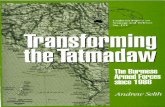

transforming the tatmadaw: - the burmese armed forces - ANU ...

The Maung Aye’s Legacy: Burmese and Moken encounters in the southern borderlands of Myanmar,...

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

2 -

download

0

Transcript of The Maung Aye’s Legacy: Burmese and Moken encounters in the southern borderlands of Myanmar,...

7

The Maung Aye’s Legacy burmese and moken encounters

in the southern borderlands of myanmar , 1987–2007

M axime B outry

Th e Burmanization of the Borderlands During my PhD fi eldwork from 2003 to 2007, I had the opportunity to work in a little-known region of Myanmar, the Mergui Archipelago (see Figure 7.1 ). Indeed, bordering the southernmost coast of the country and leading to the border with Th ailand, its hundreds of islands have been forbidden to any for-eigner since the mid-1970s to 1996, the year of tourism as declared by the Myanmar government. Traditionally a shelter for the Moken sea-nomads (or sea-gypsies 1 ), the Mergui Archipelago has been infi ltrated during the past twenty years by thousands of Burmese coming from Lower Burma. Th ey prof-ited from the new development of Myanmar’s fi sheries industry, progressively “colonizing” the littoral, then the closer islands, always going further south and farther from the continent. I thus witnessed the creation of a new social space, 2 that followed the settlement of thousands of Burmese in the islands and the growing interactions between them and the Moken. Broadly speaking, the Mergui Archipelago has been “Burmanized,” meaning it has been incorpo-rated into a national conception of the territory based on a Burmese

1 . As qualifi ed by missionaries (White [1922] 1997) and adventurers (Ainsworth [1930] 1990).

2 . All through this paper I use the concept of “social space” as defi ned by G. Condominas ( 1980 ), which is “the space determined by the whole set of relations’ systems, characteristic of the considered group,” including the geographic space, the relations to space, time, and the environment, the relations of goods exchanges, communications, kinship, and neighboring, and the relations to the supernatural.

0002069075.INDD 1470002069075.INDD 147 10/25/2013 8:31:31 PM10/25/2013 8:31:31 PM

14 8 at bur m a’s m a rgins

administration supported by the authorities and contained within the national borders enforced by immigration checkpoints, exerting control over the movement of peoples and goods. Th e encounter between the Burmese and the Moken has provoked radical transformations in the Moken society, beginning with the near disappearance of their traditional boats, going hand in hand with their settlement on some islands instead of their nomadic way of life. However, this point of view does not take into account the Burmanization process in itself, understandable only through a temporal and dynamic per-spective. In other words, the concept of Burmanization may encompass two distinct meanings. Th e fi rst and widely accepted one can be understood as the result of a “center-toward-peripheries” 3 process—the integration of a peripheral social space to a wider “Burmese” territoriality within which a kind of “Burmeseness” is supposed to be shared by all its populations. 4 Th e second and generally neglected side of this Burmanization eff ort toward the periph-eries is its negative construction (in opposition to what is not Burmese). Indeed, as Brac de la Perrière ( 2008 : 99) remarks, the exercise of the Burmese hegemony toward the “others” may have side eff ects for the construction of the Burmese identity, that is, the values of the society’s “center” ( Shils 1961 : 117) conveyed during this process may be altered by economic, territorial, and cultural “resistance” ( Rokkan and Urwin 1983 ). Th us, the Burmanization pro-cess embeds as well an acculturation dynamic, allowing integrating techniques, know-how related to a new environment, and also external cultural elements leading to the appropriation of the colonized social space. In this case, Burmanization is also the result of a “peripheries-toward-center” process.

While, in another article, Ivanoff and I have already underlined the theo-retical value of the Moken-Burmese interactions as a possible model to ana-lyze the social segmentation and even the ethnicization processes of some

3 . Among the center-periphery relations models, the one proposed by Rokkan and Urwin ( 1983 ) has been widely used in the study of ethnic minorities’ confl icts with states. Following this model, center-periphery relations are characterized by tensions within three domains (economic, territorial, and cultural); in each domain the central power’s eff orts to maintain a dominion over its nation and populations may encounter resistance, in some cases leading to confl icts. Coakley ( 1992 ) rightly added the political dimension of these center-periphery rela-tions in trying to establish a typology of ethnic management strategies. As Brown ( 1988 ) notes regarding the cases of Burma, Th ailand, and the Philippines, these center-toward-peripheries relations result from the assimilationist character of monoethnic states towards the periph-eries of their intrinsically multiethnic nations that may be viewed as an “internal” form of colonialism.

4 . Its most obvious expression being the multiplication of Buddhist monasteries and pagodas, schools teaching in Burmese, the development of an administrative web between the littoral and the islands and a tighter control on the populations’ mobility.

0002069075.INDD 1480002069075.INDD 148 10/25/2013 8:31:31 PM10/25/2013 8:31:31 PM

Th e Maung Aye’s Legacy 149

parts of “dominant” societies ( Boutry and Ivanoff 2008 ), here I would like to emphasize to the contrary the dynamic and changing character of the Moken-Burmese encounter through life narratives. Life narratives, inscribed as they are in a delimited time span, convey better than any other form of analysis the temporal dynamics and perpetual changes characterizing an individual trajec-tory within a social space. In other words, they are more a matter of processes than established social structures. Consequently, I will focus in this paper on a few self-narratives of both Burmese and Moken protagonists whose life tra-jectories crossed paths in what is now offi cially the la’ngan-hsaloun ” -ywa (“La Ngann Moken 5 village” in Burmese). From their accounts, I will compose the story of this peculiar place, while resituating it within a broader understanding of the Mergui Archipelago’s appropriation (socially, economically, and cul-turally speaking) by a part of the Burmese society, as well as its integration within the Myanmar nation-state.

Indeed, by considering the two facets of Burmanization (from the “center” to the “peripheries” and conversely) there is a way to illuminate the potential link between social and national construction processes, the making of national borders and the transformation of this southern borderland into an extension of the “imagined” 6 Burmese national community. To clarify this point, I may recall some characteristics of the territory’s “nationalization” process caused by the colonization of Burma and Southeast Asian countries. Aft er the country’s independence from the British colonial government in 1948, Burma inherited a territory modeled aft er a Western vision, geographi-cally and precisely delimited by national borders enclosing a national “iden-tity.” Th is combination of territoriality and national ideology constitutes what Tongchai Winichakul ( 2005 )—for instance, writing about the creation of Th ailand as a nation-state—calls the geo-body of the nation. Consequently, as in many Southeast Asian countries, the new Burma state still needed to carry out the transition between what Scott ( 2009 ) calls the “Paddy States’ era” and the post-colonization “Commercial States’ era” (Ivanoff 2011). In the former model, the regimes of power were shaped according to a mandala pattern ( Wolters 1982 ), characterized by a varying hegemony depending on the distance from the center and moving relations, in time and space, with the surrounding political and cultural entities. Th ese entities were themselves sep-arated by interstices and buff er zones absorbing tensions; otherwise confl icts

5 . Hsaloun” is the Burmese exonym given to the Moken, the latter being the ethnonym.

6 . In the sense of Anderson’s “imagined communities” (1983).

0002069075.INDD 1490002069075.INDD 149 10/25/2013 8:31:31 PM10/25/2013 8:31:31 PM

150 at bur m a’s m a rgins

between them may have occurred too frequently. On the contrary, the Southeast Asian countries inherited aft er colonization a functioning based on a centralizing conception of the administrative authority embedded in its national borders, this geo-body absorbing, at least in theory, the former borderlands-buff er zones.

Th e contemporary history of the southernmost region of Myanmar, the current Tanintharyi Region (formerly called Tenasserim by the British) to which the Mergui Archipelago belongs, is inscribed in this transitional con-text. Even if the Tenasserim region was successively claimed and conquered by both Th ai (Siam) and Burmese kingdoms during history, it was never the place for actual integration to the “states,” but rather a buff er zone between them, a theater of regular plundering for military recruitments and a resource for recruiting a workforce to serve the surrounding agrarian royalties. 7 And even aft er independence, the Tenasserim region remained until the 1980s a historical and geographical “interstice” ( Winichakul 2003 ), because of its dis-tance from the surrounding Burmese and Th ai centers of power.

Th e Mergui Archipelago lies along the southern part of the Tenasserim coastline, on a north-south axis. It extends in the north to the littoral town of Dawei and to the South as far as Phuket in Th ailand. Its islands are inhabited, at least since the seventeenth century, by the Moken, a population of sea-nomads of Austronesian origins. In fact, the Mergui Archipelago is part of the wider Malay Peninsula region, including the southern provinces of Th ailand and the north of Malaysia. Even geographically, for White (1922) the Tenasserim marks the fusion between Myanmar and Malaysia, according to its ecological similarities to the latter country. As he wrote, the Myanmar is the country of the peacock, while in the Tenasserim, like in Malaysia, the pheasant dominates (ibid: 27–28). Other animals common in Malaysia, such as the pangolin and the mouse-deer, are found in this region. As far as the fl ora are concerned, the resemblances to Malaysia are signifi cant, with the kanyan for example that supplants the teak, and the presence of zalacca ( Zalacca rumphii ), indispensable for the construction of the kabang , the boat of the Moken sea-nomads. Finally, besides the Moken, the Malays were in the majority of those frequenting the islands of the Mergui Archipelago. Even though the border was negotiated between Siam and the

7 . Th e Tenasserim, due to its mountainous geography, was a refuge for the hunter-gatherers driven away by the progressive dominion of rice farmers ( Labbé 1985 ). Nonetheless, some of the workforce had to be recruited to cultivate the sparsely populated lands of the rising roy-alties ( Reid 1988 ). In the Tenasserim as well as many parts of Southeast Asia, this was a reason for slave hunts and wars that devastated the region ( Ivanoff 2004 ).

0002069075.INDD 1500002069075.INDD 150 10/25/2013 8:31:31 PM10/25/2013 8:31:31 PM

Th e Maung Aye’s Legacy 151

British Empire in the nineteenth century, 8 the entire region remained a transnational borderland with limits situated inside the national territories, that designated cultural and geographic elements more than administrative ones. Consequently, a cultural border existed between paddy states and thalassocracies (maritime realms), rice culture and commerce, continental and insular Southeast Asia. Th is border separated central and lower Burma from the Malay Peninsula, including the south of Moulmein and the Mergui Archipelago, this in spite of the national offi cial border.

Since the beginning of the 1980s, however, the Mergui Archipelago has become a refuge for numerous Burmese, mostly coming from Lower Burma, and thus the theater of an appropriation process of the marine and insular environment, involving both the Burmese and the Moken. Consequently, my point is that the present-day administrative border, marked by Kawthaung and Ranong immigration checkpoints, is as much the result of a social construction as a national one. Th e modern national border between Southern Burma and Th ailand got its meaning primarily from an action of socialization pushing back the cultural “frontier,” here in the sense of Turner ( 1893 ), bet-ween the implicitly wild (non-Burmese) and the civilized (Burmese) terri-tories. For the past twenty years, the Mergui Archipelago has been thus a pioneer front whose progress can be attributed to a handful of Burmese. Maung Aye is one of them. Unfortunately, I could not record his life story fi rsthand, as he died in 1987. However, Maung Aye’s legacy is shared by the founders of La Ngann village, both Moken and Burmese, who undertook the creation of a new space in order to face political, social and economical changes based on a system of structural interactions between the two popula-tions. As a matter of fact, these pioneers, by making some social and cultural “sacrifi ces” in order to withstand their integration into the new Burmese geo-body projected through the military dictatorship, paradoxically helped the national construction of its territory.

Finally, to my knowledge, these voices have remained silent until now. Indeed, life narratives under the ruling Burmese military dictatorship—in place since the Ne Win’s coup d’état in 1962—generally focus on ethnic minority members in confl ict with the central Burmese authority, or the lives of antigovernmental opponents and students who participated in the 1988 demonstrations. So there are only a few life narratives of “ordinary” Burmese, those who tried, less by confrontation than by life choices and by taking

8 . Th e Geographer, 1966.

0002069075.INDD 1510002069075.INDD 151 10/25/2013 8:31:31 PM10/25/2013 8:31:31 PM

152 at bur m a’s m a rgins

advantage of opportunities, to prosper economically and preserve a kind of freedom in a particularly challenging political and economic context. I thus hope to bring a new understanding of the little-known region of southern Myanmar and the reactivity as well as adaptability of this Burmese society through the lives of these entrepreneurs.

Maung Aye, a Contemporary Burmanizing Hero Th e village of La Ngann is situated on one of a group of islands bearing on the British admiral chart 9 the names of Charlotte, Anne, Maria, Eliza and Jane, and forming together the Sisters Archipelago ( Figure 7.1 ). Th e Sisters are at the same latitude as Bokpyin, on the littoral midway point between the towns of Mergui at the north and Kawthaung at the south. Separating Kawthaung from its twin town of Ranong in Th ailand, is the Pakchan River. Th e fi ve Sisters Islands are spread on a north-south axis (98°E longitude), situated bet-ween 11°26́ and 11°19́ N of latitude. Th e Mergui Archipelago islands can be divided into diff erent strings according to their topography and ecology, from big islands surrounded by mangroves close to the continent, to the farther and smaller islands characterized by mountain ranges. Th e Sisters belong to the last category, surrounded by strands fully uncovered during the big tides (on full and new moon days), during which the Moken women collect sand worms, crabs, and shells for their meals as well as for money to exchange for rice, clothes, betel, tobacco, and other necessities.

Let me fi nally introduce the Sisters as a strategic place in the archipelago, distinguishing the Mergui District northward and the Kawthaung District southward. 10 Th e Sisters thus shelter the village of La Ngann, whose name is directly transcribed from the Moken lengan , meaning “the hand,” in refer-ence to the fi ve islands composing this small archipelago. Th e village is now composed of three groups of households ( Figure 7.2 ), spread between three sandy bays, two on Charlotte Island and the other on Anne Island. Th e Meu group (Charlotte) comprises its economic core, a supply point for the fi shing boats coming from the littoral towns, from Kawthaung to Mergui including Bokpyin. Meu is also the land of the Moken potao 11 Poleng, whose

9 . Admiralty chart. Bay of Bengal—Burma, Mergui Archipelago, 1/300 000.

10 . Economically speaking, it accesses these two main ports of the continent as well as serving as a gathering place for the boats coming from these two districts. Administratively, it means also the access to the traders and fi shermen having a license from one of these two places.

11 . In Moken, the term potao designates a leading elder.

0002069075.INDD 1520002069075.INDD 152 10/25/2013 8:31:31 PM10/25/2013 8:31:31 PM

Th e Maung Aye’s Legacy 153

GULF OF SIAM

ANDAMAN SEA

THAILAND

MYANMAR

Tavoy

0 100 km50

Bokpyin

Tenasserim

Mergui

KawthaungKawthaung

Ranong

King

SelloreIsland

Domel

Pu Nala

St Matthews

SistersIslands

Kisseraing

MYANMAR

0,5 1 km0

CHARLOTTE

ANNE

Daké’s village

Gatcha’s village

Poleng’s village - Meu

figure 7.1 Map of the Mergui Archipelago and the Sisters.

0002069075.INDD 1530002069075.INDD 153 10/25/2013 8:31:31 PM10/25/2013 8:31:31 PM

154 at bur m a’s m a rgins

parents—founding ancestors of the Lengan group—died here. On the same island, but separated by a cliff , another bay shelters the Gatcha’s Moken sub-group. Even if here the nomads are more or less sedentarized, 12 this place is inhabited only by Moken, while in Meu the people have intermingled with Burmese. At last, on Anne Island, lives the potao Daké’s group, also mixed with Burmese but in lower proportion.

Th e history of this interethnic gathering begins with the story of Maung Aye, a former Burmese farmer who came in the early 1970s to the Mergui Archipelago from his village of Kyaik Kay Ta, situated on Biluu Island (Chaung Sone Township), in the west off Moulmein’s coast (Northern Mon State). Eventually he died where the current La Ngann village lies. Th e data on his life and his death’s circumstances, collected besides the La Ngann’s vil-lagers (Moken and Burmese) as well as some experienced Burmese sailors of the archipelago, beyond their truthfulness, convey many of the cultural (iden-titary), economic, and political issues peculiar to the premises of the Mergui

Maung AyeMyint Luin

Poleng

Tchi ancestor

Gatcha

Tin WinKin Win

Thein Zan

Daké

BurmeseMokenHalf-cast child

1st wife

2 3 1

1

figure 7.2 Kinship ties between the Moken and Burmese founders of La Ngann.

12 . By sedentarized, I here underline the transformation of the temporary village where the Moken traditionally gather during the monsoon (between May and September) into a permanent village. However, we must keep in mind that even aft er decades of immobility, the Moken are able to go back to a nomadic way of life, as I witnessed of a group sedentarized dur-ing more than twenty years in a northern island (Elphinstone).

0002069075.INDD 1540002069075.INDD 154 10/25/2013 8:31:32 PM10/25/2013 8:31:32 PM

Th e Maung Aye’s Legacy 155

Archipelago’s Burmese colonization. In addition, here I must weave Maung Aye’s life story with that of the Moken before they crossed paths with him and thus before their lives became tied to the Burmese who came later.

Starting in the 1970s, the Burmese began to colonize the northern islands of the Mergui Archipelago, initiating the fi rst steps of the marine fi shing industry in Myanmar. Even if the mobile marine fi shing practices had not yet spread among the Burmese people who were culturally “far” from the sea ( Robinne 1994 ), the northern islands (such as King, Kissering, and Domel) saw the installation of hundreds of Burmese accompanied by Chinese entre-preneurs ( Boutry 2007 ) in the development of coastal fi shing techniques already in use in the inland waters of the country. With them also came the pearl farms, the Burmese administration, and the military bases, altogether driving away the Moken. Hence the Moken from Lengan used to be part of the same Moken subgroup identifi ed as the Badeng subgroup which fl ed from the more northern island of Domel. Th e group was itself divided into four fl otillas during the dry season: Pasun, Tahun (to which Poleng and Gatcha belong), Palang (Daké’s fl otilla), and Khethè. Th e Sisters Islands were already in their nomadism area and frequented by the three groups currently residing there. Around twenty years ago, Poleng’s parents came to “settle” in Lengan as their main island of residence during the monsoon. Poleng expresses her belonging to Lengan saying, “My parents died here; they are the ones who planted the trees [coconut, jackfruit and betel nut trees].” Indeed, her father, the shaman of the group used to perform the spirit poles ceremony ( bo lobung ) in Lengan, marking the passage between the nomadic dry season and the sed-entary rainy season. Th e other two groups (Daké’s and Gatcha’s) went to dif-ferent islands, from Bushby (near the Sisters) to Pu Nala (Lord Loghborough) and Jelam (St. Matthews), next to the Th ai border. While moving to the southern half of the archipelago, all these Moken came under the protection of the most infl uential tokè of this region, a man of Sino-Th ai origin living in Ranong (in Th ailand), called Uyé. 13 Maung Aye was working for him.

Tokè is a term of Chinese origin employed from south Burma to Indonesia, including Th ailand and Malaysia, which designates a patron-entrepreneur. Traditionally, the tokè has been central to the preservation of the Moken nomadic way of life. Th e relationship between the tokè and his Moken group lies in the necessity of the nomads to acquire rice, the basis of their diet and paradox of an insular population that only cultivates the cereal for ritual

13 . Uyé is the transcription of the name given by both the Moken and the Burmese.

0002069075.INDD 1550002069075.INDD 155 10/25/2013 8:31:32 PM10/25/2013 8:31:32 PM

156 at bur m a’s m a rgins

purpose. So the Moken exchange their products collected on the strands or by diving (pearls, mother of pearl, shells) with the tokè for rice, clothes and other consumable goods. Th e founding myth of the ethnic diff erentiation of the Moken is the Gaman epic poem ( Ivanoff 2004 ). Gaman is the Malay civi-lizing 14 hero, who will provoke the passage from “yams to rice” for the Moken. Th e epic poem conveys Islam’s beginnings in Southeast Asia that, linked to slavery, will lead to the “nomad choice” ( Benjamin 1985 ): to “roam” in the islands, “eat and spew out the sea” on board the kabang (the traditional Moken boat) and be eternally dependent upon the sedentary societies to acquire rice for their products ( Ivanoff 2004 ). So the tokè is the organic link connecting the Moken to the “rest of the world.” Practically, the tokè is more oft en of Chinese origin, whether he be Sino-Burmese or Sino-Th ai. But with the involvement of Burmese traders and entrepreneurs fl eeing from Central and Lower Burma—an always worsening political context—the interrelation bet-ween the Moken and their tokè has suff ered drastic transformations.

Many of the Burmese fi shermen and boatmen sailing in the archipelago say that Maung Aye fl ed from his village, as he was wanted by the military, to fi nd refuge in Th ailand. During this period, the border between the two coun-tries was easy to cross and he then became one of Uyé’s brokers, trading Moken products as well as other resources (such as fi sh and timber). He spent his time sailing throughout the Mergui Archipelago to buy valuable fi shes and acquired a good knowledge of the islands’ network, encountering Moken from time to time. Around 1975, he “took” a Moken wife 15 named Maket, who belonged to the Domel Moken group that was sailing around the Sisters

14 . Gaman provoked the Moken fl ight toward the sea by committing adultery with the queen’s younger sister, Ken. Th e queen condemned Ken and her people to be drowned ( lemo in Moken), giving the ethnonym (le)mo ken . Gaman probably followed the route of the slave mer-chants to the archipelago and with them came the Islamization of South Th ailand. Pelras ( 1985 ) interestingly notes that the Bugis, another maritime people of Sulawesi who, unlike the Moken, adopted Islam between 1605 and 1611, may have been converted through the deviation of their founding epic poem La Galigo . Th e Muslim muballig , trying to convert the Bugis, used their traditional “cultural hero,” Sawbrigading as “a kind of prophet avant la lettre who, before his descent to the Underworld, announced the coming of Islam” (Pelras 1993: 144–145).

15 . Yu hta: de in Burmese, a way to diff erentiate this act from the more formal wedding, mingla saung . Despite the fact that most of the Burmese entrepreneurs who fi rst came to the archi-pelago had a Burmese wife on the continent, they contracted alliances with the Moken due to their tokè’s role. Progressively, these alliances became a strategic necessity to appropriate the know-how and acquire legitimacy on the islands, according to what I called a “cultural exogamy” (see Boutry and Ivanoff , 2008 ). In another essay ( Boutry 2011 ), I underlined the importance of these alliances according to the clanic organization of the Moken in inducing a hierarchy among the insular Burmese (notably their potential to enlist the Moken workforce in their business), profi table for the one married within the Moken founder ancestor’s lineage.

0002069075.INDD 1560002069075.INDD 156 10/25/2013 8:31:32 PM10/25/2013 8:31:32 PM

Th e Maung Aye’s Legacy 157

Islands. In spite of this alliance, Maung Aye remained a broker and also made his home in King (Kyunn Su in Burmese), an island close to Mergui town and unfrequented by the Moken. At this time the alliances contracted by the Burmese with the Moken were as much opportunistic as strategic for the Burmese. Indeed, a Moken group traditionally gives away one of its girls to ensure the tokè’s fi delity. But in the Burmese perspective of profi ting from the pioneer front’s resources, it was also a way to acquire, on the one hand, a kind of legitimacy for use of the territory 16 and, on the other, a better knowledge of this new environment. On King Island, Maung Aye bought a fi shing boat to work in the archipelago, while continuing exchanges with the Th ai market. From Mergui to Th ailand, Maung Aye thus fully benefi ted by the archipela-go’s resources that were, at that time, still underexploited and being mainly of benefi t to Th ai industries. During the 1980s, the Sisters Islands already consti-tuted a strategic place between two social landscapes: the more and more Burmanized northern part of the archipelago—protective and paternalistic and supported by a Chinese presence—and the southern part under the infl uence of Th ailand’s economical development plans 17 . So the Th ais used their Burmese networks in what constituted a pioneer front between Th ailand and Burma that profi ted from most of the archipelago’s resources, including timber. Th at is how Maung Aye brought a team of seven Th ai workers to the Sisters Islands in order to extract timber. Th ey were working illegally and so was Maung Aye, as he was still wanted by the military. In 1987, when he had left the Th ai workers in the islands, a tragic event occurred between them and the Moken group of Gatcha. Some Burmese say that one of the Th ais raped a Moken woman. Tin Win, a Burmese who was working for Maung Aye and is currently living in La Ngann, tells that the Th ai workers’ group fl ed when they saw a navy boat approaching the islands, causing in their fl ight, the death of a Moken child. Still, according to Tin Win, Gatcha would have hired the ser-vices of a well-known Malay “pirate” ( pinlè dat’bia ) named Mada in order to kill Maung Aye, whom the Moken held responsible for this tragic event. Even if it appears improbable that the Moken ordered such an act, this part of Maung Aye’s story underlines one of the Burmese colonization’s main issues—the control over the archipelago’s resources—and the turning point in the

16 . A territory notably disputed by the Malays, see infr a .

17 . In 1961 the fi rst NESDP (National Economic and Social Development Project) was imple-mented, aiming at industrializing Th ailand. It included notably the development of infrastruc-tures and substitution industries. In Southern Th ailand, rubber cultures, fi shing industries, and later tourism constituted the main development’s axis of the NESDP. Th is process is currently in its tenth phase ( Kittaworn et al. 2005 ).

0002069075.INDD 1570002069075.INDD 157 10/25/2013 8:31:32 PM10/25/2013 8:31:32 PM

158 at bur m a’s m a rgins

region’s history—the beginning of an external Burmese hegemony. Indeed, a colonial offi cer remarked about the Mergui Archipelago more than 150 years before:

Th e marauders infesting the islands [are] mostly Malays […] I have information of there being no less than 48 of them from Penang, Queda and Setool amongst the islands. 18

It even appears that Mada was also coming from Penang. It is worth recalling here that besides the Malay, Th ai and Chinese entrepreneurs were also seeking some control over the archipelago’s resources. In this sense, the Mergui Archipelago always remained a “peripheral” region, favoring a multiethnic composition for the resources’ exploitation; even the British, when the Tenasserim became a protectorate in 1824, tried to fi nd ways to maximize profi t from the valuable goods extracted from the sea as well as the islands’ forests. But they could never gain total control of the economic networks and in fact were obliged to rely on the local entrepreneurs (Chinese and Malay). Th ey preferred to entrust them with exploitation rights and tax them directly without interfering in the production ( Boutry 2007 ). Th is is the main diff erence, as we will see, with the Burmese appropriation of the archipelago, as they aimed to progressively “infi ltrate” the territory and its resources’ exploitation.

Th en Maung Aye was killed on the July 14, 1987 by one of Mada’s hench-men, Plan Lo, with the help of some Moken from Gatcha’s group. Nevertheless, Maung Aye’s death became the founding act creating lasting interrelations between Burmese entrepreneurs from Kyaik Kay Ta village and the Domel Moken subgroup, establishing them as precursors of Mergui Archipelago’s Burmanization.

From the Pirates to the Military Here begins, properly speaking, the story of the La Ngann village’s settlement. Th e life stories of its founders will bring us closer to understanding the individual choices people made according to the diff erent social contexts and situations in which they found themselves, in relation to the nationally evolv-ing political context during the past twenty years.

18 . Commissioner of the Tenasserim Division ( 1916 : 56).

0002069075.INDD 1580002069075.INDD 158 10/25/2013 8:31:32 PM10/25/2013 8:31:32 PM

Th e Maung Aye’s Legacy 159

Tin Win is a cousin (second generation) of Maung Aye, also born in Kyaik Kay Ta. He heard in 1986 of Maung Aye’s business in the archipelago and then came to the Tenasserim. He fi rst travelled on his own sailing freighter that he used to charter, shipping rice between Pegu (Bago) and Tavoy (Dawei) in order to reach Mergui. From there he went to Maung Aye’s house on King Island to take a Moken boat sent by the latter that brought him to the Sisters Islands. He stayed there one season before going back to King Island, where he also built a home. He had not actually decided to live in the Sisters Islands, but was looking forward to developing fi shing activities from King with a des-tination of the Th ailand market. He says that if Maung Aye had lived, he would probably have returned to Mon State, delegating his business to a trust-worthy person. But when Maung Aye died, Tin Win came again to the Sisters to take care of his family and business. Maung Aye had three daughters from his alliance with his Moken wife, Maket. Two of them came back to Chaung Sone Township where they married Burmese men. Th e younger one, bearing both Burmese and Moken names (respectively Th a Zin and Cho), was still a child at this time, so she stayed in Daké’s Moken group. She is currently staying in Poleng’s part of the Lengan village (Meu) and is married to a Moken man. Her Burmese name is no longer used, except by Tin Win. From these two opposite trajectories of Maung Aye’s descendants arose the unpredictable consequences of the Burmese-Moken encounter in this period. On the one hand, the Burmese migrants were exploring ways to compensate the always worsening economic conditions on the mainland and in return, had no plan to settle defi nitively in the islands; on the other, they naturally contributed to the “renewal” of the Moken society that traditionally used to intermarry with outsiders, principally Burmese in the north and Th ai in the South. 19 It is only within the past twenty years of Burmanization, beginning with Maung Aye’s followers, that the Burmese found a way to develop a form of resistance against the state’s integration through their settlement in the islands.

Tin Win in the meantime took a Moken wife from Daké’s group. Th en one of his cousins (fi rst generation) Khin Win, who also came from Kyaik Kay Ta, visited him in 1987. Except for Tin Win, he remembers that there were no Burmese living in the Sisters Islands and Lengan was still a temporary Moken village. During the monsoon, Daké’s group of twelve nuclear families

19 . Th e Moken alliances obey an exogamic rule, obliging the young males to fi nd their wife in the closer subgroups although they could go to farther ones. Consequently, in most northern and southern subgroups, the Moken girls frequently accepted an alliance with foreigners, and their children were most of the time integrated into the fl otilla.

0002069075.INDD 1590002069075.INDD 159 10/25/2013 8:31:32 PM10/25/2013 8:31:32 PM

160 at bur m a’s m a rgins

(i.e., twelve kabang composing the fl otilla), was staying in the eastern bay of Anne Island. Daké tells that his parents left the island a long time ago for Lengan with fi ve other ebab (“elders”). But at this time their island of residence was Domel. Like Poleng’s father, Daké’s was also a shaman. Around twenty years ago when his father died, Daké went to Lengan accompanied by Poleng. However, the Moken’s timeframe remains quite uncertain. Poleng tells that “Daké came to the Sisters because of his parents’ death; he did not have the bravery to stay in Domel.” Despite the sacralized link between Poleng and Lengan that made her the potao of the new Lengan Moken group, Daké insists he also planted trees there a long time ago, thus claiming his founder role or at least his legitimacy as a Lengan potao. It is a characteristic of oral literature that societies always rewrite history, a fortiori for the Moken who maintain genealogic amnesia beyond two generations. It is a way to preserve their ethnic identity and its cultural traits (a clan organization based on ances-tors’ islands, exogamy, and uxorilocality) when facing exterior constraints (sedentarization policies, forced relocations, and Burmese colonization of the islands). However, Daké abandoned the spirit poles’ ceremony aft er he went to Lengan, thus implicitly accepting his subordination to Poleng’s group.

Khin Win (Tin Win’s cousin), while coming for holidays, encountered Daké’s group. He fi nally stayed with Tin Win, attracted by potential oppor-tunities to get richer than he would have with his former work as a farmer. Like Tin Win, he later set up a broker business between the “inexhaustible” resources of Myanmar and the always increasing purchasing power of Th ailand. Less than six months aft er his arrival, he married Daké’s daughter who was fl uent in Burmese as she had worked as a housemaid for a Burmese family in Yangon. Indeed, in the 1980s, some Moken were sent by the Myanmar author-ities to participate in an ethnic festival that occurred in Yangon. Daké’s daughter was then taken in by a Sino-Burmese family who taught her the Burmese language before sending her back to the Mergui Archipelago’s islands. Khin Win recalls that the Mergui Archipelago was very dangerous at that time. While the 1988 demonstrations had few repercussions in the archi-pelago, avoiding the pirates was still as dangerous as facing the rising Myanmar army. So the Moken as well as their Burmese followers used to put out their fi res by night and listen to the engines echo; indeed, the Moken are able to recognize a boat just by its sound, such as when it belongs to a well-known person or common navy boats. And in any case, the entire group was always ready to fl ee to the forest and abandon everything. But even taking such pre-cautions was not enough to prevent the death of Khin Whin’s parents, who had joined him later on, and they were killed by night by marauders in this

0002069075.INDD 1600002069075.INDD 160 10/25/2013 8:31:32 PM10/25/2013 8:31:32 PM

Th e Maung Aye’s Legacy 161

same place in Lengan. Since then, Khin Win always keeps a homemade sword in his house.

According to Ivanoff ( 2004 : 330), the Malays were the fi rst to settle on the Tenasserim’s littoral at least as far as the town of Bokpyin and in the islands. Coastal fi shermen on the littoral, they reproduced the village and economic structures of the Malay Peninsula (the most important settlement is still to be found not far from Kawthaung, in the village of Pulotonton). In the islands they specialized in piracy, however to a lesser extent than islands in the Malacca Straits. 20 Th e Mergui Archipelago’s pirates were likely at the extreme edge of the slave raiding that was perpetrated in all the Malay Archipelago. 21 Still, according to Ivanoff ( 2004 : 330), the Malay are closely associated with slave raiders and merchants; in Moken, the term djuun points both to the action of capturing slaves and the fact of being Malay.

Shortly aft er the other Burmese, Th ein Zan arrived in the archipelago in 1988. His brother-in-law—his fi rst Burmese wife’s brother—was working for Maung Aye and had a Moken wife. As Maung Aye before and Tin Win later, he sailed in the entire archipelago from this time to the defi nitive settlement of Lengan village (2003). He once settled in Ye Ken Daw (in the northern part) and established another contact point with Lengan; indeed, later on, many Burmese would come from this island to settle in the new village of La Ngann. During his journeys throughout the archipelago, he took a Moken girl from the Domel group which was in Pu Nala Island (Ma Gyon Galet in Burmese) at that time. Th ein Zan recalls that in 1989–1990, the military made an attempt to drive away the Burmese from Pu Nala, as they were growing in number and suspected of sheltering some antigovernmental groups. Indeed, aft er 1988, many Burmese fl ed toward the south of Myanmar and a large number of students crossed the border to Ranong to take refuge in Th ailand. And later on, from 1988–1991, the Th ai prime minister’s new political orien-tations toward Myanmar, known as the “Chatichai’s buff et (i.e., eat all you want) government” ( Chachavalpongpun, 2005 : 65), favored loose forms of control over this territory, since the Burmese government was in negotiation with its Th ai counterpart to profi t from this resource-laden region. In addition, it helped to settle internal political matters. For instance, some students who fl ed to south Th ailand aft er taking part in the 1988 demonstrations were

20 . For a history of piracy in Southeast Asia see Warren ( 2002 ) as well as Frecon (2008) and Liss ( 2003 ) on its contemporary developments.

21 . See Endicott ( 1983 ) and Condominas ( 1998 ).

0002069075.INDD 1610002069075.INDD 161 10/25/2013 8:31:32 PM10/25/2013 8:31:32 PM

162 at bur m a’s m a rgins

“traded” by Th ai offi cials in order to obtain marine concessions in the Mergui Archipelago.

Consequently, during the 1990s, to become an entrepreneur sailing in the islands looked like a life choice that promised new spaces of expression. And like the other Burmese, Th ein Zan, was forced to move together with his Moken group, oft en hiding from the increasingly present Myanmar author-ities. Indeed, Th ein Zan was part of this Burmese generation willing to settle alongside the Moken to develop their activities and economic networks, but without necessarily moving with them around the islands. Despite the national will to control and integrate this region into the Myanmar’s territory, the Burmese navy (as all of Myanmar’s army corps) was deprived of practical means to exert its power on all the islands. Th ey thus oft en requested both Moken and Burmese fi shing boats for their trips through the islands, also asking for fuel and even money. Th us the military replaced in many ways the former pirates, reminiscent of the “social pirates” described by Liss ( 2003 ), driven to perpetrate acts of piracy as a result of the widespread poverty in the coastal societies of Southeast Asia. 22

Finally, the fi rst governmental attempts to control the archipelago pushed Th ein Zan and the other tokè to develop new strategies in order to preserve a space of economic and social freedom. Th ey reacted by being even more mo-bile, following their Moken groups to whom they became more and more tied. Th en, when Th ein Zan’s fi rst Moken wife passed away, he took a wife from Daké’s group, bringing him back to the Sisters Islands. Undoubtedly better able to perceive the transformations happening in the archipelago, he was the fi rst to ask for the defi nitive settlement of the Burmese tokè and their Moken groups in the Sisters. But this would have not been possible without Poleng’s consent and, thus, without Myin Luin’s presence within her group.

Th e Moken and the Burmese Borderland’s Construction Myin Luin is in fact the only Burmese who is not directly related to Maung Aye’s story. However, he is inseparable from the La Ngann village’s history.

22 . Th e role of the military in acts of piracy is reinforced by the context of illegal fi shing in foreign territorial waters (EEZ), such as the Th ai fi shing boats in the Mergui Archipelago. As noted by Liss ( 2007 ): “Additionally, the perpetrators of attacks are in some cases members of the military, navy, or marine police. For rogue security personnel, such attacks are easier to conduct if a boat happens to be caught fi shing illegally in waters under their jurisdiction. Th e distinction between outright pirate attacks by members of local authorities and the legitimate collection of ‘fees’ for illegal fi shing are somewhat blurred in these incidents.”

0002069075.INDD 1620002069075.INDD 162 10/25/2013 8:31:32 PM10/25/2013 8:31:32 PM

Th e Maung Aye’s Legacy 163

Coming from Moulmein, he went to Kawthaung in 1989, at this time hardly a little border town, to work as a fi sherman on a Burmese boat. He discovered the Sisters during his fi shing campaigns. In 1993, he left his work to become exclusively the tokè of Poleng’s Moken group, contrary to other Burmese who always kept other fi shing businesses and consequently attracted Burmese workers to the islands. In 1994, he took Poleng’s daughter as a wife. In the meantime, he started to learn Moken, as Maung Aye and Th ein Zan did before him. From then on, to 2003, he and the Burmese belonging to Maung Aye’s network crossed paths, but without any economic exchanges. Nevertheless, they faced the same militarization process of the archipelago. Th e Mergui Archipelago also began an economical development stage, managed at the national level: a pearl farm was created with the help of international funds (from Japan notably) near the Sisters (on Pearl Island, Pulay Kyun in Burmese) while, in 1996, the Salon Ideal Village was organized in Pu Nala. Indeed, the designation of 1996 as the year of Myanmar tourism brought along new pol-icies aiming to settle all the Moken from Myanmar on this island and willed, as a counterpart, to drive the Burmese away. As Ivanoff ( 2004 ) pointed out, the nomads sometimes suggest in their lifeways a negative image of an accumulation lifestyle to the sedentary populations, notably by displaying that the sedentary model is not the only viable way of living. For this reason at least, everywhere the nomadic people have been subjected to sedentarization policies, and dur-ing recent decades the Moken faced many attempts to put them in camps. But the nomads’ reactivity and strong identity pushed them to fl ee, as the military control over the Mergui Archipelago’s islands remained too weak to enforce the situation. Still, the village of Pu Nala is populated by a Moken subgroup, and as on many other islands, intermarriages with Burmese are numerous among this group. As the Myanmar authorities continue to see this village as an ideal Moken place, they regularly try to relocate the Burmese to other places, but with no success. As Taylor explained (1998: 43), the former military Burmese government portrayed itself as the legitimate protector of a nation-hood that continuously fought to maintain the nation’s unity and integrity. In this process, the government willingly emphasized the ethnic diversity of the nation, implicitly a threat against unity, while trying to suppress this diversity by a process of Burmanization of the “other.” 23 In the meantime nationhood

23 . Despite the political shift in 2010 toward democracy, the recent strikes in Kachin State between the army and the KLO as well as the latent confl ict between Muslims and Buddhists (fi rst in Rakhine and now all across the country) suggest that the military may still use the same strategy to hold on power over the country.

0002069075.INDD 1630002069075.INDD 163 10/25/2013 8:31:32 PM10/25/2013 8:31:32 PM

164 at bur m a’s m a rgins

was enhanced by a series of cultural festivals (Akha new year festival, Naga new year festival, and Kachin Manaw festival, among others); in this way the former government once tried to integrate the Moken with the Salon Traditional Festival held in the Mergui Archipelago in 2004. Gatcha and a few members of his groups were at the event and forced to participate. While the military chose the prettiest Moken girls to perform “traditional dances” (that the Moken actually do not have), the men had to sculpt spirit poles, in Gatcha’s words, “according to Burmese standards of beauty” (i.e., fi gurative ones with strong hips, round eyes). But once the festival was over, they could not abandon them, albeit they were made poorly and impregnated with a Burmese identity, so Gatcha had to bring them back to the Sisters. Th is event caused a lot of trouble among the Moken group and the local actual spirit poles ceremony was interpreted according to bad omens.

But upon each attempt to settle the Moken, they fl ed through the archi-pelago’s islands, and Myin Luin and Poleng’s groups were forced several times to change their monsoon residence. Nonetheless, they took advantage of this pioneering age to weave their economic webs in close relation with the Moken activities. For example, Gatcha’s group once went to live in Pu Nala, where one of the potao’s brothers is still living and whose tokè is a friend of Myin Luin. Th ese two tokè still continue to work together to bring their produc-tion to Th ailand, exchange information concerning prices, and so forth. 1996 also saw the setup of a new navy base in Mergui to control the archipelago.

Poleng, Daké, and Gatcha’s group regularly tried to stay around the Sisters but were regularly forced to depart. Th e presence of the Burmese, at least among Daké and Poleng’s group, was also attracting more attention from the Myanmar authorities during the period dedicated to the dual process of Burmanization and “folklorization” 24 of the archipelago and its populations. During this phase of forced mobility, Myin Luin and the other tokè were keep-ing up a traditional relationship with their Moken group, accompanying them during the dry season. However, the progressive military takeover of the archi-pelago and the segmentation policies among mixed communities lead Th ein Zan and Myin Luin to react and join forces. Leaving Maung Aye’s network of Burmese workers, periodically installed on Anne Island with the Daké’s group, Th ein Zan joined Myin Luin in Meu (Charlotte Island) to persuade him, as

24 . By “folklorization,” I point out the national policies which purpose, under the name of offi cial recognition, to empty an ethnic group of its sociocultural, dynamic. and complex iden-tity to the profi t of static cultural traits generally exhibited during national festival and ethnic days.

0002069075.INDD 1640002069075.INDD 164 10/25/2013 8:31:32 PM10/25/2013 8:31:32 PM

Th e Maung Aye’s Legacy 165

the tokè and son-in-law of Poleng—the only legitimate Moken potao of the Sisters—to defi nitely settle in Lengan and make a request for the village to become offi cial. Th erefore, the new policy concerning the Moken—the prem-ises for their recognition and “folkorization” by the Burmese government—paradoxically encouraged Th ein Zan as well as the other Burmese to engage into deeper interrelations with the nomads to preserve the economical niche they had been trying to build since the 1980s.

Th e fi rst attempt to make the Lengan’s settlement offi cial was in 2000, involving the Tenasserim Division commander. Th ein Zan says that “aft er living with the Moken for a while, when the military came and looked at them, I feel some pity . . . ” Th at is why he requested from the chief of the mil-itary base 224 from Bokpyin the authorization to settle in Lengan, profi ting by a visit from a Malaysian minister in the Tenasserim Division. Th ein Zan designated himself chief of the village and waited to become the offi cial one. As he says, at that time, none of the Burmese residing with the Moken group wanted to shoulder this responsibility, because of the navy’s military that came regularly, eating and drinking at the villagers’ expense. Once satisfi ed, and oft en drunk, they would fi nally leave the village, sometimes aft er fi ring some shots, possibly killing a dog or two.

However, the village was offi cially recognized only three years later, in early 2004. Th ese three years represented the time necessary to stabilize the village’s economy and for the authorities to confi rm the Burmese entrepre-neurs’ will to settle in Lengan for the long-term. Th is determination was given concrete form through the construction of a Buddhist monastery and a pagoda. Th is worthy action also served as a precursor to the Burmanization of a territory. So in 2004 the immigration offi cers came to take a census of the inhabitants, both Moken and Burmese, as residents of the new La Ngann salon village , intermingling its double Burmese and Moken identity. La Ngann was thus linked to the Bokpyin Township. Th is census also served to deliver National Registration cards to the Moken ( Table 7.1 ). Th is is not the fi rst time that Burmese authorities delivered such papers to the nomads. Some of them had already received identity cards on Ross Island (in the northern part of the archipelago) before the 1990s ( Ivanoff and Lejard 2002 : 107).

On Ross, the Burmese authorities chose a patronymic name for the Moken, while the nomads usually defi ne themselves according to their ancestors, who are related to a geographical origin. In addition, their society is organized according to a strong matrilineal tendency (ibid. 107). In La Ngann, the Moken name is simply preceded by the particle U” that distinguishes in Burmese a male subject from a female ( ma’ ). In both cases, the Moken are

0002069075.INDD 1650002069075.INDD 165 10/25/2013 8:31:33 PM10/25/2013 8:31:33 PM

166 at bur m a’s m a rgins

identifi ed as hsaloun” , the Burmese exonym implicitly refusing the nomads their identity. It is worth noting that the only identity acknowledged to the Moken within Myanmar’s national ideology is the one of “wild people” ( lu yaing” ), opposing their material destitution to the wealth of the sedentary societies, justifying the latter’s superiority. Th is point of view is shared by most of the Burmese living on the continent that may know of the Moken’s existence, and it still prevailed when they received their ID cards on Ross Island. Before 1990, the interrelations between Moken and Burmese were not widespread and did not yet represent an issue for the latter. Th us the Moken could still be identifi ed according to their “wild” traits, distinguishing them from the civilized Burmese. Consequently, they were identifi ed as “divers” and were even recognized as having a “traditional” religion.

But in the later Burmese colonization process of the southern part of the archipelago, the Moken took on a crucial role for the Burmese. Myin Luin likes to recall the Moken’s knowledge regarding the insular environment, whether to fi nd marine or forest resources or water springs. As Th ein Zan says, “We settled in Lengan because we were used to this place and because the Moken are tied to this place.” And so are the Burmese. Still, according to Th ein Zan: “It is not like I could not go back to my native place. It is not the travel’s cost, isn’t it? It is simply that I have no reason to go back home.” Hence the Moken of La Ngann have been recognized as hsaloun” of the Union of Myanmar and a so-called population of “Buddhists fi shermen” (fi shermen and sedentary as opposed to divers and nomads). Indeed, being “Buddhist” offi cially, even as “hsaloun”” and not Burmese, signifi es a place for the Moken in the Burmese nation’s geo-body. And in regard to the children coming from interethnic alliances, they all became Burmese. Th ein Zan says accordingly: “I pointed out my children as Burmese, of course . . . half Salon and half Burmese is what they are. But on the papers, they should be Burmese.” Undeniably, giving them the Burmese ( bamar ) ethnic association is to entrust

Table 7.1 Burmese National Registration Cards Delivered to the Moken

Ross (before 1990) La Ngann (2004)

Name Mahen Udola U Daké Ethnical belonging Salon Salon Religion Traditional Buddhist Husband’s occupation Diver Fisherman Wife’s occupation — Housewife

0002069075.INDD 1660002069075.INDD 166 10/25/2013 8:31:33 PM10/25/2013 8:31:33 PM

Th e Maung Aye’s Legacy 167

them with more choices and opportunities regarding their future, whether in the islands or on the continent. 25

To summarize, this shift of policy toward the Moken underlines, on the one hand, local choices made by the Burmese leaders to integrate the Moken within the building of their new social space; and on the other hand, a national decision to leave the borderland’s destiny in the pioneers’ hands. For instance, since 2004 the Moken ceased to be an argument for the archipelago’s tourism development: the travels allowed in the islands were reduced from one month to ten days and the visas issued from the Kawthaung checkpoint decreased to fi ft een days. From this time onward, we can see more clearly the duality of the Burmanization process I described in the beginning of this paper. Or, how do the Burmese, by fl eeing from the oppressive Burmese State, contribute to its expansion through the borderland? In addition, despite being more and more offi cially integrated to the Burmese nation’s geo-body, our Burmese founders of La Ngann will have to struggle harder to maintain their privileges in the economic niche they built together with the Moken.

Since 2004, offi cial recognition of the La Ngann village attracted a lot of Burmese, coming both from Maung Aye’s place of Kyaik Kay Ta and Th ein Zan’s network from Ye Kan Daw. While in 2004 the village counted only 18 households, in 2007, it exceeded 40. Th e tokè have progressively expanded their houses; the fi rst corrugated iron roofs have appeared; some of the younger Moken also rebuilt their houses, while most of the elders tended to withdraw into their homes as the number of Burmese passing through their particular street intensifi ed: from a bar to another, from the water spring to the house, from the bar to the pagoda. Th ein Zan remained the village’s head until 2006. During this time he had to negotiate the military’s visits as well as fi ghts between the Burmese fi shermen coming from the littoral, gathering in this place during their time off , mostly drinking alcohol and singing karaoke. He also managed the newcomers’ settlement, sometimes refusing some if he saw them as potentially disruptive to the well-being of the community. One of his criteria was based on their religion. He preferred them Buddhist, even if actually he brought some of his Karen workers to settle in La Ngann. In fact, this choice was aimed at facilitating the offi cial recognition of the village by the Myanmar authorities, for whom the Burmanization should be done through Buddhism and Burmese education. A fervent Buddhist, he orga-nized the collection of funds among his Burmese relations throughout the entire archipelago to build the monastery and the pagoda.

25 . Ma Th ida in this volume refers to a similar story on this aspect.

0002069075.INDD 1670002069075.INDD 167 10/25/2013 8:31:33 PM10/25/2013 8:31:33 PM

168 at bur m a’s m a rgins

On the other hand, for Myin Luin, the fi rst priority was the construction of a school, since education for the Moken was vital to their integration into the newly forming insular societies. We used to talk for hours about the possibility of creating a free school for the nomads, and during my fi eldwork, he oft en asked for my advice on teaching modalities for the Moken. Th e content of his discourses centered on the inevitable confrontation between the Moken and the Burmese, meaning the growing diversity of their economical relationships progressively transitioning from the traditional relationship of the Moken to their tokè. According to Myin Luin, in this context, the Moken children’s schooling was also inevitable, but instead of transforming them into Burmese children it might aim to provide them with tools (Burmese language, calcula-tion) to better equip them for this confrontation. Myin Luin, despite his deep desire to preserve Moken culture, does not ignore the deep changes that the development of the marine fi sheries and the creation of new insular Burmese communities holds in store. He was thus the fi rst driving force behind the school project in La Ngann. However it needed to wait for completion of the process that would give the village its offi cial status and the benefi t of a teacher delegated by the government. Moken schooling, now in eff ect, may be seen as the completion of the Burmanization process of the archipelago, from the “center.” However, it especially allowed for separating religious matters from those of education for the Moken. Indeed, as in the rest of Myanmar, in the absence of a school, education is entrusted to the monk teaching in the mon-astery. Consequently, before the construction of the La Ngann School, the Burmese, Moken-Burmese, and few Moken children were sent to the monas-tery and consequently were directly subjected to the Buddhist infl uence.

Once these two main projects were completed, Th ein Zan decided to hand his position over to a previous worker of Maung Aye named Myin Th ein who had returned to the Sisters aft er years of living in Kawthaung. Th ein Zan partic-ularly wanted to concentrate on his economic activities, free of his chief ’s responsibilities. However, one year aft er Myin Th ein has taken offi ce, Th ein Zan had not told the Bokpyin authorities about this change, doubting his colleague’s competence and eventually took back his position when the fi rst elections at the village tract level occurred in 2013. For one thing, Myin Th ein did not always question the village’s layout with the last Burmese settlements, leading to unequal land distribution. Th e latest Burmese arrivals tended to build enor-mous houses far exceeding their actual needs. In addition, the Burmese new-comers did not always respect the tacit deal made with the Moken that has been in place since the village’s origins. Indeed, until 2004, the Burmese founders were both performing “traditional” tokè activities (selling sea cucumbers, shark

0002069075.INDD 1680002069075.INDD 168 10/25/2013 8:31:33 PM10/25/2013 8:31:33 PM

Th e Maung Aye’s Legacy 169

fi ns, and shells to Th ailand) as well as conducting the fi shing business. But with the development of the marine fi sheries and the growing number of Burmese coming to the islands in order to fi nd new opportunities to get richer, they had to fi nd another economical niche. Th e Burmese newly arrived in the village even began to exploit the same resources as the Moken, equipped with com-pressor-boats, allowing the divers to stay for hours underwater, while the nomads traditionally dive to the point of apnea. In order to compete with the new-comers, Th ein Zan, Myin Luin, Tin Win, and Khin Win used their tokè’s status to center all the Moken activities on squid fi shing. Th ey thus created probably one of the most profi table fi shing activities in the archipelago, directly com-peting with the more industrialized fl eet of lampara boats equipped on the littoral. Using the Moken workforce (both men and women), they started to send small traditional Moken individual boats (usually used to go from one kabang to another) with a nomad on each one, equipped with a hook line. But as with any economic success, this activity attracted other Burmese entrepre-neurs, threatening again the sociopolitical character of the Burmese tokè’s rela-tionship to the Moken. Actually, they used to supply the Moken with rice even during the monsoon, when all activities were stopped as the former Chinese tokè, fi ft y years ago, would have done. But now some new entrepreneurs are off ering more competitive prices to the Moken and the Insular Burmese fear that the whole system may collapse.

Between Integration and Revitalization Th ere may have been dozens of people like Maung Aye who contributed to the interethnic dynamic resulting from the encounter between Moken and Burmese in the Mergui Archipelago. Nevertheless, we could consider all the interethnic alliances as Maung Aye’s legacy, since his life and its consequences represent the local, national, and regional contexts in which this borderland’s appropriation is inscribed. In 2007, the Burmese founders of La Ngann village were torn between their insular belonging and the end of an age, anticipating the disappearance of the Moken culture. At that time, Th ein Zan was thinking of sending his youngest son back to his native place of Kyaik Kay Ta. Poleng, Myin Luin’s mother-in-law, was considering an improbable fl ight toward an island the Burmese would not have yet reached. Gatcha and Daké were deploring the impoverishment of the young Moken’s knowledge and their attraction toward the Burmese.

Nevertheless, the absence of a cultural policy of integration (that may have once existed when the Yangon authorities imagined the Moken had tourist

0002069075.INDD 1690002069075.INDD 169 10/25/2013 8:31:33 PM10/25/2013 8:31:33 PM

170 at bur m a’s m a rgins

value) to the advantage of the region’s economical development resulted in an actual, and not a politically invented, integration of the nomads. Th ey are being progressively incorporated into the Burmese social space while keeping their major identity traits. Th e fl otillas’ nomadism has been replaced by a mobility maintained by some specialists (shamans, harpooners, sacred dancers, boat builders); thanks to their tokè, they are still practicing a form of collection (even for squids) according to a nonaccumulation pattern (they continue to exchange their products against rice, clothes, etc.). Otherwise they might have faced directly the development of the Burmese fi shing industry and become some kind of second-class citizens, as happened in Ross and Elphinstone Islands in the North where they did not have tokè strong enough to protect them from the dominant economy. Moreover, the “segmentation” process of the Burmese must also be taken into account. Th e Burmese have little infl uence over Moken rituals; on the contrary, Moken beliefs regarding the insular environment progressively fi lter through the Burmese imaginary (see Boutry 2013 ; Boutry and Ivanoff 2008 ).

Furthermore, we could even compare the living conditions of the Moken of Burma and the Moken living in Th ailand. Th e latter were “off ered” a national park in place of their main island of residence in Ko Surin. Aft er the tsunami, they faced an eff ort by some Adventist missionaries to convert them to Christianity, which they resisted. Th is is the reason why, in 2006, some of the Moken coming from Ko Lao crossed the border heading to Nyawi (an island close to Kawthaung in the Myanmar waters) to perform a ritual linked with their daughter’s death, a ceremony Christian missionaries tried to prohibit. Th erefore, south Myanmar is even a refuge for the Moken between the two national appropriation processes from one part or the other of the border.

Th e diff erent policies applied at the national level pushed the Burmese pioneers to always go further south and away from the continent, to eventu-ally settle with the Moken in La Ngann. Inexorably, along with their economic networks’ expansion throughout the Mergui Archipelago came the spread of the administrative web. Th eir fl ight thus fully contributed to the integration of this borderland to the wider national territory while enriching the Burmese imaginary and geo-body with a new marine-insular identity.

Finally, it is quite diffi cult to predict the future of the Burmese-Moken communities, especially for La Ngann, for whom interethnic identity has been institutionalized to maintain their hegemony concerning resources within Burmese marine fi sheries’ development. In 2013, few things had changed in La Ngann and the village’s expansion slowed down. As a matter of fact, the economical sphere of Moken social space has been entirely

0002069075.INDD 1700002069075.INDD 170 10/25/2013 8:31:33 PM10/25/2013 8:31:33 PM

Th e Maung Aye’s Legacy 171

engulfed by the Burmese, focused on the sole squid fi shing activities. Burmese are present in all inhabitable islands, so Poleng and her group could defi nitely not fi nd “virgin” places to fl ee to. However, the ritual sphere has been proportionately enforced by the Moken, especially the bo lobung recalling the nomads’ ancestors thus their primacy on the insular territory. At the middle of these two fi elds of cohabitation, a new category arose in the offi cial villages’ list all around the archipelago. Besides the Moken (hsa-loun”) and the Burmese (bama), the hsaloun”/bama designates the house-holds where the husband is Burmese and the wife Moken, together with their children. Yet, with the opening of the country under the new government new spaces of expression arise and the hsaloun”/bama throughout the archipelago feel that it may be a good time for them and “their” Moken groups to obtain more offi cial recognition and even help, both from the regional government and international bodies, to valorize Moken culture (and implicitly protect their economical niche as Moken’s tokè). Th us, the whole system is oscillating again between an actual integration of the Moken in the regional context and the revitalization of the Moken culture that may fi nd new opportunities through the touristic development of the archipelago in the coming years.

References Ainsworth, Leopold. [1930] 1999. A Merchant Venturer among the Sea Gypsies, Being a

Pioneer’s Account of Life on a Island in the Mergui Archipelago . Bangkok: White Lotus Press.

Anderson, Benedict. 1983. Imagined Communities: Refl ections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism . London: Verso.

Benjamin, Geoff rey. 1985. “In the Long Term: Th ree Th emes in Malayan Cultural ecology.” In Cultural Values and Human Ecology in Southeast Asia , Michigan Papers on South and Southeast Asia . no. 27. Karl L. Hutterer, A. Terry Rambo, and George Lovelace, eds. Ann Harbor: University of Michigan, Center for South and Southeast Asian Studies, 219–278.

Boutry, Maxime. 2007. “L’appropriation du domaine maritime: des enjeux revisités.” In Birmanie Contemporaine. Gabriel Defert, ed. Bangkok/Paris: IRASEC/Les Indes Savantes, 389–410.

Boutry, Maxime. 2011. “Les frontiers de Leach au prisme des migrations birmanes ou penser la société en movement.” Moussons, Recherche en Sciences Humaines sur l’Asie du Sud-Est , 17, “Th e moving frontiers of Burma”: 105–125.

Boutry, Maxime. 2013. Les trajectoires littorales de l’hégémonie birmane, Analyse compar-ative (Birmanie-Th aïlande) des migrations birmanes et des processus d’appropriation

0002069075.INDD 1710002069075.INDD 171 10/25/2013 8:31:33 PM10/25/2013 8:31:33 PM

172 at bur m a’s m a rgins

de la mer dans les constructions identitaires, ethniques et nationales . Bangkok: IRASEC (forthcoming).

Boutry, Maxime, and Jacques Ivanoff . 2008. “De la segmentation sociale à l’ethnicité dans les suds péninsulaires? Réfl exions sur les constructions identitaires et les jalons ethniques à partir de l’exemple des pêcheurs birmans du Tenasserim,” Aséanie, Sciences humaines en Asie du Sud-Est, 22: 11–46.

Brac de la Perrière, Bénédicte. 2008. “De l’élaboration de l’identité birmane comme hégémonie à travers le culte birman des Trente-Sept Seigneurs,” Aséanie, Sciences humaines en Asie du Sud-Est 22: 95–119.

Brown, David. 1988. “From Peripheral Communities to Ethnic Nations: Separatism in Southeast Asia,” Pacifi c Aff airs 61(no. 1):51–57.

Chachavalpongpun, Pavin. 2005. A Plastic Nation: Th e Curse of Th ainess in Th ai-Burmese Relations . Lanham: University Press of America.

Coakley, John. 1992. “Th e Resolution of Ethnic Confl ict: Towards a Typology.” International Political Science Review/Revue internationale de science politique 13(4), “Resolving Ethnic Confl icts. La solution des confl its ethniques”: 343–358.

Commissioner of the Tenasserim Division. 1916. Selected Correspondence of Letters Issued fr om and Received in the Offi ce of the Commissioner, Tenasserim Division for the Years 1825–26 to 1842–43 . Rangoon: Superintendent, Government Printing and Stationery.

Condominas, Georges. 1980. L’Espace social. À Propos de l’Asie du Sud-Est . Paris: Flammarion.

Condominas, Georges, ed. 1998. Formes extrêmes de dépendance. Contribution à l’étude de l’esclavage en Asie du Sud-Est . Paris: EHESS. “Civilisations et sociétés” series.

Endicott, Kirk Michaël. 1983. “Th e Eff ects of Slave Raiding on the Aborigines of the Malay Peninsula.” In Slavery, Bondage and Dependency in Southeast Asia . A. Reid, ed. St. Lucia/Londres/New York: University of Queensland Press, 216–245.

Frécon, Eric. 2008. Th e Resurgence of Sea Piracy in Southeast Asia , Bangkok: IRASEC, occasional papers no. 5.

Geographer, (Th e). 1966. International Boundary Study, no. 63 , Burma-Th ailand Boundary . Washington, DC: Offi ce of the Geographer, Bureau of Intelligence and Research.

Ivanoff , Jacques. 2004. Les Naufr agés de l’histoire. Les jalons épiques de l’identité moken . Paris: Les Indes Savantes.

Ivanoff , Jacques. 2014. “From Paddy States to Commercial States: Some Refl ections on the Identity Construction Processes in the Borderlands—Cambodia, Vietnam, Th ailand and Myanmar.” In From Paddy States to Commercial States: Some refl ec-tions on the identity construction processes in the borderlands—Cambodia, Vietnam, Th ailand and Myanmar . (Forthcoming).

Ivanoff , Jacques, and Th ierry Lejard. 2002. Mergui et les limbes de l’archipel oublié: impressions, observations et descriptions de quelques îles au large du Tenasserim . Paris: Ketos/White Lotus Press, 234 pp.

0002069075.INDD 1720002069075.INDD 172 10/25/2013 8:31:33 PM10/25/2013 8:31:33 PM

Th e Maung Aye’s Legacy 173

Kittaworn, Piya, et al. 2005. “Voices from the Grassroots: Southerners Tell Stories about Victims of Development.” In Dynamic Diversity in Southern Th ailand . Wattana Sugunnasil, ed. Pattani: Prince of Songkla University, Silkworm Books.

Labbé, Armand. 1985. Ban Chiang: Art and Prehistory of Northeast Th ailand . Santa Ana, CA: Bowers Museum, KLS.

Liss, Carolin. 2003. “Maritime Piracy in Southeast Asia.” In Southeast Asian Aff airs 2003 . Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

Liss, Carolin. 2007. Th e Roots of Piracy in Southeast Asia . http://www.nautilus.org/publications/essays/apsnet/policy-forum/2007/the-roots-of-piracy-in-southeast-asia , accessed July 5, 2011.

Pelras, Christian. 1985. “Religion, Tradition, and the Dynamics of Islamization in South Sulawesi.” Archipel , 29: 133–154.

Reid, Anthony. 1988–1993. Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce 1450–1680 , 2 vol., vol. one (1988): Th e Lands below the Winds ; vol. 2 (1993): Expansion and Crisis . New Haven: Yale University Press.

Robinne, François. 1994. “Pays de mer et gens de terre. Logique sociale de la sous-exploitation du domaine maritime en Asie du Sud-Est continentale.” Bulletin de l’Ecole Française d’Extrême Orient no. 81 :181–216.

Rokkan, S., and D. Urwin. 1983. Economy, Territory, Identity: Politics of West European Peripheries . London: Sage.

Scott, James. 2009. Th e Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Shils, E. 1961. “Centre and Periphery.” In Th e Logic of Personal Knowledge: Essays Presented to Michael Polanyi. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 117–130.

Taylor, Robert H. 1998. “Political Values and Political Confl ict in Burma.” In Burma: Prospects for a Democratic Future. Robert I. Rodberg, ed. Washington, DC: Brookings Institute Press.

Turner, Frederick Jackson. 1893. “Th e Signifi cance of the Frontier in American History.” In Proceedings of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin , December 14, 1893.

Warren, James Francis. 2002. Iranun and Balangingi—Globalisation, Maritime Raiding and the Birth of Ethnicity . Singapore: Singapore University Press.

White, Walter Grainge. 1997 [1922]. Th e Sea Gypsies of Malaya: An Account of the Nomadic Mawken of the Mergui Archipelago with a Description of Th eir Ways of Living, Customs, Habits, Boats, Occupations, etc. Bangkok: White Lotus Press.

Winichakul, Th ongchai. 2003. “Writing at the Interstices: Southeast Asian Historians and Postnational Histories in Southeast Asia.” In New Terrains in Southeast Asian History . Abu Talib Ahmad and Tan Liok Ee, eds. Athens: Ohio University Press; Singapore University Press.

Winichakul, Tongchai. 2005 [1994]. Siam Mapped: A History of the Geo-body of a Nation . Chiangmai: Silkworm Books.

Wolters, O. W. 1982. History, Culture and Religion in Southeast Asian Perspectives . Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

0002069075.INDD 1730002069075.INDD 173 10/25/2013 8:31:33 PM10/25/2013 8:31:33 PM