-end by

offering some recommendations. In this context, the paper stresses the need for the

formulation of a legislative framework, the development of a coherent agrotourism

strategy, the backing of agrotourism entrepreneurs, unification of all the

representative bodies, adoption of strict building regulations and the extension of the

tourism period.

6

CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. Statement of the research aims and objectives

Before stating the aims and objectives of this research, it would be useful to offer an

introductory definition of agrotourism:

The concept of agrotourism, as used in Greece, embraces tourism

activities carried out in non-urban regions by individuals mainly

employed in the primary or secondary sector of the economy. Such

activities typically involve small tourism units of family or cooperative

type, which offer accommodations, goods, and/or other services and

provide a supplementary income for rural families and/or an

independent income for women living in rural areas.

(Iakovidou & Turner, 1995: 481)

The aim of this study is to shed light upon the case of agrotourism in the Greek island

of Crete, in a thorough and critical way. In particular, my research will examine

agrotourism in Crete from the supply-side, seeking to identify the main issues

governing its application and to reveal the key problems encountered by local

agrotourism entrepreneurs. Moreover, this paper will attempt to offer some potential

solutions and recommendations, grounded upon the findings of my research.

An in-depth analysis of agrotourism in Crete can be of paramount academic

importance. Admittedly, agrotourism and its applications have been extensively

studied and a plethora of literature is available, examining agrotourism practices in

various countries in Europe and around the globe. In addition, a number of scholars

have investigated agrotourism cases in various Greek regions. Yet no study to date has

examined the case of agrotourism in Crete, despite the popularity of the island as a

holiday destination and its distinct characteristics. In this context, this research comes

to extend the existing body of knowledge and bridge a gap in the literature of

agrotourism as a whole.

7

In addition, this study has great practical implications. An in-depth analysis of the case

of agrotourism in Crete can offer a useful managerial tool, not only in the hands of

agrotourism entrepreneurs but also for national and regional public authorities,

assisting this way in the evaluation of the existing agrotourism policies and facilitate

the development of a more efficient strategy. Such a policy review, I believe, is

essential in order for public authorities to support effectively the application of

agrotourism as a sustainable alternative to mass-tourism. As is well known, the latter

incurs a plethora of negative effects that need to be addressed, such as seasonality,

high dependency on big tour operators, shrinkage of profit margins for local actors,

unbalanced concentration of tourism activities and destruction of the local

environment and natural beauty.

Beyond its academic and managerial significance, the present study has also a

dimension of personal interest. I was born and raised in the island of Crete and I have

strong links with its rural environment. Furthermore, I have considered pursuing, in the

near future, business activities in the agrotourism industry. In this context, the

extensive study of agrotourism in Crete for the needs of this dissertation can also serve

as a vehicle for my professional development.

1.2. The Greek island of Crete

Crete is the largest Greek island and the fifth largest island of the Mediterranean Sea.

With a population exceeding 600,000 inhabitants, Crete is also the most populous

island of Greece and as such, it forms the Region of Crete – one of the 13

administrative regions of Greece. Geographically, the island is located 160 km south of

the Greek mainland (see Figure 1) and comprises a spatial autonomous system beyond

the primary development axes of Greece (Archi-Med, 2001, cited in Andriotis, 2006:

632). Crete is predominately mountainous and has a long coastline of 1300km, with

numerous sandy beaches. Moreover, Crete is renowned for the diversity of its

landscape, its natural beauty and its culture, and for having a plethora of

archaeological sites and historical monuments.

Blessed with all these environmental and cultural resources, the island has inevitably

attracted the attention of tourists. Since the early 1970’s, Cret

tourism development, becoming the most popular holiday destination in Greece. As a

result, tourism has now become the leading economic sector of the island (

2003) and almost 40 percent of the local population is someway engaged in tourism

activities (Andriotis, 2006)

Crete has been problematic, since the island attra

3S’s (i.e. sea, sand, sun). With the advent of mass

of problems such as seasonality, dependence on tour operators, oversupply of

services, concentration of tourist activities on the

degradation, and lack of coordination and strategic planning.

Figure 1: Map of Greece and Crete

Source: (adapted from Wikipedia, 2008)

Seeking to address some of the aforementioned pr

application of tourism, its alternative form of Agrotourism was gradually introduced.

After the 1990’s, a plethora of promotional funds and subsidies by the European Union

and the Greek state was offered to Cretan farmers, in an

to engage into tourism activities. However, despite the successful application of

agrotourism in other European countries, the case of Crete

Greece – has not met expectations, and practice does not seem to m

8

Blessed with all these environmental and cultural resources, the island has inevitably

attracted the attention of tourists. Since the early 1970’s, Crete has experienced rapid

tourism development, becoming the most popular holiday destination in Greece. As a

result, tourism has now become the leading economic sector of the island (

t 40 percent of the local population is someway engaged in tourism

(Andriotis, 2006). Nonetheless, despite its benefits, tourism development in

Crete has been problematic, since the island attracts package tourists seeking for the

3S’s (i.e. sea, sand, sun). With the advent of mass-tourism, the island faced a plethora

of problems such as seasonality, dependence on tour operators, oversupply of

services, concentration of tourist activities on the northern coast, environmental

degradation, and lack of coordination and strategic planning.

Map of Greece and Crete

Wikipedia, 2008)

Seeking to address some of the aforementioned problems caused by the mass

application of tourism, its alternative form of Agrotourism was gradually introduced.

After the 1990’s, a plethora of promotional funds and subsidies by the European Union

and the Greek state was offered to Cretan farmers, in an attempt to encourage them

to engage into tourism activities. However, despite the successful application of

agrotourism in other European countries, the case of Crete – and other regions in

has not met expectations, and practice does not seem to match theory.

Blessed with all these environmental and cultural resources, the island has inevitably

e has experienced rapid

tourism development, becoming the most popular holiday destination in Greece. As a

result, tourism has now become the leading economic sector of the island (Briassoulis,

t 40 percent of the local population is someway engaged in tourism

. Nonetheless, despite its benefits, tourism development in

cts package tourists seeking for the

tourism, the island faced a plethora

of problems such as seasonality, dependence on tour operators, oversupply of

northern coast, environmental

oblems caused by the mass

application of tourism, its alternative form of Agrotourism was gradually introduced.

After the 1990’s, a plethora of promotional funds and subsidies by the European Union

attempt to encourage them

to engage into tourism activities. However, despite the successful application of

and other regions in

atch theory.

9

Contrariwise, Cretan agrotourism entrepreneurs, who have greatly invested in their

business, now seem trapped in a labyrinth of legislative, bureaucratic and managerial

constraints.

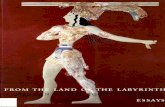

At this point, I should highlight that the metaphoric use of the word “labyrinth” for

agrotourism in Crete and the illustration of its image on the title page, is well-chosen.

According to the Greek mythology, the Labyrinth was an elaborate maze-like

construction in Knosos, under the palace of King Minos of Crete. It was cunningly built

by architect Daedalus to keep confined the Minotaur, a mythical creature with a

human body and a bull's head. The monster was eventually killed by the Athenian hero

Theseus, with the help of Minos' daughter Ariadne, who provided him with a skein of

thread, literally the "clew", so he could retrace his path. Hopefully, this dissertation will

assist Cretan agrotourism entrepreneurs exit the contemporary entrepreneurial

labyrinth.

1.3. Structure of the dissertation

Following the Introduction, Chapter 2 offers a literature review. This begins by

examining the definitions of agrotourism in the international and Greek literature, the

product and the benefits of agrotourism, as well as the profile of agrotourists. To

conclude this chapter, I briefly examine the application of agrotourism in selected

European countries, including Greece and a Greek island in particular. Chapter 3

presents the research methodology, the data collection and data analysis process.

Thus it explains why a qualitative research method, comprising semi-structured

interviews, was chosen, what limitations exists, how the research sample was selected

and how the interviews were conducted. In addition, this chapter offers a description

of the data analysis process. In Chapter 4 my findings are analysed and evaluated in

view of my research questions and the previous studies of agrotourism. This is

followed by Chapter 5, where the key findings are summarised and interpreted,

providing answers to my research questions. The chapter continues on to present the

theoretical and practical implications of my research, its limitations, directions for

future research, as well as a reflective evaluation of the research process.

10

CHAPTER 2. LITERATURE REVIEW AND THEORY

My literature review on agrotourism begins by offering a brief discussion of a broader

concept, namely rural tourism. This is followed by an attempt to define agrotourism

through the plethora of existing definitions both in international and Greek literature.

To gain a better understanding of agrotourism, the paper goes on to examine the

features composing agrotourism as a product, the benefits stemming from its

implementation, as well as the profile and expectations of agrotourists. In what

follows, the paper attempts to offer an insight into the practical issues governing the

application of agrotourism. Hence, an overview of the application of agrotourism in

selected European countries will be presented. This will result in a synoptic

examination of agrotourism developments in Greece and in a selected Greek island. In

conclusion, a theoretical framework is developed, grounded in observations based on

the prior literature. This leads to the narrowing of my research questions and the

identification of the perspectives from which the case of agrotourism in Crete will be

examined.

2.1. Rural tourism

It is worth noting that the concept of agrotourism has been extensively discussed in

the international literature of tourism, and rural tourism in particular. Hence,

agrotourism should be first examined as part of a greater concept, namely of rural

tourism (Gousiou et al., 2001: 7). The latter is generally defined as tourism activities

undertaken in the countryside (Iakovidou, 1997) and encompasses various forms of

tourism such as trekking tourism, ecological, cultural, recreational, culinary, sports and

outdoor activities, agrotourism and the like (Gousiou et al., 2001:7). Because of its

nature, rural tourism is localised in regions that have been left unexploited by the

expansion of mass tourism (Parra and Calero, 2006). Thus, it allows tourists to enjoy

the tranquillity of nature and familiarise themselves with local people and their

customs. Admittedly, the economic benefits of rural tourism, such as revenues and

employment rates, cannot be compared with those deriving from mass tourism (Parra

and Calero, 2006). Yet, rural tourism has contributed to the diversification of rural

11

economies, the provision of an extra sources of income, the creation of new jobs and

the preservation of rural culture and the natural environment (Parra and Calero, 2006).

2.2. Defining agrotourism

2.2.1. The definition of agrotourism in the international literature

As it has been already mentioned, agrotourism is a specific subset of rural tourism

(Nilsson, 2002) and as a term, it also denotes a plurality of other terms which are used

inextricably in literature. Namely, agrotourism is usually also referred to as

agritourism, farm tourism and farm-based tourism or arbitrarily even as rural tourism

(Clarke, 1999; Iakovidou, 1997; Nilsson, 2002; Phillip et al., 2010). Such an application

of diverse definitions and labels often results in a complex, chaotic and problematic

picture, particularly when scholars choose arbitrarily to use one of the

abovementioned terms (Phillip et al., 2010). For the purposes of this paper, the author

will adopt the term agrotourism to signify also the related labels of agritourism, farm

tourism and farm-based tourism. The adoption of the term agrotourism against the

others is deemed necessary, taking into account that agrotourism is the term used

predominately in the existing Greek literature. In addition, it is worth emphasising that

the term “agrotourism” is translated into Greek as “αγροτουρισμός” (pronounced:

agrotourismós) literally meaning, tourism (τουρισμός) in the countryside (αγρός).

Taking into account that despite its constant growth, there is no consensus among the

scholars of what exactly agrotourism is, a plethora of definitions exists in literature.

Looking more broadly at an international dimension, Phillip et al. (2010), examined a

variety of definitions of agrotourism and of the terms labelled as agritourism, farm

tourism and farm-based tourism which have been also used across the literature. As

displayed in Table 1, it is widely perceived by academicians that the notion of

agrotourism – under any label – encompasses terms such as working farm, agricultural

estate, agricultural holding, agrarian stay and the like. Moreover, it appears that

scholars perceive the practitioners of agrotourism as agricultural entrepreneurs,

farmers, or professionals employed in the primary or secondary sector. In turn, the

12

question raised is how the practitioners of agrotourism themselves perceive the notion

of agrotourism. This is another issue I will investigate in my research.

Table 1: Overview of definitions used in the literature of agrotourism and related

labels

Term used Definition Reference

Agritourism “any practice developed on a working farmwith the purpose of attracting visitors”

Barbieri & Mshenga (2008: 168)

“a specific type of rural tourism in which the hosting house must be integrated into an agricultural estate, inhabited by the proprietor, allowing visitors to take part in agricultural or complementary activities on the property”

Marques (2006: 151)

“rural enterprises which incorporate both a working farm environment and a commercial tourism component”

McGehee (2007: 111); McGehee et al. (2007: 280)

“tourism products which are directly connected with the agrarian environment, agrarian products or agrarian stays”

Sharpley & Sharpley (1997: 9)

“activities of hospitality performed by agricultural entrepreneurs and their family members that must remain connected and complementary to farming activities”

Sonnino (2004: 286)

Agrotourism “tourism activities which are undertaken in non-urban regions by individuals whose main employment is in the primary or secondary sector of the economy”

Iakovidou (1997: 44)

“tourist activities of small-scale, family or co-operative in origin, being developed in rural areas by people employed in agriculture”

Kizos & Iosifides (2007: 63)

“provision of touristic opportunities on working farms”

Wall (2000: 14)

Farm Tourism

‘”rural tourism conducted on working farmswhere the working environment forms part of the product from the perspective of the consumer”

Clarke (1999: 27)

“tourist activity is closely intertwined with farm activities and often with the viability of the household economy”

Gladstone & Morris (2000: 93)

“to take tourists in and put them up on farms, involving them actively in farming lifeand production activities”

Iakovidou (1997: 44)

13

“commercial tourism enterprises on working farms. This excludes bed and breakfast establishments, nature-based tourism and staged entertainment”

Ollenburg & Buckley (2007: 445)

“activities and services offered to commercial clients in a working farm environment for participation, observation or education”

Ollenburg (2006: 52)

“a part of rural tourism, the location of the accommodation on a part-time or full-time farm being the distinguishing criterion”

Oppermann (1996: 88)

“increasingly used to describe a range of activities.[which] may have little in common with the farm other than the farmer managesthe land on which they take place”

Roberts & Hall (2001: 150)

Farm-basedtourism

“phenomenon of attracting people onto agricultural holdings”

Evans & Ilbery (1989: 257)

“an alternative farm enterprise” Ilbery et al.(1998: 355)

Source: (Phillip et al., 2010: 755)

With regard to the absence of a theoretical framework in the literature of agrotourism,

Oppermann (1995) suggests that it stems from the problematic situation in regard to

its definition. Busby and Rendle (2000), identify various causes for this. Firstly, the

multitude of activities undertaken in agrotourism hampers the adoption of an accurate

descriptive definition (Busby & Rendle, 2000). Secondly, the majority of agrotourism

enterprises are small-sized and often unwilling to take part in official researches or to

share information. Hence, researchers of the concept of agrotourism often face

insufficient data sources, which lack consistency and are not representative of the

whole population (Busby & Rendle, 2000). Thus, as Busby and Rendle (2000) explain,

most attempts to quantify the size of the agrotourism sector and identify its

development are challenging and troublesome.

2.2.2. The definition of agrotourism in the Greek literature

As Flanigan et al. (2014) maintain, despite the popularity of agrotourism as a term, an

ambiguity still remains in regard to its key features and a common definition is far from

being adopted. In tandem with the international literature, no consensus definition of

14

agrotourism has been adopted in the Greek literature. In one of the well-used

definitions of agrotourism by Greek scholars, agrotourism is defined as “tourism

activities undertaken in non-urban regions by individuals whose main employment is in

the primary or secondary sector of the economy” (Iakovidou, 1997: 44). In another

definition provided by Kizos and Iosifides (2007: 63), agrotourism is defined as ‘‘tourist

activities of small-scale, family or co-operative in origin, being developed in rural areas

by people employed in agriculture”. It is worth noting that the Hellenic Organization

for Standardisation (ELOT), despite using the Greek term “αγροτουρισμός”

(pronounced: agrotourismós), translates the term wrongly in English as “rural

tourism”, thus, causing further confusion. However, the Greek Ministry of Rural

Development and Food correctly defines agrotourism as “a special form of rural

tourism encompassing activities related with agricultural production, the cultural

environment of rural areas, farming activities, local products, traditional cuisine and

local gastronomy”(Greek Ministry of Rural Development and Food, 2013).

According to the Greek literature, the activities of agrotourism may include the supply

by the farmers of accommodation to tourists, the running of catering and recreational

activities for their needs, the organisation of cultural events or outdoor activities,

production and sale to tourists of handicrafts or local agricultural products and so forth

(Iakovidou, 1997; Kizos & Iosifides, 2007; Vafiadis, et al., 1992). On closer examination,

all of the aforementioned definitions accentuate that the practitioners of agrotourism

are predominately – but not exclusively – professionals employed in the primary sector

of economy and farmers in particular. Thus, in this regard, the practice of agrotourism

– at least in the Greek literature – is presented as an activity supplementary to the

main agricultural profession, rather than a profession per se.

2.3. The product of agrotourism

According to Shaw and Williams (1994), there are two principal forms of agrotourism

activities undertaken by farmers, namely, accommodation and non-accommodation

activities. Farmers usually offer just one of the two forms and seldom provide both of

them (Shaw & Williams, 1994). In the same vein, Dartington Amenity Research Trust

(1974) and Davies and Gilbert (1992) identify three different forms of agrotourism,

15

comprising accommodation-based, activity-based and day-visitor-based (cited in Busby

& Rendle, 2000). Whereas from another perspective, Ilbery et al. (1998), differentiate

agrotourism enterprises according to whether accommodation or recreation activities

are provided. In a more elaborate way, Clarke (1996) identify a set of agrotourism

elements (see Table 2) and note that some of them are solely utilised for the needs of

tourism activities. Likewise, Parra and Calero (2006) examine the features of

agrotourism and highlight its key characteristics. They note that:

[Agrotourism] includes shared or independent accommodation at the

owner’s home. It involves the whole family whose customs and traditions

are preserved [and] it allows customers to have a peaceful stay, away

from crowds, assisted by friendly people and a direct touch with nature.

(Parra & Calero, 2006: 86)

Table 2: Agrotourism elements according to Clarke (1996)

Source: (adapted from Busby & Rendle, 2000)

Attractions – permanent Attractions – events

Farm visitor centresSelf-guided farm trailsFarm museumsFarm centresConservation areasCountry parks

Farm open daysGuided walksEducational visitsDemonstrations

Access (rural) Activities

Stile/gate maintenanceFootpaths/bridleways/tracks

Horse-riding/trekkingFishingShooting/clayBoating

Accommodation Amenities

Bed and breakfastSelf-cateringCamping and caravanningBunkhouse barns

RestaurantsCafes/cream teasFarm shops/roadside stallsPick your ownPicnic sites

16

In a similar vein, Phillip et al. (2010) examine agrotourism by considering its products

and activities according to three discriminative features of various types of

agrotourism products. Namely:

The existence or not of a working farm,

The type of tourists’ contact with agricultural activity (passive, indirect or

direct)

The authenticity of agricultural activity which tourist experience (staged or

authentic)

Based on their findings, they offer a typology which categorises agrotourism into five

different types (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Typology of agrotourism

Source: (Phillip et al., 2010)

At this point, it is important to note that the same authors (Flanigan – nee Philip, et al.

2014) have recently offered a revised and modified typology of agrotourism types

Is the tourist activity based on a working

farm?

What is the nature of tourists contact with agricultural activity?

Does the tourist experience authentic agricultural activity?

1) Non-working farm agrotourism – e.g. accommodation in ex-farmhouse property

2) Working farm, passive contact agrotourism – e.g. accommodation in farmhouse

3) Working farm, indirect contact agrotourism – e.g. farm produce served in tourist meals

4) Working farm, direct contact, staged agrotourism – e.g. farming demonstrations

5) Working farm, direct contact, authentic agrotourism – e.g.participation in farm tasks

YES

YES

NO

NO

DIRECT

PASSIVE

INDIRECT

17

which integrates the perspectives of all the stakeholders of the agrotourism industry.

Importantly, this considers both the viewpoints of providers and visitors (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Revised typology of agrotourism

Source: (Flanigan – nee Philip, et al. 2014)

From my point of view, the contribution of Flanigan et al. (2014) to the identification

and classification of agrotourism products is of paramount importance for a number of

reasons. Firstly, because of the nature of their research which is the only study so far

that takes into consideration both aspects of the supply and demand-side. Thus, it

addresses a gap in the existing literature which focuses predominantly on the supply-

side of agrotourism. Secondly, because as a number of scholars highlight (Cooper &

Hall, 2008; Smith, 1994; Swarbrooke, 2002) in the tourism industry, production is

inextricably linked with consumption “which means visitors co-produce tourism

products at the time of consumption” (Flanigan et al., 2014: 395). Finally, and most

strikingly, their study encompasses the notion of tourism products which are not

What is the nature of interaction between visitors and agriculture?

Non-working farm, indirect interaction agrotourism –e.g. accommodation in ex-farmhouse

Non-working farm, direct interaction agrotourism – e.g. agricultural shows, farming museums

Does the visitor experience authentic working agriculture?

Working farm, indirect interaction agrotourism – e.g. farmhouse accommodation

Working farm, direct staged interaction agrotourism – e.g. model farms, farm tours

Working farm, direct authentic interaction agrotourism – e.g. participation in farm tasks

Is the product based on a working farm?

NO YES

NONO YES YES

INDIRECT DIRECT

18

physically based on working farms, as long as they have “some degree of interaction

with agriculture or agricultural heritage (e.g. historical associations, educational

opportunities)” (Flanigan et al., 2014: 398).

This off-farm interaction can be either indirect, aiming at attracting visitors and

promoting traditional lifestyle (e.g. local farms’ produce sold in the farmers’ market or

farm shops/restaurants); or direct (e.g. sheep shearing shows, farming

demonstrations, model farms visits, farm museums). Frequently, non-working farm

indirect-interaction activities are not undertaken by farmers, thus, they can be

considered as other forms of rural tourism and not agrotourism per se. Although their

inclusion to the notion of agrotourism may be controversial and questioned by some

scholars, researches reveal “that a working farm is not required from the visitors’

perspective” (Flanigan et al., 2014; Fleischer & Tchetchik, 2005). Hence, my standpoint

is in tandem with the reasoning of Flanigan et al. (2005), which is the only approach in

the body of literature that takes into consideration both providers’ and visitors’ points

of view of what agrotourism comprises.

2.4. The benefits of agrotourism

The product of agrotourism does not solely signify the provision of services in rural

areas; therefore, it is not just one type of tourist product per se (Busby & Randle,

2000). According to the Commission of the European Communities (CEC, 1999), the

targets of agrotourism are manifold: namely, agrotourism aims at “maintaining

farming activities, promoting diversification of economic practices in the countryside

and rural entrepreneurship, assisting in the preservation of cultural landscapes and

contributing to the new European model of farming” (cited in Kizos & Iosifides, 2007:

71). Consequently, agrotourism is widely associated with the encouragement of

activities of local character, which include the provision of quality goods and services

by farmers and the preservation of rural culture and environment (Gousiou et al.,

2001). In this respect, apart from economic benefits, agrotourism implies social

benefits as well.

19

Seen from another perspective, agrotourism can also be considered as a form of social

tourism since it also puts emphasis on:

… the host/guest relation, the interaction between the host’s private life

and the guest’s experiences. Such interaction is the basic concept of

social tourism, which became popular during the 20s and 30s [and] was

launched as the “true” and non-commercial form of tourism… and aims

to make people feel friendship with each other.

(Nilsson, 2002: 10)

Hence, the notion of agrotourism is also closely interrelated with the notion of the

“contact hypothesis” offered by Reisinger (1994) which suggests “that contact

between different cultures will pave the way for understanding and thereby diminish

the risk of prejudices, conflicts, and tensions” (Nilsson, 2002: 10).

2.5. The profile and expectations of agrotourists

There is a general consensus that agrotourists differ greatly in their attitude from

customers of mass-tourism. They demonstrate a different approach towards travelling

in other worlds, towards local people, their culture and the environment (Parra &

Calero, 2006: 86). Agrotourist are usually educated, travel with their families, and

mainly come from urban areas (Hall & Jenkins, 1998). They prepare their travel by

collecting information in advance about the place they plan to visit, its history, its

culture and the environment (Parra and Calero, 2006: 86). Seeking to experience

authenticity, agrotourists attempt to build relationships with locals, discover their

culture, and participate in local activities and sports (Marsden et al., 2001;

Papakonstandinidis, 1993; Parra & Calero, 2006). Clearly, agrotourists have higher

environment awareness than mass-tourists. Thus, they desire to maximise contact

with nature, by experiencing natural local products and healthy food (Parra & Calero,

2006: 86). In addition, agrotourists tend to avoid the presence of mass-tourists (Parra

& Calero, 2006: 86). Rather, they prefer quality accommodation in peaceful and

tranquil places (Halfacree, 1993).

20

2.6. Examination of agrotourism in various countries

In order to gain a better understanding of agrotourism it is essential to examine its

application in different countries (Nilsson, 2002: 13). Taking into consideration that

Greece in general, and the island of Crete in particular, are located in the

Mediterranean basin, it is also deemed necessary to make selective reference to the

case of agrotourism in other Mediterranean countries. Significantly, contrary to

Northern Europe, agrotourism in European Mediterranean countries is a more recent

phenomenon which evolved after the 1950s and rather than being associated with

agriculture or rural tourism, it is mostly associated with conventional and mass tourism

(Kizos & Iosifides, 2007: 71). Because of its recent emergence, the literature of

agrotourism in European Mediterranean countries is poor and inadequate. A special

case is agrotourism in Tuscany (Italy) which is massively developed and well-studied;

thus, a rich relevant literature exists (Kizos and Iosifidis, 2007: 74).

2.6.1. Agrotourism in England and Wales

As Talbot (2013) points outs, the majority of Welsh farms are small-sized, family-

owned and located in Less Favoured Areas (LFA). As a result, their yields are usually

small and their dependency on subsidies is high (Talbot, 2013). In an attempt to

address the difficulties faced by local farmers and diversify their income, the UK

government adopted the farm diversification policy in the late 1980s (Talbot, 2013).

Subsequent schemes were also introduced, providing both guidance and financial help

in order to diversify and tackle the decline of the rural economy (Walford, 2001).

Within this context of multiple income strategies, agrotourism activities were also

undertaken by Welsh farmers and experienced a steady growth, despite some

occasional trends of stagnation (Nilsson, 2002). Its growth is also attributed to the

contribution of the Wales Tourist Board (WTB) – now named as Visit Wales – which

actively supports rural tourism and agrotourism in particular (Nilsson, 2002). According

to a survey conducted by the Welsh Rural Observatory (2010), besides farming, 10 per

cent of Welsh farmers offer tourist accommodation, 7 per cent offer horse riding

21

activities, 4 per cent offer other leisure activities (including attractions) and 4 per cent

are engaged in retail (cited in Talbot, 2013). Their agrotourism clients are mostly

British – and English in particular – who visit Wales on leisure daytrips or longer

holidays, in order to experience its high quality natural environment (Talbot, 2013).

Such an opportunity for reconnection with the countryside is greatly appealing, taking

into consideration that industrialisation took place early in the UK and thus almost 80

per cent of the English population is urban (Talbot, 2013). Yet, despite its growth, the

sector of agrotourism in Wales and rural tourism in general, is characterised by

fragmentation, limited synergy and the absence of a unifying strategy (Talbot, 2013).

2.6.2. Agrotourism in Denmark

Evidences from Denmark show that approximately 10 per cent of Danish farms have

also engaged in some form of agrotourism activities, after receiving both national and

EU subsidies. The farmers’ contribution to the projects was around 56 percent, with

funds invested in establishing or renovating accommodation facilities. Hjalager (1996)

evaluated the outcome of the projects and examined their economic implications.

Interestingly, his findings indicated that the financial returns were insignificant and

much lower than the initial expectations of the politicians or the farmers themselves

(Hjalager, 1996). Another point worth mentioning is that farmers found it difficult to

combine industrialised agriculture production with agrotourism. They realised that

modern farming activities were completely incompatible with the “hands-on”

experiences demanded by tourists and they often had to be commodified in order to

be offered to tourists as an experiential product (Hjalager, 1996). Notably, the financial

returns of agrotourism were greater in areas where intermediates or consultants were

used (Hjalager, 1996).

2.6.3. Spain

Starting from the mid-1960s and until the 1980s, Spain experienced a period of

depopulation of rural areas and mass migration to urban areas, especially to Madrid

and Barcelona. Seeking to address the ramifications of rural depopulation and the

adverse implications of mass tourism, rural tourism was introduced in Spain after the

22

1980s – much later than the other parts of Europe – and gained rapid growth

(Cánoves, 2004: 760). Its implementation was successful from the very beginning and a

significant contribution to the diversification of the rural economy, the regeneration of

rural life and the maintenance of the levels of rural population (Paniagua, 2002; Yagüe

Perales, 2002). As Cánoves (2004: 762) maintains, agrotourism in Spain evolved in two

stages. During the first stage, in the early 1980s, small family farms seeking to survive

and diversify their activities began offering accommodation to tourists. Interestingly,

during this early phase of agrotourism activities farm women contributed massively by

running the holdings and promoting the local values and hospitality (Cánoves, 2004:

762). A decade later, agrotourism entered into a second stage and a variety of

activities was offered to agrotourists, including visits to places of architectural interest,

sightseeing, visits to vineyards and wine cellars, purchasing of local products and the

like (Cánoves, 2004: 762).

Examining closer the implementation of agrotourism in Spain, Cánoves (2004) has

identified several problems and weaknesses stemming from the recent arrival of

agrotourism in the country. Firstly, the agrotourism product offered by farmers is

limited to board and accommodation. That is why – contrary to their British or French

counterparts who have been trained in offering outdoor activities such as hiking,

trekking, horse-riding, mountain-cycling, or cross-country skiing – Spanish farmers lack

relevant training and experience (Cánoves, 2004). As a consequence, the provision of

supplementary activities is still in an embryonic stage and is undertaken by other

professionals and not by farmers themselves. In addition, as Cánoves (2004)

emphasises, the Spanish autonomous governments which are responsible for

agrotourism legislation show no consensus and lack uniformity in their policy. Hence,

striking discrepancies occur in regard to agrotourism legislation, marketing and

taxation.

2.6.4. Cyprus

The promotion of agrotourism in Cyprus began as early as in the mid-1980s, in an

attempt to address some of the problems caused by the rapid growth of mass tourism

in the island and the popularity of Cyprus as a 3S (Sea-Sun-Sand) destination (Sharpley,

23

2002). In this context, the central policies introduced and the marketing strategies

designed, attempted to improve and diversify the existing tourism product of inclusive-

tours (packages). More specifically, the Cypriot Tourism Organization (CTO) expected

that agrotourism as an alternative would reduce the ramifications of seasonality and

the dependency on major tour operators; attract higher-spending tourists; regenerate

the rural area and spread evenly the social-economic benefits of tourism around the

island (Sharpley, 2002). Nonetheless, the practice of agrotourism in Cyprus was

troublesome. In his elaborate research, Sharpley (2002) revealed multiple problems

encountered by the Cypriot agrotourism entrepreneurs, namely:

Lack of support from the national authorities, including insufficient financing

and guidance

Lack of professional training or education offered to entrants to the projects

Lack of attractions in the villages or local facilities where agrotourists can

experience local culture and tradition

Low occupancy levels, resulting from the high prices of agrotourism

accommodation, the market seasonality and the price consciousness of the

majority of agrotourists – British/Germans

Ineffective marketing efforts and poor back-up by CTO

Lack of collective actions, coordination or common spirit on behalf of

agrotourism entrepreneurs

2.7. Agrotourism in Greece

2.7.1. Overview of the agrotourism development in Greece

In tandem with other European Mediterranean countries, agrotourism in Greece has

been recently introduced. It first appeared as a form of rural tourism during the 1960s

and 1970s, when city residents “escaped” to the countryside, at weekends and during

the national or religious holidays. After the 1980s, this form of rural tourism intensified

and was renamed as agrotourism (Kizos & Iosifides, 2007: 71). The primary reason for

such an evolution was the accession of Greece to the European Economic Community

24

in 1981 which brought about a multitude of orchestrated programmes and initiatives

aimed at the development of the local and rural economies (Kizos & Iosifides, 2007:

71). An additional reason for the encouragement of agrotourism in Greece was the

case for mountainous and less favoured areas (LFA) being brought to the forefront,

especially in terms of living standards and issues such as gender equality (Gidarakou,

1999; Tsartas & Thanopoulou, 1994).

As it is generally acknowledged, agrotourism as a concept is closely interwoven with

gender equality. The establishment and running by women of cooperatives in rural

areas, can serve as a paradigm of this interrelation (Anthopoulou, 2000; Kazakopoulos

& Gidarakou, 2002; Kizos & Iosifides, 2007). Those women’s cooperatives, either

provide accommodation in rural areas or produce local products – sweets, pies, pasta,

jams – or local handicrafts (Kazakopoulos & Gidarakou, 2002; Kizos & Iosifides, 2007).

Their development and financing were greatly assisted both by the European Union

(EU) and national programmes, as well as by the Greek Tourism Organisation and other

public and private organizations (Tsartas & Thanopoulou, 1994). At this point, it should

be stressed that notwithstanding the correlation between women cooperatives and

agrotourism, these kinds of entrepreneurial activities are far from the definitional

context of agrotourism. Therefore, a close examination of women cooperatives is

beyond the purpose of this paper.

In the mid-1980s, agrotourism was introduced in Greece as the primary form of

tourism in mountainous and less favoured areas (LFA) through the programme

“Farmers and Agrotourism” (Kizos & Iosifides, 2007). The areas of application were

particularly those peripherally located with no mass-tourism development (Kizos &

Iosifides, 2007) and those threatened by depopulation and economic decline (Gousiou

et al., 2001). Initially, the agrotourism development plan for Greece as a whole was

composed by the Greek Ministry of Agriculture, and the financing was undertaken by

EU through the Regulation No 797/85 – on improving the efficiency of agricultural

structures – and the LEADER initiative (Kizos & Iosifides, 2007). At the following stages

the financing continued under the Regulations No 2328/86, No 2328/91, No 950/97,

and No 1257/99 and the agrotourism programmes were under the umbrella of LEADER

II and LEADER PLUS initiatives (Kizos & Iosifides, 2007).

25

In order to be subsidised, farmers had to meet certain standards (Kizos & Iosifides,

2007). They had to live permanently in rural areas and practise agriculture as their

primary profession, namely earn more than half of their family income from

agriculture (Kizos & Iosifides, 2007). In terms of establishing agrotourism holdings,

those should comprise a maximum of five rooms or ten beds (Kizos & Iosifides, 2007).

Moreover, all participants in the programmes were committed to run their

agrotourism enterprise for a minimum of five years once the project was complete

(Kizos & Iosifides, 2007). That period was extended to ten years for participants in the

Young Farmers scheme of the EU (Kizos & Iosifides, 2007). Young farmers in Less-

Favoured-Areas received a subsidy that covered the total investment cost by 68 per

cent, while others were funded for 40 per cent of the investment.

According to the Greek Ministry of Rural Development and Food, the targets of

agrotourism programmes were multiple, namely:

The improvement and diversification of rural income

The improvement of the living and working conditions of the rural

population

The sustainment of the rural population and the prevention of

depopulation

The improvement and promotion of local agricultural products and

handicrafts

The protection of the rural environment

The preservation, promotion and utilization of the architectural and

cultural heritage

The enhancement of the attractiveness of rural areas

The support of entrepreneurship

(Greek Ministry of Rural Development and Food, 2013)

As Gousiou et al. (2001) emphasise, the Greek authorities failed in integrating

agrotourism policy as part of a greater tourism policy or as a constituent of a national

26

strategy for rural development. The Greek Ministry of Agriculture undertook the initial

agrotourism planning, yet no national or regional authority was established for its

implementation (Anthopoulou, 2000; Gousiou et al., 2001; Iakovidou et al., 2001).

Consequently, all the programmes were realised by private enterprises owned by

farmers or small-size local cooperatives (Anthopoulou, 2000; Gousiou et al., 2001;

Iakovidou et al., 2001). The outcome was that the majority of the projects only

involved the construction of holdings in rural areas, plus the establishment of some

restaurants. It is striking that beyond that, farmers as a rule did not show any interest

in providing any other form of tourism services or activities (Anthopoulou, 2000;

Gousiou et al., 2001; Iakovidou et al., 2001). Additionally, once the investments were

completed, no national or local monitoring body provided any guidance, control,

training or consultation; and any management assistance was merely offered by

private small-size organizations and various development agencies operating at a local-

level (Iakovidou et al., 1999). In the aggregate, no synergies were established between

Greek agrotourism enterprises and no conjoint marketing or promotional activities

were undertaken (Iakovidou et al., 1999).

Seeking to elaborate further upon the implementation of agrotourism in Greece, an

examination of agrotourism cases in a Greek island will follow:

2.7.2. Agrotourism in the Greek island of Lesvos

Lesvos is a forested and mountainous island located in the north-eastern Aegean Sea

(see Figure 4). It is one of the biggest Aegean islands and the third largest island of

Greece behind Crete and Evia. Its economy is mostly based in agriculture, and in

particular the production of olive oil – which is the main source of income – and

cheese. Tourism in Lesvos is a complimentary economic activity which contributes

significantly to the local economy, but its practice is rather undeveloped vis-à-vis other

Greek islands. Most of the island comprises mountain areas where agriculture is the

only form of economic activity; hence, tourism is unevenly expanded and is developed

only in coastal areas, predominately in the West and North part of the island (Gousiou

et al., 2001).

Figure 4: Map of Greece and Lesvos

Source: (adapted from Wikipedia, 2008)

Lesvos is a Less-Favoured

as such, it was one of the first Greek regions where agrotourism programmes were

launched as early as the mid

agrotourism in the island of Lesvos,

and interviewed a representative sample comprising owners of

Their findings were interesting

functional principals of agrotourism:

The investments’ nature, to start with, mainly involved the establishment

of accommodation and restaurants

More than 96 per cent of the investment funds were received by areas

where tourism had been already developed

Investments concerned only the construction of new buildings and

seldom the reconstruction of

Agrotourism operations were signif

the exception of restaurants which operated on

majority of agrotourism holdings operated only during the summer

months and mainly during July and August

27

Map of Greece and Lesvos

Wikipedia, 2008)

Favoured –Area, under the EU definition of Regulation No 75/268) and

as such, it was one of the first Greek regions where agrotourism programmes were

launched as early as the mid-1980s (Gousiou et al., 2001). In an attempt to examine

agrotourism in the island of Lesvos, Gousiou et al. (2001), examined secondary data

and interviewed a representative sample comprising owners of agrotourism holdings.

interesting and insightful and revealed many facts that oppose the

functional principals of agrotourism:

The investments’ nature, to start with, mainly involved the establishment

of accommodation and restaurants

More than 96 per cent of the investment funds were received by areas

where tourism had been already developed

Investments concerned only the construction of new buildings and

seldom the reconstruction of the existing ones

Agrotourism operations were significantly affected by seasonality. With

the exception of restaurants which operated on a yearly basis, the

majority of agrotourism holdings operated only during the summer

months and mainly during July and August

Area, under the EU definition of Regulation No 75/268) and

as such, it was one of the first Greek regions where agrotourism programmes were

). In an attempt to examine

), examined secondary data

agrotourism holdings.

and revealed many facts that oppose the

The investments’ nature, to start with, mainly involved the establishment

More than 96 per cent of the investment funds were received by areas

Investments concerned only the construction of new buildings and

icantly affected by seasonality. With

yearly basis, the

majority of agrotourism holdings operated only during the summer

28

Agrotourism operations did not generate new jobs. Rather, it enhanced

employment of family members and in particular of women who were

primary in charge of managing the agrotourism business

Provision of extra agrotourism activities beyond catering and

accommodation, is rare. Even when additional activities are offered, they

are remarkably limited and irregular and comprise hiking, horse riding

and exhibition of animals’ care

Only 20 per cent of agrotourism entrepreneurs promote their products.

Surprisingly, no public or private agrotourism agencies operate in the

island

Despite the shortcomings, the majority of the owners expressed their

satisfaction with agrotourism activities and stated that agrotourism

improved considerably their household income

(Gousiou et al., 2001)

2.8. Theoretical framework

Taking into account the findings of earlier studies which examine the application of

agrotourism in various countries, it is interesting to note both the existence of some

contradictions as well as the emergence of common patterns. In an attempt to better

formulate the research questions of this study and derive specific predictions, the

aforementioned findings will be scrutinised and will be utilised for the formulation of a

theoretical framework.

With regard to the definition of agrotourism and its key features, observations from

the prior literature indicate that there is a general lack of consensus among the

academics of what exactly agrotourism is. I argue that this “complex and confusing

picture” (Phillip et al., 2010) expands further to the cohorts of the agrotourism

entrepreneurs. Therefore, what I will initially examine is:

Q1: How do agrotourism entrepreneurs perceive the notion of agrotourism and

its key features?

29

Building on earlier studies about the application of agrotourism in the Greek island of

Lesvos, which reveal that the majority of investments concerned only the construction

of new buildings and seldom the reconstruction of existing ones, doubts are raised

about the contribution of agrotourism to the preservation, promotion and utilization

of the architectural and cultural heritage. My concern is further enhanced by my

existing knowledge that due to lack of controls and regulations, farmers in Crete – like

in the rest of the country – perceived agrotourism subsidies as an opportunity to build

new luxurious accommodation at low cost without actually pursuing agrotourism

operations. Therefore, I will elaborate further by examining:

Q2: To what extent did agrotourism contribute to the protection of the

environment, as well as to the preservation and promotion of the architectural

and cultural heritage of Crete?

Q3: What other activities beyond accommodation, do agrotourism

entrepreneurs offer to their clients?

Drawing on both the international and Greek literature of agrotourism, it emerges that

farmers face significant difficulties in promoting their agrotourism operations, in

coordinating their activities and in establishing synergies. Furthermore, they receive

insufficient training, consultation and guidance by local or national authorities. The

latter often fail in providing an integrated and coherent agrotourism policy. Hence, my

last questions are:

Q4: What problems do agrotourism entrepreneurs face in promoting their

business and what is the degree of dependency on tour operators?

Q5: Which is the level of synergies among agrotourism entrepreneurs?

Q6: To what extent do agrotourism entrepreneurs in Crete receive consultation

and guidance from the local or national authorities?

30

CHAPTER 3. RESEARCH DATA AND METHODOLOGY

3.1. Methodology

As I have already mentioned, despite the plurality of studies about the tourism

industry in Crete, no research has examined so far the concept of agrotourism in the

island. In this sense, my study of agrotourism in Crete comes to bridge a gap in the

existing literature of agrotourism in Greece as a whole. Furthermore, contrary to

previous studies which base their findings on a single category of actors, my research

will examine agrotourism by indentifying and considering some of the major

stakeholders involved in its application from the supply side. Namely, my investigation

will examine the perspective of owners of agrotourism holdings, rural tourism and

agrotourism agents, as well as the viewpoint of the agrotourism union of Crete. Since

the main topic of my study has not been already examined by other researchers, my

research is exploratory in nature. Thus, a qualitative research method is considered to

be more appropriate. As it is commonly acknowledged, the elaborate qualitative

research methods allow the researcher to gain an insight into the individual’s

perspective, develop an understanding from multiple perspectives and reach the

deeper truth (Abawi, 2008; Patton, 2002). What is more, qualitative research is more

suitable when the researcher seeks to build a complex and holistic picture of his

subject of study (Abawi, 2008; Patton, 2002). Therefore, it suits the objective of this

research, which seeks to offer an in-depth critical analysis of agrotourism in Crete.

For the purpose of my research, in-depth data were collected by conduction of semi-

structured face-to-face interviews. I have chosen the interview method as the most

proper for my study for a number of reasons. Notably, in-depth interviewing “uses

individuals as the point of departure for the research process, assumes that individuals

have unique and important knowledge about the social world that is ascertainable,

which can be shared through verbal communication” (Hesse-Biber & Leavy, 2011: 94,

cited in McGehee, 2012: 365). Moreover, interviewing is a flexible technique

particularly effective for researchers seeking to capture the informant’s thoughts,

experiences and perceptions in an in-depth and specific way (McGehee, 2012). Thus, it

is a valuable tool for extracting exploratory data. Consequently, interviewing is a

31

qualitative research method that has been widely used in the study of tourism during

the last 30 years (Goodson & Phillimore, 2004). Admittedly, my point of view is in

tandem with McGehee (2012) which highlights that:

On the supply-side, tourism industry stakeholders are often very busy

people, but they also tend to be immersed and involved in their work,

and as such are eager to share their thoughts. From a practical

perspective, the relative youth of the industry, along with a lack of clean,

systematic, quantitative data measuring the tourism industry also

contributes to the usefulness of the interview technique in tourism…

[What is more,] this is an era where researchers are finding average

survey response rates to be plunging (Sheehan, 2001), often due to

survey fatigue. The interview technique may incite a more welcome

response from potential tourism study subjects of all types.

(McGehee, 2012: 366)

Accordingly, numerous researchers have used interview methods in order to examine

the concept of agrotourism from the supply-side. The studies undertaken by Flanigan

et al. (2014), Gousiou et al. (2001), Kizos and Iosifides (2007), Sidali (2009), Sharpley

2002) and Talbot (2013) are just but a few examples.

I have opted for the face-to-face interview technique due to its advantages compared

with other interview methods. As Opdenakker (2006) points out, face-to-face

interviews are characterised by synchronous communication in time and place, and

they can take advantage of social cues – such as voice, intonation, body language – of

the interviewee. Thus, the interviewer may build rapport and extra information can be

added to the verbal answer of a question. This effect is particularly beneficial when the

interviewee is seen as a subject and as an irreplaceable person whose attitude towards

an issue is investigated (Opdenakker, 2006). In addition, face-to-face interviews

provide more spontaneous answers as there is no time delay between question and

answer, allowing the interviewer to concentrate more on the answers given. The

former advantage is particularly useful when structured or semi-structured questions

are posed. Notably, as face-to-face interviews can be tape-recorded, they provide a

32

more accurate report. Since, the nature of my interviews has been semi-structured, I

was provided with more freedom to divert from the prepared question-list when

necessary and bring new ideas during the interview process.

Admittedly, the face-to-face interview technique I have chosen is not without

limitations. The process is time consuming and entails more effort and cost when

travelling is required. Thus, in order to mitigate the effect of the former limitation, I

was bound to limit the number of interviewees to a representative sample of each

group of stakeholders. Besides, because of the nature of the face-to-face interview

technique, there were a number of ethical issues that I had to consider. As Opdenakker

(2006) highlights, the visibility of a face-to-face interview may result in unwanted

effects, when the interviewer consciously or unconsciously gives cues that drive the

interviewee to a specific direction. The risk of bias is also high, both during the

interview process and the data analysis and interpretation (Opdenakker, 2006).

Another ethical consideration, results from the scale of this research. Because of the

small sample of the participants in this study and the personal nature of the

interviews, the findings may be also biased and lack validity or may be difficult to

generalise.

3.2. Data collection

For the needs of my study, a sample comprising 12 actors in the agrotourism industry

in Crete was selected and interviewed. My attempt was to achieve a representative

examination of the key groups of stakeholders involved in the implementation and the

development of agrotourism from the supply side (see Table 3). Due to time, financing

and networking limitations, I was obliged to exclude any kind of public authorities from

my research. Furthermore, I also opted to exclude members of the local communities,

since I judged that – although they have a stake – they scarcely contribute to the

implementation or the development of agrotourism.

33

Table 3: Stakeholders of agrotourism industry in Crete

As a starting point, I interviewed a senior member of the Association of Travel

Agencies of the city of Rethymno, in Crete. This was a pilot interview that helped me

significantly fine-tune the framework of my questions. Strikingly, it also served as a

vehicle for outlining the map of the local agrotourism industry, identify its key

stakeholders and select the first participants of my study. At this point, it should be

noted that participants were recruited by a combination of purposive and snowball

sampling. Due to the relative small size of the agrotourism industry in Crete, people

involved in it are aware of a multiple of other actors. In this way, it gradually became

possible to evaluate the potential contribution of persons suggested to participate in

my research by more than one source and shortlist them effectively. Hence, I

conducted face-to-face interviews with the following participants:

Six (6) owners of agrotourism holdings in the areas of Rethymno and Chania

(Crete) varying in business size and turnover

One (1) operations manager of a agrotourism model farm, part of a hotel chain

One (1) senior member of the Agrotourism Union of Crete – also senior

member of the Federation of Agrotourism Unions of Greece (SEAGE) and

owner of agrotourism holdings

One (1) senior member of the local union of travel agencies

One (1) owner of rural tourism travel agency

Two (2) owners of agrotourism travel agencies

Supply side Demand side

EU authorities Agro-tourists

National authorities

Regional and local authorities

Tour operators

Travel and Agrotourism agencies

Agrotourism holdings ownersAgrotourism unions/associations

Local communities

34

As far as the interview questions are concerned, an interview guide was used (see

Appendix B), comprising questions specially adapted to each participant according to

which group of stakeholders they belonged. Not surprisingly, some of the participants

expressed the desire to be informed in advance of the context of the interview

questions. Since I was bound to do so in order to secure their contribution, I

communicated the interview guide to them. Yet, I did not omit to highlight that

interviews would be semi-structured and that questions would be adjusted to the flow

of the discussion.

Participants were directly contacted either by phone or by a personal visit. I considered

that establishing a preliminary contact in such a direct way, rather than by email, was

the most appropriate way to build rapport, taking into account the local temperament.

Notably, Cretan people – including businessmen – prefer a direct face-to-face

approach and seek social contact. Interviews were conducted either at the office of the

participants or at their place of residence according to what they desired. I believed

that participants would feel more relaxed and at ease in a place of their selection and

thus the development of rapport would be facilitated. In the same context, I

attempted to adjust my dress and attitude, to the social class and role of each

interviewee. To give but one example, I opted for casual dressing when interviewing a

farmer in my father’s village, politely asked for a cup of traditional Greek coffee and

carefully avoided any use of academic jargon during our conversation. It is relevant at

this point to highlight that after conducting a few interviews, I realised that most of the

participants felt rather uncomfortable when hearing the word “interview” which they

possibly associate with the concept of “press and journalists”. Remarkably, their

awkwardness was also enforced by the view of my tape-recorder and the request of

their consent to record the interview. In order to avoid this implication, I simply

replaced the phrase “may I please have your permission to record the interview” with

the phrase “would you mind if I use my mobile to record our discussion” – assuming

that the word “mobile” also sounds more familiar to them. Overall, I carefully sought

to keep eye contact and “hear behind the words” by interpreting the body language of

the participants. In an attempt to “break the ice” and enhance familiarity, a bottle of

local wine produced by my father was offered as a present to every participant, a

35

gesture highly admirable in Crete. Thus, in all but one interview, familiarity was

progressively developed and rapport was built.

Remarkably, all the participants that were contacted agreed immediately to participate

in my research and demonstrated enthusiasm for my study and a solid willingness to

contribute to it. This fact is of great importance, taking into consideration their busy

schedule and that the conduction of the interviews also coincided with the festive

period of Christmas when most Greeks dedicate their free time to their families. It is

my belief that participants were encouraged by the potential contribution of my

research to the local agrotourism industry and their willingness to exhibit solidarity