Permeable Boundaries: Towards a Critical Collaborative Performance Pedagogy

Transcript of Permeable Boundaries: Towards a Critical Collaborative Performance Pedagogy

Permeable Boundaries:

Towards A Critical Collaborative Performance Pedagogy

Nisha Sajnani

A Thesis in the Special Individualized Program

Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of

Doctorate in Philosophy

Concordia University

Montreal, Quebec, Canada

January 2010

©Nisha Sajnani, 2010

iii

ABSTRACT

Permeable Boundaries: Towards a Critical Collaborative Performance Pedagogy

Nisha Sajnani, Ph.D. Concordia University, 2010 This thesis represents an interdisciplinary inquiry into the boundary between the

listener and the teller in applied theatre performances that purport to effect progressive

change in the attitudes, beliefs or behaviors of those who bear witness: the audience.

Without attending to this boundary, the transformative potential of the performance

project risks impotency and may well result in an unintended affirmation of harmful

divisions of power in society. Current approaches to empowerment that fail to move

beyond hegemonic social relations, that do not entail a redistribution of resources and

decision making authority, result in asymmetrical change and reinforce the boundaries

that sustain poverty. A rationale for audience engagement strategies that can effectively

disrupt this center/margin binary is presented through a retrospective case study of three

applied theatre projects. An argument is made for a critical, collaborative performance

pedagogy as a foundation for a relational praxis of social empowerment in applied

theatre. Essential components of this approach situate applied theatre as a form of

participatory action research involving collaborative processes between audience

members prior to, during, and after the performance event. Such an approach attempts to

disrupt the dynamics that produce poverty by galvanizing the collective analysis and

action of the audience within a larger community organizing strategy.

iv

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

There are many people who have supported me along this journey and I would like to acknowledge a few individuals in particular who have helped me contribute a verse to what is possibly the greatest conundrum of philosophy: how to connect what is with what ought to be. I am grateful to my mentor, Dr. David Read Johnson, for your faith and commitment to my development. Thank you for the readiness of your challenge, your contagious humor, enthusiasm, and your generosity. I would not have completed this task nor lain this foundation if it were not for you. I am thankful to Dr. Alice Forrester. Thank you for restoring my will, unbinding my motivations, and reminding me of the Legacy that has been and continues to unfold. I am thankful to my committee. Dr. Margie Mendell, for your willingness to oversee this journey, for your steadfastness, and commitment to excellence. Thank you for introducing me to such innovative thinkers and for providing me with Opportunity. I also thank Dr. Stephen Snow for your creative spirit and for your guidance and encouragement in this process. Thank you Dr. Edward Little. Our brief conversation after our performance on the politics of water in Bangalore provided the inspiration for this work and I continue to enjoy our work together. I am deeply and happily indebted to Cindy Coady, Geeta Nadkarni, and Kris Tonski for your love and friendship, for your laughter, available ears, rich insights, and unwavering support. Thank you for taking such good care of me. Thank you to Denise Nadeau, Warren Linds, Norman Fedder, Cecilia Dintino, Amy Thomas, Pardis Zarnegar, Mahshad Aryafar, Danusia Lapinski, Paul Gareau, Lucy Lu, Allan Rosales, Alan Wong, Serge Carrier, Navah Steiner, Mira Rozenberg, Elizabeth Hunt, Gerardo Sierra, Dipti Gupta, Rahul Varma, Tana Paddock, Joni Ward, and Rebecca Giagnacova for our many compelling conversations over these years and for such willing playfulness. You continue to inspire me. Thank you to the students and teachers of the Centre for Social Action at Christ Church College and to Dr. George Kutty of the Free Tree University in Bangalore for the ways in which you have modeled a path of artful, social service and holistic scholarship. Finally, I thank my mother, Rakhee Sajnani, and my sisters Sonia and Reena for their love, support, and prayer. We have had many great adventures during the completion of this work and there are many more to come. It is just the beginning.

v

PROLOGUE: Two Stories

In December of 2006, in a small village outside Bangalore, a group of young

students from the Centre for Social Action in Christ Church College (Bangalore) and law

and theatre students from Concordia University (Montreal) along with myself and a few

other faculty members participated in a theatre-based human rights project called Rights

Here! (phase 1). Over the course of three weeks, we created and performed a montage of

songs and scenes relating the politics of water to urban and rural audiences. In one village

in particular, residents had not been able to access water from the local pump for three

days. The water table had dropped 233% with the invasive and aggressive drilling tactics

of multi-national corporations resulting in villagers having to walk ten miles to collect

water; water that was only available to be drawn for four hours each day. The reason for

this limited accessibility was due to the fact that the electric pumps needed to gather

water were also privately owned and only made available for brief periods by their

owners. After the performance, a young Bangalorian student from our troupe took on the

role of the mediator (facilitator) between the audience and the action and asked the

audience about their thoughts relating to the lack of this essential common good. A

middle-aged man approached and said, quite simply, ‘Did you bring water’? He

explained that his children had not had water for three days and when he heard the bells

and calls signaling our performance in an open area of the village, he thought we might

have been bringing water. Our ‘emcee’ explained that we had not brought water but that

we were there to draw attention to the lack of water faced by the urban and the rural poor.

I remember feeling that this man already knew that reality all too well. I also remember

the complicity we felt as we returned to our bus where we had stored bottles of water for

vi

our journey; bottles of water produced by the same multinational corporations

responsible for the thirst these villagers faced. The urgent nature of his question prompted

a dialogue amongst our group about the role of the artist in community development,

about the necessity of working in alliance with those already engaged in practical local

development and with those who create the inequities present, and about the need to

evolve methods of engaging audiences, both those absent and present, in constructive

dialogue. This experience also prompted me to think about the gathering created by our

spectacle in that village. There we were surrounded by mothers, fathers, children, and

elders who, while they all face the same difficult reality, may not have had an opportunity

to gather together to give their collective attention to the issues that affected them most.

The collective attention of the audience appeared to be, in that moment, a political act

that appeared to sever the habitual divide between public and private suffering. Granted,

this analysis provides little comfort when people are thirsty.

***

Another moment in another village outside Mysore on that same trip, our group

witnessed the work of a local, popular street theatre group perform a play about the

exploitation of child labor. Our group sat on the dusty ground amongst the local villagers

and the village elders under the cover of darkness half-lit in the intermittent shadows cast

by a single light bulb swaying precariously on thin wire that ran the length of a single

main meeting hall a few feet away. The scene depicted a family in poverty facing illness

and diminishing choices. The performing group sang in Kannada, the local language,

about children’s hands - young hands that would not know play, but that were calloused

and hard from having been put to work to pay for the family’s debts. After the play ended

vii

there was silence. In our group, we peered at one another appreciative, anxious, curious,

uncertain and then…someone…clapped. A man who appeared to be visibly in charge

noticed this. He seemed to gesture at the others to start clapping. A slowly escalating and

uneasy applause ensued.

After the gathering dispersed, we were led to the large porch in front of the dimly

lit hall where they had arranged daal (lentils), rotis (bread) and water (life) for us. We sat,

ate, and questioned the moment. One of the leaders of the performing troupe, a

tremendous musician and singer, explained that ordinarily the silence that followed the

play would have remained because the play was depicting the everyday realities these

villagers faced. The clapping broke this silence and, in an instant, created a spectacle

removed and distant from the familiarity of our lives. He explained, in gracious yet

unapologetic tones, that they would have normally continued a dialogue after the

performance but that, in large part due to our presence, they had not pursued this crucial

conversation about the lives of the children in that village. He continued to explain that,

on their last visit to this village, they had performed a play depicting the fact that the land

these villagers worked had been bought by external landowners leaving them to find a

means to travel to an urban center to work. This reality was further compromised by the

fact that there were no roads leading in and out of the village. The troupe had performed a

play about the connection between their isolation and their poverty. After that

performance, the dialogue that took place resulted in plan to barricade the nearest local

road until government officials took notice. Both the actors and the villagers had pursued

direct action together and created a human barricade for days. Their efforts were

rewarded with a wide, new dirt road. Through a form of peer-lending, the villagers were

viii

also able to purchase a bus that they proudly showed off to us that evening. In fact, our

bus traveled that same road to get to their village and we were the very first visitors they

had received since the road was created. So, in this context, theatre was a serious and

revolutionary endeavor and the actors were allied in the struggles faced by communities

beyond the scope of the performance or perhaps as part of an ongoing ‘play’ with power.

Again, this experience gave me pause. I can still hear the sound of our clapping in the

stillness of that night and wonder at its ability to pull us further away from the scene,

distancing ourselves from implications of such a terrible reality, reducing it instead to a

fictive illusion. I still wonder at what possibilities for action existed within such a

diversely located audience and at what responsibilities may have been pre-empted by our

presence. The image of the dirt road leading able-bodied workers out of the village to

work in the city, while heralded as progress, also revealed larger trends of a growing

divestment from one’s land, labour and capital. These experiences, along with the others I

have presented in this thesis cast into sharp relief the necessity of defining the ways in

which applied theatre can irrigate the boundaries that define centers and margins of

power to create the possibility of solidarity and justice in light of persistent social and

collective trauma.

ix

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Introduction ..………….…………………………………………...1

Chapter 2 Literature Review…………………………………….9

Chapter 3 Methodology…………………………………...........47

Chapter 4 It’s A Wonderful World…………………………….55

Chapter 5 Rights Here!………………………………................74

Chapter 6 Creating Safer Spaces….…………………................93

Chapter 7 Discussion……………………………………….....110

Chapter 8 Conclusion…………………………………............125

Endnotes ……………………………………………………..129

References …………………………………………..................131

Appendix ……………………………………………………..138

1

INTRODUCTION Her (story) remains irreducibly foreign to Him. The man can't hear it the way she means it. He sees her as victim, as unfortunate object of hazard. `her mind is confused,' he concludes. She views herself as the teller, the un-making subject... the moving force of the story. (Trinh T. Minh-Ha, 1989,p.149)

This is an investigation of the space between the listener and the teller in applied

theatre performances that purport to effect progressive change in the attitudes, beliefs or

behaviors of those who bear witness: the audience. Without attending to the boundary

between the listener and the teller, the transformative potential of the performance project

risks impotency and may well result in an unintended affirmation of the status-quo. This

thesis explores the opportunities for dialogue, coalition building, and solidarity amongst

witnesses to difficult stories, stories that emerge from dystopic, unsettled, displaced, and

often violent realities in the context of public performance. In this chapter, I will introduce a

rationale for the evolution of effective audience interaction practices and the necessity of a

critical, collaborative performance pedagogy (CCPP).

Efforts to effect change in society have been based on analyses of divisions of power

(Gramsci, 1971; Gujit & Shah, 1998). Individuals and communities have had differential

access to power depending on their membership in particular social groups at different

points in history creating centres and margins of power with those who have the most access

and opportunity to exercise power at the centre. For the purposes of this study, the issue of

whether an optimal society contains divisions of power or that these divisions are stratified

along the lines of social difference will be placed to the side. Further, the author adopts the

perspective that society is not neatly divided into homogenous nor fixed centres and

margins, but that these stratifications of power are produced, performed, multi-layered, and

context specific. Individual or social differences, and their corresponding social power, are

2

not constant nor immanent but produced through discursive practices and performed in

daily interactions. Rigid boundaries between those who have and those who do not have

power limit the degree to which those who occupy marginalized space in any given context

will be able to enjoy the full arc of their potential.

For example, those who are physically impaired in a society that privileges able-

bodied people will not enjoy access to the same opportunities as their able-bodied counter-

parts. They may be overtly, though variably, restricted from public and private spaces that

are not physically accessible to them and consequently further restricted from possible

economic, educational, and civic opportunities. In this example, the physical planning of

this imagined territory is a construction of a variably coordinated ‘centre’ that creates a

boundary which restricts the advancement of those who are overtly or subtly relegated to

the ‘margins’. This arrangement of power, centres and margins produced over time

coincident with the intersections of one’s socio-economic status, ethnicity, legal status,

ability, gender, age, and sexual orientation among other social locations, restricts the

mobility of members of marginalized groups from attaining the resources and opportunities

required to better their quality of life. Consequently, this structure also shapes and possibly

restricts the degree to which those who enjoy the benefits of the centre are willing to render

these boundaries more permeable by collaborating in efforts to create equity and justice

across lines of difference. Therefore, the permeability of the borders or boundaries within a

given society is of pivotal significance in the assessment, design and evaluation of projects

that seek to address inequity.

Efforts to increase permeability or mobility across boundaries tend to focus on the

actions or potential actions of those located in the margins of society, rather than the actions

or potential actions of those who enjoy the benefits of the centre (Shragge, 1997; Mendell,

3

2005). Transformative economic, pedagogical and research protocols such as those

espoused in community economic development or participatory action research place

emphasis on the importance of having those most affected by particular hardship(s) bring

about desired changes by building consensus about the nature of the problems they are

faced with and mobilizing their own resources towards desired outcomes. Within these

models, projects devised to improve the quality of life of individuals and communities

burdened with stigmatization, social and/or economic restrictions resulting from real or

perceived differences in socio-economic status, geographic location, legal status, race,

ability, sexuality, gender, ethnicity or other social categories, are often generated by and/or

for the communities in question. Efforts are centred upon the coordination of the group

affected to move towards their desired goals.

In the example of physically disabled persons who have been restricted from

exercising the full range of their potential, they may choose to address the barriers, such as a

lack of physically accessible spaces, by either organizing themselves to either build desired

spaces or encourage the governing body of their territory to entertain modifications to their

physical landscape. In either approach, change is envisioned as the potential outcome of a

marginalized group’s capacity to assert a unified challenge, a capacity potentially

compromised by an overly facile construction of ‘community’ and by a possible lack of

resources, in confidence, time, money or space for example, resulting from the structural

inequities identified.

Therefore, empowerment efforts have relied on an asymmetrical relationship

between the centre and the margins wherein those occupying marginalized space are tasked

with transforming themselves with minimum, if any, disturbance or risk to the centre. When

efforts to realign this relationship towards an increased permeability between centres and

4

margins, to share authority or redistribute resources, fall short of their mark, the blame is

often placed upon the ‘community’ for being uncoordinated in their attempts to achieve

change. In the example above, a group of people similarly affected by a lack of accessible

spaces in the city may be granted sponsorship in the form of seed funding to support their

efforts, a space to meet, and supplies to creatively assert their goals. They may have access

to training in leadership, empowerment, and methods of influencing media. However, this

support, while respective of their efforts, does not require the host or dominant society to

make any changes to their territory as a whole nor risk reducing their political, economic or

social power. In fact, such acts may increase their power when they are seen as benevolent

partners. In this way, the boundary or glass ceiling between margins and centres of power

remains preserved and any failure to thrive experienced by the ‘community’ is firmly

attributed to a deficiency on their part.

Applied theatre that purports to effect social change also follows this formulation.

Performances are produced by, with, and for marginalized, disenfranchised, or otherwise

dispossessed groups in an effort to gain power; to gain internal or external resources.

Attention is given to the realities of those seeking change with minimal attention or

adaptation required, if any, from the always already diverse audience beyond watching or

sponsoring these events. Projects undertaken by community groups who seek to increase

their quality of life are often sponsored by academic and cultural centres of power, federal

and/or private funding agencies. Individual theatre practitioners who are allied with a given

community’s goals may support the development of theatrical productions aimed at drawing

attention to their realities with the hopes of effecting change. Here, the margins are given

centre-stage while potential representatives of the centre, the audience, are seated in the

margins and asked to give their full attention to the realities lived by others. This is not to

5

say that all applied theatre projects are, intend to, or should be performed by members of

marginalized groups for members of the ‘centre’. Nor are performers and audiences neatly

divided into representatives of the margins and centres within a given society. However,

when untold stories are given an art form and a platform, audiences, as representatives of

society, remain largely unburdened.

Attempts to engage the audience have ranged from textual to dialogic and embodied

techniques designed to provoke reflection and action. Certainly, the experimental theatre

movement, the work of Brecht and Boal, and current community-engaged theatre practice

are of pivotal significance in considering the ways in which audiences have been forgotten

or engaged in the social project. However, while their strategies have been successful in

arousing a critical consciousness and the desire to act upon injustice, they have stopped

short of laying the groundwork for sustainable change outside the doors of the theatre. The

temporary reversal of centre and margin focuses on the transformation of the marginalized

group and the awareness and appreciation of the audience, but misses the relational nature

of sustained change. As a result, these projects may have limited impact and, ironically,

may risk further entrenching the disparity of power between the margins and the centres

they seek to disrupt by restricting the audience’s role to that of a concerned and appreciative

benefactor at most. Whether the stories of those living at the margins of society are staged

by those affected directly or actors who wish to draw attention to particular realities, the

audience is asked to bear witness; to watch, listen, think and, at times, act. However, their

capacity to respond is compromised by the distance they may feel from the realities staged,

the silence surrounding their complicity in the maintenance of these realities and the

structural dynamics that operate together to sustain oppression. Their will to act, to respond

6

differently in the face of injustice, is further compromised by the emphasis placed on

individual action and reflection in current audience engagement techniques which occlude

efforts that can be made in collaboration with one another. Any flexibility or ambiguity that

may have existed within the border between audience members and between the audience

and the stage, is quickly rigidified in the act of securing this silence. In this way, the

audience is left off the hook and the centre remains preserved and further fortified.

Furthermore, performances by those who seek to change their marginalized status risk

having the political thrust of their project neutralized and their differences further eradicated

and successfully co-opted in these intended celebrations of diversity. Therefore, the efficacy

of the social change project is deeply undermined by unintentionally cultivating a culture of

passive reception and isolated action amongst those who could potentially be allied with the

impetus of those seeking progressive change.

A critical collaborative performance pedagogy is needed as a foundation for a

relational praxis of social empowerment within applied theatre. Essential components of

such a pedagogy include dialogic processes between audience members and between

audiences and actors within a larger community organizing strategy. Contributions of such a

pedagogy will be an increased emphasis upon the experience of the audience and on

processes of supporting effective relationships; social networks that are capable of acting

upon the inequities staged. As the opening quote suggests, the stories of the teller(s) risk

becoming lost in translation when the listener(s) is not able to resonate, recognize or

identify with the experience staged. Therefore, such a pedagogical approach in the context

of performance will necessitate a continuous exchange of lived experience amongst

audience members always already diverse in their proximity to the realities staged.

Furthermore, the analysis of inequity and power, and therefore of social change, available to

7

the actors and the audience is obfuscated in audience engagement strategies that do not

attempt to name or negotiate the complicity of the collective, the audience members and

actors, in sustaining injustice. A critical, collaborative performance pedagogy will lay the

groundwork to better identify, proclaim, collectively examine, and address the structural

and interpersonal dynamics that silently maintain fixed centres and margins of power. As

these dynamics continue to persist, identifying obstacles to their transformation will also be

an important part of this approach. In this way, both externalized and internalized

boundaries that prevent mutual relationships between those who occupy the centres and

margins of power, in any given context, can be grappled with.

This thesis will, therefore, examine approaches to audience engagement within three

applied theatre projects towards defining the necessary elements of a critical, collaborative

performance pedagogy. I selected these three projects to provide a diversity of approaches

within applied theatre practice that will hopefully yield greater generalizability. The first

project, entitled It’s A Wonderful World: A Musical Ethnodrama (phase II), elicited and

staged the fears and aspirations of a group of adults living with developmental disabilities.

The second project, entitled Rights Here! (phase II), documented and staged the experiences

of racialized citizens and refugees living in Montreal. The third project, entitled Creating

Safer Spaces, invited newly arrived South Asian immigrants and refugee women to

collectively examine their experiences of dis/integration, and assimilation within Quebec,

Canada. These projects were not designed, a priori, to be best practices. However, through

this process of examination, I intend to articulate the basis of such a pedagogy. Hopefully,

the results of this thesis will include specific suggestions for effective audience intervention

strategies within applied theatre projects as well as the identification of major obstacles to

their implementation.

8

The significance of this research lies in the reality that the efforts that continue to be

made by ‘communities’ who seek to address disparities of power through theatre remain

compromised by a lack of attention to the processes of change within the audience.

Evolving a method of audience engagement towards effecting sustainable change within the

attitudes and behaviors of audience members is a necessary step towards re/imagining a

model of society that supports the mobility of people, resources, and ideas across centres

and margins of power. A critical collaborative performance pedagogy will support the

creation of sustainable social capital; strong social networks forged across social

differences. Furthermore, laying the groundwork for audience engagement will render

applied theatre practice an increasingly useful ally to alternative methodologies and

practices that also seek to galvanize sustainable relationships between individuals across

communities, with influential institutions, and with the State towards shared risk,

responsibility, and effort in decreasing poverty and realizing progressive change.

9

Chapter 2: Literature Review

Centres and Margins Power is stratified within society creating centres and margins of power demarcated

by in/visible and, at times, consensually sustained boundaries that restrict the flow of ideas,

resources and people. I find support for this in my reading of Antonio Gramsci (1971)

whose concept of hegemony describes how dominant groups have maintained binary

divisions of power through persuading those with marginal power to accept, adopt, and

internalize particular norms and values through the proliferation of ideology within varied

tools of cultural production (i.e. radio, television, film, music, theatre, art) authorized by

subalterns of the State including intellectual and moral authorities. The power of this

cultural hegemony is thus enforced primarily through coercion, cooptation, and consent

rather than armed force and re/produces social relations based on domination and

subjugation. Dominant groups also maintain centres and margins of power, (i.e. the status

quo), whether that is the privileging of a particular ‘race’, religion, economic system or

governing body, through multiple means of interpellation. Here, Louis Althusser’s (1971)

concept of interpellation refers to the process through which subjectivities are re/produced

and reinforced through the repetition of ideologically invested communication. Althusser

gives the example of the police officer who calls out ‘hey you’ and the guilty response of all

who, assuming they are being spoken to, turn. He argues that, even in the absence of an

easily located authority, subjects become complicit in the re/production of their identities

and in the preservation and architecture of unequal social relations through internalized

patterns of self-identification. This idea is similar to the proposal offered by Frantz Fanon, a

psychiatrist and scholar of the psychopathology of colonization, who asserted that the

10

internalization of dominant discourse concerning social difference regulates subordinate

groups by convincing them to accept the roles they have been prescribed (1967).

Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe define hegemony as a discursive strategy

combining principles from different systems of thought into one coherent ideology for the

purpose of securing consent (1985). Drawing on their ideas, Jennifer Daryl Slack (1996)

defines hegemony as "a process by which a hegemonic class coordinates the interests of

social groups such that those groups actively 'consent' to their subordinated status" (1996,

p.113). Both Althusser and Slack differ from Gramsci by dislocating hegemony as a

function unique to the State and assert that social boundaries in a particular context are

maintained through the proliferation of ideas, values, and norms embedded within the

cultural production of multiple dominant groups that form a hegemonic class, a group that

has the material means or the power, to ensure the survival of its ‘knowledge’ and its way of

life. Michel Foucault adds to this argument with his concept of ‘power-knowledge’ that he

uses to conflate the production of ‘knowledge’ by those who have the power to define it as

such (1981). He argues that modern society exercises its controlling systems of power and

knowledge through multiple forms of de/centralized supervision. Foucault suggests that a

‘carceral continuum’ runs through modern society, from the maximum security prison

through secure accommodation, probation, social workers, therapists, police, and teachers,

to our everyday working and domestic lives prescribing and asserting norms of acceptable

social behavior as involving the supervision of some humans by others (1977). This norm is

internalized to the point where visible guards are no longer necessary.

Expressions of hegemony are articulated by critical race theorist, Sherene Razack

(1998, 2008), who provides examples from within communities of racialized immigrant and

refugee women and people with developmental disabilities amongst others. She argues that

11

power is held by those who have the authority to assert their way of life and that this

‘centre’ continues to be constructed by white, able-bodied, heterosexual males. As a result,

those who do not fit this category are perceived and interpellated by the apparati of the State

and the media as homogeneous groups that deviate from the ‘norm’. Consequentially, these

groups are relegated to the margins where they experience restricted economic, social, and

political space; where their political agency is limited to their marginalized (and

internalized) status (Bannerji, 2000).

Within a hegemony, power emerges as having both internalized psychological

properties and externalized socio-political expressions and can be understood as the

potential of individuals and groups to transform their way of life and to sustain or stabilize

the changes they seek (Giddens, 1984). Therefore, a critical, collaborative, performance

pedagogy would require the explicit naming of the in/visible boundaries that create centres

and margins of power in order to begin to understand or change its influence over the

current social order in a given context.

The Need for Permeable Boundaries

Several theorists and practitioners across the social sciences challenge the efficacy

of a social model that relies upon a fixed margins and centres and argue the need for a more

permeable politic. In a discussion about economic development, Ash Amin, Doreen

Massey, and Nigel Thrift (2001) have noted how geographical divisions of power,

exemplified by large urban centres with peripheral entities, create rigid boundaries that limit

a reciprocal flow of ideas, resources and people. They advance the need for a relational

politic: social networks that can support innovation and development across and within

centres and margins of power as necessary within each particular context. They argue the

need to conceptualize space as a product of networks and relations in contrast to

12

territoriality, and advance the need for permeable borders enabling multiple and mobile

centres of deliberation and decision-making that can bring together different people with

differing ideas together to the exercise local democracy. Martha Nussbaum (2000) also

contributes to the argument for increased permeability in the boundaries between centres

and margins of power in her articulation of the concept of a capabilities approach to human

development. She argues the responsibility that governments have to provide a basic

threshold of material prerequisites to their constituents in order to increase the mobility of

impoverished groups by making it possible for them to exercise their choice to realize the

totality of what they can be and do.

Feminist scholar, Audre Lorde (2007), presents an argument for why social

boundaries persist. She advances that social boundaries such as racism, sexism, and

homophobia persist because of society’s failure to move beyond oppressive, dualistic

relations of power. In her often cited essay, The Master’s Tools will Never Dismantle the

Master’s House, Lorde deftly articulates the continued oppression of women within the

feminist movement as a result of the movement’s over-reliance on the unequal social (and

economic) relations prescribed through the ideological apparatus of dominant groups. She

argues that, by denying permeability in the category of women, feminists merely pass on

old systems of oppression substituting white slave-masters with white feminists and that, in

so doing, prevent any real, lasting change. Lorde’s argument is useful in understanding how

an over-reliance on a social model that necessitates dominant and subordinated groups, a

reliance on a fixed binary of centre and margin, will ultimately fail in diminishing present

day human suffering or achieving sustained equity and justice.

In the same vein, cultural studies theorist, Homi Bhabha (1994), aptly articulates the

13

inherent violence implicit in the persistent re/production of the centre/margin (white/black,

good/evil) binary stressing the limitations it places on a society’s capacity to imagine

equitable social relations that do not rely on violent and harmful subjugation. Through the

use of his concept of the third space, Bhabha argues for increased permeability in this

construct asserting that, once this binary is destabilized, cultures can be understood to

interact, transgress, and transform each other in a much more complex manner than

traditional binary oppositions can allow. This thinking requires a shift towards

understanding social relations and the prescription of power as being dis/located from the

colonizer/colonized mentality where power is derived from consistency and homogeneity

towards an acceptance of power as derived from flexibility and multiplicity expressed

through overlapping, ever-shifting subjectivities and mobile, differentiated forms of power.

Therefore, attempts to destabilize and redistribute power cannot occur without attending to

the multiple economic, social, and resulting psychological boundaries that restrict the

mobility of ideas, people, and resources that obstruct substantiated pathways to self-

determination and sustainable change within and between current centres and margins of

power. Relational networks, alliances and coalitions emerge as necessary to the function of

this mobility and, in the final instance, may contribute to the collapse of a singular and fixed

social order. Therefore, a critical, collaborative performance pedagogy would embody and

inspire relational networks that are capable of navigating a ‘third space’ between the rigid

extremes of ‘centre’ and ‘margin’ in order to move towards greater permeability across

current dividing boundaries.

14

Asymmetrical Development: Change Without Disrupting the Boundary

Efforts to increase permeability, while they may attempt to depart from hegemonic

strategies, have relied upon an asymmetrical relationship between the centre and the

margins wherein those occupying marginalized space are tasked with transforming

themselves with minimum disturbance or risk to the centre. The ideal of empowering the

marginalized has, in theory, been a driving force of the social justice project. The thinking is

that by enabling the poor to analyze their own realities and thus influence development

priorities, they will have greater ability, confidence and skills to act more effectively in their

own interests (Nelson and Wright, 2000). This has been paradoxically disempowering as,

although “community matters, its efforts are often compromised within a dominant

paradigm that relegates community to the margins”(Mendell, 2005, p.1).

Eric Shragge (1997) describes how community organizing has either subscribed to a

model of social action in which it is incumbent on marginalized communities to pressure

the State to have their needs met, or to a model of community development in which it is the

responsibility of the community to achieve consensus about their challenges and to address

these with local programs and services. An example of social action might be Nussbaum’s

Capabilities Approach in which she argues that pressure be put upon the State to provide a

basic threshold of material welfare (2000). An example of the community development

approach might include the asset-based appreciative approach authored by John P.

Kretzmann and John L. McKnight (1993) that involves the identification and mobilization

of a geographically defined community’s strengths and resources as a means of realizing

desired changes. In both models, the emphasis is largely placed on the marginal group to

transform itself without changing the prescription of power that would relegate some human

beings to the margins.

15

Challenges to Asymmetrical Development from Community Economic Development and

Liberatory Pedagogies

Community Economic Development

Challenges to asymmetrical development have been articulated through a growing

interest in the social economy and in the varied practice of community economic

development (CED). While an exhaustive review of social entrepreneurship and social

enterprise are beyond the scope of this thesis, there are several key insights from this body

of knowledge that contribute to an understanding of rigorous and effective social

intervention. The Canadian Community Economic Development Network defines CED as:

An action by people locally to create economic opportunities and better social conditions, particularly for those who are most disadvantaged. CED is an approach that recognizes that economic, environmental and social challenges are interdependent, complex and ever-changing. To be effective, solutions must be rooted in local knowledge and led by community members. CED promotes holistic approaches, addressing individual, community and regional levels, recognizing that these levels are interconnected (Canadian CED Network, www. www.ccednet-rcdec.ca).

CED is a diverse set of approaches to community development that share an

understanding that poverty is a primary dividing factor in creating social boundaries that

result in centres and margins of power and correlating social conditions. The practice of

CED is primarily concerned with fostering permeability between and within the boundaries

of society towards a continuum of objectives: from local job creation involving varying

degrees of internal and external investment to a redefined relationship to one’s land, labor

and capital in ways that return autonomy and decision-making power to the individual and

16

community. Shragge (1997) asserts that CED involves much more than local job creation,

but is an approach to addressing poverty and, as such, should involve an analysis of the

intersections of race, gender and class. In his analysis, racism, homelessness, environmental

degradation, inadequate child-care, and gaps in social programs create and sustain poverty.

Shragge advocates what he sees as a progressive vision of CED offered by Michael Swack

and Donald Mason who argue that “the starting premise for CED is that communities that

are poor and underdeveloped remain in that condition because they lack control over their

own resources” (Swack and Mason cited in Shragge, 1997, p.12). Therefore, according to

Shragge, a progressive approach to CED would not only focus on the development of local

programs and institutions but would also include analyses and actions directed against the

wider processes that prevent local control over local resources; preventing communities

from addressing poverty.

The wider processes that govern local expressions of democracy and social welfare

have been the primary subject of interest to proponents of the social economy which has

been conceptualized as the non-profit, voluntary, community or third sector, occupying a

space between public and private economics and involving liberal and socialist traditions

(Ninacs, 2002). Proponents of the social economy foreground its social dimensions. As

Marguerite Mendell puts it, the “economy itself is intrinsically and inevitably social…we

know that it cannot function without institutions, without people, without community

support, [and] without an accommodating State” (2003, p. 3). A recent review of the types

of development espoused by proponents of the social economy indicate that they have

departed from a socio-democratic model where social issues are the exclusive domain of the

state and redistribution the only possible regulatory mechanism (e.g. state funded maternity

leave, heritage and culture grants). They have also departed also from a neo-liberal model

17

where social issues relate only to individuals who do not or cannot take part in the market

economy and whose needs are seen as ‘unprofitable’ (e.g. childcare, senior’s homes,

immigrant and refugee settlement services) (Ninacs, 2002). Instead, William Ninacs notes

that recent articulations of the social economy seek a model of economic and social

democracy where social issues would concern both the state (redistribution) and society

(reciprocity, participation in the market) (2002). In this model, the economic players would

be more numerous, not only including trade unions, but also women, racialized community

groups, youth, and other marginalized or subjugated members of society. Examples of this

might include (partially) state supported yet collectively operated artisan, food, or trade

collectives that employ persons with mental or physical disabilities, create goods and/or

services for the market and reintegrate people into the economy while engendering

increased autonomy and providing a meaningful avenue for social, economic, and political

participation. This model faces a number of limitations and requires several difficult socio-

economic transformations such as the reduction of hours worked, greater worker

democracy, and more collective services (Shragge, 1997; Fillion, 1998; Lévesque &

Mendell, 2001; Lowe, 2007).

Conditions that may enable these transformations are proposed by Louis Favreau and

Benoît Lévesque (1996) who emphasize the need for dialogue and deliberation in their

approach to the economic and social revitalization of communities. In the same vein,

Giancarlo Canzanelli emphasizes the necessity of beginning with “social networks of

different people capable of working together for a common objective in an organized and

voluntary manner, sharing rules and values, and able to subordinate individual interests to

collective ones”, as a core requirement in advancing the needs of a given community and

achieving desired change (2001,p.12). Each of these proponents of equitable local

18

development argue the need for multi-stakeholder forums, avenues for dialogue and

deliberation with people of differing levels of power. However, as noted earlier by

Nussbaum, dialogue and deliberation is not empowering when it is not substantiated with

enabling material conditions (2000). Social economist, Mendell states:

Empowerment in any sense that really matters must result in a substantive transfer of resources; the presence of new actors on the scene contributing to a cacophony of voices generating noise, while important as a sociological phenomenon, is not in and of itself empowering (2009, p.1).

In the absence of responsibility shared by those who hold decision-making power, the

boundary between the centre and the margin is not only maintained, but potentially

solidified as the margins continue to compete with one another, reinventing themselves to

receive financial and social support from the State, in effect concealing internal tensions

and distracting them from collectively addressing the structural inequities that give rise to

economic, social, and political poverty.

The implications of this analysis of the social economy and practices associated with

CED for a CCPP are multiple. First, a CCPP would need to ground itself in an analysis of

what phenomena contribute to the disenfranchisement of communities from their own local

resources and their own capacities to address poverty. Secondly, these perspectives

reinforce the importance of cultivating strategic alliances with influential agencies and the

State through spaces of dialogue and deliberation as a means of encouraging cross-sectoral

investment in shared social aims that can result in a useful transfer of resources when

indicated. Thirdly, a CCPP would need to grapple with its contribution to increased local

decision-making power towards greater control over local land, labor and capital.

Ultimately, the perspectives offered within this discourse encourage a thinking through of

19

how change is pursued; whether it is through empowering local ‘actors’ to pressure the state

or other legislative bodies (social action), whether it seeks to mobilize communities to meet

their own needs through the identification and development of necessary social programs

(community development), and/or whether it seeks to insert itself within the ‘third space’ of

the social economy in some form.

Liberatory Pedagogies

There are also examples of pedagogical and research models that attempt to deviate from

asymmetrical approaches to development and, while they begin with the efforts of

marginalized groups, they also lay the groundwork for engaging marginalized communities

in an exercise of local decision making and change efforts. An excellent example of

transformative participatory pedagogy was developed by Paolo Friere (1970) who evolved

his Pedagogy of the Oppressed in a time of extreme political repression in Brazil where

equitable partnerships between centres and margins of power were not easily realized nor

expected. His liberatory literacy education involved not only reading the written word, but

also reading the world through the development of critical consciousness or

conscientization. A critical consciousness allowed people to question the nature of their

historical and social situation with the goal of acting as subjects in the creation of a

democratic society rather than passive objects to be dominated by an oppressive

government. His popular education methods countered the dominant system of education, a

system inherently oppressive and dehumanizing that he described as a “banking model”

where students were passive recipients of the teacher’s knowledge. Within Friere’s popular

education, people bound by a similar struggle were understood as active co-producers of the

knowledge that was necessary to their ultimate emancipation.

20

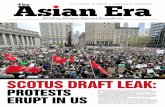

The Spiral Model of Community Action (Figure 2.1) illustrates the popular education

process.

Figure 2.1: Popular Education: The Spiral Model of Community Action (Arnold et al. 1991, p. 38)

Through raised awareness and collaborative action, popular education practices draw on and

validate participant knowledge, or situated expertise, in the production of new knowledge.

Through iterative cycles, a praxis, of critical dialogue, collective reflection, and problem

posing, participants discuss the possibilities of transforming the oppressive elements of their

experience culminating in collective social action.

Freire’s emancipatory epistemology contributed to the emergence of participatory

action research (PAR) methods that shared his values of equitable participation, direct

experience and action, and that emphasized the inter-subjective nature of knowledge

creation and dissemination (Orlando Fals-Borda, 1981; Park, Brydon-Miller,Hall, &

Jackson, 1993; Greenwood and Levin, 1998; Reason and Bradbury, 2008). Friere (1982)

21

wrote, "The silenced are not just incidental to the curiosity of the researcher but are the

masters of inquiry into the underlying causes of the events in their world. In this context,

research becomes a means of moving them beyond silence into a quest to proclaim the

world” (p. 30). However, these approaches have also garnered critique and speculation

relating to the persistence of asymmetrical power in PAR processes. Robert Chambers

(1983) indicates:

However much the rhetoric changes to participation, participatory research, community involvement and the like, at the end of the day there is still an outsider seeking to change things... who the outsider is may change but the relation is the same. A stronger person wants to change things for a person who is weaker. From this paternal trap there is no complete escape. (p.37)

Chambers notes the ways in which researcher-community relationships will continue to

assert an influence on local power dynamics and asserts that community participation in

such a context should be recognized for what it is, an externally motivated political act with

differing benefits to those involved. Chambers’ point is similar to that of Lorde’s (2007) in

that working within a system in which there are centres and margins, stronger and weaker,

will not eradicate the continuance of these binaries. However, this fact alone should not stop

efforts at emancipation and equity. The pedagogical and research methods which have

emerged from Freire’s work attempt to counter the asymmetry of empowerment efforts by

extending responsibility for reducing harmful marginalization to those who may not see

themselves, initially, as having a part in the same struggle, as part of the same ‘community

of interest’ to use Baz Kershaw’s term (1992). Collaboration across margins and centres of

power is necessary to the realization of permeable boundaries and possible solidarities.

What is also required, therefore, is a means of increasing transparency in the declaration of

22

a project’s intentions, the identification (not eradication) of differing biases and

investments, and multiple avenues to assess and ensure an ethic of equitable participation.

Applied Theatre

Change processes within applied theatre repeat this formulation of seeking social

change or transformation through the empowerment of marginalized groups. The term

Applied Theatre is relatively new and brings together a broad range of dramatic activity

carried out by diverse individuals and groups that vary in the intention they bring to their

practice. The Centre for Applied Theatre Research in Manchester (CATR), founded by

James Thompson in 2001, refers to applied theatre as “the practice of theatre and drama in

non-traditional settings [including] theatre practice that engages with areas of social and

cultural policy such as public health, education, criminal justice, heritage site interpretation

and human development”(CATR, 2008, para 1). Judith Ackroyd (2000), advances that

Community Theatre, Theatre in Education, Drama in Education, Theatre for Health

Promotion, Popular Theatre, Drama Therapy, Sociodrama, and Psychodrama all fall within

the range of the umbrella term Applied Theatre. In each case, Ackroyd identifies the

underlying basis in each of these practices to be a belief in the transformative capacity for

theatre ‘to address something beyond itself’ referring to the efficacy- entertainment

continuum proposed by Richard Schechner (1994) wherein he describes a performance that

is efficacious as one whose purpose is to ‘effect transformations’. However, efforts to

effect these transformations are located primarily in the margins, wherein the lived realities

of those suffering varied forms of internalized, relational, or systemic violence are provided

an art form and a platform from which to render visible the suffering they face (James,

1998, Jennings, 1998, Ackroyd, 2000). Ackroyd draws attention to the lack of analysis

about the ideologies that underpin the desire to transform marginalized communities nor

23

attention to the means through which interpersonal or institutional intervention and

transformation is achieved and sustained:

Looking at much of the applied theatre forms frequently identified, there is an implicit political bias…there is a crying need for evaluation of applied theatre. Research is required to look at the efficacy of applied theatre in its various forms. We need to know what distinctive contribution drama can make to changing attitudes and behaviour, and to be alert to any unintended consequences of using it. (Ackroyd, 2000, p. 2) Efforts to effect change within society through applied theatre, to render permeable the

boundaries that limit the freedom of particular social groups and which give rise to the

multiple forms of violence they face, have also centred on the potential capacity of those

who bear witness: the audience. Ackroyd emphasizes the importance of the audience,

stating that “there are two features which [are] central to our understanding of applied

theatre: an intention to generate change (of awareness, attitude, and behavior), and the

participation of the audience.” (2000, p.3). She is not alone in her call for ‘more’ in our

analyses of the efficacy of applied theatre. In the following sections, I will present and

discuss the articulation of audience participation in drama therapy and in community theatre

practice situated as two sets of approaches to applied theatre that differ in intention and

approach yet compatible in their desire to promote progressive social change.

Drama Therapy

The often stated intention of drama therapy is to facilitate emotional growth,

development, and behavioral change through the systematic and intentional use of theatre

processes with individuals, couples, families, and groups in a variety of contexts and

settings (Emunah, 1994). The practice of drama therapy is varied in its approaches and is

used in the private space of therapy within traditional mental health clinics, within social

service, educational, corrective, and healthcare agencies and institutions and in therapeutic

24

public performance (Mitchell, 1994, Johnson and Lewis, 2000; Snow, 2009). In this way,

drama therapy is traditionally thought to operate within the nexus of theatre and

psychological intervention. Within the context of drama therapy, audience interaction is

deeply intertwined with witnessing and understood as one of nine core processes central to

the therapeutic function and fundamental efficacy of this practice (Jones, 1996). Phil Jones

defines witnessing as an action that “ is an important aspect of the act of being an audience

to others or to oneself in Dramatherapy” (p.109). He stresses the multiple opportunities for

the participant in drama therapy to ‘en-role’ as an audience to the process of others, thereby

supporting other group members in their expression of themes of concern. He also stresses

the therapeutic function of witnessing as being related to the process by which participants

in drama therapy develop their own internal capacity to be an audience for themselves

through activities such as role-reversal towards gaining increased perspective on their own

challenging situations. Within his formulation, witnessing emerges as an action and the

audience is seen in a singular, unified role. The audience is either internalized or a fluid,

interactive role undertaken by group members at different points during the therapeutic

process; externalized without necessarily requiring a formal separation of actor and

audience.

Jones (1996) asserts that, where there is a formal demarcation between actor and

audience such as within performance-oriented drama therapy, the act of witnessing is

rendered increasingly visible “[enhancing] the boundaries concerning being in and out of

role or the enactment, [heightening] focus and concentration [and] the theatricality of a

piece of work” (p.111). The potential psychological benefit to the participants involved in

both the processes leading up to performance and the final enactment is discussed elsewhere

(Emunah, 1994; Jennings, Cattanach, & Mitchell, 1994; Johnson and Lewis, 2000; Snow et

25

al., 2003). However, Jones concludes that “much consideration has gone into the dramatic

work that occurs for those involved in the enactment, but much less has gone into the notion

of audience in Dramatherapy” (p.110). This is not surprising as the therapeutic contract

implicit in performance-oriented processes, such as in self-revelatory theatre (Emunah,

1994) or therapeutic theatre (Mitchell, 1994, Snow, 2009), privileges the therapeutic benefit

conferred to participants who shoulder the burden of risk in disclosing their vulnerable

experiences to their friends, family, and wider public. Here, the role of the audience is often

constructed as a necessarily homogeneous entity, uniform in its desire to applaud the efforts

of the performer and validate the aesthetic and creative expression of those who have given

embodied testimony. In this way, the audience is positioned as a supportive network capable

of re-integrating those who have experienced being ‘cut off’ from society as a result of the

suffering they endure(d) (Johnson, 1980; Emunah and Johnson, 1983; Emunah, 1994; Borch

and Rutherford, 2007; Johnson and Lubin, 2008).

The sacredness conferred to performances which arise from therapeutic intentions,

while providing a unique sense of affirmation, may also obfuscate further analysis of the

suffering staged during post-performance audience interaction processes as the audience is

largely directed to value the potential psychological emergence offered by the therapeutic

performance. However, Renee Emunah (1994) also, albeit briefly, gestures at the social

impact of performance-oriented drama therapy as it situates private experience in the public

realm and, in doing so, extends opportunities for public education about marginalized

populations. She writes of communities of people bound by a common struggle, be it to

overcome drug abuse, sexual assault, homelessness, or the experiences of immigration by

staging their own experiences “that have been hidden from pubic domain…stories that

have been kept secret…on stage [they] come out with their private identities and histories”

26

(p. 251). However, the processes by which audiences are increasingly educated about the

private experiences faced by marginalized groups, or the definition and processes implied

by overcoming the challenges participants face are largely underdeveloped in this field.

Indeed, the nature and scope of witnessing and audience interaction within performance-

oriented drama therapy has been limited to analyses of the therapeutic benefit conferred to

participants through uniformly empathic witnessing from a decontextualized, socially

unsituated audience and, in this way, largely disregards the potential within the audience to

contribute to or sustain any kind of change.

Fred Hickling and Hilary Robertson-Hickling (2003, 2005) also agree that the act of

situating private identities within the public realm through performance opens up

possibilities for social and cultural change. They develop this idea in their

psychohistoriographical approach to performance that they situate as a form of cultural

therapy. Hickling and Robertson-Hickling visited Montreal, on invitation by Stephen Snow

of the Creative Arts Therapies department at Concordia University, in 2005 and 2007 to

teach this approach that involves the staging of a group’s collectively created biographical

performance. Jaswant Gudzer, a trans-cultural child psychiatrist who participated in their

workshops, describes the process as follows:

This process encompassed themes of cultural identity, intergenerational transmissions of trauma, timelines of history, and identity hybridization in the context of inter-cultural realities. The psycho-historiography process is a cultural therapy model that builds on concepts of the group’s psychic centrality (the implicit psychological themes pertaining to the group) and reasoning, (in the context of the historical timeline, and elements of individual and collective identities). These elements are then transformed into a script and performance reflecting this group process1.

This approach has resulted in rich and evolved group processes wherein group members, in

addition to embodying the trajectory of traditional group therapy (Yalom, 2005), grapple

with their enmeshment within historically determined and politically inscribed dialectics.

27

However, it also lacks an effective audience interaction process that, consequentially, limits

its social goals as evidenced by frustrated audience-stage communication post-performance.

Hickling and Robertson-Hickling’s ideas about cultural therapy are complemented by

contemporary ideas about the conjecture of social justice and therapy. There is a growing

trend in psychotherapy to challenge inequality and commit to social justice. This is

evidenced by efforts to question the presumed neutrality of the therapist and to re/define the

role of the therapist to include outreach, prevention, and advocacy. Related ideas also

include enlarging the therapeutic space to include community specific locations, usefully

blurring the boundaries between the public and private by calling for public accountability,

situating the encounter between therapist and client in sustainable partnerships and

participatory practices, and in reformulating the purpose of therapy as facilitating individual

and/or a group’s capacities to identify, analyze and address the internalized, relational and

systemic dynamics which limit the full arc of their desires (Thompson, 2002; Vera and

Speight, 2003; Holzman and Medez, 2003; Fanon, 2004, Toporek et. al, 2006).

Community Theatre

Turning attention to other approaches within applied theatre, Eugène Van Erven (2001)

uses the umbrella term community theatre to describe practices that operate in the nexus of

performing arts and socio-cultural intervention. This definition echoes the continuum

suggested by David Hornbrook’s (1998) definition of theatre as a ‘dramatic art’ and Betty

Jane Wagner’s (1979) ascription of theatre as a ‘learning medium’. Van Erven further

situates community theatre as a practice of cultural democracy involving the localized

cultural expression and representation of participants’ interests and personal stories

resulting in community dialogue, the diminished exclusion of marginalized groups, and an

opportunity to engage in collectively oriented improvisation. In addition to cultural

28

democracy and cultural expression, Edward Little (2005) advances that a relational

aesthetic, in which the aesthetic merits of community theatre are intertwined with its

relevance to its constituent communities, separates community theatre from mainstream

production. The intention of community theatre is further elaborated by Little who states

that “an overarching intent common to community-based theatre is to create an iconic

representation that celebrates negotiated values, privileges human creativity (as opposed to

expensive and resource-consuming technological solutions), and affords a pragmatic

appreciation of the potential utility of art as a resource-effective means of addressing

community concerns” (p. 4). Jan Selman and Tim Prentki (2000) describe the intention of

popular theatre as a means of fostering a critical consciousness and, in this way, link their

definition to Freire’s (1970) principles of education that embraced notions of exchange,

participant ownership, reflection and action. Although there may certainly be debate in the

field, the popular theatre process is often thought of as following particular stages that bear

resemblance to Freire’s popular education process described earlier (Kidd, 1989, p.21).

Figure 2.2 delineates the process of theatre-making as involving specific communities

forming a group identity and then embarking on an iterative cycle of identifying issues of

concern, analyzing current conditions and causes of a situation and expressing such through

the theatre medium, identifying potential points of change, and analyzing how change could

happen and/or contribute to the actions implied.

29

Figure 2.2: Stages of Popular Theatre (Kidd, 1989, p.21)

Within this process, audience participation is understood as necessary to the function of

community organizing wherein the analysis developed by group members is extended to the

public, further analyzed and propelled into community action. Applied theatre requires

audience interaction strategies that can facilitate this praxis and that can respond to the

challenge presented by Jan Selman and Shauna Butterwick (2003) to “create a radical kind

of empathy, one that recognizes the danger of story telling and the inequality of risk in the

story telling process, one that creates spaces and relationships where stories are told and

heard.” (p. 9).

Critical Ideas about Audience Engagement in Applied Theatre

The emphasis placed on audience interaction in theatre to achieve a redressive purpose

or to effect social transformations has a significant history marked by differing opinions

about the purpose and place of catharsis (i.e the place of emotional release) in effecting

social change. Indeed, the history of applied theatre has had a challenging and continuously

evolving understanding of the overlap between theatre as therapy and theatre as social

30

intervention (Spolin, 1963;Brook, 1968; Schechner,1973; Fox, 1994). In the sections that

follow, I will present and discuss specific contributions to this discourse from several

theatre theorists as well as applied theatre practitioners.

Antonin Artaud: The Theatre of Cruelty

Antonin Artaud had significant ideas about how to effect change within the audience. He

wanted theatre to return to a form of pure magic and an event where a revolutionary

catharsis of the audience could take place. Artaud writes:

Everything in the order of the written word which abandons the field of clear, orderly perception, everything which aims at reversing appearances and introduces doubt about the position of mental images and their relationship to one another, everything which provokes confusion without destroying the strength of emergent thought, everything which disrupts the relationship between things by giving this agitated thought an even greater aspect of truth and violence - all these offer death a loophole and put us in touch with certain more acute states of mind in the throes of which death expresses itself. (Artaud, 1971:92)

Artaud was rallying against traditional French theatre which traditionally began with

proposing a problem at the beginning of a play and providing a solution to this problem by

the end of the play. He was overwhelmed by a performance of Balinese theatre that he

witnessed at the Colonial Exposition in Paris in 1931 and it cemented his belief that a

dramatic presentation should be an act of initiation during which the spectator will be awed

and even terrified to such a degree that they may even lose their reason. He proposed that,

during this induced frenzy, the spectator would be able to take onboard a complete new set

of truths, revelations into the true nature of society. So, Artaud sought a theatre that would

disturb the mind in order to open the subconscious, driving people back to their ‘primitive’

nature. His dictum, “Squeeze a man hard and you’ll always find something inhuman”,

31

inspired many theatre companies, outraged at the complacencies of modern culture, to

develop a theatre of confrontation that shocked and even outraged their audiences (Dale,

2002). The effect on spectators was absurdly emotional, but far from cathartic as, for

Artaud, all freedom was “dark, and infallibly identified with sexual freedom”. Thus, his

‘theatre of cruelty’ forced upon the audience the violent, the ugly, and sexually ‘perverse’.

Bertholt Brecht:“Verfremdung”(German): Audience Estrangement

Brecht took a different approach to encouraging revelations about society amongst his

audiences. For him, the theatre of catharsis was a means of robbing the spectator of an

essential autonomy as a thinking person. His idea of verfremdung, a stylistic element of

audience estrangement was designed to encourage the viewer to reflect on, rather than

identify with, the events on stage. Audience reception theorist, Susan Bennett (1997),

emphasizes the influence of Brecht in this discourse. She states that Brecht is “important for

any study of audience/play relations…his ideas for a theatre with the power to provoke

social change, along with his attempts to reactivate the stage-audience exchange have had a

profound impact on critical responses to plays and performance” (p.21). Brecht’s objective

was to provoke a critical yet entertained audience. Cultural theorist, Walter Benjamin

describes Brecht’s process:

A double object is provided for the audience’s interest. First the events shown on stage; these must be of such a kind that they may, at certain divisive points, be checked by the audience against its own experience. Second, the production; this must be transparent as to its artistic armature…Epic theatre addresses itself to interested parties ‘who do not think unless they have reason to’. Brecht is constantly aware of the masses, whose conditioned use of the faculty of though is surely covered by this formula. His effort to make the audience interested in the theatre as experts- not at all for cultural reasons-is an expression of his political purpose (1973, p.15-16)

The notion of a theatre engaging an audience for anything other than ‘cultural reasons’,

for entertainment or aesthetic achievement, highlighted the failure of theatre to address

32

contemporary concerns and also revealed theatre as an apparatus of the State. In this way,

Brecht’s epic theatre rearticulated and politicized the relationship between the audience and

the stage. The risk of sustaining the status-quo by forgetting or overly simplifying the

function(s) of the audience is best summed by Brecht as he points out how contemporary

practice constrained a direct relationship between audience and the stage: ‘[t]he theatre as

we know it shows the structure of society (represented on stage) as incapable of being

influenced by society (in the auditorium)’ (Willet, 1964, p.189). While the technologies of

participation in society have changed and mobility has increased for some, Brecht’s

observations remain increasingly important today given the persistence of poverty and the

differential access particular individuals and communities have to realizing their full

potential based on their membership in particular social groups.

Phil Jones and Robert Landy: empathy and aesthetic distancing

Within the discourse of drama therapy, Brecht’s concepts have been translated into the

concept of distancing which has been described as a means of engendering thought,

reflection and perspective (Jones, 1996). Jones also offers that empathy wrought through an

emotional resonance or identification with the situation staged and that the experience of

empathy and distance is different for the actor and for the audience, but both processes are

present within each role. Robert Landy adds to this with his articulation of aesthetic

distance which he describes as the “balance of affect and cognition, wherein both feeling

and reflection are available” and necessary to the prospect of catharsis when encountering

painful realities (1993, p.25). These concepts drawn from literature in drama therapy have

not been applied to audience interaction but are useful to the evolution of a CCPP in their

emphasis on the necessity for both visceral and intellectual engagement in the project of

change.

33

Augusto Boal: The Spect-actor and the Joker

Beyond Brecht, perhaps the most well articulated and widely used audience interaction

strategies are those of Augusto Boal, originator of a composite system of politically oriented

theatre-based practices known as the Theatre of the Oppressed (T.O.) (1979) and a

contemporary of Paolo Freire (1970). Boal developed his theatre in the early 1960’s in

South America in response to the military dictatorship in Brazil and later, in Europe, in

response to internalized oppression and its constellation of anxiety, depression, isolation,