Discourse Level Tagger for Mahabhasya - a Sanskrit Commentary on Panini's Grammar

Transcript of Discourse Level Tagger for Mahabhasya - a Sanskrit Commentary on Panini's Grammar

Discourse Level Tagger for Mahabhas.ya - a SanskritCommentary on Pan. ini’s Grammar

Monali Das

University of [email protected]

Amba Kulkarni

University of [email protected]

Abstract

Mahabhas.ya is an important commen-tary on Pan. ini’s grammar for Sanskritand is highly structured. The tradi-tional scholars have tagged it manuallyshowing its underlying discourse struc-ture. The traditional grammar also dis-cusses clues for discourse level annota-tions. Taking into account these clueswe have developed an automatic tag-ger for tagging the Mahabhas.ya. Thistagger is described in this paper, alongwith its performance evaluation. Wehave also extended this tag-set to onanother important text Sabarabhas.ya.

1 Introduction

Discourse level analysis is an important mod-ule in NLP which takes us beyond sentencelevel analysis. While grammar is basicallyabout how words combine to form sentences,text and discourse analysis is about how sen-tences combine to form texts (Salike, 1995).

Four types of discourse structures are dis-cussed in the modern linguistics.

1. Topic Structure: The topic structuregives a broad outline of the topics in agiven text.

2. Functional Structure: It identifies varioussections within a topic serving differentfunctions.

3. Event Structure: This identifies variousevents in the discourse and show them onthe time-line.

4. Coherence Relations: Based on the lin-guistic clues and from the functional andevent structure various coherence rela-tions are identified.

(Mann and Thompson, 1988) proposed aRhetorical Structure Theory (RST) for dis-course analysis. The intentional and informa-tional relations between adjacent texts are rep-resented in the form of a binary tree structure.(Wolf and Gibson, 2005) suggested a Depen-dency Graph Structure (DG) to show the re-lations between the topic and sub-topic seg-ments. The segments here unlike RST neednot be adjacent. (Polanyi, 1988) suggested aLinguistic Discourse Model (LDM) which re-sembles RST. In this model each node inheritsthe properties of its parent node and a parentnode is an interpretation of its children nodesand the relations between them.

There have been several efforts in the recentpast in computational linguistics in the fieldof discourse analysis. The major efforts is theproposal of discourse tag-set by (Joshi et al.,2007) in the form of Penn Dependency Tree-Bank (PDTB). The annotation scheme orig-inally developed for English was further ex-tended to Arabic (Alsaif, 2012), Chinese (Xue,2005), Turkish (Zeyrek and Webber, 2008) andHindi (Prasad et al., 2009). (Mladova et al.,2008) suggested a scheme for Czech and En-glish (Praguian Discourse TreeBank) which isconsistent with the dependency tree bank ofPrague.

The automatic annotation and evaluationhelp us in understanding the discourse struc-tures further. (Jurafsky et al., 2000) presenteda framework for modelling and automatic clas-sification of dialogue acts with an accuracy of74.7%. (Jinova et al., 2012) experimented withsemi-automatic annotation of intra-sententialdiscourse relations in PDT. The automatic an-notation of discourse structure of various userforums for thread solvedness classification ac-curacy is an important application of the au-tomatic discourse structure analysis being ex-

plored by (Baldwin et al., 2012), (Xi et al.,2004), (Fortuna et al., 2007), (Kim et al.,2010).

All these discourse theories have been cen-tered around English and other European lan-guages, though PDT and RST have been re-cently being applied to Arabic, Hindi andTamil as well. These theories may be triedon Sanskrit corpus as well. But there are twoimportant considerations. The first and fore-most is that Sanskrit comes with a rich her-itage of linguistic theory of its own. The richgrammatical tradition of India has a vast liter-ature on almost all aspects of language analy-sis ranging from phonology to discourse anal-ysis. Thus it is natural to look at these theo-ries which have been discussed over centuries,with a focus on Sanskrit literature. The sec-ond reason is Sanskrit literature comes withannotations, though not by original authors,but by the later commentators. These annota-tions are done following the grammatical the-ories. Hence it is natural to use these theoriesfor computational models related to Sanskrit.

In this paper in the next section we givea brief survey of Indian theories of discourseanalysis. In section 3 we take up one particu-lar Sanskrit text viz. Mahabhas.ya of Patanjaliwhich is available as a tagged text and discussits internal structure providing tagging guide-lines for the tag-set. In section 4 we look atthe clues suggested in the Sanskrit literatureand built a FSA for automatic tagging of thediscourse relations. In section 5 we discuss theextension of this tagger to handle another im-portant text - Sabarabhas.ya - a commentaryon Mımamsa sutra.

2 Indian Theories of DiscourseAnalysis

Indian Grammatical Theories evolved in orderto understand the Vedic literature and protectthem. The theories developed in three direc-tions. The first one, dealing with word andsentence formation and analysis. This leadto the establishment of Vyakaran. a (grammar)school. The second one dealing with the se-mantics, logic and inference lead to the for-mation of Nyaya (logic) school of thought andthe third one dealing with discourse analysisresulted in Mımamsa (exegesis) school. As

we glance the Indian literature, we notice dis-cussions on various aspects of textual analy-sis which basically deal with the coherence oftexts. The coherence is judged at different lev-els right from the relations between two ad-joining sentences to the coherence at the levelof texts with respect to the discipline. The co-herence levels discussed in the literature are asfollows -

1. Sastra sangati (Bhat.t.acarya, 1989): Thisis a subject level coherence.

2. Adhyaya sangati (Bhat.t.acarya, 1989):This is a chapter or a book level coher-ence. Among the scientific literature inSanskrit, we find three different trendsunder the adhyaya sangati. One is knownas Bhas.ya parampara. Here the origi-nal text is in the form of sutras (com-pact aphorisms). This is followed by acommentary explaining the sutras, op-tionally followed by an explanation (t.ıka),a note (t.ippan. i) etc. The commen-taries may be nested, i.e. there is acommentary on the original sutras andthen sub-commentary on this commen-tary, and further sub-commentary on thesub-commentaries and so on. At eachstage the number of commentaries maybe more than one. The sutras (com-pact aphorism) as well as the commen-taries and sub-commentaries follow a cer-tain discourse structure.

Another trend is where the original textestablishes a theory, and the later scholarswrite criticisms on it attacking the origi-nal view and proposing a new view. Thistrend is known as Khan. d. ana-man. d. anaparampara. And there can be a series ofsuch texts criticizing the previous theoryin the series and proposing a new theory.The structure of these texts then leads toa tree structure, where the siblings indi-cate different criticisms of the same textleading to different view points.

The third trend is to write Prakaran. agranthas (books dealing with a specificimportant topic among several topics dis-cussed in the texts in sutra form). Thesebooks are thus related to the original

sutra texts, but also have their own nestedcommentaries.

3. Pada sangati (Bhat.t.acarya, 1989): Thisis a section level coherence.

4. Adhikaran. a sangati (Bhat.t.acarya,1989): This is a topic level coherence.Mımamsakas (exegesists) discussed aboutthis sangati. Further Naiyayikas (logi-cians) discussed about six topic levelrelations (Sastri, 1916). They are

(a) Prasanga - Corollary.

(b) Upodghata - Pre-requisite.

(c) Hetuta - Causal dependence.

(d) Avasara - Provide an opportunity forfurther inquiry.

(e) Nirvahakaikya - The adjacent sec-tions have a common end.

(f) Karyaikya - The adjacent sectionsare joint causal factors of a commoneffect.

5. Sub-topic level analysis: Under this levelwe see two different tag sets one found inexegesist’s analysis and the other in gram-marian’s analysis.

A. Exegesist’s (Mımamsakas) tag-set(Bhat.t.acarya, 1989):

(a) Aks.epa - Objection

(b) Dr.s.t.anta - Example

(c) Pratyudaharan. a - Counter-example

(d) Prasangika - Corollary

(e) Upodghata - Pre-requisite

(f) Apavada - Exception

B. Grammarians (Vaiyakaran. as) tag-set(Joshi, 1968):

(a) Prasna - Question

(b) Aks.epa - Objection

(c) Samadhana - Justification

(d) Uttara - Answer

(e) Vyakhya - Elaboration

6. Inter-sentential relations: In (Ramakrish-namacaryulu, 2009), inter-sentential rela-tions are classified into 9 sub-headings.These are given below along with the lex-ical clues which mark these relations.

(a) Hetuhetumadbhavah. (cause effect re-lationship): yatah. (because), tatah.(hence), yasmat (because), tasmat(hence), atah. (therefore).

(b) Asaphalyam (failure): kintu (but).

(c) Anantarakalınatvam (following ac-tion): atha (then).

(d) Karan. asatve’api karyabhavah. /karan. abhave’api karyotpattih. (non-productive effort or product withoutcause): yadyapi (even-though),tathapi (still), athapi (hence).

(e) Pratibandhah. (conditional): yadi(if), tarhi (then), cet (if/provided),tarhyeva (then only).

(f) Samuccayah. (conjunction): ca, apica(and also).

(g) Purvakalıkatvam: The non-finiteverb form ending with suffix ktva ‘ad-verbial participial’.

(h) Prayojanam (Purpose of the main ac-tivity): The non-finite verb form end-ing with suffix tumun ‘to-infinitive’.

(i) Samanakalıkatvam (Simultaneity):The non-finite verb form endingwith suffix Satr. and Sanac ‘presentparticiple’.

Thus we notice that the Indian grammati-cal theories have, to a large extent, guidelinesfor analysis of a text at different levels of dis-course.

3 Structure of Mahabhas.ya

Pan. ini’s As.t.adhyayi (circa 500 BC) is an im-portant milestone in the developmental his-tory of Indian theories of language analysis.As.t.adhyayi is in sutra1 (compact aphorism)form and hence to understand it one needs anexplanation. Patanjali wrote a detailed com-mentary on As.t.adhyayi known as Mahabhas.ya(the great/large commentary). It providesexplanation of these sutras and also throwslight on important aspects of linguistic anal-ysis. It is the second important milestone ofthe Indian grammatical tradition. The text

1alpaks.aram asandigdham saravat visvato mukham.astobham anavadyam ca sutram sutravido viduh. .

A sutra contains minimum number of words, is unam-biguous, contains the essence of the topic, has universalvalidity and is devoid of any faults.

of Mahabhas.ya follows a very well defined dis-course structure.

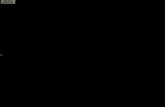

Mahabhas.ya contains commentaries on vari-ous sutras and the supplementary sutras calledas Varttika-s. The relevant level of dis-course analysis for Mahabhas.ya is then theadhikaran. a (topic) level analysis and all thelower level analysis viz. sub-topic level andinter-sentential. The sutra/varttika sets upthe new topic and all the discussions underthis follow a well defined structure. The topiclevel analysis of a commentary on one sutrawas taken up ealier (Kulkarni and Das, 2012).Figure 1 shows the structure of a commentaryon the sutra P2.1.1 (Samarthah. Padavidhih. ).

Figure 1: Structure of a commentary‘samarthah. padavidhih. ’

There are 14 topics under the main headingsof the sutra P2.1.1 (samarthah. padavidhih. ).These 14 topics are related to each other bya set of relations, which show the coherenceof the discussion under this sutra. These rela-tions are the topic level or adhikaran. a sangati-s. The tagging at this level involves semanticanalysis of the text.

The original Mahabhas.ya does not have anyof the mark-ups. The first version of markedup texts is published by Nirn. aya Sagara Press,Bombay in early 1900 in 6 volumes.

We find the text marked up at sub-topiclevel analysis. No text contains the descriptionor explanation of the tags used, nor is thereany prologue mentioning the purpose of thistagging, as is the case with any typical San-skrit texts centuries old. So the first task wetook up is to provide a manual listing the tagsused, the semantics associated with these tags

and at least an example from the Mahabhas.yaillustrating the tag.

3.1 Mahabhas.ya’s Sub-Topic LevelTag-set

The annotated Mahabhas.ya has 9 major tagsand several sub-tags under each major tag.These sub-tags are different in different vol-umes. But the major tags are the same in allthe books. We give below a brief description ofthese 9 tags, with an example each from theactual tagged Mahabhas.ya. The example inmost cases consists of a pair of Sanskrit sen-tences/paragraphs. The first one sets the con-text under which the next set of sentence(s) isuttered. The label is attached to the secondone.

1. Prasna (Question) An independentquestion about some topic or an argumentis marked with a question tag. For exam-ple,

• Skt: athavidhisabdarthanirupan. adhikaran. am.

Eng: Now starts the section in whichthe meaning of the word Vidhi is ex-amined.2

• Skt: (prasnabhas.yam): vidhih. itikah. ayam sabdah. . [1.1]3

Eng: What is this word Vidhi?

2. Uttara (Answer) An answer to a ques-tion is tagged with this tag. For example,

• Skt: (prasnabhas.yam): vidhih. itikah. ayam sabdah. .

Eng: What is this word vidhi?

• Skt: (uttarabhas.yam):vipurvadghajnah. karmasadhanaikarah. . vidhıyate vidhiriti. kimpunarvidhıyate. samaso vibhak-tividhanam parangavadbhavasca.[1.2]

Eng: The letter i denoting the pas-sive sense (is added) after (the root)ghajn preceded by the pre-verb vi.

2English translations are taken from Patanjali’sVyakaran. a Mahabhas.ya Samarthahnika (P 2.1.1)Edited with Translation and Explanatory Notes by SD Joshi.

3The first number denotes to the topic number andthe second number denotes to the sub-topic number ofthe sutra samarthah. padavidhih. P2.1.1.

What is prescribed by Pan. ini’s rulesis vidhi: ‘operation’. But whatcould that be which is prescribed?‘compounding’, ‘prescription of case-ending’ and ‘treatment as a part ofthe following word’.

3. Aks.epa (Objection) An objection toan answer or resolution is marked as anaks.epa. For example,

• Skt: (uttarabhas.yam): vakyepr.thagarthani. rajnah. purus.ah. iti.samase punah. ekarthani rajapurus.ah.iti.

Eng: In the compounded word-group words have separate meaningsof their own, like rajnah. purus.ah. :king’s man. But in a compound,words have a single meaning, like inrajapurus.ah. : king-man.

• Skt: (aks.epabhas.yam): kimucy-ate pr.thagarthani iti yavata rajnah.purus.a anıyatamityukte rajapurus.aanıyate rajapurus.a iti ca sa eva.[4.44-45]

Eng: Why do you say ‘words haveseparate meanings of their own’? Be-cause when we say ‘let the king’sman be brought’, the king-man isbrought. And when we say ‘let theking-man be brought’, the same manis brought.

4. Samadhana (Resolution) This tag isused to mark an answer to an objection.For example,

• Skt: (aks.epabhas.yam): yadisapeks.amasamartham bhavatiiti ucyate rajapurus.o’bhirupah.rajapurus.o darsanıyah. atra vr.ttirnaprapnoti.

Eng: If we accept the statement,‘what requires an outside wordis treated as semantically uncon-nected’ then the word-compositionrajapurus.a: king-man in the ex-pressions rajapurus.ah. abhirupah. :handsome king-man, rajapurus.ah.darsanıyah. : goodlooking king-manwould not result from the uncom-pounded word-groups abhirupah.

rajnah. purus.ah. and darsanıyah.rajnah. purus.ah. .

• Skt: (samadhanabhas.yam): naes.ah. dos.ah. . pradhanam atrasapeks.am bhavati ca pradhanasyasapeks.asya api samasah. . [3.27-28]

Eng: Nothing wrong here. Becauseit is here the main member which re-quires an outside word. And com-pounding does take place, even ifthe main member requires an outsideword.

5. Badhaka (Rejection): This tag is usedto mark the rejection of the argumentssuch as, objection, answer of an objection,refutation, criticism etc. For example,

• Skt: (samadhanabhas.yam): naes.ah. dos.ah. . samudayapeks.a atras.as.t.hı sarvam gurukulam apeks.ate.

Eng: Nothing wrong here. Here thegenitive qualifies the whole word gu-rukulam.

• Skt: (samadhanabadhakabhas.yam):yatra tarhi na samudaya apeks.as.as.t.hı tatra vr.ttih. na prapnoti.[3.30-31]

Eng: Then when a word in genitivedoes not qualify the whole, it shouldnot result in a compound formation.

6. Sadhaka (Reaffirmation): This tag isused to mark the reaffirmation of an argu-ment which has been earlier rejected. Forexample,

• Skt: (aks.epabadhakabhas.yam):nanu ca gamyate tatra samarthyam.kumbhakarah. nagarakarah. iti.

Eng: But is it not so, that, when wesay kumbhakarah. : ‘pot-maker’ or na-garakarah. : ‘city-maker’, we do appre-hend semantic connection betweenpot and maker.

• Skt: (aks.epasadhakabhas.yam):satyam gamyate utpannetu pratyaye. sa eva tavatsamarthadutpadyah. . [2.12-13]

Eng: Yes, that is true. It is appre-hended once a suffix has been added.But that same suffix must first be

generated after the semantically con-nected word.

7. Udaharan. a (Example): This tags theexample.

• Skt: (subalo-podaharan. abhas.yam): supah.alopah. bhavati vakye. rajnah.purus.ah. iti. samase punah. nabhavati. rajapurus.a iti. [5.49]

Eng: Non-disappearance of case-ending occurs in an un-compoundedword-group, like rajnah. purus.ah. :king’s man. But in a compound itdoes not occur, as in rajapurus.ah. :king-man.

8. Dus.an. a (Criticism): This tag is tomark criticism. For example,

• Skt: (vyakhyabhas.yam):samanavakya iti prakr.tyanighatayus.madasmadadesa vak-tavyah. .

Eng: Under the heading of ‘withinthe same sentence’ the accents andsubstitutions for yus.mad and asmadare to be stated.

• Skt: (dus.an. avarttikam): yogepratis.edhascadibhih. . [9.115]

Eng: When there is connection withand the prohibition should also bestated.

9. Vyakhya (Explanation): Explanationof either an objection, answer or alterna-tive view is marked with this tag. Forexample,

• Skt: (samadhanavarttikam):pr.thagarthanamekarthıbhavah.samarthavacanam. Eng: The wordsamartha means single integratedmeaning of the separate meanings.

• Skt: (vyakhyabhas.yam):pr.thagarthanampadanamekarthıbhavah. samarthami-tyucyate. [4.42]

Eng: The single integrated mean-ing of the words which have separatemeaning is called samartha.

Out of these 9 tags, 3 tags viz. sadhaka,badhaka and dus.an. a are rare. The four tags

Tags Frequency

Prasna 10(Question)

Pratiprasna 1(Counter question)

Pratiprasnottara 1(Answer to a counter question)

Uttara 6(Answer)

Aks.epa 47(Objection)

Pratyaks.epa 6(Counter objection)

Pratyaks.epasamadhana 2(Answer to a counter objection)

Samadhana 40(Answer to an objection)

Vyakhya 34(Explanation)

Udaharan. a 8(Example)

Table 1: Tags with their frequencies ofSamarthahnikam

prasna, uttara, aks.epa and samadhana alsohave sub-tags viz. pratiprasna (a questionto a question), pratiprasnottara (answer to aquestion to a question), pratyaks.epa (counterobjection) and pratyaks.epasamadhana (answerto a counter objection), which are more fre-quent. The distribution of these 10 tags- 6 main tags and 4 sub-tags, in onebook (samarthahnikam) among 87 books ofMahabhas.ya is shown in Table 1.

4 Mahabhas.ya Tagger

The tags used in Mahabhas.ya are generaland are found to be used in the textsfrom other disciplines such as philosophyetc. Traditional texts also discuss clues tomark these tags. For example, Bhoja Raja’sSr.ngara Prakas.a (Dvivedı and Dvivedı, 2007),Sabdabodhamımamsa (Tatacharya, 2005) andAvyaya Kosa (Srivatsankacarya, 2004) do pro-vide such clues for some tags. The clues fortwo tags prasna (question) and aks.epa (ob-jection), and their sub-tags viz. pratiprasna(counter question) and pratyaks.epa (counterobjection) are in the form of possible Lexicalword(s).

A. The list of words that classify a paragraphas a prasna (question) are the wh-wordsviz. kim, kah. , kimartham, katara, kutah. ,kva, kani, katham, kaya, kena etc.

B. The list of words that classify a paragraphas a aks.epa (objection) are evam api,katham, kvacit, yadi, kasmat na, nanu ca,yatra tarhi, kim punah. etc.

We looked at one book (ahnika) of thetagged text for the clues for other two tagsviz. pratiprasna and pratyaks.epa. The lexicalclues are,

Pratiprasna: kah. punah. , kah. ca, kim ca.

Pratyaks.epa: na va, kasmat na, kasyapunah. , kah. va, kva ca, kinca.

From the semantics of the tags, it is clearthat an uttara (answer) tag should follow aprasna (question). The pratiprasna (counterquestion) follows a prasna (question) andpratiprasnottara (answer to a counter ques-tion) follows a pratiprasna (counter ques-tion). An aks.epa (objection) arises only af-ter an answer (uttara). The samadhana (an-swer to an objection) is for an aks.epa (ob-jection) and pratyaks.epa (counter objection)is to a aks.epa (objection). The pratyaks.epasamadhana (answer to the counter objection)will follow the pratyaks.epa (counter objec-tion). Any samadhana (answer to an objec-tion) can be followed by a aks.epa (objection)only. Varttika-s are the supplementary rules,which can occur at the very beginning or itcan upon one prasna (question) or aks.epa (ob-jection). This is represented as a finite stateautomata in Figure 2.

The digital version of the tagged text ofcomplete Mahabhas.ya is not available. Only4 books out of 87 books were available atthe time of testing. Of these we used onebook for framing the rules and gathering cuesand tested our automata on the rest of thethree books. Once digitized versions of otherbooks are available the automata tagger willbe tested on them. The precision and recallfor the three books is given in Table 2. Ta-ble 3 gives the precision and recall for eachtag in all the three books together. In thesethree books, we did not find any instance ofpratyaks.epa and pratyaks.epasamadhana.

Figure 2: Finite State Automata of Tags

5 Extending the tagger

The tagger performed satisfactorily on a partof Mahabhas.ya text. Till the digital copies ofother parts of the Mahabhas.ya text becomeavailable, we thought of evaluating the tag-ger on other commentary. Since the com-mentaries are to establish the necessity of asutra, the assumption is that the basic struc-ture of commentary should be the same. Wechose a commentary on the Mımamsa sutra-s.The Mımamsa sutra-s are written by Jaiminıaround the end of 2nd century AD. It consistsof 12 adhyaya-s (chapters) and 60 pada-s (sec-tions). This text provides rules for the inter-pretation of the Veda-s. Earlier scholars wrotecommentaries on Mımamsa sutra but unfor-tunately they are lost. A major commentaryis composed by Sabarasvamı around 5th cen-tury and is well known as Sabarabhas.ya. Thisis the only extant and authoritative commen-tary on full 12 chapters of the Mımamsasutraof Jaiminı.

The commentary used for our study isthe Hindi translation of Sabarabhas.yam byYuddhis. t.hira Mımamsaka. This Hindi trans-lation is marked up with only two tags viz.Aks.epa and Samadhana. From the tags inHindi translation, we constructed the digital-ized version of the tagged Sanskrit commen-tary. Since the tagged text had only twotags, we modified our automaton to suit thisstructure removing the nodes corresponding to

Books (Ahnika-s) Precision Recall F Score

Karakahnikam 90.04% 86.45% 88.20%

Paspasahnikam 76.47% 79.13% 77.77%

Pratipadikarthases.ahnikam 85.37% 77.21% 81.08%

Table 2: Precision Recall Table

Tags Total Tags Precision Recall F Score

P 78 80.00% 76.92% 78.42%

PP 4 100.00% 75.00% 85.71%

PPU 1 50.00% 100.00% 66.66%

U 64 82.76% 75.00 78.68%

A 65 70.49% 66.15% 58.25%

S 70 67.24% 55.71% 60.93%

VA 111 98.23% 100.00% 99.10%

VYA 109 95.58% 99.08% 97.29%

Table 3: Precision Recall Table for Each Tags

other tags. This led us to modify the lexicalcues for the tags as well. So the cues for Aks.epain Sabarabhas.ya included the clues from bothPrasna as well as Aks.epa of the Mahabhas.ya.In addition, we found some stylistic variationin the cues. While many of the cues fromMahabhas.ya did not find any place in theSabarabhas.ya it included one new phrase nabrumah. (literally do not say this), as a markerfor Aks.epa. Modifying the tagger accordingly,we tested it on the 3rd chapter 1st section6th adhikaran. a’s 12th sutra of Sabarabhas.yaviz. Arun. adhikara and the precision and recallwere found to be 96.00% and 82.76% respec-tively.

6 Conclusion

Sanskrit has a rich grammatical tradition andoffers theoretical insights for discourse analy-sis as well. The principles for analysis beinglanguage independent, these insights shouldbe applicable to other languages as well. Inthis paper we have shown the applicability ofthis analysis in the context of scientific textin Sanskrit. The implementation as a FSA islanguage independent with the clue set as alanguage dependent component. It will be in-teresting to use this further on various forumson internet.

References

Amal AlSaif and Katja Markert. 2010. The leedsarabic discourse treebank: Annotating discourseconnectives for arabic. In Nicoletta Calzolari,Khalid Choukri, Bente Maegaard, Joseph Mar-iani, Jan Odijk, Stelios Piperidis, Mike Rosner,and Daniel Tapias, editors, Proceedings of theSeventh International Conference on LanguageResources and Evaluation (LREC’10), pages2046–2053, Valletta, Malta. European LanguageResources Association (ELRA).

Amal Alsaif. 2012. Human and Automatic Anno-tation of Discourse Relations for Arabic. Ph.D.thesis, School of Computing, The University ofLeeds.

Timothy Baldwin, Li Wang, and Su Nam Kim.2012. The utility of discourse structure in iden-tifying resolved threads in technical user forums.In Proceedings of COLING 2012: Technical Pa-pers, pages 2739–2756, Mumbai. COLING 2012Organizing Commitee.

Sri Jıvananda Vidyasagar Bhat.t.acarya.

1989. Srı Madhavacaryaviracita JaiminıyaNyayamalavistarah. . Kr.s.n. adas Academy,Varanasi.

Revaprasad Dvivedı and SadasivakumarDvivedı. 2007. Sarasvatı Kan. t.habharan. asyaBhojarajasya Sahityaprakasa NamaSr. ngaraprakasah. , Prathamabhagah. 1 - 14Prakasah. . Indiragandhi Kala Kendram, NewDelhi and Kalidasa Samsthan, Varanasi.

B. Fortuna, E.M. Rodrigues, and N. Milic-Frayling. 2007. Improving the classifica-tion of newsgroup messages through social net-work analysis. In In Proceedings of the 16th

ACM Conference on Information and Knowl-edge Management (CIKM 2007), page 877880,Lisbon, Portugal.

Pavlina Jinova, Jiri Mirovsky, and Lucie Po-lakova. 2012. Semi-automatic annotation ofintra-sentential discourse relations in pdt. InProceedings of the Workshop on Advances inDiscourse Analysis and its Computational As-pects (ADACA), COLING, pages 43–58, Mum-bai. COLING 2012 Organizing Commitee.

S D Joshi and J.A.F. Roodbergen. 1975.Patanjali’s Vyakaran. a Mahabhas.yaKarakahnikam (P 1.4.23–1.4.55). Centerof Advanced Study in Sanskrit, Pune.

S D Joshi and J.A.F. Roodbergen. 1981.Patanjali’s Vyakaran. a Mahabhas.yaPratipadikarthases. ahnikam ( P2.3.46–2.3.71).Center of Advanced Study in Sanskrit, Pune.

S D Joshi and J.A.F. Roodbergen. 1986.Patanjali’s Vyakaran. a Mahabhas.yaPaspasahnikam. Center of Advanced Study inSanskrit, Pune, first edition.

Aravind Joshi, Rashmi Prasad, Eleni Miltsakaki,Nikhil Dinesh, Alan Lee, Livio Robaldo, andBonnie Webber, 2007. The Penn DiscourseTreebank 2.0 Annotation Manual. The PDTBResearch Group.

S D Joshi. 1968. Patanjali’s Vyakaran. aMahabhas.ya Samarthahnika (P 2.1.1) Editedwith Translation and Explanatory Notes. Cen-ter of Advanced Study in Sanskrit, Poona, firstedition.

Daniel Jurafsky, Andreas Stolcke, Klaus Ries,Noah Coccaro, Elizabeth Shriberg, RebeccaBates, Paul Taylor, Rachel Martin, Carol VanEss-Dykema, and Marie Meteer. 2000. Dia-logue act modeling for automatic tagging andrecognition of conversational speech. In Asso-ciation for Computational Linguistics, volume26:3, pages 339–373. Association for Computa-tional Linguistic.

Su Nam Kim, Li Wang, and Timothy Baldwin.2010. Tagging and linking web forum posts. InIn Proceedings of the 14th Conference on Com-putational Natural Language Learning (CoNLL-2010), pages 192–202, Uppsala, Sweden.

Sivadatta D. Kudala. 1912. Patanjali’sVyakaran. a Mahabhas.ya with Kaiyat.a’s Pradıpaand Nagesa’s Uddyota, volume 2. Nirn. ayasagara press, Bombay.

Amba Kulkarni and Monali Das. 2012. Dis-course analysis of sanskrit texts. In Lucie Po-lakova Eva Hajicova and Jiri Mirovsky, editors,Proceedings of the Workshop on Advances inDiscourse Analysis and its Computational As-pects (ADACA), COLING, pages 1–16, Mum-bai. COLING 2012 Organizing Commitee.

William C Mann and Sandra A Thompson. 1988.Rhetorical structure theory: Toward a func-tional theory of text organization. Text - Inter-disciplinary Journal for the Study of Discourse,8(3):243–281.

Yudhis.t.ira Mımam. saka. 1990.Mımam. sasabarabhas.yam, volume 2. Ram-lal Kapur Trust, Sonipat, Haryana.

Lucie Mladova, Sarka Zikanova, and Eva Hajicova.2008. From sentence to discourse: Building anannotation scheme for discourse based on praguedependency treebank. In Nicoletta Calzolari,Khalid Choukri, Bente Maegaard, Joseph Mar-iani, Jan Odijk, Stelios Piperidis, and DanielTapias, editors, In Proceedings of the 6th Inter-national Conference on Language Resources andEvaluation (LREC), pages 2564–2570, Marakes,Maroko. European Language Resources Associ-ation (ELRA).

Livia Polanyi. 1988. A formal model of discoursestructure. Journal of Pragmatics, 12(5–6):601–638.

Rashmi Prasad, Umangi Oza, Sudheer Kolachina,Dipti Misra Sharma, and Aravind Joshi. 2009.The hindi discourse relation bank. In Proceed-ings of the Third Linguistic Annotation Work-shop, ACL-IJCNLP, pages 158–161, Suntec,Singapore. Association for Computational Lin-guistics.

K V Ramakrishnamacaryulu. 2009. Annotatingsanskrit texts based on Sabdabodha systems. InAmba Kulkarni and Gerard Huet, editors, Pro-ceedings Third International Sanskrit Computa-tional Linguistics Symposium, pages 26–39, Hy-derabad, India. Springer-Verlag, LNAI 5406.

Raphael Salike. 1995. Text and Discourse Anal-ysis, Language Workbooks series, series editorRichard Hudson. Routledge, London.

Ananta Sastri. 1916. Karikavalı with thecommentaries Muktavalı, Dinakarı, Ramarudrı.Nirn. aya Sagara Press, Bombay.

Sri V Srivatsankacarya. 2004. Avyaya Kosa. Sam-skrit Education Society, Chennai 4.

N S R Tatacharya. 2005. Sabdabodhamımam. sa:The sentence and its significance Part-I to V.Institute of Pondicherry and Rashtriya SanskritSansthan, New Delhi.

Florian Wolf and Edward Gibson. 2005. Rep-resenting discourse coherence: A corpus-basedstudy. Journal of Computational Linguistics,31(2):249–287.

W. Xi, J. Lind, and E. Brill. 2004. Learning ef-fective ranking functions for newsgroup search.

In In Proceedings of 27th International ACM-SIGIR Conference on Research and Develop-ment in Information Retrieval (SIGIR 2004),pages 394–401, Sheffield, UK.

Nianwen Xue. 2005. Annotating discourse connec-tives in the chinese treebank. In Proceedings ofthe Workshop on Frontiers in Corpus Annota-tion II: Pie in the Sky, pages 84–91, Ann Arbor,Michigan. Association for Computational Lin-guistics.

Deniz Zeyrek and Bonnie Webber. 2008. A dis-course resource for turkish: Annotating dis-course connectives in the metu corpus. In The6th Workshop on Asian Language Resources(ALR 6), IJCNLP, pages 65–71, Hyderabad, In-dia. Asian Federation of Natural Language Pro-cessing.

Yuping Zhou and Nianwen Xue. 2012. Pdtb-stylediscourse annotation of chinese text. In Pro-ceedings of the 50th Annual Meeting of the As-sociation for Computational Linguistics, pages69–77, Jeju Island, Korea. The Association forComputational Linguistics.