Name of Electoral Area Census Block Code Name of Electoral Area ...

Political knowledge and electoral choice

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of Political knowledge and electoral choice

CREST CENTRE FOR RESEARCH INTO ELECTIONS AND SOCIAL TRENDS Working Paper Number 87 September 2001

Political Knowledge and Electoral Choices

By Robert Andersen, Anthony Heath and Richard Sinnott The Centre for Research into Elections and Social Trends is an ESRC Research Centre based jointly at the National Centre for Social Research (formerly SCPR) and the Department of Sociology, University of Oxford http://www.crest.ox.ac.uk

Political Knowledge and Electoral Choices by

Robert Andersen,Anthony Heath and Richard Sinnott

A b s t r a c t

This paper assesses the impact of political knowledge on electoral choices during the 2001

British Election. We explore the impact of knowledge of party platforms on taxation,

privatisation and Europe on the relationships between respondents’ positions on these

issues and voting behaviour. Our results show that knowledge does, in fact, affect how

people vote. This was especially evident for all issues in the contrast in vote for the

Conservatives and Liberal Democrats. On the other hand, knowledge about the party

platforms on taxation and privatisation had little effect on the contrast on the vote choice

between Labour and Liberal Democrats. However, knowledge of party platforms about

Europe, an issue about which voters would have difficulty finding effective short cuts, did

have a significant impact on all vote choices. Perhaps the most important implication of

these findings is that the Liberal Democrats do seem to benefit when voters are

knowledgeable, suggesting that their performance at the polls could be improved with

greater exposure.

Political Knowledge and Electoral Choices by

Robert Andersen,Anthony Heath and Richard Sinnott

1

Introduction There is growing interest in the concept of political knowledge. Much research in the area

is normative, focusing on what can be labeled ‘civics’ knowledge—i.e., knowledge about

government and political institutions—and how it might be expected to affect the

functioning of democracy (see Schumpeter, 1967). There is substantial evidence that this

type of political knowledge is generally low, especially in the United States (see Fishkin,

1999). Moreover, research is quite convincing that the electorate is stratified according to

political knowledge, with the knowledgeable tending to differ from the less knowledgeable

in the structure, consistency and stability of their political attitudes and ideologies (for

example, Delli Carpini and Keeter, 1996; Bartle, 1997; Sinnott, 2000). Research also

shows that voters are generally uninformed about political issues (see Page and Shapiro,

1992). It is less obvious, however, whether or not knowledge of party platforms affects the

electoral choices of voters.

Some writers suggest that voters with low levels of political knowledge are able to get by

as if they are well informed. Popkin (1994), for example, suggests that voters may use

‘heuristics’ or information short-cuts, such as following the position taken by a group or

leader that the citizen believes has their interests at heart (see also Sniderman et al, 1992;

Neuman et al, 1992; Zaller, 1992; Graber, 2001). Meanwhile, others argue that while it

may be the case that individual voters make uninformed choices, the public as a whole still

makes the choice it would make if everyone were fully informed. While some voters may

make the ‘wrong’ choice in one direction, other voters will do so in the opposite direction.

This results in the errors being cancelled out, meaning that the collective decision of

society as a whole is the ‘right’ one (Shapiro and Page, 1988).

Such attempts to rescue the voter from an apparent ignorance have been fervently disputed.

For example, both Zaller (1992) and Delli and Keeter (1996) argue that voters cannot

deploy the kinds of short-cuts suggested by Popkin (1994) unless they have sufficient

knowledge about the provenance of the messages that they hear. Moreover, Bartels (1996)

Political Knowledge and Electoral Choices by

Robert Andersen,Anthony Heath and Richard Sinnott

2

argues that voters with low levels of political knowledge do make different choices from

those with higher levels of knowledge with important implications for the overall outcome

of elections (see also Lupia, 1994; Lupia and McCubbins, 1998). Bartels findings can be

little more than suggestive, however, because they rely on American National Election

Study data, which contain only interviewers’ assessments of respondents’ levels of

political knowledge rather a direct measure. Nonetheless, research using ‘deliberative

polls’ has shown that giving people information can indeed change their views (Fiskin,

1997; 1999).

These arguments all assume that knowledgeable voters follow, at least in part, an issue-

based procedure for deciding how to vote (see Brody and Page, 1972; Kessel, 1972). This

too is, of course, strongly contested. While public discourse centres on the issues

advocated by the parties (and this is what to a considerable extent gives the parties

normative legitimacy to implement their manifestos when in office), voting decisions are

also based on other considerations. For example, criteria such as the personality of the

party leaders (Stewart and Clarke, 1992) and the economic record of the incumbent

government have also been shown to be important (Key, 1968; Fiorina, 1981; Lewis-Beck,

1988). Moreover, it is by no means clear that political knowledge is all that relevant to

these other criteria. Most obviously, political knowledge is not a prerequisite for

understanding how much disposable income one has. In fact, Fiorina’s (1981)

retrospective theory of economic voting holds that economic voting does not require a

sophisticated understanding of the policy issues.

Aside from a few exceptions, research on political knowledge has focused mostly on the

United States. Nonetheless, with its multi-party system and multidimensional cleavage

structure, Britain provides a potentially valuable arena in which to test the impact of

political knowledge. A multi-party system makes the task of selecting the party whose

policies best accords with one’s own issue preferences less straightforward than in an

essentially two party system as in the United States. In other words, if political knowledge

is important it should be clearly detectable in Britain. Changes to party manifestos

Political Knowledge and Electoral Choices by

Robert Andersen,Anthony Heath and Richard Sinnott

3

regarding the major issues make the 2001 British election an even more interesting testing

ground for the effects of political knowledge on issue voting.

The goal of this paper, then, is to contribute to the debate over the effects of political

knowledge on electoral choices. Our concern is with whether knowledge of party

platforms leads to a closer accord between voters’ preferences and party positions. We

assess these relationships during the 2001 British Election. Although our primary concern

is with testing the impact of knowledge on issue-based voting, we control for other factors

held to be related to voting.

Issues and Party Platforms in 2001 We begin with a discussion of the platforms on the issues of taxation, privatisation and

European integration for the three major parties—Labour, Conservatives and Liberal

Democrats. In particular, it is necessary to explain how the party platforms changed in the

years leading up to the 2001 election.

A simple stereotype of party competition in Britain before 1992 suggests that it was

organized along the left-right continuum, with the Labour party situated on the left, the

Liberal Democrats in the centre, and the Conservatives on the right. Analysis of party

manifestos suggests that this was indeed an appropriate way to characterise much political

debate in Britain during this period, particularly on issues such as nationalisation and

privatisation of industry, and taxation and spending, which are central to the left-right

continuum (see Budge, 1999). Since party positions exhibited a fair degree of continuity

over time on these issues, the use of shortcuts based on overall left-right positions could be

considered appropriate. In fact, we might expect that the less knowledgeable were as

effective as the more knowledgeable in translating their issue preferences into appropriate

party choices because the ideological positions of the parties were well entrenched for

many years.

Political Knowledge and Electoral Choices by

Robert Andersen,Anthony Heath and Richard Sinnott

4

Important though this simple picture was before 2001, it no longer holds true. In less than a

decade, the ideological space occupied by British political parties has changed drastically.

There is significant empirical evidence, both from party manifestos (see Bara and Budge,

2001) and from the empirical studies of the self-reported ideological positions of Members

of Parliament representing the three major parties (see Norris and Lovenduski, 2001), that

the ideological positions of the parties have changed drastically. In other words, the simple

story of the Liberal Democrats sitting between the Labour Party and the Conservative Party

is no longer true on most left-right issues.

Of course, the most significant change was the coming of ‘New Labour’. The widely

publicised move of the Labour party towards the centre of the political spectrum after the

1992 election began a closing of the gap between Labour and the Liberal Democrats. By

2001 the Liberal Democrats were firmly to the left of the Labour party on many important

issues (Bara and Budge, 2001). For example, the Liberal Democrats were the only party

promising to raise income taxes to spend more on public services such as health and

education. There is also sufficient evidence to suggest that the Liberal Democrats had also

moved to the left of the Labour Party on the privatisation issue during the 2001 election.

The Labour Party’s proposal to privatise the London tube and the Liberal Democrats vocal

opposition to this proposal are evidence of this point.

Changes in party manifestos and the fact that it cross-cuts with traditional left-right issues

meant that the issue of Europe was also a particularly difficult one in 2001 for those voters

wishing shortcuts. As recently as 1983, Labour was the most Eurosceptic party, but it has

since adopted a somewhat more Europhile position under Neil Kinnock and Tony Blair. In

contrast, from being a Europhile party in 1983 (when Margaret Thatcher said that it would

be folly to think of leaving Europe), the Conservatives are now much more Eurosceptic.

These factors make it difficult for voters to simply extrapolate from their knowledge of

general positions on the left-right dimension. The Liberal Democrats, on the other hand,

have maintained a fairly positive, although not very well publicised, approach to Europe

Political Knowledge and Electoral Choices by

Robert Andersen,Anthony Heath and Richard Sinnott

5

throughout, and since 1997 their manifesto has been considerably more positive about

Europe than that of either of the other two parties (Bara and Budge, 2001).

Given these changes to the ideological positions of the major British political parties

leading up to the 2001 election, one might expect that less knowledgeable voters would be

considerably more likely to mistakes in translating their own issue preferences into votes.

In other words, relying upon past impressions in order to ascertain which party is closest

to them on particular issues would be largely ineffective. If political knowledge does affect

people's ability to process new political information, we might expect those with higher

knowledge are better able to distinguish the new positions of the parties on Europe than

those with lower levels of knowledge. Certainly, previous work on the evolution of the

race issue in the United States suggests that this might be the case (Carmines and Stimson,

1980; 1989).

From these observations we can derive three general hypotheses about the relationship

between knowledge and issue voting, all of which we test in the present paper. First, we

expect that knowledge will have impact on the relationships between personal positions on

issues and vote. In other words, those with higher knowledge will be better able to match

their policy preferences to party platforms on taxation, privatisation and Europe. Secondly,

we expect that this impact will be strongest for the contrast in vote between the

Conservative Party and the Liberal Democrats since they are the two parties on the

opposite ends of the political spectrum. Finally, these two hypotheses imply a third

hypothesis, that states that mistakes do not cancel each other out. That is, we expect to find

significantly different average voting patterns between the knowledgeable and less

knowledgeable.

Data and Methods

We employ data from the 1997-2001 British Election Panel Study (BEPS). The baseline

sample for the BEPS was the 1997 British Election Study, which conducted 3,615

Political Knowledge and Electoral Choices by

Robert Andersen,Anthony Heath and Richard Sinnott

6

interviews with respondents representative of British voting age population. The initial

response rate of the British Election Study was 62 percent (see Thomson et al. 1999 for

more details). BEPS consists of eight waves, each involving re-interviews with the

original respondents. Although we use information from the initial wave, we rely primarily

on waves seven and eight, which were conducted shortly before and following the 2001

election, giving a sample size of 2,206.

To test our hypotheses we fit a multinomial logit model with vote as the dependent

variable. Our concern is with the contrasts in vote between the three major parties—

Labour, Conservative and Liberal Democrat. We concentrate only on these parties both

because they receive most of the votes, and because it is between them that the major left-

right issues are fought. Our primary explanatory variables are knowledge of party

platforms on taxation, privatisation, and the European Union and respondents’ attitudes

toward those issues. Most importantly, the model includes interaction terms between the

knowledge variables and respondents’ positions on the issues in order to test whether

knowledge strengthens the relationship between attitudes and vote. The effects of these

interactions are shown using effect displays (see Fox, 1987). Finally, the model controls

for region, gender, education, age, opinions of party leaders, and economic perceptions.1

More details of the explanatory variables are given below.

Respondents’ Positions on Issues

We use 11-point (A-K) scales for ascertaining respondents’ attitudes toward taxation and

spending, nationalisation and privatisation, and the European Union. High scores represent

right-wing attitudes, while low scores represent left-wing attitudes. The survey questions

are as follows:

1 Preliminary analysis excluding the control variables gave similar results as the analysis presented here.

Political Knowledge and Electoral Choices by

Robert Andersen,Anthony Heath and Richard Sinnott

7

(1) Taxation and Spending “Some people feel that the government should put up taxes a lot and spend much more on health and social services. These people would put themselves in Box A. Other people feel that the government should cut taxes a lot and spend much less on health and social services. These people would put themselves in Box K. An other people would put themselves in Box K. In the first row of boxes, please tick whichever box comes closest to your own views about taxes and government spending.” (2) Nationalisation and Privatisation “Some people feel that the government should nationalise many more private companies. These people would put themselves in Box A. Other people feel that the government should sell off many more nationalised industries. These people would put themselves in Box K. An other people would put themselves in Box K. In the first row of boxes, please tick whichever box comes closest to your own views about nationalisation and privatisation.” (3) European Union “Some people feel that Britain should do all it can to unite fully with the European Union. These people would put themselves in Box A. Other people feel that Britain should do all it can to protect its independence from the European Union. These people would put themselves in Box K. An other people would put themselves in Box K. In the first row of boxes, please tick whichever box comes closest to your own views about European Union.”

Political Knowledge Rather than use a single measure of political knowledge, we constructed three separate

measures of knowledge based on the party platforms on taxes, privatisation and European

integration. To do so we rely on questions similar in structure to those of respondents’ own

opinions about the issues. In this case, however, respondents were asked to place each of

the political parties on the 11-point left-right scale. Those respondents who placed all the

parties in the correct positions relative to each other—i.e., those with high knowledge—

were assigned a score of 1. All others were coded 0. Empirical information about the

relative positions of the parties was gathered from the 2001 party manifestos (see also

Budge, 2001), and the 2001 Representation Study (Norris and Lovenduski, 2001).

Following our earlier discussion, knowledgeable respondents placed the Labour Party in

Political Knowledge and Electoral Choices by

Robert Andersen,Anthony Heath and Richard Sinnott

8

the middle between the Conservatives on the right and the Liberal Democrats on the left for

all three issues.

It is worthwhile to assess the validity of our measures of political knowledge. There has

been some debate about the relationship between civics knowledge and knowledge of

issues (see Luskin, 1987). Therefore, one way to assess our measures is to compare them

to a measure of civics knowledge. BEPS included a political knowledge quiz that is well

suited for this purpose. Table 1 displays the mean scores on the political knowledge quiz

for the low and high knowledge groups for each of the three issues under investigation. For

all three issues, those with knowledge of the platforms of the three major parties score

higher average scores on the civics political knowledge quiz. Table 1 suggests, then, that

our measures adequately differentiate those with high political knowledge from those with

low political knowledge.

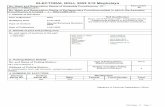

Table 1 Mean scores on political knowledge quiz according to level

of knowledge on party policies Policy issue:

Mean Standard deviation

Number of cases

Taxes

Low knowledge 4.03 1.57 1433 High knowledge 5.17 1.21 660 Privatisation

Low knowledge 4.26 1.56 1734 High knowledge 5.02 1.40 325

Europe

Low knowledge 4.23 1.56 1755 High knowledge 5.40 1.20 319

Control variables

Region is operationalised by two dummy regressors representing Scotland and Wales, with

England as the reference category. Gender is coded 1 for men and 0 for women. Education

Political Knowledge and Electoral Choices by

Robert Andersen,Anthony Heath and Richard Sinnott

9

is treated as a set of four dummy regressors: (1) university degree, (2) some post-

secondary education, (3) A-level, and (4) O/CSE level. Those with less education or

foreign qualifications are the reference category. Age is coded as two dummy regressors—

65 years and older, and 35-64 years old—with those under 35 years of age as the reference

category. Opinions of leaders were measured using questions that asked respondents how

well they thought each of the leaders of the three major parties—Tony Blair (Labour

Party), William Hague (Conservative Party) and Charles Kennedy (Liberal Democrats)—

would do as Prime Minister. Finally, the model also controls for retrospective economic

perceptions. We include two variables from questions asking respondents how well they

thought the British economy performed during the past year, and how their own household

income had changed in the past year.

Results

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics for some of the key variables in the analysis. A

number of things are noteworthy. First, it is clear that opinions toward the party leaders

differed substantially, with Labour leader Blair being most popular and Conservative

leader Hague being the least popular. The distributions of the knowledge variables are also

interesting. Nearly 30 percent of respondents were knowledgeable of the relative party

positions on taxation, while less than 15 percent accurately placed the parties on

privatisation and Europe. The relatively large proportion of knowledgeable people on

taxation perhaps reflects that it was one of the most discussed issues during the campaign

(see Bara and Budge, 2001). These points will be revisited later in the paper.

Political Knowledge and Electoral Choices by

Robert Andersen,Anthony Heath and Richard Sinnott

10

Table 2 Descriptive statistics (means or percentages) of selected variables used

in the analysis Variable:

Mean

Standard deviation

Opinions of party leaders Blair 3.53 1.12 Hague 2.62 1.23 Kennedy 3.14 1.12 Economic perceptions

Household income 2.59 1.25 British economy 2.67 1.24 Opinions of issues

Taxes 3.84 2.14 Privatisation 5.13 2.56 Europe 6.81 3.27 Knowledgeable of party policies Taxes 29.7 Privatisation 14.6 Europe 14.3 Party voted for in 2001 election Conservative Party 22.1 Labour Party 33.8 Liberal Democrats 15.8 Other/did not vote 28.3 Number of cases 2231

Our analysis now turns to the relationships between platform knowledge, respondents’

views on issues and political party choices. As we discussed earlier, the Liberal

Democrats are to the left of the Conservatives and Labour on all three issues that we

examine. We should expect, then, that if issue voting does take place those with right-wing

policy preferences would be inclined to vote for either the Conservative Party or Labour

Party rather than the Liberal Democrats. In our multinomial logit model, we also expect

that the parameters for the Labour/Liberal Democrat contrast to be much smaller than those

for the Conservative/Liberal Democrat contrast since the Liberal Democrats are much

further away ideologically from the Conservative Party than they are from the Labour

Party. More importantly, however, we expect that these relationships will be strongest for

Political Knowledge and Electoral Choices by

Robert Andersen,Anthony Heath and Richard Sinnott

11

those who are knowledgeable about party platforms. In other words, we expect to find

significant interactions between the knowledge variables for each issue and personal

attitudes toward those issues.

Table 3 displays the coefficients from the multinomial logit model fit to the data. It is

evident that opinions of leaders play an important role in party choice. Opinions of all

three leaders are significantly related to each of the two party choice contrasts. Simply put,

if voters felt the party leader could make a good Prime Minister they were highly likely to

vote for his party. It is also obvious that perceptions of the economy played a significant,

though lesser, role in electoral choices. Voters who felt that the economy had done well,

and their own household income had improved, during the past year were much more likely

to vote for the incumbent Labour Party. As one might expect since both parties were in

opposition, the effects are smaller for the contrast between the Conservative Party and

Liberal Democrats.

Political Knowledge and Electoral Choices by

Robert Andersen,Anthony Heath and Richard Sinnott

12

Table 3

Multinomial logit model of vote during the 2001 election Independent variables:

Conservative versus Liberal Democrat

Labour versus Liberal Democrat

Coeff. s.e. Coeff. s.e. Constant .11 .79 .36 .71 Nation

Scotland -.85** .27 .31 .20 Wales -.97 .54 .35 .39 England — — — — Men -.16 .21 .10 .17 Education

Degree .09 .37 -.74** .28 Some post secondary -.09 .31 -.82*** .25 A-level .64 .36 -.33 .29 O/CSE level .38 .28 -.07 .23 Age

Under 35 — — — — 35-64 .42 .29 -.11 .22 65 and over .79* .33 -.49 .26 Opinions of leaders

Blair -.28** .10 .99*** .11 Hague .93*** .09 -.21** .08 Kennedy -.94*** .10 -.61*** .09 Economic perceptions

Household income .08 .09 .23*** .07 British economy -.20* .09 .20** .07 Respondent’s position on issues

Taxes .07 .06 -.09 .05 Privatisation .008 .05 -.11** .04 Europe .13*** .04 .07* .03 Party platform knowledge

Taxes -1.09* .51 -.83* .36 Privatisation -3.37*** .88 -.86 .45 Europe -2.72** .87 -1.14** .43 Position X knowledge

Taxes .26* .11 .05 .09 Privatisation .50*** .14 .08 .09 Europe .37** .12 .17* .08 Lack of Fit 1194.87*** (46 df)

Cox and Snell R2 .57

Number of cases 1418

*p-value <.05; **p-value <.01; ***p-value <.001

Political Knowledge and Electoral Choices by

Robert Andersen,Anthony Heath and Richard Sinnott

13

We now turn to an assessment of the impact of issues on vote. What is striking here are the

strong negative effects of platform knowledge on both the Conservative/Liberal Democrat

and Labour/Liberal Democrat contrasts. These finding have important implications since it

implies that the Liberal Democrats suffer in the polls because the electorate is unaware of

their position on the issues. It is also interesting that although there are some significant

coefficients, the effects of respondents’ positions on issues has only small main effects on

vote when controlling for knowledge and the interaction between positions on issues and

knowledge about the party platforms. Nevertheless, there are some highly significant

interactions between respondents’ own viewpoints on the issues and their knowledge of the

parties’ viewpoints on these issues. We now turn to the effects displays for each of impact

of each of the issues on vote in order to highlight this latter point.

We shall first examine the relationship between attitudes toward taxation, knowledge about

the party stances on this issue, and vote. Figure 1 displays the fitted probabilities of the

vote contrasts for the Labour Party and Conservative Party with the Liberal Democrats, for

those with high and low political knowledge. Aside from attitudes toward taxation and

knowledge, all other variables are set to their means. Recall that high values on the attitude

scale represent right-wing attitudes—i.e., they favour tax cuts rather than government

spending. There is no obvious relationship between attitudes towards taxation and voting

between the Labour Party and the Liberal Democrats—the probabilities of voting Labour

for both the highly knowledgeable and less knowledgeable are fairly constant regardless of

where respondents stand on the issue. The situation is similar for vote choice between the

Conservative Party and Liberal Democrats for the less knowledgeable—again the

probability remains fairly stable regardless of one’s viewpoint on the issue. However, the

interaction between knowledge and attitudes towards taxation is large and statistically

significant for the Conservative/Liberal Democrat contrast. Here we see the expected

pattern among the knowledgeable of right-wing attitudes being associated with higher

propensities to vote for the Conservative Party. In fact, the relationship is very strong, with

Political Knowledge and Electoral Choices by

Robert Andersen,Anthony Heath and Richard Sinnott

14

the probability at about .1 for those on the far left, and .7 for those on the far right of the

issue.

Labour/Liberal Democrat

0.0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

0.9

1.0

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11

Attitudes toward taxation

low knowledge

high knowledge

Labour/Liberal Democrat

0.0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

0.9

1.0

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11

Attitudes toward privatisation

low knowledge

high knowledge

Figure 1 Fitted probabilities of voting Conservative and Labour versus Liberal Democrat by attitudes toward taxation, low and high party policy knowledge

Political Knowledge and Electoral Choices by

Robert Andersen,Anthony Heath and Richard Sinnott

15

We now turn to Figure 2 to assess the effects of knowledge on the relationship between

attitudes toward privatisation and vote. Here we see a similar pattern to that observed in

Figure 1. Once again knowledge has little impact on the Labour/Liberal Democrat contrast,

but a dramatic impact on the Conservative/Liberal Democrat contrast. Neither the highly

knowledgeable nor the less knowledgeable appear to choose the Labour Party over the

Liberal Democrats based on their stances on the privatisation issue. In some respects this

is not surprising since, although the Liberal Democrats were to the left of Labour on the

issue, the distance between the two parties was not dramatic. On the other hand, there is a

large difference in Conservative and Liberal Democrat policy on the issue, and this is

reflected in the attitude-vote relationship, but only for the highly knowledgeable. Among

the highly knowledgeable, those who are far on the left are highly unlikely to vote

Conservative over Liberal Democrat (p<<.1), while those on the far right of the issue are

highly likely to choose the Conservative Party (p=.7). In other words, those who are

unaware of the party positions on the issue are not matching their vote choices to their own

preferences as well as the knowledgeable are.

Political Knowledge and Electoral Choices by

Robert Andersen,Anthony Heath and Richard Sinnott

16

Labour/Liberal Democrat

0.0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

0.9

1.0

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11

Attitudes toward privatisation

low knowledge

high knowledge

Conservative/Liberal Democrat

0.0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

0.9

1.0

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11

Attitudes toward privatisation

low knowledge

high knowledge

Figure 2

Fitted probabilities of voting Conservative and Labour versus Liberal Democrat by attitudes toward privatisation, low and high party policy knowledge

Political Knowledge and Electoral Choices by

Robert Andersen,Anthony Heath and Richard Sinnott

17

Figure 3 displays the effects of knowledge on the relationship between attitudes toward

European integration and vote. The pattern in this figure clearly differs from those for the

other issues for two reasons. First, the relationship between attitudes and vote tends to be

in the correct direction for both knowledgeable and less knowledgeable voters. In other

words, for all voters as attitudes toward Europe become more right-wing, voters tend to

become more likely to vote Labour and Conservative rather than Liberal democrat. (Recall

that in the case of taxation and privatisation such a pattern was seen only for the

knowledgeable voters for the Conservative/Liberal Democrat contrast). Moreover, unlike

with the taxation and privatisation issues, we find significant interactions between

knowledge and attitudes for both the Conservative/Liberal Democrat and Labour/Liberal

Democrat contrasts. In both cases, those with knowledge of party platforms are more likely

match their own political ideology to the party best representing that ideology.

Political Knowledge and Electoral Choices by

Robert Andersen,Anthony Heath and Richard Sinnott

18

Labour/Liberal Democrat

0.0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

0.9

1.0

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11

Attitudes toward European integration

low knowledge

high knowledge

Conservative/Liberal Democrat

0.0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

0.9

1.0

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11

Attitudes toward European integration

low knowledge

high knowledge

Figure 3 Fitted probabilities of voting Conservative and Labour versus Liberal Democrat by attitudes toward European integration, low and high party policy knowledge

Political Knowledge and Electoral Choices by

Robert Andersen,Anthony Heath and Richard Sinnott

19

Discussion

This paper set out to assess the effects of political knowledge on political choices. Our

primary goal was to show that issue voting does take place, but that it is conditioned on

knowledge of party platforms. In other words, voters do vote according to issues, but they

can do this properly only when they have knowledge of the party platforms on the issues.

Our results provide significant evidence that this is in fact true. We found significant

interactions between knowledge and positions on issues and their impact on vote for all

three issues that we examined. Those with higher knowledge, in all cases, were more

likely to match their own issue positions to parties with similar positions. These findings

indicate that, contrary to the argument of some political scientists, errors in vote choices

made by the less knowledgeable do not cancel each other out. This suggests, then, that

election outcomes could be considerably different if the electorate as a whole was

generally well informed about the party platforms.

Our analysis also showed that the effects of knowledge on issue voting were most

pronounced for the Conservative/Liberal Democrat contrast. For each of the three issues

knowledgeable respondents were far more likely to match their issue preferences to party

platforms than for the less knowledgeable. Of course, we expected this to be the case given

that the Conservative Party and Liberal Democrats occupy the opposite ends of the left-

right spectrum for all the issues.

The findings with respect to the Labour Party/Liberal Democrat vote contrast do not fit the

expected pattern, however. Only for Europe was there an interaction effect between

knowledge and position on issues on Labour/Liberal Democrat vote. This interaction was

in the expected direction—i.e., the knowledgeable were more likely to vote Labour the

more right-wing they were—but even here the knowledgeable were much more likely to

vote Labour even if they were on the extreme left of the issue. In fact, this pattern held up

for all the issues. That is, with all issues even the knowledgeable were more likely to vote

Labour regardless of whether they were left or right. This suggests, perhaps, that the public

Political Knowledge and Electoral Choices by

Robert Andersen,Anthony Heath and Richard Sinnott

20

realised that the differences in policy between Labour and the Liberal Democrats was

relatively small, and that the Labour Party was seen as a more viable party to achieve

election.

It is interesting that the main effects of all three knowledge variables had a positive impact

on vote for the Liberal Democrats. This suggests that a continuing problem for the Liberal

Democrats is their lack of visibility to the electorate. Even at the end of the election

campaign, it seems that many voters still do not know where the Liberal Democrats stand

on the issues.

Our results also suggest one reason the Conservative Party’s emphasis on issues such as

Europe failed to deliver the expected gains in votes in 2001. Despite the fact that a

majority of the electorate lie to the right with the Conservatives on the European Union

issue, less knowledgeable voters simply failed to connect their own preferences with

Conservative Party’s platform.

We are not suggesting that issues were of utmost importance to voters. In fact, it is

important to emphasise that issues were generally less important to voters than opinions

towards party leaders, even for those with high political knowledge. Nonetheless, these

results do suggest that knowledge of where parties stand on issues does induce a stronger

relationship between issue preferences and vote. It is also highly likely that changes in

party positions on the issues for the 2001 election made knowledge even more important

than in the past. Less knowledgeable voters, who might continue to use out-dated rules of

thumb, seemed much more likely to make incorrect voting choices. In conclusion, our

results suggest that knowledge of party platforms does affect electoral choices.

Political Knowledge and Electoral Choices by

Robert Andersen,Anthony Heath and Richard Sinnott

21

References Bara, J. and I. Budge (2001) ‘Party Policy and Ideology: Still New Labour’, Pp. 26-42 in P. Norris (ed.) Britain Votes 2001. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Bartels, L. (1996) ‘Uninformed Votes: Information Effects in Presidential Elections’, American Journal of Political Science, 40: 194-230. Bartle, J. (1997) ‘Political Awareness and Heterogeneity in Models of Voting: Some Evidence from the British Election Studies’, Pp. 1-22 in C. Pattie, D. Denver, J. Fisher and S. Ludman (eds), British Elections and Parties Review Volume 7, London: Frank Cass. Brody, R. A. and B.I. Page (1972) ‘Comment: The Assessment of Policy Voting’, American Political Science Review 66:459-65. Budge, I. (1999) ‘Party Policy and Ideology: Reversing the 1950s? in G. Evans and P. Norris, (eds.), Critical Elections: British Parties and Voters in Long-Term Perspective. London: Sage. Carmines, E.G. and J.A. Stimson (1980) ‘The Two Faces of Issue Voting’, American Political Science Review 74: 78-91. Carmines, E.G. and J.A. Stimson (1989) Issue Evolution: Race and the Transformation of American Politics. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Delli Carpini, M. and S. Keeter (1996) What Americans Know about Politics and Why it Matters. New Haven: Yale University Press. Fiorina, M. (1981) Retrospective Voting in American National Elections. New Haven: Yale University Press. Fishkin, J. (1997) The Voice of the People. New Haven: Yale University Press. Fishkin, J. (1999) Democracy and Deliberation: New Directions for Democratic Reform. New Haven: Yale University Press. Fox, J. (1987) ‘Effect Displays for Generalized Linear Models,’ in C.C. Clogg (ed.) Sociological Methodology 1987. Washington: American Sociological Association. Graber, D. (2001) Processing Politics. Learning from Television in the Internet Age. Chicago: Chicago University Press. Kessel, J.H. (1972) ‘The Issues in Issue Voting’, American Political Science Review 66:459-65.

Political Knowledge and Electoral Choices by

Robert Andersen,Anthony Heath and Richard Sinnott

22

Key, V.O. (1969) The responsible Electorate: Rationality in Presidential Voting, 1936-1960. New York: Vintage Books. Lewis-Beck, M. (1988) Economics and Elections: The Major Western Democracies. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. Luskin, R. (1987) ‘Measuring Political Sophistication’, American Journal of Political Science 31:856-99. Lupia, A. (1994) ‘Shortcuts Versus Encyclopedias: Information and Voting-Behavior in California Insurance Reform Elections’, American Political Science Review 88: 63-76. Lupia, A. and M.D. McCubbins (1998) The Democratic Dilemma. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Neuman, W.R., M. Just and A. Crigler (1992) Common Knowledge. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Norris, P. and J. Lovenduski (2001) ‘The Iceberg and the Titanic: Electoral Defeat, Policy Moods, and Party Change’, Paper presented at the Elections, Public Opinion and Parties (EPOP) annual conference, University of Sussex, September 2001. Page, B.I. and R. Shapiro (1992) The Rational Public: Fifty Years of Trends in Americans’ Policy Preferences. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Popkin, S. (1994) The Reasoning Voter. Chicago: Chicago University Press. Shapiro, R.Y. and B.I. Page (1988) ‘Foreign Policy and the Rational Public’, Journal of Conflict Resolution 32:211-47. Schumpeter, J. (1942/1967) ‘Two Concepts of Democracy’, in A. Quinton (ed.) Political Philosophy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Sinnott, R. (2000) ‘Knowledge and the position of attitudes to a European foreign policy on the real-to-random continuum’, International Journal of Public Opinion Research 12:113-137. Sniderman, P., R. Brody, P. Tetlock (1992) Reasoning and Choice: Explorations in Political Psychology. New York: Cambridge University Press. Stewart, M.C. and H.D. Clarke (1992) ‘The (Un)Importance of Party Leaders: Leader Images and Party Choice in the 1987 British Election’, The Journal of Politics 54:447-470.

Political Knowledge and Electoral Choices by

Robert Andersen,Anthony Heath and Richard Sinnott

23

Thomson, K., A. Park, and L. Brook (1999) British General Election Study 1997: Cross-section Survey, Scottish Election Study and Ethnic Minority Study Technical Report. London: National Centre for Social Research. Zaller, J. (1992) The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.