Catching a Butterfly –The Identity of Pentecostal Theology

-

Upload

seuniversity -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of Catching a Butterfly –The Identity of Pentecostal Theology

Paul N. van der Laan, “Catching a Butterfly”EPTA-Conference 2008

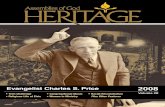

Catching a Butterfly –The Identity of Pentecostal TheologyPaul N. van der Laan PhD

Professor of Religion at Southeastern University, Lakeland,Florida, USA

Presented at the Annual Meeting of the European PentecostalTheological Association

Senic, Slovakia, June 24-27, 2008

INTRODUCTION

Imagine that I would release a butterfly in this roomduring my presentation. I am confident that this butterflywould draw all your attention and you would marvel at itsbeauty. Not far from where I live you can walk amidst thesefragile creatures at Cypress Gardens in Winter Haven, Florida.One is literally surrounded by multiple varieties ofbutterflies lighting here and there on plants and sometimeseven people. After you have walked through this hall, called“Wings of Wonder”, you can view a wide variety of butterfliespinned to a display case, butterflies collected from a varietyof places reflecting a variety of types. Usually visitorshardly pay any attention to these taxidermic animals. You canimagine why. Pentecostal Theology is like the flyingbutterfly, the moment you catch it there is a danger inkilling it. Trying to pin it to a display case for furtherstudy destroys the experience of the butterfly in flight. As adead species it is easier to investigate, but the amazement isgone. It is my prayer that this imagery butterfly will keepflying during this presentation. Some may even recognize thewings of a dove.

I would like to start with a brief historical overview offormer and contemporary attempts to formulate a PentecostalTheology. Then I would like to propose four particular areasthat a genuine Pentecostal theology should address. It is mythesis that after one hundred years of modern Pentecostalhistory, we still lack a theology that is rooted into thecharacteristics and hermeneutics of our Pentecostal identity. Before I will present my proposed methodology we need to get abetter picture of our starting point.

HISTORICAL OVERVIEW

1

Paul N. van der Laan, “Catching a Butterfly”EPTA-Conference 2008

The Pentecostal pioneers were standing on the shouldersof the Wesleyan Holiness tradition1, Restorationism,Dispensationalism2 and Afro-American Christianity3. After morethan a century we are indebted to many Pentecostal andCharismatic scholars who have attempted to articulate ourspecific theology. In this brief overview I will limit myselfto the publications in the Anglo-Saxon world in particular inthe area of systematic theology. Even with this limitation itis far from complete, although I will attempt to touch uponthe major publications. In his article Reflections of a Hundred Yearsof Pentecostal Theology4, Paul W. Lewis, divides the development ofthe formulation of Pentecostal Theology in the followingperiods:

1. The period of formulation (1901-29 i.e. Topeka Kansas –death Charles Parham).

2. The period of entrenchment and adaption (1929-1967 i.e.death Charles Parham-RCC Charismatic Renewal).

3. The period of challenge (1967-84 i.e. RCC CharismaticRenewal-emerge of the Third wave).

4. The period of reformulation (1984-present)

The first generation of Pentecostal leaders were eitherautodidacts or had received their theological training in thedenomination they formerly belonged to5. They usuallyformulated their particular Pentecostal doctrines inperiodical articles or small booklets. During those early

1 Donald Dayton, The Theological Roots of Pentecostalism, (Metuchen, NJ & London:Scarecrow Press, 1987).2 D. William Faupel, The Everlasting Gospel, The Everlasting Gospel: TheSignificance of Eschatology in the Development of Pentecostal Thought(Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1996).3 Walter Hollenweger, Pentecostalism: Origins and Developments Worldwide (Peabody,MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 1997). and Allan Anderson, , Introduction toPentecostalism: Global Charismatic Christianity, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press,2004).4 Paul W. Lewis, Ph.D., Reflections of a Hundred Years of PentecostalTheology, Cyberjournal for Pentecostal-Charismatic Research #12, January 2003,www.pctii.org/cyberj/cyberj12/lewis.html5 For instance Euduros Bell (USA): Baptist, Alexander Boddy (UK): Anglican– Jonathan Paul (Germany): Lutheran and Thomas Ball Barratt (Norway):Methodist.

2

Paul N. van der Laan, “Catching a Butterfly”EPTA-Conference 2008decades the classical Pentecostals formulated their creeds6,which classical Pentecostals preferred to call: Statements ofFaith or Statements of Fundamental Truths. As a secondgeneration emerged the need to articulate their theologybecame evident, especially in the Bible schools, where usuallytheology was taught as one of the main subjects. Jacobsendefines the development of the second generation of A/GPentecostals as “Pentecostal scholasticism.” He argues that“the most prominent characteristics of the Pentecostaltheology written during this era, were its logicalorganization and systematic completeness. Never before hadPentecostals arranged their beliefs with such a degree oflogic.”7 In the USA the two most prominent theologians of thisperiod are Myer Pearlman (1898-1943) and Ernest S. Williams(1885-1981). Pearlman taught theology at Central BibleInstitute (A/G) at Springfield, Missouri when he wrote his TheDoctrines of the Bible in 19378. Williams published hisSystematic Theology in 19539, four years after he had completedtwenty years tenure as General Superintendent of theAssemblies of God (1929-1949). During this period a majorconcern was to be theologically and phenomenologicallyacceptable within mainstream Evangelicalism in the USA,culminating in their application for membership in theNational Association of Evangelicals shortly after itsfoundation in 1942.

6 A/G, Statement of Fundamental Truths (1916)ag.org/top/Beliefs/Statement_of_Fundamental_Truths/sft_short.cfm; Church of God,Cleveland Declaration of Faith - www.churchofgod.org/about/declaration_of_faith.cfmChurch of God in Christ – Doctrines of COGIC - www.cogic.org/dctrn.htmThe Foursquare Church Declaration of Faith drawn up by Aimee SempleMcPherson: www.foursquare.org/landing_pages/4,3.html.7 Douglas Jacobsen, Knowing the Doctrines of Pentecostals: The Scholastic Theology of theAssemblies of God, 1930-55, Paper presented at the twenty-third annual meetingof the Society for Pentecostal Studies at Guadalajara, Mexico, November1993, p. 1.8 Meyer Pearlman, The Doctrines of the Bible (Springfield, MO: Gospel PublishingHouse, 1937).9 E.S. Williams, Systematic Theology (3 vols.; Springfield, MO: GospelPublishing House, 1953). Williams was the General Superintendent of theAssemblies of God from 1929-1949.

3

Paul N. van der Laan, “Catching a Butterfly”EPTA-Conference 2008

In the United Kingdom, pioneers like George Jeffreys(1889-1962)10 and Donald Gee (1891-1966)11 focused most of theirtheological essays on defending particular Pentecostal themeslike baptism in the Holy Spirit, healing and spiritual gifts.The more philosophically inclined Derek Prince was probablythe most notable writer of the second generation of Englishpublications. In his “foundations series”12 he also discussedtopics like Christology, soteriology and eschatology. In 1976Percy S. Brewster (1908-1980 / Elim Pentecostal Church) editedand published a comprehensive Pentecostal Doctrine13, whichincluded the major Pentecostal themes but also a chapter on“Doctrine and modern Society”14. In 1998 Keith Warringtonedited a volume entitled Pentecostal Perspectives15, whichincluded contributions on bibliology, pneumatology,eschatology, healing and exorcism, worship and the ordinances.

Going back to the United States, the most remarkablepublication in the eighties was probably the Foundations ofPentecostal Theology16 by the American authors Guy P. Duffield& Nathaniel M. Van Cleave of the International Church of theFoursquare Gospel. The book was advertised as being “the mostcomprehensive book on the theology of Pentecostals to date.”It certainly was a genuine attempt to cover all the classicaltheological topics from a Pentecostal perspective. The bookincluded a lengthy chapter of over 50 pages on divine healing.Surprisingly there was no separate chapter on Christology and10 George Jeffreys, The Miraculous Foursquare Gospel, Vol. I and II, (Clapham:Elim Publishing Company, 1930). ____, Healing Rays, (Elim Publishing Company, 1932). ____, Pentecostal Rays: The baptism and gifts of the Holy Spirit, (Elim Publishing Company,1933). 11 For an overview of the writings: David A. Wormack, Pentecostal Experiences – Thewritings of Donald Gee, (Springfield, Mi: Gospel Publishing House, 1993). 12 Derek Prince, originally published in three volumes in 1973: Volume 1 -Foundation for faith and repent and believe; Volume 2 - From Jordan toPentecost and Purposes of Pentecost; Volume 3 - Laying on of Hands andResurrection of the Dead and Eternal Judgment. In 1986 a revised andcompiled volume Foundation Series, was published by Sovereign WorldInternational. 13 P.S. Brewster ed., Pentecostal Doctrine, prepared, edited, compiled andpublished by P.S. Brewster, 1976.14 A.F. Missen in P.S. Brewster ed., Pentecostal Doctrine, 373-380.15 Keith Warrington ed., Pentecostal Perspectives, (Carlisle, Cumbria: PaternosterPress, 1998).16 Guy P, Duffield and Nathaniel M. Van Cleave, Foundations of PentecostalTheology, (L.I.F.E. Bible College, Los Angeles, 1983).

4

Paul N. van der Laan, “Catching a Butterfly”EPTA-Conference 2008angelology was covered in between ecclesiology andeschatology. It did lack the embedding of a consistent world-view and there hardly was any reference to nor any discussionwith contemporary theologians. In the 1990’s the Assemblies ofGod published some updated works on their theology. Thescholars William Menzies and Stanley Horton expanded on theStatement of Fundamental Truths17 in their Bible Doctrines of1993. One year later Horton edited a Systematic Theology18,which gave a platform to the leading A/G theologians topresent their expertise. Like Foundations of PentecostalTheology this volume reflected on all the major theologicaltopics, but due to the variety of authors it did not present acoherent philosophy with component parts that articulatedtheir system of belief. During the same period French L.Arrington, a leading theologian of the Church of GodCleveland, published a three volume systematic theologyentitled Christian Doctrine: A Pentecostal Perspective19. Thisseries is another example of an evangelical theology, withsome extra emphasis on particular Pentecostal themes. All ofthese works lacked some of the crucial Pentecostalcharacteristics, which I will discuss later.

With the arrival of the Charismatic movement in thesixties and the third wave and Neo-Charismatics in theeighties the Pentecostals became blessed with the input fromtheologians from various Christian denominations, who tried toembed their new experience within their tradition. Theecumenical thrust that was so characteristic for the earlyPentecostals, especially in Azusa Street Mission and Europe,was given a second chance. A few major theological works wereproduced by some of their adherents, which are still beingwidely used in Pentecostal and Charismatic Colleges andUniversities. J. Rodman Williams, who had served as an early

17 William W. Menzies and Stanley M. Horton, Bible Doctrines: A PentecostalPerspective, (Springfield, Mo.: Logion Press, 1993).18 Stanley M. Horton ed., Systematic Theology: A Pentecostal Perspective, (Springfield,Mo.: Logion Press, 1994).19 French L. Arrington, Christian Doctrine: A Pentecostal Perspective - Volume 1, 2 and 3(Cleveland, TN Pathway Press).Volume 1 (1992 – 216 pages): the Scriptures and Revelation, God, Creation,and ManVolume 2 (1993 – 279 pages: Jesus Christ, Sin, and SalvationVolume 3 (1994 – 277 pages): the Holy Spirit, the Church, and the LastThings.

5

Paul N. van der Laan, “Catching a Butterfly”EPTA-Conference 2008president of the international Presbyterian CharismaticCommunion, wrote his Magnum opus Renewal Theology20 in thenineties. He called this “an expression of theologicalrevitalization”21. The Systematic Theology of Wayne A. Grudem,a Baptist who was at one time a qualified supporter of theVineyard Movement and one of the main apologists andspokespeople for reuniting Charismatic, Reformed, andEvangelical churches, was published in 199422. It has onechapter on the baptism and filling of the Holy Spirit and twoadditional chapters on the gifts of the Holy Spirit. Theseextensive works of Williams and Grudem include a more coherentworldview and system of belief than any of the Pentecostalworks that have been published so far. They also try to remainfaithful to the Biblical text, which clearly is the decisivesource for their conclusions. But obviously their works are amix of Pentecostal convictions in particular in the field ofpneumatology and the theological position of their owndenominational background. They also do not present theparticular characteristics a Pentecostal theology shouldinclude, on which I will expand a little later. The cross-fertilization of charismatic and neo-charismatic theology hasproduced a wider ecumenical interest in theological topicsthat once seemed to belong exclusively to the Pentecostalrealm. In the 21st century a few Pentecostal scholars haveentered the arena of ecumenical and intercultural dialogue.The Finnish theologian Veli-Matti Kärkkäinen has produced anamazing number of books23, in which he reflects on Pentecostal20 Originally Rodman Williams wrote this as a three volume work entitledRenewal Theology (Vol. 1, God, the World, and Redemption, 1988; Vol. 2, Salvation, theHoly Spirit, and Christian Living, 1990; and Vol. 3, The Church, the Kingdom, and Last Things,1992. The three volumes are presently published as one unabridged volume(Zondervan, 1996) entitled Renewal Theology.21 J. Rodman Williams, Charismatic Pentecostal Theology, www.jrodmanwilliams.net. 22 Wayne A. Grudem, Systematic Theology: An Introduction to Biblical Doctrine, (GrandRapids: Zondervan, 1994).23 Veli-Matti Kärkkäinen, Pneumatology: The Holy Spirit in Ecumenical, International, andContextual Perspective, (Grand Rapids, Mi.: Baker Book House, 2002).________., Toward a Pneumatological Theology: Pentecostal and Ecumenical Perspectives onEcclesiology, Soteriology and Theology of Mission (Lanham, Maryland: University Press ofAmerica, 2002, edited by Amos Yong)________., An Introduction to the Theology of Religions: Biblical, Historical & ContemporaryPerspectives, (Inter-varsity Press, 2003).________., An Introduction to Ecclesiology: Ecumenical, Historical & Global Perspectives(Inter-varsity Press, 2002).

6

Paul N. van der Laan, “Catching a Butterfly”EPTA-Conference 2008theology in the context of church-historical and contemporarycontributions. His encyclopaedic knowledge and ecumenicalspirit helps Pentecostal scholars to break out of theirisolation and opens them up to be enriched by the treasures oftraditional and contemporary Christianity. Kärkkäinen howeverhardly seems to recognize the potential and significance ofthe Pentecostal approach, which may bring a paradigm shift inthe field of theology as a whole.

Others have tried to come to grasps with theintercultural and global complexity of Pentecostal theology.The Swiss theologian Walter J. Hollenweger, who putPentecostalism on the academic map, was one of the first whoperceived that the Pentecostals had many roots and werecharacterized by a global diversity. In his Pentecostalism:Origins and Developments Worldwide24 he expands on the BlackOral, the Catholic, the Evangelical, the Critical and theEcumenical roots of Pentecostalism. Allan Anderson, one of hissuccessors at the University of Birmingham (UK), haselaborated on this thought. In his Introduction toPentecostalism, he presents a bird’s eye view of the majorglobal developments. In his conclusion he observes “thatPentecostalism with its flexibility (or ‘freedom’) in theSpirit has an innate ability to make itself at home in almostany context”25. Amos Yong26 and Frank Macchia27 have recentlyeach produced a book that had “Global (Pentecostal) Theology”in its subtitle. In his first chapter Yong presents aninteresting study of Latin-American, Asian and African

________., Pneumatology: The Holy Spirit in Ecumenical, International, and ContextualPerspective, (Grand Rapids, Mi.: Baker Book House, 2003)________., Christology: A Global Introduction, (Grand Rapids, Mi.: Baker Book House,2003).________., The Doctrine of God, (Grand Rapids, Mi.: Baker Book House, 2004).________.,One with God: Salvation as Deification and Justification, (Liturgical Press,2004).________., The Trinity: Global Perspectives, (Louisville, KY: Westminster John KnoxPress, 2007).

24 Walter J. Hollenweger, Pentecostalism: Origins and Developments Worldwide,(Peabody, Ma.: Hendrikson Publishers, 1997). 25 Allan Anderson, Introduction to Pentecostalism: Global Charismatic Christianity,(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 283. 26 Amos Yong, The Spirit Poured Out on All Flesh: Pentecostalism and the Possibility of GlobalTheology, (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2005).27 Frank D. Macchia, Baptized in the Spirit: A Global Pentecostal Theology, (Grand Rapids,MI: Zondervan, 2006).

7

Paul N. van der Laan, “Catching a Butterfly”EPTA-Conference 2008Pentecostalism28. He continues to apply this diversity in theareas of soteriology, ecclesiology, ecumenical world theology,pneumatology and theology of creation. Macchia acknowledgesthe Pentecostal oral tradition and opens with an appropriatetestimony of his own experience of Spirit baptism29, afterwhich he enters into a dialogue with this central distinctivein the fields of Trinitarianism, ecclesiology and life. Theworks of Kärkkäinen, Anderson, Yong and Macchia are veryhelpful in the ecumenical and academic discussion ofPentecostalism. In retrospect I am inclined to divide thepast century in the following four subsequent periods:

1) 1906-1931 Formulation of Pentecostal creeds30

2) 1931-1956 In search of evangelical recognition3) 1956-1981 Interaction with the Charismatic movement4) 1981-2006 In search of ecumenical and academic

recognition.

The years are a bit ambiguous. I have simply divided thecentury in four quarters. Certainly there are overflowingelements in each of these periods. If I apply this analysis tomy original analogy of a butterfly, we see the followingdevelopment. During the first period the butterfly was caughtin the net of Biblicism and fundamentalism, in the secondperiod the butterfly was preserved under the glass bell ofevangelicalism, in the third period the butterfly got lost inthe variety of different traditions and in the fourth periodthe butterfly was put on display alive by Pentecostaltaxidermists.

I want to make an appeal for a new era, in whichPentecostals rediscover their identity and potential topresent a new approach to theology. My heart-desire is to givea voice to all those people who have experienced the life-changing power of the Holy Spirit and to articulate theirdeepest convictions in a way that will preserve itsdistinctive contribution and power, while simultaneously willnot alienate them from the larger body of Christ. In short:

28 Yong, 33-80.29 Macchia, 11-13.30 See for an excellent overview of this period: Douglas Jacobsen, Thinkingthe Spirit: Theologies of the Early Pentecostal Movement (Bloomington, In: IndianaUniversity Press, 2003).

8

Paul N. van der Laan, “Catching a Butterfly”EPTA-Conference 2008Release the Pentecostal butterfly in its own unique way in themidst of the other Christian butterflies.

A PENTECOSTAL QUADRILATERAL

In 1983 the University of South Africa (Unisa) commencedwith a research project on Pentecostalism and the charismaticmovement in order to try and understand the growth of thissection of Christianity and to take its theologicalcontribution seriously.31 This resulted in the publication of abook in 1989 entitled What is distinctive about PentecostalTheology?32. In the conclusion of this book Henry Lederle, atthat time professor of systematic theology at Unisa, suggeststhat “the essence of Pentecostal faith lies in the doctrine ofJesus Christ and that it can be found in the specificconcentration on Jesus as Saviour, Spirit-baptizer, Healer andthe soon and coming King”33. This foursquare summary ofPentecostal doctrine was the banner of the InternationalChurch of the Foursquare Gospel (ICFG) founded by AimeeMcPherson in 1923 and the Elim Foursquare Gospel Allianceinitiated by George Jeffreys in the United Kingdom in 1929. Itis also mentioned in the introduction of the Statement ofFundamental Truth of the Assemblies of God34. This underlinesthat the Pentecostal movement is Christ-centred, rather thanPneuma-centred. It helps to highlight the major doctrines inPentecostal theology, but it does not provide an insight inits major overarching theme nor in its methodology. ThePentecostal quadrilateral I am about to propose is ratherderived from the so-called Wesleyan Quadrilateral35. John

31 Henry I. Lederle, The Pentecostal Proprium, paper presented at the 17th annualmeeting of the international Society for Pentecostal Studies at the CBNUniversity, Virginia Beach, VA., p. 321.32 Matthew S. Clark & Henry L. Lederle et al, What is Distinctive about PentecostalTheology?, (Pretoria: University of South Africa, 1989). 33 Ibid, p. 164. 34 The first paragraph states: “Four of these, Salvation, the Baptism in the Holy Spirit,Divine Healing, and the Second Coming of Christ are considered Cardinal Doctrines which areessential to the church's core mission of reaching the world for Christ.” Assemblies of GodStatement of Fundamental Truths,ag.org/top/Beliefs/Statement_of_Fundamental_Truths/sft_full.cfm35 This term was coined first by Albert C. Outler: “The WesleyanQuadrilateral- In John Wesley”. Wesleyan Theological Journal 20:1, Spring, 1985.For a profound discussion see: Winfield H. Bevins, A Pentecostal Appropriation of

9

Paul N. van der Laan, “Catching a Butterfly”EPTA-Conference 2008Wesley used four different sources in coming to theologicalconclusions:

1. Scripture 2. Tradition 3. Reason 4. Experience

Following this pattern my suggestion is that Pentecostalsshould include the following four adjectives to define theirtheology:

1. Experiential2. Scriptural3. Prophetic4. Intercultural

This can be summarized the acronym E.S.P.I.. Some may suggestthat if we mix this with the R.T. of Reformed Theology, wetruly have the E.S.P.R.I.T. (French for Spirit), but I willnot go there. In addition I would like to define this as a“Theology of the Heart”. I am still in the process of tryingto establish a coherent philosophy that will bring togetherthe component elements. For now I have chosen for thefollowing overarching theme: “God’s embracing love for theworld embodied in His son Jesus Christ through the power-giftsof the Holy Spirit manifested by His church.” I am open foryour suggestions and it may be the topic of my paper at thenext SPS-conference. For the remainder of this presentation Iwould like to elaborate on the Pentecostal quadrilateral, theESPI I have just released. Indeed the butterfly has a name!

EXPERIENTIAL

In What is distinctive about Pentecostal Theology Clark &Lederle discussed the central role experience has inPentecostal life. They observed: “A Pentecostal meeting hasalways been an event, an experience, and those who attend havealways expected that something will happen, and that it willhappen to them …. To be Pentecostal is to have experienced the

the Wesleyan Quadrilateral, Presented at the 34th Annual Meeting of the Societyfor Pentecostal Studies, Virginia Beach, VA, 2005.

10

Paul N. van der Laan, “Catching a Butterfly”EPTA-Conference 2008power of God in Jesus”36. John Bond states that in Pentecostalthinking theology follows experience. “First comes the act ofGod, then follows the attempt to understand it”37.Historically this is not always the case. Many of the earlyPentecostal pioneers including Charles Parham, WilliamSeymour, Alexander Boddy and Gerrit Polman, were convincedthat the biblical evidence of the Baptism of the Holy Spiritis speaking in tongues before they had experienced thisthemselves. Nevertheless I would argue that Pentecostals donot perceive their experience as a closing and final act intheir process of theological deliberation, like it is in theWesleyan quadrilateral. On the contrary, an encounter with Godusually is the starting point out of which their theology isdeveloped. That is why I have chosen to begin each section inthe systematic theology I am in the process of writing with atestimony. This puts the rest of the theological deliberationin the context of real life. To illustrate this let me read a story of Stephen Jeffreys(1876-1943), the brother of the renowned George Jeffreys. Thiscould be used in the theological section that covers dreamsand visions. The year of this vision is remarkable. It tookplace in 1913 shortly before the outbreak of World War I. Thefollowing was reported in the local newspaper of Llanelli,where this event took place:

‘A remarkable experience is related by those who attend the mission services nowbeing held at the Island Place Gospel Hall. For some months past Mr. StephenJeffreys, an earnest mission worker, has been conducting services here among asection of the community to whom the churches and chapels seem to make noappeal. During the service on Sunday night the congregation were startled to see avision appearing on the wall behind where the preacher was standing. The outlinesappeared to be blurred at first, but by-and-by the congregation recognized the headand face of the Man of Sorrows, with the Crown of Thorns upon His head. Speakingto a “Star” representative to-day, Mr. Jeffreys gave a thrilling account of what hedescribed as “THE VISION OF THE MASTER.”

“We have had many conversions,” he said, “but what occurred on Sunday nighttranscends all that one could have hoped for. My back was turned to the portion of36 Matthew S. Clark & Henry L. Lederle et al, What is Distinctive about PentecostalTheology?, 43.37 John Bond in Matthew S. Clark & Henry L. Lederle et al, What is Distinctiveabout Pentecostal Theology?, 135. At the time of the publication Bond served asthe General Chairman of the Assemblies of God in South Africa.

11

Paul N. van der Laan, “Catching a Butterfly”EPTA-Conference 2008the wall where the vision appeared, and my attention was drawn to it by some of thecongregation who were spell-bound to see the face of our Blessed Lord standingboldly out on the wall. There was no mistaking the appearance - it was the Man ofSorrows looking on us with ineffable love and compassion shining out of Hiswonderful eyes.

The effect upon us all was one that will never be forgotten by any who wereprivileged to behold it. Some of my congregation saw the head crowned with thorns,but I cannot speak as to this, as I did not see it. The face, however, was not to bemistaken, and it still haunts me. It remained on the wall for hours after the serviceclosed, and we kept the building open in order that all should have the opportunityof witnessing this wonderful revelation. Many unbelievers came in and it was a proofto us that the Lord is with us in our work, and it will inspire us to more wholeheartedconsecration to His service.”38

The experiences that are chosen should be a collection ofevents that have taken place in the universal body of Christover the ages. This will illustrate that the Pentecostalmovement is standing on the shoulders of a long tradition anddoes not have an exclusive mandate on divine encounters. Inaddition I think a Pentecostal theology should be partlybiographical. This shows how the presented truth is relevantin the life of the author and seems an authentic way howPentecostals share truth. For this reason the experiencesshould also include some personal stories. Let me illustratethis by the following story that I intend to use in thesection about God’s provision:

My wife and I were living by faith. The church in Mechelen, Belgium were I served asyouth pastor, did not have the resources to provide in a salary. At the time my wifewas pregnant with our first child. We lived in the church building. We did not have acar, not even a washer. We were completely broke. The Lord had provided in themoney to buy a second hand double-decker bus, which we were going to use toevangelize the region. I left with a brother from the church to find an appropriatebus in England. It broke my heart that I had to say goodbye to my wife, knowing thatwe had nothing in our cupboard for a next meal, nor did we have a penny to buy it.I felt betrayed by God. Was it not my first responsibility to take care of my family? Iwas tempted to “steal” from the money we had raised for the double-decker bus, but38 Author unknown, From a cutting from the Llanelli Star in Hero's of theFaith - Stephen Jeffreys, posted athttp://one-more-thing.blogspot.com/2007/10/heros-of-faith-stephen-jeffreys.html

12

Paul N. van der Laan, “Catching a Butterfly”EPTA-Conference 2008was able to resist that temptation. How I prayed during that week when we werebrowsing through England. We had no telephone so all I could do was to send mywife postcards, in which I tried to encourage her. I was so worried. When we finallyreturned with a bus we bought in Manchester, I was afraid my wife would be starvedand our baby had died. However, when I saw her face she was all smiles. We hadtold no one about our financial disposition, but during my absence the Lord hadprovided in a car, a washer and enough cash to help us through the rest of the year.Someone had given the money he had saved to buy a hairpiece, so we would have awasher when the baby was born. Jahweh Jireh – God will provide!

So far I have tried to avoid the term “narrative theology”.Many have argued that the Pentecostal preference fortestimonies and stories is linked to our black oral roots39.The use of narratives certainly has strong biblical backing.In His teaching, Jesus Christ used many parables to conveytruths. Nevertheless I think the term “narrative” is confusingwhen we apply it to Pentecostal theology. It seems to implythe use of fictitiously stories, to prove a point. Thisallegorical application does not seem characteristic for theway Pentecostals use narratives. They rather tell real eventsthey have experienced. The early Pentecostal periodicals, like“The Apostolic Faith” of the Azusa Street Mission, are filledwith testimonies of people whose lives were changed by anencounter with God. It is also a common practice inPentecostal churches to give room for testimonies and usuallythe sermon also includes a personal story. For this reason Isuggest that we limit the use of narratives to trustworthy andverified events that have occurred in real. This seems to bein line with the specific Pentecostal application of the same.

SCRIPTURAL

Brian Robinson has rightly observed that “experientialtheology does not need to reject Scripture as final authority,nor deny orthodox Christian reflection”40. On the contrary Wordand Spirit are like two mirrors, which if they reflect the39 Michael Goldberg,. "Theology and Narrative." E.P.T.A. Journal Vol. 1 No. 4(1982). 68-69.Jean-Daniel Plüss, Therapeutic and Prophetic Narratives in Worship: A Hermeneutic Study ofTestimonies and Visions : Their Potential Significance for Christian Worship, Studies in theIntercultural History of Christianity (Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang,1988).

13

Paul N. van der Laan, “Catching a Butterfly”EPTA-Conference 2008image in the right angle produce a glimpse of eternity. Weneed both the objective and subjective source to come to abalanced theological conclusion. It is peculiar thatadversaries of Pentecostalism regularly accuse us ofsubjectivism, where our theological works usually are based ona fundamentalistic investigation of Scripture. One can openalmost any of the books that I have mentioned in my historicaloverview above to prove this point. Let me illustrate this bythe wording of the 7th Fundamental Truth of the Assemblies ofGod on the baptism in the Holy Ghost:

All believers are entitled to and should ardently expect and earnestly seek thepromise of the Father, the baptism in the Holy Ghost and fire, according to thecommand of our Lord Jesus Christ. This was the normal experience of all in the earlyChristian church. With it comes the endowment of power for life and service, thebestowment of the gifts and their uses in the work of the ministry (Luke 24:49; Acts1:4,8; 1 Cor 12:1). This experience is distinct from and subsequent to the experienceof the new birth (Acts 8:12-17; 10:44-46; 11:14-16; 15:7-9). With the baptism in theHoly Ghost come such experiences as an overflowing fullness of the Spirit (John 7:37-39; Acts 4:8), a deepened reverence for God (Acts 2:43; Heb 12:28), an intensifiedconsecration to God and dedication to His work (Acts 2:42), and a more active lovefor Christ, for His Word and for the lost (Mark 16:20).

Many scriptures are used to sustain their position, butno experiential nor prophetic proof is added to this. In thebooks Foundations of Pentecostal Theology41 and BibleDoctrines42 the same methodology is applied. The accusation ofsubjectivity may be true in our praxis, but does not apply toour theology. In fact I want to make an appeal that we becomemore conscious and proud of our identity and integrate more ofour subjective interaction with the Spirit in our theology,but this needs to be balanced by profound and scholarlyexegesis of the Biblical text. In the early decadesPentecostals studied the Bible through the prism ofFundamentalism, Restorationism and Dispensationalism. The40 Brian Robinson, A Pentecostal Hermeneutic of Religious Experience, Paper delivered atthe 21st annual meeting of the Society for Pentecostal Studies atSpringfield, MO – 1992, 3. 41 Guy P, Duffield and Nathaniel `M. Van Cleave, Foundations of PentecostalTheology, (L.I.F.E. Bible College, Los Angeles, 1983).42 William Menzies & Stanley Horton, Bible Doctrines: A Pentecostal Perspective,((Springfield, Mi. Logion /Gospel Publishing House 1993).

14

Paul N. van der Laan, “Catching a Butterfly”EPTA-Conference 2008second generation of Pentecostals restricted themselves toevangelical hermeneutics. Through our encounters with thecharismatic and neo-charismatic movements and our increasingopenness to academic research, we have started to enrich ourtheology with the various Christian traditions and opened adialogue with contemporary theologians. The latestdevelopments indicate that we are now discovering our ownintercultural diversity. We realize more then ever before thatstudy of the Bible is complex. At the same time we need torediscover our first naïveté, to read Scripture in a way thatopens us to understand the text by the guidance and insight ofthe Holy Spirit.

PROPHETIC

I now enter the most dangerous section of my proposedmethodology. Feel free to walk away angry. I will even allowyou to shout in agony, but please do not throw stones. We areliving in New Testament times!My point is simply this: if a Pentecostal studies the Bibleshe or he is not content with a mere academic investigation.We have accepted Calvin’s hermeneutical rule that “Scriptureinterprets scripture.”, but in our praxis this is just thestarting point of our exegesis. We want to come to a pointwere we “receive” a divine revelation or insight to understandthe deeper meaning of the text. If this happens we use phraseslike “the Holy Spirit showed me” to underline that ourconclusions go beyond cognitive research. We apply this in ourpersonal lives, our Bible studies and sermons, but so far thisis hardly integrated in our theology. I am convinced that oneof the reasons that Pentecostalism is so appealing to many isthe fact that we dare to speak with divine authority. Irealize that this has been and is being abused by many tomanipulate others. It certainly does not concur with thecritical-analytical method, which is so widely accepted inWestern academia. Let us not forget however that this was oneof the main reasons why Pentecostals have been so hostiletowards academia. The accumulation of knowledge presented bythe academia resulted according to their perception merely inconfusion and the loss of faith. Let us try to keep both theknowledge and the faith. They are not necessarily mutualexclusive. I am in good company here. Gordon Fee argues that

15

Paul N. van der Laan, “Catching a Butterfly”EPTA-Conference 2008the ultimate aim of exegesis is the “Spiritual one”.43 He urgesthat we must hear the Word of God with our hearts.44 He feltschizophrenic when he was trying to meet the academicrequirements for exegesis while remaining true to his passionfor the Bible. He described this tension as “trying to playbaseball, but was allowed to play only by the rules ofsoccer.”45 Steven Land has argued that “a distinctivePentecostal spirituality should be reflected in the processand results of the theological task”.46 I suggest we do so byincluding the prophetic element in our theology.

Let me illustrate the prophetic element by two examples.The first is the commentary of Matthew Henry (1662-1714) onGenesis 2:21: That the woman was made of a rib out of the side of Adam; not made out of hishead to rule over him, nor out of his feet to be trampled upon by him, but out of hisside to be equal with him, under his arm to be protected, and near his heart to bebeloved47.

It is debatable whether the conclusion Henry draws here can besustained by other scriptures. I am not even sure if this isthe reason why God created Eve out of Adam’s side, but hiscommentary helps me to understand the equality and partnershipbetween a man and woman. It resounds in my spirit and in myPentecostal perception I like to think that Henry wasenlightened by the Spirit to write down this thought. In theartistic world we are probably more open to recognize a divinetouch as is illustrated in the story of how George FriedrichHändel (1685-1759) composed his Messiah:

Although born in Germany, Handel established a home in London in 1712. He servedas the director of the Royal Academy of Music, the co-manager of the King’s Theatre,and an associate with the Royal Opera House at Covent Garden. By 1740, he had losta fortune in business, and he had become depressed and full of despair. Accordingto a pamphlet of the Choral Society at Trinity College in Dublin, one night, after

43 Gordon D. Fee, To What End Exegesis? Essays: Textual, Exegetical and Theological ( GrandRapids, Mi: William B. Eerdmans Company, 2001), p. 276.44 Ibid, p. 289.45 Ibid, p. 278. 46 Steven J. Land, Pentecostal Spirituality: A Passion for the Kingdom (Sheffield:Sheffield Academic Press – Journal of Pentecostal Theology SupplementSeries I, 1993), p. 218. 47 Matthew Henry, Commentary on the Whole Bible, Volume I , Genesis 2:21-25, TheFormation of Eve: 4. from PC Study Bible Formatted Electronic Database.

16

Paul N. van der Laan, “Catching a Butterfly”EPTA-Conference 2008walking the streets of London, Handel returned to his rundown room to find anenvelope from Charles Jennens, his librettist. As Handel handled the pages, henoticed they contained various scriptural texts. He set the script aside and climbedinto bed, but he found sleep would not come. Biblical passages battered his mindlike the pounding of an anvil: words from Isaiah: “For unto us a child is born”; wordsfrom Matthew: “Glory to God in the highest and peace on earth, good will towardsmen”; words from Revelation: “Hallelujah! … And He shall reign for ever and ever.” Still unable to sleep, Handel moved to his piano and began to write passionatelynight and day for three weeks. During this time, he refused to allow anyone to visithim, and he refused food and rest. At the end of the third week, Handel had finishedhis work; his valet finally gained entrance to his room and found him with tearsstreaming down his cheeks. Handel cried out: “I do believe I have seen all of Heavenbefore me, and the great God Himself!”48.

I know it is subjective but if I listen to the Messiah, whichindeed is one of my favourite compositions, it feels likeheaven is touching earth. It is like a window into heaven isopened and we are allowed to have a quick peak. Is this notwhat theology should try to achieve? When they asked Walter Hollenweger, my “Doktorvater”, whyclassical Pentecostal were so critical towards John Wimber andhis third-wave theology, he answered: “They know all thetricks”. I am very much aware of the dangers of giving such anauthoritative weight to prophetic interpretation, but weshould not throw away the baby with the bath-water. The bath-water is the haughtiness to think that anyone has the monopolyon truth or the exclusive insight in the full meaning of thebiblical text. All we receive is illumination by the HolySpirit, not inspiration in the way the authors of the Biblewere led by the Holy Spirit to write down the text that wouldultimately become part of our Holy Scripture. The baby is thatwe can receive knowledge and insight that goes beyond academicand cognitive research. As 1 Corinthians 2:10 puts it: God hasrevealed it to us by his Spirit. The Spirit searches all things, even the deep things ofGod. We cannot investigate the Bible by means a computer-program based on the best hermeneutical method and expect anunequivocal and decisive result. Of course the interpretationof a scripture is bound by Scripture as a whole. The Word andthe Spirit cannot contradict each other, but the Holy Spirit48 J.J. Abernathy , A tradition for life: Handel’s Messiah & Southwest Symphony Orchestraand Chorale,www.thespectrum.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20061201/STGEORGEMAGAZINE01/61120007/-1/STGEORGEMAGAZINE13.

17

Paul N. van der Laan, “Catching a Butterfly”EPTA-Conference 2008can help us to come to a prophetic understanding,interpretation and application of scripture. I defineprophetic interpretation as the process in which the HolySpirit gives us illumination or insight in a certainscripture, by which we can apply this with greater authority.This is certainly not limited to those who have the propheticgift; it rather seems an integral part of the office ofteacher. Nevertheless, the New Testament rule towards prophetsthat “others should weigh carefully what is said” (1Corinthians 14:29) also applies in this context. We need todevelop some sound tests by which this prophetic element inour theology can be tested both academically and spiritually.Within these parameters we must try to develop a theology thatis relevant, biblical and is presented with the propheticauthority that I have tried to define in this paragraph.

INTERCULTURAL

Allan Anderson has made a convincing plea that the globalhistory of Pentecostalism is usually described from a biasNorth American perspective and urgently needs correction49. Thedevelopment of the Pentecostal movement in China, India,Chili, Nigeria etcetera is distinct from the Azusa Streetrevival. Paul Pommerville declared that Pentecostalism hadoriginated in a series of roughly spontaneous and universalbeginnings in different parts of the world50. This givesPentecostal theology a unique feature. It has the potential topresent an intercultural and global theology, providing thatwe integrate the contributions from our Pentecostal peers inother parts of the world, in particular from Asia, Africa andLatin-America where the vast majority of Pentecostals are nowlocated. With the emerge of globalization through the fastdeveloping communications, emigration and outsourcing it seemsthat it can serve global Christianity by developing a theologythat is not particularly Western-based, but embraces insightsand world-views from all continents. A precondition to develop

49 Allan Anderson, Revising Pentecostal History in Global Perspective in:Allan Anderson and Edmond Tang, Asian and Pentecostal: The Charismatic face ofChristianity in Asia, (Baguio City, Philippines: Regnum Studies in Mission: AsianJournal of Pentecostal Studies Series 3), 147-171. 50 Paul Pommerville, The Third Force in Missions, (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 1985)52.

18

Paul N. van der Laan, “Catching a Butterfly”EPTA-Conference 2008such a theology is that we encourage Pentecostals in the thirdworld to develop their faith in their own context and enterinto a dialogue with them, so we can integrate their views inour own theology in a relevant and accessible way.

In this way our theology can be enriched by theirinsights and experiences. Wonsuk Ma for instance points outthat voluntary suffering is an important aspect for AsianPentecostals in China, North Korea, Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia,Myanmar, Nepal, Bhutan and Tibet. Becoming a Christian inthese countries is often a life-and-death decision, which hasresulted in persecution in many cases51. They can help us todevelop a much needed theology of suffering. Another word we could use for intercultural in this respectcould be the word integration or inclusiveness. This closingsection in this proposed methodology should not only interactliterally with other cultures, but also try to incorporate orat least discuss various Pentecostal positions and enter intoa dialogue with the various Christian traditions andcontemporary philosophies and theologians.We need to enter into the following three circles:

1. Polemic: Integration of various themes addressed byPentecostals

2. Ecumenical: Dialogue with church traditions andcontemporary theology.

3. Global: Input from Pentecostals form various cultures andcontinents.

In the first inner circle we need to come to terms with thedifferent theological positions Pentecostals have developed.These are like unpaid bills. We need to know where the billcame from, how much we are charged and how we can pay ourdebt. A good example is the dialogue with oneness Pentecostalswithin the heart of this Society for Pentecostal Studies.Similar initiatives can and should be developed with regardsto the Word of Faith theology and other controversies. The dialogue in the second circle is probably the mostdeveloped of the three at this point. Here we see theadvantage if there are equivalent participants. Many

51 Wonsuk Ma, Asian (Classical) Pentecostal Theology in Context, in AllanAnderson and Edmond Tang, Asian and Pentecostal: The Charismatic face of Christianity in Asia,76.

19

Paul N. van der Laan, “Catching a Butterfly”EPTA-Conference 2008Charismatics are well skilled and used to academic dialogue.Their contributions to conferences like these are usually wellappreciated. Cecil Robeck Jr., Veli-Matti Kärkkäinen and manyothers have proven to be outstanding Pentecostalrepresentatives in this ecumenical dialogue. This is a complexand challenging task however, that cannot and should not beleft to some specialists. Pentecostals need to come to termswith their original ecumenical thrust and potential and becomemore pro-active in his area. We come back to third circle of intercultural exchange. TheAsian Pentecostals seem to be the first to discover how theirPentecostal identity can be integrated best in their owncultural context. We can expect a lot more from African andLatin-American Pentecostals in this area in the near future.After having dictated our western theology to them for so manydecades it serves us right to devote at least one decade tolisten to what they have to say. It may help us to understandwhy their growth is so much more substantial than ours.

CONCLUSION

In this presentation I have tried to convince you thatPentecostal theology does not distinct itself by a new insightin certain New Testament themes like Baptism in the HolySpirit or Gifts of the Holy Spirit. It rather presents aparadigm shift in theological thinking. In the historicaloverview I have demonstrated that the theologies that havebeen written by Pentecostals so far do not include our owncharacteristics in applying theology. I have suggested aPentecostal quadrilateral as a methodology that reflects ouridentity and historical roots:

1. Experiential: Black oral roots2. Scriptural: Evangelical roots3. Prophetic: Pietistic roots4. Intercultural: Global roots

I intend to apply this method in a systematic theology, whichI hope to write for students who are studying at anundergraduate level. I need your input to correct and refinemy method. Are these the genuine parameters of a Pentecostal

20

Paul N. van der Laan, “Catching a Butterfly”EPTA-Conference 2008theology? Am I missing out come crucial elements? I lookforward to your suggestions either today in the discussion orby correspondence. I hope I have provoked your thoughts andthat you have kept the amazement of looking at this peculiarbutterfly. Let me close with a final appeal: Do not catch thePentecostal butterfly with your clumsy hands, but with youreyes only!

21