A Review of Interventions with the Potential to Reduce Hospital Errors: The Culture-Outcomes...

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

3 -

download

0

Transcript of A Review of Interventions with the Potential to Reduce Hospital Errors: The Culture-Outcomes...

PU34CH22-Singer ARI 13 February 2013 23:6

Reducing Hospital Errors:Interventions that Build SafetyCultureSara J. Singer1 and Timothy J. Vogus2

1Department of Health Policy and Management, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston,Massachusetts 02115; email: [email protected] Graduate School of Management, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee37203; email: [email protected]

Annu. Rev. Public Health 2013. 34:373–96

First published online as a Review in Advance onJanuary 16, 2013

The Annual Review of Public Health is online atpublhealth.annualreviews.org

This article’s doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031912-114439

Copyright c© 2013 by Annual Reviews.All rights reserved

Keywords

safety culture, safety climate, medical errors

Abstract

Hospital errors are a seemingly intractable problem and continuingthreat to public health. Errors resist intervention because too often theinterventions deployed fail to address the fundamental source of errors:weak organizational safety culture. This review applies and extends atheoretical model of safety culture that suggests it is a function of inter-related processes of enabling, enacting, and elaborating that can reducehospital errors over time. In this model, enabling activities help shapeperceptions of safety climate, which promotes enactment of safety cul-ture. We then classify a broad array of interventions as enabling, enact-ing, or elaborating a culture of safety. Our analysis, which is intended toguide future attempts to both study and more effectively create and sus-tain a safety culture, emphasizes that isolated interventions are unlikelyto reduce the underlying causes of hospital errors. Instead, reducingerrors requires systemic interventions that address the interrelated pro-cesses of safety culture in a balanced manner.

373

Ann

u. R

ev. P

ublic

. Hea

lth. 2

013.

34:3

73-3

96. D

ownl

oade

d fr

om w

ww

.ann

ualr

evie

ws.

org

by V

ande

rbilt

Uni

vers

ity o

n 03

/21/

13. F

or p

erso

nal u

se o

nly.

PU34CH22-Singer ARI 13 February 2013 23:6

INTRODUCTION

Scholarly and practitioner interest in hospitalerrors—errors that result from poorly designedand managed systems and are attributable tothe actions of multiple organizational partici-pants who deviate from organizationally spec-ified rules and procedures (50)—took holdmore than a decade ago with the Institute ofMedicine’s landmark report, To Err Is Human:Building a Safer Health System (74). However,despite a great deal of academic research andpractitioner experimentation, hospital errorscontinue to present a seemingly intractablepublic health problem (78), the dimensions ofwhich may be greater than initially imagined(18).

A hospital’s inability to reduce these errorsstems from their organizational (123) and sys-temic (134) nature, meaning that they are inte-grated into complex and interrelated structuresand processes to which individuals through-out the hospital contribute. Their causesreside in the organization’s culture—its as-sumptions, values, attitudes, and patterns ofbehavior (130). Errors are intractable when aculture de-emphasizes safety and instead pri-oritizes competing concerns (e.g., cost, effi-ciency) that can produce errors (182). A safetyculture consists of the shared values, attitudes,and patterns of behavior regarding safety (i.e.,concern about errors and patient harm thatmay result from the process of care delivery)(124). Culture may vary within organizationsand among their units and by professional disci-plines. Safety climate, a related construct, refersto shared perceptions of existing safety policies,procedures, and practices (183). In other words,safety climate reflects the extent to which theorganization values and rewards safety relativeto other competing priorities as demonstratedthrough organizational policies and leader be-havior (181). The expression of safety climatein specific and identifiable policies and prac-tices means that it captures “surface features”of a safety culture (36).

The goal of this review is to provide apublic health and management audience with

an understanding of how a broad array ofinterventions may be combined to reducehospital errors. Our review focuses specificallyon hospital errors because this is where thebulk of intervention efforts have been directedand where the measurement of errors is mostdeveloped. To distinguish our review fromother excellent recent reviews of interventionsdesigned to reduce organizational errors in thehealth care context (34, 176), we focus explicitlyon interventions that reduce errors by directlyor indirectly impacting safety culture. Thisallows us to categorize these activities using atheoretical model that shows how interventionsmay work together to shape safety climate andsafety culture in a process that reduces hospitalerrors over time. We focus on culture ratherthan errors themselves in recognition of theimportance of culture as a basic mechanismthrough which patient safety is achieved (21). Adeeper understanding of the cultural underpin-nings of errors provides a more organizationaland systemic foundation for reducing them.

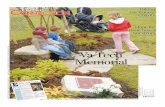

An Enabling, Enacting, andElaborating Model of Safety Culture

We focus on safety culture as the foundationupon which hospitals can reduce errors by pre-venting and learning from them (120). Thatis, a well-developed safety culture seeks to re-solve the underlying causes of errors. To date,however, the ways in which interventions shapesafety culture have been imprecisely specified.Our review employs a recently developed con-ceptual framework (164) to suggest that exist-ing interventions tend to target one of three as-pects of safety culture—enabling, enacting, orelaborating—that when taken together createa process with the potential to reduce hospitalerrors over time. Enabling refers to leader ac-tions that emphasize safety, enacting includesfrontline actions to surface and resolve threatsto safety, and elaborating means systematicallyreflecting on and learning from performance(164). In turn, new enabling interventions maybe selected on the basis of evolving needsand hospital culture. Thus, cycles of enabling,

374 Singer · Vogus

Ann

u. R

ev. P

ublic

. Hea

lth. 2

013.

34:3

73-3

96. D

ownl

oade

d fr

om w

ww

.ann

ualr

evie

ws.

org

by V

ande

rbilt

Uni

vers

ity o

n 03

/21/

13. F

or p

erso

nal u

se o

nly.

PU34CH22-Singer ARI 13 February 2013 23:6

Fewer hospitalerrors

Safety culture

Safety culture

Safety culture

Safety culture

Safety culture

Safety climate External actions:

• Accreditation and advocacy

• Surveys

• Work hours rules

Internal actions: • Leader behaviors and

practices

• HR practices

• Technology (EMR)

Enabling Policies and practices

that motivate thepursuit of safety

EnactingFrontline actions that

improve patient safety

• Interpersonal processes

(e.g., teamwork)

• Reporting and voicing

concerns

• Coordinating at care

transitions (hand overs)

and across interdependent

functions (checklists)

Shared assumptions,values, attitudes, andpatterns of behavior

regarding safetythat become

embedded over time

Frontlineinterpretations of

safety-related leaderactions and

organizational practices

• Learning-oriented

interventions

• Education (simulation)

• Operational improvement

(case-based analysis and

frontline system

improvement)

• System monitoring

(prospective, retrospective,

concurrent)

Elaborating Learning practices thatreinforce safe behaviors

Figure 1A cultural approach to reducing hospital errors. EMR, electronic medical record; HR, human resources. Adapted from Reference 164.

enacting, and elaborating continue iterativelyin an evolutionary process.

In applying this model to a compre-hensive set of interventions, we make twoimportant refinements. First, we find thatenabling occurs not only through hospital lead-ers but also through external actors (e.g., ac-tivists and quasi-regulatory agencies). Second,we posit that these enabling activities shapefrontline workers’ perceptions of safety climateand thereby promote the enactment of safetyculture. Figure 1 depicts our theoretical model,which highlights the interrelationships amonginterventions that enable, enact, and elaborate aculture of safety to reduce hospital errors. Thearrows in this model indicate that climate andculture are dynamic processes.

In this review, we organize disparateresearch on discrete interventions to reducehospital errors and apply and extend an inte-

grative model to highlight distinctions amongthe interventions’ objectives. Our primary con-tribution is the conceptual categorization ofinterventions and the identification of relation-ships among them. This is important becausethe fragmented nature of prior research on hos-pital errors provides an inadequate foundationfor practitioners to pursue more than piece-meal solutions. Our analysis also provides re-searchers with a richer, theoretically groundedframework for understanding how interven-tions combine to reduce hospital errors. Weoffer practitioners a guide to more effectivelycreating and sustaining safety culture. Ourreview suggests that isolated interventions thatenable, enact, or elaborate a culture of safetyare unlikely to reduce the underlying causes ofhospital errors. Instead, hospital errors requireinterventions that simultaneously address allthree aspects of culture rather than only one.

www.annualreviews.org • Reducing Hospital Errors 375

Ann

u. R

ev. P

ublic

. Hea

lth. 2

013.

34:3

73-3

96. D

ownl

oade

d fr

om w

ww

.ann

ualr

evie

ws.

org

by V

ande

rbilt

Uni

vers

ity o

n 03

/21/

13. F

or p

erso

nal u

se o

nly.

PU34CH22-Singer ARI 13 February 2013 23:6

This review represents a broad, albeit notcomprehensive, review of research published inthe management and health services literatureson interventions attempting to reduce hospi-tal errors. More specifically, in ABI/ProQuest,PsycINFO R©, and PubMed, we searched onthe terms “safety” or “error” and “culture”in a set of leading management, psychol-ogy, health services, health care management,and medical journals (see Supplemental Ap-pendix online. Follow the Supplemental Mate-rial link from the Annual Reviews home page athttp://www.annualreviews.org), focusing onarticles published during the most active periodof research on hospital errors (between 2000and early 2012). We identified 593 articles. Byreviewing the abstracts of these articles, we de-rived a list of intervention types. We next as-signed these intervention types to an elementof the conceptual model so that each type of in-tervention was classified primarily as enabling,enacting, or elaborating a safety culture. Wealso looked for interventions that might not fitin the conceptual model. Then, the authors anda research assistant each reviewed a third of thepapers to assign each one to the applicable in-tervention type or types. We conducted a sec-ond review to confirm the assignments. At eachstage, the group discussed interventions or pa-pers that raised questions and jointly resolvedtheir classification. This allowed us to supple-ment and refine our list of intervention typesand the relationships among them. Table 1 be-low summarizes the literature in each category(e.g., enabling) and subdomain (e.g., technol-ogy). We describe the interventions designedto promote each of the elements of the concep-tual framework in turn.

ENABLING

Enabling a safety culture means motivating thegoal of reducing hospital errors, directing at-tention to and prioritizing safety, and creat-ing a context within which frontline caregiverscan enact safer practices. In reviewing these in-terventions, two sets of mechanisms emerged:(a) external motivators, such as regulators and

advocacy organizations, and (b) internal mo-tivators, such as leaders and organizationalpractices.

External Motivators

Researcher and practitioner interest in safetyculture as a key source for reducing hospital er-rors took hold with the Institute of Medicine’sTo Err Is Human (74) and subsequent reports.These early efforts to induce action tried to es-tablish the scope of the problem (e.g., the num-ber of deaths resulting from hospital errors) soas to motivate remedial actions (19, 74). Thesearch for more accurate measures of the scopeof the problem continues (18). Administrativedata such as the Agency for Healthcare Re-search and Quality’s patient safety indicators(91) provide another source of data intended tofuel change; however, some evidence suggeststhat they do not predict individual hospital per-formance (171).

Although only suggestive, there are indica-tions that external actors can influence hospitalerror reduction. For example, The JointCommission on Accreditation of HealthcareOrganizations has influenced hospital-levelpatient safety initiatives (27), as have advocacyorganizations such as the Institute for Health-care Improvement, the National Patient SafetyFoundation, and the Lucian Leape Institute.Collaboratives, such as the Pittsburgh RegionalHealth Initiative, also spur hospital-level effortsto reduce hospital errors (143). The Institutefor Healthcare Improvement’s national andinternational initiatives, such as the 100,000Lives Campaign, establish goals and provide amodel for spreading improvement practices toreduce hospital errors (90).

Other research suggests external forces, e.g.,tort reform, may induce hospitals to focus onreducing errors (4); however, the evidence oftheir efficacy is mixed (24). Legislatures andother policy-setting bodies are external forcesthat affect health care delivery through rules re-garding practices shown to compromise safety,e.g., extended-duration work shifts (greaterthan 12.5 h) (83). Regulations that eliminated

376 Singer · Vogus

Ann

u. R

ev. P

ublic

. Hea

lth. 2

013.

34:3

73-3

96. D

ownl

oade

d fr

om w

ww

.ann

ualr

evie

ws.

org

by V

ande

rbilt

Uni

vers

ity o

n 03

/21/

13. F

or p

erso

nal u

se o

nly.

PU34CH22-Singer ARI 13 February 2013 23:6

Table 1 Interventions designed to enable, enact, and elaborate safety culture and reduce hospital errors

Interventioncategory orsubdomain

Range and typesof studies Summary of findings

Examples of research gapsand further investigation

neededReferences forsample articles

EnablingExternalmotivators

There is littlesystematicinvestigation,but there aresome suggestivecase studies.

Accrediting bodies (the JointCommission), advocacyorganizations (e.g., the Institutefor Healthcare Improvement), andcollaboratives (e.g., PittsburghRegional Health Initiative) canspur the pursuit of safety andadoption of safer practices.

Influence of external motivatorson leader cognition and actionfrom direct, empiricalassessments

Effects of external motivators onnew practices and otherinnovations

Accreditation(27)

Collaboratives(143)

Internalmotivators:leadercharacteristicsand behaviors

Most studies usecross-sectionalsurvey designwith somecase-controlstudies.

Studies show leader practices (e.g.,executive WalkRounds),behaviors (e.g., inclusiveness), andcharacteristics (transformationalleadership) positively impactsafety climate.

Use different aspects of safetyclimate in multiple studies

Simultaneous examination ofleader characteristics andbehaviors

Identification of the conditionsunder which leader practicesare successful

LeadershipWalkRounds(38)

Transformationalleadership (92)

Leaderinclusiveness(105)

Internalmotivators:HR practices

Studiespredominantlyusecross-sectionalsurvey design.

Bundles of HR practices as well asindividual practices (e.g., staffinglevels) are associated with aspectsof safety climate and fewerhospital errors.

The use of consistent,dependent variables acrossstudies

Stronger research designs

Staffing (102)HR practices

(117)

Internalmotivator:informationtechnology

Most studies usea pre/post-interventiondesign.

Numerous casestudies alsoexist.

Studies of computerized physicianorder entry (a) showed mixedresults for adverse drug events, (b)showed a small positive effect onpatient safety, and (c) arepromising for bar codeverification and medicationreconciliation, but such studiesare limited.

Studies that explicitly measureand model organizationalcontext and organizationalreadiness for the use ofinformation technology

CPOE (93)Bar code

verification(116)

Internalmotivator:safety climate

Most studies havea cross-sectionalsurvey design.

There are somecase-controlinterventionstudies.

Consistent positive effects of asafety climate have been found ona range of outcomes related tohospital errors, includinginfections, treatment errors,patient safety indicators,readmissions, error reporting, andsafety grades. Safety climate variesacross units, professions, andorganizational levels, affectingoutcomes.

The use of similar specificationsof safety climate, i.e., surveyitems and modeling strategies

Longitudinal investigations toassess the effects of change onoutcomes and to documenthow hospitals can useinformation about safetyclimate to reduce hospitalerrors

Variation andrelationshipwith outcomes(57, 63)

EnactingEffectiveinterpersonal

Most studies arequasi

Selected interpersonal behaviors(mindful organizing and

Additional construct validationand differentiation of related

Relationalcoordination (7)

(Continued )

www.annualreviews.org • Reducing Hospital Errors 377

Ann

u. R

ev. P

ublic

. Hea

lth. 2

013.

34:3

73-3

96. D

ownl

oade

d fr

om w

ww

.ann

ualr

evie

ws.

org

by V

ande

rbilt

Uni

vers

ity o

n 03

/21/

13. F

or p

erso

nal u

se o

nly.

PU34CH22-Singer ARI 13 February 2013 23:6

Table 1 (Continued )

Interventioncategory orsubdomain

Range and typesof studies Summary of findings

Examples of research gapsand further investigation

neededReferences forsample articles

processes:teamwork,mindfulorganizing,relationalcoordination,and patientinvolvement

experimental withpre/post-testdesign.

Many arecontrolled.

Some use mixedmethods,incorporatinginterviewsalongside surveysor otherquantitativemeasures.

A few case studiesand qualitativestudies exist.

relational coordination) arerelated to preventing hospitalerrors and quality performance.

Ineffective interpersonalprocesses yield negativeconsequences, andorganizational conditions (e.g.,culture and human factors) andpractices (e.g., hiring, training,rewards) can promote moreeffective interpersonalprocesses.

Interventions to promote moreeffective teamwork improvequality, quantity, andperception of desiredbehaviors.

conceptsDirect evidence linking

interventions to reductions inmedical errors

Patientinvolvement(62)

Mindfulorganization(163)

Teamwork (166)

Reporting andvoicingconcerns

Studies have apredominantlycross-sectionalsurvey design.

Some arequestionnaire andsome scenariobased.

There are ahandful of casestudies andlongitudinal,pre/post-interventionstudies.

Substantial underreportingoccurs among clinicians.

Different reporting systems yieldcomplementary insights.

Conditions that promotereporting includepsychological safety,responsiveness, and closure.

Willingness to voice concernscorrelates with reducedhospital errors.

Additional research thatspecifically addresses effects ofreporting and voicing concernson learning and hospital errorsover time

Studies of the conditions underwhich learning is more likely tooccur

Complementaryinsights (80)

Underreporting(108)

Coordination atcare transitionsand acrossinterdependentfunctions:checklists,standardizedprotocols, andothers

There is a largemix of pre/post-interventionstudies,sometimescontrolled, and ahandful of casestudies andcross-sectionalobservationalstudies, with oneclaims-basedanalysis.

Checklists and structuredcommunication improve safepractices and reduce M&M;however, implementationvaries.

Longitudinal, randomized, andcontrolled studies ofintervention effectiveness

Studies that directly examinehow supportive (e.g., climate)and inhibiting conditionsinteract with specific protocolsto reduce hospital errors

Checklists (59)Hand overs (110)

(Continued )

378 Singer · Vogus

Ann

u. R

ev. P

ublic

. Hea

lth. 2

013.

34:3

73-3

96. D

ownl

oade

d fr

om w

ww

.ann

ualr

evie

ws.

org

by V

ande

rbilt

Uni

vers

ity o

n 03

/21/

13. F

or p

erso

nal u

se o

nly.

PU34CH22-Singer ARI 13 February 2013 23:6

Table 1 (Continued )

Interventioncategory orsubdomain

Range and typesof studies Summary of findings

Examples of research gapsand further investigation

neededReferences forsample articles

ElaboratingLearning-orientedinterventions

These studies arepredominantlycase controlled orqualitative with ahandful of cross-sectional surveystudies and asmall number oflongitudinalstudies.

Learning can improveperformance and preventfuture errors.

Studies identify facilitators (e.g.,psychological safety) andbarriers (e.g., ambiguousthreats) to learning andrecommend strategies thatpromote learning in groupsand organizations.

Descriptions of factors thatpromote or underminelearning

Identification of interventionsthat create the conditions thatpromote effective learning anddemonstrations of their abilityto reduce future errors

Investigations of how and underwhat conditions theseinterventions affect theprocesses of enabling andenacting

Longitudinalstudy (148)

Learning fromreported errors(150)

Education The studies are ofpredominantlypre-/posttestdesign with alarge number ofstudies taking amixed methodsapproach.Thereare a handful ofqualitativestudies.

Education is a populartechnique, alone or incombination with otherinterventions, to reducemedical errors.

Simulation is an increasinglypopular mode of education.

Multiple descriptive studiesStudies of the comparative

effectiveness of differingeducational interventions forshaping culture and reducinghospital errors over time

Studies of the organizationalfactors that enhance or inhibiteducational interventions

Education alone(47)

Multimodeincludingsimulation (140)

Operationalimprovements:industrialtechniques,frontlinesystemsimprovement,andinfrastructureimprovement

The studies arepredominantly ofpre-/posttestdesign, oftenemploying mixedmethods.

There are a fairnumber ofcross-sectionalsurvey studies anda limited numberof longitudinalstudies, oftenwith limitedsample sizes.

Hospitals have successfullyapplied principles fromindustrial production toimprove process reliability.

Frontline workers are uniquelypositioned to identify andresolve problems thatcontribute to hospital errorsbut tend to compensate forrather than resolve them.

Thus, frontline involvement insystemic improvement must befostered.

Internal committees andexternal collaboratives providemotivation and resources tosupport sustainedimprovement activity.

Such infrastructure has beenassociated with performanceimprovement.

Literature lacksinformation aboutcomprehensive, sustainableprograms that show howlongitudinal improvement canbe achieved

Studies involving infrastructureimprovements and their effectson hospital errors

Operationalimprovement(69)

Externalinfrastructure(104)

Internalinfrastructure(115)

Frontline systemimprovement(157)

(Continued )

www.annualreviews.org • Reducing Hospital Errors 379

Ann

u. R

ev. P

ublic

. Hea

lth. 2

013.

34:3

73-3

96. D

ownl

oade

d fr

om w

ww

.ann

ualr

evie

ws.

org

by V

ande

rbilt

Uni

vers

ity o

n 03

/21/

13. F

or p

erso

nal u

se o

nly.

PU34CH22-Singer ARI 13 February 2013 23:6

Table 1 (Continued )

Interventioncategory orsubdomain

Range and typesof studies Summary of findings

Examples of research gapsand further investigation

neededReferences forsample articles

Systemmonitoring:prospective,retrospective,and concurrentreviews

These studies ingeneral usecross-sectional,pre-/post-surveyor interventionlongitudinaldesigns withsome case studies.

Prospective (e.g., FMEA),retrospective (e.g., root causeanalysis, M&M), andconcurrent (e.g., compliancemonitoring) analyticalstrategies are used to identifyand prioritize the means toprevent future hazards.

Results often depend on whetherhospitals conduct theseactivities in a nonpunitivemanner.

Studies of direct evidence ofimpact on hospital errors

Studies of prospective andconcurrent processes forinfluencing safety culture andreducing errors

Concurrent (85)Prospective (94)Retrospective

(152)

Abbreviations: CPOE, computerized physician order entry; FMEA, failure mode and effects analysis; HR, human resources; M&M, mortality andmorbidity.

extended work shifts and reduced the number ofhours worked per week reduced attention fail-ures (84) and serious medical errors by interns(79), but subsequent duty-hour reforms havehad no impact on safety outcomes (126).

There is some evidence that using pub-lished research to guide practice (158) andongoing practitioner partnerships with leadingresearchers [e.g., Michigan’s Keystone Initia-tive (118)] builds safety culture and reduces hos-pital errors. There is also growing use of sur-veys to measure, motivate, and direct initiativesto improve safety climate and reduce hospitalerrors (107).

Internal Motivators

Leader characteristics and behaviors.Leader characteristics and behaviors work toreduce hospital errors through enabling andshaping perceptions of safety climate. Trans-formational leadership—providing an inspiringvision and fostering identification with it—isthe leader characteristic most strongly associ-ated with improving safety culture and safetyoutcomes (92), and transformational leadershipcan also be taught (96).

A wide array of leader behaviors and theirimpact on safety climate and hospital errors

have been explored. The personal practice ofleaders has a strong and consistent impact onsafety climate. For example, leaders who per-sonally disseminate safety information and pro-vide a model of safe behavior (6) improve safetyclimate. In addition, related leader behaviors,including attempts to change language [e.g., in-vestigations of errors becomes the analysis ofaccidents (31)] and be more inclusive of others(105), enhance employee engagement in cre-ating a safety culture (155). An empoweringleadership style (179) that includes coaching(32), dynamic delegation to junior members of ateam (71), and candid conversation among teammembers (135) also positively affects safetyculture.

Other specific interventions that featureleader behaviors include interactions withfrontline caregivers regarding patient safety is-sues, frontline safety forums (159), LeadershipWalkRoundsTM (38), patient safety rounding(87), and adopt-a-work unit (122). Zohar &Luria (184) experimented with a direct ap-proach for changing leader behavior andstrengthening safety climate. Specifically,frontline managers received weekly feedbackconcerning their safety-oriented interactionswith subordinates, and upper-level managers

380 Singer · Vogus

Ann

u. R

ev. P

ublic

. Hea

lth. 2

013.

34:3

73-3

96. D

ownl

oade

d fr

om w

ww

.ann

ualr

evie

ws.

org

by V

ande

rbilt

Uni

vers

ity o

n 03

/21/

13. F

or p

erso

nal u

se o

nly.

PU34CH22-Singer ARI 13 February 2013 23:6

received similar feedback as well as data onthe frequency of employees’ safety behaviors.Safety-oriented interaction increased bothmanager and employee ratings of safetyclimate. Safety climate is also improved byintegrated bundles of safety practices (e.g., thecomprehensive unit safety program), includingactive measurement of safety climate, safetyeducation, mechanisms for identifying andaddressing staff concerns, and extensive seniorexecutive involvement (e.g., adopt-a-work unitprograms) (121).

Human resource practices. Human resource(HR) practices create the conditions underwhich a skilled workforce is developed (e.g.,through careful selection, extensive and on-going training, and adequate staffing) to re-duce hospital errors and sufficiently empow-ered to capitalize on these skills. Such workpractices were shown to improve the qualityof information shared and to reduce medica-tion errors (117). A similar set of practiceswas associated with reductions in mortalityfrom errors (172). Additional research has fo-cused on the impact of a single HR practice(e.g., staffing/workload or training) on safetyclimate and hospital errors. Studies of nurse-to-patient ratios find that adequate staffing isassociated with fewer adverse events (2, 102).In contrast, less adequate staffing levels (in-dicated by workload, overtime, or increasednonregistered nurse hours of care) resulted inunexpected deaths (28) and medication errors(132).

Technology. Research has identified infor-mation technology as an important mechanismfor enabling safety culture, but at the sametime, its efficacy in reducing hospital errors isheavily dependent upon the organization’s cul-tural readiness to make use of it. Two of themost researched technologies are computer-ized physician order entry (CPOE) and elec-tronic medical records. Some large-scale stud-ies, simulations, and systematic reviews suggestthat implementation of such technologies re-mains slow, fatal orders are inconsistently de-

tected (93), and new errors are introduced byCPOE (75). However, there is also sugges-tive evidence that these systems can substan-tially reduce medication errors (67). Althougha recent review concluded that the effect ofCPOE on adverse drug events is mixed (175),others show that CPOE is an improvementover educational interventions (44). Electronicmedical records have been shown to have asmall positive effect on patient safety (113),whereas other information systems, includingelectronic medication reconciliation systems (1)and bar code verification technology (116), havedemonstrated stronger effects, albeit on a morelimited scale. The efficacy of such initiativesimportantly depends upon the organization’sreadiness to adopt the technology (147) and theimplementation process (77).

SAFETY CLIMATE

We treat safety climate as the key mecha-nism through which enabling promotes enact-ing and, in turn, safety. Specifically, we sug-gest that frontline provider interpretations ofsafety-relevant leader and organizational prac-tices constitute safety climate, and their per-ceptions of safety climate influence their safetybehaviors.

Safety climate perceptions are commonlytied to a local leader’s commitment to safety(e.g., through safety practices, procedures, andother resources committed to safety), prior-ity placed on safety (i.e., the extent to whichsafety is subordinated to other goals), anddissemination of safety information (66). Forexample, a supervisor who disregards safetyprocedures whenever production falls behindschedule or who punishes people for mis-takes signals a low commitment to safety(14). More recent research has expanded thedimensions of safety climate to include man-agement/supervisors, safety systems, risk per-ception, job demands, encouragement of re-porting/speaking up, safety attitudes/behaviors,communication/feedback, teamwork, personalresources (e.g., stress), and other organizationalfactors (36).

www.annualreviews.org • Reducing Hospital Errors 381

Ann

u. R

ev. P

ublic

. Hea

lth. 2

013.

34:3

73-3

96. D

ownl

oade

d fr

om w

ww

.ann

ualr

evie

ws.

org

by V

ande

rbilt

Uni

vers

ity o

n 03

/21/

13. F

or p

erso

nal u

se o

nly.

PU34CH22-Singer ARI 13 February 2013 23:6

Frontline staff perceptions of safety climatehave been found to predict fewer treatment er-rors, fewer infections (63), fewer readmissionsfor heart failure and acute myocardial infarctionpatients (57), lower incidences of preventablecomplications (141), and a better patient safetygrade (33).

The effects of a leader’s personal safety prac-tices on treatment errors are amplified whenthey are paired with an organization-wide pri-ority on safety (66). Safety climate, as indicatedby suitable safety procedures and clear informa-tion flow, reduced treatment errors only whenleaders emphasized safety and gave it a high pri-ority (100). Perception of a strong safety climateresults in improved safety performance becauseit increases safety motivation (i.e., willingnessto exert effort), participation in voluntary safetyactivities (e.g., helping coworkers with safety-related issues and attending safety meetings)(101), adherence to safety protocols, employeereporting of errors and incidents (99), and cre-ative problem solving (63, 141).

However, perceptions of safety climate arerarely shared across an organization. In fact, nu-merous studies find that the perception of safetyclimate varies based on one’s position in the or-ganizational hierarchy [i.e., administrators tendto see higher levels of safety climate than front-line caregivers (137)], professional affiliation[i.e., doctors perceive higher levels of safetyclimate than do nurses on dimensions such asteamwork and support/recognition of safety ef-forts (58)], and medical specialty or unit [e.g.,emergency department personnel perceive aweaker safety climate (138)]. Importantly, thediscrepancies in perceptions of safety climateare also consequential for safety outcomes. Forexample, frontline staff ’s perceptions of safetyclimate have been associated with patient safetyindicators, whereas those of senior managerswere not (127, 141).

ENACTING

Enacting a safety culture that reduces hospi-tal errors means frontline health care providersconsistently translate safety policies and guide-

lines into routine practice. Enacting safety cul-ture requires identifying and reducing latentand manifest threats to safety. To accomplishthis, organizations must confront communica-tion failures, including the failure to transmitinformation about vulnerabilities and mistakes.Research suggests that enacting a safety cul-ture reduces errors when enacting consists ofdeliberate efforts such as engaging caregiversand patients in effective interpersonal processes(i.e., teamwork, mindful organizing, and rela-tional coordination), promoting regular report-ing and voicing concerns, and deploying check-lists and standardized protocols to coordinatecare when transitions occur.

Interpersonal Processes

Teamwork. Teamwork among health careproviders is considered both an important com-ponent of a culture of safety and an essentialingredient for reducing medical errors. Defini-tions and frameworks for thinking about team-work are plentiful, as are measures of teamwork(160). Qualitative research has highlighted theconsequences of poor teamwork on hospital er-rors (151). Qualitative studies have also iden-tified conditions (129) and practices (41) thatinhibit or promote effective teamwork. In ad-dition, the literature describes a variety of in-terventions to improve teamwork. The mostprevalent of these are education-based teamtraining initiatives, such as crew resource man-agement (68) and TeamSTEPPS (166). Theyhave been found to positively impact the quan-tity and quality of communication and team-work behaviors as well as safety and team-work climates. These team training programs,which aim to cultivate enhanced communi-cation and coordination within teams, use avariety of intervention modalities, includingsimulation-based training (23). Training pro-grams may have a single focus (64) or havea multidisciplinary focus. Many programs in-clude teamwork training as an essential com-ponent of a multipronged program, combiningit with checklists (17), patient communication(10), leadership (109), and policy initiatives (5).

382 Singer · Vogus

Ann

u. R

ev. P

ublic

. Hea

lth. 2

013.

34:3

73-3

96. D

ownl

oade

d fr

om w

ww

.ann

ualr

evie

ws.

org

by V

ande

rbilt

Uni

vers

ity o

n 03

/21/

13. F

or p

erso

nal u

se o

nly.

PU34CH22-Singer ARI 13 February 2013 23:6

Mindful organizing. According to Weick &Sutcliffe (167), mindful organizing consists offive interrelated organizational processes: pre-occupation with failure, reluctance to simplifyinterpretations, sensitivity to operations, com-mitment to resilience, and deference to exper-tise. High-reliability organizations, which op-erate technically complex systems in a nearlyerror-free manner over long periods, enactthese processes (72). Case studies of organi-zational disasters suggest that the absence ofmindful organizing was a major contributingfactor (168). Consequently, developing mind-fulness among frontline workers to prevent er-rors becomes a priority (125). There have beenefforts to build mindful organizing in hospi-tal units (87) and to measure and improve itusing surveys (162). Evaluations have demon-strated that increased mindful organizing re-sults in fewer errors and patient falls (162), es-pecially when paired with trusted leaders andstructured protocols, e.g., care pathways (163).

Relational coordination. Relational coordi-nation is a term broadly encompassing strate-gies focused on improving communication andrelationships among individuals whose roles re-quire them to work together to integrate tasks(48). Studies have associated relational climatewith adherence to recommended practices (7).Adherence to protocols is associated with oper-ational reliability that makes error-free perfor-mance more likely. Some efforts have sought toimprove relational coordination (88) and to de-scribe conditions (e.g., use of HR practices) thatmake relational coordination more likely (49).Additional research suggests that relational co-ordination may be more important when taskand cognitive loads are greater (35).

Patient involvement. Long-standing re-search suggests that patients can play animportant role in reducing medical errors byhelping to more quickly detect and correct er-rors, but only if the organization is open to andsupportive of their involvement. Researchershave identified and assessed strategies foreffectively engaging patients that range from

having patients ask questions about their healthand treatment to actively managing and coordi-nating their own care (62, 170). They also haveidentified conditions that enhance the likeli-hood of successful patient involvement; theseinclude self-efficacy, preventability of incidents,and effective actions (131). Several studies haveexplored the potential for information tech-nologies to promote more effective patient-provider communication, suggesting the use oftechnology as a means to strengthen data gath-ering, diagnosis verification, and patient follow-up and monitoring among adults (142), partic-ularly for vulnerable populations (106). Studiesexploring the potential for patient involvementalso have examined the accuracy of patient-reported events with mixed results (146, 180).

Reporting and Voicing Concerns

The extensive literature on incident reportingsuggests that policy makers and practitionersbelieve this strategy has the potential for re-ducing medical errors. In fact, reporting anda reporting culture are seen as building blocksfor patient safety (74) and safety culture (124).Research in hospitals has examined the accu-racy, comprehensiveness, and sufficiency of re-porting; the information derived from report-ing; the conditions under which it occurs; andits effect on errors. Several scholars have pro-posed frameworks or typologies for detect-ing and reporting errors (128, 145). Variousstudies document substantial underreporting ofincidents among clinicians (108) and explorereasons for failing to report (61). Research com-paring information obtained through differentreporting systems (80) has found that the infor-mation obtained may be redundant (52). In themajority of instances, however, differentperspectives provide complementary insightsabout organizational safety, thus warrantinga portfolio of reporting systems. For exam-ple, communication problems were commonfrom patient complaints, whereas WalkRoundstended to identify issues with equipment andsupplies. A few papers look beyond incident re-porting by describing strategies for analyzing,

www.annualreviews.org • Reducing Hospital Errors 383

Ann

u. R

ev. P

ublic

. Hea

lth. 2

013.

34:3

73-3

96. D

ownl

oade

d fr

om w

ww

.ann

ualr

evie

ws.

org

by V

ande

rbilt

Uni

vers

ity o

n 03

/21/

13. F

or p

erso

nal u

se o

nly.

PU34CH22-Singer ARI 13 February 2013 23:6

addressing (43), and learning from (150) re-ported incidents. These papers highlight theneed for responsiveness and closure to reapbenefits from and cultivate continued report-ing. Additional studies have treated a clinician’swillingness to voice concerns as an independentvariable, correlating higher levels of voiced con-cerns with reduced hospital errors and otheroutcomes (99).

Coordinating at Care Transitions andAcross Interdependent Functions

Checklists. Among lessons the health caresector has learned from aviation is that check-lists have the potential to improve the con-sistency of safe practices as well as commu-nication and teamwork, thereby promotingerror-free results (45). Effective checklist use,however, requires the perception that the or-ganization embraces them (120). A growingbody of evidence suggests that checklists canimprove patient safety (73). Although com-monly applied in intensive care units (12) andsurgery (25, 59), studies also describe check-list use in emergency departments, acute caresettings, medication administration (44), andas part of multipronged programs (174). Inpractice, however, checklist use varies onceadopted, presenting an obstacle to derivingbenefits (98). A few studies explore barri-ers to checklist use (37) and characteristicsof implementation processes that promoteit, including the ability of leaders to persuasivelyexplain why and how to use the checklist (20).Other reports provide suggestions for develop-ing medical checklists (56) and describe surveysthat measure the factors associated with effec-tive checklist implementation (16).

Hand overs. The transition of patients be-tween care settings and the sequential exchangeof information between clinicians caring forthe same patients both present opportunitiesfor error and require effective management toavoid them. Evidence demonstrates that poorhand overs result in errors both within (97)and between (76) specialties. Interventions have

shown promise in improving hand overs by re-ducing information omissions, technical errors,and preventable adverse events include an ed-ucation curriculum (11), checklists (15), andstructured interdisciplinary rounds (110).

Others. Myriad additional opportunities existfor enacting a safety culture to reduce hospitalerrors (133). Research has shown that physi-cian participation is positively associated withimprovement in hospital patient safety indica-tors, but involvement by multiple hospital unitsin the improvement effort is associated withworse values on this and other quality measures(169). Efforts specifically focused on standard-izing aspects of health care delivery also havebeen shown to reduce errors (177). In addition,studies have demonstrated potential benefits forpatient safety from time management (3), riskmanagement (13), and remediation, i.e., disclo-sure (40) and apology (60). The literature alsohighlights common conditions that contributeto the inability of hospitals to reduce errors,such as health care worker stress and burnout(173) and the practice of work-arounds (55).

ELABORATING

Elaborating a safety culture is the systematicprocess of reflecting and translating prior ex-perience to spread and refine manager andfrontline employee safety-oriented behaviorsand practices that have been previously en-abled and enacted. Elaboration refers to theevolutionary expansion of these behaviors andpractices, preferably characterized by increas-ing tolerance for them and growing capabili-ties for addressing complications that may ac-company them. Interventions that promote theelaboration of a safety culture include those thatpromote learning, education, operational im-provement, and system monitoring.

Learning-Oriented Interventions

Learning from small failures through experi-mentation presents health care organizationswith the opportunity to prevent problems that

384 Singer · Vogus

Ann

u. R

ev. P

ublic

. Hea

lth. 2

013.

34:3

73-3

96. D

ownl

oade

d fr

om w

ww

.ann

ualr

evie

ws.

org

by V

ande

rbilt

Uni

vers

ity o

n 03

/21/

13. F

or p

erso

nal u

se o

nly.

PU34CH22-Singer ARI 13 February 2013 23:6

have the potential to cause patient deaths (144).Learning also has been credited with the suc-cessful transfer and retention of best prac-tices (8). Considerable attention has been givento identifying the facilitators of learning fromerrors, and most notable among them is psycho-logical safety—a belief that the group environ-ment is safe for taking interpersonal risks (29).Studies also have identified barriers to learning(153) and conditions under which learning isless likely, such as when a problem is ambiguous(30). Organizations may learn from frontlineworkers’ complaints about operational prob-lems (157), briefings and debriefings (161), inci-dent reporting systems (86, 150), and mortalityand morbidity (M&M) conferences (111). Sur-vey measures also provide organizations withopportunities to assess the extent to which theyare learning organizations (139) and learn fromreported events (46).

Education

Education is a popular feature of many inter-ventions designed to reduce hospital errors.Several interventions have used educational ini-tiatives to promote safety culture, some withpositive effects (47). Education is frequentlya component of multipronged interventionsand has been used in combination with team-work, leadership, frontline system improve-ment, technology, incident reporting, patientpartnership, checklists, and measurement andfeedback programs to improve safety culture(5, 118). More specifically, simulation is be-coming an increasingly popular mode for in-troducing practices and processes for shapingsafety culture and reducing hospital errors, butcurrent evidence of its effects is mixed (22,23, 81). Studies have identified how safety andteam-based training for medical students (70),frontline caregivers (125), and leaders (140)changes behavior (e.g., more learning oriented)and reinforces safety culture. They also havedemonstrated that, in the context of academicmedicine, faculty and students must manage atrade-off between education and patient safety(95).

Operational Improvements

Industrial techniques. Recognizing that op-erational failures can contribute not only to ex-cess costs but also to safety problems, expertsrecommend applying principles from industrialproduction for clarifying and streamlining op-erations and reducing controllable variations toenhance reliability and reduce hospital errors(82). Such techniques, including the ToyotaProduction System and lean manufacturingprinciples, have been successfully implementedacross organizations, notably at the VirginiaMason Medical Center in Seattle (69) andThedaCare Appleton Medical Center in Apple-ton, Wisconsin (154). Evidence suggests theseprograms have improved problem resolution(39) and the timeliness and reliability of careprocesses (178).

Frontline system improvement. Given theunique and expert perspective of frontlineworkers on safety hazards in hospitals (159),scholars and policy makers advocate training,trusting, and supporting them to identifyand resolve safety problems (9). Studiespresent models for understanding frontlineproblem-solving behavior (157) and programsfor identifying and monitoring problems toimprove problem solving and patient safety(149). They also describe how improvementefforts can reduce work-arounds (54) and im-prove policy compliance (89). Frontline systemimprovement often plays a prominent role inmultipronged approaches, such as the compre-hensive unit safety program, which has beencredited with improvements in safety culture(118). However, substantial research alsosuggests frontline system improvement mustbe fostered because frontline workers tend tocompensate for failures rather than treat themas learning opportunities (156). Leadershipturnover can also undermine improvementinitiatives (115).

Improvement infrastructure. Research alsohighlights the importance of maintaining theinfrastructure to support safety initiatives

www.annualreviews.org • Reducing Hospital Errors 385

Ann

u. R

ev. P

ublic

. Hea

lth. 2

013.

34:3

73-3

96. D

ownl

oade

d fr

om w

ww

.ann

ualr

evie

ws.

org

by V

ande

rbilt

Uni

vers

ity o

n 03

/21/

13. F

or p

erso

nal u

se o

nly.

PU34CH22-Singer ARI 13 February 2013 23:6

because it is necessary to catalyze, execute,and sustain efforts to reduce hospital errors.Internally focused, safety-oriented committeesprovide a systematic approach to identifyingand supporting efforts to improve and main-tain safety and safety culture (115). Similarly,externally driven improvement collaborativesprovide participants with a forum, motiva-tion, and social support as well as projectmanagement and process-improvement skillsto execute improvement activities in their or-ganizations (103). Collaborative approachesalso have been recommended for the pri-oritization and resolution of safety hazardsthat lend themselves to industry-wide so-lutions (119). Research shows that perfor-mance improvement increases with the use ofboth internal and external learning activities(104).

System Monitoring

The literature describes a variety of strategies—prospective, retrospective, and concurrent—forenriching our understanding of delivery sys-tems and promoting a safety climate and safepractices throughout an organization.

Prospective review. Prospective strategiesinclude failure mode and effects analysis(FMEA), prospective hazard analysis, and hu-man factors engineering. FMEA and otherforms of prospective hazard analysis ask prac-titioners to identify potential hazards and ratetheir severity and likelihood to design processesthat prevent them. These techniques have beenapplied to a broad range of care processes alone(26) and as part of multipronged programs(136), used to prioritize interventions (65), andcredited with reducing medical errors (94). Hu-man factors engineering applies an understand-ing of the cognitive and behavioral limitationsof human beings to system design. Studies havedemonstrated the ability of this discipline todevelop safe, comfortable, and effective equip-ment and systems through iterative tests andrefinements (51).

Retrospective review. Retrospective analy-sis in hospitals usually takes the form of rootcause analysis, a structured approach to identi-fying the factors that resulted in a harmful out-come. Predicated on the belief that addressingthe causes of past problems may prevent fu-ture problems, studies have demonstrated theimportance of conducting these analyses toidentify multiple approaches and shape clini-cian workflow in the name of reducing hos-pital errors (42). These are often combinedwith stories of dramatic events that can en-gage clinicians to consider the system prob-lems that cause them, thus reinforcing a safetyculture. For example, the long-standing Annalsof Medicine case-based series, the Agency forHealthcare Research and Quality-sponsored“WebM&M,” and M&M rounds have engagedcaregivers in disclosing and collective learningfrom specific events (165). M&M conferencesare also widespread among teaching hospitals(112). However, many clinicians are reluctantto openly discuss errors in a conference setting(114). Research has offered suggestions for pro-moting enhanced learning from M&M confer-ences (111, 112), including making the organi-zation’s stance toward errors explicit, selectingcases that present learning opportunities, usingskilled moderators to facilitate discussion, en-couraging broad attendance, and focusing ongeneralizable lessons. Implementing such pro-grams has been associated with improvement insafety climate (152).

Concurrent review. Compliance monitoringis a form of concurrent analysis involving thecollection and analysis of information on theperformance of programs or protocols fol-lowing initial implementation. Studies havedemonstrated methods for compliance moni-toring (e.g., real-time, clandestine observation)and their value for continuous improvement ofcare processes and protocols (85).

DISCUSSION

In this review, we distilled research on interven-tions to reduce hospital errors into a framework

386 Singer · Vogus

Ann

u. R

ev. P

ublic

. Hea

lth. 2

013.

34:3

73-3

96. D

ownl

oade

d fr

om w

ww

.ann

ualr

evie

ws.

org

by V

ande

rbilt

Uni

vers

ity o

n 03

/21/

13. F

or p

erso

nal u

se o

nly.

PU34CH22-Singer ARI 13 February 2013 23:6

that captures the varied ways in which they op-erate through processes of enabling, enacting,or elaborating a safety culture. Although theassembled evidence suggests support for theeffects of interventions on safety climate andsafety culture, evidence is weaker for reducinghospital errors. As identified in earlier reviews(176), this is undoubtedly, in part, a functionof the organizational and systemic natureof hospital errors, which makes it difficult toconceptualize and measure them and erects nu-merous barriers to implementing interventions.

At the same time, the modest effects of var-ied interventions on reducing hospital errorssuggest a key contribution of our review: rec-ognizing that the systematic pursuit of en-abling, enacting, and elaborating—not isolatedinterventions—offers the greatest potential forreducing hospital errors. In addition, as ouradapted conceptual model implies, a hospitalcan never be fully error free. However, ongo-ing and iterative processes of enabling, enact-ing, and elaborating a safety culture can reduceand minimize hospital errors.

Implications for Research and Practice

The main implication of our adapted concep-tual model is that the starting point for con-sidering future interventions should resemblewhat we have identified as multipronged ap-proaches. These would intentionally addressthe organization’s ability to enable, enact, andelaborate a safety culture rather than focus onjust one of these areas. For example, if an or-ganization or unit was going to intervene to in-crease teamwork (which we have identified asa form of enacting), it would mean consideringhow teamwork could be enabled through leadersupport and organizational practices (e.g., ad-equate staffing to allow for training and otherexercises during work hours) and how it couldbe elaborated by disseminating the plan to othergroups and refining the intervention over time.Once initiated, teamwork interventions mightbe further enabled by policies that reward team-based care. This interpretation of our modelalso suggests a more holistic approach to asking

research questions and the means of answeringthem.

Another important implication of ouradapted model is that interventions will be moresuccessful when implemented in a culturallysensitive manner. Not all interventions will beuseful and appropriate in all settings (a po-tentially important explanation for the mixedfindings observed for many interventions). Theability to discover interventions that can workwithin an organization’s existing culture relieson, and is an underappreciated aspect of, leader-ship. It requires understanding the fundamen-tal mechanisms through which the interventionis expected to achieve change and reconcilingthese to the basic shared beliefs and assump-tions held by organizational members. This im-plication is consistent with studies that haveexplained previous failures to spread improve-ment interventions (e.g., total quality manage-ment) as a result of leaders’ failures to funda-mentally change the motivational structure ofthe work (53).

Above, we have described the large andgrowing literature on safety climate as bridg-ing the enabling and enacting of a safety cul-ture. One persistent finding in this literature isthat an organization-level safety climate is elu-sive. Instead, there is considerable evidence thatclimate is fragmented across professions, orga-nizational levels, and organizational subunits.This raises the important question of when (ifever) a hospital-level safety climate (and cul-ture) emerges. Are climate perceptions morelikely to be shared when many, if not all, of theenabling conditions we identified are present?Or are some factors (e.g., leader practices) es-pecially important?

Lastly, Table 1 suggests a number of impor-tant research questions, the answers to whichwill further refine the proposed model andbetter establish the linkages among interven-tions, culture, and hospital errors. For exam-ple, we need more systematic research on ex-ternal motivators. What external actors or poli-cies motivate hospitals to pursue efforts thathave demonstrated impacts on reducing hos-pital errors? Future research should also more

www.annualreviews.org • Reducing Hospital Errors 387

Ann

u. R

ev. P

ublic

. Hea

lth. 2

013.

34:3

73-3

96. D

ownl

oade

d fr

om w

ww

.ann

ualr

evie

ws.

org

by V

ande

rbilt

Uni

vers

ity o

n 03

/21/

13. F

or p

erso

nal u

se o

nly.

PU34CH22-Singer ARI 13 February 2013 23:6

carefully and consistently operationalize a num-ber of the concepts we identified in our model,including safety climate, HR practices, andteamwork.

In addition, as previously established (34,176), our review finds that a rigorous, quantita-tive demonstration of the relationship betweenan intervention and outcomes remains rare.Although one could easily dismiss researchdesigns other than randomized clinical trialsas less rigorous and call for stronger analyticalmethods for evaluation, our investigation sug-gests some caveats to this typical conclusion.Our model suggests that intervening in waysthat are sensitive to the existing culture and thatattempt to shape the culture through system-ically enabling, enacting, and elaborating willbe most effective. Holding organizational in-terventions to a “gold standard” could result inthe application of validated interventions thatneither fit a particular organization nor spanthe full enabling, enacting, and elaboratingcycle. Quantitative studies of the relationshipsbetween interventions and outcomes, espe-cially when controlling for prior performancethrough structural equation modeling orother rigorous approaches, should constitute

evidence for diffusing an intervention underappropriate conditions. Combining these stud-ies with those that directly assess the contextualconditions under which interventions—fromvoice to leadership behaviors to educationand learning—are most effective for reducinghospital errors (i.e., moderators that enhancethe relationship) is also needed. Finally, weneed additional longitudinal, mixed methodsand qualitative investigations—includingethnography and case comparisons—thatidentify the mechanisms through which anintervention leads to fewer hospital errors.

CONCLUSION

Faced with the persistent challenge of hospi-tal errors, policy makers and practitioners needguidance regarding how to achieve improve-ment. We have argued that piecemeal initiativesare inadequate and that strengthening safetyculture necessitates interventions that simul-taneously enable, enact, and elaborate it in away that is attuned to the existing culture. Thisapproach may hold the key to demonstrablyreducing hospital errors and ultimately savinglives.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The authors are not aware of any affiliations, memberships, funding, or financial holdings thatmight be perceived as affecting the objectivity of this review.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors thank Ingrid Nembhard and Kathleen Sutcliffe for comments that substantiallyimproved the contribution and clarity of our paper. We also thank Mathew Kiang for his expertresearch assistance.

LITERATURE CITED

1. Agarwal S, Frankel L, Tourner S, McMillan A, Sharek PJ. 2008. Improving communication in a pediatricintensive care unit using daily patient goal sheets. J. Crit. Care 23:227–35

2. Aiken L, Clarke S, Sloane D, Sochalski J, Silber J. 2002. Hospital nurse staffing and patient mortality,nurse burnout, and job dissatisfaction. JAMA 288(16):1987–93

3. Amalberti R, Brami J. 2012. “Tempos” management in primary care: a key factor for classifying adverseevents, and improving quality and safety. BMJ Qual. Saf. 21:729–36

4. Annas GJ. 2006. The patient’s right to safety—improving the quality of care through litigation againsthospitals. N. Engl. J. Med. 354(19):2063–66

388 Singer · Vogus

Ann

u. R

ev. P

ublic

. Hea

lth. 2

013.

34:3

73-3

96. D

ownl

oade

d fr

om w

ww

.ann

ualr

evie

ws.

org

by V

ande

rbilt

Uni

vers

ity o

n 03

/21/

13. F

or p

erso

nal u

se o

nly.

PU34CH22-Singer ARI 13 February 2013 23:6

5. Arriaga AF, Elbardissi AW, Regenbogen SE, Greenberg CC, Berry WR, et al. 2011. A policy-basedintervention for the reduction of communication breakdowns in inpatient surgical care: results from aHarvard surgical safety collaborative. Ann. Surg. 253(5):849–54

6. Barling J, Loughlin C, Kelloway EK. 2002. Development and test of a model linking safety-specifictransformational leadership and occupational safety. J. Appl. Psychol. 87(3):488–96

7. Benzer JK, Young G, Stolzmann K, Osatuke K, Meterko M, et al. 2011. The relationship betweenorganizational climate and quality of chronic disease management. Health Serv. Res. 46(3):691–711

8. Berta WB, Baker R. 2004. Factors that impact the transfer and retention of best practices for reducingerror in hospitals. Health Care Manag. Rev. 29(2):90–97

9. Berwick DM. 2003. Improvement, trust, and the healthcare workforce. Qual. Saf. Health Care 12(6):448–52

10. Blegen MA, Sehgal NL, Alldredge BK, Gearhart S, Auerbach AA, Wachter RM. 2010. Improving safetyculture on adult medical units through multidisciplinary teamwork and communication interventions:the TOPS Project. Qual. Saf. Health Care 19(4):346–50

11. Bray-Hall S, Schmidt K, Aagaard E. 2010. Toward safe hospital discharge: a transitions in care curriculumfor medical students. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 25(8):878–81

12. Byrnes M, Schuerer D, Schallom M, Sona C, Mazuski J, et al. 2009. Implementation of a mandatorychecklist of protocols and objectives improves compliance with a wide range of evidence-based intensivecare unit practices. Crit. Care Med. 37:2775–81

13. Cagliano AC, Grimaldi S, Rafele C. 2011. A systemic methodology for risk management in healthcaresector. Saf. Sci. 49(5):695–708

14. Carroll J, Quijada M. 2004. Redirecting traditional professional values to support safety: changing or-ganisational culture in health care. Qual. Saf. Health Care 13(Suppl. 2):ii16–21

15. Catchpole K, de Leval M, McEwan A, Pigott N, Elliott M, et al. 2007. Patient handover from surgeryto intensive care: using Formula 1 pit-stop and aviation models to improve safety and quality. Paediatr.Anaesth. 17(5):470–78

16. Chan KS, Hsu Y-J, Lubomski LH, Marsteller JA. 2011. Validity and usefulness of members reports ofimplementation progress in a quality improvement initiative: findings from the Team Check-up Tool(TCT). Implement. Sci. 6:115

17. Chase D, McCarthy D. 2010. Case study: sustaining a culture of safety in the U.S. Department of VeteransAffairs Health Care System. Commw. Fund Rep. Quality Matters. http://www.commonwealthfund.org/Newsletters/Quality-Matters/2010/April-May-2010/Case-Study.aspx

18. Classen DC, Resar R, Griffin F, Federico F, Frankel T, et al. 2011. “Global trigger tool” shows thatadverse events in hospitals may be ten times greater than previously measured. Health Aff. 30(4):581–89

19. Comm. Qual. Health Care Am. 2001. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21stCentury. Washington, DC: Inst. Med./Natl. Acad. Press

20. Conley DM, Singer SJ, Edmondson L, Berry WR, Gawande AA. 2011. Effective surgical safety checklistimplementation. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 212(5):873–79

21. Cook R, Rasmussen J. 2005. “Going solid”: a model of system dynamics and consequences for patientsafety. Qual. Saf. Health Care 14:130–34

22. Cooper JB, Singer SJ, Hayes J, Sales M, Vogt J, et al. 2011. Design and evaluation of simulation scenariosfor a program introducing patient safety, teamwork, safety leadership and simulation to healthcare leadersand managers. Simul. Healthc. 6(4):231–38

23. Cooper JB, Blum RH, Carroll JS, Dershwitz M, Feinstein DM, et al. 2008. Differences in safety climateamong hospital anesthesia departments and the effect of a realistic simulation-based training program.Anesth. Analg. 106(2):574–84

24. Davis P, Lay-Yee R, Briant R, Scott A. 2003. Preventable in-hospital medical injury under the “no fault”system in New Zealand. Qual. Saf. Health Care 12(4):251–56

25. de Vries EN, Prins HA, Crolla RMPH, Outer den AJ, van Andel G, et al. 2010. Effect of a comprehensivesurgical safety system on patient outcomes. N. Eng. J. Med. 363(20):1928–37

26. Dean JE, Hutchinson A, Escoto KH, Lawson R. 2007. Using a multi-method, user centred, prospectivehazard analysis to assess care quality and patient safety in a care pathway. BMC Health Serv. Res. 7:89

www.annualreviews.org • Reducing Hospital Errors 389

Ann

u. R

ev. P

ublic

. Hea

lth. 2

013.

34:3

73-3

96. D

ownl

oade

d fr

om w

ww

.ann

ualr

evie

ws.

org

by V

ande

rbilt

Uni

vers

ity o

n 03

/21/

13. F

or p

erso

nal u

se o

nly.

PU34CH22-Singer ARI 13 February 2013 23:6

27. Devers KJ, Pham HH, Liu G. 2004. What is driving hospitals’ patient-safety efforts? Health Aff. 23(2):103–15

28. Diwas S, Terwiesch C. 2009. Impact of workload on service time and patient safety: an econometricanalysis of hospital operations. Manag. Sci. 55(9):1486–98

29. Edmondson A, Cannon M. 2005. Failing to learn and learning to fail (intelligently): how great organi-zations put failure to work to improve and innovate. Long Range Plan. 38(3):299–319

30. Edmondson A, Roberto MA, Bohmer RM, Ferlins EM, Feldman L. 2004. The recovery window: orga-nizational learning following ambiguous threats in high-risk organizations. In Organization at the Limit:NASA and the Columbia Disaster, ed. M Farjoun, WH Starbuck. London: Blackwell

31. Edmondson AC. 2004. Learning from mistakes is easier said than done: group and organizational influ-ences on the detection and correction of human error. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 40(1):66–90

32. Edmondson AC, Bohmer RM, Pisano GP. 2001. Disrupted routines: team learning and new technologyimplementation in hospitals. Adm. Sci. Q. 46(4):685–716

33. El-Jardali F, Dimassi H, Jamal D, Jaafar M, Hemadeh N. 2011. Predictors and outcomes of patient safetyculture in hospitals. BMC Health Serv. Res. 11:45

34. Etchells E, Koo M, Daneman N, McDonald A, Baker M, et al. 2012. Comparative economic analysesof patient safety improvement strategies in acute care: a systematic review. BMJ Qual. Saf. 21(6):448–56

35. Faraj S, Xiao Y. 2006. Coordination in fast-response organizations. Manag. Sci. 52(8):1155–6936. Flin R, Burns C, Mearns K, Yule S, Robertson EM. 2006. Measuring safety climate in health care. Qual.

Saf. Health Care 15(2):109–1537. Fourcade A, Blache JL, Grenier C, Bourgain JL, Minvielle E. 2012. Barriers to staff adoption of a surgical

safety checklist. BMJ Qual. Saf. 21(3):191–9738. Frankel A, Pratt Grillo S, Pittman M, Thomas EJ, Horowitz L, et al. 2008. Revealing and resolving

patient safety defects: the impact of leadership WalkRounds on frontline caregiver assessments of patientsafety. Health Serv. Res. 43(6):2050–66

39. Furman C, Caplan R. 2007. Applying the Toyota Production System: using a patient safety alert systemto reduce error. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Patient Saf. 33(7):376–86

40. Gallagher TH, Studdert D, Levinson W. 2007. Disclosing harmful medical errors to patients. N. Engl.J. Med. 356(26):2713–19

41. Gandhi TK, Graydon-Baker E, Barnes JN, Neppl C, Stapinski C, et al. 2003. Creating an integratedpatient safety team. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Saf. 29(8):383–90

42. Gandhi TK, Zuccotti G, Lee TH. 2011. Incomplete care—on the trail of flaws in the system. N. Engl.J. Med. 365(6):486–88

43. Gandhi T, Graydon-Baker E, Huber C, Whittemore A, Gustafson M. 2005. Closing the loop: follow-upand feedback in a patient safety program. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Patient Saf. 31(11):614–21

44. Garbutt J, Milligan PE, McNaughton C, Highstein G, Waterman BM, et al. 2008. Reducing medicationprescribing errors in a teaching hospital. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Patient Saf. 34(9):528–36

45. Gawande A. 2009. The Checklist Manifesto: How to Get Things Right. New York: Metrop. Books46. Ginsburg LR, Chuang Y-T, Norton PG, Berta W, Tregunno D, et al. 2009. Development of a measure

of patient safety event learning responses. Health Serv. Res. 44(6):2123–4747. Ginsburg L, Norton PG, Casebeer A, Lewis S. 2005. An educational intervention to enhance nurse

leaders’ perceptions of patient safety culture. Health Serv. Res. 40(4):997–102048. Gittell J. 2003. The Southwest Airlines Way: Using the Power of Relationships to Achieve High Performance.

New York: McGraw-Hill49. Gittell JH, Seidner R, Wimbush J. 2010. A relational model of how high-performance work systems

work. Organ. Sci. 21(2):490–50650. Goodman PS, Ramanujam R, Carroll JS, Edmondson AC, Hofmann DA, Sutcliffe KM. 2011. Organi-

zational errors: directions for future research. Res. Organ. Behav. 31:151–7651. Gosbee J. 2002. Human factors engineering and patient safety. Qual. Saf. Health Care 11(4):352–5452. Grissinger MC, Hicks RW, Keroack MA, Marella WM, Vaida AJ. 2010. Harmful medication errors

involving unfractionated and low-molecular-weight heparin in three patient safety reporting programs.Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Patient Saf. 36(5):195–202

390 Singer · Vogus

Ann

u. R

ev. P

ublic

. Hea

lth. 2

013.

34:3

73-3

96. D

ownl

oade

d fr

om w

ww

.ann

ualr

evie

ws.

org

by V

ande

rbilt

Uni

vers

ity o

n 03

/21/

13. F

or p

erso

nal u

se o

nly.

PU34CH22-Singer ARI 13 February 2013 23:6

53. Hackman JR, Wageman R. 1995. Total quality management: empirical, conceptual, and practical issues.Adm. Sci. Q. 40(2):309–42

54. Halbesleben JRB, Rathert C. 2008. The role of continuous quality improvement and psychological safetyin predicting work-arounds. Health Care Manag. Rev. 33(2):134–44

55. Halbesleben JRB, Savage GT, Wakefield DS, Wakefield BJ. 2010. Rework and workarounds in nursemedication administration process: implications for work processes and patient safety. Health Care Manag.Rev. 35(2):124–33

56. Hales B, Terblanche M, Fowler R, Sibbald W. 2007. Development of medical checklists for improvedquality of patient care. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 20:22–30

57. Hansen LO, Williams MV, Singer SJ. 2010. Perceptions of hospital safety climate and incidence ofreadmission. Health Serv. Res. 42(2):596–616

58. Hartmann CW, Rosen AK, Meterko M, Shokeen P, Zhao S, et al. 2008. An overview of patient safetyclimate in the VA. Health Serv. Res. 43(4):1263–84

59. Haynes AB, Weiser TG, Berry WR, Lipsitz SR, Breizat A-HS, et al. 2009. A surgical safety checklist toreduce morbidity and mortality in a global population. N. Eng. J. Med. 360(5):491–99

60. Helmchen LA, Richards MR, McDonald TB. 2011. Successful remediation of patient safety incidents:a tale of two medication errors. Health Care Manag. Rev. 36(2):114–23

61. Henriksen K, Dayton E. 2006. Organizational silence and hidden threats to patient safety. Health Serv.Res. 41(4p2):1539–54

62. Hibbard JH, Peters E, Slovic P, Tusler M. 2005. Can patients be part of the solution? Views on theirrole in preventing medical errors. Med. Care Res. Rev. 62(5):601–16

63. Hofmann DA, Mark B. 2006. An investigation of the relationship between safety climate and medicationerrors as well as other nurse and patient outcomes. Pers. Psychol. 59(4):847–69

64. Kalisch BJ, Curley M, Stefanov S. 2007. An intervention to enhance nursing staff teamwork and engage-ment. J. Nurs. Adm. 37(2):77–84

65. Karnon J, McIntosh A, Dean J, Bath P, Hutchinson A, et al. 2007. A prospective hazard and improvementanalytic approach to predicting the effectiveness of medication error interventions. Saf. Sci. 45(4):523–39

66. Katz-Navon T, Naveh E, Stern Z. 2005. Safety climate in healthcare organizations: a multidimensionalapproach. Acad. Manag. J. 48(6):1075–89

67. Kaushal R, Shojania KG, Bates DW. 2003. Effects of computerized physician order entry and clinicaldecision support systems on medication safety: a systematic review. Arch. Intern. Med. 163(12):1409–16

68. Kemper PF, de Bruijne M, van Dyck C, Wagner C. 2011. Effectiveness of classroom based crew resourcemanagement training in the intensive care unit: study design of a controlled trial. BMC Health Serv. Res.11(1):304

69. Kenney C. 2011. Transforming Health Care: Virginia Mason Medical Center’s Pursuit of the Perfect PatientExperience. New York: Productivity

70. Kirch DG, Boysen PG. 2010. Changing the culture in medical education to teach patient safety. HealthAff. 29(9):1600–4

71. Klein KJ, Ziegert JC, Knight AP, Xiao Y. 2006. Dynamic delegation: shared, hierarchical, and deindi-vidualized leadership in extreme action teams. Adm. Sci. Q. 51(4):590–621

72. Knox G, Simpson K, Garite T. 1999. High reliability perinatal units: an approach to the prevention ofpatient injury and medical malpractice claims. J. Healthc. Risk Manag. 19(2):24–32

73. Ko H, Turner T, Finnigan M. 2011. Systematic review of safety checklists for use by medical care teamsin acute hospital settings—limited evidence of effectiveness. BMC Health Serv. Res. 11(1):211

74. Kohn LT, Corrigan J, Donaldson MS, eds. 2000. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System.Washington, DC: Inst. Med./Natl. Acad. Press

75. Koppel R, Metlay JP, Cohen A, Abaluck B, Localio AR, et al. 2005. Role of computerized physicianorder entry systems in facilitating medication errors. JAMA 293(10):1197–203

76. Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW. 2007. Deficits in commu-nication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications forpatient safety and continuity of care. JAMA 297(8):831–41

77. Kuperman GJ, Bobb A, Payne TH, Avery AJ, Gandhi TK, et al. 2007. Medication-related clinical decisionsupport in computerized provider order entry systems: a review. J. Am Med. Inform. Assoc. 14(1):29–40

www.annualreviews.org • Reducing Hospital Errors 391

Ann

u. R

ev. P

ublic

. Hea

lth. 2

013.

34:3

73-3

96. D

ownl

oade

d fr

om w

ww

.ann

ualr

evie

ws.

org

by V

ande

rbilt

Uni

vers

ity o

n 03

/21/

13. F