Tokelau:

Transcript of Tokelau:

This article was downloaded by: [Case Western Reserve University]On: 04 December 2014, At: 06:50Publisher: RoutledgeInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registeredoffice: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

The Journal of Pacific HistoryPublication details, including instructions for authors andsubscription information:http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cjph20

Tokelau:Antony HooperPublished online: 19 Dec 2008.

To cite this article: Antony Hooper (2008) Tokelau:, The Journal of Pacific History, 43:3, 331-339,DOI: 10.1080/00223340802499625

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00223340802499625

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the“Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis,our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as tothe accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinionsand views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors,and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Contentshould not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sourcesof information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims,proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever orhowsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arisingout of the use of the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Anysubstantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing,systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms &Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

The Journal of Pacific History, Vol. 43, No. 3, December 2008

PACIFIC CURRENTS

Tokelau:

a Sort of ‘Self-governing’ Sort of ‘Colony’

The three small Polynesian atolls of Tokelau have seldom featured at all prominentlyin news of the Pacific region. They have been under New Zealand administrative controlfor the past 82 years and, for most of that time, social and economic change has beengradual, peaceable and (to the outside world) generally unremarkable. However, thepace of change accelerated markedly around 2000, when the islands declared theirintention to move toward self-government in free association with New Zealand. AUnited Nations (UN) referendum on the issue was held early in 2006, but failed to reachthe two-thirds majority required for its acceptance. A second referendum on the sameissue was held in October 2007, and it also failed. In UN terms, Tokelau thus remainsa non-self-governing territory, and the Administrator remains an official of the NewZealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade, based in Wellington.

That would all be straightforward enough if the Administrator’s powers had not allbeen delegated to Tokelau before the first referendum, in anticipation that thereferendum would succeed. They could now only be rescinded by an act of the NZparliament, or by regulations made by the Governor General. In the absence of somereally extraordinary happening that is perhaps unlikely. New Zealand has declared itscontinuing financial support for Tokelau and the continuation of its policy of ‘beingguided by the wishes of the Tokelau people’.

Nevertheless, the current situation is shot through with ambiguities. The islandscould, from one point of view, be described as ‘self-governing’. Indeed, in the run-up tothe first referendum, NZ officials put out press releases to the effect that Tokelau was‘already governing itself’ — the implication of course being that a ‘Yes’ vote in thereferendum would bring about no material changes in the lives and circumstances of thepeople. Now, Tokelau might indeed be governing itself, but because of the referendumresults, it is not formally ‘self-governing in free association with New Zealand’. And itcould hardly be said to be ‘autonomous’, as it is almost entirely dependent on foreign aid,mostly from New Zealand. Nor is it ‘independent’ in UN terms, as that was never one ofthe options put to the people in either of the referendums. None of this perhaps mattersvery much in the wider turmoils of the Pacific region. But it matters on the ground. Theinternal politics of the group are currently entangled in a number of divisive issues, andits political future remains somewhat uncertain.1

The notion of Tokelau becoming a self-governing state is a fairly long-standing one inNew Zealand diplomatic circles and in the UN Committee of 24. But it has always hadan air of unreality about it, especially since Tokelauans have always been equivocalabout making any change in their political status. The atolls have a total land area ofonly a little over 12 square kilometres and are away in the central Pacific about 500 km

1 My thanks to Tony Angelo, Judith Huntsman, Tony Johns, Ioane Teao, Iuta Tinielu and Neil Walter for

allowing me access to various records and for discussion of many issues.

ISSN 0022-3344 print; 1469-9605 online/08/030331–9; Taylor and Francis

� 2008 The Journal of Pacific History Inc.

DOI: 10.1080/00223340802499625

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Cas

e W

este

rn R

eser

ve U

nive

rsity

] at

06:

50 0

4 D

ecem

ber

2014

north of Samoa. They have no capital, no harbours and no airstrips. The administrativecentre is in Apia. The population is small and apparently declining, until it is now lessthan that of a reasonably sized high school. Among the non self-governing territories inthe Pacific, only Pitcairn is smaller. And, as many Tokelauans (especially those living inNew Zealand and so excluded from voting in the referendums) have pointed out, thegroup is too small, and still too poor, too dependent and lacking in the skills essential formanaging national and international affairs satisfactorily.

New Zealand has had administrative control of Tokelau since 1926, following anImperial proclamation which removed them from the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colonyand made them a responsibility of the Governor General of New Zealand — who in turndelegated his authority to the Administrator of Western Samoa, then a League of Nationsmandated territory. However, faced with shipping difficulties, administrative oversightfrom Western Samoa was irregular, limited to only one or two trips a year — justsufficient to pick up the copra and deliver trade goods. Education remained in the handsof the missions, and there was a skeleton medical service. Visits became even fewer duringthe depression years of the 1930s. In these circumstances, the atolls looked afterthemselves, consolidating their neo-traditional social orders based largely on kinship andlocal conventions of leadership, law and land tenure. There were no residents outsideadministrators. The islands were largely self-sufficient, orderly and peaceful. There wereno murders, no police and no jails.2

The war in the Pacific did not directly impinge on the atolls. After the war, with theformation of the UN in 1946, New Zealand control over Western Samoa was transformedfrom a League of Nations Mandate to the UN system of international trusteeship, with itsprovisions for orderly political advancement. At the same time, the administration ofTokelau was disentangled from that of Western Samoa and set on a different path,designed to link it more closely with New Zealand. The Tokelau Islands Act of 1948declared the group to be ‘part of New Zealand’ and, in 1949, Tokelauans became NZcitizens, free to move there if they wished. In administrative terms, Tokelau was thusjoined the Cook Islands and Niue as the third of New Zealand’s ‘Island Territories’.During the 1950s, improvements were made to education, medical services, commu-nications and infrastructure in the atolls. Then, in 1960, with the UN’s Declaration onthe Granting of Independence to Colonial Peoples and Counties and the establishment ofthe Committee of 24, New Zealand came under a definite obligation to offer a measureof self-determination to all its non-self-governing Island Territories.

New Zealand accepted these new responsibilities readily enough, and set in placeplans to establish internal self-government in the Cook Islands and Niue. No mention wasmade of Tokelau, as it was at that time considered to be too small for such innovations.Instead, the atolls were given the opportunity to choose whether they wished to join withWestern Samoa or the Cook Islands. Tokelau rejected these options, asking instead to beallowed to remain with New Zealand, and for assistance with emigration there to relievepopulation congestion. For a brief period, this seemed to provide an option fortransferring the entire population to New Zealand, but that was soon abandoned.Instead, New Zealand began a programme of assisted emigration in 1965.The scheme had its difficulties, but it continued until it was suspended in 1976, bywhich time 528 people had been resettled; others followed of their own accord,establishing ethnic communities now totalling over 6,000.

The Cook Islands became self-governing in 1965, and Niue in 1974. At this point,with no other ‘Island Territories’ remaining, the responsibility for Tokelau wastransferred to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. In spite of some discomfort with theirnew role as ‘colonial administrators’, the diplomats coped satisfactorily. The Committee

2 The most comprehensive description of the group is Judith Huntsman and Antony Hooper Tokelau: a

historical ethnography (Auckland and Honolulu 1996).

332 JOURNAL OF PACIFIC HISTORY

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Cas

e W

este

rn R

eser

ve U

nive

rsity

] at

06:

50 0

4 D

ecem

ber

2014

of 24 sent a Visiting Mission to Tokelau in 1976 to see the local conditions at first handand inquire about the people’s aspirations for the future. When asked specifically aboutthe idea of self-government they replied that they had no such aspirations. Instead, whatthey sought was further help with ‘development’. This set a clear agenda for NewZealand, which rapidly established a programme of ‘administrative decolonisation’.Suitably qualified Tokelauans were given real administrative responsibilities, and muchwas accomplished in education, medical services and improved infrastructure.

A Tokelau Public Service (TPS) had been established by statute in 1967, and this wasnow developed into a relatively elaborate bureaucratic structure along the lines of theNew Zealand Public Service. In the following years, the TPS generated a lot ofdiscontent in the atolls, since it brought into being a salaried elite, and it became quiteunclear whether authority lay with the traditional island councils or with the TPS officein Apia or even the far-off Public Service Commission in Wellington.3 This issue couldnot really be settled until there was some sort of effective political authority.

New Zealand’s programme of political development really only began in the 1990s,following very much along the same lines that were followed in the Cook Islands andNiue.4 Since the 1970s, matters of national import had been discussed at annual andsemi-annual gatherings known as General Fono, attended by the three Faipule (theelected leaders of each atoll) together with a few delegates, officials from the Tokelauoffice in Apia and the Administrator, a Foreign Affairs official based in Wellington.Finance and other matters were discussed and resolutions were passed, but the GeneralFono had no statutory authority to ensure that the resolutions were in fact carried out.To correct this situation, the three Faipule were constituted as a ‘Council of Faipule’ in1993, and charged with carrying out policy at times when the Fono was not in session.In 1994, the Administrator delegated his executive powers to the General Fono (andsubsidiarily to the Council, which in law has circumscribed administrative powers) witheach Faipule assuming quasi-ministerial functions and with a new position of Ulu oTokelau or ‘Head of Tokelau’ rotated among them on an annual basis. Finally, in 1996the NZ Parliament created a new power for the General Fono (with a power ofdisallowance by the Administrator) which empowered it to make rules ‘for the peace,order and good government’ of Tokelau. Other administrative innovations were tied tothese political changes.

As late as 1993 Tokelau leaders were still maintaining that they had no wish to changethe nature of the Tokelau–NZ relationship, in spite of the UN’s ‘Decade ofDecolonisation’ (due to conclude in 2000). Nevertheless, there were changes in the air.With the devolution of the Administrator’s executive powers in 1994, the new Council ofFaipule was able, for the first time, to speak with a national voice, and when a UNVisiting Mission was in the atolls in July, it was presented with an 11-page ‘SolemnDeclaration on the Future Status of Tokelau’ which stated that discussions on an act ofself-determination were now on the agenda, with a strong preference for free associationwith New Zealand. These intentions were strongly supported and encouraged by the NZAdministrator and, once legislative power had been granted to the General Fono, therewas scope for some serious discussions and concrete planning. In the late 1990s, there wasa lot of thought and discussion in the atolls about what needed to be done before therewas any definite move to self-government.

3 These issues are described more fully in two papers by Antony Hooper, ‘Aid and dependency in smallPacific territory’, Anthropology Department Working Paper no. 62 (Auckland 1982) and ‘The MIRAB transition in

Fakaofo, Tokelau’, Pacific Viewpoint 34:2 (1993), 241–64.4 Judith Huntsman and Kelihiano Kalolo, The Future of Tokelau: decolonising agendas 1975–2006 (Auckland

2007) is an authoritative study of New Zealand policy in Tokelau, based on archival sources of the NZ Ministry

of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

TOKELAU 333

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Cas

e W

este

rn R

eser

ve U

nive

rsity

] at

06:

50 0

4 D

ecem

ber

2014

Out of this there came an initiative called the ‘Modern House of Tokelau’, whichinvolved two major changes to the system already in place. First, the transfer of controlover the TPS from the NZ State Services Commission to a Tokelau authority; andsecondly, the establishment of the three village councils as the basis and source ofgovernment — a move that was seen as both culturally appropriate and built onestablished practices. With the ground plan approved by the General Fono in 1999, theModern House became a much more serious proposition. It became a comprehensive andvery well-funded official NZ Aid Project, locked into the procedures of the NZ OverseasDevelopment Agency and the obfuscating jargon of Public Service managerialism. Therewere four main elements of the project: ‘Governance’, ‘Capacity-Building’, ‘SustainableDevelopment’ and ‘Friends of Tokelau’.

‘Governance’ and ‘Capacity Development’ were the main concerns. These were termsthat Foreign Affairs and the aid bureaucrats were familiar with. ‘Development’,‘sustainable’ or otherwise, went by the board. During the years between 2001 and 2005,the islands were awash with outside consultants. As one senior Tokelau public servantremarked at the time, ‘Tokelau is the most consulted place on earth’.5

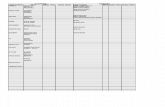

By the end of 2001, each of the islands had been through workshops devoted toManagement Training (led by NZ public sector management consultants), FinancialManagement (led by an official from the NZ Audit Department) and Policy TrainingAnalysis (led by analysts from the NZ Department of Labour). Along with theseactivities, there were audits and reviews of Education, Health, Telecommunications,Finances and Information Technology. Administrative tasks and responsibilities weredivided between two levels: the national level (the General Fono and the Council ofFaipule) taking care of the national budget and financial management, internationalrelations, currency, rule-making, decolonisation, communications, shipping and generalpolicy, leaving the village councils with responsibility for health and education services,public works, police and conflict resolution. The General Fono adopted TokelauEmployment Rules and appointed three Commissioners, one from each atoll, who werebrought to Wellington for briefings from university academics, the NZ State ServicesCommission, the Audit Department and the NZ public sector training organisation.

But that was by no means all. In 2003, a retired New Zealand public servant and aTokelauan finance officer did another round of consultations to determine the provisionof social services. At the local level, this involved the appointment from the TPS of villagesecretaries and managers, each with a small staff. Village council members were grantedannual honoraria of NZ$7,000, and remuneration rates were established for otherpositions, ranging from Faipule (NZ$15,000–17,000) down to ‘General Village Workers’on an hourly rate of $NZ2.35 an hour. The old Public Service manual was extensivelyrevised and expanded to cover all the details of appointments, discipline, leave, transfers,allowances, ‘difficult conditions’ and so forth. At the national level, the Council ofFaipule was provided with a manual of proper procedures and the national office wasstrengthened by the addition of Communication and Human Resources departments.

Other important issues were dealt with, and mainly resolved, during 2003 and 2004.The Tokelau Employment Commission was abolished, mainly because the threeappointed Commissioners had proved themselves to be not at all inclined to follow theideals of impartiality held by the NZ Public Service Commission. With the advice ofProfessor Tony Angelo of Victoria University’s Law School work was begun on aconstitution, which was later to provide some of the foundation for a document on the‘Principles of Partnership between New Zealand and Tokelau’ and the later draft treatybetween the two countries. The Council of Faipule was augmented by the addition of

5 The details are described more fully in Antony Hooper, ‘Against the wind: Tokelau 2001–2006’, The

Journal of Pacific Studies, 29:2 (November 2006), 157–94.

334 JOURNAL OF PACIFIC HISTORY

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Cas

e W

este

rn R

eser

ve U

nive

rsity

] at

06:

50 0

4 D

ecem

ber

2014

another elected official from each atoll, bringing the total membership to six, and wasrenamed the Council for Ongoing Government.

In June 2004, the Administrator withdrew his previous delegation to the GeneralFono (and Council) and replaced it with a delegation to each of the three villagecouncils, which in turn devolved their authority over matters best handled at the nationallevel to the General Fono and the Council for Ongoing Government. While thisdevolution of authority to the village councils might have given the appearance of areturn to a more village-oriented, more Tokelauan ways of doing things, that was not thecase in practice. Paradoxically, what it did was to both decentralise and centralise thesystem. Political authority might have been passed to the village councils, but at the sametime the councils were obliged to follow the guidelines and set procedures of the newlyappointed TPS council office managers. The key to acceptance of all this was money.Virtually every villager was now on the payroll as a government employee. Financial aidincreased rapidly. For the five years up to 2003, New Zealand’s budgetary support wasfixed at around NZ$4.5 million. By the year 2005–06 this had been increased to NZ$9.73million, supplemented by various items of ‘project aid’ amounting to a further NZ$2million. It now stands at some NZ$45 million for the three-year period ending in 2009.

With all this done, the stage was set for the first referendum, which was held inFebruary 2006. It involved a single proposition: ‘That Tokelau become a self-governingstate in free association with New Zealand on the basis of the Constitution and as in thedraft Treaty notified to Tokelau’, with the voters being asked to either agree with theproposal or reject it. The number of registered voters was 615 and, of these, 584 voted.Three votes were invalid, making the total number of valid votes 581. Of this total,349 (approximately 60%) voted ‘Yes’, while 232 rejected the proposal. The proposal thusfailed to reach the two-thirds necessary for success. Undeterred by this setback, Tokelaudecided to hold another referendum on exactly the same proposition. Strenuous measureswere taken to enrol all those who were eligible and a second referendum was eventuallyheld in October 2007. Again, the proposal was defeated, although by the much smallermargin of only 2%. At this point, it was decided to let the matter rest, at least for a while.New Zealand assured Tokelau that aid and cooperation would simply continue as before,and at a meeting in February 2008 the leaders of both countries agreed on the need tofocus on capacity-building and infrastructure development — more particularly theschools, hospitals and transport. They also agreed that, while work on self-determinationmight continue, it would be several years before the issue would be raised again.

The failure of the two referendums caused some dismay among the considerable bodyof local and visiting officials when the results were announced,6 and was made all themore acute by there being no obvious single reason why the proposal was rejected. Someblame was attached to the influence of Tokelau migrants in New Zealand, who had notbeen eligible to vote. This disenfranchisement had outraged many of them, who saw it asan insult to their standing as Tokelauans, poor recompense for all the support they hadalways given to relatives back home and a potential threat to their customary land rights.They had voiced their opinions freely in the thrice-weekly Tokelauan radio talk-backsessions originating from Wellington, casting many doubts on the political system sohastily put in place. They had some justification for this. Members of the Council ofFaipule, and later the Council for Ongoing Government, had been making numerousvisits to all New Zealand migrant communities as well as to Australia and Hawaii.

6 An elegant and perceptive description of the first referendum is by Ian Parker in the New Yorker of 1 May2006. Other, more pedestrian accounts appeared in the Dominion Post and the New Zealand Herald. An excellent

account of reasons for the failure of the first referendum is Tessa Buchanan, ‘Decolonisation of Tokelau: why

was the proposal to become self-governing unsuccessful in the 2006 referendum? M.Phil. thesis in DevelopmentStudies, Massey University (Palmerston North 2007). I also published two OpEd pieces in the Dominion Post

issues of 4 October and 31 October 2007.

TOKELAU 335

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Cas

e W

este

rn R

eser

ve U

nive

rsity

] at

06:

50 0

4 D

ecem

ber

2014

These visits were ostensibly for ‘consultations’, but whenever faced with searchingquestions the visitors either evaded the issues or filibustered. The migrants were wellaware of what had been going on. They knew that the move toward self-government didnot arise from any deep-seated popular impulse to be rid of New Zealand control, muchless from any ‘struggle for freedom’. It was the creature of bureaucrats, designed to boostthe aspirations of Tokelau politicians, free New Zealand from the taint of being somehowa ‘colonial power’ and prop up the reputation of the virtually moribund Committee of24. The goal was never ‘development’ in any sense of that term, but simply to create aplausible governmental structure, capable of at least the appearance of autonomy.

During 2007, a group of Wellington Tokelauans took their concerns about all this toa Parliamentary Select Committee dealing with NZ–Pacific relations, submitting paperswhich criticised many aspects of the political structure that had been so hastily put inplace — that it was too ‘top down’ and lacking in both transparency and accountability.The Committee gave fair and open consideration of these issues but, in the end, thesubmissions gained virtually no traction in either Parliament or the news media.

Tokelau ‘Development’?

In the early 1980s, Tokelau was one of the five small Pacific countries included in adetailed and influential study on ‘New Zealand and its Small Island Neighbours’7 byGeoff Bertram, an economist, and Ray Watters, a geographer. One of their most lastingand influential conceptual innovations was MIRAB, an acronym denoting four separateelements — migration, remittances, aid and bureaucracy. According to the model, allthese elements were closely interrelated and had become the driving force of the politicaleconomies of the islands in the region. Migration led to the loss of productive workers andtheir integration into metropolitan countries such as New Zealand. Their remittances ledto the creation of ‘dual economies’, with the islands representing the ‘traditional’ sectors.Aid, as it steadily increased, crowded out domestic savings and investment, anddrastically undercut productive effort. It had the nature of rent income, which had theunderlying purpose of ‘strategic denial’ and of linking the islands closely with NewZealand. Finally, bureaucracy: it necessarily increased as the different island groupsapproached independence or self-government, giving the public service power andprestige and creating new dimensions of social stratification.8

The MIRAB model has a clear relevance to the course of change in Tokelau. AsBertram and Watters saw it, Tokelau began its transition from a ‘traditional, subsistence-oriented’ society in the 1960s, when migration to New Zealand began, aid increased andattention began to be paid to administrative matters. By the 1980s, the Tokelau economywas essentially an aid-driven one, dominated by NZ budgetary and project assistance.Copra production virtually ceased. The formation and growth of the TPS was leading tocorrosive conflicts between the public service and traditional authorities. In 1996, theAdministrator’s annual report drew attention to the fact that ‘while Tokelau presents animage of a traditional society’ the shift had been made from a self-sufficient economy ‘toone that is cash-based and dependent upon imported goods and modern conveniences’.The process accelerated with the marked increase in both aid and bureaucracy broughtabout by the prospect of self-government, and can be seen as an important underlyingfactor in the failure of the referendums.

Comparisons with Niue, another of New Zealand’s ‘Island Territories’, which optedfor self-government in 1974, suggest some further dimensions of the Tokelau experience.

7 Institute of Policy Studies, Victoria University of Wellington, 1984.8 This summary is based on Ray Watters, ‘Mirab societies and bureaucratic elites’, in Antony Hooper et al.

(eds), Class and Culture in the South Pacific (Auckland and Suva 1987), 32–54.

336 JOURNAL OF PACIFIC HISTORY

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Cas

e W

este

rn R

eser

ve U

nive

rsity

] at

06:

50 0

4 D

ecem

ber

2014

Long before the issue of decolonisation came on the UN agenda in the 1960s, Niue hadhad three generations of colonial administration and institutions. There had beenresident New Zealand administrators and a cadre of public servants, many of whom wereseconded from New Zealand. There was also a legislative body, albeit with limitedpowers. In these circumstances, the move to self-government was relatively easy —though slow. Tokelau, by contrast, was always administered with a very light hand.There was never a resident New Zealand administrator, and an effective local publicservice did not really come into being until the 1980s. In short, Tokelau was prompted tomove very quickly if it hoped to ever achieve self-government. Nevertheless, there aremany parallels between the experience of the two countries.

As Niue moved toward self-government, New Zealand aid to the island increaseddramatically, along with substantial increases in the administrative bureaucracy. Ingeneral, those who gained salaried employment in the new order stayed. Those whomissed out simply migrated to New Zealand. The population fell dramatically from apeak of about 3,000 down to the present level of 1,200 or so. An unfortunate consequenceof this has been the failure of development projects on the island. Numerous enterpriseshave been started, only to collapse after a few years, and there are now significantdivisions of outlook and loyalties between the emigrants and those at home.

Both of these changes, population loss and the lack of economic enterprise, have alsobeen clearly evident in Tokelau. Given the small numbers involved and the mobility ofthe people, even the exact size of the population at any one time is difficult to fix. Inrecent censuses there have been not only differences between the de jure and de factocounts, but also differences in the way these two terms have been defined. The mosttelling figures come from a comparison between the numbers of ‘usual residents’ presentand enumerated on the atolls. In the 2001 census, there were 1,420. In 2006, this hadfallen to 1,074. Economic enterprise has been completely ignored. ‘SustainableDevelopment’ was put forward as one of the elements making up the ‘Modern House’project, but then nobody could come up with workable projects, much less get themgoing. Brief Small Business Management courses were held in the atolls in 2001, and in2002 a rather nebulous ‘strategic plan’ was devised with the help of a New Zealandconsultant economist. This, however, was only a public service planning exercise, with nohard estimate of costs. (In fact, money was hardly even mentioned.) Fishing wasdiscussed in some detail, and it was agreed that some sort of joint venture with Tokelauownership and control was a commendable goal, and it was duly made the leadingnational development priority. Nothing concrete has so far emerged.

The lack of interest in economic development is somewhat surprising given thefindings of a 1998 survey done by a NZ economist, a Samoan development consultantand a New Zealand-based Tokelau public servant. The survey found considerableinterest in the topic among village people, particularly women, and explored in somedetail a number of small to medium-sized enterprises that held possibilities foremployment and income generation. The survey also criticised what the governmentwas calling ‘infrastructure programmes’ and the effect that these were having on theprospects for economic development. The infrastructure programmes referred to were allthose dealing with ‘improvements to lifestyle’ — electricity, telephones, washingmachines, freezers, houses of imported materials, video games, television and so forth— which were being rapidly accumulated through government wages and salaries. Theseprogrammes in fact only increased rather than decreased Tokelau’s reliance on aid.

There remains a prospect that economic development will receive renewed attention.Fishing for the Pagopago tuna canneries remains promising, perhaps through using thelarge alia catamarans supplied to each atoll by the Forum Fisheries Agency, and the(largely empty) fish freezers. Coconuts are Tokelau’s other main resource, and they havelain a metre or more deep on the ground outside the villages, virtually unused since thecessation of copra production in the 1980s. While they may eventually serve to increase

TOKELAU 337

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Cas

e W

este

rn R

eser

ve U

nive

rsity

] at

06:

50 0

4 D

ecem

ber

2014

the fertility of the thin coralline soils, they also have the potential for the local productionof oil to fuel the electricity generators, freezers and outboard engines. The techniques fordoing this are already developed in other parts of the Pacific. Small-scale tourism isanother prospect, especially if, as promised by New Zealand, the shipping servicebetween the atolls and Samoa is improved. The advantage of such local enterprise is notonly the income gained but the fact they use local resources, under the control of villagesand large kin-based groups, and could provide meaningful employment for thoseyounger men and women who do not have salaried government positions and who onlyhave the alternatives of aid financed make-work projects on a pittance — or emigration.

Alternative Scenarios

The UN General Assembly’s 1960 Declaration on Colonialism (Resolution 1514)proclaimed that ‘all peoples have an inalienable right to complete freedom, the exerciseof the sovereignty and the integrity of their national territory’. Resolution 1541 thendeclared the obligation of colonial administering powers to account annually for theirstewardship until the territories attained ‘a full measure of self-government’. It also laiddown the principle that ‘A non self-governing territory can be said to have reached a fullmeasure of self-government by (a) emergence as a sovereign independent State, (b) freeassociation with an independent State, or (c) integration with an independent State’.From the beginning, New Zealand has complied assiduously with these requirements inrelation to its three ‘Island Territories’. However, as Bertram and Watters have pointedout, in dealing with the Cook Islands and Niue, New Zealand (probably from the best ofmotives) actively promoted the alternative of self-government in free association asagainst Independence or Integration. It also actively promoted this alternative forTokelau, with the result that neither of the referendums of 2006 and 2007 offered thealternatives of Independence or Integration.

Independence would have been patently absurd, but since the failure of the tworeferendums, the alternative of Integration has come up for serious consideration amongTokelauans in New Zealand. A paper by Professor Tony Angelo,9 Tokelau’s legaladviser, sets out many of the relevant issues. It considers the five South Pacific examplesof Niue, Tokelau, Norfolk Island, the Chatham Islands and the Cocos (Keeling) Islands.There are also other relevant examples which might be drawn on — Rapanui or EasterIsland, American Samoa or the surprisingly apposite example of NZ Maori iwicorporations. Angelo’s exposition is comprehensive and detailed. Besides the complicatedissues of constitutional law, he pays particular attention to matters of the place of‘Tradition’ in self-government — which are of special interest to Tokelauans. Angelo’sconcluding statement is also relevant:

Ultimately it is important to the integrity of the process that all the United Nations’choices be voted on by the populace. The populace should, in terms of the GeneralAssembly resolutions, have the opportunity to express a view on each of the optionsas they have been specifically identified in relation to the factors significant to thefuture of the self-determining territory.

The relevant point here is that the Tokelau ‘populace’ as a category in and of itself,separate from the island councils or the General Fono, has never had the opportunity tovote on either of the alternatives of Independence or Integration.

9 Tony Angelo, ‘To be or not to be . . . integrated, that is the problem of islands’, Revue Juridique Polynesienne,numero hors serie, 2 (2002), 87–108. Available http://www.upf.pf/IMG/pdf/01_sommaire.pdf (accessed 15

September 2008).

338 JOURNAL OF PACIFIC HISTORY

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Cas

e W

este

rn R

eser

ve U

nive

rsity

] at

06:

50 0

4 D

ecem

ber

2014

New Zealand Tokelauans doubtless hold widely differing opinions on these matters.But what many of them seek is informed and open discussion of the possibilities for thefuture — an initiative which appears to be being ignored by both the New Zealandofficials and the Tokelau government.

The present rather ambiguous relationship between Tokelau and New Zealand mightbe described as a variety of the status quo, which Angelo considers as a fourth alternativeto the three prescribed by the UN, and examines as another form of Integration. Tomany people, this would seem to be an ideal arrangement. It is, however, one that is notlikely to last. Last June the Administrator of Tokelau and the current Ulu or ‘Head ofTokelau’ spoke before the Committee of 24 in New York. The Administrator emphasisedNew Zealand’s acceptance of the referendum results and stressed New Zealand’s ongoingcommitment to its policy of being ‘guided by the wishes of the Tokelau people’. The Ulu,however, had a rather more sanguine view, stating that ‘Tokelau will not rest on thisissue of self-government following the two Referenda attempts’ and added, ‘As aTokelauan leader, I find it hard to close my eyes at night knowing that a decision of myelders on the future of Tokelau is still pending’. He then concluded his speech with adeclaration that ‘Tokelau will not give up the challenge and aspirations of its people to beself determined’. The Ulu was of course quite within his rights in expressing viewsdifferent from those of the Administrator. But whether these views were shared by all thepolitical leaders is another question. The Faipule of another atoll, also a member ofTokelau’s Council for Ongoing Government, was certainly taken aback by the Ulu’sstatement and let it be widely known that this was the first he had heard of this as beingTokelau’s considered position. Surprise proclamations by paramount political leaders ofcourse occur in even the largest and most developed national governments, but areparticularly disturbing in a small place like Tokelau, with its traditional commitment toconsensus decisions. In this regard it is to be hoped that there is general agreement on anextended pause to allow for matters to be settled. Tokelau, it appears, still has someway to go.

ANTONY HOOPER

TOKELAU 339

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Cas

e W

este

rn R

eser

ve U

nive

rsity

] at

06:

50 0

4 D

ecem

ber

2014