A New Way, or an Old Way: Lessons from the American West

-

Upload

boisestate -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of A New Way, or an Old Way: Lessons from the American West

A New Way, or an Old Way?

Dean Gunderson

The Problem

What do we do with the failed American Town? Are there examples of successful and

sustainable communities that can demonstrate how to avoid catastrophic failures?

Firstly, you may question the premise of “failure” -- and this critical attribution to

American towns. Indeed, America is one of the most prosperous nations in the history of

mankind, and its towns (with their commercial conveniences, parks, schools, and public

amenities) are the very embodiment of that success. Yet, there are some failures if you

take into account certain isolated economic troubles. There has been a recent spate of

municipal bankruptcies, and some examples of towns undergoing massive population

contractions -- Detroit, Michigan appearing to be the lead contender as the poster child

for both phenomena. Also, the 2007 collapse of the home mortgage industry seems to

have caught most everyone by surprise -- especially the 20-25% of American

homeowners who still, by 2013, owed more on their mortgages than their property was

worth (Pew Research, Housing and Jobs). Yet surely these problems are isolated and

few in number, and cannot be taken as an indictment of the whole concept of the

American Town.

Perhaps a better way to express the damning question is to rephrase it as the pending

failure of the American Town. Why “pending”? We see examples all around us of

economic prosperity, perhaps no greater example than that of the personal automobile.

And, aren’t our towns perfectly suited for this modern contrivance? Haven’t they, in fact,

been perfectly tuned to accommodate the automobile -- in the way that our land use

patterns are segregated & dispersed, and the way our land is intersected by

causeways, freeways, overpasses, frontage roads, highways, and the dendritic pattern

of local streets? How could anyone say that a nation so intertwined with the

technological needs of modern transportation be categorized as a pending failure?

Haven’t we, as a nation, managed to leverage-up the technology of the personal

automobile to such heights as to make the tiresome activity of walking not only virtually

obsolete, actually inimical to the proper functioning of our towns?

Yet, upon what presumption is automobile technology most firmly based -- except that

of the notion of cheap, perpetually available, and plentiful petroleum fuel (gasoline or

diesel)? Given that the average American family now expends 19 percent of its income

on transportation alone, a figure that is growing with each year and is now the second

highest household expense (more than the cost of food and only slightly less than the

cost of securing shelter) (Bureau of Labor Statistics, Consumer Expenditures Survey),

does anyone really believe that in 25 or 30 years we will continue to be able to support

such a technology? Is there anything in the past 25 or 30 years (or 50 or 60 years) that

would lead one to believe that either our manufacturing industries will shift their fuel

sources -- or that we, ourselves, will change our habits?

So, as our costs to “use” our towns (in the form of transportation expenditures) increase

with each year, at what point will we simply no longer be able to live in our current

towns? Isn’t it more accurate to state that our towns, your’s and mine, are based on a

piece of technology whose demise is imminent? Isn’t it fairer to assert that this collapse

will occur well within the lifetime of the mortgages on the homes built within our auto-

dependent subdivisions and use-segregated communities?

So yes, within the next 20 to 30 years the American Town will likely undergo a

catastrophic economic failure. Our suburbs, and our far-flung communities, will shudder

through a long economic blight as we struggle to retrofit our existing development

patterns to resist our over-dependence on automobile travel. And, many of these

communities will simply cease to exist -- crushed under mounting debt as their tax-

bases diminish and their populations decline.

A New/Old Hope

But there is hope. Not too long ago we built towns that were self-reliant and whose

citizens had no need for personal automobiles -- not for getting to work, getting to

school, securing access to quality food, or to participate in the democratic governance

of their towns. People walked, could actually choose to only walk, and still lead

productive, prosperous and happy lives.

Prior to the advent of the automobile we were building new towns, even rebuilding

portions of existing cities -- and under adverse technological and economic

circumstances. Perhaps the greatest of those adversities being the settlement of the

arid American West, with its desert-like conditions appearing to guarantee the

importation of all food-stuff -- an economic overhead that would seem to doom any long-

term settlement of over one-half of the nation’s land mass. This appeared to leave

frontier town creation doomed to no greater sophistication than the carving out of crude

mining and timber harvest camps from the wilds -- or the construction of cities along rail

corridors or navigable rivers. Yet, with the development of a vast network of gravity-fed

surface irrigation improvements water could be brought to the desert, permitting the

flourishing of both crops and towns -- neither of which required the technological

innovation of the automobile.

An Example from the Past

One of the most intriguing of these towns is New Plymouth, Idaho. The formation of this

community in 1895 is unlike most towns in the American West, in that it was not formed

as a speculative venture in the conventional sense. That is, it was not a village formed

around any type of extraction industry -- mining or timber -- nor, despite its name, was it

a settlement formed to avoid the religious persecution of its inhabitants -- akin to the

contemporary efforts of Mormons in the Utah territory. Neither was the town located on

a principal rail line or a river over which one could travel or transport goods. Further, the

village (or colony, as it was called) was first conceived of, and settled, by middle-class

urbanites from the city of Chicago who worked in a number of professional fields. These

“colonists” weren’t hardscrabble pioneering settlers who were searching for a chance to

trade their sweat equity for a small plot of arable land, they were people seeking a

different life than what they could find in the large cities of 19th Century America. And,

they were helped along the way with the guidance of some of the most notable social

leaders and authors in America at the time. Perhaps it’s more accurate to say that New

Plymouth was a vessel formed by the confluence of a number of social movements in

the latter half of the 19th Century, and populated by people who had a firm belief in

those causes.

To fully understand the creation and settlement of New Plymouth it’s best to place it

within its proper social context, an economic and political milieu strikingly similar to our

own. Towards the end of the 19th Century, a growing social unrest had been creeping

throughout America, a general dissatisfaction with the economic status quo which

appeared to favor the monopolistic exploits of industrial giants at the expense of the

hardworking middle- and lower-classes. While Washington, D.C. seemed to be filled

with politicians more intent on lining their own pockets with lucrative business deals, or

preserving their political alliances, than with addressing the needs of the American

public. Though this frustration had been growing since the 1850’s, it reached a peak

during the economic depression of 1894. This recession fueled the exploration of both

new forms of communities and new forms of governance.

It’s Founding in Literary Works

In the twenty-five years before the founding of New Plymouth a number of prominent

thinkers in America were dedicating themselves to the re-creation of the American

metropolis. Some of these exploits took the form of fictional novels -- like the 1869

utopian book Sybaris and Other Homes by Edward Everett Hale (a Boston

Transcendentalist Unitarian minister and social theosophist). In his book, Hale

expounded upon the idea of quality housing for the working classes and the poor. The

most notable author from this period was Edward Bellamy. In his 1888 science fiction

novel Looking Backwards: 2000-1887, Bellamy recounted the travels of a long-lived

man who looks back across 113 years of American progress. Specifically, the novel

highlights the contemporary economic and social flaws in America while mapping out a

utopian future that had solved these seemingly intractable problems.

Here, the principal character of Looking Backwards, Julian West, attempts to explain the

economic and social conditions of late 19th Century America.

“ … perhaps I cannot do better than to compare society as it was then to a

prodigious coach which the masses of humanity were harnessed to and dragged

toilsomely along a very hilly and sandy road. The driver was hunger, and

permitted no lagging, though the pace was necessarily very slow. Despite the

difficulty of drawing the coach at all along so hard a road, the top was covered

with passengers who never got down, even at the steepest ascents. The seats

on top were very breezy and comfortable. Well up out of the dust, their occupants

could enjoy the scenery at their leisure, and critically discuss the merits of the

straining team.” (Bellamy, Looking Backwards)

The fans of this book (who took to calling themselves Bellamyites) took it upon

themselves to form social-improvement clubs dedicated to the realization of the novel’s

predictions. At Bellamy’s urging, these associations, originally named after himself,

were re-organized as Nationalist Clubs -- since their focus was upon the improvement

of the American nation and to advocate for the nationalization of industry. Since their

beginnings, these clubs attracted the interest of Christian Socialists who saw in

Bellamy’s novel a way to realign American culture and impart a stronger Christian

ethos. Many of these members were also proponents of women’s suffrage and

participated in the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WTCU). The WTCU

preached against the evils of alcohol and took the efforts of passing a constitutional

amendment that would prohibit the production, sale and consumption of inebriants in

the U.S as a moral imperative for the health of the nation. One of the more engaged

members in the first Nationalist Club in Boston was Edward Everett Hale, a personal

friend of Edward Bellamy’s. While in the city of Chicago, the National Club’s

membership included many of the participants of the already extant Collectivist League,

a socialist political organization strongly aligned with the interest of Trade Unionists. The

League would eventually change its name to the Nationalist Club of Illinois, and by the

early nineteen hundreds the politically progressive attorney Clarence Darrow was

serving as the club’s president.

Looking Forwards

By the early 1890’s, the Nationalist Clubs had engaged in the American political process

by contributing to the formation of a strong third political party, the progressive Populist

(or People’s) Party. The party enjoyed so much success that it would field its own

presidential candidate in the 1892 national election, James B. Weaver. This People’s

Party candidate would would garner all the electoral votes from the four western states

of Kansas, Colorado, Nevada, and Idaho (while receiving a portion of the electoral votes

from both Oregon and North Dakota). Until the early 1960’s, Looking Backwards would

be considered one of the most socially influential of American novels, with more copies

being sold than any other U.S. novel, except Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s

Cabin.

Looking Backwards also had an impact in Great Britain. In fact, the London publication

of the novel was personally underwritten by the writer and British parliamentary civil

servant, Ebenezer Howard. Howard reserved the first 100 copies of the novel, and over

the next few years passed out the book as gifts to his closest friends. Many of the

cultural and social improvements mentioned in Looking Backwards would eventually be

included by Howard in his own 1902 publication, Garden Cities of To-morrow; which

proposed a radical new way to design and layout new communities. Those of Howard’s

friends influenced by Looking Backwards (many of whom were British politicians),

formed the corpus of the British Garden City Movement; which influences the

development of towns and villages in Great Britain to this very day.

To Cooperate, or Not?

In 1894, the same year that New Plymouth was being formed by the Chicago collective,

William Dean Howells wrote the novel, A Traveler from Altruria, where he explored the

ideals of the utopic foreign nation of Altruria -- a country based on the notion of the

“cooperative commonwealth”. The traveler from this novel, Mr. Homos, is from a

country that we, today, would refer to as a communist utopia -- a place where

distinctions between workers and owners are non-existent, and where almost every

citizen is engaged in small-scale farming. Mr. Homos’ country of Altruria is a perfect

embodiment of a cooperative commonwealth, where all resources are shared and all

benefits of work are shared amongst those who actually labor. Howells uses his novel to

critique contemporary America, and highlight the dystopic inequities found in embedded

in American society.

During the episodic economic downturns in America during the latter half of the 19th

Century there were surges in socialist community building. Over 25 such communities

arose between 1843 and 1900, fifteen of them just in the seven year after 1893. Many

of the members of these new communities were Bellamyites, intent on re-casting

America as a coast-to-coast cooperative commonwealth. These were communities

whose memberships were often restricted to those who pledged to engage in socialist

political reform, and further, where private property ownership was strictly limited. Many

of these communities began to fail within a few years (or decades) due to internal

conflicts between members and poor community leadership. Disagreements ranged

over issues such as the ownership of homes, to the admission of non-skilled laborers

into the commonwealth.

Although there is some discussion as to whether the colony of New Plymouth was

intended to be a cooperative commonwealth -- a number of the original documents from

the formation of the colony corporation refer to it as a commonwealth, and William

Smythe often referred to co-operation in his writings about the village -- it is clear that

only the parks, school, roads, and community hall were to be owned collectively by the

membership. The colonists homes, their “home acres” (located in the village), and the

farm tracts themselves were privately owned by the individual members.

The settlers of New Plymouth -- self-styled as colonists -- placed upon themselves a

number of larger social expectations. They did feel that their village, by example, would

help usher in a new type of American town. And, although private property ownership

was lauded as a panacea for many social ills (and political participation was not

mandated, as was the case in mainline cooperative commonwealths), there were a

number of legal restrictions placed upon membership in the colony -- not the least of

which was the prohibition on alcohol sales. Many of the colonists were members in the

Women’s Christian Temperance Union, an affiliation that contributed to the addition of a

morality clause written into the land deeds of all the colonist. If it were discovered that

alcohol were being sold on any parcel of land within the colony, the parcel’s owner

would forfeit his or her title to the land -- ownership reverting back to the colony

company. Though perhaps more peculiarly, actual deed ownership could rest with an

unmarried woman -- a condition that was legally prohibited in most American states at

the time.

Women formed a large contingent of the early colonists, not only as the wives and

relatives of male landowners/farmers, but as equals -- some of whom also owned and

operated their own farms, using the Colony corporation as the middleman to legally

secure the deeds to their property. One of the most active social organization in the

colony was the all-female Portia Club whose purpose, most amazingly, was to establish

and oversee the physical improvements of the new village.

The Village as Template

The village’s layout is a sterling example of the soon-to-be-formed Garden City

Movement -- and, strangely enough, the village’s street pattern mimics many of the

features written about and illustrated by Ebenezer Howard in his book Garden Cities of

To-morrow, though Howard’s book would not be published in England until seven years

after the village’s formation.

An illustration from Ebenezer Howard’s Garden Cities of To-morrow (1902), note the

similarities between the Grand Boulevard and and the radial streets, and New

Plymouth’s nearly identical street layout.

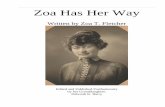

The frontpiece illustration from the New Plymouth Colony Co. (Ltd.) pamphlet.

This pamphlet was published in 1896, a year after the first colonist had arrived -- notice

the radial streets and the parklike circular boulevard, with industrial factory land being

relegated to the railroad frontage at the north of the town (the rail itself would not be

extended to New Plymouth for another 15 years). Also, note the central park containing

the public school and the Village Hall -- all features replicated by Howard in his Garden

Cities book some seven years later.

Perhaps closer to the founding of the New Plymouth village was the 1896 publication of

Theodor Fritsch’s book, The City of the Future in Germany. Although like Howard,

Fritsch also advocated for a return to the land through the creation of rural agrarian

villages, as an anti-Semite he did so with a specific racial “cleansing” purpose. As

radically left as the socialist commonwealths were in America, Fritsche’s new “Garden

Cities” were radically reactionary to be used as a way to liberate the Aryan people from

what he saw as a Jewish oligarchical control of the Stock Market and farm-based food

production.

(QTD in Schubert 11), originally illustrated in Theodor Fritsch’s The City of Future:

Garden City

(QTD in Schubert 12) originally illustrated in Theodor Fritsch’s The City of the Future:

Garden City

Note the striking similarities between Fritsch’s 1896 illustrations, and the illustration of

New Plymouth (from its own 1896 pamphlet). Fritsch though, still held to the notion of

collective ownership of the village’s surrounding farms -- and though he would go on to

publish a great number of Neo-Socialist political tracts, forming the backbone of Nazi

Germany’s literary heritage, this publication on Garden Cities was his only book on

urban design and theory.

Imaginary Flights

During the years right after the formation of the village of New Plymouth, it sparked the

imagination of a number of writers and theorists, most of whom appeared to have more

interest in promoting their own agenda than those of the actual colonists.

In 1898 the Oregon-based writer Francis H. Clarke penned a science fiction novel that

exactly mimicked the initial formation of the colony. Ms. Clarke authored her novel

under the male pen-name Zebina Forbush (a quirky nom de plume derived from old

New England family names) and saw it published by a Chicago-based company that

specialized in socialist and communist literature. In her novel Ms. Clarke envisions a

nation-wide cultural revolution based on the idea of a nationalized industrial army --

itself first finding expression in the small fictional town of Co-opolis (modeled after the

New Plymouth colony). Here, the narrator of the story (Mr. Braden), while residing in

Chicago, recounts his first conversation with the leader of the co-operative colonization

effort (Mr. Thompson)

“The project which my new acquaintance outlined was one which I at once

pronounced as visionary. It was, he said, the design of certain gentlemen, some

of whom lived in Chicago, to organize what they called the Co-operative

Commonwealth. These gentlemen had decided to induce laboring men and other

persons who might be willing to associate themselves in the work to form co-

operative societies and to colonize them in some one state, so that, in process of

time, they would outvote the devotees of the old system. When this desired result

was achieved, they made no doubt that the Co-operative Commonwealth would

be established and present to the entire world an example of prosperity which

would rouse an unquenchable spirit of emulation. (Clarke, The Co-Opolitan)

It was the character of Mr. Braden that convinced the Co-operative Commonwealth to

strike out for Idaho and to build their first village in the Payette Valley (renamed Deer

Valley in the novel).

The Colonists

Ultimately though, it was the simple lives of the early colonists that hold the greatest

interest to a contemporary reader and urban theorist. They felt that, by example alone,

their village would encourage others to lead similar lives. They also did not shy away

from the difficulties presented by the building of a village out of a sage-brushed valley, a

day’s travel from the nearest town.

“I cannot conceive of a more cheerless prospect than that which confronts the

man who settles the west on a farm, distant from neighbors and without friends

with whom he can share a common interest.” (Shawhan, Statesman)

In fact, it was with a mixture of pride and stubborn determinism that they stuck to their

original plan -- while facing the myriad unplanned occurrences with a loving and

neighborly attitude.

“The history of the Plymouth colony is by no means made as yet. It is too early by

5 or 10 years to say what its influence will be for the life of this state. The period

of struggle is not over, but the day of doubt as to its permanence and as to its

exceptionally high character is past. It will live and will be a source of pride to all

the people of Idaho.” (Women of New Plymouth, A New Baby, Statesman).

Perhaps no better summation of the early colonists’ motivations can be found in Meta

Louis Ingalls’ 1912 recollection:

“It is just fourteen years since I left Chicago to come to sunny southern Idaho. It

was like pulling things up by the roots and transplanting myself in this small

village. However, all’s well that ends well. My experiences here have given me a

larger outlook on Life, and increased my vision beyond the streets, parks, and

boulevards of a great and busy city which was my home for twenty-eight years.

In other words, I have learned what it means to be in sympathy with my neighbor

and to keep close touch with community life. “You dear people who live in large

cities and apartment houses, scarcely have time or a desire to know your next-

door-neighbor. There is that eternal mad rush for business and pleasure that one

don’t (sic) take time to think in terms of love, or “kindly fellowship”. Love, as you

know is but another name for the unseen presence by which the Soul is

connected with humanity.” (Ingalls, 1912)

Can we gather a better means towards sustainability from the story of this small, and

still extant, Idaho town? I believe there are valuable lessons to learn, not only about our

personal motivations regarding the recent “green” movement -- but also in regards to

the primacy the land, and simple agricultural pursuits, plays in any true sustainable

effort. Certainly, there are urban design methods that can be extrapolated from the town

layout of New Plymouth -- a village that seemed to ride the wave of late 19th Century

international enthusiasm in urban planning. But, perhaps there’s something deeper --

more significant -- that led to the town’s formation, and its long-term sustainability.

Lessons that we have yet to learn.

Bibliography

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2011). Consumer Expenditures Survey: 2011.

http://www.bls.gov/cex/

Pew Research: Center for the People & the Press. (2011). The Generation Gap and the

2012 Election, Section 5: Generations and the Great Recession

http://www.people-press.org/2011/11/03/section-5-generations-and-the-great-recession/

Schubert, Dirk. "Theodor Fritsch And The German (Völkische) Version Of The Garden

City: The Garden City Invented Two Years Before Ebenezer Howard." Planning

Perspectives 19.1 (2004): 3-35. Academic Search Premier. Web. 25 Feb. 2013.

Berry, Brian J. L. America's Utopian Experiments: Communal Havens from Long-Wave

Crises. Hanover, N.H: University Press of New England, 1992. Print.

WOLF, Peter. "Structure Of Motion In The City." Art In America 57.(1969): 66-75.

Readers' Guide Retrospective: 1890-1982 (H.W. Wilson). Web. 26 Feb. 2013.

“Plymouth Committee; Chicagoans Sent Out to Report on William E. Smythe’s

Enterprise.” Idaho Statesman 16 May 1895: 3. Print (online archive)

“New Plymouth Colony; The Committee Makes an Entirely Favorable Report.” Idaho

Statesman 23 May 1895: 1. Print (online archive)

“New Plymouth Colony; Settlers Arriving Slowly and Taking Possession.” Idaho

Statesman 9 Oct. 1895: 4. Print (online archive)

Lindenfeld, F (2003). "The Cooperative Commonwealth: An Alternative to Corporate

Capitalism and State Socialism (1997)". Humanity & society (0160-5976), 27, p. 578.

Howells, William D. A Traveler from Altruria. New York: Sagamore Press, 1957. Print.

Schultz, Stanley K. Constructing Urban Culture: American Cities and City Planning,

1800-1920. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1989. Print.

Goldsmith, Claire. In the Shadow of the Squaw. Caldwell: Caxton Printers, Inc., 1953.

Smythe, William E. The Conquest of Arid America. New York: The McMilliam Company,

1905. Print

Smythe, William E. City Homes on Country Lanes. New York: The McMillian Company,

1921. Print

Forbush, Zebina. The Co-Oplitan: A Story of the Co-operative Commonwealth of Idaho.

Chicago: Charles H. Kerr & Company, 1898. Print

Bellamy, Edward. Looking Backwards: 2000 - 1887. Boston: Ticknor and Company,

1887. Print

Howard, Ebenezer. Garden Cities of To-morrow. London: Swan Sonnenschein & Co.,

Ltd., 1902 Print

Shawhan, B.P. “Work of Colonization.” Idaho Statesman 6 April 1896: 4 Print

“New Plymouth Colony; Mr. Smythe Talks of His Recent Visit to It.” Idaho Statesman 27

March 1898: 3 Print

“The Puritan Club; First Anniversary of This Organization.” Idaho Statesman 22 January

1898 Print

“Reminiscence of a Colonist: Meta Louis Ingalls” Idaho State Historical Archives 1912

“County & State; Idaho’s Baby.” Idaho Statesman 29 June 1896 Print

“Idaho History 1850 - 1899.” Idaho State University and Idaho Museum of Natural

History

<http://imnh.isu.edu/digitalatlas/geog/historic/histtxt/1899.htm>

“Irrigation in Idaho” Idaho State Historical Society, Reference Series, Number 260, June

1971

<http://history.idaho.gov/sites/default/files/uploads/reference-series/0260.pdf>