Stones crying out and rock-witness to the narratives of the ...

The Crying of Lot 49 as a Narcissistic Narrative

Transcript of The Crying of Lot 49 as a Narcissistic Narrative

Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research

University of Sousse

Faculty of Arts and Humanities, Sousse

English Department

Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49 as a Narcissistic Narrative

A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Masters in Literature

Prepared by: Rabeb Ben Hnia

Supervised by: Professor NessimaTarchouna

Academic Year: 2012-2013

Table of Contents

Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………….1

First Chapter:

Theoretical framework: Towards a theory of narrative narcissism in literature

I. Contextualizing metafictional narcissism…………………………………..………...5

II. Towards a poetics of narcissistic literature: the Metafictional Paradox…..…..……..17

III. Narcissistic narrative: the introduction of the typology………………..…………….21

Second Chapter:

Strands of overt and covert diegetic narcissism in The Crying of Lot 49…………………..27

I. The parodic double-coding of Lot 49…………………………………………………29

1. Product and Process: Narcissistic takedown of Realism …………………….29

2. The lawlessness of genre: subverting the structuralist poetics………………..36

a. The detective genre …………………………………………………..37

b. The fantastic …………………………………………….……………41

3. Historiographic metafiction: from elitism to eclecticism ……..……………...47

II. The Narcissistic Anxiety of ‘non-influence’ …….………………….………………..56

III. The mise en abymic redoubling of Lot 49…………………………..………………...60

1. Visual redoubling in “Borolando el Manto Varo” ………..……………….…61

2. Televisual reduplication in Cashiered ………………….……………………63

3. The Theatre and its double: The Courier’s Tragedy …..……………………..65

Third Chapter

Strands of covert and overt linguistic narcissism

I. Overt linguistic narcissism in Lot 49…………………………………………………71

1. The Linguistic Demon ……………………………...………………………..71

2. The dysfunction of communication in Lot 49 ………………………………77

a. Indirect communication/ Telecommunication ………………………78

b. Direct communication ………………………………………….……84

II. The “Crying” for Silence: …………………………………………………….……..93

Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………….109

Acknowledgement

I dedicate this M.A thesis to anyone who has made its commencement and

completion possible, even with a smile .

I am deeply indebted to all my MA teachers who helped me sharpen my critical

standpoint and construct a self-confident and inquiring personality. They basically taught me

“how” to learn effectively instead of “what” to learn exclusively and this has certainly made all

the difference in my training. They have similarly armed me with a devotedly enthusiastic,

critical and challenging spirit that facilitated my entrance into the exhaustingly exotic area of

scientific research. To my supervisor and dear teacher professor Tarchouna, I feel most

obliged. Her valuable presence, pertinent feedback, ruminative silences, and even looks and

smiles were helpful guidance to me throughout my years of study and during my academic

research.

My gratitude goes also to all my first and second year MA classmates with whom I

savored the beauty and pain of Masters Studies. I am so grateful to Haifa Fairsy whose

kindness and benevolence has effectively reached me despite the long distance. To my best

friend and soulmate Fadwa: you added much zest to my experience…

I want to extend my thanks to all the members of my family and especially to my

mother Samira and my father Ayadi wishing that the defense day will answer all their

previous incessant questions. Yes I have gone through all that tiring work just to be here

today and to defend my own research.

To Mohamed Ali: Your precious presence in my life, continuous support, and extreme

devotion have certainly alleviated my occasional distress and lessened my incremental strain.

My debt to you is beyond words…

To koussay because your silence speaks more than any words in this world and

because you filled my heart with hope, vigor, and innocence!

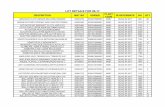

Figure 1: The front cover of Linda Hutcheon’s Narcissistic Narrative:

the Metafictional Paradox, designed by David Antscherl.

Figure 2: Remedios Varo’s painting: “Borolando el Manto

Terrestre” (Embroidering the Earth's Mantle), 1961.

The course of literary history and criticism has been altered in accordance to the

incessant shifts in the nature of human thought and philosophical insights. The numerous

turns in the determination of the art-life relationship is the major premise behind these

changes of paradigms. This relation evolved gradually from a pure Aristotelian imitative

relation, to a representation of a universal monolithic truth, then to aestheticism and

separateness, and finally to mutual constructiveness. In fact, the art-life connection determines

the different strategies of writing and theorizing in the arts in general and in literature in

particular. With the advent of poststructuralist thought and the contemporary skeptical view

towards fixed life structures and towards language as a transparent medium of reality

representation, contemporary approaches have been primarily based on the decentralization of

the telos and the Western logocentrism, the playfulness of meaning, the view of language as

self-reflexive rather than representational of truth, and the deconstruction of all forms of

systematization. Henceforth, representation, reality, presence and mimesis have become some

of the preliminary notions to which poststructuralist and postmodernist thought works hard to

subvert through the introduction of self-referentiality, relativism of reality, the metaphysics of

absence, and the open-endedness of signification as the backbone of their agenda. One form

of writing which foregrounds an intense awareness of such an alteration of paradigms and

problematizition of ontological status is narcissistic narrative or metafiction. This kind of texts

is aware of itself as narrative or artifice, and of its functioning and its mechanisms of

construction, of its past conventions and its mutation, and of the contentious processes of

production and reception of fiction. The metafictional text follows critically and self-

consciously the tracks of the overall history of literary composition and criticism and of its

own metamorphoses from the past till the present moment taking as its main challenge and

aim the exercise of self-exposition, self-criticism and self-evaluation.

The emergence of literary narcissism is due to an incremental need for fiction to

reconsider its paradigms and to identify its stand in regard to the numerous suspect literary

concepts such as reality, language, and representation. In Narcissistic Narrative: the

Metafictional Paradox1, Linda Hutcheon explains that “the drive toward self-reflexivity is a

three-step process, as a new need, first to create fictions, then to admit their fictiveness, and

then to examine critically such impulses” (19). The insatiable rising of literary theories

starting from the 1960s has, in its turn, informed the theory-consciousness of most of the

literature of the time. Hence, this period has marked a substantial phase in fiction writing and

criticism. The Crying of Lot 492, written by the American novelist Thomas Pynchon and

published in 1966, sketches the ascending need for the literary text to uncover its identity in

full and to direct the criticism to its depths. It is of prime concern at this introductory stage of

the dissertation to provide a brief account of the text under study.

Lot 49 revolves around an American housewife named Oedipa Maas who is set in the

quest of executing a will left by her erstwhile boyfriend Pierce Inverarity -a California real

estate mogul. As it is her first experience as an executor, Oedipa has accorded to herself the

mission of amassing clues and seeking help from different persons starting from her lawyer

Roseman, to Pierce’s lawyer Metzger, to her psychotherapist Dr. Hilarious, then to a number

of other persons that she has never met before (the Paranoids: Miles, Dean, Serge and their

girls, Mike Fallopian, Manny Di Presso, Randolph Driblette, Stanley Koteks, John Nefastis,

Genghis Cohen, an Inamorati member, Mr. Toth, Emorty Bortz, Winthrop Tremaine, Jesus

Arrabal, Helga Blamm…). Once her objective is identified, Oedipa launches herself into the

quest of sorting out Inverarity’s estate. Eventually, it has never occurred to her that she has

only left San Narciso -her hometown- to find out that an ambiguous mystery is awaiting her

and that her quest is going to be neither straightforward nor painless. The mystery is, in fact,

enshrined in Inverarity’s stamp collection which introduces her to a clandestine mail system 1 Henceforth referred to as Narcissistic

2 Henceforth referred to as Lot 49

and which will be sold after in an auction under the label of “Lot 49”. During her execution of

the will, Oedipa travels from one place to another, meets a tremendous number of people, and

collects various disconnected clues, which lead her towards further ambiguity and endless

questioning. She assigns to herself the task of deciphering the truth lying behind a secret mail

system known as the Trystero related to a W.A.S.T.E. networking. Yet, the more clues and

signs Oedipa manages to assemble, the more puzzled she turns out to be, since these clues

keep leading her to other clues in an endless way revealing nothing but more ambiguity and

misdirection. After undergoing an extremely long baffling questing journey, Oedipa ends up

sitting in an auction room awaiting the lot to be cried by Loren Passerine, the finest auctioneer

in the West, with the mystery unresolved and the bewilderment heightened.

This dissertation probes an in-depth analysis of the novel from the lens of narrative

self-consciousness, in an attempt at exposing the mystery of its novelistic structure and at

questioning the art-life-relation. It aspires to determine to what extent is Lot 49 narcissistic or,

in other words, to what extent does the novel expose and thematize its own mechanisms of

meaning-construction. It will, therefore proceed according to a three-fold structure.

The first chapter serves as a theoretical background to the study offering most of the

key concepts and links between the various theoretical frames employed in the analysis. It

starts by contextualizing novelistic narcissism amid the panorama of emerging critical

theories. It then determines the main concern and strategies of actions of textual narcissism

and ends by eliciting the technical terms and taxonomies of the theory. Accordingly, the first

chapter is going to be the guiding thread as well as the point of reference for the subsequent

application of textual metafiction in Lot 49.

The second chapter focuses on the overt and covert strands of narcissism in the

diegesis. It relies basically on Hutcheon’s study of poetics, politics, and historiographic

metafiction of postmodernist texts. It reveals the narrative’s own consciousness and

exposition of the narrative techniques and narration processes. It shows how narration takes

over the narrated “transforming the process of writing to the subject of writing” (McCaffrey

15).

The third chapter dwells on the overt and covert traits of linguistic narcissism. It

probes the thematization of language and communication in the novel using a literary

pragmatic perspective. It simultaneously explores the playfulness of the structure of the text

and the aporia of regress in its systems of signification. It ascends accordingly to sketch the

postmodernist move toward a literature of silence.

One of the major premises of this dissertation is the blending of literary pragmatics,

postmodernism, and poststructuralism in the theoretical frame and analysis. Being theory-

conscious, the text lends itself perfectly to such a combinatory theoretical study. In fact, it

informs the theoretical ground itself through performing a participatory role in the creation of

a new poetics. It is, henceforth, a “theory-in-practice text”. Patricia Waugh elaborates on this

view in Metafiction: the Theory and Practice of Self-Conscious Fiction asserting that “all

writing that is metafictional can be said to ‘explore a theory of fiction through the practice of

writing fiction’” (2, my emphasis). This theoretical frame informs this dissertation guiding it

towards an in-depth view of the narrative and linguistic structure of Lot 49 and helping it to

uncover its labyrinthine fabric and to determine its paradoxical ontological status.

Basic to this study of novelistic self-consciousness is the awareness that narrative

narcissism is neither a literary genre nor a thematic concern. It is a theoretical project that lies

under the postmodernist widespread metafictional corpus. Being primarily postmodernist in

its grounding and aspiration, narcissistic narrative bears within it most of the postmodernist’s

issues and paradoxes. Through the lens of postmodernist and poststructuralist approaches, this

chapter will attempt to perform a theoretical contextualization of metafictional narcissism at a

first stage, then a determination of its poetics and taxonomies.

I. Contextualizing Metafictional Narcissism:

The label “Narcissistic narrative” was first suggested by the postmodern Canadian

literary theorist Linda Hutcheon in her book Narcissistic in1980, to designate a type of fiction

that “includes within itself a commentary on its own narrative and/or linguistic identity” (11).

Soon after, the use of such a label has become more common among other critics and theorists

like Robert Scholes, Lucien Dällenbach, and Patricia Waugh3. In her study of textual

narcissism, Hutcheon starts from the assertion that the term has to be approached in a neutral

way as devoid of any pejorative or psychological connotation (1). Narcissism, here, is a

figurative adjective that is “rather descriptive and suggestive as the ironic allegorical reading

of the Narcissus myth”, and is allotted to the work itself and not to the author (1). It is,

thereby, the fictional work which is exposed to its linguistic and diegetic double. While

narcissism is mainly a form of writing not restrictive to one particular period or literary genre,

it is worth noting that such a strategy has become rampant in the 1960s in Europe and the

United States, a period that witnessed the swift growth of numerous literary theoretical

discourses and the heyday of postmodernism (4). “In the criticism of the 70s the term

‘postmodernism’ began to appear to refer to contemporary self-conscious texts”, equating

3 While Robert Scholes has performed a thorough study on metafiction labeling it an “anti-narrative” or “stillborn literature”, Lucien Dällenbach has invested heavily on the study of the “mise en abyme” as a literary device basic to doubling the narrative structure. In 1984, Patricia Waugh published her meticulous study on the theory and practice of metafiction.

hence its theoretical approach and strategies with the metafictional narcissistic phenomenon ,

rendering narcissism a prime determining feature of most postmodernist fiction. It is

noteworthy that postmodernist texts are not altogether metafictional, nor do all metafictional

writings restrictively range under the postmodernist corpus. Narcissism has, in fact, surfaced

from the very rise of the novel tradition, through the use of authorial intrusions in the

narrative level and direct allusion to the reader, with works such as Don Quixote, Tristram

Shandy, and Vanity Fair (44). As it is outlined by the twisting nature of critical orientations,

“critical theories may influence art, but in this case the literary tradition of novelistic

development seems the more likely general force” (30). In a nutshell, its practice has long

preceded the theory though its use was ways less important and explicit than it actually is in

the contemporary context.

One of the major strategies of action of postmodernist narcissism is its critique of

realism. Laconically, the realistic novel reached its apogee in the eighteenth century and is

said to be the offspring of the Age of Reason that is the age of logic, progress, and

universalism as underlined in Hutcheon’s A Poetics of Postmodernism4 (26). One of the major

premises of realistic literature is the mimetic view of art which accords to the latter the quality

of being “representational” of a pre-established transcendental truth (Abrams 7-8). Such a

view has its own repercussions in the definition of art, literary criticism, and reality in general.

The work of art acquires its importance from its being an aesthetic product originated by an

artist who takes upon his shoulder the exercise of representing “reality as it is”, or better say

“a slice of life” (McCaffrey 12). Subsequently, to write in the traditional realist vein is to

uphold criteria as “the order of the narrative, chronological plots, continuous narratives

relayed by omniscient narrators, [and] closed endings” (Barry 82). This paradigm has allotted

cardinal substantiality to the artist who is treated as the meaning-initiator and truth-mediator.

4 Henceforth referred to as Poetics

The artist becomes, in fact, the center who holds all the threads leading to the ultimate

meaning of the novel. According to this view, “literature turns out to be an item for

consumption” in which the sole role allotted to the reader is the passive reception of a “hidden

meaning” (Iser 4).

Realism has, in fact, gone beyond being a defining feature of a particular literary genre

or movement or a historical period to becoming a characteristic mode of thought governing or

better say monopolizing Western literary discourses until the end of the nineteenth century

(Hutcheon, Narcissistic 18). It advocates the mimetic view of art as representational of life

and universal truth, of reality as pre-existing language, and of language as transparently

mirroring the world (Abrams 33). This reductive view of language and its functions is the

central tenet behind the humanistic universalizing insight into literature as being “realistic”

and “referential”: realistic in the sense that it represents a transcendental reality as it is, and

referential in the sense that the words it uses have actual referents as objects in the real world

that is they refer to an external heterocosm transforming fiction to a mirror that reflects the

outer world (Hutcheon, Narcissistic 10). Based on conventional premises like verisimilitude5,

plausibility, authorial authenticity and on beliefs in the objectivity and truthfulness of the

historical discourse or “the chastity of history” as Fustel Coutages describes it, realist fiction

focuses mainly on the work of art as a product that works faithfully to aesthetically reproduce

an extraneous universal and orthodox reality (qtd. in Barthes, “The Discourse of History6” 3).

Its claims to the universality of truth and values, or what Barthes calls “the germ of the

5 Verisimilitude is “an attempt to satisfy even the rational, skeptical reader that the events and characters portrayed is very possible. ... Far from being escapist and unreal, the novel was uniquely capable of revealing the truth of contemporary life in society. The adoption of this role led to detailed reportage of the physical minutiae of everyday life -clothes, furniture, food, etc. - the cataloguing of people into social types or species and radical analyses of the economic basis of society. The virtues pursued were accuracy and completeness of description” (Childs and Fowler 198-9).

6 Henceforth referred to as “Discourse”

universal” and John-François Lyotard classifies under the category of “metanarratives” or

“grand narrative”, are put under ruminative scrutiny (34). The attack on such foundationalist

and essentialist ideas is an attack on the whole ethos of the Enlightenment humanistic

philosophy which was the leading force behind rooting such stances in literary criticism until

the mid-nineteenth century (35). Postmodernism is to be considered as one of the contesters of

such a view. It is an “incredulity toward metanarratives” working to subvert them and

highlighting that what realism has always presented is not reality but only its “guise or

illusion” since it overtly “masks art’s own conventionality” (Lyotard xxiv). Modern

philosophical thinking has, in fact, paved the way for such findings through initiating the

questioning of notions of truth, facts, and representation. For instance, Frederick Nietzsche’s

assertion that “there are no facts, only interpretations”, constitutes a battle cry that has marked

the shifting trajectory of philosophical and literary paradigms and the move towards a more

relativistic view of reality and universals.

The critical return to the past shows the metafictional critique of the classical view of

reality, especially the claims to objectivity, foundationalism, teleology, and transcendentalism

(Lyotard 37). “On the level of discourse,” as Roland Barthes argues for, “objectivity appears

as a form of imaginary projection, the product of the referential illusion” and “the ‘real’ is

never more than an unformulated signified, sheltering behind the apparently all-powerful

referent” creating no more than a “realistic effect” (“Discourse” 6). Deconstructive in intent

and critical in impulse, metafictional narcissistic texts veer towards a provisional view of

realities, a skeptical attitude towards language, a focus on the processes of literary production

and reception rather than on the final aesthetic product. Similarly, it relies upon the mechanics

of signification rather than those of imitation, and disbelieves the essentialist claims to

orthodox truth, universal values, and factual knowledge (Hutcheon, Poetics 89). The

deconstruction of the kernel of realism is further complicated by the problematic relation of

postmodernism to modernism.

The relation of postmodernism to modernism has always been contentious and

constantly questioned. Whether it is one of complicity or disjunction, it is ostensible that most

postmodernist theorists and artists7 relate their new perspectives to discussions and critique of

modernism. Chiefly, a distinction has to be drawn between the terms “modernity and

postmodernity” as denoting a historical period and “modernism and postmodernism” as

describing movements and artifacts in the cultural field (Best and Kellner 5). In this

dissertation and as the argument is going to further outline, postmodernism is considered as

both an extension of and a reaction to modernism.

As far as the literary scope is concerned, modernism is often identified with the works

of T.S. Eliot; Ezra Pound; and Ernest Hemingway in America, Gertrude Stein; D.H Lawrence;

and Virginia Woolf in England, and Mallarmé; Marcel Proust; and André Gide in France. It

carried an “aestheticized conception” of art that came to be known after as “art for art’s sake”

(Sim 135). The “fetishizing” of art and the hierarchical modernist distinction between “high

art” and “popular art” results in the elevation and “canonization” of some works over others

(136). This orchestrates the fact that modernism is elitist to the point that it illustrates “the

futility of all arts except the highest” (Ruland 256). This process of canonization is one of

selection and exclusion since it downgrades certain works and upgrades others. The vexing

questions interpolated by postmodernist theorist and writers in this context are mainly: who

sets the canon? Who possesses the authority to determine what is proper and what is

inappropriate? And does everyone have the same definition of aesthetic value? All these

debatable inquiries seem to agree upon the viewpoint that the canon is “exclusive and

hierarchical; artificially constructed by choices made by human agency [critics and writers]”

7 Some of these theorists are Jean-François Lyotard, Frederick Jameson, Jürgen Habermas, Ihab Hassan, Susan Sontag, Harry Levin, Irving Howe, Leslie Fielder (Best and Kellner)

(Selden and Widdowson 12). To this canonizing tendency, metafictional postmodernism

responds by the investigation and re-evaluation of popular culture so that “[t]he

postmodernism of the 1960s [is] therefore in part a populist attack on the elitism of

modernism” (Sim 147). It remains worth noting, though, that the merging of “high and pop”

is not a call for the “end of standards”, but rather a call for “rigorous… contingent standards”

(157). The violation of this boundary, in fact, refutes any attempt at stratifying literature and

culture in general, and aspires to a neutral view that avoids value judgment and downgrading.

Postmodernist metafiction searches a hierarchy-less space where the terms high and pop

culture “mean nothing more than culture liked by many people” (157, emphasis in the

original).

In addition, modernist poetics revolves around the self-sufficiency of the work of art,

and the possibility of rendering subjectivity and consciousness through the experimentation

with the novel writing strategies such as the stream-of-consciousness technique8,

fragmentation, and multiple focalizations9 (Genette, Narrative Discourse 266). Brian McHale

sums up the preceding standpoints as follows: “modernism foregrounds themes such as the

accessibility and circulation of knowledge and its limits through the multiplication and

juxtaposition of dissimilar perspectives, the focalization of all evidence through a single

‘center of consciousness’, and the use of structure as a compensation for the disordered

subjectivity” (Postmodernist Fiction10 9). Yet postmodernism diverges from modernism by

virtue of its “dominant” that is what Roman Jakobson defines as “the focusing component of a

8 The stream-of-consciousness is “a technique which seeks to record the flow of impressions passing through a character’s mind. The best-known English exponents are Dorothy Richardson, Virginia Woolf and James Joyce” (Childs and Fowler 224).

9 Genette uses the term focalization “to avoid the too specifically visual connotations of the terms vision, field, and point of view. [He] take[s] up here the slightly more abstract term focalization which corresponds, besides, to Brooks and Warren's expression, ‘focus of narration’ (Narrative Discourse 189).

10 Henceforth referred to as Postmodernist

work of art” (qtd. in Mchale 9). While the modernist dominant is “epistemological” that is

focusing on “problems of knowing”, the postmodernist dominant is “ontological” and based

on “modes of being” (10, emphasis in the original). Related to such ontological issues are

postmodernist questions which bear “either on the ontology of the literary text itself or the

ontology of the world which it projects, for instance: what is the mode of existence of a text,

and what is the mode of existence of the world (or worlds) it projects?” (10). However, this

claim does not deny postmodernist occasional raising of epistemological queries, yet these

inquiries remain backgrounded at the expense of ontological matters which are highly

foregrounded. Patricia Waugh asserts that the literary paradigm swings from modernist

“writing of consciousness” to postmodernist “consciousness of writing” itself (24). This can

be further clarified as follow: the modernist view of writing as reflective of the subjectivity

and selfhood of the writer is substituted by the postmodernist view of writing as reflective of

its own self. Postmodernism continues in a sense what Jürgen Habermas calls the “incomplete

project of modernism” which initiated the skepticism towards language, universal certainties,

the self-reflexivity of fiction and all forms of arts in general (qtd. in Best and Kellner 248).

Yet, it goes against modernist claims to the self-sufficiency and autonomy of arts,

ahistoricism, apoliticism, elitism, and fixedness of meaning in literature generating a “poetics

of unrest” (Hutcheon, Poetics 42). This unrest stems basically from the “inherent paradoxes of

postmodernism” and its rootedness in “duplicity” and perspectivism (23). There is not a single

unified postmodern theory therein, “rather one is struck by the diversities between theories

often lumped together as ‘postmodern’ and the plurality of postmodern positions” (Best and

Kellner 2). The pluralism of the theories of postmodernism necessitates a meticulous

determination of the theoretical framework to be adopted in this study which is basically a

postmodernist poststructuralist frame of reference.

The relationship of poststructuralism to postmodernism, as the subsequent analysis

will sustain, is one of adjacency and complementation rather than one of discontinuity and

conflict. Poststructuralism is to be considered as a part of an inclusive postmodernist

intellectual terrain. The major premise of these two theoretical projects consists mainly of “a

rejection of many, if not most, of the cultural certainties on which life in the West has been

structured over the last couple of centuries” (Sim VII). Throughout Writing and Difference11,

Jacques Derrida sketches many tenets of the earlier mentioned Western philosophy such as

the “metaphysics of presence”, “teleology”, “logos”, “closure”, “centralization”, “hierarchy”,

“binarism”, and “totality”. Both postmodernist and poststructuralist approaches are

consequently “partners in the same paradigm…together they are seen as exercising a joint

critique of ideas of order and unity in language, art and subjectivity as upending old

hierarchies and rattling political convictions” (Brooker 14). Poststructuralism is

simultaneously a continuation and a critique of structuralism which is based on the theory of

the Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure and marked by “a move toward systematicity” (Stam

9). Both approaches share as their starting point the Saussurean definition of language as a

system of signs where the sign designates the basic unity of meaning and unifies arbitrarily

the signifier and signified (De Saussure 67). Outlined by de Saussure, the signifier is the

“word image (visual or acoustic)” of the sign while the signified is its mental abstraction (12).

The sign is “arbitrary” and the relation between signifier and signified is regulated “by

conventions” (10). Another prime Saussurean distinction is the one drawn between “langue”

as “the collective system underlying any human signifying practice” and referred to as

“competence”, and “parole” as the “individual actualization of the codes and conventions of

the system” and referred to as “performance” (qtd. in Culler, Structuralist Poetics 6). The

structural object of study is namely the decoding of the different rules and semiotic

combinations in a given system in order to reveal the structure lying beneath, thus prioritizing

11 Henceforth referred to as Writing

competence over performance, or langue over parole (10).

This linguistic model represents the backbone of structuralist analysis or semiotics

which makes its paramount aim the demystification of the “intrinsic grammar” that governs

the operations of any system of signification (12). Such a study has become widely inclusive

referring to any signifying system besides language, for instance the system of clothing as

exemplified by Barthes in Mythologies, the system of myths as scrutinized by Claude-Lévi

Strauss, or the system of narratives as argued for by narratologists such as Gérard Genette and

Tzevtan Todorov. This semiotization of all signifying systems, which run rampant in the mid-

twentieth century, provides a sense of control to its users through offering them “a

methodological key to unlock the various systems that made up th(e) world” (Sim 4). The

major point of divergence between poststructuralism and structuralism lies in their diverse

apprehension of the signifier-signified relationship. While structuralist theories determine it as

a one-to-one relation similar to the back and front sides of a sheet of paper as illustrated by De

Saussure, poststructuralism argues for a more playful field of signification where to each

signifier relates an indefinite number of signifieds set in constant motion and regress (Derrida,

Writing XVİİİ). Language, and by implication, any system of signification are unstable vis-à-

vis the slippery nature of the signified and the playful aspect of signification (354). Since to

each signifier corresponds an indefinite number of signifieds, the possibility of the presence

of one “‘transcendental signified’, that is, a concept independent of language” becomes a

mythical one (xvi). Indeterminacy is therein an inherent feature of meaning which persistently

wavers in a field of free play of signifieds according to the logic of “Différance” (95).

Différance is, in fact, a neologism instigated by Jacques Derrida conveying the divided nature

of the sign and combining both words: “différence” and “deferral”. Signs “differ” in the sense

that they emerge from a system of differences and acquire meaning and value from their

differential relation to the other signs in the same system (370). They simultaneously “defer”

in the sense that they postpone the presence of any final meaning due to the free-floating

nature of signifieds and their operation through an “aporia of regress” rejecting any claim to a

complete fixed meaning or “closure of representation” (316). Therefore, poststructuralism is

directed against the propensity for systemization and toward the “revenge of Parole”

(Hutcheon, Poetics 82). Poststructuralism, as foregrounded in the works of Jacques Derrida

on deconstruction, shows a thoroughgoing distrust to centered, totalizing, and theological

truth, and calls into question the structuralist model of the sign (Derrida, Writing 7). Since

signifiers represent “the material vehicle of the sign”, the written text is, in a first place, “an

ensemble of signifiers”. Its “materiality” should not go unnoticed or downgraded as

structuralists tend to do in their analysis (264). The tendency to “sublimate” the text, that is, to

abstract it through the immediate translation of each signifier into a signified halts the

appreciation of the “body” of the work or of the materiality of the aesthetic object as such

(38). The resistance of this sublimation and the move towards silence instead of words in the

experience of reading literature gives a space for the savoring of the artificiality and

materiality of arts in order to avoid any subsequent mistaken view of art as the vehicle of

Truth (Sontag 1). In fact, the paraphernalia of fiction construction consists of words, material

signs, artifices, and not reality, actual referents or facts. Therefore, deconstruction goes in the

reverse direction to structural semiotization, since it focuses on the artistic performance as

such or the “parole” rather than in the internal overlaying structure subverting the fixed

correspondence of signs to meanings and charting the endless chain of signification,

performing in a way a sort of “desemiotization” of semiotics (Hutcheon, Poetics 82). In this

context Hutcheon opines that:

In the light of the structuralist focus on langue and on the arbitrary but stable

relationship between signifier and signified, postmodernism might be called the

“revenge of parole” (or at least of the relationship between the subject, as

generator of parole, and the act or process of generation). Postmodernism

highlights discourse or “language put into action”. (82)

The “desemiotization” and semiotization are antithetical yet complementary. While

the former assures the acquaintance with the “body” of the work as such that is the

performance through “desublimation”, the latter assures the distancing of oneself from the

performance and his or her launching in the critical activity (Pavis 215). As every discourse

creates its metadiscourse, each semiotization inaugurates its own desemiotization or else each

construction is followed by its deconstruction. Accordingly, the deconstructive practice

implies an ongoing skepticism towards language and reality, a resistance to any claim to a

final meaning or closure of signification, a subversion of previous hierarchies and binary

oppositions, a critical attitude towards the “metaphysics of presence” and the fixedness and

stability of any structure, and a rejection of “Western logocentrism” and “phonocentrism”

(Derrida, Writing 70).

The fundamental role that language plays in altering the approaches to literature is not

to be undermined in this discussion. The pre-Saussurean view of language as a “transparent

medium” that represents a pre-existing universal truth or what Roland Barthes describes as

“language that pretends not to be language, to be uncomplicatedly transparent -a

naturalization of language as a referential medium” (qtd. in Currie 7) has been shaken by the

structuralist reworking of the concept of language as rather “a constitutive part of reality,

deeply implicated in the way the world is constructed as meaningful” (3). Literature does not

represent the world yet “it is only possible for it to represent the discourses of that world”

(Waugh 41). Postmodernism does not, in fact deny the possibility of the existence of reality

yet it makes it as its prior premise the questioning of the identity of reality and its sources

which is never natural or given, yet always humanly constructed (28). Here, the logic of

representation is not totally denied but rather reworked to turn from a referential logic to an

external world to a self-referential one moving inward into the work of art in itself since

“language bears within itself the necessity of its own critique” (Derrida, Writing 358). Each

discourse, accordingly, carries within its bounds its metadiscourse. In other words, “it is not

that representation now dominates or effaces the referent,” as Hutcheon opines, “but rather

that it now self-consciously acknowledges its existence as representation, that is as

interpreting its referent, not as offering direct and immediate access to it” (The Politics of

Postmodernism12 34). The narcissistic text equivocally and unequivocally exposes the

processes of its own construction and its status as artifice and hence it admits the fictionality

of any simple connection between art and life or reality (Hutcheon, Narcissistic 47). Reality is

a human construct, thus a fiction or a narrative; Hans Bertens sums up this crisis of

representation stating that:

If there is a common denominator to all postmodernisms, it is that of a crisis in

representation: a deeply felt loss of faith in our ability to represent the real, in

the widest sense. No matter whether they are aesthetic, epistemological, moral,

or political in nature, the representations that we used to rely on can no longer

be taken for granted. (qtd. in Heise 965)

The raising awareness of such a crisis has obviously its own effects on the theory and

practice of fictional writing. The evolving trajectory of the linguistic sign has, in its turn, its

own implications on the literary field of theory and criticism. Such a trajectory is traced by

Terry Eagleton who opines “first we had a referent” as suggested by realism, “then we had a

sign” as postulated by structuralism, and “now we just have a signified” announcing the

poststructuralist free-floating approach to the system of signification (qtd. in Brooker 205).

Hence the narcissistic narrative lies under the third category that of the problematization of

signifieds and their slippery nature, and goes beyond the postulations of realism, modernism,

12 Henceforth referred to as Politics

and structuralism veering toward a poetics of relativism, pluralism, and unfixedness.

II. Towards a poetics of narcissistic literature: the metafictional paradox

A major paradox of postmodernism is inherent in the very attempt to define it, for

postmodernism defies all claims to fixed and essential definitions. Postmodernism is rather a

skidding term that rejects all attempts to determine it, so “we need more than a fixed and

fixing definition,” as Hutcheon argues, “we need a ‘poetics’, an open, everchanging

theoretical structure by which to order both our cultural knowledge and our critical

procedures” (Poetics 14). While following its track, postmodernism proves to be the perfect

bearer of self-contradiction at its very core, since it implicitly celebrates its “duplicity” or

“doubleness” and persistently works within the very systems it attempts to subvert (180). For

instance, it is intensely “self-reflective” and “paradoxically historical” incorporating the

distinctive form that Linda Hutcheon names “historiographic metafiction” which puts under

subversive scrutiny both fictive and historical representation. Postmodernist historiographic

metafiction brings to the fore its historical, social, and political grounding alongside its

outright self-refrentiality (92). Metafictionality is, in a nutshell, fiction about fiction or the

awareness of the mandatory co-existence of language and metalanguage. This brings the

Derridean conception that each discourse carries within it its metadiscourse and each

metadiscourse has a meta-metadiscourse ad infinitum since “language bears within itself the

necessity of its own critique” (Writing 358).

Metafiction is defined by Patricia Waugh as “a term given to fictional writing which

self-consciously and systematically draws attention to its status as an artifact in order to

question the relationship between fiction and reality” (3). It is hence related to the idea of

meaning and fiction as “constructs” rather than as having “representable essences” (Currie

15). The term was first introduced in 1960 by William Gass who sought a label for recent

fiction that thematizes its own fictionality (4). This postmodernist metafictional self-

reflexivity is further problematized by its alliance with historical grounding and referencing.

Part of the postmodernist fictional narcissism revolves around the works’ awareness of “the

presence of the past” which it critically rethinks and consciously reworks (Hutcheon, Poetics

12). The knowledge of the past is only textually possible since the past is palpable in the

present through its “traces” like records, documents and texts (81). The past becomes,

consequently, a textualized space that is inscribed in discourse or “semiotized” (97). Its

inscription in discourse implies its being socially and ideologically loaded (112). Therefore,

the “dialogism”13 that characterizes the fictional discourse, as suggested by Mikhail Bakhtin

in his study of the novelistic discourse, challenges any assertion about the objectivity and the

transparency of the historical discourse. As Roland Barthes notes in “Discourse”, the historian

is not so much a “collector of facts” as he is a “collector of signifiers” or a fabulator (147).

History creates a “realistic effect” and not transparent reality, since what it nominates as fact

has no more than a “linguistic existence” in “the shell of signifiers” (148). The historical

discourse is nothing more than “a form of ideological elaboration, an imaginary elaboration”

that depends on the narrative mechanisms of selection, ordering, and plotting in its

construction (147). Brian McHale perceives history and fiction as exchanging places so that

history becomes fictional and fiction becomes “true history” and “the real world seem(s) to

get lost in the shuffle” (Postmodernist 96). Accordingly, fiction and history become

interchangeable and complementary. Once again, essentialism, factuality and truthfulness

prove to be fallacious and hence put under question. Historiography that is the “narration of

what happened”, as Hayden White accounts for it, is a highly problematized process in

13 “Dialogism” is a term suggested by Bakhtin to describe the fictional language, which he sees as “inherently heteroglot”, i.e. formed of “diverse (hetero-), speeches (glossia)”. The language of fiction becomes a form of hetroglossia where “different discourses dialogically encounter”. Each word is thus loaded with different voices and ideologies that stratify it from within. Bakhtin opines consequently that the dialogic process of language constitutes a constant and simultaneous play between “centralizing and decentralizing forces of language” or what he terms as “centripetal” and “centrifugal” forces (Bakhtin 272).

narcissistic narratives which openly acknowledge the past’s “own discursive contingent

identity” (Hutcheon, Poetics 24). Each literary discourse is grounded in a context and

simultaneously uses a metatext to divulge this grounding. Therefore, “even the most self-

conscious of contemporary works do not try to escape, but indeed foreground the historical,

social, ideological contexts in which they existed and continue to exist” (25). Narcissistic

narratives foremost revealed criterion is that it is “art as discourse”, which is intensively

related to the ideological and even the political spheres (35).

Central to this return to the past is the abundant use of parodic strategies. As

correspondingly defined by Hutcheon in the Politics and Poetics, parody is as a form of

“revision or reading of the past that both confirms and subverts the power of the

representation of history” (95), and as “repetition with critical distance that allows ironic

signaling of difference at the very heart of similarity” (26). Parody occupies a twofold

position which imbues postmodernism with duplicity and paradoxes. It lies inside and outside,

“installs and destabilizes”, “uses and abuses”, “mystifies and demystifies”, identifies with and

distances from, foregrounds and backgrounds (23). Postmodern art therein parodies prior

literary conventions by divulging its functioning and operative strategies while opening the

way into new fictional modes of understanding and studying literature (Waugh 65). It has to

be noted, though, that the reprise of the past is not a purposeless or random reprise as opined

by the postmodern theorist Frederick Jameson who treats parody, pastiche, and intertextuality

as value-free and as “the random cannibalization of all the styles of the past, the play of

random stylistic allusions” (17). This accusation is totally rejected by Hutcheon‘s study of

parody in A Theory of Parody which argues for the seriousness, aestheticism, and

functionality of parodic discourse stating that parody –also known as “ironic quotation,

pastiche, appropriation, or intertextuality”- de-doxifies all taken for granted beliefs and

ideologies (22).

Intertextuality highlights the fact that every text is an “intertext”, a hybrid network of

quotations taken from prior texts (Barthes, Image Music Text 160). It ends in a way “the

anxiety of influence” and traces the “non-anxiety” from the “cult of unoriginality” (Bloom,

The Anxiety of Influence xi). The focus on irony in the reprise of the past is characterized by

its “critical distance” and not by “nostalgia” and this particular detail is of a paramount

importance in the differentiation of the postmodernist approach to the past to the prior

approaches (Hutcheon, “Irony, Nostalgia, and the Postmodern” 6). Irony, here, is situated “at

the edge” between the voiced and the unvoiced; it is “the intentional transmission of both

information and evaluative attitude other than what is explicitly presented” triggering an

interactive relation between the text, the ironist, and the interpreter (Hutcheon, Irony’s Edge

11). The feature acquired by irony in this context is, in a way, reminiscent of Brecht’s epic

theater which seeks to distance the reader in order to raise his critical attitude and to avoid the

identification with the elements of the aesthetic work (Selden and Widdowson 81).

As a miscellaneous site of “dialogic encounter”, postmodernism goes on in its exercise

of mixing and blending contradictory scopes and fusing them into an all-encompassing

dialogic literary paradigm. The blurring boundaries between “popular art and high art”, of the

aesthetic and the theoretical, of “poetics and politics”, of “history and fiction”, of power-

holders and eccentrics, of old and new are distinctive features of narrative narcissism which

heighten its commitment to “duplicity” and “double-coding” (Hutcheon, Poetics 30). It is, in

fact, a patchwork of numerous and contradictory elements, which explain its owing the label

“the literature of unrest” par excellence (42).

Simultaneously, postmodernist texts draw upon any form of signifying practices

operative in a given culture. It incorporates, for instance, the discourse of media, visual arts,

music, cinema, architecture, newspaper, philosophy, literary theory and criticism, sciences,

sociology, psychoanalysis… This “polyphony”, to use Bakhtinian terminology, stresses the

ever-expanding intertextual network that denies any pretension to an original one-centered

discourse and argues for the “interdiscursivity” of the literary discourse (130). Hence,

intertextuality is, as Barthes opines, the indispensable condition of textuality (Image Music

Text 160). It should be noted here that the intertext in literary discourse is not exclusively

taken from the repertoire of literature but could emerge from any given historical, political,

and cultural discourse. In fact, “literature should not be analyzed as a form of expression

which simply sets its own traditions and conventions totally apart from those that structure

non-literary culture” (Waugh 28). The borderlines or the frontiers between discourses are no

longer tenable in a highly discursive literary web. Michel Foucault, who in his theory of

discursive formation sustains the view of discourse- or what he defines as “language in use”-

as a discursive practice, remarks that “the frontiers of a book are never clear-cut: beyond the

title, the first lines, and the last full-stop; beyond its internal configuration, and its

autonomous form, it is caught up in a system of references to other books, other texts, other

sentences, it is a node within a network” (qtd. in Hutcheon, Poetics 127). The

“interdiscursivity” of narcissistic texts flashes the mounting awareness of their cultural and

ideological inscription and of the impossibility of determining definite lines of separation

between the numerous discourses of a given culture (130). It does not seek in any sort of way

to camouflage these ontological lines as it really endeavors to highlight them. Such a narrative

occupies the borderline through positing itself on the edges of many oppositional poles, never

favoring or prioritizing one to another, nor ceasing to pose endless questions about them. The

narrative self-consciousness alludes to its own perpetual self-questioning and self-evaluation.

It never refrains from posing all kinds of queries about its ontological status aiming not at

clear-cut answers or compromises but rather at exposing its ambivalences and

“problematizing” the nature of all forms of writing and knowledge in general. Hence, one can

refer to the “problematics” of narcissistic narratives rather than to its “poetics” (222).

III. Narcissistic narrative: the introduction of the typology:

Studying narcissistic narratives that is fiction reflecting on its own genesis and

mirroring the strategies of fictional writing and fictive world’s construction entails a

movement inward to the recesses of the work itself. This analysis is chiefly based on Linda

Hutcheon’s study of poetics, politics and narcissism of postmodernist texts. Accordingly,

Hutcheon outlines two levels of metafictional underpinning, one is “diegetic narcissism”

occurring at the level of narration and narrative techniques and the other is “linguistic”

indicating an awareness of the medium used in fiction which is language, and of its power as

well as its limits (Narcissistic 23). In relation to both levels, there are two varieties of

narcissism: “overt and covert modes” (56). Thereby the four main categories of narcissistic

texts are as follows: “overt diegetic narcissism, overt linguistic narcissism, covert diegetic

narcissism, and covert linguistic narcissism” (23). Overt narcissism is palpable diegetically

through the fictive self-awareness of the narrative status as a literary artifice and the laying

bare of its fiction making processes using self-reflective devices such as parody, mise en

abyme and intertextuality (25).

Parody, one of the major literary devices in postmodernist writing, conforms to the

very nature of narcissistic narrative, since it enacts self-reflexivity through the double

movement of “appropriation” and subversion (128 my emphasis). “Parodic art”, as Hutcheon

outlines, “is both a deviation from the norm and includes the norm within itself as

backgrounded material” (50). The dual ontological status of the narrative is pointed out

through parody which works to background a given convention in an attempt to foreground

the “new creation” and the way in which it may be “measured and understood” (Hutcheon,

Theory of Parody 31). New literary conventions evolve in fact from previous ones and

postmodern texts in particular acknowledge such a give-take movement through setting a

dialogue with these conventions and criticizing them in order to aspire to new forms of

literary construction. Henceforth emerges the view of parody as a “prototype of the pivotal

stage in that gradual process of development of literary forms” (35). Hence metafictions

cannot mirror their own mechanisms of construction while ignoring previous literary

productions since their own emergence is due to their dialogic relation with the past in

general. Such a dialogue is given legitimacy through the employment of parody which is

“both a personal act of suppression and an inscription of literary-historical continuity” (35).

This continuity is marked mainly by the use of irony which signals out that this return is not

an innocent “nostalgic return”, yet it is rather triggered by an intensive “critical awareness”

(Hutcheon, “Irony, Nostalgia, and the Postmodern” 3). Umberto Eco has, for instance, called

this ironic postmodernist twist “the age of lost innocence” where “the postmodern reply to the

modern consists of recognizing that the past, since it cannot really be destroyed, because its

destruction leads to silence, it must be revisited, but with irony, not innocently” (qtd. in Currie

174). Hence, the use of parody reflects a consciousness of the mechanisms of literary

constructions and their evolvement in accordance to each other and never in isolation. It does

not conceal as far as it reveals past conventions in its formation of a new poetics.

Using Genettian terminology to account for the meaning of mise en abyme, it can be

said that the latter device refers to the embeddedness of a “second degree narrative or meta-

diegesis”14 in the “first degree narrative” or diegesis (Narrative Discourse 231). Palpably, this

writing device works on the level of the diegesis. In order to further clarify this concept, it is

substantial to go through Lucien Dällenbach’s thorough study on metafictional texts and what

he calls “its mirrors”. In “Reflexivity and Reading”, Dällenbach defines mise en abyme as “a

doubling which functions as mirror or microcosm of the text” (435). He goes further in

outlining three types of mise en abyme: “simple reduplication, repeated reduplication, and

14 In order to determine the narrative level to which an event relates, it has to be considered that “any event a narrative recounts is at a diegetic level immediately higher than the level at which the narrating act producing this narrative is placed” ( Genette, Narrative Discourse228).

aporistique doubling” (qtd. in Hutcheon, Narcissistic 54). According to Dällenbach, “simple

reduplication” operates at the level of the storytold or enoncé15 (54). It is a narrative fragment

that replicates the plot of the story that contains it (54). “Repeated reduplication” implies that

the narrative fragment “bears within it another mirroring fragment and so on” ad infinitum

(56). This regress displays that the enoncé or the narrative as such reflects on the

enunciation16 or the narration itself that is in the process of production carried by the producer

as well as the receiver. The “aporistique doubling includes the work in which it is itself

included” and here accordingly both levels, the linguistic and diegetic, are reduplicated (56).

These different types of mirrors, often incorporated in the work of fiction, take the form of

novel, story, movie, drama, musical, TV serial…

Overt linguistic narcissism, on the other hand, is depicted through the “thematization

of language” and linguistic issues in the narrative. This explicitness works to position

fictionality, the mysteries of language and language use, and the self-consciousness at the core

of postmodernist fiction as well as to place the reader in a bewildering space where he is

overtly taught his or her contributory role through the thematization of the act of reading itself

(71). On the other hand, covert narcissism can either be structuralized or “internalized”

within the text and necessitates “actualization” on the part of the actively participating reader

(7). Such implicitness requires an active response to itself through the “process of

actualization” that takes place at the act of reading and transforms words into fictive and

literary worlds (Iser 20). Here, “the dyadic interaction” that relates the aesthetics of

production and response are triggered in order for meanings to be “optimized” (85),

“concretized” (178), and “actualized” (66) through the reader’s interactive response to “the

15 The enoncé “signifies what is uttered (the statement, the proposition)” in speech or writing (Barthes, Image Music Text 9).

16 The enunciation “signifies the act of uttering (the act of speech, writing or whatever by which the statement is stated, the proposition proposed)” (Barthes, Image Music Text 9).

verbal structure” of the text. The reader is no longer a passive agent who reads in order to

decode the message that the author has encoded in the text, he is rather an active force which

participates in the process of meaning construction (41). “Page by page the reader creates the

meaning of the text, reshaping, and reordering former unities into new ones as he proceeds”,

transforming the text from a mere aesthetic object to an elaborate performance ( Hutcheon

Narcissistic 145). The authorial intention and objectivity are no longer tenable in a

postmodernist self-critical and discursive context and hence the assertion of the centrality of

an “enunciating subject” is overtly denounced. The concept of subject, self, and subjectivity

are, therefore, highly criticized in a center-free postmodern context (Selden and Widdowson

177). Enunciation, which is the focal point in narcissistic narratives, requires an enunciating

producer and a Brechtian receiver, and the communication between both parts in a context-

dependent situation. For instance, Iser opines that “the pragmatic nature of language” which

depends on the act of enunciation as such “has developed concepts which, although they are

not meant to be applied to fiction, can nevertheless serve as a starting point for our study of

the pragmatic nature of literary texts” (54). The trajectory of meaning actualization has shifted

from the enoncé to the act of enunciation, from the product to the process, from langue to

parole, from fixed codes and conventions to ever-changing performance, and from

semiotization to pragmatism. This pragmatism puts into consideration what Benveniste calls

“language put into action”, that is the contextual and situational underpinnings of language

(qtd. in Hutcheon, Poetics 82). Lyotard sums up this view saying that “a self does not amount

to much, but no self is an island; each exists in a fabric of relations that is now more complex

and mobile than ever before… A person is always located at ‘nodal points’ of specific

communication circuits” (15). Since literary language operates in the same way as everyday

speech and implies a performative function, it could be subject to pragmatic interpretation.

Searle, for instance, views literature as an imitation of a speech act (60). The aim of literary

language here does not revolve around “what it says” that is the content itself, but rather

“what it does” that is how it affects the receiver and constructs meaning (Iser 26).

Wolfgang Iser’s theory of “aesthetic response” or “dyadic communication” which

treats the text as a performative act and Wayne C. Booth view of literature as an “art of

communication” seem to be the closest and the most relevant to the needs of metafictional

criticism (Hutcheon, Narcissistic 147). To read is “to act” and consequently to perform

thereby opposing any claim to a fixed structure or a unilateral kind of response (Iser 62).

Since no performance can be repeated in the same way, each reading becomes an anti-

representational force in the sense that it cannot proceed in a similar unique way making from

the end of one reading the beginning of another one. Narcissistic texts, therefore, rely on both

productive-responsive aesthetics in order to “concretize” its meanings and in the “endless

unfixed systems of signification” to construct its open uncontrollable processes.

The theoretical framework of this thesis offers a laconic approach to metafictional

narcissism in general, a definition of its major key concepts, and an exploration of its major

topoi. Indubitably, this chapter serves the upcoming analysis by providing the key parameters

that back up the dissertation as a whole. Accordingly, Lot 49 lends itself perfectly to the

metafictional narcissistic approach as the study of its diegetic identity is going to reveal in the

second chapter.

The self-consciousness of literary texts is not a simple one-sided task that exclusively

requires the text to be a connoisseur of its own literary ground; it is rather highly problematic

demanding constant negotiation between disparate fields of study. The problematizition stems

chiefly from the paradoxical nature of postmodern narcissism which aspires to go beyond the

confining claims of self-sufficiency and autonomy of the work of art. The narcissistic text

overtly acknowledge its pluralistic, cohesive and symbiotic ontological status as a literary text

existing indispensably in a context, consisting of an intertext as well as a metatext17, grouped

according to paratext18 and hypertext19, resulting in a multifaceted zone of cross-fertilization.

This criss-cross pattern has numerous implications on the definition of literature, history, and

reality in general as it is going to be argued for in the forthcoming analysis. Hereupon,

metafictional texts chart the history of artistic creation or poesies20 in tandem with the poetics

and theories of criticism while adopting a critical standpoint. Novelistic narcissism,

consequently, implies the self-awareness of the “intramural textual level” as well as

“extramural” processes, showing the encounter and the permissible co-existence of multiple

paradoxical fields into one inclusive literary text (Hutcheon, Narcissistic 19).

17 Metatextuality refers to “the transtextual relationship that links a commentary to ‘the text it comments upon (without necessarily citing it)’”. In Architexte, Genette remarks that “all literary critics, for centuries, have been producing metatext without knowing it” (82). (Paratexts: Threshold of Interpretation xix).

18 Gérard Genette defines the paratext as “a threshold. It is an ‘undefined zone’ between the inside and the outside, a zone without any hard and fast boundary on either the inward side (turned toward the text) or the outward side (turned toward the world's discourse about the text), an edge, or, as Philippe Lejeune put it, “a fringe of the printed text which in reality controls one's whole reading of the text” (Paratexts: Threshold of Interpretation 2).

19 The hypertext denotes “the ‘literature in the second degree’: the superimposition of a later text on an earlier one that includes all forms of imitation, pastiche, and parody as well as less obvious super impositions” (Genette, Paratexts: Threshold of Interpretation xix).

20 Poesis is defined by David Lodge as follows “art as making, a contrivance for affecting the methods- the ‘Skill or Crafte of making’ as Ben Jonson called it… [are] comprehended under the term poesies” (qtd. in Abrahms 12). Hutcheon puts it more straightforwardly in Narcissistic as “the process of making” (20).

As this chapter aims at studying the diegetic narcissism, an account of the meaning of

the word “diegesis” is of cardinal necessity at this level. Derived from the Greek verb

“diegeisthai”, diegesis means “‘to lead/ guide through’ … which came to mean ‘give an

account of’, ‘expound’, ‘explain’, and ‘narrate’” (Halliwell 3). It actually refers “in the Greek

origin, to the narratorial discourse, that is to the act of telling, rather than to the story (the

muthos)” (Phelan 40). With the advance of narratological studies, diegesis comes to be known

as “the universe in which the story takes place” (Genette, Narrative Discourse 17). In

Narrative Discourse: an Essay in Method, Gérard Genette distinguishes between “story”,

“narrative”, and “narration”. According to his thorough study, story designates “the signified

or narrative context”, narrative stands for “the signifier, statement, discourse or narrative text

itself”, and narrating refers to “the producing of narrative action and by extension the whole

of the real or fictional situation in which that action takes place” (27). Drawing on this

distinction, diegesis encompasses both categories of narrative and narration coming to mean

the narrative text and its processual production. It is also multifaceted since it includes the

category of “narrative level” (intradiegetic, extradiegetic) as well as that of “person”

(homodiegetic, heterodiegetic) (215). The choice of the word diegesis over narrative shows

the intentional inclusive impulse and intent of this study and its “rejection of the split between

process (the storytelling) and product (the storytold)” (Hutcheon, Narcissistic 5).

Lot 49 is an exemplar of narcissistic metafiction since it displays most of its features

mainly through its implication of self-reflexivity at the level of diegesis and its exploration of

the processes of reading and writing. This narcissism is present in the novel and takes both

forms overt and covert; overt in its use of parody, mise en abyme, and intertextuality and

covert in its embedding of metafictionality, self-mirroring and its calling for the actualization

of these elements through the “dyadic interacti[ve]” act of reading (Iser 59). The first chapter

aims at analyzing both forms while endeavoring to stress how postmodern fiction is an art of

sincerity which brings deliberately its own processes and mechanisms into light.

I. The Parodic double-coding of Lot 49:

The study of parody aims at double-coding the text through the exploration of both the

subversive as well as the conservative aspects of parody. Lot 49 parodies, in fact, the realistic

mimetic view of art, the structuralist strict generic classification of literary works, and the

modernist ahistoricism of literature.

1. Process and Product: Narcissistic takedown of realism

Thomas Pynchon’s turn away from realism is marked by his parodic treating of the

tenets of this literary trend. Lot 49 aims at reworking realist conventions, especially those

concerning the prominence of the aesthetic product, the completeness and closedness of the

novel, the linearity and causality of the plot, and the ability to represent external truth. The

direct result of this critical reworking is the deconstruction of the fiction-reality relationship

and the employment of fragmented non-linear narrative commensurate with the contingent

pluralistic view of reality. The literary realist world of “ontological certainties” (Mchale 66)

and “aesthetic fetishizing” is, therefore, decentralized by postmodernist contingency and

constant questioning (Hutcheon, Poetics 66).

As accounted for in the introduction of this dissertation, the summary21 of the novel

accentuates the on-going quest for truth that is the process of meaning-making rather than the

resolution of the mystery itself that is the final product of the quest. At the end of the

narrative, the quest remains unvoiced and the denouement of the mystery unresolved, leaving

the end open. Seemingly, Lot 49 abides by the realist convention of narrative linearity,

drawing causal relationships between some of the occurrences at the very beginning. The

novel starts in “one summer afternoon” in Kinnert, exposing a casual day of an American

housewife, who has been in a Tupperware party and arrives home to find out the news of

21 See the Introduction of this dissertation p. 3-4

Inverarity’s death and her nomination as an executrix of his estate. Events flow after in a

logical way:

[t]hings then did not delay in turning curious. If one object behind her

discovery… were to bring to an end her encapsulation in her tower, then that

night’s infidelity with Metzger would logically be the starting point for it;

logically. That’s what would come to haunt her most, perhaps: the way it fitted,

logically, together. (Pynchon 31, my emphasis)

Soon after, this logic veered toward an escalating non-logic, showing Oedipa’s oscillation

between interconnected events and unexpected happenings. To her, everything “seemed to

come crowding in exponentially, as if the more she collected the more would come to her”

(64). She is, in fact, put in the middle of nowhere and doomed to get to an indeterminate

destination through following the path of infinite open possibilities as suggested by the surfeit

of disparate occurrences. Whenever she seems to approach an end, more events and

information come to her resisting any claim to a logical denouement and opening itself “to all

the possibilities” (148). Oedipa’s entrapment in this labyrinthine endless structure where

events pile up in an infinite way reflects Lot 49’s continuous stratification and structural

redoubling. Lot 49, in its turn, “is about to be broken up into lots” resisting any claim to

progression toward an ultimate meaning (32). It is a narcissistic narrative that acknowledges

its fragmented nature and “byzantine plot full of improbable coincidences and outrageous

action” (McCaffrey 22).

In opposition to realistic texts, narcissistic texts do not exclusively direct their readers’

attention to the finish, but instead they usher them to the broader and tendentious space of end

and process. In this context, Hutcheon assumes “in metafictional narcissism the focus [on

product] does not shift, so much as broaden” to encompass the process of meaning-production

(Narcissistic 27). Oedipa begins her journey penchant for hearing the “cry that may abolish

the night” (Pynchon 95, my emphasis), yet she ends up waiting for the “crying of lot 49”

(152, my emphasis). The choice of the “–ing” verb form wittingly shows the continuous

deferral of the end since whenever Oedipa succeeds in finding some clues, the latter lead her

to other ad infinitum clues depriving her of any possibility of attaining comfort through a

consolatory sense of an ending. Hereupon, the “–ing” form that denotes progression and

incompleteness of an action is the most commensurate with the postmodern narcissistic

theoretical framework which remains “an unfinished project” that defies any claim to a fixed

definition or to a determinate set of poetics. Narcissism is still at the stage of “theorizing/

modeling/ limiting/ decentering/ contextualizing/ historicizing” as the titles of the chapters of

Hutcheon’s Poetics show, or is still in the stage of construction as Mchale study Constructing

Postmodernism outlines. This emphasis on the processes of fiction making is, in fact,

reminiscent of Bertolt Brecht’s “Epic Theater”22 which assigns to the literary performance a

subversive force capable of discomforting the receiver and directing him or her towards the

conscious exercise of interrogation and criticism (Selden an Widdowson 79). Similar to the

Brechtian theater, narcissistic texts “place the receiver in a paradoxical position, both outside

and inside, participatory and critical” (Hutcheon, Poetics 219). Directing the focus towards

the narrative process rather than to the finish raises the audience awareness of the artificiality

of art through the “alienation effect” which denounces any possible act of identification with

fictional characters and hence keeps their eyes wide open and their minds critical of what they

receive (Selden and Widdowson 79). Accordingly, value is attributed to the demystification of

the processes of artistic production and reception rather that to a “fetishized fixed meaning”.

22 “‘Epic theater’ means, simply, a theater that narrates, rather than represents… Brecht felt that to foster a state of relaxation in the theater – an atmosphere in which reason and detachment, rather than passion and involvement, were to predominate – was to subvert the established theater and ‘Aristotelian’ plays that were performed in it… The ensemble of these measures is to produce the famous Verfremdungseffekt or ‘alienation effect’. This concept… shifts critical attention from ‘affekt’ to ‘effekt’ …. The emphasis of Brecht’s work is upon discontinuity. No chain of events is held together by a natural or self-evident logic; the spectator is to experience the constant disruption of narrative structure, as one device undercuts another” (Childs and Fowler 70-2, my emphasis).

Lot 49 therein brings to the fore its own processes of “artistic and aesthetic production23”, or

those of writing and reading a literary text (Iser 21). This “self-demystifying” process

palpably foregrounds that “the ‘narration’” ultimately “invades and pervades the ‘fiction”

(Hutcheon, Narcissistic 35). The traditional realistic interest in fiction as an aesthetic product

is decentralized and highlighted by an overt turn away from the storytold, the focalized, and

the narrated to the constructive realm of storytelling, focalization, and narration (35). What is

of cardinal interest for the writer as well as for the reader in a literary work is not what the

text is about, but rather how the discursive constituents of the fictional universe are co-

created, constructed, and actualized. Subsequently, the focus twists from the “what” to the

“how”.

The text draws attention to the creative processes of fiction writing and reading

attributing particular importance to the reader as an active meaning processor rather than

passive receiver as Hutcheon assumes “the novel no longer seeks just to provide an order and

meaning to be recognized by the reader… It now demands that he be conscious of the work,

the actual construction that he is undertaking, for it is the reader who… ‘concretizes’ the work

of art and gives it life” (Hutcheon, Narcissistic 39). In realistic literature, the authorial

intention24 and full omnipotence of the narrator insures the centrality of meaning in the pole