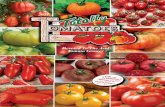

You Say Tomato, I Say Tomato. Catalogue 2010

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

2 -

download

0

Transcript of You Say Tomato, I Say Tomato. Catalogue 2010

4. 5. 6. 7. 17. 20. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26.

28. 30.

Curators: Nathalie Boobis & Anna FC SmithFor NXNW Arts Festival 2010

Curator’s IntroductionTimetable of eventsGallery planList of artists and worksDetails of additional contributorsPlate 1 ‘Did She, Did She Drawing’, Sally Taylor‘They Said They Spoke English’, poem by Joy L. Smith‘Can you show me how to attach an email?’, AnonPlate 2 ‘Head Speaking’, Sally TaylorPlate 3 ‘Mouth with Triangles ‘aaa’, Sally Taylor‘The Fishermen Hung The Monkey O’, Geordie dialect poem byEd CorvanExtract from ‘The Road From Wigan Pier’, Richard Donald Lewis‘Disagreement and the Cognitive Philosophy Machine’, essay by Alexis Makin

Contents

4 5

An introduction from the curatorsThe idea for You Say Tomato, I Say Tomato grew out of an informal discussion about the nature of disagreement between Anna FC Smith and neuroscientist, Alexis Makin. Through further discussion with Na-thalie Boobis, it soon became apparent that disagreement was only one of the many outcomes of linguistic communication, a topic which seemed to the curators to be a compelling subject for an exhibition.

The speaking of language is as much a primary human activity as eating or drinking are. It is how we make sense of our world, tell oth-ers about it, express our desires and frustrations, chat, gossip, ques-tion, coordinate, plan, and so on. We are constantly struggling to use the right words to express ourselves; to weave our stories, and for the language we use to be understood by others. In this sense, every conversation we enter into is a game of sorts in which we each must choose our words carefully and tease words out of our conversation-al partner in order to reach the intended meaning.

You Say Tomato, I Say Tomato is as much an exhibition of artworks as it is a collection of different people’s ideas about, and expressions of, the ever fascinating and problematic role that language plays in our existence as humans. The works on show all explore a slightly different facet of the language game; from arguments deriving from confusion over the meaning of a word to abusing the expectations of a karaoke song. What all the works have in common, however, is that they all express something of the nature of spoken language.

You are invited to walk upon the game board, amongst the pieces and to engage with the discussion in play. None of the works pres-ent an answer or definitive meaning; they are each a potential new conversation to take beyond the board and beyond the show.We hope you enjoy the discussion!

Extra special thanks are due to the WMC and thanks also goes to all the NXNW members, volunteers and donors that helped to make this show possible.

The curators,Nathalie Boobis & Anna FC Smith

Monday

Tuesd

ay

Wednesd

ay

Thurs

day

Frid

ay

Satu

rday

Sunday

7th

8th

7pm

Pri

vate

Vie

w

7.30 -

7.35pm

Annie

Abra

ham

s &

Anty

e

Gre

ie,

A M

eeting is

A

Meeting is

A M

eeting

3.3

0 -

4pm

Louis

e

Fazack

erl

ey, Po

etr

y

5 -

5.0

5pm

Annie

Abra

ham

s &

Anty

e

Gre

ie, A

Meetin

g is

A

Meetin

g is

A M

eetin

g

9th

10th

11th

12th

13th

14th

15th

1.3

0 -

4.3

0pm

Poetr

y

work

shop w

ith J

ohn

Togher

5 -

5.0

5pm

A

bra

ham

s

& G

reie

, A

Meeting…

5 -

5.0

5pm

A

bra

ham

s

& G

reie

, A

Meetin

g...

5 -

5.0

5pm

Abra

ham

s

& G

reie

, A

Meetin

g…

5 -

5.0

5pm

Abra

ham

s

& G

reie

, A

Meetin

g...

4 -

4.3

0pm

Mart

in

Hig

gin

s, S

poke

n w

ord

5 -

5.0

5pm

Abra

ham

s

& G

reie

, A

Meetin

g…

12.3

0 -

2.3

0pm

Cla

re

Charn

ley,

Mis

und

ers

tand

ings

2.3

0 -

3.3

0pm

Ale

xis

Maki

n,

Dis

cuss

ion

5 -

5.0

5pm

Abra

ham

s

& G

reie

, A

Meeting…

3.3

0 -

4pm

Louis

e

Fazack

erl

ey, Po

etr

y

5 -

5.0

5pm

Abra

ham

s

& G

reie

, A

Meeting…

16th

17th

18th

19th

20th

21st

22nd

GA

LLERY C

LOSED

3.3

0 -

4pm

Louis

e

Fazack

erl

ey, Po

etr

y

23rd

24th

25th

26th

27th

28th

29th

GA

LLERY C

LOSED

12.3

0 -

1pm

, 2.3

0 -

3pm

& 4

.30 -

5pm

Hele

n S

ilverw

ood,

Poetr

y

3.3

0 -

4pm

Mart

in

Hig

gin

s, S

poke

n w

ord

12

.30 -

1pm

Hele

n

Silv

erw

ood, Po

etr

y

3.3

0 -

4pm

Louis

e

Fazack

erl

ey,

Poetr

y

30th

31st

1st

2nd

3rd

GA

LLERY C

LOSED

6 7

D4 MJ VentingE4 & E5 Jesse Johns Winter-Tuck: Candle in The WindG5 Patrick White: Tomato PathsB6 Dwayne Butcher: It’s Got a HemiH6 Simon Morse: Between OurselvesA7 & B8 Jason Minsky: A Game of Two Halves E7 Anne Guest: It’s Not U It’s MeD8 Benjamin Bellas: KaraokeF8 Justin Lincoln: Shy

B1 Rachael Finney: HereD1 & E1 Annie Abrahams & Antye Greie: A Meeting is A Meeting is A Meet ingH1 Emma Bailey: Holes for InterpretationC2 Clare Charnley: The TranslationG2 Larry Caverney: Arm Wrestling InterventionA4 & B3 Candace Rose Davies: Wot a Fililoo & Ah Bet Yor Jus’ Lark MeyF3 Faye Peacock: I Paid People £10 to Say ‘I Love YouH3 Boobis & Smith: Defining Sentence

B1 Rachael Finney, Here

Rachael Finney is a Brighton based artist. She graduated from the the University of Brighton in 2007 with a BA Hons in Critical Fine Art Practice. She is currently studying for an MA in Critical Theory at the University of Goldsmiths, London.

Here directly explores the significance between the preposition ‘here’ and the action required on the part of the speaker to give it meaning (pointing). If ‘this’ complete with a finger point is the only genuine name for an object in the here and now then ‘here’ and ‘there’ are the only genuine names for geographical locations; everything else is only a name in an inexact, approximate sense. Finney illustrates this by repeatedly pointing to different spots on a wall and saying ‘here’. The staccato editing of the action highlights how the elemental name, ‘here’, is only applicable to any one spot at any one moment (whilst attention is being drawn to it by the stick) yet can mean everywhere over a period of time.

D1 & E1 Annie Abrahams & Antye Greie, A meeting is a meeting is a meeting

Annie Abrahams is an artist and biologist. Using video, performance and the internet, she questions the possibilities and limits of com-munication in general and, more specifically, investigates its modes under networked conditions. She has performed and shown work extensively all over the world from the Pompidou Centre, Paris, to the New Museum, New York.

Antye Greie (aka AGF) is a composer, vocalist, producer, e-poet and multi media artist born and raised in East Germany. In her profes-sional career as a recording and performning artist she has released 20 LPs and played hundreds of live performances the world over. Her installations have been shown in contemporary museums and institu-tions as well as on the World Wide Web.

From the 5th till the 14th of August, Annie Abrahams in Montpellier, France, and Antye Greie in Hailuto, Finland, will meet for 5 minutes every day via a special webcam interface. The performers will be

8 9

speaking English, neither of their native languages, and the audi-ence, the third participant in this 3 way conversation, will be in Wigan, England. Abrahams and Greie will explore a different theme each day using text, sound and image. The themes they plan to cover are: love, communism, wilderness, news, collaboration, space, patrio-tism and, of course, tomatoes. Neither artist has ever met in person and both are from different generations, different countries, different cultures and are hampered by the time lags, glitches and bandwidth problems of internet communication. The two conversationalists will bring quite different areas of knowledge, opinions and backgrounds to the meetings. The audience will be able to witness how these fac-tors influence the use of the chosen thematic words. The piece culmi-nates, appropriately, in a discussion on the subject of tomatoes as when one artist says tomato and the other says tomato, they will be talking about something subtly different

H1 Emma Bailey, Holes For Interpretation

Emma Bailey, originally from Cheshire, is currently based in Lincoln where she teaches at The Giles School which specialises in visual arts. She is a practicing artist herself and makes performance and video work that is predominantly concerned with humour and the way in which it can serve to communicate to, and engage with, an audience. She graduated in 2007 from the University of Brighton with a BA Hons in Critical Fine Art Practice and in 2010 with a PGCE from Edge Hill University.

In this work Bailey asked a number of people to hum the same song from popular culture, in this case “Lets Call The Whole Thing Off” by George and Ira Gershwin, itself being a comment on the nature of relationships fracturing due to differing approaches to pronunciation. Well known tunes such as this exist in collective memory so are recog-nisable to the majority of people. However, what Bailey’s work shows are the differences between collective and personal memory as when we recall such tunes, the nuances and details of the original are often lost or warped, creating a flawed translation of reality. Each transla-tion in the work differs both from its source and between the individu-als performing it.

C2 Clare Charnley, The Translation

For some time Clare Charnley has been working around issues of translatability and the politics of language both in a personal and global context. She is particularly interested in using linguistic and cultural ignorance as a means of generating situations of mutual vul-nerability. Another interest is the act of misunderstanding which can be seen as creative or revelatory. Recent exhibitions, performances and screenings include The Casino, Luxembourg, Dashanzui Festival, Beijing, Performance Art Platform, Tel Aviv, Castle of The Imagination, Poland, Ex Teresa Arte Actual, Mexico and The Living Art Museum, Reykjavik. Clare is currently collaborating with Patricia Azevedo (Bra-zil) with whom she was shortlisted for the Northern Art Prize.

The video is in three sections; in the first an old poem is read out in Turkish - it describes an event that takes place as munitions are being transported by ox cart. In the middle section the poem is translated into English. Finally it is read out in English. The interpreter and the artist sit between the yoke of an old ox cart attempting to reproduce the sense of the Turkish poem in the English language. The Turkish speaker and the English speaker to and fro between possible equiva-lents of words in the poem; interpreting the words but more impor-tantly trying to preserve meaning and poetic character.

G2 Larry Caverney, Arm Wrestling Intervention

Larry Caverney works predominantly in the medium of performance and performance for film. He is interested in ideas of social engage-ment; in making art that is accessible beyond the art world; and in the role of the artist within a given community. Caverney has a Mas-ters in Fine Art from Vermont College and has his work held in perma-nent collections in the Asheville Museum of Art, Asheville, USA and in the Castoria Contemporary Museum in Naples, Italy.

This piece explores argument from the angle that opinion is condition-al of education, background and experience. The argument arises around a painting, the type of object which can be described by Wittgenstein’s phrase ‘seen as’ where one is reporting what one sees rather than interpreting it. This type of object does not have a single

10 11

reading; it is the viewers opinion which shapes it, therefore it may be ‘seen as’ one thing or ‘seen as’ something else. The nun exposes the argument as redundant as the gallery-goers are both correct in their positions and so the only option for resolve is to abandon the verbal in favour of the physical: an arm wrestle.

A4 & B3 Candace Rose Davies, Wot a Fililoo and Ah Bet Yor Jus’ Lark Mey

Candace Rose Davies is a Wigan based artist with a BA in Fine Art from the Arts Institute at Bournemouth. Candace’s practice combines photography, film, sounds and smells to magnify the often unper-ceived beauty of the mundane. Working with video projection and installation she strives to create romantic pockets of ordinary-sublime beauty.

Wot a Fililoo or, ‘What a Din’ in Standard English, and Ah Bet YorJus’ Lark Mey are both part of a sound installation in which the listener is privy to an extract from an autobiography in Wigan dialect and a humourous musical conversation combining modern and traditional accent and dialect. Wot a Fililoo was written and spoken by Richard Donald Lewis an expert in regional dialect and accent. The piece is a celebration of an almost extinct method of communication, and brings to life the obsolescent dialect of Wigan. Ah Bet Yor Jus’ Lark Mey is a collaboration between the artist and Chonkinfeckle, a local musical duo made up from Wigan lads, Les Hilton & Tim Cooke.

Hearing accent and dialect in this context exposes how language develops through geographical, historical and cultural influences and can both isolate and unite a region. Linguistic sub-rules form on all the strata of society nationally, regionally and on the individual level. The Wigan accent and dialect formed from a myriad of separate influences including the settlement of some of Bonnie Prince Charlie’s Scottish troupes after their defeat during the Jacobite Revoluion of 1745 and Norse settlers. Such historical events plus the weather, type of industry and wealth of a region have an effect on the people and therefore their speech, as Lewis says:“The pits and mills of Wigan, the climate, isolation, hardship and poverty bred a dialect with a ring of despair.” With the advent of television being based predominantly

in the south, the standard rules of the English language have dis-seminated across the country and isolated regional dialects are being slowly eradicated, therefore the dialects of the young and old have fractured. Even now in Wigan many may find it difficult to understand what is said in this work.

F3 Faye Peacock, I Paid People £10 to Say ‘I Love You’

Faye Peacock is a London based artist who has exhibited and per-formed nationally and internationally. Peacock graduated from Not-tingham Trent and later from Wimbledon College of Art with an MA in Sculpture. Following on from this she has shown work at Gallery North, Newcastle, Room Gallery, London, Bonington Gallery, Notting-ham as well as working on projects in Berlin and Istanbul.

In this work, the artist offered £10 to strangers if they agreed to sit in a car with her and convincingly tell her that they loved her. When speaking, we have a choice as to whether we vocalise a truth or a lie. Our words do not have to correlate with our thoughts; we are at liberty to fabricate when we speak as it is more likely to be our bod-ies rather than our words that expose us for liars. What is hidden in Peacock’s work is the visual element of communication; the speakers may well have been blushing profusely or diverting their eyes from her gaze. Therefore the listener is left with just the verbal signs from which to assess the value of the exchange. It is the title of the piece that confirms the insincerity of the words.

H3 Boobis & Smith, Defining Sentence

Nathalie Boobis was born in Newcastle-upon-Tyne and studied Critical Fine Art Practice at the University of Brighton. She is an artist, work-ing in video and collage, and a curator. She has curated 3 shows in the last two years and her film work has been screened most recently at Cine City, Brighton and Limmud conference, Newcastle upon Tyne. She is currently living and working in Manchester.

Anna Smith is a video artist and illustrator as well as a curator. She has showed nationally and internationally including at Salford and Brighton film festivals, Cornerhouse Manchester and Drawgasmic at

12 13

Cranky Yellow Gallery, Saint Louis, MO. She has curated numerous shows for NXNW. In 2007 she also graduated from Brighton Univer-sity (which is where the pair met) with a BA Hons in Critical Fine Art Practice. She resides in Manchester.

Defining Sentence seeks to define a word through example. We are taught to speak using examples and gestures ‘this (pointing) is an apple’. But as our linguistic requirements grow it becomes necessary to rely on context and search dictionaries to navigate the significanc-es of words. Defining Sentence utilizes the definition sentences from dictionaries to define ‘sentence’ in a convoluted manner. Functioning as a dialogue, the work is laced with paralanguage, word play and red herrings thus exploring how many meanings a word can have depending on its use.

D4 MJ, Venting

For reasons beyond the curators’ control, it has not been possible to provide any information about the artist of this work.

In this work a couple argue about whether their bedroom window was open or “just vented” overnight. This unassuming domestic tiff clearly demonstrates a typical scenario where different ideas of the meaning of a word and the refusal to accept the other’s definition lead to disagreement. What is particularly interesting is the woman’s use of the common phrase “not in my book” which confirms the idea that we each hold our own set of rules within the language game.

E4 & E5 Jesse Johns Winter-Tuck, A Candle In The Wind

Jesse Johns Winter-Tuck is a Bristol based artist with an Arts degree from Bournemouth AUBC.

This kinetic sculpture is a succinct demonstration of the motions of a conversation; words passing between mouth and ear. The fans placed on either end of the track are the embodiment of both speaker and listener giving function and meaning to words, as without either the car/conversation would stop.

G5 Patrick White, Tomato Paths

Patrick White graduated from the Slade School in 2006 and lives and works in London. His works predominantly with sound.

The audio is generated by a Java app written by James Merryfield us-ing the CloudGarden SDK and WordNet database, in conjunction with MAX/MSP. James Merryfield is a physicist and programmer living in Surrey.

Tomato Paths is a sound piece that is operated by specially produced software in which two speakers take a semantic journey through the definitions of words from a dictionary, starting with the word ‘toma-to’. The first word generates a definition from which another word is chosen by the computer and defined. This continues indefinitely creat-ing a sequence of subsequent definitions. Though the starting point remains the same, the sequence alters day by day as the words from the definitions are chosen at random.How effectively we communicate is dependent on our understanding of the meaning of a word. If we do not fully comprehend a definition or if we mistakenly use a word in the wrong context, the meaning of our sentences can be obscured. In the case of this piece, each speaker outputs a different sequence of definitions from the other, taking the original word on a different path. At times the paths may diverge, making no sense to each other; they may follow the same path as each other; or they may converge to create meaning or even poetry. The work is an exploration of how technically defining words can actually take one away from their contextual meanings.

B6 Dwayne Butcher, It’s Got a Hemi

Dwayne Butcher is an artist working in Memphis, Tennessee. In 2009 he received the Individual Artists Fellowship from the Tennessee Arts Commission. Butcher is the author of the artbutcher blog, a website chronicling the Memphis art scene and the artist’s quest to be fa-mous. Butcher’s work was recently included in the exhibition, Lo-Fi, Hi-Fi: New Video Work at the University of Mississippi. This year, he is included in Currents2010 at Parallel Studios in Santa Fe, NM and will attend the Vermont Studio Centre, for which he received an artist’s

14 15

grant. His work is represented by the David Lusk Gallery in Memphis.

It’s Got a Hemi refers to an American bumper sticker that the artist saw on a passing car, it being common in America to stereotype your personality through car adornment. In this case the label chosen by the driver which can be considered his/her ‘private language’, fails to work as a defining statement as Butcher, representing the public respondant, does not know what a Hemi is. Butcher is then forced to work through and debunk every possible stereotype in order to expose the potential meaning of the label. During his monologue we see a white man and a black man dress and redress in different cos-tumes. Butcher concludes that through his failure to define the anony-mous driver, he cannot even classify himself.

H6 Simon Morse, Between Ourselves

Simon Morse was born in Swindon and studied fine art at Liverpool Polytechnic (BA) and Chelsea College of Art & Design (MA). He has exhibited widely in the UK, the US, Germany, the Netherlands, Ire-land, Italy, Spain and Switzerland. He is represented by the Gooden Gallery, London.

Between Ourselves is a physical manifestation of the mechanism of speech in which the process of verbalising transfers from the cogni-tive to the manual. The ‘russia/china’ dial suggests that this work is depicting the duplicitous style of dialogue that proliferated during the Cold War conflict between the Capitalist West and the Communist superpowers. The Cold War itself was an ideological battle of view-points that was fought mainly through the linguistic mediums of propa-ganda, alliances based on verbal agreements and threats. The clash of ideologies between the East and the West was ultimately a clash of philosophy and philosophy, according to Wittgenstein, is language. Therefore, Between Ourselves, is a metaphorical representation of the act of fine tuning and adapting language to suit a given situation; in this case, the act of political negotiations in the verbal battles that precede war.

A7 & B8 Jason Minsky, A Game of Two Halves

Jason Minsky is a Manchester based artist. His practice includes video, photography, multiples, installation and performance. He studied 3D Design BA hons at Manchester Polytechnic 1989-1992 and completed a masters at the Royal College of Art in 1999. He has had residencies at Headingley Stadium, Leeds and most recently at the Centre of Sports and Exercise Science, Sheffield Hallam University. He has been nominated for a number of awards including Becks Futures in 2004 and the ART08 awards, Manchester, 2008. His many shows include ‘Collaborations’ at the V&A, London; ‘Natural Dependency’ at the Jerwood Gallery, London’ ‘Takeaway Garden’ at CUBE, Man-chester; and ‘Match Report’ at Project Space Leeds (PSL).

A Game of Two Halves is a documentation of a live performance. The set up sees two typists, wearing headphones and sitting at mobile desks. One is transcribing cricket and the other rugby. As they type on either end of a long piece of paper they are drawn together, their trajectory eased by a referee. Although both are listening to game commentaries and filtering these words onto paper, the rules of each game are different so the two transcriptions can never be more than two disinterested monologues. The whole game therefore can be seen as a metaphor for the kind of conversation where the partici-pants speak at each other without developing each other’s ideas or listening to each other’s statements.

E7 Anne Guest, It’s Not U It’s Me

Anne Guest studied at Birmingham City University, 2002-2005 (BA Fine Art) and 2005-2006 MA Fine Art. She has exhibited nationally and internationally and was shortlisted for the Jerwood Drawing Prize in 2008.

It’s Not U It’s Me explores the newer phenomenon of communicating through speech that has been transcribed into a written code, such as with ‘live chat’ on an email homepage, Facebook or a chat room and most prominently, with text messages. Guest’s work deals specifi-cally with SMS communication and exposes the potential confusio-nand misunderstanding that occurs when the informality of speech is

16 17

approximated in ‘text speak’ without the necessary addition of into-nation, gesture or expression.

D8 Benjamin Bellas, Karaoke

Benjamin Bellas is a Chicago-based artist who has exhibited his work nationally and internationally at various venues such as Contempo-rary, Istanbul; Track 16, Los Angeles; Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago; La Space, Hong Kong; Hyde Park Arts Centre, Chicago; and Academy of Fine Arts, Helsinki. He is the recipient of an Illinois Art Council International Artist Grant, and has been awarded residencies at Redux Contemporary Art Centre, 1a Space, and the Contemporary Artists Centre. Bellas is currently a member of the faculty in Contem-porary Practices Department of the School of Art Institute of Chicago.

This work is a video of a live performance in an American karaoke bar. In it Bellas reverses the usual recital style of ‘Don’t Worry, BeHappy’ by Bobby Mcferrin. The reassuring and easygoing mood of the song is replaced by an agitated and dissonant version as Bellas performs it. By reclaiming familiar lyrics and using inappropriate into-nation to express meaning beyond their intended use, Bellas exposes the fact that words themselves hold no meaning and it is the way we say them that matters; as Wittgenstein asserts: “meaning is use”.

F8 Justin Lincoln, Shy

Justin Lincoln is an American artist with an MFA (2002) from the Cali-fornia Institute of the Arts, USA. His films have been shown widely in film festivals, including Cine-X, 26th Olympia Film Festival, Olympia, The Ten Second Film Festival at the Soap Factory, Minneapolis, and the Disposable Film Festival in San Francisco, New York, London, Paris and Bejing.

Shy focuses on a young girl, whose first language is not English, and her American off screen partner. The man behind the camera at-tempts to initiate a conversation but instead of responding in kind, the girl defers to her shyness, hiding behind mimicry. As the man’s frus-trations at her refusal to cooperate become apparent, the girl

begins to knowingly take charge of the conversation by copying his words; mocking him and making him answer his own questions. The girl’s continuing copying, but with her own inflections and facial expressions, exposes the extraneous nature of words as signs for a speaker’s thoughts. It is her use of his words that convey her meaning and not the words themselves.

Additional Contributors:

Spoken Word Events

Louise Fazackerley 3.30 - 4pm - Sunday 8th, 15th, 22nd & 29th August

Louise is a performance poet from Wigan who has won prizes at vari-ous poetry slams across the North West. She is a founding member of The Secret Writers’ Club, a writers group based in Wigan town centre, and director of The Talent Factory, a community arts organisation that facilitates arts projects.

Little Red Words explores misunderstanding generated by the idea of love and the phrase ‘I love you.’ Those three words obscure the real meanings behind what is being said. Stuck Unsaid is a poem about those occasions when someone says something that it is ‘wrong’; something racist or homophobic for example, something that you should challenge and then but don’t. The Taxi Driver’s Response was written to allow the ‘taxi driver’ the opportunity to say that essen-tially he believes in the same truths as the girl in Stuck Unsaid despite her assumptions. Political correctness and the attitudes and speech relating to class and education are some of the barriers that prevent them from understanding each other. She will be peforming:

Little Red Words- July 2010Stuck Unsaid- September 2005/ The Taxi Driver’s Response- July 2010Pink- June 2010

18 19

Martin Higgins 4 - 4.30 Friday13th August & 3.30 - 4pm Wednesday 25th August

Martin is a spoken word poet of sorts; his style has been described as “psycho-dreamland” and “stream of consciousness”. He works as a freelance graphic designer, plays the glockenspiel for the band ‘The Maladies of Bellafontaine’ and regularly performs his scribblings at poetry nights.

Helen Silverwood 2.30 - 3pm & 4.30 - 5pm Wednesday 25th August & 12.30 - 1pm Thursday 26th August

Helen is a Leeds based poet who runs a business specialising in per-sonalised poetry for special occasions. Since 2009 she has also been breaking into the Leeds open mic scene with her humorous, socially controversial poetry which has been met with both frowns and rau-cous laughter. Helen also works as a community mediator which she feels helps to provide authentic inspiration for her writing.

Helen’s poetry illustrates the impossibility of language as an exact tool of communication and shows how different understandings of the meanings of words within conversations could lead to misunderstand-ings which could cause great confusion, embarrassment, anger, and even violence and murder. She will be performing:

A Recent History of Good, 2010Are You Bent? 2010You Must Be Mad, 2010

Discussions and Workshops

The Misunderstandings Project12.30 - 2.30pm Saturday 14th August

Clare Charnley has been working around issues of translatability and the politics of language both in a personal and global context. She is particularly interested in using linguistic and cultural ignorance as a

means of generating situations of mutual vulnerability. Anotherinterest is the act of misunderstanding which can be seen as creative or revelatory.

The Misunderstandings Project consists of a purpose made computer database of linguistic, cultural and situational misunderstandings. There are currently over 100 videos n the archive. Its simple interface allows viewers to select, play and compare individual misunderstand-ings from a scrolling screen. Clare will be introducing her work on the project and participants will have a chance to add their tales of misunderstanding to the archive.

Talk and Discussion by Alexis Makin2.30 - 3.30pm Saturday 14th August

Alexis Makin is originally from Skelmsdale. He is about to complete a PHD in neuroscience at the University of Manchester.

Alexis’ essay, ‘Disagreement and the Cognitive Philosophy Machine’, inspired the theme of the show. He will be speaking about his work and opening the subject to discussion.

Creative Writing Workshop with Darren Thomas & John Togher1 - 3pm Monday 9th August

Wigan based Darren Thomas once served in The Royal Air Force, the Greater Manchester Police and in his local butcher’s shop on a Satur-day; each experience contributing their worth to his apparent innate sense of cynicism. He now spends much of his time studying the me-chanics of language.

John Togher is a published writer and poet from Wigan who puts on regular poetry and art nights across the North West. He is the editor of the Mental Virus and is also one third of the band, John The Bap-tist and The Second Coming.

Local writers John Togher and Darren Thomas will lead a creative writing workshop on the exhibition theme of ‘You Say Tomato, I Say Tomato’, looking at the nature of dialogic disagreement, malfunctions within conversations and the semantics of the spoken word.

22 23

They Said They Spoke English

They said they spoke EnglishIn Wales, But when I offered to side the tableIn Cymer they weren’t very grateful.They acted as though there was a danger Of me manhandling the board to the margins of the room.

They said they spoke EnglishIn London, But when I added ‘and put the door to’To the tardy Edmonton lad trying to creep unobtrusively into the class, He stopped, put his hand on the handle, And murmured ‘the door, Miss? To - what, Miss? What to?’

They said they spoke English In New York,But, after wedding celebrations that had lastedWell into the morning after, in New Jersey;When I asked the new bride if she’d partied all night, I got what can only be called a very frosty reception.

They said they spoke EnglishIn North Carolina, But a Leyther in Hush PuppiesWas stunned to his uppers by this friendly observationFrom an elegant lady who was waiting by the lift,(Or should that be, elevator?)

‘I see that you’re wearing your shagging shoes!’ *

Joy L. Smith 07/10

*NB The Carolina Shag is a six-count partner dance in which the up-per body and hips barely move, but there are convoluted kicks and fancy footwork.* Acknowledgements to the anonymous PPG worker whose story I have used here.

Can you show me how to attach an email?

Client: Can you show me how to attach an email?

Me: What do you want to attach to it?

Client: Well, what do you do? Press attach and then the contact’s name?

Me: What do you want to attach to the email?

Client: Well, say I want to write them a letter and then attach it

Me: You mean write them an email?

Client: But I want to write them a letter in Word and send it to them

Me: ...via email?

Client: Yes. Do I just click attach and then the contact’s address?

Me: Why not just write it in Outlook Express?

Client: Because I want to write them a letter, not an email.

Anonymous, 2010

24 25

Sally TaylorHead Speaking, 200934 x 29cmGraphite and acrylic on paper

Sally TaylorMouth with Triangles ‘aaa’, 201023 x 18cmGraphite and collage on book cover

26 27

*

*“The Fisherman hung the Monkey, O.” These words are the greastest insult you can offer to the Hartlepool fishermen. It is supposed when ‘Napoleon The Great’ threated to invade England, the fishermen were loyal and patriotic, and ever on the look out for spies. A vessel having been wrecked about this time all on board perished with the excepion of a monkey, which was seized by the fisherman for a French spy, and hung because he could not or would not speak English.

Geordie dialect poemA Choice Collection of Tyneside Songs (1863)Edward Corvan and G. Ridley

28 29

Tha’s bin starving/ it lone agen beht lappin’ thisell up proper!

Ast fert start maitherin’ when tha sees us ah’m clemmin’? Wheer’s pies? Ast hoven um eht th’oon?

That wants um prigmeet dustn’t? Howd thi din un cahr thi dehn while ah umbethinks me!

Aw reet, but hag thee, or ast be eightin’ um pindert.

Harken! Is beht getten wom un is hahmin’ un consterrin’ when have bin powfaggin’ misell aw mawnin, sidin’ un scratchin’ baggin fer yon lot! Gi’oer bein’ so sackless!

Worra Fililoo! Stop pooin’ thi chowf un gi’ us a jonock afoor ah’ goo slancin’.

That pikes off dehnt lone, jaftin’ un gallivantin’ aw mawnin, that loyses thi kale at butcher’s an comes wom wi powsy meight.

That sez it’s powse?

Ah metta clod it int flash.

Ditto?

You’ve been freezing outside again without wrapping yourself up prop-erly.

Do you have to start making a fuss when you can see that I’m starv-ing? Where are the pies? Have you taken them out of the oven?

You want them done just right, don’t you? Be quiet and sit down while I collect my thoughts!

All right but hurry up or I’ll be eat-ing them burnt up.

Just listen. He’s hardly got home and he’s snapping and arguing when I’ve been tiring myself out all morning, tidying up and getting food ready for all of you. Stop be-ing so fidgety.

What a din! Stop making a face and give me a piece of black bread before I start stealing something to eat.

Off you go down the street, living it up and socializing all morning – you’re last in the butchers queue and come home with poor meat…

You say it’s no good?

I might as well have thrown it into the lake.

Did you?

Un be beht fert pies? Thall’et eight wot that browt. Wheer’st bin fradgin’ anyroad?

Ainscough sex us Coddy’s sahned on that fillet Agnes agen.

Hm! Ah deht is getten aw his cheers awom. Oo met bit bross, but ooze widdert. An nangy an savvy, thanose! Ooze norrafe ler-ron wi yon mon, anter?

And have none for the pies? You’ll have to eat what you brought. Where have you been gossiping anyway?

Ainscough says that Coddy Has started courting that floosie Agnes again.

Hm! I don’t think he’s right in the head. She might be bonny, but she’s wrinkled. And bad tempered and deceitful, I can tell you. She’s really caught a prize with him, hasn’t she?

Extract from The Road From Wigan Pier, an autobiography by Richard Donald Lewis

30 31

Disagreement and the Cognitive Philosophy Machine

By Alexis Makin Abstract

In this work I propose that all human brains are endowed with a cognitive philosophy machine. This is composed of two basic modules. The first can retain language-based propositions about the world in a working memory like module (the ontological buffer). The second can evaluate the truth of propositions in the ontological buffer using learned algorithms or heuristics (epistemological rules). Disagreements between people occur because they are unwittingly evaluate different propositions (ontological misalignment), or because they use different epistemological rules (epistemological misalign-ment). Here I look at example disagreements from formalized everyday conversation, philosophy of mind and politics to demonstrate the cognitive philosophy machine in action. I conclude that understanding the workings of the cognitive philosophy machine can illuminate the nature of prologed disagreement, and thereby simplify our understanding of disputed topics.

32 33

Introduction

Humans can evaluate the accuracy of propositions about the universe. Unfortunately, we frequently disagree with each other. If every combina-tion of people took turns to engage in an exhaustive dialogue about what the universe is like, there would probably never be a perfect match. In this work I make a simple assumption about the nature of disagreement: if two people are talking about exactly the same proposition (same ontology), and they are using the same system of rules for deciding whether the proposition is accurate (same epistemology), then they will always agree. Presumably disagreement occurs for 2 elementary reasons. 1) They are not discussing exactly the same proposition (ontological misalignment) or 2) They are not using the same system of rules for deciding whether the proposition is ac-curate (epistemological misalignment). I also argue that ontology and epistemology are ultimately informa-tion processing operations carried out by the brain, with a cognitive philoso-phy machine. We should therefore be able to diagnose disagreements as ‘differences in place A of the opposing parties cognitive philosophy ma-chines’ or ‘differences in place B of the machines’. A realistic model of hu-man the cognitive philosophy machine could shed light on ongoing disagree-ments, and make the universe a less bewildering place. Later I will apply the model to some heated debates in academia and politics. These serve as demonstration of the cognitive philosophy machine in action. Before I describe the brain’s ontological and epistemological ma-chinery, I would like to pre-empt potential confusion. First, I stress that I am not just talking about the theoretical differences between academic phi-losophers. Everybody ‘does philosophy’. In other words, everybody makes justified decisions about which propositions to take seriously. The cognitive model outlined below applies to ordinary philosophical activity, not just writ-ten academic thinking. I also stress that the examples used here are deliberately and massively oversimplified. This is because I want to capture the fundamental components of the cognitive philosophy machine. Many of the example disagreements below lack ecological validity. That is, they bear little resem-blance to real life debates where many different phenomena co-occur and interact. This is akin to experiments in cognitive science, where extremely simple and unrealistic stimuli are used to isolate fundamental mechanisms. Here, simplified disagreements are used to isolate the workings of the cogni-tive philosophy machine. In short, I am pleading with the reader to suspend their judgment until the end, rather than prematurely dismissing the exam-ples as incomplete or reductive.

The ontological buffer

Animals are constantly bombarded with sensory information about the nature of the universe. In fact, animals behave as on-line scientists. Unex-pected sensory input is treated as a hypothesis. The hypothesis is then tested by gathering additional sensory information. For example, when we see something that looks like a face, we move our gaze to critical regions (such as where the eyes and mouth would be) to establish there is indeed a face in front of us. This primitive but ultra high speed hypothetico-deductive rea-soning is one type of philosophy machine in the brain, but it is not the main topic of this work. Instead, we will look at the cognitive philosophy machine which processes language based propositions about the universe.Humans often encounter linguistic propositions about the nature of the uni-verse which do not correspond to events in our immediate sensory environ-ment. Nobody has any trouble processing propositions such as ‘Polar bears live in the north of Canada’, ‘Dinner is in the oven’, or ‘The Earth is a globe revolving around the sun’. Importantly, we know how to treat these patterns of auditory or visual input. We do not just respond to propositions in some ritualized way (i.e. by saying ‘yes’ or ‘no’), as a songbird might respond to the squawks of other songbirds. Instead, humans can update an internal simulation of the universe in a meaningful way. Most of this Virtual Universe is stored in Long Term Memory (LTM), and is not involved in current behav-iour. However, we can selectively attend to small parts of the virtual universe and place the attended information it in a working memory like buffer (Baddeley, 1986). This working memory-like part of the cognitive philosophy machine can be called the Ontological Buffer (Figure 1). Information in the Ontological Buffer is not pure. If somebody says to me ‘Polar bears live in northern Canada’. It activates my prior representa-tions and my knowledge of polar bears, not theirs. Although they can put an item in my ontological buffer, it will not necessarily be the same item they have in their own ontological buffer. If I bizarrely used the word ‘polar bear’ to mean ‘panda’, I might respond, ‘You are definitely wrong, polar bears live in China!’. Presumably this confusion would be quickly ironed out in the next few conversational turns. The interlocutors would soon realise they were not evaluating the same proposition. They would recognize that they were in a state of ontological misalignment.

34 35

Figure 1: The ontological buffer. Auditory or Visual language input is processed by sensory systems, and it activates prior knowledge in long term memory (or virtual universe). This proposition is then held in a short term working memory-like ‘ontological buffer’. Other systems are required to compute the accuracy of the contents of the ontological buffer.

When the proposition is more complicated, ontological misalignment could be a major source of disagreement. For example, the word ‘anarchy’ is used by different people to betoken to quite different socio-political arrange-ments. In common parlance, ‘anarchy’ refers to some kind of youthful chaos with no state infrastructure or legal system. However, in some academic circles, the word refers to a system whereby most political and organization-al decisions are made with a high level of input from the population. In these circles anarchy means something like ‘extreme democracy’. Of course, when these academics propose anarchy as a desirable political system (in the for-mal sense of the word ‘anarchy’), they are often treated with derision from those who (using the common parlance) assume they haven’t considered the negative consequences of abolishing the legal system. This disagreement is basically a side effect of the impure nature of propositions in the ontological buffer. The parties are discussing different things while unfortunately using the same words. This phenomenon is often unrecognized for prolonged periods of unnecessary confusion. Let’s consider another example of ontological misalignment. Some people believe abortion is tantamount to murder (pro-life). Some people be-lieve abortion is undesirable but acceptable under some circumstances (pro-

choice). Both parties agree that abortion involves eliminating the foetus in the early stages of development. Unfortunately, pro-lifers and pro-choicers have different conceptual models of a foetus in their respective virtual uni-verses. For the pro-lifers, a foetus has a soul and is thus like a sentient being like any adult human. For the pro-choicer, a foetus has not got a soul, is not yet a sentient being. When the pro-choice group say abortion is justified, the pro-lifers (who have a sentient creature in their ontological buffer), respond that legalized abortion = legalized genocide. This disagreement is has the same structure as the above confusion about polar bears. In both cases, the opposing parties are unwittingly evaluating different propositions.

The epistemological engine

I suspect many readers feel a bit unsatisfied with the philosophical machine shown in Figure 1. Perhaps you accept that sensory analysis activates a particular set of concepts in LTM, which are then held in a short term onto-logical buffer. Hopefully it is clear how this cognitive architecture could give rise to people talking past each other, and therefore ending up in a state of prolonged disagreement. But how is truth apportioned to propositions? So far the model includes only a virtual universe, sensory input and an onto-logical buffer. The true-false decision seems to happen magically in another box, further downstream. Figure 2 shows an expanded version of Figure 1, with a new module for evaluating the contents of the ontological buffer ac-cording to some learned epistemological rules. Before we look at the epistemological rules, it is worth noticing that a person would have very poor social skills if they responded to every proposition by questioning its accuracy. We only need evaluate propositions if we are intent on establishing their accuracy. In many cases this may not be our objective in the first place. Sometimes we wish to agree or remain indifferent for that sake of social harmony. For example, an entertaining ex-aggeration would place a proposition in the ontological buffer. The proposi-tion would be judged untrue if fully considered, but it wouldn’t be given full consideration, because it would recognized that epistemological evaluation was not part of the social-language game. In short, the epistemological rules are fully activated when we perceive them to be task relevant. There must be an informational gateway between the ontological buffer and the episte-mological rules, which activates the latter only when apportioning validity is relevant to our social aims. For the purposes of this work, I will imagine scenarios where making the true/false decision is considered important.

36 37

Figure 2: The full Ontological buffer and Epistemological engine. As well as the system show in Figure 1, epistemological rules become active whenever justification is socially desirable. The epistemological rules are derived from culture or education.

The epistemological rules are learned heuristic or algorithmic systems for evaluating particular propositions. Everybody has a different set of epis-temological rules, depending on their culture and background. Moreover, different scientific paradigms also rely on different sets of epistemological rules (Kuhn, 1970, A Chalmers, 1999). Let’s consider a few prevalent episte-mological rules in Western culture. Hopefully these examples are so familiar that they will capture the nature of epistemological rules for all readers. One of the most common epistemological rules is ‘trust propositions in the ontological buffer if they arise from a respectable source’. If I judge a proposition to have arisen from a religious cult I will probably dismiss it. Conversely, if the proposition comes from a respectable physics text book, I might accept it immediately. In these cases I would be using the source credibility rule to decide whether a proposition in the ontological buffer is accurate. Let’s look at another example. If the proposition ‘Our new drug Proquack is more effective than placebo’ was traceable to a pharmaceuti-cal industry sponsored source, I will assign it far less weight than if the same proposition came from an independent scientific article. I presume that most people use the source credibility rule during everyday argument, perhaps more than they should. Another epistemological rule might be something like ‘trust proposi-tions when they explain a number of reliable observations’. Consider a

proposition such as ‘drug industry trials are corrupt’. This proposition is vali-dated by the observation that drug industry trials are 4.9 times more likely to show positive results than independent drug trials. Another common rule might be ‘trust propositions that are consis-tent with my virtual universe’. As discussed, our long term memory includes largely unconscious virtual model of the universe. For the sake of demonstra-tion, let the following proposition reaching your ontological inbox:

‘Earthquakes are caused by wickedness in overlying towns’.

If you have a secular virtual universe, then you will immediately object. For you, earthquakes were already caused by friction between slowly shifting plates of the earths crust, and have nothing to do with human affairs. The idea that they are something to do with wickedness is inconsistent with your virtual universe. But why did you accept the secular proposal in the first place? Well for one, it was from a respectable source, and second, it ex-plains the fact that earthquakes usually occur along predictable fault lines. Note that you do not accept the secular proposal ‘because it’s obviously true’. That would be a completely meaningless claim. Rather, you accept it because you employ various epistemological rules indicate that it should be considered true. Let’s look at a few less everyday epistemological rules. Scientists often test propositions such as: ‘People are rate themselves as happier on a numerical scale after taking Proquack than placebo’. Next, they decide whether to take the proposition seriously by using the epistemological rule: ‘the numerical pattern is meaningful if there is a less than 5% probability of it occurring by chance’. They then use statistic tests to decide on the prob-ability of the pattern occurring. Whereas the everyday epistemological rules above are fairly intuitive, a more complex epistemological rule such as a sta-tistical test would never be spontaneously employed without specific educa-tion. Nevertheless, inferential statistics function in the same way as the more commonplace rules considered above. They are recognized, but ultimately arbitrary algorithms for deciding the truth value of a proposition. How does the epistemological engine contribute to disagreement? Most simply, everyone uses different rules, or they apply different rules at different times. For example, some people test the proposition ‘Jesus walked on water’ with the epistemological rule ‘believe everything claimed in the bible’. At the same time, a scientist would reject the same proposition be-cause it is inconsistent with her understanding of water and human abilities, and because she does not judge the bible to be a credible source. Neither party has made a computational error: they are just testing the proposition ‘Jesus walked on water’ with different epistemological software. Eventually the Christian and the scientist may realise what’s going

38 39

on in their debate. They may notice that they are using different epistemo-logical rules to decide whether the proposition is true. In fact, if they were successfully at simulating each others cognitive philosophy machines, then there would be no debate, just harmonious acknowledgement that different rules give different results. What would happen next? Providing that they do not just agree to disagree, they would ideally move on to a meta-debate, in which they argued that some rules are better than others. What would be happening in the model now? The proposition ‘believe everything you read in the bible is a good rule’ would be in both the Christian and the scientist’s ontological buffers. They would bring other ‘meta-rules’ to into play: the scientist might use a rule such as, ‘if another rule helps reject more propositions, it is a good rule’, or ‘consistency always trumps source credibility’. The Christian might use a different meta-rule such as, ‘if a rule allows propositions which make the universe seem moral, meaningful or just, then it’s a good rule’. Given the vast number of potential epistemological rules and meta-rules on offer, no wonder there is so much disagreement about life’s big issues. It can be seen that the cognitive philosophy machine can only validate epis-temological rules by using other epistemological rules. In this model, there is no great beyond, no absolute, luminescent epistemological rules that we can potentially employ validate our propositions. This relativist contention does not mean that all propositions about the universe are equally accurate, but (and this is an important distinction) that the cognitive philosophy machine has no unequivocal means of judging their accuracy.

How are simple disagreements resolved?

To summarize the model of the cognitive philosophy machine, there are two components. There is a working memory store, which holds linguistic propo-sitions about the universe (the ontological buffer) and a system of rules for evaluating the contents of the ontological buffer (the epistemological rules). Disagreement can arise by two fundamental problems 1) There are different propositions in the ontological buffers of each party or 2) different episte-mological rules are being used to evaluate the contents of the ontological buffer. In this section I give formalized demonstrations of disagreement resolution. These examples serve to further clarify the nature of the cognitive philosophy machine. Often disagreements are resolved by simply getting one of the par-ties to repeat their judgements and correct their calculations. For example, I might propose that ice cream causes sun burn. After all, the proposition explains a reliable observation: Ice cream sales and cases of sun burn are highly correlated. Hopefully someone will encourage me to think again! When my philosophy machine re-runs the proposition ‘ice cream causes

sun burn’, I would recognise high temperature and sunburn are even more tightly correlated than ice cream sales and sunburn. In original case, too narrow a focus on a single observation lead to the wrong conclusion. When prompted to consider additional observations, the proposition is judged false. Another simple way disagreements can be resolved is by mutual recognition that different items are in each others ontological buffers. This was what happened in the polar bear-panda example above. Many trivial disagreements are resolved by such events. What about more protracted disagreements, which are not quickly resolved by repeating epistemological rules or aligning the contents of the ontological buffer? How are these ever resolved? One strategy during disagreement is to force to opponent to check-mate themselves by instilling them with new epistemological rules that give a different judgement about a proposition. Let’s take the Christian versus scientist debate about whether Je-sus walked on water as an example again. In this highly simplified scenario, imagine the Christian has only the source credibility rule at her disposal. The scientist might be able to explain the consistency with the virtual universe rule to the Christian, and train her in its application. The Christians certainty about Jesus walking on water would be abolished, because the new episte-mological rule gave a different result. Perhaps the scientist could also train the Christian to use meta-rules that showed that the consistency rule should be given more weight than the source credibility rule. By the gradual instal-lation of new epistemological rules, the scientist fully convinces the Christian to re-appraise the contents of her ontological buffer. Of course, in real life many of these strategies are employed quickly and unconsciously in a noisy environment with varying levels of resistance. However, the examples serve to give a flavour of the underlying simplicity behind all disagreements. Disagreements can always be attributed to mis-alignments in the ontological buffer or misalignment of the epistemological rules employed to evaluate its contents. The oversimplified and unrealistic disagreements above serve to purify and abstract the workings of the cognitive philosophy machine. They are like the simplified stimuli used in psychological experiments. These idealised disagreements make the putative mechanisms as clear as possible, but they bear little resemblance to real life disagreement. In the next section we will look as two real academic debates and see how even these sophisticated arguments can be understood as the dynamic functioning of cognitive phi-losophy machines.

40 41

Case study 1: Dennett vs. Chalmers: Rivers of misalignment

Two of the best-known contemporary philosophers working on the mind-body problem are Daniel Dennett and David Chalmers. Their positions are very different. The spiralling debate between these two should provide an excellent insight into how the cognitive philosophy machine contributes to academic disagreement. The point here is not to argue for the Dennett or Chalmers camp, but to passively observe the nature a typical exchange, and diagnose the disagreement either as ontological or epistemological misalign-ment. David Chalmers argues that modern neuroscience has told us a lot about the brain. It has shown us how the brain takes sensory input from various peripheral detectors, integrates that input, and guides actions. The story told by neuroscience is relayed in the third-person perspective. It is an account, ultimately, of atoms colliding and moving in systematic ways. Ac-cording to neuroscience, the brain differs from a clock or thermostat only in its degree of complexity. Like a clock, it is still a physical machine, made of physical matter following simple laws. However, Chalmers argues, conscious experience cannot be un-derstood as a physical system. What exactly is a conscious experience of, say, red, or the smell of coffee, or the hum of traffic in the distance? Yes, there are physical neural systems which respond to wavelengths of light, chemicals released from the coffee and pressure waves in the atmosphere produced by traffic. These neurons connect to other neurons and so on, until the muscles contract to produce behavioural responses, such as uttering the sound ‘rose’, or picking up the coffee cup. But why doesn’t all this physical neural activity happen in the dark? Where does the conscious experience of red fit in with the physical system? David Chalmers called this paradox ‘The hard problem of consciousness’. It is contrasted with the (relatively) easy problems, such as how neurons in the visual cortex at the back of the brain are connected to the eye so as to discriminate wavelengths (D Chalmers, 1995, Velmans, 2009). Daniel Dennett does not think there is a ‘hard problem of conscious-ness’ (e.g. Dennett, 1991). He claims that, when all the complex neural systems are understood, there is nothing left to explain about the human mind. There is no mysterious consciousness which cannot be understood as a pattern of physical events in the brain. He exemplifies his position in a short dialogue (Dennett, 2002). In this work two fictional philosophers debate the hard problem of consciousness. One of the philosophers adopts the position of David Chalmers, by always insisting that there is something left out of the physicalist account of the neural processing in the brain. The other philoso-pher perpetually retorts that the ‘thing left out’, if anything, is not some mysterious ‘consciousness’, but just some additional physical neurocognitive

systems. The Chalmers-like character always responds: ‘No! even when you include these other neurocognitive systems into your model, there is still something left out, that is, of course, the conscious experience of redness it-self’. And so it goes on. How can we understand this extremely controversial disagreement? In this debate, Chalmers puts something in the ontological buffer, ‘There are neurons in the brain, (which are made of atoms in a dynamic spatial arrangement) that fire whenever an object reflecting light of a certain wavelength is placed in front of the eyes’. This is tested by an epistemologi-cal rule. The proposition explains observations from microelectrode record-ing studies in monkeys (for instance), so it accepted as correct. Chalmers then runs another proposition through his philosophical machine. He adds ‘the conscious experience of redness’ to his ontological buffer. The existence of this entity is justified by a special epistemological rule: an appeal to self evidence. In other words, we just know that ‘the experience of redness’ exists, by virtue of having the experience (this is the epistemological rule use by Descartes in his famous ‘I think therefore I am’ argument, Velmans, 2009). Now two things are included in Chalmers’ virtual universe: 1) neu-rons sensitive to a certain wavelength of light and 2) the conscious experi-ence of red. The existence of these two entities is justified independently via different epistemological rules, even though they don’t fit well together. Dennett, like Chalmers, accepts the proposition that specific physi-cal neurons in the brain respond to wavelengths of light. He uses the same epistemological rules to justify this proposition. Now Dennett has the trouble-some second proposition place on his ontological buffer; ‘conscious experi-ence of redness’. However, Dennett does not apply the epistemological rule of ‘self evidence’. Instead applies the ‘virtual universe consistency’ rule. There bizarre substance called ‘conscious experience’ doesn’t fit with the physicalist account of the brain which dominates Dennett’s virtual universe, so he concludes that it does not exist. Or at least, it conscious experience doesn’t exist in the way Chalmers claims. The crux of the matter is that ‘conscious experience of redness’ can only ever be judged to exist by application of the self evidence rule. The existence of red sensitive neurons cannot be justified with the self evidence rule, but can be justified with other epistemological rules which are uncon-troversial. Chalmers uses the self evidence rule. Dennett does not. Of course, there are other forms of misalignment which plague the mind/body debate (Not specific to Dennett and Chalmers). For example, opposing parties frequently enter with different propositions in the ontologi-cal buffer, despite superficial phonetic appearances. It is not unusual for consciously experienced objects to be referred to by one party, and the physical objects themselves to be referred to by another. That is, it is not unusual for different entities to be in each person’s ontological buffer. This is

42 43

a consequence of the fact that nouns, such as ‘cat’, are used to interchange-ably betoken subjective experience of a cat, and the physical cat in the outside world (Velmans, 2009). It is easy to see how a whole cascade of disagreement opens up when people discuss consciousness. There is endless dance of ontological misalignment and application of different epistemologi-cal rules at different times. However, it we slow down and ask the question ‘what’s going on here?’, when the parties disagree, it is quite easy to diag-nose the source of the particular disagreements with the philosophy machine framework above. In the next case study, I look for evidence of the cognitive philosophy machine in a spontaneous spoken debate, rather than a consid-ered, written interchange. Case study 2: Dershowitz vs. Chomsky: Rhetoric, resetting the buffer and ap-peals to source credibility.

There was a debate between Professors Noam Chomsky and Alan Der-showitz on Nov 29 2005 at Harvard University. The title of the debate was ‘Israel and Palestine after disengagement, where do we go from here?’ Both Chomsky and Dershowitz agreed that a ‘two state solution’, with an Israel-Palestine border approximating that proposed at numerous peace confer-ences over the last 30 years was the goal only way to achieve peace (‘The international consensus’). Dershowitz claimed that the obstacle to peace has been Palestinians prioritising the destruction of Israel ahead of the two state solution. Chomsky claimed that the USA and Israel had repeatedly blocked the two state solution, and instead prioritized expansion of Israel’s borders ahead of peace, despite the human cost on both sides. The fundamental dis-agreement was thus about whether Israel or Palestine and blocking progress towards peace. As disagreements go, this is about as nasty as it gets. Let’s see whether it can be understood in terms of the components of the cogni-tive philosophy machine. A transcript of the debate is available on Chom-sky’s Website1 and a recording is accessible on You Tube2. There are aspects of this debate which challenge the models of dis-agreement outlined above. This is partly because the compare, Brain Man-dell, fulfils his role and imposes a preset structure on the debate, and the audience’s questions keep shifting the focus. Moreover, it can be seen that both parties try to discuss what they deem to be most important, rather than evaluating each others proposals systematically. This suggests an even more basic dynamic is going on here. It seems that the struggle to hold the floor takes over from the cognitive philosophy machine. A clear example comes from an interaction between an audience member and Noam Chomsky:

AUDIENCE MEMBER: …I have a question for Professor Chomsky. It seems to me that you left out, in your analysis, the element of violence, psychological and physical, against Israel, against Jews, and it seems to me also that the history that Professor Dershowitz described, a lot of that is dictated by what happened, the terrorism, the wars against Jews, especially considering the immediate history right before the establishment of the state of Israel, the Holocaust and everything that has happened since. So I would like you to ad-dress the effect of -- the psychological effect and the physical effect of war and terrorism on Israel.

NOAM CHOMSKY: Yeah. That’s half of a very important question. The other half of it is: What’s the effect of war and terrorism on the Palestinians?

Now, if you take a look at -- We’re not supposed to talk about that question here, but if you look at them both, you will find that what Benny Morris described is, in fact, correct. The balance of terror and violence is overwhelmingly against the Palestinians, not surpris-ingly, given the balance of forces, and that’s even true -- that’s true right to the present. I mean, for -- you know, for decades, Israel was able to run the West Bank virtually with no forces, as Morris and others point out, because the population was so passive, while they were being humiliated, beaten, tortured, land stolen and so on, just as I quoted.

In this passage, the audience member places the history of violence and terrorism against Israelis in the ontological buffer. Chomsky actually agrees with all the factual claims made by the audience member, but does not take up the invitation speculate about the psychological and physical effect pro-longed violence against Jewish people. Instead, Chomsky fills the ontologi-cal buffer with a series of propositions about the plight of the Palestinians in the West Bank. This kind of competition between agreed facts is a charac-teristic of much of the debate. This can be understood in the current frame-work as resetting the ontological buffer, rather than challenging its contents. However, sometimes the epistemological rules do manifest in the debate. Read the passage below:

NOAM CHOMSKY: As for solutions, pretty straightforward. They were coming close to a solution at Taba until Israel called it off. Negotiations continued, leading to several propos-als of which the most detailed were the Geneva Accords. You can find out what I thought about all of those in print. You can ask Mr. Dershowitz where he supported them in print. The Geneva Accords in December 2002 were accepted by essentially the whole world. Israel rejected them. The U.S. refused even to send a message to the Geneva meetings. But they’re still potentially alive, and American citizens can compel our own government to reverse its program, to accept the international consensus for the first time, and then we’ll be on the way to a solution.

BRIAN MANDELL: Thank you. Briefly, Professor Dershowitz.

44 45

ALAN DERSHOWITZ: I, too, have written about the Geneva Accords in chapter six of my book, and I generally support many elements of the Geneva Accords. I do not support the right of return, that is, the idea that 700,000 or now 4 million Palestinians can demo-graphically destroy Israel.

NOAM CHOMSKY: Which is rejected in the Geneva Accords.

ALAN DERSHOWITZ: It is not rejected in the Geneva Accords. It is not accepted or rejected. It is left for future negotiations.

NOAM CHOMSKY: It is left open, because the Palestinians already --

ALAN DERSHOWITZ: Now, see how you change your view. First it’s accepted, then it’s left open. What is your next position?

NOAM CHOMSKY: Fine. Let’s be precise. They did not say anything about that, because the Palestinians had already at Camp David and at Taba accepted the so-called pragmatic settlement, which would not affect the demographic character of Israel.

ALAN DERSHOWITZ: That is simply false.

NOAM CHOMSKY: If you want to learn about that, read the serious scholarship, like Ron Pundak, head of the Shimon Perez Peace --

ALAN DERSHOWITZ: That is simply false. I can tell you that President Clinton told me di-rectly and personally that what caused the failure of the Camp David-Taba accords was the refusal of the Palestinians and Arafat to give up the right of return. That was the sticking point. It wasn’t Jerusalem. It wasn’t borders. It was the right of return. Now if you believe --

BRIAN MANDELL: Can we move on from there?

ALAN DERSHOWITZ: If you believe that the United States has unilaterally rejected the two-state solution -- that’s what we heard from Professor Chomsky -- that it’s the United States that has rejected the two-state solution, when every modern American president has favored the two-state solution, I say, welcome to Planet Chomsky.

BRIAN MANDELL: OK, if we can hold there…

NOAM CHOMSKY: Now, here’s a simple exercise. You can believe one of two things: the extensive published diplomatic record, which I gave you a sample of and you can find in detail in books of mine and others, or what Mr. Dershowitz says he heard from somebody. Which you can’t check.

Chomsky claims that the reason the ‘right of return issue’ was left out of the Geneva Accords was because the Palestinians had already agreed that there would be no right of return for the Palestinian refugees at the earlier negotiations in Taba. The reason we are to believe this is because it is claimed by Ron Pundak ‘Head of the Shimon Perez Peace [Centre]’. Dershowitz claims that the US president Bill Clinton had told him that, on the contrary, the Palestinian leaders demand the right of return at Taba, and suggests that Chomsky’s contention is therefore false. Chomsky replies by claiming that the ‘extensive published diplomatic record’, a more credible source, than ‘What Mr. Dershowitz says he heard from somebody’. Source credibility is the major epistemological rule used by the speakers in this pas-sage. There is more going on in this debate than the calm formation of propositions and application of the source credibility rule. Both Dershowitz and Chomsky produce discourse tailored to cast doubt on the soundness of each others judgments (e.g. When Dershowitz claims the Chomsky is chang-ing his position). There were occasions when propositions were justified by epistemological rules, but verbal manifestation of the cognitive philosophy machine was often masked by the noise of skilful strategic manoeuvring. In conclusion, the workings of the cognitive philosophy machine are evident in specific disagreements, but when we consider debates as a whole, many other rhetorical devices are evident. A whole branch of psychology, known as Discourse Analysis, has been developed to explore the ways in which speakers espouse their positions and cast doubt the validity of alterna-tive discourses (Johnstone, 2002). In the Dershowitz vs. Chomsky debate, explicitly justified propositions are interleaved with rhetoric and floor hold-ing, which can be explored with discourse analysis. Nevertheless, when we cut through these dynamics, then we sometimes see the simple structure of the cognitive philosophy machine at work.

Conclusion

In this work I propose that each of us is endowed with a cognitive philoso-phy machine. This apparatus has two parts, an ontological buffer and an epistemological engine. The ontological buffer is a working memory store which holds propositions about the nature of the universe. When judgments about the accuracy of the ontological buffer are considered important, epis-temological rules are employed to make the decision. Disagreements can occur via ontological misalignment, where the parties are holding different information in their ontological buffers despite superficial appearances, or by epistemological misalignment, where the parties applying different episte-mological rules to judge the proposition. In case study 1 (Dennett vs. Chalmers), it was clear that both onto-

46 47

logical and epistemological misalignment are frequent problems. Different epistemological rules are employed to judge the same proposition, and sometimes different propositions are being evaluated, despite appearances. However, if both parties evaluated the same proposition with the same epis-temological rules, there would be no ongoing disagreement about. Meta rules could then be employed to decide which epistemological rules should be given the highest weight. However the meta-rules will themselves have no absolute validity. Ultimately, we can achieve internal consistency, but not un-equivocal, absolute insight with the cognitive philosophy machine. This is a fundamental point. In so much as our virtual universe is built by the cognitive philosophy machine, we cannot claim it to be uncontroversially accurate. We can claim that propositions are justified by the ‘best’ epistemological rules, which were carefully employed. But our claim that the rules were the ‘best’ is necessarily relative. All the cognitive philosophy machine can do to make this judgement is employ meta-rules, which are probably controversial themselves. In case study 2 (Dershowitz vs. Chomsky), we saw that the cogni-tive philosophy machine is far from the only mental process which governs disagreement. Often rhetorical devices such as changing the subject (i.e. resetting the ontological buffer) or casting doubt on the opponent’s integrity dominated proceedings. The fact that verbal output reflects many cognitive operations does not bring the existence of the cognitive philosophy machine into dispute. It simply highlights the difficulty of distilling particular systems (such as the cognitive philosophy machine) from the overall output of the highly complex human brain. Given that the cognitive philosophy machine cannot produce absolute truth (as agued in the previous paragraph), it is perhaps unsurprising that people use hegemony and rhetoric to win over their opposition. Making our opponent ‘see the truth’ actually constitutes overwhelming them with an index of consistent propositions and rules before they can overwhelm us with alternatives. Unprincipled rhetorical devices are necessary because of the ultimate limitations of the cognitive philosophy machine.

Additional considerations

There are two final points which can be made about the cognitive philoso-phy machine. These are not essential for understanding the ideas outlined above, but are interesting in their own right. The first point is similarity be-tween the cognitive philosophy machine and the innate structures of the hu-man mind proposed by thinkers such as Kant and Chomsky. Kant proposed that the reason we see the world in three spatial dimensions, and perceive the continuous passage of linear time, is because our minds are innately wired to perceive the world in this way, not because the world really is this