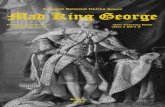

The Auction of King William's paintings - Selection

Transcript of The Auction of King William's paintings - Selection

OCULIStudies in the Arts of the Low Countries

Series Editors:

Eric Jan SluijterUniversiteit van Amsterdam

Jennifer M. KilianAmsterdam

Volume !!

"#$%&''( )#%*"+$$&$

, + $ ' - * , . # % # / " . % 0 1 . 2 2 . ' 3’4

5 ' . % , . % 0 4!6!7

$2.,$ .%,$&%',.#%'2 '&, ,&'($ ', ,+$ $%(

#/ ,+$ (-,*+ 0#2($% '0$

)#+% 8$%)'3.%4 5-82.4+.%0 *#35'%9:;;<

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Jonckheere, Koenraad. The auction of King William’s paintings (!6!7) : elite international art trade at the end of the Dutch golden age /Koenraad Jonckheere. p. cm. -- (Oculi : studies in the arts of the low countries, ISSN ;=:7–;;77; v. !!)English translation of the dissertation defended at the University of Amsterdam in Sept. :;;>.Includes bibliographical references and indexes.ISBN =6<-=;-:6:-?=@:-7 (hb : alk. paper) -- ISBN =6<-=;-:6:-?=@7-; (pb : alk. paper)!. William III, King of England, !@>;-!6;:--Art collections. :. Painting--Private collections--Netherlands--Amsterdam. 7. Art auctions--Netherlands--Amsterdam--History--!<th century. ?. Painting--Collectors and collecting--Europe--History--!<th century. >. Art--Marketing--History--!<th century. I. Title.N>:6:.:.W>>J>> :;;<6;6.?’?=:7>:--dc:: :;;6;?=!!6ISBN =6< =; :6: ?=@: 7 (Hb, alk. paper)ISBN =6< =; :6: ?=@7 ; (Pb, alk. paper)

© :;;< – John Benjamins B.V. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, photoprint, microfi lm, or any other means, without written permission from the publisher.

John Benjamins Publishing Co. · P. O. Box 7@::? · !;:; ME Amsterdam · The NetherlandsJohn Benjamins North America · P. O. Box :6>!= · Philadelphia PA !=!!<-;>!= · USA

! ™ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirementsof American National Standard for Information Sciences —Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z"#.$%–&#%$.

This book was published with the support of:

%1#

The Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art

4.,'

Dr. Hendrik Muller Vaderlandsch Fund

M.A.O.C. Gravin van Bylandt Foundation

Cover illustration: Simon Fokke, An auction in the Oudezijds Herenlogement.Pen and brush on paper, :>.? x :@.? cm, Amsterdam, Gemeentearchief

76

!. ‘Anno !@@6: den :6. Januari Donderdag avond tusschen = en half !; is Jan geboren, en den 7;de gedoopt in de Westerkerk’ (The year !@@6: the :6th of January, Thursday evening between = and =:7; Jan was born, and baptised in the Westerkerk on the 7;th) his father recorded in the family register. Quote from Van Beuningen van Helsdingen !<<6, pp. !7!-!7:. See also Frederiks !<==, pp. !>=-!@:. The author describes a set of annotations on parchment concerning the Jan van Beuningen family, which he confused with those of the states-man Coenraad van Beuningen (!@::-!@=7). The an-notations were penned by Hendrik van Beuningen (father) and Isaac Samuel van Beuningen (brother).

". Van Beuningen n.d., pp. !:;-!6@; Elias !=@7, vol. ., pp. 7?:-7?>.

#. ‘Onijndige Expedietio, met lust en vuur volbragt, zijn sooveel getuijge van mijn altoos waakende ijver, [...] Die wel reekent, en wijnig slaapt, mist selde in het berijke van sijn doel.’ Jan van Beunin-gen, Amsterdam, :; December !6!:. Leeuwarden, Tresoar (RAF), Stadholder’s Archive, Archive of Maria Louise von Hessen-Kassel, inv. no. !=, Let-ter from Jan van Beuningen to Maria Louise, !" Decem-ber #$#!.

$. I am grateful to Piet Bakker for notifying me of a number of letters by Jan van Beuningen in the Royal Archives in The Hague.

%. The Hague, KHA, Archive of Maria Louise von Hessen-Kassel, inv. no. 7><, Letter from Jan van Beu-ningen to Maria Louise, % February #$#&.

diplomats on the one hand and the Dutch art-loving milieu on the other. Countless archival documents sketch a subtle image of the man who because of his experience in this area was considered the person best suited to run the most pres-tigious auction of his day.

*-&&.*-2-3 A.,'$ – Jan van Beuningen was born in Am-sterdam in !@@6 to the merchant Hendrik van Beuningen and Maria Le Thor, who came from a distinguished Amster-dam family of merchants.? Jan was the oldest of their nine children and grew up on the Singel.> His paternal grandfa-ther hailed from Nijmegen, but emigrated to Danzig in the fi rst half of the seventeenth century. The family accrued a certain wealth by selling grain from the Baltic region to the Republic. The fi rm sent the oldest son, Jan’s father Hendrik, back as a factor to Amsterdam, where he ultimately stayed.

O% ? F$8&-'&9 !6!7, Jan van Beuningen wrote ‘I fully ex-tend my services’ (Ik oB re mij in alle dienst), to his patron-ess Maria Louise von Hessen-Kassel.7 This statement refers to his appointment as director of the auction of the paint-ing collection of Stadholder-King William ... from the gal-lery at Het Loo Palace held eleven years after the monarch’s death. As the director of this auction, the Amsterdam art lover would steer it in the right direction. To gain a better understanding of this auction and the in-ternational art trade in this period, it is worthwhile delv-ing deeper into the person of Jan van Beuningen. From the source material, he emerges as someone who played a key role in the formation of several aristocratic picture collec-tions in Germany and England. In the course of this book it will become clear just how crucial Jan van Beuningen and other agents were as links between princes, noblemen and

*+'5,$& :

,+$ #&0'%.4',.#%#/ ,+$ '-*,.#%

'. ,+$ '&, 2#A$& '%( ,+$ 8&#"$&‘This never-ending mission, completed with passion and fi re,is the witness of my ever vigilant zeal [...].He who calculates well and sleeps little, rarely fails to achieve his goal.’!

,+$ (.&$*,#&4+.5 #/ 3$&*+'%, '%( (.52#3', )'% A'% 8$-%.%0$%:

7<

$# Johan Gole, Portrait of Jan van Beuningen, engraving, 7?.> x :>.; cm, c. !6!>, Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinet, inv. no. RP-P-!=;=-!7=7

7=

&. Amsterdam, GAA, access number >;66, Exchange Bank Archive (uninventoried).

'. Amsterdam, GAA, access number >;66, Exchange Bank Archive (uninventoried).

(. Van Beuningen n.d., p. !7;.). Van Beuningen n.d., pp. !@>-!@=.

drik died in !@=6, his widow and their sons took over the business. Finally, at a relatively late date, Jan set up his own company operating under his own name.6

Jan van Beuningen married Catharina Constantia van Leeuwen in !@=>.< The couple had seven children. The old genealogical table of the family informs us that they re-mained highly internationally oriented. Naturally, there were close contacts with the relatives in Danzig. However, family members were also domiciled as factors elsewhere. Two of Jan’s brothers – Isaac Samuel and Jonathan – were dispatched to London and Curaçao, respectively. Jonathan was a governor of the West-Indian island from !6!@ to !6:;. Isaak Samuel stayed in England as a business partner for some time.= Jan van Beuningen, thus, was charged with the weighty responsibility of managing the family’s trad-ing company from Amsterdam. In addition to the Baltic Sea trade, which given the family ties with Danzig was self-ev-ident, Jan van Beuningen was also actively involved in in-

Jan van Beuningen was privileged to a fi ne education. From the correspondence it emerges that he was classically trained and wrote relatively good French. His letters are liberally sprinkled with Latin mottos and phrases. He used the mag-ister’s title, which suggests he read law at university. Natu-rally, as the merchant’s oldest son he would also have been trained to take over his father’s business. The Current Ac-count Ledgers of the Amsterdam Exchange Bank confi rms that this was, indeed, the case. Hendrik and his children had an account there under the name ‘Hendrik van Beuningen and sons’ (Hendrik van Beuningen en zonen).@ When Hen-

$$ Pieter van den Berge after Gérard de Lairesse, Achilles among the daughters of Lycomedes, engraving, ><.> x ?>.@ cm, c. !@=>, Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinet, inv. no. RP-P-!=;?-?7@!

?;

The culmination of Jan van Beuningen’s ambitions was undoubtedly the fact that on :> March !6!7 – thus shortly be-fore the auction – he was raised to the peerage by Emperor Charles A..!? ‘When, years ago, a great fi re broke out here and our house, our furniture and all our personal belongings – among other things our patents of nobility – were lost [...],’ he began his letter to the emperor of : March !6!7.!> Thanks to the mediation of Anton Ulrich von Braunschweig, the ‘renovatio nobilitatis’ was clinched less than a month later. Just how proud he was of this tribute can be deduced from the portrait Johan Gole engraved of him around !6!> (fi g. :!).!@ It depicts Jan van Beuningen in the same pose as Em-peror Charles A in the famous likeness by Titian.!6

Van Beuningen proved to be an art lover already as an ad-olescent. He fi rst presented himself as a patron in !@=>. In that year Pieter van den Berge published a series of prints of paintings by Gérard de Lairesse. The engraving after Achil-les among the daughters of Lycomedes bears a dedication to Jan van Beuningen (fi g. ::).!< Ovid’s lines of verse about Achil-les’ fortunes gird the coat of arms.

dustry as appears from the fact that he owned a brick kiln along the Vaartse Rijn in Utrecht certainly as of !@<=.!; He also owned plantations on Curaçao.!!

At the same time Van Beuningen’s star was rising in pub-lic oC ce in Amsterdam. In !@=> he was a bookkeeper of the Dutch East-India Company (A#*) and of the Exchange Bank.!: Both positions put him at the very heart of the fi nan-cial world of the Republic. On the board of the A#* he be-came familiar with speculations in stocks. At the Exchange Bank he surely will have met the Republic’s wealthiest mer-chants and representatives of foreign bankers. In !6;? Van Beuningen was commissioner of the Post OC ce, a lucrative and rewarding position. Two years later he was a lieuten-ant of the civic guard and in !6;= a captain. In !6!: he was appointed a director of the West-India Company (WIC).!7 Three years later he became governor of Curaçao, relieving his younger brother Jonathan. He sailed out on !7 May !6:; and set foot on the island on ? July. He held this post for a mere two months: for he died on the West-Indian island on !< September !6:;, followed by his widow only a few months later.

van Leeuwen with a four line inscription by Jan van Beuningen.

$'. ‘Les instigateurs de cette lotterie etoient de cer-taines gens qui possedoient je ne scai quelles Sei-gneuries, & biens immeubles, qui leur apportaient fort peu de revenu [...] la étans contraint de les vendre par une urgente & absoluë nécessité d’ar-gent & ne pouvans cependant trouve personne qui voulît les acheter, l’example de la lotterie de Lon-dres leur fît naitre la pensée d’en faire une pur ce-la.’ Leti !@=6, pp. !7=-!@<.

$(. Amsterdam, GAA, access number >;66, Ex-change Bank Archive (uninventoried), Current Ac-count Ledger !;6, vol. : account no. !??! B ., Cur-rent Account Ledger !;<, vol. : account no. !??! B ., Current Account Ledger !;=, vol. : account no. !??! B . A certain Elias was also involved. I was un-able to identify him convincingly.

$). ‘On vit arriver a Amersfort une afl uence incroy-able de Peuples, ce qui n’est pas fort surprenant [...] on ne voyoit par les Rues que des Chariots en des Chaizes roulantes & sur les Canaux que des Barques remplies de gens.’ Leti !@=6, pp. !7=-!@<.

%*. Fokker !<@:, pp. !;;-!;@; Huisman & Kopper-nol !==!, pp. !;>-!;<. The authors confuse this lot-tery with one organised a few months later by a number of other initiators that was much less suc-cessful. From the archives in the Exchange Bank of Amsterdam and the descriptions by Leti it clearly emerges, however, that Van Beuningen, Nijs and Elias were the very fi rst to devise a lottery mod-elled on that of William ... in London held a year earlier.

%#. Elias !=@7, vol. .., pp. <!:-<!?.

#(. Pieter van den Berge after Gérard de Lairesse, Achilles among the daughters of Lycomedes, engraving, ><> x ?>@ mm, c. !@=>, Amsterdam Rijksprenten-kabinet, inv. no. RP-P-!=;?-?7@!. On the series of prints, see Van Tatenhove !==6, pp. !@-:6. On the print and the painting, see Broos !==>, pp. :!-:@; The Hague !==7b, pp. !6:-!6=.

#). ‘Treurspel, voor het meerder gedeelte berijmt was door den Heere Jan van Beuningen, en mij voor zijn Wel-Edelhere vertrek naar Curaçao ter-hand gesteld [...].’ Van Beuningen et al. !6:7.

$*. Haverkamp & Péchanterés !6;=.$#. Von UB enbach !6>?, vol. .., p. ?!<; Von UB en-

bach !6>?, vol. ..., p. 7?!.$$. Houbraken !6!<-!6:!, vol. .., p. :=; Von UB en-

bach !6>?, vol. ..., p. 7??.$%. The Hague, KHA, Archive of Maria Louise von

Hessen-Kassel, inv. nos. 7>< and 7>=, Letters from Jan van Beuningen to Maria Louise, #$#&-#$#'. Leeuwar-den, Tresoar (RAF), Stadholder’s Archive, Archive of Maria Louise von Hessen-Kassel, inv. no. !=, Let-ters from Jan van Beuningen to Maria Louise, #$#!.

$!. Adinolfi !==?, pp. :6-77; Van Eeghen !=@<, pp. 6?-!;!.

$". Dudok van Heel !=6>, pp. !?=-!67. Gerbrandus’ brother-in-law and the uncle of both sisters was Ferdinand van Collen, Burgomaster of Amster-dam. Elias !=@7, vol. ., p. 7?7. Isaac Jan Nijs was also married to a scion of the Van Collen family, namely Susanna. Van Eeghen !=@<, pp. 6?-!;!.

$&. Van Miert :;;?, pp. 7?6-7>;. In the Library of the Vrije Universiteit (VU) in Amsterdam is a por-trait engraving (Portret !.LEE.;;!) of Gerbrand

#*. Utrecht, GAU, NAU, inv. no. U!!@a! deed >;, Agreement regarding the closing down of the brick kilns due to the threat of overproduction, #( February #()*. Utrecht, GAU, NAU, inv. no. U!!@a! deed >:, Agree-ment regarding the closing down of the brick kilns due to the threat of overproduction, # June #()*. Utrecht, GAU, NAU, inv. no. U!!;a7 deed ::@, Agreement regarding the termination of a lease on a house on the Vaartse Rijn, #* November #(*#. He proved to be a good business-man. He reached agreements concerning prices and production with other brick kiln owners. In other words, he set up a cartel.

##. Van Beuningen n.d., p. !7:.#$. Utrecht, GAU, NAU, inv. no. U!::a! deed !@:,

Dispute concerning a lost box, * October #(*'. Utrecht, GAU, NAU, inv. no. U!:>al deed 7?, Procuration for collecting a bill of exchange, #! November #(*'.

#%. Broos !==>, pp. :!-:@.#!. Elias !=@7, vol. ., pp. 7?:-7?7. A transcript of the

patent of nobility is in the National Archives. The Hague, National Archives, Archive of the Van Beu-ningen Family, inv. no. :.:!.:7;: Archive of Jan van Beuningen, no. !.

#". ‘Wann aber der für Jahren alhier entstandene Grosse Brand auch unser Hauss und alle Meubels ja fast alle Habseligkeiten und unter andern auch unsere Documenta Nobilitatis uns dergestalt con-sumiert [...].’ Van Beuningen n.d., pp. !7:-!??.

#&. Johan Gole, Portrait of Jan van Beuningen, engrav-ing, 7?> x :>; mm, c. !6!>, Amsterdam Rijkspren-tenkabinet, inv. no. RP-P-!=;=-!7=7.

#'. Titian, Portrait of Charles A with a dog, canvas, !=: x !!! cm, Madrid, Museo del Prado.

?!

berg. In !6!7 he married Elisabeth van Leeuwen, the sister of Jan van Beuningen’s spouse, Catharina Constantia. Their fa-ther, Gerbrandus van Leeuwen, was a professor of theology at the Athenaeum Illustre, from which the University of Am-sterdam later originated.:@

The earliest collaboration between Jan van Beuningen and Daniël Nijs took place long before they became related through marriage. In !@=> they organised the so-called ‘lot-tery of Amersfoort’ (loterij van Amersfoort). A contemporary described them as follows: ‘the organisers of the lottery were certain people who owned I don’t know which manors and eB ects that brought them only a modest income [...]. Being forced to sell them due to an urgent and utter need for cash and fi nding no one who would buy them, the example of the lottery of London inspired them to hold their own [lot-tery] to this purpose.’:6 Approximately !@,;;; lots were is-sued at :> guilders a piece. Accordingly, the organisers of the lottery were counting on a turnover of at least ?;;,;;; guil-ders! They fell just short of that amount as appears from the receipts for the lottery in the archives of the Amsterdam Ex-change Bank.:< More than 76=,>;; guilders worth of notes were sold, and more than !>,;;; lots – which, after all, were expensive – were sold throughout the Republic, the South-ern Netherlands, Germany and England. The name of just about every regent family appears in the list of subscribers. Foreign noblemen and diplomats bought dozens of lots. As planned, the draw began on !> February !@=>. It lasted more than a month. ‘One saw arriving in Amersfoort an incredi-ble stream of people, which is not all that surprising [...], the streets were teeming with carriages and “chaises roulante” and the canals were fi lled with boats packed with people,’ wrote eye-witness Gregorio Leti two years later.:= Amers-foort was overrun for days. This lottery sparked oB a veri-table rage of smaller and larger such events in the Repub-lic after 6; years of relative calm in this respect.7; It was an unexpected success, which must have procured its initiators years of fame and probably also certain wealth. It cannot be determined exactly how much they earned from this endea-vour, but given the turnover it must have been a tidy sum. It bespeaks both the entrepreneurial spirit of the organis-ers and Jan van Beuningen’s ability to successfully run large events, a skill that surely stood him in good stead later with the organisation of the Het Loo auction.

Not only did he have an infl uential family, Van Beuningen could also rely on an extensive network of friends and ac-quaintances. The name of Pels surfaces frequently in archi-val material relating to Van Beuningen.7! According to con-temporaries, the family then operating under the company name ‘Andries Pels and Sons’ (Andries Pels en Soonen) was

Poetry and painting continued to dictate Jan van Beunin-gen’s cultural life. He did more than only assemble a nota-ble picture cabinet. Later, he also found time to translate Prosper Jolyot de Crebillon’s tragedy, Idoménée (!6;>), the fi rst edition of which appeared in !6:7. Jacob Voordaagh, who completed the rhyming translation after Van Beunin-gen’s death, wrote in the foreword that the ‘Tragedy, was largely set to rhyme by Mr Jan van Beuningen and me be-fore his Excellency’s departure for Curaçao [...].’!= A trage-dy by Nicolas de Péchantrès of !6;7, translated by the writer Jan Haverkamp, De dood van Nero (The death of Nero) in !6;=, was dedicated to ‘the honourable Mister Jan van Beunin-gen’ (den Edele Heere Jan van Beuningen).:; It bespeaks his engagement in the cultural life of the Republic of his day. However, Jan van Beuningen had other interests as well. In addition to paintings, he collected drawings and shells, as was recounted by the Von UB enbach brothers after visiting his cabinet.:!

It would seem that Jan van Beuningen had brought a part of his cultural baggage with him from Italy. The German tourists, the Von UB enbach brothers, as well as the paint-er-biographer Arnold Houbraken indirectly refer to the fact that he once visited the country, perhaps as part of a Grand Tour or in his student years.:: We know that he travelled ex-tensively. For instance, in the years !6!7-!6!> he spent several weeks in Paris and Vienna. For business he sailed regularly on his private yacht to The Hague, Friesland or Middelburg. In short, he did not hesitate to leave Amsterdam every now and then, as is confi rmed in many of his letters.:7

This conduct presupposes an environment enabling such a life. And, a reconstruction of his acquaintances and rela-tives, indeed, attests to an extensive network of cultivated intellectuals. For instance, Van Beuningen’s previously men-tioned brother-in-law, Daniël Nijs, was the grandson and namesake of arguably the most famous gentleman-dealer of the seventeenth century. Nijs Senior negotiated one of the single largest art transactions during the Ancien Régime, namely the acquisition of the lion’s share of the cabinet of Vincenzo Gonzaga of Mantua for Charles . of England.:? Nijs came from a Southern-Netherlandish merchants’ fam-ily, but emigrated to the Doges’ city. He made a fortune and bought the island of Cavallino near Venice where he built a palazzo. In the course of his life he amassed a vast collec-tion of paintings and curiosities. His grandson, Daniël Nijs, grew up in the double canal house on the Keizersgracht (no. >66) his father, Isaac Jan, had designed by Philips Vingboons in !@@>. However, he sold the house and its contents – in-cluding the remains of the picture collection of Daniël Nijs Senior – after Isaac Jan’s death in !@=;.:> Daniël held sever-al less prestigious regencies and owned a manor in Muider-

?:

the poet Andries Pels with the aim of propagating French Classicism and which greatly infl uenced literary life in Am-sterdam around !6;;.?! The dedications to Van Beuningen in books and his own translations of French tragedies fi t perfectly within this cultural context. The fact that he also owned masterpieces by the painter Gérard de Lairesse only confi rms this.?: This painter-writer was an important fi gure in Nil Volentibus Arduum.

Several European monarchs and dignitaries also belonged to the select circle frequented by Jan van Beuningen. At the top of the list, naturally, was Landgrave Karl . von Hes-sen-Kassel and his daughter Maria Louise, for whom he or-ganised the auction. After all, Maria Louise had inherited the paintings from her husband Johan Willem Friso who, in turn, had inherited them from William .... Accordingly, it is worth describing briefl y the nature of the personal relation-ship between Jan van Beuningen and these noblemen. His correspondence with Maria Louise provides a great deal of information in this respect.?7 Jan van Beuningen travelled frequently to Soestdijk and Leeuwarden to personally in-form the princess about the business matters he was look-ing after on her behalf, including the auction. The trust she placed in him was expressed in the repeated permission she gave him to lodge in her domains for personal reasons. A prerogative he was only too eager to take advantage of. For instance, he was partial to the Kruitberg, an estate in Sant-poort that William ... had acquired as a country house. He once even oB ered to buy this hunting lodge, where he stayed on a regular basis.?? These visits did not escape notice, and were not always appreciated by the housekeeper, for after a stay in !6!7 she complained about the fact that Van Beu-ningen and his servant ‘had taken the bedclothes from the gallery in the countess’ room and slept in them; the table in the room [was] covered with fi lth and wetness, as if soldiers had lodged there.’?> Maria Louise was unfazed by this. For his services, she even gave Van Beuningen the freedom to lodge at will at Soestdijk Palace. Another privilege he gladly accepted, for example in !6!>. He sent her the following re-quest, asking whether he could eat there at his own expense ‘with three or four befriended couples.’?@

Conversely, Maria Louise lodged at least twice at Van Beu-ningen’s on the Keizersgracht (no. :@=) in Amsterdam.?6 In so far as we know, he fi rst put his house at the princess’ dis-posal in July !6!7, to which she responded that ‘we will accept with pleasure the obliging oB er you make us of your house, but only for our personal use.’?< The agent made the same oB er again just after the auction on July :@th !6!7: ‘I under-stand that Your Majesty is inclined to make a trip to Soestdijk via this city, I therefore should like to put this house and all

the most aD uent in all of Amsterdam. This is confi rmed in the tax assessment register.7: Andries Pels (!@>>-!67!), a namesake and cousin of the better-known poet, founded the fi rm in !6;6 which was disincorporated only in !66?. The company traded in luxury items, insurance and money. An-dries Pels was called the ‘banker of France’ and maintained close ties with James Brydges of Chandos. As mentioned ear-lier, Chandos was paymaster-general of the forces abroad for the British crown and in this capacity guaranteed the fi nanc-ing of the War of the Spanish Succession.77 Via Jan van Beu-ningen, Pels also fi nanced Landgrave Karl . von Hessen-Kas-sel.7? Andries Pels was a private commissioner in Amsterdam for the King of Sweden and was succeeded by Pieter Pels as resident of the same court.7> Andries Pels’ family, thus, was highly infl uential. The ties between Jan van Beuningen and Pels are disclosed in a number of archival documents. For example, as men-tioned, Van Beuningen regularly put in for large amounts at Pels’ fi rm and in !6!> rented a warehouse from it for ::,;;; guilders.7@ Later, in !6!<, Van Beuningen also gave Andries Pels power of attorney to collect outstanding debts on his behalf.76 This authorisation and the numerous transactions involving prodigious amounts, as appears from the archives of the Exchange Bank and the notarial archive of Amster-dam, at the very least evidence a relationship based on mu-tual trust. This would also be apparent at the auction of Wil-liam ...’s picture collection: the fi rm of Andries Pels and Sons bought fi ve paintings for a total of ?6<> guilders. Pels undoubtedly belonged to the group of friends that, accord-ing to Van Beuningen, ‘had emptied the purse so complete-ly for the auction’ that they could buy no more art for a full year.7< His relationship with Adriaen Bout, Jacques Meyers and other bidders at the auction is addressed below. Naturally, Jan van Beuningen’s personal and business network extended much further, both in Amsterdam and in other towns in the Republic. From the correspondence with Princess Maria Louise it emerges that he maintained con-tact with the Van Assendelft, Trip, d’Orville, Coymans, Van Schuylenburch and other families.7= However, it is diC cult to determine just how close these relationships were. For in-stance, after visiting Amsterdam the Von UB enbach broth-ers wrote that Jan van Beuningen was very familiar with all of the cabinets in Holland.?; This implies that he saw them on more than one occasion, and by extension that virtual-ly no one denied him entry to his or her collection. Inciden-tally, he too welcomed visitors to his cabinet, because after a chance meeting at a print dealer’s he invited the broth-ers to come to his home at their convenience. It would seem that Jan van Beuningen’s network partly overlapped that of Nil Volentibus Arduum, a literary society founded by

?7

no. 7><, Letter from Maria Louise to Jan van Beunin-gen, July #$#&.

!). ‘Ik versta dat Uwe Doorlugtige Hoogheijt gesint is, een rysie, oover deze stad, naar Soestdijk te nee-me, ik biede mijn huys en alles tot disposietie aen.’ The Hague, KHA, Archive of Maria Louise von Hessen-Kassel, inv. no. 7><, Letter from Jan van Beu-ningen to Maria Louise, # August #$#&.

"*. The Hague, KHA, Archive of Maria Louise von Hessen-Kassel, inv. no. 7>=, Letter from Jan van Beu-ningen to Maria Louise, #! August #$#&.

"#. ‘De jonge prins slaapt als een roos, gaat des mid-dags uijt rije, en heeft een toeloop van mensche die ongeloofl ik is. Men seegent hem de lante voix.’ The Hague, KHA, Archive of Maria Louise von Hessen-Kassel, inv. no. 7>=, Letter from Jan van Beu-ningen to Maria Louise, #! August #$#&.

"$. The Hague, KHA, Archive of Maria Louise von Hessen-Kassel, inv. no. 7>=, Letter from Jan van Beu-ningen to Maria Louise, #) November #$#&. See also Jonck heere :;;?, pp. <<-!:!.

"%. Van Beuningen n.d., p. !7:."!. The Prince of Hannover later became King

George . of England. The Hague, KHA, Archive of Maria Louise von Hessen-Kassel, inv. no. 7>=, Let-ter from Jan van Beuningen to Maria Louise, & Novem-ber #$#%.

"". See Chapter ?A."&. ‘I saw the notorious monarch dine eight days

before his death’ (Ik heb die berugte monarch agt daage voor zijn dude sien speijsen). The Hague, KHA, Archive of Maria Louise von Hessen-Kassel, inv. no. 7>=, Letter from Jan van Beuningen to Maria Louise, #' September #$#'.

!%. The Hague, KHA, Archive of Maria Louise von Hessen-Kassel, inv. nos. 7>< and 7>=, Letters from Jan van Beuningen to Maria Louise, #$#&-#$#'. Leeuwar-den, Tresoar (RAF), Stadholder’s Archive, Archive of Maria Louise von Hessen-Kassel, inv. no. !=, Let-ters from Jan van Beuningen to Maria Louise, #$#!.

!!. Kruitberg was once the country house of Hen-drik Reynst (father of the famous art lovers Ger-rit and Jan) and Balthasar Coymans. William ... bought the estate in !@<: for 7;,;;; guilders. After the death of the stadholder-king, the estate fell in-to disrepair, as mentioned by Jan van Beuningen. His bid was not accepted. Drossaers & Lunsingh Scheurleer !=6?-!=6@, vol. ., p. @76; Mobron & De Graaf !==6.

!". ‘Het beddegoet van de saal genomen en in de gravinne kamer gevondene en hebben daerop ge-slapen, de tafel op de saal vol vuyligheyt en nat-tigheyt, het is of daar soldaten gelogeert hadden.’ The Hague, KHA, Archive of Maria Louise von Hessen-Kassel, inv. no. 7>=, Letter from Jan van Beu-ningen to Maria Louise, !' March #$#&. The housekeep-er’s written complaint is in a separate fi le.

!&. The Hague, KHA, Archive of Maria Louise von Hessen-Kassel, inv. no. 7>=, Letter from Jan van Beu-ningen to Maria Louise, !# May #$#'.

!'. Keizersgracht :@=. The house he died in was on the Herengracht near the Koningsplein. Amster-dam, GAA, NAA, inv. no. >;6> no. <>>6 deed !@, Es-tate inventory of Jan van Beuningen, $ February #$!#.

!(. ‘De obligante aanbiedinge die u ons van syn huijs doet, sullen wij met plaisir edoch maar voor onse persoon alleen aannemen.’ The Hague, KHA, Archive of Maria Louise von Hessen-Kassel, inv.

was Anton Ulrich who had recommended him as ‘old nobil-ity’ (oude adel) in Vienna.>7 Other good friends included the ruling Elector of Hannover, and Friedrich Anton Ulrich von Waldeck, who dined at the Amsterdam merchant’s home.>? James Brydges of Chandos visited him in !6;>.>> He even saw the French Sun King, Louis E.A, with his own eyes at a ban-quet in Versailles.>@ As a nobleman, Van Beuningen had ac-cess to the palace.

These bonds of friendship with the highest of European no-bility undoubtedly were related to the services he rendered and the position of trust he enjoyed. In the case of the Land-grave von Hessen-Kassel and his daughter Maria Louise, Jan van Beuningen’s banking activities certainly played in his favour. Soliciting so much money in a time of war was enor-mously risky. Equally important here was his knowledge as a connoisseur and art buyer.

that it oB ers at your disposal.’?= Again, the countess accept-ed the invitation and stayed with her two children and her chargé d’aB aire in Amsterdam for a few days between < and !: August of that year.>; It was a turbulent visit, for Prince William, her son and heir to the throne, became feverish af-ter a hunt and was required to stay in bed. ‘The young prince sleeps like a rose, goes riding in the afternoons, and receives an unbelievable surge of people. They bless him with a slow and soft voice,’ Van Beuningen wrote.>! The royal audiences in no way detracted from the wealthy merchant’s prestige. Maria Louise, incidentally, was not the only distinguished guest at his table. He maintained equally close contacts with Duke Anton Ulrich von Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel. In fact, he called him a friend. This friendship was reward-ed when the monarch agreed to be the godfather of Anto-nia Ulrica, Jan van Beuningen’s youngest daughter.>: Van Beuningen also owed him the ‘renovatio nobilitatis,’ for it

%$. Elias !=@7, vol. .., p. <!7.%%. San Marino, HL, Brydges Papers, inv. no.

ST >6->< (6! vols.), Correspondence of James Brydges of Chandos, #(*%-#$%%. See also Chapter ?A.

%!. Amsterdam, GAA, NAA, inv. no. >;6> no. ?::> deed !;?, !!; et al., Debenture of Jan van Beuningen on commission of Baron van Dalwig, plenipotentiary for Landgrave Karl von Hessen-Kassel to Andries Pels and Sons, #$ and #) January #$#&.

%". Schutte !=<7, pp. 7!=-7:;. His parents were Pau-wels Pels and Antoinette von Sandrart of Frank-furt. She was probably a cousin of the famous painter-writer Joachim von Sandrart.

%&. Amsterdam, GAA, NAA, inv. no. >;6> no. ?:7: deed :7, Obligation of Jan van Beuningen to Andries Pels and Sons for the lease on a warehouse, & July #$#'. Van Eeghen !=6;b, pp. :!6-::?.

%'. Amsterdam, GAA, NAA, inv. no. >;6> no. 6=6= deed >, Procuration of Jan van Beuningen to Andries Pels, ! August #$#).

%(. ‘voor de vercooping de buijdell so leedig hadden geclopt.’ See Chapter >.

%). The Hague, KHA, Archive of Maria Louise von Hessen-Kassel, inv. nos. 7>< and 7>=, Letters from Jan van Beuningen to Maria Louise, #$#&-#$#'. Leeuwar-den, Tresoar (RAF), Stadholder’s Archive, Archive of Maria Louise von Hessen-Kassel, inv. no. !=, Let-ters from Jan van Beuningen to Maria Louise, #$#!.

!*. Von UB enbach !6>?, vol. ..., p. 7?!.!#. This Andries Pels was an uncle of the Andries

Pels who founded the fi rm of Andries Pels and Sons. De Vries !==<; Emmens !=@<, p. 67 B .; Elias !=@7, vol. .., pp. <!:-<!?.

!$. See Appendix B:.

??

tleman-dealer. Collecting and dealing in works of art went hand in hand. He did not attempt to amass a complete col-lection, but rather tried to sell oB masterpieces to befriend-ed rulers or fellow collectors – as long as this enhanced the reputation of his own cabinet. It is not clear whether he al-so intended to make a profi t in this way. There is equally lit-tle doubt that dealing was an essential aspect of his collect-ing aC nity. For instance, in the aftermath of the auction of the paintings from the inheritance of William ..., on > May !6!? he wrote the following to Maria Louise: ‘I took no eB ort to answer your question regarding what to do with the left-over works of art, they must await buyers this year. I expect them daily. Their number is too small to warrant organising another auction, and [I] also know that last year the friends emptied their purses to such an extent that they have noth-ing left. Allow me, at my discretion, to arrange for the rest. I will not sleep, and listen about. Since the sale not a single work in my cabinet has been sold.’>= Selling was simply part and parcel of his enthusiasm for art. This immediately brings us to the third aspect of Jan van Beuningen as a gentleman-dealer. He organised at least two auctions in the beginning of the eighteenth century. In !6!7 he set up, as is now clear, the public sale in the Oudezijds Herenlogement in Amsterdam of the paintings the stad-holder-king had collected for Het Loo. He also auctioned much of his own picture collection in Amsterdam in !6!@ be-fore leaving for Curaçao.@; The two auctions were exception-al compared to other sales in this time (Graph !). Both the proceeds and the average prices were far higher than nor-mal. At the Het Loo sale an average of <<: guilders (median :<< guilders) per lot was paid and at Van Beuningen’s :<@ guilders (median !?> guilders). In the period !@<;-!6?; on average a lot cost !!@ guilders (median ?! guilders).@! When this is incorporated in a graph breaking down the number of lots by price, it becomes clear just how exclusive the two sales were.@: Jan van Beuningen’s own painting collection, thus, had quite a reputation of its own. When a portrait by Anthony van Dyck was auctioned more than >; years later, the fact that it had once been in his cabinet was mentioned as extra recommendation.@7

As announced in the Amsterdamsche Courant, a second auction was organised after Van Beuningen’s death;@? unfortunate-ly, no catalogue of this event has been preserved. However, judging from Jan van Beuningen’s estate inventory drawn up by Notary Commelin on 6 February !6:!, it probably con-sisted largely of works that had been bought in at the previ-ous sale.@>

,+$ '&, 2#A$&, ,+$ ($'2$& – In a letter from !6!; to the Ghent gentleman-dealer Francisco-Jacomo van den Berghe, the Amsterdam art lover Isaak Rooleeuw typifi ed his friend Jan van Beuningen as follows: ‘Because what one fi nds here in private hands is not exceptional; or what is good is not for sale, unless by chance, in time. However, in the case of Mr Van Beuningen, presently the greatest art lover of the city – because it pleases him to amuse his eyes with change – good friends can always obtain something beautiful.’>6 Rooleeuw was not the only one to extol Van Beuningen. Words of praise are also found in the notes made by the Von UB en-bach brothers, who visited his cabinet in the spring of !6!;: ‘On Thursday :: May, we encountered Mister Van Beunin-gen on the Singel, close to the Reguliersgracht in the house of the Alderman Reaal. He had met us in the shop of Nico-laes Vischer, were my brother was buying prints and had in-vited us, as an amateur of drawings to his [house], to show us his paintings, of which he was a great amateur and con-noisseur. We saw there, in three large rooms and a small cab-inet, a wonderful stock of some !>; pictures by the most fa-mous painters. We scrutinised them, the one after the other, and especially appreciated the paintings in which Rubens had painted the fi gures and Brueghel the landscapes. The pictures all had the most expensive carved and gilded frames.’><

Several aspects of Jan van Beuningen’s life make him unique in an art-historical respect. In the fi rst place, he had a collection of paintings that was exceptional by the stan-dards of the time in the Republic. Second, he is a prime ex-ample of what art historians would later come to call the gen-

?>

&*. See Appendix B:. Catalogue of the painting col-lection of Jan van Beuningen.

&#. See Appendix A;.&$. For the explanation of this graph, see Appen-

dix A!.&%. Lugt =>:, lot no. !:. ‘A Spanish portrait, three-

quarter length with a hand, life-size, being a no-bleman by A. van Dyck, this comes well honour of Mr Van Beuningen, and subsequently of De Wit, high ?! thumbs, wide 7: thumbs’ (Een Spaans Por-tret Kniestuk met een Hand, levensgroote, zynde een Edelman, van A. van Dyck, dit komt wel eer van de Heer van Beuningen, en naderhand van De Wit, hoog ?! duim, breed 7: duim). It must have been sold before the auction of !6!@.

&!. Dudok van Heel !=6@, pp. !;6-!::.&". The catalogue is known only thanks to its inclu-

sion in Hoet !6>:, vol. ., pp. !==-:;?. For the estate inventory, see Amsterdam, GAA, NAA, inv. no. >;6> no. <>>6 deed !@, Estate inventory of Jan van Beu-ningen, $ February #$!#. See also Appendix B:.

Meistern. Wir sagen sie nach einander etliche mal mit vergnügen an, musten aber insonderheit etli-che Stücke bewundern da Rubens die Bilder, Bru-gel aber die Landschaften [...] dazu gemalet. Die Gemälde waren sonst alle in den kostbahrsten ge-schnizten und vergüldeten Rahmen [...].’ Von Uf-fenbach !6>?, vol. .., p. ?!<.

"). ‘Ik had niet eenig werk om uw vraage wat met de oovergebleevene cunststukke te doen, is te be-antwoorde, die moete dit jaar coopers uijt de hand aB wagte, welke daageliks te gemoet sie, om een vercooping aente legge, is het hoopie te cleijn, en ook weet dat de vrinde voorleede jaar, de buijdell [...] so leedig is geclopt datter niet ooverig is, laat mij met believe de verdere bewerking bevoole. Ik sall niet dutte, als maar its hoore, mij cabinet heeft seedert de vercooping, geen stuk gelost [...].’ The Hague, KHA, Archive of Maria Louise von Hessen-Kassel, inv. no. 7>=, Letter from Jan van Beuningen to Maria Louise, ' May #$#%.

"'. ‘Want ’t geen hier by particulieren is, is niet son-derlings; of daar wat goeds is, is niet te koop ten-zij bij geval waar omtrent de tijd en goede occa-sie moet worden waargenomen. Dog by heer van Beuningen, tegenwoordig de grootste liefhebber van de stad, omdat het hem behaagt zyn oog door verandering te vermaken, is voor goede vrien-den wel wat fraaijs te bekomen.’ Duverger :;;?, pp. 6>-6@.

"(. ‘Den :: may Donnerstags Morgens befanden wir den hern von Boeningen op den Lingel [Sin-gel] by de Reguliers toren in het huys van de Heer Scheepe Royal [Reaal]. Er hatte uns in [Nicolaes] Vischers Laden, als mein Bruder kupfer[-stiche] kaufte, angetroB en, und uns als ein Liebhaber von der Zeichnung zu sich gebeten, um seine Gemäl-de, davon er ein grosser Liebhaber und kenner war zu sehen. Wir fanden bey ihm in drey grossen Zimmern und einem kleinen kabinet einen vor-treD ichen Vorrath etwa von hundert und fünf-zig der schönsten Stücke, von den berühmesten

$% Hans Rottenhammer and Velvet Brueghel, The fall of Phaeton, copper, 7= x >?.> cm, The Hague, Royal Cabinet of Paintings Mauritshuis, inv. no. :<? (B:, lot no. >?)

?@

huis in The Hague, but once hung on the walls of Van Beu-ningen’s home.@< The history of Dou’s panel is one of a kind. It was part of the famous !@@; Dutch Gift which the States of Holland and West-Friesland presented to Charles .. of Eng-land. William ... brought it back to the Republic and dis-played it at Het Loo.@= When Jan van Beuningen went there in December !6!: to appraise the paintings to be sold at auc-tion he was instantly drawn to it. He shared this with Maria Louise and noted that he had taken it ‘in his valise’ (in ’t va-lies). Because it required special care he had refrained from shipping it with the other pieces destined for sale.6; The Dou, however, was never oB ered at auction because England was demanding its return along with a part of William ...’s property.6! This claim eventually expired and Van Beunin-gen tried to sell it as his own property at the auction of !6!@.

+.4 #1% *#22$*,.#% – What did Jan van Beuningen’s own collection comprise? Thanks to Gerard Hoet’s !6>: pub-lication of sales catalogues we know what paintings were in Van Beuningen’s cabinet in !6!@.@@ They were largely by Ital-ian and Southern-Netherlandish masters. No less than 7; of the <@ works (7?%) had an Italian attribution. And :! paint-ings (:?%) were given to Southern-Netherlandish masters. Twenty-fi ve works (:=%) were ascribed to painters from the Republic. The remaining works were of French and German origin. The auction fetched :?,@>6 guilders and the collec-tion was an anthology of what was then – and in many cas-es still is – considered to be the very best. Accordingly, the prices paid for the various paintings refl ect their outstand-ing quality. He owned works by close to the entire top 7;% of the most expensive painters in this period.@6 He had three paintings ascribed to the Carracci brothers, as well as two each attributed to Raphael, Jacopo Bassano and Gentileschi and fi nally works by Titian, Tintoretto, Perugino, Parmigia-no, Giordano, Caravaggio and others. In their midst were al-so works by Rubens and Van Dyck, Rembrandt, Dou and Van den Eeckhout, Rottenhammer, Bril and Brueghel. Many of them still grace great collections today. What follows is a survey of these works. Three paintings, The fall of Phaeton (fi g. :7) by Hans Rot-tenhammer and Velvet Brueghel, the Nymphs fi lling the horn of plenty (fi g. :?), by the latter and a pupil of Rubens and The young mother by Gerard Dou (fi g. :>) are now in the Maurits-

&&. Hoet !6>:, vol. ., pp. !==-:;?.&'. See Appendix A:.&(. See Appendix B:, lot nos. >?, 76 and ><. The

Hague !==7b, pp. 6=-<!.&). Slot !=<<, pp. ?@->6.'*. The Hague, KHA, Archive of Maria Louise von

Hessen-Kassel, inv. no. 7>=, Letter from Jan van Beu-ningen to Maria Louise, ## April #$#&. The Hague, KHA, Archive of Maria Louise von Hessen-Kassel, inv. no. 7>=, Letter from Jan van Beuningen to Maria Louise, #! August #$#&.

'#. The Hague !=<<, pp. 6=-<;.

$! Jan Brueghel the Elder and a pupil of Rubens, Nymphs fi lling the horn of plenty, panel, @6.> x !;6 cm, The Hague, Royal Cabinet of Paintings Mauritshuis, inv. no. :7? (B:, lot no. 76)

?6

$" Gerard Dou, The young mother, !@><, panel, 67.> x >>.> cm, The Hague, Royal Cabinet of Paintings Mauritshuis, inv. no. 7:

?<

This attempt failed and the painting was bought in at !7!; guilders.6: It subsequently re-entered the stadholder’s col-lections, along with some other paintings that Van Beunin-gen kept at home after the Het Loo sale.67

That Van Beuningen was very familiar with Dou’s work is evidenced several times in the sales catalogue of !6!@. The well-known Grocer’s shop that then went under the hammer might be the one today found in the Louvre.6? Previously, he had sold three Gerard Dous to James Brydges, including the Young violinist (fi g. =?), the Girl at a virginal (fi g. =7) and the Woman with a basket of fruit (fi g. =>).6>

In the course of time Jan van Beuningen had managed to amass a collection with a number of veritable masterpieces. Already famous in his own day was a series of scenes from the Old Testament attributed to Luca Giordano.6@ Accord-ing to Arnold Houbraken, the series was a sample of the art-ist’s mastery and Van Beuningen had personally assured him that Giordano had produced each one in two days.66

'$. Jan van Beuningen received the painting at his home on !: August separately from the other bought in paintings, which he would later resell. He aC rms his penchant for the painting in a letter to Maria Louise. Houbraken did not know what had become of the pictures: ‘In the same is depict-ed a woman with a child on her lap, and a girl play-ing with it. King William subsequently had this work shipped from England and placed in Het Loo, but where it now is I do not know’ (In het-zelves stont verbeelt een Vroutje met haar Kintje op den schoot, en een meisje dat met het zelve speelt. Dit stukje is naderhant door Koning Wil-lem uit Engelant vervoert en op ’t Loo geplaatst, maar waar het thans is weet ik niet). Houbraken !6!<-!6:!, vol. .., pp. >. The Hague, KHA, Archive of Maria Louise von Hessen-Kassel, inv. no. 7>=, Letter from Jan van Beuningen to Maria Louise, #! Au-gust #$#&.

'%. See Chapter @.'!. See Appendix B:, lot no. >=.'". Collins Baker & Baker !=?=, p. 67; Amsterdam

!=<=, p. 7:. For the reasoning, see also Chapter ?A. Appendix B:, A:-A7 and A?.

'&. See Appendix B:, lot nos. !6-:> and A@-A6.''. Houbraken !6!<-!6:!, vol. .., p. :=. See Appendix

B:, lot no. :>.'(. Jonckheere :;;?, p. !;6.'). Houbraken !6!<-!6:!, vol. ., p. :@=. For the time

being it is impossible to determine which portrait it was. It had been resold before !6!@.

(*. Van Gelder !=6?, p. !6>. Cambridge !=<:, pp. !;=-!!;. See also Appendix B:, lot no. 7=.

(#. The Rembrandt Research Project now calls this a workshop painting. This hypothesis is not gen-erally accepted. Among others, the Hermitage still considers it to be a Rembrandt. Bruyn et al. !=<:-!=<=, vol. 7, pp. >77->?!. See also Appendix B:, lot no. ?;.

($. Sumowski !=<7, vol. :, p. 6?7. See also Appendix B:, lot no. >!->:.

(%. Wieseman :;;:, cat. no. 6;, :!=. This amount is extravagant in comparison to other works by this master in this period. See Appendix A: and Ap-pendix B:, lot no. >7.

(!. Wieseman :;;:, cat. no. ?=, :;;-:;!. See Appen-dix B:, lot no. >;.

(". The Hague, KHA, Archive of Maria Louise von Hessen-Kassel, inv. no. 7>=, Letter from Jan van Beu-ningen to Maria Louise, & November #$#%.

(&. Moes !=!7, pp. ?-:?; Korthals Altes :;;7a, p. !?= B . This painting is presently unknown.

('. See Appendix B:, lot no. 7?.

$& Rembrandt (?), Adoration of the Magi, panel, !::.@ x !;? cm, London, Collection of Her Majesty the Queen (B:, lot no. 7=)

?=

and Paul and Barnabas before the high priest.<: For a Masquerade by Caspar Netscher (fi g. :6) no less than =<; guilders were paid.<7 For the Girl singing and a lute player on a balcony (fi g. :<) 7;; guilders were counted out.<? Not surprisingly, the latter two works eventually found their way into German princely collections in the mid-eighteenth century. The Masquerade, which now hangs in Kassel, undoubtedly evoked memories for Wilhelm A... von Hessen-Kassel, as he had been a guest in Jan van Beuningen’s home in !6!?.<> The prince will have jumped at the chance to buy the painting when it was of-fered to him. Another picture that wound up in Kassel was a genre scene of a mother at a cradle by Pieter van Slingeland. The art lover Valerius Röver bought it for @:; guilders at the auction of !6!@. In turn, Wilhelm A... bought the Röver col-lection, including this scene, en bloc.<@ At Van Beuningen’s he undoubtedly also saw another painting acquired for the gallery in Kassel during his reign, the ‘Meleager and Atalan-ta [...] gracefully [painted] by P. Paul Rubens’ (Meleager en At-talante [...] gracelyk door P. Paul Rubbens).<6 There are sev-

Two canvasses were also sold to Duke Anton Ulrich before !@=6 (fi gs. !7? and !7>).6< Nine remaining paintings from the series were sold at the sale to Sibrand van der Schelling for a total of :@=; guilders. Also according to Houbraken, Jan van Beuningen had once owned a famous self-portrait of Rem-brandt.6= The likeness was not in the auction and therefore must have been sold prior to it. Another Rembrandt, the Adoration of the Magi (fi g. :@), fetched a tidy !>;; guilders – an astonishing amount for a painting by the master at that time.<; On average, a painting then attributed to Rembrandt cost only !?; guilders (median ?6), whereby his work was not at the absolute top end of the market. Another picture by the master, David’s farewell to Jonathan (fi g. 7;), went for a mere <; guilders to Osip Solovyov, the agent of Tsar Peter the Great, who immediately shipped it oB to St Petersburg.<! I will re-turn to this later. The Amsterdam art lover also owned work by less obvious Northern-Netherlandish artists, for example two paintings by Gerbrand van den Eeckhout, namely Christ in the Temple

$' Caspar Netscher, Masquerade, !@@<, panel, ?6 x @7.> cm, Kassel, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, inv. no. GK :=: (B:, lot no. >7)

>;

masters cannot be recovered. He seems to have had ‘a life-size angel’ (engel, levens groote) by Caravaggio at home. An exception is the Landscape with the road to Emmaus, described in the catalogue as ‘the travellers on the road to Emmaus, three fi gures in a landscape’ (de Emausgangers, 7 Beeldjes in een Land schap), which may have been auctioned as a work by Jan Brueghel the Elder and Rubens in !=@>.=7

,&'($ – This can only have been a fraction of what Van Beu-ningen once owned. Von UB enbach noted that in !6!; Van Beuningen still had !>; works in two large rooms and a cab-inet.=? Yet the sales catalogue lists only <@ lots. The estate in-ventory mentioned a few bought in works from the auction. And, in the decades before the auction of !6!@ he, indeed, re-peatedly sold superb pictures for high amounts to other col-lectors, mostly monarchs. Jan van Beuningen’s ‘clientele’ – he called them friends – cannot be fully reconstructed, but as emerges in the course of this study it largely coincided with the buyers present at the Het Loo auction. In addition, what is known about his art dealing activities sheds some light on the type of people to whom he resold art. In fact, it confi rms his status as a purveyor to royal households. Just look at the

eral versions of this scene and various European noblemen displayed an interest in it at the beginning of the eighteenth century. The Duke of Marlborough, whom Van Beunin-gen must have known through his agent John Drummond, owned a version (now in The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York).<< That a painting of The drought during Phaeton’s journey by Hans Rottenhammer (fi g. :=) also found its way to Kassel illustrates once again just how familiar William A... was with Van Beuningen’s collection.<=

Works by presently less famous, but at the time highly valued masters, such as Gérard de Lairesse, were also found in Jan van Beuningen’s cabinet. One of these was ‘Antiochus and Stratonice, !@ fi gures in the courtyard, entirely of his best kind [...]’ and at !:;; guilders it was one of the most ex-pensive works in the auction.=; He also had two scenes by Adriaen van der WerB , a Susanna and the elders and an Ecce Ho-mo.=! Finally, he owned a genre scene with a lewd old man by Frans . van Mieris (!@7>-!@<!).=: Other paintings are more dif-fi cult to trace. Sometimes there are several related versions, and sometimes the descriptions are not precise enough. This applies, for instance, to portraits by Titian, Tintoret-to and Rembrandt. Most of the pictures ascribed to Italian

((. John Churchill, Duke of Marlborough, had a version in Blenheim. In Kassel is a version (good workshop copy) that was acquired by Wilhelm A... von Hessen-Kassel. Woodstock !<@:, p. :?; New York !=<?, pp. !@?-!@<. See Appendix B:, lot no. ?=.

(). See also The Hague !==7b, pp. :=!-:=7.)*. ‘Antiochus en Stratonice, !@ fi guurtjes en in ’t

Binne Paleys heelyk van zyn beste zoort [...].’ Am-sterdam !=<=, pp. :6<-:6=. A smaller, earlier ver-sion is now in Schwerin: Gérard de Lairesse, Stratonice and Antiochus, !@67, oil on panel, 7!.> x ?@.> cm, Schwerin, Staatliches Museum. See Ap-pendix B:, lot no. ??.

)#. The Ecce Homo is a small copy of the painting commissioned by the Count Palatine, Johann Wil-helm, now in Munich (Munich, Alte Pinakothek, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, inv. no. :::). The version in the Van Beuningen collection is now in Moscow. The painting was bought by Solovyov for Tsar Peter the Great. See Gaehtgens !=<6, pp. :=>-:=6. See Appendix B:, lot no. ?>. Gaehtgens makes no mention of a painting by Van der WerB depicting a Susanna and the elders.

)$. Only a single copy of this painting has been pre-served. The original is lost. See Appendix B:, lot no. @?. Naumann !=<!, p. !;=.

)%. London, Sotheby, < December !=@>, no. >. See Ertz !=6=, p. ?=7. Van Beuningen bought the painting from the Flemish gentleman-dealer Jan van der Block. Duverger :;;?, p. <>. See also Ap-pendix B:, lot no. 7<.

)!. Von UB enbach !6>?, vol. .., p. ?!<.

$( Caspar Netscher, Girl singing and a lute player on a balcony, !@@>, panel, ?7.> x 7? cm, Dresden, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, inv. no. !7?6 (B:, lot no. >;)

>!

)". The Hague, KHA, Archive of Maria Louise von Hessen-Kassel, inv. no. 7><, Letter from Jan van Beu-ningen to Maria Louise, % February #$#&.

)&. See Chapter ?A. Collins Baker & Baker !=?=; Johnson !=<?; Jenkins :;;!.

)'. Collins Baker & Baker !=?=, pp. @=-6=. See Ap-pendix B:, A:-A7 and A?.

)(. Amsterdam !=<=, p. 7:. Pieter Spiering Sil-vercrona was the agent of Christina of Sweden. Joachim von Sandrart described the painting.

James Brydges, who would also send an agent to the Het Loo auction, was a fabulously wealthy English nobleman. A con-fi dant of the British crown, he was above all a generous pa-tron of the arts.=@ His contemporaries aptly nicknamed him Princely Chandos. He began collecting at a young age, and later surrounded himself with artists and musicians, in-cluding Georg Friedrich Händel, who spent two years at his estate Cannons, where Brydges kept a large part of his art collection. After the death of the Duke of Chandos, the pal-ace was dismantled and sold piece by piece on account of the great value of the building materials; no one seems to have been in a position to buy it lock, stock and barrel. This daz-zling wealth characterises the collector’s possibilities and passion. Jan van Beuningen had maintained contact with Chandos and his agent in the Republic, John Drummond, since !6;>.=6 They occasionally dealt in paintings, such as Gerard Dou’s Young violinist (fi g. =?) from the collection of the aforementioned Pieter Spiering Silvercrona, the Girl at a virginal (fi g. =7) and the Woman with a basket of fruit (fi g. =>).=<

Osip Solovyov, agent and buyer for Tsar Peter the Great in Holland, was also a member of this select group of indi-viduals who acquired paintings from the collection of Jan

following list: Tsar Peter the Great, Anton Ulrich von Braun-schweig, Eugen Frans von Savoyen-Carignan, James Brydg-es of Chandos, Lothar Franz von Schönborn, and so forth. He also maintained friendships with other prominent sov-ereigns, such as Karl . von Hessen-Kassel and Georg Ludwig, Elector of Hannover: clearly, he was not just any old art deal-er, but rather a trusted agent – albeit unoC cial – to members of the highest European aristocratic and noble circles. He re-ceived them at home and regaled them with a tour of his fa-mous cabinet. He was not lying when he said ‘I fully extend my services,’ as he once wrote his patroness.=>

$) Hans Rottenhammer, The drought during Phaeton’s journey, !@;?, copper, 7= x >; cm, Kassel, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, inv. no. @;? (B:, lot no. ?=)

>:

%* Rembrandt (workshop?), David’s farewell to Jonathan, panel, 67 x @!.> cm, St Petersburg, Hermitage, inv. no. 6!7 (B:, lot no. ?;)

>7

Louise von Hessen-Kassel, inv. no. 7>=, Letter from Jan van Beuningen to Maria Louise, ( May #$#&.

#*(. Lugt :7=.#*). See Appendix B:, lot no. ??.##*. See Appendix B:, lot no. >>.###. For the Laurens van der Hem auction (Lugt :7<),

see Hoet !6>:, vol. ., p. !?< (lot no. !7). See Appen-dix B:, lot no. ?;.

##$. Hoet !6>:, vol. ., pp. !>=-!6!. See Appendix B:, lot no. >:.

##%. Hoet !6>:, vol. ., pp. !6:-!67. Hoet calls the man Gerard van Sypes. However, it is really Everard van Sypesteyn. Van Kretschmar !=@=, pp. !!?-!6?. See Appendix B:, lot no. @;.

##!. Hoet !6>:, vol. ., pp. !<?-!<>. See Appendix B:, lot no. :@.

#*%. Hoet !6>:, vol. ., pp. <;-<>. See Appendix B:, lot no. @:.

#*!. See Chapter ?D. This is an abridged and re-worked version of Jonckheere :;;?.

#*". The Hague, KHA, inv. no. 7>=, Archive of Maria Louise von Hessen-Kassel, Letter from Jan van Beu-ningen to Maria Louise, #) November #$#&.

#*&. ‘Dierbare vrouwe [Maria Louise von Hessen-Kassel] en haar geseegent kroost, historischerwijse verbeelt.’ The project was probably not realised, for Anton Ulrich passed away a few months later.

#*'. ‘De vercooping tot Rotterdam, van den heere Paats hebbe bijgewoont, ’t was een lust des her-te, de animeusheijt, van de liefhebbers te sien en-te hoore hoe dat ze ƒ :[;;;]: 7[;;;]: ?;;;: voor plankies van !: :: voet besteede, ik hebbe mij por-tie meede van.’ The Hague, KHA, Archive of Maria

before !@=6 and still grace the Herzog Anton Ulrich-Mu-seum (fi gs. !7? and !7>). As mentioned above, Duke Anton Ulrich and Jan van Beuningen had very close personal ties. Jan’s younger daughter was called Antonia Ulrica, and the duke was her godfather.!;> Almost casually, he even mediat-ed the commission for a portrait of the ‘The well-loved wife [Maria Louise von Hessen-Kassel] and her blessed oB spring as a portrait historié,’ at the request of Anton Ulrich.!;@

Where Jan van Beuningen himself bought paintings is not entirely clear. In any case he bid at auctions, as he himself confi rmed in one of his letters to Maria Louise: ‘I attended the sale of Mr Paets in Rotterdam. It was entertaining to see the animosity of the art lovers and hear that they spent :;;;, 7;;;, ?;;; guilders for little panels measuring ! to : feet. I also bought a portion.’!;6 And, this portion was substan-tial.!;< Lot number :>, the most expensive painting on which he bid, was the aforementioned history scene by Gérard de Lairesse depicting the story of Antiochus and Stratonice.!;= He paid !>>; guilders for it. He acquired another classical scene, Aeneas leaving from Troy by ‘Bartholet’ (Bertholet Flémal), for 6;; guilders.!!; And, he most likely bought many more paintings. Jan van Beuningen attended other high-profi le auctions as well. At the Van der Hem sale, also in !6!7, he bought Rembrandt’s David’s farewell to Jonathan.!!! That same year he bid at the Cornelis van Dijk sale, paying <? guilders for the above-mentioned work by Gerbrand van den Eeck-hout, Paul and Barnabas before the high priest.!!: A year later he paid 7;> guilders for a Susanna and the elders by Adriaen van der WerB at the sale of the Everard van Sypesteyn collection in Utrecht.!!7 One year later, on < May !6!>, at a small auction in Amsterdam he bought a Holy Family attributed to Sebas-tiano del Piombo.!!? It cost him 7>; guilders. A few days later

van Beuningen. From !6;6 to !6!6 he was the tsar’s commis-sioner in Amsterdam, where he was also active as a dealer. He rented a house on the Herengracht, number >:6. Solovy-ov was no stranger to the Van Beuningens, for Daniël Nijs, Jan’s brother-in-law, let him a warehouse on the Ossemarkt for some time.== We know of two transactions between So-lovyov and Van Beuningen.!;; At the auction of Jan van Be-uningen’s collection in !6!@, the tsar’s agent bought no less than fourteen pieces which shortly thereafter were shipped to Russia to grace Peter the Great’s cabinets, including Rem-brandt’s David’s farewell to Jonathan (fi g. 7;).!;! However, the two had earlier dealt in art. At least, this is what the court painters Georg Gsell and Jacob Stahlin reported in their de-scription of the collections of paintings in Marly and Mon-plaisir in St Petersburg: ‘Abraham and Melchisedech, origi-nal by Pie tro Cordono [da Cortona]. This present piece was previously part of the painting collection of Frantz d’Orville [Jan François d’Orville], a famous connoisseur and art lover from Amsterdam. From him, it was acquired by H. van Bön-ing [Jan van Beuningen], director of the East-India Company and from him it was bought by Soloviow [Solovyov].’!;: The painting was not included in the sale of d’Orville’s collec-tion, which means that Van Beuningen had already bought it. Yet in !6;> he also bid at the d’Orville auction. He almost certainly acquired the above-mentioned ‘Baptism of John in the Jordan River, the landscape by Bril and the fi gures by Rottenhammer’ (De doop van Johannes in de Jordaene, het land schap van Bril en de beelden van Rottenhammer) there.!;7

Other individuals, such as the great patron Anton Ulrich von Braunschweig, also bought art from Van Beuningen.!;? Two paintings from the series of scenes from the Old Tes-tament attributed to Luca Giordano already changed hands

)). Amsterdam, GAA, NAA, inv. >;6> no. @@7!, Lease on a warehouse owned by Daniël Nijs to Osip Solovyov, the Tsar’s commissioner, #! July #$#$.

#**. Van der Veen !==@, pp. !7:-!7=.#*#. See Appendix B:, lot no. ?;.#*$. ‘Abraham und Melchisedes [...], original von

Pietro Cordono [...] Dieses gegenwärtige Stücke hat sonst Frantz d’Orville, ein berühmter Kunst-verstandiger und Liebhaber, ein Kaufmann zu Amsterdam unter seinen Schilderijen besassen. Von dem selben kam es an, bewindhabber der Ost Ind. Compagnie und von diesen kaufte es Soloviow.’ Cf. description of the cabinets by Gsell and Stählin. With thanks to Mrs Jozien Driessen for a copy of her transcription of the estate inven-tory.

>?

Unlike Jan van Beuningen, a wealthy and prominent mer-chant who sold art almost as a pastime, Jan Pietersz. Zomer (fi g. 7!) worked full-time as an art broker, as he was wont to call himself.!:> To this day, he is profi led in numerous pub-lications as the premier art dealer at the end of the Golden Age. This reputation warrants some fi ne tuning and revi-sion.!:@

When, in !6!:, the decision was taken to auction the paint-ings from the Het Loo Palace, Zomer was already a well-known appraiser. Although certainly not a neophyte, Van Beuningen simply did not have the same amount of experi-ence. The two had known each other for years, which is en-tirely understandable under the circumstances. Amsterdam collectors and dealers depended on one another for informa-tion about ‘old masters’. Zomer and Van Beuningen had al-

ready met in !6;7 at the appraisal of some paintings owned by Otto Roger Costart of Paris, after an ordinance Van Beu-ningen had obtained from the Amsterdam Aldermen’s Bench. The expertise of the painters ‘Backhuizen, Van der Plas, Huchtenburgh, and Van Overbeek, as well as that of the broker Jan Pietersz. Zomer’ (Bakhuijsen, van der Plas, Hugtenburg, ende Overbeke, mitsgaders de Makelaar Jan Pietersz. Zomer) was invoked to confi rm Jan van Beunin-gen’s previous judgment of the paintings.!:6 Costart’s depu-ty, however, instructed the notary to record that he deemed this inspection to be ‘null, and of no value whatsoever.’ Presumably, Van Beuningen was responsible for involv-ing Zomer as an external appraiser in the project to auction oB William ...’s picture gallery. However, he seems to have had some reservations regarding the collaboration. A few

abroad, and the dissipation of the total credit of the bourse, are the reasons why I fi nd myself in such straitened circum-stances [...] I saved myself through pawning,’ he wrote in the summer of !6!>.!:! He continued to be plagued primarily by the unpaid bills of exchange. Nevertheless, the damage was less than expected, for he seems to have been able to travel to Paris and ‘the two empires’ (Austria-Hungarian Empire?) without any appreciable impediments.!::

To recapitulate, despite the fact that until now nothing about him was known, Jan van Beuningen can by typed as a prominent art lover. However, this did not mean that he had any diC culty reselling a painting when a notable prince or connoisseur proved willing to pay a high price for it. What-ever the case may be, the dividing line between art lovers and dealers was blurred in the seventeenth and eighteenth century.!:7 Apparently, collecting and dealing constituted a dyad. Jan van Beuningen allied himself with this tradition. His ‘clientele’ was probably more diverse than can be deter-mined today. The lack of archival material, though, makes it particularly diC cult to recover the private transactions with friends and colleague-collectors. James Brydges, Anton Ulrich and many other ‘friends’ dispatched agents to the Het Loo auction. This had every-thing to do with the person of Jan van Beuningen. He laid the contacts and kept the bidders abreast of the event.!:? It should come as no surprise that they heeded what he said. I discuss their network and their dealing with Jan van Beu-ningen in greater detail in Part .. of this book. First, howev-er, let us turn to Jan Pietersz. Zomer as a broker at the auc-tion.

he paid :;!; guilders for an Adoration of the Magi ascribed to Rembrandt.!!> In !6;@ and !6;6 Van Beuningen attended the public sales of the cabinets of Jan de Walé and Petronella de la Court.!!@ He bought a Nativity by Bassano and one by Tin-toretto, respectively. Even earlier, in !6;!, at the sale of his friend Isaak Rooleeuw, Jan van Beuningen had bid on one of the most expensive paintings by Dou, ‘the famous grocer’s shop, with four fi gures.’!!6 Finally, in !6;= he bid on a land-scape by Rottenhammer and Brueghel – or Bril according to Van Beuningen’s catalogue – of a scene of ‘Parnassus en de Muzen,’ or Mount Parnassus and the Muses.!!<

This enumeration suggests that Van Beuningen built his col-lection largely through purchases made at auction. He was familiar with the system and even regularly bid himself. The amounts he paid for each of these acquisitions were excep-tionally high. Considering what he got in return one might even argue that they were poor purchases. He certainly suf-fered substantial losses on some of them. This may have had to do with the nature of the sale. For example, in !6!: he wrote that pieces he was able to sell privately fetched far more than ones that had to be sold post-haste at auction.!!= Why, then, did he sell everything he owned in !6!@? Two rea-sons can be forwarded. First, he was preparing to leave for Curaçao as governor of the West-India Company. Second, he appears to have lent far too much money to the Landgrave of Hessen-Kassel and his daughter Maria Louise, whereby he found himself in straitened fi nancial circumstances after !6!>.!:; While he did not go bankrupt, he did have to mind his pennies more. ‘The considerable sum the Royal house of Hesse continues to owe me, the loss of substantial sums

)'% 5.$,$&4F. F#3$&, +,,---.,,/ (0/1-2/)

>>

NAA, Dispute concerning an appraisal of two paint-ings, !) February #$#&, inv. >;6> no. ><;= folio ?@6. The painters were: Ludolf Bakhuizen (!@7;-!6;<), Jan van Huchtenburgh (!@?6-!677), David van der Plas (!@?6-!6;?) and Michel van Overbeek. Abra-ham du Pré was a leading collector. His collec-tion was auctioned in Amsterdam on !7 May !6:=. (See Hoet !6>:, vol. ., pp. 7?!-7?7.) Abraham du Pré appears to have been a family acquaintance. Jan van Beuningen’s brother, Isaac Samuel, was lat-er the executor of his estate and guardian of his grandchildren: ‘[...] that the late Isaac Samuel van Beuningen, in his life governor of the patented company for commerce of this province and co-executor of the estate, and co-guardian of the un-derage heirs of his grandparents [Abraham du Pré and Petronella Oortmans]’ ([...] dat wijlen de heer Isaac Samuel van Beuningen, in leven Bewindheb-ber van de geoctroyeerde compagnie van comercie deser provincie was geweest enne mede Executeur van het testament, mede voogd over de minderja-rige erfgenamen van zijn grootouders [Abraham du Pré en Petronella Oortmans]).’ Utrecht, GAU, NAU, Receipt with regard to the estate of Abraham du Pré, !! July #$%), inv. no. U!=!a! deed :;<.

#$'. ‘Op huijden, den :< Februarij des jaars !6;7 heb ik David Walschaart notaris Public, bij den Hove van Holland geadmitteert, binnen Amster-dam residerende, ten verzoeke van Christito van Boonevaal als gemagtigde van Otto Roger Costart, woonende te Parijs, mij des namiddags omtrent drie uuren vervoegd ten huijse van Abraham du Pré, koopman binnen deeze stad, alwaar toemaals mede gekomen is Hendrik van Beuningen, bene-vens de Schilders Bakhuijsen, van der Plas, Hug-tenburg, ende Overbeke, mitsgaders de Makelaar Jan Pietersz. Zomer: En heb ik notaris daar op den voorn: Hendrik van Beuningen geinsinueert, en togezegt, dat de voorn. Boonevaal, versant heb-bende, dat aldaar, ter requisitie van Jan van Beu-ningen, uijt kragte van zeker apoitement van den E. Agtb: geregte deezer Stad, inspectie zoude ge-nomen van twee Schilderijen, hij insinuant de zel-ve inspectie hield voor nul, en van geener waar-den; ende dat de zelve mits dien het regt van zijn insinuants principaal in geenen deele zouden ko-men te prejudiceren; werdende de zelve inspec-tie alleen toegelaten ter obedientie van den ge-melden apointemente [...].’ Amsterdam, GAA,

##". See Appendix B:, lot no. 7=.##&. Hoet !6>:, vol. ., pp. =7-=? and !;?-!!;. See Ap-

pendix B:, lot nos. = and ?.##'. ‘Het bekende kruydeniers winkeltje, met vier

fi guuren.’ Hoet !6>:, vol. ., pp. @:-@7. See Appen-dix B:, lot no. >=.

##(. Hoet !6>:, vol. ., pp. !7!-!77. See Appendix B:, lot no. @6.

##). Leeuwarden, Tresoar (RAF), Stadholder’s Ar-chive, Archive of Maria Louise von Hessen-Kassel, inv. no. !=, Letter from Jan van Beuningen to Mr de Her-toghe, !" December #$#!.

#$*. The Hague, KHA, Archive of Maria Louise von Hessen-Kassel, inv. no. 7>=, Letters from Jan van Beu-ningen to Maria Louise, #$#&-#$#'.

#$#. ‘De consideraabele somme soo mij het door-lugtig huijs van Hesse schuldig blijft, het verlies van tosienlikke somme buijten Lands, en het to-taale credit ter beurse uijtgestorve, is de oorsaake dat mij seer benard vinde [...] ik hebbe mij gerett door verpanding.’ The Hague, KHA, Archive of Maria Louise von Hessen-Kassel, inv. no. 7>=, Letter from Jan van Beuningen to Maria Louise, !& July #$#'.

#$$. The Hague, KHA, Archive of Maria Louise von Hessen-Kassel, inv. no. 7>=, Letter from Jan van Beu-ningen to Maria Louise, #' and !' September #$#'.

#$%. Van der Veen !==7, pp. !?>-!<<.#$!. The Hague, KHA, Archive of Maria Louise von

Hessen-Kassel, inv. no. 7>=, Letter from Jan van Beu-ningen to Maria Louise, ( May #$#&.

#$". S.A.C. Dudok van Heel wrote the authoritative article on Jan Pietersz. Zomer. Dudok van Heel !=66, pp. <=-!::. Nicolaas Verkolje (after A. Boone), Portrait of Jan Pietersz. Zomer, mezzotint, Amster-dam, Rijksprentenkabinet.

#$&. Muizelaar & Phillips :;;7; Dudok van Heel !=66, pp. <=-!::.

%# Nicolaas Verkolje (after A. Boone), Portrait of Jan Pietersz. Zomer, mezzotint, Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinet

>@

prints were involved, an appeal was often made to Zomer. It was, therefore, natural for him to maintain sound con-tacts with members of the town council and leading regent families, for instance the Sixes, primarily Willem and Pieter Six Senior and Junior.!7< This family counted many collec-tors and art lovers and in his capacity of broker Zomer liter-ally had the run of their house. For example, he organised the auction of the collection of Jan Six in !6;:, and that of Pieter, two years later in !6;?. And, it was also Jan Pietersz. Zomer who introduced John Drummond and Charles Dave-nant, the agents of James Brydges of Chandos, to the young-er Pieter Six. They were on the lookout for paintings to em-bellish Chandos’ country house. On this occasion they also called upon the heirs of Six’s brother-in-law, Burgomaster Joan de Vries, who likewise owned a notable art collection.!7= But more on this later. Other regent families, like the Feite-mas, the Van Lenneps or the heirs of Coenraad van Beunin-gen, also had reason to rely on Zomer’s services.

'55&'.4$& '%( '-*,.#%$$& – A brief passage from the travel diary of the – in the meantime well-known – Von UB enbach brothers neatly summarises what Zomer stood for: ‘In the morning of !@ February [!6!!] we went to the bro-ker Johann Pietersen Sonern [Jan Pietersz. Zomer]. We vis-ited him because we had heard that in addition to organis-ing auctions of pictures and other artful things, he owned a good stock himself and could give good advice. He showed us some fi ne paintings but apologised for not showing his prints and drawings – he owned some 7;,;;; of those – on account of the cold. They were stored in a room where he could not make fi re. He is a man of about @; and quite cour-teous, for he told us a lot about other beautiful cabinets, which we noted down so as to visit them afterwards.’!?; Par-ticularly the German travellers’ brief sentence to the eB ect that Zomer had enumerated the most important cabinets il-lustrates his central role in the Amsterdam connoisseurs’ mi-lieu around !6;;. By the end of his life, Jan Pietersz. Zomer could indeed bank on an unparalleled level of expertise. As an appraiser in public and private service he knew the ma-jority of the art collections in Amsterdam. There is no doubt that he kept a record of all of the appraisals and auctions in which he was directly or indirectly involved.!?! According-ly, he knew the provenances, attributions and sales prices of thousands of works of art like no one else. Moreover, he had an enormous print and drawing collection on which to fall back on for more diC cult attributions.!?: While others had to rely on visits to the collections of their connoisseur ‘friends’ to build up their expertise, Zomer had a passe-par-tout, as it were. It is striking just how systematically the term broker is

weeks after the fi rst appraisal in early December !6!:, Van Beuningen wrote to his patroness ‘I shall see how it goes with the broker Zomer.’!:< Van Beuningen’s misgivings about the broker’s appraisal are understandable. Zomer’s reputation among a sector of the art-loving public was not all that good, at least in the later lines of verse ridiculing him penned by Jan Goeree: ‘This is Jan Piet the broker, in art a joker.’!:= That brokers were not held in high esteem in the seventeenth cen-tury also emerges from Jacob Campo Weyerman’s character sketch of an art dealer that opens with the words: ‘There was and still is an old Dutch proverb: When our Lord gives us a merchant, then the Devil oB ers a broker.’!7;

Nevertheless, they both evidently deemed the collabo-ration in appraising the paintings at Het Loo as a qualifi ed success. At the end of December !6!:, Zomer and Van Beu-ningen together even appraised the estate of Maria Sautijn, widow of the famous publisher Joan Blaeu.!7!

/ 02'44 5'.%,$& ,# 8&#"$& – Jan Pietersz. Zomer’s career is peculiar. He was almost >; years old when he reg-istered with the Brokers’ Guild. In his youth he had been trained as a glass painter.!7: Neither his parents nor his fam-ily had any connection with art dealing. Moreover, he him-self (initially) displayed no interest in pursuing art brokering full time. In !@67 he took over the glass business of his uncle, with whom he had studied.!77 An ambition to devote himself fully to the appraisal and sale of paintings, prints, drawings and rarities evidenced itself only fi fteen years later. He prob-ably arrived at this under the infl uence – and pressure – of Adriaen Hendrick de Wees, who had preceded him as a bro-ker and merchant of prints and drawings and with whom he was well acquainted.!7? It is not entirely clear how he estab-lished his reputation as an appraiser as of !@<6.!7> And, it is equally diC cult to discern how he was able to make himself so indispensable. The fact is, though, by the end of his life, anno !6:?, he was a key fi gure in the Amsterdam art market. He dominated the auction world; a business he was instru-mental in professionalizing largely by means of newspaper advertisements and catalogues, as emerges below. In the eyes of his contemporaries, Jan Pietersz. Zomer’s greatest trump was his sound judgment of value.!7@ He cer-tainly was not lacking in experience. Between !@<6 and !6:? he was involved with no less than @: collections of paint-ings. Of them, ?7 inventories and appraisals had to do with deaths, != others with bankruptcies.!76 Hence, the munici-pal magistrate was an important, if not the most important commissioner of the appraiser and broker. The magistrate was responsible for having ‘desolate’ and ‘insolvent’ estates appraised for the sake of either the orphans or creditors. In the event that collections of paintings or drawings and

>6

#!!. ‘Weergaloos groot kabinet of verzameling van ongemene konstige en uytmuntende tekeningen van Italiaense, Franse, Duytse en Nederlandse, so oude als nieuwe meesters, met groote moeyte en kosten in meer dan >; jaren by een vergadert.’ Du-dok van Heel !=6@, p. !::.

#!". Dudok van Heel !=6>, pp. !?=-!67; Dudok van Heel !=6@, pp. !;6-!::. See also Appendix A7.

#!&. An additional argument for this is the absence of an account at the Exchange Bank in the name of Jan Pietersz. Zomer. As will emerge from this study, the settlement of a large part of the trade in luxury items, among others, with royal houses, transpired via this Exchange Bank.

#!'. See Chapter ?A.#!(. Bille !=@!, vol. ., p. !><. On art brokers in partic-

ular, see Bille !=@!, vol. ., p. !@> B .#!). Bille !=@!, vol. ., pp. !>6-!><. According to