A PARADOX? HOMOGENEITY IN THE IMP PERSPECTIVE

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

4 -

download

0

Transcript of A PARADOX? HOMOGENEITY IN THE IMP PERSPECTIVE

A Paradox? Homogeneity in the IMP Perspective

Competitive Paper Submitted for the 19th Annual IMP Conference

University of Lugano 4th − 6th September 2003

Lugano, Switzerland

A PARADOX? HOMOGENEITY IN THE IMP PERSPECTIVE

ELSEBETH HOLMEN* Norwegian University of Science and Technology

Department of Industrial Economics and Technology Management N-7491 Trondheim, Norway

Phone: +47 73 59 04 64, Fax: +47 73 59 35 65 E-mail: [email protected]

MAGNAR FORBORD

Centre for Rural Research Norwegian University of Science and Technology,

N-7491 Trondheim, Norway Phone: +47 73 59 17 36, Fax: +47 73 59 12 75

E-mail: [email protected]

ESPEN GRESSETVOLD Trondheim Business School N-7004 Trondheim, Norway

Phone: +47 95 87 29 69, Fax +47 73 55 99 51 E-mail: [email protected]

ANN-CHARLOTT PEDERSEN

Norwegian University of Science and Technology Department of Industrial Economics and Technology Management

N-7491 Trondheim, Norway Phone: +47 73 59 35 03, Fax: +47 73 59 35 65

E-mail: [email protected]

TIM TORVATN Norwegian University of Science and Technology

Department of Industrial Economics and Technology Management N-7491 Trondheim, Norway

Phone: +47 73 59 34 93, Fax: +47 73 59 35 65 E-mail: [email protected]

* Corresponding author

A Paradox? Homogeneity in the IMP Perspective

Abstract

In this paper we discuss the assumption of heterogeneity within the IMP Perspective. We

claim that the assumption of heterogeneity in the IMP Perspective actually comprises two

assumptions: (A) that the value of a single resource depends on the combination in which it is

used, and (B) that a single resource is always unique in the sense that it always differs from

other resources. Furthermore, and on the basis of the main sources of the concept of

heterogeneity, we claim that even if we assume that any resource is always heterogeneous, in

both the (A) and the (B) sense, it is important to realise that the heterogeneity is neither

always considered nor always made use of. In other words, we suggest that it is important to

also consider ‘that’, ‘how’ and ‘why’ resource heterogeneity is disregarded. That is, we need

to consider that actors choose between heterogeneity-exploring and homogeneity-creating

action strategies. We discuss and exemplify how heterogeneity of both type (A) and (B) can

be (1) disregarded or (2) made use of. In doing so we make use of the framework by

Håkansson and Waluszewski (2002) who propose that it is useful to analyse networks in

terms of four types of resources: products, facilities, business units and relationships. We

propose that all four resource entities are heterogeneous in the (A) as well as the (B) sense,

and that for each type of resource entity, both types of heterogeneity can be either (1)

disregarded or (2) made use of. Throughout the paper, we make use of a case study for

exemplifying the different conceptual types, we put forward, and the observation that these

conceptual types are always mixed when action is taken in real, empirical settings. Thereby,

we suggest (a) that managers always use only a fraction of and disregard most of both types of

heterogeneity of those resources which they use and consider for creating efficiency and

effectiveness in networks, and (b) that we need more research into how and why managers do

so. Finally, we suggest that the concept of homogeneity as ‘disregarded heterogeneity’, in

effect, is necessary for explaining the possibility of development as well as the existence of

relationships.

Keywords: IMP Perspective; resources; heterogeneity; homogeneity; bounded rationality

2/20

A Paradox? Homogeneity in the IMP Perspective

Introduction

The assumption of resource heterogeneity is one of the main pillars on which the IMP

Perspective rests. Even so, mention is most often only made of the ‘underlying assumption’ of

(resource) heterogeneity – the content of the assumption is seldom discussed per se, and even

more seldom are explicit discussions of implications of the assumption (i.e. consequences of

the concept for analysis, agency, and organisational structures and processes). On these

grounds the purpose of the paper is to discuss and question if sole attention should be paid to

resource heterogeneity in the IMP Perspective, or if (and why) its ‘opposite number’ resource

homogeneity should also be considered within the perspective. The paper is organised the

following way: First, we introduce a case – on development and supplier selection – which

will be used throughout the paper to exemplify the concepts and logic we propose. Secondly,

we address the assumption of resource heterogeneity and claim that there are two types (A)

and (B). We look into the main sources of the concepts – Penrose (1959) and Alchian and

Demsetz (1992) – and discuss how and why these authors discussed heterogeneity in relation

to homogeneity as ‘disregarded heterogeneity’. In doing so, we also touch upon the

assumption of bounded cognition/rationality. We then scrutinise some of the few

contributions which have considered ‘disregarding heterogeneity’ within the IMP Perspective

and we suggest that heterogeneity (of both type (A) and type (B)) can be either used or

disregarded. We then relate these propositions to the 4 resource entity model proposed by

Håkansson and Waluszewski (2002). Furthermore, we illustrate the use of the resulting

concepts by analysing the case study. The paper ends with implications for the IMP

Perspective and further research.

Case Study - Provision and Sourcing of an ASIC

In order to explicate the theoretical concepts and logic we discuss in this paper, we make use

of one case throughout the paper. The case presented here is but a minor part of a large case

study made in connection with the thesis by Gressetvold (2003). For further details and

methodology, the reader may consult this thesis.

The company Nordic VLSI has developed the design for close to 200 different ASICs to be

used by a wide range of business customers. ASIC is an acronym for Application Specific

3/20

A Paradox? Homogeneity in the IMP Perspective

Integrated Circuit and refers to a data chip that is developed for specific application by a user.

Nordic VLSI develops the majority of these ASICs upon request from single customers.

These customers in their turn make use of the ASIC as part of their products. One of the

customers, VingCard, is a world-leading manufacturer of card operated locking-systems for

the hotel and cruise industries. The company became a customer of Nordic VLSI after that it

(VingCard) made a change from producing mechanical to producing electronic locking-

systems. Hence, VingCard’s latest solution for locking-systems makes use of an ASIC. While

Nordic VLSI developed the ASIC for VingCard, VingCard itself developed all adjacent

technologies, among other things the software and other hardware parts of the locking-system.

In addition to designing the ASIC, Nordic VLSI was also responsible for manufacturing of the

ASIC and made use of Alcatel Microelectronics as the fab. Every fab offers a limited number

of manufacturing processes to its customers, and the costs of developing new manufacturing

processes are high. The different fabs to a large extent carry out manufacturing processes

based on ‘internal’ standards, communicated to others by means of a so-called ‘blue book’.

Through this ‘blue book,’ Nordic VLSI took Alcatel Microelectronics’ manufacturing process

into consideration from the initiation of the development of the ASIC for VingCard.

At first, Nordic VLSI’s handling of component supplies consisted of co-ordinating the

physical shipments of the ASIC from Alcatel Microelectronics to Kitron, the supplier of the

control module of VingCard’s locking-system of which the ASIC was a part. However, when

VingCard started up actual manufacturing of electronic locking-systems, it also decided to

implement a logistics system based on JIT-principles. This system was intended to embrace

all components that entered into VingCard’s products. One new policy element in the system

was a principle of dual sourcing for all vital components. VingCard’s intention with this

principle was to bring stability into its supply chains and to reduce costs. As the control

modules represented a considerable cost of the purchased components, VingCard wanted it to

be handled according to the new principle of dual sourcing. In addition to Kitron, Lyng was

therefore introduced as a second supplier of the control modules. As the ASIC had to be

assembled into this control module, ASICs now had to be supplied directly to two companies.

VingCard also desired to organise the manufacturing of the ASIC according to the new

logistical principle, but experienced several difficulties with this. Firstly, Nordic VLSI,

through handling the component supplies, possessed the property rights to the ASIC; this was

settled in the contractual arrangement between the two companies. Secondly, this ASIC was

adapted to Alcatel Microelectronics’ manufacturing process in accordance with this

4/20

A Paradox? Homogeneity in the IMP Perspective

company’s aforementioned ‘blue book.’ This meant that the ASIC, due to technical reasons,

could not be manufactured by other fabs. Such difficulties concerning dual sourcing of ASICs

are well-known by companies that develop and use this kind of product. VingCard, on the

other hand, being a first-time user, was initially not aware of such difficulties but experienced

that it was not able to implement its new logistics system unrestrictedly, as the company had

no other sources for purchasing the ASIC than Nordic VLSI.

Sources of the Assumption of Heterogeneity within the IMP Perspective

In the IMP Perspective it seems as if heterogeneity is mainly used in order to draw attention to

the assumption that the value of a resource depends on the combination in which it is used.

Thereby is meant that a single element may appear different, and hence be of different value,

if seen in different combinations. We shall refer to this as heterogeneity assumption (A).

Relating this assumption to our case, we can think of any given ASIC as such an element.

Used in combination with the other resources for which it has been designed, the ASIC has a

high value, but used in other combinations its value is greatly reduced; perhaps even to zero.

However, relying on Holmen and Pedersen (1999) and Holmen (2001) we suggest that the

concept of heterogeneity actually is defined in two ways in the IMP Perspective. In addition

to type (A) there is a type (B). Type (B) implies that resources (within a group) are different.

This definition of resource heterogeneity is close to the definition used in the Resource Based

View where ‘heterogeneous resources’ = ‘different resources’. Using our case, we can say

that the fact that each ASIC is specially designed for one particular application by one certain

customer’s means that the ASICs produced by Nordic VLSI constitute a group of resources in

which each element is different from the other, thus representing heterogeneity of type B.

Within the IMP Perspective, it is primarily heterogeneity of type (A) that has been paid

attention to. When this assumption of heterogeneity is proposed, mentioned or explained,

reference is often made to the respective work by Penrose (1959) and Alchian and Demsetz

(1972).

Heterogeneity - according to Penrose (1959)

As opposed to (macro)economists who had focused on markets, factors, and (firms-as-)

production functions for explaining how the economy works, Penrose (1959) put forward the

5/20

A Paradox? Homogeneity in the IMP Perspective

central notion of ‘resources’ for understanding how ‘real’ firms and managers behave. The

distinguishing feature of Penrose’s resources is that they are heterogeneous in the sense that

there are always unexplored features of a resource and, therefore, infinite possibilities for

exploring it further. Resource heterogeneity was the core assumption of her ‘theory of the

growth of the firm’ – that is, a firm grows and develops in a subset of the directions which its

existing pool of heterogeneous resources enables. Firm growth = f(resource heterogeneity).

However, Penrose (1959) did not only discuss heterogeneity – she also discussed its opposite

number: homogeneity. As she states (1959, p.74-75) “For many purposes it is possible to

deal with rather broad categories of resources, overlooking the lack of homogeneity in the

members of the category. [..] the sub-division of resources (into smaller categories) may

proceed as far as it is useful, and according to whatever principles are most applicable for

the problem at hand. The subdivision cannot go so far that each input is defined as a separate

resource, however. The only purpose of devising a ‘unit’ of resources or services is to enable

us to measure the number of units within a given category. If this number is always one, no

purpose is served by the classification. There are many resources of which each unit is so

much like every other unit that a homogeneous category can be established which includes a

large number of units. [..] The chief problem is to obtain a classification related to the nature

of the resource within which the required degree of homogeneity exists.” Hence, while

Penrose (1959) stress the importance of considering resources as heterogeneous, she also

points out that assuming (or focusing on) heterogeneity is not always useful. In other words

she seems to imply that even if all resources are (possible to consider as being) heterogeneous

it may, on some occasions, be more useful to disregard the heterogeneity and instead focus on

homogeneity.

Heterogeneity – according to Alchian and Demsetz (1972)

Whereas Penrose (1959) is interested in explaining how firms grow, Alchian and Demsetz

(1972) are interested in explaining the boundary of firms and the function of managers.

Similarly to Penrose, Alchian and Demsetz (1972) assume that resources are heterogeneous –

in the sense that a single resource can be used for many different purposes or combinations

and that value of the resource may differ across combinations. With the assumption of

heterogeneity, they propose that the boundary of a firm demarcates the area in which

resources are regarded as heterogeneous (within the firm boundary) from the area in which

resources are regarded as homogeneous (beyond the boundary of the firm, in markets). Firm

boundary = f(resource heterogeneity). Thereby, they propose that an important function of

6/20

A Paradox? Homogeneity in the IMP Perspective

managers is that they can intimately observe how resources (mainly employees) can be used

and perform in different combinations over time which, in turn, endows managers with

superior opportunities for using and valuating the internal resources. Management function =

f(human resource heterogeneity). This, in fact, means that Alchian and Demsetz (1972)

implicitly recognise both the existence of heterogeneity and the possibility of ignoring it. In

other words, they seem to equate homogeneity with ‘disregarded heterogeneity’ (outside the

firm, in markets). Furthermore, the fact that they explain the boundaries of firms in this

manner implies that they recognise the benefits of disregarding some part of the heterogeneity

which they assume to exist – if there were no such benefits, there would be one firm only.

Using Hayek (1952) for Understanding Penrose (1959) and Alchian and Demsetz (1972)

In order to understand the duality between heterogeneity and homogeneity which both

Penrose (1959) and Alchian and Demsetz (1972) seem to subscribe to, we may rely on Hayek

(1952) and his contribution to theoretical psychology. Hayek (1952) discusses sensory

perception – how we experience the world. In the introduction to his thesis, it is stated (1952,

p.xviii) that “sensory perception must be regarded as an act of classification. What we

perceive are never unique properties of individual objects, but always only properties which

the objects have in common with other objects. Perception is thus always an interpretation,

the placing of something into one or several classes of objects.”

Hayek (1952) seems to come to this conclusion by a number of assumptions. He assumes that

“there exists [..] no one-to-one correspondence between the kinds (or the physical properties)

of the different physical stimuli and the dimensions in which they can vary, on the one hand,

and the different kinds of sensory qualities which they produce and their various dimensions,

on the other” (Hayek, 1952, p.14). This leads him to conclude that “the physical order differs

from the phenomenal order.[..] While they are in some measure similar, and while we owe it

to this similarity that we can find our way about in the physical world, they are, as we have

seen, far from being identical” (Hayek, 1952, p.38). One implication of this is that so long as

physically different elements, whatever other properties they may possess, are capable of

acting in the same way, their other properties are irrelevant for our understanding of them as

members of the same category (Hayek, 1952, p.46). On the basis of this, Hayek defines

classification as “a process in which on each occasion on which a certain recurring event

7/20

A Paradox? Homogeneity in the IMP Perspective

happens it produces the same specific effect, and where the effects produced by any one kind

of such events may be either the same or different from those which any other kind of event

produces in a similar manner. All the different events which whenever they occur produce the

same effect will be said to be events of the same class, and the fact that every one of them

produces the same effect will be the sole criterion which makes them members of the same

class” (Hayek, 1952, p.48). Hence, Hayek (1952) seems to assume that heterogeneity is

something which ‘exists’ in a ‘physical’ sense, but that individuals (choose to) place elements

into classes within which there is some degree of homogeneity and among which there is

some degree of heterogeneity. Furthermore, Hayek (1952) seems to imply that some disregard

of heterogeneity – via a process of ‘homogenisation’ – is necessary in order for individuals

(and firms) to be able to deal with the world.

Bounded Rationality/Cognition

Basically, Hayek (1952) points out that people tend to see ‘reality’ not as it ‘is’, but as they

frame and classify it, and that even if they have quite some latitude in choosing the

classifications, these must be partially compatible with the ‘reality’ they represent (if not, they

may need revision). Quite comparable issues have been addressed by other researchers within

various streams of theorising. For example, within the field of language and cognition, Eco

(2000) discusses categorisation, cognitive types and nuclear content of elements and stresses

the possibilities for assigning a single element to different types of categories – ‘is Ayers

Rock a stone or a mountain, or?’ Within economics, researchers addressing framing and

cognition often do so with the concept of ‘bounded rationality’ (or ‘bounded cognition’).

Bounded rationality dates back to Simon (see e.g. Simon (1997)) who criticised orthodox

economic theory for its inability to conceptualise and explain administrative behaviour. Since

then, the concept has been taken up by a large number of researchers within many

(sub)streams of theorising. Bounded rationality/cognition can be defined as “an imperfect

ability to perceive, learn about, compare, remember, and order alternatives” (cf. Witt, 1996).

However, different researchers define and use bounded rationality/cognition in quite different

ways. As noted by Foss (2001), there are ‘richer or poorer notions’ of bounded

rationality/cognition. Whereas poorer notions mainly evoke bounded rationality/cognition as a

kind of ‘background assumption’, ‘richer notions’ takes into account “the wider consequences

of imperfect information processing in terms of the strategies or rules that agents may follow

8/20

A Paradox? Homogeneity in the IMP Perspective

to cope with their imperfect computational abilities, the cognitive frames for representing

reality they construct, and the cognitive biases and errors they suffer from” (Foss, 2001,

p.411). In short, researchers focusing on (individuals’) decision making tend to use and

discuss bounded rationality/cognition in more detail. Instead of explaining general regularities

(such as the boundary of the firm), they try to “explore mechanisms, that is, causal

connections that may or may not be triggered in specific situations [..for example..] how a

specific manifestation of bounded rationality – such as, say, reference level biases – translate

into transaction costs confronted by agents in a specific model setting, and how this

influences the contract or governance structure chosen by these agents to regulate their

trade” (Foss, 2001, p.412). In short, such researchers focus on finding generalisable

knowledge regarding agents’ strategies for dealing with ‘reality’ given their bounded

rationality/cognition. Among such researchers we find, for example, Loasby (1976) and

(1999) who proposes that bounded cognition is the reason why no individual (or firm) can

deal with (even a subset of) the complex world in its heterogeneous ‘totality’.

Heterogeneity, Homogeneity, and Bounded Rationality – in the IMP Perspective

The concept of heterogeneity (type (A)) is mentioned in the majority of publications based on

the IMP Perspective – primarily for explaining why development is more important to

consider than static situations. Development = f(heterogeneity). The concept of heterogeneity

(type (B)) is primarily used for explaining the need for unique relationships since no

counterparts are identical. Relationships = f(heterogeneity).

As mentioned earlier, Penrose (1959) and Alchian and Demsetz (1972) are important sources

of the concept of heterogeneity within the IMP Perspective. However, both sources discuss

heterogeneity and homogeneity. Furthermore, they seem to have heterogeneity as the basic

point of departure but to also consider the possibility of disregarding it even if aware of it – or

not being aware of it at all. In order to understand the duality between heterogeneity and

homogeneity, we inquired into the lines of reasoning proposed by Hayek (1952), Simon

(1997), Loasby (1976) and (1999) and Foss (2001). We then encountered the assumption of

bounded rationality/cognition, which seems to be related, in some way or another, to the

duality between heterogeneity and homogeneity. Therefore, we shall now address how

9/20

A Paradox? Homogeneity in the IMP Perspective

homogeneity and bounded rationality/cognition are dealt with in the IMP Perspective, and the

extent to which these issues are combined with the assumption of heterogeneity.

In general, we contend that homogeneity and bounded rationality/cognition are considered,

but only infrequently, and usually very implicitly in the IMP Perspective. Since they are not

combined, we shall address them in turn – starting off with homogeneity.

Among the few (early) discussions of the existence of homogeneity in the IMP Perspective,

we find Håkansson (1993) and Håkansson (1994). Håkansson (1993) discusses ‘networks as a

mechanism to develop resources’, and Håkansson (1994) discusses ‘economics of

technological relationships’. In both contributions it is stressed that the IMP Perspective

differs from ‘common’ economic perspectives by taking the assumption of heterogeneity as

opposed to ‘homogeneity’ of resources as a point of departure. However, this does not seem

to imply that homogeneity is altogether ignored or considered unimportant in the two

contributions. For example, in Håkansson (1993, p.214) it is stressed that “the heterogeneity

is probably on such a level that it is overwhelming for every single company. There is no

possibility for each of them to ‘utilize’ all of it. The question is more one of selecting some

aspects and ignoring others”. In addition, in Håkansson (1994, p.266) it is argued that there

are “reasons to take advantage of heterogeneity, but there are clearly positive effects of

treating counterparts as homogeneous. The most obvious reason is the economics of scale

which occur when, for example, customers are treated in a homogeneous way by a seller [..]

scale effects can occur if there is some homogeneous part of the solution, if there is some

specific activity or component which can be applied on a larger scale by the counterpart, for

example to serve several customers”. Furthermore, homogeneity is actually seen as a

prerequisite for the existence of relationships in the sense that “close relationships become

instrumental when there exists some homogeneous part of the heterogeneity” (Håkansson,

1994, p.267).

In a later contribution, resource heterogeneity and the possibility of disregarding it, is also

implicitly considered. As Håkansson and Waluszewski (2002) formulate it: “resources can be

seen as a source of development or as a point of reference” (p.40), “different actors’

perspectives of physical and social resources also have a strong impact on economic life. As

resources are formed through human interaction, image is an important ingredient that plays

a central role in business life” (p.39), and the features of resources “are interpreted,

10/20

A Paradox? Homogeneity in the IMP Perspective

developed and preceded by individuals” (p.38). Although they do not explicitly discuss these

issues in relation to the concepts of heterogeneity and bounded rationality/cognition,

Håkansson and Waluszewski (2002) seem to acknowledge (1) that resource heterogeneity

may be disregarded – as when a resource is used as a point of references instead of a source of

development, (2) that the way in which resources are viewed depends on how individuals

view and classify them – as when individuals’ perspectives and images influence how a

resource is seen, and therefore (3) that individuals and their frames are crucial for resource

development.

Based on the discussion above, we propose that we need to consider more explicitly the

duality between heterogeneity and homogeneity. One way of dealing with this duality is by

considering that both type (A) and type (B) can be either used or disregarded. Disregarding

heterogeneity of type (A) basically means that one does not consider that a single resource

may have other or additional uses than those already used (or known). Understanding how

heterogeneity of type (B) can be disregarded is somewhat trickier. In order to understand how

it is possible to disregard such heterogeneity we suggest the following definition: two

elements may appear to be (of) similar (value) when either is seen in one type of combination,

but that the same two elements may appear to be (of) different (value) when either are seen in

another type of combination. To understand this we can consider the following example: We

concluded above that the ASICs produced by Nordic VLSI represented heterogeneity of type

B. However, in some combinations, the differentiating characteristics of the various ASICs

may be disregarded, allowing all the ASICs to be considered as one, homogeneous group. For

example, it may be possible to use the same routines used when re-ordering or paying for any

one of the ASICs. The two types of heterogeneity, and what it implies to disregard each of

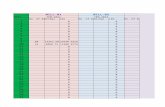

these, are tentatively depicted in figure 1.

-----Insert Figure 1 around here-----

Furthermore, we propose that both types of resource heterogeneity, and the fact that it may be

used or disregarded, are important and should be considered – more explicitly – in the IMP

Perspective and that this has implications for (1) which phenomena and concepts are proposed

(and which are disregarded) in the IMP Perspective, (2) how they are discussed and treated,

and the (3) managerial implications derivable from the perspective. In fact, we argue that

these issues would be obvious to address in relation to the assumption of bounded rationality/

11/20

A Paradox? Homogeneity in the IMP Perspective

cognition since it allows us to disregard ‘real’ heterogeneity thereby creating homogeneity.

Although ‘bounded rationality’ is evoked within the IMP Perspective (cf. Håkansson and

Johanson (1992) and Håkansson and Snehota (1995)), the concept is dealt with in a

‘background sort of way’ (cf. Foss, 2001) and there is no explicit discussion of the assumption

in relation to other assumptions, and the consequences for action and the emergence of

relationships, firm boundaries, and network structures.

Heterogeneity and the 4 Resource Entity Model

So far, we have not discerned between different types of resources but discussed them as ‘one

homogenous lot’. Recently, however, Håkansson and Waluszewski (2002) have proposed that

it is useful to discern between four different types of resources: products, production facilities,

business units, and business relationships. In this paper, we shall not enter into any kind of

comprehensive discussion of the merit of the framework, nor shall we consider that

interaction between the different entities is proposed to be the process, which creates and

enables development. Instead, we shall ‘just’ combine the resource categories in the

framework with the concepts and assumptions proposed earlier in the paper. Hence, we apply

the logic that the two types of heterogeneity proposed, and the assumptions that both can, and

often are, disregarded rather than made use of, should make sense in relation to all four types

of resource entities proposed by Håkansson and Waluszewski (2002). By combining their

model with our concepts and propositions, we get the following table (table 1). In order to test

whether or not we could make immediate sense of the 16 categories, which emerge, we made

use of our empirical insight for coming up with examples for each of the categories (see table

1, far-right column). The empirical insights stem primarily from the theses by Holmen (2001)

on the development of egg-shaped concrete pipes, Forbord (2003) on the development of the

use of milk, and Gressetvold (2003) on the development of electronic components in various

relationships.

-----Insert Table 1 around here-----

During this process we realised that it was possible to identify a huge number of examples for

each category. Therefore, we have delimited the examples presented to supply-side related

aspects only, although it would have been equally possible to focus on customers, to look

12/20

A Paradox? Homogeneity in the IMP Perspective

inside a company etc. Furthermore, we have delimited the examples to existing resources and

neither pay attention to creation of new resources (of whichever type) nor to creation of new

characteristics of existing resources (of whichever type).

Case Analysis

In order to assess the efficacy of the concepts when used in combination for understanding an

empirical phenomenon, we shall now analyse the case by means of the 16 concepts and

associated action strategies (cf. table 1). In order to keep the analysis short, we only focus on

VingCard and some of its action strategies in relation to the four different resource types.

Regarding products, several products are involved in the case. If we look at the focal product,

the ASIC, VingCard seems to apply the logics of ‘type (A) – use’ and ‘type (B) – disregard’.

VingCard intends to investigate if Nordic VLSI’s product, an ASIC, can be used in

combination with VingCard’s products. Furthermore, VingCard seems to disregard that the

ASIC may have characteristics which differentiate it from other ASICs. VingCard does not

seem to realise that an ASIC is developed and used for a specific application, and that the

designing firm owns the property rights to it. Regarding facilities, VingCard seems to apply

the logics of ‘type (A) – use’ and ‘type (B) – disregard’ in relation to Alcatel

Microelectronics. VingCard expects that some fab or another will be able to use its facilities

for producing an ASIC for the locking systems. However, at the same time VingCard

disregards (or is unaware of) the differences which exists among the production processes

(and blue books) of different fabs. This seems to be the reason why VingCard intends to have

dual supply of the ASIC but also the reason why VingCard has to give up its dual sourcing

policy for ASICs. Regarding relationships, we can observe that VingCard applies the logic of

‘type (B) – disregard’ in the sense that it disregards the characteristics which makes the

relationships between Nordic VLSI and Alcatel Microelectronics unique and non-

homogenisable from Nordic VLSI’s (possible) relationships to other fabs. VingCard also

applies ‘type (A) - use’ in relation to its other (complementary) suppliers by using some of its

existing suppliers for the new ASIC-based locking system. In relation to business units,

VingCard seems to apply the logics of ‘type (A) – disregard’ and ‘type (B) – disregard’.

VingCard is aware that Nordic VLSI so far primarily has dealt with customers who are

professional users of ASICs, familiar with the routines involved in design, production and use

of ASICs. Even so, VingCard does not consider that its, as a customer, represents a number of

13/20

A Paradox? Homogeneity in the IMP Perspective

challenges for and development of Nordic VLSI’s capabilities. In this manner, VingCard does

not regard its emerging use of Nordic VLSI as a case of ‘finding new uses of Nordic VLSI as

a business unit’ and the consequent need for experimentation with and development of Nordic

VLSI’s capabilities. In relation to Alcatel Microelectronics, VingCard apply the logic of ‘type

(B) – disregard’. Being unfamiliar with the field of ASICs, VingCard is unable to notice that

Alcatel Microelectronics may have capabilities, which sets it (partially) apart from other

manufacturers of ASICs. Its unfamiliarity with the field does not enable it to see the

heterogeneity amongst ASIC manufacturers, but regards these as a homogeneous lot (of type

(B)).

The case illustrates a number of issues. Firstly, it shows that a single episode, when seen from

a single actor’s point of view, can involve dealing with (1) the heterogeneity of all four types

of resource entities, (2) both types of resource heterogeneity in relation to these resource

entities and, furthermore, (3) applying different action strategies towards dealing with the

heterogeneity. We expect that, if we had analysed other actors (in addition to VingCard),

similar findings would have applied to these. Secondly, the case shows that when an actor

applies the strategy of disregarding heterogeneity, this approach may sometimes be

invalidated – some parts of the heterogeneity simply cannot be disregarded (from a

technological and/or economic point of view) in a particular situation. It is important to

understand that this in itself does not invalidate ‘disregarding heterogeneity’ as an action

strategy. In fact, disregarding heterogeneity is partly necessitated by the limitations on the

human decision-maker (bounded rationality/cognition), and is partly a sound strategy to reap

certain advantages from similarities (of activities) and to enable exploration and exploitation

(of resources). However, the case analysis points to the fact that the action strategy of

disregarding heterogeneity will sometimes fail. Thirdly, we can observe that even if the case

concerns technical development, a lot of heterogeneity (of type (A)) is not used. Hence,

development is not just a process of exploring heterogeneity (of type (A)), it also involves

disregarding a lot of heterogeneity – not all resource elements involved in development can be

treated as variables to be explored. The case also shows that homogeneity of type (B) –

among manufacturers of ASICs – may be assumed, but that this action strategy may later be

revised to considering heterogeneity of type (B), if the usefulness of the former action strategy

(disregard heterogeneity) is falsified.

14/20

A Paradox? Homogeneity in the IMP Perspective

Implications

We suggest:

(a) that homogeneity is, in fact, considered in the IMP Perspective, but needs to be paid much

more explicit attention,

(b) that one way in which homogeneity can be considered in the IMP Perspective is to view it

as a consequence of the assumption of heterogeneity when combined with the assumption

of bounded rationality/cognition – which, at present, is ‘recognised’ within the IMP

Perspective but which is not really made serious use of,

(c) that the assumption of heterogeneity comprises (at least) two different aspects –

heterogeneity of type (A) and type (B), and

(d) that both of these may be discussed in relation to alternative action strategies of ‘disregard

or use’.

Within the IMP Perspective development and (connected) relationships seem to be the two

main phenomena which are (partially) explained on the basis of heterogeneity. Development

is regarded as possible because ‘there is heterogeneity’, and relationships are regarded as

beneficial because ‘counterparts are heterogeneous’. We argue that development may be

better explained by considering both heterogeneity and homogeneity, and bounded

rationality/cognition. In particular, our case showed that development involves taking into

account some of the heterogeneity of some resources while, at the same time, disregarding a

lot (in fact, most) of the heterogeneity of most resources – thereby regarding these as

homogeneous. Several researchers within the IMP Perspective indirectly pay attention to

these issues, such as Holmen (2001), Forbord (2003), Gressetvold (2003), and Hjelmgren

(2003). Hence, heterogeneity may be a prerequisite for development, but homogeneity may be

equally necessary because no development would be possible if the action strategy used is to

‘use the heterogeneity’ of all resources involved in a development process. In short,

development = f(heterogeneity, bounded rationality/cognition, homogeneity).

Similarly, we argue that relationships (and networks) may be better explained as =

f(heterogeneity, bounded rationality/cognition, and homogeneity). We did not address this

issue in our case, but it is mentioned in Håkansson (1994) and implicitly discussed in Dubois

(1998) on the basis of Richardson (1972). Dubois (1998) argues that relationships exist when

activities of two firms are closely complementary and dissimilar. However, she also points out

15/20

A Paradox? Homogeneity in the IMP Perspective

that it is important for a firm to capture similarities among a company’s different

relationships. Such similarities (or connections), in effect, can be viewed as dimensions in

which two or more relationships are ‘homogenous’ (type (B)). In short, there must be “some

homogeneous part of the heterogeneity” (Håkansson, 1994, p.267) in order for relationships to

be useful. If no dimensions can be identified along which a single relationship can be

considered as part of a homogenous group (of minimum two) relationships, there is no (long-

term) economic basis for the existence of the relationship. In short, in order for a relationship

to exist, it must be connected to other relationships, and in order for such connections to exist,

some homogeneity (similarity) must exist – or be made to exist. Thereby, future research may

inquire into the concepts of and suggestions related to partial homogeneity (Alderson, 1965)

and partial heterogeneity, as well as to the dynamics – creation, existence, and decay – of

heterogeneity and homogeneity over time.

We suggest that researchers within the IMP Perspective in future pay more attention to

connecting the assumption related to actors (bounded rationality/cognition) to the assumptions

related to resources (heterogeneity, homogeneity). This implies that we need more research

into the action strategies which actors apply in relation to resources of whichever type –

including business relationships.

References

Alchian, A.A. and Demsetz, H. (1972) Production, Information Costs, and Economic

Organization, The American Economic Review, Vol. 62, pp. 777-795.

Alderson, W. (1965) Dynamic Marketing Behaviour. A Functionalist Theory of Marketing.

Richard D. Irwing, Inc. Homewood, Illinois.

Eco, U. (2000) Kant and the Platypus. Vintage/Random House, London.

Forbord, M. (2003) New Uses of an Agricultural Product? A Case Study of Development in

an Industrial Network, PhD thesis no.36, Department of Industrial Economics and

Technology Management, Norwegian University of Science and Technology.

16/20

A Paradox? Homogeneity in the IMP Perspective

Foss, N.J. (2001) Bounded Rationality in the Economics of Organization: Present Use and

(Some) Future Possibilities, Journal of Management and Governance, 5, pp.401-425.

Gressetvold, E. (2003) Developing Relationships within Industrial Networks – Effects of

Product Development, forthcoming PhD thesis, Department of Industrial Economics and

Technology Management, Norwegian University of Science and Technology.

Hayek, F. von (1952) The Sensory Order. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Hjelmgren, D. (2003) Adaptation and Development of Embedded Resources in Industrial

Networks, forthcoming PhD thesis, Department of Industrial Marketing, Chalmers University

of Technology, Gothenburg, Sweden.

Holmen, E. (2001) Notes on a Conceptualisation of Resource-related Embeddedness of

Interorganisational Product Development, Unpublished PhD thesis, Department of

Marketing, University of Southern Denmark.

Holmen, E. and Pedersen, A.-C. (1999) Exploring Assumptions Related to the

Concept of Resources in the Industrial Network Approach. Proceedings from

the 15th IMP International Conference, Dublin, Ireland, September 1999, pp. 1-21.

Håkansson, H. (1993) Networks as a Mechanism to Develop Resources, in P. Beije, J.

Groenewegen and O. Nuys (eds.), Networking in Dutch industries, pp. 207-223, Garant,

Apeldoorn.

Håkansson, H. (1994) Economics of Technological Relationships, in O. Granstrand (ed.),

Economics of Technology, pp. 253-270, Elsevier Science BV, the Netherlands.

Håkansson, H. and Johanson, J. (1992) A Model of Industrial Networks, in B. Axelsson and

G. Easton (eds.), Industrial Networks: A New View of Reality, pp. 28-34, Routledge, London.

Håkansson, H. and Snehota, I. (eds.) (1995) Developing Relationships in Business Networks.

Routledge, London.

17/20

A Paradox? Homogeneity in the IMP Perspective

Håkansson, H. and Waluszewski, A. (2002) Managing Technological Development.

Routledge, London.

Loasby, B.J. (1976) Choice, Complexity and Ignorance. Cambridge University Press,

Cambridge.

Loasby, B.J. (1999) Knowledge, Institutions and Evolution in Economics. Routledge, London.

Penrose, E. (1959) The Theory of the Growth of the Firm. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Simon, H. (1997) Models of Bounded Rationality Vol.3. The MIT Press, London.

Witt, U. (1996) Bounded Rationality, Social Learning, and Viable Moral Conduct in a

Prisoner’s Dilemma’ in E. Helmstädter and M. Perlman (eds.), Behavioral Norms,

Technological progress and Economic Dynamics: Studies in Schumpeterian Economics.

University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor.

18/20

A Paradox? Homogeneity in the IMP Perspective

Figure 1: Types of Heterogeneity and Disregard

Heterogeneity type (A) Heterogeneity type (B)

A=f(X)

A=f(Y)

Combination X

A

B A

Combination Y

B

A

Y

X

…combina-tions (x,y)…

Disregarding Heterogeneity type (A)

A=f(X)

A=f(Y)

A

Combination X

Combination Y

Disregarding Heterogeneity type (B)

A

A=f(Y) B=f(Y)

≠

= B=f(X) A=f(X) Combination X

Combination Y

19/20

≠

..resulting in view of resource as function of

….put into usein….

Heterogeneous resources (a,b)…

combination

Disregard

B

A P

arad

ox?

Hom

ogen

eity

in th

e IM

P Pe

rspe

ctiv

e

Tabl

e 1:

Het

erog

enei

ty a

nd A

ctio

n St

rate

gies

rela

ted

to th

e 4

Res

ourc

e En

titie

s

Res

ourc

e H

eter

o-ge

neity

A

ctio

n st

rate

gy

Mai

n co

nten

t and

impl

icat

ion

of a

ctio

n st

rate

gy

Exa

mpl

es

Dis

rega

rd

Focu

s on

com

bina

tions

in w

hich

a p

rodu

ct it

kno

wn

to b

e us

eful

K

eep

on u

sing

the

pro

duct

of

a pa

rticu

lar

supp

lier

in th

e sa

me

way

as i

t has

bee

n us

ed b

efor

e Ty

pe (A

)

Use

Fo

cus

on fi

ndin

g ne

w c

ombi

natio

ns in

whi

ch th

e pr

oduc

t may

be

usef

ul

Find

ing

(new

) w

ays

of u

sing

a s

uppl

ier’

s pr

oduc

t w

hich

ha

s bee

n m

ade

for o

ther

use

s, m

odifi

ed re

-buy

D

isre

gard

D

isre

gard

cha

ract

eris

tics

whi

ch m

ay d

iffer

entia

te t

he p

rodu

ct

from

oth

er p

rodu

cts w

hich

it se

ems p

artia

lly si

mila

r to

Dua

l or

mul

tiple

sou

rcin

g ex

istin

g pr

oduc

ts,

elec

troni

c au

ctio

ns, c

ompe

titiv

e te

nder

pro

cedu

res

Prod

uct

Type

(B)

Use

Pa

y at

tent

ion

to c

hara

cter

istic

s w

hich

diff

eren

tiate

the

pro

duct

fr

om o

ther

pro

duct

s whi

ch it

seem

s par

tially

sim

ilar t

o So

le, s

ingl

e or

par

alle

l sou

rcin

g fo

r exi

stin

g pr

oduc

ts

Dis

rega

rd

Focu

s on

com

bina

tions

in w

hich

the

faci

lity

it kn

own

to b

e us

eful

Le

tting

sup

plie

r re

peat

wel

l-kno

wn

prod

uctio

n pl

ans

for

exis

ting

mod

els

Type

(A)

Use

Fo

cus

on f

indi

ng n

ew c

ombi

natio

ns in

whi

ch th

e fa

cilit

y m

ay b

e us

eful

D

evel

opin

g ne

w p

rodu

cts

with

cha

ract

eris

tics

of s

uppl

ier’

s fa

cilit

y as

(one

) poi

nt o

f dep

artu

re

Dis

rega

rd

Dis

rega

rd c

hara

cter

istic

s whi

ch m

ay d

iffer

entia

te th

e fa

cilit

y fr

om

othe

r fac

ilitie

s whi

ch it

seem

s par

tially

sim

ilar t

o D

ual o

r m

ultip

le s

ourc

ing

for

plan

ned

futu

re p

rodu

cts

yet

to b

e de

velo

ped

Faci

lity

Type

(B)

Use

Pa

y at

tent

ion

to c

hara

cter

istic

s w

hich

diff

eren

tiate

the

fac

ility

fr

om o

ther

faci

litie

s whi

ch it

seem

s par

tially

sim

ilar t

o So

le,

sing

le

or

para

llel

sour

cing

fo

r pl

anne

d fu

ture

pr

oduc

ts y

et to

be

deve

lope

d D

isre

gard

K

eep

on u

sing

the

rela

tions

hip

for w

hat i

s alre

ady

used

for

Rou

tinis

atio

n of

pur

chas

ing

proc

esse

s, st

raig

ht re

-buy

Type

(A)

Use

Tr

y to

fin

d ne

w c

ombi

natio

ns i

n w

hich

the

rel

atio

nshi

p m

ay b

e us

eful

In

trodu

cing

a s

uppl

ier

to c

ompl

emen

tary

sup

plie

rs w

ith

who

m th

e fo

cal s

uppl

ier h

as n

ot y

et in

tera

cted

D

isre

gard

D

isre

gard

cha

ract

eris

tics

whi

ch m

ay d

iffer

entia

te th

e re

latio

nshi

p fr

om o

ther

rela

tions

hips

whi

ch it

seem

s par

tially

sim

ilar t

o Tr

ansf

errin

g su

pply

sch

emes

fro

m o

ne s

uppl

ier

to a

noth

er

supp

lier

Rel

atio

nshi

p

Type

(B)

Use

Pa

y at

tent

ion

to c

hara

cter

istic

s whi

ch d

iffer

entia

te th

e re

latio

nshi

p fr

om o

ther

rela

tions

hips

whi

ch it

seem

s par

tially

sim

ilar t

o M

odify

ing

qual

ity

assu

ranc

e pr

oced

ures

us

ed

for

one

supp

lier t

o fit

ano

ther

supp

lier

Dis

rega

rd

Focu

s on

com

bina

tions

in w

hich

the

busi

ness

uni

t it k

now

n to

be

usef

ul

Usi

ng c

apab

ilitie

s of

a s

uppl

ier

whi

ch h

ave

been

use

d be

fore

, e.g

. for

mak

ing

‘com

para

ble’

des

igns

Ty

pe (A

)

Use

Fo

cus

on f

indi

ng n

ew c

ombi

natio

ns i

n w

hich

the

bus

ines

s un

it m

ay b

e us

eful

U

sing

cap

abili

ties

of a

sup

plie

r w

hich

hav

e no

t ye

t be

en

used

by

the

com

pany

D

isre

gard

D

isre

gard

cha

ract

eris

tics

whi

ch m

ay d

iffer

entia

te t

he b

usin

ess

unit

from

oth

er b

usin

ess u

nits

whi

ch it

seem

s par

tially

sim

ilar t

o C

ompe

titiv

e te

nder

pr

oced

ures

, sw

itchi

ng

to

new

, un

know

n su

pplie

r, su

pplie

r por

tfolio

mod

els

Bus

ines

s U

nit

Type

(B)

Use

Pa

y at

tent

ion

to c

hara

cter

istic

s w

hich

diff

eren

tiate

the

bus

ines

s un

it fr

om o

ther

bus

ines

s uni

ts w

hich

it se

ems p

artia

lly si

mila

r to

Letti

ng

diff

eren

t su

pplie

rs,

with

di

ffer

ent

capa

bilit

ies,

deve

lop

alte

rnat

ive

desi

gns o

f new

pro

duct