Qualification as a Proxy for the Competence of the Migrant Teacher

Transcript of Qualification as a Proxy for the Competence of the Migrant Teacher

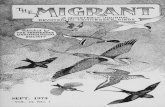

New s l e t te r

Inside This issue of IICBA Newsletter features international migration of teachers, which has been taking place for many decades or more, but has not attracted enough attention of education policy makers in Africa. This is partly because we do not know the full extent of this phenomenon, and partly because it is believed that migrant teachers comprise of very small fraction of national teaching force in Africa and therefore it is not considered as a priority area. In addition, sometimes asking the nationality of a teacher is perceived to be very sensitive, and some teachers migrate through unofficial channels, and in such cases, information on migrant teachers does not appear in national statistics.

Although the issue of teacher migration is not yet high on the policy agenda in Africa, especially compared to migration of health workers and engineers, migrant teachers have in fact been playing an important role in Africa. For example, since the beginning of the 20th century, Indian teachers have been well known in Ethiopia, particularly in math and science. Even today, a large number of Indian professors teach in Ethiopian universities. Ethiopia also recruits hundreds of Nigerian university instructors. This indicates that Ethiopia has been facing a shortage of qualified teachers, especially in certain subjects, and it has been willing to offer an incentive to attract foreign teachers.

At the global level, some studies show that both countries which send and receive migrant teachers often face a problem of teacher shortage. Receiving countries resort to international recruitment because they cannot meet the domestic demand for teacher. Sending countries may protest that international recruitment is “poaching” of teachers who are

trained by sending countries, which will further exacerbate their teacher shortage. Nevertheless, given the time needed for teacher training and the supply has to meet the pace of the demand, international recruitment has been a common practice.

In this issue, we present five articles on international teacher migration focusing on different aspects. The first article begins with the African Union’s response to the

challenges of migration and development in Africa, followed by UNESCO and IICBA’s responses to this issue, particularly on supply, quality and ethical recruitment of international migrant teachers, and concludes with proposed cooperation among development partners.

The second article, presented by Education International (EI), discusses the rights of migrant teachers and how teacher unions and major international organizations have been faced with this challenge. EI is further planning to develop a Teacher Migration and Mobility Campaign and to create a Task Force to lead this initiative.

In the third article, the author discusses the evolution of methods to recognize the competence of migrant teachers, including qualifications, qualifications frameworks, International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED), and transferability of teacher qualifications in the Commonwealth. Highlighting the limitation of these instruments, the article underlines the need for better understanding of skills of migrant teachers by evaluating not only past learning, but also current and potential competence.

The fourth article summarizes the review of the implementation of the Commonwealth Teacher Recruitment Protocol, based on the extensive study through interviews from different stakeholders about their experiences which confirms the need for more effective advocacy of this important instrument, and presents 10 practical questions for teachers who are considering working abroad.

The final article is a case study of migration of South African teachers to the UK. Analyzing the demographics of the migrant teachers, the study demonstrates different characteristics of migrant teachers by race and age, reasons for migration and experience of these different groups, and methods of recruitment.

We hope that these articles will provide some insights for policymakers, teachers and other stakeholders working on teacher issues, and contribute to African governments’ efforts in developing effective policies related to training, development and recruitment of teachers from a global perspective.

Arnaldo Nhavoto

Director, UNESCO-IICBA

Teacher Migration

UNESCO IICBA Newsletter Vol. 12 No. 2, December, 2010

2 IICBA, International Migra-tion of Teachers: Sup-ply, Quality, and Ethical Recruitment

4 Teacher Unions Scale up Measures to Defend the Rights of Migrant Teachers

5 Qualification as a Proxy for the Competence of the Migrant Teacher

6 Teachers, Ask 10 Ques-tions Before Teaching Abroad

8 South Africa Joins the Global Teacherhood

9 News IN BRIEF

www.unesco-iicba.org

Bi-annual Newslet ter in Engl ish, French and Portuguese

CBAInternational Institute for Capacity Building in Africa

International Institute for Capacity Building in Africa

Vol. 12. No. 2December, 2010

Page 2 UNESCO IICBA Newsletter Vol. 12 No. 2 December, 2010

African Union’s response to migration and education

Although teacher migration has not been a major education policy issue, overall migration and development issues are high on the policy agenda globally, particularly for Africa. Responding to the challenges that Africa faces in regard to irregular migration, trafficking, brain drain, migrant right, HIV and AIDS and related issues, the Council of Ministers of the Organization of African Unity (OAU) adopted the decision in 2001 to: (1) develop a strategic framework for migration policy in Africa to integrate migration issues in national and regional agenda; (2) strengthen intra-regional and inter-regional cooperation, and (3) create a conducive environment to facilitate the participation of migrants in the development of their own countries.4

In the area of education and workforce, the African Union recognizes the need for effective intervention at the continental level, stating that

“in order to maximize the skills of African professionals and promote viable socio-economic development at national and regional level, it is imperative that States adopt a proactive approach by replacing barriers towards migration with measures that effectively manage the movement of migrant labor between Sovereign State borders…. Investing in the development of human resources (including reversing the brain drain is one of the priority areas), and an essential requirement for African development through partnerships between government, civil society and the international community… (African Union, 2006, page 9).”5

Lack of information on migrant teachers

Teachers are migrating often within the regions or to neighbouring countries where standards of living is slightly higher than the origin country. Inter-regional migration is more difficult for poor countries because they do not have means to do so, but this form also exists, such as teachers migrating from South Africa to the UK. Some countries are actively recruiting and relying on migrant teachers to meet their increasing teacher demands. This has been done formally through governments, informally through private recruiters, or in some cases, migrant teachers rely on family or friends as a sponsor and they look for a job after they migrate. Some studies reveal that migrant teachers are not treated well in destination countries due to the difficulty in recognizing their qualification and lack of understanding of the rights and obligations of teachers. All these cases are reported in selected country case studies, but there is no international

comparable data on teacher migration flows, quality assurance and recognition of their qualifications, and ethical recruitment of these teachers at the global level.

Why is migration of teachers an important policy issue?

There are three main reasons why this topic is important. First is related to teacher supply. If some countries are over-producing teachers, can they help under-producing countries? Then who should be responsible for teacher training investment and who benefits from them? It would be useful to explore the possibility to establish in each country a system for collecting, analyzing and maintaining data, integrating information of relevance to both source and destination countries to support future managed migration. The map below shows different teacher needs at the global level. The highest needs are concentrated in Africa, but some countries have enough teaching force and in some cases, are overproducing teachers.

IICBA, International Migration of Teachers: Supply, Quality, and Ethical Recruitment

Akemi Yonemura, Ed.D. Program Specialist, UNESCO-IICBA

Map 1. Countries facing a teacher gap, 2008

Severe teacher gapModerate teacher gapMinor teacher gapSufficient number of teachersNo data available

Source: UNESCO Institute for Statistics. (2010). INFORMATION SHEET No. 5. The Global Demand for Primary Teachers – 2010 Update.

4 African Union (2006). The migration policy framework for Africa.5 African Union (2006). The migration policy framework for Africa.

UNESCO IICBA Newsletter Vol. 12 No. 2 December, 2010 Page 3

And in order to illustrate the situation in Africa, the following table6 shows the countries with primary teacher gaps in the continent (2008), and their need for annual percentage of increase.

Table 1. Countries with Primary Teacher Gaps in Africa, 20087

Source: UNESCO Institute for Statistics. (2010). INFORMATION SHEET No. 5. The Global Demand for Primary Teachers – 2010 Update.

The second reason is related to quality – how is quality assurance and recognition of qualifications of migrant teachers handled? Often skilled migrants are not employed at the level of their qualification in destination countries. It is also difficult to compare educational training systems and licensing requirements in different cultural, social, and economic settings. Some countries have fears of using the lowest common denominator, which would lead to the lowering of professional and academic standards, or fears linked to the transfer of regulatory authority and obligations to foreign counterparts who may operate under different standards8. Some schemes facilitating labor mobility focus on the assessment of competency rather than recognition of qualification. It is important to examine if the migrant teachers’ qualifications and competence are recognized in a fair and transparent manner.

Thirdly, it is important to ensure ethical recruitment of migrant teachers, considering the rights and obligations of migrant teachers in destination countries, and possibly those of return migrant teachers in the country of origin. Commonwealth Protocol on Teacher Recruitment is recognized as a good instrument, which could facilitate the movement of teachers from surplus to underserved countries, while supporting professional registration systems both within and across countries for long-term career development and skill utilization.9 The African Union has been trying to develop a similar protocol targeted at African stakeholders.

The way forwardThese issues highlight the need to

create a global and regional mechanism to support a more equitable distribution of the investment in education and training and the benefit from employment created by international labor mobility. The health sector has already established a partnership through the Global Health Workforce Alliance, which can be a possible model for teacher migration. In order to contribute to the fair and improved recognition of qualifications at global and regional levels, international organizations specializing in education, labor, trade, migration and development, as well as regional and national networks should cooperate to create a synergy among the activities that respective organizations are carrying out.

Responding to these needs, IICBA organized brainstorming meetings in summer 2010 on migration and development, with major international organizations, working on migration and education issues in Africa, including the African Union (AU), ILO, UNFPA, UNDP, WHO, and Addis Ababa University. Based on inputs from respective organizations and experts, as well as recommendations from a project document of the UNESCO Expert Group Meeting on “Migration and education: Quality assurance and mutual recognition of qualifications” prepared in 2008, the meetings identified existing

initiatives and partners, as well as domains of collaboration, shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Migration and education in Africa: Domains of collaboration

IOM and UNESCO-IICBA are currently elaborating a joint project document in close consultation with the AU and other stakeholders engaged in migration and education, particularly teacher migration.

Teacher gap in annual percentage of increase

Moderate (0.25-2.9%) Severe (3.0-20.0%)

Algeria, Burundi, Ethiopia, Ghana, Mauritania, Namibia, Sao Tome and Principe, Togo

Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Côte d’Ivoire, Congo, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Djibouti, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Gambia, Guinea, Mali, Mozambique, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, Sudan, Uganda, United Republic of Tanzania, Zambia

Activity Objectives

(1) information management system

collect, manage, and analyze data, disaggregated by sex, on education, workforce and migration

(2) networking and collaboration

enhance synergy and promote information sharing on migration-education nexus and their impact on development

(3) capacity building

(i) provide support to initiatives on recognition of qualifications, including TVET and higher education, and student and professional mobility; and

(ii) enhance access to training opportunities for stakeholders on quality assurance and mutual recognition of qualifications

(4) policy advocacy

(i) engage governments and decision makers on challenges and poten-tials of migration and education; and

(ii) facilitate the opera-tionalisation of selected migration and develop-ment provisions of con-tinental frameworks at national level.

6 Countries facing a teacher gap are identified as those where the number of teachers currently employed will not be sufficient to provide quality education for all primary school-age children by the target year of 2015. In 2008, among the countries surveyed, 99 countries (48%) needed to further increase the size of their primary teaching staff due to growing numbers of students, whereas 108 countries (52%) can potentially reduce their teaching forces – assuming gains in efficiency. Figure identifies the countries facing a teacher shortage, according to the magnitude of the gap.

7 Moderate teacher gaps indicates that the country requires an annual growth rate of 0.25-2.9% and severe teacher gaps indicates the teacher supply needs to grow by 3.0-20.0% for the 2008-2015 period.8 Nonnenmacher, S. (2008). Recognition of Qualifications of Migrant Workers Overview, presented at Expert Group Meeting Migration and Education, Paris, 22-23 September 2008.9 Hawthorne, L. (2008). Final Summary of Expert Group Meeting Migration and Education, Paris, 22-23 September 2008

Page 4 UNESCO IICBA Newsletter Vol. 12 No. 2 December, 2010

Introduction

International migration, including skilled labour migration has become a global phenomenon and it is increasingly rising to the top of the policy agenda in many parts of the world. UN data shows that by 2010, there were approximately 214 million people or 3.1 % of the world’s population living outside their country of birth. Women constitute nearly 50% of all international migrants1.

Migrant workers, and migrant teachers in particular, continue to be treated as a cheap and replaceable labour pool and to have their rights violated in far too many instances. Exploitation occurs at the hands of both employers and recruitment agencies, and includes such problems as loss of professional status and rights, inferior conditions of service, charging of exorbitant fees, job insecurity, rigid contracts and impediments to gaining legal resident status.

The rampant violation of migrant teachers’ trade union and labour rights has prompted Education International (EI) and its member organisations (teacher unions) to scale up measures to protect migrant teachers and their families, stop their exploitation and promote decent work for all education personnel.

Union measures to protect the rights of migrant teachers

The Commonwealth Teachers’ Group (CTG), a grouping of EI member organisations in Commonwealth countries, has laid a good foundation for work on teacher migration, and contributed to the development and implementation of the Commonwealth Teacher Recruitment Protocol (CTRP). The CTRP is an important instrument that seeks to protect the integrity of vulnerable education systems, while respecting the right of individual teachers to migrate and to have their labour and professional rights upheld. The CTRP has been recognised and endorsed as an instrument of good practice by EI, UNESCO and the ILO, among others.

Education International has also been working with other Global Unions to address the challenges associated with international labour migration. The Council of Global Unions’ Work Relationships Group has developed a set of principles outlining the rights of temporary agency workers, including international migrant workers. The Council of Global Unions has also recently established a Working Group on

Migration (WGM). As part of its mandate, the WGM coordinates the Global Unions’ policy positions on international labour migration, organises joint activities and campaigns and participates in the Global Forum on Migration and Development and related activities. Global Unions are currently supporting a petition campaign for European and other countries to ratify the UN Convention on the Protection of the Rights of all Migrant Workers and Members of their Families, which came into force in July 2003. This campaign is part of the Global Unions’ joint action and key message for this year’s International Migrants Day (18 December).

Additionally, Education International has decided to develop a Teacher Migration and Mobility Campaign and to create a Task Force to spearhead the initiative. The Task Force, comprising appointed members from EI member organisations in sending and receiving countries, will enable EI to shape and develop more policies and strategies to prevent the exploitation of migrant teachers and to create a global network of migrant teachers using the EI website. EI hopes to use this campaign and other initiatives to protect migrant teachers and their families, stop their exploitation and promote decent work for all education personnel.

Teacher Unions Scale up Measures to Defend the Rights of Migrant Teachers

By Dennis Sinyolo, Education International(EI) Senior Coordinator for Education and Employment

1 Source: World Migration Report 2010: The Future of Migration: Building Capacities for Change, published by the International Organisation for Migration

The IICBA Newsletter is published bi-annually in English and French. Articles may be reproduced with attribution. We welcome editorial comments, or inquiries about IICBA.

Please address all correspondance to

The Editor, IICBA NewsletterP.O. Box 2305,Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Tel. 251-115-445284/445435/251-111-55 75 87Fax. 251-115-514936

E-mail: [email protected]: www.unesco-iicba.org

UNESCO IICBA Newsletter Vol. 12 No. 2 December, 2010 Page 5

What does it mean to recognise the competence of a teacher that migrates from the United Kingdom to Canada, from Barbados to New Zealand, or from South Africa to the United Arab Emirates? As increasing numbers of teachers migrate between countries across the globe, often in search of greener pastures, but more recently with the global economic downturn returning to their countries of origin, a deeper understanding of their qualifications and the requirements which give these teachers the right to practice in the receiving countries has become essential. Critical questions we need to ask in this regard are whether the qualification of the migrant teacher tells us “enough” about the competence of the teacher? Will the teacher be able to function at a level comparable to local teachers? Does he have sufficient pedagogical and discipline-specific training? Will she adhere to a professional code of conduct? This brief article gives an account of some recent attempts that have been made to better understand qualifications and the extent to which this improved understanding is helpful to gauge the competence of migrant teachers.

Initial debates in this area focused on the need for increased recognition of teacher qualifications, i.e. the formal or legal specifications that qualifications must meet to be accepted within the countries where they are offered. Credential evaluation agencies (such as the National Recognition Information Centre for the United Kingdom [UK NARIC], the South African Qualifications Authority [SAQA] in South Africa, and the Centre for International Recognition and Certification [NUFFIC] in Holland) have played an important role in evaluating and recognising foreign teacher qualifications, but their processes have been criticized for being opaque and outdated, and susceptible to political influences. More recently qualifications frameworks have gained prominence on national, regional and even transnational levels. Similarly to credential evaluation, qualifications frameworks have also been

criticized, in his case for failing to deliver on their promises of increased recognition and mobility. Another important initiative that has contributed, albeit more indirectly, to the recognition of teacher qualifications across countries has been the development of the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) levels by UNESCO and the OECD in the late 1990s, and which is currently being reviewed by UNESCO.

An important attempt to improve the recognition of teacher qualifications in particular, took place between 2006 and 2010 and was based on aspects of credential evaluation and qualifications frameworks, while also drawing heavily on ISCED. The research included 35 Commonwealth countries and resulted in the publication of a “comparability table” of the initial teacher qualifications in the countries involved (published as Fair trade for teachers: transferability of teacher qualifications in the Commonwealth, available from the Commonwealth Secretariat). The study provided an opportunity to provide a response, albeit modest, to the question of what it means to recognise qualifications across borders. The study illustrated that a high level of explicitness of what a qualification means across institutions and borders is a near impossible task that soon becomes overburdened with information that is often not directly retrievable. At best the relationship between two qualifications can be understood as an approximation of a meaningful comparison using the limited technologies available today.

More recently and strongly influenced by the development of the European (meta) Qualifications Framework, the notion of “transparency” has gained prominence. Understood as the degree to which the value of qualifications can be identified and compared in education, training, the workplace and more, transparency is also the degree of explicitness about the meaning of a qualification. It implies the exchange of information about qualifications in an accessible way within and outside the country of award. When

transparency is achieved, it is potentially possible to compare the value and content of qualifications at national and international level. In recent work by Jens Bjornavold and Mike Coles for the European Centre for Vocational Development (CEDFEOP) that focused on the development of policies and practices linked to qualification and qualifications systems, three findings were made that are very useful as we try to think about transparency: (1) the “power” of qualifications to act as a metric for the performance of the education and training system has increased; (2) the extent to which qualifications function as the main way for people to progress in work has decreased; and (3) the role of qualifications to support international mobility has increased. Importantly, Bjornavold and Coles introduce the concept of “representation” as they explain the limitations of qualifications to provide information on current knowledge, skills and competences, aptitude in key competences, as well as potential/future competence. Representation, they argue, includes qualifications, but is not limited to qualifications.

Several attempts to understand qualifications, including teacher qualifications, have been outlined in this article. Ranging from credential evaluation methods, to comparability tables, and most recently, considering transparency and representation, the attempts highlight the ongoing importance of qualifications to support mobility of professionals, but also demonstrate that qualifications remain limited in the extent to which they can act as a proxy for the competence of migrant teachers. These findings have significant implications for our ongoing attempts to better understand the skills sets of migrant teachers, and will require us to move beyond agreed levels of minimum criteria, beyond more contextualized criteria, to a situation where not only past learning is evaluated, but also current and potential competence is considered. There is much to be done.

Qualification as a Proxy for the Competence of the Migrant Teacher

By James Keevy, South African Qualifications Authority

Page 6 UNESCO IICBA Newsletter Vol. 12 No. 2 December, 2010

In 2004, all member states of the Commonwealth adopted the Commonwealth Teacher Recruitment Protocol, which seeks to balance “the rights of teachers to migrate internationally on a temporary or permanent basis, against the need to protect the integrity of national education systems and to prevent the exploitation of scarce human resources of poor countries.” Since its adoption, it has been endorsed and actively supported by UNESCO, ILO, and the African Union, among others.

Research commissionedby the Commonwealth Secretariat, which set out to review the implementation of the Protocol, confirmed that the vast majority of recruited teachers were unaware of the Protocol, and thus, unaware of their rights as recruited teachers. Below are 10 recommended questions for teachers who are considering employment abroad, with a view towards securing the individual teachers’ rights and maximizing the benefits of teacher migration – for the teachers, schools, and students impacted.

(1) Who is telling you about the opportunity to teach overseas?

Our research found that many teachers found opportunities on the Internet, which included ads from schools, legitimate agencies and Ministries. Beware also of fraudulent ads and companies.

(2) Do you know the expectations of your employer in the recruiting country before departure?

Unfortunately, we identified several cases in which very experienced teachers were under utilized or had their positions downgraded upon arrival. Others were recruited to teach one subject and ended up teaching another.

(3) Are qualifications assessed before departure and/or upon arrival?

The international comparability of qualifications remains a challenge to the effective deployment of teachers. Today, a teacher cannot assume that a teaching qualification from one country will automatically carry the same status in another.

(4) Do you have a written employment contract prior to departure?

And who is your stated employer in the written contract? The school? Local education authority? Ministry? Recruiter?

(5) Are your terms and conditions of employment consistent with teachers who are nationals of similar status?

(6) Will you work under the labour laws and rules of the recruiting countries?

(7) Do you have a complaints mechanism in the recruiting country?

If, or when, problems arise, to whom do you turn? Do you have the contact information of your local teachers union? Education International, which is a global federation of teachers unions, might be a good starting point if this information is not provided to you.

(8) Do you anticipate returning home?

If you anticipate returning home, will your employer keep your job open for you? Will your experience achieved abroad be recognized and ultimately rewarded, in the form of pay and/or promotion? If you plan to return home, can you continue to make preparations for doing so whilst you are working overseas? Can you, for example, continue to make contributions to your pension?

(9) Have you looked at the total cost of teaching abroad?

Whilst many teachers go abroad in search of better pay, there are also costs and unexpected consequences. It is important to research, in advance of departure, costs of living, exchange rate / currency fluctuations, safety, and the general context of teaching. How will spouses, children and family members be impacted? This includes both those that might accompany the teacher, as well as those who might be “left behind” at home.

(10) In addition to posts at schools overseas, are there other opportunities to consider for short-term professional development (e.g. teacher-to-teacher exchanges, critical subject exchange)?

Teachers seek employment abroad for many reasons –wanting a challenge, seeking opportunities to travel, wanting to try something new, gaining professional development, or being closer to children/family. There are, however, sometimes exchange opportunities that might be pursued without having to leave the education system.

In addition, teachers are encouraged to seek out information about the following before their departure, and ideally before signing any contract to take up employment elsewhere, so that the teacher may fully evaluate the opportunity and its potential impact, both professionally and personally.

• The age range and subjects you will be teaching

• The name, location, and description of the school

• Accommodation, transportation arrangements and costs

• Work permits / visa requirements• Qualification recognition and

requirements for your new job• Salary, tax, and pension conditions,

both for the teaching position and implications for life at home

Implementation of the Commonwealth Teacher Recruitment Protocol

An independent review of the implementation the Commonwealth Teacher Recruitment Protocol, conducted in 2008/2009, examined five dimensions of implementation: recruiting countries / Ministries of Education (in both recruiting and source countries); recruited teachers; international organisations and civil society; recruiters agencies; and the Commonwealth Secretariat.The complete report is available from the Commonwealth Secretariat. Below are key findings that are particularly relevant to teachers, as they relate to specific sections of the Protocol.

Teachers learned about the opportunity to teach overseas primarily through newspaper articles, friends and information on the Internet. Less than 2 per cent of the respondents reported that they learned about international teaching opportunities directly through a school or recruitment fair. Less than 5 per cent reported that they learned about the opportunity through an education ministry. 28.3 per cent of teachers in this study were recruited to work overseas by a foreign education ministry, 23.3 per cent were recruited by a recruitment agency, and 21.7 per cent teachers reported “other” means of recruitment. Additional ways of

Teachers, Ask 10 Questions Before Teaching AbroadBy Dr. Kimberly Ochs, Education Consultant, Email: [email protected]

UNESCO IICBA Newsletter Vol. 12 No. 2 December, 2010 Page 7

recruitment included a friend (13.3 per cent) or family member (8.3 per cent) as sponsor, or recruitment directly by an overseas school (5 per cent).

Teachers were asked if they were aware of the Commonwealth Teacher Recruitment Protocol. Of the 57 teachers who responded to the question, 82.5 per cent were unaware and 4 per cent were uncertain / did not know. Only 10.5 per cent of the teachers in the Study were aware of the Protocol. Out of the 6 individuals who were aware of the Protocol and only three teachers had read the Protocol.

Other key findings were that:

• 59.3 per cent of teachers reported their terms and conditions of employment were consistent with those of teachers who are nationals of similar status, and 16.9 per cent were uncertain / did not know (n=59) (Protocol Section 3.10). Additionally, only 35.6 per cent of respondents reported that they were able to find information regarding employment status / expectations of the employer in the recruiting country before departure. This information was usually sourced over the Internet or during the interview process.

• 75.9 per cent of teachers reported that they work under the labour laws and rules of the recruiting country, and 15.5 per cent were uncertain / did not know (n=58). (Protocol Section 3.11). The five teachers reporting that they did not work under the labour laws of the recruiting country were employed in the UK (4) and US (1), and were citizens of South Africa (2), Jamaica (1), Barbados (1), and Iran (1).

• Of the 40 teachers who responded to the question about orientation programmes, only 29 had been provided some form of orientation. Responses amongst teachers ranged from “poor” to “workshops” to “very intensive” (Protocol Section 3.14).

• 87.3 per cent of teachers reportedly gave adequate notice of resignation to leave the school in the home country before taking up a position overseas, and 5.5 per cent were uncertain (n=55) (Protocol Section 5.2).

• As evidenced by the teachers in this study and by discussions with recruitment agencies, the most experienced teachers are the most

attractive teachers. 59 per cent of the teachers who took part in this study had more than 14 years of experience.

• The issue of qualifications and comparability of qualifications remains a challenge to the effective deployment of teachers. Teachers in this study were asked if their qualifications were assessed before departure and upon arrival. Of the total number of respondents (n=53), 54.7 per cent reported that their qualifications had been assessed before departure, whereas 42 per cent of the teachers who answered the second question (n=50) underwent a review of their qualifications upon arrival.

• Only 69 per cent of respondents (n=55) reported that they were asked if they have a criminal record during the interview process, with an additional 16.4 per cent reporting that they were uncertain / did not know. It is notable, however, that in some countries it is illegal to ask about one’s criminal background during an interview, although a question might be included on an application form.

An exploratory, and new dimensions of the research to the review the Protocol was to examine the role of recruiters and private recruitment agencies, which is addressed in the following sections of the Protocol:

As outlined in the Protocol:

• “The government of any country which makes use of the services of a recruiting agency, directly or otherwise, shall develop and maintain a quality assurance system to ensure adherence to this Protocol and fair labour practices. The recruiting countries should ensure compliance. Where agencies do not adhere, they will be removed from the list of approved agencies” (Protocol Section 3.7).

• “The recruiting agency has an obligation to contact the intended source country in advance, and notify it of the agency’s intentions. Recruiting countries will inform recruiting agencies of this obligation. Recruiting countries should inform source countries of any organised recruitment of teachers” (Protocol Section 3.8).

• “Prior agreement should be reached between the recruitment agency and

the government of the source country, regarding means of recruitment, numbers and adherence to labour laws of the source country. Recruitment should be free from unfair discrimination and from any dishonest or misleading information, especially in regard to gender exploitation” (Protocol Section 3.9).

• “…The recruiting agency shall inform recruited teachers of the names and contact details of all teachers unions in recruiting countries” (Protocol Section 3.12).

Indirectly, the Rights and Responsibilities of the Recruited Teacher also involve recruitment agencies, as the teachers learn about the opportunity and/or have their passage facilitated by the agencies:

• “The recruited teacher has the right to transparency and full information regarding the contract of appointment. The minimum required information regarding the contract of appointment. The minimum required information includes information regarding complaints procedures.” (Protocol Section 5.1).

• “Recruited teachers are in turn expected to show transparency in all dealings with their current and prospective employers, and to give adequate notice of resignation or requests for leave. Teachers also have a responsibility to inform themselves regarding all terms and conditions of current and future contracts of employment, and to comply with these.”(Protocol Section 5.2).

Ways ForwardIt is essential for teachers to be proactive

in their investigation of employment opportunities abroad. The Commonwealth Teacher Recruitment Protocol serves as a document outlining the rights and responsibilities for teachers.

Reference:Commonwealth Teacher Recruitment Protocolhttp://www.thecommonwealth.org/Internal/190663/190673/191274/39504/commonwealthteacherrecruitmentprotocol/Commonwealth Secretariathttp://www.thecommonwealth.orgEducation Internationalhttp://www.ei-ie.org/

Page 8 UNESCO IICBA Newsletter Vol. 12 No. 2 December, 2010

South Africa’s inclusion into the global labour market in 1994, when she emerged from apartheid to embrace democracy, created numerous transnational work opportunities for her citizens. Teachers were one such category2 who, due to a shortage in developed countries, were aggressively recruited to the United Kingdom to fill the needs in British classrooms. This recruitment drive was exacerbated by UK principals declaring that SA teachers were held in high regards and that London schools would have to close were it not for foreign teachers from South Africa, Australia and New Zealand. As South Africa did not and still does not have a data base capturing the inflow and outflow of her citizens who have become migrants, the extent of the brain drain, gain and circulation was and still is difficult to determine.

The quality of teachers being recruited is of concern especially those who specialise in critical areas such as math and science, being equally in demand especially in rural areas in South Africa. Although there has been a lack of quantitative evidence, there have been some qualitative studies (Manik, 2005, Manik, 2009-2010) which unpack the nature of teacher migration between South Africa and the United Kingdom. Both newly qualified and experienced teachers were recruited prior to 2008. The demographic profiles were: Newly qualified teachers were white, 28 years and younger and unmarried, while experienced teachers were Indian, between the ages of 29-42, married and from ex-House of Delegates3 public schools. African teachers were not recruited due to gate-keeping strategies by recruitment agencies, as candidates needed to have a professional teaching qualification and many African teachers are unqualified. Also, fluency in English is a pre-requisite.

There were multiple reasons, not mutually exclusive of each other, that coalesced to create an impetus to exit South Africa. These included financial - especially the pound to rand exchange rate,

travel opportunities within the UK and to Europe, the impact of numerous education policy changes being suddenly effected in South Africa, and problematic school environments. Recruitment was largely undertaken by unscrupulous agencies, who recognised that teachers had become lucrative commodities. These agencies failed to declare to South African teachers that their qualification is not recognised in the UK, and they would be forced to study towards Qualified Teacher Status if they intend remaining in the UK.

Majority of the teachers experienced a culture shock in UK classrooms, especially since foreign teachers are recruited to challenging schools in low socio-economic areas where discipline is poor. Those who were resilient adapted by using innovative classroom pedagogies such as wit and humour to win over learners. Few who were unable to adapt or angry about the lack of professional recognition, which translated to a lesser salary, returned to South Africa within a year of their migration. However, upon return some were contemplating re-migrating to teach in other destinations, such as New Zealand.

A tracer study undertaken between 2009-2010 of nine Indian teachers who remained in the UK, revealed that these teachers are no longer South African citizens, having being granted British citizenship. They have flourished professionally and occupy senior management positions at school. Whilst they retained close ties to friends and family in South Africa, they were content with life in the UK and reluctant to return to South Africa citing crime and affirmative action as contributory factors.

It appears that political pressure from the then Education Minister Kader Asmal, accusing the UK of ‘poaching’ teachers, and the South African government’s subsequent non-

participation in a youth mobility scheme (which replaced the working holiday visa in 2008) with the UK, has curtailed the ‘haemorrhaging’ of teachers to the UK. At present only those teachers with British ancestry are being recruited to the UK. A snap survey undertaken amongst 96 post graduate Certificate in Education students at one higher education institution in South Africa in 2010 revealed that soon –to –be qualified teachers were keen to teach both locally and abroad. The UK still appears to be a favoured destination (23%) with the Middle and Far East and New Zealand-Australia becoming other favoured options. ‘Crime in South Africa’ was provided as a reason for wanting to teach abroad, but this was articulated by only white and Indian females. Another interesting finding was that a higher percentage of Indians (40%) than whites (34%) wished to teach abroad and 21% of Africans as well. Newly qualified teachers appear to be receptive to acquiring international teaching experience and many admitted to wanting to teach abroad regardless of the country.

It is therefore apparent that the desire to teach abroad is gaining impetus amongst South Africans who are keen to become global teachers.

2 SA is losing workers in the following fields: health (nurses, doctors etc.), teaching, engineering, accoun�ng and informa�on technology3 Schools designated for the Indian popula�on during apartheid in South Africa. At present the teacher popula�on in schools has not been desegregated although the pupil

popula�on has in many urban schools.

South Africa Joins the Global TeacherhoodBy Dr. Manik Sadhana, Kwazulu National University, South Africa. Email: [email protected]

UNESCO IICBA Newsletter Vol. 12 No. 2 December, 2010 Page 9

IICBA Governing Board Meeting Held

The 12th Session of IICBA Governing Board Meeting took place on 3-4 December 2010 at the HQ of the Institute in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. The Meeting heard reports of activities implemented in 2010 and also reviewed planned activities for 2011. Moreover, the Board discussed at length the draft Strategic Plan for the 2011-2015 and suggested various improvements both in the design and content of the document. The Board was also briefed on the Ethiopian Government’s decision to build a six-storey office building for IICBA. His Excellency, Mr. Demeke Mekonnen, Minster of Education of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia reiterated the commitment of Ethiopia, as the host country, to assist IICBA in the important work it is doing in Africa. The Board has acknowledged this and extended its gratitude to the kind gesture of the Ethiopian Government.

New Director Appointed for IICBA

Mr. Arnaldo Nhavoto (Mozambique) has been appointed by the Director General of UNESCO as IICBA Director effective 15 November 2010. Mr. Nhavoto has had long years of service in education in Africa, starting his career as a teacher in his native country, Mozambique. He then assumed progressively important posts until he became Minster of Education from 1994-2000. During his tenure as minister, he led the reconstruction effort to rehabilitate his country’s education system. Between 2000 and 2005, Mr. Nhavoto was a member of the Mozambican National Parliament.

In addition to his work in Mozambique, Mr. Nhavoto has also served as education consultant for various international organisations, including UNESCO, before becoming the director of IICBA. His recent assignment was Technical Assistance Team Leader for the Project in Support of Primary Education (PAEP) in Angola, based in Luanda.

Training on TTISSA Methodological Toolkit ConductedA training workshop on the application of the TTISSA Methodological Toolkit was conducted in Bamako, Mali on 13-17 December 2010. A team of experts from IICBA, TTISSA Unit within BREDA and the UNESCO Office in Bamako facilitated the workshop that brought together relevant personnel of the Ministry of Education and Teacher Education Institutions in Mali. The workshop highlighted the processes involved in conducting a diagnosis of the teacher issues in the country, and culminated by setting up six teams that will look into the six themes of the Toolkit and carry out data collection on the various aspects of teacher related issues with the intention of having a comprehensive analyses of the issues that will guide future interventions in line with the concerns of TTISSA.

Curriculum Analysis Workshop for ECOWAS Countries

IICBA organised a Curriculum Analysis Workshop for Teacher Training for the ECOWAS Region on 3-5 November 2010 in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. Participants from nine countries (Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Mali, Niger, Senegal and Togo, and colleagues from ADEA and ROCARE attended the workshop. The workshop was meant to analyse the teacher training curriculum of the countries in the sub-region with the expectation of streamlining their programmes to cater for teacher mobility within the sub-region. It is also meant to review the programmes in light of issues on ICT Use in Education, Basic Education in Africa (BEAP), Gender Issues, Inclusive Education and Education for Sustainable Development. A follow up workshop is planned to take place in the first quarter of 2011.

Workshop on ICT Enhanced Teacher Standards Conducted in BrazzavilleIICBA organized its third sub-regional workshop on ICT-Enhanced Teacher Standards for the Economic Community of Central African (CEMAC), East African Community (EAC) and Inter-Governmental Agency for Development (IGAD) countries. The workshop was held in Brazzaville, Republic of Congo, from 12-14 October 2010. Participants came from Cameroun, Congo (Brazzaville), Ethiopia, Gabon, Equatorial Guinea, Uganda, Central African Republic and Chad. The Brazzaville workshop was the third and final workshop in the bid to eventually come up

NEWS IN BRIEF

Page 10 UNESCO IICBA Newsletter Vol. 12 No. 2 December, 2010

with a regional standard for Africa. Two earlier workshops were held for the ECOWAS and SADC regions earlier to the Brazzaville one. An Africa wide validation workshop is planned for 2011.

Teacher Education Institutions Management Training Conducted

IICBA conducted two teacher education management workshops for high level management staff of teacher education institutions and acuities of education in Ethiopia. The first workshop took place in Mekelle town on 20-24 September 2010 and brought together 37 participants. The second one, held in Hawassa town on 4-8 October 2010, was attended by 43 participants composed of deans, deputy deans, finance officers and registrars of teacher education institutions and faculties of education drawn from various parts of the country. The workshops were organised as part of the CapEFA Ethiopia project and were part of a series of four workshops planned to be conducted in various parts of the country.

IICBA at the World Conference on ECCEIICBA attended and made a presentation in the World Conference on Early Childhood Care and Education (WCECCE) held in Moscow on 27-29 September 2010. Having conducted the ECCE studies in 6 sub-Saharan African countries, namely Burkina Faso, Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Lesotho, Nigeria and South Africa, the conference provided an opportunity for IICBA to share with the rest of the world, the challenges, government policies and programmes of intervention, some good practices in ECCE teacher development, and policy options for teacher development in the sub-region.

IICBA Attended INRULED Governing Board Meeting

IICBA was invited to attend the Governing Board Meeting of the UNESCO International Research and Training Centre for Rural Education (INRULED) in Beijing, P. R. China, on 5-6 August 2010. The opportunity allowed IICBA to brief INRULED Board Members on the state of the collaboration that the Institute has forged with INRULED. The major joint activities carried out so far - the study tour to China in November 2009; the study visit by Chinese teacher educators to Africa in February 2010 - and the planned activities for 2010 were highlighted in the briefing. The Governing Board has commended the work being done by IICBA and INRULED.

Validation Workshop Conducted in Accra, GhanaA validation workshop for the assessment of teacher education policies from gender perspectives that was carried out in three West African countries: Ghana, Nigeria and Senegal took place in Accra, Ghana on 27-28 July 2010. The objectives of the

workshop were: i) to validate the assessment findings and enrich them using inputs forwarded by workshop participants; ii) to encourage participants from other countries to share information and experiences regarding the gender responsiveness of teacher education policies in their respective countries; and iii) to get inputs for a training module that will be developed and used to train relevant individuals in developing gender responsive teacher education policy. Sixteen participants from Ghana, Burkina Faso, Senegal, Nigeria, Liberia and Cote D’Ivoire attended the workshop.

IICBA Launches Its First Booklet Series IICBA has launched its first booklet series on Fundamentals of Teacher Education Development. The First issue is titled “Bringing back the teacher to the African Schools” by Prof. PAI Obanya. The publication was done in December 2010. The second and third editions will be coming out soon.

The series is meant to achieve the following objectives: i) monitor the evolution and change in policies and their effect upon teacher development and management requirements; ii) highlight current teacher issues to improve on existing policies in documented form, and iii) disseminate development and management techniques that can be applied to positively impact on teacher issues in Africa and beyond. Copies of the book can be received from IICBA on request.

Regional Workshop on Skills Development Conducted

IICBA, in collaboration with University of Pretoria science ex-perts, organized a regional training workshop for public high school teachers, curriculum developers and Ministry of Educa-tion gender focal persons on skills development for enhanced Girls’ Participation in Science, Maths and Technology Education (SMTE) in Swaziland from 18 – 21 October 2010. The aim of the workshop was to engage the participants in skills development using a research and development (R&D) approach with specific focus on gender issues in science, maths, and technology educa-tion (SMTE). 25 teachers who are heads of department and sub-ject heads (men and women) from public high schools, university teachers, curriculum developers, provincial & regional science and mathematics inspectors attended the training workshop

FarewellMr. Julien Daboué, who was the Programme Coordinator and Officer-in-Charge of IICBA from September 2008 to October 2010, has been transferred to the UNESCO Regional Bureau of Education for Africa in Dakar to take up his new assignment as Senior Programme Specialist for Basic Education. IICBA wishes all the best for Mr. Daboué in his future endeavours, and reiterates its desire to work with him and his colleagues in BREDA more closely in the area of mutual interest between IICBA and the Regional Office.