33qs

-

Upload

ujangketul62 -

Category

Documents

-

view

235 -

download

0

Transcript of 33qs

-

8/8/2019 33qs

1/7

Viewpoints

Improving the interface between primary and

secondary care: a statement from the EuropeanWorking Party on Quality in Family Practice(EQuiP)

O J Kvamme, F Olesen, M Samuelsson

AbstractA group from the European Working Partyon Quality in Family Practice (EQuiP),working with over 20 European colleges ofprimary care, has assessed what, in their

view, is needed to improve the quality ofcare at the interface between general prac-tice and specialists. Experiences and ideasfrom a wide range of people were gatheredthrough focused group discussions. Fromthese it was clear that, for real improve-ment at the interface of care, changes areneeded in the system of care and in theways that doctors view their roles and theirperformance. All providers of care need to

be able to see the care system from thepatients perspective if they are to helptheir patients make sense of and benefitfrom an increasingly complex system. Thispaper outlines the EQuiP recommenda-tions on how cooperation between general

practitioners and specialists might be im-proved. This includes strategic perspec-tives and both targets for improvement andmethods for teaching, training and devel-opment that are all independent of countryand health care system. The 10 targets fordevelopment identified by the group are:leadership, initial shared care approaches,task division, mutual guidelines, patientperspective, informatics, education, team

building, quality monitoring systems, andcost eVectiveness. Working towards thesetargets could provide an eVective approachto improving the cooperation between theinterfaces of care. Getting eVective leader-

ship is a necessary first step as implemen-tation of such a strategy will involvesignificant change. Responsibility lies pri-marily with the medical profession.(Quality in Health Care 2001;10:3339)

Keywords: quality improvement; primary health care;specialist health care

IntroductionAs modern healthcare systems become morecomplicated and more people need coordi-nated care from both sides of the primary/secondary interface, good communication be-tween the sectors becomes a crucial factor in

the delivery of good quality health care.However,the very complexity of health systemsoften mitigates against eVective communica-tion between the sectors. Improving the qualityof cooperation, both between sectors and

between professional groups, has not so farbeen a high priority in any of the Europeanhealthcare systems.

Much of the poor quality care can be linkedto problems that arise at the interfaces withinthe healthcare systems. Many patients feel theyare left in limbo when moving from one partof the system to another.14 Each part of thesystem tends to focus on its own tasks andresources and not on the system as a wholethat is, the system actually experienced bypatientsso the task of improving the qualityof interaction, cooperation, and communica-tion across the interfaces is not seen as any onegroups particular responsibility. Despite sig-

nificant diV

erences in their organisation,European health systems face similar prob-lems with the cooperation between primaryand secondary care. The solutions may also besimilar.

General practitioners (GPs) and specialistshave diVerent roles and may often see problemsfrom diVerent perspectives: In general practice,

patients stay and diseases come and go. In

hospitals,diseases stay and patients come and go.5

The diVerent perspectives and cultures andworking conditions that exist within the medi-cal profession reflect the wide range of medical,psychological, and social problems of thepatients cared for by each group. Working inseparate medical realities may diminish under-standing and even respect for the concerns ofothers. Patients need the variety of expertiseand technical competence. However, littleeVort has been devoted to bringing profes-sional groups together to enable them tounderstand their roles and to make them feeltheir work is complementary with that of otherswithin a single healthcare system.6 The pres-sure on doctors in all branches of medicine torespond to technological advances in their ownspecialties and to changes in patients expecta-tions diminishes opportunities to look beyondtheir separate worlds.

Quality in Health Care 2001;10:3339 33

Department ofGeneral Practice,

University of Oslo, P OBox 24, N-5484Sabovik, Norway

O J Kvamme, generalpractitioner

The Research Unit forGeneral Practice,Vennelyst Boulevard 6,

DK-8000 Aarhus C,

DenmarkF Olesen, professor

Department ofGeneral Practice,University of Caen, 11Rue Montebello, 30 100

Cherbourg, FranceM Samuelsson, general

practitioner

Correspondence to:Dr O J [email protected]

Accepted 18 December 2000

www.qualityhealthcare.com

-

8/8/2019 33qs

2/7

Shared care is one approach to improvingcare at the interface by minimising theapparent fragmentation of services.7 There isnow a trend towards working in teams to solvecomplex technical or bio-psychosocial prob-

lems. The transfer of tasks between specialistsand GPs is a natural and continuous processsteered by technology, cost, and the needs ofproviders and patients.

Healthcare systems are examples of compe-tence systems where the most important per-ceived asset is the ability and drive to createnew knowledge. This is then transformed intoeVective interventions and disseminatedthroughout the system. However, the system isnot uniform and there are large and significantvariations in the quality of health care. Thesystem does not function as a whole. Everyorganisation within the healthcare systemneeds to monitor, supervise, and improve thequality of structures, processes, and outcomes.

In addition, both patients and society have aright to expect that there is a mechanism forquality of care to be looked at across the systemas a whole and that someone is responsible forcoordinating care processes across boundaries.This includes logistics, communication, anddissemination of information. Focusing onimproving the functioning of the system as awhole may help to achieve the goal shared bymany health systems to provide seamless care.It may also go some way to raising the overallquality of clinical care and improving patientsatisfaction.8

Finding ways of improving the quality of careat the primary/secondary care interface is an

important objective of the European WorkingParty on Quality in Family Practice (EQuiP).Twice a year a working group meets to discussstrategies for improving care at the interface bycollating ideas, activities, and experiences froma wide range of sources including over 20European national colleges of primary care.For the last two years this group has exploredthe quality of care at the interface from fourperspectives: (1) the system as a whole; (2) thedelivery of good quality medical care; (3) theproviders viewpoint; and (4) the patientsviewpoint (table 1). Much of the informationfor this has been gained from focused group

discussions. From this the working group hasderived strategic targets and recommendationsfor quality improvement at the interfacebetween primary and secondary care thatshould have relevance in European healthcare

systems.

Perspectives of the quality of care at theprimary/secondary care interfaceSYSTEM PERSPECTIVE

The demand for access to health technology isgrowing. A system approach to quality impliesthat we should understand and discuss divisionof tasks across boundaries within the system.Specialist time should, of course,be assigned tohighly specialised duties, but the growingdemand for specialised medical technologyalso requires that waiting times are acceptablein relation to need and that we also minimisethat is, do not use technological interventions

inappropriatelysocietys expenditure onhealthcare technology.9 If weview the system asa whole it is possible to see that changes in onepart of the system can aVect the patient andprovider in another. It is our contention that atleast some of the waste in resources might beavoided if care across the primary/secondaryinterface was improved through better commu-nication and coordination.

PERSPECTIVE OF MEDICAL QUALITY

Every patient has the right to a discussion andinterpretation of his or her symptoms within aholistic framework where all relevant biologi-cal, psychological, and social aspects of health

can be considered. Patients also have the rightto informed, up to date discussion about mod-ern choices for investigation and interventionfor any symptom.10 If we want to attain thesetwo goals we need to make the best use of thespecialism of family medicine/general practicecare and all other medical specialties. Toachieve this there has to be commitment tocooperation and understanding. Thealternativewhich is no longer acceptableisfragmented and uncoordinated care. This isnot only wasteful of resources but also placespatients at the risk of poly-investigations, poly-interventions, and poly-pharmacy which are

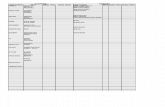

Table 1 Perspectives of quality at the interface between GPs and specialists, with examples of tasks and actions to increase the quality of the interface

Perspective Task Action

System perspective Meeting demands for access to care Task divisionImprove quality of primary care

Keeping down expenditures Control of access to secondary care sectorLogisticsCommunicationInformation systems

Perspective of medical quality Combining holistic and high technology approach Mutual guidelinesAvoid iatrogenic risks, poly-investigation and poly-treatment Family medicine approachImproving episodes of care Clinical audit

Patient perspective Coordinating chains of care Measure patients needs, pr iorities and evaluationsAudit/benchmarkingLogistics

Meeting patents rights New lawsPublic informationDialogue

Provider perspective Making providers more satisfied Working conditionsCollaborative conditionsPrevent and handle conflicts

Reducing fears and insecurity EducationDialogueNetworks

34 Kvamme, Olesen, Samuelsson

www.qualityhealthcare.com

-

8/8/2019 33qs

3/7

inevitably associated with a disjointed ap-proach to care. All patients should be guaran-teed access to a primary care physician appro-priately skilled in diagnostics, treatment, andcare who also refers appropriately those whoneed specialist attention.

PATIENT PERSPECTIVE

Patients expect a coordinated chain of investi-

gation, treatment, and follow up. We need tounderstand better patients views, expecta-tions, and experiences of care within the system.The European Task Force on Quality in Gen-eral Practice (EUROPEP) has developed aninstrument validated to measure patientsevaluations of quality in general practice.11

Benchmarking between hospitals has beenpractised for many years and includes meas-ures of patient perspectives.12 Patients arebecoming increasingly knowledgeable and haveaccess to much information about health carefrom many sources including the media andthe internet. Moreover, the rights of patientsare becoming secured in statutory frame-

works.13

Patients needs and expectations for caremay clash, producing an expectation gap,but this gap can be narrowed or closed by pro-viding appropriate and timely information andby maintaining dialogue between the health-care professions and the public and patientsabout their needs and the way in which the sys-tem works.14 The gap can also be narrowed bygood professional cooperation at the interfacebetween primary and secondary care. Goodquality care always includes the appropriate useof biomedical skills and health technologytogether with the ability to help patients tocope with the fears and expectations of care.

However, one practitioner may not possess allthe necessary skills.

PROVIDER PERSPECTIVE

Satisfied workers provide good quality care anddissatisfied workers deliver care of a poorerquality.15 16 There needs to be capacity withinthe healthcare system to prevent and to settleconflicts between diVerent specialties and pro-fessions to enable good working relationsacross all boundaries. Any competition be-tween GPs and specialists should give way toan understanding of complementarity of func-tion and of skills.

The increase in litigation in health care and

the fear of law suits, exposure in the media, orpenalties from oYcial bodies may aVectdoctors attitudes to clinical interventions.17

Such fears may lead to defensive medicineresulting in iatrogenic problems for patients, anincreased workload and reduction in job satis-faction for providers, and a waste of resourcesfor the system. A defensive approach dimin-ishes equity of access to care and may reduce itsquality. Continuous education and local net-works can be used to make doctors feel moresecure in their work, and could contribute toreducing defensive actions.

Targets for quality improvement at theinterface between GPs and specialistsBuilding on experiences and ideas from theperspectives chosen, the group identified 10strategic targets for quality improvement at theinterface between GPs and specialists that areuniversal to European healthcare systems.These targets are presented in box 1 andspecific actions to each target are shown intable 2.

DEVELOP LEADERSHIP WITH A DEFINED

RESPONSIBILITY FOR IMPROVING THE INTERFACE

For all healthcare systems the development ofleadership is an important target for qualityimprovement at the primary/secondary careinterface. This should involve regional admin-istrators, local authorities, and healthcare pro-fessionals. Leaders need both to build eVectiveteams and to delegate power and responsibili-ties if they are to promote really eVective qual-ity development. To improve the quality of careat the interface between primary and second-ary care they must ensure that the job descrip-tion of all providers includes consideration ofhow a professional cooperates with others,including those working in other sectors.

Facilitation of discussions on agreement

between sectors and professions is the respon-sibility of leaders. These discussion shouldaddress incentives, barriers, strengths andweaknesses, and opportunities and threats toproviding a good quality service. There shouldbe incentives to encourage eYcient and appro-priate distribution of tasks and functions.Guidelinesowned by all who use themare alikely consequence of such discussions.

Doctors must accept some limitations totheir autonomy and work with their leaders. Allhealthcare professionals should learn aboutleadership. Professional leaders who have togain consensus and encourage the system to

+ Develop leadership with a defined re-sponsibility for improving the interface

+ Develop a shared care approach forpatients treated in both primary and sec-ondary care

+ Create consensus on explicit task divisionand job sharing

+ Develop guidelines that describe qualityproblems at the interface and seek

solutions to such problems+ Develop an interface that contains the

patient perspective+ Develop systems for appropriate infor-

mation exchange to and from generalpractice care

+ Reinforce interface improvementthrough education

+ Facilitate team building across the inter-face

+ Establish quality monitoring systemswhich focus on quality at the interface

+ Establish a broad understanding of theneed for cost eVective use of the interface

Box 1 Ten targets for quality improvement at the interface

between general practice/family medicine and specialistcare.

Improving the interface between primary and secondary care 35

www.qualityhealthcare.com

-

8/8/2019 33qs

4/7

work as a whole are part of a modern healthservice. They should be willing to communi-cate outside their clinical practice with, forexample, other leaders, politicians and econo-mists, and to enter into a wider debate aboutways of improving the quality of care through-out the system.

DEVELOP A SHARED CARE APPROACH FOR

PATIENTS TREATED IN BOTH PRIMARY AND

SECONDARY CARE

For shared care to be implemented the barriersbetween diVerent parts of the healthcaresystem must go. Accomplishing this willdepend on stimulating eVective cooperationacross interfaces and on the development oflocal management structures designed toencourage rather than impede the process ofcare across the boundaries. Care needs to beseen from the patients perspective and man-aged, for example, by the development ofguidelines which include processes that matchthe patientsperspective and descriptions of thedistribution of tasks between primary and sec-ondary care.

An important precondition to implementingeVective shared care is that all those involvedcooperate and have shared goals that areexplicit. The creation of comprehensive guide-lines and the development of logistics forincreasing patient and public access to infor-mation may increase the rate of acceptance ofshared care and help to initiate processesinstrumental in achieving it. Providers andmanagers leading change should communicatewith patients and their representatives and alsowith politicians. Improving the quality of thesystem of care needs to be a common aimunderstood by all who use, work in, or

influence care across the interface between pri-mary and secondary care.

CREATE CONSENSUS ON EXPLICIT TASK DIVISION

AND JOB SHARING

Distribution of tasks between specialists andGPs should not imply that all technicalproblems are for the specialist and the rest forthe GP. GPs work within an expanded biologi-cal, psychological, and social model. While

much of their work integrates the relevantaspects of patients reactions, coping strategies,empowerment strategies, and social context,parts of their work are also simply technical.Treatment of a clinical problem should be atthe optimal level of carefor the patient andfor the systemand this is often in primarycare.

Some countries are still struggling to definethe identity and content of general practicewithin their healthcare systems. DiYculties areencountered with drawing the lines betweenprimary and secondary care in general, andbetween GPs and specialists in particular. Insome countries the lack of professional identity

of GPs makes it diY

cult to agree upon taskdivision and shared care. These diYculties willonly be overcome with eVective medicalleadership.

Discussions about the content of general andspecialist practice should be based on nationalneeds and provision but, in all systems, itshould be guided by the aims of creatingequity, accessibility, and cost eVective care.Again, eVective medical leadership will be nec-essary to facilitate discussions to define theroles and functions. Better cooperation is likelyto be accompanied by a change in attitude frommine and your patients or tasks to ours.

Table 2 Actions to improve quality related to each of the EQuiP targets

Target Action

Leadership Train professionals in leadershipStimulate shared quality improvement processesDefine job descriptions clearlyFacilitate clinical guidelines across the interfaceFacilitate guidelines for cooperationFacilitate consensus discussions

Shared care approach Stimulate communication across the interfaceInvolve local leadership in quality improvementAudit care across the interface

Create dialogue with patientsConsensus on task division Establish discussion groups with GPs, specialists and leadersStrengthen the professional identity of GPsBase solutions on needs and resources in each country

Guidelines Local GPs and specialists establi sh l ocal guidelines tog et herGuidelines must include consensus on cooperation between GPs and specialistsPatient perspective to be included in guidelines

Pat ien ts Au di t p at ien t j ou rne ys a cr os s i nt er fa ces a nd t hr ou gh t he h ea lt h c ar e s ys temInclude patients in auditMonitor patient expectations and evaluation of care by validated methods

Infor mation Electronic p at ient recor ds , guidelines and recommendationsElectronic communication and transfer of information across the interfacePublic information about access, processes, and outcomes

Education B asic medical educatio n to include cour ses in quality improvementSpecialist vocational training in general practice care sector

Joint CME courses for specialists and GPsTeam building Teams defined by tasks and circumstances

Interface teams for specific groups of patient, e.g. palliation, rehabilitation of strokepatients, diabetic care

Monitoring quality in clinical work Audit, benchmarking, patient surveysMonitor outcomes and processes

Use indicators selected in guidelinesCost eVectiveness Is a result of QI, not a prime targetSelect indicators that cover both primary and secondary care

CME = continuing medical education; QI = quality improvement.

36 Kvamme, Olesen, Samuelsson

www.qualityhealthcare.com

-

8/8/2019 33qs

5/7

DEVELOP GUIDELINES THAT DESCRIBE QUALITY

PROBLEMS AT THE INTERFACE AND SEEK

SOLUTIONS OF SUCH PROBLEMS

Guidelines should be based on up to dateinformation and set within national and localpossibilities, cultures, and traditions. Theyshould address the use of appropriate technol-ogy, cost eVective care, and actions that ensureequity and accessibility with the maximum ofpatient and provider satisfaction. Centrally

developed national clinical guidelines, built onevidence based medicine, are comprehensiveand resource demanding. Guidelines need tobe adapted to the local context and reflect theavailable human, structural, and economicresources. They should be developed from amultidisciplinary point of view and shouldinclude task distribution and act as anexchange of information about care at theprimary/secondary interface. Guidelinesshould include intended indicators of the qual-ity of the care. Leaders should use the groupsthat develop and monitor guidelines to helpfoster better work across the primary/secondary interface, as GPs and specialists in

these groups may already have developed posi-tive working cooperative relationships.

DEVELOP AN INTERFACE THAT CONTAINS THE

PATIENT PERSPECTIVE

The patient should experience a seamlesshealthcare system and, as far as possible, conti-nuity of care. We must focus organisation ofcare around an understanding of patient flowand patient journeys1 and make more use oflogistics to improve the quality of the patientsexperience across the system.

Patients or their representatives should beincluded in planning and auditing shared careon an equal basis with professionals and man-agers to ensure that their needs are considered.

Patients views should be included duringguideline development and their representa-tives may be members of guideline groups.Professionals and their leaders have an obliga-tion not only to take account of the viewsexpressed by patients and their representatives,but also to stimulate and encourage patients toexpress their opinions. The inclusion ofpatients views could lead to improved adher-ence to care plans and a better understandingof equity which might help to get medical pri-orities right.

DEVELOP SYSTEMS FOR APPROPRIATE

INFORMATION EXCHANGE TO AND FROM GENERAL

PRACTICE

Information about health care comes frommany sources. Enabling as many people aspossible to have easy access to informationabout health and health care is an importantpriority. The only exception to this is, ofcourse, the case based information aboutindividual care. Information that should beavailable includes disease based information(clinical guidelines), educational infor-mation to the public (for example, abouthealthy eating and healthy lifestyles), andquality information about practices and hos-pitals (availability, service, outcomes). All such

information should meet standards of accu-racy, timeliness, availability, and clarity. Get-ting it out in a format that meets the needs ofproviders and the public will require the use ofmodern informatics, but many health servicesremain woefully behind in the developmentand implementation of information technol-ogy. Models for sharing information within thecontext of genuine eVective formats need to bedesigned and adapted to local conditions, andthe input of both GPs and hospital specialists isneeded. The potential of the internet andintranet facilities as sources of information andmeans of communication is enormous. Thedevelopment of informatics should be a highpriority for research and development.

REINFORCE INTERFACE IMPROVEMENT THROUGH

EDUCATION

The competence and skills necessary for clini-cal practice are learnt in basic educationprogrammes and should be reinforced anddeveloped through continuing medical educa-tion (CME). Interestingly, as far as we have

been able to determine, basic medical educa-tion programmes do not include any training inquality improvement. This may go some way toexplaining the diYculties of sustaining coordi-nated care. Vocational training, programmesfor CME and, in particular, programmes forcontinuous professional development (CPD)could be used as the focus for introducingpractitioners to the theory and for training inthe skills needed for quality improvement.Redesigning CME and CPD to reflect a shifttowards more shared care will take eVort andwill certainly involve the creation of jointprogrammes by the diVerent specialties.

More fundamentally, the educational system

should encourage the development of coopera-tion skills within basic medical education,training in a culture of mutual respect forshared care thinking, task distribution, andrespect of patients expectations of high qualityseamless care. All postgraduate programmesshould include time in both general practiceand specialist practice. This demands morebalanced curricula that widen the perspectiveof participants so that all have some under-standing of biological,psychological, and socialperspectives and an appreciation of concernsrelevant to the world of high technology inter-ventions.

Specialist training schemes should encour-age development of insight into the concerns ofa range of other specialties. Doctors undergo-ing specialist training should experience work-ing across the interfaces. Currently, specialistsspend little or no time in family medicine dur-ing their training, although GPs are extensivelytrained in hospitals. Specialists should betrained in the patterns of diseases, signs, andsymptoms within the primary healthcare sys-tem as well as in those presenting to specialistpractice. All trainees should have appropriatetraining and insight into possible organisationalproblems at the primary/secondary care inter-face from the perspectives of both patients and

Improving the interface between primary and secondary care 37

www.qualityhealthcare.com

-

8/8/2019 33qs

6/7

providers. The lack of balance in current edu-cational systems limits the understanding ofcare at the interface.

FACILITATE TEAM BUILDING ACROSS THE

INTERFACE

Functioning, eVective, and coherent teams donot just happen. They require work, butthere is a large literature on team working andteam building that is easily available. Profes-

sionals need to draw on this when setting upteams to deliver shared care training pro-grammes for quality team work. Teamsshould review and evaluate the quality of theirwork and change their practice when indicated.New innovations in health care and thedevelopment of current techniques means that,with time, tasks will change or will be shiftedbetween professionals within a team. Forinstance, registered nurses now perform tasksthat previously were strictly the responsibilitiesof doctors. Rehabilitation programmes extendacross the interface between hospital andprimary care and involve several professionalgroups. Thus, new teams are formed by tasks

and by circumstances. While team building andcooperation are essential for the functioning ofa seamless system of care, patients also ask forpersonal care and continuity of care. Wellfunctioning teams that serve the system mustalso ensure a maximum of personal care.

ESTABLISH QUALITY MONITORING SYSTEMS

WHICH FOCUS ON QUALITY OF THE INTERFACE

Quality of care may be evaluated in terms ofprocess and of outcomes. Both need to bemeasured for care that crosses the interface.Developing indicators that measure the qualityof cooperation and communication at theinterface of care is an important area ofresearch.18 The gap between patients expecta-

tions of care and the care that they actuallyreceive is a possible indicator or proxy for thequality of care at the interface. It is a centralelement of cooperation, it is measurablethrough patients and professionals evalua-tions, and is universal with respect to diVerenthealthcare systems. Other indicators that couldbe used include measures of the continuity ofcare, of coordination of care processes, and thequality and consistency of the informationgiven to patients. Research is needed to definethe most appropriate indicators of the qualityof care. Leaders of improvement in care shouldbe responsible for including eVective systemsfor the quality of care as part of any change

process.

ESTABLISH A BROAD UNDERSTANDING AT THE

INTERFACES OF CARE OF THE NEED FOR COST

EFFECTIVENESS

In societies where there is a large gap betweenthe resources available and the sophisticationof technological possibilities, a drive to costeVectiveness may help to achieve an equitabledistribution of healthcare services. Concentrat-ing on cost eVective interventions will improvethe likelihood of providing equal and suYcientaccess for all citizens with equal needs. Ensur-ing cost eVectiveness of working processes is a

major element of any eVort to improve thequality of care at the interface. Qualityimprovement may be considered an investmentthat leads over time to more cost eVective andeYcient health care.19

An important and probably cost eVectiveoutcome of improving care at the interfacewould be to increase the frequency at whichpatients receive the right care (and nothingmore) at the right level, at the first try. This

would minimise work and costs. Better infor-mation and coordination at the interfacebetween primary and secondary care arenecessary prerequisites to achieving this goaland, importantly, all those working in thesystem will need to understand the systemfrom the perspectives of others.

ConclusionsAn action plan with 10 targets for improvingthe quality of care across the primary/secondary care interface has been set out.Actions necessary for achieving each of the 10targets are given in table 2. The work requiredin diVerent countries will be based on national

needs, priorities, and resources. The sugges-tions are not in any way mandatory, but are setto stimulate discussion about the quality ofcare across the interface between GPs and spe-cialists. It is not within the scope of this articleto deliver detailed plans for quality improve-ment within a system because such actionsmust be developed and performed by thoseworking in the system.

It is the purpose of EQuiP to encourageprofessional organisations and leaders ofhealthcare systems throughout Europe todiscuss these targets and to adapt the principlesto their national setting. Whilst national plansfor action will diVer, EQuiP wants to encour-age leaders to use specified indicators within

quality improvement and medical performanceassessments that allow benchmarking andcomparisons of progress between centres.

The group recommends that particularattention is paid to the following three areaswhen implementing a strategy for qualityimprovement across the primary/secondarycare interface:+ Improvement in leadership is probably the most

important task for the implementation ofeVective shared care. It is the responsibility ofboth clinicians and managers to developleaders capable of leading their colleagues towork in a way that promotes qualityimprovement.

+

Bringing GPs and specialists together anddeveloping personal and group relations througheducation and processes of task sharing is a

powerful instrument of change. The Danishmodel for GPs as advisors in hospitals is amultipotential method of promoting co-operation between GPs and specialists. GPsacting as facilitators of cooperation mayassist the creation of shared care, the initia-tion and promotion of clinical guidelines forshared care, and the formation of new infor-mation channels across the interfaces.6

+ Bridging the expectation gap by empowermentof patients can improve the experiences of

38 Kvamme, Olesen, Samuelsson

www.qualityhealthcare.com

-

8/8/2019 33qs

7/7

patients and professionals. Patients will sharetheir views and may carry their part of thecommon responsibilities to improve qualityof the interface. It is the responsibility of thepatients, when given the opportunity, toexpress their expectations and experiencesto providers and leaders of health care.Political initiatives and better cooperationbetween professionals, politicians, andhealthcare leaders may be needed to change

the culture of health care to achieve this.

Working towards the 10 targets set out byEQuiP should direct the attention of leaderswithin the medical profession to theimportance of making sure that the healthcaresystem works as a whole and that care for indi-vidual patients does not fall down because ofpoor coordination and cooperation at theinterfaces. By doing so, we should achieve asituation where the health system is redesignedto enable care to be delivered by doctors com-mitted to quality improvement across thewhole service, cooperating to provide care thatis perceived by patients as seamless.17

This paper is written on behalf of the EQuiP working group oninterface problems in health care. The members of the workinggroup are: Vivian Alles (Estonia), Michael Boland (Ireland),Poul Brix Jensen (Denmark), Hans Joachim Fuchs (Austria),Gunnar Gudmundsson (Iceland), Odd Jarle Kvamme (Nor-way), Frede Olesen (Denmark), Jose M Bueno Ortiz (Spain),Leif Persson (Sweden), Marianne Samuelsson (France), PerrtiSoveri (Finland), and Tomasz Tomasik (Poland).

1 Mainz J. Problem identification and quality assessment in healthcare: theory, methods and results (Danish). Kbenhavn:Munksgaard, 1995.

2 Roland M, ed. R&D priorities in relation to the interfacebetween primary and secondary care. Report to the CentralResearch and Development Committee. Leicester: Depart-ment of Health, 1995.

3 Dahler-Eriksen K,Lassen JF,Olesen F, et al. Clinical guide-lines across sectors: an example of a co-operating healthcare system (Danish). Ugeskrift Lger 1998;35:50214.

4 Preston C, Cheater F, Baker R, et al. Left in limbo: patientsviews on care processes across the primary/secondaryinterface. Quality in Health Care 1999;8:1621.

5 Heath I.Commentary: the perils of checklist medicine. BMJ1995;311:373.

6 Olesen F. General practitioners as advisors and co-ordinators in hospitals. Quality in Health Care 1998;7:427.

7 vretveit J.Integrated quality development in public health care.Continuing education and quality improvement. Oslo: TheNorwegian Medical Association, 1999.

8 Berwick D. Medical associations: guilds or leaders? BMJ1997;314:1564.

9 Olesen F, Fleming D. Patient registration and controlledaccess to secondary care. Eur J Gen Pract1998;4:813.

10 Olesen F, Mainz J. Research, technology assessment andquality assurance. Eur J Gen Pract 1996;2:1625.

11 Grol R, Wensing M, Mainz J, et al. Patients priorities withrespect to general practice care: an international compari-son. European Task Force on Patient Evaluations ofGeneral Practice. Family Pract 1999;16:411.

12 Kopp VJ. Preoperative preparation. Value, perspective, andpractice in patient care. Anesthesiol Clin North Am 2000;18:55174.

13 NHS Management Executive. The patients charter andprimary health care. London: Department of Health, 1992.

14 Smith JA, Scammon DL, Beck SL. Using patient focusgroups for new patient services.Jt Comm J Quality Improve-ment 1995;21:2231.

15 Clampitt P. Employee perceptions of the relationshipbetween communication and productivity.J Business Comm1999;30:528.

16 Albrow M, Sira I, Studio OR. Do organisations havefeelings? Organisational Studies 1992;13:31329.

17 Dickson G. Principles of risk management. Quality in HealthCare 1995;4:759.

18 Lawrence M, Olesen F. Indicators of quality in health care.Eur J Gen Pract 1997;3:1038.

19 Hampson JP, Roberts RI, Morgan DA. Shared care:a reviewof the literature. Family Pract 1996;13:26479.

w w w . q u a l i t y h e a l t h c a r e . c o m

L i n k t o M e d l i n e f r o m t h e h o m e p a g e a n d g e t s t r a i g h t i n t o t h e N a t i o n a l L i b r a r y o f M e d i c i n e ' s

p r e m i e r b i b l i o g r a p h i c d a t a b a s e . M e d l i n e a l l o w s y o u t o s e a r c h a c r o s s 9 m i l l i o n r e c o r d s o f b i b l i o g r a p h i c

c i t a t i o n s a n d a u t h o r a b s t r a c t s f r o m a p p r o x i m a t e l y 3 , 9 0 0 c u r r e n t b i o m e d i c a l j o u r n a l s .

M e d l i n e

D i r e c t A c c e s s t o M e d l i n e

Improving the interface between primary and secondary care 39

www.qualityhealthcare.com