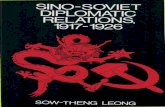

SINO-RUSSIAN POLICIES IN THE CENTRE AND PERIPHERY

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of SINO-RUSSIAN POLICIES IN THE CENTRE AND PERIPHERY

SINO-RUSSIAN POLICIES IN THE CENTRE

AND PERIPHERY: A COMPARATIVE

ANALYSIS

Ph.D Thesis

Research Scholar

SAMRA SARFRAZ KHAN

DEPARTMENT OF GENERAL HISTORY

UNIVERSITY OF KARACHI

2017

SINO-RUSSIAN POLICIES IN THE CENTRE

AND PERIPHERY: A COMPARATIVE

ANALYSIS

A Dissertation Submitted

By

SAMRA SARFRAZ KHAN

For

The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in General History

Research Supervisor

PROF. DR. UZMA SHUJAAT

DEPARTMENT OF GENERAL HISTORY

UNIVERSITY OF KARACHI

2017

(iii)

TO WHOM IT MAY CONCERN

It is certified that this thesis entitled “SINO-RUSSIAN POLICIES IN THE CENTRE

AND PERIPHERY: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS” submitted to BASR,

University of Karachi by Ms Samra Sarfraz Khan, has been completed under my

supervision and fulfills all requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of

Philosophy in General History.

Prof Dr. Uzma Shujaat

Research Supervisor

Area Study Centre for Europe

University of Karachi

(iv)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

First and foremost, I would like to thank Allah Almighty for giving me the courage and

determination to go successfully through my PhD thesis.

I would like to express my profound appreciation to my supervisor, Prof. Dr. Uzma

Shujaat, for being an excellent advisor and friend towards me. Her knowledge,

appreciation and guidance provided me with ample opportunities to grow as a researcher.

I would also like to thank my colleagues in the Department of History (Gen.) for their

encouragement towards achieving my goal. A special word of gratitude is due for Prof.

Dr. S.M. Taha for his unprecedented support throughout the period of my research work.

His timely help and supervision always saved my day.

I would also like to extend a very special thanks to my parents Mrs. and Lieutenant

Colonel Raja Sarfraz Khan, family and friends whose prayers helped me to sustain thus

far.

At the end, I would like to express my most sincere gratitude to my husband, Squadron

Leader Omair uddin Baig. Words cannot express the magnitude of having his

companionship in a continual cycle of tiring days and sleepless nights that continued

through these years of research, and of having his support in times when there was no one

else to answer my questions.

Samra Sarfraz Khan

(vi)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CERTIFICATE iii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iv

DEDICATION v

LIST OF FIGURES ix

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS xii

ABSTRACT (English) xiv

ABSTRACT (Urdu) xvii

INTRODUCTION 1

Chapter 1: A BRIEF INTRODUCTION TO THE PERIPHERIES OF

RUSSIA AND CHINA

28

1.1 Problems on the Roof: China’s Presence in Tibet 29

1.2 Xinjiang: China’s Muslim Frontier 34

1.3 Problems Across the Strait: China’s History in Taiwan 40

1.4 The Fragrant Harbor: China In Hong Kong 45

1.5 Problems in the Russian Periphery 53

1.6 Chechens Identity & the Ingush Dilemma 59

1.7 Dagestani Fervor 68

1.8 Kabardino-Balkaria 78

Chapter 2: CHINA AND RUSSIA IN THE POST COLD WAR ERA 90

2.1 Chinese Periphery after 1991 90

2.2 The Last Years of British Hong Kong 98

(vii)

2.3 Uyghurs and Hans in the 1990s 104

2.4 Cross-Strait Relations: China and Taiwan During the 1990s 112

2.5 The Russian Periphery (1991-2000) 117

2.6 Russia and Chechnya Since 1991 119

2.6.1 The Second Caucasus War: Russian Invasion of Chechnya

(1994-1996)

129

2.6.2 The Second Chechen War 132

2.7 The Soviet Elite in Dagestan 138

2.7.1 A tale of two brothers: The Rise and Fall of Nadir and

Magomed Khachialev

139

2.8 Events of Insurgency in KBR 145

2.9 The Problems in Ingushetia 152

Chapter 3: WINDS OF CHANGE: THE IMPORTANCE OF SINO-

RUSSIAN TIES IN A CHANGING WORLD

159

3.1 Disturbed Peripheries of Russia and China 159

3.2 The Georgian Dilemma 168

3.3 Russia’s Return in Great Power Politics 175

3.4 The Surprise in Ingushetia and KBR 178

3.5 China’s Reign of Terror 182

3.6 Change of Tides in the Strait 186

3.7 Chains, Pearls and Road: A Chinese Trilogy 191

3.8 Sino-Russian Ties in the Post-9/11 World 199

(viii)

Chapter 4: CHINESE AND RUSSIAN COUNTER POLICIES IN THE

CONTEXT OF DISTURBED PERIPHERIES

212

4.1 Chinese Periphery And The New Geo-Political Environment 213

4.2 Russia’s Volatile Frontiers 238

4.2.1 From Ethno-Nationalism to Ethno-Secessionism 248

4.3 Sino-Russian Ties in the New Political Order 268

Chapter 5: THE STATE AND THE GOD: A HISTORY OF RELIGION

IN RUSSIA AND CHINA

272

5.1 Religion in China 272

5.2 Government And Religion: A Reactive Process 282

5.3 State and Religion In Russia 286

5.4 From Lenin to Mao: The Suppression of Religion In Russia

And China

300

5.5 The Religious Characteristic of Ethno-National Conflict In

China And Russia

303

5.6 Aides of Control: Media And Censorship in China And Russia 311

5.7 Remarks on Chinese And Russian Control on Media and

Religion

321

Chapter 6: EMERGING DYNAMICS OF SINO-RUSSIAN

PARTNERSHIP IN THE PERIPHERY: CHINA IN THE

RUSSIAN FAR EAST

323

6.1 History of the Russian Far East 324

6.2 The Soviet Years And Afterwards 330

6.3 Changing Dynamics of Russian Foreign Policy 335

6.4 A Brief Outlook of the RFE 341

(ix)

6.5 Osvoenie: Russia’s Northern Policy 349

6.6 A Brief History of the North 352

6.7 Chinese Involvement In The RFE 367

6.8 Why Russia needs China 375

CONCLUSION 377

RECOMMENDATIONS 402

BIBLIOGRAPHY 410

(x)

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure i Map of Dagestan 11

Figure ii Map of the Caucasus region 12

Figure 1.1 Map showing Xinjiang and its border territories. 34

Figure 1.2 Average annual economic growth of Hong Kong as indicated by

number of ships.

53

Figure 1.3 Average annual increase in Hong Kong’s population from 1841 to

1895.

53

Figure 1.4 Map of North Caucasus 55

Figure 1.5 Statistical illustration of the number of secular and Islamic

schools between 1904 and 1917

75

Figure 1.6 Russian military expansion in the North Caucasus (18th

and 19th

centuries)

75

Figure 1.7 Ethnic distribution in Kabardino-Balkaria 79

Figure 2.1 Hong Kong’s GDP Growth by Year 103

Figure 2.2 Private sector Producing units and Employed Persons(by district)

in Xinjiang, 2004

107

Figure 2.3 Map of Chechnya 137

Figure 2.4 Chronology of terrorist events in Russia (1999-2011) 157

Figure 3.1 Map of Russia showing the northwest Caucasus 166

Figure 3.2 China and Taiwan’s Exports 189

Figure 3.3 China and Taiwan’s Imports 190

(xi)

Figure 3.4 Taiwan’s Investment in China 190

Figure 3.5 Map showing the location of First and Second Island Chain 193

Figure 3.6 String of Pearls 194

Figure 3.7 Sino-Russian trade 205

Figure 3.8 Chinese exports to Russia 207

Figure 3.9 Russian Exports to China 207

Figure 3.10 Map of UGSS of Russia 208

Figure 3.11 Map of Sila Sibiri 208

Figure 3.12 China’s oil imports from Russia and KSA 209

Figure 4.1 Population and average income in Urumqi by ethnicity 218

Figure 4.2 Inter-provincial migration patterns of Han population 219

Figure 4.3 Map showing the Nine Dotted Line and the location of some of

the disputed islands in the South China Sea

234

Figure 4.4 Map showing the geographical location of Greater Caucasus. 240

Figure 4.5 Map showing shipment route for BTC pipeline 243

Figure 4.6 Blue Stream gas pipeline and layout for South Stream Gas

Pipeline.

244

Figure 4.7 Gas supplies via the Blue Stream gas pipeline 244

Figure 4.8 Terrorist attacks in Russia between 1st January 1992 and 31

st

December 2011

257

Figure 4.9 Statistics of the Victims in North Caucasus (2013) 261

Figure 4.10 Statistics of target types in terrorist activities (2013) 262

(xii)

Figure 5.1 Social hierarchy under the Mongols 279

Figure 5.2 Religious groups in Russia (1991-2008) 303

Figure 5.3 Top-10 Media Markets 315

Figure 5.4 Top TV Channels Audience Reach, 2012-2013 315

Figure 5.5 Top Weeklies in terms of Audience Reach (All-Russia) 316

Figure 5.6 Structural Change of the Russian Media Market 316

Figure 5.7 Daily and Non-Daily Newspapers Circulation Figures in China 320

Figure 5.8 Top Ten Daily Newspapers as of 2000 321

Figure 6.1 Map of Russia including the Russian Far East 325

Figure 6.2 Map of Russian expansion (1553-1894) 329

Figure 6.3 Far Eastern Republic in 1922 330

Figure 6.4 East Siberian-Pacific Ocean Pipeline 344

Figure 6.5 Map of Russia’s north 351

Figure 6.6 Northeast Passage 359

Figure 6.7 Northern Sea Route 360

Figure 6.8 Sailing distances between Asia and Europe throughthe Nep 363

Figure 6.9 Russia’s key trading partners in Asia ($ billion) 368

Figure 6.10 Share of China, Japan and South Korea in the RFEFD’s Trade 370

Figure 6.11 Chinese Investments in the REF-Transbaikal by Province (2011-

2012) In Millions of Dollars

371

Figure 6.12 Strategic Location of Zarubino Port 372

(xiii)

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

ETIM East Turkestan Independence Movement

XUAR Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region

TAR Tibet Autonomous Region

RFE Russian Far East

PRC People’s Republic of China

ROC Republic of China

SAR Special Administrative Region

CCP Chinese Communist Party

USSR Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

BLDC Basic Law Drafting Committee

FDI Foreign Direct Investment

SEF Strait Exchange Foundation

ARATS Association for Relations across the Taiwan Strait

KBR Kabardino-Balkaria

NCCP National Congress of Chechen People

RSFSR Russian Soviet Federal Socialist Republic

ASSR Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic

AO Autonomous Oblast

NCBP National Congress of Balkar People

SCO Shanghai Cooperation Organization

CNPC China National Petroleum Corporation

CIS Commonwealth of Independent States

(xiv)

OSCE Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe

ETLO East Turkestan Liberation Organization

SLOC Sea Lanes of Communication

COSCO Chinese Ocean Shipping Company

B&R Belt and Road / One Belt, One Road Initiative

CRCC China Railway Construction Corporation

CSSTA Cross-Strait Service Trade Agreement

SCS South China Sea

SKFO North Caucasus Federal District

SARA State Administration for religious Affairs

KMT Kuomintang

EEU Eurasian Economic Union

RFEFD Russian Far Eastern Federal District

NSR Northern Sea Route

NEP Northeast Passage

(xv)

ABSTRACT

The thesis entitled “Sino-Russian Policies in the Centre and Periphery: A Comparative

Analysis”, shall focus on different aspects of the peripheries of Russia and China. For a

thorough understanding, a selective number of areas have been chosen from the two

states’ peripheries. The regions selected for the study of Russian periphery lie in the

northwest Caucasus, namely; Dagestan, Chechnya, Ingushetia and Kabardino-Balkaria.

In the case of China, Tibet Autonomous Region, Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region,

Hong Kong and Taiwan will be discussed in detail.

The significance of the above mentioned territories lie in the unique nature of their

relationship with their respective centres. The policies devised by the centre, which lie at

notable distance from these regions, are often regarded with skepticism and doubt. The

selected Russian peripheries of northwest Caucasus, Tibet and Xinjiang, which

experience a rather uneasy relation with Moscow and Beijing respectively, also carry

huge significance for the national governments, for these regions are immensely rich in

natural resources including oil and gas. Moreover, these regions also serve as

hydrocarbon conduits, thus adding to their significance. In addition to this, the above

named territories lie in such a geographical arrangement that they become extremely

important in the respective national policy framework of the two countries. Although,

both Russia and China have colossal opportunities in these regions but the perturbed state

of affairs present both governments with immense challenges to conduct their policies in

the best interest of the country.

(xvi)

While Hong Kong’s relations with Beijing are smooth and comfortable, but in the recent

past, the centre’s attempts to exercise CCP’s principles in the island territory have caused

friction in the relations between the island territory and the mainland. As for the case of

Taiwan, historical dispute between the two governments has come between, time and

again, in smooth bilateral relations across the strait, whereas comfortable relations

between the two are especially important for China’s ever growing economy.

Moreover, both China and Russia, which share a communist past, also share a similar

attitude in handling matters related to expression and religion in the above mentioned

peripheries inhabited by ethnic minorities. In addition, China and Russia, lying at close

proximity with each other share common interests and apprehensions in the context of

regional and trans-regional politics. These factors have brought the two countries together

in political and economic spheres. This thesis also discusses the potential of Sino-Russian

partnership in the region in view of regional geo-political milieu and of countering non-

regional hegemony in the region.

This research focuses on the policies of Russia and China in these disturbed peripheries.

It brings to light how measures designed in the centre for the management of these

peripheries are implemented in these regions of Russia and China and why such policies

have often failed in bringing about the desired results. It also highlights the areas of

trouble in Beijing’s and Moscow’s political framework and the policies designed by the

respective centres to counter them, as well as the commonalities and differences in these

policies. As both Russia and China occupy a significant position in world politics, it is

important to understand the problems faced by their leadership within the borders and

(xvii)

also in their individual peripheries, as these challenges also have serious effects on the

two countries’ global reputation.

By using historical references and quantitative research methods, the research is a sincere

endeavor at bringing out a clearer and unbiased picture of the challenges and possible

solutions to the problems in these two similar-to-an-extent societies.

(1)

INTRODUCTION

Both Russia and China possess a noteworthy place in world politics. However, the

economic and political might of the two giants is not without predicaments. The two

powers face serious anti-state sentiments within their borders. Majority of the research

done these days addresses the economic policies of China and Russia and their

relationship with the west. A lack of research focused on the comparative policy

challenges at home, in the periphery of Beijing and Moscow along with strategic

evolution of Sino-Russian ties must be ratified by conducting research on such and

relevant issues.

The research entitled, “A Comparative Study of the Chinese and Russian Policies in the

Centre and in the Periphery: Challenges and Opportunities” shall focus on the gray areas

involving the state politics of Russia and China. Believing that these problems cast a

serious threat to the international standing of the two aspiring world powers in the

international community, the research shall be an attempt at bringing out a clearer and

unbiased picture of the challenges and the possible solutions to the problems in these two

similar-to-an-extent societies. The research focuses on the similarities and contrasts in the

regional policies of Russia and China. It shall also highlight the uneasy factors in

Beijing’s and Moscow’s political framework and their respective policies to counter

them.

As deciding regional actors and as aspiring global powers, the international standing of

both Russia and China in world politics remains beyond question. However, it is

important to understand that both the states face serious issues within the borders and

(2)

peripheries. As these challenges have serious effects on the two countries’ global

reputation, consequently, these problems also bring serious alterations in their respective

foreign as well as home policies. Certain factors bring a degree of similarity in the

domestic situation of the two countries. Both the states face separatist movements within

their borders. Moreover, religious element is very evident in these movements. Neither of

the two governments is ready to surrender to the local insurgents for reasons national and

otherwise. Interestingly enough, the separatist movements in Russia and China are being

experienced in regions which have huge geo-strategic, geo-political and geo-economic

significance for their respective regions in particular and for the international community

in general. Another common factor in Russian and Chinese politics is religion. In both the

countries religion; though a private matter of the citizens, is becoming more of an issue

for national politics. For example, religion is a corner stone in the separatist movement in

Tibet and Xinjiang in China and in Chechnya and Dagestan in Russia. Moreover, many

people in Russia are rapidly becoming weary of the ‘forced secularization’ and are

raising criticism against their government for the same. Another common factor is the

role and position of media in Chinese and Russian societies. The two governments follow

the policy of press and television censorship and government authorities largely control

this most convenient means of communication. The censorship also invites criticism from

national as well as international communities. The research, therefore, also looks into the

control of media and religion, and the expected results on the states’ performances.

China, an economic giant, is the topic of most of the researches done these days. But in

many of the researches the economic rise and the economic policies of China are more

bring attended to. The same gap can be felt in researches conducted on Russia. As a

(3)

result, the domestic challenges confronting Beijing and Moscow, a question of profound

importance, seems to be neglected. This research shall fill the vacuum created by the lack

of research on such topics. The research also aims to highlight the domestic policies of

Russia. A former super power, Russia is aspiring to take the world stage yet again by the

next few years. For this purpose, Moscow has formed strategic partnership with countries

other than the traditional actors in world politics. An example in this regard is of the

economic alliance in the form of BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India and China). The research

will also calculate the possible outcomes of such other strategic partnerships between

China and Russia and their probable effects on the regional as well as international

political order.

During the twentieth century, Russia and China followed the policy of secularization of

their respective communities for the sake of scientific and technological development.

While Marx considered religion as opium for men, Lenin saw it as a “cheap way” of

justifying human existence. However, in the course of time, there were many who

abandoned the very notion both overtly and covertly. Over the period of time it became

difficult for the Russian regimes to continue their crackdown on believers. Although

believers of all faiths were subjected to secularization but a counter retaliation was more

profoundly experienced from the Muslim section of the population. One of the

underlying causes for this phenomenon is the high poverty rate in some of the Muslim

majority areas, a growing Muslim demography and a global deepening of the various

militant networks. The gap between rich and poor regions is more than just obvious in

Russia. As a matter of fact, most of Russia’s poorest regions happen to be those

populated by Muslims. As a result of Soviet policies of confining industrial surplus to the

(4)

Slavic inhabited areas of the country, all of the titular Muslim republics are located in the

economically poorest districts of Russia, that is, the Southern districts and the Volga

Federal Districts. The economy of the North Caucasus’s Muslim Republics is also among

the worst in Russia. (Things are comparatively better in Bashkortostan, Tatarstan and

some Volga republics).

As for China, the early decades of the twentieth century presented two inter-related

questions before Chinese nationalists; should the Chinese nation be an ethnic entity of the

Han people in the eastern provinces, or should it rather be a political entity including the

western and eastern areas, inhabited by non-Han population, which encompassed the

sovereignty of the Qing Empire. Since 1949, many changes have taken place in the socio-

economic and political spheres of the Chinese society. Reforms in the economic sector

along with the opening of trade have given many new opportunities to the ethnic groups

or minzu in China. However, many issues including the unequal exploitation of resources,

unequal development and demographic problems continue to create challenges for the

central government. The Chinese leadership, therefore, has to face conflicting reactions

from Tibet, Mongolia and Xinjiang.

In a similar context, Taiwan and Hong Kong, in addition to Tibet and Xinjiang pose huge

challenges for Beijing. While One Country Two Systems Formula forms the system of

government in Hong Kong, the public sentiments in Taiwan are highly critical of any

such formula being introduced for their region against the much aspiring wishes of the

PRC. Whereas in Tibet, neither the government nor the masses are in favor of converting

the region into a Special Administrative Region (SAR), on the model of Hong Kong and

(5)

Macau. A considerable section of the Tibetan leadership has been quite vocal in the

demand for autonomy during the recent decades. In addition to this, Xinjiang is the most

imperative question before Beijing at the moment. A Muslim majority province, Xinjiang

is a gateway into oil rich Central Asia, which China cannot afford to lose at any cost. The

significance of the province becomes even greater in view of the New Great Game, US’s

designs in Afghanistan and the insurgency in Pakistan which shares a common border

with the Chinese province of Xinjiang.

The significance of the topic is further substantiated by the fact that China, an economic

giant of Asia, is fast taking the world stage with its strong market force, followed by

Russia which is set on the path to attain its long aspired status of retaking the super power

image across the globe. Other than ethnic issues in the Russian and Chinese peripheries,

Sino-Russian partnership is fast becoming an inevitable reality of modern world politics.

The partnership between Russia and China rests purely on economic grounds.

Nevertheless, both the states have had their share of troublesome phases of socio-

economic struggle that slowly but steadily evolved into the economic force that is today’s

Russia and China. It is for this reason that a comprehensive study be made of the various

phases in the development of the two states since.

China and Russia in a comparative mode

Throughout history, as per ethnic tensions, both Chinese and Russian regimes have tasted

more or less an equal share of utmost challenging nature. From the grassless steppes of

Central Asia to the northwestern Caucasus and from the mountainous terrains of East

Turkestan to the casinos of Macao, both Moscow and Beijing have passed turbulent

(6)

passages in history’s timeline. Ironically enough, Russo-Chinese relations itself have

been of a rather complicated nature. The two neighboring powers experienced a tide of

changing relations, beginning from the thirteenth century up to the present time.

However, many a times, it also did happen that the two states were kept from not only

going global in their international relations but also from coming closer to each other in

face of the daunting tasks to be settled in and along their borders.

The first physical contacts between China and Russia may be traced back to the twelfth

and thirteenth centuries, for it was only then that the two civilizations were brought into a

formidable contact by the Mongol conquest of China and Russia. As the Christian church

faced a split in 1054 into the Western or the Roman Catholic Church and the Eastern or

the Greek Orthodox Church, an intense feeling of isolation and mistrust soon followed

that was to psychologically and practically keep the two halves of Europe at bay. As a

matter of fact, other than some accessional feuds along the Baltic coast, the Russians

were left largely to themselves as the northern and eastern hinterlands for the most part

remained deserted and the Byzantium Empire in the south was now convulsing in the

aftermath of the crusades and the subsequent decline of the imperial power in

Constantinople. Taking advantage of the Chinese and Russian weaknesses in the twelfth

and thirteenth century, Mongols conquered the two adjacent territories in 1234 and 1240

respectively. Stretching from Hungary to southern China, Mongols established a single

formidable empire signifying the spirit of Pax Mongolica.1 Thus were also started the

first known historical contacts between Russians and Chinese as the court of the Great

Khan housed both Chinese and Russian elements both in person and in persona. The

1. R.K.I Quested, Sino-Russia Relations: A Short History, (New York: Routledge, 1984), p.21

(7)

installment of Ming Dynasty in China in 1368 reshaped Chinese politics whereby; links

with foreign governments were restricted to Japan, Korea, Mongolia and Southeast Asia.

Conversely, contact with Russia became a memory of the bygone days.

In Russia, the Mongol Yoke continued from 1240 to 1478 during which time the

Russians were diverted from western to an eastern or Eurasian mode of development.

From the time of its establishment in the mid twelfth century, Muscovy remained the

capital seat of Russian government. When Michael Romanov became the Czar in 1584,

he continued the process of Russian expansion simultaneously while enriching Russian

trade experiences with England and Central Asian states.2 Though trade with England

was started during the times of Ivan the Terrible, the Romanovs took special interest in

the world around them. In 1615 and 1616 envoys were sent to gather information about

the Chinese Empire and its customs. Their reports mentioned China as a “powerful,

wealthy land, rich in satins, velvets, silks, gold, silver and grains, and quite accessible to

Cossack expeditions.”3 These reports excited the Czar to send an investigation mission to

China which thus set the stage for Russian advance into the highly populated Chinese

empire of the seventeenth century.

The mission returned from Peking with not much success. For the next few decades, the

political upheavals in Central Asia, North China and Mongolia along with the challenges

before the Russian government on its western frontiers kept Muscovy from venturing into

Ming China. It was only in 1643 that the Russians reached Amur River for the first time.

This expedition was principally for the quest for more tribes to be brought under the

2. Ibid, pp.22-23, 25 3. R.K.I Quested, Sino-Russia Relations: A Short History, Op.Cit., pp.25-27

(8)

Russian ‘fur tribute’ system. Suffering a harsh treatment at the hands of the Russians, the

locals reported Russian activities to the Manchus who had established their power in

Peking in 1644. This state of affairs continued for the next few years until in 1649 when

the local tribes once again complained the Manchus of the Russian peril and demanded

the former of either providing defense against the Russians or to allow the local populace

to accept Russian suzerainty so as to avoid the payment of tribute. This led to the

determining of the final decision of Manchus; of ridding themselves of the Russian threat

at their borders. Thus, in 1652 the Russo-Chinese battle was fought with the result going

in the favor of Russians. Almost simultaneous to these events were local rebellions and

declining health conditions in Muscovy; leading to a profound dilapidation in Russia’s

European trade. Thereafter, Czar Aleksei diverted Russian trade towards Asia.

Consequently, missions were dispatched to India in 1651 and to China in 1652.4

As for China, having made vassal states in Korea and Mongolia, the Manchus treated

foreigners with arrogant contempt. The Russian embassy sent under the headship of

Fedor Isakovich Baikov in 1653 for the purpose of settling border dispute and to establish

bilateral trade was also treated thus. As Baikov refused to bow to the Emperor, he was

forced to leave without meeting the imperial head. Though the embassy failed in its

purpose, it nevertheless provided a foundation for subsequent Russian diplomatic

attempts with China. The second Russian embassy to China under Perfil’ev left for China

in 1658 with the Russian promise of chalking out a peaceful solution to the cross-border

problems across the Amur River and of keeping the territory sans Russian soldiers.

Though received hospitably, no agreement could be achieved on Amur conflict. As a

4. Ibid, pp.29-30

(9)

matter of fact, the conflict at Amur continued on the previous note. Nonetheless, trade

between the two sides continued unaffected and the Russian town of Nerchinsk and the

Chinese town of Naun gained international reputation for their brisk trading activities. In

the same light, Russian private and public trade caravans also frequently visited Peking.

The furthering of trade activities required the settlement of the most pertinent issues

between the two regimes; namely the border disputes. Therefore, in 1675, Nikolai

Spafarii left for Peking where he reached in 1676. This embassy, however, was also

treated with disrespect by the Manchus and the Czar’s demands to Emperor Kang Hsi for

perpetual ‘friendship, a Chinese embassy in Moscow, and the permission for Chinese

craftsmen to travel to Russia’ went unanswered.5 It was finally in 1689 that the Sino-

Chinese conflict across the Amur region was resolved by means of the Treaty of

Nerchinsk; the first formal treaty between the two empires and the groundwork for future

bilateral diplomatic relations. The treaty put an end to the conflict started as an outcome

of Cossack encroachments into the region for fur trade where the people formerly paid

tribute to the Chinese Emperor in Peking. Russians withdrew their fortifications from

Amur. However, it was trade that soon became the momentous factor in the outcome of

the treaty. The bilateral trade was thereafter conducted not only by Siberians and Chinese

but also by “Bukharans”6 who soon became important players in Russian trade and

commerce.7 This, in turn led to the making of a multiethnic blend along the Russian

borders. Through the mid-eighteenth to the nineteenth centuries, bilateral relations

5. Mikhail Losifovich Sladovskii, History of Economic Relations Between Russia and China, pp.9-12 6. A term used for Central Asians, Persians, Turkish, Greek and Indian merchants. 7. Penny M. Sonnenburg, Colonialism: An International Social, Cultural and Political Encyclopedia, vol.1, (California:

ABC-CLIO, 2003), p.412

(10)

between Russia and China continued to develop. The Treaty of Kyakhta signed between

the two sides in 1727 had also further refined bilateral trade.8

Other then economic and border issues, Russia and China have had their share of ethnic

unrest ensuing from the territorial expansion along their borders. This was also one of the

contributing factors which kept the two empires from a regular involvement with other

nations. At a time when most of the western nations were subduing tribes and

governments of foreign realms, both Russia and China faced the additional task; and a

somewhat premature phenomenon for the age; of settling ethnic unrest in and along their

borders. Here can be noted the first hint of similarity in the states’ affairs, which

henceforth requires a comprehensive analysis of transpiring events that so brought the

two powers at this juncture of history.

For both China and Russia, the episodic expansions have been of a rather hereditary

character, passing down from one dynasty to the next, with the periodic addition of

religious, political and socio-economic problems associated with the natural disposition

of these territories. In contrast with the imperial history of other nations, China and

Russia had little choice but to assert and preserve their sovereign rights in the conquered

areas. While the acquisition of Africa or Asia served economic purposes to the colonial

masters of the early modern times, the conquerors could still very well survive without

the assistance coming from these quarters, provided an equivalent source was to be found

in a new territory, either far off or near at hand. On the other hand, when Russians

8. The Treaty of Kyakhta defined the Russo-Chinese border along the Kyakhta River in Russia and the mountain of

Orogoita on the Chinese side. It thus settled the pending border dispute, leading to a new era of political stability in the

Far East. In addition to settling the border dispute, the Treaty also settled trade concerns by determining bilateral trade

terms including the right to conduct duty free barter in Nerchinsk and Kyakhta, and permitting Russian trade caravans’

access to Beijing.

(11)

annexed Dagestan in 1813, the strategic importance of the Republic was what made the

Czar to keep the Russian forces at arms with Imam Shamil for twenty five years of sheer

military expense, which by this time was a Russian zone of influence in Russo-Persian

relations. Furthermore, under the terms of the Treaty of St. Petersburg of 1723 between

Russia and Persia, while accepting Russian suzerainty in the Caspian Sea, the latter also

ceded Baku, Mazandaran, Gilan and Astarabad to Russia. Therefore, clearly enough,

when Russians advanced into Dagestan in the early years of the nineteenth century, it was

only after a thorough deliberation of the benefits that the Republic could offer.

Furthermore, Mazandaran and Gilan gave Russia easy access into northern Persia, and

Dagestan, in turn provided a route to these two provinces. The inspiration of all these

goals forced the Russians to enter, fight and finally subdue the Dagestanis to accepting

Russian suzerainty.

i: Map of Dagestan

(12)

ii: Map of the Caucasus region.

Since the nineteenth century, Russians have fought a highly ambitious and expensive war

in the Republic. Russian designs have had serious repercussions for the local population

of Dagestan. It has cost them life as well as money, in addition to the staid psychological

consequences that continues to this date. The latter element has also had its effects on the

Russian forces fighting in the region. As a matter of fact, Russia has been following a ‘no

comprise’ policy in Dagestan since the past few centuries and continues to maintain a

strong Russian presence in the region through the deployment of national military forces.

Similarly, the Russian occupation of Chechnya has not only been for the sake of

glorifying Russian imperial personification. Sharing a healthy border line with Georgia

and the Russian Republic of Dagestan, Chechnya not only had the signs of becoming a

(13)

transport route in the future, but it also could serve as a military base for Russian

advances into Dagestan and vice versa. Therefore, the Caucasus War was not an

endeavor at annexing only a state or two of the region but was in fact the reflection of

Russian aims on the entire Caucasus region for the advantages presented by the Caucasus

region becomes a fading possibility if even one of the states falls out from the Russian

grasp.

In short, the importance of the region is further attested by the fact that North Caucasus

lying at the crossroads of three powers; Ottoman Caliphate, Persia and Russia, has also

always served as Russia’s bridge to Transcaucasia, Europe and Asia. Of the four North

Caucasus regions discussed above, all the states share common borders with Georgia.

The point of importance associated with Georgia comes from the fact that this small

republic opens up into the Black Sea while it also has a common border with Turkey

which was then the Ottoman Caliphate. Not only is it important to understand that

realization of the Blue Water policy had long been sought by the Russian monarchs, but it

is also a fact that the goal could not have been achieved in all its character until and

unless the power of the Ottomans had been crushed at the hands of Russians. To achieve

this end, annexing states that lied in close proximity with the Caliphate could serve the

purposes of being used as military bases, as patrolling sites for the southern waters of

Russia, pursuing an eastward expansion of the Empire, and if circumstances allowed, as

recruitment centers of stalwart and innate warriors. The latter purpose could be achieved

only if the Russian political elite won the hearts of the local populace.

(14)

Unfortunately, as it turned out, successive Russian regimes remained ineffective in the

latter task. Rather than adopting policies that could win over the trust of the locals, the

Czarist authorities, and afterwards the policy makers in Kremlin, could only add to the

miseries of the locals by adopting such policies as which reinforced feelings of mistrust

among the people of North Caucasus against foreign intruders. For example, the

Latinization of the alphabets of the North Caucasus’s language in the twentieth century

was a mistake on the part of the Soviet government for it only added to the detestation of

the natives against Russian government, which anyway had not yet achieved their trust

and respect. Similarly, the imperial practice of deporting the local population and

repopulating the area with new settlers has shaped such grave nostalgic feelings among

the locals that so continues to this date. In fact, the establishment of Cossack settlements

around Kuban River is regarded as the starting point of ethnic tensions between Russia

and Northwest Caucasus. An even worst episode in the history of Russian relations with

the ethnic minorities of the North Caucasus was the forced exile to Siberia and Central

Asia in the face of their alleged involvement in the Nazi attack on USSR. The death of

thousands of the exiles in the aftermath of the exile could only highly intensify the

feelings of abomination towards the Russians. Furthermore, the Soviet leaders often

made promises that were not so well kept in practice. For example, Stalin’s promise of

allowing Dagestan to retain Shar’ia courts soon proved to be a mere political lie. This

attitude has led to the creation of a common Chechen proverb of ‘to lie like the Russians.’

For the Bolsheviks, struggle against oppression by any group within the country was

justifiable so long as the Soviets regime had not been established. But once in power, any

such attempt was quelled and repressed most brutally in the name of wider national

(15)

interests. For the policies towards North Caucasus, to many it would seem that Russian

policy makers were either ignorant of the strong psychological associations that people of

tribal culture normally keep with their social and religious customs or they were largely

sure that centre’s policies could be dictated anywhere across the lengths and breadths of

the country. The surety does not carry much justified grounds as the twenty five year long

struggle with Imam Shamil alone gave a clue as per the strong political and ideological

adherence of the tribes. In fact, Islamization of Caucasus also owes itself to the

commonly held outlook towards Christianity as the religion of the imperial forces while

Islam was viewed as the religion of resistance and freedom fighters. As it turned out, the

conventional attitude of Russia towards its ethnic minorities remained largely unchanged

for the most part of the Cold War era. Things were to get further heated in the early post-

Cold War era as will be discussed in the coming chapters.

In the case of China, the territorial expansions date back to the pre Christ era. For

instance, China’s links with Xinjiang date back roughly to 206 BCE, when the Han

dynasty established a military command for the region for the first time. With the passage

of time, Xinjiang became indispensable for successive Chinese governments as the

defense of mainland China depended largely on the security of this province. This was

due to the fact that Xinjiang shares common borders with Russia, the Central Asian states

of Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan and the Indo-Pak subcontinent. An attack on this

remote region of the Chinese Empire would leave the mainland open for foreign

advances. It was for this reason that the control of this area remained a prime concern for

Peking. The proximity of the province with Russian, Central Asian and Indian states

made it an active trading center thereby simultaneously adding to the economic

(16)

importance of the region for Chinese government as well as diversifying the religious and

ethnic blend of the province. The Qing dynasty made a reasonable decision when it

decided to keep the administration of the province through Muslim officers, as by this

time, Islam had become the predominant religion in Xinjiang. However, the

experimentation with cultural tendencies in the twentieth century was an unwise decision

of the CCP. For example, following on the Soviet model, Beijing introduced Cyrillic

alphabets for the local writing system of Xinjiang. The local resentment against this

reform added strength to Uyghur demand for independence thus strengthening the cause

of East Turkestan Independence Movement (ETIM).

China has faced an equally challenging task in Tibet where its claim on the latter has

been challenged by many as having weak historical grounds. Nevertheless, losing Tibet

would have meant losing a natural wall of protection in the Himalayas. But unfortunately,

Tibetan’s experiences of Chinese rule are far from pleasant. While China continues to

send ethnic Chinese settlers for the management of new industries, and build military

bases in the region, cultural tendencies of the locals are often compromised. As a matter

of fact, Tibetans now have little choice but to live in cities which is very much against

their nomadic temperament.

The defense of the Chinese heartland includes the compulsion to maintain absolute

control on both Xinjiang and Tibet. To meet this end, Chinese policies in these quarters

have included the use of force which in turn has intensified anti-Chinese sentiments of

the indigenous population. Moreover, the discovery and exploration of hydrocarbon

reserves, minerals and metals deposits in both Xinjiang and Tibet, further adds to the geo-

(17)

political and geo-economic magnitude of the regions for Beijing. Ironically, the major

complain coming from these regions remain the same; the major beneficiaries of new

government projects in these areas continue to be Han Chinese (who come from Han

populated areas on government orders), and that China does not take into account the

religious and cultural penchant of the locals while initiating new projects. The latter

element is similar to complains coming from the North Caucasians. As for the question of

beneficiaries, Russian experience has been different from that of Chinese. For during

most of the Soviet era, most of the industrial projects were designed for areas with a

predominant majority of ethnic Russians.

As far as the Taiwanese question is concerned, the issue has become more of a question

of China’s international prestige. The importance of Hong Kong has been of a rather

peculiar nature. The small island served as China’s window to the west in the early years

of the reversion and also when SEZs were opened along the Chinese coast. The zones

being in close proximity with British Hong Kong had much to learn from the capitalist

experiences of the latter as well as form the technological work craft of the experts in

Hong Kong. It was only because of Beijing’s complete understanding of the geo-

economic significance of the island that at the time of signing the Joint Declaration,

China prudently vowed to keep the existing social, political and economic system of the

island unaltered.

All in all, China and Russia had their share of challenges in their dealings with the ethnic

minorities in their borders. As it came out, both the powers experimented and counter-

experimented with their own sets of prophecies that they believed could best attain the

(18)

centre’s aspirations. As the world entered a new epoch in 1991, Beijing and Moscow

were also to experience novel trends and tendencies of the new global eon not just in the

mainlands but also in the remote quarters that were now to become the headlines of

global geo-politics.

China’s peripheries and its ethnic minorities

Until the nineteenth century, the administration of the Chinese Empire was loosely

divided into three classes. The imperial government in Peking largely governed the

central agricultural territory inhabited by Han Chinese, while the tribal territories and

peripheral areas, either peacefully annexed or formally conquered, were governed under a

system of titles and ritual obligations. The tribal or inner zones of the empire carried

close ethnic and cultural similarities with the center and were thus brought into Chinese

system of governance over the period of time. On the other hand, the peripheral areas

were inhabited by people who were culturally more different from the people of the

central territory and were left out in this process of center-periphery incorporation. The

ethnic unrest in the present times is experienced in the historical outer peripheries of

China, namely; Tibet and Xinjiang. The two regions became part of the Chinese Empire

during the times of the Mongols and Manchus respectively. After 1949, the new

government launched autonomous system of governance for its ethnically populated

areas. With the launch of ethnic classification program in the early years following

Communist victory, there are now 55 officially recognized ethnic minority groups in

China and every citizen has an officially registered nationality.9This was followed by the

9. This practice was more in the like of Soviet example and against Confucian principles

(19)

creation of ethno-regional units and prefectures; thus giving way to political orchestration

under the centre’s umbrella. In these prefectures were introduced socio-economic and

preferential measures for the promotion of these areas, along with the new method of

appointing regional heads through collaboration between the centre and the ethnic

proletariat.10

The introduction of regional autonomy also meant that henceforth, not only

the central and internal tribal zones, but also the historical outer peripheries of China

must conform to the highly centralized party leadership. Along with this, with the

evolution of Chinese socio-economic landscape, new problems have surfaced in center-

periphery relations. Beginning with the 1990s, “economic liberalization has ended

guaranteed employment and encouraged competition- leaving the lower classes socio-

economically abandoned…new policies have served to reconnect ethnic masses with

formal religious authorities consolidating ethnic identities weakened during the socialist

era.”11

In addition to religious revival among the masses, the same practice was a notable feature

in the early years of post-Mao period, state authorities renovated the religious buildings

destroyed during the Cultural Revolution. Religious figures, who were then persecuted,

were also compensated by the state. The underlying factor behind this motive was an

attempt at legitimizing religion with government aide, thus strengthening centre’s control

on religious affairs. One of the outcomes was in the form of private medressahs. The

local Uyghurs often favored these medressahs against secular schools for the education of

their children. As a result, a wave of restrictions and regulations were issued by the centre

10. Yan Sun, The Roots of China’s Ethnic Conflicts, available at http://www.oakton.edu/user/2/emann/spring2015/Chin

a%20Materials/The%20Roots%20of%20China%E2%80%99s%20Ethnic%20Conflicts.pdf 11. Yan Sun, The Roots of China’s Ethnic Conflicts, available at http://www.oakton.edu/user/2/emann/SPRING2015/C

hina%20Materials/The%20Roots%20of%20China%E2%80%99s%20Ethnic%20Conflicts.pdf

(20)

against private medressahs; a move that was met with strong resistance from the locals,

the effects of which continue to this date.12

“Since the late 1980s, local restrictions have created demand for imported

Islamic sects in China’s black market of religions. Wahhabism, a

puritanical strain of Saudi origin previously marginalized in Xinjiang’s

mostly Sunni communities, arrived by way of Muslims returned from

pilgrimages to Mecca, visiting foreign religious groups, and newly

independent Central Asian states…Spreading through existing and new

madrassas, Wahhabism won converts…As Wahhabism spread, traditional

imams began to seem old and outdated, unable to prevail over the young

talibs trained in the underground madrassas. Local authorities initially

viewed their clashes as an intrafaith matter and refused to intervene,

leaving the new sect’s madrassas to grow uncontrolled. Less educated

youths dominated the ranks of its adherents, especially among the

unemployed, the self-employed, and students.”13

By the next few years, socio-economic frustration had badly engulfed the Uyghur society,

leading to hatred for the Han government of the centre. This has been often manifested in

social boycott of government orders and campaigns. The resulting violence in XUAR,

forced the authorities in Beijing to strengthen its religious policies. The government

started the practice of giving subsidies to appointed imams. In both TAR and XUAR, the

12. At present only a handful of medressahs function in the region. The age of attendance allowed in these medressahs

is above 18. 13. Yan Sun, The Roots of China’s Ethnic Conflicts, available at

http://www.oakton.edu/user/2/emann/SPRING2015/China%20Materials/The%20Roots%20of%20China%E2%80%99s

%20Ethnic%20Conflicts.pdf

(21)

centre has placed several restrictions on the observation of religious practices by the

locals and has therefore received stern opposition on account of the same. The self-

immolations of Tibetan monks are one such example where Beijing had to face

international humiliation as a result of its policies towards the peripheries. However, it

must be noted that the incidences of self-immolation are observed among the monks of

Gelugpa sect of Tibetan Buddhism which is headed by the Dalai Lama. Therefore, state

control is most strict in the monasteries belonging to this sect. This, together with the

socio-economic situation prevalent in the regions, has furthered the centre-periphery gap

in China.

In Hong Kong, China does not have to confront such problems as seen in Tibet or

Xinjiang. Ever since the reunion of Hong Kong with the mainland, the small island

territory has provided no trouble to the centre. In fact, it has rather provided important

lessons in market innovation to the mainland and has continued to be China’s window to

the west. However, in the recent past Beijing has attempted at remodeling the political

apparatus to its liking. The response to these endeavors has been profound; hinting at the

probable unwanted results that could arise if Beijing must continue its endeavors in the

island, the people of which have enjoyed social, political and intellectual liberty since

ages.

China’s relations across the strait have also proved a testing venture for the central

government. It took several years for Beijing and Taipei to normalize bilateral relations in

the favor of regional trade and political balance. China also considered smoother cross-

strait ties as influential in undermining increasing US presence in the region. In the case

(22)

of Taiwan, developing reasonable diplomatic ties with China was indispensable in view

of the magnitude of expanding Chinese market in the world. While both China and

Taiwan agree on the existence of only one China, it remains debatable where the

legitimate government lies. In fact, Taiwan has a complex history. It has a majority of

ethnic Han population that migrated from Fujian and Guangdong, while the indigenous

population makes up approximately 2% of the population.14

Kuomintang (KMT), which

has governed the island for the better period since 1949, has held a pro- One China

Principle approach. But the recent victory of Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in

2016 elections has evoked serious concerns across the strait as the latter stands in firm

favor of a de jure independence of Taiwan and has also voiced its reservations against the

1992 Consensus which upholds One China Principle.

The Dagestan ASSR, Gorskaya ASSR and ethno-federalism in the Caucasus

During the early years of the twentieth century, the Southern Caucasians did not demand

independence from Russian Empire. Armenia saw Russia as a safety guarantee against

Ottomans, the Georgians lacked the middle class who could run an independence

movement, while the Azeri were caught between two options; either to remain as

Caucasian Muslims in the Russian Empire or become part of a larger Turkic statehood.

The Russian Revolution of 1917, and the fall of the Ottoman Empire in 1918 created a

power vacuum across the length and breadth of the Caucasus region. With the February

Revolution of 1917, the provisional government in the center was presented with a

declaration of the Union of Caucasian Mountain Peoples by the people of North

14. http://www.cfr.org/china/china-taiwan-relations/p9223

(23)

Caucasus, thus creating the North Caucasus Republic. A constitution was also drafted for

the new Republic with a bicameral parliament. The purpose of the North Caucasus

Republic was more to serve as representatives of the people of the mountains than to

serve as an independent political union. Things however changed with coming into power

of the Bolsheviks; the new Republic declared independence from Russia soon after the

ensuing of Bolsheviks in power. Moreover, the civil war between Red and White armies

had its effects on the Caucasians as well. Although the people of the region were not so

much as in favor of the White Army, but a section of the Muslim fighters were wooed by

the pledges made by General Denekin of the White Army. Thus, many administrative

posts were taken in the White sphere of influence. However, when the Red Army entered

Dagestan in 1920, the political situation in North Caucasus changed in favor of the latter.

Under the policy framework of Lenin, an appeal had already been sent in 1917 by the

Council of the People’s Commissars to the Muslim population of Russia in 1917 which

promised them the right of national, social, religious and cultural self-determination in

the new state. Therefore, in 1921, an Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (ASSR) for

Dagestan and a Mountain Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (Gorskaya ASSR) was

formed. It included Chechen, Kabardian, Balkar, Ingushetia, Karachay and Vladikavkaz

orkugs. The Caucasians were allowed autonomy and a Sharia-based system in their

territory. The agreement was but a compromise that manifested the degree of flexibility

which the still weak Soviet government could create for the time until when the state

could exercise absolute control on its domain.

The process of bringing the entire Caucasus region under Russian control was started

during the imperial times and was completed by the USSR by bringing the whole region

(24)

under the control of the centre. Under the rule of the Soviet Union, the region was

divided into titular administrative units. When it came to administrating the vast expanse

of the new state, Soviet Union had three main tasks: the first task was “the organization

of territorial authority. To rule an area….it must be divided into administrative units

subordinated to a central hierarchy.” The second goal was to “bind the nations….

awakened by war, revolution, and state collapse, into a common state. The third

challenge stemmed from the need to win internal and external legitimacy for the new

Soviet state.”15

The possible solution to these tasks was attained through the principle of

Soviet ethno-federalism. All important matters were designated to the centre of the

federation, while the administrative units created under titular heads were given limited

autonomy and privileges. The hierarchy under ethno-federalism comprised of the union

republics or Soviet Socialist Republics (SSRs) at the top. The combination of SSRs

formed the USSR. Second in hierarchy were the ASSRs (Autonomous Soviet Socialist

Republics). The ASSRs were not always the regions that covered strategically important

frontiers, nor were they larger than the union republics. The Autonomous Oblasts (AO)

or the Autonomous regions comprised of small ethnic groups within a condensed area.

The fourth in place in the ethno-federal hierarchy were Autonomous Orkugs or

Autonomous Units comprising of small ethnic groups inhabiting a condensed area within

an oblast. The union republics were designated as sovereign states in the Russian

constitution, had their own parliament, constitution, courts of law, military, and also had

the right to form direct relation with foreign powers. The ASSRs on the other hand were

not sovereign states but national states where only Russian prevailed as the official

15. Abdurakhman Avtorkhanov, The North Caucasus Barrier: The Russian Advance towards the Muslim World,

(London: C. Hurst & Co, 1992), p.24

(25)

language. The oblasts enjoyed limited privileges and did not have the right to form

regional bureaucracy.

The system of ethno-federalism had integrated into the entire Soviet state by 1924. In the

South Caucasus, Azerbaijan, Armenia and Georgia were awarded the status of union

republics. The South Ossetian Autonomous Oblast was incorporated in the Soviet

Republic of Georgia. In the North Caucasus, no titular nation was created. An ASSR was

established for Dagestan, along with a common ASSR for the culturally similar

Chechnya and Ingushetia. The Kabardins and Balkars, though culturally dissimilar, were

also awarded a common ASSR of Kabardino-Balkaria. In a similar context the Karachay-

Cherkessia ASSR was carved out for the Altaic speaking Karachai and the Caucasian

Cherkessia. Ossetia, inhabited by a Christian majority was divided into the North Ossetia

ASSR and the South Ossetian AO with the Georgian SSR.

Other than slight changes introduced in the post-Stalin USSR or the reforms under the

constitution of 1936, the Soviet ethno-federalism remained largely unchanged from 1936

to 1991. This system of government was, in effect, a tool for the Soviet leadership for

maximum control across the large state. However, the system had another effect which

was not quite discernible at the time. Under this system was engineered an institutional

affiliation with a prescribed territory. The institutions installed in the ethnic and territorial

groups of USSR crafted a local elite that served within the Soviet designed borders. This

was the first form of modern statehood in the Caucasus. Before the Soviet times, the

concept of nation was not so much as “institutionalized” in the North Caucasus, and even

in the South it only had weak foundations. Region, religion, and clan were what defined

(26)

‘identity and collective action’. The incorporation of Caucasus into the Soviet Union was

a blessing in disguise for the local populace as it brought with itself the ideas of

nationhood and statehood.16

Form the medieval times to the Afghan adventure in the twentieth century, Russia’s

policy towards minority regions in general and Muslim populated areas in particular,

have been that of subduing and then winning over the local population. The leaders of

Soviet Russia reinstated the anti-religion policy of Ivan the Terrible, Peter the Great, and

Tsarina Anna. The policy was introduced in North Caucasus in 1924, earlier than in other

parts of Russia, where the policy was instituted in 1928. The involvement of Sufis in the

socio-political life of North Caucasus was one of the reasons why the campaign was

launched earlier in this part of the state. The leading Communist leader in North

Caucasus, Najmuddin Samurskii, made this clear when he stated in 1925 that “Revolution

in Dagestan means above all a fight with the clergy.” Nevertheless, the medressahs in

Dagestan still numbered at 1500 in 1925. To this situation, Najmuddin was predictive

enough to realize that “to close the madressahs is impossible. They will continue to exist

whatever oppressive measures are taken against them. They will hide in the canyons, in

the caves, and will then form a people who will be fanatical opponents of the Soviet

power which persecutes religion.”

The Soviet government, still continued its harsh policies, and in 1944 a considerable

population of the local Muslims was deported from their native region. During this

period, the Soviet rulers also installed a new policy in the territory of Ingushetia and

16. Ibid, pp.24-27, 31-32

(27)

Chechnya; of containing the official structure of Islam in the region. Consequently, all

the mosques in the region were closed down until 1978. But this policy failed in face of

the strong spiritual reputation enjoyed by the Sufis in Chechnya and adjacent areas, where

the words of a Sufi were as binding as a political or religious law. An article published in

the Dagestan Journal in 1989 may very well be used as a reference for understanding the

approach of the Muslims of North Caucasus towards Sufism and Soviet rule:

“The people know that the leaders who preach atheism have an ingrained

habit of profiteering, money-grabbing and corruption. Their words do not

correspond with their deeds…. The mullahs are closer to the people and

the believers…. They are on the same level as other people, be they

scholars, rich or poor. They have a common language with everyone, they

do not offend or frighten, they only teach and preach. This is why all

believers are equal, nobody demonstrates their superiority, nobody

ingratiates themselves or grovels. Almost all believers are open to each

other, speak the truth whatever it is, and do not give bribes to the

mullahs…. That is why believers are attracted to the mullahs, not to the

Party workers. That is why, the mullahs have great authority.”17

On a larger generalized perspective, although all the Ciscaucasian republics have played

their part in the struggle against foreign designs, four of such states shall be discussed in

detail in this and subsequent chapters; Chechnya, Dagestan, Ingushetia and Kabardino-

Balkaria.

17. Ibid, pp.6-8

(28)

CHAPTER - 1

A BRIEF INTRODUCTION TO THE PERIPHERIES

OF RUSSIA AND CHINA

Not only the politics in Chinese mainland have seen various ups and downs since 1949,

the domestic issues in the areas occupied by ethnic minorities have been an equally

daunting challenge since the inception of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)

government. The remoteness of these regions along with varying religious, cultural and

social elements became an obstacle against the implementation of CCP’s reforms in these

areas and thus led to continued and consistent disturbance across these quarters.

China covers a large part of the Asian continent. From the very beginning of this unique

civilization, it has been conquering the neighboring areas, and had thus enlarged its

boundaries. As a result of these foreign ventures from time to time, China has had a claim

on many areas in its proximity, some of which also slipped out of Chinese control during

various periods of the country’s imperial history. The important regions included in this

context are Taiwan, Hong Kong, Macau, Mongolia, Tibet, Xinjiang and the Sipsong

Panna. In some cases, it seems as if a solution has been reached upon, in others it seems

that the state of affairs is going in the same direction as they have been going since the

past many decades. There are also regional problems, where China has evolved its policy

to meet standards of the new age. Other than the fact that suzerainty on these areas once

represented the might of the Chinese Empire, there are various other underlying facts

which today motivate Beijing to adhere to its territorial claims. In addition to how the

demands of the age might require China to act in the current circumstances, Beijing is

(29)

also driven by its growing needs to solve these issues as best suitable for its national

interests. China’s growing power requires it to seek solutions and maintain a positive

international image simultaneously.

Analyzing the current state of affairs in the regions can be made easy by looking into the

nature of relationship that has existed in these particular regions since the very inception

of Chinese suzerainty there to the current atmosphere in China’s periphery.

1.1 PROBLEMS ON THE ROOF: CHINA’S PRESENCE IN TIBET

Often dubbed as the “roof of the world,” Tibet occupies 471, 7000 square miles of the

plateaus and mountains in Central Asia. It is surrounded by Chinese provinces in the east,

northeast and the southeast, Nepal, India, Bhutan and Myanmar to the south and Jammu

and Kashmir to the west.18

While China claims that Tibet has always been a part of China,

Tibet has a history of independence of approximately thirteen hundred years from

China.19

Political contact between the two kingdoms started in the seventh century CE,

when the King of Tibet Songsten Gampo unified the country and established a dynasty

that was to last for two centuries. He extended Tibet’s frontier to include parts of the

Xinjiang province, Kashmir, Ladakh, Kansu, Qinghai, Sichuan and Yunnan provinces.

Many of these areas were also parts of the Chinese Empire under the Tang Dynasty. Tibet

captured Changan, capital of the Tang dynasty, when China stopped paying tribute to the

former.20

In 821 CE, the two countries put an end to almost two hundred years of war.

The treaty declaring the end of war was engraved on three stone pillars, one of which still

18. Dinesh Lal, Indo-Tibet-China Conflict, (New Delhi: Kalpaz Publications, 2008), p. 105. 19. Ibid, p. 31. 20. Melvyn C. Goldstein, The Snow Lion and the Dragon: China, Tibet and the Dalai Lama,(California: University of

California Press, 1997), p.1

(30)

stands in the Jokhang cathedral in Lhasa. The treaty established borders between the two

countries. This shows that during this time both China and Tibet were independent

kingdoms; none being subordinate to the other.21

During the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, both China and Tibet came under the

Mongol influence. China often claims today that China and Tibet became united as one

country at this point in history, as both the countries were dominated by the Mongols.

However, the claim is little convincing. Not only is the time era of the Mongol’s relations

with the two countries different, the nature of relationship that Mongols had with the two

regions also stood at wide contrast. Tibet came under Mongol influence before Kublai

Khan had conquered China. As a matter of fact, independence from Mongols also came

earlier in Tibet than in China. As for the relation between Tibetans and Mongolians, the

two developed a Priest-Patron relationship or the Cho-Yon. The Mongols converted to

Buddhism and sought the recognition of their rule and spiritual guidance from Tibetan

theocracy; in return, the Tibetans also pledged loyalty to the Mongol Empire.

In 1639, the Dalai Lama made Cho-Yon relationship with the Manchu Emperor, who

established the Qing dynasty in China in 1644. By the middle of the nineteenth century,

as the Manchu rule in China neared its decline, the dynasty’s influence in Tibet also

weakened. In 1842 and in 1856, the Tibetans appealed for Manchu help against the

Nepalese Gorkha invasions, but the assistance could not be provided by the Manchus,

and the Gorkhas were driven out by Tibetans without any help from Manchu China.

21. Ibid, pp. 31-32.

(31)

In 1911, the Manchu dynasty came to an end in China, and so did the Cho-Yon

relationship. In 1912, Tibet declared its independence and began to administer the

country as a sovereign nation, after Nepalese help was taken in driving the Chinese out

following a series of armed conflict between the Chinese and Tibetans during the 1911

revolution. Since 1912, the government of the Republic of China (ROC), which ruled

China between 1912 and 1949, and which now governs Taiwan consisted of a Mongolian

Affairs Commission and a Tibetan Affairs Commission in the cabinet for the

administration of the two regions. Chiang Kai-shek asserted Tibet’s status as part of

Chinese territory in 1946 and again in 1949. The ROC still claims sovereignty over Tibet

and Mongolia. But after Communist victory in 1949, Tibet was once again taken under

Chinese flag.

In fact, the ROC stance is similar to that of PRC (which has ruled mainland China since

1949), which is that, Tibet has been a part of China de jure since the Mongol Yuan

Dynasty ruled China. PRC contends that according to the theory of the Succession of

States in International Law, all the subsequent Chinese dynasties and governments have

succeeded the Yuan dynasty in exercising de jure sovereignty and de facto power over

Tibet. Although the current Chinese government recognizes the cultural and linguistic

uniqueness of Tibet, this position, they believe, does not justify Tibet’s demand for

independence as China has a unique combination of 56 ethnic groups in its nation.

From 1912 to 1951, China or ROC had no effective control over Tibet; but even this

situation does not assert Tibet’s independence as many regions in China exercised de

facto independence at the time when China was internally disturbed by warlords,

(32)

Japanese invasion and civil war. Moreover, Tibet did not receive recognition from any

country during the years of the ROC government.22

After PRC’s retake over Tibet; the

Seventeen Point Agreement was signed between PRC and the representatives from Tibet

in 1951. The agreement was the first formal Sino-Tibetan treaty after 821 CE. Under the

terms of the agreement Tibet was incorporated into China along with a guarantee by the

latter for refraining from any attempt against the alteration of Tibetan religious, cultural

and political systems and institutions. The agreement was however short-lived, as in

1959, Mao’s imposition of democratic reforms led to an uprising in Lhasa, the capital of

Tibet. In retaliation, China adopted a harsh policy to control the uprising.23

Dalai Lama

fled to India along with his followers in the aftermath of the events. Since then the

Tibetan government-in-exile has declared the Agreement invalid as the Chinese have

violated the pledges undertaken in the Agreement. On the contrary, Chinese blame

Tibetan government for having deliberately tried to sabotage the Agreement in an attempt

to “split the motherland.” Thus, even the nullification of the treaty and the resulting

political tension failed to fulfill the obligations undertaken in the Agreement. On the

other hand, the Sino-Tibetan revolts also cast light on the fact that not only were they

retaliation to the violation of the Agreement by the Chinese government, but were also an

attempt to regain independence. The 1959 conflict brought more problems for Tibet than

it did for China. The signing of the treaty had ended the so-called independence of Tibet

and had given her considerable autonomy. However, the demise of the Agreement

brought an end to the autonomy as well.

22. Dinesh Lal, Indo-Tibet-China Conflict, Op. cit., pp. 31-32,50-53,58,60. 23. An estimated 87,000 people were killed, arrested, deported to labor camps or exiled. Ibid, p. 105.

(33)

In 1981, China offered a Five-Point Proposal to the Dalai Lama. The latter rejected by

saying “instead of addressing the real issue facing the six million Tibetan people, China

has attempted to reduce the question of Tibet to a discussion of my own personal status.”

In 1988, China was presented the Strasbourg Proposal by Dalai Lama as the basis for

Sino-Tibet negotiations. Beijing rejected the same and declared that “China’s sovereignty

over Tibet brooks no denial. Of Tibet there can be no independence, no semi-

independence, no independence in disguise.”24

The issue has taken a new shape as China has been unwilling in giving much autonomy

to Tibet, even that which was guaranteed in the Seventeen Point Agreement. On the other

hand, Dalai Lama has repeatedly refused to accept China’s sovereignty.25

Some western

thinkers and Tibetans have also demanded “one country, two systems” formula for Tibet

on the model of Hong Kong. For Beijing, the formula which will bring currency, judicial

independence, an international border with China and representatives in international

organizations, would be offering too much to Tibet. Beijing also thinks that the “one

country, one system” formula has been in practice in Tibet for the past many decades,

making “one country, two systems” formula inapplicable.

Thus, China entered the post-Cold War era with the simmering Tibetan question still at

hand, as policy makers in Beijing continued to draft plans for Tibet best suited to China’s

national interests.

24.Changqing Cao, Chang Ching Tsao, James D. Seymour, Through Dissident Chinese Eyes: Essays on Self-determination,

(New York: M.E Sharpe, Inc, 1998) , p.65 25. Ibid, pp.59-67.

(34)

1.2 XINJIANG: CHINA’S MUSLIM FRONTIER

Covering an area of 1.6 million square kilometers or one-sixth of China’s total covered