Nansa Doumbia: Matriarch, Artist and Guardian of Tradition

Transcript of Nansa Doumbia: Matriarch, Artist and Guardian of Tradition

NANSA DOUMBIA: MATRIARCH, ARTIST, AND GUARDIAN OF TRADITION

Barbara E. Frank35

Nansa Doumbia of Kangaba is a remarkable woman. She is remarkable for the extent to which her life exemplifies the stereotype of the female blacksmith-potter (numumuso) in Mande society. In this essay, I provide a sketch of her life and her various roles as matriarch, as artist and as guardian of tradition. I com-pare aspects of her biography to those of other numumusow to explore just how stereotypical her life has been, and by implication, just how accurate the stere-otype.36 I present this story mindful of many studies in the scholarly literature promising to give voice to African women, the subtext of which has been that by telling their stories, commonly held misconceptions will be overturned and women will be thus empowered. These are often the stories of exceptional women who as queens, market women, slaves, or prostitutes, challenge the status quo of male-dominated social systems.37 At the heart of these discussions are questions of agency and the extent to which women have the ability to take actions and to make choices about their future given the powerful economic, political and social contexts within which they live. The story presented here,

35 I offer this essay as a tribute to David and to our collaboration on the edited volume, Status and Identity in West Africa. Nyamakalaw of Mande (1995). Our intention at the time was to pro-vide a sense of the complexity of artist identities within Mande society as a challenge to superficial understandings and stereotypes based on colonial models. It was, in part, the process of putting together that volume that made me aware of just how little attention scholars had given to issues of gender and the status of nyamakalaw women apart from their husbands. This awareness in-formed and encouraged my own research on Bamana and Maninka potters, and Nansa Doumbia figured prominently in that research. (It is her image that appears on the paperback edition of Status and Identity). I use the first person style of writing in this essay (even though I imagine David would not approve) because my relationship with Nansa and my efforts to understand what it meant to be a numumuso are very much part of the story.

36 The stories I present here were not offered up in a single interview session with the intent of recording Nansa’s life history. Rather, these were anecdotes and concerns that surfaced in our conversations during my research on Mande pottery traditions. Most of these stories were trans-lated at the time by my field assistant, Mariam Tangare. An early version of this paper was pre-sented on a panel I organized for the 2002 African Studies Meetings in Washington, D.C. entitled ‘Artist Biographies: With or Against the Grain’. As discussant for the panel, Mary Jo Arnoldi of-fered useful critique. I would like to thank Catherine Bernard and Lisa Aronson for comments on various drafts of this essay.

37 See especially Hay 1988 who in her review of historical perspectives published between 1971 and 1986 noted a distinct shift in emphases from queens, to prostitutes and slaves. See also Romero 1988, Wright 1993, Grosz-Ngaté and Kokole 1997, Berger and White 1999, and Hodgson and McCurdy 1996, 2001, among others.

NANSA DOUMBIA: MATRIARCH, ARTIST, AND GUARDIAN OF TRADITION 75

however, is that of a woman who, I suggest, has chosen not to subvert the con-straints of Mande social mores, but rather to excel within their contours. I argue that there is agency in the decisions she has made in her life, and that this is apparent when aspects of her life are compared to those of other women of her generation who share the identity and social position of being a numumuso.

In the spring of 1999, I returned to Mali after an absence of seven years. In that time, I had produced a book based on research among Mande potters and leatherworkers (Frank 1998). I took copies to several of the men and women I had come to know during my research, and their reactions were quite telling in different ways. Certainly, all were pleased to see themselves and those they knew in the photographs, but they were often just as curious about images of others. Bamana potters Seban Fane and Sitan Ballo of Kunògò, just outside Kolokani, carefully paged through the pottery sections. When we looked at a picture of one woman making a pot, I identified her by name as Assa Couli-baly of Banamba. I heard their tongues click. I began to point to similarities and differences in their respective tools and techniques. There were more clicks of the tongue. The next time an image of Assa appeared, Seban immediately said to the others around us: ‘Assa … that’s Assa Coulibaly of Banamba.’

This struck a chord with me. While the focus of much of my research was one of mapping tools, techniques and styles in order to document and define the nature of an artistic tradition, these women were more interested in the named individuals who grace the photographs in the book. Perhaps this should have come as no surprise. However, it has led me to reflect on the extent to which the scholarly literature tends to suppress the individual in order to iden-tify the cultural norm. For example, it is common practice in writing ethnogra-phies to use pseudonyms to protect the identity of informants. Indeed, there are certain sensitive situations where names should not be given to preserve confi-dentiality.38 However, in my experience, there is very little that is either private or forgotten in Malian villages when it comes to foreigners. Certainly, no stranger can slip unnoticed from one compound to the next. In Kangaba, every one in the blacksmith-potter quarter knew exactly with whom I was conduct-ing an interview, having lunch, whom I was filming, and whose pots I had purchased. Because so much of my time was spent with Nansa Doumbia, to those who did not know me well, I was known as Nansa’s tubabumuso (her ‘foreigner/white woman’). Thus, for many, I was not particularly distinguish-able from the Peace Corps volunteers, foreign aid workers, or tourists who appeared on occasion, cameras or notebooks in hand. However, most of the women in the blacksmith quarter referred to me by my Malian name, Fatu-mata Silla, a name given to me by one of the leatherworkers I interviewed

38 Szklut and Reed 1991 examine the pros and cons of using pseudonyms for communities and ultimately conclude that anonymity is inherently no more or less ethical than identification, either way there are costs.

BARBARA E. FRANK76

during my first research project in Mali. There were many jokes about Silla leatherworkers ‘begging’ from Kante blacksmiths and Kante blacksmiths be-holden to Silla leatherworkers. It was important to them that I understood something of the significance of family names and social position in Mande culture. But it was also important to them that I had such a name, fictive kin-ship though it was.

Since my return from that trip, I have been thinking about how rich my ex-perience of these women has been, much richer than that conveyed in the aca-demic construction represented by the book. How might I share these more personal experiences and in the process, challenge the abstract stereotypes pre-sented in my own and other academic writing? If one turns to the literature on African women, one finds a variety of texts analyzing the complexity of gender relations in Africa and the position of women within what are presumed to be male dominated social structures.39 The most common approach is a synthetic one, in which certain ideas or conclusions about the status of women are drawn from interactions and conversations with a variety of women. For example, in Veiled Sentiments (1986), Lila Abu-Lughod skillfully stitches together the mul-tiple voices of her informants to produce a richly textured and layered ethno-graphic portrait of Bedouin oral artistry. However, on reflection, she found the demands of this format to be a bit too coherent, such that individual voices were subsumed into the larger narrative. In her second book, Writing Women’s Worlds (1993), Abu-Lughod took a different approach by orchestrating the sto-ries of particular women around, or rather against, a series of dominant themes in anthropological discourse.40 She thus simultaneously challenged anthropo-logical notions of culture, feminist interpretations of non-western gender rela-tions, and common perceptions of Muslim Arab society. Her agenda was to ‘write against culture’, or against the way culture has been reified in Western thought, by allowing the multiple voices of her informants disrupt the anthro-pological tropes.41

Another approach is that of compiling an individual life history, in which one focuses on the life of a particular woman and attempts to offer something of the complexity of women’s lives through the prism of one life.42 Thus, for

39 The literature on African women and gender relations has expanded exponentially in the last three decades. Early classics in the field include Hafkin and Bay 1976; Bay 1982; Robertson and Klein 1983; Hay and Stichter 1984; Roberston and Berger 1986, among others.

40 These themes - patrilineality, polygyny, reproduction, patrilateral parallel-cousin marriage, and honor and shame - provide the focus for each chapter of stories about particular women.

41 See Grosz-Ngaté 1997 for a succinct review of debates in the 1990’s concerning the con-struction of ‘culture’ as an epistemologically distinct entity.

42 Perhaps the most famous is Mary Smith’s classic biography Baba of Karo (1954), see also Wright 1993. See Geiger 1986 for a critical response to those who discount the validity and useful-ness of the life history approach especially with regard to the role of women in history and society. She argues that questioning the representativeness of an individual life presumes the existence of an abstract standard of objectivity and normativity, and the problem is that these standards too often fail to include the viewpoints of women.

NANSA DOUMBIA: MATRIARCH, ARTIST, AND GUARDIAN OF TRADITION 77

example, in Life Histories of African Women Romero (1988) presents the sto-ries of seven extraordinary women who moved in a variety of circles, from the famous Asante royal woman Akyaawa Yikwan, who was the principle negotia-tor of an important treaty with the British in the 19th century (Wilks 1988), to the story of the slave woman Mama Khadija (Romero 1988), who had no less than seven husbands by her own ill-fated choices.43 This approach challenges stereotypes by revealing the variety of contexts and conditions within which women operate as well as by highlighting how particular women responded to particular circumstances.

With these models in mind, I turn to some of the stories Nansa Doumbia shared with me. I suggest that they reveal something of her character, of the opportunities and challenges with which she was presented, and of her ability to make choices to affect the course of her life.

Nansa as matriarchNansa Doumbia was the first born of her father, Boundiali Doumbia, and his first wife, Bariba Kante. It was some time before he had a son to help him at the forge and in his other activities. As a result, Nansa often helped him and even learned how to forge iron, not just operate the bellows and fetch water, as

43 In her introduction, Romero acknowledges that the narratives presented are framed by the cultural and disciplinary expectations of the tellers of the stories. A couple of the contributors were folklorists who set out tape recorder in hand to document the autobiographies of particular indi-viduals. Others did not intend to produce such a work, but in the course of their research on other topics, they got to know particular women as individuals, with interesting stories to tell.

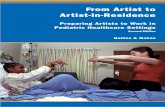

Nansa Doumbia working on a series of waterjars (Kangaba, 1992).

BARBARA E. FRANK78

is commonly asked of female children. By her own account, she was a willful child. She once told me about having misbehaved. To avoid her father’s pun-ishment she climbed up into a tree out in the bush and refused to come down. He decided to leave her there to teach her a lesson. After dark she climbed down and went to stay with friends in a hamlet near town. She then returned to the tree before dawn in order to make her father think she had been there all night.

Nansa was married to her first cousin Numukan Kante when she was about fifteen.44 Nansa accepted this arranged marriage, in contrast to one of her sis-ters who caused her father great distress by refusing to marry the man selected for her. Nansa was Numukan’s first wife. She moved from her family’s village

44 Numukan’s mother was Nansa’s father’s half-sister (same father, different mother). I never met Numukan. He was away most of the time I was there in 1991 and he passed away just before my return in 1992. Although I had hoped to apprentice myself with Nansa during the second field season, she and her two co-wives went into a proscribed four-month period of mourning, during which she was not allowed to make pottery. I was able to spend some time with her, but not as much as I had hoped. At the end of the mourning period, we traveled together to her home village of Gouala to visit her father and meet her extended family.

Nansa Doumbia punching holes in the base of a

large couscous strainer (Kangaba, 1991).

NANSA DOUMBIA: MATRIARCH, ARTIST, AND GUARDIAN OF TRADITION 79

of Gouala on the east side of the Niger River to Kangaba, where both had other relatives. Her paternal grandmother was born in Kangaba and at the time of my research, it was her grandmother’s brother, Mamadi Kante, who was the kuntigi of the Kante blacksmith quarter. Nansa was initiated during the age-grade ceremonies that happened every seven years when the Kamabolon, Kangaba’s famous sanctuary, was re-roofed. This enabled her to form bonds with other young women of her age group within the blacksmith quarter.

Nansa said that her husband was a likeable person and a gregarious man, noting that he was especially attentive to young women. When Nansa had just given birth to their first child (and was thus sleeping in the room with her mother-in-law as was customary), Numukan began bringing young women home. She said they would try to impress Numukan by being especially atten-tive to Nansa’s young children. When he took Nansira as a second wife, Nansa did not object. And when he married Sogolomba, again she did not object. In-deed, on one occasion, Numukan had an argument with Nansira, told her to leave, and threw all of her possessions out into the street. It was Nansa who intervened, collected her things and brought her back into the compound. It was because of Numukan’s respect for Nansa that Nansira was allowed to stay.

At the time of our last interview in 1999, Nansa had eight living children, five boys and three girls. None of her sons were working as blacksmiths. Her eldest son was living and working in Bamako, while her other sons remained in Kangaba. Bariba was the only one of her daughters who was making pottery. She was married to a blacksmith and was living in a small hamlet some dis-tance from Kangaba. Nansa’s daughter Kamba remained at home and, along with her brother’s wife, helped with cooking and other household tasks, thus freeing Nansa to devote her attention to pottery production. Kamba never learned to produce pottery, as she preferred to make millet and bean cakes to sell in the market. When I first met her, Kamba had a son by a liaison with a young man of horon birth who had refused to marry her. By 1999 she had had another boy and a set of twins apparently by this same man, who still refused to acknowledge paternity. Safiatu was the youngest and although she helped her mother with pottery-making when she was a young girl, she chose not to follow in her mother’s footsteps. She preferred to sell cakes in the market like her sister Kamba.

Nansa had respect for marriage traditions and was greatly troubled by pros-pects for her daughter Kamba’s future and for her illegitimate grandchildren. However, there were limits. After Numukan’s death in 1992, his brother Faguimba apparently expected Nansa to accept his sexual advances, as he felt it was his right as Numukan’s older brother to assume responsibility for her and garner the benefits. He and his first wife and daughter lived within the same family compound. He signaled his interest by pressing some coins (the kola price for marriage) into Nansa’s hands. However, Nansa refused, and at

BARBARA E. FRANK80

her request was married to Numukan’s younger brother Shaka, who lived in Segou. This was an acceptable arrangement for Nansa, given that she would be allowed to remain in Kangaba with her children, and that once the ceremony was performed, her new husband would return to his family in Segou.

In my view Nansa exemplified the role of matriarch. She was clearly the central figure during my time with that extended family. She generated most of the income, and in the absence of her husband made most of the decisions that held the family together. Admittedly, the situation might well have been differ-ent ten years earlier, before Numukan’s death, and when Nansa’s mother-in-law was still alive. And yet my sense was that Nansa had always been a person to be reckoned with, from the willful acts of her childhood, to maintaining her position as the first wife and managing to the extent possible the family dy-namics. On various occasions, I saw others in the community defer to her judg-ment and seek her counsel on a range of matters, including the appropriate time to schedule a circumcision or the best herbal medicine to treat a particular ail-ment. Although it would be a stretch to suggest that she had complete control over her life, I do think she rose to the challenges she faced with a remarkable strength of character. She brought a similar sense of purpose to the craft of pot-tery making.

Nansa as artistIn the early 1990s there were about a dozen active potters in Kangaba either born of or related by marriage to two distinct blacksmith lineages. In the first weeks of my research, I was careful to give my attention to different women in

Nansa Doumbia with her father, Boundiali Doumbia (Gouala,1992).

NANSA DOUMBIA: MATRIARCH, ARTIST, AND GUARDIAN OF TRADITION 81

part because I wanted a broad base of information for comparison, and perhaps because I thought this would allow me to remain more objective for the rather synthetic project I had in mind. I interviewed a number of different women, photographed them forming and firing, observing their interactions in the weekly market, and getting to know their families. As my research progressed, I found myself spending more and more time with Nansa, in part because I appreciated the quality of her artistry.

At that time, Nansa was unquestionably the most skilled potter working in Kangaba. She rarely had a stock of vessels for sale at the compound, since most were commissioned, or purchased soon after the firing. She did not take her pots to the market, as her clients knew to come to her compound to buy or commission pieces. Nansa told me the story of her own precociousness. She said that she decided early on that she wanted to learn to make pottery. She approached her husband’s adoptive mother who was initially reluctant to take Nansa on as a student. In order to convince the older woman to allow her to ‘sit next to her’ and learn, Nansa made shea (‘karité’ in French) butter for her. She finally agreed, and they went through the whole process together, from prepar-ing the clay, to making the vessels, through the firing. When the firing came, Nansa was better prepared than her teacher, with more wood and more of the vegetable liquid to treat the pots hot from the fire.45 Her pots came out better. So the next day they took all of the pots to the market where her mother-in-law was expecting someone who had commissioned several pieces. Nansa was off shopping when the client came to collect her commission. Apparently she pre-ferred Nansa’s pots. When Nansa returned to discover that her pots had been sold, she was thrilled and asked for the money. Her mother-in-law claimed that the client had made a mistake and taken the wrong pots, but Nansa knew better and eventually got her money.

Nansa took great care with each step of the process. She worked very slow-ly and deliberately but with few breaks. She did not shy away from difficult commissions. While many potters avoid couscous steamers altogether, Nansa accepted a commission for an especially large one while I was there. Indeed, she produced two in case one failed in the process. She overcame a couple of problems in the making, one cracked while drying, and her two-year old grand-son put his fist through the other one. Both were repaired and came success-fully out of the firing.

Nansa also did not shy away from artistic challenges. In 1992, her sister-in-law returned from a trip to Mopti with a different style of water jar that had a wide flared rim, a style I recognized as typical of Somono and Fulani pots from the Inland Niger Delta region. Nansa decided to try her hand at replicating the

45 Women often fire together with other potters, but each are responsible for providing the fuel (wood and cow dung) needed to fire their own pieces. Each woman then has a designated section of the pile for her pots and her fuel.

BARBARA E. FRANK82

vessel. Her first attempt was functional, but not especially successful in aes-thetic terms. By 1999, she had perfected her skills to make vessels of this type that were graceful and beautifully proportioned. She was working on several of these during my visit, but had none in stock.

Nansa was also generous with her expertise. Kaninba Kante was a potter who often came and worked next to Nansa. As they worked, Nansa would stop to offer advice, or help her with the forming, even sometimes finishing her friend’s pieces for her. They often fired together as well. On one occasion we had recorded their firing late into the evening and arranged to meet Nansa and Kaninba in the morning, to assess the results. Nansa did not appear at the firing ground as planned. We later found out that she stayed away intentionally to give Kaninba a chance to sell her work to us. Even with Nansa’s help, the qual-ity was just not the same.

In fact, none of the other potters I observed produced pottery of an equiva-lent range or quality.46 On my first visit to Kangaba in 1988, I met and inter-viewed Nakani Kante, who was Numukan’s younger sister. Nakani was a very skilled potter, but due to family responsibilities and failing health, even in 1991 and 1992, she was not producing much in the way of pottery. She occa-sionally made cooking pots as well as small, intricate and difficult pieces, but was no longer making large vessels of any kind.

Nansa’s co-wife Nansira also made pottery. For most of my time there she had a stockpile of vessels for sale leaning against the outer wall of her room. Nansa said nothing when I first asked about these vessels. But one afternoon when Nansira was not around, Nakani and Nansa took me over and critiqued them, saying that Nansira had been in too much of a hurry. The pots were thick, and dull sounding, thus not properly fired, with reddish spots because she hadn’t used enough liquid to treat them hot from the fire. The stockpile did not noticeably diminish while I was there.

Nankan Kante was another active potter in Kangaba. Her husband and Nu-mukan were half-brothers. Nankan seemed to have the technical skills to pro-duce a range of vessels, but absolutely no finesse. During one of my first ses-sions with her, she was working on two nearly complete large water jars. She finished one of them and set it aside. As she began adding coils to the second one, it cracked and collapsed. She complained that there was too much temper in the clay body that had been mixed by her daughter-in-law. While it may have been easy to lay the blame with her daughter-in-law on this particular occasion,

46 My judgment of the quality of the different potters’ work was based only in part on my own aesthetic criteria. It included tracking the number of pots lost in a firing, usually due to poorly mixed clay with impurities, poorly formed pots, or vessels insufficiently dried before the firing. Nansa rarely lost any of her pieces in the firing. A large stockpile of unsold vessels was also an indication of how others viewed the work. However, quality is just one of a number of factors that enter into a decision to purchase or commission pots from a particular potter, as women often have long term relationships with particular clients.

NANSA DOUMBIA: MATRIARCH, ARTIST, AND GUARDIAN OF TRADITION 83

there were other indications that she was a less than consummate artist. Her cooking pots and water jars were heavy, with roughly polished surfaces, and sloppy design patterns. She avoided altogether the trickier vessels such as cous-cous steamers and braziers that require cutting into the surfaces of leather-hard clay. In addition, she often lost pots in the firing due to cracking or shattering. By 1999, Nankan had incorporated the new style of water jar with a flared rim into her repertoire, but in my opinion, hers lacked the sophistication of Nansa’s pots. The large number of these vessels in her storage room served as an indica-tion that my assessment of the quality of her work was shared with others.

Similarly, other potters in the community produced the basic range of ves-sels in some quantity, but without the quality evident in Nansa’s work. Minata, Nansa’s half sister, was a competent and productive potter, who worked very quickly. Minata fired together with several other women from the main Kante family compound, and often had twice as many pieces as any of the others with whom she fired.

On reflection, I suggest that Nansa’s success as a potter was not a matter of some innate ability, but rather a result of her own conscious drive to excel at the craft. Rather than produce in quantity, she chose to treat each vessel with care, and the time invested paid off in the returns. Her pots sustained fewer losses during the production process and especially during the firing, and she more readily found a market for her finished pieces. On more than one occa-sion, women came to purchase pieces directly from the firing, before they were even cool enough to transport. Thus, Nansa excelled at the craft for which blacksmith women are known.

Nansa as guardian of traditionIvor Wilks (1988), in his reconstruction of the life of Akyaawa, noted how much the past is an all-pervasive part of the present for the Asante. He com-mented that Asante children are not so much taught about the past as socialized into it. This was certainly true for Nansa. She was proud of her identity as a numumuso, and she had a strong sense of historical consciousness. In 1992, I traveled with Nansa to visit her father, Boundiali Doumbia, and her extended family in her home village of Gouala. During our interviews I realized that much of what Boundiali told me about numuya, and about his own family’s heritage, I had heard before, from Nansa. He told me that numu were the first to inhabit the world and that blacksmiths and potters would never die of hunger because they were so essential to the Mande way of life as farmers. He told me about the purest of blacksmith-potter clans - the Kante, Fane, and Sumaworo, and also about how ancestors of other clans, including his own lineage of Dou-mbia, became apprenticed to blacksmiths, thus learning the trade and becom-ing numu in the process.

Boundiali also told me that numuw always marry numuw, whether or not they exercise their right to practice blacksmithing or pottery. I was not sur-

BARBARA E. FRANK84

prised by this assertion, as I had been told this many times. However, I was also aware what other scholars had written about the permeability of ethnic boundaries and the fluidity of ‘caste’ and other identities. According to La-Violette (1995), Somono women potters in Djenné, for example, manipulate social categories for their own benefit by choosing to marry into any one of a range of families with different craft associations. In my own research, I was especially interested in seeing the extent to which endogamy was an ideologi-cal ideal, but not something that was strictly adhered to in practice. I drew dia-grams of the layout of compounds, identifying kitchens, storerooms and sleep-ing rooms with the different wives. I charted the various interrelationships - the married sons, the adoptive mothers, the visiting relatives, the co-wives. These exercises revealed some range of variation in individual circumstances, but this rarely included marriage outside the local blacksmith-potter lineages. Without exception, every woman in the blacksmith quarter of Kangaba I inter-viewed had married into a numu family. Nansa’s own situation was not excep-tional in this regard. Both of her co-wives were from blacksmith families, and with the exception of the situation with her daughter Kanba, her other children were also married into numu families. Indeed even Numukan was not able to change the fate of their eldest daughter, Bariba, when two of her uncles arranged her marriage to a blacksmith from a small hamlet outside Kangaba.

However, marriage into a blacksmith-potter family did not automatically entail an obligation to engage in either blacksmithing or pottery. In Nansa’s generation I found that less than half of the men born into numu families prac-ticed the craft of blacksmithing, and about the same for numu women becom-ing potters. While this is not a new phenomenon, increasingly fewer young people are learning the crafts of their elders.47

In one important respect, Nansa herself chose not to engage her birthright: she refused to become a negetigi (‘owner of the iron [knife]’, one who per-forms excision on young girls). Her husband’s mother and his adoptive mother, from whom Nansa learned to make pottery, were both practitioners. The latter apparently attempted to train Nansa in the procedures, but she refused. Nansa said that to become a negetigi, one needs a special kind of courage, which she did not have. I suggest that it also took courage to stand up to her mother-in-law on this matter.

‘Guardian of tradition’ is a phrase that reflects the respect Nansa had for her family, her artistry, and her identity as a numumuso. During the course of my research, I encountered no more than a handful of potters who took the kind of care and pride in their artistry as that I observed in Nansa’s work. It is not sur-

47 Only one of Nansa’s three daughters had learned the craft. Of Nakani Kante’s five daughters (by two different husbands) not one had become a potter. Numusira, another potter of Nansa’s generation, was teaching her granddaughter, but no other women in her family made pottery. None of Nankan’s daughters were making pottery when I was there.

NANSA DOUMBIA: MATRIARCH, ARTIST, AND GUARDIAN OF TRADITION 85

prising that Nansa became the primary focus of my research in Kangaba, and that she figures prominently in the synthetic portraits I have provided in much of my own writing about Mande potters. Alternatively, I could have ‘written against culture’ by focusing on numumusow who disrupt the status quo by re-jecting their birthright in one way or another. I could have told the story of one of my research assistants, for example, a woman from a blacksmith family, well-educated in the French system, fluent in English, and working at the time as a teacher and translator in the capitol city of Bamako. She once told me that she was embarrassed when she would be singled out at marriage celebrations as a numu. For her it was an issue of class, one that her education had allowed her to rise above. There is also the story of Kanba, but it is too early to tell whether her willful rejection of Mande social mores will give her the strength to succeed, or doom her and her children as a burden to her family.

Indeed, the lived experience of many of the men and women I interviewed was often at odds with the stereotypes they themselves espoused as central to Mande ideology concerning the roles and expectations of numu identity. Para-doxically, Nansa Doumbia was not a typical numumuso because of the extent to which her life history exemplifies that of the ideal Mande blacksmith-potter. Even within admittedly limited options, she chose not to subvert the constraints of Mande cultural expectations, but to accept them, work them to her advan-tage to the extent possible, and even to excel within them. If we understand the stereotype to represent a cultural ideal, then it is one that Nansa’s life history embodies to an exceptional degree.

REFERENCES

Abu-Lughod, L. 1986. Veiled Sentiments: Honor and Poetry in a Bedouin Society Berkeley, Uni-versity of California Press.

Abu-Lughod, L. 1993. Writing Women’s Worlds: Bedouin Stories Berkeley, University of Califor-nia Press.

Bay, E. (ed.) 1982. Women and Work in Africa Boulder CO, Westview Press.Berger, I. and E. Frances White. 1999. Women in Sub-Saharan Africa. Restoring Women to His-

tory Bloomington/Indianapolis, Indiana University Press.Conrad, D.C. and B.E. Frank (ed.) 1995. Status and Identity in West Africa: Nyamakalaw of Mande

Bloomington/Indianapolis, Indiana University Press.Frank, B.E. 1998. Mande Potters and Leatherworkers. Art and Heritage in West Africa Washing-

ton DC, Smithsonian Institution Press.Geiger, S.N.G. 1986. ‘Women’s Life Histories: Method and Content’ Signs 11-2: 334-351.Grosz-Ngaté, M. and O.H. Kokole (ed.) 1997. Gendered Encounters: Challenging Cultural

Boundaries and Social Hierarchies in Africa New York/London, Routledge.Hafkin, N.J. and E.G. Bay (ed.) 1976. Women in Africa: Studies in Social and Economic Change

Stanford CA, Stanford University Press.Hay, M.J. 1988. ‘Queens, Prostitutes and Peasants: Historical Perspectives on African Women,

1971-1986’ Canadian Journal of African Studies/Revue Canadienne des Etudes Africaines 22-3: 431-447.

Hay, M.J. and S. Stichter (ed.) 1984. African Women South of the Sahara London/ New York, Longman.

BARBARA E. FRANK86

Hodgson, D.L. and S. McCurdy. 1996. ‘Wayward Wives, Misfit Mothers, and Disobedient Daugh-ters: “Wicked” Women and the Reconfiguration of Gender in Africa’ Canadian Journal of African Studies/Revue Canadienne des Etudes Africaines 30-1: 1-9.

Hodgson, D.L. and S. McCurdy (ed.) 2001. ‘Wicked’ Women and the Reconfiguration of Gender in Africa Portsmouth NH, Heinemann.

LaViolette, A. 1995. ‘Women Craft Specialists in Jenne: The Manipulation of Mande Social Cat-egories’ in: D.C. Conrad and B.E. Frank (ed.) Status and Identity in West Africa: Nya-makalaw of Mande Bloomington/Indianapolis, Indiana University Press: 170-181.

Romero, P.W. 1988. ‘Mama Khadija: A life history as example of family history’ in: P.W. Romero (ed.) Life Histories of African Women London/Atlantic Highlands NJ, Ashfield Press: 140-158.

Romero, P.W. (ed.) 1988. Life Histories of African Women London/Atlantic Highlands NJ, Ash-field Press.

Robertson, C.C. and M. Klein. 1983. Women and Slavery in Africa Madison, University of Wis-consin Press.

Robertson, C.C. and I. Berger. 1986. Women and Class in Africa New York, Africana Publishing Company.

Smith, M.F. 1954. Baba of Karo, A Woman of the Muslim Hausa London, Faber and Faber.Stichter, S.B. and J.L. Parpart (ed.) 1988. Patriarchy and Class: African Women in the Home and

the Workforce Boulder CO, Westview Press.Szklut, J. and R.R. Reed. 1988. ‘The Anonymous Community’ American Anthopologist 90-3:

689-692.Wilks, I. 1988. ‘”She who blazed the trail”’ Akyaawa Yekwan of Asante (1774-1834)’ in: P.W.

Romero (ed.) Life Histories of African Women London/Atlantic Highlands NJ, Ashfield Press: 113-139.

Wright, M. 1993. Strategies of Slaves and Women. Life Stories from East/Central Africa New York/London, Lilian Barber Press/James Currey Press.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Preface 5(Stephen Belcher, Jan Jansen and Mohamed N’Daou)

Puppet Masquerades in Kirango, Mali: Continuity, Innovation, 7and Changing Contexts(Mary Jo Arnoldi and Elisabeth den Otter)

Locating Sankaran, Locating the Conde 16(Laura Arntson)

The Problem of the Mande Creation Myth 31(Ralph A. Austen)

Beyond Excavation - The Dia Archaeological Project 40(Rogier M.A. Bedaux and Annette M. Schmidt)

Deconstructing the Conradian Modus Operandi 47(Louise Bedichek)

Some Observations on the Textualization of the ‘Charte de 48 Kouroukan Fougan’(Stephen Belcher)

‘Si Allah le Veut’ - A Tribute to David Conrad 55(Louise M. Bourgault)

Homage to Daouda Conde 59(Brahima Camara)

The African Intellectual in the Court of Public Opinion: 61A Critical Reflection(Mamadou Diawara)

Nansa Doumbia: Matriarch, Artist, and Guardian of Tradition 73(Barbara E. Frank)

The Struggle for Leadership in Mande 87(Nicholas S. Hopkins)

TABLE OF CONTENTS4

Trade, Identity and the Linkages between Freetown and the 93Mande Heartland(Allen M. Howard and David E. Skinner)

Mali by Stamps - An Inquiry into a Country’s Image 100(Jan Jansen)

Words of Power: Magical Spells of the Mande Hunters 113(Agnes Kedzierska-Manzon)

Deep Discourses – A Tour of the Mande Power Landscape 123(Roderick J. McIntosh)

Mediations: Tayiru Banbera and David Conrad 132(Paulo F. de Moraes Farias)

Djibril Tamsir Niane and David Conrad: Collaborative Re-imagining 144of the Mande Past Across the Atlantic(Mohamed Saidou N’Daou)

On the Terminology of the Mande World 174(Mamadou Lamine Sanogo)

Faso and Jamana: Provisional Notes on Mande Social Thought 181in Malian Political Discourse, 1946-1979(Brandon County and Ryan Skinner)

In Memory of a Great Singer: The Dogon Baja Ni as a 193Cultural-Historical Performance(Walter E.A. van Beek)

To Be Respectful in Mande - Where Does Maninka Honorific 216Vocabulary Come From?(Valentin Vydrine)

Publications by David C. Conrad 226

Authors’ Index 231