The developmentof early imperial dress from the Tetrachs to ...

A Proper Dress Length for Little Girls? Soviet Taste, Girls’ Innocence, and Children’s Fashion...

-

Upload

kunstkamera -

Category

Documents

-

view

2 -

download

0

Transcript of A Proper Dress Length for Little Girls? Soviet Taste, Girls’ Innocence, and Children’s Fashion...

A Proper Dress Length for Little Girls?Soviet Taste, Girls’ Innocence, and

Children’s Fashion in Contemporary Russia

Olga Boitsova and Elena Mishanova

ABSTRACTIn this article we present the results of research on children’s fashion in contem-porary Russia. Our premise is that what is known as individual taste and universaltraditions are determined socially. The ways in which parents dress their daughtersconvey messages about girlhood. Short dresses for girls in so-called Soviet tastecan still be seen in Russia nowadays, along with examples of a new Western trendof apparently protecting girls by dressing them in long dresses, skorts (hybridsthat combine the features of skirts and shorts), swimsuits, and leggings worn underskirts. In this article we discuss two trends in girls’ wear that reflect two differentconceptions of what counts as girls’ innocence. We suggest that these are tied tosocietal changes in the country.

KEYWORDSdress length, fashion studies, innocence, preschool children, sociology of taste,Soviet taste

Introduction

Our aim in this article is to reveal some of the trends in the ways in whichpeople who take care of girls dress them, and to describe and explain thesetrends and trace their roots in history. Our premise is that what is seen tobe suitable and appropriate clothing for girls varies in societies and acrosshistory. The question we are interested in has to do with why people in con-temporary Russia dress their daughters as they do.

To answer this question, we have to approach the complex topic of chil-dren’s fashion but studying children’s fashion as a research object is challeng-ing because of its invisibility. Unlike adult fashion, it does not exist in publicdiscourse. Instructions on clothes for children in childcare literature focuson health and comfort and hardly ever consider issues of fashion and even

Girlhood Studies 8, no. 1 (Spring 2015): 42-59 © Berghahn Journalsdoi: 10.3167/ghs.2015.080105 ISSN: 1938-8209 (print) 1938-8322 (online)

a

b

05-Boitsova:Layout 1 5/7/15 2:13 PM Page 42

decency, except to offer verbiage on the necessity to develop good taste inchildren from birth. What is claimed in fashionable magazines to be the lat-est trends in children’s fashion turn out to be advertising discourse advo-cating the same cuts and hues every year. We suggest that trends in children’sapparel may be seen in everyday wear rather than in glamorous clothing.Interest in these very trends is at the center of our research.

Methodology

The disciplinary framework of our research is the sociology of taste (seeBourdieu 1984; Gronow 1997). Our basic assumption is that taste issocially constructed and deeply rooted in history. We analyzed historicaltrends in girls’ fashion on the basis of a variety of sources, both writtenand pictorial. An important characteristic of visual material in comparisonwith verbal is that the former may sometimes incorporate contradictionsand hidden conflicts which are not expressed in words (Kivelson and Neuberger 2008).

Our main source of data for contemporary practices of dressing chil-dren and for judgments of adults such as parents and caretakers was a surveywe conducted among Russian-speaking Internet users from differentregions. We collected 576 answers to the survey. We posted a link to thesurvey on Internet sites designed with communication between and amongyoung parents in mind. These were online forums in St. Petersburg,1 Yeka-terinburg,2 Volgograd,3 Novosibirsk4 and other cities.5 Thus, our respon-dents were men and women with children living in large and medium-sizedRussian cities.6 The questionnaire offered 27 descriptions of preschool7children’s apparel, including such entries as: Pink for girls; Tutu skirt; andso on, with three possible answers for respondents to choose from: I like; Idon’t like; Acceptable.

We based our questions on various statements we found such as “that’sexactly what we do [unlike others] / we never do that” in discussions onchildren’s clothing on web forums, blogs, and online social networks.8We also used the ethnographic method as observation, including partici-pant observation in St. Petersburg since we are both mothers of daughters.We kept careful field notes in a field diary that contains descriptions ofplaces, times, participants, situations, our impressions as observers, andour comments.

SOVIET TASTE, GIRLS’ INNOCENCE, AND CHILDREN’S FASHION IN CONTEMPORARY RUSSIAb

43

05-Boitsova:Layout 1 5/7/15 2:13 PM Page 43

Findings

We assumed that the boundaries of good taste of different groups wouldcross variants we included in the survey. Our hypothesis was that eachoffered variant would be approved of by one group and disapproved of byanother. We used factor analysis, which allows the reduction of plenty ofvariables to several units of the most strongly correlating variables. Theseunits can be considered as variables of higher order or as latent factors reflect-ing the structure of the field. In our case, factors with their componentsrelate to trends of children’s fashion which can be characterized as sets ofsympathies and antipathies to ways of dressing children. Variables of higherorder obtained as a result of factor analysis were used for further analysis. Inthis article we discuss two trends out of the ten that emerged as a result ofour processing answers by means of factor analysis. Two opposing factorsare connected to the representation of girls’ innocence.

Figure 1: Variables included in two factors, and their factor loading. The higher the factorloading, the more strongly the variable is connected to the factor. We included variableswith factor loadings higher than 0.3.

The first factor implies that the preschool girls are excluded from the rulesregulating the decent behavior expected of adult women. It unites the fol-

OLGA BOITSOVA AND ELENA MISHANOVA

44

a

05-Boitsova:Layout 1 5/7/15 2:13 PM Page 44

lowing variables: Child in a public place in tights and a shirt (with no skirt orpants on); Naked child on the beach; Girl on the beach in a swimsuit bottomwithout a swimsuit top; and Short dress without leggings. Almost all these vari-ants would be censured if practiced by a woman (see Ribeiro 2003). Welabeled this unit of four correlated variables the Short Dress Trend. The sec-ond factor included the variables Leggings or shorts put on under a dress orunder a skirt; and Shorts on leggings. Both display here an inverse correlationwith Short dress without leggings. This trend offers an additional layer of pro-tection in girls’ clothes, with leggings put on together with a skirt or a dressand not instead of these. We labeled this factor the Long Dress and Dresswith Leggings Trend.

The Short Dress TrendBesides fashion and before fashion, children’s attire follows its distinctivefunction: it has to differentiate children from grown-ups, boys from girls,babies from toddlers, preschoolers from schoolchildren, tweens from teen -agers. Thus, both the Short Dress Trend and the Long Dress and Dress withLeggings Trend, given that both include skirted garments (see Paoletti 2012),serve to tell girls from boys.

One of the social boundaries between children and adults, and betweenand among children of different ages is constructed with the help of theopposing notions of decent and indecent. The lives of newborn babies areregulated least of all by the rules of decency: they can appear nude, burp ordefecate in public, get their diapers changed in a public place, and all thisleads to amusement rather than shock. Preschoolers in contemporary Russiaare not expected to be nude in a public place other than the beach, but theyare not ashamed of accidentally displaying their underwear, and girls arecomfortable bathing in swimsuit bottoms without tops.

Our respondents, in commenting on their answers, indicated that thenecessity of covering a girl’s body depends on her age. Compare, for exam-ple, the remarks of respondents to the entry Girl on the beach in a swim bot-tom without a swim top:

up to 2–3 years I think it both possible and comfortable for the child and parentsand all others, older girls I believe need a top;up to 5-6 years;quite normal for preschool children;up to 8-9 years it is acceptable;up to 10 years, but in general I think, a one-piece swimsuit is better;before puberty quite acceptable.9

SOVIET TASTE, GIRLS’ INNOCENCE, AND CHILDREN’S FASHION IN CONTEMPORARY RUSSIAb

45

05-Boitsova:Layout 1 5/7/15 2:13 PM Page 45

Rules of decency also regulate communication between boys and girls.Apparel or behavior considered proper in front of peers of the same sex maynot be acceptable in mixed company. In the memoirs of a former Artek10

camper we read:At that time [1958] everyone [all boy and girl campers] in Artek except YoungPioneer leaders bathed in the sea and lay in the sun without panties or underpants.Girls were guided to the other side of the beach, but it was clearly seen that theywere naked, too.11

Naked child on the beach was a widespread practice in the USSR (Razogreeva2012). In Russian writer Aleksei Panteleev’s story for children “On the Sea”from Stories about Belochka and Tamarochka (1940) two girls of 5 or 6 yearsof age bathed naked in the sea. Obviously this did not shock anyone, andonly when they walked home naked through the streets did they gather sur-prised idlers and attract the attention of a policeman. This episode clearlyshows the shifting boundary between decent and indecent behavior accord-ing to place, time, and participants. Rules of decency are constructed todefine an individual’s position on the axes of age and gender, and children’swear contributes to this definition.

The length of the hemline in the twentieth century was a distinctiveattribute of age, too. It marked girls’ ageing: at the beginning of life thehem was as high as possible, becoming lower and lower as the girl got older.In America, hemlines dropped as a girl reached high school (see Cook2004). In the second half of the twentieth century in the USSR theyoungest preschool girls might have had dresses so short that they barelycovered their buttocks, older preschoolers had hems that came to the mid-dle of their thighs, schoolgirls’ hems reached their knees, and teenagers’were below the knee.

The dress grew longer in accord with the number of decency rules in agirl’s life. Preschoolers could expose body parts and underwear but for oldergirls it was a shame to show these. At the same time, the length of twenti-eth-century children’s dresses followed adult fashion trends. The hemlineof a little girl’s dress which, in the mid-nineteenth century, reached her knee,went upward in the twentieth century as did those of women’s dresses.Sometimes, girls’ hemlines even anticipated those of women’s dresses intheir upward movement. Dress length marked the age boundary betweengirls and women: given that the silhouette of girls’ dresses repeated that ofwomen’s, length became the only difference between them. According tofashion historian Alexander Vasilyev (2008), especially notable was theshortening of young girls’ dresses that occurred in the 1950s. The hemline

OLGA BOITSOVA AND ELENA MISHANOVA

46

a

05-Boitsova:Layout 1 5/7/15 2:13 PM Page 46

length had an explanation (believed to be objective) in the official Sovietdiscourse: “Proportions of child bodies are somewhat different from theseof adults. That is why long dresses and skirts don’t fit girls, and long pantsdon’t fit preschool boys” (Domovodstvo [Housekeeping] 1960: 278). OlgaPereladova, an author of advice literature, considered a child’s body “dis-

SOVIET TASTE, GIRLS’ INNOCENCE, AND CHILDREN’S FASHION IN CONTEMPORARY RUSSIAb

47

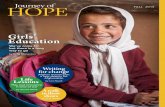

Figure 2: Children’s Dress, 1987. Short dresses on little girls and a knee-length dress on anolder girl whose hair bow emphasizes that she is also a child.

05-Boitsova:Layout 1 5/7/15 2:14 PM Page 47

proportionate,” and wrote that, in order to “make the figure more propor-tional … dresses, sundresses for girls, and pants for boys are made very short.It visually lengthens short legs” (1974: 50). The dresses of Kindergarten agegirls could occasionally show panties, underpants, a tight crotch or a stock-ings’ fastener. General acceptability of this practice is obvious from imagesof girls dressed like this that were published in books for children duringthe twentieth century.

As mentioned earlier, items of under-clothing that could be exposed toview accidentally by little girls, could not be displayed without shame byolder girls. Ekaterina Degot (n.d.), as part of the exhibition Pamiat tela.Nizhnee belye sovetskoy epokhi [Body memory: Underwear of the Soviet era]offers part of the memoirs of a Soviet girl:

I was six, my mom and I went to the store. And she put me in long, down to theknee reituzy (leggings) and quite a short dress. Well, okay. I had no idea that therewas something wrong. It was mom who put me in this outfit. On the way shestopped to chat with a friend. And her friend made a careless, arrogant remark tome: ‘Why, girl, your pants stick out!’ I suddenly burst into tears. It seemed such anoffence, a pain for me. And after that I never wanted to wear those leggings (n.p.).

Children themselves regulated their conduct in relation to age-appro-priate dress in teasing rhymes: “Kak tebe ne stydno, pantalony vidno” (Shameon you, pantalettes are seen) (Borisov 2012, s.v. “Kak tebe ne stydno”). Inthe first or second school year, boys and girls entertained themselves withthe game called “Moscow Umbrella” that involved lifting up girls’ skirts,and, also with peeping under girls’ skirts from the bottom of a staircase(Borisov 2000; Borisov 2012, s.v. “Damsky zontik”, “Zadirat yubku”,“Moskovsky zontik”, “Yubka”). One of the authors of this article recalls thatshe learned the meaning of the Russian verb sverkat (to shine) in the senseof “ to show underwear or buttocks from under a dress” from a classmate inthe first grade nearly 30 years ago. It would appear that in Kindergarten thefigurative meaning of the verb was as irrelevant as was any decency rule cor-responding to it. The Russian children’s writer, Sergei Ivanov, uses the sameverb in his story, Ischeznuvshie zerkala [Disappeared mirrors] (1990), justifiedhere by the comparison of Tanya’s panties to a balloon but this also invitesa slang reading. The heroine, Tanya, is nine or ten years old:

And she, maybe for luck, imagined ... thought ... recalled that climbing the stairs inshort dresses is not recommended for girls and that now her panties with their col-orful Cheburashka12 print shone like a balloon! And Tanya felt so ashamed… (165).

In the West, girls’ dresses along with corresponding decency rules,evolved in the twentieth century in much the same way as they did in the

OLGA BOITSOVA AND ELENA MISHANOVA

48

a

05-Boitsova:Layout 1 5/7/15 2:14 PM Page 48

USSR until the 1970s. In studying the visual discourse of the Western Ger-man Burda Moden magazine of the time, we discovered that in the mid-1970s little girls’ dresses became considerably longer coinciding with themaxi coming into adult fashion. Western sewing magazines of the 1970sfeature maxi dresses for young girls, too, and, since then, little girls’ hemlinesin such magazines have never risen above the knee. It is important to notethat we are not talking here about everyday practices which could varybecause of many factors, but, rather, about the visual expression of normativediscourse in sewing magazines like Burda Moden, and clothes catalogues.

In North American sewing and fashion visual discourse, the hemlineof young girls was still above the knee in the 1970s; small children’s dressesbecame knee-length and longer in the 1980s.13 At the same time, as ourresearch showed, in Soviet public visual discourse little girls’ dressesremained very short in the 1980s, although the maxi was in fashion amongSoviet women in the 1970s, too. Modesty, which fashion researcher DjurdjaBartlett (2010) considers an important part of what she calls socialist goodtaste, was clearly not applicable to children’s dress length at all. Illustrationsfrom Soviet sewing periodicals of the 1980s, which normalized the effectof the accidental display of underwear by very small girls (see Figure 2),were based on the fact that readers of the time perceived little girls in shortdresses to be properly clothed. Here, the important characteristic of thepictorial data mentioned above is evident: panties showing under a girl’sskirt could hardly be verbalized in advice literature but could be, and were,visually depicted.

However, recommendations on dressing children published in the peri-odical Doshkolnoe vositanie [Preschool education] in 1963 openly warnedagainst a “long, rumpled dress, from under which sportivnye sharovary (sportspants) peep out” (Vorobyeva and Samyshkina: 10, emphasis added). Theadvice was illustrated by a picture (see Figure 3) of one incorrectly dressedgirl—the first in the row—and three girls whose apparel is in order. Onecan see that the inappropriate garment is noticeably longer than the properones, and remarkably similar to the outfit which was considered suitable inour second trend, Long Dress and Dress with Leggings.

The Long Dress and Dress with Leggings Trend

As a result of Perestroika, those Soviet readers who had had little opportunityto obtain Western fashion newspapers, magazines, and catalogues fromabroad were now able to access these texts, including those on children’sfashion. Burda Moden was launched in Russian in 1987. Its illustrations of

SOVIET TASTE, GIRLS’ INNOCENCE, AND CHILDREN’S FASHION IN CONTEMPORARY RUSSIAb

49

05-Boitsova:Layout 1 5/7/15 2:14 PM Page 49

long dresses on little girls may have provoked the first reactions of aversionin some of the readers who were born and grew up in the USSR. One ofthe authors recalls the first time she saw pictures of little girls in dressesbelow the knee as she was turning the pages of a 1988 Burda Moden issue.It was a shock. They seemed so ugly to her.

As for bifurcated styles worn under dresses and skirts, this trend was re-introduced into Russia from the West around the mid-2000s. A double-page spread of the Russian Burda Moden issue of June 2005 features twosets of clothing for very small girls: “Sundress with bloomers” and “Sundresswith pants.” The bloomers and pants were justified in terms of the lengthof the top: “[h]aving mini length, it [the sundress] perfectly combines withwide bloomers” (120).

Leggings came into fashion for children at roughly the same time(Borisov 2012, s.v. “Legginsy”), following the vogue for adults that reviveda trend of the 1990s.14 While in 2001 the Russian website Intermoda warned,“And leggings, which are now on offer even for little girls, are rather harmfulfor a growing organism” (n.p.), in 2007 the website kindermoda.ru pub-lished two headings: “Leggings are a fashionable trend” and “Hit of the sea-son is leggings” (n.p.).

Our correlation analysis indicated significant correlation between thevariable Long Dress and Dress with Leggings, obtained through factor analysis,and respondents’ experience in Western countries: the more a respondenthad stayed in the US and/or Europe, the more he or she was likely to acceptthis trend. We also found correlation between Long Dress and Dress with Leg-gings and a variable reflecting the level of income: this trend characterizes

OLGA BOITSOVA AND ELENA MISHANOVA

50

a

Figure 3: Illustration in “Naryadnaya odezhda detei” [Elegant clothes for children]. Doshkol-noe vospitanie [Preschool Education], 1963.

05-Boitsova:Layout 1 5/7/15 2:14 PM Page 50

wealthy people. It is noteworthy that the variables Income level and Experi-ence in the West correlate with each other, so we may say that sympathies tothe variable Long Dress and Dress with Leggings characterize a group ofwealthy people who frequently visit Western countries or have lived in them.

Correlation analysis showed significant inverse correlation between thevariable Long Dress and Dress with Leggings and the respondents’ age: theolder a respondent, the less he or she is likely to accept long dresses and leg-gings on preschool girls. Our observations made in 2011 correspond to oursurvey findings. Thus, we observed a man, born in 1948, who, on seeinghis two-year-old granddaughter wearing a dress purchased in the USA,assumed that it was too big for her because it was so long even though thedress was exactly the right size for the girl. In another case, a woman, bornin 1946, when visited by a woman with her two-year-old daughter who waswearing a short tunic and pants, suggested that the mother take off the girl’spants, “because it is hot here.” So, we assume that a Soviet background liesbehind the disapproval of long dresses and leggings.

Discussion

Both the trends discovered and articulated in our research, in having some-thing to do with girls’ underwear and exposed body parts, pertain to theidea of girls’ innocence. Innocence has become part of the dominant viewof childhood, yet it is problematic. “Far from being inherent in any state ofnature or being inherent in children’s bodies, the innocence of childhoodwas a fashionable invention, formulated in art, refined in theory, and cos-tumed for the part” (Higonnet and Albinson 1997: 122). After the pioneer-ing work of Philippe Ariès (1962) child innocence can no longer be regardedas a universal constant, but, rather, as a social construct, supported by verbaland visual discourses of the epoch that proclaims it. For instance, in Francethe idea of childhood innocence won acceptance in the seventeenth century,its meaning changing through the ages since then from weakness to strengthand from imbecility to reason (Ariès 1962). The development of medicine,psychology, and law, contributes to the way in which innocence is under-stood (Jackson 2006). Among other ways, the concept of innocence is beingconveyed through the ways in which parents dress their daughters. As fash-ion researcher Annamari Vänska puts it, “[f ]ashion can be said to be one ofthe most contested fields of meaning production about children in contem-porary culture” (2011: 62).

SOVIET TASTE, GIRLS’ INNOCENCE, AND CHILDREN’S FASHION IN CONTEMPORARY RUSSIAb

51

05-Boitsova:Layout 1 5/7/15 2:14 PM Page 51

Karin Calvert (1992) connected the ways in which children’s clothes ofthe nineteenth century blurred sexual distinctions between boys and girlsto the concept of innocent nestling—the prevailing notion of childhood atthat time. Higonnet and Albinson (1997) refer to the images of children inwhite baby dresses in portraiture as “the Romantic Child” (122), the bodyimperceptible beneath clothing, with “adult erogenous zones” (123) con-cealed by apparel. This style of dressing children is hard to find nowadays,but innocence is still regarded as an integral part of childhood (see Cross2004), especially important for girls (Kaiser and Huun 2002).

A little contemporary Russian girl who wears just a short dress (firsttrend) or shorts under a skirt (second trend) rather than a long loose gar-ment can no longer be defined as Higonnet and Albinson’s “ideal disem-bodied child clothed in archaic innocence” (1997: 139). Her clothes donot make her an asexual being; she is wearing dresses and skirts which havebecome, as Paoletti (2012) points out, strictly gendered pieces of clothessince the first half of the twentieth century. However, for us, the way she isdressed accords with concepts of girlhood innocence translated into thelanguage of children’s fashion, although, of course, these concepts of inno-cence are different from that of the “Romantic Child” (Higonnet andAlbinson 1997: 122).

Clothes that reveal a girl’s body rather than concealing it convey animage of an innocent creature unaware of sin, one who does not know thatdisplaying body parts may be erotic or seductive. This kind of innocencepoints to sex in the sense that this is a girl; but it is not about sexuality. Usingthe words of Susan B. Kaiser and Kathleen Huun we suggest that this rep-resents “a continuing sexual innocence, despite some gendering” (2002:198). Little girls may appear naked or show their underwear, because theypresumably do not understand that a sexual meaning may be attributed tothis. The view of the innocent child as a naïve creature has been a popularconception since the seventeenth century. In the case of the USSR this wassupported by the ban in the 1930s on any discussion of sexuality in publicdiscourse until Perestroika (on this silencing see, for instance, Rotkirch2000). Some pedagogical ideas of the 1920s that proclaimed that YoungPioneers were supposed to know about the “harm of sexual intemperance”(Gusarova 2008: 76), would hardly have been supported by other Sovietpedagogy theorists such as Anton Makarenko, as cultural historian CatrionaKelly (2007) points out. In the 1930s these ideas conceded to the belief inthe innocence of Soviet children. “Sex education, then [in Makarenko’sview], was not only unnecessary but positively harmful: it was vulgar, it

OLGA BOITSOVA AND ELENA MISHANOVA

52

a

05-Boitsova:Layout 1 5/7/15 2:14 PM Page 52

excited curiosity, and provoked irresponsibility rather than sensible behavior”(576). This was, as Kelly goes on to make clear, in tune with the traditionalattitude held by the parents in Russian peasant and urban families from thenineteenth century up until the late twentieth that children should not beenlightened on the topic of sex. While the Soviet media explicitly warnedthe public about other potential threats to innocent childhood like alcoholand tobacco in caricatures (for instance, in 1979 by artist Evgeny Shcheglov)and these threats were privately mocked in amateur snapshots depicting littleones with cigarettes and alcohol bottles (Boitsova 2013), any mention ofsexuality was totally absent from the world built by grown-ups in the USSRfor children, public or private, until the 1980s.

Knowledge about sex was regarded as a cause of dangerous precocityand premature sexual activity. (In contemporary neoconservative Russiandiscourse this is again the case.) Innocence was synonymous with ignorance.While she was growing up, a girl’s process of learning the rules of decencyinvolved sudden bouts of shame as when she first met these rules in teasingrhymes, or embarrassing games, or mocking remarks. Not surprisingly, textssuch as memoirs, fiction, or children’s folklore, in touching upon the occa-sional display of underwear by girls, contain the recurring motif of styd andstydno (shame and feeling ashamed). Adults who dress girls according to thefirst trend, Short Dress, keep them in this ignorance-as-innocence state inten-tionally. To dress a girl so that she does not transgress the rules of adultdecency would mean introducing her to the world of sexual knowledge andthis is why the second trend, Long Dress and Dress with Leggings is disap-proved of by the older generation bred in the USSR. No wonder the conceptof modesty, important for socialist good taste, was not applicable here; forlittle girls it would have meant awareness. In this context a girl is not beingprotected from prurient eyes by a shield of clothes; she is being protectedfrom information that would urge her to adulthood.

However, the second trend we found in Russian children’s fashion can-not be termed a sexualizing one either. The contemporary fashion systemdoes not ascribe the signified sexual to leggings worn under a dress or shortsworn under a skirt, though occasionally leggings or shorts may acquire thismeaning because of their own features, such as a close fit or leopard print.Also, adult Russian women do not usually wear shorts under skirts anyway.The trend in question may be called protective; it protects a girl’s innocencefrom anyone who would launch an attack on it. In contemporary discoursethis refers to the behaviors of pedophiles. The last decades of the twentiethcentury saw a rethinking of the topic of pedophilia and this resulted, in the

SOVIET TASTE, GIRLS’ INNOCENCE, AND CHILDREN’S FASHION IN CONTEMPORARY RUSSIAb

53

05-Boitsova:Layout 1 5/7/15 2:14 PM Page 53

1980s, in an upsurge of concern about the need to protect children againstsexual crimes (Holland 2004).

The first trend seems to leave a girl unprotected since her ignorance isitself considered a shield against the dangerous adult world. Since oneknows that girls are susceptible to sexual danger, their ignorance can nolonger be regarded as a shield, and girls whose bodies are most open to viewbecome most vulnerable. “From flirting bimbos to pouting babies, we havebeen trained by the imagery itself to read pictures of girls in an erotic way”(Holland 2004: 188). This training cannot be rejected, as the comment ofone of our respondents makes clear: “If a girl wears tights under a shortdress, it’s acceptable, but if only panties, in our realities of razgul (thedebauchery) of pedophilia such a demonstration is absolutely out of place!”A little girl is armed, so to speak, with leggings against more experiencedpeers, who understand the sexual meaning of nudity and underwear, as wellas against adults who might attempt to harm her. Innocence here is con-ceived of as not being capable of seducing anyone, even by chance. It doesnot mean unawareness of sin, but, rather, precautions taken against sin. Along dress itself is not enough since the little girl dressed in it may still breakthe rules of adult decency through ignorance when she crawls, somersaults,or hangs on monkey bars. This is why she needs the additional layer of pro-tection afforded by shorts or leggings in case that first layer of dress shouldbe inadequate.

While the first conception of innocence as ignorance clearly distin-guishes children from grown-ups in terms of the formers’ unawareness, thesecond, in refusing to see girls as ignorant, separates them from women bymeans of a special protective layer of clothing not typically worn by adults.However, the similarity of children to adults in this case is emphasized byanother trend that was revealed by our factor analysis. It combines leggingsunder a dress with colors that are more typical of adult clothing than thatof girls: variables Dark colors (brown, black) for girls and Blue for girls are sig-nificant here as well as Leggings or shorts put on under a dress or under a skirt.The sex-age division, rejected here, that declares that pink is for girls andblue is for boys, in fact serves the purpose of telling children from adults,too. Among adults, blue is not reserved for men’s clothes; it is a gender neu-tral color. Pink indeed is reputedly feminine (though in the public view thereis the suggestion of naivety in a woman wearing it), but it is worth notingthat in about 2004, men’s pink shirts came into fashion (Paoletti 2012). So,our analysis indicates that the girls being offered informed protection frompeeping eyes are also being allowed to abandon the age-sex division in their

OLGA BOITSOVA AND ELENA MISHANOVA

54

a

05-Boitsova:Layout 1 5/7/15 2:14 PM Page 54

dress to some extent. They are moved closer to being adult through clothes,although an additional layer of defense is believed necessary for them becauseof their age.

These two trends in dressing children, as well as the concepts behindthem, oppose each other. Paradoxically, they both may be regarded by theiropponents as sexualizing girls. A comment on the entry Leggings or shortsput on under a dress or under a skirt from a supporter of the first trend reads:“In Moulin Rouge they dress more decently [than this]” and a commentfrom a supporter of the second trend reads: “And only panties under a shortskirt, it’s pornography.”

In public discourse, neither of these two trends is considered to be sex-ualizing children —in fact, neither of them appears visible to the media.Another trend is criticized nowadays for the premature sexualization ofgirls: “sexy, trendy styles for very little girls” such as “skinny jeans in infantsizes” (Paoletti 2012: 134) or bras and strings (Rysst 2008). Our analysisrevealed this trend in contemporary Russia, too. One of eight other trendsuncovered by our factor analysis describes a girl who follows grown-upvogue: besides a tutu skirt, she wears jewelry, leopard print, adult pieces ofclothing, such as jackets, and she or her parents dare to combine differentcolors in her apparel. Wearing leopard print in the adult fashion systemmay indicate a reference to sexuality. Its combination with jewelry andpieces of clothing more appropriate to adults can be considered as famil-iarizing girls with adult fashion that sexualizes women. The comment ofone of our respondents is interesting in this context: “But because of theincreased number of pedophiles, I think that children’s clothes should bejuvenile, reasonably open and should not imitate the sexual dresses of vampwomen, in order not to provoke people with a corrupted mentality to com-mit crimes against children.” This respondent assessed girls on the beachwearing only a swimsuit bottom, and short dresses without leggings asacceptable, approved of leggings under a dress, and disapproved of animalprint on children.

Conclusion

There is no such thing as a set of objective decency rules nor is there a rightage, objectively, to observe them. The two conceptions of girlhood inno-cence discussed here are both constructed through clothing, which thusbecome a visual utterance on childhood: as Kaiser and Huun put it, “[C]ulture

SOVIET TASTE, GIRLS’ INNOCENCE, AND CHILDREN’S FASHION IN CONTEMPORARY RUSSIAb

55

05-Boitsova:Layout 1 5/7/15 2:14 PM Page 55

seems to entrust clothing with messages it cannot otherwise articulate”(2002: 184).

The first trend, Short Dress, conveys a message about an innocent girlunaware of sexuality, separated from the adult world and left to learn therules of decency without aid from adults. As we have shown, it characterizesthe taste of those who were socialized in the USSR so can therefore be calledSoviet taste. The terms Soviet taste and socialist good taste are applied byresearchers to what was perceived to be the aim of educational efforts of offi-cial discourse, with no reference to its reception or real practice (see Gurova2008; Bartlett 2010). Here, we use the term Soviet taste to describe the pref-erences of people bred in the USSR, to which they adhere, and display evenin the post-Soviet period, when Soviet propaganda can no longer reachthem. Our project has shown that thus defined Soviet taste may be discov-ered, too, at least with regard to the question of which dress length is properfor little girls and which length is ugly. We hope that this approach to Soviettaste may be further developed in the future in order to complement Sovietdiscourse studies by adding the perspective of reception.

The second trend, Long Dress and Dress with Leggings, conveys a mes-sage about girls not that far separated from adults but vulnerable to sexualdanger and protected by responsible adults. This, as is shown by our analy-sis, characterizes contemporary consumers with a high income, influencedby Western vogue. Fashion discourse in the West nowadays is not mono-lithic: it offers such garments as bikinis for the smallest girls on the onehand and blames fashion for sexualizing children on the other (see Rysst2008). However, considering the exposure of body parts as being properfor little girls is a special feature of Soviet taste not found in the West nowa-days. We think that its denial in contemporary Russia and the trend ofcovering little girls’ bodies is motivated, along with the pedophilia alertand other anxieties surrounding innocence, by the ideological backgroundof desovietization.

OLGA BOITSOVA is a researcher at the Kunstkamera, also known as Peterthe Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography, St. Petersburg, Rus-sia, and the author of a book on Russian amateur photography. Herresearch interests include, besides children’s fashion, visual studies andsemiotics. She has taught courses on Visual Analysis in Social Sciences andPictorial Semiotics.

OLGA BOITSOVA AND ELENA MISHANOVA

56

a

a

05-Boitsova:Layout 1 5/7/15 2:14 PM Page 56

ELENA MISHANOVA is an independent researcher. She graduated from theEuropean University at St. Petersburg in the Department of Political Sci-ence and Sociology and is interested in the study of political ideologies.Her interests also include quantitative research methods in social sciences,and statistics.

Notes

1. http://forum.littleone.ru/2. http://www.u-mama.ru/forum/3. http://volgo-mama.ru/4. http://sibmama.ru/5. http://my-i-deti.livejournal.com/ which does not limit its audience to any particular

city although most of its users come from Moscow.6. Data from spring 2012 indicates that Russian Internet users make up about half the

population of Russia and 57 to 70 percent of residents of Moscow, St. Petersburg andother megacities. http://runet.fom.ru/Proniknovenie-interneta/11567 (accessed 26 Sep-tember 2014).

7. Children start school at the age of six or seven in contemporary Russia.8. For instance, we took account of the following discussions held in 2011 in Russian

Livejournal communities: <http://malyshi.livejournal.com/31737831.html> on girlsin dresses on children’s playgrounds, <http://ru-gymboree.livejournal.com/682486.html> on black for girls, <http://malyshi.livejournal.com/31212842.html> on childrenin public places in tights and shirts but not wearing skirts or pants (all accessed 22 June2014).

9. All translations into English from Russian are our own.10. Artek was an international Young Pioneer camp on the Black Sea.11. Artekovets (Artek camper): http://artekovetc.ru/01958jk.html (accessed 13 July 2014).12. Cheburashka is a popular Soviet cartoon character, a funny little creature.13. See, for instance, what was known as the tea-length dress in Simplicity Patterns no.

9070.14. In periodicals of the 1990s children as well as adults sported leggings: Burda Moden

no. 2, 1992, and no. 7, 1994, feature leggings for school- and even preschool girls.Memoirs reflect that they were worn by girls of primary school (Borisov 2012, s.v.“Velosipedki”, “Losiny”).

References

Ariès, Philippe. [1960] 1962. Centuries of Childhood: A Social History of FamilyLife. New York: Alfred A. Kopf.

Bartlett, Djurdja. 2010. FashionEast: The Spectre that Haunted Socialism.Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

SOVIET TASTE, GIRLS’ INNOCENCE, AND CHILDREN’S FASHION IN CONTEMPORARY RUSSIAb

57

b

05-Boitsova:Layout 1 5/7/15 2:14 PM Page 57

Borisov, Sergei. 2000. Kulturantropologia devichestva. Shadrinsk: Shadrinsk StatePedagogical Institute.

Borisov, Sergei. 2012. Russkoe detstvo XIX-XX vv. Kulturno-antropologicheskyslovar. 2 vols. St. Petersburg: Dmitry Bulanin.

Boitsova, Olga. 2013. Lubitelskie foto: vizualnaya kultura povsednevnosti. St.Petersburg: EUSPb.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1984. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste.Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Calvert, Karin. 1992. Children in the House: The Material Culture of EarlyChildhood, 1600–1900. Boston: Northeastern University Press.

Cross, Gary. 2004. The Cute and the Cool: Wondrous Innocence and ModernAmerican Children’s Culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cook, Daniel Thomas. 2004. The Commodification of Childhood: The Children’sClothing Industry and the Rise of the Child Consumer. Durham, NC: DukeUniversity Press.

Degot, Ekaterina. “Pamiat tela. Literaturny proekt dlia vystavki ‘Pamiat tela.Nizhnee belye sovetskoy epokhi” [Body memory. Literary project for theexhibition ‘Body memory. Underwear of the Soviet era.] http://www.guelman.ru/slava/degot/ (accessed 19 January 2014).

Domovodstvo [Housekeeping]. 1960. Moscow: Gosudarstvennoye izdatelstvoselskokhozyaystvennoy literatury.

Gronow, Jukka. 1997. The Sociology of Taste. London and New York: Routledge.Gusarova, Ksenia. 2008. “Khvorost v koster mirovoy revoltsii: pionery.”Neprikosnovenny Zapas, no. 2 (58): 69–84.

Gurova, Olga. 2008. Sovetskoye nizhnee belie: mezhdu ideologiey i povsednevnostiu.Moscow: NLO.

Higonnet, Anne, and Cassi Albinson. 1997. “Clothing the Child’s Body.” FashionTheory: The Journal of Dress, Body & Culture 1, no. 2: 119–143.

Holland, Patricia. 2004. Picturing Childhood: The Myth of the Child in PopularImagery. London: I.B. Tauris.

Ivanov, Sergei. 1990. Ischeznvshie zerkala [Disappeared mirrors]. Moscow:Detskaya Literatura.

Jackson, Louise. 2006. “Childhood and Youth.” Pp. 231–255 in PalgraveAdvances in the Modern History of Sexuality, ed. Hera G. Cock and MattHoulbrook. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kaiser, Susan B., and Kathleen Huun. 2002. “Fashioning Innocence and Anxiety:Clothing, Gender, and Symbolic Childhood.” Pp. 183–208 in SymbolicChildhood, ed. Daniel Thomas Cook. New York: Peter Lang.

Kelly, Catriona. 2007. Children’s World: Growing Up in Russia, 1890–1991. NewHaven and London: Yale University Press.

OLGA BOITSOVA AND ELENA MISHANOVA

58

a

05-Boitsova:Layout 1 5/7/15 2:14 PM Page 58

Kivelson, Valerie A., and Joan Neuberger. 2008. “Seeing into Being: AnIntroduction.” Pp. 1–11 in Picturing Russia, ed. Valerie A. Kivelson and JoanNeuberger. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Paoletti, Jo. 2012. Pink and Blue: Telling the Boys from the Girls in America.Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Pereladova, Olga. Detskaya odezhda. Kiev: Zdorovya, 1974.Razogreeva, Anna. 2012. “Nudisty, deti I golye khuligany: teo kak lokus

obshchestvennogo poriadka v pozdnesovetskikh obstoyatelstvakh.” Teoriamody. Odezhda, telo, kultura, no. 24. http://www.nlobooks.ru/node/2199(accessed 20 January 2014).

Ribeiro, Aileen. 2003. Dress and Morality. Oxford: Berg.Rotkirch, Anna. 2000. “The Man Question: Loves and Lives in Late 20th

Century Russia”. University of Helsinki Department of Social Policy,Research Reports 1/2000. https://helda.helsinki.fi/handle/10138/26431(accessed 14 February 2014).

Rysst, Mari. 2008. “Dialektika eroticheskogo i tselomudrennogo v modelirovaniiodezhdy dlia mladshyh shkolnits.” Teoria mody. Odezhda, telo, kultura, no. 8:239–258.

Shcheglov, Evgeny. 1979. Ostorozhno, deti! Moscow: Sovetsky khudozhnik.Vänskä, Annamari. 2011. “Guiding Mothers: On Sexualization of Children in

Vogue Bambini.” Pp. 59–79 in Nordic Fashion Studies, ed. Louise Wallenbergand Peter McNeil. Stockholm: Axl Books.

Vasilyev, Alexander. 2008. Russkaya moda. 150 let v fotorafiyakh. Moscow: Slovo.Vorobyeva, E., and I. Samyshkina. “Naryadnaya odezhda detei” [Stylish

children’s clothes]. 1963. Doshkolnoe vospitanie, no. 9: 10–12.

SOVIET TASTE, GIRLS’ INNOCENCE, AND CHILDREN’S FASHION IN CONTEMPORARY RUSSIAb

59

05-Boitsova:Layout 1 5/7/15 2:14 PM Page 59