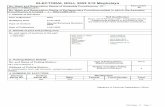

Name of Electoral Area Census Block Code Name of Electoral ...

Reconceptualizing state formation as collective power: representation in electoral monarchies

Transcript of Reconceptualizing state formation as collective power: representation in electoral monarchies

Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found athttp://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rpow21

Download by: [Anna Lindh-biblioteket] Date: 14 September 2017, At: 00:56

Journal of Political Power

ISSN: 2158-379X (Print) 2158-3803 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rpow21

Reconceptualizing state formation as collectivepower: representation in electoral monarchies

Peter Haldén

To cite this article: Peter Haldén (2014) Reconceptualizing state formation as collectivepower: representation in electoral monarchies, Journal of Political Power, 7:1, 127-147, DOI:10.1080/2158379X.2014.889404

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/2158379X.2014.889404

Published online: 24 Mar 2014.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 307

View related articles

View Crossmark data

Reconceptualizing state formation as collective power:representation in electoral monarchies

Peter Haldén*

Swedish National Defence College, Stockholm, Sweden

This article deals with the importance of collective power and value consensusamong elites for medieval polity formation by analyzing electoral monarchies.State formation theory focuses on the monopoly of legitimate armed force andhas pushed notions of consensus and collective power into the background. Thisarticle questions material and coercive theories of state formation and emphasizespolity formation through theories of power as collaboration and as the ability toact in concert. Royal elections had two major functions: (1) A transfer of authoritythat created trust and concord among elite groups and (2) constructing ideas of anabstract ‘realm’ that political actors represented and to which they wereaccountable in an ideational and symbolic sense. The article focuses on the HolyRoman Empire and Sweden.

Keywords: State formation; representation; collective power; consensus;monarchy

Introduction

Most theories of state formation focus on the importance of coercive power in oneform or another. While this is undoubtedly important, I argue that it has led to aneglect of the importance of collective power and value consensus among elites forthe formation of polities during the European Middle Ages. I support my argumentby studying electoral monarchies in central, eastern and northern Europe. Althoughlocal variations existed, this institution consisted in an assembly of nobles electingthe King who came from a noble lineage. Sometimes the electorate chose betweendifferent candidates and sometimes there was only one. In all cases, the candidatehad to negotiate the conditions for his election with the nobles. In this form of rule,neither a candidate for kingship nor a ruling monarch could force his will upon thenoble ‘demos’. Instead, he had to negotiate with his co-rulers who had handed himauthority. By analyzing electoral monarchies as a form of representation thatconsisted in performative actions that constitute social systems, their componentparts and their relations, I will propose a new interpretation of polity formation inEuropean history.

This article argues: (1) Representation in electoral monarchies was a transfer ofauthority that created trust and concord between the Prince and important socialgroups as well as among important social groups. Trust is a precondition of allsocial systems and by linking social formations and individuals representation

*Email: [email protected]

© 2014 Taylor & Francis

Journal of Political Power, 2014Vol. 7, No. 1, 127–147, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/2158379X.2014.889404

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ann

a L

indh

-bib

liote

ket]

at 0

0:56

14

Sept

embe

r 20

17

enabled larger units and enhanced cooperation. The institutionalization of trust andthe political community were preconditions of the more complex systems that werebuilt during the early modern era. Consequently, we have to look at state formationthrough theories of power as collaboration and as the ability to act in concert, notjust – as so often has been done in previous theories – through theories that definepower as coercion or as a zero-sum relation. Hence, the article questions exclu-sively material and coercive theories of state formation. (2) political representationin the practices and belief systems of electoral monarchies constructed ideas of anabstract ‘realm’ that political actors represented and to which they were account-able, in an ideational and symbolic sense if not in a formal institutional one. Thisconception of the realm created and sustained medieval polities by creating trustand by uniting powerful actors that otherwise might have opted out of the polity.The abstract realm that political actors represented was an element of cohesion in atime before the coercive and redistributive apparatus of the state had been devel-oped. Consequently, we have to consider and analyze the formation of politicalcommunity – or, perhaps, ‘polity formation’ as a crucial precondition and processof state formation.

This article points towards a new theory of polity formation that stresses trust,political community and power – the latter defined as the ability to act in concert– as the central elements rather than coercion and material factors. The institutionof electoral monarchy was unique to central and northern Europe but it createdeffects that were similar to the more familiar political institutions in westernEurope. As Kantorowicz and Ullmann have shown, the conception of the abstract‘Crown’ strengthened and stabilized the English polity and fostered the idea ofcollaborative rule. The fact that although central and northern European institutionsdiffered in form from English ones, they created similar effects strengthens thegeneral argument that polity formation rests on power as the ability to act inconcert, not only coercion. This argument also has implications for twenty-firstcentury politics. Most programs of ‘state-building’ in fragile and developing statesare based on a view of the state that emphasizes the monopoly of violence and/orthe effective provision of public goods. If instead we see the state as resting uponpower as defined as cooperation and having political community as its crucialprerequisite, then such programs have to be seriously re-thought.

The article is organized in the following way: Section 2 discusses theories ofstate formation and forms of power, Section 3 discusses historiographies ofrepresentation and state formation, Section 4 outlines a theory of representation asconstructing ties between social actors and as constitutive of political communities,Section 5 analyzes the electoral monarchies of the Holy Roman Empire andSweden and Section 6 outlines the implications of this article for theories of powerand state formation and sketches a new theoretical description of historical polityformation. The conclusions summarize the article.

State formation and power: coercive or collective?

Theories of the state and state formation are impossible without theories of power.However, most state theorists have focused on the coercive or, in Michael Mann’sterms, distributional theories of power. Max Weber’s definition of the state, whichhas become almost canonical in the social sciences, emphasizes coercive power bystressing the need to successfully uphold the claim to a monopoly of a legitimate

128 P. Haldén

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ann

a L

indh

-bib

liote

ket]

at 0

0:56

14

Sept

embe

r 20

17

territory in the enforcement of its order. Possessing a monopoly on legitimate vio-lence and supreme capabilities thereof in order to defeat external foes and internalrivals is central to state formation theories due to the roles played by the competi-tive international system and inherent warfare as drivers of state formation (Hintze1975, Tilly 1992, Ertman 1997, Hobbes 2008). Less ‘Realist’ and more Marxist or‘Marxomorph’ theories also emphasize coercive power but of a primarily inter-classkind rather than inter-state, in upholding stratification, property relations and thepossession of the means of production (Anderson 1974, Teschke 2003). Similarly,considerable parts of political theory take conflict between organized interests andclasses as a starting point of politics. Although these aspects of power in the stateand in the process of its formation are formidable and cannot be overlooked, ourfocus on them has overshadowed the importance of consensus and collectivepower. Intuitively, many observers would agree with Weber in defining power asthe power to issue commands or with a definition of power as the ability to with-hold knowledge or forestall ways of thinking (Lukes 2005, Gramsci 2010). How-ever, as Mann has argued, we also need theories of power as collaboration (Mann2012, pp. 6–10). To distinguish between the two principal forms of power, Manncalls the first despotic/distributive and the second infrastructural/collective power.Even more precise is Arendt’s definition of power as the ‘capacity to act in concert’(Arendt 1972, pp. 143–155). This view stresses that power depends on a group, onconsent and on legitimacy.

State formation and political representation

Accounts of the history of representation in the social sciences can be divided intothree broad and partially overlapping groups: one group traces the origins of mod-ern institutions and ideas; a second assesses the role of representative institutions inthe macro-process of state formation; and a third stresses the distinction betweenpre-modern and modern political forms. First, a long tradition in social thoughtidentifies medieval representative institutions as the origins of modern parliamentsand modern representation (Hegel 1966, p. 96; Hintze 1970; Koenigsberger 1971;Bosl and Möckl 1977; Downing 1989; Blickle 1997; Bisson 2009). Althoughconsiderable in scope, scholarly interest in the history of political representationsuffers from temporal and geographical biases. Most accounts of democratizationand representation deal with a period from the seventeenth or eighteenth centuryonwards (Lipset 1960, Moore 1966, Rustow 1970, Ankersmit 2002, Shapiro 2009,Manow and Camiller 2010). However, some works include selective accounts ofearlier periods in European history such as representative government in ancientGreece, medieval theorists and the scholars of the Italian city republics (Pocock1975, Skinner 1978, 1992). The historiography of political representation also has ageographical bias that focuses on western Europe and, in particular, English andItalian ideas (Held 1997, Nederman 2009). Similarly, theories of kingship and rep-resentation have been studied primarily with regard to western Europe and themeslike symbolism and the body politic (Kantorowicz 1997). This historiography over-looks central, eastern and northern European traditions such as electoral monarchy.There is of course substantial historical research on the traditions of Germany andSweden but it has largely confined itself to national contexts and rarely engaged incomparative research or contributed to social and political theory – which is thepurpose of this article.

Journal of Political Power 129

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ann

a L

indh

-bib

liote

ket]

at 0

0:56

14

Sept

embe

r 20

17

Second, late-medieval representative institutions have been studied as elementsof state formation. The standard account is that local and national assembliesenabled a more effective system of taxation which yielded revenue to the state,gave rulers control over their subjects and, as a side effect, gave taxpayers a stakein the state (Downing 1988, Tilly 1992, Ertman 1997, Rokkan et al. 1999). Thisrather narrow and functionalist interest in representation is a result of the influenceof the ‘warfare thesis’ on the literature on state formation which argues that the pri-mary driver of state formation was the systemic pressure to defend the (proto-)statefrom external and internal enemies. Although the connection between representativeinstitutions, taxation and state formation is important, at an earlier stage, representa-tion played another more fundamental but neglected role in creating the precondi-tion of the state: a political community of trust.

The third strand of research stresses the fundamental differences betweenpre-modern and modern politics. As such, this strand is deeply colored by the self-understanding of modernity, which is predicated on strict dichotomies, e.g. betweenstate and society, object and subject and pre-modern and modern (Latour 1993,Mann 2012). Conversely, it also contributes to the construction of the pre-modern/modern dichotomy. Habermas contrasts modern and pre-modern forms of represen-tation to form a theory of political modernization. He claims that representation inpre-modern Europe was only symbolic or ‘representative publicness’. According toHabermas, the monarchy, the nobility and clergy sought to overawe subordinategroups through symbolic displays of distinctness and rank by means of wealth,behavior, dress, jousts, entries and manner of speech. Consequently, representationexisted only in the sense of the Prince and the estates representing their authorityvis-à-vis the people (Habermas 1998, p. 10). Similarly, (Pitkin 1967, pp. 99,101–102, 105) argues that pre-modern representation was not true political repre-sentation, which she defines as requiring transfer of accountability and the exerciseof accountability. Like Habermas, she argues that the ‘symbolic representation’characteristic of pre-modern societies was different from and antithetical to politicalrepresentation. Symbolic representation precludes the possibility of transfer ofauthority and demands for accountability as it depends on irrational belief or faith.This mode of communication is antipolitical since it creates unquestioning subjuga-tion to hierarchies. Recent historical scholarship has sharply criticized argumentsthat stress the pre-modern/modern dichotomy by discounting pre-modern forms ofrepresentation. For example, Stollberg-Rillinger (Stollberg-Rilinger 2008) demon-strates that symbolic and ritual practices were central to pre-modern politics. Hence,symbolic and political representation cannot be neatly separated either functionallyor temporally. Instead, symbols must be seen as another means of politicalcommunication.

Before analyzing empirical cases of electoral monarchies, I will develop myinterpretation of representation as a way to construct relations between actors andan interpretation of representation as performative in its nature and constitutive inits effects.

Representation as a constitutive practice of collective power

Hannah Pitkin has outlined one of the most influential theories of representation,which she calls representation as action. She describes two broad kinds, the authori-zation and the accountability type. In authorization theory, the represented transfer

130 P. Haldén

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ann

a L

indh

-bib

liote

ket]

at 0

0:56

14

Sept

embe

r 20

17

the authority to make decisions to the representative with a broad and strongmandate. The represented are bound by the decisions, judgment and actions of therepresentative. In sum, relations of authority flow ‘top-down’. In accountability the-ory, the ‘representative is someone who is to be held to account, who will have toanswer to another for what he does’ (Pitkin 1967, p. 55). The representative isbound by the mandate given to him by the represented. The transfer of authorityand legitimacy is ‘bottom up’.1 In sum, a minimal definition of representation asaction includes an element of transfer of authority and agency from one group toanother or to a single actor. In normative political theory, authorization andaccountability are rival theories of true representation.

However, this originally normative theory can be developed into an analyticalvocabulary to map social systems as relations between groups and individuals andas configurations of authority and power. Hence, authorization and accountabilitycan exist as parts of a single relation. Beginning with the representative, we mayask whether he is free in his actions or whether, and to what extent, he is boundby negative restraints or committed to certain positive actions. Is his authorityrestricted to certain areas, issues or fields? On the part of the represented, we mayask if there is an element of accountability and how it is expressed. The mandategiven to the represented may be bound in time and/or revocable during the periodduring which the mandate is held. Instead of using these questions to evaluatewhether a certain arrangement is normatively beneficial, we can use them to maphow different actors or groups of actors are connected and how they share powerand authority.

My interpretation stresses that the actors in a social system depend on eachother and have to cooperate. It is likely that different groups will have access todifferent resources of power, which in turn may create mutual dependence sincegroup A may need the resources that group B possesses and vice versa. In discus-sions of power, resources are often conceived of in material terms or as controlover institutions. I will focus on another resource: possession of political authority.Some resources are mutually exclusive and hence subject to zero-sum competition.Authority, however, can be cumulative, shared and transferred if one decides toconfer it on another party. Moreover, it is a resource that can rarely be conqueredby arms alone. The more authority a group or person has either on its own or aspart of an authority-sharing coalition, the more that group or coalition can do. Sincerepresentation involves the transfer of authority, it can be seen as a means of creat-ing collaboration and enabling a division of authority and power between differentgroups. Hence, representation connects societal groups with each other and createslarger formations. The arrangements that we usually study as representation areauthority-sharing arrangements that result from deals as well as from powerstruggles. Thus, representation is a regulating force in social systems involving thedistribution, allocation, legitimation and control over authority, and prescribes therelations between actors in terms of ties and duties. However, it is important toemphasize that the relations between representative and represented can bedescribed not only in terms of connections, ties or bonds but also of tensions andconflicts (Pitkin 1967, p. 114).

Because of the uncertainty when one party grants authority and power to another,representation necessarily involves trust. The literature on trust is considerable andcannot be recapitulated in full here. However, for the purposes of this study, it is nec-essary and sufficient to develop the systemic role of trust. I see trust as a contingent

Journal of Political Power 131

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ann

a L

indh

-bib

liote

ket]

at 0

0:56

14

Sept

embe

r 20

17

social category existing in various degrees in different social systems (Luhmann1968, 2000, Giddens 1990). Although trust is contingent, it is nevertheless fundamen-tal since it ‘makes the formation of systems possible’ (Luhmann 1995, p. 129). Allindividuals or groups that interact face uncertainty that they can transform into trustor distrust. Trust is a more profitable strategy because it widens the scope and poten-tial for action (Luhmann 1995, p. 128). It entails more possibilities of rational action.In a social system, this means that the greater number of trusting relations, the morealternatives are available in the system (Luhmann 2000).One could phrase the problem in terms of asking how distrust is overcome in orderto create representative institutions. However, instead of trying to tell a causal story,we can tell an interpretive one where representation and trust creation are inter-twined. Representation in the sense of authority transfer and authority sharing canbe interpreted as a way of creating trust because of the mutuality in authority trans-fer and demands of accountability. Thereby representation is central to theformation of large and durable social formations. Understanding the problems ofrepresentation, trust and the formation of social systems as a causal storypresupposes, we believe that the parties existed prior to their relations. However,‘relationist’ ontologies argue that relations are ontologically prior to entities andthat entities are constituted by their relations (Jackson and Nexon 1999).

Recent developments in political theory have stressed the constitutive effects ofrepresentation which allows us to ask research questions focused on ‘what represen-tation does, rather than what it is’ (Nasstrom 2011, p. 506). In this interpretation,representation is not a process of transmission between two pre-existing entities buta performative act constructing both the represented and the representatives.2 Thereis no ‘people’ that pre-exist the representative or the act of representation(Nasstrom 2011, pp. 506–507). A similar move away from formal legalperspectives has taken place in the history discipline (Schmidt 1987, pp. 5–34,Stollberg-Rilinger 1999, pp. 1–22). Stollberg-Rillinger (Stollberg-Rilinger 2008)argues that a paramount aspect of pre-modern representation was that symbolic andritual practices were constitutive of political communities. As we shall see, theconstitutive element was strongly present in royal elections. To summarize, repre-sentation creates not only trust but also social groups, their relations and the socialwhole that we in analytical terms can call ‘the polity’ but which was usually called‘the realm’ (regnum) in the European Middle Ages. Hitherto, this interpretation ofrepresentation has not been applied to the research on the formation of polities ingeneral and states in particular. The section below outlines a first step in thisprogram.

Electoral monarchies in the Empire and Sweden

A European form of rule

Older scholarship tended to identify electoral monarchy with Germanic pre-historyand claim that it disappeared in the Middle Ages (Ullmann 2010, p. 22). This wasnot the case, in many European realms, the aristocracy or assemblies whose mem-bers were drawn from other groups elected the monarch. Even in France, whichlater became the model of absolutism, Kings were elected until the ascension ofHugh Capet (987–996). Electoral monarchies were most common in Central andNorthern Europe (Denmark, Sweden Bohemia, Hungary, Poland and the HolyRoman Empire). The Swedish monarchy was made hereditary in 1544 after the

132 P. Haldén

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ann

a L

indh

-bib

liote

ket]

at 0

0:56

14

Sept

embe

r 20

17

great Dacke rebellion (Bladh and Kuvaja 2005, p. 30). Other electoral monarchieswere considerably resilient as they were abolished only over centuries and often inconnection with wars and rebellions. The Habsburgs introduced hereditarymonarchy in Bohemia in 1620, during the Thirty Years’ War (Barudio 1998,pp. 137–144); Denmark in 1660 after a defeat against Sweden; in Hungary in 1687after the Habsburgs retook the country from the Ottomans (Duchhardt 2003,pp. 116, 139, 184). Poland–Lithuania was an electoral monarchy up until itsdissolution in 1792. The institutions of estate-based representation and electoralmonarchy of the Holy Roman Empire were actually strengthened during the seven-teenth and eighteenth centuries (Aretin 1997, Schmidt 1999) and the Empire wasdissolved only in 1806 under pressure from Napoleon. This article analyzes a verylong-lived institution but my aim is not to cover it in full, instead the cases will bestructured so as to illustrate the argument: representation contributed to polityformation by connecting elite groups in a community of trust through the transferof authority and through its constitutive effects by constructing an abstract realm.

The Holy Roman Empire

Electoral Kingship among the Germanic peoples can be traced back to the begin-ning of recorded history and was first mentioned by the Roman historian Tacitus inhis description of the Germanic tribes (Tacitus 2005, p. 33: §7). We know that itexisted among the Franks both in the Merovingian and Carolingian periods.Although the institution changed considerably over the nine centuries that itexisted, a constant feature was that the princely (fürstliche) part of the nobilityelected the King/Emperor. The Staufen dynasty attempted to transform the Germanrealm from an electoral monarchy into a hereditary one but failed (Schmidt 1987,p. 264). The failure meant that the institutions of electoral monarchy were strength-ened and made more elaborate during the late Middle ages. A major change tookplace in 1438 when a member of the Habsburg dynasty was first elected. From thenuntil the dissolution of the Empire in 1806, the House of Habsburg was the onlydynasty that was elected King/Emperor. Despite this de facto monopolization of thetitle, electoral monarchy and its institutions continued to play central roles in thepolitical life of the Empire until 1806. Due to the constraints of a single article, Iwill focus on the high and late Middle Ages albeit with occasional forays into theearly modern period. Since the German King was also the Holy Roman Emperor, Iwill refer to him as the Emperor for the sake of clarity.

Not anyone could stand for election. There was a strong idea that a number ofking-like lineages that were eligible for kingship existed in the realm (Mitteis 1944,p. 55). Material resources also explain why only certain lineages could be electedKing. The office had no independent resource base, which meant that the electedKing/Emperor had to finance ‘public’ expenses from the revenues from histerritories. This explains why the Habsburgs, the richest and most powerful lineage,dominated the office for so long. Prior to the twelfth century, there seems to be astrong case for the argument that candidates for kingship could use the authoritythat derived from royal descent to pressure nobles (princes) to vote for them. Someearly elections were open competitions between candidates from the differentpeoples of the German Kingdom, such as the Bavarians, Franks, Saxons, Suabiansand Thuringians. In the twelfth century, the political system shifted in a more aris-tocratic direction, which meant that the principle of free election was abolished.

Journal of Political Power 133

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ann

a L

indh

-bib

liote

ket]

at 0

0:56

14

Sept

embe

r 20

17

The condition for being elected King was that an agreement could be reached withthe noble electorate. Royal descent does not feature as a condition for election inthe sources and no candidate raised kinship with the preceding King as anargument for why he should be elected (Schmidt 1987).

An important part of the institution of kingship is its connection to divinity. Inthis respect, the electoral monarchy of the German lands differed from thehereditary ones of France and England. In the Empire, the sacredness of theEmperor was a direct function of the fact that he was elected (Schubert 1977,p. 260ff). German scholarship calls this Wahlheiligkeit (holiness through election).In France, this connection was contained in the connection of a certain dynasty tothe divine. This difference was expressed in the greater importance attributed to theritual of anointment in France, whereby the King was sanctioned by and connectedto God (Schubert 1977, p. 264). In the Empire, the most important ritual was theelection.

The Emperor represented not only the empire as a polity, but a cosmologicalidea. As such it drew power not from the estates or the realm but from the abstractand sacrosanct idea of the empire. In the high Middle Ages, the elected Kings hadto go to Rome in order to be anointed by the pope, a practice that ended with Max-imilian I. in 1508 (Deutsche Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin and Heidel-berger Akademie der Wissenschaften 1977, pp. 530–531). The tradition of theEmperor’s holiness through election (Wahlheiligkeit) found echoes in political the-ory. In his defense of the Empire, Dante claimed that the German princes thatelected the Emperor in fact were mouthpieces of God (Alighieri 2007, Book III,Shaw 2007, pp. xxix–xxx). During the late Middle ages, Nicholas of Cusa illus-trated the ambiguity of the origins of the Emperor’s authority. In De conchordantiocatholica from 1483, he stated that the might of the Emperor rests on the will ofthe population of the empire. However, the office of the Emperor is derived fromGod and as Vicarus Christi he stands above all princes and peoples (Deutsche Ak-ademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin and Heidelberger Akademie der Wissenschaf-ten 1977).

I cannot here outline in full the sacral and symbolic dimensions of the empireor of the office of the Emperor, particularly as this has been dealt with elsewhere.We must note however that the two views of the holiness of the King created twodifferent kinds of polities. In hereditary monarchies, the King and his holiness werethe constitutive elements of the polity. In electoral monarchies, the polity itselfbecomes constitutive of the Kingship. Without election and naming, the Emperorcould not be invested with his office. Although the Emperor had substantial author-ity, it was bestowed not by the head of the church or transmitted by means of royalblood, but by the polity itself. The source of authority and the means of its trans-mission, as well as the possibilities of accountability, made the estates strongerpolitical subjects in the Empire than in France. In sum, although other sources ofauthority were necessary in order to become a King/Emperor, authority transferredthrough election was necessary. In order to interpret what this meant for theGerman realm and other electoral monarchies, we must first analyze who electedthe King/Emperor.

According to the most important German source of law in the thirteenthcentury, the Sachsenspeigel (‘mirror of the Saxons’), all princely members of thenobility had the right to elect the King (Eckhardt 1955). Gradually, this right wastransferred to six major princes known as the Kurfürsten. This title is usually

134 P. Haldén

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ann

a L

indh

-bib

liote

ket]

at 0

0:56

14

Sept

embe

r 20

17

translated into English as ‘Electors’ which omits their original function, namely tocall out the name of the candidate [Kuren]. The first step towards a narrowing ofthe electorate was taken in the 1220s when the Bishops of Trier, Mainz andCologne, the Count Palatinate of the Rhine, the Duke of Saxony and the Margraveof Brandenburg were granted the right be the first to call out, (kuren), the name ofthe elected candidate (Eckhardt 1955, p. 127). The right of election remained opento all ecclesiastical and worldly princes. Later, the right to announce the King wastransformed into the right to elect. In the election of 1257, the aforementionedprinces and the King of Bohemia appeared as electors (Kurfürsten), excluding allother princes.3

The Golden Bull of 1356 formalized the exclusive right of election by the sevenmajor princes and the principle of majority in the elections of the Emperor (Müller1964, pp. 31–35).4 It is unclear why the electorate decreased from all princes toonly six (Krieger and Gall 1992, pp. 69–71). The likely origins were practical. Theelection of 1256 took a very long time and it was difficult to assemble the princelynobility. As a solution to this logistical problem, the six princes who had the rightto announce the elected were commissioned with the task of election (Krieger andGall 1992, p. 70). From these ad hoc origins, the six electors clung to their rightand substantially institutionalized it over time. Even after the electors had beengiven the exclusive right to elect the Emperor, the other princes remained importantas a ‘public’ whose acceptance of the candidate was considered essential (Schubert1977, pp. 266, 269).

The interplay between authorization and accountability is central to representa-tion. In the electoral monarchies, it was exercised through an institution called‘electoral capitulations’, the promises that the candidate had to give to the elector-ate in order to be elected. In many European realms, the monarch had to swear anoath upon his coronation that usually contained promises to respect the libertiesand privileges of the nobility, uphold the laws and defend the realm. Coronationoaths also existed in countries whose monarchs were elected but the electoral capit-ulations were altogether different since they varied from monarch to monarch andwere negotiated with the electors.

The first formal electoral capitulation was that of Charles V. in 1519, but impor-tant predecessors exist. In 1400, the election of Ruprecht was accompanied by adocument that can be seen as a capitulation (Schubert 1977, p. 319). Anotherimportant predecessor was the common agreement between the Emperor-to-be andthe Electors in 1348. Schubert sees this document as an expression of commonresponsibility for the entire realm: ‘The character of this declaration of the will ofthe Electoral Princes is that of a programme for the reform of the realm. It showsthe development of a corporate consciousness of the community of the electoratethrough the responsibility for the entirety of the realm’ (Schubert 1977, p. 321).5

Already the oath taken by Sigismund in Aachen in 1414 was of a distinct politicalkind. As Schubert says, ‘it now seems clear that we must seek the precursors of anelectoral capitulation, the idea of binding the governing capacities of the elected tothe will of his electors already in the first half of the fifteenth century’. (Schubert1977, p. 322).6 After this binding promise had been spoken, the original coronationoath was sworn. These oaths, as well as their formalized successors, the electoralcapitulations, were intended to bind the elected to the will of his electors, or inmodern language, the representative to the represented (Schubert 1977, p. 326).7

Journal of Political Power 135

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ann

a L

indh

-bib

liote

ket]

at 0

0:56

14

Sept

embe

r 20

17

The electoral capitulations were dictated by the Electors who in this respectacted as representatives or speakers of the other princes who set the boundaries forhow an Emperor could act (Stollberg-Rilinger 2007, pp. 26–27). When they drewup each capitulation, the Electors looked back upon the reign of the previousEmperor and tried, by means of the capitulation, to rectify or avoid a repetition ofthe mistakes (from their point of view) of the previous monarch (Gotthard 2005,pp. 10–11). In this sense, the Electors exercised a kind of accountability, althoughwith the delay of one generation. In cases where the reigning Emperor tried to havehis successor appointed while he was still alive in order to secure the succession,the terms agreed on in the capitulation had the character of settling an account withthe reigning monarch.

The early capitulations were preceded by agreements between the candidate andindividual electors. However, in the late Middle Ages and early modern period, thecapitulations were negotiated with the electors as a collective (Schubert 1977,Fehrenbach 1984, pp. 451–452, Stollberg-Rilinger 2007, pp. 26–27). The GoldenBull of 1356 considered the election as a common action of all the Electors. In thelatter case, the character of the Electors as members and representatives of thepolity, as an entity larger than the sum of individual components, was morepronounced than in the earlier period (Schubert 1977, p. 319).

Of central importance to this article is the fact that the royal elections not onlyexpressed but in fact constituted a condition of mutual dependence. An actor hadto be elected and/or appointed in order to become King – despite the fact that thecandidate had so many strong resources of power at his disposal, for example hisroyal heritage and the power to brand actors unwilling to support him as traitors.The King needed the approval of the electors for his authority, which in turn meansthat we have to interpret the Electors as having authority that they could bestow.Conversely, according to medieval political thinking, the Electors and the otherprinces and nobles had to have a King not only to unify the realm but also in amore fundamental sense since he was the fountainhead of their authority. Without aKing, there could be no nobility and as Montesquieu later argued, there could beno King without a nobility (Krieger and Gall 1992, p. 106). This leads us to theinteresting conclusion that the King and electors (as well as the other princes) werethe sources of each others’ authority. A contemporary expression of this bond canbe found in the concepts of Wahlheiligkeit – the King’s holiness as dependent uponhis electoral status – and Königsnähe – the nobles’ need to be close to the King inorder to have authority. The two concepts complemented each other, not only bycreating a relation of mutual dependence of the two kinds of actors but in fact inthe sense that the two co-constituted each other.

Before analyzing the implications of the constitutive co-dependence and theenactment of the realm for theories of state formation in Europe, I will now analyzethe electoral monarchy in Sweden.

Sweden

Well into the fifteenth century, the sources are very scarce and imprecise and as aresult our knowledge of political relations and institutions in Sweden is vague.Originally, Sweden was a loose union of ‘lands’ (landskap) with their own laws,some of which referred to the election of Kings. From the thirteenth centuryonwards these lands became gradually more tightly linked (Schück 1985, 2005,

136 P. Haldén

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ann

a L

indh

-bib

liote

ket]

at 0

0:56

14

Sept

embe

r 20

17

Metcalf and Schück 1987, Schück et al. 1992, Péneau 2002). The first code of lawscommon to all Swedish lands was King Magnus Erikssons ‘Land law’ (landskap)from 1350. Its first paragraph states that Sweden was a country whose Kings areelected. As in Germany before the twelfth century, candidacy was not free. TheLand law stated that the King should be a man born in Sweden and ‘preferably theson of a king’ (Holmback and Wessen 1962, pp. 19–20, Wiktorsson 1989).However, it is unclear whether this was always adhered to in practice. The Kingwas to be elected by grandees, the so-called ‘men of the law’ as well as 12 otherrepresentatives from the core lands (Uppland, Westmanland, Dalecarlia, East andWest Gothia) at the Thing assembly outside Uppsala.

The Swedish polity was characterized by a dualism between nobles andnon-nobles. The former were defined as ‘the men of the realm’ and the latter as thecommonality (Allmoge or menighet). The institution of electoral monarchyembodied this dualism. The commons wielded considerable political influence. Forexample, the Land law stipulated that the deputation from each land sent to discusstaxes should contain six ‘freeborn men’ and ‘six men of the commonality’(Holmback and Wessen 1962, p. 10). Similarly, the coronation oath applied to all‘men living in the realm’. No new law could be introduced without the agreementof the allmoge, that is, the communitas of the realm as defined in the charter ofliberties from 1309 (Schück et al. 1992, p. 32). Finally, the Land law stressed theimportance of the consent and good will of the commoners being respected.8 Royalelections were often characterized by divisions between a first informal de factoelection made by the lords and a second formal but in fact only confirmative oneby the representatives of the non-nobles (Schück et al. 1992, p. 32). The electionof Karl Knutson Bonde as King in 1448 took place in two steps. First, an assemblyof 60–70 noble ‘men of the realm’ elected him. Only after this internal decisionwas made did the men of the lands perform the election at the ancient site outsideUppsala.

The Swedish lords created their authority by making two claims of representa-tion. On the one hand, they claimed to represent the realm by calling themselves‘men of Sweden’ (svenske men). On the other, they stated that they spoke on behalfof ‘the Men of the Realm in Sweden’. The two expressions referred to twodifferent facets of representation: making something abstract present, embodying,and acting in the place of another, standing in. They could be seen as strategies toclaim authority but also as strategies to enable collaboration with other groups bylinking up with them.

One principal institutional way that the interplay between authorization andaccountability was effectuated were the promises given by the King upon his elec-tion. As in the German case, the Kings-to-be had to give two kinds of promise: thefirst was the general coronation oath to safeguard traditional liberties and the rightto political participation of the estates (Schlyter and Collin 1869, p. 12ff). Thesecond was more specific electoral promises, which in Sweden were calledhandfästningar. According to Nordström, Swedish handfästningar were the samekind of action as the electoral capitulations that the Emperor had to make in orderto get elected (Nordström 1839, pp. 84–85). The combination of general and spe-cific promises was common in electoral monarchies. In the Polish–Lithuanian Com-monwealth, there were also two sets of promises. The first, Articui Henriciani,were general and ‘specified the powers of the King, the privileges of the nobility,and the basic rules of the system of administration’. The second, pacta conventa,

Journal of Political Power 137

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ann

a L

indh

-bib

liote

ket]

at 0

0:56

14

Sept

embe

r 20

17

were specific and changed from election to election. They ‘contained variouscommitments and certain pledges of particular Kings’ (Lerski et al. 1996, p. 416).In Sweden, the requirement to give handfästningar that guaranteed the traditionalliberties of the estates lived on even after Gustaf I Vasa made the crown hereditary.His son, John III, had to give handfästningar at his coronation in 1569, so didCharles IX in 1609 and Gustavus Adolphus in 1611 (Nordström 1839, pp. 86–87).Similar practices were current in neighboring Denmark in the seventeenth century(Geijer and Lundvall 1836, pp. 379–381).

A northern election ritual: the tour of Sweden

I argued above that we must understand symbolism and rituals as integral to pre-modern representation. A practice that was particular to Sweden was the King’sobligation to tour the provinces whose representatives had elected him to repeat theoath he had given in Uppsala (Schlyter and Collin 1869, p. §VI pp. 22–24).9 Thetour of the country (Eriksgata) that the new King made completed a cycle of com-munication of which the formal election was the first part. This cycle almostappears like a feedback loop. First representatives from each part of the realm trav-eled to Uppsala to bestow authority upon the candidate through the election. Thenthe King went back to the places that had sent representatives. The tour could beinterpreted in several ways. First, an interpretation stressing symbolic power, in theway that Habermas and Pitkin define it, would see the tour as a way for the Kingto exercise domination by means of an overawing symbolic display of majesty.Second, a perspective that sees politics as communication and bargaining might seethe tour as a way of providing assurances to people in the provinces that the Kingthey had elected would fulfill his end of a political bargain. While both containelements of truth, there is a third story to be told. This interpretation emphasizesthe constitutive effects of representation and an understanding of power as havingto do with creating political community at least as much as with exercising domi-nance. It also emphasizes the symbolic and ritual sides of pre-modern politics, butwithout necessarily equating them with power as domination and zero-sum gamesbut rather stressing their integrative effects.

The tour was certainly a way to communicate the oath of election to morepeople than those that were present at the election. In this way, a greater number ofpeople could be drawn into the relation between the electorate and King, whichconsisted of communication and the sharing of authority. In effect, more peoplebecame drawn into the realm. The meetings in the country in a way re-enacted orrepresented the election ceremony and thus made more people participants in therelation that was the cement of the realm. If we regard representation not as a rela-tion between two pre-existing actors or entities, we can conclude that the meetingsin the lands re-enacted not only the election ceremony but in fact made the Realmpresent in the lands. This in turn points towards what the Realm was: a commonbond, the act of acting in concert. The royal elections, including the tours, illustratethat a central aspect of royal power was creating and maintaining connectionsbetween different parts of the country and different social groups. In this way, theKing not only acted as the ‘supreme co-ordinator and regulator for the functionallydifferentiated figuration at large’ but he was in fact the person and institution thatcreated the ties that could be coordinated (Elias 1982, p. 163).

138 P. Haldén

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ann

a L

indh

-bib

liote

ket]

at 0

0:56

14

Sept

embe

r 20

17

The King’s tour of the chief lands of the country also transcended localism andisolation. We can assume that it was well known at the time that the King madethe tour of the country after his election. Consequently, the people of each landknew that the King would be visiting other lands and thus not only re-enacting theRealm in their land and the center but in all other lands. Hence, we can assumethat the tour broke, on a symbolic level, the idea that the realm consisted only ofbilateral communication between a center and a periphery. This relation illustrates achief difference between an empire and a state: While an empire consists of acenter and multiple peripheries that are kept in isolation from each other, a statemeans integrating the different parts of the country with each other. The two-partelection process where representatives traveled to a common arena and the Kinglater traveled out created an embryonic integration of the realm in a symbolic senseas well as by creating arenas for political communication and action common toelites from different parts of the country.

Representation as embedding

For the purposes of understanding the formation of social and political systems, weshould also note the unintended effects of the act of claiming to represent. Claimingto represent something, in our case ‘the realm’, may be effective in order to getauthority but it also increases your dependence on the thing or group you claim torepresent. This ‘move’ to get authority will bind an actor because of the claims hemakes. In order to get authority, your claim has to be credible, you have to assumesome obligations towards the people or the abstraction you claim to represent.Obligations towards an abstraction such as a ‘realm’ can take the form of having toremain loyal in times of internal or external war or assuming responsibility by per-forming administrative duties. I certainly do not mean to argue that suchobligations always were, or are, automatic and I do not mean to idealizepre-modern societies. History is too riddled with stories of hypocrisy andexploitation. Also, political arguments did not bind medieval actors in the exactsame way as they might bind modern actors since they did not take place in cul-tures where written records and mass media existed as they do today. My argumentis rather to highlight the processes of embedding and self-binding that resulted asunintended consequences of strategies to attain authority and power. Modernpolitical science in Germany often uses the term ‘Einbindung’ to describe Europeanintegration. This term carries connotations of both integration (Ein = in) andrestraint (Bindung = connection, tying up). It also captures fundamental traits of theprocess of polity formation.

As we saw above, the Swedish lords claimed to have authority by virtue ofrepresenting the realm as an abstract figure and as a collection of other groups.Similar discourses existed in the Empire. In one of them, electoral princes claimedto be ‘pillars of the Realm’ – solide bases imperii et columpne immobiles (Cohn2006, Heinig 2009). In another, the Empire was spoken of as a Realm with ‘headand members’ (Haupt und Glieder), the ‘head’ being the Emperor and the princesand estates ‘the members’. My point is that these discourses, symbols and argu-ments meant that the Realm was constructed as belonging to this group of actorsbut it also worked the other way round, they belonged to and were inseparablefrom the Realm; they could not constitute themselves as individual centers ofpower. The fact that other actors were indispensible parts of the political (although

Journal of Political Power 139

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ann

a L

indh

-bib

liote

ket]

at 0

0:56

14

Sept

embe

r 20

17

not material) power base of each actor was a powerful inoculation againstdisintegration. It also may explain why separatism, the attempt to declare indepen-dence as an autonomous unit, was so very rare in pre-modern Europe, despite thefrequent, bloody and crippling civil wars. It is well known that most rebellionswere directed against specific policies or Kings, not the realm itself. In other words,they took place within the realm not against it. If we do not take the integrity ofEuropean realms for granted but instead assume that disintegration would be aconstant possibility, then integrity must be explained. I believe that the politicalinterdependence created by representation goes a long way in explaining it.Material factors alone cannot explain this. There were frequent civil wars duringthe long period when neither Kings nor states as organizations had a monopoly ofviolence, or were strong enough to enforce stability and coerce would-beseparatists. Despite this, most realms held together and the answer must be soughtin political factors.

In sum, through the political and inter-subjective institutions of representationprincipal social actors and groups were constructed as existing in binding relationsto each other. This created durable relations and commitments that over timecoalesced into routinized and stable polities. This argument implies that generaltheories and accounts of state formation in history, as well as today, have to paymore attention to politics, understood as the inter-subjective and meaningfulrelations between important actors conveyed, contained and created througharguments, claims, narratives and rituals.

Political community, trust and collective power

How should we interpret the kind of political representation that we see in electoralmonarchies and estate assemblies of the Middle Ages? Several factors limited thedegree of accountability and distinguished it from modern representation. The samefactors also help us to determine precisely what medieval representation was andits social and political role. Two obvious differences are the limited electorate andthe low frequency of transfer of authority and accountability, since the election onlytook place once in the lifetime of a monarch. Crucial as these factors were, theywere more like differences in degree than in kind. The factors that have to do withpower are more important.

We have seen how representation in electoral monarchies was an important wayof transferring authority. An even more important element was the creation ofcollective power. Political representation in electoral monarchies is difficult tounderstand on the basis of theories of power that define power only as coercion orother ways of prevailing in a zero-sum contest. Instead, medieval representationbecomes intelligible when seen through theories of power as collaboration (Mann2012, pp. 6–10). Furthermore, the study of electoral monarchies highlights thefundamental role of the latter in the formation of political communities. Electoralmonarchies contained two kinds of political representation: (1) connecting powerfulgroups by means of authorization and accountability whereby all sides increasedtheir mutual dependence and (2) the creation of an abstract realm that authorizedthe powerholders and to which they were accountable. The two kinds were enactedin rituals, practices and political deals. Together they repeatedly constructed thegroup that together, and only together, can have collective power. In the words of

140 P. Haldén

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ann

a L

indh

-bib

liote

ket]

at 0

0:56

14

Sept

embe

r 20

17

Arendt: ‘Power springs up whenever people get together and act in concert, but itderives its legitimacy from the initial getting together rather than from any otheract that then may follow’ (Arendt 1972, p. 151).

Representation is constitutive of the realm as well as of the representatives andtheir social and political roles and positions. In addition, political representationwas a vehicle for cooperation and ‘concert’. Representative institutions and ritualsbecame the arenas for constructing, expressing and displaying trust; trust in thesense of social groups’ trust in each other but also society’s trust in itself (socialgroups’ trust in society), in its own cohesion, durability and legitimacy. Representa-tion is a mechanism that enables expansion of systems in terms of their extent andintensity.10 Luhmann argues that the more trusting relations there are in a socialsystem, the more alternatives for rational action are available (Luhmann 2000). Insystems-theoretical terms, representation allows systems to create durable structuralcouplings to other systems, thus creating larger conglomerations. It involved trans-fers of authority and it created collective power among the groups that took part inthe elections and deliberations. This was not distributional, zero-sum power but col-lective, positive sum power that grew as more people added to it (Österberg 1989).A concept like ‘concert’ or even ‘concord’ seems to fit this kind of social relationsas it denotes not only joint action or collaboration, but also a shared politicalvision/world view that enables collective undertakings. The common world viewwas cemented through representation as action as well as through symbolic ritualsand practices.

Interpreting medieval representation in electoral monarchies as a way to createpower as the ability to act in concert gives us a new perspective on the formationof political organization as a collective and coordinated process. Many theories ofstate formation from Hobbes to Charles Tilly to subsequent Realist theories operateon the basis of definitions of power as coercion. These theories reduce the state toan apparatus for coercion, accumulation and regulation. State formation is seen asdriven by the functional need for a monopoly of violence and/or a systemic needfor survival and conquest. As an alternative, the findings of this article allow us tooutline a political theory of not only ‘state formation’ but of the formation of poli-ties in general. This theory would build on Mann’s and Arendt’s ideas of collectivepower. In this optic, the state appears not as an instrument of coercion but as a col-lection of institutions for collaboration, negotiation and concord. Instead of coer-cion, one of the chief drivers of state formation is rather the need for collaborationand collective action. A cue in this respect can be taken from Hegel who talksabout a moral order (Sittliche Ordnung) in which the state is embedded and onwhich the state must be based.

This interpretation of political communities as a general category as well as thestate as a general subset is supported by a historical-comparative study of Europeanpolitical communities. A long tradition in political history has demonstrated theideational constructions of abstract realms with an existence independent of itsKings in all European realms (Bartelson 1995, pp. 97–100, Kantorowicz 1997,pp. 295, 298, 301, 304, 311).11 In England, this idea was expressed in the construc-tion of ‘the Crown’ that was independent of the King. The electoral monarchies ofnorthern and central Europe were very different from the hereditary monarchies inwestern Europe but they had a similar result, namely the creation of an abstractpolitical community.

Journal of Political Power 141

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ann

a L

indh

-bib

liote

ket]

at 0

0:56

14

Sept

embe

r 20

17

Why electoral monarchies?

There are many conceivable reasons why the emphasis on concord in these politicalcultures was so strong. The Holy Roman Empire and Poland–Lithuania were largerealms that consisted of very disparate parts.12 In the German case, a fundamentaldivision between Alemannians, Bavarians, Franks and Saxons has been visiblesince the early Middle Ages. Sweden was also large and in addition sparsely popu-lated and poor in resources. In all three realms, there was a need for concord andcollaboration in order to develop the country and to act effectively in European pol-itics. We also should recall that, despite their latter-day reputations, the HRE andPoland–Lithuania were quite effective and capable of large collective undertakings.We often view Poland–Lithuania as a crumbling eighteenth-century state but thatinterpretation ignores its successes against the Ottomans, the Teutonic Order andRussia. The exposed international position of all three electoral monarchies mayalso have contributed to their need for concord and collaboration. It is beyond thescope of this article to investigate that connection in detail but it suggests aninteresting reversal of Tilly’s theory of state formation: the exposed position ofthese realms in the European state system and its wars created polities stressingconcord, not coercion-intensive states. On a more detailed level, Tilly’s descriptionof Sweden and Poland–Lithuania as ‘coercion-intensive’ states must be re-evaluatedsince it misses the consensual character of their politics.

Conclusions

This article has general implications for state theory. The importance of creating anabstract idea that unites elite groups suggests that the combination of institutionaland ideational factors was crucial for the stability of early polities. Representativeinstitutions were important not only because of their role in assembling materialresources but also because of their role in creating an ideational and symbolicresource, namely community.

Interpreting representation as constitutive of the polity and its componentgroups sheds new light on historical forms of representation. If we see them onlyas institutions and arenas where pre-existing social groups transmitted authority andcommunication, we miss their crucial historical importance. Instead, we shouldinterpret historical forms of representation as practices that were constitutive of thepolity and its component social groups. In the societies studied in this article, repre-sentation shaped the idea of an abstract realm that could be represented and in theprocess constructed the political community that bound key groups together. Repre-sentation was also constitutive of the King and of the idea of kingship as well asthe nobility. In sum, representation was constitutive of the political community, itskey actors and their relations. Consequently, it is indispensible to understandingmedieval politics and the formation of political units in a longer time perspective.

This article also suggests future possibilities for research: (1) a first implicationis that the notion of collective power should be explored further in other historicalsettings. Investigations of integrative and constitutive effects of the forms of repre-sentation in England, France and Spain would be particularly valuable. (2) A sec-ond implication concerns the history of representation as it is presented in politicalscience. This article has demonstrated that representation as the transfer of authoritydid not originate with the democratic revolutions against absolutism in the

142 P. Haldén

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ann

a L

indh

-bib

liote

ket]

at 0

0:56

14

Sept

embe

r 20

17

eighteenth century. Instead, it is a much older factor that existed in polities thatwere decidedly undemocratic. Seeing that representation of this kind is not uniqueto the modern state or even modern nation state might lead to important conceptualinnovations for settings that do not correspond to the former, but urgently requirenew foundations for representation and trusting relations between key social groups.A prominent example would be the European Union as well as other transnationalpolitical networks.

Finally, this article has bearing on the problems of state building today: First,power is not only coercion but also the ability to act in concert. Consequently, it isprobably more important to build the capacity of fragile states to negotiate andbroker deals (to become the center of politics) than to emphasize and construct astate monopoly on violence. If outsiders have taken over the role of negotiatingand brokering deals, then the target state may be fatally weakened. Second,political community is more important than getting a formal apparatus, a set ofcoercive and redistributive institutions in place. Rather than looking at efficiency ofstate institutions in providing public goods, we should be looking for institutionsand ideas that create community. Rather than effective supply chains, any politicalcommunity needs ideas about that community that are believable and institutionsthat can foster them. How these insights from a neglected aspect of Europeanhistory could be translated into current policy is however beyond the scope of thisstudy.

AcknowledgementThe author wishes to thank Björn Tiällén and Mats Hallenberg of the Department ofHistory, University of Stockholm and Sofia Näsström for their comments on earlier drafts ofthis paper. Naturally, any mistakes or errors are the sole responsibility of the author.

Notes1. These two flows resemble Ullmann’s (2010) description of the ‘ascending’ and the

‘descending’ views in medieval political theory of the flows of authority in society.2. For performative language theory see (Austin and Urmson 1962; Searle 1969; Onuf

1998).3. Later, the king of Bohemia did not take part in the elections.4. Handwörterbuch zur deutschen Rechtsgeschichte p. 1284.5. My translation.6. My italics and my translation above.7. ‘… scheint nunmehr sicher zu sein, dass Ansätze einer Wahlkapitulation, der Gedanke

die Regierungsgewalt des Gewählten an den Willen seiner Wähler zu binden, bereits inder ersten hälfte des 15. Jahrhunderts gesucht werden müssen’.

8. Magnus Erikssons landslag Konunga Balk VII: ‘Syunde articulus er-at konunger aegherkirkinum ok klostrum-riddarum ok suenom-ok huars thera goz-hionum-ok alt gamaltfrelse-vskaddom kronunnae reth-at haldae ok all gamul suerikis lagh-thön sumalmoghin hauer m3 gopuilia ok samthykkio vidher takit …’.

9. If the king was unable to travel to Finland his oath would be repeated by the governorand the bishop of Åbo.

10. ‘[Trust] … makes the formation of systems possible and in return acquires strengthfrom them for increased, riskier reproduction’ (Luhmann 1995, p. 129).

11. Also Ullmann (2010, pp. 175–183) discusses the communitas regni.12. Concerning the political system of Poland-Lithuania see Davies (1981, pp. 321–372).

Journal of Political Power 143

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ann

a L

indh

-bib

liote

ket]

at 0

0:56

14

Sept

embe

r 20

17

Notes on contributorPeter Haldén works at the Swedish National Defence College. His recent publications are ANew Agenda for State-building: History, Context and Hybridity (edited with Roberg Egnell,Routledge 2013) and Stability without Statehood (Palgrave 2011). He researches fundamen-tal concepts of social theory, state formation, tribal societies and international politics.

References

Alighieri, D., 2007. Monarchy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Anderson, P., 1974. Lineages of the absolutist state. London: NLB.Ankersmit, F.R., 2002. Political representation. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.Arendt, H., 1972. On violence. In: H. Arendt, ed. Crises of the republic: lying in politics;

civil disobedience; on violence; thoughts on politics and revolution. New York: HarcourtBrace Jovanovich, 105–198.

Aretin, K.O., 1997. Das Alte Reich 1648–1806 [The old realm 1648–1806]. Stuttgart:Klett-Cotta.

Austin, J.L. and Urmson, J.O., 1962. How to do things with words. London: OxfordUniversity Press.

Bartelson, J., 1995. A genealogy of sovereignty. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Barudio, G., 1998. Der teutsche Krieg, 1618–1648 [The German War 1618–1648]. Berlin:

Siedler.Bisson, T.N., 2009. The crisis of the twelfth century: power, lordship, and the origins of

European government. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.Bladh, G. and Kuvaja, C., 2005. Från ett rike till två nationalstater [From one realm to two

nation-states]. In: G. Bladh and C. Kuvaja, eds. Dialog och särart: människor,samhällen och idéer från Gustav Vasa till nutid [Dialogue and character: people,societies and ideas from Gustavus Vasa to the present]. Svenska Litteratursällskapet iFinland: Helsingfors, 11–42.

Blickle, P., 1997. Resistance, representation and community. Oxford: Clarendon Press.Bosl, K. and Möckl, K., eds., 1977. Der moderne Parlamentarismus und seine Grundlagen

in der ständischen Representation: Beiträge des Symposiums der Bayerischen Akademieder Wissenschaften und der International Commission for Representative andParliamentary Institutions auf Schloss Reisensburg vom 20. bis 25 [Modernparliamentarism and its foundations in estate-based representation: Contributions to theSymposium of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences and the International Commission forRepresentative and Parliamentary Institutions at the Castle Reisenberg from April 20 to25]. April 1975. Berlin: Duncker und Humblot.

Cohn, H.J., 2006. The electors and imperial rule at the end of the fifteenth century. In:B.K.U. Weiler and S. MacLean, eds. Representations of power in medieval Germany800–1500. Turnhout: Brepols, 295–318.

Davies, N., 1981. God’s playground: a history of Poland. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Deutsche Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin and Heidelberger Akademie der

Wissenschaften [The German academy of sciences in Berlin and the Heidelbergacademy of sciences], 1977. Deutsches Rechtswörterbuch: Wörterbuch der älterendeutschen Rechtsprache [German legal dictionary: dictionary to the older German legallanguage]. Weimar: Böhlau.

Downing, B.M., 1988. Constitutionalism, warfare, and political change in early modernEurope. Theory and Society, 17 (1), 7–56.

Downing, B.M., 1989. Medieval origins of constitutional government in the West. Theoryand Society, 18 (2), 213–247.

Duchhardt, H., 2003. Europa am Vorabend der Moderne 1650–1800 [Europe on the eve ofthe modern 1650–1800]. Stuttgart: Eugen Ulmer.

Eckhardt, K.A., 1955. Das Landrecht des Sachsenspiegels [The land law of the mirror ofthe Saxons]. Göttingen: Musterschmidt-verlag.

Elias, N., 1982. The civilizing process. Oxford: B. Blackwell.

144 P. Haldén

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ann

a L

indh

-bib

liote

ket]

at 0

0:56

14

Sept

embe

r 20

17

Ertman, T., 1997. Birth of the leviathan: building states and regimes in medieval and earlymodern Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fehrenbach, E., 1984. Reich [Realm]. In: O. Brunner, ed. Geschichtliche Grundbegriffe:historisches Lexikon zur politisch- sozialen Sprache in Deutschland. Bd. 5 : Pro-Soz[Fundamental concepts of history: historical lexicon to the political-social language inGermany vol. 5]. Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta, 423–508.

Geijer, E.G. and Lundvall, C.J., 1836. Svenska folkets historia D. 3, Till K. Carl X Gustaf[The History of the Swedish People. Vol. 3 To Charles X Gustaf ]. Örebro: N.M. LindhsBoktryckeri.

Giddens, A., 1990. The consequences of modernity. Stanford, CA: Stanford UniversityPress.

Gotthard, A., 2005. Das Alte Reich 1495–1806 [The Old Realm 1495–1806]. Darmstadt:Wiss. Buchges.

Gramsci, A., 2010. Prison notebooks: three volume set. New York: Columbia UniversityPress.

Habermas, J., 1998. Borgerlig offentlighet kategorierna ‘privat’ och ‘offentligt’ i detmoderna samhallet [The structural transformation of the public sphere: an inquiry into acategory of bourgeois society]. Lund: Arkiv.

Hegel, G.W.F., 2007. (1798–1802). The German constitution. In: G.W.F. Hegel, ed. PoliticalWritings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 6–101.

Heinig, P.-J., 2009. Solide bases imperii et columpne immobiles? Die geistlichen Kurfürstenund der Reichsepiskopat um die Mitte des 14. Jahrhunderts [Solid bases of the empireand immobile columns? The secular electors and the imperial episcopacy in themid-fourteenth century]. In: U. Hohensee, M. Lawo, M. Lindner, M. Menzel, and O.B.Rader, eds. Die Goldene Bulle: Politik, Wahrnehmung, Rezeption [The Golden Bull:politics, perceptions, reception]. Berlin: Akademie-Verlag, 65–91.

Held, D., 1997. Democracy: from city-states to a cosmopolitan order? In: R.E. Goodin andP. Pettit, eds. Contemporary political philosophy: an anthology. Oxford: Blackwell,78–103.

Hintze, O., 1970. Typologie der ständischen Verwaltung des Abendlandes [Typology of theestate-based administration of the West]. In: G. Oestreich, ed. Staat und Verfassung:gesammelte Abhandlungen zur allgemeinen Verfassungsgeschichte [State and administra-tion: collected essays on general constitutional history]. Gottingen: Vandenhoeck &Ruprecht, 120–139.

Hintze, O., 1975. The historical essays of Otto Hintze. New York: Oxford University Press.Hobbes, T., 2008. Leviathan. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Holmback, A. and Wessen, E., 1962. Magnus Erikssons landslag [The land-law of Magnus

Eriksson]. Stockholm: Nord. bokh. (distr.).Jackson, P.T. and Nexon, D.H., 1999. Relations before states: substance, process and the

study of world politics. European Journal of International Relations, 5 (3), 291–332.Kantorowicz, E., 1997. The King’s two bodies: a study in mediaeval political theology.

Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.Koenigsberger, H.G., 1971. Estates and revolutions; essays in early modern European

history. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.Krieger, K.F. and Gall, L., 1992. Enzyklopadie deutscher Geschichte [Encyclopedia of

German history]. München: Oldenbourg.Latour, B., 1993. We have never been modern. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.Lerski, G.J., Wróbel, P. and Kozicki, R.J., 1996. Historical dictionary of Poland, 966–1945.

Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.Lipset, S.M., 1960. Political man: the social bases of politics. London: Heinemann.Luhmann, N., 1968. Vertrauen; ein Mechanismus der Reduktion sozialer Komplexität [Trust:

a mechanism for the reduction of social complexity]. Stuttgart: F. Enke.Luhmann, N., 1995. Social systems. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.Luhmann, N., 2000. Familiarity, confidence, trust: problems and alternatives. In: D. Gambetta,

ed. Trust: making and breaking cooperative relations, electronic edition. Department ofSociology, University of Oxford, chap. 6, 94–107. Available from: http://www.sociology.ox.ac.uk/papers/luhmann94-107.pdf

Lukes, S., 2005. Power: a radical view. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Journal of Political Power 145

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ann

a L

indh

-bib

liote

ket]

at 0

0:56

14

Sept

embe

r 20

17

Mann, M., 2012. The sources of social power, Vol. 1. Cambridge: Cambridge UniversityPress.

Manow, P. and Camiller, P., 2010. In the king’s shadow: the political anatomy of democraticrepresentation. Cambridge: Polity.

Metcalf, M.F. and Schück, H., eds., 1987. The Riksdag: a history of the SwedishParliament. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Mitteis, H., 1944. Die deutsche Königswahl: ihre Rechtsgrundlagen bis zur Goldenen Bulle[The German royal election: its legal foundations until the Golden Bull]. Brunn: RudolfM. Rohrer.

Moore, B., 1966. Social origins of dictatorship and democracy: lord and peasant in themaking of the modern world. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Müller, K., 1964. Die Goldene Bulle Kaiser Karls IV.: 1356 [The Golden Bull of EmperorCharles IV.: 1356]. Bern: Lang.

Nasstrom, S., 2011. Where is the representative turn going? European Journal of PoliticalTheory, 10 (4), 501–510.

Nederman, C.J., 2009. Lineages of European political thought: explorations along themedieval/modern divide from John of Salisbury to Hegel. Washington, DC: CatholicUniversity of America Press.

Nordström, J.J., 1839. Bidrag till den svenska samhällsförfattningens historia: efter de äldelagarna till sednare hälften af 17:de seklet [Contributions to the history of the Swedishsocial constitution: from the older laws to the latter half of the seventeenth century].Helsingfors: J.P. Franckell & Son.

Onuf, N.G., 1998. The republican legacy in international thought. Cambridge: CambridgeUniversity Press.

Österberg, E., 1989. Peasants and central power in early modern Sweden: conflict, compro-mise, political culture. Scandia, 55 (1), 73–95.

Péneau, C., 2002. Le roi élu: Les pouvoirs politiques et leurs représentations en Suède dumilieu du XIIIe siècle à la fin du XVe siècle [The elected king: the political powers andtheir representation in Sweden from the thirteenth century to the fifteenth]. Paris: Univ.de Sorbonne.

Pitkin, H.F., 1967. The concept of representation. Berkeley: University of California Press.Pocock, J.G.A., 1975. The Machiavellian moment: Florentine political thought and the

Atlantic republican tradition. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.Rokkan, S., et al., 1999. State formation, nation-building, and mass politics in Europe: the

theory of Stein Rokkan : based on his collected works. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Rustow, D.A., 1970. Transitions to democracy: toward a dynamic model. Comparative

Politics, 2 (3), 337–363.Schlyter, C.J. and Collin, H.S., 1869. Codex iuris communis Sueciae Christophorianus, cum

notis critics, variis lectionibus, glossario et indice nominum propriorum.: Konung Chris-toffers landslag [Christopher’s common law of Sweden, with critical notes, various lec-tures, glossary, and index of proper names: the land-law of King Christopher]. Lund:Berlingska boktryckeriet.

Schmidt, U., 1987. Königswahl und Thronfolge im 12. Jahrhundert [Royal elections andsuccession in the twelfth century]. Köln: Böhlau.

Schmidt, G., 1999. Geschichte des alten Reiches: Staat und Nation in der Frühen Neuzeit;1495–1806 [History of the old realm: state and nation in the early modern age;1495–1806]. München: C.H. Beck.

Schubert, E., 1977. Königswahl und Königtum im spätmittelalterlichen Reich. Zeitschrift fürhistorische Forschung, 77 (3), 257–338.

Schück, H., 1985. I Vadstena 16 augusti 1434 [In Vadstena August 16 1434]. HistoriskTidskrift, 105, 135–149.

Schück, H., 2005. Kyrka och rike: från folkungatid till vasatid [Church and realm: from theage of the Folkungs to the age of the Vasas]. Stockholm: Sällskapet Runica et Mediævalia.

Schück, H., Bengtsson, I., and Stjermquist, N., eds., 1992. Riksdagen genom tiderna [Theparliament through the ages]. 2nd ed. Stockholm: Parliament of Sweden.

Searle, J.R., 1969. Speech acts: an essay in the philosophy of language. London: CambridgeUniversity Press.

Shapiro, I., ed., 2009. Political representation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

146 P. Haldén

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Ann

a L

indh

-bib

liote

ket]

at 0

0:56

14

Sept

embe

r 20

17

Shaw, P., 2007. Introduction. In: P. Shaw, tran. Monarchy. Cambridge: CambridgeUniversity Press.

Skinner, Q., 1978. The foundations of modern political thought, Vol. 1. Cambridge:Cambridge University Press.

Skinner, Q., 1992. The Italian city-republics. In: J. Dunn, ed. Democracy: the unfinishedjourney, 508 BC to AD 1993. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 57–70.

Stollberg-Rilinger, B., 1999. Vormünder des Volkes?: Konzepte landständischer Repräsenta-tion in der Spätphase des Alten Reiches [Guardian of the people? Concepts ofprovincial-estate representation in the later stages of the old realm]. Berlin: Duncker &Humblot.

Stollberg-Rilinger, B., 2007. Das Heilige Römische Reich Deutscher Nation: vom Ende desMittelalters bis 1806 [The Holy Roman Empire of the German nation: from the end ofthe middle ages to 1806]. München: Beck.

Stollberg-Rilinger, B., 2008. Des Kaisers alte Kleider: Verfassungsgeschichte und Symbol-sprache des Alten Reiches [The Emperor’s old clothes: constitutional history andsymbolic language of the old realm]. München: C.H. Beck.

Tacitus, P.C., 2005. Germania [Germany]. Stockholm: Wahlström & Widstrand.Teschke, B., 2003. The myth of 1648: class, geopolitics, and the making of modern