A Demotic Narrative in Berlin and Brooklyn concerning the Assyrian Invasion of Egypt

Transcript of A Demotic Narrative in Berlin and Brooklyn concerning the Assyrian Invasion of Egypt

© A

kadem

ie Verlag

. This d

ocu

men

t is pro

tected b

y Germ

an co

pyrig

ht law

. You

may co

py an

d d

istribu

te this d

ocu

men

t for yo

ur p

erson

al use o

nly. O

ther u

se is on

ly allow

ed w

ith w

ritten p

ermissio

n b

y the co

pyrig

ht h

old

er.

337ADemotic Narrative in Berlin and Brooklyn concerning the Assyrian Invasion of Egypt

A Demotic Narrative in Berlin and Brooklyn concerningthe Assyrian Invasion of Egypt(Pap. Berlin P. 15682 + Pap. Brooklyn 47.218.21-B)*

Kim Ryholt, Kopenhagen

A recent publication saw the edition of a new fragment of a demotic narrative concerning the Assyr-ian invasion of Egypt.1 This is one of a considerable number of historical narratives from the Greco-Roman period that refer to or are set in the time of this — from an Egyptian point of view — highlytraumatic event; the conflict took place in the 7th century BC and left a deep scar on Egyptian his-torical conscience that would not be erased until the end of the ancient culture, nearly a millenniumlater.2 The purpose of the present contribution is to bring attention to the fact that another fragment ofthe same papyrus in Brooklyn was already published some years ago3 and to present a number of newreadings in both fragments that help clarify the nature of the extant remains of the story.

That the two fragments in Berlin and Brooklyn belong to the same manuscript is clear from thefact that:• both fragments preserve parts of a demotic narrative which includes two characters called @r-aw

son of PA-i.ir-kpe and Amyrtaios, as well as a pharaoh and a rms-boat• the demotic text is written in identical hands on the verso of a re-used papyrus• the recto of both fragments preserves a Greek document which is similarly written in identical

handsThe name @r-aw was not read in either edition. It is, however, the patronymic PA-i.ir-kpe that is mostimportant for the identification since it is rather uncommon. It is so far otherwise unattested in de-motic, but occurs a few times in hieroglyphics.4 By contrast the name Amyrtaios (Imn-i.ir-di.t-s) isquite common.

It is even possible that the Brooklyn fragment belongs to the same column as the Berlin fragment,more specifically at some distance to its right, since both mention a rms-boat in line 4 and Amyrtaiosin lines 4 and 5 respectively. This, however, remains no more than a possibility since it is not certainif the first preserved line of the Berlin fragment actually represents the first line of the column.

* I am grateful to Karl-Theodor Zauzich and Ed Bleiberg for providing me with excellent digital photographs ofthe Berlin and Brooklyn fragments respectively, which greatly facilitated several of the new readings. All rea-dings were checked against the originals during a visit to Berlin and Brooklyn in 2011 and 2012. I am also verygrateful to Cary Martin for checking the English text.

1 Karl-Theodor Zauzich, Serpot und Semiramis, in: Jeanette C. Fincke (ed.), Festschrift für Gernot Wilhelm an-läßlich seines 65. Geburtstages am 28. Januar 2010, Dresden 2010, 447–465.

2 For an overview, see Kim Ryholt, The Assyrian Invasion of Egypt in Egyptian Literary Tradition, in: Jan GerritDercksen (ed.), Assyria and Beyond: Studies Presented to Mogens Trolle Larsen, Leiden 2004, 484–511. Thetext discussed in the present paper is briefly cited on 499–500.

3 George R. Hughes, Brian P. Muhs & Steve Vinson, Catalog of Demotic Texts in the Brooklyn Museum, OrientalInstitute Communications 29, Chicago 2005, 13, pl. 17, no. 29.

4 Cf. references provided by Zauzich, Serpot und Semiramis, 458.

© A

kadem

ie Verlag

. This d

ocu

men

t is pro

tected b

y Germ

an co

pyrig

ht law

. You

may co

py an

d d

istribu

te this d

ocu

men

t for yo

ur p

erson

al use o

nly. O

ther u

se is on

ly allow

ed w

ith w

ritten p

ermissio

n b

y the co

pyrig

ht h

old

er.

338 Kim Ryholt, Kopenhagen

Although neither fragment has a recorded provenance, the characteristic script can be assignedwith some certainty to the Fayum. It is written in a well-attested hand that is best known from theversion of the Insinger Wisdom Text preserved in Pap. Carlsberg 2 and the story of Petechons andSarpot (also known as Egyptians and Amazons) preserved in two Vienna papyri.5 Its more specificorigin has not yet been identified with certainty. The known texts written in this hand are certainlynot the product of a single scribe since the different manuscripts reveal consistent variation in specificdetails. It is noteworthy that several manuscripts use blank spaces or spatiae between words to indi-cate new episodes. Apparently this was customary in this specific scribal school. Thus, for instance,the present text uses a spatium before the common formula xpr tawy n pAy=f rsty, ‘Came the dawn ofthe following morning ...’ (lines 10 and 15), as do both Pap. Vienna D 6165 (3.29)6 and Pap. BM EA76185 (line 7).7

It may be added to the physical description of the papyrus that it would have been at least c. 31cm tall to judge from the two fragments here discussed. The Berlin fragment measures just short of28 cm and preserves a text mirror of 24½ cm and a blank bottom margin of 3½ cm. The Brooklynfragment preserves a blank top margin of 3 cm. Since c. 31 cm corresponds to the standard ‘sacredmeasure’ (Dsr) of four palms or 30½ cm attested for a range of demotic and hieratic papyri of the Ro-man period, this could represent the original height of the papyrus. However, papyri inscribed in thisparticular hand vary in size and it cannot be taken for granted that the present papyrus conforms toa specific measure; thus the manuscript of the Insinger Wisdom Text mentioned above measures just18½ cm in height, whereas the better preserved of the two manuscripts inscribed with the Petechonsand Sarpot story measures 34½ cm.8

Pap. Brooklyn 47.218.21-B

The Brooklyn fragment is listed in a posthumous catalogue of the demotic papyri and ostraca in theBrooklyn Museum by George Hughes. The publication, originally intended as a check-list, includeda translation of two lines and an image of the papyrus. I commented briefly on the nature of the smallfragment and presented some further readings in my review of the catalogue9 and offer here a fulltransliteration and translation with a few additional new readings.

Top margin

1 ---] pr-aA @r-aw sA PA-i. &ir\-[k] &p\ [e ---2 ---] iw r tA mtr.t n pA wrx [---3 --- Hr]flesh tA mr.t n pA mSa n pA krH [---

5 Cf. the discussion of the hand in Kim Ryholt, Narrative Literature from the Tebtunis Temple Library, CarstenNiebuhr Institute Publications 35, The Carlsberg Papyri 10, Copenhagen in press, 144–145, where references tofurther texts written in this hand can be found.

6 Friedhelm Hoffmann, Ägypter und Amazonen: Neubearbeitung zweier demotischer Papyri P. Vindob. D 6165und P. Vindob. D 6165 A, Mitteilungen aus der Papyrussammlung der Österreichischen Nationalbibliothek(Papyrus Erzherzog Rainer), Neue Serie 24, Wien 1995.

7 Unpublished; I am preparing an edition of the fragment.8 The measurements are based on personal observation; they are not clearly indicated in the published text edi-

tions.9 Kim Ryholt, review: George R. Hughes: Catalog of Demotic Texts in the Brooklyn Museum, in: Journal of Near

Eastern Studies 70,1 (2011), 111–113.

© A

kadem

ie Verlag

. This d

ocu

men

t is pro

tected b

y Germ

an co

pyrig

ht law

. You

may co

py an

d d

istribu

te this d

ocu

men

t for yo

ur p

erson

al use o

nly. O

ther u

se is on

ly allow

ed w

ith w

ritten p

ermissio

n b

y the co

pyrig

ht h

old

er.

339ADemotic Narrative in Berlin and Brooklyn concerning the Assyrian Invasion of Egypt

4 ---] rms n Imn-i.ir-di.t-s &iw=f \ iw r tA [---5 ---]. n rn=s n-m-bAH pr-aA .[---6 ---]. nAy-ir=k &s\ Dd n=f Imn-[i.ir-di.t-s ---7 --- s]my n pA mSa [---8 ---] Dd pr-aA [---9 ---] &nA rmt.w\ [---

1 ---] pharaoh. O, @r-aw son of PA-i.ir-kpe [---2 ---] came to the middle of the court [---3 --- on] the fleet of the army in the night [---4 ---] boat of Amyrtaios and it/he came to the [---5 ---] aforementioned [...] before pharaoh [---6 ---] these things which you did. Amy[rtaios] said to him [---7 ---] report of the army [---8 ---] pharaoh said [---9 ---] the men [---

Line 1Restore perhaps ‘Pharaoh said: O, @r-aw son of PA-i.ir-kpe’.

Line 5The traces before n rn=smight be the sun disc and feminine -t in which case we could restore tAy Hty.tn rn=s, ‘this very moment, instantly’.

The traces after pr-aA would be compatible with ta, cf. &a-nA in the Berlin fragment, line 30.

Pap. Berlin P. 15682: new readings

Line 1At the beginning of the line there is a trace of the pronoun =f before r tA m[t]kv. The two traces at theend of the line would be compatible with the verb iw, ‘come’.

Line 2The words smH wnm n-im=f, ‘left and right of him’, presumably describe leaders standing on the twosides of pharaoh during an audience.10 Compare, e.g., Setne and Siosiris (2.4-5) and Petechons andSarpot (2.8-9). In the former ‘Setne saw the divine form of Osiris, the great god, seated upon his thro-ne of fine gold (...), while the gods, the officials, and the men of theWest were standing to the left andright of him (aHa r smH wnm n-im=f)’,11 while in the latter ‘Sarpot, the Queen of the Land of the Wo-men was sitting [on a throne ?] in her tent, [while the ...] were standing to the left and right of her (aHa

10 For the reading of the demotic group for ‘right’ as smH, rather than the traditionally used transliteration iAby, seeJoachim Friedrich Quack, Zur Lesung der demotischen Gruppe für “links”, in: Enchoria 32 (2010–11), 73–80.I am grateful to the author for providing me with an early copy of this paper.

11 Francis Llewellyn Griffith, Stories of the High Priests of Memphis: The Sethon of Herodotus and the DemoticTales of Khamuas, Oxford 1900, 152–153.

© A

kadem

ie Verlag

. This d

ocu

men

t is pro

tected b

y Germ

an co

pyrig

ht law

. You

may co

py an

d d

istribu

te this d

ocu

men

t for yo

ur p

erson

al use o

nly. O

ther u

se is on

ly allow

ed w

ith w

ritten p

ermissio

n b

y the co

pyrig

ht h

old

er.

340 Kim Ryholt, Kopenhagen

r smH wnm n-im=s).’12 A slight variant occurs in an unnumbered Carlsberg papyrus where someonesits on a throne of gold, ‘while there were gods on the left and on the right of him (r wn hyny ntr.w HrsmH Hr wnm n-im=f).’

Line 4The first signs, which puzzled the editor, almost certainly represent the toponym determinative. Thesmall spot of ink above the second sign is just a space filler. The space filler is used occasionally andinconsistently by this scribe; cf., e.g., the person determinative or the legs determinative.

Line 4For xpr pay Dd pA r... [...] ‘Es geschah das, was der [...] gesagt hatte.’Read mdw=y Dd pA r &ms\ [...] ‘I spoke as follows: the boat [...]’The initial two words should rather be read straightforwardly as mdw=y. At the end of the line thetraces suggests that pA r &ms\, ‘the boat’, should be read. Compare the writing of rms in the Brooklynfragment, line 4.

Line 5For my in=w Imn-i.ir-ti-s bw-nA[y] ‘Möge man Amyrtaios hierher bringen!’Read my in=w Imn-i.ir-di.t-s DA[Dy ...] ‘Let Amyrtaios be brought. [...] ran off [...]’The editor felt uncomfortable with the reading Imn-i.ir-di.t-s because he could cite no other instanceof this name written with the divine determinative. However, it is in fact the vertically shaped formof the person determinative that is written here and not the divine determinative. Its shape is notablymore angular than that of the divine determinative, and the same shape of the determinative is alsoused for the names PAy-bs, @r-aw and &a-nA in this text. The reading of the rest of the name poses noproblem.

At the end of the line, the restoration DADy seems preferable to bw-nAy. In this case we would bedealing with a fixed set of common phrases in demotic narratives:• Someone asks for something to be brought (my in=w ...).• It is then said that the addressed party ‘ran off’ (DADy ...).• The affair is concluded by the object in question being brought (in ...).For examples cf., e.g., Chasheshonqy 3.19-21;13 Khamwase and Siosiris 2.33-3.1;14 and Contest forthe Benefice of Amun [Pap. Spiegelberg] 12.4-6.15 It may also be noted that there is no horizontal stro-ke over A as expected if it were part of the group nAy. For the orthography of DADA, see line 12.

Line 7For [...] pA(?) 30.200 n-im=w iw=w ip r pr-[aA ...]

‘[...] die(?) 30.200 von ihnen, die zu Pharao zählen [...]’Read [... r].xAa=f n-im (n) &nA\y=w ip r pr-aA [...]

‘[... which] he left there in their account for(?) pharaoh [...]’

12 Hoffmann, Ägypter und Amazonen, 40.13 Harry S. Smith, The Story of Onchsheshonqy, in: Serapis 6 (1980), 139. 152.14 Griffith, Stories of the High Priests of Memphis, 164–165.15 Wilhelm Spiegelberg, Der Sagenkreis des Königs Petubastis: Nach dem Strassburger demotischen Papyrus so-

wie den Wiener und Pariser Bruchstücken, Demotische Studien 3, Leipzig 1910, 26–27.

© A

kadem

ie Verlag

. This d

ocu

men

t is pro

tected b

y Germ

an co

pyrig

ht law

. You

may co

py an

d d

istribu

te this d

ocu

men

t for yo

ur p

erson

al use o

nly. O

ther u

se is on

ly allow

ed w

ith w

ritten p

ermissio

n b

y the co

pyrig

ht h

old

er.

341ADemotic Narrative in Berlin and Brooklyn concerning the Assyrian Invasion of Egypt

The characteristic writing of xAa in this hand is well-attested.16 The following group is not the prepositio-nal n-im=w, but the adverb n-im. The traces after n-im seem compatible only with the possessive nAy=w.The final r pr-aAmay be understood as ‘for pharaoh’ or a circumstantial clause ‘while pharaoh ...’.

Line 8For ir aw PA-i.ir-kpe ‘... Größe des (?) PA-i.ir-kpe’Read &@r\-aw &sA\ PA-i.ir-kpe ‘@r-aw son of PA-i.ir-kpe’The name @r-aw is written with the vertically shaped orthography of the person determinative forwhich see the comment on line 5. Within a literary context, the name @r-aw is also attested in theContest for Inaros’ Armor [Pap. Krall] 10.21 which is set in the same general period.17 That man is,however, described as the ‘son of Petesis’ and he is therefore unlikely to be related to the present cha-racter. There is a trace of the oblique stroke that represents sA before PA-i.ir-kpe.

Line 9For ... [...] pA ntr ‘... Gottes’Read &pA\ ntr &aA pA\y=y ntr ‘the great god, my god’The addition of the possessive ‘my god’ in reference to the specific deity to which an individual wasdevoted is common; cf., e.g., Contest for Inaros’Armor [Pap. Krall] 2.10, 8.3, 9.8.18

Line 10The traces at the beginning of the line would be compatible with n-im=f.

Line 12For nA rmt.w nAy=w iAby r-wn-nA.w wAH wr-rxy(?) r-r=w

‘Die Männer von der linken, die feindliche Zaubereien(?) gegen sie gelegt hatten’Read nA rmt.w-na-smH.w r.wn-nAw Hr pA &wrx\ r-r=w

‘the men of the left, who were in the court, [did such-and-such] against/to them’The signs after the relative preterit converter should be read as the preposition Hr followed by the ar-ticle pA rather than wAH which is written differently, cf. line 29 below. The fibres of the papyrus areslightly distorted after pA, but the reading of wrx is certain. Compare the writing in the Brooklyn frag-ment, line 2.

Line 14For nA rmt.w nAi=w-[{wnm-}]iAbi.w ‘Die Männer von der Linken’Read nA rmt.w-na-wnm.w ‘the men of the right’The text describes two groups of men as nA rmt.w-na-smH.w, ‘the men of the left ( )’ and nA rmt.w-na-wnm.w, ‘the men of the right ( )’. The editor emended all the latter occurrences and hencefailed to notice this distinction, but it is clearly shown by line 2 that the scribe uses these two ortho-

16 I owe the reading of xAa to Joachim Friedrich Quack.17 Friedhelm Hoffmann, Der Kampf um den Panzer des Inaros. Studien zum P. Krall und seiner Stellung innerhalb

des Inaros-Petubastis-Zyklus, Mitteilungen aus der Papyrussammlung der Österreichischen Nationalbibliothek(Papyrus Erzherzog Rainer), Neue Serie 26, Wien 1996, 237–238.

18 Hoffmann, Der Kampf um den Panzer des Inaros, 146–147, 194–195, 213–214.

© A

kadem

ie Verlag

. This d

ocu

men

t is pro

tected b

y Germ

an co

pyrig

ht law

. You

may co

py an

d d

istribu

te this d

ocu

men

t for yo

ur p

erson

al use o

nly. O

ther u

se is on

ly allow

ed w

ith w

ritten p

ermissio

n b

y the co

pyrig

ht h

old

er.

342 Kim Ryholt, Kopenhagen

graphies to write ‘left’ and ‘right’ respectively.19 The ‘men of the left’ are mentioned in lines 11, 12,15 and 42, while the ‘men of the right’ are mentioned in lines 14, 27, and 36.

Line 16For fy.v rmt r-Xn (r-)Hr [...], compare the passage fy rmt r-Xn r-Hr pAy=f iry n-im=w in the unpublishedInaros Epic. This translates ‘One man charged against his fellow among them’, i. e. they charged eachother.

Line 18For pH pAi ir wa rmt swrt n rmt iwnnw irm wa [rmt ...]

‘Zusammentreffen war es, was ein Diener, ein Mann aus Ionien (?), machte mit einem[Mann (?) ...]’

Read pH pAy-ir wa rmt-swrt n rmt-iwn irm wa [wx (?)]‘Arriving is that which a manager, acting as a courier, did together with a [letter (?)]’

The construction should rather be understood as a cleft sentence of the type discussed by Joachim F.Quack, ‘Die Konstruktion des Infinitivs in der Cleft Sentence’, RdÉ 42 (1991), pp. 189-207, with pAy-ir as the common writing of pA-i.ir.

I understand iwn as the word ‘journey’ and the compound rmt-iwn as ‘man of journeying, cou-rier’, a designation also attested in other texts; cf. discussion in Ryholt, Narrative Literature, pp. 55-56. With this interpretation, a courier arrives (pH) with a letter that is read aloud (aS), while pharaohlistened (sDm), and ‘its contents’ (X.v=w) are cited verbatim. It may be noted that a rmt-iwn similarlydelivers a letter in the story of the Contest for Inaros’Armor [Pap. Krall] 8.33.

The exact meaning of the title swrt remains elusive, but it seems to designate a type of managerrather than servant; cf. K. Ryholt, The Carlsberg Papyri 4: Story of Petese son of Petetum, CNI Pu-blications 23, Copenhagen, 1999, p. 32. In a few texts, the title is attached to temples or chapels anda single bilingual text renders it φροντιστής in Greek. More noteworthy is the fact that the title alsooccurs in a papyrus from the reign of Amasis which lists the personnel that participated in an expedi-tion to Nubia; cf. K.-Th. Zauzich, ‘Ein Zug nach Nubien unter Amasis’, Life in a Multi-Cultural So-ciety, SAOC 51, Chicago, 1992, p. 362. This attestation of the title in relation to a military expeditionprovides a nice parallel to the present narrative and it is more or less contemporary with its historicalsetting.

Restore perhaps irm wa [wx], ‘with a [letter]’, where the text breaks off. In two unpublished co-pies of the Contest for the Benefice of Amun and the Inaros Epic from the Tebtunis temple library, thepreposition irm is used in reference to messengers travelling ‘with’ a letter.

Line 19The editor read Imn-i.ir-ti-s sA PA-ti-[...]. However, the vertical stroke after the initial pA of the patro-nymic is a bit shorter than expected and the possibility therefore cannot be ruled out that we shouldread sA PA-&i\.[ir-kpe], i.e. ‘Amyrtaios son of PA-i.ir-kpe’. In this case Amytaios would be a brotherof @r-aw.

19 The present text is also discussed by Joachim F. Quack, Zur Lesung der demotischen Gruppe für “links”, forth-coming, who draws the same distinction between the two groups here under discussion.

© A

kadem

ie Verlag

. This d

ocu

men

t is pro

tected b

y Germ

an co

pyrig

ht law

. You

may co

py an

d d

istribu

te this d

ocu

men

t for yo

ur p

erson

al use o

nly. O

ther u

se is on

ly allow

ed w

ith w

ritten p

ermissio

n b

y the co

pyrig

ht h

old

er.

343ADemotic Narrative in Berlin and Brooklyn concerning the Assyrian Invasion of Egypt

Line 20The restoration xrw [bAk] by the editor is somewhat uncertain. The Inaros Epic preserves a fragmen-tary passage describing a similar episode. On the basis of the present text, that passage may be read[aS=w s r ...] sDm di[-s] X.v=f xrw pA mw irm tA sty [...], ‘[It was read aloud while ...] listened. Here areits contents: The voice of the water and the fire [...]’. The significance of the last phrase is not quiteclear to me, but it seems to be a metaphorical reference to matters that are contrasts by nature. At anyrate, it shows that an alternative to xrw bAk might be considered.

Line 21For [...] r PA-i.ir-kpe n 20.000 ..... sw ..... 10.000 sw arqi aA-pHv

‘gegen (?) PA-i.ir-kpe von 20.000 ..... Monatstag .... 10.000 (am) letzten Monatstag.Großer an Macht [...’

Read [... @r-aw] sA PA-i.ir-kpe n-m-bAH pAy=f Hry @r sA Ra aA-pHty ‘[@r-aA] son of PA-i.ir-kpe [...]before his lord, the Horus, the Son of Re, the Great of Strength’

For the restoration [@r-aw] sA PA-i.ir-kpe, see the note on line 8 where it is argued that PA-i.ir-kpe isa patronym rather than the name of one of the characters. The word Hry is slightly obscured by thedistorted fibres but quite certain. For n-m-bAH, which also occurs in the Brooklyn fragment and marksthe phonetic shift from m to n, compare the orthography n-m-sA (m-sA > Nsw) which is very commonin this hand. The ligature for pAy=f written is used again in line 41 of the present fragment.

The reading @r sA Ra is straight forward and requires no comment in itself, but it remains to beconsidered to whom it refers. A reference to Horus as the son of Re is somewhat unexpected and apersonal name *Harsire is otherwise unattested. Since the letter is delivered to pharaoh, read aloud tohim, and apparently also addressed to him, it seems to me most likely that we should understand @rsA Ra as a reference to the king as ‘Horus’ and ‘Son of Re’, the two traditional royal titles. To markthem as titles, I have added the definite article in the translation.

Line 23It may be noted that the title pA wr, ‘the prince’, which is here used in reference to king Esarhaddon,is written with a cartouche and a royal epithet anx wDA snb determinative, precisely like the royal titlepr-aA used in reference to the Egyptian king.

Line 24For pA nhwr r.tw pr-aA ww

‘Der Schrecken vor Pharaoh ist entfernt.’Read [...] pA nhwr r.tw pr-aA ir=w bAk

‘... the Fear whom pharaoh turned into vassals’.The word nhwr can hardly be used in its ordinary sense ‘fear’ since it is written with the toponymdeterminative in addition to the snake, and also because of the context. It is probably a qualificationof some ruler or territory or it might represent an unetymological writing. The reading of ir=w bAkis certain. The same phrase occurs in Petechons and Sarpot, where it has also been misinterpreted inboth editions, cf. Ryholt, ‘New Readings in the Story of Petechons and Sarpot’, forthcoming.

© A

kadem

ie Verlag

. This d

ocu

men

t is pro

tected b

y Germ

an co

pyrig

ht law

. You

may co

py an

d d

istribu

te this d

ocu

men

t for yo

ur p

erson

al use o

nly. O

ther u

se is on

ly allow

ed w

ith w

ritten p

ermissio

n b

y the co

pyrig

ht h

old

er.

344 Kim Ryholt, Kopenhagen

Line 27For nA rmt.w nAi=w-{wnm-}iAbi.w ‘Männern der {Rechten (und)} Linken’Read nA rmt.w-na-wnm.w ‘the men of the right’See comment on line 14.

Line 28For ir=w pA sbsy sA-nsw NA-kA.w PAi-bs irm nAy [...]

‘Man machte die Rüstung für den Königssohn Necho (und für) Pibesis und diese [...]’Read ir=w pA sbty (n) sA-nsw Na-kA PAy-bs irm nAy[=f rmt.w (?)]

‘One made the preparation for prince Necho Pibesis and his [men (?)]’The group read sbsy here and in line 41 surely represents little more than a variant orthographyof the common term sbty, ‘preparation’. It will hardly have been derived from sbSy, ‘Rüstung’, as sug-gested by the editor, since the phonetic shift s < S would be unexpected.

The final sign of the name Necho is rather the divine determinative than the plural sign. The na-me occurs in a slightly variant orthography in line 39 where the element kA is written with a differentgroup.

At the end of the line restore perhaps irm nAy[=f rmt.w], ‘and his men’.

Line 30For ‘dem Fruchtgarten von Tanis’Read ‘the fruit garden of Tana’&a-nA, which is written , is not otherwise attested as an orthography for the city of Tanis andthe determinative is not in fact the toponym, but the person determinative followed by the feminine-t. For this writing of the determinative, see the comment on line 5. What we have here is thereforethe common female personal name Tana and the passage offers no direct clue to the geographical set-ting of the episode.

Line 32I understand the group after in iw=y ir pA as (slightly restored). What is interpreted by theeditor as a second n with the bad-bird determinative below is rather the group under influence ofthe homonymous wordmn, ‘there is not’. Apart from the different explanation of the group, the editoris very likely correct in regarding it as a variant orthography of the euphemistic term ‘landing’ in thesense of ‘death’; cf. now Chicago Demotic Dictionary, letter m (13 July 2010), p. 97.

Line 33For in-iw-iw=k rx TAi=f r pA mA n-nti iw pr-aA n-im=f ti [...]

‘Wirst Du es vermögen, ihn zu dem Ort zu bringen, an dem Pharaoh ist? Gegeben hat [...]’Read in iw.iw=k rx TAi=f r pA mA n-nty-iw pr-aA PA-s-mtk [n-im=f]

‘Are you able to take him (or: it) to the place where pharaoh Psammetichus [is].’The group after pr-aA is not n-im=f which is shaped quite differently in this hand, sc. ; cf. lines 2and 10. What we have after the title of pharaoh is the royal name Psammetichus. The orthography isidentical to that used in the story of Amasis and the Sailor [Pap. Bibl. Nat. 215 vo.], lines 12, 14,20 and

20 Wilhelm Spiegelberg, Die sogenannte demotische Chronik des Pap. 215 der Bibliothèque Nationale zu Parisnebst den auf der Rückseite des Papyrus stehenden Texten, Demotische Studien 7, Leipzig 1914, 26–27.

© A

kadem

ie Verlag

. This d

ocu

men

t is pro

tected b

y Germ

an co

pyrig

ht law

. You

may co

py an

d d

istribu

te this d

ocu

men

t for yo

ur p

erson

al use o

nly. O

ther u

se is on

ly allow

ed w

ith w

ritten p

ermissio

n b

y the co

pyrig

ht h

old

er.

345ADemotic Narrative in Berlin and Brooklyn concerning the Assyrian Invasion of Egypt

in Jar Berlin 12345, line 16.21 It may be noted that the correct reading of the name was not noted inthe editions of the two latter texts; in the former story it is used twice, for both a priest and a pharaoh,while in the latter it is once in combination with a prenomen as PA-s-mtk NA-nfr-pA-ra, i.e. Psammeti-chus II Neferibre. 22• Pap. Berlin P. 15682, l. 33: PA-s-mtk (pharaoh)• Pap. Bibl. Nat. 215 vo., l. 12: PA-s-mtk (sailor)• Pap. Bibl. Nat. 215 vo., l. 14: PA-s-&mtk\ (pharaoh)• Jar Berlin 12345, l. 16: [PA-s]-mtk NA-nfr-pA-ra (pharaoh)For other more peculiar orthographies of the name, cf. M. Chauveau, ‘Le saut dans le temps d’undocument historique: des Ptolémées aux Saïtes’, La XXVIe dynastie: continuités et ruptures, edited byD. Devauchelle, Paris, 2011, p. 42.

Line 34The meaning of the two words xtrf and qHy, which are both written with the metal determinative, isunknown, but for the latter, cf. qH (Wb.V 66.15), and also the reduplicated verb and the nounderivative qHqH formed on the same stem (Wb. V 67.6-8, 67.9).

Line 35For Sn / nA Sa.v-Snw.w ‘Bäume’ / ‘der Baumfäller’Read xt / nA Sav-xv ‘wood’ / ‘the wood cutters’The reading xt (cf.Glossar, 370) for the group and the same element of the compound(slightly restored) seems preferable to Sn (cf. Glossar, 513), and I suspect that the examples of thepresent orthography read Sn in Glossar are misinterpreted. Compare also Late Egyptian Sadxt (Wb. IV 423.1). The two words Sav-xv evidently form a compound since the plural strokes are writ-ten after the second element rather than the first.

Line 36For nA rmt.w nAi=w-{wnm-}iAbi.w ‘Männer von der {Rechten} Linken’Read nA rmt.w-na-wnm.w ‘the men of the right’See comment on line 14.

Line 36For iw=y xpr ... [...] ‘Ich werde sein ... [...]’Read iw=y xpr Hr pA [...] ‘I will be on (or: in) the [...]’The preposition Hr and the divine article pA are clearly to be read at the end of the line, although theformer is slightly damaged. Compare the writing of Hr pA in line 12. The phrase may be understoodeither as the Third Future ‘I will be ...’ or a circumstantial present ‘while I am ...’.

21 Wilhelm Spiegelberg, Demotische Texte auf Krügen, Demotische Studien 5, Leipzig 1912, 16–17; re-editedby Philippe Collombert, Le Conte de l’Hirondelle et de la Mer, in: Kim Ryholt (ed.), Acts of the SeventhInternational Conference of Demotic Studies, Carsten Niebuhr Institute Publications 27, Copenhagen 2002,59–76.

22 The correct reading of the names is noted in Friedhelm Hoffmann & Joachim Friedrich Quack, Anthologie derdemotischen Literatur. Einführungen und Quellentexte zur Ägyptologie 4, Berlin 2007, 161, 347 n. f; JoachimFriedrich Quack, Einführung in die Literaturgeschichte III. Die demotische und gräko-ägyptische Literatur,Einführungen und Quellentexte zur Ägyptologie 3, zweite, veränderte Auflage, Münster 2009, 73, 74, 170.

© A

kadem

ie Verlag

. This d

ocu

men

t is pro

tected b

y Germ

an co

pyrig

ht law

. You

may co

py an

d d

istribu

te this d

ocu

men

t for yo

ur p

erson

al use o

nly. O

ther u

se is on

ly allow

ed w

ith w

ritten p

ermissio

n b

y the co

pyrig

ht h

old

er.

346 Kim Ryholt, Kopenhagen

Line 38For nsw ipy=w s ‘... Sohn (?)] (des ?) Königs. Man überdachte es’Read ipy.t-nsw ‘royal harem’The initial word reads ipy.t-nsw with nsw in honorific transposition. The element ipy.t is written withthe house and toponym determinatives followed by the feminine -t. The redundant combination of-y (phonetic writing) and -t (historical writing) to indicate the feminine gender is common in texts ofthe Roman period.

Line 39For [...] qny r nA.w nty iw=w mr Ni.t

‘[...] stärker als die, welche Neith lieben werden’Read [...] qny r Na-kA Mr-N.t

‘[...] stronger than (king) Necho Merneith’The reading suggested by the editor would require nA nty rather than na nty, i.e. the plural definitearticle rather than the plural filiation article. For the reading of the name Necho, compare the ortho-graphy in line 28 which is identical except for the different sign used to write the element kA. NechoMerneith is the name used to distinguish Necho I from his later name-sake in several demotic narra-tives; cf. discussion in K. Ryholt, ‘New Light on the Legendary King Nechepsos of Egypt’, JEA 97(2011), pp. 66-67. This interpretation also helps to explain the divine determinative which is not nor-mally used for the goddess Neith. It is, however, entirely appropriate for the royal name Mr-N.t andit may be from its use in this context that the scribe also writes the determinative for the element N.twhen used in direct reference to the goddess.

New translation

1 [...] he/his [...] at/to the camp [---2 [...] to the left and right of him. | [---3 [...] ... My great lord! [...] was [---4 [...] (toponym) | I said as follows: the boat [---5 [...] May Amyrtaios be brought. [...] ran off [---6 [...] pharaoh. Pharaoh said to him [---7 [... which] he left there in their account for(?) pharaoh [---8 [...] @r-aw son of PA-i.ir-kpe altogether. ... [---9 [...] the great god, my god. If ... ... ... [---10 [...] him/it. | Came the dawn of the following morning, [...] sat [---11 we will not do our utmost with the army of the men of the left ... [---12 the men of the left, who were in the court, at them. [...] ran off [---13 They clad themselves in their armor on every side. They came [---14 the men of the right. They brought their faces out of the destruction. [...] returned [---15 the men of the left. | Came the dawn of the following morning [---16 them. They clad themselves with their armor. Each man charged into [his fellow among them

(i. e. the two armies charged into each other) ---17 while he said: ‘Woe and misery of Neith! The Egyptian army [---18 their hearts. Arriving is that which a manager acting as a courier did with a [letter (?) ---19 I was among the managers who serves Amyrtaios son of ... [---

© A

kadem

ie Verlag

. This d

ocu

men

t is pro

tected b

y Germ

an co

pyrig

ht law

. You

may co

py an

d d

istribu

te this d

ocu

men

t for yo

ur p

erson

al use o

nly. O

ther u

se is on

ly allow

ed w

ith w

ritten p

ermissio

n b

y the co

pyrig

ht h

old

er.

347ADemotic Narrative in Berlin and Brooklyn concerning the Assyrian Invasion of Egypt

20 It (sc. a letter) was read aloud, while pharaoh listened. | Here is a copy thereof. | The voice [--- /--- @r-aw]

21 son of PA-i.ir-kpe before his lord, the Horus, the Son of Re, the Great of Strength [--- / --- My]22 great lord! May he celebrate innumerable jubilees! The time of hurrying up to Egypt [---23 prince Esarhaddon, son of Sennacherib. | ... [---24 the Fear whom pharaoh made into a vassal. | If it pleases [--- / --- he opened]25 his mouth to the ground in a great cry while he said: ... [---26 above him. He said: My great lord! Here is a ... [---27 bulls of the men of the right. | I let (?) Bêl rage [--- / --- May]28 the preparation of prince Necho Pibesis and his [men (?)] be made [---29 make/made camp on the eastern shore of the lake [---30 in the fruit garden of Tana with the army of [---31 sat at a feast, while his heart was very joyous. | The [---32 saying: ‘Woe of Neith! Will I die ... [---33 Will you be able to take him (or: it) to the place where pharaoh Psammetichus is? [--- / --- My]34 great [lord!] I have two xtrf n qHy here. If you give to me the ... [---35 wood. I will undertake the journeys of the wood cutters in [---36 come to the camp of the men of the right, I will be (or: while I am) in the [---37 counsel. Your considerations are good. | [---38 royal harem, while there is no abomination ... ... [---39 stronger than Necho Merneith. My great lord! ... [---40 the chief of the army is the one who let them rebel. | If ... [--- / --- Horus son of Isis and]41 son of Osiris, the great god. My pharaoh make his preparation [---42 army of the men of the left, while they sleep and while they are drunk [---

Discussion

Historical setting

In the original edition, the story is assumed to concern the Egypto-Assyrian conflict in the reign ofTaharka (c. 690-664 BC) and to provide an actual day-by-day account of the defeat of the invadingKing Esarhaddon (c. 681-669 BC) in 674 BC, as if it were a chronicle.23 This would render it a uniquehistorical narrative within an Egyptian context. With the new decipherment of the names of no lessthan two Egyptian rulers in the text, it is clear that the story actually takes place somewhat later. Theruling king is Psammetichus and because the text also mentions Necho Merneith, which refers to Ne-cho I (c. 670-664 BC), the former may be identified with his father Psammetichus I (c. 664-610 BC)rather than one of his later name-sakes.

Characters

Before turning to a discussion of the nature of the story, it may be useful to provide a list of the cha-racters mentioned in the extant fragments. These are:• King Psammetichus I (Berlin, line 33). That he is the ruling king emerges clearly from line 33, whe-

re there is a question about bringing someone or something to ‘the place where pharaoh Psammeti-chus is’. Further references to pharaoh, without mention of his identity, are therefore likely to refer

23 Zauzich, Serpot und Semiramis, 463–464.

© A

kadem

ie Verlag

. This d

ocu

men

t is pro

tected b

y Germ

an co

pyrig

ht law

. You

may co

py an

d d

istribu

te this d

ocu

men

t for yo

ur p

erson

al use o

nly. O

ther u

se is on

ly allow

ed w

ith w

ritten p

ermissio

n b

y the co

pyrig

ht h

old

er.

348 Kim Ryholt, Kopenhagen

to this king as well (Berlin, lines 6 bis, 7, 12, 20, 24, 41; Brooklyn, lines 1, 5, 8), and similarly sothe designation ‘the Horus, the Son of Re’ in the letter addressed to pharaoh (line 21).

• King Necho Merneith (Berlin, line 39), sc. the historical Necho I, the father of Psammetichus I.• The king’s son Necho Pibesis (Berlin, line 28). Since the story takes place in the reign of Psam-

metichus I, this cannot be Necho I as originally assumed. He may be identical with the futureNecho II, the son of Psammetichus I, but King Necho II is usually distinguish from his earliername-sake by the designation ‘Necho the Wise’ (Nechepsos) in the later literary tradition.24

• The Assyrian king Esarhaddon son of Sennacherib (Berlin, line 23).25• The men of the right (Berlin, lines 14, 27, 36). This seems to be an army which is loyal to pharaoh.• The men of the left (Berlin, lines 11, 12, 15, 42). This seems to be an army which rebels against

pharaoh.• @r-aw son of PA-i.ir-kpe (Berlin, lines 8, 20-21; Brooklyn, line 1). The activities of this character

are somehow related to Amyrtaios. The latter has a conversation with pharaoh where @r-aw ismentioned (line 8), and later a manager who servesAmyrtaios brings pharaoh a letter from @r-aw(lines 18ff).

• Amyrtaios son of ..... (Berlin, lines 5, 19; Brooklyn, lines 4, 6?). The name of his father is perhapsPA-i.ir-kpe, which would make him a brother of @r-aw, or alternatively PA-di-[...] (line 19). Hedeals directly with pharaoh (lines 5ff.) and he has a group of managers (swrt), one of whom deli-vers a letter to pharaoh (line 19).

• A chief of the army who causes someone to rebel (line 40). There is a lacunae before the title andit is possible that a name was provided. He could in principle be identical with @r-aw or Amyrta-ios.

• A unnamed manager (swrt) acting as a courier (line 18). This is probably a singular occurrenceof this character who is said to serve Amyrtaios.

• Awoman named Tana (line 30). She is mentioned only in the context of ‘the fruit garden of Tana’and conceivably plays no further role in the story.

The Story

The story evidently concerns some conflict involving the Egyptian king and his military. While theAssyrian king Esarhaddon is mentioned, there is no explicit reference to the Assyrians in the extantfragments and they do not seem to be part of the conflict at this point. Instead we find repeated refer-ences to the armies of ‘the men of the left’ and ‘the men of the right’ respectively. A passage in Hero-dotus 2.30, recently discussed by Joachim Quack, is crucial to the understanding of these designa-tions.26 Herodotus mentions an army which had deserted its post in the reign of Psammetichus I andleft for Ethiopia. This army is designated Asmach (άσμάχ) ‘which signifies, in our language, thosewho stand on the left hand of the king.’27 As pointed out by Quack,Asmach is clearly the Greek trans-literation of Egyptian smH and there can be little doubt that Herodotus is here referring to what in thepresent text is called ‘the army of the men of the left’.

24 Kim Ryholt, New Light on the Legendary King Nechepsos of Egypt, in: Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 97(2011), 61–71

25 For other attestations of this king in Egyptian narrative literature, see Ryholt, The Assyrian Invasion of Egyptin Egyptian Literary Tradition, 484–485.

26 Quack, in: Enchoria 32 (2010–11), 80–81.27 A. D. Godley, Herodotus I: Books I and II, Loeb Classical Library, London/Cambridge Mass. 1926, 308–309.

© A

kadem

ie Verlag

. This d

ocu

men

t is pro

tected b

y Germ

an co

pyrig

ht law

. You

may co

py an

d d

istribu

te this d

ocu

men

t for yo

ur p

erson

al use o

nly. O

ther u

se is on

ly allow

ed w

ith w

ritten p

ermissio

n b

y the co

pyrig

ht h

old

er.

349ADemotic Narrative in Berlin and Brooklyn concerning the Assyrian Invasion of Egypt

Now that it is clear that the present story is also set in the reign of Psammetichus I, an even closerrelation with Herodotus emerges. Both accounts take place in the reign of Psammetichus I and bothmention specifically that the army of the men of the left rebelled against the king. Accordingly, thereis some likelihood that these two sources refer to the same incident, whether or not it belongs to his-torical reality or was a literary invention. This is noteworthy since no less than six centuries separateHerodotus and our papyrus. Whether Herodotus’ account was based on an earlier copy or version ofthe present text is difficult to determine, owing to its poor state of preservation.

The possibility should further be considered that the story, at least in part, concerns the conflictrelating to the re-unification of Egypt in the early reign of Psammetichus I and the trauma of the civilwars. The fact that the text mentions ‘the Egyptian army’ does not necessarily imply that a foreignarmy similarly played a role in the extant episode. The stories of the Contest for the Benefice of Amunand the Contest for Inaros’Amor, which have a near-contemporary historical setting, similarly men-tion ‘the Egyptian army’, but both within the context of inner-Egyptian conflicts.28

The role of Esarhaddon remains uncertain. In terms of historical chronology, he died before theaccession of Psammetichus, but the late historical narratives are not entirely reliable in their historicaldetail; this is well illustrated by the story ofDjoser and Imhotep, where Djoser fights theAssyrians, orthe Inaros Epic, where the Assyrians and Persians are confused.29 For the same reason it remains un-clear whether Esarhaddon is portrayed as the rulingAssyrian king, or whether the story merely makesreference to his invasion of Egypt at some time in the past. It may be relevant to note that Necho I forhis part, as the predecessor of Psammetichus, is mentioned as a king of the (recent) past.

Lines 1–6: Amyrtaios is fetched

Going over the story line by line, it is possible to gain at least a tentative impression of its nature. Itmust, however, be kept in mind that less than half a column is preserved and that no more than 40-50% of its text is available to us.

Towards the beginning of the column, the king seems to hold an audience with his leaders stan-ding on his right and left according to the rules of court etiquette (line 2). Someone addresses pharaoh(line 3) and after some speech, of which only a few words are preserved, it is suggested that a certainAmyrtaios should be fetched (line 5). Someone runs off, findsAmyrtaios and presents him to pharaoh(lines 5–6).

Lines 6–10: Pharaoh talks with Amyrtaios

Pharaoh addresses Amyrtaios (line 6) and there is mention of someone leaving something in or as anaccount (line 7) and also of @r-aw son of PA-i.ir-kpe (line 8). Some of what is preserved in the lattertwo lines may be part of a reply by Amyrtaios.

28 Spiegelberg, Der Sagenkreis des Königs Petubastis; Hoffmann, Der Kampf um den Panzer des Inaros. Recenttranslations of the two stories may be found in Hoffmann & Quack, Anthologie der demotischen Literatur, 59–87, 88–107, and Damien Agut-Labordère & Michel Chauveau, Héros, magiciens et sages oubliés de l’Égypteancienne. Une anthologie de la littérature en égyptien ancienne, Paris 2011, 71–94, 95–132.

29 Kim Ryholt, The Life of Imhotep, in: Ghislaine Widmer & Didier Devauchelle (ed.), Actes du IXe CongrèsInternational des Études Démotiques, Bibliothèque d’étude 147, Cairo 2009, 305–315; Ryholt, The AssyrianInvasion of Egypt in Egyptian Literary Tradition, 492–495 (on the Inaros Epic). Cf. also Ryholt, King NechoI son of king Tefnakhte II, in: Frank Feder, Ludwig Morenz, & Günter Vittmann (ed.), Von Theben nach Giza.Festmiszellen für Stefan Grunert zum 65. Geburtstag, Göttinger Miszellen Beihefte 10, Göttingen 2011, 126–127.

© A

kadem

ie Verlag

. This d

ocu

men

t is pro

tected b

y Germ

an co

pyrig

ht law

. You

may co

py an

d d

istribu

te this d

ocu

men

t for yo

ur p

erson

al use o

nly. O

ther u

se is on

ly allow

ed w

ith w

ritten p

ermissio

n b

y the co

pyrig

ht h

old

er.

350 Kim Ryholt, Kopenhagen

Lines 10–15: A day of battleThe story now moves to the following morning (line 10) and this paragraph refers to both the menof the right and of the left. Someone, presumably representing the men of the right, states that theywill not ‘do their utmost’ with the army of ‘the men of the left’ (line 11). This may indicate a ploy orstrategy to conceal their real strength. Just possibly the reference to ‘the men of the left’ in connectionwith the royal court concerns messengers or ambassadors of theirs, again in connection with a ruse.Someone next prepares for battle (line 13), but already in the following line is it told that one of thetwo parties — or both — withdrew from the battle, ‘They brought their faces out of the destruction’,and apparently returned to their camps (line 14).

Lines 15–18: A day of battle, the king is distressed

The story once more moves to the following morning (line 15). Again the armies prepare for battleand immediately charge into combat (line 16). Someone soon cries out in complaint and mentions theEgyptian army (line 17). In view of the fact that the person swears by Neith and what happens next,this may well be Psammetichus I himself.

Lines 18–24: A courier brings a letter to pharaoh

In the middle of all this a courier suddenly arrives (line 18). He relates that he was among a group ofmanagers (swrt) who serves Amyrtaios (line 19). The courier brings a letter and since it is addressedto pharaoh and read aloud in his presence (line 20), it is clearly to his camp that the courier has ar-rived. This also fits the fact that the courier serves Amyrtaios who was brought before pharaoh twodays earlier.

The contents of the letter are fully cited. It is sent by @r-aw son of PA-i.ir-kpe and the king isgreeted as ‘his lord, the Horus, the Son of Re, the Great of Strength’. The polite greetings continuewith the more conventional ‘My great lord! May he celebrate innumerable jubilees.’ The actual mes-sage in the letter fills just two lines and apparently refers to two events; the time when Esarhaddonwent to Egypt (lines 22–23) and the fact that some ruler or territory was turned into vassals by theEgyptian king (line 24). Whether these events are recent or refer to a more remote past is not clear.The letter ends with a request, ‘If it pleases ...’, the nature of which is lost.

Lines 24–31: The king is distressed, then calmed and happy again

The contents of the letter apparently come as a shock to pharaoh and a stock literary phrase is usedto describe his reaction: ‘he opened his mouth to the ground in a great cry’ (lines 24-25).30 Someonesays something that involves reference to the ‘bulls of the men of the right’, i.e. to the strength ofthese men, apparently in an attempt to bolster pharaoh’s spirits. He further suggests that preparationsshould be made for the king’s son Necho Pibesis (line 28), and there is reference to making camp atthe eastern shore of a lake (line 29), as well as to ‘the fruit garden of Tana’ (line 30). It stands to reasonthat prince Necho is the son of Psammetichus I and he might be identical with the future Necho II.Ap-parently at the conclusion of this paragraph, someone ‘sat at a feast, while his heart was very joyous’.

30 Restore perhaps [tA wnw.t n sDm nAy md.w i.ir pr-aA wn=f] rA=f r pA itn n sgp aA, ‘[The moment when pharaohheard these things, he opened] his mouth to the ground in a great cry’. These are standard phrases.

© A

kadem

ie Verlag

. This d

ocu

men

t is pro

tected b

y Germ

an co

pyrig

ht law

. You

may co

py an

d d

istribu

te this d

ocu

men

t for yo

ur p

erson

al use o

nly. O

ther u

se is on

ly allow

ed w

ith w

ritten p

ermissio

n b

y the co

pyrig

ht h

old

er.

351ADemotic Narrative in Berlin and Brooklyn concerning the Assyrian Invasion of Egypt

Lines 31–36: Someone is distressedAlready at the beginning of the next paragraph, someone superior is once more distressed and swearsby Neith. He asks whether he will die (line 32), using the common euphemism ‘land’ which cor-responds to the English euphemism ‘pass away’. Since he proceeds to ask, after a lacuna, whethersomeone will be able to take some other person or thing ‘to the place where pharaoh Psammetichusis’, it is perhaps not the king himself who is distressed this time, although he might be referring tohimself in the third person.

Someone answers that he has two tools of some sort and asks to be given something in addition.He will then ‘undertake the journeys of the wood cutters’. This may well be a ploy to get incognitoaccess to ‘the camp of the men of the right’, apparently the army loyal to pharaoh, which would againindicate that the distressed person is not pharaoh.

The superior thanks the person for this advice, with the approving remark ‘Your considerationsare good.’

Lines 36–42

The rest of the text is even more difficult. There is mention of the royal harem, but it is not clear fromthe context what role it plays (line 38).

In the next line we find the tantalizing words ‘stronger than Necho Merneith’ (line 39). The lattername refers to Necho I, the father of Psammetichus I. This may be a reference to the fact that Nechowas actually captured by theAssyrians and brought to Nineve in chains. If that is the case, the absenceof the royal title before his name may be contextually motivated. At the same time it cannot be ruledout that a negation is missing and that the sense is the opposite, i. e. that someone was not strongerthan Necho I. The king did in fact return to Egypt and continue to rule, laying the foundations of theSaite Dynasty.

After a lacuna, it is stated through a cleft sentence that the chief of the army caused some groupof people to rebel (line 41). In the last two lines of the column, pharaoh is asked to make personalpreparations for some event and there is reference to the ‘army of the men of the left, while they sleepand while they are drunk’. This may well be advice to prepare for war and to attack the enemy armyin a situation where they are vulnerable. Accordingly the rebellious party would be the ‘army of themen of the left’. The disorderly state of the army, lying around drunken, is perhaps a result of the re-bellion. The notion of attacking an army in such a condition finds a noteworthy parallel in an accountby Josephus (Jewish Antiquities 6.362) that is contemporary with our papyrus:

‘So David made use of the man to guide him to the Amalekites, and came upon them lyingaround on the ground, some at their morning meal, others already drunken and relaxed withwine, regaling themselves with their spoils and booty. Falling suddenly upon them, he madea great slaughter of them, for, being unarmed and expecting no such thing but intent upondrinking and revelry, they were all an easy prey.’31

Relation to other known texts

It has not been possible to identify any direct parallels to the present text, but there are two very frag-mentary papyri from the Tebtunis temple library that may be relevant to mention, sc. Pap. Carlsberg

31 Henry St. John Thackeray & Ralph Marcus, Josephus V: Jewish Antiquities, Books V–VIII, Loeb Classical Li-brary, London/Cambridge Mass. 1934, 348–349.

© A

kadem

ie Verlag

. This d

ocu

men

t is pro

tected b

y Germ

an co

pyrig

ht law

. You

may co

py an

d d

istribu

te this d

ocu

men

t for yo

ur p

erson

al use o

nly. O

ther u

se is on

ly allow

ed w

ith w

ritten p

ermissio

n b

y the co

pyrig

ht h

old

er.

352 Kim Ryholt, Kopenhagen

421 and Pap. Carlsberg 701.32 The extant remains of the former mention Necho Merneith and a mannamed Amyrtaios, while the latter mentions a king who swears by Neith, as in the present story, aswell as a kalasiris or warrior named Amyrtaios and three men of the east. It is possible that either ofthese papyri preserves other parts of the narrative here edited, but since the nameAmyrtaios was verycommon and a whole range of stories are set in the Saite period, it is by no means inevitable.

Postscript

Since the present paper was completed, I have also had the opportunity to study the fragments storedin frames Pap. Berlin P. 23502, 23532, and 23533, which the original publication of Pap. Berlin P.15682 described as ‘weitere Fragmente von Erzählungen in einer sehr ähnlichen Handschrift (...), diesich jedoch nicht an den hier publizierten Text anschließen lassen’.33 The identification of a series ofkeywords in combination with the identical script makes it clear that most of these fragments — andperhaps all of them— do in fact belong to the same manuscript. Thus, for instance, 23502a mentionsAmyrtaios and ‘his boat’; 23502b mentions PA-i.ir-kpe, Amyrtaios, pharaoh, the men of the left, andthe men of the right; 23502c mentions PA-i.ir-kpe and Neith; 23532a mentions Esarhaddon and theAssyrians; and 23532b mentions once again the Assyrians.

The realization that these fragments belong together with Pap. Berlin P. 15682 and Pap. Brook-lyn 47.218.21-B is important since it helps us trace the modern history of the manuscript. It emergesfrom the museum records that the fragments stored in 23502 and 23532 derive from the collectionof Dr. Carl Reinhardt (1856-1903) and that the fragments were removed from Blechkiste XI, whilethe fragments in 23533 are said to derive from either Blechkiste XI or XX. In all likelihood the lat-ter fragments, as well as the main fragment Pap. Berlin P. 15682, similarly came from Dr. Reinhardt.The Brooklyn papyrus, in turn, derives from the collection of Charles Edwin Wilbour (1833-1896).We can therefore establish that the known fragments of the papyrus must have been acquired in thelate 19th century. Wilbour was in Egypt in 1880-96 and Reinhardt in 1885-88 and again in 1894-99.34

As for the provenance of the papyrus, both Reinhardt and Wilbour are known to have acquiredpapyri from Soknopaiou Nesos, but the hand is quite dissimilar to the characteristic script knownfrom other contemporary texts from that site.35 Hence this merely indicates that the papyrus was soldat the same time and through the same channels. This is not surprising since, as has already beennoted above, the script is almost certainly Fayumic. The papyrus may therefore be assumed to haveoriginated somewhere else in the region and the sale of papyri from this region is likely to have beendominated by a few major antiquities dealers according to the patterns of trade known from later on.36

Finally, the fact that the fragments of the manuscript were not sold as a single, closed lot opensup the possibility that further pieces may have been acquired by yet other parties and therefore mightbe lurking in some collection, awaiting identification.

32 Pap. Carlsberg 421 is edited in Ryholt, Narrative Literature from the Tebtunis Temple Library, 103–130, whilePap. Carlsberg 701 is unpublished.

33 Zauzich, Serpot und Semiramis, 452.34 For Carl Reinhardt, see Sven P. Vleeming, Papyrus Reinhardt. An Egyptian Land List from the Tenth Century

B.C., Hieratische Papyri aus den Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin 2, Berlin 1993, 2.35 Compare, e.g., Sandra Lippert & Maren Schentuleit, Quittungen, Demotische Dokumente aus Dime II, Wiesba-

den 2006; Lippert & Schentuleit, Urkunden, Demotische Dokumente aus Dime III, Wiesbaden 2010.36 On the Egyptian antiquities trade in general, cf. Fredrik Hagen & Kim Ryholt, Antiquities Trade in Egypt

1880’s–1930‘s: The H. O. Lange Papers, forthcoming.

© A

kadem

ie Verlag

. This d

ocu

men

t is pro

tected b

y Germ

an co

pyrig

ht law

. You

may co

py an

d d

istribu

te this d

ocu

men

t for yo

ur p

erson

al use o

nly. O

ther u

se is on

ly allow

ed w

ith w

ritten p

ermissio

n b

y the co

pyrig

ht h

old

er.

353ADemotic Narrative in Berlin and Brooklyn concerning the Assyrian Invasion of Egypt

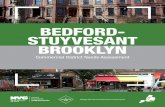

Tafel 1 Pap. Berlin P. 15682 + Pap. Brooklyn 47.218.21-B

Pap. Berlin P. 15682

Pap. Brooklyn 47.218.21-B

© A

kadem

ie Verlag

. This d

ocu

men

t is pro

tected b

y Germ

an co

pyrig

ht law

. You

may co

py an

d d

istribu

te this d

ocu

men

t for yo

ur p

erson

al use o

nly. O

ther u

se is on

ly allow

ed w

ith w

ritten p

ermissio

n b

y the co

pyrig

ht h

old

er.