the provision of nursery education in england and wales to ...

Nursery Education

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

2 -

download

0

Transcript of Nursery Education

1

NURSERY EDUCATION

RESEARCH REVIEW REPORT

FOREWARD

This research review, which was prepared for the EIS Working Group on Nursery Education, is an important and timely document. For the first time the document sets out all the research relevant to Scotland on the impact of nursery education on young people before they enter the primary school.

Some of the research has been well publicised and some has to date received very little publicity. All available quality research points in one direction and that is of the immense value of high quality nursery education for very young children. The research review also rejects importing to Scotland other models of pre-5 provision which reflect the culture and educational background of other countries and which would not operate successfully in Scotland with its own traditions and educational history.

The report indicates that qualified nursery teachers are right at the heart of quality nursery education. This is particularly true at a time when pupils, aged 3-18, are adapting to the new Curriculum for Excellence. This is a message which is of paramount importance at a time when Government – Westminster, Holyrood and local authority – are planning massive cuts in education expenditure. The EIS believes that the route out of the current economic crisis lies in part in quality education provision for all our young people. This starts with our youngest children and their entitlement to access to quality nursery education provision.

The report was prepared by George MacBride an independent consultant, previously with a long term association with the EIS.

I commend the report to you and encourage you to share its contents as widely as possible.

Margaret Smith

Nursery Teacher, Deanburn Primary School, Bo’ness.

Convener of the EIS Working Group on Nursery Education

and Member of EIS Council and of the EIS Education Committee.

3

Report to EIS Working Group on Nursery Education

October 2010

1. Introduction

1.1. This paper has been produced for the EIS Working Group on Nursery Education. At a time when this sector of education is subject to considerable change, this paper uses a range of evidence to identify a number of issues related to pre-school education and to lead to conclusions for consideration by the EIS.

1.2. This paper was written over the summer of 2010. It draws on a range of reports and articles, especially published research and policy documentation. It is hoped that all of this is fully acknowledged and that findings and views are accurately reported in this paper. Responsibility for any inaccuracies, errors or misrepresentation lies with the author of this paper.

1.3. In accordance with common usage, ‘pre-school’ is applied to children under the age of compulsory education and to services provided for them; the inconsistency of this usage with the concept of nursery education, as usually understood, is acknowledged.

5

2. Executive summary

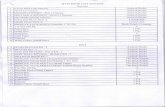

Note: the figures in parentheses refer to the relevant sections of the report.

2.1. The model underpinning pre-school provision in the UK, including Scotland, is one based on a historical dichotomy between education and care. (3, 4)

2.2. This pattern is now unusual in Europe where integrated services are common. (3)

2.3. Nursery education provided by a teacher has been highly valued in Scotland. (3)

2.4. Nursery education provided by a teacher has been threatened by policy developments in Scotland, including, cost-saving, neo-liberal dogma and the use of early years provision as a means of encouraging parents into employment. (3)

2.5. This model has been elaborated to include neo-liberal approaches to developing a market in early years provision which results in a dichotomy between public and private provision. (3)

2.6. This model was originally based on theories of early childhood development which did not recognise that young children’s learning depends on interaction with others. (4)

2.7. These theories have been replaced in by theories in which learning is a social activity. (4)

2.8. Concepts of the early childhood worker as a technician are inconsistent with our understanding of young children’s learning. (4)

2.9. The concept of the insufficient child puts at risk the concept of a universal service based on this model of effective learning. (4)

2.10. This understanding of the child as an active learner is reflected in curricula in many countries, including Curriculum for Excellence. (4, 8)

2.11. There are clearly established markers of good policy and practice in the provision of early years services. (4, 5, 9, 10, 11, 13, 32)

2.12. Workforce organisation in Scotland reflects out-dated historical views of early years provision. (5)

2.13. Funding of pre-school services in the UK, including Scotland, is lower than that in many other countries. (6)

2.14. Policy debate and formation has failed to consider alternative models and levels of funding. (6)

2.15. Much provision is dependent on payment by parents, supported to some extent by tax credits. (6)

2.16. The funding model is likely to drive down levels of funding available to pre-school services. (6)

2.17. It is important to avoid any risk that this funding model results in provision which is likely to reduce social cohesion. (6)

2.18. Policy debate and formation in Scotland has been marked by an uncritical acceptance of models of practice. (6)

6

2.19. A number of education policies in Scotland recognise the common features of an inclusive high quality education from the early years through primary and into secondary education. (7)

2.20. Curriculum for Excellence is based on an understanding of children’s development and learning which is common to all learners from 3-18. (8)

2.21. Curriculum for Excellence is based on broad and inclusive definitions of the curriculum and of learning and achievement. (8).

2.22. Curriculum for Excellence makes clear the importance of coherence among curriculum, pedagogy and assessment. (8)

2.23. Curriculum for Excellence recognises the importance of teaching. (8)

2.24. There is extensive robust evidence of the importance and value of the teacher in pre-school education to ensuring successful learning and positive outcomes for children. (9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 16)

2.25. The positive impact of teachers in pre-school centres is both immediate and long term, lasting through the primary stages of education. (9, 10, 11, 12, 13)

2.26. The reasons for this positive impact are clearly identified in much research: it is behaviour which can be described as ‘teacherly’, challenging and supporting children to extend and reflect on their thinking. (9)

2.27. There is evidence that the employment of staff with higher level qualifications, other than teacher qualifications, leads to improved outcomes for young children. (9)

2.28. There is extensive and robust evidence that nursery schools and classes, staffed by qualified teachers, lead to better outcomes for young children than other forms of pre-school provision. (9, 10, 11, 12, 13)

2.29. There is evidence that the quality of public sector provision of services for children in general is better than private or partnership provision. (9, 10, 11, 14, 16, 17, 18)

2.30. There is very clear evidence that the number of teachers employed in the pre-school sector in Scotland is well below the number required to ensure the policy commitment that all 3 to 5 year olds have access to a teacher. (14, 15)

2.31. There is evidence that access to a teacher is interpreted in a range of ways. (14, 15, 18, 21, 23)

2.32. There is little evidence of Scottish Government or local authorities using evidence to inform policy development and implementation in the field of pre-school services. (19, 20, 21, 22)

2.33. There is evidence that the quality of placements in the pre-school sector provided to preservice primary teachers has been put at risk by pressures on university faculties and schools of education. (21)

2.34. The capacity of university faculties and schools of education to provide qualifications (teacher, pedagogue, child studies, CPD) is also likely to have been put at risk by cuts in their funding. (21)

2.35. There is clear evidence in Scotland that teachers are deployed (other than in nursery schools and classes) in ways that are likely to their having a limited impact on children’s learning. (23)

7

2.36. While levels of teacher staffing and models of deployment are generally better in local authority provision than in partnership provision, there are local authorities with very poor levels of provision in their own establishments. (23)

2.37. There is evidence that levels of provision are the results of policy decisions taken, sometimes explicitly, within local authorities. (23)

2.38. The Scottish Government and local authorities have access to detailed evidence about local authority provision of pre-school services and the extent to which these reflect government policy commitments. (23)

2.39. It is readily possible to use this detailed information to identify those authorities supporting good practice and those failing to do so and to identify details the types of provision made by them. (23)

2.40. There is little evidence of the Scottish Government or local authorities using this information to monitor and improve provision of pre-school services. (22, 23)

2.41. There is evidence that the Scottish Government and local authorities have not carried out their stated intent to monitor and improve these services. (22, 23, 24)

2.42. It is important to avoid the risk that qualifications for the pre-service workforce at any level become based on competence models which prevent professional reflection. (25)

2.43. It is important to ensure that work place based learning ensures professional reflection. (25)

2.44. It is important to ensure that all recognition and accreditation of prior learning (including informal and non-formal learning) is rigorous. (25)

2.45. There is little evidence that the levels of qualification for those entering child care employment are better than in the past. (26)

2.46. It is difficult to avoid the conclusion that Scottish Government targets to improve the qualifications of staff, other than teachers, in the pre-school sector are aspirational rather than realistic. (26)

2.47. Employers should ensure that they meet the requirement of SSSC to support learning on the part of their employees. (27)

2.48. Policy and practice are at risk of focusing less on the rights of the child than on economic policy. (4, 28)

2.49. It is important to avoid any risks that this funding model results in incoherence in provision. (28)

2.50. This funding model is associated with and dependent on the employment of low paid staff, especially but not only within the private or partnership sector. (28, 29)

2.51. The dependence on low paid staff leads to the employment of considerable numbers of less well qualified staff, especially but not only, in the private partnership sector.(28, 29)

2.52. The use of this funding model and consequent low pay is likely to be associated with continuing acceptance of roles for staff in the pre-school sector which can be described a substitute mother or technician. (4, 29)

8

2.53. Local authorities can choose to ensure that all their employees are paid a living wage. (29)

2.54. Local authorities can seek to use their procurement policies to require those establishments which they commission to provide services to provide minimum conditions of service and pay for staff employed by them. (29)

2.55. The Scottish Government and local authorities have it in their power to negotiate and agree national conditions of service and levels of pay for staff employed in the pre-school sector. (29)

2.56. These bodies have it in their power to associate levels of qualifications with such conditions of service and thus to drive up standards. (29)

2.57. Most proposals for joint training of professions working with young children have been aspirational rather than practical. (25, 30, 31)

2.58. It is possible to consider appropriate means of supporting joint training among such professions provided due regard is made to practical and cost issues. (31)

2.59. Discussion on the role of the pedagogue has often been carried out in terms which ignore the realities of the roles played by teachers in Scotland and the realities of the curriculum, teaching and learning in Scotland’s schools. (32)

2.60. Discussion on the role of the pedagogue has often failed to recognise the extent of the split between well qualified and less well qualified staff. (32)

2.61. Discussion on the role of the pedagogue has often been conducted without consideration of the likely costs of providing qualifications. (32)

2.62. Little evidence has been brought forward to distinguish the role of the pedagogue from the role of the teacher as defined in the Standard for Full Registration. (32)

2.63. Discussion of the role of the pedagogue has tended to ignore the consequences for pay scales. (32)

2.64. A number of proposals for EIS action are made. (33)

9

3. Background

3.1. Within the UK nursery education for 3 to 5 year old children has historically formed one distinct strand of public provision for children below the age of compulsory education. The other strand, though a range of titles has been used, can be referred to as early years care. These two types of provision differed greatly in terms of functions, administrative structures and staff qualifications. Nursery schools and classes, run by local authority education departments, offered almost exclusively part-time education to 3 and 4 year olds for the duration of the school year; they were staffed by qualified teachers and by nursery nurses with a lower level of qualification; their ‘client’ was primarily the child. Day care centres (with various titles), run by local authority social work departments, offered part time or full time care to children from 0 to 5, often for 50 weeks a year; they were staffed by nursery nurses and similarly qualified staff; their ‘client’ was primarily the parent or carer. There were, however, some similarities. Both types of establishment were provided, funded and managed by the local authority. Neither was a universal service; service levels were determined by each authority. This public provision was supplemented by very limited private sector provision of care services and by childminding, usually informally arranged. This fundamental split between nursery education and day care continues to the present and has, indeed, in some ways at least, become deeper and more entrenched as a result of government policies.

3.2. This type of pattern is now unusual within Europe. A recent Eurydice report (Education, Audiovisual and Culture Executive Agency 2009) makes clear that, while in many other European countries there is a split between pre-school education and care, this is typically related to age so that provision for 0-3 year olds is different in type and aims from provision for 3-6 year olds. It is unusual to have a dual system operating within an age group as is the case for 3-5 year olds in Scotland.

3.3. Within the dual system in Scotland there was clear recognition of the important role of the teacher in nursery education through the requirement of the Schools (Scotland) Code (1956) that in nursery schools and classes there had to be a ratio of one teacher to twenty children. The long history of nursery education in Scotland, the comparatively large number of places provided in some urban areas, the existence of specific additional teaching qualifications in nursery education and this statutory requirement for the employment of qualified teachers in nursery schools and classes were important factors in extending and maintaining provision of nursery education. Wilkinson et al (1993) in research carried out for Strathclyde Region, as it sought to reconfigure pre-school provision in the late 1980’s and early 1990s, reported support for local authority nursery education with teacher input. A 1995 survey of parents, conducted by the Scottish Parent Teacher Council (SPTC), found a ‘satisfaction’ rate of 71% for whole day local authority provision and 64% for local authority part-day provision; in contrast the corresponding figures for private provision were 33% and 27%

3.4. Nursery education, however, in Scotland did not enjoy the fundamental statutory status afforded to primary and secondary education; provision always remained discretionary and dependent on local authority policy. Local authorities are required only to secure a place for all 3 and 4 year old children whose parents may wish this; they are not required to provide

10

themselves a place for all such children. This lack of status was exacerbated when the Scottish Executive in 2002 removed the statutory requirement to have teachers present in nursery education and thus ‘gave local authorities greater flexibility in deploying teachers in pre-school centres’ (HMIE 2007c cited in Adams 2008). A small number of local authorities quickly interpreted this, without challenge from the then administration, as permission to redeploy teachers out of direct work with children in nursery classes or schools into support roles within early years provision or indeed out of the sector and into teaching primary classes. Adams (2008) points out the consequences of this:

The resultant replacement of the teachers by nursery nurses … had some unwelcome side effects: Many establishments were left with no employees qualified to degree level; early years expertise was lost; and a number of nursery classes found themselves being nominally led by the primary head teacher, or depute, who knew little of nursery pedagogy. In these situations, the quality of nursery education became solely dependent on the practice of nursery nurses. (p198)

3.5. There is evidence that more education authorities are now proceeding down this road. In some cases they have used the fact that they have increased the number and/or qualifications of other staff as an excuse for reducing the number of teachers employed in pre-school provision.

3.6. Both Conservative and New Labour UK governments were committed to extending early years provision for several reasons: to provide child care which would allow parents (ie mothers) to participate in the labour market; to provide support for parents or families who were in some way vulnerable; to provide support for children who were vulnerable or whose life chances were threatened by disadvantage; to improve educational outcomes for all children. These aims are not necessarily mutually consistent. The weight accorded to any one rationale has varied from time to time and from context to context. However, there has often been an emphasis on getting parents into work on the grounds that this is the most effective route out of poverty. This has over the last two decades moved from facilitation to direction. It is significant that, in contrast to almost all other European countries where responsibility for pre-school provision is vested in one or both of ministries of education and of social welfare, in England the Department of Work and Pensions is formally involved in the planning of pre-school provision.

3.7. Given these diverse aims, it is perhaps not surprising that there has been considerable confusion in developing policy and practice. It is notable that this extension of provision has been built on the dual foundations of nursery education and day care and has, therefore, entrenched the chasm between these two sectors. On to this already existing dichotomy there has been added a new dichotomy between public provision and a greatly expanded private sector.

3.8. Recent extensions in pre-school provision have been marked by the following features:

a refusal to envisage the possibility of a universal public pre-school service

the consequent extensive use of the private sector as providers of pre-school services

11

an uneasy balance between commissioning private sector provision and the use of the market to supply services

a general refusal to fund universal provision, free to parents, regardless of the provider

a partial exception to this in the commitment to provide limited nursery education to all 3 and 4 year olds (15+ hours per week), free to parents

payment for all provision of education and care beyond this through fees charged to parents

use of the tax system to provide some means tested financial support to working parents to contribute towards the payment of these fees

the dependence on quality assurance systems which make use of centrally determined standards and external evaluation

considerable dependence on low paid, low qualified staff, especially within the private, partnership sector

reductions in the numbers of teachers working with children

limited moves to enhance the qualifications of staff (other than teachers) in pre-school provision

limited and piecemeal attempts to bring the two sectors (nursery education and day care) together.

3.9. While the details of policy and practice in Scotland have changed over 20 years there has been no fundamental challenge to the model established by the Conservatives and developed by New Labour. Aspects of policy related to financial support for parents lie largely with the UK government and outwith the control of the Scottish government. Policy and practice in Scotland (as elsewhere in the UK) remain clearly different in aim as well as in structure from that elsewhere in Europe as summed up in the Eurydice report (Education, Audiovisual and Culture Executive Agency 2009):

ECEC [Early childhood Education and Care] programmes for 3-6 year-olds exist in all European countries and at this level (ISCED 0), the mission to educate is clear and overrides the child-minding function related to parental employment. … [S]taff working at this level of education have a pedagogy-related training which combines practical work experience with theoretical classes intended to produce qualified teachers or general educators. To sum up, the pre-primary level (ISCED 0) is characterised by a consistency in staffing – across most of Europe it involves teachers working in educationally-oriented teams and leading the majority of activities for children. (p13)

4. Learning from international comparisons

4.1. It is worth considering these developments in the context of studies of international provision and, in so doing, to return to the specific nature of policy and provision in Scotland.

4.2. The Thomas Coram Research Institute of the Institute of Education of the University of London was commissioned by the Department for Education and Skills (DfES) to compare early years and childcare provision in 15 countries, including the UK (differences among countries within the UK are

12

recognised). This became the Early Years and Childcare International Evidence Project / October 2003. The outcomes of this have been published as a number of papers under that heading.

4.3. The project concludes that policy, practice and organisation of pre-school services in each country reflect deeply embedded economic, cultural, social and political factors. In addition to specific historical practices and structures, these include the social construction of childhood, the support that is afforded to working parents, and the extent to which services are seen as a universal entitlement or as support for specific groups.

4.4. Moss et al (2003a) identify three models of provision. Nordic welfare regimes emphasise entitlement in the context of welfare regimes oriented to universal services; liberal welfare regimes, typical of English speaking countries, emphasise targeted benefits, prioritise the market and limit government responsibility for general services; conservative welfare regimes (covering other European countries) generally provide good welfare protection to those with stable lifelong employment, though less for others.

4.5. The historical distinction between care and education which existed in many countries, at least until recently, was supported by an uncritical acceptance of theories of child development such as Piaget’s theory of developmental stages, which suggested that external influences, including teaching, had little impact on the processes of early development. Care was designed to serve the physical and emotional needs of very young children; education was designed to serve the intellectual needs of children as they grew somewhat older. However, the arguments of writers, such as Vygotsky, who recognise the role of others in supporting early learning, now supported by considerable research evidence on learning at the earliest stages, have resulted in the acknowledgement in many countries that education begins at birth and that separating education and care, in the ways that were previously accepted, is no longer defensible or sensible.

4.6. Although concerned directly with primary education, the Cambridge Primary Review argument that improved understandings of cognitive development should inform both policy and practice can be applied equally to pre-school provision. Key principles include the following:

learning is fundamentally a social activity that can be carefully and sensitively scaffolded and enhanced by adults from birth and throughout the primary years (Goswami, U & Bryant, P (2007), Howe, C & Mercer N (2007))

language development is fundamental to all learning so talk and collaborative activity and thinking about learning (metacognition) should be an intrinsic and integrated aspect of classroom life (Goswami, U & Bryant, P (2007), Howe, C & Mercer N (2007))

children are agents in making sense of their lives, taking action and shaping other people's understanding of their individuality and shared characteristics, so it is important to seek out children's views in terms of both in research and practice (Cambridge Primary Review (2007a))

4.7. The Review concluded that the practice in England of children leaving behind their active play based learning and embarking on a formal, subject-based curriculum at the age of four is not of value. Practice in the early

13

years of primary school should reflect teaching in early years provision. Cambridge Primary Review (2009) summarises this:

We know, thanks to research, what children need to flourish in their early years. They need the opportunity to build their social skills, their language and their confidence. They do this best through structured play and talk, interacting with each other and with interested and stimulating adults. The evidence is overwhelming that all children, but particularly those from disadvantaged homes, benefit from high-quality pre-school experiences. (p16)

4.8. The report published as OECD Directorate for Education (2004) also argues that the education of young children (here referred to as early childhood education and care – ECEC) and the education of those in the statutory sectors are marked by the same principles including:

the same learning goals at all levels of education but at different levels of complexity

a continuity of perspectives through ECEC and the school

children’s learning must be focussed on creating meaning

ECEC curricula should deal with play and learning and the relationship between them

ECEC programmes must be open and make room for children’s initiatives and experiences.

4.9. Moss (2000) notes, in contrast, a discourse in some pre-school policy which reflects a limited view of education usually associated with those who seek to narrow education to achieving limited targets and to reduce teachers’ responsibilities to the carrying out of others’ instructions.

4.10. While it may be that this language has become increasingly dominant in some UK government policy statements, it has not become the dominant discourse in Scotland. Adopting such approaches would remove (or at least reduce greatly) the possibilities of pre-school education supporting children in developing in the ways envisaged for them in Curriculum for Excellence.

4.11. Such approaches reduce the opportunities for pre-school provision to provide children with the experience of being members of real community of dialogue and reflection in which they can become responsible citizens and effective contributors. An insight into the risks afforded by marketisation to broader definitions of education and to a universal service promoting social cohesion is afforded by the 2010 edition of Children in Europe published by Children in Scotland. This publication argues the importance of a sense of place for young children’s development. Articles provide examples of children in pre-school establishments which serve local communities in countries across Europe being afforded opportunities to develop a confident sense of place in developing their identity. However, no examples were provided from the pre-five sector in the UK; this lack was made up by exemplars drawn from the publicly funded school sector (Coleman 2010, explicitly, and Meade & Fairfax-Cholmeley 2010, implicitly).

4.12. Marketisation generally lends itself to limiting approaches as it purports to demonstrate through simplistic measurements ‘value for money’. More generally, a focus on using pre-school provision to provide measurable economic benefits excludes the perspective of the child (Penn et al 2006).

14

4.13. Barron et al (2007) note that some discussions of pre-school provision depend on assumptions which are inconsistent with the recognition, based on the work of Vygotsky, that the learning of all children shares common features. One such is the view of the insufficient child or family as the legitimate or priority recipient of services; indeed these families are sometimes seen as a target for such provision – an interesting, indeed disturbing, quasi-military metaphor. Within this perspective, such children and families are defined as different from and deficient compared to some notional ‘normal’ child or family; neither are the status and value of these norms ever open to discussion or contested. Provision for them will (should) be different from the provision made for others; in fact, the evidence is quite clear that children benefit rather from universal provision based on common principles. It may reflect this historical view that, as Moss et al (2003b) note, in most countries responsibility for services has continued to be divided between education and welfare departments.

4.14. This view has, in the UK countries, been come to be associated with a discourse which stresses the need for improved parenting and the value of employment as the road out of poverty. These two discourses are not necessarily mutually consistent but together have tended to compromise the ideal of a universal service. All too often the individual parent or family is held responsible, indeed blamed, for the consequences and burdens of inequality which they bear, whether this is unemployment, poverty or ‘failure’ as parent.

4.15. Only Sweden, England and Scotland have placed administrative responsibility for all childcare, early years education and compulsory schooling within the single government department of education. However, making one department responsible for all services for young children does not necessarily lead to coherent policy formation. In Scotland within the Education and Lifelong Learning Directorate there remains a clear internal split between school services and services for children. Recent events in England have indicated the continuing tensions in childcare despite the enhanced responsibilities afforded to educational agencies for childcare. In contrast in Sweden the move to coherent administrative structures has been associated with a commitment to ensuring the quality and consistency of all early years provision through the staffing of all centres by qualified teachers.

4.16. Despite continuing divides in the administration of early years provision, countries are paying increasing attention to the continuity between early childhood services and school through developing curriculum frameworks which span pre-school and compulsory school provision. Even in those countries which maintain separate curricula for pre-school and school, common principles or concepts underpin these. This model of separate curricula based on common principles was that employed In Scotland, for a number of years. Curriculum for Excellence has now taken this forward through the development of one curriculum which covers the age range 3 to 18 years, within which the Early level covers both pre-school and early primary.

4.17. Mooney et al (2003) argue that definitions of quality depend on cultural values and understandings of childhood. They consider, however, that there is a general consensus among researchers that the following elements

15

are associated with positive outcomes for children, both short and long-term:

adequate investment

co-ordinated policy and regulatory framework

efficient and co-ordinated management systems

adequate levels of staff training and working conditions

pedagogical frameworks and other guidelines

regular system of monitoring

equity and diversity expressed in eligibility and staffing policies.

4.18. The research identifies two main approaches to regulation: the first is built on the establishment of centrally determined standards and the use of external evaluation to determine conformity to these; the second is based on trust in local responsibility and the professional quality of staff to assure quality. The former is more likely to be of use in systems where the private market predominates.

5. Workforce organisation

5.1. Moss, P (2006) argues that there are three interrelated structural dimensions of any early years workforce: organisation, material conditions, and composition. These are related to the roles afforded the workforce; these structural dimensions contribute to the construction of these roles and are reproduced as the roles are played out in the workplace. In this view three different models have underpinned the roles of the worker in pre-school provision – substitute mother, technician and researcher. The first of these can be associated with concepts of provision in which care for young children is seen to be a ‘natural’ occupation for women, an occupation which requires no training or education; the impact of this continues to be reflected in the highly gendered nature of employment in the pre-school sector and was actively promoted by some Conservative thinkers in the UK in the 1980s as they sought to extend pre-school provision at minimum cost through the recruitment of a ‘mum’s army’. The second of these models suggests that working with young children requires no more than low level skills to carry out the instructions of others. It has long been a feature of provision in the UK and continues to be promoted by those who see the rationale for pre-school provision and education as primarily economic. It is reflected in the widespread employment of staff with low levels of qualifications at low rates of pay, especially but not only in the private partnership sector. The last is that associated with occupations such as the teacher or the pedagogue and is clearly associated with higher quality outcomes for children.

5.2. Kremer (2006) supports these arguments both about the longevity and resilience of the models which underpin early years provision, even when society has changed, noting that:

Most European welfare states today have said farewell to the male breadwinner–female caretaker model. Still, child care policy has a different pace and shape in each country. ... In Denmark, a universal

16

child care provision was made possible because of the advocacy coalition of women with social pedagogues. They promoted the ideal of professional care. To combat the ideal of full-time motherhood, the Flemish Catholic women’s movement strived for subsidizing childminders -- the ideal of surrogate motherhood -- supported by the Christian Democratic Party. Both strategies led to comparatively high levels of child care provisions, but also to very different contents and shapes. (p261)

Kremer notes that the choice of roles and, consequently, the types of provision made available depend on political decisions.

5.3. Despite a rhetoric of integration and some moves towards more integrated administrative structures and responsibilities, policy makers have not necessarily taken effective action to move away from an organisation of the workforce which reflects these conceptual differences and the structural split between childcare and early education. The two issues are correlated. Workers in child care establishments are typically assimilated to the discourses of the substitute mother or the technician and are lower qualified and lower paid. Teachers are employed as professionals in pre-school education; however, many workers in this sector are not highly qualified or paid and can be perceived as technicians.

5.4. There has, however, in some countries been a tendency, sometimes a powerful tendency, to move towards the greater employment of professionally qualified staff. Developments in the UK have been much less clear in this direction and have tended to sustain traditional views and practices. Indeed there has been, as already noted, a drive to reduce the number of teachers employed in pre-school education. Some have argued that limited moves to enhance the status of early years practitioners in England have been marked by the use of narrow competence based models of qualification which result in technicians rather than reflective professional practitioners.

5.5. Oberhuemer (2005) considers that evidence indicates that split systems have lower standards of education and training in the private as opposed to the public sector and in the care as opposed to the education sector. The market model of childcare in particular generates highly differential systems of training, payment and employment conditions.

5.6. There have been a number of approaches to developing more integrated workforce structures. All Nordic states have an integrated workforce based on two groups of workers: one group qualified at higher education level, accounting for between 30 and 60 percent of all workers in early childhood services; and a second group of workers with a lower level of qualification. Both groups are employed in all centred-based services and with children under and over three. In Sweden and Norway the higher qualified worker is a teacher; in Denmark the higher qualified worker is a pedagogue.

5.7. Most of the other OECD countries that have sought to integrate early years services within one policy area have moved towards an occupation with a high level of qualification, working directly with children under and over three and in all centre-based settings. The introduction of such a framework in Ireland in 2002 provides an example of so doing in an environment which had afforded a wide range of disparate qualifications.

17

5.8. Moss (2000) (p23) recapitulated some of targets are contained in the EC Childcare Network (1996) report. The following seem particularly relevant:

all qualified staff employed in services should be paid at not less than a nationally or locally agreed wage rate, which for staff who are fully trained should be comparable to that of teachers

a minimum of 60% of staff working directly with children in collective settings should have a grant eligible basic training of at least three years at post-18 level, which incorporates both the theory and practice of pedagogy and child development

all staff in services (both collective and family day care) who are not trained to this level should have right of access to such training included on an in-service basis

all staff in services working with children (in both collective and family day care) should have the right to continuous in-service training

all staff whether in the public or private sector should have the right to trade union affiliation.

5.9. It is clear that, despite some statements of policy intentions, the countries of the UK largely remain exceptions to the tendencies noted above and fall well short of the aspirations expressed by the EC Childcare Network.

5.10. Kuisma & Sandberg (2008) pose the fundamental issue of how we are to value qualitative differences among staff in pre-school provision and ensure that all employees are regarded as of equal value in the working team, although having qualitatively different educations.

5.11. One area of development in Scotland and England is the exploration of various models of enhancing the qualifications of workers other than teachers through workbased learning and the recognition of prior learning. Simpson’s (2010) account of the development of early years practitioner (EYP) status in England suggests, however, that simply adding to the qualifications of underpaid and undervalued workers does not necessarily resolve the tensions that are the result of the fundamental dichotomies between education and care and between technician and reflective professional.

The experiences of EYPs in the study demonstrate there may be some way to go before EYPS is regarded as having parity of esteem with qualified teacher status (QTS) across early years settings. This appears to be a negative by-product of setting up EYPS without addressing the issue of the continuing split early years workforce. (p12)

5.12. Alexander (2002) argues that it is important that professional education moves beyond competence-based training which relies on the exhibition and performance of tasks that are claimed to provide evidence of underpinning knowledge. This study argues that this assumption is not logical in that performance and knowledge are based on different models of learning that cannot be simply equated. His study of practice in England argues that it seems likely that the student childcare workers studied were not learning to be reflective practitioners:

18

Instead of developing a coherent body of knowledge that enables them to work effectively with young children, they are developing a set of performance skills that enables them to merely imitate what they see in childcare settings. (p26)

5.13. Discussions with the Sector Skills Council responsible for Social Care, Children, Early Years and Young People's Workforces in the UK, as it developed the standards for support staff working with children in schools, made clear that it is possible to recognise in supportive ways the contributions that different groups of staff make to education while at the same time recognising the differences between these groups.

5.14. The Engineering Council UK is responsible for the UK Standard for Professional Engineering Competence (Engineering Council UK 2010). There are three standards presented in parallel:

Chartered Engineers who are characterised by their ability to develop appropriate solutions to engineering problems, using new or existing technologies, through innovation, creativity and change

Incorporated Engineers who are characterised by their ability to act as exponents of today’s technology through creativity and innovation

Engineering Technicians who are concerned with applying proven techniques and procedures to the solution of practical engineering problems.

Access to the standards for chartered and incorporated engineers is usually through appropriate degree level qualifications (SCQF level 10 or 11) or in the latter case by qualifications at SCQF levels 8 or 9; engineering technician can be accessed through SCQF level 6 qualifications. It may be worth considering whether this model of standards at different but parallel levels could be used to provide differentiation among professions in the pre-school sector.

6. Funding and philosophy

6.1. The philosophy of early years provision will be reflected in funding arrangements. Candappa et al (2003), surveying a range of countries, conclude that there are three main potential sources of funding for early years and childcare services: government at one level or another; parents; and employers. Nursery education is usually funded entirely by government, other early years services by two or more sources, but always including parents as contributors.

6.2. This study reports that comparative public expenditure on early childhood provision remains low in most English speaking countries including the UK. Public expenditure on early childhood services in Sweden and Denmark was in 2000 equivalent to about 2% of GDP, more than three times the level in the United Kingdom. This comparatively low investment in early years provision is consistent with each country’s tax and public service policies: in 2000, overall tax income in the three countries accounted for 54%, 49% and 37% of GDP respectively. More recent figures from Norway, published by Children in Scotland in 2007, paint a similar picture; these indicate that government expenditure on pre-school services in that country was 1.7% of GDP while the UK figure at that time was 0.47%. It is worth noting that at

19

that same time 9% of children and young people (0-15) in Norway lived in poverty; 21% of this cohort in Scotland lived in poverty.

6.3. Public funding in most of the study countries is long-term and uses supply side mechanisms. English speaking countries tend to rely on demand side mechanisms like tax credits in which individual children are the funding unit. Partnership providers are always at risk of losing ‘custom’ and therefore income. The implications for stability and long term planning which arise from this difference are evident. The number of early years establishments closing each year both in England and in Scotland is considerable.

6.4. Candappa et al (2003) report a key issue identified by Verry (2000):

We might also consider the issue of market imperfections and how this relates to ECEC financing within the market-forces model. Verry (2000) points out that parental investments in ECEC for their children are likely to be constrained by family incomes and savings, and the cost of resources invested in children therefore varies across families. He states: ‘this implies that even if parents took the full range of costs and benefits into account their investments would not, in aggregate, be efficient’ (p 115). On these grounds he argues the case for government intervention to secure more efficient levels and patterns of investment in children, through direct subsidies, tax credits and/or childcare vouchers. (p12-13)

6.5. Candappa et al (2003) develop this point:

Verry further argues that if early childhood education and care provides greater benefits to society as a whole than to the households demanding it, this would ‘provide a rationale for government intervention in order to equate social rather than private costs and benefits at the margin (p115)’. (p13)

6.6. The commitment to comparatively low levels of taxation noted above has continued. Recent UK New Labour governments made clear their distaste for enhanced levels of investment in public services if this required higher direct taxation or indeed imperilled their drive to lower direct taxes; this led to a range of means of making use of private finance to support investment in these services. The current Conservative - Liberal Democrat coalition is using the rationale of an economic and financial crisis to cut the public sector with what can only be described as gleeful enthusiasm. Equally importantly, New Labour demonstrated a lack of commitment to the idea of providing public services which would promote social justice for all as opposed to social mobility for the few. The current coalition government in Westminster is adopting policies which will undoubtedly promote inequality.

6.7. While governments in Scotland, Labour - Liberal Democrat coalition and SNP minority, have shown little enthusiasm to go further down the roads followed in London, they have shown little sign of wishing to adopt policies in this field which diverge greatly from the status quo inherited in 1999 at devolution. There is a risk that policy formation will be affected by drift from the larger jurisdiction. It is evident in any case that room for radical policy development will be severely constrained by the economic and public finance policies adopted by the UK government.

20

7. Education for all 3-18

7.1. Within the current dichotomous model, the importance of recognising the continuity of education from age 3 onwards is formally recognised in Scottish education in a number of ways.

7.2. The Standard for Initial Teacher Education (required of teachers as they leave teacher education) (GTCS & QAA 2007) and the Standard for Full Registration (which must be achieved at the end of probation) (GTCS 2006) are as fully applicable to teachers in pre-five services as they are to primary and secondary teachers. All teachers must be registered with the General Teaching Council for Scotland as either secondary or primary teachers: all primary teachers are fully qualified to teach from age 3 to 11 across the nursery primary boundary.

7.3. As noted below, the Government is promoting a specialism in early years within teacher qualifications in the University of Stirling; the specialism covers the age range 3 to 8, again clearly across the nursery primary boundary. It is notable that additional teaching qualifications with a specific focus on the younger age range also cover learning and teaching in both pre five centres and the early years of primary education.

7.4. There is different quality assurance documentation for the pre-school sector – The Child at the Centre (HMIE 2007a) – and for the statutory provision of education – How Good is our School? (HMIE 2007b). This might be seen as suggesting that there is a clear distinction between the two sectors. However, the documents are based on common principles and presented in parallel formats. The existence of two sets of documentation is the consequence of the former being concerned with all forms of pre-school provision, not only schools, and having to address the needs of two different regulatory bodies in this sector.

7.5. Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Education has common responsibilities in both the nursery sector and the statutory sectors of education. Their website and publications illustrate this and common themes consequent on these.

7.6. Through these structures the clear relationship between education at all stages and the role of the teacher in all sectors is clearly recognised and established. There is extensive evidence, considered below, from research within the UK which sustains the argument that teachers matter to the learning of young children.

8. Curriculum for Excellence

8.1. Curricular policy in Scotland clearly recognises the continuity of learning for all children and young people and recognises the crucial role that high quality teaching plays in ensuring achievement for all learners. Curriculum for Excellence is a curricular framework for all children and young people aged 3 to 18 which lies at the heart of education for all children and young people aged 3-18 in Scotland. This is true in terms of content, pedagogy, assessment and curriculum architecture. All political parties have affirmed their general support for this framework; none in the policy field appears to have suggested any return to models based on separate curricular specifications for different sectors.

21

8.2. Curriculum for Excellence implies a shift from considering education not only in terms of content, ‘what we teach’, but also in terms of pedagogy, ‘how we learn’. It is built on a model of learning in which children and young people are active agents in being and becoming successful learners, confident individuals, responsible citizens and effective contributors to society.

8.3. Curriculum for Excellence extends the contexts and settings for learning beyond the school or college and extends the concept of achievement beyond the traditional limits of attainment. It recognises that children and young people learn in the classroom, through interdisciplinary working within school, through the life and ethos of the school and through opportunities for personal achievement. They learn also in a wide range of contexts outwith the school, including the contexts provided by their local community. Policy and practice, therefore, recognise that the definition of learning must be extended beyond attainment in the traditional sense to a much wider range of achievement. It is the role of the school to ensure that this learning is integrated. The evidence of the capabilities of teachers in early years provision in so doing is now well-established (see below).

8.4. The seven curricular principles which underpin Curriculum for Excellence are common to all stages of education from 3 to 18. The eight curricular areas which are fundamental to the organisation of learning are common to all stages of education from 3 to 18. The five levels through which learners progress until they enter the senior phase cannot be equated with the sectors of schooling. Indeed, the common nature of education for pre-five children and for primary aged children is clearly exemplified in the expectation that the Early Level will cover children aged 3 through to 6. The statements of experiences and outcomes for each curricular area at this level are, therefore, intended to cover pupil in both early years establishments and in primary 1.

8.5. Building the Curriculum 2: Active learning in the early years (Scottish Executive 2007) is designed to support teachers in nursery schools and the early primary years, stressing the importance of active learning for all young children and the continuity between nursery and primary education. The experiences and outcomes for each curricular area provide and foster opportunities for the sorts of pupil and teacher activities described as effective in the Effective Provision of Pre-School Education Project (see below).

8.6. While Curriculum for Excellence publications in the series Building the Curriculum are carefully addressed to all those who work with children and young people in educational settings, it is evident from these documents that the actions proposed for staff are those which have traditionally been associated with teachers and teaching. These actions are built on the foundations of current practice in schools, practice developed and sustained by teachers.

8.7. Curriculum for Excellence is not a free-standing development in Scottish education. The principles which underpin this development also underpin other policy developments in education. In particular, A Teaching Profession for the 21st Century (TP21) is founded on the recognition that the reprofessionalisation of teachers is central to the development of an education service which will meet the needs of all learners.

22

9. The Effective Provision of Pre-School Education Project

9.1. The Effective Provision of Pre-School Education (EPPE) Project in England and Wales was commissioned by the then Department for Education and Schools in Westminster (DfES) and was carried out by a team of researchers led by senior staff from the Institute of Education of the University of London, Birkbeck College, the University of Oxford and the University of Nottingham. The project explored the impact of a number of factors, including early years provision, on children’s development in general and education in particular as children moved through their early years and into Key Stage 1. This research was later extended to follow up the consequences of these factors as the children moved through Key Stage 2 of primary schooling.

9.2. More than 2800 children in a range of local authorities across England were assessed at the start of pre-school (around the age of 3) and were then followed up when they entered school along with a further 300+ children with no pre-school experience. All children were then followed for a further six years until the end of Key Stage 2 (age 11 years). Children were recruited from the major types of early years settings existing in England at the start of the study (1997): integrated centres; public nursery schools, nursery classes, local authority day nurseries, private day nurseries and playgroups.

9.3. While this research was conducted in England, its findings can be extrapolated to Scotland with some confidence. Despite differences in details, policy on provision for young children was similar in both jurisdictions; a common history and similar funding structures resulted in types of provision which were generally similar; the differences among staff qualifications were similar in type in all jurisdictions within the UK.

9.4. The final report of the first phase of the project is published as Sylva et al (2004). The final report of the extension phase of the project is published as Sylva et al (2008). There are several supplementary reports from the same team, including Sammons et al (2008a) and (2008b).

9.5. The conclusions of these reports, with regard to outcomes for children as they were about to enter primary school, can be summarised as:

a. Pre-school experience, compared to none, enhances children’s development.

b. An earlier start to pre-school experience is related to better intellectual development and improved independence, concentration and sociability.

c. Full time attendance leads to no better gains for children than part-time provision.

d. Disadvantaged children in particular can benefit significantly from good quality pre-school experiences, especially if they attend centres that cater for a mixture of children from different social backgrounds.

e. ‘More’ and ‘less’ effective centres, in terms of the promotion of positive child outcomes, can be found in all types of provision; overall, however, children made better progress (cognitive and social/behavioural) in fully integrated centres and nursery schools.

f. The quality of pre-school centres is directly related to better intellectual/cognitive and social/behavioural development in children.

23

g. Settings which have staff with higher qualifications, especially with a good proportion of trained teachers on the staff, show higher quality and their children make more progress.

h. Effective pedagogy includes interaction traditionally associated with the term ‘teaching’, the provision of instructive learning environments and ‘sustained shared thinking’ to extend children’s learning in which two or more individuals ‘work together’ in an intellectual way to solve a problem, clarify a concept, evaluate activities, extend a narrative etc.

i. Trained teachers were most effective in their interactions with children, using the most ‘sustained shared thinking’ interactions.

j. Staff qualified at degree level, almost all of whom were teachers, were more likely to encourage the development of language and mathematics and to encourage children to take part in activities which provided cognitive challenge.

k. Having qualified trained teachers working with children in pre-school settings (for a substantial proportion of time, and most importantly as the pedagogical leader) had the greatest impact on quality, and was linked specifically with better outcomes in pre-reading and social development.

l. Where there were trained teachers there was a stronger educational emphasis, with the teachers playing a lead role in curriculum planning and offering positive pedagogical role modelling to less well-qualified staff. Less qualified staff who worked alongside these highly qualified staff developed their skills in so doing compared with their colleagues who did not enjoy such opportunities.

m. However this collaboration required more than simply the addition of just one teacher or a peripatetic teacher to a more traditional local authority day care setting. Settings integrating care and education had high scores only when there was a good balance between ‘care’ and ‘education’ in terms of staff qualifications. The settings that viewed cognitive and social development as complementary seemed to achieve the best outcomes.

n. Different groups of children have different needs. Results imply that specialised support in pre-schools, especially for language and pre-reading skills, can benefit children from disadvantaged backgrounds and those for whom English was an additional language.

9.6. The researchers concluded that practitioners’ knowledge and understanding of the curriculum were vital. A good grasp of the appropriate ‘pedagogical content knowledge’ is just as important in the early years as at any stage of education. Moreover they found, crucially, that the most ‘effective’ educators also demonstrated knowledge of which content was most relevant to the needs of individual children. This required a deep understanding of child development.

10. Why nursery education and nursery teachers matter to older children: EPPE

10.1. The beneficial effects of pre-school remained evident throughout Key Stage 1 although the effects for some outcomes were not as strong as they had

24

been at school entry, probably because of the increasingly powerful influence of the primary school on children’s development. Indeed, the benefits of pre-school education largely persisted through to the end of Key Stage 2 (ie the end of primary school). Attendance at pre-school remained beneficial for academic outcomes, social/behavioural outcomes and pupils’ self-perceptions. The benefits of pre-school were greater for boys, for pupils with special educational needs, and for pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds.

10.2. The quality of the pre-school predicted pupils’ developmental outcomes. Children who did not attend pre-school and those who attended low quality pre-school showed a range of poorer outcomes at age 11. Attainment in English and mathematics at the final stage of primary education was affected by whether the child had attended early years provision and the type of provision attended. Attendance at nursery school was associated with the highest positive effects.

10.3. The quality of the pre-school attended continued to have an impact on different aspects of social and behavioural development at the end of Year 6. Attending a high quality (even a medium quality) pre-school had a lasting effect in promoting or sustaining better outcomes. It appears that attending high quality pre-school provision also positively affected pupils’ attitudes throughout primary schooling in that perceptions of ‘enjoyment of school’ were higher for pupils who had attended such provision.

10.4. Disadvantaged children and boys in particular benefited significantly from good quality pre-school experiences. If disadvantaged children attended centres that included children from mixed social backgrounds they made more progress than if they attended centres serving predominantly disadvantaged children. Children identified as ‘at risk’ of learning or behavioural difficulties were helped by pre-school, with integrated settings and nursery schools being particularly beneficial in providing a better start to primary school.

10.5. The team is continuing this longitudinal study in secondary schooling but results of this have not yet been published.

11. The Millennium Cohort Study

11.1. Another major research exercise is reported by Mathers et al (2007). This followed the EPPE work and sought to investigate changes in early years provision in the intervening period.

11.2. The researchers found that there was still considerable variation in the quality of provision offered by the sample settings. The maintained settings provided the highest quality provision overall, particularly with regard to the ‘learning’ aspects of provision. Voluntary providers had, however, made significant improvements compared to the earlier sample. There was evidence to confirm the EPPE findings that while all early childhood settings are good at providing nurturing environments for children, some are less successful at offering provision which stimulates children’s cognitive development.

11.3. The most important influences on overall quality of provision for 3 and 4 year old children were (in rank order):

25

• sector (maintained sector = higher quality);

• group size (larger groups = higher quality);

• staff qualifications (higher qualifications = higher quality);

• Children’s Centre status (Children’s Centres = higher quality);

• age range/s of children catered for (older children = higher quality);

• staff-child ratios (fewer children per adult = higher quality);

• links with Sure Start Local Programmes/ health services (SSLPs/health links = lower quality);

centre size (smaller centres = higher quality).

It should be noted for clarification that group size refers to the organisation of groups within the teaching room; it does not imply a poor adult-child ratio.

11.4. Not all of these are relevant to the Scottish context but those that are provide clear pointers to high quality provision, pointers consistent with the messages from international surveys.

12. EPPI Review

12.1. Penn et al (2004) report the findings of a review of research into the impact of integrated provision in the early years on children and on their parents.

12.2. All the studies reviewed broadly found that the impact of integrated care and education was beneficial for children and led to improved cognitive and socio-emotional outcomes. Children from multi-risk families showed significant gains. One well-designed study suggested that the impact of integrated care and education was amplified by home visiting family support, but conversely that home-visiting family support made no difference unless integrated care and education was also provided. The authors conclude that the relation between education and care merits further investigation – for example, pedagogical styles, training, curriculum.

12.3. Eurydice (Education, Audiovisual and Culture Executive Agency 2009) makes a similar if more general point in summing up a range of research:

The ‘winning formula’ consists in combining care and education of the young child in a formal setting with support for parents. Research still needs to identify the precise nature and characteristics of the parental support which should be provided in European countries. (p142)

12.4. Penn et al (2004) raise the more general issue of the relation between the current policy emphasis on mothers, especially single mothers, returning to the labour market and the type of provision made for young children.

13. Other research evidence

13.1. A summary provided in Sylva et al (2004) (p14) provides consistent evidence from a range of studies:

• Short-term, positive effects of pre-school education have been shown conclusively in the US, Sweden, Norway, Germany, Canada, Northern Ireland and New Zealand (See Melhuish, 2004a)

26

• The effects of greater staff training and qualifications have been shown in the US (Peisner-Feinberg and Burchinal 1997) and in Northern Ireland (Melhuish et al 2000)

• The contribution of quality to children’s developmental progress has been shown in many studies, often using the ECERS observational scale, the scale used by EPPE (Melhuish 2004a and b)

13.2. The OECD Directorate for Education (2004) report argues that the quality of staff is the paramount factor to ensuring high quality provision in early years education and care and identifies the crucial importance of qualified teachers in contributing to this:

The quality of the programme and the competence of the staff are two closely linked dimensions. … in the curricula presented, they all have well educated staff, whether through recruitment level, initial training or extended in-service training. … Staff meeting children everyday must have high standards of training, since it is the daily interactions between the adult and the child that make the difference in children’s well-being and learning (Johansson, 2003). There should not be any difference in level of competence between teachers working in ECEC or compulsory school … the teachers leading, developing and assuring the quality of ECEC ought to have a university degree. (emphasis added) (p28)

13.3. Magnuson et al (2007) note a number of US studies which provide evidence of the long term value of enrolment in pre-school education programmes. While these findings seem particularly well evidenced and marked for disadvantaged children placed in high-profile, well-resourced programmes, they also seem to apply to all children in more typical provision. The authors then carried out a longitudinal study, the focus of which was to investigate the circumstances in which such advantage was sustained or not. The study provided further evidence that children who attended pre-school enter primary schools with higher levels of academic skills than their peers who experienced other types of child care. Children who had not attended pre-school could only catch up if they were placed in small primary classes and classes providing high levels of reading instruction. This provides further evidence of the close relationship between pre-school educational experiences and educational experience in the early years of primary school.

13.4. The Early Years and Childcare International Evidence Project adds to the body of research identifying qualifications and training as a key indicator of quality. The findings reported in Cameron et al (2003) are consistent with those arising from the EPPE fieldwork. Staff qualifications and training, staff to child ratios and group size are key quality variables because they are associated with positive, sensitive interactions between staff and child, which in turn are associated with positive child outcomes. These three key variables are described as the ‘iron triangle’.

13.5. Results from some research carried out into the effects of the employment of lower qualified classroom assistants in primary and secondary schools are consistent with these findings concerning the pre-school sector. The Tennessee STAR research on the impact of class sizes on attainment included ‘regular’ classes (ie classes with larger number of pupils) as one of the groups against which smaller classes were compared; the research

27

model also included regular classes with a classroom auxiliary present. Interestingly, it was only class size which made a difference to pupils’ attainment; there was little impact through the deployment of classroom auxiliary staff. It may be argued that the relevance of these findings to Scotland today is limited as this research was carried out some time ago in another education system.

13.6. However the recent Deployment and Impact of Support Staff (DISS) project in England, as reported by Webster 2010, concluded that

pupils who received the most support from teaching assistants (TAs) made less progress in English, mathematics and science than similar pupils who received less support from TAs (even when controlling for the factors which that can affect progress and the allocation of TA support, such as prior attainment and special educational needs).

The authors of the reported research are clear that the TAs were not at fault but rather that systemic structural factors were central to these findings. TAs were employed in such a way as to separate pupils from the curriculum and teachers; they were encouraged to concentrate on getting pupils to finish tasks rather than on ensuring learning had taken place; there were limited opportunities for teachers and TAs to communicate about their work. Evidence considered later would suggest that some at least of these factors may sometimes apply in pre-school services in Scotland.

14. HMIE: The Key Role of Staff in Providing Quality Pre-School Education

14.1. Findings from HMIE in Scotland are consonant with these findings from academic research. The report The Key Role of Staff in Providing Quality Pre-School Education (HMIE 2007c) is based on inspection evidence gathered in 2003-2006.

14.2. The context was the removal of the requirements of the Schools (Scotland) Code for the provision of teachers in nursery education; the purpose is set by the statement (p2):

The new guidance [on the roles of teachers in pre-school education] aimed to:

identify and affirm the value of the contribution trained teachers made to the quality of experiences for children in pre-school education;

set the involvement of teachers alongside the contributions of other staff and underline the importance of team working;

identify ways in which teachers added value to the early education experience, both within and outwith the pre-school settings;

identify key factors which made for successful integration of teachers within staff teams; and

encourage authorities to consider carefully future staffing arrangements which reflected the interrelationships between care and education, and the need to provide flexible opportunities for the use of staff skills.

28

14.3. The Foreword to this document (p1) confirms research findings noted above:

Where the quality is high, … children have increased chances of success in their primary education and reduced chances of problems with attainment, relationships and behaviour. Moreover, the benefits are experienced across the range of social advantage and disadvantage and persist even in the face of weaknesses in the quality of their experience in primary school.

14.4. Evidence is presented by type of centre. Unfortunately, education authority nursery schools and family centres are clustered into one group which may make for some difficulties in discussing the distinctive contribution of nursery schools; however the fact that there were at this time proportionately many more nursery schools than family centres does allow for some confidence in making statements about nursery school provision. Education authority nursery classes do not form a discrete category but are grouped with nursery classes in independent schools, all of which seem likely to have a qualified teacher.

14.5. A number of statistical conclusions are evident, all of which appear to be consistent with the EPPE findings. Staff child interaction, meeting children’s needs, support for children with additional support needs and leadership are all assessed as better in centres with a teacher than in those without a teacher. Further, staff child interaction, meeting children’s needs, support for children with additional support needs and leadership are also all assessed as better in public than in private or voluntary centres.

14.6. The Report goes on to recognise the roles played by teachers; again the findings are consonant with those reported by EPPE:

Teachers played an important part in equipping their colleagues who were not teachers with the right knowledge, skills and training to meet the changing and increasing demands required of a high-quality, pre-school education. Teachers demonstrated very effective skills in coordinating partnership working. (p16)

14.7. The Report recognises that support from teachers has a significant role to play in professional development for staff who are not teachers:

Staff in these centres [where no teacher was employed] had often undertaken higher level qualifications and appropriate early years training. … Staff often worked closely with visiting teachers, sharing knowledge and experience. (p16)

Within local authority and independent school nursery classes, qualified teachers operated often as the day-to-day managers with responsibility for the nursery. In these circumstances, teachers as team leaders regarded nursery nurses as valued colleagues and they worked well together. (p16)

14.8. The Report recognises that there are changing patterns of deployment of teachers in this sector. HMIE continue to recognise from the evidence of their inspections the important role of teachers and urge local authorities:

to ensure that, when they review the role and remit of teachers in early education, they make appropriate and effective use of the particular skills and expertise of teachers to ensure that they maintain the consistently

29

high standard of provision and support for pre-school children’s development and progress. (p19)

15. The role of the peripatetic teacher

15.1. The EPPE study identifies the important role of the teacher and the difficulties in exercising this role when it is seen as an ‘add-on’ to provision which is staffed by colleagues who are not teachers.

15.2. Garrick and Morgan (2009) identify some of the limitations of the role of the peripatetic teacher. In contrast to a ministerial statement noted below, this study noted the consequences of the situation when the expertise of teachers was spread thinly. Each teacher studied worked in at least eight partnership centres but their expertise was spread even more thinly than this figure would suggest because some centres had three or more staff teams working with different age groups. Although this was a small study, the evidence was clear that teachers deployed in this way found difficulties in sustaining the professional development of their colleagues in these centres.

15.3. It was notable that teachers were better able to assess the quality of provision in the centres in which they worked on a peripatetic basis than the (non-teacher) managers of these centres who tended to overestimate the quality of provision: the teachers’ ratings of key aspects of practice were more closely matched to the scores derived from the use of standardised instruments than those of managers.