Quotation markers as intertextual codes in electoral propaganda

Transcript of Quotation markers as intertextual codes in electoral propaganda

Quotation markers as intertextual codes inelectoral propaganda*

PNINA SHUKRUN-NAGAR

Abstract

This article explores the intertextual nature (as defined by Kristeva) of lin-

guistic markers used to denote quotations (quotation markers) in the 1999

Israeli televised electoral campaign. Three kinds of quotation markers were

identified: source markers (references, qualifiers), describing the source;

speech markers (lexical, graphical), attesting to speech production; and

circumstance markers, describing the context (time, place, participants,

background) in which the quotation was produced. It was found that, in ad-

dition to their overt role as references to the quotation, quotation markers

also encode the ideological and argumentative value attributed by the par-

ties to the quotations and their sources. Source markers serve to a‰liate the

sources with the positively regarded ‘‘we’’ group, to exclude them, or to es-

tablish them as neutral; speech and circumstance markers serve to a‰liate

quotations with the positively regarded ideological text of the party, to ex-

clude them, or to mark them as neutral. Moreover, these three markers

serve to reinforce the reliability of quotations that fulfill a corroborative

role. These values are encoded by the mere presence of the markers, as

well as by such devices as variation in the frequency of the markers, their

content, emotive connotations, grammatical forms, and incorporation in re-

curring patterns.

Keywords: intertextuality; electoral campaign; propaganda; covert per-

suasion; quotation markers.

1. Introduction

In this article, I discuss the rhetorical functions of quotation markers, i.e.,linguistic markers used to denote quotations. Three types of markers were

identified in the text studied here: source markers, relating to the identity

and qualities of the quotation source (such as: ‘‘Mayor of Jerusalem’’);

1860–7330/09/0029–0459 Text & Talk 29–4 (2009), pp. 459–480

Online 1860–7349 DOI 10.1515/TEXT.2009.024

6 Walter de Gruyter Brought to you by | Ben Gurion University of the NegevAuthenticated | 132.72.130.12

Download Date | 3/12/14 1:30 PM

speech markers, indicating the production of the speech event (‘‘told,’’

‘‘says’’), and circumstance markers, describing the circumstances in which

the quotation was produced (‘‘this week on television’’). I will argue that

quotation markers are used as a significant means of persuasion in the

televised electoral campaign. They function as intertextual elements in

the primary sense of the term according to Kristeva (1984 [1974]): in ad-

dition to their obvious linguistic role—indicating the quoted pre-text—they are also used as ideological and argumentative codes, transmitting

covert messages in reference to the quotation and to its source. This will

be shown in a corpus, comprising spoken and written Hebrew texts, of

the electoral broadcasts on Israeli television in 1999 on behalf of the two

major parties at the time: Likud and Israel Achat. The discussion is based

on an analysis of original examples, which are presented in semi-literal

translation into English.

2. Theoretical background

The discussion is inspired by Julia Kristeva’s theory of intertextuality

(Kristeva 1984 [1974], 1986), which posits the permutation of semiotic

units to linguistic ones. Kristeva was influenced by Bakhtin (1981, 1986)

who views language as a dialogic system whereby meanings are the prod-

uct of interactions between signs, speakers, and contexts (historical, cul-tural, social, ideological).

Accordingly, Kristeva refers to the linguistic text, primarily poetic, as a

meeting place between textual organization and external cultural units.

She argues that all the semiotic meanings, including psychological ones,

are encoded covertly in the linguistic sign, and therefore sees its polysemy

as semiotic polyvalence (Kristeva 1984 [1974]: 59–60, 1980: 36–37; see

also Allen 2000: 35–36; Roudiez 1980: 15)

The concept of intertextuality was often reduced, to Kristeva’s dismay,to overt marking of transposition between lingual texts (Kristeva 1984

[1974]: 59; see also Allen 2000: 101; Pfister 1991: 210). However, many

researchers have remained faithful to Kristeva’s theory and demonstrated

this through varied links between concrete texts and discourse (Frow

1990; Ri¤aterre 1984) or concrete pre-texts (Genette 1997; Hatim and

Mason 1990).

In this paper, I apply Kristeva’s notion of intertextuality to my analysis

of three quotation markers found in the televised electoral campaign:source markers and speech markers, whose linguistic roles have been dis-

cussed elsewhere, and circumstance markers. I will show that in rhetorical

discourse various meanings encoded in the quotation markers make them

460 Pnina Shukrun-Nagar

Brought to you by | Ben Gurion University of the NegevAuthenticated | 132.72.130.12

Download Date | 3/12/14 1:30 PM

profoundly intertextual, i.e., they implicitly position the pre-text in rela-

tion to the text, both ideologically and argumentatively. For this purpose

I will discuss the meaning of the mere presence (as opposed to absence) of

the markers and the semiotic meanings inherent in the frequency of these

markers, their content, emotive connotations, intonation, grammatical

forms, incorporation in recurring patterns, etc. (Sections 6–8).

3. The corpus

The analysis draws on the Israeli televised electoral campaign, broadcast

six days a week on national television between the dates 24 April 1999

and 14 May 1999. The examined texts relate to the two major Israeli po-

litical parties: Likud, then the ruling party, led by Benjamin Netanyahu

(prime minister from 1996 to 1999), and Israel Achat, the largest opposi-

tion party, led by Ehud Barak (prime minister from 1999 to 2001). Polit-ically, the Likud was perceived as a moderate right-wing party, whereas

Israel Achat was considered a moderate left-wing party. Both parties

tended to quote each other, particularly their leaders.

The electoral campaign was planned by advertising companies in coop-

eration with the politicians appointed as the directors of the election

headquarters. Each broadcast lasts 30 minutes and generally consists of

approximately 10–15 textual units that are easily distinguishable by sub-

title naming the addressing party at the beginning and the end. Everybroadcast contains various segments on such topics as security, econom-

ics, social welfare, and education.

The texts discussed are in spoken and written Hebrew. The written lan-

guage was at times an exact transcription of speech (subtitles), and at

times just slogans or emphasized portions. In addition, both visual means

(photos, clips) and audio means (songs, music) are used.

A typical broadcast often includes a background narration and pro-

ceeds as follows: an announcer presents a claim in favor of the addressingparty or against its opponents. His oral presentation is accompanied by a

written version and relevant photos may be seen on the screen. The claim

is then reinforced by a member of the party, usually its leader, or a public

figure (economist, writer, security specialist). Simultaneously, subtitles,

slogans, and clips are shown on the screen. Most politicians appear sitting

behind a desk in their o‰ce, the national flag in the background, while

public figures are usually seen sitting in a television studio. In addition,

in order to reinforce the same claim, ordinary people are interviewed indi¤erent settings: on the street, in the market, at a university campus, etc.

In the framework of the distinction between text and pre-text, I con-

sider all of the above as text, since they were created specifically for the

Quotation markers as intertextual codes 461

Brought to you by | Ben Gurion University of the NegevAuthenticated | 132.72.130.12

Download Date | 3/12/14 1:30 PM

televised campaign and are presented as part of it. The broadcasts also

include clips and previous recordings from other places such as parlia-

ment meetings, conferences, and political conventions. I consider these

segments as pre-texts, and the words of the speakers as quotations.

The article discusses a random sample of 20 broadcasts, during which

47 di¤erent propositions (abstract content units) were quoted from 19 dif-

ferent sources. In most cases the same proposition was quoted severaltimes in the same segment (in direct speech, indirect speech, recorded

speech, etc.). As already mentioned (Section 1), the texts were translated

verbatim into English. I will discuss all semantic, pragmatic, or other de-

viations from the original text.

4. Description of the quotation markers

4.1. Source markers

Source markers presenting the quotation’s source include references and

qualifiers (Halliday and Hasan 1976; Weizman 1998):

References indicating the source’s identity: full name, surname, name (of

parties, newspapers), and unique role (‘‘the Syrian Foreign Minister’’).

Qualifiers describing various characteristics of the source: residence, a‰li-

ation group (parties, population groups), and status (‘‘one of the leadingeconomists’’).

4.2. Speech markers

Speech markers indicating the production of quotations include:

Lexical markers: nominals (‘‘a silly declaration’’), verbs (‘‘said’’), and pres-

ent participles (‘‘shout’’) from the semantic field of saying. In Hebrew the

present tense is conveyed by the present participle, a verbal adjective thatshares characteristics of both verbs and nouns. In electoral discourse the

distinction between the present participle and past tense verbs has signifi-

cant rhetorical importance (Sections 6–7).

Graphical elements: double quotation marks; colons. Naturally these

markers are only used when the quotation is written on the screen.

4.3. Circumstance markers

Circumstance markers describing the context of the quotation include:

Temporal markers: dates; time frames (‘‘this week’’).

Locative markers regarding production or broadcast location.

462 Pnina Shukrun-Nagar

Brought to you by | Ben Gurion University of the NegevAuthenticated | 132.72.130.12

Download Date | 3/12/14 1:30 PM

Participant markers relating to addressees; presence of others.

Background markers indicating the wide contexts (‘‘when the students

went out to demonstrate, demanding fair tuition fees . . . ’’).

4.4. Frequency of quotation markers

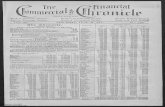

Table 1 provides the frequency of quotation markers.

Table 1 shows that the most frequent markers are source references (in

81% of the quotations). Source qualifiers appear in just a small number of

quotations (11%) where, however, their frequency is relatively high (nine

markers in five quotations). Circumstance markers, especially temporaland to a lesser degree locative and background, are also relatively fre-

quent (43%, 17%, and 15%, respectively). In contrast, most quotations

lack speech markers altogether, whereas some have several. This means

that the production of quotations is either linguistically unmarked or

emphasized.

It should be noted that, in a televised campaign, linguistic marking of

quotations is not always necessary; most quotations may be represented

as originally produced by merely showing a video, playing a recording,or, in case of a written source (a newspaper), showing a photograph on

the screen. Therefore, the mere presence of linguistic marking is fre-

quently considered a means of highlighting.

Table 1. Frequency of quotation markers

Type of

markers

No. of

markers

No. of quotations

including markers

Percentage of

quotations including

markers1 ðn ¼ 47Þ

Source References 61 38 81%

Qualifiers 9 5 11%

Total 70 38 81%

Speech Lexical 17 12 26%

Graphical 18 9 19%

Total 35 14 30%

Circumstance Temporal 22 20 43%

Locative 18 8 17%

Background 8 7 15%

Participant 5 4 8%

Total 53 31 66%

1 In the two right columns the concluding (total) num. are not a precise conclusion of the

data since some of the quotations include a number of markers of the same kind. For in-

stance: a full name and unique role are both used as references of the same source (‘Ehud

Olmert, Mayor of Jerusalem’).

Quotation markers as intertextual codes 463

Brought to you by | Ben Gurion University of the NegevAuthenticated | 132.72.130.12

Download Date | 3/12/14 1:30 PM

5. Source and quotation types

I found three characteristics relevant for the use of quotation markers: the

political a‰liation of the source, the ideological stance of the quotation,

and the argumentative status of the quotation.

5.1. Political a‰liation of the source

The sources quoted in the corpus are of three types:

Representatives of the addressing party (for instance: Ehud Barak, leader

of Israel Achat, in its text).Opponents from the opposing party (Ehud Barak in a Likud text).

External sources that are not a‰liated with any party (Bill Clinton in a

Likud text). It should be noted that only politicians from the Likud and

Israel Achat are quoted in texts of these parties.

In the broadcasts source markers signify all kinds of speaker switching,

including switches within a given text. Since they are not specific to quo-

tations and are not even used in all of them, source markers do not indi-

cate an intertextual shift to a pre-text.I will show (Sections 6–7) that the parties use source markers to adopt

a source as part of their positively regarded ‘‘we’’ group, to exclude it

from the negatively regarded ‘‘they’’ group, or to establish it as neutral.

5.2. Ideological stance of the quotations

The quotations in the corpus are also of three types:

Supportive in relation to the ideology of the addressing party. Each party

presents itself as acting in the interests of the Jewish people and the State

of Israel, therefore supporting it is presented as positive.

Hostile in relation to the ideology of the addressing party and, therefore,

presented as negative for the people and the state.

Ostensibly neutral in relation to the ideology of the addressing partythough actually supporting. All the quotations from newspapers, and

only these, are presented as without any underlying ideology—theoreti-

cally reliable testimonies of reality.

This distinction, which reflects the parties’ perspective on the ideologi-

cal content of the quotations, is encoded in the use of speech and circum-

stance markers, making them inherently intertextual as well. Speech and

circumstance markers, contrary to source markers, are used only in rela-

tion to quotations, therefore necessarily signifying an intertextual shift:speech markers do this by highlighting a quote from a pre-text; circum-

stance markers achieve the same e¤ect by highlighting the di¤erence or

‘‘otherness’’ of the pre-text with respect to the text. As we will see (Sec-

464 Pnina Shukrun-Nagar

Brought to you by | Ben Gurion University of the NegevAuthenticated | 132.72.130.12

Download Date | 3/12/14 1:30 PM

tions 6–7), use of these markers to signify a partition between linguistic

texts simultaneously emphasizes a partition between ideologies.

5.3. Argumentative status of the quotations

All the quotations in the corpus serve to support the claim that the

addressing party is better for the citizens. Nevertheless, some of the quo-

tations are textually linked to an explicit claim and fulfill a role of corrob-

orative data (Toulmin 1958). In order to give the impression that a quo-

tation reinforces the claim’s validity, the parties use specific speech and

circumstance markers. The covert use of some markers to emphasize a

corroborative function is also an intertextual characteristic of these signs.

6. Quotation marking

I found that the ideological stance of the quotation (supportive/neutral/

hostile) has the most significant e¤ect on the linguistic marking of thequotation; I will therefore focus on this criterion. In addition, I will exam-

ine how linguistic marking is influenced by the reciprocal relations of

the ideological stance of the quotation, the party a‰liation of the source

(representative/external/hostile), and the corroborative status of some

quotations.

6.1. Supportive quotations

Quotations that ideologically support the addressing party were produced

by all three types of sources: representative, external, opposing. As a rule,

supportive quotations are characterized by few, if any, speech and cir-

cumstance markers. As explained (Section 5.2), both types of markers

form a partition between the quoting text and the quotation, albeit di¤er-

ently: speech markers highlight the quotation act, thereby emphasizingthe intertextual shift from text to pre-text; in contrast, circumstance

markers highlight the unique characteristics of the speech event, thereby

emphasizing the otherness of the pre-text with regard to the text.

When neither the intertextual shift nor the ‘‘otherness’’ of the pre-text

are linguistically marked, the distinction between text and pre-text be-

comes blurred, which is likely to cause the impression that the quotation

is in fact an integral part of the addressing party’s text. This occurs in the

superficial sense of text, linguistically, and more importantly—in thedeeper sense—ideologically (see Kristeva 1986: 36; Payne 1993: 178).

As opposed to speech and circumstance markers, source markers that

do not signify an intertextual shift (Section 5.1) are used in over half

Quotation markers as intertextual codes 465

Brought to you by | Ben Gurion University of the NegevAuthenticated | 132.72.130.12

Download Date | 3/12/14 1:30 PM

of the supportive quotations, often with high frequency. The presence or

absence of source marking and its nature are mainly influenced by the po-

litical a‰liation of the source and the argumentative importance of the

quotation.

According to the Iconic Principle (Kirtchuk 2000), the length of the lin-

guistic marker a¤ects the way in which it is perceived. Therefore, a full

name is more emotive than a surname alone and multiple references areperceived as more emotive than a single reference (Perelman 1983: 35).

Thus when the source is a candidate for the post of prime minister or, al-

ternatively, an opponent speaking in favor of the addressing party, he is

usually marked several times by his full name and highlighted by visual

means, too (photos, clips). In contrast, when the sources are external or

are representatives that are not party leaders, their quotations share an

absence of source markers, probably in order to avoid highlighting them

at the expense of the parties’ candidates.Corroborative supportive quotations are unique in two characteriza-

tions that reinforce their argumentative force: first, sources are marked

by role, status, and a‰liation group, which present them as authorities;

second, quoting is marked only by the participle ‘‘says’’, which does not

create a distinction in time or ideology between pre-text and text. Among

its relevant interpretations are vagueness in time and repetition of the

action (Fleischmann 1990; Nir and Roeh 1987; Sakita 2002; Saring

1998; Tobin 1988, 1989).To sum up, supportive quotations are usually characterized by non-

marking of the speech and the circumstances and by marking the source

only in selected quotations. The absence of speech and circumstance

markers contributes to the impression that the quotation is part of the

party’s linguistic text and, more importantly, of its ideological text. The

parties may use speech markers to increase the argumentative force of

the quotation, but without discernibly distancing it from their text.

Source markings, that do not indicate an intertextual shift, are used onlyif the parties are interested in highlighting the source.

6.2. Neutral quotations

As noted (Section 5.2), all the quotations from newspapers are presented

in the campaign as neutral reflections of the truth. This has obvious impli-

cations for quotation marking, which consists of a single source referenceby name and temporal markers with the newspaper cutting shown on the

screen. All these create an impression of minimal intervention by the par-

ties and increase the impression of neutrality of the newspapers.

466 Pnina Shukrun-Nagar

Brought to you by | Ben Gurion University of the NegevAuthenticated | 132.72.130.12

Download Date | 3/12/14 1:30 PM

As explained (Section 5.2), the use of speech and circumstance markers

is likely to create a distinction between text and pre-text. Although tem-

poral markers indicate the ‘‘otherness’’ of the quotation, they are neces-

sary to testify to its credibility, thereby enabling the addressing party to

rely on its content. In Israel it is customary to refer to a newspaper by

name and exact date of publication. Only this marking is likely to be per-

ceived as a full obligation to the credibility of the quotation. In some ofthe ‘‘neutral’’ quotations, the date of publication is designated within a

broad time frame, ranging from ‘‘last week’’ to ‘‘during the last three

years.’’ Obviously, the wider the time frame, the more likely it is to be

performing a primarily emotional role rather than an argumentative one.

As expected, whenever quotations are corroborative the parties take

care to indicate the date of each quoted newspaper. This, along with the

newspaper’s name, enables a transfer of authority from quoter to quoted

(Perelman 1983: 109), i.e., from the biased parties to the newspapers, pre-sented as neutral.

In summary, in ‘‘neutral’’ quotations the parties use a uniform o‰cial

marking of the source: a single reference of the newspaper’s name and

temporal markers. They thereby create the impression that the quotations

are credible, neutral, and worthy of being considered a testimony to the

just nature of the addressing party’s ideological text. Exact publication

dates of quoted newspapers are presented consistently only when quota-

tion credibility is important for its corroborative function.

6.3. Hostile quotations

Quotations hostile to the ideology of the addressing party were produced

by two types of sources: external and opponent. All these quotations are

characterized by multiple and varied markers of all kinds. The frequent

use of multiple speech and circumstance markers emphasizes the separa-tion between text and quotation. Most of the markers are unique to hos-

tile quotations: extremely emotive adjectives, past tense verbs, participant

markers, background markers, etc. Source markers in hostile quotations

are also unique in their particularly high frequency (as many as four per

quotation) and the use of surnames for reference.

When the source is an opponent, markers of all kinds are more fre-

quent and more emotive, due to the special importance of excluding the

source from the ‘‘we’’ group of the addressing party and to the ideologicalseparation between their texts. Multiple markers (especially temporal and

locative) also characterize all the corroborative hostile quotations in

order to reinforce their argumentative force.

Quotation markers as intertextual codes 467

Brought to you by | Ben Gurion University of the NegevAuthenticated | 132.72.130.12

Download Date | 3/12/14 1:30 PM

As a rule, external sources (such as the Syrian foreign minister) are not

independently significant in the electoral discourse. Rather, their impor-

tance lies in their relations with the political opponents. This has two im-

plications. First, external sources are marked in a rather functional way:

those that are well-known are referred to only by surname or are not

mentioned at all, and those that are seldom or never part of the politi-

cal discourse are referred to by role or full name. Second, there is a dis-cernible attempt to link the negatively presented contents of the external

sources’ quotations with the political opponents, rather than with the

sources. In other words, the quotations of external sources serve predom-

inantly to distance the political opponents (and not the sources) from the

‘‘we’’ group of the party and to form a boundary between the ideological

texts of the various sides.

For example, the Likud quoted comedienne Tiki Dayan speaking

against Likud supporters in an arrogant way: ‘‘We’re talking about an-other nation . . . the lowest of the low, ri¤ra¤ . . . ’’. While she, the source,

was mentioned only once, Ehud Barak, the leader of the opposing party,

was mentioned in the context of this quotation several times by circum-

stance markers:

These are the arrogant insulting words of Tiki Dayan at a convention supporting

Barak, in the presence of Barak . . . Barak was there; Barak clapped; Barak

laughed; Barak did not say a word, a man like this cannot be Prime Minister.

In this way, the party is creating a most negative image of Barak as iden-

tified with the discriminative content of the quotation.

Multiple references to opponents whose quotations are hostile find ex-

pression both in the number of quotations in which they are executed and

in the number of markers per quotation. The primary contribution of the

markers is in emphasizing the opponent’s identity in order to condemn

him. The opponents are marked by full names or by surnames alone. In

both cases the parties construct negative emotionality of the references bytextual links (Shukrun 1998; Shukrun-Nagar 2001) and by extralinguistic

means (music, photos, etc.). Nevertheless, there is a di¤erence between

full names and surnames in the degree of emphasis on the source, and

since surnames mark only sources whose quotations are hostile, they

could be seen as expressing disrespect for the source as a public figure.

With regard to speech markers, there is a noticeable use of verbs in the

past tense, especially when the source is an opponent. The use of the past

tense emphasizes the intertextual shift from the text to the pre-text, there-by highlighting the partition between them. Another noticeable character-

istic common to hostile quotations whose sources are opponents is fre-

quent use of negative lexical markers (verbs and nominals) to define the

468 Pnina Shukrun-Nagar

Brought to you by | Ben Gurion University of the NegevAuthenticated | 132.72.130.12

Download Date | 3/12/14 1:30 PM

contents of the quotations: ‘‘a silly declaration,’’ ‘‘shouting,’’ ‘‘these

words are shocking,’’ etc. The use of negative speech markers in relation

to opponents’ quotations was also found in Israeli newspapers and radio

news (Nir and Roeh 1987, 1992), serving to reflect ideological distance

from ‘‘the enemies of the State’’ or ‘‘socially di¤erent or abnormal, who

can legitimately be doubted’’ (1987: 24).

Even use of the inherently neutral verb ‘‘said’’ contributes to increasingthe negative emotionality of the hostile quotations. In addition to its past

tense, the verb is contained in the question ‘‘who said . . . ?’’, for instance:

‘‘Who said: ‘I do not express dovish views because I want to win the elec-

tion’?’’. This question is a complex one (Copi 1977), as it contains the pre-

supposition that the quoted content was indeed voiced by someone (obvi-

ously Ehud Barak, as his photo is shown on the screen concurrent to the

question). Moreover, in Israel the question ‘‘who said’’ constitutes a pop-

ular intertextual pattern in school lessons and quizzes evoking commonknowledge. Therefore the genre shift inherent in this formulaic use also

contributes to emotionality.

Another interesting finding is the rhetorical exploitation of the par-

ticiple ‘‘says’’ in opponents’ hostile quotations fulfilling a corroborative

role. This marker doesn’t contribute to the distinction between text and

pre-text in terms of tense. Nonetheless, it is repeated several times while

re-broadcasting the quotation, thus helping to create the impression that

the quoted content is repeated by the source. Naturally this has a poten-tial to increase negative emotionality of both the quotation and its source.

Another unique characteristic of hostile quotations is the use of quota-

tion marks and colons in subtitles on the initiative of the addressing

party, and not just as part of a photographed cutting shown on screen.

Hostile quotations uttered by opponents possess a typically high fre-

quency of circumstance markers, especially when they are corroborative.

A minority of the markers are participant and background markers, which

primarily increase the negative emotionality of the quotations, therebyemphasizing the partition between text and pre-text. However, most of

the markers are temporal and locative; their primary contribution is to re-

inforce credibility of the quotations. This is crucial since one may suspect

that the hostile quotations attributed by the parties to their opponents

might be fictitious or no longer relevant. Temporal markers denote the

exact date of origination of the quotation, or a short time frame (‘‘this

week,’’ ‘‘in the previous week’’). As explained (Section 6.2), the contribu-

tion of time frames to credibility is less than that of a precise date.All the corroborative quotations also include locative markers, such as

‘‘a personal meeting with Gideon Levy’’ (a program on which Ehud

Barak appeared). A combination of locative and temporal markers

Quotation markers as intertextual codes 469

Brought to you by | Ben Gurion University of the NegevAuthenticated | 132.72.130.12

Download Date | 3/12/14 1:30 PM

(particularly exact dates), while showing the source speaking, may be

considered evidence of maximal commitment to credibility of the address-

ing parties.

Especially interesting are multiple markers referring to the broadcast

location, particularly the repetition of the marker ‘‘on television’’ twice

and even four times in relation to the same quotation. This marker is

part of an intertextual pattern ‘‘Netanyahu on television’’ which is fre-quently used in the Israel Achat campaign. For example: ‘‘according to

Netanyahu on television, our economic situation is wonderful . . . but in

reality, two hundred and thirty thousand people are unemployed . . . ’’.

Because of the repetition of the marker on television in relation to many

quotations of Netanyahu, and because of the consistent contrast between

this marker and ‘‘in reality,’’ a claim emerges in the campaign whereby

everything Netanyahu says on television is refuted. Forming a generaliza-

tion by means of multiple examples is explained by Perelman (1983: 86)in the following way: first, the speech maker presents a number of irrefut-

able examples intended to validate the proposed rule; then, once the rule

is confirmed, the examples later presented are based on that rule. The

damage to the credibility of Netanyahu’s television appearances had sig-

nificant rhetorical importance because of his previous image as a media

magician.

Generally speaking, hostile quotations are characterized by a high fre-

quency of source, speech, and circumstance markers used to encode theaddressing party’s severe reservations about the quotations and their

sources. Most of the markers are unique in the high degree of emotional-

ity due to their content or manner of use. However, it has been found that

the frequency of markers, their grammatical forms, and their semantic

components were directly influenced by the political a‰liation of the

source and by a corroborative role of the quotations: opponents were dis-

cernibly more emotionally distanced from the ‘‘we’’ group than the exter-

nal sources; and corroborative quotations are unique in using temporaland locative markers to increase credibility.

The following section is devoted to the analysis of two case studies,

illustrating the distinction and claims made so far.

7. Textual discussion

7.1. Text A

As explained (segment 3) the broadcast texts are composed of spoken seg-

ments, written segments, visual means, and audio means. Table 2 de-

470 Pnina Shukrun-Nagar

Brought to you by | Ben Gurion University of the NegevAuthenticated | 132.72.130.12

Download Date | 3/12/14 1:30 PM

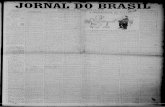

Table 2. Text A

Speaker Spoken text Written text Audio means Visual means

Anouncer The Netanyahu government

is stuck on every issue.

The Netanyahu government

is stuck on every issue

Netanyahu in his seat at the

Israeli parliament. The chairs

around him are empty.Therefore, Netanyahu is

trying to divide the country

that is unified on the issue

of Jerusalem.

Netanyahu is dividing the

country that is unified on

the issue of Jerusalem

Ehud Olmert I have no doubt (videotaped) Olmert speaking in a classroom

of Russian immigrants.that Ehud Barak is dedicated

to the unity (videotaped)

Ehud Olmert Likud, Mayor

of Jerusalem

and integrity of Jerusalem,

the capital of Israel

(spoken)

Pleasant View of East Jerusalem

Ehud Barak united under our sovereignty,

the eternal capital of Israel,

period. (videotaped)

Cheering and

clapping

Background Barak giving a speech in East

Jerusalem.

Ehud Olmert and he will not participate

(spoken)

Music Photo of Barak giving a

speech.

in any activity that will

compromise the unity of

Jerusalem as the capital of

Israel. (videotaped)

Olmert speaking in a classroom

of Russian immigrants.

Ehud Barak Israel united around a united

Jerusalem, no one will

succeed in splitting the

nation on this issue.

(spoken)

Barak in di¤erent locations in

Jerusalem.

Qu

ota

tion

ma

rkers

as

intertex

tua

lco

des

47

1

Brought to you by | Ben Gurion U

niversity of the Negev

Authenticated | 132.72.130.12D

ownload D

ate | 3/12/14 1:30 PM

scribes an Israel Achat text, broadcast between 27 April and 2 May 1999.

Each line indicates a time unit.

This segment is composed of an unknown announcer’s words and of

two quotations: one of Ehud Barak, then leader of the addressing party,

Israel Achat, and the other of Ehud Olmert, at the time member of the

rival Likud party.

There are two types of articulated text: spoken—which is heard, but thespeaker is not seen, and videotaped—where the speaker is both heard and

seen. The announcer’s text is always spoken, while quoted texts may be-

long to either type. Transcriptions of the articulated texts utilize punctua-

tion marks to reflect breaks in the speech: a period ( . ) represents a full

stop, a semi-colon ( ; ) is for a medium-length break, and a comma ( , )

for a short break. The written text is copied from the screen exactly as

originally presented, including punctuation marks.

The segment refers to Barak’s commitment to the unity of Jerusalem.While the entire city of Jerusalem is the capital of Israel, the political sta-

tus of its eastern part is controversial. As sites holy to Jews and Muslims

(as well as Christians) are situated in East Jerusalem, both Arabs and

Israelis claim it as their own. The Israeli left-wing, and particularly the

radical left, comprises a mainly secular population that is willing to give

East Jerusalem to the Palestinians. The political right-wingers, in con-

trast, see Jerusalem as the religious, spiritual, and national-historical cen-

ter of the Jewish people and cannot imagine giving it up. Since 1996, theunity of the city has become a major issue in Israeli electoral discourse;

the right-wing Likud is not ‘‘suspected’’ of possibly agreeing to give up

East Jerusalem; however, part of the Israeli public thinks that the moder-

ate left-wing Israel Achat may be willing to do so. The issue is often

brought up by the Likud, and the above segment is a reaction to that.

The segment begins with the claim verbalized by the announcer, repre-

senting Israel Achat: ‘‘The Netanyahu government is stuck on every issue.

Therefore, Netanyahu is trying to divide the country that is unified on theissue of Jerusalem.’’ A slightly (but rhetorically) di¤erent phrasing of this

claim is shown on the screen, originally in red. By these means Netan-

yahu is marked as a rival of the ‘‘we’’ group which, according to the

text, includes not only the addressing party, but the entire nation. Netan-

yahu’s name is attributed with negative emotionality by textual links to

negative signs (‘‘stuck,’’ ‘‘to divide/dividing’’) and by nonverbal means:

the claim written on the screen in red, and Netanyahu seen sitting alone

in the parliament.The rest of the segment focuses on proving that Israel Achat does not

plan to divide Jerusalem. For this purpose quotations from Olmert and

Barak are split and presented alternately. Both quotations support the

472 Pnina Shukrun-Nagar

Brought to you by | Ben Gurion University of the NegevAuthenticated | 132.72.130.12

Download Date | 3/12/14 1:30 PM

party ideology and are used to maintain the claim that Barak is com-

mitted to the unity of Jerusalem. However, it will be demonstrated that,

argumentatively, Olmert’s words have a higher refutation value vis-a-vis

Netanyahu’s accusations.

Both quotes support the ideology of the addressing party and are pre-

sented as an integral part of its contemporary text: there are no speech

markers that would indicate an intertextual shift, nor circumstancemarkers that would indicate the distinction between pre-text and text.

This gives the impression that the quotations and the announcer’s words

are all one text.

Di¤erent means are used to integrate Barak’s and Olmert’s quotations:

by dividing each of the quotations into two parts and presenting them al-

ternately (Olmert–Barak–Olmert–Barak), the e¤ect is achieved of inte-

gration, in both content and ideology. On a syntactic and grammatical

level, the quotes appear to be one unit: the second half of Olmert’s quota-tion begins with the word ‘‘and,’’ which originally connected both parts

of his sentence. However, in this segment one might believe that Olmert

is continuing the thought expressed previously by Barak. This impression

of textual unity between the two quotations is supported by extralinguis-

tic means too: background music continues from the beginning of

Olmert’s words until the end of Barak’s; Olmert’s words are accompanied

by clips of Barak or views of East Jerusalem. On this background, imme-

diately following Olmert’s talk, Barak is seen giving a speech.As noted (Section 3), Barak is the Israel Achat candidate for the post of

prime minister. His quotations in most of its texts are accompanied by a

repetition of his full name. We may surmise that the absence of his name

in this particular segment possibly serves to enhance the semblance of in-

tegration between his text and Olmert’s. However, Barak is presented in

an emotionally positive light by exhibiting him with a view of Jerusalem

in the background and by playing cheering and clapping sounds as he

speaks.From the viewpoint of the addressing party, promoting Olmert is

somewhat problematic: his words contribute much toward refuting Netan-

yahu’s repetitive claim that Barak will divide Jerusalem; they therefore

obviously belong to the text of the ‘‘we’’ group. However, he is a member

of the opposing Likud party headed by Netanyahu, and so, in principle,

belongs to ‘‘they.’’ The marker ‘‘Ehud Olmert, Mayor of Jerusalem’’

written in black is the solution to this contradiction: in the written elec-

toral discourse a politician’s full name in blue is used to create positiveemotionality, while the surname alone in red promotes negative emotion-

ality; whenever members of the opposing group produce supportive quo-

tations, as in the present case, the quotation source is marked by the full

Quotation markers as intertextual codes 473

Brought to you by | Ben Gurion University of the NegevAuthenticated | 132.72.130.12

Download Date | 3/12/14 1:30 PM

name written in black. In this way, moderate positive emotionality is

achieved.

Both the qualifiers ‘‘Likud ’’ and ‘‘mayor of Jerusalem’’ increase the

argumentative force of the quote. The marker ‘‘mayor of Jerusalem’’ val-

idates Olmert as a knowledgeable authority on all city matters, thereby

reinforcing the argumentative status of the quotation (Volman 1990: 60;

Perelman 1983: 79; Copi 1977: 87). The marker ‘‘Likud ’’ clears Olmertfrom any suspicion that his support of Barak stems from nonobjective

considerations. Probably in order to avoid damage to the necessary posi-

tive emotionality of Likud in this co-text, the government, in which the

Likud is a central member, is called ‘‘the Netanyahu Government’’ and

not ‘‘the Likud Government.’’ Thus, the negative emotionality of ‘‘stuck’’

(‘‘The Netanyahu government is stuck’’) adheres only to Netanyahu.

While the captions relating to Olmert are black (neutral), Netanyahu’s

captions are red (negative emotionality). Distinguishing between themon an emotional and ideological level although they are members of the

same party helps Israel Achat to show a connection between Olmert and

Barak, and to present their quotations as belonging to the same ideologi-

cal text, opposed to Netanyahu’s.

In summary, the markers used to denote Olmert as well as the lack of

markers for Barak serve to connect between these politicians and their

views: while Israel Achat ascribes Olmert to the ‘‘they’’ group, it does

not damage his positive image and even acknowledges his public statusin order to strengthen the argumentative status of his words. In addition,

it espouses his text and merges it with that of Barak as an ideological

statement regarding Barak’s commitment to a unified Jerusalem.

7.2. Text B

The text in Table 3, broadcast on 1 and 2 May 1999, also belongs to theIsrael Achat campaign. The text criticizes Netanyahu, then prime minister

on behalf of the Likud Party.

According to this text Netanyahu deceived the lower class population

by giving needy children 60,000 new computers on camera, but taking

them back once the cameras were turned o¤. This section is one of a se-

ries of attempts by Israel Achat to present Netanyahu as a media magi-

cian whose statements and promises do not hold water.

Three propositions are quoted in the text. The first, according to whichNetanyahu brought computers for children in Kiryat Malachi, was first

transmitted as indirect speech by the announcer (‘‘he’d brought them

computers’’) and, later on, by Netanyahu himself, photographed as he

474 Pnina Shukrun-Nagar

Brought to you by | Ben Gurion University of the NegevAuthenticated | 132.72.130.12

Download Date | 3/12/14 1:30 PM

Table 3. Text B

Speaker Spoken text Written text Vocal means Visual means

Announcer Last week, Netanyahu told the

parents and children in Kiryat

Malachi,1 that he’d brought them

computers

Intonation of

an anecdote

Within a frame: a photograph of

Netanyahu making a speech.

Netanyahu Another sixty thousand computers

that’s, a revolution! (videotaped)

Within a frame: Netanyahu

making a speech.

Announcer He was photographed with them

and was even moved

Intonation of

an anecdote

Netanyahu and his wife standing

beside an Ethiopian immigrant

child as he operates a computer.2

Netanyahu I tell you, every time we come,

Sara3 and I stand there,

ah . . . ah . . . tears in our eyes!

(videotaped)

Within a frame: Netanyahu

making a speech.

Announcer But the Ma’ariv newspaper4 reveals

the truth: The computers were

brought for the camera shoot

and were removed directly after

the event.

The computers were placed in

the Education Center for

Netanyahu’s visit and removed

after the event. (in cutting)

Ma’ariv 29.4.99

Has your child received a computer

from the Netanyahu government?

Has your child received a

computer?

A photograph of Netanyahu

Can one believe anything

Netanyahu says?

Can one believe Netanyahu?

Do you want four more years? Want 4 more years?

1 The town of Kiryat Malachi visited by Netanyahu is identified with economic distress.2 The Ethiopian immigrants are identified with social-educational disadvantage.3 Sara is Benjamin Netanyahu’s wife. The couple often complains about their negative image in the Israeli media.4 Ma’ariv is one of the three largest daily newspapers in Israel.

Qu

ota

tion

ma

rkers

as

intertex

tua

lco

des

47

5

Brought to you by | Ben Gurion U

niversity of the Negev

Authenticated | 132.72.130.12D

ownload D

ate | 3/12/14 1:30 PM

spoke (‘‘Another sixty thousand computers, that’s a revolution!’’). The

second proposition, predominantly the emotional response of Netanyahu

and his wife when giving the computers, was transmitted once by Netan-

yahu himself (‘‘I tell you, every time we come, Sara and I stand there,

ah . . . ah . . . tears in our eyes!’’). The third proposition is quoted from the

Ma’ariv newspaper and transmitted in direct speech by the announcer

(‘‘The computers were brought for the camera shoot and were removeddirectly after the event’’) and by simultaneous presentation of the quoted

newspaper cutting on screen (‘‘The computers were placed in the Educa-

tion Center for Netanyahu’s visit and removed after the event’’). We will

see below that damage to Netanyahu’s public image was caused not only

by the quotation’s content, but by all quotation markers included in the

text.

As the Likud candidate for the post of prime minister, Netanyahu is the

major opponent of Israel Achat, which thus has an obvious interest to dis-tance itself from him and from any of his ostensibly negative quotes.

Ma’ariv newspaper, on the other hand, has no part in the political strug-

gle, and the quote from it actually strengthens Israel Achat’s claim.

Therefore, the party is expected to embrace both the source and the quo-

tation. However, as explained earlier (Section 6.2), the argumentative

strength of quotes from newspapers derives from their neutral image,

and it is in the party’s best interest to maintain this image.

Netanyahu is marked by surname only, a marker that potentially mayshow minimal respect for the speaker. This is similar to all other oppo-

nents whose quotations are hostile, and di¤erent from those whose quota-

tions are supportive (i.e., Olmert in the previous discussion). In compari-

son, Ma’ariv is mentioned twice and is even supported by the title

‘‘newspaper,’’ though all Israelis know it well. By this the party signifies

the importance awarded to its character and establishes its important

argumentative status.

As explained (Section 6.3), the partition between text and pre-text ismost significant when the sources are opponents and their quotations are

hostile. Israel Achat uses the lexical marker ‘‘told’’ to refute Netanyahu’s

words. The past tense of the verb distances the quotation from the quot-

ing text with respect to time. Moreover, the Hebrew original verb siper,

translated here as ‘‘told,’’ is far more emotive: it specifically denotes ‘‘tell-

ing stories’’ (including lying), thus implying that the content of the quota-

tion could well be fictitious (Nir and Roeh 1987: 26). This impression is

reinforced by the fairytale-like intonation used by the announcer to pres-ent Netanyahu’s quotations. Naturally, this contributes to the construc-

tion of negative emotionality not only of the quotation but also of

Netanyahu himself.

476 Pnina Shukrun-Nagar

Brought to you by | Ben Gurion University of the NegevAuthenticated | 132.72.130.12

Download Date | 3/12/14 1:30 PM

As mentioned above, the quotation from Ma’ariv was intended to re-

fute Netanyahu’s quotations. Israel Achat uses the participle ‘‘reveals’’ to

establish the credibility of Ma’ariv. This marker implies that the content

of the quotation is true and secret (Weizman 1982: 134).1 The noun

‘‘truth’’ (‘‘reveals the truth’’) naturally reinforces the credibility of the

newspaper and its quotation. The positive emotive connotation and the

present time of the markers create the impression of minimal partition be-tween pre-text and text.

As explained (Section 6.2), recording the name of the newspaper

together with the publication date (‘‘29.4.99’’) is likely to be perceived in

Israel as a full obligation to the credibility of the quotation, and therefore

is used whenever the quotations are corroborative. Here this factor is ex-

tremely important in establishing the claims against Netanyahu. Natu-

rally, a photograph of the quoted cuttings on the screen is also a contri-

buting factor.While Israel Achat uses only a date when referring to the quote from

the newspaper, it uses various circumstance markers when referring to

Netanyahu’s quote: temporal (‘‘last week’’), locative (‘‘in Kiryat Mala-

chi’’), addressees (‘‘parents and children’’), and background (‘‘he was

photographed with them, and was even moved’’). All these are character-

ized by low levels of accuracy, and could have been presented more spe-

cifically. However, this quality actually enables the party to present the

content of these quotes as fabricated, as it correlates to what is consideredacceptable in the narrative genre. In other words, the markers of Netan-

yahu’s quotes emphasize the otherness of the pre-texts as compared to

the texts and serve as a partition between them. This is accentuated by

extralinguistic means too: when Netanyahu speaks, his photograph does

not fill the screen. Rather, it appears inside a frame—a story within a

story, an extraneous character within the text of the addressing party.

In summary, an analysis of the text clearly shows that Israel Achat uti-

lizes di¤erent markers to mark the two sources and their quotes. Themarkers used in relation to the opponent Netanyahu and his hostile quo-

tations reflect the distance and the disagreement of the addressing party

with them. In contrast, markers relating to Ma’ariv and its quotation are

used to establish a neutral image of the newspaper and therefore to en-

hance the argumentative strength of the quotation.

8. Conclusion

This research has revealed that in the broadcasts of the Israeli electoral

campaign, quotation markers not only indicate a pre-text but also fulfill

Quotation markers as intertextual codes 477

Brought to you by | Ben Gurion University of the NegevAuthenticated | 132.72.130.12

Download Date | 3/12/14 1:30 PM

an important rhetorical role—a covert coding of the party’s position vis-

a-vis the sources and the quotations: source markers serve to a‰liate the

source with the ‘‘we’’ group, to exclude it, or to establish it as neutral;

speech and circumstance markers serve to a‰liate the quotation with the

ideological text of the addressing party, to exclude it, or to mark it as

neutral. Markers of all types are also used to increase the credibility of

quotations in corroborative status.I perceive the double functioning of quotations markers, on a linguistic

level as well as on a semiotic level, as evidence for intertextuality in elec-

toral discourse. Naturally, the ideological and argumentative meanings

are inherent in the semantic components and the emotive connotations

of the markers. However, it was found that these meanings are also en-

coded in other discursive means, including the mere presence of linguistic

marking, the frequency of the markers, their length (full names versus

surnames), their grammatical forms (past tense verbs versus participles),their insertion in recurring intertextual patterns, and their textual links.

As argued, the qualitative and quantitative findings presented here shed

light on covert means of persuasion in the Israeli rhetorical discourse,

and further support Kristeva’s (1984 [1974]) view that intertextuality

serves to encode semiotic meanings in linguistic signs.

Notes

* This article is based on my doctoral dissertation ‘‘Intertextuality in the Electoral Dis-

course on Israeli TV: Linguistic Features and Rhetorical Functions’’ (Shukrun-Nagar

2003). I am grateful to my two advisors, Prof. Elda Weizman from Bar Ilan University

and Dr. Roni Henkin from Ben-Gurion University, for their substantial contribution to

the research and to this article. I am also grateful to Prof. Yishai Tobin for reading this

article and o¤ering his comments and to Tzipi Parnassa from the Ben Gurion University

computational center for implementing the sample of the corpus.

1. According to Grice’s (1975) concept, this constitutes a conventional implicature.

References

Allen, G. 2000. Intertextuality. London & New York: Routledge.

Bakhtin, M. M. 1981. In M. Holquist (ed.), C. Emerson & M. Holquist (trans.), The dialogic

imagination: Four essays by M. M. Bakhtin. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Bakhtin, M. M. 1986. In C. Emerson & M. Holquist (eds.), V. W. McGee (trans.), Speech

genres and other late essays. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Copi, I. M. 1977. In M. Dascal (ed.), H. Rotem (trans.), Introduction to logic. Tel-Aviv:

Yakhdav (Hebrew).

Fleischman, S. 1990. Tense and narrativity. Texas: University of Texas Press.

Frow, J. 1990. Intertextuality and ontology. In J. Still & M. Worton (eds.), Intertextuality:

Theories and practices, 45–55. Manchester & New York: Manchester University Press.

478 Pnina Shukrun-Nagar

Brought to you by | Ben Gurion University of the NegevAuthenticated | 132.72.130.12

Download Date | 3/12/14 1:30 PM

Genette, G. 1997. In C. Newman & C. Doubinsky (trans.), Palimpsests: Literature in the sec-

ond degree. Lincoln & London: University of Nebraska Press.

Grice, P. H. 1975. Logic and conversation. In P. Cole & J. L. Morgan (eds.), Syntax and

semantics 3: Speech acts, 41–58. New York: Academic Press.

Halliday, M. A. K. & R. Hasan. 1976. Cohesion in English. London: Longman.

Hatim, B. & I. Mason. 1990. Discourse and the translator. London & New York: Longman.

Kirtchuk, P. I. 2000. Iconicity and some of its manifestations in Hebrew. In Y. Tobin (ed.),

Societatis Linguisticae Europaeae Sodalicium Israelense: Proceedings of the Sixteenth

Annual Meetings, 13–26. Beer Sheva: Ben Gurion University Press (Hebrew).

Kristeva, J. 1980. In L. S. Roudiez (ed.), T. Gora, A. Jardine & L. S. Roudiez (trans.),

Desire in language: A semiotic approach to literature and art. New York: Columbia Uni-

versity Press.

Kristeva, J. 1984 [1974]. In L. S. Roudiez (ed.), M. Waller (trans.), Revolution in poetic lan-

guage. New York: Columbia University Press.

Kristeva, J. 1986. Word, dialogue and novel. In T. Moi (ed.), M. Waller (trans.), The

Kristeva reader, 34–61. New York: Columbia University Press.

Nir, R. & I. Roeh. 1987. Verbs of saying in the radio news. Hebrew Linguistics (a Journal

for Hebrew Descriptive. Computational and Applied Linguistics) 25. 19–29 (Hebrew).

Nir, R. & I. Roeh. 1992. Speech presentation of news in the Israeli press. In U. Ornan,

G. Toury & R. Ben-Shahar (eds.), Hebrew: A living language (Studies on the Language

in Social and Cultural Contexts), 188–210 (Hebrew).

Payne, M. 1993. Reading theory: An introduction to Lacan, Derrida and Kristeva. Oxford &

Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

Perelman, C. 1983. In J. Ur (trans.), The realm of rhetoric. Jerusalem: Magness (The

Hebrew University Press) (Hebrew).

Pfister, M. 1991. How postmodern is intertextuality? In H. F. Plett (ed.), Intertextuality,

207–224. Berlin & New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

Ri¤aterre, M. 1984. Intertextual representation: On mimesis as interpretive discourse. Criti-

cal Inquiry 11(1). 141–162.

Roudiez, L. S. 1980. Introduction. In J. Kristeva (author), L. S. Roudiez (ed.), T. Gora, A.

Jardine & L. S. Roudiez (trans.), Desire in language: A semiotic approach to literature and

art. New York: Columbia University Press.

Sakita, T. I. 2002. Reporting discourse, tense, and cognition. Amsterdam & Boston: Elsevier.

Saring, D. 1998. Audiovisual rhetoric, propaganda and culture: Studying the electoral pro-

paganda in the Israeli television, 1996. Israel: Bar-Ilan University Ph.D. dissertation

(Hebrew).

Shukrun, P. 1998. Election discourse on Israeli TV (May 1996): Building emotive connota-

tions through the use of textual links. Israel: Ben Gurion University MA thesis (Hebrew).

Shukrun-Nagar, P. 2001. Building emotive connotations through the use of textual links in

the election discourse. Hebrew Linguistics 49. 57–70 (Hebrew).

Shukrun-Nagar, P. 2003. Intertextuality in the election discourse on Israeli TV: Linguistic

features and rhetorical functions. Israel: Ben Gurion University Ph.D. dissertation,

(Hebrew).

Tobin, Y. 1988. Modern Hebrew tense: A study of objective temporal and subjective spatial

and perceptual relations. In H. Vater & V. Ehrich (eds.), Temporalsemantik: Beitrage zur

Linguistik der Zeitreferenz [Temporal semantics: Studies in the linguistics of time] (Lin-

guistische Arbeiten Series 201), 52–81. Tubingen: Niemeyer.

Tobin, Y. 1989. Space, time and point-of-view in the Modern Hebrew verb. In Y. Tobin

(ed.), From sign to text: A semiotic view of communication, 61–89. Amsterdam & Philadel-

phia: John Benjamins.

Quotation markers as intertextual codes 479

Brought to you by | Ben Gurion University of the NegevAuthenticated | 132.72.130.12

Download Date | 3/12/14 1:30 PM

Toulmin, S. E. 1958. The uses of argument. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Volman, M. 1990. Demagogy and rhetoric. Tel-Aviv: Papirus (Tel-Aviv University Press)

(Hebrew).

Weizman, E. 1982. Information processing in the language of newspapers by ‘‘normal’’

readers and translators. In S. Blum-Kulka, Y. Tobin & R. Nir (eds.), Studies in discourse

analysis, 117–143. Jerusalem: Academon (Hebrew).

Weizman, E. 1998. True or false? Direct speech in the daily press, Hebrew Linguistics

(a Journal for Hebrew Descriptive, Computational and Applied Linguistics) 43. 29–42

(Hebrew).

Dr. Pnina Shukrun-Nagar received her Ph.D. summa cum laude in 2003 from Ben-Gurion

University of the Negev in Israel, where she is now a lecturer in the Department of Hebrew

Language. Her primary fields of research are semantics and pragmatics, focusing on conno-

tations and the interpretation of implied meanings. She currently explores argumentative dis-

course, especially political texts (electoral campaigns and speeches) and mass media texts

(articles in the press). Address for correspondence: Department of Hebrew Language, Ben-

Gurion University of the Negev, Beer-Sheva, Israel [email protected].

480 Pnina Shukrun-Nagar

Brought to you by | Ben Gurion University of the NegevAuthenticated | 132.72.130.12

Download Date | 3/12/14 1:30 PM