My Struggle at the Boundary Walls of Participant Observation

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of My Struggle at the Boundary Walls of Participant Observation

Citation: Majumder, Atreyee. 2022.

Devotee/Ethnographer: My Struggle

at the Boundary Walls of Participant

Observation. Religions 13: 538.

https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13060538

Academic Editors: Mike Sosteric,

Wendy Bilgen and Gina Ratkovic

Received: 22 March 2022

Accepted: 9 June 2022

Published: 13 June 2022

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral

with regard to jurisdictional claims in

published maps and institutional affil-

iations.

Copyright: © 2022 by the author.

Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland.

This article is an open access article

distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons

Attribution (CC BY) license (https://

creativecommons.org/licenses/by/

4.0/).

religions

Article

Devotee/Ethnographer: My Struggle at the Boundary Walls ofParticipant ObservationAtreyee Majumder

National Law School of India University, Karnataka 560072, India; [email protected]

Abstract: This article demonstrates the difficulty of incorporating within the methodological ambit of‘participant observation’, a possibility of the ethnographer herself staking claim in the religious truthclaims of the community that constitute the subject of research. In so doing, this article provides acritique of the concept of participant observation to point out that participant observation anticipatesthe work of the ethnographer in participating in the physical, performative lives of the communitythat she purports to study, but never the internal life, especially the life of accessing a register oftruth. I found myself in a curious situation as a devotee, where I was accessing the truth-claim ofthe Krishna-worshipping Vaishnava community, even before I could attempt to participate in theircommunitarian lives of worship. I found, in the coupling of the devotee and ethnographer identities,that participant observation in the traditional anthropological sense became difficult. The article is,thus, a meditation on this difficult journey and the pendulum of my devotee/ethnographer self thatit produces.

Keywords: Bhakti; devotion; presence; participant observation; autoethnography

In April to May 2018, while heavily medicated in a hospital, and mostly sleepingor half-awake, I had a series of dreams/hallucinations. A turning point in my stay atthe hospital, and in my medical treatment, was a vivid, powerful, and indelible dream1

featuring the Hindu God Krishna.2 I retain until this day some memories of that dream(the details of which I will not share here), but it was, in all kinds of ways, a turning pointin my life and in my practice of anthropology. To perform a loyalty to this dream, I startedgoing to Krishna temples. I have been an agnostic person until the occurrence of the dreamin April 2018. My family are practicing Hindus, and I had always been mildly derisiveof the elaborate and ritualistic nature of this practice. In a predictably secular move (seegenerally, Bhargava 1998; Taylor 2007), I had even derided religion and its prominence inthe Indian public sphere, especially because of the rise of the Hindu right (Jaffrelot 2007).In a dramatic turnaround, I became (following this dream) a Krishna-Bhakt (devotee). Asit happens, I am still unpacking the implications of this turnaround in my personal andpolitical life.

Needless to say, I had never been to these sites of Krishna-worship before and hadnever devoted any attention to Krishna or the religious traditions surrounding his divinity.Predictably, my earthly search for Krishna took me to Vrindavan—the sacred geography ofKrishna worship in northern India. By this time, I had read some English translations ofthe Gita. I knew intellectually about the Bhakti tradition that focused on the Hindu GodVishnu or his ninth Avatara (incarnation)—Krishna. However, this textual training was notsatisfying enough. That first train ride in February 2019 from Delhi to Mathura, and theshort taxi ride to Vrindavan, took merely two hours, but I arrived in a different world. I wasnot sure exactly in what capacity I was to approach this town—anthropologist or devotee.

I entered Vrindavan as a devotee and as an anthropologist, and I was constantlyswitching roles. The sensory provocation and associated defeat at the hands of the God-head went simultaneously with the rational compulsion to study as a researcher—remainconstantly aware and watching—until those faculties started failing. I started research in

Religions 2022, 13, 538. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13060538 https://www.mdpi.com/journal/religions

Religions 2022, 13, 538 2 of 14

Vrindavan in search of Krishna, the giver of spontaneous Bhakti, who I was told, residedas the other-worldly sovereign in the region of Braj—modern Vrindavan, Mathura andsurrounding satellite towns.

The Bhagavad Gita (Mascaro 2003), I had learnt by now, speaks of three elements of theunion with God—sat, cit, ananda—truth, consciousness, bliss. In Vrindavan—the sacredgeography of Krishna-worship in northern India—I started learning to experience joy (someversion of Ananda) at intuiting Krishna’s presence. The concomitant act of conductingresearch, therefore, was complicated by this individual experience of extreme joy or Anandain the presence of the Godhead. I was simultaneously trying to find a way to practiceBhakti in my inner, spiritual life while conducting ethnography about the everyday lifeof Bhakti that negotiates competing sovereignties of Krishna and the nation-state. Thisarticle, thus, travels through the split subjectivity of the ethnographer as they are tryingto gather ‘data’ on the lives of worship while consuming the ambience of the Godheadas a devotee.3 This article asks: What does ethnographic research look like when one issimultaneously engaging in doing the thing that one is mandated to watch others doing?What happens when the doing and watching diverge in consequence? I realize this isthe primary definition of whatever form ‘participant observation’ must take. In its actual,literal doing, this kind of ‘participant observation’ hits upon a real conundrum—whetherto immerse in the doing, or the watching, and the inevitable conclusion that the two cannothappen simultaneously. If the two must diverge, I suspect they will deliver two verydifferent ethnographies. This conundrum is mapped onto the simultaneous habitation ofthe selves of research and devotion. Further, this article reflects on the implied, resultantdifficulty of then doing actual ‘participant observation’ of religious processes if one isin some sense, a devotee of the same faith, and accessing the truth of the faith that oneis studying.

1. Bhakti

First, for the unacquainted reader, let me briefly talk about Bhakti. Bhakti is a movement—with various iterations between the 8th and the 19th centuries—that centered around song andpoetry of devotion to the Hindu God Vishnu and his various Avataras, especially Krishna. Themovement cast aside caste hierarchies, inaugurating a tradition of spontaneous, unscriptured,devotional worship. The movement gained significant momentum during the sixteenth century,especially with the rise of Chaitanya, a saint from the eastern region of Bengal, who is consideredto be the unified version of Radha (Krishna’s primary consort) and Krishna4.

Tracy Coleman defined Bhakti thus:

The Sanskrit term Bhakti is generally translated as “devotion” and refers to avariety of Hindu traditions in which devotees experience a direct relationshipwith the divine. Such divinity may be conceptualized as an incarnate personaldeity or as the formless metaphysical essence of the cosmos, and modes or moodsof devotion thus vary accordingly, ranging from contemplative forms of yoga tooutbursts of passionate love. Expressed as loyalty to God incarnate in humanform, Bhakti in the Sanskrit epics is typically consistent with the demands ofBrahmanical dharma, but devotion that defies social and religious norms iswidely celebrated in later texts and traditions, with women and low-caste menamong the most famous devotees, their poetic verse an enduring inspiration toothers seeking salvation without the benefit of orthodox privileges and rituals.Flourishing in diverse linguistic and regional expressions, Bhakti traditions reflecta wide variety of religious movements, some conceiving Bhakti as intenselypersonal devotion, others finding in Bhakti the power of social and politicalreform. (italics added). (Coleman 2011)

In Hindu cosmology, Braj (the area around the city of Vrindavan in northern India) isa Tirtha (sacred geography)5. Barbara Holdrege defined tirtha thus:

Religions 2022, 13, 538 3 of 14

Tırthas, as centers of concentrated divine presence associated with particulardeities, are variously represented as manifestations of the deity, parts of thedeity’s body, special abodes (Dhamans) of the deity, or sites of the deity’s divineplay (lıla). (Holdrege 2015, p. 22)

Bhakti is a register of extreme devotion that generally avoids other Hindu/Buddhistreligious goals of moksha (salvation). Instead of journeying towards shedding all pain andpleasure, Bhakti teaches its followers to take sensuous pleasure in watching the world’smaking as god’s (especially Krishna’s) playful dance. David Haberman describes Bhaktias a taste for watching “purposeless play” (Haberman 1994, p. 26) of life; where onewould rather “taste sugar, not become sugar” (Haberman 1994, p. 25). The enjoymentof Bhakti, Haberman describes, cannot be contained in an empty center—“the zero pointmust explode outward into the ever-expanding kaleidoscopic multiplicity of forms—and,in doing so, become pointless”. (Haberman 1994, p. 25).

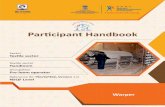

2. Faith and Squeamishness

With this intellectual introduction to Bhakti, I traveled to Vrindavan. The ancient,somewhat dilapidated city opened up many challenges that do not make for easy curationin an ethnographic narrative. I watched an evening Arati (evening offering) by the banks ofthe murky Yamuna. I sat, cautiously on the stone steps of the ghat before I was invited tojoin in to hold a plate with a lamp and flowers by the women who were helping the mainpriest. The main priestly person animating the event lit a massive brass lamp holder (seeFigure 1) and slowly started dancing. Another man, who looked like a locally powerfulperson, stepped forth and took the lamp holder from him. He held the obviously heavyand hot object with an orange cloth and continued the dance. It was a show of masculinepower. These men were entitled to lift this massive brass lamp holder in offering homageto Shri Yamunaji or the river Yamuna. Stuck to the walls of the ghat, there was a massiveposter that declared solidarity towards Indian CRPF6 soldiers who died in the terroristattack in Pulwama, on the Indo-Pakistan borders, the day before. A huge poster wasstuck by the side of the ghat declaring allegiance to the Hindu fight for nationhood—thiswas the evening of the recent Pulwama attack on Indian soldiers by the Jaish-e-Mohammadterrorist outfit.

It was Valentine’s Day.Religions 2022, 13, x FOR PEER REVIEW 4 of 15

Figure 1. Brass-lampholder lit for the evening Yamuna Arati. Photo credit: Author (14 February 2019).

This scene was saturated with material provocation for the senses—fire, camphor, flowers, water. This assembly was offering respect to a much ecologically damaged river. This was religion - heady, provocative, and jingoistic, thought I. The declaration of sup-port to the Indian military forces and by association, the strong-arm Indian nation-state, through this idiom of dance, made me squeamish. I was ready to submit myself to the Krishna-worshipping traditions, yes, but the political associations that were being enacted in the performance of the evening Arati were unacceptable to me. My faith was born out of the hospital dream. However, accepting the practical dimensions of immersion in a faith-based community was not easy. I was constantly cautious and squeamish in Vrinda-van. I was simultaneously overwhelmed with joy in Vrindavan.

Sovereignty was displayed here in the name of Krishna8. This was Vrindavan. The sacred territory of Lord Krishna. This is where he is believed to have been raised simply among a community of cowherds—the Yadavas (Hawley 1983). He is worshipped by var-ious sects here in a parental capacity. The devotees take on the mantle of being his parents or parental figures helping raise a mischievous, butter-stealing Kanhaiyya. They chant:

hathi, ghoda, palki, jai kanhaiyya lal ki! Elephant, horses, and sedans, glory to the child Krishna.

3. Crowd Fellowship Bhakti demands participation in this public culture of excess9—excess that nakedly

professes love for the Godhead, among others doing the same, through song and dance. It is a public culture that cannot be likened to the public that we know of in Habermasian scholarship for its interests do not lie in critical, rational debate or argument with the dem-ocratic state10. It is the emphasis on the irrationality of love that joins together this mass of amorphous humans as some sort of public. It is an empathetic, expressive assembly that calls out to the Godhead in unison—especially in poetry, singing and dancing. This as-sembly is significant in its absolute absence of state-initiated regulation of public space.

A religious public or assembly fits uncomfortably in this genealogy of ‘public’11—that is crucially based on the differentiation between state and society. In Vrindavan, it is a gathering made legible through the common contemplation of the Godhead, through singing, chanting, dancing and walking. However, linking the Godhead to the political ambition of a Hindu nation-state lurks at every corner of this public performance in

Figure 1. Brass-lampholder lit for the evening Yamuna Arati. Photo credit: Author (14 February 2019).

Religions 2022, 13, 538 4 of 14

This scene was saturated with material provocation for the senses—fire, camphor,flowers, water. This assembly was offering respect to a much ecologically damaged river.This was religion - heady, provocative, and jingoistic, thought I. The declaration of supportto the Indian military forces and by association, the strong-arm Indian nation-state, throughthis idiom of dance, made me squeamish. I was ready to submit myself to the Krishna-worshipping traditions, yes, but the political associations that were being enacted in theperformance of the evening Arati were unacceptable to me. My faith was born out of thehospital dream. However, accepting the practical dimensions of immersion in a faith-basedcommunity was not easy. I was constantly cautious and squeamish in Vrindavan. I wassimultaneously overwhelmed with joy in Vrindavan.

Sovereignty was displayed here in the name of Krishna7. This was Vrindavan. Thesacred territory of Lord Krishna. This is where he is believed to have been raised simplyamong a community of cowherds—the Yadavas (Hawley 1983). He is worshipped by vari-ous sects here in a parental capacity. The devotees take on the mantle of being his parentsor parental figures helping raise a mischievous, butter-stealing Kanhaiyya. They chant:

hathi, ghoda, palki, jai kanhaiyya lal ki!

Elephant, horses, and sedans, glory to the child Krishna.

3. Crowd Fellowship

Bhakti demands participation in this public culture of excess8—excess that nakedlyprofesses love for the Godhead, among others doing the same, through song and dance. Itis a public culture that cannot be likened to the public that we know of in Habermasianscholarship for its interests do not lie in critical, rational debate or argument with thedemocratic state9. It is the emphasis on the irrationality of love that joins together this massof amorphous humans as some sort of public. It is an empathetic, expressive assemblythat calls out to the Godhead in unison—especially in poetry, singing and dancing. Thisassembly is significant in its absolute absence of state-initiated regulation of public space.

A religious public or assembly fits uncomfortably in this genealogy of ‘public’10—thatis crucially based on the differentiation between state and society. In Vrindavan, it is a gath-ering made legible through the common contemplation of the Godhead, through singing,chanting, dancing and walking. However, linking the Godhead to the political ambition ofa Hindu nation-state lurks at every corner of this public performance in Vrindavan. Yet,its distinctiveness lies in the absolute turning away from the presence of the state. Thisis an assembly that produces a routine fellowship in the common acknowledgement ofthe presence of divinity. Its ‘crowdness’ is not combative, but joyous, even in the chaosand confusion.

Vrindavan sways to the rhythm of the crowds. The devotee offers herself as anindeterminate fraction of an immense, heaving, sweating, chanting crowd that movesfrom one temple to another. The crowd moves as the devotee-pilgrim pushing, heaving,sweating, chanting as a gelatinous mass of humanity. I move with the crowd hoping tohave moments of quiet, private time with Krishna in one of the main temples, but hardlyany chance of that on the auspicious day of Ekadashi.

The crowd chants Jai Shri Krishna and Radha Rani ki Jai while on its way in and out oftemple sanctuaries and onto cobbled streets. The crowd presents a non-individuated pres-ence of devotion in front of the deity. This breaks down any claim of a special conversationwith the supreme power, or any possible attempt to climb a ladder of equality before God.It makes me claustrophobic and uncomfortable at first. I cling on to my belongings as Iwade my way through crowds. The crowd breaks down any possible remnants of the egoof a devotee—in this case, my ego that expects particular, private access to the Godhead.My particular claims on God, I realized, were not particular at all. I was visiting the deityfor the brief, truncated eros of Darshan11—locking eyes with the deity in a moment—inpresenting my faith, in a vast ocean of dissolved emotion in which each individuatedconversation makes no sense. This was the nature of the audience with Krishna, I learnt.

Religions 2022, 13, 538 5 of 14

He spoke with me as and when he wanted. Large numbers came for this brief audiencein forming an indeterminate population of faith. Faith made sense only in this form. Thisamorphous, frenetic population was calling out to me to immerse myself in it. I foundit difficult. I was scared and cautious. My upper-middle-class, urbane Indian self begangenerating various kinds of anxiety. Anthropologists are cautioned not to see boundedcommunities on the field, but this was as sharply defined a community as there couldbe—sharply defined in terms of space and time (for a detailed genealogy and mappingof community-based ethnographic endeavors and the theoretical insights they yielded,see Brunt (2001)). They were accessing a collective truth. I was trying to access that truthof Krishna’s presence in this sacred geography, individually, while being cautious of myinteraction with the madness of the crowd. Was ethnography possible at this juncture? Ithink not, but I was trying anyway.

The anthropologist, Paul Stoller, trained as a sorcerer and had the experience of losingsensation in his lower body. This was interpreted, when he gained sense back again, asa steppingstone in his sorcery learning journey. He describes the commonplace socialscience understanding that would call it a ‘vivid dream’, yet for him, it was a ‘dream thatwasn’t a dream’ (Stoller 2016, p. 166). Stoller’s is an example of taking the immersionpart of ‘participant observation’ quite literally. I was doing so too, in some measure, andfound soon that the latter mandate of observation of others becomes difficult when you areneck-deep in your own ‘dream that wasn’t a dream’.

4. Demand on the Godhead to Play

Krishna is indeed the carrier and declarer of sovereign authority to this day in thesacred territory of Braj—Vrindavan, Mathura, Gokul, Barsana, Nandgaon. In Krishna’sname, this land was bestowed with the imagination of simple cowherd life, or lovingparents, and Leela between the adult Krishna and Radha, surrounded by Gopis. Leela is akind of jouissance—Krishna’s play (what Haberman calls ‘purposeless play’) where hedeliberately makes himself an innocent child or young cowherd to play with his subjectpopulation. His mother Yashoda and his primary lover Radha assert power over him. Thus,they too are interpellated in the Vaishnava pantheon in these temples strewn all over theBraj region.

The animation of play and acting in various capacities to the baby or young Krishnaforms the core of worship here. A priest at the Banke Behari temple tells me, “we don’tfollow very rigid procedures for puja or worship. We simply enact bhava (essence or mood).We take care of the deity as we would a little child. We pull the curtains over the deity fromtime to time, just as we would a little child. We wouldn’t want everyone to stare at the child.It would bring him nazar”. The worship thrives in anthropomorphizing divinity to a pointof extreme detail. The devotee exercises several roles of extreme gentleness and care—as aparent, villager, neighbor, cousin, lover to Krishna. Yet, the same devotee protects the rightof Krishna to rule over his territory with a warlike effect.

In Hindu cosmology, the deity comes to occupy Prana (life) at the point of the devotee’slocking of eyes with the Godhead. Religious entities such as deities indeed have a socialfunction, explained in the structuralist tradition (Durkheim 2001). I wish to move awayfrom it and ask about what presence does to the devotee once it is constructed in theorchestration of Bhava (essence). The priests of the Banke Behari temple construct a dailyrelationship of parent–child or familial theatricality around the deity. This ritual practiceinterpellates the deity into the folds of the intimate lives of each devotee. It conjurespresence by performance. Krishna is at once god as he is lover, son, mischievous cowherd,a character whose demand for care and love among his devotees makes his enormous,non-human presence (declared explicitly in the Gita) palatable within human society.

The land of Braj is often referred to as the body of Krishna. Devotees circumambulateand measure this land by moving while lying down on the earth. This is called worshipby dandamati. It is yet another register of presence that is conjured in the physical milieuxof these mundane small towns that come to be known as Braj. Geography translates into

Religions 2022, 13, 538 6 of 14

simple materiality. Sarbadhikary wrote of such mythogeographic presence of imaginedVrindavan in Gaud in Bengal in her work on Gaudiya Vaishnava practice in West Bengal—aneastern Indian province (Sarbadhikary 2015, p. 37). She further wrote of the imaginedVrindavan in the devotee’s heart:

. . . gupta-Vrindavan therefore implying a veiled landscape, which can be unveiledthrough the appropriate spiritual techniques, in this case through the telling ofand listening to stories. (Sarbadhikary 2015, p. 38)

Gupta-Vrindavan is a hidden, imagined Vrindavan that is unraveled by spiritual tech-niques of worship by Gaudiya Vaishnavas in Bengal. This technique often involves imaginingone’s body to be that of Radha, the primary lover of Krishna. Storytelling brings alivethe presence of the Godhead amidst this mundane landscape of small towns—Mathura,Vrindavan, Nandgaon, Gokul, Barsana. It makes possible the enchantment of the entireregion with the presence of the Godhead, not confined only to the physical materiality ofthe deity in the temple. A priest in Gokul pointed to the gardens surrounding a templeand says, “ . . . This is where Krishna danced in the form of a peacock on the request of hisfollowers”.12

The intuition of Krishna’s presence was being enacted at a collective, and for me, anindividual scale on the cobbled streets of Vrindavan. Was this public performance of aprivate emotion, religion? I asked myself. Michael Lambek calls religion a cultural spherethat anchors, more than other spheres, the question of boundaries between immanence andtranscendence, in society. He writes:

. . . Religious traditions are likely to be characterized by diverse practices thatovercome or blur any clear distinction between immanence and transcendence.Concomitantly intellectuals in these traditions debate the relations of the im-manent and the transcendent, divine presence to absence, the concealed to therevealed, proximity to the everyday, divine truth to common knowledge, ultimatereality to the ordinary and the everyday, and the significance of divine interven-tion in human affairs and history, and as well as justifications for various practicessuch as mysticism or devotion to individual saints. Sometimes they emphasizethe possibility and significance of direct religious experience; at other times theyreject or devalue the lived world relative to the transcendent. One way to con-ceive of religion, then, is precisely as a sphere of human activity concerned witharticulating (in thought and practice) the boundaries and relationship betweenimmanence and transcendence. (Lambek 2016, p. 16)

The question of a special place in society, where people come to contemplate theirmaker, persists. Transcendence takes diverse forms in different societies. This placestands apart from the various non-human entities such as ghosts, spirits, ancestors thatare necessitated as insurers of a good and stable life on earth. I encountered in the Brajregion, the direct act of calling God into the intimate folds of one’s immediate worldly life.Krishna’s sovereignty does not follow a direct script. He declares his sovereignty in clearterms only while opining on Dharma in the Bhagavad Gita to Arjun, to whom he is a friendand charioteer, in the battle of Kurukshetra. The same Krishna makes himself subservient inthe lives of his devotees as lover and friend and beloved cowherd and general merrymaker.He shows his powers intermittently—for instance, by lifting the mountain of Damodar toprotect his clan, the Yadavas. It is this switching of God’s presence between several versionsand diverse materialities that refuse its determination by the social location of the devotee.Krishna is time and again, in the care of and subservient to his devotee. Krishna’s presenceis orchestrated through a collective sensory alliance, in the words of Sarbadhikary—an‘intuitive capacity’13—that Krishna comes alive in everyday life in the Braj region. As muchas the transcendence question remains pertinent, it is minimized by intuiting the presenceof God through the deity and in other physical, material forms in the practice of devotionor Bhakti. God is alive in the immediate, worldly life, the seeking of him, thus, is not, atleast in the practice of Bhakti, a distant, alienating journey divorced from the mundane

Religions 2022, 13, 538 7 of 14

ensemble of pain and pleasure of the earth and earthly life. This is enchantment, in someform, I suppose. I wish further, to assert that the practice of Bhakti in modern-day Brajis a socio-cultural complex that casts aside the question of insurance and assurance fromnon-human entities and bathes the contemplation of the supreme power with a kind ofabsolute humanity. My humanity kind of doubled up, at this time, as I constantly tried topay heed to the memory of the hospital dream. Krishna comes alive to all my senses; thedistinction between mind and body begins to fade. What happens in the register of the realworld that I can take down as notes? Nothing. My limbs do not lose sensation the way PaulStoller’s did. I did not check my psycho-physical statistics at this point, so I cannot say if Iwas developing new neural networks or if my heartbeat became faster. It is possible thatthese psychophysical things were occurring. From the ethnographic point of view, this wasthe scene of a mundane ethnography of religious effervescence—singing, dancing, chanting,crowds, flowers, incense—the stuff that would go into the ethnographer’s notebook. Then,there is the messy business of truth (see generally, Borneman and Hammoudi 2009). Ican only convey to another believer the quality of this truth. An ethnographer, journalist,travel-writer, or the most empathetic memoirist would not understand it. Here is the cruxof the difference between traversing Vrindavan as a believer, and traversing Vrindavan, asan empathetic, ever-watchful ethnographer. I was being both, on different occasions.

Walking all over Vrindavan, split between two registers of subjectivity—mad devoteeand calculating, cautious anthropologist, I find participant observation difficult. I consumeKrishna with all my senses at public events as ghats and temples. The collective efferves-cence is daunting, frightening and yet exhilarating. I cry at each chant of Hare Rama HareKrishna. I cry at the sight of them dancing. I have no time nor opportunity to interview orobserve this collective effervescence, as my senses are thoroughly consumed.

Massive crowds were herding me in and out of the Banke Behari temple on to the RadhaVallabh temple, then to the Radha Damodar temple, then to the Radha Raman temple. I watchthe deity in short glimpses before the crowd maneuvers me out of my viewing spot. Iam still an arrogant, individualistic devotee who wants the temple all to herself, wants tohave a lavish, private conversation with the Godhead. Everyone looks up at the dais of theGodhead to get one glimpse before the curtains are pulled over him again, and they haveto wait till the next display. This is the fleeting, charged moment of Darshan. The curtainand the crowd are having a massive flirtation with god’s hiding and display in the eyes ofthe devotee. The devotees’ bodies are merging into one mammoth human congealmentthat comes before the deity, losing its individuation, and with that, its ego.

5. Participant/Observation

ISKCON—the temple of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness—aninternational organization that cultivates Krishna worship, established by Srila Prabhupada(1896–1977)14—emerges as my safe zone. This is a metropolis-class-friendly, somewhatwesternized space. I routinely go to the evening Arati at ISKCON. The crowds make meanxious and so the Arati time at other temples is daunting for me. I sit for hours at thetemple courtyard of ISKCON. This is a relatively domesticated space, the energies hereare tamer. Here, I do not have to witness a spectacle or be forced to think about the linkbetween the space of worship and the larger ethnonationalist Hindu state.

Large numbers assemble for the Arati on the occasion of Ekadashi—an auspiciouseleventh day of the month. The singing of Hare Rama Hare Krishna becomes louder. Thedancing becomes more energetic. The gaze of the deity and the chant of the four wordsmake me howl. As an anthropologist, I am supposed to join the energy of the moment andits associated activities or at least, bear witness to it with alertness. However, participantobservation fails the mandate of the moment for me. As a devotee, I sit in the corner of thetemple courtyard and howl. For I cannot match up to this collective effervescence. I mustwatch it from my corner of the temple courtyard and consume it as a lesser, more fragile,devotee.

Religions 2022, 13, 538 8 of 14

This is Bhakti—it expresses itself as devotion that is purely embodied. Barbara Hol-drege writes of Bhakti discourse and embodiment:

By “discourse” I mean the manifestation of Bhakti not only in performancethrough song or literacy, but also through all those actions and bodily displaysthat make up Bhakti in the broadest sense, such as . . . pilgrimage, puja, darsan, thewearing of signs on the body, and so on. Embodiment, then, is not so much a tech-nique of bhakti as its very epicenter: Bhakti needs bodies. (Holdrege 2015, p. 24)

It is conquered not in knowing much scriptural knowledge, but in self-surrender,devotion and the collective bodily experience of joy. A Caucasian woman, dressed in asari, with its tail end drawn over her head, the way the local women wear the sari—hasbeen dancing throughout the day in the courtyard. Everyone joins her intermittently. Iwatch her and cry. I inhabit a body that is different and separate from my gross, earthlybody (Sarbadhikary marks the difference between Sthhula and Shukkha Shorir—gross andsubtle body). Is it possible, at this stage, to get across to the equivalent of this subtle-body-cognition in other bodies that surround me?

Sarbadhikary wrote:

How can the body be thought about or cognized? How can the cognized andemotional body be the same? Is the spiritual body separate or different fromthe physical body? When a body is interiorized, how is it different from themind? Is an imagined body a body at all, or an expression of cognitive capacities?Does such a body inhabit space? If not, can it still be a body? How can actionbe interiorized? Simply, how should one identify and represent the ‘mind’ and‘body’ in Asian religious contexts? (Sarbadhikary 2018, p. 2082)

The Vaishnava conception of the body is as an instrument capable of cognition. Iexperience this, as I merge uncomfortably into the heaving, chanting, dancing crowd—evenas I remain distinct from the crowd as one that is not dancing but crying profusely. Eachbodily state, in its unique iteration in each human being, seems distinct. Here, the mandateof participant observation fails. It cannot gather the interiority of the movement of eachbody between several bodily states. I can only document the experience of moving tothe state of the subtle body, intuiting presence of the Godhead, through my own bodilyexperience. In Vrindavan, I breathed into a different body, and lost, frequently, the facultyof performing ‘participant observation’ of the bodies around me.

6. Devotee/Ethnographer: My Struggle at the Boundary Walls ofParticipant Observation

This experience of my early fieldwork in Vrindavan got me thinking of the commonlyused stock phrase “participant observation” that anthropologists are taught to bandy aboutto tell the world what it is they do. It involves many practical stages such as journeying toa distant place, finding a place to stay, making formal contacts, beginning with structuredinterviews, slowly creating enough rapport to break into the inner interstices of a societyand finally getting to see things the way the members of the researched society themselvesdo. Thus, participant observation comes to privilege the ‘emic’ point of view ratherthan ‘etic’ point of view (see generally, Pike 1999). So, the end-product of fieldwork—anethnographic monograph or film—emerges to tell the story of society not only as thefieldworker saw it, but as the research subjects, situated in their society, narrated itself. Aclose mirror-image of a society. Ethnography is aimed at unpacking a point of view aboutpoints of view. The ethnographer constantly straddles the inside/outside boundaries ofsociety, sometimes being a friend of the society, sometimes being an objective scholar.15

Maurice Bloch wrote about the acts “from the inside stance” and “from the outsidestance” the ensue in ethnography (Bloch 2017, p. 34). She wrote:

Religions 2022, 13, 538 9 of 14

The “from the outside” stance involves ultimately seeing things in terms ofthe general life of our species as it exists and has existed on our planet. The“from the inside” stance involves sharing as much as possible the point of viewof those we write about in the way that we try to do in any intimate relation.(Bloch 2017, p. 34)

Bloch pointed out an obvious contradiction of the anthropologist’s job—looking insideout and outside in at the same time. She further explicated that the “from the inside” stanceis predicated upon participating in the lives of those who are being studied. She said:

This means that the anthropologist has no other choice in order to get and conveythe point of view of those she studies, than participating in their lives ratherthan listening to explicit statements. It is through this participation—often verylong-term participation—that anthropologists intuit what life in those places islike “from the inside”.

This method is usually called “participant observation”. (Bloch 2017, p. 37)

In this unpacking of participant observation, one is watching and doing to an extent thethings a society is immersed in doing. For instance, one may participate in farming practice,one may drink rice wine at a ceremony with members of the society, one may watch a playthat is put up as part of festivities. There is, through and through, in the understanding ofparticipant observation, an assumption of an obvious discrepancy between the meaningsof the events held by the anthropologist as a person and the meanings they learn fromthis participation to ascribe to these events—the ones that she is taught by members ofthe society she studies. What happens, I began asking in the course of my research inVrindavan, when the set of meanings are similar if not the same—when you are dancing ata community festival not because you want to participate in another’s meaning-making,but because you are immersed in the set of truth-meanings that the community that youare studying is making? Then, participation becomes rather difficult. Participation, in thissense, assumes a disjuncture in the shape of cognition about a situation. I do not personallyknow the members of the Vaishnava devotee public in Vrindavan, but I am present in thesetemple spaces and ghats by the same logic that justifies their presence. In the doing ofdevotion at a personal level, I experience intimacy with God. If you are immersed in suchintimacy, then you will be writing about nothing but this intimacy. The simultaneousoutsider-watching of another’s experience will become difficult. This is nature of thedifficulty I experience through my split subjectivity as ethnographer–devotee.

Here, a question about ethnographic sincerity must be asked though not the usual one.I am, of course, sincere towards my research and the questions and people who populateit. Can I possibly, simultaneously, practice sincerity towards my own religious experienceand conducting participant observation at the same time? Jackson, Jr. refuted the easymandate of ethnographic sincerity as a kind of political solidarity with those that onestudies. He wrote:

To talk about the politics of ethnographic writing in terms of authenticity alone,I want to argue, is akin to dehumanizing and thingifying the ethnographicproject/subject. It debases and vulgarizes the ethnographic encounter itself,concocting an occult intersubjectivity wherein the denied coevalness that charac-terizes our field’s traditional discursive offerings ironically functions as a moreaccurate temporal architecture for a form of vampirism that would deny themutually cathected ethnographic moment its due. This reduces the people wework with—sometimes even as political allies—into political objects no less inertfor their ventriloquized placeholding as reflections of others’ ethnographic andideological interests. (Jackson 2010, p. S283)

I agree with Jackson Jr. that the ethnographic moment is more complex than an easyassumption of authenticity would allow for. I wish to take a step back and ask—what shapeof personhood does the ethnographer assume while on the field? Collins and Gallinat

Religions 2022, 13, 538 10 of 14

(2010, p. 4) referred to the ‘dialogical nature’ of ethnographic writing and fieldwork, as theyremembered texts such as Crapanzano’s Tuhami (Crapanzano 1980) or Rabinow’s Reflectionson Fieldwork in Morocco (Rabinow 2007). I read them as meaning that the self is not stableon the field; needless to say, the self might not be stable anywhere, not just on the field, andmight need a number of resources to produce a semblance of stability. Alpa Shah (2017) alsocalled ethnographic research “dialectical”, and “participant observation” a “revolutionarypraxis” (Shah 2017, p. 47). Shah reminded us that those who see ethnographic researchfrom the outside, as activists or as members of cognate disciplines, might see the potentialof anthropology as producing deeply detailed case studies. However, that is not the onlyaim of ethnographic research. Shah wrote:

Participant observation is potentially revolutionary because it forces one to ques-tion one’s theoretical presuppositions about the world by an intimate long-termengagement with, and participation in, the lives of strangers. It makes us rec-ognize that our theoretical conceptions of the world come from a particularhistorical, social, and spatial location. (Shah 2017, p. 49)

And on the key components of participant observation:

Participant observation centers a long-term intimate engagement with a groupof people that were once strangers to us in order to know and experience theworld through their perspectives and actions in as holistic a way as possible. Forshort, I will refer to these four core aspects that are the basis of participationobservation as long duration (long-term engagement), revealing social relationsof a group of people (understanding a group of people and their social processes),holism (studying all aspects of social life, marking its fundamental democracy),and the dialectical relationship between intimacy and estrangement (befriendingstrangers). (Shah 2017, p. 51)

I wish to draw out this tussle in the journey of participant observation between‘intimacy’ and ‘estrangement’.

The assumption in the discussion on the role ethnography in anthropology (in the2017 HAU Special Issue) and Shah’s comments are that the intimacy to be struck is with thecommunity. In my case, I find that the first intimacy I have struck is with the organizingprinciple of the geography of Braj—the Godhead Krishna. So, like Paul Stoller, I believe themagic. I had arrived in Vrindavan primarily in search of Krishna’s presence. Now that Ibelieve in Krishna, especially that he exists on this sacred geography, my relationship withthe space and its people activates as a devotee. I hustle in the crowd with other devotees,in a competitive spirit, to get a longer, more private Darshan. What happens if you come tothe field having shared in a fundamental truth-claim of that community—the belief in thesacrality of the geography, in the endless reality of Krishna and his presence in the sacredland? Then you cannot participate in a ritual or sing-song event as an ethnographic event.You are too busy tasting the truth to watch patiently another’s tasting. Can you savor foodwhile eating and simultaneously watch others eat? You can watch others eat while eatingyour own food if you are not primarily interested in the eating. I am primarily immersedin accessing the truth of Krishna’s presence on this land. I end up following my ownemotional journey that detects its presence, which diverts my attention from watching anddoing things with the community. The ethnographer, following this logic, must necessarilyfollow her participant observation path with a certain detachment from the fundamentaltruths of the community. I usually do not see the heaving crowd of Vrindavan as researchsubjects, I see them as fellow consumers of the elixir. Then again, I see them as subjects ofmy research, when I am made deeply uncomfortable by the powers of the crowd, cautiouslywalking along the cobbled paths of Vrindavan, clutching at my cloth bag.

Michael D. Jackson wrote on the truth claims of divination rituals in Sierra Leone:

I maintain that Kuranko beliefs in divination are of the same order: quiescentmost of the time, activated in crisis, but having notable or intrinsic truth valuesthat can be defined outside of contexts of use. Second, beliefs are in most cultures

Religions 2022, 13, 538 11 of 14

often simulated or feigned, and the strength of commitment is highly variable,yet this does not necessarily undermine the potential utility and efficacy ofthe beliefs. In other words, the relationship between the espoused or manifestbelief (dogma) and individual experience is indeterminate. We cannot inferthe experience from the belief or vice versa with complete certainty. Third, toinvestigate beliefs or “belief systems” apart from actual human activity is absurd.(Jackson 2013, pp. 46–47)

My belief, and that of the other Krishna-worshippers, is contextual—I admit. However,Jackson watched the arrangement of pebbles by diviners to foretell the future in the capacityof the researcher of belief. Watching the dancing and singing masses of Vrindavan is noteasy for me to do from the epistemic distance practiced by Jackson. I watch the heavingpublic of Vrindavan, simultaneously experiencing an inward euphoria that propels meto cry.

I concede to Jackson that like our truths, their truths are contingent. Yes, like otherdevotees, I do not contemplate its implications when I go to a doctor or pay my taxes. Iam able to weed out the various actors in Vrindavan who try to manipulate my faith toget me to follow this or that sect or pay money at the temples. However, the finality andclarity of belief mark my straddling of the worlds of knowledge-making, universities andthe sacred geography of the Braj region. So, to that extent my truth and supposedly, theirtruth of faith is not contingent.

7. Pendulum of Being

I wish to mark emphatically the duality of my devotee–ethnographer status. Theexperience of the presence of the Godhead marks a place for large numbers of Krishna-worshippers. This interaction with divinity, through Darshan, is scarcely mediated bythe authority of religious leaders. This place of direct conversations and invocations ofdivinity play a significant role in the life of the devotee. This register of the extremelypublic yet private practice of seeking out divinity in a shrine is not something ethnographycan easily capture.

If the ethnographer experiences the same truth that the worshipping community, theyare studying, are accessing in their act of worship, it must automatically mean that theethnographer is undergoing a transformation of the self through immersion in this setof truths. This would make doing what is traditionally called ‘participant observation’difficult. I am, unlike Paul Stoller, not accessing the truth paradigm of the communityof Vaishnavas through participation in the authoritative hierarchy of the community, thatis, through the tutelage of a shaman or priest. I came to Vrindavan, already a convert.This conversion is indeed conflicted, as I try to leave behind my secular credentials andwalk a tightrope towards faith in my physical journey to Vrindavan. My difficulty infinding fellowship with the various Vaishnava communities that I encountered in the sacredgeography of Vrindavan, unfolds through my urbane, secular persona and associateddiscomfort about vegetarianism, ethnonationalism, the rise of the Hindu right politicalfactions and so on. However, as a devotee, in a Krishna temple, I am one among a milliondevotees competing for a private audience with the Godhead. There is no opportunity forparticipant observation here, I conclude. I wade through crowds, watching sandalwoodpaste marks on the bodies of devotees, merge with the chanting voices, and observe theminutiae of this process of collective worship. The worship is of a collective nature if seenfrom the outside, and yet, it carries a private, individuated journey for every devotee.

My ethnographic notes would say very different things if I was not simultaneouslyworshipping the Godhead Krishna, actively trying to immerse in a complex process ofself-surrender in the practice of Bhakti. The truth-potential, if one begins to access it, is sooverwhelming that one must follow its diktat outside of the performance of insertion ofoneself in a theatre of social events concerning another. My secular discomfort with thetones of Hindu nationalism at the Arati on the banks of the Yamuna, my squeamishness andcautious steps through the crowds of Vrindavan—are all evidence of this partially successful

Religions 2022, 13, 538 12 of 14

act of surrender. I continue to worship Krishna but cannot withhold my difficulty in findingcomplete fellowship in the various communities that come to worship at Krishna’s altarin Vrindavan. Participant observation and religious devotion orchestrate a pendulum ofbeing within me. I offer this article as a troubled celebration of my research and practice ofVaishnavism, at the borders of the ethnographic agenda.

Funding: Faculty Research Grant, O P Jindal Global University, 2019–2020. Grant no. 004.

Institutional Review Board Statement: Research Ethics Review Board, O P Jindal Global Universitygranted clearance to this research in 2019.

Informed Consent Statement: Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments: The first phase of ethnographic research that resulted in this article was sup-ported by the O P Jindal Global University Faculty Research Grant (2019–2020). I am grateful for theopportunities to present versions of this material at the Liberalism and its Others workshop at O P JindalGlobal University (October 2019) and the East Coast regional meeting of the American Academyof Religion (April 2019), and the encouraging feedback at both venues. This feedback empoweredme to write in the autoethnographic mode. I remain grateful for comments on the manuscript, atvarious stages, to R Krishnaswamy. I would further like to thank the two anonymous reviewerswhose feedback greatly enriched the manuscript. Lastly, thanks are due to Sandeep Banerjee for hisrelentless intellectual and emotional support through this journey of search, research, and writing.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes1 The theorization of this original experience that led me to Vrindavan in search of a tangible attachment to Krishna, is beyond

the ambit of this paper. I have avoided theorizing dreams and dreamlike experiences here. On the anthropology of dreams, seegenerally, Mittermaier (2010).

2 I had had hallucinations before, but never had they been this vivid, and the presence of a God had never been this unambiguous.Psychology and psychoanalysis have sometimes paid attention to mystical/religious experience (see generally, (Meissner 1986;Lacan 1998), and within anthropology/sociology, see (Obeysekere 2012; Pandolfo 2019; Sosteric 2017)). In this conversation,Bhrigupati Singh’s comment on the encounter between anthropology and psychiatry from his fieldwork in collaboration withpsychiatrists in Delhi, is most significant (Singh 2017). Acknowledging the presence of such debates about religious/mysticalexperience within the psychological sciences, this article veers towards to experiential register, paying close attention to thequality of being in the earthly world, while intuiting the presence of other worlds within it.

3 An attempt at understanding this split subjectivity led to an autoethnographic poem (Majumder 2022). A version of thisparagraph is reproduced as the ethnographic note to the poem.

Is this article a work of autoethnography? It is, though only in part. I offer here a reading of my own subjectivity as it hasemerged through the governance of western medicine and religious studies of Bhakti. I offer here my witnessing of faith andfaith-based practice, while learning to practice faith myself. This simultaneity renders an ethnography that flips its character,over and over again. On autoethnography, see generally, (Ellis 2004; Ellis et al. 2011; Spry 2011). On production of diverse formsof narrative through ethnography, especially the “confessional tale”, see generally, (Van Maanen 2011).

4 For a detailed historical account of the Bhakti movement, see Hawley (2007), and on its archive of song and poetry, seeHawley (2015).

5 Although David Haberman refuted the Tirtha status of Braj (Haberman 1994, pp. 72–73), he said:

There is no need to search for a passageway out of this world, there is no need for radical change, for this veryworld is itself divine . . . Several Vaishnavas in Braj have told me that from philosophical perspective (Siddhant) thereis no difference between the image and any other thing in the material world; from this perspective all things arenondifferent, as everything is Krishna.

6 Central Reserve Police Force.7 Otherwise, spelt as Krsna. In the Encyclopaedia of Hinduism, Coleman defined Krsna (Coleman 2008) thus:

. . . Krsna is depicted in three major forms throughout his long and diverse history in Indian religions: (1) as thewarrior prince, Vasudeva and Madhava, advisor to the Papdavas in the Mahabharara battle and benevolent ruler ofDviiraku; (2) as the playful child and adolescent lover Gopala and Govinda in the Sanskrit Puranas and vernacularpoetry, celebrated throughout India in popular expressions of devotion; and (3) as the Supreme Lord, Narayana, Visnuand Bhagavan, who creates the entire cosmos and grants moksa (liberation) to those devotees who unconditionallyadore him.

Religions 2022, 13, 538 13 of 14

8 Scholars have variously discussed the experience of excess in the practice of Bhakti through historical biographies of saints suchas Mirabai and Andal (Venkatesan 2007; Sangari 1990; Hawley 2005).

9 See generally, Calhoun (1992).10 See generally, (Novetzke 2007; Novetzke 2017), on the history of public cultures of emancipation that rode on the waves of

Bhakti. Further, see the important work by Nusrat Chowdhury—the ethnography of crowds and political protest in contemporaryBangladesh (Chowdhury 2020). I found essays in the volume The Power of Religion in the Public Sphere (Butler 2011) to be animportant intervention in the specific question I am asking about the religious public. But these, including those of Judith Butlerand Jurgen Habermas (Butler 2011; Habermas 2011) do not unpack this register of public excess, the experience of excess in thepublic domain, and its role in the shaping of the individual self. These essays invoke the category of ‘religion’ in public spheredebates, but cannot seem to divorce from the assumed threat that religion poses to the stability of the democratic public. Seegenerally, Habermas (2006), religion’s survival as a category within the rights-based discourse of democracy and modernity.

11 See generally, Eck (1998).12 Elsewhere, I relate this ethnographic anecdote to unpack my own selective disbelief. I believe in Krishna’s presence in Vrindavan,

but I find the peacock-dancing story amusing, refusing to take it seriously (Majumder, forthcoming).13 I asked Sarbadhikary, in an interview about her book Place of Devotion, about the ‘critical faculty of intuition’ in imagining the

presence of Krishna in the everyday. Sarbadhikary responded: “I extend ideas of imagination developed by Edward Casey,when I try to think about its apodictic, eidetic capacities of manifesting reality. And I am mostly influenced by Merleau–Ponty inthinking about intuition as a mid-ground between cognition and perception. Simply, intuition as a process of making apparentestablishes an immediate sensory relation between the process of thought and the object of thinking” (Majumder 2019).

14 For a history of ISKCON’s travel to the West and return to India, see (Fahy 2020).15 Paul Stoller wrote about the varied writing genres in which ethnography can express itself (Stoller 2007). There have been debates

on insider/outsider problem in the ethnographic study of religion (especially, belief) (see generally, McCutcheon 1999). Thedifficulty of entering a sphere of belief, especially one that initiates the loosening of the tight reins of self-governance, is discussedby Jessica Johnson in her provocative ethnography Biblical Porn (Johnson 2018). Johnson writes of the ‘affective labor’ (Johnson2018, p. 9) as a form of biopower exerted over the believers, through an analysis of discomfort from the ethnographer who insertsherself into an economy of religious conviction harnessed by sexual sermons in Mark Driscoll’s Mars Hill Church. Johnson wouldhave written a different account of these church services that demand this ‘affective labor’ had she been an active believer herself.My partial discomfort is thus different from Johnson’s and is complicated by the fact that I insert myself in this domain with anactive desire to surrender to the domination of the Godhead Krishna, and walk in the fellowship of other believers. I want tosurrender entirely, and my secular, individuated self (so to speak) pulls me in some discomfort.

ReferencesBhargava, Rajeev. 1998. Secularism and Its Critics. Themes in Politics Series; Delhi: Oxford University Press.Bloch, Maurice. 2017. Anthropology is an odd subject: Studying from the outside and from the inside. HAU: Journal of Ethnographic

Theory 7: 33–43. [CrossRef]Borneman, John, and Abdellah Hammoudi. 2009. The Fieldwork Encounter, Experience, and the Making of Truth: An Introduction.

In Being There: The Fieldwork Encounter and the Making of Truth. Edited by John Borneman and Abdellah Hammoudi. Berkeley:University of California Press.

Brunt, Lodewijk. 2001. Into the Community. In Handbook of Ethnography. Edited by Paul Atkinson, Amanda Coffey, Sara Delamont,John Lofland and Lyn Lofland. New York: SAGE Publications Ltd., pp. 80–91. [CrossRef]

Butler, Judith. 2011. Is Judaism Zionism? In The Power of Religion in the Public Sphere. Edited by Eduardo Mendieta and Jonathan VanAntwerpen. New York: Columbia University Press.

Calhoun, Craig J. 1992. Habermas and the Public Sphere. Studies in Contemporary German Social Thought. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Chowdhury, Nusrat Sabina. 2020. Paradoxes of the Popular: Crowd Politics in Bangladesh. South Asia in Motion. Stanford: Stanford

University Press.Coleman, Tracy. 2008. Krsna. In Encyclopaedia of Hinduism. Edited by Denise Cush, Catherine Robinson and Michael York. Abingdon:

Routledge.Coleman, Tracy. 2011. Bhakti. In Oxford Bibliography on Hinduism. New York: Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]Collins, Peter, and Anselma Gallinat. 2010. The Ethnographic Self as Resource: Writing Memory and Experience into Ethnography. New York:

Berghahn Books.Crapanzano, Vincent. 1980. Tuhami, Portrait of a Moroccan. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.Durkheim, Emile. 2001. The Elementary Forms of Religious Life. Translated by Carol Cosman. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Eck, Diana L. 1998. Darsan: Seeing the Divine Image in India. New York: Columbia University Press.Ellis, Carolyn. 2004. The Ethnographic I: A Methodological Novel about Autoethnography. New York: The Altamira Press.Ellis, Carolyn, Tony E. Adams, and Arthur P. Bochner. 2011. Autoethnography: An Overview. Historical Social Research/Historische

Sozialforschung 36: 273–90.Fahy, John. 2020. Becoming Vaishnava in an Ideal Vedic City. Wyse Series in Social Anthropology; New York: Berghahn Books, Volume 9.Haberman, David. 1994. Journey through Twelve Forests: An Encounter with Krishna. London: Penguin Books.

Religions 2022, 13, 538 14 of 14

Habermas, Jurgen. 2006. Religion in the Public Sphere. European Journal of Philosophy 14: 1–25. [CrossRef]Habermas, Jurgen. 2011. “The Political”: Rational Meaning of a Questionable Inheritance of Political Theology. In The Power of Religion

in the Public Sphere. Edited by Eduardo Mendieta and Jonathan Van Antwerpen. New York: Columbia University Press.Hawley, John Stratton. 1983. Krishna, the Butter Thief. Princeton Legacy Library. Princeton: Princeton University Press.Hawley, John Stratton. 2005. Three Bhakti Voices: Mirabai, Surdas, and Kabir in Their Time and Ours. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.Hawley, John Stratton. 2007. Introduction. International Journal of Hindu Studies 11: 209–25. [CrossRef]Hawley, John Stratton. 2015. A Storm of Songs: India and the Idea of the Bhakti Movement. Cabmbridge: Harvard University Press.Holdrege, Barbara A. 2015. Bhakti and Embodiment: Fashioning Divine Bodies and Devotional Bodies in Krsna Bhakti. Routledge Series on

Hindu Studies; Abingdon: Routledge.Jackson, John L., Jr. 2010. On Ethnographic Sincerity. Current Anthropology 51: S279–S287. [CrossRef]Jackson, Michael D. 2013. Lifeworlds: Essays in Existential Anthropology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.Jaffrelot, Christophe. 2007. Hindu Nationalism: A Reader. Princeton: Princeton University Press.Johnson, Jessica. 2018. Biblical Porn: Affect, Labor, and Pastor Mark Driscoll’s Evangelical Empire. Durham: Duke University Press.Lacan, Jacques. 1998. The Seminar Book XX. Encore, on Feminine Sexuality, the Limits of Love and Knowledge (1972–1973). Translated by

Bruce Fink. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.Lambek, Michael. 2016. What is “Religion” for Anthropology? And What Has Anthropology Brought to “Religion”? In A Companion to

the Anthropology of Religion. Edited by Janice Boddy and Michael Lambek. Chicester: Wiley-Blackwell.Majumder, Atreyee. 2019. Making Krishna Apparent: Interrogating Intuitive Capacity through Gaudiya-Vaishnav practice in West

Bengal (Interview with Sukanya Sarbadhikary). RIC Journal, February 19. Available online: https://ricjournal.com/2019/02/19/making-krishna-apparent-interrogating-intuitive-capacity-through-gaudiya-vaishnav-practice-in-west-bengal/ (accessed on21 March 2022).

Majumder, Atreyee. 2022. Song of the Sweet Lord. Anthropology and Humanism. [CrossRef]Majumder, Atreyee. Forthcoming. Secularism and its Theological Interior: An Anthropologist’s demand on Faith. In Liberalism and Its

Encounters: Some Interdisciplinary Approaches. Edited by R. Krishnaswamy and Atreyee Majumder. New Delhi: Routledge.Mascaro, Juan. 2003. The Bhagavad Gita. New York: Penguin Books.McCutcheon, Russell T. 1999. The Insider/Outsider Problem in the Study of Religion: A Reader. Controversies in the Study of Religion.

London: Cassell.Meissner, W. W. 1986. Psychoanalysis and Religious Experience. New Haven: Yale University Press.Mittermaier, Amira. 2010. Dreams That Matter: Egyptian Landscapes of the Imagination. Oakland: University of California Press.Novetzke, Christian Lee. 2007. Bhakti and its Public. International Journal of Hindu Studies 11: 255–72. [CrossRef]Novetzke, Christian Lee. 2017. The Quotidian Revolution: Vernacularization, Religion, and the Premodern Public Sphere in India. New York:

Columbia University Press.Obeysekere, Gananath. 2012. The Awakened Ones: Phenomenology of Visionary Experience. New York: Columbia University Press.Pandolfo, Stefania. 2019. Knot of the Soul: Madness, Psychoanalysis, Islam. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.Pike, Kenneth L. 1999. Etic and Emic Standpoints for Description of Behavior. In The Insider/Outsider Problem in the Study of Religion:

A Reader. Edited by Russell McCutcheon. London: Cassell, pp. 28–36.Rabinow, Paul. 2007. Reflections on Fieldwork in Morocco. Berkeley: University of California Press.Sangari, Kumkum. 1990. Mirabai and the Spiritual Economy of Bhakti. Economic & Political Weekly 25: 1537–41.Sarbadhikary, Sukanya. 2015. Place of Devotion: Siting and Experiencing Divinity in Bengal-Vaishnavism. Oakland: University of California

Press.Sarbadhikary, Sukanya. 2018. The Body-Mind Challenge: Theology and phenomenology in Bengal-Vaishnavisms. Modern Asian Studies

52: 2080–108. [CrossRef]Shah, Alpa. 2017. Ethnography? Participant observation, a potentially revolutionary praxis. HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 7:

45–59. [CrossRef]Singh, Bhrigupati. 2017. An uncritical encounter between anthropology and psychiatry: AIIMS psychiatrists reading Affliction. Medicine

Anthropology Theory 4: 153–65.Sosteric, Mike. 2017. Mystical Experience and Global Revolution. Athens Journal of Social Sciences 5: 235–56. [CrossRef]Spry, Tami. 2011. Body, Paper, Stage: Writing and Performing Autoethnography. New York: Routledge.Stoller, Paul. 2007. Ethnography/Memoir/Imagination/Story. Anthropology & Humanism 32: 178–91.Stoller, Paul. 2016. Religion and the Truth of Being. In A Companion to the Anthropology of Religion. Edited by Janice Boddy and Michael

Lambek. Chicester: Wiley-Blackwell.Taylor, Charles. 2007. A Secular Age. Gifford Lectures, 1999. Cambridge: Belknap Press.Van Maanen, John. 2011. Tales of the Field: On Writing Ethnography, 2nd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.Venkatesan, Archana. 2007. A Woman’s Kind of Love: Female Longing in the Tamil Alvar Poetry. Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies 20:

16–24. [CrossRef]