Exploring farmer's knowledge as a source of information on past and present cultural landscapes

Transcript of Exploring farmer's knowledge as a source of information on past and present cultural landscapes

A

ldMtmtticsa©

K

1

h1pmkrEiit

0d

Landscape and Urban Planning 78 (2006) 334–343

Exploring farmer’s knowledge as a source of informationon past and present cultural landscapes

A case study from NW Spain

M. Silvia Calvo-Iglesias a,∗, Rafael Crecente-Maseda a, Urbano Fra-Paleo b

a Department of Agroforestry Engineering, Escola Politecnica Superior, University of Santiago de Compostela, 27002 Lugo, Spainb Department of Geography and Spatial Planning, University of Extremadura, Campus Universitario Caceres 10071, Spain

Received 27 August 2004; received in revised form 31 October 2005; accepted 24 November 2005Available online 26 January 2006

bstract

The primary goal of this research was to explore the potential of farmer’s knowledge as a source of information on the past and present culturalandscapes, focusing on the land-use system, the cultural heritage, and the farmer’s perception of landscape changes, from the 1950s to the presentay. For this purpose, 42 semi-structured interviews were conducted from a random sample of 10% of the villages in an area of the Northernountains of Galicia (NW Spain). As shown in farmers’ reports, the main crops in the 1950s were wheat or rye, potatoes or maize (only near

he coast) and turnips. Scrubland areas were an essential resource for pasture, litter, temporary crops and charcoal, whereas deciduous forest wasainly used as a source of wood for carpentry, firewood and litter. Agriculture was the main economic activity, whereas crafts and other activities in

he fisheries or forestry industry were secondary. Granaries, watermills and stone laundry basins were the most frequent elements of built heritagehat was mentioned in the interviews. Farmers were also comprehensively aware of the broad changes that occurred in the landscape. The results

ndicate that farmer’s knowledge is a valuable source of information for documenting past and present land-use practices, local cultural heritage andhanges in the landscape, all of which are helpful for the design of landscape-orientated policies. Moreover, observed ancestral cultural practices,uch as extensive grazing in scrubland areas, may be promoted as strategies for helping the sustainability of cultural landscapes in the study areand in other areas with similar characteristics.2006 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

ltural

dsm2

vsama

eywords: Farmer’s knowledge; Agricultural landscapes; Land-use system; Cu

. Introduction

Cultural landscapes are the result of the interaction betweenumans and nature (Stanner and Bourdeau, 1995; UNESCO,997; Council of Europe, 2000), bearing witness to past andresent relationships between human beings and their environ-ent. Landscapes are part of the European cultural heritage and

ey components of local, regional and national identities, asecognized by the European Landscape Convention (Council ofurope, 2000). The rural landscapes of Europe constitute the

mmediate daily surroundings of many people and directly orndirectly affect the quality of life of all Europeans. Besides,raditional rural landscapes are vital for the conservation of bio-

∗ Corresponding author. Tel.: +34 982 252231x23292; fax: +34 982 285925.E-mail address: [email protected] (M.S. Calvo-Iglesias).

aJsdl

N

169-2046/$ – see front matter © 2006 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.oi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2005.11.003

heritage; Landscape change; Landscape management

iversity (Fjellstad and Dramstad, 1999; Antrop, 2004), and aource of information concerning the application of sustainableanagement techniques (Stanner and Bourdeau, 1995; Antrop,

004).Increasingly, however, their ecological, aesthetic and cultural

alues are threatened by processes of a rapid, large-scale nature,uch as sweeping changes in agricultural practices, the decline ofgricultural activity in some regions, urban sprawl, the develop-ent of road and rail networks, as well as the pressure of tourism

nd leisure activities (Meeus et al., 1990; Meeus, 1995; Stannernd Bourdeau, 1995; Palang et al., 1998; Vos and Meekes, 1999;ongman, 2002; Van Eetvelde and Antrop, 2004). Given thisituation, strategies for conservation and management must be

eveloped in order to ensure that these values are not needlesslyost.This research was carried out in bocage landscape of theorthern Mountains of Galicia (NW Spain). Our primary aim

e and

woibfp

2

2

(ioFtiootsoiV2

sathtr

ttTk7a2ltbpt

2

ioIk(atKesta2

M.S. Calvo-Iglesias et al. / Landscap

as to explore the potential of farmer’s knowledge as a sourcef information on the past and present cultural landscapes focus-ng on the cultural heritage (crafts, built heritage and fieldoundaries), the land-use system and cultural practices, and thearmer’s perception of landscape change, from the 1950s to theresent day.

. Materials and methods

.1. The study area

The study area is located in the Northern Mountains of GaliciaNW Spain) that were described by Bouhier (1979) as possess-ng a characteristic bocage landscape. Facing the western Bayf Biscay (Fig. 1), it covers 370.7 km2 of the ranges Serra daaladoira, Serra da Coriscada, Serra da Carba, Serra do Xis-

ral and Montes do Buio, ranging in altitude from sea level atts northern limit (1–12 km from the sea) to 1037 m, with 70%f its area between 300 and 600 m above sea level. About 50%f the area has slopes higher than 25% and 10% slopes higherhan 50%. In terms of land cover 50.8% is woodland, 33.5%crubland and 15.7% holds a mosaic of plots devoted to pasturer crops (SITGA, 2000). It features 431 small villages belong-ng to 32 parishes in five municipalities (Vicedo, Ourol, Muras,iveiro and Xove) with a population of 827 inhabitants (INE,003).

In the study area, major changes in landscape due to the inten-ification of agriculture, happened in the 1970s, while in otherreas of Galicia the changes mainly occurred in the 1950s. Addi-

ionally, one of the most salient changes in the agrarian practicesas been the large-scale introduction of Eucalyptus sp. planta-ions, which currently cover about 40% of the study area. Moreecently, the landscape has also been modified by the installa-22

a

Fig. 1. Study area, showing the location

Urban Planning 78 (2006) 334–343 335

ion of wind farms, along the range crests, even in the areashat have been included in the Natura 2000 network proposal.he main priority habitats present in the study area are blan-et bogs and raised bogs (with Nature 2000 codes 7130 and110, respectively), as well as European dry heaths and temper-te Atlantic wet heaths with E. ciliaris and E. tetralix (Natura000 codes 4030 and 4020, respectively). The alterations in theandscape have also been helped by the rapid depopulation ofhe area – a loss of 73% of the inhabitants since 1960 – causedy out-migration to nearby small towns resulting in an agingopulation; and by the lack of any landscape planning policy inhe Galicia region.

.2. A review of methods

The use of interviewing methods is a long-standing practicen social science, and is increasingly being used in the fieldf environmental management to document local knowledge.t has proved especially valuable in regard to local inhabitants’nowledge of local soils, their potential and their managementDi Mauro, 2003; Cools et al., 2003; Grossman, 2003; Desbiez etl., 2004; Alexander and Kidd, 2000; Ali, 2003) and in relationo local vegetation and its use and management (Lykke, 2000;appelle et al., 2000; Dhillion and Gustad, 2004; Mc Donnald

t al., 2003). Also interviews began to be employed in landscapetudies investigating the relationships between the landscape andhe people (O’Rourke, 2005; Kruger, 2005), landscape man-gement (Cudlınova et al., 1999; Pavlikakis and Tsihrintzis,006) and changes in landscapes (Primdahl, 1999; Ellis et al.,

000; Bender et al., 2004; Iiyama et al., 2005; Nikodemus et al.,005).Although local knowledge has gained recognition as a valu-ble source of information in order to understand changes in the

of the villages that were visited.

3 e and

lcatmkvtWitaZ22ae2toesTwt

2

moet

ajpbwtatits

m(tirpdtIma

eesotu

iptmyatiawotat

ai1

(ilistcrttiuiottcSdt(

ataaS

36 M.S. Calvo-Iglesias et al. / Landscap

andscape with a view to evaluating the viability of conservingertain features and identifying management techniques that areppropriate for that purpose (Antrop, 2004), the recent litera-ure in this field has exhibited a marked lack of clarity as to the

ethods that have been employed in accessing the informants’nowledge (Davis and Wagner, 2003). The main aspects of inter-iewing include the selection of informants, the sample size,he format of interview or questionnaire employed (Davis and

agner, 2003), and the use of other sources to corroborate thenformants’ reports (Robertson and Mc Gee, 2003). As regardso the format of the interview, most of the studies reviewedppear to have used semi-structured interviews (Lykke, 2000;urayk et al., 2001; Nyeko et al., 2002; Peroni and Hanazaki,002; Di Mauro, 2003; Grossman, 2003; Mc Donnald et al.,003; Desbiez et al., 2004; O’Rourke, 2005), because the resultsre easier to process than those from unstructured interviews,mployed in other studies (Cudlınova et al., 1999; Mendez et al.,001; Robertson and Mc Gee, 2003). This is particularly impor-ant when informants’ reports are compared to information fromther sources (historic archives, aerial photographs, inventories,tc.) so as to reduce errors and attain to a fuller overall under-tanding of the system studied (Robertson and Mc Gee, 2003).aken these advantages into account, a semi-structured formatas also used for facilitating data aggregation and analysis of

he results from the whole set of interviews.

.3. Sampling and instrument

Since the anthropogenic influence on the landscape is mostarked in the neighbourhood of the villages, it was decided to

btain information concerning the area lying within 500 m ofach settlement (hereinafter referred to as zones of influence),hrough a random sample of the 431 villages of the study area.

In view of the strong social cohesion in the study area, it wasssumed that it would be sufficient to obtain information fromust one informant in each sample site, although in practice therincipal informant was in certain cases assisted by other mem-ers of his or her family. The initial sample (see Section 3.1ith regard to its modification) comprised 43 villages (10% of

he total), whose distribution is shown in Fig. 1. Upon arrivingt each settlement, the interviewer approached the first inhabi-ant encountered within the zone of influence of the settlement,ntroduced herself, outlined the study, inquired as to the poten-ial informant’s willingness to be interviewed and assessed theiruitability for the role of informant.

The interviews were carried out bearing in mind the recom-endations of Thompson (1978) and Hammer and Wildavsky

1994) as to the way of establishing contact with the informant,he place where the interview takes place, the neutral question-ng and the recording procedure. Special care was taken withegard to the presentation and description of the study to therospective informant, and to encouraging informants’ confi-ence by interviewing them while they were outdoors (usually

hey were at work), and if possible in the presence of others.n fact, it was deemed that in most cases interviewing infor-ants outdoors would be psychologically advantageous – byvoiding any mistrust of an interviewer apparently keen on

icaq

Urban Planning 78 (2006) 334–343

ntering the informant’s home – and would also facilitate theliciting of information and opinions on the surrounding land-cape. Assurances of informant anonymity were given; and inrder to encourage them and put them at ease, a few examples ofhe questions to be answered were mentioned, and the intendedse of the information provided was sketched.

Informant’s were required to have lived most of their livesn the village where they were encountered, to have had closeersonal acquaintance with the agricultural practices during thisime, and to be able to respond to questions about the settle-

ent in the 1950s, so that they were required to be over 50ears of age (except in the case of younger relatives assistingprincipal informant). They also had to be able to remember

he days of slash-and-burn cultivation of scrubland areas. If thenhabitant first encountered proved unwilling or unable to acts an informant, he or she was asked to recommend someoneho would be willing and able to cooperate. The strategy ofbtaining information from the first inhabitant encountered inhe zone of influence of each settlement was adopted as efficientnd practical because, given the demographic characteristics ofhe study area, most of the inhabitants were valid informants.

We used a semi-structured format, which keeps interviewss homogeneous as possible and facilitates aggregation of thenformation obtained in the whole set of interviews (Thompson,978; Howarth, 1998).

Interviews comprised five sections: metadata on the interviewsite identification, duration of interview, reliability rating ofnformant, etc.), cultural heritage, traditional (1950s) and presentand-use system (2003, when the interviews were conducted),nformant’ profile (farm characteristics, main income sources,ubsidies received), and the informant’s perception of the fac-ors affecting the local landscape, including farmers’ role in itsonservation. Topics were not necessarily presented in order. Ifelevant topics cropped up “in the wrong order” in the course ofhe informant’s discourse, they were dealt with at that time, andopics related to personal opinion, or those concerning sensitivessues such as enclosure or slash-and-burn, were generally leftntil a certain degree of confidence had been established betweennterviewer and informant. Sections one to four consisted ofpen-ended questions such as which were the main crops inhe village, and closed questions in which the respondents hado choose among a number of given answers. Section five,oncerning informant’s opinion, consisted of closed questions.ection two, related to the past and present land-use system, wasrawn up bearing in mind the descriptions of traditional prac-ices in the Galicia region given by Bouhier (1979) and Balboa1990).

The interviews were carried out during the summer of 2003nd lasted between 30 and 60 min. They were all conducted andranscribed by the same interviewer, who took notes during andfter the interview. Interviews were coded in a spreadsheet andnalysed by the interviewer using Microsoft Excel® software.o as to ensure homogeneity and minimize any bias in cod-

ng and interpreting the interviews, open-ended questions wereoded according to the number of responses in the interviewsnd interpreted as percentages of total responses, while closeduestions were also interpreted as frequencies (Fig. 2).

M.S. Calvo-Iglesias et al. / Landscape and Urban Planning 78 (2006) 334–343 337

re of

3

3

i1tibtbfa

3

owTeoa

Awfopwi

bv7titaimsoc

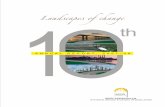

Fig. 2. The structu

. Results

.1. Informants’ profile

In one of the villages sampled it proved impossible to findnformants, resulting in a sample size of 42. Of the 42 informants,9 were men and 23 were women. Their ages ranged from 55o 95 years, most (86%) were older than 60 years. Most of thenformants (67%) were farmers, living in small farms, breedingoth dairy and beef cattle for the market and growing crops forheir own-consumption. There were also farmers that had onlyeef cattle (26%), while 5% of the informants were part-timearmers, and 2% of the informants had both dairy and beef cattlend sell a small portion of their crop production (2%).

.2. Local cultural heritage

Informants reported that in the 1950s most of the inhabitantsf the study area were engaged in agriculture, and only someere carpenters, millers, blacksmiths, tailors and shoemakers.

here were also fishermen in the coastal areas as well as workersmployed in the building industry, in forestry, in the quartz minesf A Silvarosa (Viveiro), and in the hydraulic power station andssociated small manufacturing complex at Chavın (Viveiro).lodi

the questionnaire.

lthough flax was grown at 23 of the 42 villages in the sample,eaving was only occasionally mentioned, as it was not used

or producing goods for sale. Where crafts such as clog-makingr ironworking had been pursued, information was generallyrovided in regard to the specific practices. For instance, theood used for clog-making was birch, while the charcoal used

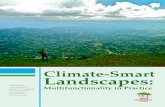

n the smith’s forge was made of chestnut, oak or heath.The most frequently encountered extant components of the

uilt heritage of the study area were horreos (small, well-entilated granaries standing on pillars), which were present in4% of the villages sampled; and watermills were cited in 64% ofhe sample sites (Fig. 3). Both testify to the importance of cerealsn the former farming system. In the smaller villages informa-ion was also obtained as to their owners, state of conservation,nd exact location in the case of the watermills as horreos arenvariably located by the owner’s dwelling. Horreos and water-

ills are followed in frequency by lavadeiros or public open-airtone built laundries fed with running freshwater (cited in 55%f the villages), cruceiros or stone crosses (41%), and churches,hapels and hermitages (36%). Many informants mentioned the

oss of stone crosses since the 1950s through deterioration, theftr roadwork; some even mentioned losses that had taken placeuring the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939). Two villages, hold-ng the local parish church, had marketplaces and open-air dance338 M.S. Calvo-Iglesias et al. / Landscape and

F

fliecit

ol9wto

r(–bba

aair

3

ciim1

swlaalhhc

3

pcwt(r

ig. 3. Percentages of villages featuring nowadays certain items of built heritage.

oors. The massive emigration from Galicia to South American the late 19th and early 20th centuries is reflected in the pres-nce of casas de indiano (i.e. large, relatively opulent housesonstructed by enriched returning emigrants, often incorporat-ng features reminiscent of the architecture or flora of the placeso which they had emigrated), cited in two villages.

Essential to a bocage landscape are the hedgerows, and rowsf trees or walls surrounding its fields. Although in 71% of vil-ages the progressive introduction of wire fencing was apparent,8% still featured traditional field boundaries: dry-stone wallsere reported in 71%, chantos (walls consisting of adjacent ver-

ical stone slabs) in 14%, stone-and-earth walls in 41%, and rowsf trees and hedgerows in 67%.

In all the cases in which hedgerows and rows of trees wereeported to have existed, they included trees, mainly willowSalix spp.) and cherry laurel (Prunus laurocerasus). Willows

employed for their easy rooting and the use of their shoots forasket making – usually grew in hedgerows around meadows,ut were also to be found between cultivated plots. Cherry laurel,densely-foliaged evergreen, was generally used as a windbreak(

aa

Fig. 4. Evolution of the main crop associations

Urban Planning 78 (2006) 334–343

round dwellings, vegetable plots and threshing floors (thoughlso as firewood). The loss of walls, rows of trees and hedgerowsn recent times, was reported to have come about primarily as aesult of road-widening.

.3. Traditional and present land-use system

Until recent decades, a key factor in the configuration of theultural landscapes of Galicia was the land-use system, prevail-ng from medieval times to the first quarter of the 20th century,n a framework of a privilege regime that was based on the pay-

ent of taxes to the landlords for the use of the land (Villares,998).

In 81% of the villages, informants reported that in the 1950scrubland covered large areas surrounding the villages, andoodland a much smaller proportion. The coverage of arable

and and meadows varied considerably among villages. Valleysnd lower-lying areas had relatively less coverage of meadowsnd more cultivated land, while the reverse was true of villagesocated at higher altitudes on steeper slopes. Today, this situationas changed, much scrubland – and even meadows and fields –as been afforested, although in upland villages, scrub can stillover up to 50% of the sample unit.

.3.1. Use of the ager or permanent croplandAccording to the informants’ reports, crop rotation was still a

revailing practice in the 1950s in such a way as to obtain threerops every 2 years. Near the coast, the usual alternating cropsere wheat or rye, potatoes or maize, and turnips; whereas fur-

her inland, the maize option was omitted. According to Bouhier1979), these cycles are the same as those shown by historicalecords to have predominated in the 18th and 19th centuries

Fig. 4).Since the 1950s, crop rotation has declined dramatically,s a result of the increasing predominance of cattle farmingnd the concomitant cultivation of artificial ryegrass meadows.

of the rotation system in the study area.

M.S. Calvo-Iglesias et al. / Landscape and

Fa

Hgoth

3

rlmacwfi

aafmhr

3

ftmtSDaaswwlcrs

carotst

tt(gfiswmvtap

aimt

3t

torhait

ftsov

3Tweatl

o

ig. 5. Percentage of villages in which informants reported certain uses of scrubnd woodland in the 1950s.

owever, due to attachment to tradition, crop rotation and cereal-rowing are nevertheless still practiced on a small scale in a thirdf the villages investigated, where other traditional farming prac-ices are also perpetuated, such as the care and exploitation ofedgerow trees.

.3.2. Use of the silva or woodland areasChestnut woods were reported to have played an important

ole in the traditional agrarian economy of 73% of the vil-ages investigated, and oak woods in 71%. Chestnut woods were

ainly exploited for the fruit, but were also reportedly used assource of wood for carpentry (48% of cases), firewood (21%),harcoal (19%), and litter for livestock (31%) (Fig. 5). Oakoods were a source of wood for carpentry (in 62% of cases),rewood (74%), and litter (45%).

Today, chestnut woods have almost disappeared in the studyrea. About a third of the informants attributed their disappear-nce to ink disease, but they were also reported to have beenelled for replacement by fast-growing species (first pines, andore recently Eucalyptus). Although most of the oak woods

ave disappeared, only three informants mentioned felling andeplacement as the cause of the disappearance of oak woods.

.3.3. Use of the saltus or scrubland areasThe zone of influence of all the villages investigated had

ormerly scrubland, developed in cycles of slash-and-burn, cul-ivation, and back to scrub. Ninety-eight percentage of the infor-

ants referred to this practice – which goes back to mediaevalimes (Bouhier, 1979; Balboa, 1990; Rıos Rodrıguez, 1997;aavedra, 1985) – as still having been very common in the 1950s.epending on the phase of the cycle, these areas provided cere-

ls, pasture and litter, and in some villages (38%) white heathernd furze were also used to make charcoal (Fig. 5). Once thecrub had been cut, it was left to dry for several months andas burnt during the summer so that its ashes acted as fertilizerhen cereal was sown the following autumn. In 60% of the vil-

ages the cereal sown was reported to have been rye, in 29% aombination of rye and wheat, in 10% rye and oats, and in 2%ye, wheat and oats. In 36% of villages, furze was sown at theame time as cereal was. Once cultivation of the cleared area had

efmf

Urban Planning 78 (2006) 334–343 339

eased (after 1 or 2 years), it became a grazing area for horsesnd, later on, other livestock. About half the informants alsoeported the use of scrub burning to clear land for pasture; halff these cases stated to have been performed at the end of win-er, and the other half “whenever it was necessary” or “when thecrub burnt well”, which suggests that it was carried out duringhe summer.

According to the informants, the livestock that was bred inhe 1950s comprised cows (2–10 per farm), horses (in 76% ofhe villages sampled), sheep (in 83%), goats (in 62%) and pigsa few per farm). Cattle were usually taken in the morning toraze tethered on the narrow strips of land dividing cultivatedelds, and in the afternoon they were led out to graze freely in thealtus. This is still the practice of numerous “residual” farmersho retain just one cow. Almost two-thirds of the informantsentioned how the grazing animals were watched over: in some

illages, each farmer only looked after his own animals; in some,he villagers took turns to guard all the animals of the settlement;nd in others, the neighbours jointly hired a herdsman for thisurpose.

Traditionally, a significant amount of the horses in the studyrea lived wild in the hills, being rounded up annually for brand-ng of yearlings and sale (Saavedra, 1985). This practice is still

aintained in a few places, such as Candaoso (Viveiro), wherehe annual round-up has become an important tourist attraction.

.4. Informants’ perceptions of changes in the landscape,heir causes, and the importance of agriculture

Most informants (72%) regarded the maintenance of agricul-ural activity in the region as important, 5% regarded it as onlyf moderate importance, and 24% failed to give an opinion. Theeasons given included the importance of high-quality food forealth, and the need to prevent the consequences of agriculturalbandonment, such as environmental deterioration and the riskncrease of wildfires. However, no informant was positive as tohe likelihood of agricultural activity being maintained.

Most informants (83%) were very much in favour of subsidiesor the conservation of cultural heritage and traditional agricul-ural practices. They nevertheless judged that the provision ofuch subsidies would not suffice to keep younger generationsn the land, given the poor prospects of agriculture and thatirtually any other occupation afforded a better quality of life.

Half the informants were against afforestation of farmland,6% were in favour, and 14% failed to give an opinion (Fig. 6).he main reasons argued for opposing afforestation were itsasting the potential of agricultural land, and the effects of for-

st on adjacent dwellings and fields. Arguments in favour offforestation were the provision of income in return for very lit-le effort, and that afforestation was better than just letting theand run wild as a result of the declining population.

Land consolidation was favoured by 62% of informants andpposed by 19% (Fig. 6). Those in favour appealed to the

xpected increase in croft profitability, while those against pre-erred their present situation to the result of a reallotment thatight be inequitable because of differences in land quality. Inact, many of those in favour of consolidation spontaneously

340 M.S. Calvo-Iglesias et al. / Landscape and

rcc

oowhwpecFthm

4

oikcvitwh

itbviatsmmp

ribtat2lacttoiWdsellaot1

fmdistaptpi

setttmabatwe

we

Fig. 6. Attitudes to landscape change factors, percentage of informants.

emarked that their settlement was not well suited for its appli-ation. None of the informants mentioned the effects of landonsolidation on the environment and landscape.

Some 33% of informants approved of the recent constructionf wind farms, 26% disapproved of it, and 41% were undecidedr failed to give an opinion (Fig. 6). Those in favour asserted thatind farms produce “clean” power and approved their use onills that “weren’t any good for anything”. Arguments againstind farms included there being virtually no benefit to the localopulation, the noise made by the windmills, and the healthffects of associated high-voltage lines. Only one informantomplained of the impact of wind farms on the visual landscape.ailure to give an opinion for or against was often justified by

he fact that the informant had no land on which a wind farmad been or was going to be installed. It should also be kept inind that wind farms are a very recent feature of the study area.

. Discussion

Regarding the results of this study, the profile characteristicsf the informants and their answers on the main economic activ-ties and crafts show that, in the 1950s, agriculture still played aey role in the economics of the study area. The importance ofrafts and other activities, such as those related to industry, wasariable at the local level, so it was not possible to infer theirnfluence to the whole study area. Nevertheless, according tohe answers, crafts seemed to be complementary to agriculture,hereas the impact of the industry in the study area seemed toave influenced the areas nearby.

From the information provided by the farmers, we couldnfer the importance in the study area of specific elements ofhe cultural heritage, such as field boundaries or stone laundryasins, granaries (or horreos) and watermills, reflecting rele-ant functions for the agrarian community. However, with thisnformation it is not possible to generalize and estimate suchspects as the richness of cultural heritage of the study area, ashe frequency and type of cultural heritage elements that were

tudied varied constantly from place to place, according to theany variables of their historic, socio-economic (inhabitants,igration flow) and environmental (areas with low production,resence of rivers) framework.

Tasm

Urban Planning 78 (2006) 334–343

Assuming informants’ answers on the land-use system asepresentative of the whole study area due to their homogeneity,n this work the continuity until recent times was observed toe of the traditional land-use system of the Galicia region. Thisraditional land-use system was mainly based on the multiplend integral use of the landscape, which was promoted duringhe Medieval Ages by monastic orders and perpetuated until the0th century through a privilege regime (Villares, 1998). In thisand-use system, scrubland areas in Galicia had high value asreas that could support livestock, provide firewood and char-oal, provide periodic cereal production and be a source of litterhat was essential for producing the manure needed to fertilizehe cropland (Bouhier, 1979; Balboa, 1990). The importancef scrubland areas in agricultural landscapes throughout historys a common feature shared by Atlantic Europe according to

ebb (1998) and Haaland (2002). Although there were someifferences in land-use and cultural practices carried out in thecrubland areas – due to the floristic diversity and to differentnvironmental contexts found along the Atlantic facade – scrub-and was a key element of their land-use systems for support ofivestock feeding and provision of fertilizers for the croplandreas. Today, in a few areas – such as Galicia – the persistencef heathland and its traditional practices is still present but tradi-ional forms of land-use have died out almost everywhere (Webb,998).

At a local level, it was observed that the land-use systemollowed the general pattern, with a distribution of land on per-anent cropland areas, woodland areas and scrubland areas, as

escribed by Bouhier (1979). However, nuances were observedn this distribution, according to environmental characteristics,uch as slope and altitude, which constraint the number of areashat are suitable for use as cropland. Farmers’ knowledge hasllowed verification that, in the 1950s, scrubland areas stilllayed a key role in the land-use system of the study area. Onhe other hand, they have confirmed the persistence, until theresent day, of some of the ancestral uses of the scrubland – thats, extensive grazing and clearing for litter.

Farmers’ knowledge has also shown to be useful for under-tanding changes that occur in the landscape at a local level,specially the directions of change in land-use and cultural prac-ices. Nevertheless, this information cannot be extrapolated tohe whole study area, because changes in the landscape are due tohe existence of diverse driving forces from different levels but

ainly from a local level. On the other hand, the informants’ttitude towards the landscape driving forces studied cannote generalized as they only reflect the opinion of part of thegrarian community. In spite of this, their pessimism regardinghe continuity of agricultural activity by new generations, evenith economic support, is pointing towards important socio-

conomic and environmental issues.An unexpected difficulty that arose during all the interviews

as the abstract nature of the concept of ‘landscape’ for the farm-rs, who seemed to more closely identify with the term “land”.

his made it necessary to seek opinions about the prospects ofgriculture for the management of the land in the informant’settlement, rather than about the importance of agriculture foranagement of the landscape. Their opinions about the effectse and

obtst

itdfgltetofd

lait1iRaobtfilsbocpe

csspiyaaptro(oima

Hki(oaTtirwiaftfpEtat

eltabtliofhitcmImhTao

rmlfhisit

M.S. Calvo-Iglesias et al. / Landscap

f land consolidation and afforestation programmes were wellased, whereas their arguments regarding wind farms showedhat many informants had very limited information about theocial, economic and environmental effects of this activity, dueo their recent development in the area.

Although all informants were clear about the changes in farm-ng practices that had occurred since the 1950s, fewer articulatedheir views regarding the causes of these changes. Also, pre-ictably, their perception of their surroundings was basicallyunctional: they valued agriculture highly (while expressingrave doubts about its future viability in the area), but showedittle awareness or concern for the environmental, or for cul-ural or aesthetic aspects of the landscape. Thus, opposition isxpressed towards changes in the landscape that affect agricul-ure, such as afforestation, but not towards those that have nobvious impact on agriculture, such as the introduction of windarms, or changes that actually favour agriculture, such as thoseeriving from land consolidation.

However, farmers’ responses showing their attitude towardsandscape change factors did not always correspond to theirctions. Despite their attitude, afforestation of agricultural lands an important trend in the study area, whereas land consolida-ion is not. In fact, land consolidation has been carried out only inout of the 32 parishes of the study area, despite all the economic

ncentives that have been given by the Regional Government.egarding the afforestation, some of the informants that weregainst the afforestation of agricultural land, when asked, rec-gnized that they might need to have afforested agricultural landecause they were forced by “circumstances”, such as the needo obtain a higher income instead of abandoning the land, or theact that other neighbours would have afforested the surround-ng plots. The reason for the apparent contradiction towardsand consolidation could be due to cultural factors—mainly thetrong attachment to land (to their “roots”) that is manifestedy the Galician farmer’s community. This could explain theirpposition to “lose” the plots that they value highly, in the pro-ess of exchanging land for assembling and increasing the farmroperty, despite their common agreement in the technical andconomic benefits of having their farm in a single, large plot.

Regarding the value of farmers’ knowledge for studyingultural landscapes, examples from the international literaturetress the value of local knowledge and its usefulness in land-cape planning and management. For example, Kruger (2005)resents a set of studies that were carried out in Alaska deal-ng with local knowledge and resource management to anal-se the interconnections between social and cultural changend resource management. She shows the influence of culturalspects, such as clan membership, in the interactions betweeneople and the natural resources. She also shows the impor-ance of the knowledge of traditional subsistence activity foresources management and the influence in society and resourcesf other activities, mainly tourism and timber harvest. O’Rourke2005) analyses the close relationship that has existed through-

ut history between the people and the landscape of the Burrenn Ireland, with important implications for landscape manage-ent, showing that nature conservation policies should not onlyddress the environment or the landscape but also the people.

sctp

Urban Planning 78 (2006) 334–343 341

er work evokes questions such as how to ascertain who are theey landscape actors, or as she posed the question “what her-tage do we want to preserve and for whom?”. Nikodemus et al.2005) interviewed local communities in the Vidzeme Uplandsf Latvia to analyse social structure and to examine people’sttitudes to their present situation and aspirations for the future.his allowed them to identify social aspects that may influence

he future directions of landscape change. Iiyama et al. (2005)nvestigated local knowledge in order to understand farmer’secognition and evaluation of landscape change in a rural areaith terraced paddies in south-western Japan. Farmers who were

nterviewed showed valuable knowledge about changes in florand about cultural practices that are needed for maintainingavourable conditions for the terraced paddies. This allowedhe authors to obtain an estimation of the work that is neededor managing this landscape. Pavlikakis and Tsihrintzis (2006)resent a survey of the local communities of the National Park ofastern Macedonia and Thrace in Greece, which allowed them

o identify the main socio-economic and environmental issues,s identified by local communities, that need to be included inhe decision-making process.

In our study, using a sample of the villagers who are oldnough to recall the 1950s, it has been shown that they col-ectively possess extensive and precise recollection of howheir landscape was traditionally managed, and comprehensivewareness of the broad changes to which that landscape haseen subjected. Particularly noteworthy is their knowledge ofraditional crafts – most of them no longer practiced – and ofocally built heritage. Informants were able to supply detailednformation about the location, ownership and state of repairf surviving built heritage and, even more relevant, about theormer location and cause of destruction of the heritage thatas been lost. Furthermore, in many cases they also providednteresting functional information, such as relating to the areashat were served by watermills. Their knowledge on the localultural heritage could provide valuable information to comple-ent existing inventories of cultural heritage on broader scales.

t could also be a starting point for the inventory of certain ele-ents of the cultural landscapes, such as field boundaries, which

ave not been (until now) the object of study in the region.his information on local heritage that was once aggregated atregional and a national level could be used for the elaborationf indicators regarding cultural features in the landscape.

Regarding landscape management, certain landscape-elevant traditional farming practices are to some extent stillaintained in a number of the villages investigated—in particu-

ar, the cultivation of cereals, the exploitation of hedgerow treesor firewood and shelter, the preparation and use of manure fromeather and gorse, and the extensive grazing of cattle and horsesn the scrubland areas. These practices have contributed to thehaping of the landscape for centuries. The cultivation of cerealsn rotation with other crops, and the exploitation of hedgerowrees, contributes to keep the appearance (aesthetics and field

tructure) and the biodiversity function of these elements in theultural landscape. Nevertheless, they are threatened by agricul-ural abandonment, as these practices are no longer economicallyrofitable. The traditional way of obtaining manure is also dis-3 e and

asmthad

htttimatt

5

slalebsatbthmoe

duimatcittiaao

emoit

ldl

A

(iivfas

rm

tX

R

A

A

A

BB

B

C

C

C

D

D

D

D

42 M.S. Calvo-Iglesias et al. / Landscap

ppearing and being replaced by the use of chemical fertilizers,table modernization and changes in the productive focus fromixed farming to beef cattle. However, extensive grazing of cat-

le and horses still has an important role in the local economy. Itas contributed to maintaining the scrubland areas with raisednd blanket bogs as well as wet and dry heathlands, which wereesignated in the Natura 2000 proposal as priority habitats.

The maintenance of traditional uses and cultural practices thatave proved to be sustainable should be taken into account forhe design of management schemes that are orientated towardshe conservation of landscape and its biodiversity. Furthermore,heir continuity is an opportunity to learn from ‘in vivo’ practicesn order to study its suitability for the management of other

ountainous scrubland areas of NW Spain that are designateds protected areas. This may well be relevant to other regions ofhe European Atlantic coast in which practices of this kind wereraditionally used in the past.

. Conclusions

In this study, farmer’s knowledge proved to be a valuableource of information on the past and present land-use system,andscape dynamics and landscape-relevant practices, as wells valuable information for the inventory of past and presentocal cultural heritage. Moreover, farmer’s knowledge providedssential information on the cultural landscape that could note easily gathered by other sources. For instance, detailed andpecific information on certain land-uses, such as crop associ-tions and cultural practices, cannot generally be inferred fromhe interpretation of old aerial photographs. In terms of the pastuilt heritage, farmers had key information about the heritagehat has been lost and the cause for its loss. They also showed toave valuable knowledge on socio-economics, providing infor-ation on functional relationships (that is, the area of influence

f the main economic centres) and on the influence of certainconomic activities in the households.

Farmer’s knowledge could therefore be very useful in theesign of landscape and nature conservation policies. In partic-lar, the development of agroenvironmental schemes requires anncreasing demand for empirical information to support the for-

ulation and analysis of agricultural policy measures that areimed at integrating environmental concerns (Piorr, 2003). Inhe study area concerned, it was found that farmer’s knowledgeomplements inventories of cultural elements – mainly local her-tage, land-use and cultural practices – as part of the informationhat is needed to develop a set of indicators for monitoring cul-ural landscapes. At the same time, the use of farmer’s knowledgen the design of such policies may increase their acceptabilitynd applicability, as they may become measures designed bynd for farmers, and contribute to increase farmers’ awarenessf their essential active role in landscape management.

We can learn from the example given by Cudlınovat al. (1999), which illustrates the drawbacks of landscape-

anagement subsidies that exclusively focus on the preservationf landscape patterns or ecological functions without takingnto consideration the socio-economic context and, particularly,he farmers’ point of view. In the words of O’Rourke (2005),

E

F

Urban Planning 78 (2006) 334–343

ocal inhabitants and farmers “have a meaningful voice in theesign and management of their past heritage and their futureandscapes”.

cknowledgements

We thank Ramon Dıaz-Varela and Francisco Calvo-Gomezformer district officer of the Agricultural Advisory Servicen the study area, who accompanied M.S.C.-I. during severalnterviews) for helping with the field work and providingaluable information on the study area; Manuel Marey-Perezor useful suggestions regarding sampling and interviewing;nd all the farmers who by sharing their knowledge made thistudy possible.

We would like to thank the editors and two anonymouseviewers for their helpful comments on an earlier draft of thisanuscript.This research was partially funded by a Ph.D. fellowship of

he Galician Regional Government, Direccion Xeral de I + D,unta de Galicia (Spain).

eferences

lexander, M.J., Kidd, A.D., 2000. Farmers’ capability and institutional inca-pacity in reclaiming disturbed land on the Jos Plateau, Nigeria. J. Environ.Manage. 59 (2), 141–155.

li, A., 2003. Farmers’ knowledge of soils and the sustainability of agriculturein a saline water ecosystem in Southwestern Bangladesh. Geoderma 111(3–4), 333–353.

ntrop, M., 2004. Why landscapes of the past are important for the future.Landsc. Urban Plann. 70 (1–2), 21–34.

alboa, X., 1990. O monte en Galicia. Edicions Xerais de Galicia, Vigo.ender, O., Boehmer, H.J., Jens, D., Schumacher, K.P., 2004. Using GIS to

analyse long-term cultural landscape change in Souther Germany. Landsc.Urban Plann. 70 (1–2), 111–125.

ouhier, A., 1979. La Galice, essai geographique d’un vieux complexe agraire.Universite de Poitiers, Vendee, France.

ools, N., De Pauw, E., Deckers, J., 2003. Towards an integration of conventionalland evaluation methods and farmers’ soil suitability assessment: a case studyin northwestern Syria. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 95 (1), 327–342.

ouncil of Europe, 2000. European Landscape Convention. ETS No. 176 Coun-cil of Europe Publishing Division, Strasbourg.

udlınova, E., Lapka, M., Bartos, M., 1999. Problems of agriculture and land-scape management as perceived by farmers of the Sumava mountains, CzechRepublic. Landsc. Urban Plann. 46, 71–82.

avis, A., Wagner, J.R., 2003. Who knows? On the importance of identifying“experts” when researching local ecological knowledge. Hum. Ecol. 31 (3),463–489.

esbiez, A., Matthews, R., Tripathi, B., Ellis-Jones, J., 2004. Perceptions andassessment of soil fertility by farmers in the mid-hills of Nepal. Agric.Ecosyst. Environ. 103 (1), 191–206.

hillion, S.S., Gustad, G., 2004. Local management practices influence theviability of the baobab, Adansonia digitata Linn. in different land-use types,Cinzana. Mali. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 101 (1), 85–103.

i Mauro, S.E., 2003. Disaggregating local knowledge: the effects of genderedfarming practices on soil fertility and soil reaction in SW Hungary. Geoderma111, 503–520.

llis, E.C., R.G., Yang, L.Z., Cheng, X., 2000. Long-term change in village-scale ecosystems in China using landscape and statistical methods. Ecol.Appl. 10 (4), 1057–1073.

jellstad, W.J., Dramstad, W.E., 1999. Patterns of change in two contrastingNorwegian agricultural landscapes. Landsc. Urban Plann. 45, 177–191.

e and

G

H

H

H

I

I

J

K

K

L

M

M

M

M

N

N

O

P

P

P

P

P

R

R

S

S

S

T

U

V

V

V

W

Z

SrStscrrmfB

RmaoamaaiitWB2

Uowaupuias to the Volcano Observatory of the University of Colima in Mexico. He is

M.S. Calvo-Iglesias et al. / Landscap

rossman, J.M., 2003. Exploring farmer knowledge of soil processes in organiccoffee systems of Chiapas, Mexico. Geoderma 111, 267–287.

aaland, S., 2002. Fem tusen ar med flammer. Det europeiske lyngheilandskapet.Fagbokforlaget Vigmostad Bjorke AS, Slovenia.

ammer, D., Wildavsky, A., 1994. La entrevista semiestructurada de finalabierto. Aproximacion a una guıa operativa. Historia y Fuente Oral 4, 23–61.

owarth, K., 1998. Oral History, a Handbook. Sutton Publishing Limited,Thrupp Stroud Gloucestershire.

iyama, N., Kamada, M., Nakagoshi, N., 2005. Ecological and social evaluationof landscape in a rural area with terraced paddies in southwestern Japan.Landsc. Urban Plann. 70 (3–4), 301–313.

NE, 2003. Nomenclator. Revision anual del padron municipal ano 2000.Relacion de unidades poblacionales de los municipios de Vicedo, Viveiro,Xove, Ourol y Muras. Instituto Nacional de Estadıstica, Madrid.

ongman, R.H.G., 2002. Homogenisation and fragmentation of the Europeanlandscape: ecological consequences and solutions. Landsc. Urban Plann.58, 211–221.

appelle, M., Avertin, G., Juarez, M., Zamora, N., 2000. Useful plants within acampesino community in a Costa Rican montane Cloud forest. Mount. Res.Dev. 20 (2), 162–171.

ruger, L.E., 2005. Community and landscape change in southeast Alaska.Landsc. Urban Plann. 72, 235–249.

ykke, A.M., 2000. Local perceptions of vegetation change and priorities forconservation of woody-savanna vegetation in Senegal. J. Environ. Manage.59 (2), 107–120.

c Donnald, M.A., Hofny-Collins, A., Healey, J.R., Goodland, T.C.R., 2003.Evaluation of trees indigenous to the mountain forest of the Blue Mountains,Jamaica for reforestation and agroforestry. For. Ecol. Manage. 175, 379–401.

eeus, J.H.A., 1995. Pan-European landscapes. Landsc. Urban Plann. 31,57–79.

eeus, J.H.A., Wijermans, M.P., Vroom, M.J., 1990. Agricultural landscapesin Europe and their transformation. Landsc. Urban Plann. 18, 289–352.

endez, V., Lok, R., Somarriba, E., 2001. Interdisciplinary analysis of home-gardens in Nicaragua: micro-zonation, plant use and socioeconomic impor-tance. Agroforest. Syst. 51 (2), 85–96.

ikodemus, O., Bell, S., Grine, I., Liepins, I., 2005. The impact of economic,social and political factors on the landscape structure of the Vidzeme Uplandsin Latvia. Landsc. Urban Plann. 70 (1–2), 57–67.

yeko, P., Edwards-Jones, G., Day, R., Raussen, T., 2002. Farmers’ knowledgeand perceptions of pests in agroforestry with particular reference to Alnusspecies in Kabale district, Uganda. Crop. Prot. 21 (10), 929–941.

’Rourke, E., 2005. Socio-natural interaction and landscape dynamics in theBurren, Ireland. Landsc. Urban Plann. 70 (1–2), 69–83.

alang, H., Mander, U., Luud, A., 1998. Landscape diversity changes in Estonia.Landsc. Urban Plann. 41 (3–4), 163–169.

avlikakis, G.E., Tsihrintzis, V.A., 2006. Perceptions and preferences of thelocal population in Eastern Macedonia and Thrace National Park in Greece.Landsc. Urban Plann. 77, 1–16.

eroni, N., Hanazaki, N., 2002. Current and lost diversity of cultivated vari-eties, especially cassava, under swidden cultivation systems in the BrazilianAtlantic Forest. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 92 (2–3), 171–183.

iorr, H.P., 2003. Environmental policy, agri-environmental indicators and land-scape indicators. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ 98 (1–3), 17–33.

rimdahl, J., 1999. Agricultural landscapes as places of production and for liv-ing in owner’s versus producer’s decision making and the implications forplanning. Landsc. Urban Plann. 46, 143–150.

ıos Rodrıguez, M.L., 1997. Transformacion agraria. Los terrenos de montey la economıa campesina, siglos XII–XIV. In: Torres de Luna, Ma.P., LoisGonzalez, R., Saavedra, P. (Eds.), Semata, vol. 9. University of Santiago deCompostela Press, Santiago de Compostela, Spain, pp. 145–171.

obertson, H.A., Mc Gee, T.K., 2003. Applying local knowledge: the contribu-

tion of oral history to wetland rehabilitation at Kanyapella Basin, Australia.J. Environ. Manage. 69, 275–287.aavedra, P., 1985. Economıa, polıtica y sociedad en Galicia: La provincia deMondonedo, 1480–1830. Consellerıa de Presidencia Xunta de Galicia, San-tiago de Compostela, Spain.

wtBL

Urban Planning 78 (2006) 334–343 343

ITGA, 2000. Mapa de coberturas y usos del suelo de Galicia. E:1/25000.Sociedade para o Desenvolvemento Comarcal de Galicia Consellerıa dePolıtica Agroalimentaria e Desenvolvemento Rural Xunta de Galicia Santi-ago de Compostela, Spain.

tanner, D., Bourdeau, P. (Eds.), 1995. Landscapes. Chapter 8. Europe’s Envi-ronment, The Dobrıs Assessment. European Environment Agency, Copen-hagen.

hompson, P., 1978. The Voice of the Past. Oxford University Press,Oxford.

NESCO, 1997. Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the WorldHeritage Convention. UNESCO, Paris.

an Eetvelde, V., Antrop, M., 2004. Analyzing structural and functional changesof traditional landscapes—two examples from Southern France. Landsc.Urban Plann. 67 (1–4), 79–95.

illares, R., 1998. A historia. Biblioteca basica da cultura galega. Galaxia S.A.,Vigo.

os, W., Meekes, H., 1999. Trends in European cultural landscape development:perspectives for a sustainable future. Landsc. Urban Plann. 46, 3–14.

ebb, N.R., 1998. The traditional management of European heathlands. J. Appl.Ecol. 35, 987–990.

urayk, R., El-Awar, F., Hamadeh, S., Talhouk, S., Sayegh, C., Chehab, A.G.,Al Shab, K., 2001. Using indigenous knowledge in land-use investigations:a participatory study in a semi-arid mountainous region of Lebanon. Agric.Ecosyst. Environ. 86, 247–262.

ilvia Calvo Iglesias is an agriculture and forestry engineer, working asesearcher at the Agroforestry Engineering Department of the University ofantiago de Compostela (Spain) in the EU Culture 2000 project “European Cul-

ural Landscapes our common cultural heritage”. She specializes in landscapecience, GIS and remote sensing and she has recently finished her PhD on theharacterization and dynamics of cultural landscapes in Galicia (NW Spain). Asesearcher at the Land Laboratory group she has participated in several projectselated to landscape planning, environmental management and rural develop-ent, noteworthy Life and LEADER+ programs, as well as in the application

or the candidature of the Biosphere Reserve Alto Mino Basin to the Man andiosphere Program (UNESCO).

afael Crecente Maseda is a professor of the Agroforestry Engineering Depart-ent at the University of Santiago de Compostela (Spain). He has 10 years of

cademic and research experience, focusing on landscape planning, rural devel-pment, land tenure and land development, GIS, environmental managementnd cooperation for development. He is co-founder of the Land Laboratory, aultidisciplinary research and teaching group specializing in the fields described

bove. He received his PhD in Agricultural Engineering at University of Santi-go de Compostela. His international experiences include cooperation projectsn Ecuador, with the Galician Government and BID, and consultancies for DSEn Bolivia, Spain and Germany. He has been hosted by the Land Tenure Cen-er and the Department of Urban and Regional Planning at the University of

isconsin-Madison (USA) in 2003 and 2004, and also at the Lehrstuhl furodenordnung und Landentwicklung at Technische Universitat of Munchen in002.

rbano Fra Paleo holds a PhD in geography. He is a professor of the Departmentf Geography and Spatial Planning at the University of Extremadura (Spain) andorks in the fields of GIS, rural development and risk assessment. He has worked

t the Environment Institute of the University of Denver developing educationalnits on renewable energy awareness and at the University of Santiago de Com-ostela in the application of geoinformation systems to rural studies. He hasndertaken research visits to the United States Geological Survey participat-ng in the mapping programs and risk assessment of volcanic hazards as well

orking in a cooperation project in Morocco dealing with the management ofhe Bouregreg water basin, and in 2005 he has been awarded a Helen and Johnest Research Fellowship to do research at the American Geographical Societyibrary on hazard representation in old cartography.