Political History of the Kyklades, 1993

Transcript of Political History of the Kyklades, 1993

The Political History of the Kyklades 260-200 B.C.Author(s): Gary RegerReviewed work(s):Source: Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte, Bd. 43, H. 1 (1st Qtr., 1994), pp. 32-69Published by: Franz Steiner VerlagStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4436314 .Accessed: 25/05/2012 22:52

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range ofcontent in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new formsof scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

Franz Steiner Verlag is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Historia:Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte.

http://www.jstor.org

THE POLITICAL HISTORY OF THE KYKLADES 260-200 B.C.

For most of the third and second centuries B.C., the Kyklades islands lived under the suzereignty of an outside power. From 314 to 288 B.C. first Antigonos Monophthalmos and his son, and then Demetrios Poliorketes alone, controlled them through the Nesiotic or Island League which Antigonos had organized. In 288 B.C. the Ptolemies seized the League and maintained a visible presence in the central Aegean until the end of the Khremonidean War in 261 B.C. During the course of the Second Makedonian War the Rhodians collected the islands and soon re-organized the League, which had fallen into desuetude. The Kyklades continued under Rhodian control at least until 167 B.C.

I I use the following non-standard abbrevations:

Bagnal = Roger S. Bagnall, The Administration of Ptolemaic Possessions outside Egypt, Columbia Studies in the Classical Tradition 4 (Leiden 1976).

BEFAR = Biblioth6que des Ecoles Franqaises d'Ath6nes et de Rome. Berthold = Richard M. Berthold, Rhodes in the Hellenistic Age (Ithaca-London 1984). Briscoe, Comm. XXXI-XXXIII = John Briscoe, A Commentary on Livy Books XXXI-

XXXIII (Oxford 1973). Briscoe, Comm. XXXIV-XXXVII = John Briscoe, A Commentary on Livy Books XXXIV-

XXXVII (Oxford 1981). Bmld = Pierre Bruld, La piraterie cretoise hellinistique, Centre de Recherches d'Histoire

Ancienne 27 (Paris 1978). Bruneau, CDH = Philippe Bruneau, Recherches sur les cultes de Delos a 1'e'poque

hellenistique et a VI'poque imperiale, BEFAR 217 (Paris 1970). Buraselis = Kostas Buraselis, Das hellenistische Makedonien und die Agais. Forschun-

gen zur Politik des Kassandros und der drei ersten Antigoniden (Antigonos Monophthalmos, Demetrios Poliorketes und Antigonos Gonatas) im Agaischen Meer und in Westkleinasien, Munchener Beitrage zur Papyrusforschung und antiken Rechtsgeschichte 73 (MUnchen 1982).

Choix = Felix Durrbach, Choix d 'inscriptions de Delos avec traduction et commentaire (Paris 1921-22 [rep. 1977]).

Delamarre = J. Delamarre, " L' influence mac6donienne dans les Cyclades au IIIe si6cle avant J.-C.," Revue de Philologie 26 (1902) 301-325.

van Effenterre = Henri van Effenterre, La Crete et le monde grec, BEFAR 163 (Paris 1968, rep.).

Etienne, Tinos II = Roland Etienne, Tinos, II. Tinos et les Cyclades du milieu du IV' sie'cle avant J.-C. au milieu du Ille siecle apres J.-C., BEFAR 263bis (Paris 1990).

Fraser-Bean = P. M. Fraser and G. E. Bean, The Rhodian Peraea and Islands (Oxford 1954).

Historia, Band XLIIV1 (1994) ? Franz Steiner Verlag Wiesbaden GmbH, Sitz Stuttgart

The Political History of the Kyklades 33

The years from 260 to 200 B.C., in contrast, are very obscure.2 It is clear that Ptolemaic interest declined after 261 B.C., and that by c. 245 B.C. at the latest the Ptolemies had withdrawn, except for their base at Thera. This withdrawal has been connected with, or attributed to, Ptolemaic defeats in the poorly attested battles of Ephesos, Kos, and Andros. The dates assigned to these battles - which have ranged widely - have often determined the framework of the history of the central Aegean. In turn, the Ptolemaic defeats in these three conflicts have been seen as opportuni- ties for either a Makedonian suzereignty in the islands - begun under Antigonos Gonatas, and extending, depending on one's interpretation of some inscriptions, through the reign(s) of Demetrios II, Antigonos Doson, or even Philip V - or a Rhodian predominance beginning either in the 250s or the 230s-220s B.C.

In recent years scholarship has offered dates for the battles that seem to be gaining more and more acceptance: 261 B.C. for Kos, c. 258 B.C. for Ephesos, and 246 or 245 B.C. for Andros.3 Thanks to this new general agreement, it has become possible, I think, to defend a reconstruction of the history of the Kyklades in the second half of the third century which takes into account all of the evidence,

Fraser-Roberts = P. M. Fraser and C. H. Roberts, " A New Letter of Apollonius," Chronique d'Egypte 47 (1949) 289-294.

GD3 = Philippe Bruneau and Jean Durat, Guide de Delos3 (Paris 1983). Hammond-Walbank = N. G. L. Hammond and F. W. Walbank, A History of Macedonia,

Volume Ill. 336-167 B.C. (Oxford 1988). Heinen = Heinz Heinen, Untersuchungen zurhellenistischen Geschichte des 3. Jahrhun-

derts v. Chr., Historia Einzelschrift 20 (Wiesbaden 1972). Holleaux, Etudes II, II, IV = Maurice Holleaux, Etudes d'epigraphie et d'histoire

grecques H (Paris 1938), III (Paris 1968), IV (Paris 1952). Huss = Werner Huss, Untersuchungen zur Auqfenpolitik Ptolemaios' IV., Miinchener

Beitrage zur Papyrusforschung und antiken Rechtsgeschichte 69 (Miinchen 1976). LGPN I = P. M. Fraser and E. Matthews, eds., A Lexicon of Greek Personal Names,

Volume I. The Aegean Islands, Cyprus, Cyrenaica (Oxford 1987). Reger-Risser = Gary Reger and Martha Risser, "Coinage and Federation on Hellenistic

Keos," in Landscape Archaeology as Long-Term History: Northern Keos in the Cycladic Islands, ed. J. F. Cherry, J. L. Davis, and E. Mantzourani, Monumenta Archaeologica 16 (Los Angeles 1991) 305-317.

Will 12 = tdouard Will, Histoire politique du monde hellinistique (323-30 av. J.-C), Annales de L'Est 30, vol. I, 2nd. ed. (Nancy 1979).

My research in Athens and the Kyklades in the summers of 1990 and 1991 was supported by grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities (FT-34298-90; FE-26248-9 1). I am also grateful to Trinity College for research support in the summers of 1988 and 1991, and to my research assistant Jennifer Chi.

2 Another very obscure period, after 167 B.C. to the end of the Hellenistic period, I hope to treat in another article, "When Did the Kyklades Become Part of the Province of Asia?"

3 Walbank in Hammond-Walbank 587-600; Buraselis 119-151; G. Reger, "TMe Date of the Battle of Kos," AJAH, forthcoming (disputing Buraselis' suggestion of 255 B.C. for Kos).

34 GARY REGER

exiguous as it is, without pretending that all the very grave difficulties that continue to plague the epigraphical material have been definitively solved. Indeed, in the view that I will put forward, the dating of this material becomes less crucial, and the battles, given their new dates, have their place, but not a decisive one, in deter- mining the fate of the islands.

I. Summary of the Argument

It may be useful to summarize my reconstruction of the islands' political history before proceeding to a detailed discussion of the evidence on which it is based.

From 288 B.C. until the end of the Khremonidean War in 261, the Ptolemies had used the Kyklades as a staging-ground for incursions into mainland Greece. The collapse of that policy after 261 materially reduced the appeal of the islands to the Egyptian kings. No nesiarkhos of the Island League, which had functioned as the Ptolemaic instrument for administration of the islands, is certainly known after about 260 B.C., and the number of Ptolemaic dedications to the sanctuary of Apollo on Delos drops off sharply. Further defeats in the Second Syrian War, including especially the naval loss off Ephesos at which the Ptolemies' long-time Rhodian allies fought for the Seleukids, further reduced Egyptian interest in the central Aegean. The Rhodians took this opportunity to swoop down on the Kyklades and establish a degree of control exemplified by an alliance with los; presumably they sought similar agreements with other islands.

This phase of Rhodian "predominance" did not last long. The Ptolemies re- asserted themselves after the end of the Second Syrian War in 253 B.C. Their presence in the central Aegean, however, was neither as pervasive nor as committed as in the 280s to 260s because it did not correspond to a renewed policy of intervention in Greece. No nesiarkhos is attested, nor other officials known from the earlier hegemony; and the establishment of new Ptolemaieia on Delos in 249 and 246 B.C. can be attributed as much to piety and tradition as to advertisement of political hegemony.

The battle of Andros, fought in the opening year of the Laodikean (Third Syrian) War, marked the final retreat of the Ptolemies from the central Aegean, culminating a process that had been going on for fifteen years. The Ptolemaic commitment in the late 250s and early 240s was not comparable to that of the earlier period; it answered no great policy needs; and when Antigonos Gonatas came with his fleet, the Ptolemies were much more concerned about events in Asia Minor, a region to which they had made a genuine commitment. As a result, the defeat pushed the Ptolemies out of the central Aegean - except of course for their garrison at Thera - but cannot be regarded as a tuming-point.

Further evidence for this view comes from the results of that defeat. The Makedonians under Gonatas did not become hegemones of the Kyklades. The

The Political History of the Kyklades 35

evidence for their presence - a series of poorly dated, often fragmentary inscriptions mentioning a "King Antigonos" who could often be either Gonatas or Doson, and some better dated epigraphical material from Delos - shows not a general hegemo- ny, but a clear interest in the islands that ring the mouth of the Saronic Gulf. This pattem can be explained by a desire on the part of the Antigonid kings to protect the approach to Athens, which was threatened in the Khremonidean War, and by the loss between 253 and 246 of Euboia to Alexandros the son of Krateros. Antigonid interest in Delos, on the other hand, is well attested and persistent; but the island was a pan-Hellenic sanctuary which called forth dedications from many dynasts, and the Antigonid dynasty itself had long-standing pious relations with the birth- place of Apollo which no scion of Monophthalmos would be likely to neglect.

Evidence for Rhodian control or hegemony in the Kyklades, claimed both for the period 250-200 B.C. and more modestly for the years after about 230-220 B.C., is weak and unpersuasive. Indeed, the best reconstruction of the political history of the Kyklades in the second half of the third century attributes to them political independence from the great powers and a degree of isolation. It was only toward the end of the century that the Rhodians became increasingly attracted to the islands and then took the opportunity presented by the Second Makedonian War to seize the islands and create a new Island League headquartered at Tenos and serving as the instrument of Rhodian hegemony.

Since a good deal of the evidence we have for the Hellenistic Kyklades comes from inscriptions, we need to consider the reliability of the dates given for these documents before we can try to reconstruct the history of the islands. The next section is devoted to a brief exploration of the methods, results, and problems related to dating inscriptions by style of lettering.

II. Letter-Form Dating

Whereas the accounts and inventories for Delos are precisely dated thanks to the existence of full lists of Delian arkhontes, exact absolute dates are impossible to obtain for most other Kykladic inscriptions - including Delian decrees, which are never dated by arkhon. Consequently, we depend almost entirely on letter-forrns to date these inscriptions. It is therefore worthwhile to pause briefly to set out the development of lettering in the islands for the second half of the third century, and to emphasize the uncertainties that this method adds to our study.

The stylistically most diagnostic letter-forms for the second half of the third century are the alpha, the pi, the sigma, and the mu. The presence and absence of serifs ("apices" ) can also be important.

Alpha. By mid-century the older form of the alpha with a straight cross-bar was finding competition in a new form, the so-called bowed alpha, which shows a curved cross-bar. The bowed alpha occurs by c. 250 B.C. on Delos and persists

36 GARY REGER

commonly in the accounts and inventories until the end of the century and occasion- ally even later.4 Bowed alphas make their appearance on Paros in the second half of the third century and on los probably at about the same time or a bit later (last third of the century?).5 In tum a still newer form, the broken-barred alpha, whose crossbar forms an angle pointing down, developed toward the last third of the third century. It appeared at Hierapytna on Krete by 224-222 B.C. (though mixed with predominating bowed alphas), on Delos by c. 220 B.C. (though it did not predomi- nate until about 190 B.C.), in Athens c. 210 B.C., by 205 B.C. at Magnesia on the Maiandros, on Paros no later than 201 B.C., and by c. 200 B.C. at Sardis. This new form co-existed everywhere with the older bowed-bar alpha until the first decade of the second century.6 These changes support a loose rule: the presence of only bowed alphas cannot be used to date a text more closely than "second half of the third century," since documents from those years can easily have only bowed alphas;7 on the other hand, the presence of some broken-barred alphas precludes a date before about 225 B.C. at the outside, and probably indicates even a later dating. This rule will prove very helpful.

4 IG XI 2.206, 287; IG XI 4.1052 (= Choix 45), Tabula III; cf. IDelos 313, 320, 353, and 372

(235-200 B.C.) apud IG XI 3, Tabulae I-HI; IDe'los 401 (189 B.C.). IG XI 4.1105 has bowed

alphas only, cf. the photograph at RA (1989) 294 pl. 32. J. Trdheux has associated the lettering

of this stone with IG XI 2.287 for a date of c. 250 B.C. (apud F. Queyrel, RA [ 19891 287-288),

but there are differences (for example, 1105 has widely splayed sigmas whereas in 287 they

are essentially straight).

5 Paros: IG XII 5.111, 445 (mixed with broken-bars), W. Lambrinudakis and M. Worrle, "Ein

hellenistisches Reformgesetz tiber das offentliche Urkundenwesen von Paros," Chiron 13

(1983) 283-368 (which I believe is not quite as recent as the editors think), SEG 15.517. los:

IG XII 5.2, 1002, 1011 (= L6opold Migeotte, L'emprunt public dons les cites grecques

[Quebec-Paris 1984] 210-212 no. 60; 1002 and 1011 must be fairly close in date since they

share the same rogator). The Tenian texts are not as diagnostic since most cannot be

independently dated; bowed-bar alphas at IG XII 5.798, 814, 825 (autopsy), IG XII Suppl.

313 (cf. sketch at P. Graindor, Musee Belge I [ 19101 45; Hiller's date at IG XII Suppl. p. 138),

Etienne, Tinos H 102-106 no. 4 (his Planche XI), Etienne, Tinos II 267-268 no. 25 (Planche

XIV.2). IG XII 5.714 from Andros, dated to 357/6-336 B.C. by Theophil Sauciuc ("Zum

Ehrendekret von Andros IG XII 5,714," AM 36 [1911 1-20) but which has bowed-bar alphas,

belongs in my view in the third century; cf. "The Date and Historical Significance of IG XII

5.714 of Andros," Hesperia (forthcoming).

6 ICret III Hierapytna IA with R. M. Errington, "The Macedonian 'Royal Style' and its

Historical Significance," JHS 94 (1974) 35 (cf. also n. 1 14); P. Roussel apud G. Leroux, La

salle hypostyle, Exploration arch6ologique de D6los II (Paris 1909) 49-50 n. 1 on Delos, cf.

also IG XI 4.1097, Tab. VI; Wilhelm Larfeld, Handbuch der griechischen Epigraphik 11.2

(Leipzig 1902) 472-478 on Athens; . v.Mag. 18 with Tab. III.2 for Magnesia; Lambrinudakis

and Worrle (as in n. 5) 290 on IG Xn 5.125, cf. also SEG 15.517; on Tenos, IG XII 5.868B (=

ICret I Tylissos 2, cf. Etienne, Tenos 11 119 n. 72), IG XII 5.825. Louis Robert, Nouvelles

inscriptions de Sardes (Paris 1964) 10. Generally, Holleaux, Etudes II 76-77 n. 3.

7 E.g., IDelos 313, 320, 353, and 372 (235-200 B.C.) apud IG XI 3, Tabulae I-Ill (Delos); ICret

IV 167 (reign of Demetrios II, 239-229 B.C.), II Eleutherai 20 (224-222 B.C., cf. Errington

[as in n. 6] 35 with n. 98).

The Political History of the Kyklades 37

Pi. The forms of pi are variable, but some changes can help with dating. Through much of the third century, pi tends to be carved with a shorter right hasta. Later the horizontal crossbar often extends beyond the hasta on the right; in Athens, this form first appears in the 260s, but it does not become frequent until after about 250 B.C. Delos shows a complex development. Pis with equal hastae appear in the 280s, but examples with short right hastae can be documented from the early third century, 250 B.C., and 240-220 B.C. Strikingly, pis with horizontal bars that extend beyond the right hasta, which elsewhere appear only later, can be found in an inscription dated to the beginning of the third century, in another honoring a Delian who died between 269 and 257 B.C., and in a third from the beginning of the second century. Krete displays similar complexities: the alliance of Gortyn with Demetrios II (hence of 239-229 B.C.) has only pis with shorter right hastae, but the alliances Antigonos Doson struck with Hierapytna and Eleutherai have pis whose horizontal extends beyond the hastae on both sides; at Eleutherai these appear side by side with the more traditional pis.8 On Paros the very transitional text SEG 15.517, which has both bowed- and broken-bar alphas, also has pis whose horizontals both do and not extend to the right. Right projecting pis appear also in IG XI 5.445 in the company of both styles of alphas and in IG XII 5.186 with broken-bar alphas only. Pis whose horizontals project on both the right and left seem to associate exclusively with broken-bar alphas (IG XHI 5.129, 130, 135). For Paros this combination may mark distinctly second-century texts. The same may be true on Andros,9 whereas on los the simple pi with a short right hasta but no overhang seems to persist late into the third century. 10 On Keos and Tenos pis projecting both to the right and the left occur in texts with admixed bowed- and broken-barred alphas. 1 I It is therefore difficult to make a rule as clear for pi as for alpha, but in general, unless other considerations (including the forms of other letters) intervene, pis with horizontals extending beyond the right hasta are likely to point toward a date in the later third century.

Sigma and mu. For these two letters the distinctive characteristic is whether the outer hastae diverge ("splayed" ) or run straight. The splayed versions are generally earlier, but in fact these letters can vary widely. On Delos, for example, IDelos 338

8 Athens: Larfeld, Handbuch (as in n. 6) 470-474. Delos: IG XI 4.562, 280-270 B.C., Tab. I (equal), 543, early HI, Tab. II, 1050, 250 B.C., Tab. III, 681-682, 240-220 B.C., Tab. I (shorter right); 1072 (= Choix 14), beg. III, Tab. VI, 1049, Tab. Ill (for the honorand see Claude Vial, Delos independante [314-167avant J.-Cl1. ttude d'une communaute civique et de ses institutions, BCH Suppl. 10 [Paris 1984] 136), 752, beg. HI, Tab. IV (shorter right, overhang). Krete: ICret IV 167, III Hierapytna IA, H Eleutherai 20 (cf. Errington [as in n. 61 35).

9 Cf. IG XII 5.719, second century (IG XII Suppl., p. 120), 722, 106 B.C. (G. Reger, "The Decree of Adramytteion for an Andrian Dikast and his Secretary [IG Xll 5.722, 23-44]," EA 15 [1990] 1-5).

10 Cf. the texts at n. 5 above. 11 IG XII 5.599; IG XII 5.825, 868B (cf. n. 6 above).

38 GARY REGER

of 224 B.C. mixes splayed mus and straight sigmas, but IDelos 366 of 207 B.C. has only splayed forms. Straight sigmas seem to appear quite early (IG XI 2.206, 260s B.C.; 269, 260-250 B.C.), but the splayed form may persist into the second century (IDelos 465, c. 170 B.C.).12 At Paros the development was apparently simpler. Splayed sigma's do not appear in texts clearly of the second century;13 instead, they are associated with texts showing a mixture of bowed- and broken-bar alphas: clearly transitional.'4 The same is true on Andros.'5 The picture on los is less clear, since splayed sigmas seem to be the rule throughout the third century; this "retarda- tion" echoes the behavior of pi noted above. On Krete splayed and straight sigmas and splayed and straight mus mix in the treaties of Demetrios II and Doson.16

Serifs. These decorative additions to the ends of strokes, especially common on pis, sigmas, and other "big" letters, develop gradually from the late third century. Very fancy or noticeable serifing marks later second century texts, as for instance IG XII 5.722 of Andros or many of the Tenian texts that date roughly 190-170 B.C.17

Caution must have the last word. Dates derived entirely from letter-forms have often proven grossly mistaken or misleading. To cite but two examples from Delos, which has provided abundant evidence for the development of letter-forms: F. Durrbach had dated IDelos 373 to 200 B.C. on the basis of its lettering, but J. H. Kent showed that the inscription actually belonged in 180 B.C.'8 The Delian monument celebrating Doson's victory over Kleomenes III of Sparta at Sellasia shows exclusively broken-barred alphas, slightly splayed sigmas and mus, and fine but clear serifs (unfortunately the preserved text contains no pi), but it dates not to

12 Various dates have been offered for this text; cf. on fr. c, M.-F. Baslez and C. Vial, BCH I I 1 (1987) 290 n. 42, showing it belongs in 171 B.C. I hope to show elsewhere that this fragment belongs to the text to IDelos 460t and 460v.

13 E.g., IG XII 5.129, 130, 135, 186; Chiron 13 (1983) 283-286.

14 IG XII 5.11 1; SEG 15.517. 15 Splayed: IG XII 5.714, cf. IG XHI Suppl., p. 1 19 (on the date as second or third quarter of the

third century, see G. Reger, "The Date and Historical Significance of IG XII 5.714 of Andros," Hesperia [forthcoming]); IG XII 5.715. Straight: IG XII. 5.717, last quarter of the third century (cf. Theophil Sauciuc, Andros. Untersuchungen zur Geschichte und Topogra- phie der Insel, Sonderschriften des Osterreichischen Archaologischen Instituts in Wien, Band 8 [Vienna 1914] 146-147), 719 (cf. IG XII Suppl., p. 120), 722, 106 B.C. (cf. Reger [as in n. 91 1-5).

16 Splayed mus and sigmas: ICret III Hierapytna IA (224-222 B.C.); straight mus, splayed sigmas: ICret IV 167 (239-229 B.C.); straight sigmas: ICret II Eleutherai 20 (224-222 B.C.).

17 IG XH 5.819, 821, 830, etc. Cf. also Robert (as in n. 6) 10.

18 IDllos 373, c omm., p. 18: "le type de l'ecriture et le montant des loyers ... mettent la date hors de doute"; John Harvey Kent, "Notes on the Delian Farm Accounts," BCH 63 (1939) 241- 242.

The Political History of the Kyklades 39

the end of the century but in or soon after 221 B.C.19 It may be that the Delians found this style especially appropriate for large letters on monumental texts, as opposed to a more conservative feel about the lettering of accounts or decrees; we encounter very similar lettering in IG XI 4.1100 (= Choix 57), Philip V's dedication of his portico, which is dated to 220-217 B.C. Moreover, local variation in letter styles may obscure patterns of change known from other regions. The rate of adoption of changes, like the broken-barred alpha, surely depended also on the tastes and training of individual masons and customers, on the sense of the appro- priateness of certain lettering styles to certain documents, on the typical annual demand for inscribing, and on other, perhaps unrecoverable, factors. Despite these difficulties, letter-forms can give more precise dates for some inscriptions than have been offered; in particular, we will see that three Amorgan inscriptions that mention a "king Antigonos" are more likely to refer to Doson than Gonatas. This discovery clarifies the history of the central Aegean in the last third of the third century.

m. Discussion of the Evidence

A. The Character of the First Ptolemaic Hegemony (288-c. 260 B.C.)

The great heyday of Ptolemaic presence in the Kyklades fell in 288-261 B.C. These dates correspond at one end to the liberation of Athens, now much better understood from the Athenian decree for Kallias,20 and at the other to the end of the Khremonidean War. In other words, Ptolemaic control over and interest in the Kyklades correlates perfectly with the period when Egypt was most committed to a mainland policy. This is reasonable. The normal routes of travel attested from the fifth century B.C. through the theorodokoi lists of Delphoi down to the early modern period run from Attika through the Kyklades to Kos and Asia Minor.21 Kykladic Islands, and especially the western ones, thus form a natural base from which to operate against the mainland. When Ptolemaios I sent his general Polemai- os to the Peloponnesos in 308 B.C., he first secured Andros as an operational base. Andros was again the Ptolemaic stepping-off point for Kallias and his forces come

19 IG XI 4.1097 with Tab. VI = Choix 51. The single bowed alpha of 1. 1 was in fact carved late in the second century: cf. Holleaux, Etudes m 56.

20 T. Leslie Shear, Jr., Kallias of Sphettos and the Revolt of Athens in 286 B. C., Hesperia Suppl. 17 (Princeton 1978); Christian Habicht, Untersuchungen zur politischen Geschichte Athens im 3. Jahrhundert v. Chr., Vestigia 30 (Munich 1979) 47-49.

21 Plut., Per. 17; Strabo 486C. Andrd Plassart, "Inscriptions de Delphes. La liste des thdorodo- ques," BCH 45 (1921) 1-85 (for the date, see now Miltiade B. Hatzopoulos, BCH 115 [1991 ] 345-347). Georges Rougemont, "Amorgos colonie de Samos?," in Les Cyclades. Materiaux pour une etude de ge'ographie historique. Table ronde r6unie a l'Universite de Dijon les 11, 12 et 13 mars 1982, Editions du Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (Paris 1983) 131-134.

40 GARY REGER

to assist the Athenians in 287 B.C. During the Khremonidean War the Ptolemaic admiral Patroklos garrisoned Itanos, Thera, and Keos, where he changed the name of Koresia to Arsinoe.22 In the cities of the Kyklades these years saw Egyptian intervention to settle disputes, the award of honors by the Island League to high court officials in Alexandria, and the passage of the Nikouria decree recognizing the establishment of games in honor of Ptolemaios I Soter. Likewise on Delos the great majority of dedications and festivals due to the Ptolemies date to the reign of Soter and the earlier years of Philadelphos.23

After the Khremonidean War, however, Egypt abandoned its mainland pol- icy.24 The Ptolemies became more pre-occupied with the Levant and Asia, fighting the Second (260-253 B.C.) and Third (246-241 B.C.) Syrian Wars. Ptolemaic interest in the islands ebbed after Egypt turned away from mainland Greece. That the Ptolemies continued to have strong interests in parts of the Aegean and its littoral, and were willing to spend the money and the manpower to maintain them, is proven by their control of Itanos, Thera, Ainos and Maroneia in Thrake, Samos, and other places. When the Kyklades lost their interest, the Ptolemaic commitment to holding them ended. By the 250s the political situation in the central Aegean had changed.

The battle of Kos belongs sometime in this period. In my view, the more traditional date of 261 B.C., favored by Heinz Heinen and Edouard Will, among others, must be preferred to 255 B.C., recently argued by Kostas Buraselis and F. W. Walbank.25 Since I have argued my views extensively elsewhere,26 I will only summarize my results here. Although Buraselis offers some powerful arguments in favor of the later date, they do not hold up on closer inspection. The key to his case lies in the association of a notice in Eusebius' Chronicon that Gonatas freed Athens

22 Diod. 20.37.1; Kallias decree (cf. n. 20), line 19; ICret III Itanos 2-3 with Bagnall 120-121;

IG XHI 3.320; Louis Robert, "Sur un d6cret des Kor6siens au Musee de Smyrne," Hellenica

XI-XH (1960) 132-176. 23 Intervention: IG XII 3.320 (Thera); IG XII 5.1065 (Karthaia); IG XII 5.7 with p. 301 and IG

XII Suppl. p. 96 (los); Holleaux, Etudes HI 27-37 (Naxos); IG XII 7.14 with p. 127 and 15

with IG XII Suppl. p. 142 (Amorgos); Island League decrees: IG XI 4.1037-1039, 1041-

1043; Nikouria decree: IG XII 7.506 = SIG3 390; dedications and festivals: Bruneau, CDH

516,519-523. 24 See esp. Will 12 161-168, but cp. also the activities of Glaukon, Roland Etienne and Marcel

Pidrart, "Un decret du Koinon des Hellenes a Platdes en l'honneur de Glaucon, fils d'Ettocl6s,

d'Athenes," BCH 99 (1975) 51-75. On the Glaukon decree, see William C. West, "Hellenic

Homonoia and the New Decree from Plataea," GRBS 18 (1977) 307-319; R. Etienne, "Le

Koinon des Hellenes a Platees et Glaucon, fils d'Eteocles," in La Beotie antique (Paris 1985)

259-263; Andrew Erskine, The Hellenistic Stoa. Political Thought and Action (Ithaca 1990)

91-92. 25 Heinen 193-197; Will 12 232-233, with further references. Buraselis 141-144, Walbank in

Hammond-Walbank 291-295,595-599. 26 G. Reger, "The Date of the Battle of Kos," AJAH (forthcoming).

The Political History of the Kyklades 41

in 256/5 or 255/4 B.C.27 with an incident in Diogenes Laertios' biography of the philosopher Arkesilaos (4.39). Arkesilaos is said to have kept silent when "after the sea-battle" many Athenians approached Antigonos with "petitions" (briu-r6Xta 1TapaKXrqTLKd). Buraselis supposes that these petitions asked Antigonos to remove his garrsons. In fact, however, there is nothing to connect these letters with the removal of Antigonos' garrisons. A date of 261 B.C. for the battle of Kos fits the evidence better. Moreover, this date helps to explain why Antigonos' victory did not lead to a Makedonian hegemony in the Aegean (a view argued below): the battle occurred at the end of a long and exhausting war, which had held the Makedonian king's attention for several years. Of course, in a period as obscure as the mid-third century, it is unwise to be dogmatic: new evidence may at any time overturn even the best-founded views.28

B. Rhodian Presence: First Period (c. 258-c. 250 B.C.)

For Delos inscriptions attest Rhodian activity before or around mid-century. The most interesting is a base for a statue of Agathostratos son of Polyaratos erected by T6 KOLV6V TC3V VrCJL&TC3V (IG XI 4.1128 = Choix 38). Most scholars identify Agathostratos with the Rhodian admiral mentioned by Polyainos (5.18) who beat a Ptolemaic fleet in a battle near Ephesos. The Lindos Chronicle confirms a conflict between Rhodos and the Ptolemies, and a general consensus seems to have formed around dating this event to the Second Syrian War, around 258 B.C.29 If this date is correct, it makes this dedication one of the latest known acts of the Island League.30

Agathostratos' title is not given in his dedication, but there survive three further inscriptions from Delos which refer explicitly to Rhodian vavapXoL. One honors

27 Eusebius, Chron. H p. 120 (Schoene); cf. Christian Habicht, Studien zur Geschichte Athens in hellenistischerZeit, Hypomnemata 73 (G6ttingen 1982) 16, cf. 54.

28 F. W. Walbank has recently argued that the Ptolemies suffered an important setback in the Kyklades in 255 B.C. as a consequence of their loss of the battle of Kos. Walbank in Hammond-Walbank 291-295, 595-599; F. M. Walbank, "Sea-power and the Antigonids," in Philip 11, Alexander the Great and the Macedonian Heritage, ed. W. L. Adams and E. N. Borza (Washington 1982) 218-220; Will 12 238-239. On the matter of the Neorion or "Monument des taureaux" (GD3 24), discussed by Walbank at p. 292, see now Jacques Treheux, "Sur le Neorion a Delos," CRAI (1987) 168-184 and "Un document nouveau sur le N66rion et le Thesmophorion A Delos," REG 99 (1986) 293-317.

29 Durrbach, Choix p. 45; Chr. Blinkenberg (ed.), Die Lindische Tempelchronik (Bonn 1915; rep. Chicago 1980) sec. XXXVII, C97-102 (= ILindos 2); Huss 215-216 with n. 288; unnecessary scepticism in Will 12 241; Etienne, Tinos 1 92; Fraser-Bean 103, 155; Buraselis 54-55, n. 63; Jacob Seibert, "Die Schlacht bei Ephesos," Historia 26 (1976) 45-61; Berthold 89-91.

30 Walbank in Hammond-Walbank 294; Will 12 233; Irwin L. Merker, "TMe Ptolemaic Officials and the League of the Islanders," Historia 19 (1970) 159-160.

42 GARY REGER

Antigenes son of Theoros, [allpEdlsg vnr6 TOO 8t5iOU TOO 'Po8twv vcax]pXos T1 ,-ls

vXaySg T[L3V [vYvaV Kai] Tr1C aunrWp(at TL3V 'EAX,vwv.31 Fraser and Bean, who put great emphasis on Antigenes' title, date this decree to 250-220 B.C. and cite it as evidence for Rhodian predominance in the Aegean in the third quarter of the third century.32 But as P. Roussel argued, the letter-forms - straight- and bowed-barred alphas, splayed sigmas, pis with short right strokes but no overhang - definitely belong to before 250 B.C. Prosopographical indications also support the earlier date.33 Roussel has further suggested that Antigenes' title may reflect a police action, not a military operation, which would imply continued operations in the Kyklades even after the conflict with the Ptolemies.34

Another nauarkhos, Peisistratos son of Aristolokhos, and his crew dedicated booty ([dtr]6 T6V XavpfvV) to Apollo; this strongly suggests military operations in or near the Kyklades. Once again, letter-forms and prosopographical considerations suggest a date near 250 B.C.35 Again, a dedication by some Rhodians to Asklepios under the nauarkhos Aristoteles belongs, according to Roussel, before 250 B.C.36 Another decree honoring the Rhodian Hieronidas son of Pythodotos is dated only by letter forms to the mid third century. The mover of the decree, Phillis son of Diaitos, arkhon for 275 B.C., could well have still been active 15 years later.37

Rhodian hostility to her longtime ally is hard to fathom, but Richard Berthold has suggested that the Rhodians saw the growth of Ptolemaic power in the 260s as a threat to the balance of power, and intervened to support Antiokhos II to prevent the recreation of the empire of Antigonos Monophthalmos under Ptolemaic sponsor- ship. Berthold credits the Rhodians with unusual farsightedness and maturity of policy;38 if Rhodos received Stratonikeia from Seleukos II and Antiokhos Hierax in

31 IG XI 4.596.3-5 = Choix 39. 32 Fraser-Bean 158. 33 Cf. IG XI 4, commentary p. 17, cf. Tabula II1. One of Antigenes' tfierarkhoi, 'Hyiaav8pos

BouXdKTcos, was daniourgos at Kamiros in 251 B.C. (M. Segre and I. Pugliese Carratelli, "Tituli Canmirenses," ASAA 27-29 [1947-1951] p. 150, no. 3 Ea29, cf. p. 185, no. 29.1); it may be that he should also be identified with the Rhodian arkhitheoros who visited Delos before 279 B.C. (IG XI 2.161 B 15-16).

34 P. Roussel, "Inscriptions anciennement decouvertes A Delos," BCH 31 (1907) 359 n. 4; cf. Durrbach, Choix p. 46.

35 IG XI 4.1135 = Choix 40, with comm. at IG XI 4, p. 105 for the letter-forms; a Peisistratos was a Rhodian theoros before 250, and possibly before 257, B.C. (IG XI 2.287 B 85; restored at 226 B 5).

36 IG XI 4.1133; cf. 1134, another, but very fragmentary, Rhodian dedication; date ad loc. p. 105.

37 IG XI 4.580, with comm. ad loc., p. 14. Another decree, IG XI 4.614 for the Rhodian Philodamos son of Thars - - -, probably belongs in the years 270-260 B.C.; Philodamos seems to have been the Rhodian theoros who appears in IG XI 2.161 B 17 and 162 B 13 (279 and 278 B.C.). Cf. LGPN I, s.v. 4tX68%aios (17) and (18), Vial (as in n. 8) 134 and n. 42 there.

38 Berthold 91-92. Fear of a "world-monarchy" is cited as a motive for Rhodos to oppose the Ptolemies also by H. van Gelder, Geschichte der alten Rhodier (Haag 1900) 110, who however puts the battle of Ephesos in the Third Syrian War.

The Political History of the Kyklades 43

about 241 B.C., as Berthold argues,39 this grant suggests a developping interest in the mainland, which may have led some among the Rhodians to see a conflict with Ptolemaic claims in Karia. The business remains very obscure, but it may be that immediate political motivations connected with Rhodian possessions on the main- land and relations with the Seleukids determined - or at least played a part in - the Rhodian decision to fight against the Ptolemies.

Rhodian success at Ephesos and the Ptolemaic setback after the Second Syrian War might have created an opportunity for Rhodos to expand her influence in the central Aegean; these documents from Delos, which attest to frequent visits by Rhodian naval officials and belong clearly to the mid-century, are best explained as artifacts of a brief Rhodian predominance in the islands c. 258-250 B.C. There is one more piece of evidence. A very fragmentary inscription from los has been convincingly restored by Adolf Wilhelm to yield an alliance (avpiaXta) between Rhodos and Ios.40 Since, as Hiller von Gaertringer. rightly insisted,4' the letter- forms - alphas with straight bars, splayed sigmas, pis with short right strokes but no overhang - cannot support a date as late as the second century, this inscription cannot record one of the alliances that the Rhodians made with the islanders in the Third Makedonian War (Livy 31.15).42 It would make good sense as part of a strong Rhodian presence in the mid-century, a date which the letter-forms seem to sup- port.43

C. The Period of Ptolemaic Recovery (c. 253/250-246/5 B.C.)

The Rhodian "presence" did not last. The famous Adulis decree (OGIS 54.15) lists the Kyklades among the possessions Ptolemaios mII inherited from his father in January 246 B.C. The mid-century Rhodian presence in the islands was therefore short-lived, a result of Rhodian gains and Ptolemaic losses in the Second Syrian War. The exact circumstances of the Ptolemaic recovery of the central Aegean and the precise character of their control remain however very obscure.44 In principle,

39 Berthold 83-85. 40 IG XII 5.1009 + X1I Suppl. p. 96. 41 IG XII 5, p. 303. Cf. however RE Suppl. 5 (1931), s.v. Rhodos, col. 785, where he gives a

range of 257-220 B.C. 42 A possibility entertained by Etienne, Tinos I 114 n. 51. 43 Compare the photograph of the squeeze published in IG XII 5 p. 303 with the photograph of

IG XI 4.596 (the Agathostratos inscription) at IG XI 4, Tabula HI. The lettering is almost identical.

44 Buraselis 146-147, 168, 170-172; Eugenio Manni, Roma e l'ltalia nel Mediterraneo antico (Torino 1973) 242; Fraser-Roberts 289-294, esp. 294 n. 1; W. W. Tarn, Cambridge Ancient History VII (Cambridge 1928) 715; and similarly Gustave Glotz, "L'histoire de DMlos d'apr6s les prix d'une decr&e," REG 29 (1916) 218-325, cf. 315-316 (for the coins Glotz cited, see Adolphe Reinach, REG 26 [1913] 378 and B. V. Head, Historia Numorum. A Manual of

44 GARY REGER

two possibilities seem most likely. It may be that Ptolemaic control of the islands was recognized in the agreements that ended the Second Syrian War. A Delian inscription of 255 B.C. (IG XI 2.116.2) - one of only three to do so - mentions "peace" (ELpvrq), usually taken as a reference to a peace treaty. Since the Second Syrian War did not end until 253 B.C.45 the only possibility would seem to be a separate peace between Egypt and Rhodos, as E. Bikerman suggested many years ago.46 But given that the Ptolemies were defeated in the battle of Ephesos, and that the war with the Seleukids was still undecided in 255, it seems very unlikely that the Ptolemies could have extracted a Rhodian retreat from the Kyklades in 255. A separate peace in that year would have been much more likely to have recognized the status quo in order to detach the Rhodians from the Seleukids and free Egyptian forces to concentrate against a single enemy. I therefore do not believe that the peace of 255 could have re-established Ptolemaic interests in the central Aegean.

A better context to seek re-assertion of those interests falls in the years after 253 B.C. Three pieces of evidence support a date of 250 B.C., which was first advanced by P. M. Fraser and C. H. Roberts.47 A papyrus they published in 1949 contains instructions from Ptolemaios relayed by his minister Apollonios about the felling of wood for the breastwork of warships, [Trp6s- T]v b'ropE(av TWV LaupK(V yqcav (line 1 1). The letter dates to January 250 B.C. and requires the work to be done no later than 6 February 250 B.C. (lines 9, 18).

In 249 B.C. Ptolemaios II dedicated a new festival on Delos, the Ptolemaieia [II], for which no occasion is known. It is one of a series of royal foundations by kings from several kingdoms.48 These festivals have prompted much discussion; any argument that tries to see them all as answering the same needs is likely to be mistaken. For example, it is virtually certain that the Paneia and Soteria founded in 245 B.C. by Gonatas commemorated his victory over the Egyptian fleet at An-

Greek Numismatics2 [Oxford 1911] 231-232; for the crown, IG XI 2.287 B 63). Objections at Will 12 245, Bruneau, CDH 579-580. Cf. also Will 2 323 on the evidence that the Aegean was at peace in 250-249 B.C.

45 Cf. Willy Clarysse, "A Royal Visit to Memphis and the End of the Second Syrian War," in Studies in Ptolemaic Memphis, Studia Hellenistica 24 (1980) 83-89. For an introduction to the detailed disputes that center around the existence of a treaty to end the war, cf. Will I2 241- 242; Walbank in Hammond-Walbank 292-293.

46 E. Bikerman, "Sur les batailles navales de Cos et d'Andros," REA 4') (1938) 381-382. 47 Fraser-Roberts. The objections of Will 12 245, cited with approval by Bruneau, CDH 579 n. 4

from Will's first edition (Will I [1966] 218), hardly speak to the facts of the case. There is a a passing reference in Ps.-Aristeas to a naval victory by Ptolemaios II over

Gonatas (sec. 180): T& KC[Td Xv v(K11V tVEv TTpocTTErTTKtvaL Trfg Trp6g 'Av-rtyovov

vaulaXtacs (I cite from Aristeas to Philocrates [Letter of Aristeas], ed. and tr. Moses Hadas

[New York 1973]). This naval battle has been associated with the recovery of the islands, but the matter remains difficult: cf. Buraselis 170 n. 198 for discussion and references.

48 Cf. Bruneau, CDH 518-533, 557-568, 570-573. The Roman numerals in brackets are

adapted from Bruneau's notation.

The Political History of the Kyklades 45

dros,49 whereas the Ptolemaieia [HI] of 245 B.C. can be associated with the accession of Euergetes. Since however there is no apparent non-military event (a royal accession, death, marriage, etc.) with which to associate the Ptolemaieia [H] in 249 B.C., it may well be that the festival celebrated the recovery of the islands, and perhaps even a military victory. But this matter remains very obscure.50

Finally, an entry in the Delian accounts for the month of Poseidon 250 B.C. mentions expenses for cleaning up the temple after the departure of a fleet (divixOhi 6 (aT6Xog, IG XI 2.287 A 82). The only analogous expenditure in the Delian accounts occurs in 301 B.C. after a visit by Demetrios Poliorketes, who had a fleet with him.51 Residence in the temple suggests royalty, or representatives of royalty, which can only mean the Antigonids or the Ptolemies. The passage intimates that one or the other - I am inclined to opt for the Egyptians - had a fleet stop at Delos until the end of the year. These three bits of evidence together speak clearly in favor of Ptolemaic recovery of the Kykiades in the course of 250 B.C., between February and the end of the year.52

Roland Etienne has recently pointed out that the erasure of the name of Ptolemaios H from several Delian inscriptions indicates that a renewed Ptolemaic domination cannot have lasted long.53 This strongly supports the supposition that all the documents cited above belong between January and mid-summer 246 B.C.

I have said earlier that Ptolemaic involvement in the Kyklades tended to reflect interests in the Greek mainland, and in this case too there is some evidence to point in this direction. In 253/2 B.C. Alexandros, son of Gonatas' half-brother Krateros, revolted. He held Korinthos and the chief cities of Euboia, and supported the Akhaian League under Aratos. From an inscription of Eretria on Euboia we know that he was proclaimed king, and was petitioned - probably successfully - to remove the garrisons Antignonos had installed. His attack on Athens failed because of the loyalty to Gonatas of the Makedonian garrison and the assistance of the tyrant of Argos. He died in 245 B.C.54 Ptolemaios II supported Alexandros' revolt;

49 Buraselis 144-145. 50 IDelos 298 A 76. Cf. Buraselis 146-147, Fraser-Roberts 292, and Bruneau, CDH 519-520,

523, cf. 579-583. 51 IG XI 2.146 A 76-77; cf. Plut. Dem. 53 and William Scott Ferguson, "Egypt's Loss of Sea

Power," JHS 30 (1910) 193. Cf. also Fraser-Roberts 294 n. 1. 52 Delamarre 321 has argued that a termination and then a revivification of Ptolemaic control in

the Kyklades are "tout A fait inexplicable," but his argument is arbitrary. 53 Etienne, Tinos 11 92, with references at n. 28; IG XI 4.1123, 1126, 1127 = Choix 17, 19, 25,

with Durrbach's remarks at pp. 25-26. 54 Trog., Prol. 26. IG XII 9.212.4 (king), 10-12 (garrisons); IG f2 774.14-21 and 1225.12-13

(attack on Athens); Plut., Aratos 17.2, 18.1-2. B. J. Meritt, Hesperia 30 (1961) 214 no. 9,1. 3

associates this decree with the war with Alexandros: rejected by Heinen 138 n. 188; accepted as "amn wahrscheinlichsten" by Habicht, Studien (as in n. 27) 24 n. 56. On Alexandros' career:

Olivier Picard, Chalcis et la confederation eubeenne. ttude de numismatique et a'histoire (IV'-I" siecle), BEFAR 234 (Paris 1979) 272-274; Will I2 316-324; for a different view, Ralf

46 GARY REGER

indeed, once Aratos of Sikyon had abandoned his friendship with Antigonos and brought his hometown into the Akhaian League, he directly made his way to Alexandria for a meeting with Ptolemaios II to beg for money, which he received (250 B.C.).55 With new allies in Greece and Antigonos cut off from the central Aegean - retaining Andros carried no implications for control of the Kyklades - Ptolemaios had recovered motivation to renew his interest in the islands.

This interest did not last, however. Euergetes' defeat at the battle of Andros may have played a role in his retreat, but it need not be assigned a preponderant influence. Euergetes seems to have had little enough interest in the Kyklades, and the Third Syrian War soon focused his attention on Asia and the East, where he won striking victories.

D. The Kyklades after the Battle of Andros (246/5-200 B.C.)

The fate of the Kyklades during years between the battle of Andros, which occurred in 246 or 245 B.C.,56 and the Second Makedonian War has been cloaked in obscurity, thanks largely to the very poor state of the evidence. However, traces of influence of various outside powers on individual islands have led some scholars to argue for a general control of or hegemony over the archipelago by a single power. The main candidates have been the Ptolemies, the Antigonids, and the Rhodians. In the following section I review the evidence that has been adduced for these views and argue that it does not support hegemony by any single outside power over all the islands or for any extended period of time. In the second section I propose instead that we should regard the Kyklades as relatively independent for the years 246-200 B.C., during which they enjoyed a rare respite from foreign domination which permitted them to concentrate on their local economy, and introduced a spate of prosperity that, for once, did not go to feed the exchequers of the great Aegean powers.57

Urban, Wachstum und Krise des achaischen Bundes. Quellenstudien zur Entwicklung des Bundes von 280 bis 222 v. Chr., Historia Einzelschrift 35 (Wiesbaden 1979) 31-32. On

Aratos, see still F. W. Walbank, Aratos of Sicyon (Cambridge 1933) 36-40.

55 Plut., Aratos 12. Cf. Walbank in Hammond-Walbank 301-302, Will 12 321.

56 A consensus seems to be forming around Buraselis' date for this vexed battle (cf. Buraselis

144-145); see now Walbank in Hammond-Walbank 587-595 (who prefers 245 B.C. because

"Antigonos will hardly have ventured out into the Aegean with a war-fleet before his recovery

of Corinth" [595]); R. Malcolm Emington, A History of Macedonia, tr. Catherine Errington,

Hellenistic Culture and Society 5 (Berkeley 1990) 248; N. G. L. Hammond, The Macedonian

State. Origins, Institutions, and History (Oxford 1989) 313; Waldemar Heckel, Phoenix 40

(1986) 461; F. W. Walbank, JHS 107 (1986) 243, by implication; P. M. Fraser, CR 34 (1984)

260-261. Shadow of doubt in A. Mastrocinque, Gnomon 66 (1984) 515.

57 I argue this view in detail in Regionalism and Change in the Economy of Independent Delos, Hellenistic Culture and Society (Berkeley 1994). Cf. already Bikerman (as in n. 46) 380-383.

The Political History of the Kyklades 47

1. The Case for Foreign Hegemony

a. The Ptolemies

Several scholars have tried to identify a Ptolemaic hegemony in the Kyklades in the second half of the third century; Werner Huss has even argued that since nothing proves that the Makedonians or the Rhodians assumed control of the Island League after mid-century, it is reasonable to suppose that Ptolemaic control persi- sted even after 246 B.C.58 But the evidence cannot really even support a "Ptolemaic influence." 59 A loan taken out by the Delians to pay for a statue of "King Ptolemaios" in 246 B.C. must have commemorated either the recently deceased Philadelphos or the newly crowned Euergetes.60 The date assures that the statue was ordered before the battle of Andros, so that it has no implications for Ptolemaic control after 246 B.C.

A Delian inscription honors Sosibios son of Dioskourides of Alexandria. He is generally identified with the Sosibios known to have served Ptolemaios IV; a passage in Polybios (15,34,3-4) may show him working for Euergetes. Both Durrbach and Roussel insist that the inscription cannot go later than about 230 B.C.; the range is approximately 250-230 B.C. If Gustave Glotz's happy suggestion - that Sosibios was on Delos to found the third Ptolemaieia - is right, then the date would be exactly 246 B.C.61 A new Ptolemaic festival, the Theuergesia, was founded on Delos in 224-209 B.C.62 As I have remarked, the foundation of such festivals does not necessarily imply hegemony; this one, like so many others, attests rather to the attraction of Delos as a pan-Hellenic sanctuary. Finally, a statue base for Euergetes comes from Astypalaia (IG XII 3.204), but cannot be closely dated.

None of this skimpy material gives any ground for positing even localized Ptolemaic control after 246 B.C.63

58 Huss 218; on the views of K. J. Beloch, Griechische Geschichte (Strassburg 1904) Im 2.281- 283, cf. Holleaux, Etudes III 69-73. Huss insists as a principle on seeing all the Antigonoi of the various decrees to be discussed below as Gonatas (215 n. 288); Etienne, Tinos 1 97-98 rightly emphasizes the importance of letter-forms, which Huss arbitrarily ignores (cf. 97 n. 56).

59 Buraselis 175 with n. 214. 60 IDelos 290.129-131. Durrbach, IDelos comm. p. 15, writes "le roi ... est sans aucun doute

Evergete." IG XI 4.1073 may be the statue base. 61 IG XI 4.649 = Choix 44. Cf. Roussel, IG XI 4 comm. p. 27, Durrbach, Choix pp. 53-54,

Holleaux, Atudes m 47-54. Glotz (as in n. 44) 316-317 n. 7. 62 Bruneau, CDH 525-528. 63 Cf. already Holleaux, ttudes III 69-72.

48 GARY REGER

b. The Antigonids

Some scholars have seen a Makedonian hegemony after the expulsion of the Ptolemies - usually as a consequence of the battle of Kos or the battle of Andros or of both - whether continuous from Gonatas through Demetrios II to Antigonos Doson (with a loss of control during the early years of the regency of young Philip V), or broken and partial.64 In this section I will argue that the evidence for Antigonid activity in the Aegean after 245 B.C. can be found in four places: a) a group of islands near the Saronic gulf with fell under Antigonid influence under Gonatas; b) Syros, which probably represented an extension of Makedonian power east after the battle of Andros, intended to keep safe the normal sea route to Delos; c) Delos itself, always a recipient of Antigonid religious attention; and d) Minoa of Amorgos, which came under Antigonid control probably in the reign of Demetrios II or Doson.65

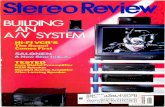

i. Islands near the Saronic Gulf (see Map)

In the first place, it is worth stressing that the Makedonian victory at Andros did not automatically deliver the Kyklades into Gonatas' possession.66 This view rests on a fundamental misunderstanding of the strategic role of the island. Though classed among the Kyklades, Andros is not "an excellent watchpost over the islands for the ruler of the Kyklades" 67 but rather a choke-point for movement in and out of the northern Saronic Gulf, that is, to and from the Peiraieus.68 Thus any claim for Makedonian suzereignty over the Kyklades after 245 B.C. cannot rest simply on Gonatas' success at Andros.

In fact, Antigonos' interests in Andros predated his defeat of a Ptolemaic fleet in its waters. In 250 B.C., when Aratos of Sikyon was trying to strike an agreement with the Ptolemies, he made a secret journey to Egypt. According to Plutarch, he put to sea from Methana above Malea, but Trp6& 8t p4-ya TuvEcita Ka'L TroXXAv OdXaacrav EK

1TEXdyOUS KaTLOUQaV V86VTOS TOV KV3EpVI1TOU, TrapaoEp6iEvog [LXLS7 114aTo t dti58L

64 Holleaux, btudes III 55-73; Delamarre 301-325; W. W. Tarn, Antigonos Gonatas (Oxford 1913) 469-472.

65 For the Koan inscriptions mentioning an Antigonos, most likely Doson, see Susan Sherwin-

White, Ancient Cos. An Historical Study from the Dorian Settlement to the Imperial Period,

Hypomnemata 51 (Gottingen 1978) 108-109, 114-118.

66 For a clear but by no means exceptional expression of this position, see Walbank, Aratos (as

in n. 54) 178, who calls the battle of Andros "the naval victory which recovered for Macedon

the thalassocracy of the Aegean." His views seem not to have changed; cf. Walbank in

Hammond-Walbank 307: "Antigonos' victory at Andros was a brilliant sequel to the recovery

of Corinth." Cf. also Delamarre 322-325. 67 Buraselis 93-94 n. 229 at 94: "fur den jeweiligen hellenistischen Herrscher der Kykladen ein

gunstiger Wachtposten in dieser Inselwelt."

68 For further discussion, see Reger, "Date" (as in n. 26); Delamarre 320.

The Political History of the Kyklades 49

0 25 50

EUBOIA km

Karysto

* Athens

AND RO S

W~~~~~~~~oe K D EOS

p p Koren~ulis TE <T NOS

> |>YKarthaia ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~MYKONOS

SYROS F RHENEI 5D

KYTHNO 4> DELOS

SERIPHOS Q

c p e dAXOS

SIP 'lNOS 006 #

After Defensive Mapping Agency Map ONC G-3 M

MELOS lKN

PHOLEGANDR0~

50 GARY REGER

(mss.; 'YCSpLas or' T8pElas: Bergk:: 'A<v>8p(as-: Palmerius) oto-rg cKpaTELTO 'ydp v Are 'Avy6voV Kal K uXaKv EIXEv. Aratus escaped the Makedonian commander by fleeing by ship to Euboia.69 W. H. Porter, who reviewed most of the proposals to fix the crux, preferred 'A<v>8pLas! on geographical and palaeographical grounds. Subsequent commentators seem to have followed him unanimously.70 Makedonian interest in Andros demands an entirely different explanation, which becomes clear only with a proper understanding of the island's role: Andros served as a convenient staging-ground for forces aiming at the conquest of Athens.

Examples of this role are numerous. In 308 B.C. a Ptolemaic force took Andros and expelled a Makedonian garrison; the Egyptian troops were directed at Athens and the Peloponnesos. In 287 B.C. the Ptolemaic forces that liberated Athens from Demetrios Poliorketes operated again from a base on Andros.71 More generally, the Khremonidean War must have made painfully clear to Gonatas the vulnerability of Athens to hostile forces ensconsed on the islands that straddle the mouth of the Saronic gulf (see Map). Philadelphos' general Patroklos stationed troops on Keos, where the name of the port of Koresia was changed to Arsinoe; Patroklos himself may have used loulis as his headquarters.72 A small island off Sounion used by Patroklos as a base was named for him. The nine "Pelops' islands" near Methana were probably named after a Makedonian active at the Egyptian court during the

69 Plut., Arat. 12.2-3. 70 W. H. Porter, Plutarch's Life of Aratus (Dublin-Cork 1937) xlii-xliii for the geographical

argument ("Hydria ... was of no account in antiquity ... why should Antigonos have kept a

garrison there?" and "a story to the effect that Aratus at Hydria had found a ship at a moment's notice in stormy weather to take him to Euboea ... does not wear the mask of truth" ), and 56 for the palaeographical (and philological) argument (that omission of letters is common in the mss. and that v tends to drop out after a; for 'Av8plas as "the country parts of the island as opposed to the town of Andros" Porter cites Xenoph., Hell. 1,4,22: 'AXKcLLd8rnS & T6 aTpdTEt4Ia U rE.t1TEP(PaUE nW 'Av8ptas X(LpaS' els FaipLov; already in Sauciuc [as in n. 151 2 n. 1). Cf. A. J. Koster, Plutarchi Vita Arati (Leiden 1937) Ixii n. 3, who adds nothing substantive to Porter's arguments except that if Aratos had landed at Hydria, Kenkhreai would have been a likelier refuge; Urban, Wachstum (as in n. 54) 27 n. 115; Huss 220-221 with 221 n. 312; Buraselis 173-174 n. 208; Walbank in Hammond-Walbank 301 n. 5 writes "TMe alternative 'Hydria' is impossible." Christian Habicht's recent suggestion ("Athens and the Ptolemies," Classical Antiquity 1 [1992] 88-90) that IG I2 1024.10-1 1, ELs! 'H8p4 [av], alludes to a Ptolemaic naval base there, adds an independent argument in favor of the emendation.

Holleaux, ttudes m 65 n. 1 suggests that the willingness of the Makedonian soldiers captured on Andros in 199 B.C. (Livy 31.15.8, 43.4-7) to remain implies that they had been stationed there much longer than from 201, when Philip V swept across the Aegean. Holleaux points to this passage as evidence that Andros might have been Makedonian since before 250 B.C.

71 Diod. 20.37. Shear, Kallias (as in n. 20) 2, line 20. 72 Robert, "Ddcret" (as in n. 22) 132-176; John F. Cherry and Jack L. Davis, "The Ptolemaic

Base at Koressos on Keos," BSA 86 (1991) 9-28.

The Political History of the Kyklades 51

war who also served as commander of the Ptolemaic forces at Samos. Methana itself, also renamed Arsinoe, was of course an important Ptolemaic base. There was probably also a Ptolemaic naval station or garrison on Hydria, also off Methana.73 A new insription from Eretria on Euboia refers to a cult of Arsinoe Philadelphos; this cult has reasonably been associated with Ptolemaic activity during the Khremoni- dean War. Ptolemaic forces were able to establish camps on the Attic mainland and interfere with the harvests in the countryside.74 If the Ptolemies retained these bases (with the exception of course of their footholds in Attike) until c. 145 B.C.,75 Gonatas and his successors would have had good reason to maintain their own garrison on Andros. But even if the Ptolemies withdrew from some of these bases (it seems likely to me that their defeat in the Khremonidean War would have forced them to abandon Patroklos' island; Euboia certainly did not remain in their hands; and we hear no more of Ptolemies on Keos, though Koresia did retain its new name down to the end of the third century), their continuing presence at Methana at the very least would have compelled Gonatas to try to establish countervailing garri- sons around the month of the Saronic Gulf. This interest accounts for the Antigonid garrison on Andros. But likewise, with one exception, the other Kykiades for which we have reliable testimony of an Antigonid presence after c. 245 B.C. all also cluster around the mouth of the Saronic gulf.

Keos. IG XI 5.570,76 which comes from the polis of Poiessa, regulates pay- ment of taxes (x6pos) on property. Two kings are mentioned: (3aQLXE [V]S A,rf[4TpLosi at A8 and [3aGLXEiVi] 'A[VT1tyovos at B4-9, a passage which has been plausibly restored as the beginning of a royal letter. The flow of the document indicates that Demetrios is restoring or confirming something granted or settled by Antigonos. The stone has been lost and the letter forms are not known.77 In principle two

73 Paus. 1. .1 with J. Schmidt, RE 18.2 (1949) s. v. Patroklu Nesos 2289-2290. Paus. 2.34.3 with W. Peremans and E. van 't Dack, Historia 8 (1959) 170 and R. Herbst, RE 19.1 (1937) s.v. Pelopsinselchen 392-393; on Pelops, Chr. Habicht, Ath.Mitt. 72 (1957) 210 and Ath.Mitt. 75 (1960) 113, Pros. Ptol. no. 14618. On Methana, cf. Habicht, "Athen" (as in n. 70) 90 n. 133 and 88-90 on Hydria, with F. Bolke, RE Suppi. 3 (1918) s.v. Hydrea 1159-1161.

74 Karl Reber, Antike Kunst 33 (1990) 113-114; Denis Knoepfler, La vie de Menedeme d'Ertrie de Diogene Laerce. Une contribution d 1'histoire et a' la critique du texte des Vies des philosophes, Schweizerische BeitrAge zur Altertumswissenschaft 21 (Basel 1991) 203 n. 90, cf. 175 n. 15. James R. McCredie, Fortified Military Camps in Attica, Hesperia Suppl. 11 (Princeton 1966) passim; Heinen 152-167. For a new fragment of the Epikhares decree, see Praktika 1985 (1990) 9, 13-14.

75 Habicht, "Athens" (as in n. 70) 90. 76 With Add. et corr., p. 331 and XII Suppi., p. 114, from Sterling Dow and Charles Farwell

Edson, Jr., "Chryseis," Harv.Stud.Cl.Phil. 48 (1937) 134 n. 1; P. Graindor, "Inscriptions des Cyclades," Muse'e Beige 11(1907)97-113 at 104-106, and "Kykiadika," Musee Beige 25 (1921) 121-122. Cf. Walbank in Hammond-Walbank 294; Cherry and Davis (as in n. 72) 15- 16.

77 Graindor, "Inscriptions" (as in n. 76) 104; Buraselis 87 n. 201.

52 GARY REGER

identifications are possible. Antigonos and Demetrios could be Monophthalmos and Poliorketes, as F. Hiller von Gaertringen and J. Delamarre believed, or the Demetrios could be Demetrios II and the Antigonos either Gonatas or Doson. P. Graindor once thought that the appearance in the text of TEi and f3OVXEL excluded a date as early as before 286 B.C., but in fact EL for TI occurs in Kykladic inscriptions by the end of the fourth century, no doubt following a trend already well established in Athens by the last quarter of the fourth century. Graindor later came to accept the identification with Monophthalmos and Poliorketes.78 The decree makes good historical sense in either case. If it belongs under Antigonos Monophthalmos and Demetrios Poliorketes, the references to taxes may echo the evidence of the Nikouria decree (IG XII 7.506 = SIC 390), in which the islanders praise Ptolemai- os I for having restored their ancestral constitutions and either abolished or reduced the contributions Demetrios had made them pay.79 On the other hand, if the inscription belongs under Gonatas and Demetrios II (or Demetrios II and Doson), then it will amplify the pattern of Antigonid interests in the islands that guard the entrance to the Saronic Gulf.80

Another inscription, IG XII 5.571, III, also from Poiessa, honors a lauuavcasg

AV8POV1KOV MaKE86v. The lettering includes broken-bar alphas, slightly splayed mus and sigmas, and pis with short right hastae but no overhang by the horizontal cross-bar on either side. These forms certainly date the inscription to the last quarter of the third century.81 Unfortunately the honorand Pausanias son of Andronikos is not known elsewhere; but the awards of citizenship and proxenia and the fact that Pausanias "continues to be a good man for the city of the Poiessians," dev,p dryaO6s U)V 8LaTE [X]Ec TTEpt TrV rT6oXLV -rnv ToILtCWv (11. 15-16), assure that his beneficia were likely to have been political and that he was exercising them not in Poiessa but in Makedonia.

Kimolos and Geraistos on Euboia. For Kimolos we have an inscription from Geraistos on Euboia honoring a Kimolian dikast.82 The editors put the text in the third century, which, they say, "obviously rules out the possibility that 'King

78 Hiller von Gaetringen, IG XII 5, comm., p. 150; J. Delamarre, Rev.Phil. 28 (1904) 14 n. 6. Graindor, "Inscriptions" (as in n. 76) 104. Elisabeth Kniti, Die Sprache der ionischen Kykladen nach den inschriftlichen Quellen (Munich 1938) 21; for Athens, Leslie Threatte, The Grammar of Attic Inscriptions, I. Phonology (Berlin-New York 1980) 378; A. S. Henry,

"Epigraphica," CQ 14 (1964) 240-241, specifically for TEt 3vXEt and mL POVXft; Euard Schwyzer, Griechische Grammatik (Munich 1938)1.201-202. Graindor, "Kykladika" (as in n. 76) 121-122.

79 Lines 13-16; on the ambiguity of the word Kot4taasC, see Merker (as in n. 30) 151 n. 46.

80 The solution rejected by Graindor but toyed with by Cherry and Davis (as in n. 72) 16, of

correcting Demetrios to 'A(v)[T(yovos0, is not acceptable. 81 Cf. already Graindor, "Kykladika" (as in n. 76) 120. 82 Thomas W. Jacobsen and Peter M. Smith, "Two Kimolian Dikast Decrees from Geraistos in

Euboia," Hesperia 37 (1968) 184-199 with Plate 57.

The Political History of the Kyklades 53

Antig[onos]' in line 21 refers to Antigonos I." The choice is either Gonatas or Doson.83 In my view the letter forms cannot go as late as Doson. Decisive are the alphas, which have "either perfectly horizontal ... or sloping" crossbars.84 The rest of the lettering fits perfectly comfortably in the mid-third century, or even slightly earlier.

This text then contributes to the evidence for Gonatas' role on Euboia and shows his influence on Kimolos. Even though the inscription does not explicitly say so, Geraistos must have approached Antigonos, asking for him to resolve the long- standing lawsuits plaguing the city, TdLSg 8Kat eK 1TQaXaLLv (line 22). Antigonos will then have selected Kimolos to provide a dikast to judge these suits KclTd T-rV

t1TLUTOXV TOO (3aLXLwsI'AvrLy[6vov] (line 21). This procedure is familiar from many examples.85

Gonatas' interests on southern Euboia and Kimolos are of course easy to divine: like Andros, these islands straddle the entrance to the Saronic Gulf; Kimo- los, sitting at the bottom of the so-called "westem string" of islands, overlooks the sea-passage at the southernmost end. The loss of Euboia (among other possessions) to Alexandros son of Krateros in 253 B.C. crippled Gonatas and confined him for several years to the mainland. Gonatas' authority on Kimolos thus fits well with his long-standing interests in the islands facing the Saronic gulf.

Kythnos. Maurice Holleaux86 thought Doson might have controlled Kythnos on the basis of Livy 31.15.8. Livy's list of islands with Makedonian garrisons at the start of the Second Makedonian War includes one (Paros) certainly taken the year before (Livy 31.31.4) and one (Andros) which had probably been Makedonian since before 250 B.C.87 There is no way to know into which category Kythnos fell. However, a Makedonian garrison on Kythnos since Doson's or even Gonatas' day would have made perfect strategic sense to a dynasty anxious to guard the entrance to the Saronic gulf, since Kythnos watches from the south the strait that Keos guards from the north.

ii. Syros

Delos has preserved for us a fine decree of the Syrians for Eumedes son of Philodemos of Klazomenai, who was sent by king Antigonos as anm RKpLT - TrV

cruivaXatwv for Syros.88 J. Delamarre dated this decree to the reign of Antigonos Doson, but P. Roussel and F. Durrbach both preferred 250-240 B.C. on the basis of

83 Jacobsen and Smith (as in n. 82) 198. 84 Jacobsen and Smith (as in n. 82) 186. 85 Cf. the Naxian decree as restored by Holleaux, ptudes Im 27-37 at 32, lines 1-5. 86 ttudes III 65. 87 Cf. above, n. 70. 88 IG XI 4.1052, lines 22-23, 25 = Choix 45.

54 GARY REGER

the lettering; they are clearly right.89 This decree provides positive evidence, then, of real Makedonian influence on a central Kykladic island. It is worth emphasizing, however, that the date coincidences well with the defeat off the Ptolemaic fleet at Andros in 246 or 245 B.C., and that the Kyklades show a pattern of internal disruption correlated with changes in suzereignty.9? It would not be surprising, then, if some Syrians had taken advantage of the change to appeal to their new suzereign. In the 280s the Naxians had appealed about exactly the same kind of problems to their new Ptolemaic overlords, and had received Koan dikasts.91 This decree therefore does not necessarily prove either continuing Makedonian hegemo- ny, or even predominance, in the decades after the battle of Andros, nor does it show Makedonian control over all the islands.

iii. Delos

Delos clearly had important relations with the Antigonids from Gonatas on. Antigonos built a portico and set up a dedication to his ancestors; a statue of his wife Philo, daughter of Seleukos I and Stratonike, was erected on the island; and the king made a number of precious offerings to the sanctuary and established several festivals.92 His successor Demetrios II sent grain purchasers to the island, and the Delians honored a court official named Autokles from KhaLkis and a Makedonian Admetos from Thessalonike, whom Durrbach associated with the court.93 Demet- rios also founded a Demetrieia at his accession in 238 B.C. in the tradition of his

89 Delamarre 310; P. Roussel at IG XI 4, p. 86, f. Tabula III; Durrbach, Choix p. 56. The text has only straight- or bowed-barred alphas. The lettering closely resembles that of IG XI 2.287, which dates exactly to 250 B.C.

90 A whole series of decrees shows sometimes quite serious internal disputes at the advent of Ptolemaic control at Karthaia on Keos, at Naxos, at los, and perhaps at Amorgos; at Thera when the Ptolemaic garrison was introduced at the beginning of the Khremonidean war; and later at Karthaia on Keos when control passed from Philip V to the Rhodians: IG XII 5.1065, cf. 541 with BCH 78 (1954) 336-338, no. 13; Holleaux, ttudes III 27-37; IG XHI 5.7 with p. 301 and IG XII Suppl., p. 96; IG XII 7.14 with p. 127 and 15 with XIl Suppl., p. 142; IG XII 3 Suppl. 1390, cf. 1391 + XII Suppl., p. 87, and XII 3 Suppl. 1296 + XII Suppl., p. 85; BCH 78 (1954), 338-344, no. 14.

91 Holleaux, ttudes m 27-37. 92 IG XI 4.1095, 1096, 1098 = Choix 35-37; for offerings see Bruneau, CDHI 550-551, 558-564

for the festivals; 552-553 on the portico. On the controversial Neorion, see Bruneau, CDH 554-557 and most recently, Trdheux (as in n. 28). The festivals have been the subject of endless discussion, usually attached to the date(s) of the battles of Kos or Andros and the reality (or illusion) of an Antigonid hegemony over the islands after c. 250 B.C.; it will suffice to refer to Buraselis 141-144, 146-147; Bruneau, CDH 518-531, 557-564, esp. 579-583; Jacob Seibert, review of W. Gunther, Das Orakel von Didyma in hellenistischer Zeit. Eine Interpretation von Stein-Urkunden, Istanbuler Mitteilungen, Beiheft 4 (Tubingen 1971), GGA 226 (1974) 186-212, for discussion and bibliographic references.

93 IG XI 4.666,679-680,664-665, 1053 (cf. 1076) = Choir 48,47,49.

The Political History of the Kyklades 55

predecessors.94 Antigonos Doson celebrated his famous victory over Kleomenes of Sparta with a dedication at Delos, from which Maurice Holleaux has argued for a persisting Makedonian hegemony over the island in the second half of the third century.95

Antigonid interest in Delos is clear; but the degree to which it is right to speak of "hegemony" or "control" or even "predominance" is much less so. This is particularly the case when court officials are honored. Two Delian decrees of the second century which honor a court official of Eumenes II (IG XI 4.765-766) do not prove any kind of Pergamene control over Delos.96 Likewise Demetrios II and Doson's connections with the island need prove nothing more than traditional family interest - no Antigonid since Monophthalmos had failed to make dedica- tions or establish festivals on the island - and predictable piety toward a pan- Hellemc sanctuary. While it is reasonable to suppose, as Holleaux argues,97 that Doson would probably not have commemorated his victory at Sellasia on a Delos under Ptolemaic control, the Sellasia monument seems to me to find its parallel in the inscriptions erected by Attalos I of Pergamon and his general Epigenes to commemorate the defeat of Antiokhos Hierax and his Gauls in 228 B.C. These dedications cannot imply a Pergamene hegemony.98

iv. Minoa on Amorgos

Several inscriptions from Amorgos mention a king Antigonos without further specification. Nothing in the texts of the decrees can help determine whether he was Gonatas or Doson. Two of these documents, which are both from Minoa on Amorgos (IG XII 7.221 and 222),99 carry telling lettering: a transitional mixture of bowed- and broken-barred alphas, pis with a short right vertical and an overhanging horizontal on the right but not the left, slightly splayed sigmas, and mus with

94 IDelos 313 i 23, 320 B 42, 58; cf. Bruneau, CDH 563-564. 95 IG XI 4.1097 = Choix 51. Holleaux, btudes HI 55-73. On the date of Sellasia see P. Perlnan,

"TMe Calendrical Position of the Nemean Games," Athenaeum 67 (1989) 80 with the literature cited at n. 95 there; for the "constitutional" implications of the language of the dedication, cf. J. Treheux, "Koinon," REA 89 (1987) 41-43. The dedications recorded in IDelos 442 B 10, 11, 20, 42, 48, and 161, which J. Delamarre attributed to Doson (DelamaTre 322), all belong in fact to Monophthalmos or Gonatas; cf. Durrbach's comm. ad loc., p. 163.

96 The honorand, Demetrios the son of Apollonios, was also honored at Larissa in c. 171 B.C. and at Ephesos; cf. SEG 31.574 (IG IX 2.512), SEG 26.1238. I am grateful to Christian Habicht for these references.

97 Holleaux, ttudes m 62-64. 98 IG XI 4.1109 (= Choix 53) and 1 10, which is very fragmentary but clearly parallel to l.v.Perg.

29. Cf. R. E. Allen, The Attalid Kingdom. A Constitutional History (Oxford 1983) 195-199, who however does not cite the Delian material.

99 I was unable to find a third inscription, IG XII 7.223, during my visit to Amorgos in 1990. I want to take this opportunity to thank Manolis Despotidis for his help and kindness during my stay at Khora on Amorgos.

56 GARY REGER

practically vertical verticals. Good parallels for the lettering can be found in the Kretan treaties of alliance with Antigonos Doson, ICret III Hierapytna lA and II Eleutherai 20. They mix bowed- and broken-bar alphas, splayed sigmas and mus (straight sigmas at Eleutherai), and pis with short right hastae and projecting horizontals. Both date to 224-222 B.C.100 These texts and the dates of the earliest introduction of broken-barred alphas argued above make it very unlikely in my view that these two Minoan inscriptions could go as early as 240 B.C. Such a date would presuppose the introduction of this new letter form at Minoa on Amorgos - certainly an out-of-the-way spot, however pleasant to visit - twenty years earlier than at Delos or Athens. This seems unlikely. It is therefore best to assign these texts to Doson, not Gonatas. Io1

What do these texts say about Doson's relations with Minoa? The first, IG XII 7.221, honors one ALOKXE[&La! arTTETaXl#Evos 1bT6 TOO P3aKLXEw' 'AVTrO6VOU who brought letters from the king and resolved T,-4 KaTEUTW"S! TapaA4 (lines 6-7, 10). Such royal interventions in the affairs of Kykladic cities are well known, and indeed imply some genuine interest in and control over the cities in question; the letans had appealed in similiar language to Ptolemaios 1.102 It is tempting to associate the second inscription with the same incident. This reports the presence of representa- tives of king Antigonos at Minoa. These men have been thought to have been Naxians on the basis of Delamarre's reading ot TrapayLv6IiEvoL NO[LoL 1rapa' TOO

r3a]utXwSW 'AVTLrYO6VOu (IG XII 7.222.2-3); Antigonid control of Naxos has been inferred. But these "Naxians" are a phantom. A pi, not a nu, follows TrapayLvO6LEVoL

(the left vertical and the horizontal are visible), the xi is only a vertical line, and a faint but definite alpha follows. The text should be read as ol TcapayLvO6LEvoL lTapct

[TOO 3a]aLVW!9 'Av-rLy6vov. The Naxians disappear. A third decree, which records proxenia for one Sosistratos who may have been

an Antigonid court official (IG XII 7.223.1-2), seems again to fit best under Doson. The eponymous official at Minoa under whom the decree was passed was one Kharinos whose son appears in a Tenian inscription of the second century;103 the father should then probably be active in the last third of the third century.

These documents clearly illustrate Doson's interests in and influence over Minoa on Amorgos. There are two aspects to this matter. We may ask about the nature of Doson's interest; if it is simply that he exercised a hegemony over the whole Aegean, the answer is equally simple: he was just acting as hegemon. But if, as I am arguing, the evidence does not support a general Makedonian suzereignty over the Kyklades in these years, then it is necessary to seek a specific context for Doson's activities. This we will do presently.

100 Cf. below, n. 112. 101 Cf. already J. Delamarre in IG XII 7, p. 52. 102 IG XII 5.7.2: [1TEPI TrSf Kand T,v] lr6XLv 'yEVOTv1Sg TapaxffIs]. For other examples, cf. nn.

23 and 90 above. 103 IG XII 5.821; cf. LGPN I, Xaptvos, no. I and 2.

The Political History of the Kyklades 57

But first it is worthwhile to ask another question. If Doson was not the general hegemon of the Aegean, exercising his influence on Minoa "by right," then what Minoan interests did Doson's activities answer? Minoa was suffering from TapaXh.

This word expresses serious confusion or chaos, as among the Rhodian leadership at the arrival of bad news from Rome about Lykia in 178 B.C. Diodoros uses it to denote the confusion of an army about to be routed, and of the Syracusans at the approach of Carthaginian troops in 310 B.C. On Syros a pirate attack of c. 100 B.C. resulted in TapaX)M I,ELCoVosg -YWOtvi McTa -r?v TrT6XLV.104 The Minoans clearly