Note on a Chinese Text Demonstrating the Earliness of Tantra

Text and Edition in Early Chinese Philosophical Literature

Transcript of Text and Edition in Early Chinese Philosophical Literature

Text and Edition in Early Chinese Philosophical LiteratureAuthor(s): Harold D. RothSource: Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 113, No. 2 (Apr. - Jun., 1993), pp. 214-227Published by: American Oriental SocietyStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/603026 .Accessed: 06/09/2011 15:17

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range ofcontent in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new formsof scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

American Oriental Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal ofthe American Oriental Society.

http://www.jstor.org

TEXT AND EDITION IN EARLY CHINESE PHILOSOPHICAL LITERATURE

HAROLD D. ROTH

BROWN UNIVERSITY

Students of the textual history of Chinese works of all periods and genres encounter the problem that we do not always distinguish clearly between the concepts of "text" and "edition." A further problem arises when one seeks to differentiate the strata of editions relating to the textual history of

a given work. In this article, based on the author's research into the textual history of three early philosophical works, Huai-nan Tzu, Chuang Tzu, and Lao Tzu, an attempt is made to resolve these issues by proposing working definitions for the key terms, "text" and "edition," and for a number of

other related terms, including "exemplar," "recension," "redaction," "ancestral redaction," "re- ceived text," and "witness." The relevant Western text-critical models are surveyed and the closely related fields of textual history and textual criticism are discussed with regard to Chinese works.

INTRODUCTION

DURING THE YEARS I have been working on the textual histories of a number of important sources of early Taoist philosophy such as the Huai-nan Tzu and the Chuang Tzu, I have had to confront some conceptual problems in the analysis of my data and have had to adapt and develop working definitions for a number of important technical terms for which there does not seem to be a consensus among scholars working in the field. In my opinion, the two most important of these problems are: (1) how are we to understand the differ- ence between the terms "text" and "edition"; and (2) once we decide what we mean by "text" and "edi- tion," how are we to identify and discuss the various strata of editions that arise during the transmission of a text, and how do they relate to the idea of a "received text" (textus receptus)? I regard the resolution of these problems to be of the utmost importance for the fields of textual history and textual criticism.

In this paper I will present the working definitions I have developed for the above terms and set them in the context of how I view textual history and its relation- ship to textual criticism. In the course of presenting the ways in which I have dealt with these problems, I will set forth some old and some new definitions for a num- ber of other terms I view as central to the field of textual history, including "recension," "redaction" and "ancestral redaction," "direct and indirect testimony," and will also touch upon a methodology I've developed for determining the lineages of the editions of a text, which I call "filiation analysis."

TEXT AND EDITION

I would like to begin with the observation that quite often scholars in our field fail to distinguish clearly be- tween text and edition. More specifically, the failure often comes in identifying a particular edition of a text as a text. For example, is the unique version of the Huai-nan Tzu &MI created by the Ch'ing scholar Chuang K'uei-chi U a text or an edition? Is the 33-chapter version of the Chuang Tzu established by Kuo Hsiang aft a text or an edition (or something else again, as I will suggest below)? And are the Ma- wang-tui ,%i. E manuscripts of the Lao Tzu to be thought of as texts or editions?

That Sinologists should often be unclear in their use of these terms will come as no surprise when we recog- nize that in many cases the paradigm we use for our own studies, Western textual scholarship in New Tes- tament, Greek and Latin, and English literature, fails to enunciate clearly the distinction between these two terms.' I can only speculate on the reasons for this, but

1 I have been able to locate neither a clear definition for, nor

a distinctive pattern of usage of, these terms in such otherwise

outstanding works of textual criticism as Kurt Aland and

Barbara Aland, The Text of the New Testament, tr. Erroll F.

Rhodes (Grand Rapids, Mich.: William B. Eerdmans, 1987);

and James Thorpe, The Principles of Textual Criticism (San

Marino, Cal.: Huntington Library, 1972). While Thorpe

(p. 183) does define "text," he does not distinguish it from

"edition." I wish to thank my colleague Stanley Stowers for

214

ROTH: Text and Edition in Early Chinese Philosophical Literature 215

my admittedly cursory survey of the relevant literature leads me to believe that it may have something to do with the predominance and remarkable survival of manuscript traditions in the transmission of the major texts of the ancient Western world.2 There is a ten- dency to refer to these manuscripts and their copies as "texts" and to their much later printed versions as "edi- tions,"3 perhaps because so many of the former are copies and hence the product of scribes that involved little of the sifting, sorting, and emending work we commonly associate with critical editing. In China, given the relatively early invention of printing, com- pared to the West, the great majority of extant editions are printed, and so from the Western practices, should not be referred to as "texts." However, the manuscript copies of texts that circulated prior to this are no less "editions" than the later printed versions that now sur- vive, and, in my opinion, in most cases should also not be referred to as "texts" in light of the definition I will propose below. In any case, given the predominant influence of Classical and Biblical textual studies in the field, perhaps their tacit assumptions about "texts" and "editions," drawn from the specific conditions of their source materials, have remained largely, but not entirely, unexamined. Not entirely, I say, because the basis for a definitive distinction between text and edi- tion has been clearly drawn in the scholarship of Vin- ton Dearing,4 whose text-critical methodology was first applied to Chinese texts by Paul Thompson in his re- construction of the Shen Tzu fragments.5

For Dearing, who relies on "information theory" for his basic definitions, the "text" is a unique complex and

expression of ideas created by an author or authors.6 Ac- cording to him, in information theory this is called the "message." It is the stated goal of textual criticism to lo- cate-in the unlikely event it still survives intact-or to re-establish, if it does not, this original text. This is in- deed the commonly accepted goal of textual criticism.

Dearing further maintains that the "states" of a text are the various "forms" of the original "message" as de- termined in the process of "textual analysis," Dearing's name for his particular methodology for sorting out the various states of a text and their unique textual variants and determining the state from which they have de- scended in preparation for the final emendations that are the last stage in the critical process. The actual physical objects in which the forms of the message or states of the text are embodied are called the "records" of the text. In information theory these are called the "trans- mitters."7 In my own analysis, in the Chinese context at least, these "records" constitute the "editions" of a text.

A recent and very perceptive article by G. Thomas Tanselle places Dearing's work in the context of the entire Western tradition of textual criticism, and it would be instructive to take a moment to examine this.8 Tanselle talks about two general approaches to preparing a new edition, one that has been favored by scholars who work with ancient and medieval texts, and one that has been favored by scholars who work with modern texts. In the former, due to the antiquity of the texts, where there is little hope of recovering an author's original manuscript, scholarly efforts have been devoted to establishing a critical edition that is the best approximation of the authorial original by careful analysis of the extant testimony to that text. In the latter, due to the existence of various editions or autograph manuscripts of a text that are often produced during an author's lifetime, scholarly efforts have turned more to deciding upon an authoritative "copy- text" to use as the basis for the new edition.9

calling my attention to the seminal work of the Alands on New Testament textual criticism.

2 For example, Aland and Aland, 34, note the existence of over 5300 manuscripts of the Greek New Testament (this is to say nothing of the many manuscripts found in other lan- guages such as Latin, Syriac, Coptic, Armenian, and so on), and Thorpe, 109, adds that while not all are complete, this "embarrassment of manuscripts" has necessitated the classifi- cation into various."family" groupings (Byzantine, Caesar- ean, Alexandrian) and made it possible to use only sample passages to analyze their complex relationships and assess the possible value of their variant readings.

3 See, for example, the excellent summary of the editions of the New Testament in Aland and Aland, 3-47.

4 Vinton Dearing, Principles and Practices of Textual Analysis (Berkeley and Los Angeles: Univ. of California Press, 1974).

5 Paul M. Thompson, The Shen Tzu Fragments (Oxford: Ox- ford Univ. Press, 1979). Thompson made use of an earlier

work of Dearing's, A Manual of Textual Analysis (Berkeley and Los Angeles: Univ. of California Press, 1959). The mate- rial he used from Dearing remained essentially unchanged in Dearing's later work.

6 Dearing, Principles, 1. 7 Dearing, Principles, 1-2, 13-15. 8 G. Thomas Tanselle, "Classical, Biblical, and Medieval

Criticism and Modern Editing," in Tanselle, Textual Criticism and Scholarly Editing (Charlottesville: Univ. of Virginia Press, 1990), 274-321. I wish to thank both Susan Cherniak of Smith College and I. J. McMullen of Oxford University for calling Tanselle's work to my attention.

9 Tanselle, 276-78.

216 Journal of the American Oriental Society 113.2 (1993)

Dearing falls squarely in the former tradition, which he himself claims began with the development of the "genealogical method" by the New Testament scholar, Karl Lachmann (1793-1851).10 He further maintains that his work has gone beyond Lachmann's reliance on common textual errors (that is, outstanding textual variants) by incorporating the formal logic and statisti- cal analysis pioneered by Sir Walter Greg and Dom Henri Quentin." According to Tanselle, Dearing's work still falls within "classical textual criticism," which involves two fundamental stages, recensio and emendatio.12 In the former, after surveying the extant sources of textual testimony and choosing only the most important, one next analyzes their patterns of tex- tual variants and constructs a genealogical tree, techni- cally called a stemma codicum, which one then uses to decide among the variants and to construct the textual archetype of this testimony. In the second stage, wher- ever the stemma fails to decide among the variants, one must make the decision oneself, on the basis of what the famous textual scholar, Paul Maas, calls "conjec- ture" (divinatio).13 Dearing's methodology of "textual analysis" is a procedure of the recensio stage. How- ever, he differs from such classical statements of the methodology of this stage, as found in Maas, in at- tempting to clarify the formal logic that underlies it, incorporating statistical analysis of textual variants, and in making a new distinction that he regards as ex- tremely important.

In Dearing's definition, "textual analysis" determines the genealogy of the variant "states" of the text; "bibli- ography" determines the genealogy of the "records" of the text, and it is absolutely imperative not to confuse the two. 14 He regards this as one of the central achieve- ments of his methodology, freeing "textual analysis" from "bibliographical thinking," which must consider the dates and circumstances of creation of particular records. This ultimately leads him to be able essen-

tially to do away with the problem of conflation, which bedeviled earlier "genealogical" or "stemmatic" ap- proaches such as that of Maas. When two states of a text are freed from their bibliographical records, one needn't worry that a third state is a conflation of them; it is simply a third state and may be either a combina- tion of the two or their common ancestor. However, as Tanselle points out, Dearing's mechanical solution (the formation and breaking of textual rings at their weakest statistical link, uninfluenced by dating) does not really do away with the problem of conflation: it simply ad- dresses it from another point of view.'5 Furthermore, I agree with Tanselle in objecting to the exclusion of "bibliographical" evidence. Such evidence is often ex- tremely valuable in establishing the filiation of editions necessary for the construction of the stemma and can be extremely valuable in delimiting the textual testi- mony that one must consider in order to establish a critical edition. Also, it often provides valuable infor- mation as to how certain states of a text arose. As Tanselle rightly says, "physical details sometimes ex- plain textual variants," and that without knowing how the variants in a particular record of a text arose, " . . . one may postulate relationships that are shown by physical evidence to be incorrect."'6

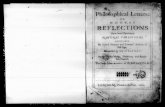

Let me give an example from my work on the Huai- nan Tzu. In my text-historical analysis of the Chung-li ssu-tzu chi @ YX IZ! - edition of 1579, I discovered that it is a conflation of two earlier editions: the An- cheng t'ang ViES edition (1533) from the lineage of the Tao-tsang redaction of 1445 and the Wang Ying IEM edition (ca. 1536) from the lineage of the Liu Chi W-1 redaction of 1501, and so does not need to be included in the establishment of a critical edition.' Among the factors determining this is a rather unusual "physical detail": the textual variants from the Wang edition were cut into the printing blocks of the Chung- li edition after the An-cheng t'ang edition was already engraved into them. This is particularly noticeable wherever the Wang edition was more wordy and the block carver had to re-engrave two characters where there had previously been only one (see plate 1).18

10 Dearing, Principles, 5. 11 Dearing, Principles, 9-16. Greg's Calculus of Variants

was published in 1927; Quentin's MWmoire sur l'e'tablissement du texte de la Vulgate was published in 1922.

12 Thorpe, 113-15, classifies traditional textual analysis a bit differently than Tanselle, referring to three forms: 1) the genea- logical method of Lachmann; 2) the "best-text" method of Joseph Bedier (1913); and 3) the statistical method of Quentin and Greg. He classifies Dearing with the last grouping.

13 Tanselle, 278-79. The single most influential statement of this methodology has been Paul Maas, Textual Criticism, trans. Barbara Flower (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1958).

14 Dearing, Principles, 2, 14-20.

15 Tanselle, 314-15. 16 Tanselle, 317 and 287-88. 17 This information is taken from H. D. Roth, The Textual

History of the Huai-nan Tzu, Association for Asian Studies Monograph no. 46 (Ann Arbor: Association for Asian Studies, 1992), 203-24.

18 Roth, Textual History, 212-22, contains further examples and demonstrates how this physical evidence concurs with the textual and historical evidence for conflation in this edition.

ROTH: Text and Edition in Early Chinese Philosophical Literature 217

W00~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~NW

a ek 4 - ; N6k t^<

Ifwl,-l~et~b}L ffi,.,, a alg

E ~ As ~ ~ ~ ~ A

hi_

Plate 1: The Chung-li ssu-tzu chi redaction, Harvard-Yenching exemplar, chapter 12, folio 4, verso. Line 4: An-cheng t'ang edition: R:: T f-t- .i A V . A t R tt , T .... Wang Ying edition: .. T it l A .1 L_ A t .R . I

. . ..

218 Journal of the American Oriental Society 113.2 (1993)

Dearing would have us exclude such "bibliographical" considerations, but without them one would be unable to determine that this edition was wholly derivative, one might postulate that it was the common ancestor of the other two, and one would have to include its testi- mony in establishing a new critical edition. Indeed, act- ing without the benefit of this kind of information, the dean of modern Chinese textual critics, Wang Shu-min lEiVIR, felt it necessary to write an appendix to his superb collation and emendation of the Huai-nan Tzu that included the variants from this Chung-li ssu-tzu chi edition.19 Therefore, in this example, what Dearing calls bibliography has accomplished precisely the op- posite of what he thinks it can do, that is, eliminate conflation. By discovering that conflation has occurred in this Chung-li edition, and that the two editions that were conflated are still extant, we can eliminate this wholly derivative witness from inclusion in our critical edition and thereby eliminate the problems caused by its being conflated. Other important examples of the benefit for textual criticism of understanding the filia- tion of extant witnesses could be adduced.20

One does not need to agree with Dearing that biblio- graphical evidence must be excluded from textual analysis in order to use his methodology or to agree with his clear distinction between the states of a text and its records. Indeed, this distinction is fundamental to my own definition of an edition and is the reason that in my work on the Huai-nan Tzu I have pursued it in the following way.

In my analysis, each new edition of a text is a dis- tinct record. If it is a new printing with only minor re- visions or a hand-traced or mechanically reproduced facsimile edition, it may contain a "state" of the text that is essentially the same or even identical with the "state" contained in an earlier "record." Nonetheless, because it is produced at a distinct moment in time by a distinct publisher and often by a distinct editor, I have considered it a distinct edition.

While not including subsequent unaltered impres- sions made with the same printing blocks as distinct editions (whenever I could determine this), if I found evidence of editorial modification or if there was a new publisher, I identified the product as a distinct edition, usually labelling it a "revised edition." Included in this category are editions described by the following tra- ditional Chinese bibliographical terms: ch'ung-k'o-pen -1,VJA or fan-k'o-pen U]J* (re-engravings), and hsiu-pu-pen PiM* (repaired engravings). I restricted the term "reprint" to two categories of printed edi- tions: (1) those based upon either a meticulous hand- tracing (usually ying-k'o-pen FlJ* or ching-ch'ao- pen I'*) or a modern mechanical copying (usually ying-yin-pen F JP *) of an original edition, such as the Ssu-pu ts'ung-k'an edition of the Huai-nan Tzu; and (2) those that are variant printings of an original edi- tion by a new publisher to which no editorial changes were made to the main body of the work, a subset of which are the chuan-pan Phi (converted block) edi- tions, such as Chang Hsiang-hsien's g-14t 1593 re- print of the Wang I-luan afE-* edition of 1591 that was made with the original blocks and only substituted Chang's name as editor (see plates 2 and 3).21 I con- sider it important to identify clearly all such states as editions, even though the state of the text they repre- sent might be essentially unchanged, because it is a distinct possibility that even in the creation of a new facsimile the state of the text being copied may be- come altered in a way that could have important impli- cations for textual criticism.

An excellent example of this, and one, as well, of how bibliography-or what I prefer to call "textual history"-can help with textual criticism, is found in the nineteenth-century transmission of the surviving copy of the oldest extant complete redaction of the Huai-nan Tzu, that known as the "Northern Sung small-character edition." Until about 1818 it was part of the collection of the famous bibliophile Huang P'ei- lieh AM ; f! (1763-1825). In 1824 a traced facsimile of it was made by the copyist Chin Yu-mei k By at

19 Wang Shu-min, "Huai-nan Tzu chiao-cheng pu-i M M IAKiM," in Wang, Chu-tzu chiao-cheng Ma: 12 (Tai- pei: Shih-chieh, 1963), 479-82. The book collects 19 articles on the textual criticism of pre-Han and early Han philosophical works that Wang published between 1952 and 1962.

20 In particular, the filiation analysis of the Liu Chi redac- tion of the Huai-nan Tzu indicates that it was a conflation es- tablished from three earlier editions that are no longer extant, loosely identified by Liu as the "old edition" (his basic text), the "other edition," and the "different edition." The analysis of the textual variants from these editions that Liu included in his textual apparatus definitely shows that the first of these, the "old edition," was closely affiliated with an immediate an- cestor of the Tao-tsang redaction and is the source of the read- ings that have led previous scholarship to conclude that the Liu Chi redaction was a direct descendant of the Tao-tsang. Filiation analysis also indicates that Liu's other two editions are distinctly different from any of the other sources of the di- rect tradition and probably represent a very early state of the text, possibly from the lost Hsu Shen recension. For details see Roth, Textual History, 170-87, 332-33. 21 For this edition, see Roth, Textual History, 243.

ROTH: Text and Edition in Early Chinese Philosophical Literature 219

at~~~~~~~~~~~o

A._ l_ i_______ - I - i

I- -t - 1-1 I Ilit;''Vt, X, t t ;fi)? t t) Elyq I 8 I " 1

I T~t-

Plate 2: The Wang I-luan edition (1591); Naikaku Bunko exemplar (photo- reduction), chapter 1, folio 1, recto.

220 Journal of the American Oriental Society 113.2 (1993)

NII

Plate 3: Chang Hsiang-hsien reprint edition; Naikaku Bunko exemplar, chapter 1, folio 1, recto.

ROTH: Text and Edition in Early Chinese Philosophical Literature 221

the behest of Wang Nien-sun's -T best student, Ch'en Huan 1t% (1786-1863). A decade later, in 1834, Ch'en improved its readings by collating it with another traced facsimile, done by Ku Kuang-ch'i ON*Jj (1776-1835). In 1872 Liu Lu-fen 11JRJ1 (1827-79) made yet another facsimile and this was photolithographically reproduced by the Commercial Press in 1920 in the first series of the Ssu-pu ts'ung- k'an.22 All facsimiles except Liu's are now lost, but this and further text-historical analysis indicates that erro- neous readings were introduced by the nineteenth- century copyists into what is now the SPTK edition that were not included in Huang P'ei-lieh's original copy. Without the information provided by this text- historical analysis we would assume that the SPTK edi- tion represents the state of the original Northern Sung redaction and we might not therefore be able to recover its original readings.23 Therefore it is important to identify each distinct record of a text and list it as an edition, even though it might seem on the surface that facsimile editions incorporate the same state of the text as the one from which they are copied.

To return to our earlier definitions, an edition, then, is the actual physical record of a particular state of a text. Hence, what was published by Chuang K'uei-chi is an edition of the Huai-nan Tzu, not a text of the Huai- nan Tzu. Kuo Hsiang did not create a new text of the Chuang Tzu: there is only one text of the Chuang Tzu. The Ma-wang-tui manuscripts are, at the very least, edi- tions of the Lao Tzu; they are not texts. Each contains a record of a unique state of the text, but is not the text it- self. There is only one "text." It may-and invariably does-change over time; it is transformed into the many states contained in the records that are its edi- tions. But in the last analysis, these states and records must not be equated with the text itself.

Further refinements to these definitions are taken from Thompson. An "exemplar" of an edition is one particular impression of a printed edition or the actual manuscript of a handwritten edition.24 Each copy of an

edition is thus an exemplar. Therefore one can speak of the Gest Oriental Library's exemplar of the Mao I-kuei *-Ad edition of the Huai-nan Tzu (1580) and the Naikaku Bunko's exemplar of the Wu Chung % 411 edi- tion of the Huai-nan Tzu (ca. 1540), and it is important to note these for two reasons. Slight editorial changes can be entered into new impressions made from the same printing blocks and the quality of the impression deteriorates as more copies are made. So, even though I do not list exemplars as distinct editions, it is impor- tant to record which exemplar of an edition one is us- ing. Second, what I call "hand-collated exemplars" (chiao-pen to *)-individual copies of an edition onto which a scholar records his collations and emen- dations-are an important form of scholarship, and the many extant Ch'ing examples of this medium are im- portant sources of information for textual studies.25 Another definition of Thompson's is of a "witness," which is "a particular manuscript or printed exemplar which testifies to a text."26 This definition concurs with Western textual scholarship.

Again following Thompson, all of the extant com- plete and fragmentary editions of a text are collectively referred to as the "direct tradition" of that text, and are said to contain its "direct testimony." For the Huai-nan Tzu, we have eighty-seven complete editions in the di- rect testimony and thirty-three fragmentary or abridged sources. The often very extensive body of quotations from-and paraphrasings of-a text found in encyclo- pedias, commentaries, and other related sources is col- lectively referred to as the indirect tradition of that text, and is said to contain its "indirect testimony."27 Thomp- son worked exclusively with this latter, general source in establishing his new critical edition of the Shen Tzu fragments. In so doing he placed himself squarely in the tradition of Ch'ing scholars such as Sun Feng-i At X, Mao P'an-lin 00 4f 4*, and T'ao Fang-ch'i RI )3 i%, who assembled what Thompson calls "reconstituted redac- tions" of lost works from their indirect testimony.28

22 Roth, Textual History, 133-37. 23 We can reconstruct these readings because of the survival

of a facsimile of Ku Kuang-ch'i's hand-collated exemplar of the Chuang K'uei-chi redaction, onto which he recorded all variants between this and Huang's original copy of the North- ern Sung redaction. By comparing these variants with the SPTK edition, we can see which errors were introduced by the nineteenth-century copyists and thereby recover the original readings. For details see Roth, Textual History, 137-41, 287- 90, and 397 n. 67.

24 Derived from Thompson, xxi.

25 See, for example, the list of 43 chiao-pen of the Huai-nan Tzu and their locations in Wu Tse-yu O UIJ E, "Huai-nan Tzu shu-lu" i : , Wen-shih IZC4 2 (1963): 287-315, esp. pp. 301-6. The scholars whose critical collations and emenda- tions are recorded in these exemplars reads like a Who's Who of Ch'ing textual criticism.

26 Thompson, 180 n. 2. 27 These terms are used in this manner throughout Thompson's

work, but nowhere does he provide a concise definition of them. 28 Sun Feng-i (d. 1799), Hsu Shen Huai-nan Tzu chu

~Ft M Ph 7- i, included in Wen-ching-t'ang ts'ung-shu R 2 : (1802), Ts'ung-shu chi-ch'eng ch'u-pien edition;

222 Journal of the American Oriental Society 113.2 (1993)

CRITERIA FOR DIFFERENTIATING STRATA OF

THE DIRECT TESTIMONY

In the course of studying the textual history of a given work it becomes necessary to distinguish among the various strata of editions that are the descendants of the very first edition of a text. Without so doing we would be forced to consider such awkward and obfus- catory locutions as the "Huang Cho Am edition of the Wang Ying edition of the Liu Chi edition of the conflated Kao Yu/Hsu Shen edition of the Huai-nan Tzu," or the "Kuo Ch'ing-fan _`fl* edition of the Ku-i ts'ung-shu -NINIX edition of the Southern Sung edition of the Ch'eng Hsuan-ying fi 32 M edition of the Kuo Hsiang edition of the Chuang Tzu."

In order to deal with this problem, in addition to sort- ing out the various levels of the direct testimony to a text, one must find suitably clear terms to distinguish among them. For the most primary level, I have used the term "recension," which the Oxford English Dictio- nary defines as "the revision of a text, especially in a careful or critical manner; a particular form or version of a text resulting from such revision."29 In practice, this term is most often applied to foundational versions of canonical works in Christianity, Buddhism, and Tao- ism. For example, Biblical scholars refer to the K, H, and I recensions of the New Testament.30 For Bud- dhism, we have the Pali recension of the Buddhist canon that has been compiled and transmitted in the various Theravada schools of South and Southeast Asia, the Chinese recension of the Buddhist canon that has been transmitted in the various Mahayana schools of East Asia, and the Tibetan recension of the canon transmitted in Vajrayana Buddhism.31 For Taoism we

could speak of the Northern Sung recension of 1019, called the Ta-Sung t'ien-kung pao-tsang, )* , i

W B and the Ming recension of 1445, generally known as the Cheng-t'ung Tao-tsang iE ; a M.12 Common to each of these diverse usages of the term "recension" is the notion of a revised foundational version of the works in question.

It is this notion of a foundational version that makes the term "recension" particularly suitable to the most primary level in the direct tradition of an individual text. In the textual history of the philosophical works with which I am most acquainted, there are only a very small number of foundational versions. For the Huai-nan Tzu, we have the recension that Liu Hsiang PI [1 established from the two copies of the original manuscript edition of Liu An PI V (the one that he presented to Emperor Wu, and the one Liu Te PIJ ti presumably found when he set- tled Liu An's estate); the independent recensions of Hsu Shen and Kao Yu, both of which were based on the now lost Liu Hsiang recension but which contained their own unique textual variants; and the composite recension of thirteen Kao Yu and eight Hsu Shen chapters, which is the sole recension extant today.33 For the Chuang Tzu, we have the long-lost original recension in 52 chuan or chapters, now known only through bibliographical ref- erences and indirect testimony, and the 33-chapter re- cension that Kuo Hsiang established that is extant today.34 The textual history of the Lao Tzu is more complicated. There appear to be three extant complete recensions: the one represented by the Ma-wang-tui manuscripts (ca. 200 B.c.) discovered two decades ago; the conflated recension of Fu I MR q (554-639); and the extremely well-circulated recension of Ho-shang-kung

IM ?6t (dated between the second and fifth centuries

Mao P'an-lin, Huai-nan wan-pi shu i ME W, included in Shih-chung ku-i shu + 1- i- i , ed. Mei Jui-hsien skW R (1823), Ts'ung-shu chi-ch'eng ch'u-pien edition; T'ao Fang-ch'i (1845-84), Huai-nan Hsu-chu i-t'ung ku ift fi SF ~ itWX1

(1881), 2d edn. (1884, including two supplements, pu-i MiN and hsu-pu AMi) (rpt., Taipei: Wen-hai ch'u-pan-she, n.d.).

29 O.E.D., s.v. 30 These recensions are found in the German critical edition

of the New Testament established by Hermann Freiherr von Soden (Aland and Aland, 22). The K recension is the Koine, the H is the Hesychian or Egyptian, and the I is the Jerusalem. They are also referred to therein as "text-types."

31 For a concise overview of the contents of each of these Buddhist canonical collections, see Richard H. Robinson and Willard L. Johnson, The Buddhist Religion: A Historical Introduction, 3rd ed. (Belmont, Calif.: Wadsworth, 1982), 270-72.

32 The most detailed study of the origins and development of the various Taoist canonical collections is Ch'en Kuo-fu

Ng 1, Tao-tsang yuan-liu kao 2 K a, ii Ji, 2nd ed., 2 vols. (Peking: Chung-hua, 1963). Studies in English include: Ofuchi Ninji, "The Formation of the Taoist Canon," in Facets of Taoism, ed. Welch and Seidel (New Haven: Yale Univ. Press, 1979), 253-67; Piet van der Loon, Taoist Books in the Libraries of the Sung Period: A Critical Study and Index, Ox- ford Oriental Monographs no. 7 (London: Ithaca Press, 1984), 29-63; and Judith M. Boltz, A Survey of Taoist Literature: Tenth to Seventeenth Centuries, China Research Monograph no. 32 (Berkeley: Institute of East Asian Studies, Univ. of California, Berkeley, 1987), 1-18.

33 Roth, Textual History, 27-29, 56-57, 76-78, 343-44. 34 H. D. Roth, "Chuang Tzu," in Early Chinese Texts: A

Bibliographical Guide, ed. M. Loewe (Chicago: Society for the Study of Early China, forthcoming).

ROTH: Text and Edition in Early Chinese Philosophical Literature 223

A.D.).35 Research by William Boltz, Rudolph Wagner, and others has clearly demonstrated that the edition of the text that now occurs with the Wang Pi I- % (226- 49) commentary is not from the original recension of Wang, but instead is extremely close in its readings to the extant Ho-shang-kung recension.36 Whether this extant Ho recension is-despite certain textual varia- tions-the original Ho recension (as Wagner implies) or whether it and the extant Wang Pi edition are part of a later conflated Wang/Ho recension (as Boltz would have it) has not yet been definitively established. There is also the fragmentary manuscript edition (containing chs. 1-37) of Hsiang Erh By T4 (dated between the sec- ond and fifth centuries) discovered at Tun-huang and long thought to be the product of the Celestial Masters sect of Taoism. This should probably be regarded as a distinct recension, because Boltz has shown it contains unique textual variants seemingly made for doctrinal purposes.37

From these examples one notices two important characteristics: many of these foundational versions of a text are associated with an ancient commentary; and each of them has its own distinctive pattern of textual variants and unique organization, thus indicating that a certain amount of editorial revision was involved in their creation. So my working definition of a recension is: a foundational version of a text that exhibits a dis- tinctive pattern of textual variants and sometimes a unique textual organization and which is often associ- ated with a particular ancient commentary on the text.

The surviving version or versions of a text-in my analysis, its recensions-are also commonly referred to as the "received text" or textus receptus. Hence the re- ceived text of the Huai-nan Tzu is the conflated Kao/ Hsu recension, that of the Chuang Tzu the Kuo Hsiang recension, and, for the Lao Tzu, is represented by the three recensions named above, the Ma-wang-tui, the Fu I, and the Ho-shang-kung (or Wang/Ho conflated). This term is not to be confused, as some scholars have done, with the edition a scholar chooses to use as the basis for collation with other editions in preparing a new critical edition.38 An edition used for the latter purpose is what Dearing refers to as the "lemma" and what others refer to as the "copy-text."39

35 For an excellent summary of the extant direct testimony to the Lao Tzu see Rudolph G. Wagner, "The Wang Bi Recension of the Laozi," Early China 14 (1989): 27-29, 31-40.

36 See Wagner, 27-54, and two articles by Boltz: "Textual Criticism and the Ma Wang tui Lao Tzu," Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 44.1 (1984): 185-224, esp. 221-23, and "the Lao Tzu Text that Wang Pi and Ho-shang kung Never Saw," Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 48.3 (1985): 493-501.

In addition, working with the limited selection of textual variations in appendix II of Wagner's article (in which he compared the "received text" of Wang Pi with the Sung edi- tion of Fan Ying-yuan and to which I added the relevant read- ings from the extant recensions of Ho-shang kung and Fu I), I determined that of the total of ninety-four variations among these sources there was at least affinitive agreement (identical but for a radical) between the Wang and Ho readings in sev- enty-two (seven affinitives; the rest identical) of them (and be- tween the Fu and Fan readings in sixty-seven of them). The only variations between the Wang and Ho recensions were those that were unique to each of them (and not shared with the other three sources). Thus the extant editions of Wang Pi and Ho-shang kung are very close and very likely part of the same recension. The editions of Ho, Fu, and Fan I consulted were from Yen Ling-feng iR M A, Wu-ch'iu-pei chai Lao Tzu chi-ch'eng ch'u-pien, e S 4 Jfi V m, cases 2, 2, and 7, respectively.

37 William G. Boltz, "The Religious and Philosophical Significance of the 'Hsiang Erh' Lao Tzu in the Light of the Ma-wang-tui Silk Manuscripts," Bulletin of the School of Ori- ental and African Studies 45.1 (1982): 95-117.

There are several other important extant sources to the text of the Lao Tzu that can be linked with the above recensions: Yen Tsun's A9 * Tao Te chen-ching chih-kuei M t A ;! k a (ca. 50 B.C.), which Wagner (p. 37) says is close to the extant Ho-shang kung recension; the fragmentary Tun-huang manu- script edition (chs. 51-81) of Su Tan Xit (270 A.D.), which Wagner (p. 28) says is closely linked to the extant Ho-shang kung recension; and the Sung edition of Fan Ying-yuan Mg -Tt, entitled Lao Tzu Tao Te ching ku-pen chi-chu t 7 l M d t * W it, which, based on my own collation results given above, can probably be considered an edition of the Fu I recension.

38 For example, see Charles LeBlanc, Huai-nan Tzu: Philo- sophical Synthesis in Early Han Thought (Hong Kong: Hong Kong Univ. Press, 1985), 63, 65, who states that contempo- rary Chinese scholars use the Tao-tsang edition of the Huai- nan Tzu as the "textus receptus of their textual studies... because they consider it the best ancient edition of the Huai- nan Tzu."

39 I do not here mean to equate Dearing's lemma with the copy-text of other scholars such as Thorpe and Tanselle. The principal difference between them is that Dearing does not give his lemma the same authority in determining variant read- ings as the others do their copy-text, which is selected as the most authentic possible version of the text located by biblio- graphical analysis. Dearing's lemma can be arbitrarily chosen

224 Journal of the American Oriental Society 113.2 (1993)

The reason for this confusion comes, I think, directly from the popularization of the term textus receptus by the Dutch publisher Elzevir, who in 1633 reprinted the first printed edition of the Greek New Testament, ed- ited by the famous humanist, Desiderius Erasmus, which was published in 1516. To promote their new edition, Elzevir's advertisement said, "What you have here, then, is the text which is now universally ac- cepted: we offer it free of alterations and corruptions" (Textum ergo habes, nunc ab omnibus receptum: in quo nihil immutatum aut corruptum damus).40 For the next three centuries this Erasmus edition was known by this characterization as the textus receptus; and even though it had been established on the basis of only a small and relatively late sample of the extant testimony and was filled with errors, it was the authori- tative source that only bold scholars dared to question. As such it served as more than "copy-text"; it was the "best-text" in Bedier's sense of the word.41

A further characteristic of what I call a recension is that it is a version of a text that can persist through many generations of editions. To be more precise, in my use of the term, a recension itself is not an edition: it is, to return to Dearing's definitions, a foundational state of a text that is contained in its many different records. Hence the Ma-wang-tui recension of the Lao Tzu is contained in both manuscripts A and B, and the conflated Kao/Hsu Huai-nan Tzu recension is con- tained in the entire corpus of direct testimony to this text. In order to help distinguish further the various strata of the direct testimony contained within the ex- tant editions of a text, I have used two other terms, "re- daction" and "ancestral redaction," and have developed a method called "filiation analysis" for determining the lineages of editions of the direct tradition.

The term "redaction" is, generally speaking, a syn- onym for "edition," more precisely a new edition, and its definition in the Oxford English Dictionary empha- sizes that a certain amount of revision and rearrange- ment are entailed in creating a redaction.42 In my research I have used the term "redaction" to distinguish

a new edition, created from one or more ancestors, that exhibits a unique format, a unique arrangement of text and commentary, and certain characteristic textual vari- ations.43 Remembering that a recension is a founda- tional state of a text, but that it is not a "record," that is, an actual physical object, we can say that each recen- sion of a text began as a distinct redaction. However, during the course of textual transmission, a varying number of new redactions of the recension may be cre- ated. For example, in my research on the Huai-nan Tzu I determined that the conflated Kao/Hsu recension did not begin in the Northern Sung, as had previously been thought, but rather during the fourth century.44 I would designate as a "redaction" the now lost "first edition" (editio princess) of this new "recension." Some seven centuries later, in 1063, the later-to-be-famous scholar- statesman, Su Sung HIM (1020-1 101), while working as an editor in the Academy of Scholarly Worthies (Chi-hsien tien 1% N Ar), established a new redaction of this recension, based on seven editions available to him. In creating his new redaction Su realized that eight chapters from the original Kao Yu recension had been lost and signaled this by leaving them without commen- tary. He indicated this at the head of each appropriate chapter with the phrase "commentary now lost."45 Both Su's work and the original edition from the fourth cen- tury qualify in my definition as "redactions."

In the vast majority of cases in early Chinese philo- sophical literature, the redaction that contained the very first record of a recension is no longer extant. Al- though I have not been able to examine this question in detail, one possible exception might be the case of the Ma-wang-tui recension of the Lao Tzu, where it is con- ceivable that the older of the two extant manuscripts, version A, may represent such a redaction. At the very least, given its greater antiquity, it is certainly the "an- cestral redaction" of this abbreviated lineage.46

During the process of surveying the extant direct tes- timony to a text that is at the heart of what Western

before the textual analysis is performed. See Dearing, Princi- ples, 15; Thorpe, 186ff. (where he defines "copy-text" as the "'base-text' that an editor chooses for his edition"); and Tanselle, 277-78, 300-5, and 315-19. The concept of "copy- text" received its definite expression in the famous article by Sir Walter Greg, "The Rationale for Copy-text," Studies in Bibliography 3 (1950-51): 19-36.

40 Aland and Aland, 6. 41 For which, see Thorpe, 116, and Tanselle, 309-11. It is

authoritative in deciding between textual variants. 42 OED., s.v.

43 In my research, the format of an edition and its particular arrangement of text and commentary are part of the category of

"formal determinants" of filiation, and the unique textual vari-

ants are part of the category of "textual determinants" of filia- tion. See Roth, Textual History, 199-222.

44 Roth, Textual History, 79-112. 45 Roth, Textual History, 69-71, 351-53. 46 Boltz, "Textual Criticism," 208-12, points to several ex-

amples of apparent conflation from the received textual tradi- tion in manuscript B, thus reinforcing the point established by

earlier scholars, citing taboo characters and calligraphic style,

that A is the older of the two. For a summary of the arguments

ROTH: Text and Edition in Early Chinese Philosophical Literature 225

textual scholars refer to as the recensio stage of textual criticism,47 it is necessary to identify all extant editions and to determine their filiation. For this I have devel- oped a procedure called "filiation analysis," which I have presented in detail elsewhere.48 The primary pur- pose of filiation analysis is to organize this extant testi- mony into lineages and determine which editions need to be consulted in establishing a new critical edition. The operant principle is that the textual scholar needs to locate the maximum number of possibly authentic textual variants present in the direct testimony, using the minimum number of editions. This is accomplished by first identifying the immediate ancestor and the immediate descendant of each extant edition and then organizing all editions into lineages. One then deter- mines which is the oldest edition in each lineage and uses it in the creation of the new critical edition. This is based on the assumption that editions derivative of this oldest edition are not needed, since all the possibly authentic textual variants are contained in their ances- tor, and on the further assumption that the later an edi- tion appears within a lineage, the greater is the number of textual variants not present in the original edition of that lineage but rather the result of emendation, confla- tion, poor editing, and so on. This principle of elimi- nating derivative witnesses from stemmatic analysis is also known in Western textual criticism and has been enunciated by both Paul Maas for ancient texts and James Thorpe for modern ones.49 The oldest extant edi- tion at the head of each lineage of editions is what I re- fer to as the "ancestral redaction."

Each of the six ancestral redactions of the conflated Kao/Hsu recension of the Huai-nan Tzu meets the definition of a redaction established above in that each "exhibits a unique format, a unique arrangement of

text and commentary, and certain characteristic textual variations." To use Dearing's definition, then, each rep- resents a unique "state" of the text, and each represents a further refinement of the foundational state of the text found in the conflated Kao/Hsu recension, an important "sub-state," if you will. In addition, all editions de- scended either directly or indirectly from an ancestral redaction exhibit all-or at least the most important- of the unique characteristics of their ancestor.

For example, all editions-with-commentary in the lineage of the Mao I-kuei Huai-nan Tzu redaction of 1580 exhibit the characteristic abridgement and re- arrangement of commentary found in their ancestor, as well as its unique method of providing phonetic glosses.50 In addition, all descendants of this ancestral redaction attribute the entire conflated commentary to Kao Yu and are arranged in twenty-one, not twenty- eight chapters. All descendants of the Tao-tsang redac- tion of 1445 contain the characteristic omission of twenty characters in the "Yuan-Tao" AR i chapter and the characteristic parablepsis (eyeskip) of ten charac- ters in the "Ching-shen" U 1' chapter,51 attribute the entire conflated commentary to Hsu Shen, and are ar- ranged in twenty-eight chapters, not twenty-one. More examples of the same kind could be adduced.

It is sometimes the case that common formal deter- minants of filiation transcend particular lineages of editions and point to origins beyond what can be de- termined from the filiation analysis of the extant testimony. These common characteristics indicate the presence of what I would like to call "redactional- types" and sometimes provide useful information in determining the filiation of the ancestral redactions. For the Huai-nan Tzu, there are two redactional-types: the 21-chapter organization found in the Northern Sung, Mao I-kuei, and Chuang K'uei-chi lineages, and the 28-chapter organization found in the Tao-tsang,

on dating the two manuscripts, see Robert Henricks, Lao Tzu: Te-Tao Ching (New York: Ballantine Books, 1989), xv.

47 See, for example, Maas, 2-10. The process of recensio involves not only surveying and sifting through the extant tex- tual testimony but also constructing a stemma codicum indi- cating the filiation of all the necessary witnesses.

48 H. D. Roth, "Filiation Analysis and the Textual Criticism of the Huai-nan Tzu," in Transactions of the International Conference of Orientalists in Japan 28 (1982): 60-81.

49 Maas, 2: "It will now be obvious that a witness is worth- less (worthless, that is, qua witness) when it depends exclu- sively on a surviving exemplar or on an exemplar which can be reconstructed without its help. A witness thus shown to be worthless must be eliminated (eliminatio codicum descrip- torum)"; Thorpe, 127: "The basic task of analysis ... is to eliminate derivative versions and thereby identify the version which comes nearest to conveying the author's intentions."

50 Roth, Textual History, 234-35, lists these characteristics: thirty to forty percent of the commentary is abridged when compared with the Northern Sung, Tao-tsang, and Liu Chi an- cestral redactions; there are additional comments not found elsewhere; brief comments are frequently gathered together and placed directly after the last graph commented upon; pho- netic glosses are presented in small print immediately beneath the appropriate graph, rather than later in the body of a more extensive semantic or informational comment.

51 Roth, Textual History, 149. The locations of these out- standing textual variants are Tao-tsang 2.7a3-6 and 12.12b9, respectively. Such outstanding variants are of particular im- portance in determining filiation. See, for example, Dearing, Principles, 5, and Maas, 4-5.

226 Journal of the American Oriental Society 113.2 (1993)

Liu Chi, and Chung-li ssu-tzu chi lineages. The general contents of each type are the same, they have simply been organized into a different number of chapters by dividing the longest seven chapters in half and consti- tuting each half as a distinct chapter. Never in the di- rect testimony do we have an instance of an edition of one type being based exclusively on one of the other type.

Such information is valuable in helping to deter- mine, for example, that the Chuang K'uei-chi redaction (twenty-one chapters) could not have been based exclusively on the Tao-tsang redaction (twenty-eight chapters) as Chuang seems to have claimed in his pref- ace.52 Where it points us beyond the extant testimony is to an interesting, but speculative, realm.

While the bibliographical listings of the Huai-nan Tzu never indicate a redactional type of twenty-eight chapters, the preface of Su Sung quotes an earlier (per- haps early T'ang) source which identifies the division of several chapters into two parts (shang i and hsia 1) as a distinguishing characteristic of the Kao Yu re- cension.53 Such a division is now found in seven chap- ters of the 28-chapter redaction-type. The division of these chapters, which are among the longest in the text and which all contain the Kao Yu commentary, imbed- ded in which are Hsu Shen's comments, could have initially occurred when the unknown fourth-century re- dactor created the conflated Kao/Hsu recension and thereby increased the length of these chapters.54 These divisions would therefore not actually be characteristic of the independent Kao Yu recension, but rather of the conflated Kao/Hsu recension that, at least by the early T'ang, passed under the name of Kao alone. Therefore the 28-chapter redactional-type could have its ultimate origin in this conflated recension, while the 21-chapter redactional-type might have originated in the indepen- dent Hsu Shen recension. Only a careful analysis of the indirect testimony to the Huai-nan Tzu holds the promise of clarifying this intriguing possibility.

Returning to the analysis of the direct tradition, once we have established filiation diagrams for each of the

extant lineages of editions, and identified their ances- tral redactions, we now must collate these ancestral witnesses and analyze their textual variants. The rules and procedures for so doing have been debated by Western textual critics during the past century and a half, but the inner logic has remained relatively consis- tent. The result is the construction of what is techni- cally called a stemma codicum, which enables us to decide logically among conflicting variants, based upon the position of their witnesses in the stemma, or, in other words, based upon their filiation. The two out- standing examples of the application of these methods to Chinese philosophical texts are Thompson's work on the Shen Tzu fragments, based upon the methodology of Dearing, and Boltz's work on the Lao Tzu, based upon the methodology of Maas.55 Following Thomp- son, my own work has relied upon Dearing's methodol- ogy of "textual analysis," but as I understand it, the inner logic of both methods is essentially the same.

In my research on the Huai-nan Tzu, I used Dear- ing's "textual analysis" to clarify the filiation of the six ancestral redactions, although this kind of stemmatic analysis is more commonly used to establish the read- ings in the hypothetical ancestor of all the extant edi- tions of a text. Both uses are warranted and important, and do not indicate a circularity of reasoning. Indeed, as Tanselle aptly states:

Since the analysis of textual relationships involves judgement at some point, the examination of variants for that purpose is intimately linked with the consider- ation of variants for emendation. It is not arguing in a circle to decide (having used subjective judgement to some extent) on a particular tree as representing the re- lationship among the texts [i.e., editions-HR], and then to cite that relationship as one factor in the choice

among variant readings; the latter is simply a concomi- tant of the former, for the process of evaluation em- ployed in working out the relationship between the two

readings overlaps that used in making a choice between them.56

In the final stage of this process, which most West- ern textual scholars call emendatio, but which Maas prefers to call examinatio, we must decide among those variants that cannot be established through stemmatic analysis. This is an often laborious and painstaking

52 See Roth, Textual History, 277-83, for a discussion of Chuang's implicit claim and the conclusion that Chuang's re- daction is taken directly from his mentor Ch'ien Tien's Si!9 hand-collated exemplar of the Mao K'un X 1 edition from the Mao I-kuei lineage, onto which Ch'ien has written down differ- ences with the Tao-tsang redaction.

53 Roth, Textual History, 351. 54 Roth, Textual History, 44-45, 47-49, for the discovery

of Hsu Shen comments embedded in the extant Kao Yu com- mentary by T'ao Fang-ch'i.

55 Thompson, The Shen Tzu Fragments; Boltz, "Textual

Criticism and the Ma-wang-tui Lao Tzu." 56 Tanselle, 317.

ROTH: Text and Edition in Early Chinese Philosophical Literature 227

procedure and entails the use of both the full range of philological tools (etymology and historical phonology being, perhaps, the most important), and finally the careful application of criteria based upon the editor's sense of meaning. The anticipated result will be the construction of the hypothetical archetype of all the ex- tant testimony to the text, using the minimum number of decisions based on the editor's sense of meaning. This archetype is as close as we can come to the au- thor's original intent, the ultimate goal of textual criti- cism.57 Hence, despite Dearing's attempts to exclude textual history from textual criticism (or, to be more exact, "bibliography" from "textual analysis"), there is an intimate connection between them.

This intimate connection is generally acknowledged by Western scholars as well, although the heated de- bate on the parameters of-and relationships be- tween-"bibliography" and "textual criticism" ably summarized by Thorpe sometimes tends to obscure this.58 Rather than jumping into this Western debate, I prefer to attempt to stay within Chinese models in cir- cumscribing bibliography to the study of the various forms of bibliographical records and the study of the circumstances and techniques of book production and collecting (t'u-shu pan-pen hsueh N 1 W RR* , mu-lu hsueh R i, and shu-lin W *), and to subsume it under the category of "textual history."59 I also include in this category the study of textual transmission, tex- tual stratification and authenticity, and the methodol- ogy I have called filiation analysis. I tend to think of the term "textual criticism" in a more limited fashion than Western scholars such as Maas, to include only

the specific procedures for determining the readings in the critical edition, and not the preparatory procedures I have discussed under the heading of "textual his- tory." I include in the category of "textual criticism" both the relatively more "objective" procedures, such as stemmatic analysis and the more "subjective" ones, such as deciding between variants when the stemmatic analysis is equivocal, while of course recognizing that these are relative terms and that critical judgment must be used in both phases.60 What Dearing calls "textual analysis" and others call "stemmatics" is a technique that can be used for both textual history-more specifi- cally, for filiation analysis-and for textual criticism. In short, what I call "textual history" belongs to what Maas calls recensio and what I call "textual criticism" belongs to what Maas calls examinatio (and others call emendatio). While reaching a consensus on the mean- ing of these terms is desirable, it is perhaps not as at- tainable a goal as clearly defining them in one's own work and using them consistently.

To sum up, a text is the unique complex and expres- sion of ideas of an author or authors, an edition is a distinct record containing a unique state of a text, an exemplar is a copy of a printed edition (or the actual manuscript of a handwritten edition), a recension is a foundational version or state of a text, a redaction may be either the first record of a recension or the oldest record of a unique "sub-state" of this recension, the ancestral redaction is the oldest extant edition in a par- ticular lineage of editions and as such represents the oldest extant witness to the unique sub-state of a recen- sion contained in all the editions of its lineage, and the "received text" (textus receptus) is the extant recension or recensions of a text. Due to the specific nature of my textual sources I am not certain how generalizable my definitions are. Thus I set them forth not as a definitive statement, but to initiate a discussion that I hope will lead to a better understanding of the nature of textual history and textual criticism and to a clearer grasp of the common problems we all confront in dealing with pre-modern Chinese texts.

57 This ultimate goal of textual criticism is by no means uni- versally shared. See, for example, Tanselle's excellent sum- mary of relevant debate and his own ideas on this subject in "The Editorial Problem of Final Authorial Intention," in Tanselle, Textual Criticism and Scholarly Editing, 27-71.

58 See the chapter entitled "The Province of Textual Criti- cism," Thorpe, 80-114.

59 Three outstanding twentieth-century Chinese biblio- graphical studies are: Yeh Te-hui i i 3, Shu-lin ch'ing- hua : 4 M ffi (Ch'ang-sha, 1920); Ch'u Wan-li E M T and Ch'ang Pi-te RE Mid, T'u-shu pan-pen hsueh yao-lueh Id a 0 * * Mo, 2nd ed. (Taipei: Chung-hua wen-hua ch'u-pan- she, 1955); and Hsu Shih-ying RF tftf9, Chung-kuo mu-lu hsueh shih P W U 1 5 - , 4th ed. (Taipei: Chung-hua wen- hua ch'u-pan-she, 1974).

60 I use these terms advisedly to reflect the opinions of the scholars such as Maas and Dearing who work on stemmatic analysis, while aware of the criticism of others such as Thorpe and Tanselle that subjective "critical" judgments are also in- volved on this genealogical side. See, e.g., Thorpe, 116, and Tanselle, 278-80.