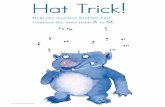

Help the monster find his hat! Connect the dots from A to M.

Chubby Cheeks and the Bloated Monster: The Politics of Reproduction in Mary Wollstonecraft's...

-

Upload

northgeorgia -

Category

Documents

-

view

4 -

download

0

Transcript of Chubby Cheeks and the Bloated Monster: The Politics of Reproduction in Mary Wollstonecraft's...

This article was downloaded by: [Diana Young]On: 02 November 2014, At: 16:15Publisher: RoutledgeInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registeredoffice: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

European Romantic ReviewPublication details, including instructions for authors andsubscription information:http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/gerr20

Chubby Cheeks and the BloatedMonster: The Politics of Reproductionin Mary Wollstonecraft's VindicationDiana Edelman-Younga

a Department of English, University of North Georgia, Oakwood,GA, USAPublished online: 29 Oct 2014.

To cite this article: Diana Edelman-Young (2014) Chubby Cheeks and the Bloated Monster: ThePolitics of Reproduction in Mary Wollstonecraft's Vindication , European Romantic Review, 25:6,683-704, DOI: 10.1080/10509585.2014.963850

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10509585.2014.963850

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the“Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis,our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as tothe accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinionsand views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors,and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Contentshould not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sourcesof information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims,proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever orhowsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arisingout of the use of the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Anysubstantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing,systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms &Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

Chubby Cheeks and the Bloated Monster: The Politicsof Reproduction in Mary Wollstonecraft’s Vindication

Diana Edelman-Young∗

Department of English, University of North Georgia, Oakwood, GA, USA

This article foregrounds a new context – natural and reproductive sciences – forinterpreting Wollstonecraft’s argument in The Vindication of the Rights ofWoman. Wollstonecraft’s language of fertility and sterility, which she links tothe health of the state and to the perfection of the human species via thediscourse of natural history, should be read in the contexts of important medicalissues of her day, such as the widespread problem of venereal disease and thebreastfeeding/wet nursing controversy. Tracing the moments in Vindicationwhen Wollstonecraft employs these various branches of science, I demonstratethat Wollstonecraft makes two important strategic, although subtle, moves in herargument for gender equality. First, she reassesses the male body and its materialeffects on individuals, the nation, and the species. Secondly, although criticshave charged her with essentialism, Wollstonecraft frequently implies thatbiology is culturally determined and, therefore, malleable.

The mere mention of the name Mary Wollstonecraft evokes a variety of images –Horace Walpole’s “hyena in petticoats,” Richard Polwhele’s “unsex’d females,” andthe breastfeeding puppies in her birthing room turned deathbed. The historical dimen-sions of Wollstonecraft’s work – Enlightened Dissent, the conduct book tradition, sen-timental fiction, the French Revolution, women’s rights, and the culture of sensibilityand its fiction – are as various as our images of her. This essay foregrounds thevarious scientific contexts of Wollstonecraft’s The Vindication of the Rights ofWoman. More specifically, Wollstonecraft engages with medical subjects and repro-ductive discourses in order to redefine the roles of men and women not only interms of their daily lives, but also in terms of their contributions to the evolution ofthe human species, which, I shall argue, she believes is gradually advancing towardsa genderless state. In order to fully understand Wollstonecraft’s redefinition of the“natural” and her argument for female equality, though, we must understand that shewas familiar with, influenced by, and actively engaged with many branches ofscience, including natural history or the natural sciences,1 embryology, obstetrics, mid-wifery, and physiology. She was also familiar with many important medical subjectsthat had serious social and cultural implications such as the widespread problem ofvenereal disease and the breastfeeding/wet nursing controversy. We see these branchesof science emerging at various points in Vindication through the work’s pervasive

# 2014 Taylor & Francis

∗Email: [email protected]

European Romantic Review, 2014Vol. 25, No. 6, 683–704, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10509585.2014.963850

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dia

na Y

oung

] at

16:

15 0

2 N

ovem

ber

2014

metaphors of health and disease, defined, in part, by male and female reproductivecapacities.

Wollstonecraft read widely on medical subjects, particularly through her associationwith Joseph Johnson, who published medical books and who was proprietor of theLondon Medical Journal from 1783–1790. Johnson’s dinners, which Wollstonecraftattended regularly, were likely to include discussions of medical subjects given thepresence of figures such as Dr. George Fordyce, author of Elements of the Practiceof Physic and doctor at St. Thomas’s hospital; and Erasmus Darwin, author of Lovesof the Plants (Gordon 130–31). As a writer for the Analytical Review, she reviewedseveral important scientific texts, including The Philosophy of Natural History(1790) by William Smellie, Scottish naturalist and printer2; A New System of theNatural History of Quadrupeds, Birds, Fishes, and Insects (1791); and a translationof the embryologist comte de Buffon’s Natural History, abridged (1791).3 She alsoreviewed Benjamin Lara’s An Essay on the injurious Custom of Mothers not sucklingtheir own Children (1791). In a note in Vindication, Wollstonecraft reveals that she has“conversed, as man with man, with medical men on anatomical subjects, and comparedthe proportions of the human body with artists” without ever being aware of, orreminded of, her sex (234).4 By “unsexing” herself – she has conversed as “manwith man” – Wollstonecraft places herself on the same footing with medical men,perhaps ones like those at Johnson’s dinners, suggesting to her readers that she hasas much credibility in defining the “natural” as her male colleagues. Her reviews ofmedical texts and conversations with medical men enabled her to both challenge andappropriate medical discourse.5

Wollstonecraft’s argument for equality rests on two central images in her essay. Thefirst comes from the following passage: “I think I see her surrounded by her children,reaping the reward of her care. The intelligent eye meets hers, whilst health and inno-cence smile on their chubby cheeks, and as they grow up the cares of life are lessenedby their grateful attention” (140). The second is its contrast: “Birth, riches, and everyextrinsic advantage that exalt a man above his fellows, without any mental exertion,sink him in reality below them. In proportion to this weakness, he is played upon bydesigning men, till the bloated monster has lost all traces of humanity” (132). Theseare the two extremes on Wollstonecraft’s continuum of social, political, and reproduc-tive health. The first is a portrait of Wollstonecraft’s ideal – a rational, maternal figurewho produces the “chubby cheeks” of a healthy baby. The second is its opposite –tyranny and degradation resulting in a “bloated monster.” As readers of Wollstonecraft,we can also imagine, to accompany the first image, another passage in which she writes,“Cold would be the heart of a husband, were he not rendered unnatural by earlydebauchery, who did not feel more delight at seeing his child suckled by its mother”(259). The healthy husband is an integral part of Wollstonecraft’s image of healthyreproduction and growth. By contrast, the “bloated monster,” gendered male, representsthe despotism and debauchery of cultural masculinity, which, for Wollstonecraft, is justas unnatural and physically dangerous as women’s corsets and an education in sensi-bility. While it is clear that Wollstonecraft grounds her argument in her belief thatwomen are reasonable, thinking creatures with souls (and, thus, more than bodily),there is another dimension to the argument that remains unexplored and that is fore-grounded, in part, by her knowledge of medical and reproductive subjects. Herprogram for gender equality emphasizes the material and physical nature of men,which she expresses through the language of fertility/health and sterility/disease.Throughout the Vindication, these two images, the chubby cheeks of fertility and the

684 D. Edelman-Young

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dia

na Y

oung

] at

16:

15 0

2 N

ovem

ber

2014

bloated monster of sterility, work together to suggest that both male and female areequally implicated in the future of the nation (and, ultimately, the species) and,further, that biology is culturally determined. Thus, although Wollstonecraft hasbeen charged with essentialism, her argument, when filtered through the scientifictexts and subjects with which she was familiar, demonstrates that she dismantles thegender divide not only at the rhetorical level, but also at the level of the body.6

Wollstonecraft’s dominant metaphor of the body politic is not an androgynous body,nor the usual male monarch’s body, but the bodies of a heterosexual couple. Both maleand female bodies must facilitate healthy reproduction before, during, and after con-ception. Using the rhetoric of reproductive health and the language of various branchesof scientific discourse, Wollstonecraft equates the future of England (and, by extension,any nation) with feminine and masculine virtue, thus advocating political, social, andeducational progress for women and men. In this way, Wollstonecraft can be read as par-ticipating in what Julie Kipp effectively argues are the “trials and errors of Romantic-period mothers, the politicizing of maternal bodies and the maternalizing of politicalbodies, and the authoring of mothers and the mothering of texts” (1).7 Wollstonecraft’swork participates in the “legal, medical, educational, and socioeconomic debates aboutmotherhood so popular during the period, discussions that rendered the physicalprocesses associated with mothering matters of national importance” (1). I would add,however, that Wollstonecraft’s argument extends beyond national and sexual bound-aries as evidenced by her ultimate concern – the human species. In her discussion ofMaria, or The Wrongs of Woman, Kipp explains that Wollstonecraft perceives maternal“instinct” as growing from habit, a performance of gender identity (82) and that the novel“calls into question the very possibility of maternal love in an environment which sodebases women’s bodies” (81). This debasement stems, in part, from the “suggestionthat the exclusive dependency of children on their mothers and substitute mothersmakes slaves of women” (81). Indeed, Maria dramatizes the suffering that resultswhen women’s bodies and minds are debased either from external forces or their owninternalization of patriarchal ideology, but more than that, the novel explores whathappens when the male body is left out of the question. The female and maternalbonds in the novel are strong despite suffering; the real problem here is that malebodies have not been circumscribed, a point Wollstonecraft repeatedly makes in Vindi-cation. Thus, Kipp is right when she says that Wollstonecraft explores the damaging con-sequences of the “exclusive dependency of children on their mothers” (81). The father’srole, in my interpretation of Wollstonecraft’s argument, has to be not just financial,political, or intellectual; it must be material, bodily.

The trajectory of Wollstonecraft’s argument begins the idea of biological perfect-ibility for humanity over time, a concept borrowed from natural history, and endswith the very practical consideration of professions for women in the here and now,which, significantly, require women to move beyond the domestic space and men toreturn to it. Throughout Vindication, Wollstonecraft offers simultaneously her assess-ment of the central problem in society – tyranny – and its solution – biological andpolitical equality. The negative images stem directly from tyranny and are related toreproductive health – the oversexed bodies of soldiers and prostitutes and the sterilebodies of dolls and machines. These images contrast directly with the solution,which is also centered on reproductive health: the robust, breastfeeding body and thevirtuous and chaste male body, both of which combat disease and deformity in individ-uals and the species. It is important to note from the outset that Wollstonecraft draws onboth popular and professional medical discourses and subjects without aligning herself

European Romantic Review 685

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dia

na Y

oung

] at

16:

15 0

2 N

ovem

ber

2014

to any one point of view. In doing so, she blurs the lines between traditional dichoto-mies – male/female, natural/unnatural, public/private, material/immaterial, popular/professional – a rhetorical move that makes the argument itself non-linear and multi-valent. Furthermore, although she rejects monolithic discourses such as medicine thatpromote gender tyranny, she does not abandon the useful knowledge offered by suchdiscourses, but uses them to demonstrate to her audience alternative ways of interpret-ing the evidence. More specifically, her argument rejects biologically based argumentsfor gender discrimination by using biology and physiology to argue the opposite; inother words, she “beats them at their own game.”8 It is also important to note herethat Wollstonecraft’s argument is not linear. Her argument is framed within the associ-ation between reproductive health and the evolution of the species, a concept sheborrows from natural history. Within that framework, her argument emerges moreclearly as we filter the material through various forays into the medical discoursesand subjects that she engaged with. Biological perfectibility, then, becomes thethread that ties together the various strands of her argument.

Through her reading and reviews of various natural histories, such as William Smel-lie’s The Philosophy of Natural History (1790) and a translation of the comte deBuffon’s Natural History (1791), Wollstonecraft encountered the proto-evolutionaryidea of the perfectibility of the human species. Wollstonecraft explains the history ofhumanity in reproductive terms, creating an organic metaphor in which the develop-ment of the species is teleologically driven towards a state of perfection, a metaphorthat contrasts directly with Newtonian mechanism and the fixed nature of class andgender politics implied by Edmund Burke’s emphasis on tradition. Wollstonecraftadopts a proto-evolutionary model that reads the human species as a constantly progres-sing organism, much like Naturphilosophie, which “regarded living nature as exhibit-ing fundamental organic types, often called ‘archetypes’” towards which elements ofthe natural world were progressing (Richards 8). Wollstonecraft frames her metaphorsof health and disease, fertility and sterility, in the context of natural history throughwhich she perceives society as a living organism subject to evolution and degeneration.

Natural history provides the scientific basis for her argument that culture affectsbiology and, further, that anything that interferes with healthy reproduction can be con-sidered unnatural or regressive.9 The sciences of the period, from natural history toembryology, often argued for male social and political superiority on a biologicalbasis; thus, Wollstonecraft’s use of these scientific paradigms not only establishesher credibility, but also refutes the “naturalness” of biological determinism. Followinga discussion of the superiority of males in most species in regards to physical strength,William Smellie, whose work Wollstonecraft reviewed for Johnson, writes that “asimilar observation is applicable to the minds of the two sexes” (236).10 Woman’sweakness of mind and physical delicacy puts her under man’s protection and, itfollows, that “in most governments, women have the entire management and trainingof children” (237). Thus, biology determines social and political roles in any givenculture. Even Smellie, though, subtly suggests that external forces can affect individualbodies when he writes that the “tyrannical” caste system of the Gentoos places“restraints on the natural liberty of man” (521) and that the maiming or removal ofone species on the hierarchy can affect the rest. He states that the “annihilation ofany one of these species . . . would make a blank in Nature, and prove destructive toother species . . . and the system of devastation would gradually proceed” (520).Although Smellie’s hierarchy is static, he suggests that the mistreatment of any creaturewithin the system could have disastrous consequences for all of the others.

686 D. Edelman-Young

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dia

na Y

oung

] at

16:

15 0

2 N

ovem

ber

2014

Wollstonecraft’s argument suggests agreement in regards to the interaction of the sexeswherein tyranny over one can create a “system of devastation.”

Buffon, whose work Wollstonecraft also reviewed, had a similar conception of theinteraction between biology and external forces as we can see in Smellie’s 1780 trans-lation. In the following passage, Buffon describes the process by which the species ofhumankind changes over time:

there was originally but one individual species of men, which, after being multiplied anddiffused over the whole surface of the earth, underwent divers changes, from the influenceof the climate, from the difference of food, and of the mode of living . . . at first, thesealterations were less considerable, and confined to individuals; that, afterwards, fromthe continued action of the above causes becoming more general, more sensible, andmore fixed, they formed varieties in the species . . . and that, in fine, as they wouldnever have been produced but by a concurrence of external and accidental causes, asthey would never have been confirmed and rendered permanent but by time . . . it ishighly probable, that in time they would in like manner gradually disappear, or evenbecome different from what they at present are, if such causes were no longer tosubsist, or if they were in any material point to vary. (2: 70; emphasis added)11

This passage suggests precisely the idea of evolution in that external forces such asclimate and diet can materially transform human beings making them diverse in skincolor, body type, facial features, and the like. Changes in the bodies of humansemerge from “external and accidental causes” (Buffon 2: 70). With enough time,changes in circumstance can affect the bodies of individuals and the species as awhole. It is precisely this idea of changing external circumstances, from physical exer-cise to political and social hierarchies, that Wollstonecraft explores throughout the Vin-dication. Wollstonecraft seeks to change the “mode of living” (Buffon 2: 70) inEngland, which should, at least according to the philosophy of prominent natural his-torians, eventually lead to a physical transformation of the species. Not surprisingly,Wollstonecraft, with the exception of some of his “independant and fanciful theories,”finds Buffon’s work “elegant,” useful, and “far preferable to those dry dictionariesrather than histories” (Works 7: 411).

Wollstonecraft’s perspective on humanity suggests that she is playing with this fra-mework of species hierarchy and evolutionary progress in order to rewrite the social/sexual contract in which men dominate women and in which humans are always infixed places within a hierarchy. In the Vindication, Wollstonecraft writes that societygestates in the “womb of time” (184) and, like the fetus, is susceptible to malformationand disease. The historical epoch “when men were just emerging out of barbarism” isthe “infancy of society” (98), which then matures through aristocracy, feudalism, mon-archy, and tyranny until the intellectual freedom of “true civilization” perfects society(99). Besides her frequent references to the “human species” and the “animal kingdom”throughout the Vindication, Wollstonecraft explicitly states that there is but “one archi-type for man” (119), a term that recalls the “archetype” of Naturphilosophie. AlthoughWollstonecraft is here writing about one standard of morality for men and women –“one criterion of morals” (119) – she clearly advocates the notion that humans are per-fectible not only in morals but also in body and mind. Humans, she writes, are the“perfect model” of species perfection in contrast to the “brutes,” which rely on instinctand not reason (119). Because women have reason, she argues, they should be con-sidered, along with men, as evolving towards moral and physical perfection –towards the “one architype” (119). This idea emerges clearly in William Smellie’s

European Romantic Review 687

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dia

na Y

oung

] at

16:

15 0

2 N

ovem

ber

2014

text when he writes that “In the change of animals, man is unquestionably the chief orcapital link, and from him all the other links descend by almost imperceptible grada-tions. As a highly rational animal, improved with science and arts, he is, in somemeasure, related to beings of a superior order, wherever they exist” (520–21).Although he is merely subscribing here to the idea of the Great Chain of Being inwhich each creature has a fixed station within a larger system, he suggests that edu-cation, politics, and culture can affect that system; people can be “improved withscience and arts.”

More like Buffon who argued that a “concurrence of external and accidental causes”leads to material changes in the species (I.70), Wollstonecraft takes Smellie’s hierarchalplan one step further by suggesting that humankind as a whole can evolve and devolve.In her review of Smellie’s The Philosophy of Natural History, she writes that the“human species, considered collectively, appear to have an infancy, youth, etc. –Has any thing similar ever been observed in the brute creation?” (7: 297). In fact,she continues, brutes can only pass on physical traits to their young, not mentalones. Man outclasses brutes in his ability to reason, which can lead to both vice andvirtue, and ultimately to the degeneration or progression of humankind, dependingon whether they “practice self-denial” or “fall into excess” (7: 298). Further, educationcan assist to “form a being advancing gradually towards perfection” where the “sexual[does] not destroy the human character” (Vindication 144; emphasis added). In thisway, the surrounding culture (the self-denial and the excesses) can lead to physicalchanges or degeneration for the individual and for society as a whole. Self-denialand reason create the “chubby cheeks” of health whereas excess degenerates into the“bloated monster.” Significantly, the perfect “being” towards which we are advancingis neither male nor female, indicating that gender emerges from cultural context, notbiological necessity. Even Smellie suggests that there is a class of beings abovehumans when he writes that the human species is “improved with science and arts”(external forces) and thus “related to beings of a superior order” (520–21). These“beings” are sexless. Although Smellie shuts down the discussion by asserting thatquestioning Nature is “petulant and presumptuous” (521), his overall argumentimplies that external forces can affect the system and the beings within it, particularlyhumans. Wollstonecraft’s Vindication takes these suggestions to their logical con-clusion in regards to the sexes – biological perfectibility in which sex is eventuallysloughed off in favor of “beings” of a superior order.

The frame of contemporary studies in natural history and perfectibility of the speciesenables readers of Wollstonecraft to appreciate that her language of health and disease ismore than metaphorical; culture and education have physical consequences for the indi-vidual, the nation, and, ultimately, the species. On the one hand, excess and tyranny leadto the bloated, the sickly, the stunted, the artificial, and the sterile. On the other, self-denial, reason, and equality produce the healthy, robust, organic, and fertile. Considerone of Wollstonecraft’s central comparisons – women and soldiers – in which sheblurs gender lines in order to make her claim. Wollstonecraft writes,

Standing armies can never consist of resolute robust men; they may be well-disciplinesmachines, but they will seldom contain men under the influence of strong passions, orwith very vigorous faculties; and as for any depth of understanding, I will venture toaffirm that it is as rarely to be found in the army as amongst women. And the cause,I maintain, is the same . . . Like the fair sex, the business of their lives is gallantry.(106; emphasis in original)

688 D. Edelman-Young

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dia

na Y

oung

] at

16:

15 0

2 N

ovem

ber

2014

Soldiers are merely machines taught to please; as such, their minds and bodies are ham-pered. They are neither robust nor intellectually vigorous. Similarly, gender hierarchyproduces women who are mere machines for reproduction: “riches and hereditaryhonours have made cyphers of women to give consequence to the numerical figure”(106–7). In other words, women’s bodies are machines to add numbers to our popu-lation, a problematic endeavour in the context of poverty and war. Women’s bodiesare “enervated by confinement” and produce only “half-formed limbs” (105). Soldiersare machines, and women “cyphers,” both empty, sterile, and, in Wollstonecraft’s view,regressive. Thus, social structures have physical consequences for individuals and thespecies. Tyranny causes a regression from the “true civilization” of a perfect society(99) in which there is but “one architype for men” (119). The comparison betweenwomen and soldiers blurs the gender lines by suggesting that education produces thesame results regardless of the sex of the person being educated. Neither womenschooled in coquetry nor soldiers schooled in gallantry can move towards the perfect“being” because their education affects their physical well-being and their reproductivecapacity.

In addition to blurring the distinctions between male and female in this comparison,Wollstonecraft’s reference to soldiers draws on the more immediate public healthproblem associated with them and which was directly linked to reproductive health.Her reference to soldiers evokes the social problem of venereal disease as soldierswere infamous for the use of prostitutes and the spread of diseases, particularly syphilis.12

According to Claude Quetel, syphilis was one of the social diseases that “caused the most,and the blackest, ink to flow” (2). Indeed, the black ink “flowed” on the subject of vener-eal disease during this period; treatments for venereal disease were the most commonadvertisements in eighteenth-century periodicals (Stone 600). Further, “by the end ofthe eighteenth century, political and social leaders in Britain and France perceived vener-eal disease to be, in real and imagined ways, an extremely serious threat to the political,economic, and spiritual well-being of their nations” (Merians 2). Given these facts, itseems certain that Wollstonecraft’s readers would have understood her references to sol-diers within that context. It was not just debauched men and prostitutes who were con-tracting these diseases. Wives suffered because of profligate husbands (Stewart), andchildren, it was feared, could be infected by their lower class wet nurses (Dunlap119–20).

Wollstonecraft’s readings in natural history also register this problem. JohnReinhold Forster, whom Wollstonecraft quotes at length in her discussion of polygamy(discussed below), cites venereal disease as one of the chief diseases of soldiers andsailors. He writes, “The venereal disease was very frequent among our ships-company, so that sometimes thirty or forty persons were at once infected” (641).Even Smellie writes of this problem, lamenting that “we have too many examples ofchildren, immediately after birth, becoming innocent victims of their parents debauch-ery” (2: 138).13 He suggests later that it is European education and cultivation that is thecause of spreading this contagion among the “savages”: “It is painful to learn, that theintercourse of these once happy and healthy people with what we call refinedEuropeans, should have entailed upon them, perhaps for ever, that dreadful scourgethe venereal disease!” (2: 263; emphasis in original). The sarcastic tone of the italicized“refined” indicates that unnatural education and distinctions can often lead to excessesthat have “calamitous and deleterious effects” (2: 264) on reproduction. The spread ofthis European disease among the “savages” occurred, no doubt, through soldiers andsailors. When Wollstonecraft’s language of contagion and references to soldiers are

European Romantic Review 689

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dia

na Y

oung

] at

16:

15 0

2 N

ovem

ber

2014

put in dialogue with the writings of Smellie and others, we see one of the ways in whichshe “aligns herself with certain male and metropolitan natural histories both to undercuttheir complacent assertions and to coopt them for her own purposes” (Ryall 118). In thiscase, she is coopting them in order to demonstrate the consequences of tyranny onactual bodies, not only abroad but also at home.

Europeans spread this disease abroad as they travelled and suffered from it on theirown soil. This epidemic, significantly known as the contagion depopulatrice, threa-tened not only to eliminate citizens, but also to deform them permanently (Conner17). Some of the symptoms of syphilis include the appearance of chancres on the gen-itals, pustulae all over the body, “intense pains in . . . limbs and joints,” tumors, and inthe final stage, “the destruction of the bones [wherein] the limbs affected remain per-manently twisted or stunted” (Quetel 26). Wollstonecraft’s term “enervated” (105),which she uses throughout Vindication, echoes the syphilitic attack on the nerves. Simi-larly, her references to “half-formed limbs” (105) indicate the twisted and stuntedgrowth that was also one of its symptoms. Later on in Vindication, she refers toactual prostitutes, not just metaphorical ones. She once again associates soldiers withprostitution and contagion when she quotes the poet John Gay: “And every soldierhath his charms; / From tent to tent she spreads her flame” (232). The intense painsand inflammation caused by syphilis in particular are evoked in this metaphoricalflame spread by the prostitute and her soldier/lover. The hierarchies of military lifeand a gendered society lead to physical and intellectual deformity and, eventually, steri-lity. Indeed, “unnatural distinctions” (106) create disfigured bodies in both cases, a hintthat biology conforms to culture. Man’s “fall into excess” (7: 298), as she wrote in herreview of Smellie, retards his movement towards the “one architype” (119). Again, it isin moments like these that we see Wollstonecraft establishing her credibility to traffic inmale-dominated scientific discourse and to argue against external forces that renderwomen inferior.

Another component of Wollstonecraft’s belief that biology is culturally determinedis the popular and professional concept of oversatiation. The bodies of soldiers andwomen are compromised, according to this contemporary medical belief that toomuch sex weakens the body and its reproductive powers, which, some doctorsargued, was the reason prostitutes rarely conceive. The theory of oversatiation, withwhich her audience was no doubt familiar, allows Wollstonecraft to erode the culturalbelief that males are “naturally” promiscuous and females “naturally” pure. By break-ing down this association, she can argue that sexual and reproductive health is a mutualbusiness. The medical sources of the theory of oversatiation are numerous. Smellie isone of them. He writes that the inhabitants of Guinea rarely reach old age essentiallybecause of too much sex: “A Negroe of fifty years is a very old man. Their prematureintercourse with the females may be one cause, at least, of the shortness of their lives”(2: 215). William Buchan, author of Domestic Medicine, states, “It is impossible that acourse of vice should not spoil the best constitution” (6). The author of Aristotle’sMasterpiece, another popular sex manual, asserts that “too frequent copulation isalso one great cause of barrenness in men” (Salmon 262). Notice that the barrennessis not just women, but men as well. William St. Clair explains that Aristotle’s Master-piece was a work “everybody knew” and was mentioned in Laurence Sterne’s TristramShandy, which Wollstonecraft read (501). St. Clair writes, “there are numerous indi-cations scattered through the writings of Godwin and Wollstonecraft that they sharedthe common belief that frequent sex reduces fertility” (501). For Wollstonecraft, thismedical “truth” proves that sexual excess retards human progress – soldiers who

690 D. Edelman-Young

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dia

na Y

oung

] at

16:

15 0

2 N

ovem

ber

2014

solicit prostitutes, wives treated like prostitutes, and debauched husbands who want aplaything for a wife. These soldiers clearly represent the “fall into excess” that Woll-stonecraft mentions in her review of William Smellie’s The Philosophy of NaturalHistory wherein she unites individual behavior with the perfection of society (7: 298).

Sexual debauchery “has an equally fatal effect on population and morals,” Wollsto-necraft writes (Vindication 255). Anything that hinders healthy fertility hinders humanperfectibility and supports Wollstonecraft’s call for a social structure that encouragesintellectual and physical equality between men and women as the species advances“gradually towards perfection” (144). Her apparent acceptance of this theory doesnot necessarily indicate that she agrees with the rest of the science that accompaniesit in the works of Smellie and the like. Her problem with oversatiation, as with soldiersspreading venereal disease, is not primarily the sexuality involved but the gendertyranny that supports it. The concept of oversatiation, which hinders this progress,makes its way into the following passage:

Contrasting the humanity of the present age with the barbarism of antiquity, great stresshas been laid on the savage custom of exposing the children whom their parents could notmaintain; whilst the man of sensibility, who thus, perhaps, complains, by his promiscuousamours produces a most destructive barrenness and contagious flagitiousness of manners.Surely nature never intended that women, by satisfying an appetite, should frustrate thevery purpose for which it was implanted? (255; emphasis added)

Worse than parents who practice infanticide, the dandy spreads a “destructive barren-ness” throughout the female population; his manner and his diseases are “contagious”(255). The “unchaste man doubly defeats the purpose of Nature, by rendering womenbarren, and destroying his own constitution, though he avoids the shame that pursuesthe crime in the other sex” (256). Oversatiation and venereal disease affect the repro-ductive powers of both men and women, signifying a biological basis and medical jus-tification for Wollstonecraft’s program for equality; thus, she turns the discourse againstitself by offering alternative interpretations of the evidence. Men must remain chasteand consider their own bodily limitations as much as women do, for their practice of“self-denial” or “fall into excess” (7: 298) can determine the fate of the individual,the nation, and the species.

The language of oversatiation also arises in Wollstonecraft’s argument againstpolygamy, which she identifies as “another physical degradation” of women and thebasis for an erroneous argument for women’s inferiority. Some argue, Wollstonecraftwrites, that “in the countries where [polygamy] is established, more females are bornthan males” and further that “if polygamy be necessary, woman must be inferior toman, and made for him” (166). Wollstonecraft refutes this argument by demonstratingthat cultural practice – in this case, polygamy – leads to physical consequences forboth men and women:

With respect to the formation of the foetus in the womb, we are very ignorant; but itappears to me probable, that an accidental physical cause may account for this phenom-enon, and prove it not to be a law of nature. I have met with some pertinent observationson the subject in Foster’s Account of the Isles of the South Sea, that will explain mymeaning. After observing that of the two sexes amongst animals, the most vigorousand hottest constitution always prevails, and produces its kind; he adds, – “If this beapplied to the inhabitants of Africa, it is evident that the men there, accustomed to polyg-amy, are enervated by the use of so many women, and therefore less vigorous; the women,on the contrary, are of a hotter constitution, not only on account of their more irritable

European Romantic Review 691

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dia

na Y

oung

] at

16:

15 0

2 N

ovem

ber

2014

nerves, more sensible organization, and more lively fancy; but likewise because they aredeprived in their matrimony of that share of physical love which, in a monogamous con-dition, would be all theirs; and thus, for the above reasons, the generality of children areborn females.” (166)

Wollstonecraft quotes John Reinhold Forster who argues that African men, becausethey have to please many wives, weaken their seed, which then has less power in deter-mining the sex of the fetus. Polygamy, then, is one of those external causes, one ofthose “mode[s] of living” that affect the evolution of the species (Buffon 2: 70).

Wollstonecraft’s mention of the effects of cultural practice on fetal formation in thecontext of this overtly political document is not an anomalous digression but a clearindication of the way in which she harnesses scientific discourse to argue for genderequality. Wollstonecraft admits that “we are very ignorant” in respect to exactly howthe fetus comes into existence and how it develops over time (166). She explains,though, that an “accidental physical cause” – oversatiation – may be the reasonwhy more females are born than males in these societies, at least according toForster. Interestingly, Forster’s argument goes on to discuss societies in which theopposite happens for the same reason. Among the ancient Britons and the people ofMalabar and Tibet, women are allowed to have more than one husband, leading to over-satiation and a preponderance of males born (428–29). He argues, “Strange and unna-tural as this custom may appear, it is however, not less true, and owes its originundoubtedly to peculiar causes” (429). Like Forster, Wollstonecraft suggests thatpolygamy, and other such degradations to equality, is the result of accident, ratherthan laws of nature. The men in Africa are “enervated by the use of so manywomen” and are “less vigorous” (qtd. in Wollstonecraft 166). As with soldiers, debau-chees, and doll-like wives turned prostitutes, the men of Africa are weak and lack vigor.She evokes the theory of oversatiation to demonstrate the need for male chastity and toindicate that cultural practice has physical and biological consequences. Polygamy isbased on gender hierarchy and tyranny; thus, it is regressive and hampers human evol-ution. She would agree, I believe, with Forster’s ultimate analysis of this problem:“monogamy seems to be the true and best means for perpetuating and encreasingmankind; yet when man is degenerated and debased by vicious habits . . . we find poly-gyny and polyandry likewise employed” (431; emphasis in original). Using Forster,Wollstonecraft harnesses the language of natural history or the natural sciences to chal-lenge gender hierarchies and to demonstrate that culture has biological consequences.She turns scientific discourse against itself by eroding traditional hierarchies and associ-ations – dominant, oversexed men over dependent, chaste women.

Another reading of this passage indicates that she is evoking some important con-temporary theories of fetal formation and development. Wollstonecraft’s comments onpolygamy intimate that some theories of embryology, and indeed, any science that usesbiology to justify women’s inferiority, number among the causes of women’s degra-dation because they support the “natural” subordination of women. Paul Youngquistargues that this passage “advances an account of conception that contradicts contem-porary anatomical knowledge” (150). Her argument, using Forster, “suggests thatfemale vitality as much as male determines sex at conception” (Youngquist 150).This notion is in direct contrast to Aristotle and later embryologists, such as WilliamHarvey, who argued that woman contributed only the physical material (as opposedto the creative force/seed) to the fetus, thus reducing her body to a mere incubator.14

This concept is echoed throughout Vindication when Wollstonecraft writes that

692 D. Edelman-Young

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dia

na Y

oung

] at

16:

15 0

2 N

ovem

ber

2014

women are treated as “mere propagators of fools” (83) and “cyphers” (107), who are“born only to procreate and rot” (157). Her view of reproduction is more likeBuffon’s who writes, “I conceive, therefore, that the seminal fluids, both of the maleand of the female, are equally active, and equally necessary for the purposes of propa-gation: And this, I think, is fully proven by my experiments” (2: 274). Unlike Aristo-tle’s, this theory equates woman’s role with man’s. Both active and creative, she is nolonger merely material, nor merely an incubator. Whenever Wollstonecraft indicts bothmen and women for the failures of healthy reproduction, she indicates that “conceptionis the business of both parties, not just one animating force” and, therefore, challenges“the silent assumption of liberalism that bodily life indebts women to men” (Young-quist 150–51). By claiming, in part, a biological reason for gender equality, Wollstone-craft is not so much essentializing gender as turning the language of the dominantdiscourse against itself.15 She takes on the scientific gaze to claim authority and demon-strate that, in terms of reproductive health and the future of the state, men and womenmust be placed on equal footing in every way – biologically, politically, socially.

In addition to evoking embryology in this particular passage, throughout Vindi-cation, Wollstonecraft subtly challenges gendered physiology, a biological discoursethat demands a certain functional norm for women’s bodies. “Natural” delicacy – thefoundation of female physiology and one of Wollstonecraft’s main points ofcontention with writers such as Rousseau, Fordyce, and Gregory – finds support inSmellie’s writings to whom she seems to be reacting. Smellie says that “Women . . .are timid, jealous, and disposed to actions which require less agility and strength”(375). He links these character traits to physical causes: “the laxity and softness oftheir texture may, in some measure, account for the timidity and littleness of their dis-position” (375). Thus, their role is to support men by inspiring them to noble actions:“their little female humours, caprices, and follies, give rise to many exertions ofvirtue . . . The delicacy of their bodies, and the weakness of their minds, require oursupport and protection” (375). While she is talking primarily about Smellie’s rejectionof Linnaeus’s sexual system of plants, which she believes is a “beautiful analogy,”Wollstonecraft is most critical of this section of Smellie’s work in her review. Shewrites, “We cannot avoid observing that this part of the subject is treated in rather adogmatic manner, nor do we see the force of Mr. S’s reason for dwelling so long onthe topic” (7: 296). Perhaps she is reacting to Smellie’s rather overwrought image ofpollen “flying promiscuously abroad” and impregnating different species; this botanicalmiscegenation would create “universal anarchy among the vegetable tribes” and result in“monstrous productions, which no botanist could either recognise or unravel” (247).While Smellie insists on “facts” for his disputation against Linnaeus, he does not doso in regards to the assumptions about male and female bodies with which he beginsthis section. His gendered physiology supports the “false notions of modesty” thatcreate the “half-formed limbs,” which Wollstonecraft reads as blights on freedom andhuman improvement (105). For Smellie, female weakness of mind and body supportstheir subjugation by the stronger and wiser male. Wollstonecraft reverses thisformula. Child-like wives who nurse a sickly delicacy result only in a “barren blooming”(79), rendering women unfit to bear, nurse and educate their children.

Wollstonecraft’s challenge to Smellie and similar writers enables her to argue thatthe body succumbs to socialization and, further, that delicacy causes sterility, not ferti-lity. The physical confinement of women, beginning with the discouragement of rigor-ous exercise for young girls, creates weakness and directly affects their ability toconceive and to mother:

European Romantic Review 693

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dia

na Y

oung

] at

16:

15 0

2 N

ovem

ber

2014

Nature has given woman a weaker frame than man; but, to ensure her husband’s affec-tions, must a wife, who, by the exercise of her mind and body whilst she was dischargingthe duties of a daughter, wife, and mother, has allowed her constitution to retain its naturalstrength, and her nerves a healthy tone, – is she, I say, to condescend to use art, and feigna sickly delicacy, in order to secure her husband’s affection? (112)

Exercise better enables a woman to be a daughter, wife, and mother because it gives herstrong limbs and healthy nerves, assets not only in bearing, nursing, and educating chil-dren, but also in actively fulfilling professional and civic duties, which she discussestowards the end of her treatise. Wollstonecraft concedes that in general “Nature hasgiven woman a weaker frame than man,” but she protests that woman’s frame is natu-rally delicate. She argues for the improvement of “natural strength” against the “sicklydelicacy” that society encourages women and girls to cultivate. For Wollstonecraft,physical and mental strength are imperative for healthy reproduction necessary forthe improvement of the individual, the nation, and the species.

Although Wollstonecraft concedes that man has physical superiority over woman,there are moments in her writing when she indicates doubt, signifying the notion thatbiology is culturally constructed and can be changed through education and a reformationof social and political structures, what Buffon would call “mode[s] of living” (2: 70). Citingthe passages in which Wollstonecraft allows for the superiority of male strength, Young-quist believes that Wollstonecraft “accepts the biology of incommensurability that in herday distinguishes male and female but claims for bodies of both kinds the capacity todevelop independent agency” (148). In this way, she navigates the Scylla and Charybdisof sexual difference and biologically based separate spheres. Coupled with her beliefthat humans are striving towards the “one architype” (119) to “form a being advancinggradually towards perfection” (144; emphasis added), Wollstonecraft implies that biologi-cal difference is based, in part, on culture. While Youngquist and others understandablyemphasize Wollstonecraft’s focus on the female capacity to reason, I would argue thather plan equally addresses the material agency of the male body, thus bringing both to alevel of physical and intellectual equality. She not only adds intellect/reason to woman,but also adds materiality to man. Historically, men have been treated as transcending thebody, but Wollstonecraft adds that back into the equation.

Further, neither body, if socially constructed, gains power over the other. In fact, sheleaves the “naturalness” of superior masculine strength open to question. She writes,

In the government of the physical world it is observable that the female in point of strengthis, in general, inferior to the male. This is the law of Nature; and it does not appear to besuspended or abrogated in favour of woman. (80; emphasis added)

Although she calls it a “law of Nature,” the phrases “in general” and “does not appear”suggest that “Nature” may be operating at a level beyond human observation; like manyscientists before her, Wollstonecraft refers to the limitations of human perception todemonstrate that what we observe with the eye is not the final answer.

This doubt about the fixed nature of biology is more pronounced in the followingpassage from the chapter on “National Education”:

I believe that the human form must have been far more beautiful than it is at present,because extreme indolence, barbarous ligatures, and many causes, which forcibly acton it, in our luxurious state of society, did not retard its expansion, or render it deformed.(297)

694 D. Edelman-Young

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dia

na Y

oung

] at

16:

15 0

2 N

ovem

ber

2014

Forster, whom Wollstonecraft cited in the passage on polygamy discussed above, makesa similar claim when writing about the South Seas islanders. Their bodies are healthy andproduce “numerous offspring” because they are “fortunate enough to have none of theartificial wants, which luxury, avarice, and ambition have introduced among Europeans”(216). He goes on to state that European avarice, climate, and “the many difficulties pre-ceding and attendant on our marriages, will be sufficient to prove, that in the naturalcourse of things, population must be great in these happy regions” (216). Externalforces, Forster implies, affect the body and, ultimately, the species. He states this ideamore plainly when he writes that external forces “sooner or later . . . cause distinctionsof rank, and the various degrees of power, influence, and wealth . . . Nay, they oftenproduce a material difference in the colour, habits, and forms of the human species”(226). Conceptual distinctions have material consequences for actual bodies. Interest-ingly, he even mentions the difficulties “attendant on our marriages” (216), indicating,perhaps, that marriage laws, inequities, and cultural practices affect the development ofthe species. Wollstonecraft’s argument is similar: education, morals, unnatural hierar-chies number among the “many causes” that can actually affect the human form, notthe least of which is the distinction between the sexes, which is really only “in thepresent state of things” (264; emphasis added). These subtle moments in the textleave the door open for sex itself to be other than biologically based; sex is a“concept” shaped by external factors.

Wollstonecraft identifies the problems created by unnatural hierarchies and oppres-sive governments – weak and sterile male bodies, sickly female bodies, deformedprogeny, bloated monsters. At the same time she offers the solution – material manand intellectual woman. Throughout the Vindication, images of reproductive health,notably represented by masculine chastity and maternal breastfeeding, contrast thesterile, diseased, and bloated bodies of the soldier-machines and doll-wives discussedearlier. Although Wollstonecraft treats breastfeeding as one of the few “natural” dutiesof woman, the history of the breast complicates the “naturalness” of its biological func-tion and illustrates that culture imbues the breast with different significations at differ-ent times.16 In “Colonizing the Breast,” Ruth Perry argues that “motherhood, thatcentrally important sentimental trope of late eighteenth-century English literature,effected the colonization of women for heterosexual productive relations” (209) andfurther that breastfeeding became part of the colonization of the female body inwhich the sexual was replaced with the maternal function. The medical literature advo-cated breastfeeding for “their own sakes [mothers], for the health of their children, andoften the good of the nation” (216). Upon first glance, it appears that Wollstonecraft ispart of this discourse, for she does advocate breastfeeding and ties it to the health of thestate as Perry points out (209); however, Wollstonecraft’s version, read within theframe work of natural history that I discussed above, creates a material role forthe male in the breastfeeding process. In this way, Wollstonecraft “colonizes” themale body, bringing both material and political equality to the sexes.

For Wollstonecraft, the breast achieves political significance and does not keepwoman in the home, as the patriarchal argument goes, but brings her out of it. Breast-feeding, especially when supported by the robust, chaste male, is the rhetorical and bio-logical counterpoint to Wollstonecraft’s images of sterility, deformity, and illness. It isa biological and political duty that maintains health and prevents pregnancy, thuscurbing the debilitating effects of poverty and overpopulation. In 1752, just a fewyears prior to Wollstonecraft’s birth, Carl Linnaeus published a treatise translated asStep-Nurse or Unnatural Mother, in which, according to Marilyn Yalom, he “insisted

European Romantic Review 695

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dia

na Y

oung

] at

16:

15 0

2 N

ovem

ber

2014

that wet nursing violated the laws of nature and endangered the life of both mother andchild” (108). Significantly, as Yalom points out, Linnaeus developed his system ofclassification based on the breast – mammals are defined as those who suckle theiryoung, shifting the breast to a new position of power in a scientific paradigm. Wollsto-necraft’s image of breastfeeding participates in this scientific paradigm as well as in therevolutionary climate of French republican principles with its recurrent depictions ofLiberty as a topless woman whose “pure milk” was “implicitly compared with thetainted milk of ancien-regime aristocrats, most of whom were raised by wet nurses”(Yalom 116). Wollstonecraft’s emphasis on breastfeeding enables her to challenge tra-ditional notions of what is “natural” that militate against the power of the breast as acheck against poverty and vice through the maternal bond and its physical healthbenefits, including contraception.17

Because women are denied a share of political power, Wollstonecraft politicizes her“natural” duties – breastfeeding – and uses medical discourse for support, specificallydeploying the link between nursing and birth control:

For Nature has so wisely ordered things, that did women suckle their children, they wouldpreserve their own health, and there would be such an interval between the birth of eachchild, that we should seldom see a houseful of babes. (323)

Breastfeeding, healthy for mother, child, and society, raises woman to the level of a pol-itical being not only because she produces future citizens, but also because the health ofthe next generation affects the health of humankind as beings advancing towards per-fection. Further, the notion that breastfeeding creates an “interval between the birth ofeach child” draws not only on medical warnings against sexual intercourse during thebreastfeeding months but also on the popular belief that breastfeeding functions as aform of contraception. Breastfeeding as birth control endows woman with powerover social ills, such as poverty created by having too many children one cannotsupport, and thus reinforces Wollstonecraft’s argument that woman is a political andsocial being beyond the domestic sphere. Perry argues that Wollstonecraft’s commentson breastfeeding “[reinscribe] here the mutually exclusive nature of sexuality andmaternity” (217); indeed, it does seem that Wollstonecraft essentializes gender by locat-ing woman’s function in the womb and the breast. At the same time, throughout Vin-dication there is ample evidence that Wollstonecraft finds each role – sex goddess anddomestic goddess – equally untenable because they are based on a fundamental depen-dence on patriarchal authority. Although she does participate in the sentimental trope ofthe breastfeeding mother and its link to national health, the lens of natural history withwhich we began enables us to see the ways in which she attempts to move beyond tra-ditional gender categories especially when she makes the male body a material realityessential to the breastfeeding process.18

Breastfeeding is primarily the mother’s role; however, the robust male is a signifi-cant part of the process because, if he is not “domesticated” or chaste, his licentiousbehavior will cripple and sterilize him, his wife, and his children through the spreadof venereal disease. Wollstonecraft asserts quite boldly that “all the causes of femaleweakness, as well as depravity . . . branch out of one grand cause – want of chastityin men” (254; emphasis added). If men cannot remain chaste, they will “destroy theembryo in the womb” or create “only an half-formed being” and spread the “taint ofthe same folly” among women (255). Further, it is inequality that exacerbates theproblem extending to the next generation, which flows from a “poisoned fountain”

696 D. Edelman-Young

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dia

na Y

oung

] at

16:

15 0

2 N

ovem

ber

2014

(257). Interestingly, the term “hereditary taint” became a “coded reference” for syphilisin the eighteenth century (Dunlap 116). The “taint” of venereal disease appears in HughDownman’s poem, “Infancy, or the Management of Children, a didactic poem” (1776),which Wollstonecraft reviewed for Johnson in 1789 (7: 114–15). In a passage encoura-ging mothers to breastfeed their own babies, Downman, a pediatrician, asks, “who canassure the lacteal Springs / Pure and untainted?” (1.155–56). The “blasted Child” then“propagates th’ hereditary Plague” and invites the “bitter Curse / Of Generations yetunborn” (1. 161, 165–67). The references to “taint” and “Plague” suggests thespread of venereal disease through the wet nurse’s milk. The physical viciousness ofa tainted ancestry finds expression in treatises on venereal disease. Dr. John Profilycalls venereal disease a “Tyranny” that “seizes the human Body” and creates avariety of reproductive problems, including barrenness and miscarriage (9).Dr. J. Smyth, medical doctor and man-midwife, asserts that the “whole nervoussystem becomes impoverished” by this poison (35). Wollstonecraft’s references to“nerveless limbs” and her frequent use of the terms “enervated” and “taint” evokethis issue as she argues that both men and women must contribute to the breastfeedingprocess.

Wollstonecraft, as she does with natural history, embryology, and physiology, usesthe medical discourse on breastfeeding to reverse the traditional formula that requireswomen to remain at home because they are “naturally” weaker and need to care forthe children. Although she agrees with the medical community’s stress on woman’sbiological role in terms of breastfeeding, she transforms biology into politics by rhet-orically entwining reproduction, nation, and society. The breast then becomes thesite of power because it is both biological and political, giving woman power bothwithin and outside the home. Wollstonecraft creates an emotional picture of a“woman nursing her children, and discharging the duties of her station” (260), a senti-mental portrait that gives great power to the role of mother, for “the wife, in the presentstate of things, who is faithful to her husband, and neither suckles nor educates her chil-dren, scarcely deserves the name of a wife, and has no right to that of a citizen” (264).Wollstonecraft’s phrase “scarcely deserves the name” of parent echoes WilliamBuchan’s assertion that “a mother who abandons the fruit of her womb, as soon as itis born, to the sole care of an hireling, hardly deserves the name of a parent” (4; empha-sis added). The similarity of language here indicates Wollstonecraft’s familiarity withBuchan, author of Domestic Medicine, the most popular medical book of the period.While both Buchan’s and Wollstonecraft’s language here is harsh and restrictive(and apparently fits in with what Bowers argues is a prescriptive, monolithic notionof motherhood), Wollstonecraft tempers her criticism with the following: “in thepresent state of things” (264). Again, we know only so much now about the bodyand its functions. She leaves the door open for social and cultural changes to occurthat will create different bodily norms, but for now the mother who breastfeeds is agood citizen, not because she produces soldiers to die for the state, but because she con-tributes to the overall health of herself and future generations who are moving societytowards physical, moral, and civil perfection. Breastfeeding can recreate the beautifulhuman form that Wollstonecraft speculates has been destroyed by the “luxurious stateof society” (297).

Whereas “unnatural mothers” (272) follow the transitory dictates of fashionablelife, true mothers abandon social prejudices because the “care of children in theirinfancy is one of the grand duties annexed to the female character by nature” (271).Emphasizing the maternal role enables Wollstonecraft subtly to stay within the status

European Romantic Review 697

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dia

na Y

oung

] at

16:

15 0

2 N

ovem

ber

2014

quo, but she shifts the argument to lobby for a greater portion of reason and educationfor women. “Their first duty is to find themselves as rational creatures,” says Wollstone-craft, “and the next, in point of importance, as citizens, is that . . . of a mother” (263).Wollstonecraft subordinates the biological role to the political – reasonable beingsbefore mothers. Reasonable mothers make “better citizens” because their babes arenot sent “to nestle in a strange bosom, having never found a home in their mother’s”(269). The child’s first sense of home and loyalty is the mother’s breast, themetonym of “mother country.” Her argument does not end there, for the father’s roleis significant as well. He must support her by staying home and remaining chaste, avery different version of gender roles from that which was typical during this period.The “unchaste man doubly defeats the purpose of Nature, by rendering womenbarren, and destroying his own constitution” (256); further, it is necessary that thewife and child receive the father’s “caresses” as he fulfills the “serious duties of hisstation” (259). The “chubby cheeks” of health and equality cannot be achievedwithout both doing their duty and, in the case of breastfeeding, it is the father’s roleto support the mother, not the other way around.

Although this emphasis on breastfeeding as a natural duty might invite charges ofessentialism against Wollstonecraft, it is clear from context that her program for equal-ity does not end with women in the home producing good citizens. In fact, in thepassage where Wollstonecraft inveighs against the mother who does not breastfeedas not having the “right” to be called a citizen (264), she qualifies her remark withthe following: “in the present state of things” (264). As things are now when wehave not yet reached social and biological perfection, this is her role, but even then,this role is for “women in the common walks of life” (265), not for the exceptionalwho should, she argues, have a “road open by which they can pursue more extensiveplans of usefulness and independence” (265). They can be political representatives(265), physicians, nurses, and midwives (266).19 They can regulate farms andmanage shops (267). Wollstonecraft’s educational program includes girls and boysbeing educated together in “botany, mechanics, and astronomy; reading, writing, arith-metic, natural history and some simple experiments in natural philosophy . . . gymnas-tic[s] . . . The elements of religion, history, the history of man, and politics” (293). Sheeven suggests that domestic duties will only strengthen women for further dutiesoutside the home, including the duties of a soldier. Growing up cramped in nurseriesand made into “mere dolls” (263), women cannot fulfil domestic duties such as breast-feeding, and “when they neglect domestic duties, they have it not in their power to takethe field, and march and counter-march like soldiers, or wrangle in the senate to keeptheir faculties from rusting” (263). Woman must be allowed the physical and intellec-tual strength to manage domestic duties and, in turn, manage social, political, and civilduties as well. She rejects Rousseau’s notion that women cannot “leave the nursery forthe camp” (263), but states, instead, that the “true heroism” of “justifiable war” can“animate female bosoms” once again (263). Women can have power both within andoutside the home in a variety of trades from farmer to shopkeeper, from senator tosoldier, and it is partially through the healthy practice of breastfeeding that her bodyis ready for such activities.

Wollstonecraft’s program for biologically-based political equality also questionsthe naturalness of man’s sexual drive, especially if it interferes with breastfeeding.She criticizes men who “refuse to let their wives suckle their children” (169). Accord-ing to popular medicine, women who breastfeed should abstain from sexual inter-course, which could spoil the milk and harm the baby. Husbands, in their desire to

698 D. Edelman-Young

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dia

na Y

oung

] at

16:

15 0

2 N

ovem

ber

2014

satiate their sexual appetites, are “devoid of sense and parental affection” if they keepmothers from their duty, says Wollstonecraft (169). Only a debauched husband wouldfail to see the beauty of the mother nursing the child:

Cold would be the heart of a husband, were he not rendered unnatural by early debauch-ery, who did not feel more delight at seeing his child suckled by its mother than the mostartful wanton tricks could ever raise, yet this natural way of cementing the matrimonial tie,and twisting esteem with fonder recollections, wealth leads women to spurn. (259)

Again, the father must remain chaste, but he can achieve a healthy kind of pleasure(“more delight”) from the strengthening of his wife and child through breastfeeding.Wollstonecraft questions the naturalness of excessive sexual gratification and, by label-ing the oversexualized husband “unnatural,” refutes the notion that men have strongersexual appetites than women, scaffolding the argument with the medical directiveagainst too much sex, but at the same time allowing for a calmer, healthier kind of plea-sure for both husband and wife.

Breastfeeding creates healthy children, hampers the human tendency towards vice,and encourages the parental bond, benefits that establish the practice as essential, fornow, in the move towards biological perfectibility. The following passage demonstratesthat the “business” of breastfeeding is the duty of both male and female:

Her parental affection, indeed, scarcely deserves the name, when it does not lead her tosuckle her children, because the discharge of this duty is equally calculated to inspirematernal and filial affection: and it is the indispensable duty of men and women tofulfil the duties which give birth to affections that are the surest preservatives againstvice. (272; emphasis added)

The mother must breastfeed, and the father must support her. The physical and moralcomponents of breastfeeding converge in this disquisition on parental affection wherebreastfeeding creates “affections that are the surest preservatives against vice” becauseit keeps the man at home with pleasures and delights that do not oversatiate but makethem all healthy and robust. Social “virtues” – fashion, a delicate constitution, thesexual needs of husbands – militate against nature and biology, creating sickly chil-dren, the “bloated monster” (132), and the “half-formed limbs” of depraved parents(105). Breastfeeding, in which mother and father participate, creates healthy, robustmen, women, and children, leading to not only a stronger nation but also a moreperfect species in which the human form becomes a beautiful, genderless “being” (144).

Wollstonecraft systematically counteracts English culture’s definition of the“natural” through the reproductive sciences, one of the most normalizing scientific dis-courses in the eighteenth century as now. Simultaneously rejecting some medicalclaims while appropriating others, Wollstonecraft rewrites the biological imperative.The central thread in her argument comprises the reproductive capabilities of boththe male and female bodies and their effect on the nation and the evolution ofsociety. She raises women to the level of rational creatures with souls, but shereminds her readers of the physicality of the male body by demonstrating the effectsof his material self on his family, his nation, and his species. Woman’s biologicaland civic duties converge in the womb and the breast. Similarly, man’s converge inhis organs of generation and in his support of maternal breastfeeding. Suckling one’sown children not only creates healthy children but also prevents the births of toomany children, a drain on natural and political resources. Further, breastfeeding

European Romantic Review 699

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dia

na Y

oung

] at

16:

15 0

2 N

ovem

ber

2014

strengthens woman to be able to serve in other ways outside the home; in addition, itkeeps husbands closer to home and away from vice. In this way, breastfeeding endowswoman with political agency, a positive and hopeful image in Vindication. At the sametime, the male figure is a significant source of both the problem and the solution. If the“bloated monster” spreads disease, his wife, children, England, and the species are injeopardy. If he is robust, healthy, and chaste, the breastfeeding mother can not onlydo her duty for those “chubby cheeks,” but also participate in the world of politics, edu-cation, science, and other professions. In this way, Wollstonecraft collapses the dividebetween home/work, private/political, material/creative, female/male in an effort to“form a being advancing gradually towards perfection” where the “sexual [does] notdestroy the human character” (Vindication 144; emphasis added).

Notes1. During this time period, “natural history” involved the study of plants and animals in their

natural environments (e.g., Carl Linnaeus’s categorization of species). “Natural history,”closely associated with the term “natural philosophy,” included biology and geology, com-ponents of what we would now call the “natural sciences”; thus, when I use this termthroughout the essay, I am using Wollstonecraft’s and her contemporaries’ terminology.

2. This William Smellie is not to be confused with the “father” of modern obstetrics andfamous lecturer in midwifery.

3. All references to Wollstonecraft’s reviews come from the Butler and Todd edition of herWorks and will be cited by volume and page number in the text.

4. All quotations from Vindication of the Rights of Woman, cited parenthetically in the text,come from the Penguin edition, edited by Miriam Brody.

5. For some interesting discussions of Wollstonecraft’s engagement with scientific dis-courses of the period, see Lexey A. Bartlett’s 2005 essay “Pathological Conceptions,”which I discuss in more detail in note 8 below. Lila Marz Harper’s Solitary Travelers(2001) places Wollstonecraft’s work in the context of recent histories that read “womenwriters as popularizers of science” (14). Although she argues primarily about A Short Resi-dence, Harper’s argument fits well with what I am saying about Wollstonecraft’s engage-ment with natural history and the natural sciences in Vindication: “the travel narrativeserved as the means by which women could gain a foothold in a traditionally mascu-line-dominated field . . . the scientist-as-explorer identity is adapted by each writer’shand to make carefully targeted inroads into the concept of what constituted scientificauthority” (14). In this way, Wollstonecraft’s use of scientific discourse is, to someextent, a rhetorical move to establish authority and to “write” science, of whatevervariety, on her own terms. Anka Ryall’s “A Vindication of Struggling Nature” (2003)argues that “her natural history of Scandinavia involves her in a critical dialogue withthe major, officially recognized, eighteenth-century ‘systems’ or ‘oeconomies’ ofnature. Indeed, I want to argue that she aligns herself with certain male and metropolitannatural histories both to undercut their complacent assertions and to coopt them for herown purposes” (118). Indeed, I am making the same case here, but I believe Wollstone-craft’s engagement with these natural histories can be seen clearly, though more subtly,in Vindication.

6. Gender issues unfold in many forms in the critical history – Wollstonecraft’s negotiationbetween her role as a professional writer and her role as a woman, the conflict betweenWollstonecraft’s commitment to reason and her own “feminine” emotions and sexuality,and her success as a feminist in modern terms. Modern feminists criticize Wollstonecraftfor her repeated lapses “back into sentimental jargon and romantic idealism” (Poovey 105)and her “prescriptive assault on female sexuality” (Kaplan 163). The title of Susan Gubar’sessay, “Feminist misogyny: Mary Wollstonecraft and the paradox of ‘It takes one to knowone,’” suggests that Wollstonecraft herself was complicit in some of the misogynist dis-course of her time. For additional texts that discuss the problematic nature of Wollston-craft’s feminism, see Wendy Gunther-Canada’s “‘The Same Subject Continued’: TwoHundred Years of Wollstonecraft Scholarship” (1995), Carol H. Poston’s “Mary

700 D. Edelman-Young

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dia

na Y

oung

] at

16:

15 0

2 N

ovem

ber

2014

Wollstonecraft and the ‘The Body Politic’” (1995), Eileen Janes Yeo’s “Some Contradic-tions of Social Motherhood” (1997), Claudia L. Johnson’s “Mary Wollstonecraft: Stylesof Radical Maternity” (1999), Angela Keane’s “Mary Wollstonecraft’s Imperious Sympa-thies: Population, Maternity and Romantic Individualism” (2000), Barbara Taylor’s MaryWollstonecraft and the Feminist Imagination (2003), Jim Gough’s “Mary Wollstone-craft’s Rhetorical Strategy: Overturning the Arguments” (2005), Thomas Ford’s “MaryWollstonecraft and the Motherhood of Feminism” (2009), and Mary Beth Tegan’s“Mocking the Mothers of the Novel: Mary Wollstonecraft, Maternal Metaphor, and theReproduction of Sympathy” (2010). Interestingly, the more recent works attempt torescue Wollstonecraft from charges of essentialism and/or her supposed disgust withfemale sexuality. As I see it, there are three major problems with charging Wollstonecraftwith misogyny based on her apparent attitude towards female sexuality: (1) it reifies thegender categories by assuming that female sexuality is necessarily an avenue to intellectualand political freedom; (2) it fails to acknowledge the sexual freedom Wollstonecraft exhib-ited in her private life; and (3) it fails to register her comments on male sexuality, whichare, as I am here arguing, wholly relevant.

7. Another important work to consider in this context is Toni Bowers’ The Politics ofMotherhood (1996) in which she argues that the first half of the century is responsiblefor establishing the ideal of “natural” motherhood – self-sacrifice, domesticity, virtue,obedience to male authority – upon which much writing of the second half of thecentury is based. Bowers argues that this ideal was established in the literature in sucha way as to eradicate differences in socio-economic status that might offer differenttypes of motherhood. The monolithic narrative of ideal motherhood, despite being predi-cated on subservience to the patriarchy, did not, however, eliminate a woman’s responsi-bility or culpability if she failed to live up to that ideal. At the same time, the narrativesBowers explores register moments of choice and resistance that “reveal maternity to bea multitude of changing behaviors and attitudes, taking shape within specific material con-ditions” (30). Wollstonecraft’s work, I would argue, fits nicely into Bowers’ trajectorybecause it registers resistance to this ideal quite explicitly in that she does not acceptthe ideal of “natural” motherhood and even states from the beginning of her argumentthat she is dealing primarily with the middle classes. Bowers writes that “Augustan narra-tives of monstrous motherhood implicitly valorize the maternal behaviors advocated inconduct writing for ‘middling’ women as instinctual and universal, even in material cir-cumstances that make such behaviors impossible, inadequate, or inappropriate” (29).Wollstonecraft, at least, acknowledges that class matters even if, at times, she subscribesto some aspects of the maternal ideal such as self-sacrifice.